Prolonged Summer Daytime Dissolved Oxygen Recovery in a Eutrophic Lake: High-Frequency Monitoring Diel Evidence from Taihu Lake, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

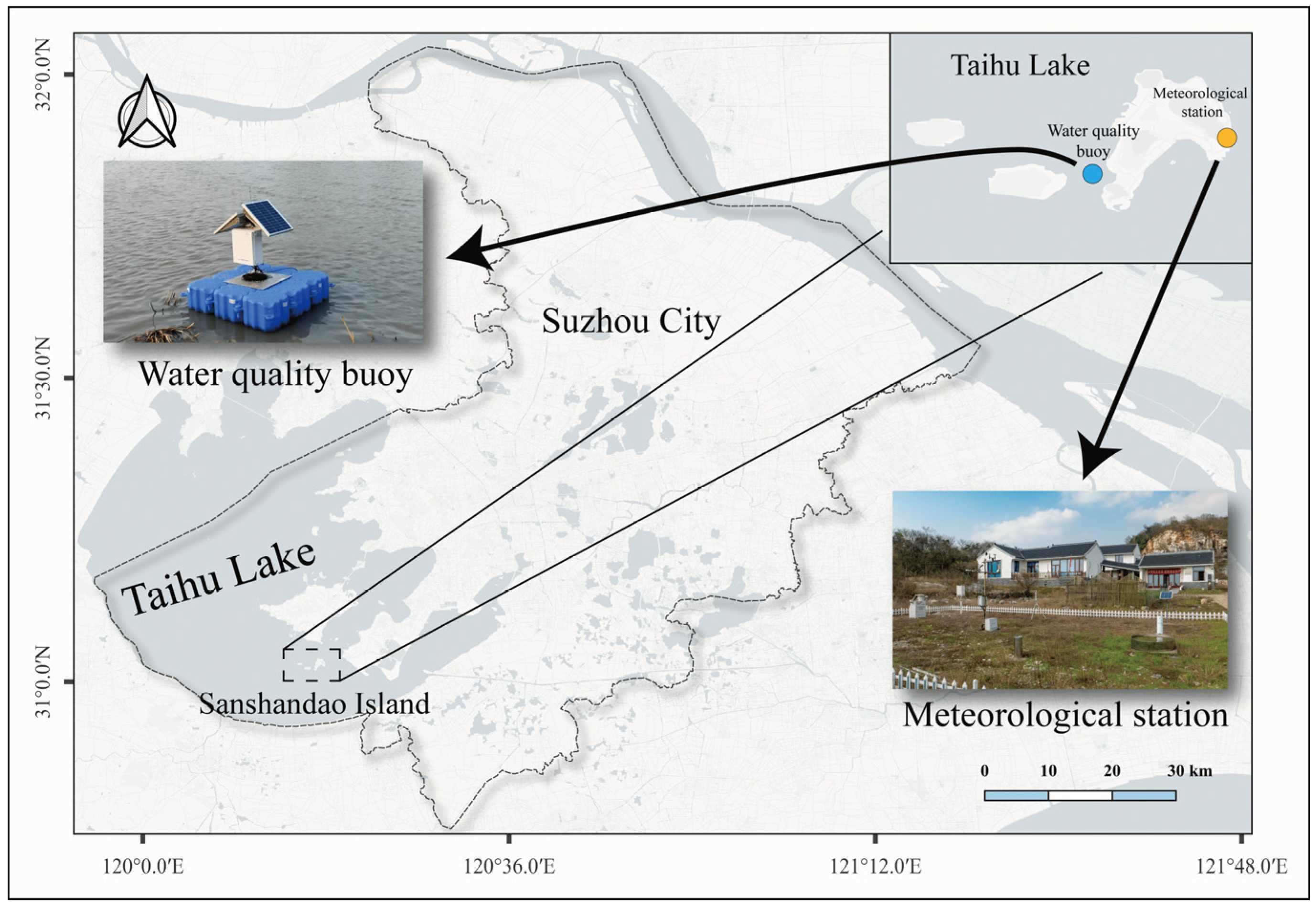

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

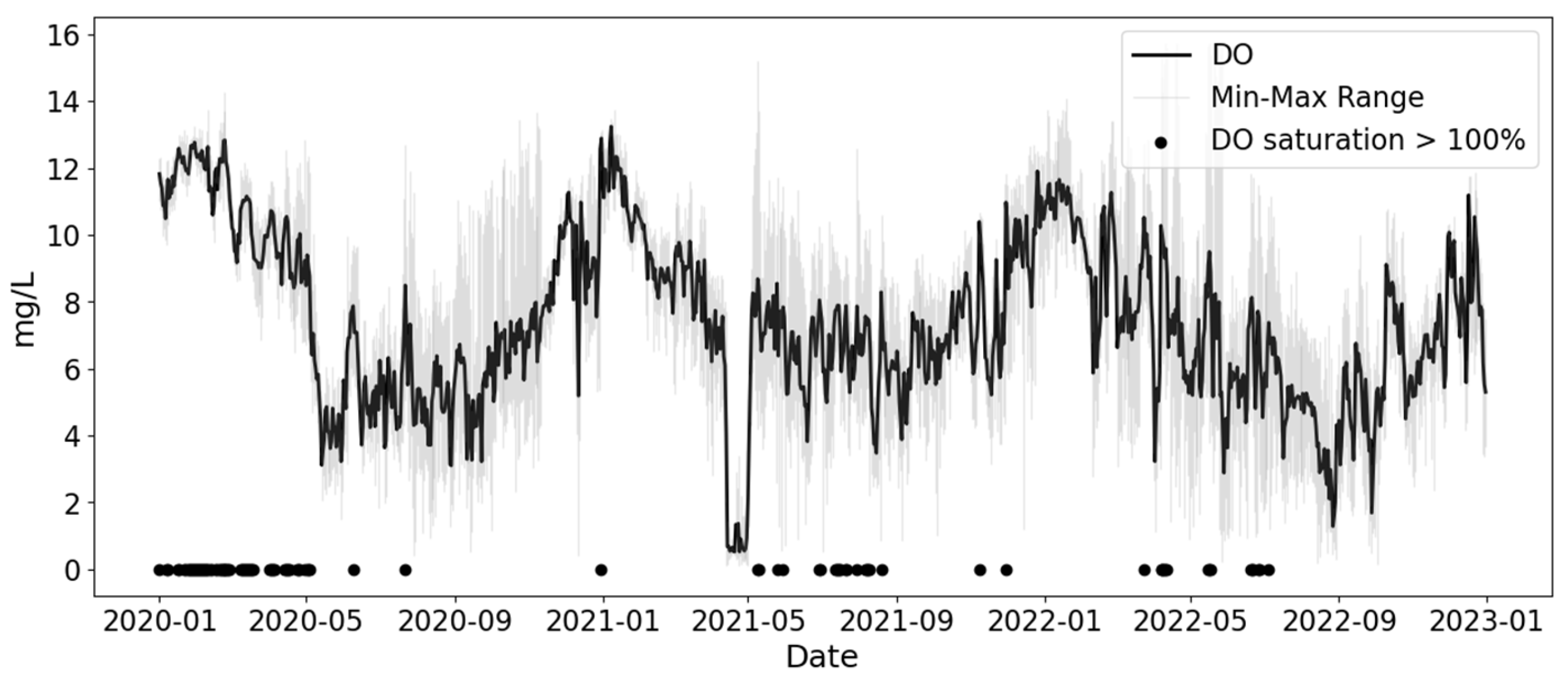

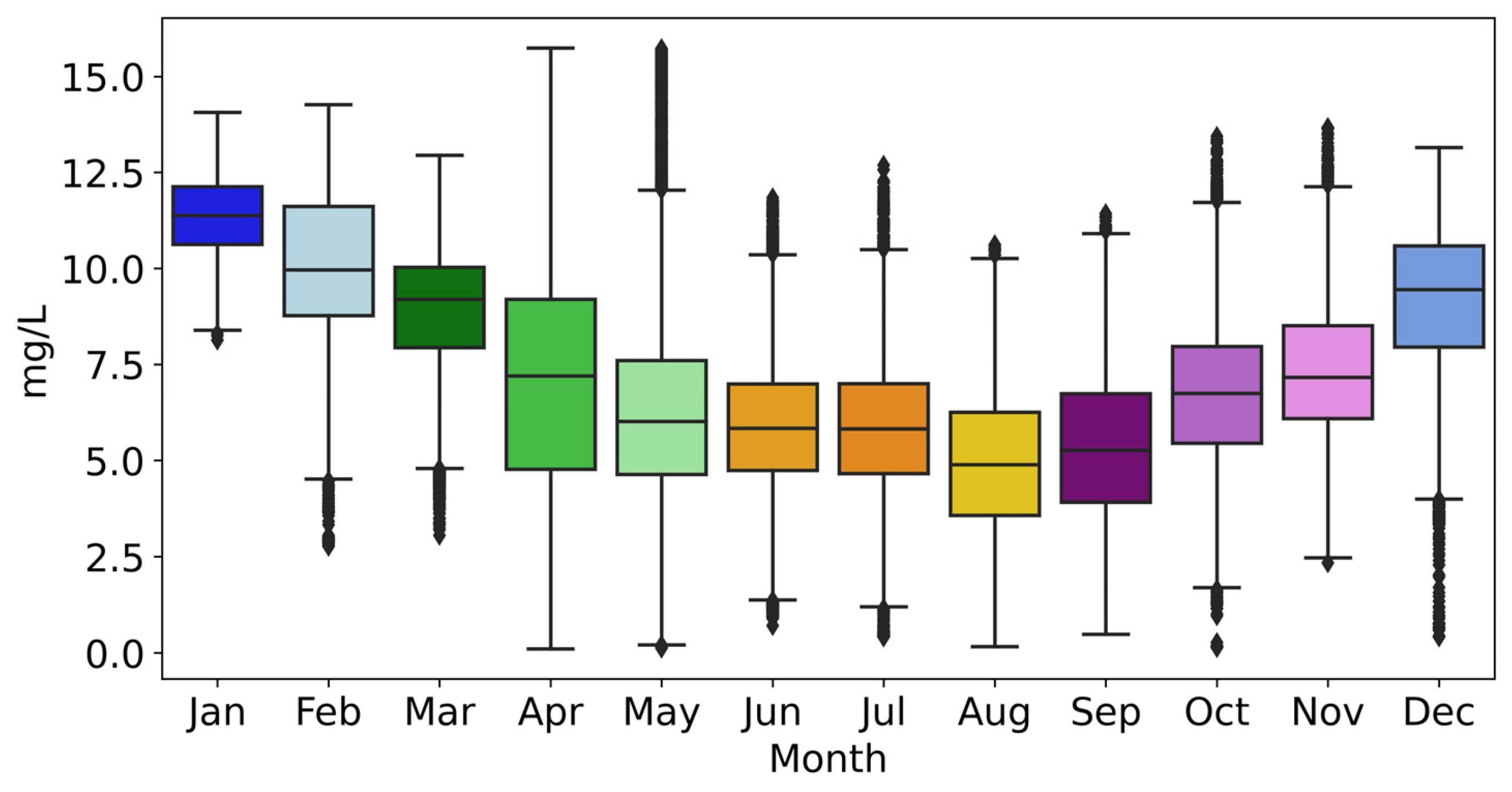

3.1. Annual and Seasonal Variations

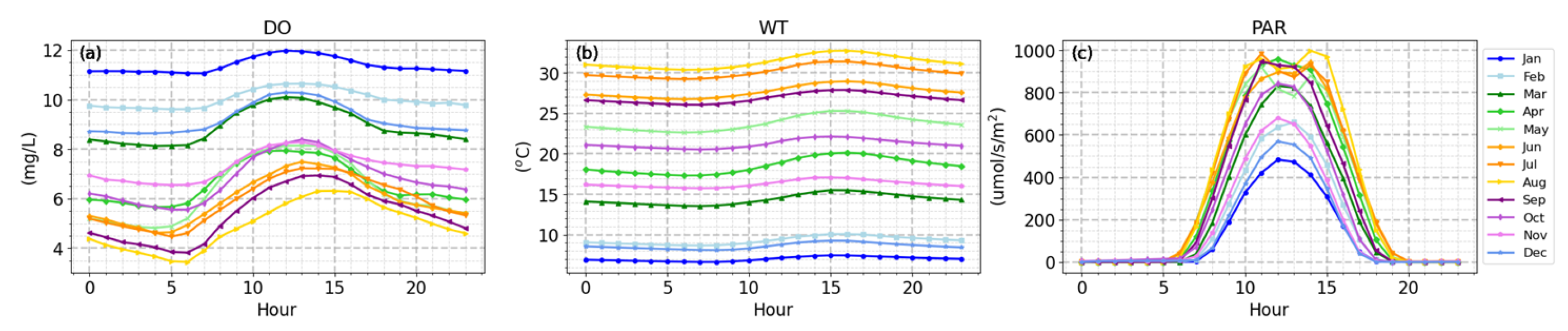

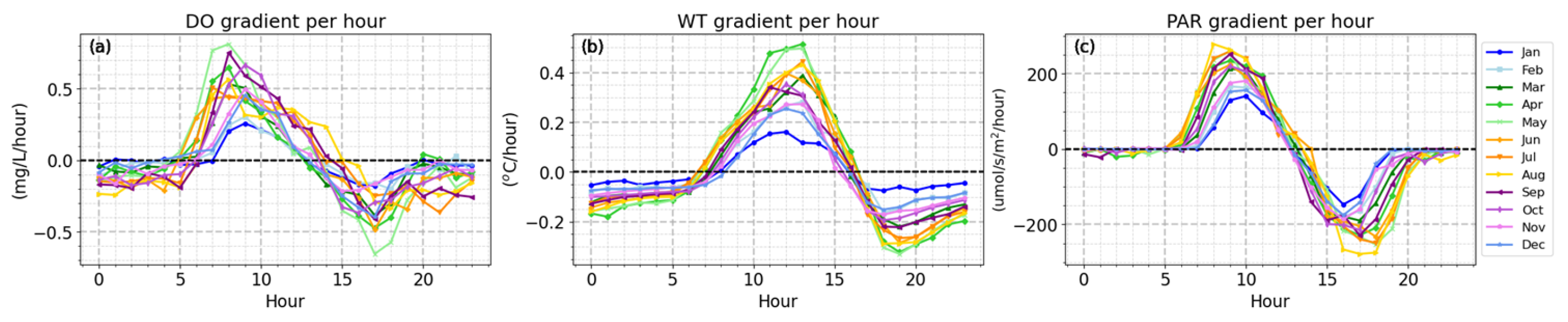

3.2. Diel Variations

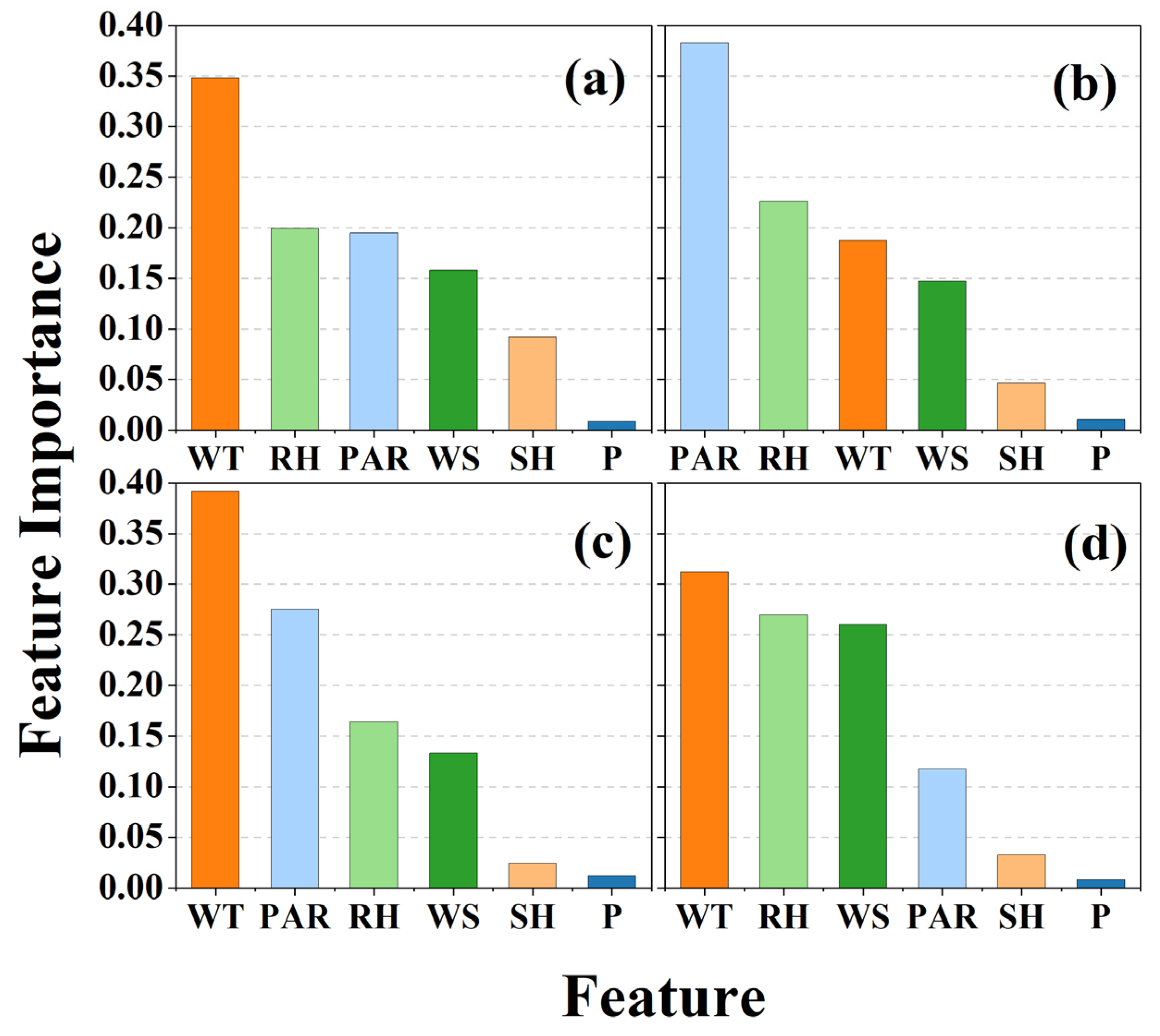

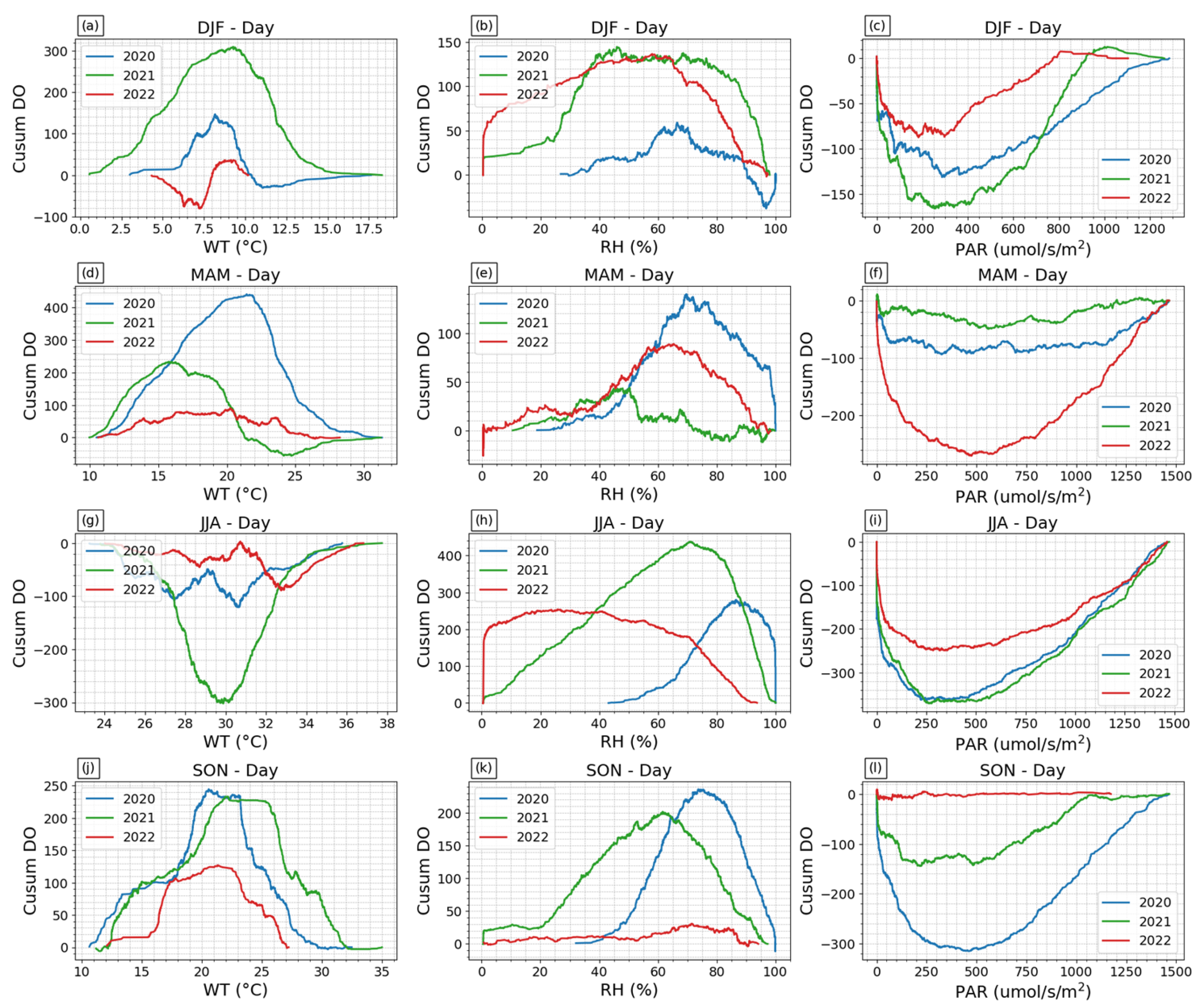

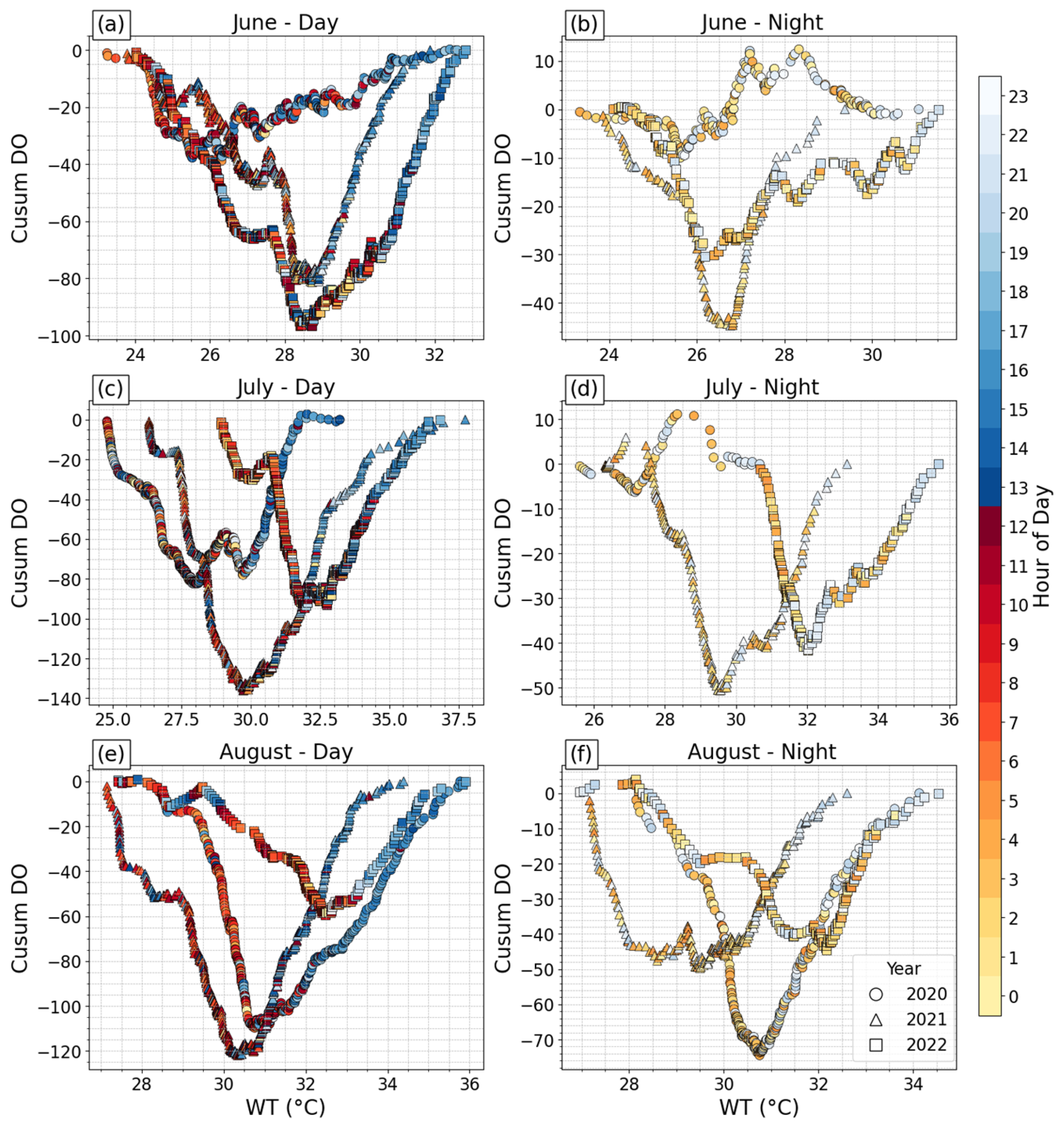

3.3. DO Diel Cycle Associations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Venkiteswaran, J.J.; Wassenaar, L.I.; Schiff, S.L. Dynamics of Dissolved Oxygen Isotopic Ratios: A Transient Model to Quantify Primary Production, Community Respiration, and Air–Water Exchange in Aquatic Ecosystems. Oecologia 2007, 153, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Abdul-Aziz, O.I. Metabolic Scaling of Stream Dissolved Oxygen across the U.S. Atlantic Coast. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Su, Y.; Fang, L.; Naidoo, A.R.; Lv, P.; Lv, S.; Meng, X.-Z. How Anthropogenic Factors Influence the Dissolved Oxygen in Surface Water over Three Decades in Eastern China? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammons, C.H.; Babcock, J.N.; Parker, S.R.; Poulson, S.R. Diel Cycling and Stable Isotopes of Dissolved Oxygen, Dissolved Inorganic Carbon, and Nitrogenous Species in a Stream Receiving Treated Municipal Sewage. Chem. Geol. 2011, 283, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, P.C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Armstrong, D.E.; Stanley, E.H.; Kratz, T.K. Lake Dissolved Inorganic Carbon and Dissolved Oxygen: Changing Drivers from Days to Decades. Ecol. Monogr. 2006, 76, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.; Liboriussen, L.; Trolle, D.; Landkildehus, F.; Søndergaard, M.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Søndergaard, M.; Larsen, S.E.; Jeppesen, E. Daily Net Ecosystem Production in Lakes Predicted from Midday Dissolved Oxygen Saturation: Analysis of a Five-year High Frequency Dataset from 24 Mesocosms with Contrasting Trophic States and Temperatures. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2013, 11, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.R.; Kragh, T.; Sand-Jensen, K. Extreme Diel Dissolved Oxygen and Carbon Cycles in Shallow Vegetated Lakes. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20171427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, A.E.; Seitzinger, S.P. Diurnal Patterns of Denitrification, Oxygen Consumption and Nitrous Oxide Production in Rivers Measured at the Whole-reach Scale. Freshw. Biol. 2004, 49, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, P.J.; Houser, J.N.; Maloney, K.O. Stream Diurnal Dissolved Oxygen Profiles as Indicators of In-Stream Metabolism and Disturbance Effects: Fort Benning as a Case Study. Ecol. Indic. 2005, 5, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, D.P.; Wilson, S.T.; Doney, S.C.; Karl, D.M. Quantifying Subtropical North Pacific Gyre Mixed Layer Primary Productivity from Seaglider Observations of Diel Oxygen Cycles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 4032–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsson, O.; Widerlund, A. Diel Variations in Dissolved Oxygen Concentration and Algal Growth in the Laver Pit Lake, Northern Sweden. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 155, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lee, J.H.W.; Chang, L.; Tang, H.; Liu, H. Field Measurements of the Carbon to Chlorophyll-a Ratio Using Imaging FlowCytobot: Implications for Dissolved Oxygen Modeling. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2023, 285, 108304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sil, S. Diel Variations in the Upper Layer Biophysical Processes Using a BGC-Argo in the Bay of Bengal. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2024, 216, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, G.L.; Kirkpatrick, G.; Lane, P.V.Z.; Langdon, C. Comparative Diel Oxygen Cycles Preceding and during a Karenia Bloom in Sarasota Bay, Florida, USA. Harmful Algae 2014, 38, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, B.; Jamily, J.A.; Fang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hayworth, J.S. Simulating Diurnal Variations of Water Temperature and Dissolved Oxygen in Shallow Minnesota Lakes. Water 2021, 13, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, I.; Green, F.B.; Puhakka, J.A. Seasonal and Diurnal Variations of Temperature, pH and Dissolved Oxygen in Advanced Integrated Wastewater Pond System® Treating Tannery Effluent. Water Res. 2004, 38, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, Y.; Ding, S.; Chen, M.; Li, D.; Hao, X.; Wang, Y. High-Resolution Diurnal Variation Mechanism of Oxygen and Acid Environments at the Water–Sediment Interface during Cyanobacterial Decomposition. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, M.; He, J.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, X. Dissolved Oxygen Stratification and Response to Thermal Structure and Long-Term Climate Change in a Large and Deep Subtropical Reservoir (Lake Qiandaohu, China). Water Res. 2015, 75, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, G.; Wu, Z.; Liu, M. Effects of Rainfall on Thermal Stratification and Dissolved Oxygen in a Deep Drinking Water Reservoir. Hydrol. Process. 2020, 34, 3387–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Azeez, S.; Gireeshkumar, T.R.; Muraleedharan, K.R.; Vignesh, E.R.; Jaleel, A.K.U.; Arya, K.S.; Ravikumar Nair, C.; Ratheesh, R. Factors Influencing Nearshore Hypoxia in the Southeastern Arabian Sea: A Sensor-Based Study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 197, 115696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.W.; Lazorchak, J.M.; Howard, M.D.A.; Johnson, M.V.; Morton, S.L.; Perkins, D.A.K.; Reavie, E.D.; Scott, G.I.; Smith, S.A.; Steevens, J.A. Are Harmful Algal Blooms Becoming the Greatest Inland Water Quality Threat to Public Health and Aquatic Ecosystems? Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, S.; Tare, V. Spatio-Temporal Trends in the Flow and Water Quality: Response of River Yamuna to Urbanization. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zheng, X.; Wang, D.; Yao, E.; Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhong, J. Significant Diurnal Variations in Nitrous Oxide (N2O) Emissions from Two Contrasting Habitats in a Large Eutrophic Lake (Lake Taihu, China). Environ. Res. 2024, 261, 119691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvall, M.S.; Hagy, J.D.; Ammerman, J.W.; Tedesco, M.A. High-Frequency Dissolved Oxygen Dynamics in an Urban Estuary, the Long Island Sound. Estuaries Coasts 2024, 47, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmar, E.C.; Henson, S.S.; Dahlgren, R.A.; O’Geen, A.T.; Van Nieuwenhuyse, E.E. Diel Patterns of Algae and Water Quality Constituents in the San Joaquin River, California, USA. Chem. Geol. 2011, 283, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Han, M.; An, W.; Yu, J. Anoxia Remediation and Internal Loading Modulation in Eutrophic Lakes Using Geoengineering Method Based on Oxygen Nanobubbles. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Acharya, A.; Gupta, V.K.; Bakshi, S.; Paul, M.; Sanyal, P.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K. Diurnal Variation of Abundance of Bacterioplankton and High and Low Nucleic Acid Cells in a Mangrove Dominated Estuary of Indian Sundarbans. Cont. Shelf Res. 2020, 210, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajwa-Kuligiewicz, A.; Bialik, R.J.; Rowiński, P.M. Dissolved Oxygen and Water Temperature Dynamics in Lowland Rivers over Various Timescales. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2015, 63, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, R.M.; Bookout, B.J.; Kaushal, S.S. Influence of Temperature, Precipitation, and Cloud Cover on Diel Dissolved Oxygen Ranges among Headwater Streams with Variable Watershed Size and Land Use Attributes. Aquat. Sci. 2020, 82, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Luo, P.; Wu, P.; Song, C.; Chen, X. Detection of Periodicity, Aperiodicity, and Corresponding Driving Factors of River Dissolved Oxygen Based on High-Frequency Measurements. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Castro, B.; Chmiel, H.E.; Minaudo, C.; Krishna, S.; Perolo, P.; Rasconi, S.; Wüest, A. Primary and Net Ecosystem Production in a Large Lake Diagnosed from High-resolution Oxygen Measurements. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Cai, X.; Testa, J.M.; Brady, D.C.; Cerco, C.F.; Linker, L.C. Simulation of High-Frequency Dissolved Oxygen Dynamics in a Shallow Estuary, the Corsica River, Chesapeake Bay. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1058839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.N.; San Andres, C.F.; Nguyen, K.Q.; Corby, T.L.; Rhodes, M.A.; García, J.; Roy, L.A.; Davis, D.A. Effects of Minimum Dissolved Oxygen Setpoints for Aeration in Semi-Intensive Pond Production of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture 2025, 594, 741376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röder, E.; Licht, G.; Fahle, M.; Weber, A.; Zug, S.; Lau, M.P. Spatial Heterogeneity of Dissolved Oxygen and Sediment Fluxes Revealed by Autonomous Robotic Lakewater Profiling. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2025, 70, 2829–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, M.; Przytulska, A.; Lapierre, J.; Laurion, I.; Lehmann, M.F.; Maranger, R. Hot Tops, Cold Bottoms: Synergistic Climate Warming and Shielding Effects Increase Carbon Burial in Lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2019, 4, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.I.; Sharma, S.; Weyhenmeyer, G.A.; Debolskiy, A.; Golub, M.; Mercado-Bettín, D.; Perroud, M.; Stepanenko, V.; Tan, Z.; Grant, L.; et al. Phenological Shifts in Lake Stratification under Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regier, P.J.; Ward, N.D.; Myers-Pigg, A.N.; Grate, J.; Freeman, M.J.; Ghosh, R.N. Seasonal Drivers of Dissolved Oxygen across a Tidal Creek–Marsh Interface Revealed by Machine Learning. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2023, 68, 2359–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Li, M.; Ross, A.C.; Najjar, R.G. Large Projected Decline in Dissolved Oxygen in a Eutrophic Estuary Due to Climate Change. JGR Ocean. 2019, 124, 8271–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Song, K.; Lv, Y.; Liu, G.; Fang, C.; Hou, J.; Wen, Z. Distinguishing Algal Blooms from Aquatic Vegetation in Chinese Lakes Using Sentinel 2 Image. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Li, X.; Zhou, T.; Feng, Y. Estimating the Contribution of Environmental Variables to Water Quality in the Postrestoration Littoral Zones of Taihu Lake Using the APCS-MLR Model. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truesdale, G.A.; Downing, A.L. Solubility of Oxygen in Water. Nature 1954, 173, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Regier, P.; Briceño, H.; Boyer, J.N. Analyzing and Comparing Complex Environmental Time Series Using a Cumulative Sums Approach. MethodsX 2019, 6, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamizar, S.R.; Segura, C.; Warren, D.R. Using Stream Dissolved Oxygen and Light Relationships to Estimate Stream Primary Production on Mountainous Headwater Stream Ecosystems. Ecohydrology 2024, 17, e2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, K.T.; Zak, N.B.; Baastrup-Spohr, L.; Kragh, T.; Sand-Jensen, K. Ecosystem Metabolism and Gradients of Temperature, Oxygen and Dissolved Inorganic Carbon in the Littoral Zone of a Macrophyte-dominated Lake. JGR Biogeosci. 2022, 127, e2022JG007193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragh, T.; Andersen, M.R.; Sand-Jensen, K. Profound Afternoon Depression of Ecosystem Production and Nighttime Decline of Respiration in a Macrophyte-Rich, Shallow Lake. Oecologia 2017, 185, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreling, J.; Bravidor, J.; Engelhardt, C.; Hupfer, M.; Koschorreck, M.; Lorke, A. The Importance of Physical Transport and Oxygen Consumption for the Development of a Metalimnetic Oxygen Minimum in a Lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2017, 62, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wei, Z.; Ruan, A. Key Roles of Carbon Metabolic Intensity of Sediment Microbes in Dynamics of Algal Blooms in Shallow Freshwater Lakes. Hydrobiologia 2024, 851, 4873–4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, L.C.; Mehring, A.S.; Rosemond, A.D.; Wenger, S.J. Toward More Accurate Estimates of Carbon Emissions from Small Reservoirs. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2024, 69, 1350–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.; Xu, Y.J. Can a Eutrophic Lake Function as a Carbon Sink? Case Study of a Subtropical Eutrophic Lake in Southern USA. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 130071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Moon, H.; Kang, E.J.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.; Kwak, C.-W.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.-N.; Park, K.Y.; et al. The Diel and Seasonal Heterogeneity of Carbonate Chemistry and Dissolved Oxygen in Three Types of Macroalgal Habitats. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 857153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Yan, K.; Gao, M.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, S. Increase in Chlorophyll-a Concentration in Lake Taihu from 1984 to 2021 Based on Landsat Observations. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Gu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Xue, Q.; Xie, L. Changes in Microcystin Concentration in Lake Taihu, 13 Years (2007–2020) after the 2007 Drinking Water Crisis. Environ. Res. 2024, 241, 117597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, G.; Wu, S.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Shi, A.; Yang, Y. Climate Warming and Cyanobacteria Blooms: Looks at Their Relationships from a New Perspective. Water Res. 2017, 125, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Kong, F. Bacterial Community Dynamics and Functional Variation during the Long-Term Decomposition of Cyanobacterial Blooms in-Vitro. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 598, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Rivas-Ruiz, P.; Trapote, M.D.C.; Vegas-Vilarrúbia, T.; Rull, V.; Rosell-Melé, A. Seasonal Effects of Water Temperature and Dissolved Oxygen on the isoGDGT Proxy (TEX86) in a Mediterranean Oligotrophic Lake. Chem. Geol. 2020, 551, 119759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhai, F.; Gu, Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, P. Seasonal Variability in Dissolved Oxygen in the Bohai Sea, China. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2022, 40, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; He, W.; Cai, S. Seasonal Variation of Dissolved Oxygen in the Southeast of the Pearl River Estuary. Water 2020, 12, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Chen, C.; Qi, J.; Beardsley, R.C.; Tian, R.; Zhao, L.; Lin, H. Mechanism Studies of Seasonal Variability of Dissolved Oxygen in Mass Bay: A Multi-Scale FVCOM/UG-RCA Application. J. Mar. Syst. 2014, 131, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, A.; Villate, F.; Uriarte, I.; Alberdi, L.; Intxausti, L. Dissolved Oxygen in a Temperate Estuary: The Influence of Hydro-Climatic Factors and Eutrophication at Seasonal and Inter-Annual Time Scales. Estuaries Coasts 2015, 38, 1000–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardana, C.; Cooray, A.T.; Liyanage, S.S.; Koliyabandara, S.M.P.A. Seasonal and Spatial Variation of Dissolved Oxygen and Nutrients in Padaviya Reservoir, Sri Lanka. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 5405016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; He, Q.; Mao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Z. Dissolved Oxygen Stratification Changes Nitrogen Speciation and Transformation in a Stratified Lake. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 2898–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istvánovics, V.; Honti, M. Coupled Simulation of High-Frequency Dynamics of Dissolved Oxygen and Chlorophyll Widens the Scope of Lake Metabolism Studies: Coupled Simulation of DO and Chl Dynamics. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018, 63, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxa, M.; Musil, M.; Kummel, M.; Hanzlík, P.; Tesařová, B.; Pechar, L. Dissolved Oxygen Deficits in a Shallow Eutrophic Aquatic Ecosystem (Fishpond)—Sediment Oxygen Demand and Water Column Respiration Alternately Drive the Oxygen Regime. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, C.T.; Bruesewitz, D.A.; Richardson, D.C.; Rose, K.C.; Van De Bogert, M.C.; Hanson, P.C.; Kratz, T.K.; Larget, B.; Adrian, R.; Babin, B.L.; et al. Ecosystem Respiration: Drivers of Daily Variability and Background Respiration in Lakes around the Globe. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2013, 58, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Gu, S.; Wu, K.; Tanentzap, A.J.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; He, P.; Qiu, D.; Deng, Y.; et al. Temperature-mediated Microbial Carbon Utilization in China’s Lakes. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 5044–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.F.; Hood, J.M.; Benstead, J.P.; Huryn, A.D.; Welter, J.R.; Gíslason, G.M.; Ólafsson, J.S. Nutrient Enrichment Intensifies the Effects of Warming on Metabolic Balance of Stream Ecosystems. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2022, 7, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Xu, Y.J.; Ma, S.; Le, J.; Zhang, K.; Miao, R.; Li, S. Nitrogen Addition Effect Overrides Warming Effect on Dissolved CO2 and Phytoplankton Structure in Shallow Lakes. Water Res. 2023, 244, 120437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Autilia, R.; Falcucci, M.; Hull, V.; Parrella, L. Short Time Dissolved Oxygen Dynamics in Shallow Water Ecosystems. Ecol. Model. 2004, 179, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, C.J.; Sadler, J.M.; Trolle, D.; Nielsen, A.; Wagner, N.D.; Scott, J.T. Does Polymixis Complicate Prediction of High-frequency Dissolved Oxygen in Lakes and Reservoirs? Limnol. Oceanogr. 2024, 70, S121–S135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, D.; Chen, X.; Qian, Y.; Feng, Y. Prolonged Summer Daytime Dissolved Oxygen Recovery in a Eutrophic Lake: High-Frequency Monitoring Diel Evidence from Taihu Lake, China. Water 2025, 17, 3221. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223221

Xie D, Chen X, Qian Y, Feng Y. Prolonged Summer Daytime Dissolved Oxygen Recovery in a Eutrophic Lake: High-Frequency Monitoring Diel Evidence from Taihu Lake, China. Water. 2025; 17(22):3221. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223221

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Dong, Xiaojie Chen, Yi Qian, and Yuqing Feng. 2025. "Prolonged Summer Daytime Dissolved Oxygen Recovery in a Eutrophic Lake: High-Frequency Monitoring Diel Evidence from Taihu Lake, China" Water 17, no. 22: 3221. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223221

APA StyleXie, D., Chen, X., Qian, Y., & Feng, Y. (2025). Prolonged Summer Daytime Dissolved Oxygen Recovery in a Eutrophic Lake: High-Frequency Monitoring Diel Evidence from Taihu Lake, China. Water, 17(22), 3221. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223221