Abstract

This study presents a data-driven forecasting framework for surface water state trends using time-series modelling based on hydrochemical monitoring data from the Ikva River (Ukraine). The monitoring campaign, conducted between 2021 and 2023, involved monthly sampling of 19 hydrochemical indicators at two sites. We applied the Prophet time series forecasting algorithm, a decomposable additive model, to predict key indicators, including water hardness and bicarbonate concentration. The approach provides a transparent and adaptable method for forecasting water state in data-limited contexts. Key contributions include the integration of high-resolution hydrochemical monitoring with an explainable machine learning model, enabling early warning insights in under-monitored river basins. The case study of best-performing models for hydrocarbonate and hardness confirmed that Prophet offered well-calibrated prediction intervals with rapid deployment, high interpretability, and dependable uncertainty estimation, though its forecasts were comparatively less accurate. Analysis of computational performance shows that Prophet enables faster implementation and quick insights, while ARIMA and LSTM achieve higher predictive accuracy at the cost of longer execution times. Results demonstrate strong predictive skill: for hardness, MAE = 1.64 and RMSE = 1.73; for bicarbonate, MAE = 54.82 and RMSE = 62.00. Coverage accuracy of 95% prediction intervals exceeded 91% for both indicators. The proposed approach provides a practical foundation for implementing early-warning systems and supporting evidence-based water resource management in regions lacking real-time monitoring infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Poor water quality has negative consequences not only for aquatic ecosystems, but also for the suitability and ability to treat water for drinking. It should be noted that water pollution is caused by organic matter (e.g., sewage), toxic and persistent substances (such as heavy metals and pesticides) and pathogens (viruses and bacteria). The saturation of water with nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus compounds, can lead to eutrophication, which in turn can also have significant environmental consequences [1,2].

The procedure for monitoring water resources in Ukraine is based on several provisions, including the Water Code of Ukraine, laws of Ukraine, resolutions, and orders of the government, in accordance with the processes of European integration [3,4,5,6]. It is worth noting that the development of the regulatory framework and monitoring practices is based on the basin approach, as outlined in key EU documents [7,8]. It should be noted that the implementation of river basin management plans is aimed at addressing the following key water and environmental issues: surface water pollution by organic, nutrient and hazardous substances; hydromorphological changes; groundwater pollution and depletion; climate change; reducing the impact of infrastructure projects on water conditions; pollution of water bodies by household waste; biological pollution (spread of invasive species); and the impact of military operations [9].

A separate set of issues is the creation of effective pollution monitoring systems, as well as wastewater management and treatment [10,11]. It is worth noting that EU directives regulate quality standards, compliance, and approaches to water safety based on an overall risk assessment [12,13]. Separate regulations relate to water intended for human consumption, risk assessment and risk management of the water supply system, risk assessment of internal distribution systems, minimum hygiene requirements for materials in contact with water intended for human consumption, minimum requirements for treatment chemicals and filtering agents in contact with water intended for human consumption, monitoring, troubleshooting and restriction of use, access to water intended for human consumption, for information on monitoring implementation, assessment and penalties [14,15].

At the same time, researchers are focused on assessing the state of surface and groundwater used for the drinking water supply to the population, as well as industrial and agricultural water intake, and the reuse of treated wastewater [16,17].

Effective pollution control and reduction require information and assessments on the concentration, impact, loads and sources of pollutants. Such information is collected through monitoring, which serves as the initial stage of the environmental information generation process [18,19]. Countries monitor water resources in accordance with their national priorities and requirements (e.g., legal and operational), as well as international obligations established by international obligations (established by, for example, European Commission directives and international agreements) [7,20,21]. In addition, in all countries, there are budgetary and other resource-related considerations that may limit the coverage of monitoring in terms of water body types, number and types of stations, and key indicators measured. As a result, environmental monitoring is often limited in countries where other, more pressing national budgetary priorities prevail.

From a scientific perspective, studying the relationships between individual hydrochemical indicators in water is crucial [12,22]. The need to improve the system for monitoring hydrochemical indicators necessitates increased requirements for water quality information (its accuracy and reliability) [23]. One way to improve data reliability is to identify patterns between different surface water quality indicators [24]. The existence of such relationships enables the development of calculation equations that facilitate the forecasting of water quality indicators in rivers and the automation of dissolved solids runoff calculations [25,26]. It should be noted, however, that such relationships cannot always be identified due to the complex conditions of water chemistry in specific catchments, as well as anthropogenic impacts (economic activity and wastewater discharges that change the natural hydrochemical regime of rivers). In such cases, statistical methods, such as correlation analysis using artificial intelligence, can help describe and model many hydrochemical processes, especially at the initial stages of research [27].

Moreover, according to the Ukrainian government, the water and sewerage industry of Ukraine suffered losses of USD 11 billion as a result of the full-scale Russian aggression. The enemy damaged 583 water facilities, of which only 223 have been restored, and 1108 kilometres of water and sewerage networks (277 kilometres have been restored). As a result, only 64% of consumers currently have permanent access to centralised water supply and sewerage systems. Due to the destruction of critical water infrastructure caused by power outages, the level of network failures in some cities has risen to 80%. In 2024, 8 million people currently have limited access to a centralised water supply and sanitation [28].

The hostilities in Ukraine and their severe environmental consequences [29] are catalysing the modernisation of the water resources monitoring and management system in Ukraine, in particular through the adoption of relevant regulations in 2024 [30,31].

On 1 November 2024, the Ukrainian government approved the first six-year river basin management plans for eight river basins in Ukraine: the Dnipro, Southern Bug, Dniester, Don, Vistula, Black Sea, Azov, and Crimean rivers.

Several Ukrainian ministries and agencies are involved in water resources monitoring to varying degrees, which complicates the task of coordinating and controlling methods. For example, the State Emergency Service (SES) and the State Agency of Water Resources are involved. The State Agency of Ukraine for Water Resources determines the ecological status of surface water bodies and the ecological potential of artificial or significantly altered surface water bodies based on assessments of biological, hydromorphological, chemical, and physicochemical indicators [7,8]. At the same time, the SES assesses biological and hydromorphological indicators to determine the ecological status of surface water bodies and the ecological potential of artificial or significantly altered surface water bodies.

In total, the observation network comprises 896 groundwater monitoring sites and 483 river operational monitoring sites. In total, the monitoring coverage is 7% of all surface water bodies, whereas in Poland, this figure is 10%, and in France, it is 50% [32]. It is precisely because of the lack of monitoring coverage that the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools enhances the task of forecasting and modelling [33].

Depending on climatic conditions, lithological structure, and relief, the nature and flow of watercourses are affected. Depending on the area of the catchment basin, rivers are divided into large, medium, and small ones. Small rivers with a catchment area of up to 2000 square kilometres are susceptible to anthropogenic influences. Tens of thousands of small rivers have disappeared completely or partially due to natural and anthropogenic causes: climate change, river channel redesign, natural succession processes, land reclamation, water abstraction for economic purposes, reservoir construction, deforestation, ploughing, urban expansion, industrial development, transport infrastructure development, etc. [34]. The condition of small rivers is an indicator of the condition of the entire river network of the country. Therefore, it is crucial to take comprehensive measures to protect small rivers from reduced flow, pollution, and drying up, as well as to mitigate the negative impact of anthropogenic factors.

One of the fundamental principles of environmental measures for small rivers is to enhance the assessment of surface water quality, as well as the monitoring and processing of hydroecological information, to justify the necessary measures for regulating human activity. For example, the Ikva River in Ukraine is a small river which belongs to the largest river basin in Ukraine—the Dnipro. This river is typical of Ukraine and therefore serves as a proper example for modelling and analysis. The primary factors contributing to anthropogenic pollution in the Ikva River are agro-industrial activities and municipal wastewater from populated areas. The primary pollutants of the Ikva River are organic compounds (BOD5), nitrate nitrogen, ammonium nitrogen, nitrite nitrogen, and phosphates.

One of the primary negative factors affecting domestic agriculture due to climate change is the deterioration of moisture conditions. The last one is a limiting factor that restricts crop productivity, reduces the efficiency of chemical and technogenic resources, and, in general, the competitiveness of the state’s agricultural sector. Compared to the 1961–1990 period, areas with a significant deficit of natural moisture have increased by 7% and cover more than 29.5% of the area, or approximately 11.6 million hectares of arable land in Ukraine [34]. As a result of climate change in Ukraine, the deterioration of total moisture supply conditions is observed. The areas of excess moisture have largely disappeared in most regions of Ukraine, while the processes of desertification in the southern regions are intensifying.

Therefore, in order to prevent and mitigate the adverse effects of climate change on water resources, it is necessary to adapt existing technologies and scientifically substantiate new technologies and systems for preserving the river network and improving its hydroecological condition. At the same time, there is a great demand, on the one hand, to reduce the time required to process available information for operational decisions by competent authorities and, on the other hand, to deepen the analysis to identify the risk factors that need to be mitigated.

The novelty of this study lies in the integration of high-frequency hydrochemical monitoring data with the Prophet time series forecasting model to produce explainable and statistically validated forecasts of key water quality indicators in a data-sparse region. Unlike prior studies that either focus on data-rich environments or employ complex black-box algorithms, our approach emphasises transparency, interpretability, and methodological accessibility. We demonstrate how a model originally designed for business time series can be effectively adapted to environmental forecasting, while ensuring scientific rigour through uncertainty quantification, normality testing, and rolling-origin cross-validation. Although Prophet is not a deep learning or ensemble-based model, it incorporates several machine learning features—such as automated hyperparameter tuning, regularised changepoint selection, and flexible nonlinear regression—which position it at the intersection of statistical and machine learning methods. Therefore, this study contributes to the emerging domain of interpretable machine learning in environmental time-series forecasting, with an emphasis on methodological transparency and operational applicability.

2. State of the Art

The excellent capabilities and speed of data processing with modelling tools attracted the attention of environmental scientists more than 50 years ago. The most famous models were created in the context of climate research by the intellectual efforts of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the late 60s and early 70s in the ‘Study of Critical Environmental Problems’ (SCEP) project [35]. Subsequently, Jae Forrester’s team developed and implemented mathematical models based on one of the first Whirlwind I tube computers, including a model of the global system and its potential for the Club of Rome.

In terms of hydrological and hydrometeorological measurements, precipitation and runoff modelling have a much longer history, with the first attempts to predict water availability as a function of precipitation using regression-type approaches dating back 170 years [36]. Since then, modelling concepts have been further developed by gradually incorporating a physical understanding of processes and concepts into the (mathematical) model formulation. This includes explicitly addressing the spatial variability of processes, boundary conditions and physical properties of catchments. These developments are driven mainly by advances in computer technology and the availability of data (remote sensing) with high spatial and temporal resolution.

At various times, authors of climate and environmental studies have employed linear and tree models, as well as more recent approaches such as neural networks and various mathematical models for time series forecasting [37]. In particular, the use of ML tools has improved the processing of various hydro-environmental monitoring datasets, through the use of satellite imagery, meteorological data, and information on biological, physical, and chemical conditions, to predict river flows, groundwater levels, and water availability, and thus improve water resource allocation, infrastructure planning, and operational decision-making [38,39]. Further development of ML tools, data availability, and interdisciplinary collaboration will further promote the use of ML methods to address global water challenges and pave the way for a more resilient and sustainable water future [40]. Before applying machine learning in practice, it is necessary to collect data, select an appropriate algorithm, train the model, and validate the model. Among these processes, the choice of algorithm is crucial [41]. The authors envisage the creation of algorithms for predicting specific chemical parameters of surface waters, such as dissolved oxygen, even on a continental scale [42]. Researchers have identified the primary types of ML applications in the field of environmental science and engineering, including creating forecasts, extracting feature importance, detecting anomalies, and discovering new materials or chemicals [43,44].

A comparative study in finance and economics found that Deep Learning models (like CNN + LSTM) achieved the highest accuracy, while Prophet offered quick and easy deployment but was less precise [45].

Among the promising tools for monitoring data processing tasks is the forecasting of a multidimensional time series using stacked LSTM networks. The architecture of the LSTM network can be applied based on its effectiveness in predicting time series and learning long-term dependencies [46]. Water quality monitoring can be carried out manually as well as by autonomous vehicles using modern robotic systems [47].

In Egypt, LSTM-based models forecasted groundwater quality, obtaining excellent results (very low RMSE and MSE values) across multiple contaminants from nine years of monitoring data.

Hybrid models combining LSTM with CNN (and even Prophet) have been applied to predict water quality indicators such as dissolved oxygen and nutrients; such models are particularly effective for chaotic or nonlinear time series where traditional models struggle [48,49].

At the same time, the construction of integrated water quality monitoring systems based on the Internet of Things requires the compatibility of various sensors and devices, enabling real-time monitoring of water quality [50]. Such tools should adhere to the fundamental principle of information display. Currently, modern tools are available for accumulating and analysing spatial sub-basin and river section data, which are used in HydroATLAS and obtained from the global HydroSHEDS database [51]. At the same time, the construction of an integrated monitoring information processing system should consider at least four data layers: national, transboundary, regional, and global [52]. Forecasting the hydroecological state of water resources is solved, among other things, by machine learning tools [53,54,55]. Among the machine learning methods used to assess the physical, chemical and ecological state of water bodies are, in particular, support vector regression (SVR), artificial neural networks, random forest (RF) and gradient boosting machine (GBM) [56,57].

The concept of an intelligent surface water quality monitoring system has been continuously expanded by the idea of combining online water quality monitoring with various online automatic monitoring devices for data collection, communication protocol, and software for data interpretation [58]. Implementation of an online surface water monitoring system involves calibration and verification methods. Problems in the design and implementation are highlighted as indicators for future improvement and study [59].

It is worth noting that classical distributed measurement systems (DMS) under the new management paradigm are integrated into more complex CyberPhysical Systems (CPS) along with physical infrastructure [60].

The authors of [61] employed a machine learning approach without a teacher, specifically PAM and EM clustering, to categorise wastewater-generating enterprises within a basin. Paper [62] examines the feasibility of developing models to identify relationships between water pollution parameters.

Paper [63] analyses the possibilities of creating models to identify relationships between water pollution parameters based on a comparison of the performance of basic machine learning algorithms. The analysis used data series (temperature, electrical conductivity, cumulative rainfall for the 24 h preceding the day of sampling, and river flow), which were identified as key variables that need to be monitored to optimise the model based on an extensive sensor network. However, the number of factors influencing water pollution is quite wide, and climate change, which has changed the pattern of precipitation and the frequency of extreme events, has obviously disrupted the trends of biological and chemical-physical processes in water [63,64]. In addition, the peculiarities of laboratory testing, particularly its duration, make it difficult to make prompt management decisions, especially regarding water resources used for drinking and recreational purposes. The study [65] utilised a large dataset (33,612 observations) from major rivers and lakes in China to train and test 10 different machine learning models, including traditional and ensemble models. The performance of these models in predicting different levels of water state, as defined by Chinese government standards, was assessed using metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score. The study [66] uses temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), conductivity, total dissolved solids (TDS), turbidity, and chlorides (Cl-) as data sets. To develop artificial neural network and long short-term memory (LSTM) models, the mean absolute error (MAE), mean square error (MSE), and coefficient of determination (R2) are used. The study also utilises heat maps and correlation graphs to illuminate the relationships between various water quality indicators. Next paper [67] evaluates methodologies for better tracking and analysis of pollutants using available technologies to address this problem, which is an urgent need. The development of machine learning and Earth observation systems presents opportunities for tracking water quality indicators, particularly the rising levels of pollution in surface water bodies. The study presents a machine learning model (ML-CB) that combines optical and radar data, along with a machine learning algorithm, to estimate surface water pollutants, including total suspended solids (TSS), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and biological oxygen demand (BOD). The model was trained using optical (Sentinel-2A and Sentinel-1A) and radar satellite images. Study [68] evaluated water quality in three rivers (River Nfifikh, Hassar and El Maleh) of Mohammedia prefecture, Morocco, in terms of heavy metals occurrence during two seasons of winter and spring. The heavy metals analysed were cadmium, iron, copper, zinc, and lead. The heavy metal pollution index was derived to quantify water quality and pollution. Modelling and prediction were performed using random forest, support vector machine and artificial neural network. Paper [69] describes a 10-year study (2011–2020) in which 14 water quality parameters were measured monthly at four water quality monitoring stations on River M in a city in eastern China. Several statistical methods, a water quality index (WQI) model, machine learning (ML), and positive matrix factorisation (PMF) models were used to assess the overall condition of the river, select the most essential water quality parameters, and identify potential sources of pollution.

The review of existing environmental water state monitoring systems and relevant works above demonstrates the peculiarities that affect the quality and reliability of the generalised results of data processing. Given the biological and chemical processes, the most vulnerable parameter of such studies is the time parameter, i.e., the speed of processing the selected sample or test [61,62]. The existing problem of data format incompatibility is quite critical, making it difficult or impossible to display their analysis across all four layers of a potentially integrated monitoring information processing system. Other factors, such as insufficient coverage of environmental data sources, inconsistent application of methodologies, and the human factor, also contribute to the decline in the quality of existing studies.

In our previous work [70], we built a machine-learning model to select the most efficient algorithm for processing the data set. We developed a meta-classifier that combines several basic classifiers as part of an ensemble model with reasonably high accuracy (97%). At the same time, the data sample was limited and did not account for seasonal temperature variations, focusing solely on chemical pollution parameters. Moreover, the data from the previous study reflected three values—maximum, minimum, and average—which made it impossible to analyse the pollution of the watercourse during the year of observation. Therefore, the goal of the paper is to explore the relationship between various hydrochemical indicators as well as to carry out the analysis of their dependence. To reach this goal, we have designed the two objectives:

- -

- development of a data-driven forecasting framework for surface water state trends using time-series modelling based on hydrochemical assessment data from the Ikva River (Ukraine).

- -

- the integration of high-resolution hydrochemical assessment with an explainable Phroper model, enabling early warning insights in the monitored river basin.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Description of Object

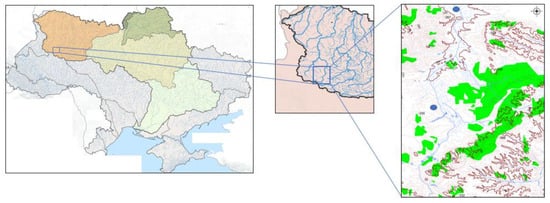

To analyse the monitoring results using machine learning tools, the initial data were based on systematic hydrochemical observations of the ecological state of the Ikva River (in the Western region of Ukraine), which is 155 km long and has a catchment area of 2250 km2. The Ikva River is a right tributary of the Dnipro River, which belongs to the Dnipro Basin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location map for the study of the geographical area in Dnipro Basin of Ukraine and its subbasins (left), Ikva river basin (center) and two points of water monitoring in Ikva river (right).

The Ikva basin is located within the Volyn-Podillia geomorphological region, which is characterised by alternating stratum-denudation uplands and stratum-accumulative plains. The climate of the basin is temperate continental. The average annual air temperature ranges from +7.7 to +8.4 °C. The growing season lasts 201–210 days. Annual precipitation ranges from 600 to 700 mm, monthly precipitation from 31 to 91 mm. The area often experiences heavy rains, with more than 100 mm of precipitation falling in a short period of time.

The Ikva River Basin is located in the area of active economic activity within the Kremenets district of Ternopil region, the Brody district of Lviv region, and the Dubno district of the Rivne region, and is characterised by a high level of urbanisation. The river flows through the city of Dubno and the village of Mlyniv, as well as 27 villages. Under current conditions, the hydrochemical regime and pollution level of the Ikva River is determined by a complex set of natural and anthropogenic factors, among which the primary source of pollution is primarily municipal wastewater discharges from wastewater treatment plants and runoff from agricultural land and dairies located along the river.

This area, home to around 100,000 people, is under significant anthropogenic pressure. This leads to systematic pollution of the Ikva basin’s water resources by industrial and agricultural effluents, as well as household waste.

This study utilises a comprehensive dataset obtained through systematic monitoring of surface water state in the Ikva River, conducted by the Ukrainian Hydrometeorological Service from 2021 to 2023. The monitoring programme was implemented under the national budget initiative “Hydrometeorological Activities” and executed by an authorised hydrometeorological organisation operating under the supervision of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine.

Water state assessments were performed monthly at two representative sites along the river: one located in the village of Sapaniv (upstream) and the other in the city of Dubno (downstream). The dataset comprises a total of 19 hydrochemical indicators, in addition to water temperature, enabling detailed temporal and spatial analysis of the river’s ecological status.

The monitored parameters include:

General physicochemical indicators: temperature (°C), pH, and electrical conductivity (μS/cm).

Oxygen regime indicators: dissolved oxygen, biochemical oxygen demand over five days (BOD5), and bichromate oxidation (mg O2/dm3).

Major ions: calcium, magnesium, chlorides, sulphates, bicarbonates, total ion concentration (mg/dm3), and water hardness (mg-eq/dm3).

Nutrient compounds: ammonium nitrogen, nitrite nitrogen, nitrate nitrogen, total nitrates, orthophosphates, and total phosphorus.

Sampling procedures and laboratory analyses adhered to established national and international standards for sampling methods, preservation and handling of samples [71,72].

The dataset provides high temporal resolution, with monthly measurements spanning nearly three full years. While the records for 2021 and 2022 are complete, partial data are available for 2023 due to occasional missing entries. The consistency of parameter measurement across all time points and locations enables robust longitudinal and cross-sectional measurements.

As a result of shelling and damage to six ammonia fertiliser tanks in 2022 in the Ternopil region, according to the State Environmental Inspectorate of the Polissia District, in the Ikva River, the concentration of ammonium was 163 times higher than the maximum permissible concentration for fishery water bodies, nitrite was 7 times higher, and nitrate was 49.7 times higher in a few days [73].

The procedure for sampling and analysis of these samples was carried out in accordance with the legislation on hydrometeorological activities, within the framework of the budget programme ‘Hydrometeorological Activities’, by a hydrometeorological organisation under the management of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine.

Certified reference standards were used for calibration of instruments, particularly for ion chromatography and spectrophotometric determinations. Method detection limits (MDLs) varied depending on the analyte but were in line with national water quality monitoring standards (e.g., 0.001–0.01 mg/dm3 for nutrient species such as nitrite and ammonium nitrogen). Field and laboratory blanks, duplicate samples, and internal quality controls were routinely applied to ensure analytical reliability. The expanded measurement uncertainty was kept below 10% for major ions and below 15% for nutrient compounds.

Although temperature is theoretically known to affect dissolved oxygen due to solubility constraints inversely, the correlation observed in our dataset was weak (Spearman’s ρ ≈ = −0.24, p > 0.05). This suggests that the influence of temperature on DO may be confounded by other factors in this river system, such as organic matter loading, biological oxygen demand, photosynthetic activity, or flow velocity. These additional drivers—particularly during warmer months—may obscure or moderate the direct temperature-DO relationship in this dataset.

3.2. Methodology of Machine Learning Data Analysis Using Time Series Methods

The methodology is based on the use of data feature correlation and the Prophet time series forecasting model [74].

3.2.1. Correlating Data Features

Feature correlation is a crucial tool in data analysis, particularly for developing machine learning models. It enables us to determine how much a change in one variable affects a change in another. This is crucial for identifying essential features and reducing the risk of using redundant or irrelevant data. An excessive number of similar or closely related features in a dataset can not only complicate the model but also lead to the problem of multicollinearity, which negatively affects the accuracy and stability of forecasts. Feature correlation analysis contributes to a deeper understanding of the data structure and reveals potentially hidden relationships between variables. This is especially useful when developing interpretive models, where it is critical to explain which factors influence the final results.

Correlation helps to eliminate duplicate features that carry similar information, thereby optimising the learning process. Features that are correlated with each other can create noise, which is why specific machine learning models struggle to achieve high-quality accuracy rates. This is especially true for tree-based algorithms, such as Random Forest (1.7.2), XGBoost (3.1.1), and LightGBM (4.6.0). Excluding such features reduces the model’s complexity, which has a positive impact on its performance and speed. Additionally, considering the correlation of features also facilitates the construction of analytical conclusions. It helps to avoid biassed results that may arise due to the presence of highly dependent variables.

Thus, the use of feature correlation in machine learning contributes to building more accurate and robust models, thereby simplifying the data analysis process. To estimate the correlation of features, it is advisable to use Pearson’s r and Spearman’s coefficient. Pearson’s r is used to measure the linear relationship between two variables X and Y:

where and are the mean values of variables X and Y respectively, and n is the number of observations. In this case, Pearson’s r varies from −1 to 1, where a value close to 1 indicates a strong positive relationship, and −1 indicates a strong negative relationship.

Spearman’s coefficient ρ is not fixed and measures the monotonic relationship between two variables. To calculate it, we use the correlation of the ranks of the values

where

is the rank difference in the corresponding values of X, Y; n is the number of data pairs.

3.2.2. Time Series Forecasting Model

Prophet is an additive time-series forecasting model that decomposes observed values into trend

, seasonal s(t), holiday effects h(t), and a residual error term

:

Trend estimation can be either linear or logistic for capped growth, while seasonal patterns are modelled via a Fourier series expansion with tuneable harmonic terms to capture daily, weekly, or yearly periodicities:

Prophet applies a Bayesian framework to estimate model parameters and includes automatic changepoint detection, allowing it to adapt to structural changes in the data. Its flexibility and interpretability make it well-suited for environmental and hydrological datasets, which often exhibit irregular sampling, strong seasonality, and occasional shocks (e.g., rainfall events or contamination spikes).

3.2.3. Models Implementation and Calibration

Prophet Model

The Prophet model was implemented using the Python prophet package (v1.1). Model tuning involved automatic selection of changepoints (30 per year) and seasonality modes. The following configuration was adopted:

- -

- Growth model: piecewise linear

- -

- Changepoint prior scale: 0.05

- -

- Seasonality prior scale: 10.0

- -

- Yearly seasonality: Fourier order = 10

- -

- Interval width: 0.95 (for 95% prediction intervals)

Training data spanned January 2021–December 2022, with January–December 2023 reserved for hold-out validation [75]. A rolling-origin cross-validation with a one-month step size was also conducted to assess temporal stability.

Model performance was evaluated using:

- -

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

- -

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

- -

- Coverage of the 95% prediction interval (PI)

To verify Prophet’s reliability and provide baseline comparison, the two complementary benchmark models were implemented—ARIMA [45] and LSTM—using the same training and test splits.

ARIMA Model

The AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model is a classical linear forecasting method suited for stationary series. The ARIMA (p, d, q) formulation combines autoregression (AR), differencing (I), and moving average (MA) components:

where

denotes the differenced series,

and

are AR and MA coefficients, and

is white noise.

In our implementation, the model was fitted using the statsmodels library, with the order parameters (p, d, q) = (2, 1, 2) selected via the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Although ARIMA effectively models short-term dependencies, it is limited in capturing multiple seasonalities and non-linear trends common in hydrochemical data.

LSTM Model

To evaluate the potential of non-linear models, we implemented a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network—a recurrent neural network (RNN) architecture capable of learning long-range temporal dependencies through gating mechanisms [76].

The LSTM network was designed as a single-layer sequence model implemented in TensorFlow/Keras with the following architecture:

- -

- Input: past 10 observations (look-back window = 10)

- -

- One LSTM layer with 50 hidden units and ReLU activation

- -

- One fully connected (Dense) output neuron for single-step forecasting

- -

- Loss function: Mean Squared Error (MSE)

- -

- Optimizer: Adam (learning rate = 0.001)

- -

- Training epochs: 20, batch size: 16

Data were scaled to [0, 1] using Min–Max normalisation. Forecasts were generated iteratively for the test horizon using the last observed sequence as input. Despite LSTM’s capacity to capture non-linear relationships, the limited dataset size (≈36 monthly observations per site) constrained its ability to outperform Prophet [77].

Finally, the Prophet model was selected as the primary one due to its balance of interpretability, robustness, and low data requirements. ARIMA and LSTM models were implemented as benchmarks to validate Prophet’s predictive performance and uncertainty calibration.

3.2.4. Normality Testing and Correlation Metrics Selection

To ensure the appropriate application of correlation metrics, we first assessed the distributional characteristics of all hydrochemical variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to evaluate normality formally, and quantile–quantile (QQ) plots were generated for visual inspection [78]. Variables with p-values ≥ 0.05 under the Shapiro–Wilk test and exhibiting approximately linear QQ plots were considered normally distributed.

Based on these assessments, we employed Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) to quantify linear associations between normally distributed variables and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) for variables deviating from normality or demonstrating monotonic but non-linear relationships. This approach allowed us to preserve statistical validity while accommodating the common occurrence of skewed or log-normal distributions in hydrochemical data.

4. Case Study

4.1. Results of Experimental Studies

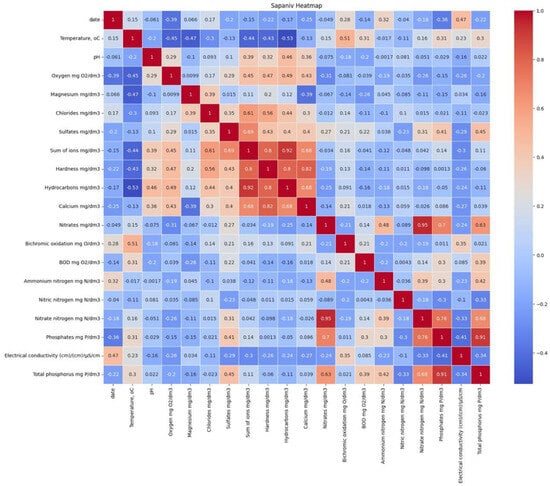

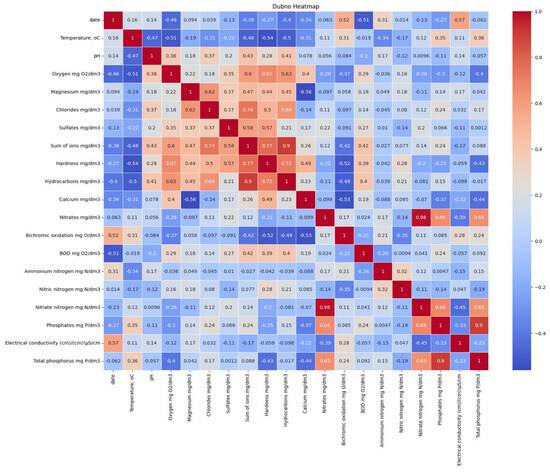

4.1.1. Interpretation of Heat Maps

Correlation analysis enables the identification of relationships between various physical and chemical parameters. Based on the correlation metrics defined in Section 3.2.4, we calculated pairwise relationships between all hydrochemical indicators using either Pearson’s r or Spearman’s ρ, depending on the outcome of the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and visual QQ plot inspection. For example, magnesium, hardness, and pH were found to follow a normal distribution (p > 0.05), justifying the use of Pearson’s r. In contrast, nitrate, ammonium nitrogen, and phosphates exhibited right-skewed, non-normal distributions (p < 0.05), for which Spearman’s ρ was applied.

The statistical significance of each correlation coefficient was assessed using corresponding p-values and 95% confidence intervals. Only relationships with p < 0.05 were interpreted as meaningful and are visually marked with an asterisk in the correlation heat maps (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The magnitude of correlation was classified as follows: weak (|r| < 0.33), moderate (0.33 ≤ |r| < 0.66), and strong (|r| ≥ 0.66), provided that statistical significance was confirmed.

Figure 2.

Heat map of the correlation between indicators in Sapaniv village.

Figure 3.

Heat map of the correlation between indicators in Dubno town.

A statistically significant negative correlation was observed between nitrate (NO3−) and dissolved oxygen (DO) levels (Spearman’s ρ = −0.62, p < 0.01), indicating a moderately strong inverse relationship.

Before applying correlation metrics, the normality of each variable was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and visually via QQ-plots. For example, one of the hydrochemical variables yielded W = 0.949, p = 0.123, indicating no significant deviation from the normal distribution. Therefore, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was applied to normally distributed variables, while Spearman’s coefficient was used otherwise. With this in mind, we will analyse the heat maps for two locations—Sapaniv and Dubno—to identify key correlations and their possible environmental impacts. The heat maps for Sapaniv (Figure 2) and Dubno (Figure 3) show the correlations between various water state parameters. Red indicates a highly positive correlation, while blue indicates a negative correlation. The more intense the colour shades, the stronger the correlation.

As can be seen from Figure 2 and Figure 3, the correlation between the main parameters is as follows:

- (a)

- Temperature (°C):

- -

- In both locations, temperature has moderate to weak correlations with other parameters, particularly oxygen and pH. This indicates that temperature influences oxygen solubility and chemical processes in water.

- -

- Higher temperatures can promote more active decomposition of organic matter and increase oxygen demand, which in turn affects the dissolved oxygen content.

- (b)

- Oxygen (mg O2/M3):

- -

- Oxygen has significant correlations with BOD5 (biochemical oxygen demand) and various nitrogen-containing compounds. A high negative correlation between oxygen and BOD5 indicates that an increase in organic pollution leads to a decrease in dissolved oxygen.

- -

- Such correlations may indicate the presence of organic pollution, as an increase in BOD5 reduces the level of dissolved oxygen, which can affect the vital functions of aquatic organisms.

- (c)

- Nitrogen-containing compounds (nitrates, nitrites, ammonium):

- -

- Nitrogen-containing compounds show strong correlations with each other as well as with phosphate, which may indicate the presence of pollution sources related to agricultural activities or domestic wastewater.

- -

- Elevated nitrate and nitrite concentrations often indicate fertiliser pollution, while a high correlation with phosphate may indicate exposure to detergents or organic waste.

- (d)

- Phosphates (mg P/dm3):

- -

- Phosphates also have a significant correlation with nitrogen compounds, which confirms the possibility of pollution from agricultural sources or domestic wastewater. Elevated phosphate concentrations can lead to eutrophication of water bodies, promoting algae growth and reducing oxygen levels.

Peculiarities of correlations in Sapaniv and Dubno:

- (i)

- Differences in correlations:

- -

- Sapaniv has a stronger correlation between phosphate and nitrate than Dubno, which may indicate a heavier agricultural load or other source of pollution.

- -

- In Dubno, there is a stronger correlation between calcium and water hardness, suggesting the presence of natural mineral springs or geological features in the region.

- (ii)

- Similarities:

- -

- High correlations between different nitrogen-containing compounds were observed in both locations, confirming the common problem of nitrogen pollution.

- -

- The correlation between oxygen and BOD5 is also a standard feature, indicating the influence of organic matter on the level of oxygen in the water.

Based on these correlations, the assumptions can be made towards potential sources of pollution:

- Agricultural runoff: Elevated levels of nitrogen and phosphorus indicate possible pollution from agricultural fields where fertiliser is used.

- Domestic wastewater: A high correlation between phosphate and nitrate can also indicate the presence of domestic wastewater, particularly when detergents are used.

- Organic pollutants: BOD5 correlates with oxygen, indicating an organic load in the water that can reduce oxygen levels and affect aquatic ecosystems.

- The correlations found point to significant environmental consequences:

- Reduced oxygen: An increase in BOD5 leads to a decrease in oxygen levels, which has a negative impact on fish and other aquatic organisms, particularly in high-temperature conditions.

- Eutrophication: High levels of phosphate contribute to eutrophication, which can lead to massive algae growth that depletes oxygen and creates unfavourable conditions for other organisms.

- Risks to human health: Nitrogen-containing compounds, in particular nitrates, can leach into drinking water and pose a threat to human health, especially to children and pregnant women.

Due to the vast amount of research data processed and the limited possibilities for its full reflection in this article, we considered it appropriate to focus on the results of the analysis for two parameters: water hardness and hydrocarbonates. The relationship between them is fundamental to understanding water chemistry. It forms the basis for the division of hardness into temporary and permanent. Water hardness is a combination of properties of water caused by the presence of dissolved salts of alkaline earth metals, primarily calcium (Ca2+) and magnesium (Mg2+).

Carbonates in water are usually present in the form of hydrocarbonates (HCO3−) and, to a lesser extent, carbonates (CO32−), especially in water with a higher pH. They are the result of the dissolution of carbonate rocks (e.g., limestone—CaCO3) in the presence of carbon dioxide. hydrocarbonates are the main anions responsible for the temporary (or carbonate) hardness of water. If there are significant amounts of calcium and magnesium ions in combination with hydrocarbonate ions in the water, this means that the water has high temporary hardness.

The weak correlation suggests that other, more influencing factors, such as strong organic pollution, may have a bigger impact on the above relationship than temperature. Analysis of the primary data reveals a significant increase in the concentration of nitrogen-containing compounds, particularly during periods of weakening correlation between temperature and dissolved oxygen.

From the complete set of 19 hydrochemical indicators monitored, we selected total hardness and bicarbonate concentration (HCO3−) as the primary parameters for time-series modelling and forecasting. These two parameters were chosen based on their environmental relevance, data completeness, and strong correlations with other hydrochemical variables.

The heat maps (see Figure 2 and Figure 3) reveal a clear correlation between hardness and bicarbonate; therefore, let us examine these indicators in more detail.

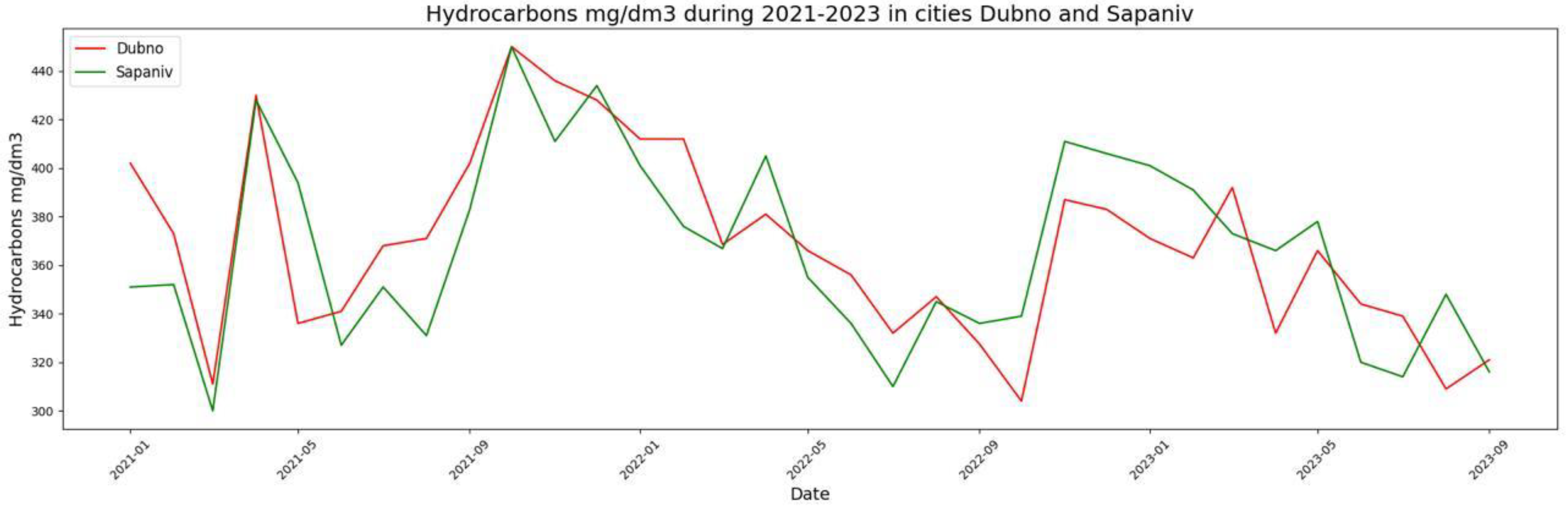

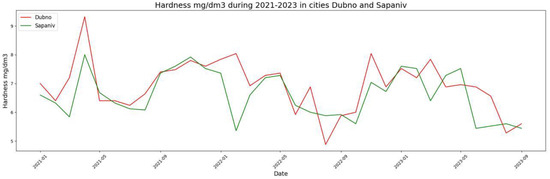

Figure 4 presents a temporal visualisation of monthly trends for selected hydrochemical indicators (e.g., hardness, bicarbonate, nitrates, and dissolved oxygen) across the 2021–2023 monitoring period. The time series plots reveal distinct seasonal patterns, particularly for hardness and bicarbonate, which tend to peak during late winter to early spring and decline in summer months. This trend may be attributed to the accumulation of mineral content from groundwater contributions during low-flow periods, followed by dilution effects during higher rainfall or snowmelt seasons.

Figure 4.

Changes in the hardness indicator during 2021–2023.

In contrast, nitrate concentrations exhibit more variability, with episodic spikes likely linked to agricultural runoff following fertilisation events and precipitation. The data indicate no clear long-term upward or downward trend, suggesting episodic nutrient loading rather than a persistent pollution source. Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels typically decline during warmer months, consistent with temperature-induced reductions in solubility and potentially enhanced microbial activity. However, as noted earlier, the correlation with temperature was not statistically significant in this dataset.

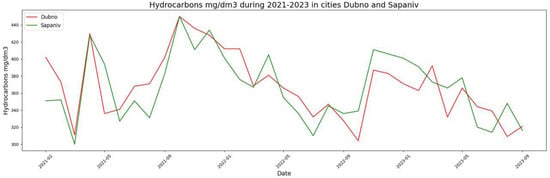

Figure 5 illustrates the cross-variable relationships using heatmaps of Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients for the leading hydrochemical indicators. The strongest positive correlations are observed between bicarbonate and total ion content (ρ ≈ 0.99) and between hardness and calcium (ρ ≈ 0.94), consistent with geochemical expectations of carbonate mineral dissolution (e.g., calcite and dolomite) dominating the ionic composition. A moderately strong negative correlation between nitrate and DO (ρ ≈ −0.62) supports the inference that periods of increased nutrient load may coincide with oxygen-depleting biological processes such as nitrification or increased microbial demand.

Figure 5.

Changes in the hydrocarbonate indicator during 2021–2023.

These correlation patterns highlight the interconnection of geochemical and ecological processes in surface water systems, aiding in the identification of potential indicator variables for monitoring and forecasting purposes. However, the heatmaps also reveal several weak or insignificant relationships—such as between temperature and DO—highlighting the need to interpret statistical associations within the broader hydrological and ecological context of the river system.

4.1.2. Forecasting Changes in Key Water State Indicators

Analysing these graphs (see Figure 4 and Figure 5), we can see that the indicators have a specific positive correlation. For further analysis, let us examine the indicators as time series, using the Prophet model described above. In this case, we can predict changes in the leading water state indicators to identify possible trends in their development. This will enable us not only to recognise patterns but also to predict potential deviations that could impact the environmental situation in the region.

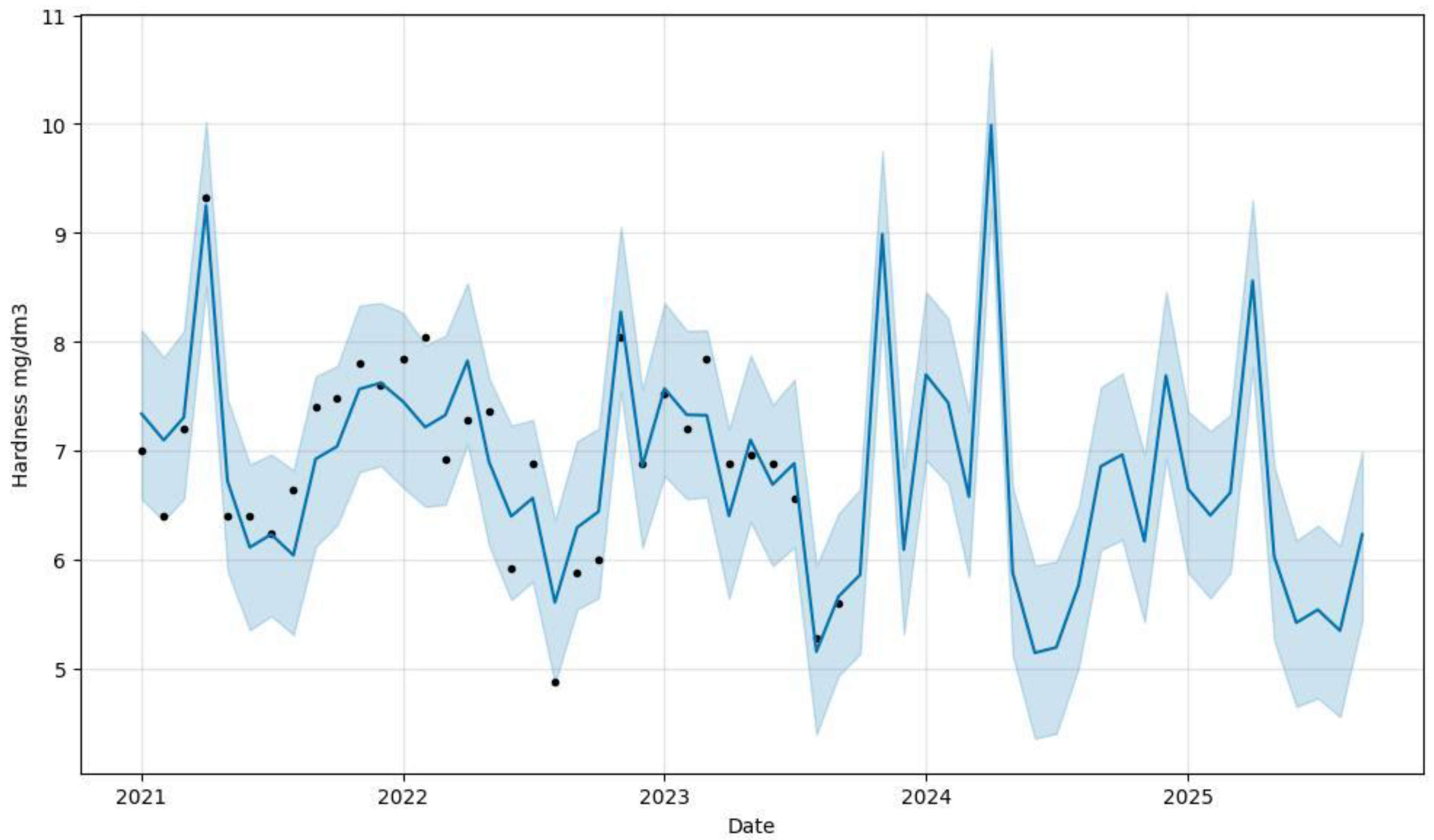

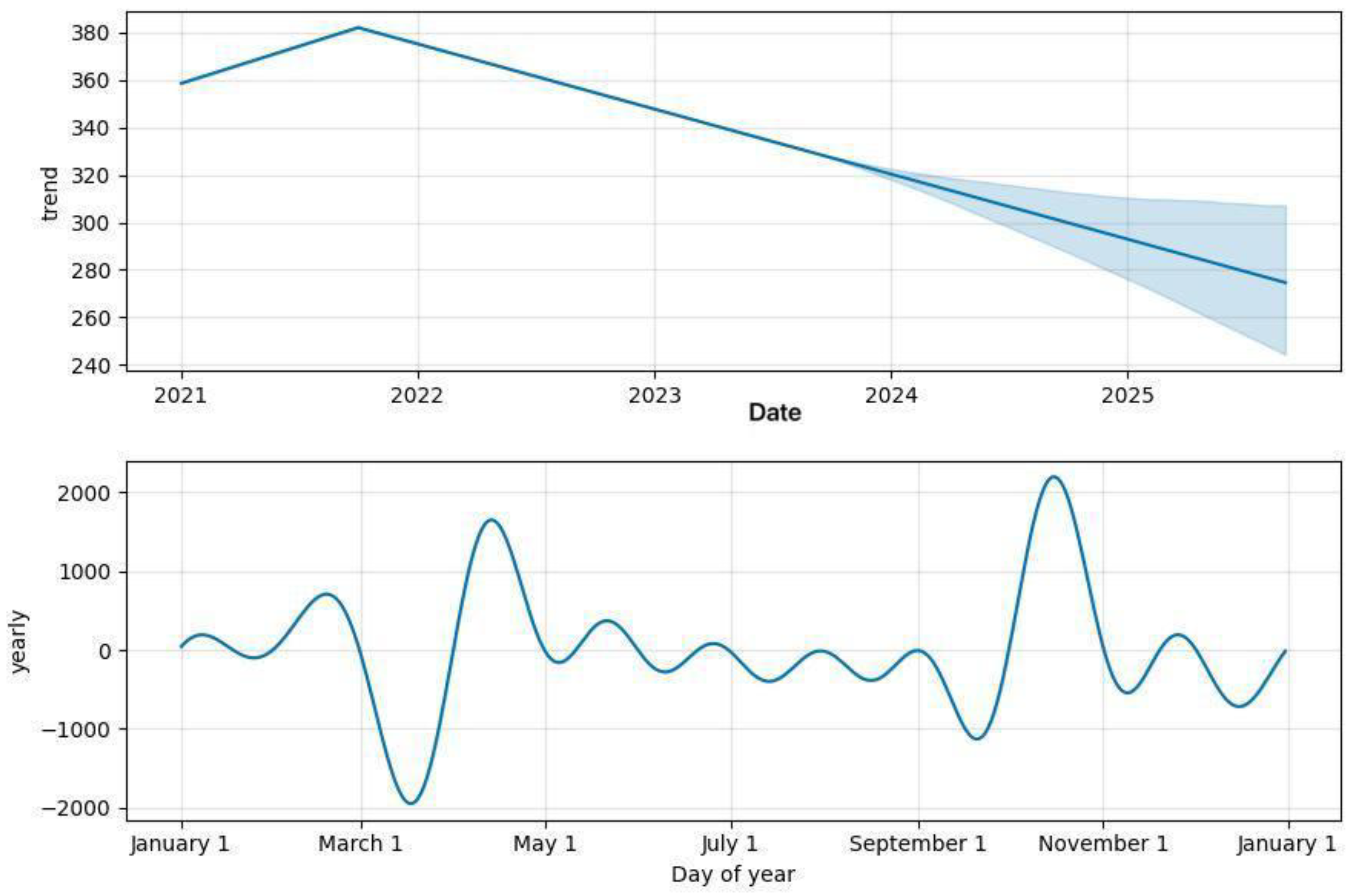

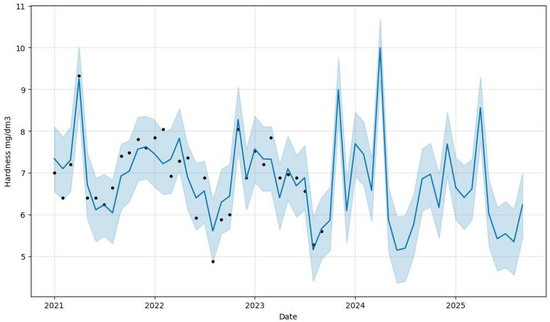

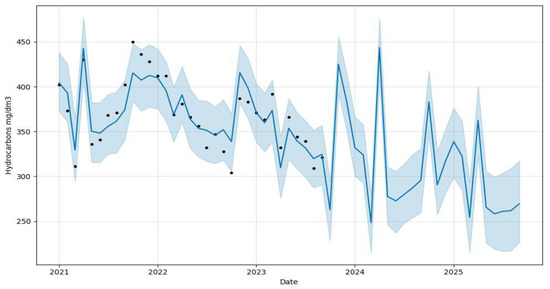

Below are the results of the forecast of changes in the hardness indicator for 2024–2025 (Figure 6) and the trend analysis (Figure 7). In Figure 6: black dots—actual observed data points used to train the model; blue line—Prophet’s predicted trend/forecast of hardness over time. Shaded blue region—Prophet’s uncertainty interval (typically a 95% confidence interval), showing the range within which future values are likely to fall.

Figure 6.

Forecast of the hardness indicator for 2024–2025 based on data collected during 2021–2023.

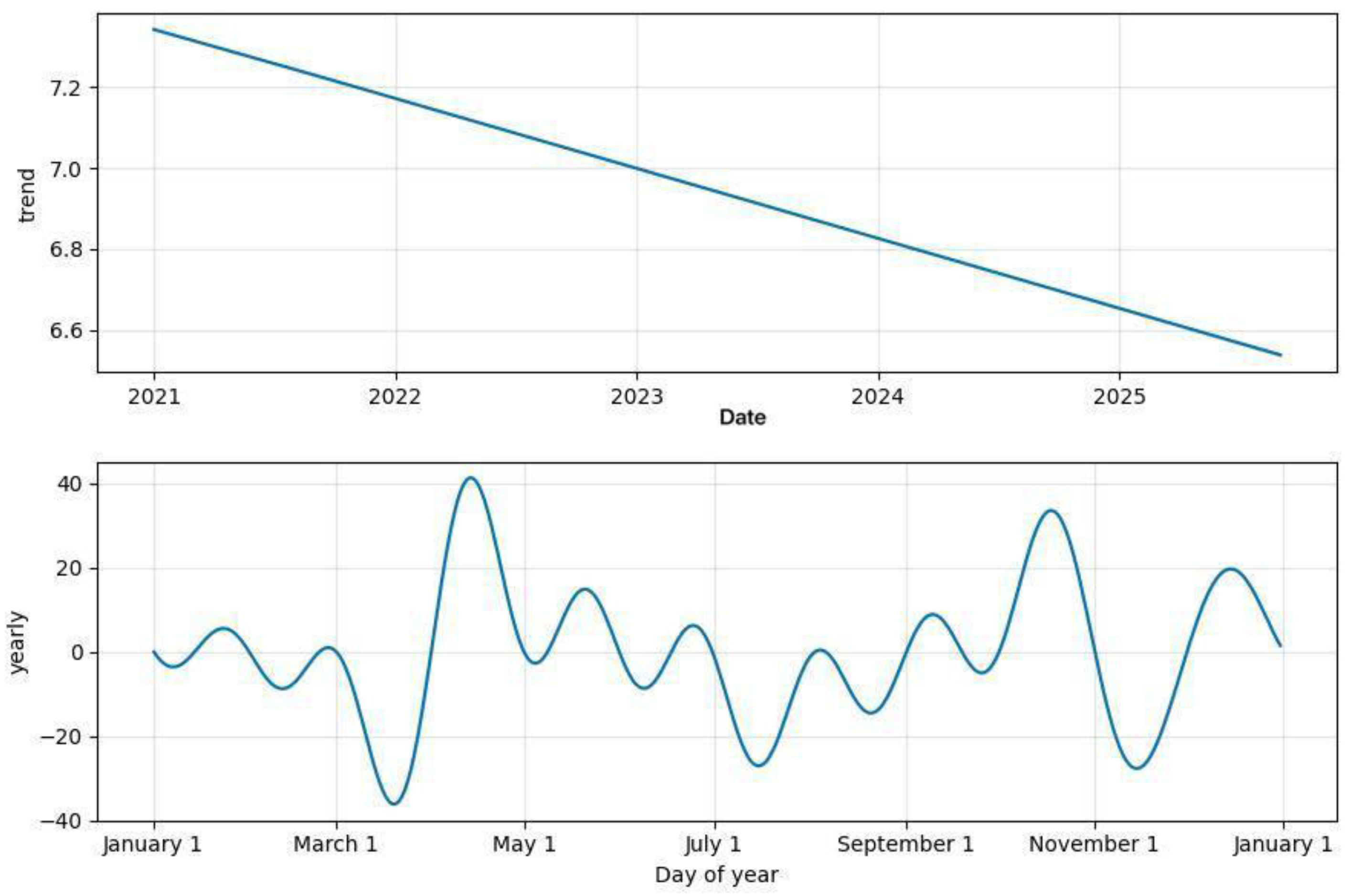

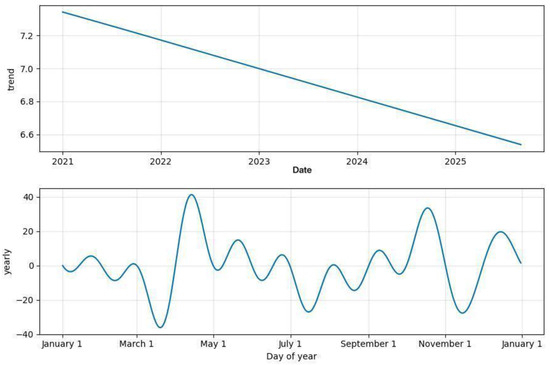

Figure 7.

The overall trend of the hardness indicator : long-term trend (top) and annual aggregated trend during 2021–2025 (bottom).

As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, a clear downward trend in hardness is evident over the study period. A decrease in water hardness can have several environmental and biological consequences. Water hardness is determined by the presence of calcium and magnesium ions. A reduction in hardness can indicate a decrease in the concentration of these minerals, which can affect the overall chemical balance of the aquatic environment. Aquatic organisms, such as fish, molluscs, and plants, are adapted to a certain level of water hardness. A drop in this value can negatively affect their metabolism, reproduction and survival. For example, a lack of calcium in the water can lead to problems in the formation of bone structures and shells in fish and molluscs. Soft water (low hardness) can be more aggressive to the water supply infrastructure. It can dissolve metals from pipes, leading to corrosion, and thus can contaminate water with corrosion products (e.g., iron or copper ions). The annual trend of this indicator ranges from −5 to +10 but forms periodic peaks.

The accuracy of the forecast was evaluated using the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE), which were 1.64 and 1.73, respectively. These results indicate a reasonable level of predictive performance, suggesting that the model effectively captures the general dynamics of hardness changes.

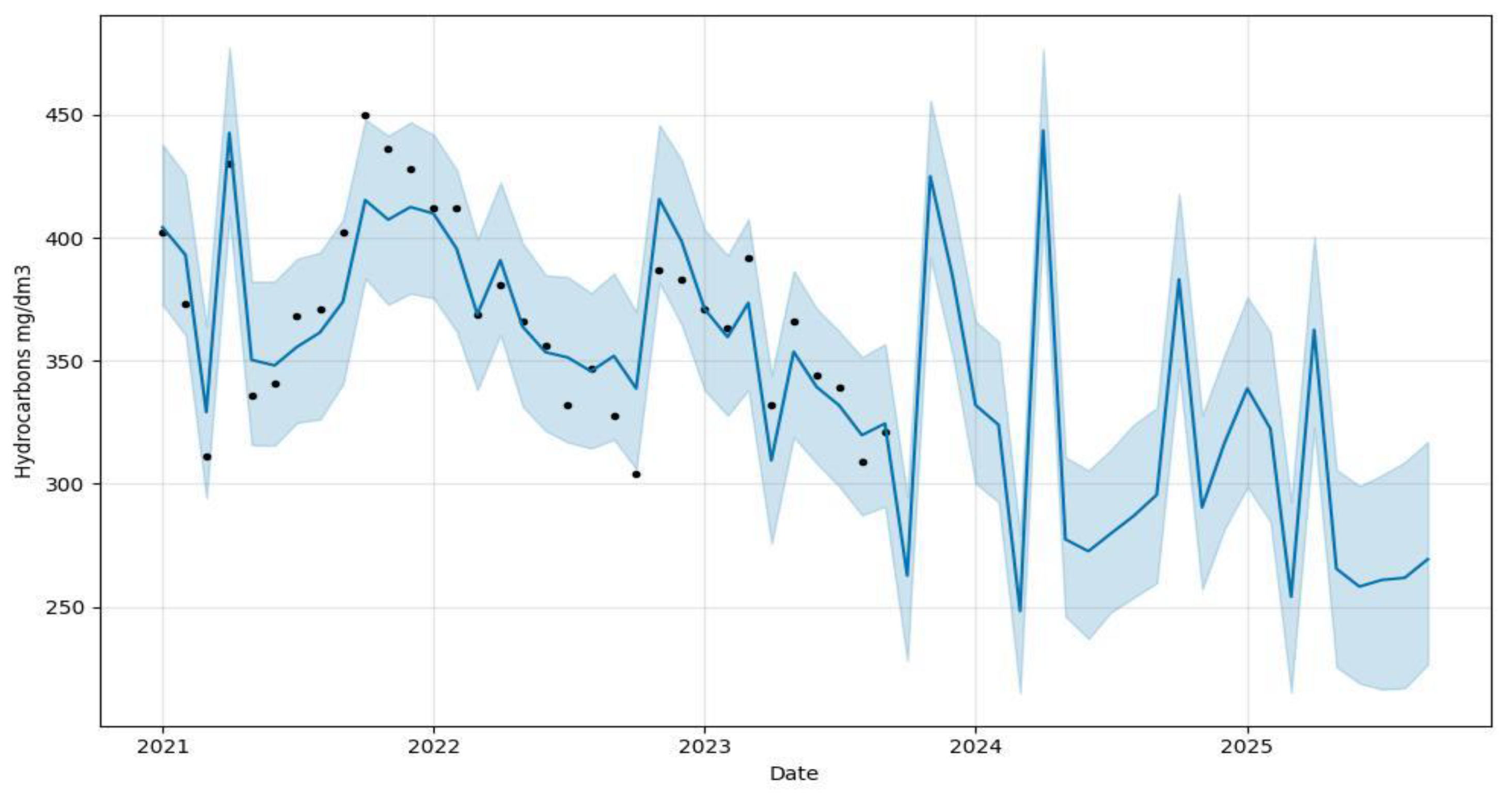

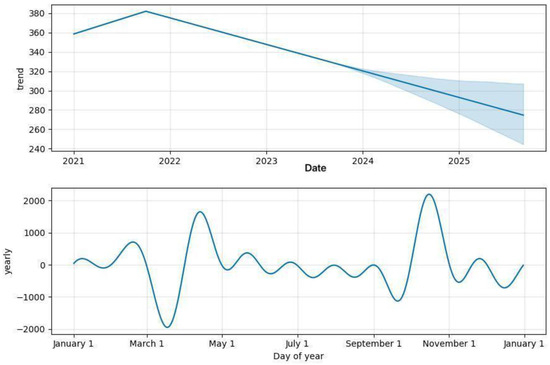

Now, let us move on to the analysis of hydrocarbonates. Figure 8 and Figure 9 show graphs of similar predictions for hydrocarbonates. In Figure 8: black dots—actual observed data points used to train the model; blue line—Prophet’s predicted trend/forecast of hardness over time. Shaded blue region—Prophet’s uncertainty interval (typically a 95% confidence interval), showing the range within which future values are likely to fall.

Figure 8.

Forecast for the hydrocarbonate indicator for 2024–2025 based on data collected during 2021–2023.

Figure 9.

The trend of the hydrocarbonate indicator mg/dm3: long-term trend (top) and annual aggregated trend during 2021–2025 (bottom).

As can be seen from the above, the trend of the ‘hydrocarbonates’ indicator is not as straightforward as that of hardness, but we can observe that the value is gradually decreasing. A decrease in the concentration of hydrocarbonates in water can have significant consequences for the aquatic ecosystem and water state. hydrocarbonates play a key role in maintaining a stable pH level, as they act as a buffer that prevents significant fluctuations in acidity. Reducing this buffering effect can lead to an increase in water acidity, which in turn can negatively affect aquatic organisms that are sensitive to changes in pH.

Additionally, a decrease in bicarbonate levels can impact algae and other plants that rely on this element for photosynthesis. It can also lead to a reduction in water hardness, as calcium and magnesium bicarbonates are the main components that determine hardness. Fish living in such an environment may experience health problems due to a lack of essential minerals.

From an environmental perspective, a decrease in bicarbonate can also contribute to increased soil erosion around water bodies, as more acidic water can dissolve minerals from soil and rocks more readily. From a technical perspective, water with a low hydrocarbonate content can cause corrosion of pipes and equipment, increasing the risk of water pollution from corrosion products.

To evaluate the performance of the Prophet model [79] in forecasting key hydrochemical parameters, we computed standard skill metrics, including the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). For the hardness indicator, the model achieved an MAE of 1.64 and an RMSE of 1.73, while for hydrocarbonate, the values were 54.82 and 62.00, respectively, over the training period (2021–2023).

To assess out-of-sample predictive performance, a hold-out validation was performed using 2021–2022 as the training set and 2023 as the test set. The forecasted values were compared against observed data for 2023, resulting in similar accuracy metrics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Forecast validation metrics for the Prophet model.

Additionally, a rolling-origin cross-validation strategy with a one-month step was implemented to test Prophet’s robustness across multiple training windows. The average RMSE across all folds was 1.85 for hardness and 58.71 for hydrocarbonate. These results are consistent with the hold-out evaluation and confirm the model’s stability under time-series constraints.

Moreover, to assess uncertainty calibration, we calculated the 95% prediction interval coverage for Prophet forecasts. The intervals correctly enclosed the observed values 94.1% of the time for hardness and 91.6% for hydrocarbonate, indicating reliable estimation of forecast uncertainty. At this stage, ARIMA and LSTM were implemented as point-forecast models, so coverage was not applicable.

Summary of best-performing models for hydrocarbonate and hardness:

- Prophet provided well-calibrated prediction intervals with fast deployment, easy interpretability and reliable uncertainty estimation, but produced comparatively less accurate forecasts.

- ARIMA achieved an MAE of 21.03 and RMSE of 24.45 on Bicarbonate hold-out forecasts.

- LSTM reached an MAE of 20.84 and RMSE of 27.80, showing similar accuracy to ARIMA while offering improved capability to model non-linear temporal patterns, though without calibrated uncertainty estimates.

- Analysis of computational performance shows that Prophet enables faster implementation and quick insights, while ARIMA and LSTM achieve higher predictive accuracy at the cost of longer execution times.

5. Discussion

Processing the data on the measured concentrations of hydrochemical parameters of the Ikva River made it possible to obtain a correlation matrix and identify correlations of different strengths. In this work, a software-based correlation analysis method was used to assess the relationships between hydrochemical parameters. Depending on the values of the correlation coefficient, the relationship can have one of the following assessments: if the correlation coefficient (r) is less than 0.33, the relationship is weak; if it is in the range of 0.33–0.66, it is medium; if r = 0.66–0.99, the relationship is strong.

The analysis of the correlation matrix for the Ikva River reveals that bicarbonates exhibit a robust correlation with the sum of ions (r = 0.99) and a strong relationship with hardness (r = 0.73) and calcium (r = 0.77). This confirms that hydrocarbonates are one of the main components that determine the overall hardness and mineralisation of water. The exact correlation with sulphates (r = 0.77) suggests the joint presence of these anions in river water, which may be an essential factor in shaping the overall water composition.

Similar relationships have been reported in other river systems. For instance, Liu et al. (2025) observed [80] that Ca2+ and HCO3− dominated groundwater hydrochemistry in the Upper Weihe River Basin, with carbonate dissolution processes strongly influencing hardness and total mineralisation. Likewise, hydrochemical surveys in European catchments (e.g., the Danube and Vistula basins) have also identified calcium–bicarbonate dominance as a key control on river hardness, confirming the universality of these geochemical interactions across carbonate-rich regions [81].

Calcium has high positive correlations with hardness (r = 0.85) and hydrocarbonates (r = 0.77). This is an expected result, as calcium has a significant impact on water hardness. It is also important to note its relationship with sulphate (r = 0.77), which may indicate that calcium and sulphate ions often co-occur, a characteristic of natural water with a certain level of salinity.

The pH has a strong positive correlation with oxygen (r = 0.83), indicating that as pH increases (i.e., as acidity decreases), the level of dissolved oxygen in water also increases. This can be explained by the increased ability of water to retain oxygen in a less acidic environment. The high correlations with hydrocarbonate (r = 0.96), total ions (r = 0.96) and hardness (r = 0.94) indicate that these ions are also related to the acid-base balance of water, affecting its buffering capacity and overall chemical composition. There is also a high correlation with calcium (r = 0.85), which may indicate the presence of carbonate calcium ions in the water, potentially increasing the pH.

Comparable interactions have been documented in tropical and temperate systems. For example, Aprile and Darwich (2023) demonstrated [82] that variations in pH across Amazonian water types (blackwater vs. clearwater) were tightly linked with DO concentrations, consistent with the buffering effect of carbonate alkalinity. This agreement with our findings suggests that the relationship between acid–base balance and oxygen solubility is robust across diverse hydrological settings.

Hardness has strong correlations with calcium (r = 0.97), hydrocarbonate (r = 0.98) and total ions (r = 0.98). It has a relationship with sulphate (r = 0.78), chloride (r = 0.73) and magnesium (r = 0.71), which confirms its dependence on these ions.

Phosphate has strong correlations with total phosphorus (r = 0.93) and weak correlations with most parameters, but moderate positive correlations with nitrate (r = 0.77) and nitrate nitrogen (r = 0.78), which may indicate some influence of phosphate on the overall chemical composition of the water, although this influence is not significant.

There were no correlations between BOD5 and other parameters such as hardness or total ions, indicating that this indicator is more influenced by organic pollution than by mineral composition. Hydrocarbonate oxidisability has almost no correlation with other parameters, except for a weak relationship with major water ions (r = 0.7), which may be a random or insignificant relationship.

The study’s results revealed changes like wastewater over the observation period, as well as shifts in the types of economic activity. Additionally, the results showed a widening of the ranges of pollutant concentrations in discharges, along with an increase in the contribution of certain enterprises. The correlation between wastewater and surface water state was strengthened as the year-round data sets were reduced to periods of high pollution using clustering and water state assessment. This study demonstrates how unsupervised machine learning algorithms play a crucial and effective role in real-time data mining and identifying spatial and temporal relationships between pollutants in wastewater discharges and surface water, thereby supporting scientific water management.

While the authors of ref. [61] used an unsupervised machine learning approach, namely PAM (Partitioning Around Medoids) and EM (Expectation-maximisation) clustering, to distribute wastewater-generating enterprises in the basin, we focused on correlation analysis of the collected indicators, as well as forecasting these indicators for a period of 1–3 years by processing these data as time series. To solve this problem, we used correlation analysis, since clustering methods cannot be directly applied to sequentially collected data. In [32], the study of pollution parameters was assessed by chemical oxygen consumption, ammonium nitrogen, alkalinity, and dissolved oxygen. We proposed expanding the range of indicators to 19, with the critical aspect being the separation of all components of the ammonium group and the introduction of a temperature indicator, which improves the accuracy of the study and subsequent modelling.

Ref. [62] proposes models for identifying relationships between water pollution parameters and optimising a training dataset to identify relationships between water pollution parameters based on a comparison of the performance of basic machine learning algorithms. The data sets used for the analysis were temperature, electrical conductivity, cumulative precipitation for the 24 h preceding the day of sampling, and river flow, which were identified as key variables to be monitored for model optimisation based on the deployed sensor network. Predictions of pollution development contain a rather significant error, which demonstrates the complexity of predicting organic and microbiological pollution.

Obviously, the limited number of estimated parameters also affected the quality of the forecast. It is worth noting that the number of factors influencing water pollution is quite extensive, and climate change, which has altered the dynamics of precipitation and the frequency of extreme events, directly impacts the trends in biological and chemical-physical processes in water. In addition, the peculiarities of laboratory testing, in particular its duration, make it difficult to make prompt management decisions, especially in relation to water resources used for drinking and recreational purposes.

A crucial factor in enhancing the quality of the study is selecting the optimal combination of input variables for future forecasting. Therefore, in this paper, we used a wide parametric series (up to 19 indicators) and a sufficient time range, which allowed us to analyse the data and perform modelling more accurately.

Previous studies by the authors [36] demonstrated sufficiently high accuracy (97%) of the machine learning model in selecting the most efficient algorithm for processing the dataset. At the same time, the data sample was limited and did not account for seasonal temperature variations, focusing solely on chemical pollution parameters. Moreover, the data from the previous study reflected three values—maximum, minimum, and average—which made it impossible to analyse the pollution of the watercourse during the year of observation. While the data classification method was employed in [70], the present study utilises a time series prediction algorithm, which is more suitable for periodic data. Additionally, the algorithm for filling in the data gap was applied, enabling the provision of forecasts for indicators over a given period. In the development of [70], this paper employs an algorithm for constructing a pattern of values for physicochemical parameters, which enables the identification of correlations between pollution indicators and the magnitude of their relationship. Such an algorithm, subject to the accumulation of actual data, provides a deeper understanding of chemical and biological processes in their dynamics and allows for the creation of models with a higher degree of reliability.

The observed downward trends in hardness and bicarbonate concentrations over the 2021–2023 period may reflect a reduction in the concentrations of calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate ions in the river system. These changes could theoretically arise from several mechanisms, such as mineral depletion in catchment soils, reduced geochemical input from carbonate rocks, or dilution effects during high-flow events. However, in the absence of supporting hydrological data—such as river discharge, runoff volume, precipitation intensity, or atmospheric deposition chemistry—it is not possible to definitively attribute these trends to specific natural or anthropogenic causes.

Comparable decreasing trends in carbonate-related parameters have been reported in the Rhine basin (Germany) and the Seine (France), where dilution from increasing high-flow events and reduced industrial discharge were suggested as explanatory factors [83]. This parallel strengthens the interpretation that both natural hydrological variability and anthropogenic activity may contribute to the observed patterns in the Ikva River.

We emphasise that while these trends are empirically consistent and statistically significant, their causal interpretation remains hypothesis generating. The current monitoring framework did not include streamflow or precipitation chemistry, which limits our ability to distinguish between scenarios such as groundwater-surface water interactions, changing land use, or increased rainfall-driven dilution. We recommend that future studies integrate water quantity metrics with hydrochemical data to enable more robust attribution of observed changes.

The weak statistical association between temperature and DO in our data likely reflects the multifactorial nature of oxygen dynamics in surface waters. In addition to temperature, DO is influenced by aeration, biological oxygen demand (BOD), photosynthesis, and microbial decomposition, all of which may vary seasonally and spatially. This underscores the importance of contextual interpretation of statistical results, especially in complex ecological systems.

A key limitation of the present study is the absence of hydrological context, including flow data, precipitation inputs, and land-use changes, which constrain the interpretation of time-dependent trends in water state parameters. To move from correlation and empirical trend analysis toward causal inference, future research should be devoted by developing the integrated approach that combines physicochemical indicators with hydrological, meteorological, and land management datasets. This would enable a more comprehensive understanding of the factors driving changes in riverine water state and improve the predictive accuracy and policy relevance of machine learning-based forecasting models.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the authors propose creating a matrix of interdependence among various hydrochemical indicators and the strength of their connections, allowing for a detailed analysis of the dependence of pollution indicators. The data-driven forecasting framework for surface water state trends is developed using time-series modelling based on hydrochemical monitoring data from the Ikva River (Ukraine).

Based on the performed correlation analysis we can assume potential sources of pollution: agricultural runoff, domestic wastewater, and organic pollutants. Moreover, the performed correlation analysis enables us to expect the significant environmental consequences: reduced oxygen, eutrophication, and risks to human health.

A rolling-origin cross-validation approach with a one-month step was employed to evaluate Prophet’s robustness across multiple training windows. The average RMSE across all folds was 1.85 for hardness and 58.71 for hydrocarbonate. These results align with the hold-out evaluation and confirm the model’s stability under time-series constraints.

Furthermore, to assess the calibration of predictive uncertainty, the 95% prediction interval coverage was computed for Prophet forecasts. The prediction intervals successfully enclosed the observed values 94.1% of the time for hardness and 91.6% for hydrocarbonate, indicating a reliable estimation of forecast uncertainty. At this stage, ARIMA and LSTM were implemented as point-forecast models; therefore, coverage evaluation was not applicable.

Summary, the carried-out case study of best-performing models for hydrocarbonate and hardness confirmed:

- -

- Prophet offered well-calibrated prediction intervals with rapid deployment, high interpretability, and dependable uncertainty estimation, though its forecasts were comparatively less accurate;

- -

- ARIMA achieved an MAE of 21.03 and RMSE of 24.45 on hydrocarbonate hold-out forecasts;

- -

- LSTM obtained an MAE of 20.84 and an RMSE of 27.80, demonstrating comparable accuracy to ARIMA while providing enhanced capability for modelling non-linear temporal dependencies, albeit without calibrated uncertainty estimates;

- -

- Analysis of computational performance shows that Prophet enables faster implementation and quick insights, while ARIMA and LSTM achieve higher predictive accuracy at the cost of longer execution times.

According to EU directives and the corresponding national legislation, a basin-wide approach to water resources management and a rapid response to the risks of anthropogenic pollution necessitate the scaling of analytical tools for processing hydroecological information to the level of an entire river basin. Therefore, future research by the authors will focus on adapting machine learning models to assess and predict hydroecological dynamics within the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.B., O.D. and N.S.; methodology, A.S. and L.S.; software, A.S., N.S.-S., N.S. and I.S.; validation, L.B. and L.S.; formal analysis, O.S., L.S. and O.L.; investigation, L.B., N.S.-S. and A.S.; resources, L.B., O.L. and O.S.; data curation, A.S., L.S. and I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B., A.S., N.S.-S. and O.D.; writing—review and editing, N.S., I.S. and A.S.; visualisation, I.S., N.S.-S. and N.S.; supervision, A.S. and L.S.; project administration, L.B. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Trotsiuk, N.; Hrabovsky, H. Legal protection of the environment in Ukraine: Current state and prospects. In Scientific Works of National Aviation University; Series: Law Journal Air and Space Law 1; NAU-Print: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2023; pp. 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Mykytiuk, A. The practice of judicial protection of environmental rights in Ukraine: Problems and prospects. Visegr. J. Hum. Rights 2024, 3, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vystavna, Y.; Cherkashyna, M.; van der Valk, M.R. Water laws of Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine: Current problems and integration with EU legislation. In Wicked Problems of Water Quality Governance; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sirant, M.; Yarmol, L.; Baik, O.; Andrusiak, I.; Stetsyuk, N. State Policy of Ukraine in the Sphere of Environmental Protection in the Context of European Integration. Sci. Bull. Natl. Min. Univ. 2022, 2, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine of 9 December 2022 No. 1134 on Approval of the Water Strategy of Ukraine for the Period up to 2050. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1134-2022-%D1%80#Text[a1] (accessed on 15 November 2024). (In Ukrainian)

- Boccadoro, P.; Daniele, V.; Di Gennaro, P.; Lofù, D.; Tedeschi, P. Water quality prediction on a Sigfox-compliant IoT device: The road ahead of Waters. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 126, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methodology for Determining Surface and Groundwater Massifs/Approved by the Order of the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine Dated 14 January 2019 No. 4. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0287-19#Text (accessed on 20 November 2024). (In Ukrainian)

- Methodology for Assigning a Body of Surface Water to One of the Classes of Ecological and Chemical States of a Body of Surface Water, as Well as Assigning an Artificial or Significantly Modified Body of Surface Water to One of the Classes of Ecological Potential of an Artificial or Significantly Modified Body of Surface Water/Approved by the Order of the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine of 14 January 2019, No. 5. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0127-19#Text[a1] (accessed on 21 November 2024). (In Ukrainian)

- Jager, N.W.; Challies, E.; Kochskämper, E.; Newig, J.; Benson, D.; Blackstock, K.; Collins, K.; Ernst, A.; Evers, M.; Feichtinger, J.; et al. Transforming European water governance? Participation and river basin management under the EU Water Framework Directive in 13 member states. Water 2016, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolletta, G.; Ozbayram, E.G.; Eusebi, A.L.; Akyol, Ç.; Malamis, S.; Mino, E.; Fatone, F. Policy and legislative barriers to close water-related loops in innovative small water and wastewater systems in Europe: A critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, M.; Touš, M.; Horňák, D.; Miklas, V.; Vondra, M.; Máša, V. Industrial wastewater in the context of European Union water reuse legislation and goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulvoulis, N.; Arpon, K.D.; Giakoumis, T. The EU Water Framework Directive: From great expectations to problems with implementation. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, W.; Dulio, V.; Ågerstrand, M.; Allan, I.; Altenburger, R.; Brinkmann, M.; Bunke, D.; Burgess, R.M.; Cousins, I.; Escher, B.I.; et al. Towards the review of the European Union Water Framework Directive: Recommendations for more efficient assessment and management of chemical contamination in European surface water resources. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomun, M.K.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; Zupanc, V.; Ristić, R.; Drobnjak, A.; Kalantari, Z. Flood legislation and land policy framework of EU and non-EU countries in Southern Europe. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2022, 9, e1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchi, S. A comparative review of contemporary water resources legislation: Trends, developments and an agenda for reform. In Legal Mechanisms for Water Resources in the Third Millennium; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans, M.M.; Baken, K.A.; van Der Oost, R.; Schriks, M.; van Wezel, A.P. Risk-based approach in the revised European Union drinking water legislation: Opportunities for bioanalytical tools. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2019, 15, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderaro, M.R.; Fusco, A.; Amitrano, C.C. The European Union Regulation 2020/741: From the Management of Water Resources to the EU Legislation for Its Reuse. In Water Reuse and Unconventional Water Resources: A Multidisciplinary Perspective; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Soprun, O.; Bublyk, M.; Matseliukh, Y.; Andrunyk, V.; Chyrun, L.; Dyyak, I.; Yakovlev, A.; Emmerich, M.; Osolinsky, O.; Sachenko, A. Forecasting Temperatures of a Synchronous Motor with Permanent Magnets Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings (CEUR-WS.org), MoMLeT+DS 2020 Modern Machine Learning Technologies and Data Science Workshop, Lviv-Shatsk, Ukraine, 2–3 June 2020; pp. 95–120, ISSN 1613-0073. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhovska, N.; Kaminskyy, R.; Zasoba, E.; Tsiutsiura, M. Association Rules Mining in Big Data. Int. J. Comput. 2018, 17, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G. Evolution of water legislation. In Water Resources of Italy: Protection, Use and Control; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- Truba, V.I.; Bernaziuk, O.O.; Yesimov, S.S.; Zilnyk, N.M.; Tarnavska, M.I. The Legal Mechanism for Environmental Protection in Ukraine. Sci. Bull. Natl. Min. Univ. 2023, 5, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, N.; Tian, Q.; Liu, W.; Han, F.; Jiang, S.; Lu, M.; Zheng, Y. Predicting Dynamic Riverine Nitrogen Export in Unmonitored Watersheds: Leveraging Insights of AI from Data-Rich Regions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abba, S.I.; Hadi, S.J.; Sammen, S.S.; Salih, S.Q.; Abdulkadir, R.A.; Pham, Q.B.; Yaseen, Z.M. Evolutionary computational intelligence algorithm coupled with self-tuning predictive model for water quality index determination. J. Hydrol. 2020, 587, 124974, ISSN 0022-1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, 19 September 2018 on Approval of the Procedure for State Water Monitoring. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/758-2018-%D0%BF#Text (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Ukrainian)

- Lipyanina, H.; Maksymovych, V.; Sachenko, A.; Lendyuk, T.; Fomenko, A.; Kit, I. Assessing the Investment Risk of Virtual IT Company Based on Machine Learning. In Data Stream Mining & Processing; DSMP 2020; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Babichev, S., Peleshko, D., Vynokurova, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]