In this section, the key points of the methodology proposed to study the influence of climate change on IDF curves are discussed. The chapter is subdivided into four sub-sections where the Clausius–Clapeyron correction, the GEV reconstruction from the EURO-CORDEX ensemble, the effects of climate change on hydraulic infrastructures design and the possible future developments of this study are discussed.

4.1. IDF Curves and Clausius–Clapeyron Correction

In the first part of this paper, the Clausius–Clapeyron theory has been presented. The existing relation between the temperature and rainfall rates derives from the assumption that as the temperature increases, the atmosphere increases its capability to store water vapour [

43,

44,

66]. An additional amount of vapour means more fuel for precipitation occurrence. This behaviour has been detected by several authors around the world and was also confirmed across the Alpine mountain range [

23,

42,

43,

44] (

Table 10). In this light, this study conducted across the Lombardy region (located in the Southern Alps) has shown how the intensity of precipitation may scale with the temperature, following CC (7% °C

−1) and 2CC rates (14% °C

−1), in accordance with the literature studies conducted and reported in

Table 5. Thanks to the robustness of this atmospheric property, following the work presented in [

41], a possible correction of IDF curves based on the Clausius–Clapeyron relation has been evaluated. Taking into account Equation (2), the new rainfall intensity I or height H could be easily retrieved by rescaling the currently available IDF curves and simply considering two pieces of information: the R

sc scaling coefficient (which has been demonstrated to lie between 7 and 14% °C

−1) and the possible temperature increments due to climate change. In

Table 3, a possible combination of the two parameters has been described, showing how the correction is perturbed: for small R

sc and ΔT

cc, the new rainfall intensity is very close to the previous one with variation < 10%, and while increasing the parameters (CC = 14% °C

−1) and ΔT

cc = +4 °C, the intensity increases up to 60%.

The method proposed is undoubtedly straightforward to apply to adjust currently adopted IDF curves, and it is more physically based with respect to the empirical methods that simply increase the intensity or height by a fixed percentage. However, the method described is not the most accurate one that considers the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship. According to [

23], it could be improved by also considering the dependence of rainfall duration D and RP with respect to the evaluation of the new intensity. These dependences are included in Equation (2) as corrective factors, but they need to be estimated using the data available, which may depend on the site-specific characteristics, such as rainfall types that occur at a particular location. Moreover, even though the CC relationship is robust, the ranges of R

sc ratio and temperature T are quite wide, and may experience greater spatial variability, especially across complex orography environments [

66,

84] (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Regional Climate Model (RCM) projections show that intense daily precipitation (corresponding to the 99.9th percentile of distributions) will increase at rates of between 6% and 15%, compared to past observations [

29,

30]. According to [

23], the value of R

sc could also be a direct function of the duration of the event. In fact, by increasing the duration, the average tends to decrease up to values of 5–7% °C

−1, while for heavy and extreme rains of short and very short duration, R

sc can increase up to 15% °C

−1. It can also vary with other parameters, but the relationships are still partly unknown or rather complex to extrapolate [

23].

According to IPCC [

25], the Alps have already experienced a more significant rise in temperature due to their location near the Mediterranean hot spot [

30]. Across the Alps, several types of precipitation may occur (convective and stratiform) depending on the season, which are locally perturbed by orographic uplift and moist southerly flows [

10,

83,

84], that significantly increase the dispersion of the R

sc coefficient [

66,

85,

86]. Therefore, a transition between CC and 2CC is expected for more extreme events. According to [

66,

85], the CC value is obtained for stratiform precipitation, while for convective precipitation, it is possible to reach 2CC values. When the precipitation is characterised by a mixed type or with characteristics tending to be convective, an intermediate situation may occur. It should be noted that the linear growth behaviour is, however, limited beyond a certain temperature threshold (~25 °C) [

66,

85,

86]. Beyond this value, the loss of the saturation capacity of the atmosphere (the amount of vapour required to saturate a volume of air increases as the temperature increases) acts as a limiting factor that could inhibit the mechanisms of initiation of convective precipitation (

Figure 25).

As a matter of fact, the methodology that implements the CC correction represents a wise attempt to approximately infer the influence of climate change on IDF curves, taking into account the strong climatic drivers such as the temperature increments. In our opinion, this correction is suitable for gaining an idea of the effects of the climate change process without digging into deep climatological studies. The formula is valuable for practical and expeditious studies (such ones those deputed for urban planning), bearing in mind that its parameterisation of Rsc should be carried out with care, considering site-specific rainfall characteristics. However, for a better depiction of the climate change influence of IDF curves following a more rigorous methodology based on climate models’ outputs, the extreme value analysis is preferable.

4.2. IDF Curves and Climate-Change GEV Analysis

The insights into the temperature-intensity (T-I) relationship that come from the Clausius–Clapeyron theory are implicitly embedded in the climate change models. The former aim to find projections of the atmospheric state in the future under a specific radiative scenario (RCP 8.5 in this study) that corresponds to a CO

2 concentration forcing generated by human activities [

38]. Since climate models make future projections, the errors embedded in the output data could be significant, especially moving forward in the future up to the 2100 horizon, where sometimes, divergent behaviour may be detected [

30]. In order to cope with these uncertainties, the EURO-CORDEX consortium has proposed an ensemble of climate models with the aim of studying, in a more statistical and probabilistic way, the effects of climate change [

31,

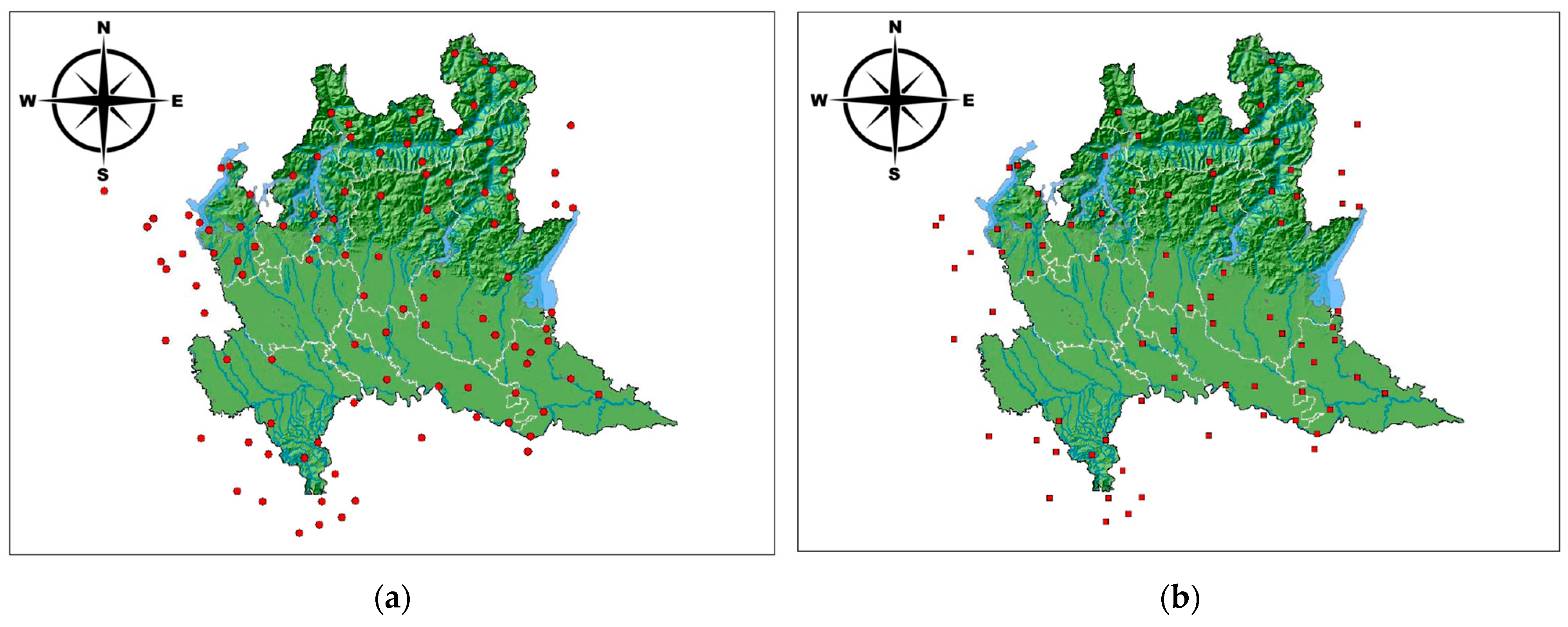

38]. In this work, the focus concentrated on precipitation variables. The 15 climate models’ rainfall series (from 1976 up to 2100) have been studied across the Lombardy region, applying the extreme value analysis (GEV) to detect possible variation in the future trend of IDF curves.

From a methodological viewpoint, rebuilding IDF curves using a climatic model has faced some issues presented here. Firstly, the reference IDF curves, currently adopted in the Lombardy area and provided by ARPA Lombardia environmental agency, are distinguished into two different samples (1–24 h short-duration and 1–5 day long-duration rainfall IDF curves). The reference IDF curves exhibit important discontinuities at D = 24 h that, even if they are not physical, can make it difficult to compare them with climatic model elaboration [

19,

49,

87]. This “methodological” difference can be appreciated by comparing the differences between the IDF curves’ statistics at 24 h and 1 day. As was presented in the results, this difference is negligible at the wettest location of the Lombardy region (i.e., the western part), while it is in the order of 40–50% in the dryest locations (i.e., the eastern part). This discrepancy should be taken into account when IFD curves are applied for hydraulic projects, because it does not have a physical meaning and is just related to the sampling method of the rain gauge data. Our analysis has pointed out a possible correlation with the 2D spatial distribution of the

a1 parameter of the curves (see

Appendix D), which is representative of the “energy” of precipitation [

19], namely looking at

Figure 4, which is the corrected IDF value at D = 24 h or D = 1 day. Probably the most precise and rigorous evaluation is the one coming from the “

moving widow” sample (i.e., the 1–24 h curves), but currently used climatic models provide output data on a daily basis, which allows the application of a “

fixed window” sampling method. For this reason, only the long-duration 1–5 days rainfall IDF curves could be, in principle, reconstructed using the EURO-CORDEX models.

Secondly, the reference IDF curves were evaluated using recorded rain gauge data on a historical period between 1951 and 2001 [

19,

49], while the reference period for the EURO-CORDEX model is generally between 1976 and 2005 [

38]. Therefore, a complete overlapping of the two series is partially missed, bearing in mind that, in both cases, the datasets were probably already affected by climate change due to the steep rising CO

2 concentration experienced during that period [

25]. IDF curves require long and continuous rain gauge time series. The latter is not always guaranteed due to instrumentation failure, poor maintenance, moving location, etc. [

10]. Therefore, the number of stations available for the effective IDF curves calculus could be significantly lower than the entire network, giving a poor representation of IDF curves statistics in those areas where stations are less dense than normally occur across mountain ranges [

19]. Conversely, even though the climate pixel is not punctual, they are uniformly distributed in a grid, covering the entire domain with a constant density. As a result, the information contained in the climate model rainfall series could sometimes be higher than the one considered to build reference IDF curves.

Thirdly, the reference IDF curves in the Lombardy region have been evaluated using the GEV methodology, but other strategies have been implemented in other parts of the Italian territory (such as TCEV, the Two-Component Extreme Value distribution [

88]), sometimes preferring large area regionalisation of the IDF curve parameters [

49,

64,

82] against the single rain-gauge statistics. So, the differences between the spatial resolution of the climatic model (expressed in terms of the cell dimension of the calculation grid domain) with respect to the spatial aggregation/regionalisation of the coefficients of the reference IDF curve analysis may represent another source of uncertainty in the method. In this regard, the spatial and temporal resolution of each climate model’s output data represents a critical aspect. In fact, implementing GEV statistics on rain gauges with respect to climate change model outputs should consider that the rainfall data are provided on a ‘single-cell’ basis at a spatial resolution in the order of ~11–12 km. This means that the precipitation is considered uniform in space within an area of ~100 km

2, which is not always a correct assumption from a physical viewpoint [

19,

32] since rainfall amounts may change abruptly across the landscape, especially across mountain ranges due to orographic effects [

4]. Thunderstorms (i.e., the phenomena that bring the highest rainfall ratios) have a circular-elliptical shape where the rainfall intensity is higher in the centre and lower at the border, so uniform precipitation could not be representative, since a smoothing of the highest rainfall rates is applied by the model [

19,

89]. The loss in spatial resolution is crucial to take into account when extreme precipitation is studied, especially for short-duration phenomena [

23]. Another difference is the temporal resolution, which for climate models is generally fixed at 1 day. Sub-hourly data are generally not investigated since, in reproducing short-rainfall statistics, they are not retained with sufficient accuracy [

23,

90]. Nonetheless, the EURO-CORDEX dataset contains data at a maximum temporal aggregation of three hours, but, due to the coarser spatial scale, short-duration rainfall events (i.e., moist convection) are not resolved explicitly [

57]. According to [

33], RCMs and GCMs have shown some issues with their sub-grid scale parameterisations of convective processes, which affect their ability to reproduce, for example, the diurnal cycle of rainfall intensity, the peak storm intensities, and extreme hourly intensities. It is therefore questionable to what extent such RCMs are capable of describing short-duration extremes in the present as well as in the future climate. Within the EURO-CORDEX ensemble, only a subset of model outputs is available on an hourly basis [

33]: the sub-daily extreme statistics are limited to a small number of models, increasing the possible uncertainties in their evaluation. In addition, temporal and spatial downscaled models may be available locally over a particular region, not completely covering the European domain [

91]. Sub-daily data could be retrieved from Convection-Permitting climate Models (CPMs) [

35,

81,

92], high-resolution regional climate models that explicitly represent deep moist convection, a crucial atmospheric process required for understanding and predicting weather extremes like intense rainfall. Unlike traditional climate models that parameterise convection, CPMs resolve it directly on their grid, leading to more accurate simulations of local-scale phenomena. CPMs are better at capturing the complexities of localised weather events, such as heavy rainfall and extreme temperatures, which are often missed or misrepresented by models with coarser resolutions. Nevertheless, they also come with significant challenges. These include high computational demands, the need for high-resolution observations, and uncertainties in representing certain physical processes, particularly at the sub-kilometre scale [

81,

93,

94]. CPMs are experimental, since the moist convection analysis is difficult to reproduce at a large scale and considering a long-term horizon (such as in the case of climate models) [

64,

82]. Moreover, the overall performance in reproducing convective precipitation with realistic and physically consistent rainfall rates is not always accurate, providing a statistical distribution of sub-daily extremes that is sometimes too smoothed and that is significantly different from real data [

30,

34,

95].

Bearing in mind all these issues, in our analysis, only the 15 EURO-CORDEX models have been considered, excluding the common reanalysis downscaling simulations and hourly basis data, in order to not introduce some additional uncertainty propagation through the IDF curve methodology. Extreme value analysis was carried out, adopting the following working hypotheses. Looking at the differences between climate and reference datasets, the analysis did not concentrate on the direct recalculation of the IDF curves. EURO-CORDEX data provide rainfall series from 1976 up to 2100, where 1976–2005 represents the reference period where the climate model is generally calibrated and initialised. Recalling that the historical period (centred in 1991) that partially overlaps with the reference IDF curves (evaluated from 1951 and 2001), the past climatology agreement of the EURO-CORDEX ensemble was verified by comparing the IDF curve parameters (

a1 and

n) computed for the historical period (1976–2005) with the reference IDF curve parameters. The error analysis has confirmed that the reference period was assessed differently by each climate model, but, on average, the BIAS% and RMSE% in the rainfall statistics are rather low, around 10–15% in the preliminary test case of Northern Lombardy, while they are around 20–30% (for

a1) and 10–20% for

n, considering the entire ensemble over the Lombardy region. These errors are not uniformly distributed across the investigated area (

Figure 15), but they were reported more frequently across the PR sector, the one that exhibits the highest precipitation amounts and the steepest orographic rainfall gradients.

After validation of the past climatic time series, IDF curve analysis was carried out considering climate change influence by applying (adding) the mean climate anomalies evaluated in the comparison between the future projection IDF curve statistics (from 2006 to 2100) against the ones reconstructed for the reference period (from 1976 to 2005) for the entire EURO-CORDEX ensemble. Moreover, the future period was subdivided into three sub-periods corresponding to the short, medium, and long term. The analysis of the anomalies has been distinguished as a function of the duration D, the return period RP, and the future horizon (short-term centred in 2021, medium-term centred in 2051, and long-term centred in 2081), and produced the following main outcomes.

The climate anomaly will increase progressively moving forward in the future by about +20–30 mm if all durations and RPs are averaged. This data can be interpreted as a long-term linear trend of +0.2–0.3 mm yr

-1 that embeds a certain grade of variability depending on the Lombardy area investigated. This trend was retrieved as more stable and less variable across the pre-alpine areas, which are the wettest areas of the region, while it is more dispersed across the Po floodplain and the internal AV sector. In the drier areas, a clear tendency is difficult to establish since extreme events are sometimes very rare and exceptional if compared to the wettest areas. However, climate change is likely to impact the climatology of the overall Lombardy region, increasing the IDF curves with positive anomalies, as was reported in [

23,

30,

40,

64,

82].

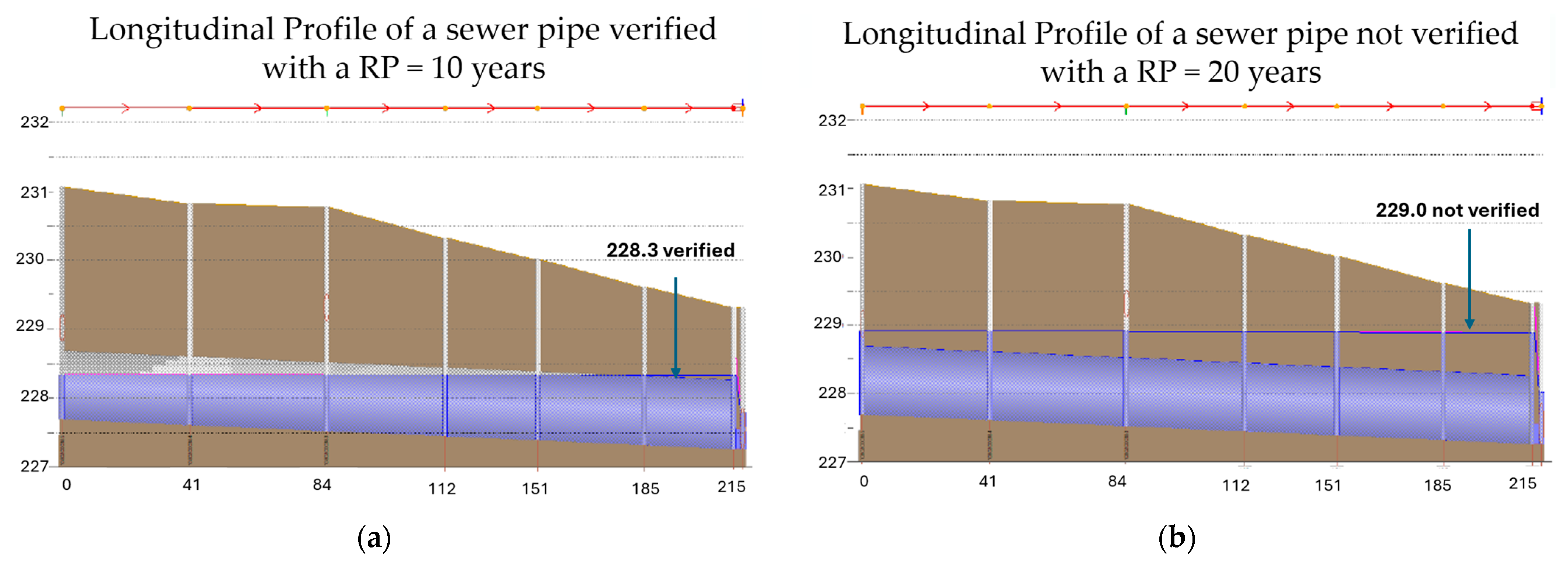

The positive anomalies calculated will cause upper shifting of an IDF curve, which translates to a reduction in rainfall RP. In this study, the RP contraction was assessed to be in the order of −40–60%, confirming several literature studies that have conducted similar elaborations across European countries [

23,

56,

67,

68]. The half-reduction in RP is significant and highlights how climate change impacts the IDF curves. Temperature increasing scales linearly with the rainfall intensity variation (following Clausius-Clapeyron relation), while the logarithm of RP tends to reduce linearly. That means that a linear increase in intensity (i.e. a positive climate anomaly) corresponds to an exponential decrease in RP. This outcome is interesting, especially for hydraulic structure projects and retrofitting that, under a climate change scenario, may be unverified due to RP shifting [

64,

82].

Another point touched on in the analysis is related to the sub-daily anomaly estimation. Since the climate model ensemble does not provide hourly data, the anomaly cannot be directly evaluated [

82]. However, having calculated the daily anomaly (1 to 5 days), a duration–anomaly function for a specified RP was retrieved. The data were interpolated using linear and power-law trend curves and then extrapolated to sub-daily data, giving a simplified estimation of the possible anomalies. Among the two curves, the linear approximation appears more ‘crude’ with respect to the power-law, admitting more anomalies (double) for short-duration events. This technique has been proposed in order to cope with the climate data limitations, and, in our opinion, it represents a straightforward way to at least take into account the climate change influence for sub-daily IDF curves. In this regard, sub-daily data future projections are crucial, since they are frequently applied in the design of sewage networks, which are characterised by a correlation time in the order of a few hours [

14]. However, the main drawback of this extrapolation method consists of the fact that IDF curves for sub-daily duration are steeper, since the representative phenomena, rainfall phenomena (i.e., thunderstorms), have slightly different characteristics with respect to the longer ones (i.e., stratiform precipitation). This transition is continuous in nature and cannot be clustered with a threshold on rainfall duration [

1,

2]. Therefore, this anomaly trend should be treated and interpreted carefully.

4.3. Adaptation to Climate Change in Hydraulic Infrastructures

Applying the extreme value statistics to the climate model ensemble has allowed us to quantify the uncertainties behind the IDF curve reconstruction. All the evaluations presented in this work have been provided in terms of mean, median, and standard deviation in order to highlight their derivation from the EURO-CORDEX ensemble (

Figure 26). According to [

24,

25,

86], an increase in mean temperature is likely to occur in the future, while for precipitation, even if the mean will remain the same, an increase in variance (i.e., more extreme rainfall events) is expected. Our study has addressed this statement across the Lombardy region under the RCP 8.5 scenario, showing the negligible variation in mean precipitation compensated for by an increase in extremes by the end of the current century. These results have been validated statistically through the

t-test and Welch test, studying the mean anomalies in the future calculated from the entire EURO-CORDEX ensemble. Moreover, applying the Pearson test to P

max-y from 2006 to 2100 projections, a statistically significant tendency was detected in the datasets. So, increases in precipitation variance (and in mean rainfall intensities) seem to be the most probable effect of climate change in the future [

29,

30,

34,

95].

The climate model yearly maximum rainfall series increase their dispersion with the return period RP, with the duration D, and when moving forward into the future with rather variable but clear positive trends. Therefore, ongoing climate change will significantly impact the IDF curve’s statistics with direct consequences on the management of hydraulic infrastructures and the sewage network [

23,

25,

40]. Therefore, the frequency of intense precipitation outside the design RP range (i.e., higher) may increase in the future, raising infrastructure issues and maintenance/replacement costs. In this work, two experiences of a stormwater detention tank and a sewage pipe have been reported in order to practically see the effects of IDF curves variation induced by climate change. As was described, the two infrastructures need to be redesigned, increasing their dimensions (i.e., the storage volume for the stormwater detention tank and the size of the pipe) in order to be able to contain or transport a large amount of water coming from the sewage network. Recently, these climate change side effects have started to be included within the guidelines of local regulation [

96,

97], where the urgency of considering climate change adaptation is highlighted [

98,

99]. In this regard, recalling the validity of the GEV procedure is essential for future projections of higher RPs. Generally speaking, to carry out an accurate GEV for high RPs, longer time series are required. However, in climatology, 30 years is taken as a reference period for establishing the climate variation, and this sample length may limit the extrapolation of GEV statistics for higher RPs, degrading their accuracy. Nevertheless, these statistics, even though they are sometimes approximated, are a crucial indication for future climate assessment of the infrastructure [

100]. In fact, RPs ≤ 100 years are applied in the larger part of civil hydraulic infrastructure (bridges, sewage networks, etc.); RPs > 100 years are taken into account for flood risk analysis (European and Italian regulations considered a RP of 200 years for floods), while RPs equal to 500 or 1000 years are adopted for large dam projects [

14].

According to [

23,

24,

25,

101], climate change effects should be taken into account not only for new projects (which is easier), but adaptation and mitigation measures should be applied to the existing sewage network in order to prevent potentially severe damages. The RP exponential reduction against rising temperature should be considered, because a critical rainfall with RP = 100 years will become more likely with RP = 50 years, reducing its value by half and doubling its frequency. Among the infrastructure analysed, the sewage pipe is the most sensitive, since it is located underground and retrofitting is sometimes difficult because it implies a complete diameter resizing of the pipe, excavation, etc. Another possibility could be to double the number of pipes to improve the rainfall drainage locally, taking into account the enlarged volumes predicted by modified IDF curves. All of these interventions will not be costless, so it is advisable to evaluate a cost–benefit analysis, highlighting the most critical situations within the analysed network [

102]. Moreover, since the IDF curves exhibit a smoother but not negligible variability across the territory, the anomaly correction should be performed taking into account the site-specific statistics, or at least considering aggregated sectors, as was presented in this study.

4.4. Future Developments

The IDF curve reconstruction methodology presented in this work follows an articulated framework that mainly depends on both the quality of the climatic model data output and on the integrity of the reference IDF curve dataset [

31]. Future developments will be mainly related to the improvement in climate change reconstruction to allow us to study short-duration rainfall events at a refined spatial scale. As mentioned throughout the text, the new CPMs (Convective Permitting Models) will help in this way, but up to now, only a few examples of these models have been validated and are not yet included within a climate ensemble [

23,

69,

89] like EURO-CORDEX. On the other hand, a future homogeneization of the reference IDF curves would be expected, slightly enlarging the historical data series (comprising at least the last 20–25 years of data) and hopefully resolving (and closing) the gap between the 1–24 h and 1–5 days statistics. This gap might perturb the infrastructure design, especially across drier areas of the Lombardy region, where the errors detected are larger (

Figure 4). According to hydraulic engineers working in this sector, a possible suggestion for solving this issue is to consider, among the durations of 1 day or 24 h, the worst-case scenario (i.e., the highest intensity, for a selected RP).

Nowadays, automated rain gauge stations are able to work with higher temporal resolution up to 10–5 min, so they could potentially resolve the issues encountered throughout the text regarding the IDF extrapolation for sub-daily and sub-hourly durations [

14]. In this regard, we retain that the accuracy of the GEV methodology is lower than for daily statistics, so that the Clausius–Clapeyron correction could be adopted in combination and privileging the most conservative approach among the two (i.e., the one who admits highest rainfall intensity I or height H for a certain RP and D).

However, the results obtained in the analysis are in accordance with other studies that have applied the extreme value methodology to climate datasets [

23,

56,

67,

68], so that future analysis will improve the robustness of the presented framework, taking into account possible data preprocessing (such as a tailor-made statistical downscaling of the rainfall data both in space and time) with further investigation across the three climatic areas evaluated for the Lombardy region. In principle, the methodology presented is rather general and could be applied across other areas of the Alps to see if the climatic trends of IDF curves hold similarly or may change in the future. Another extension of the methodology could be the analysis of other RCP scenarios, considering not only the 8.5 (the most critical) but also at least the RCP 4.5, according to [

34]. Currently, IPCC [

25] has revised the climate scenarios in the sixth report, which have been distinguished taking into account other parameters and, therefore, they are slightly different from the scenarios adopted in this study, which refers to the timeline of the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) of the IPCC. Unfortunately, EURO-CORDEX ensembles are not yet available for addressing regional climate investigation using the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), but they will surely open new perspectives for more accurate extreme rainfall analysis.