Roles of mTOR Signaling in Tissue Regeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

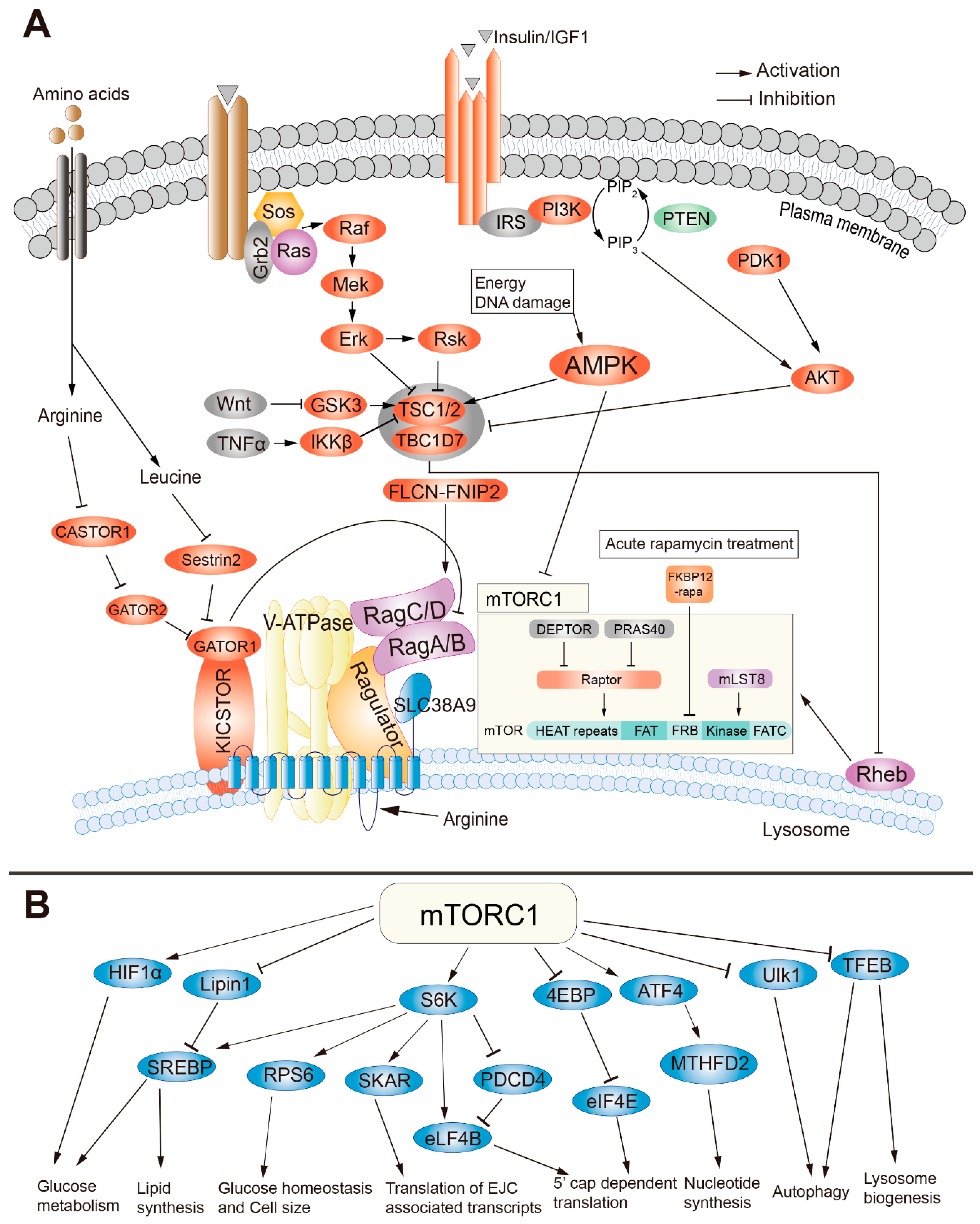

2. The Structure and Regulation of mTORC1

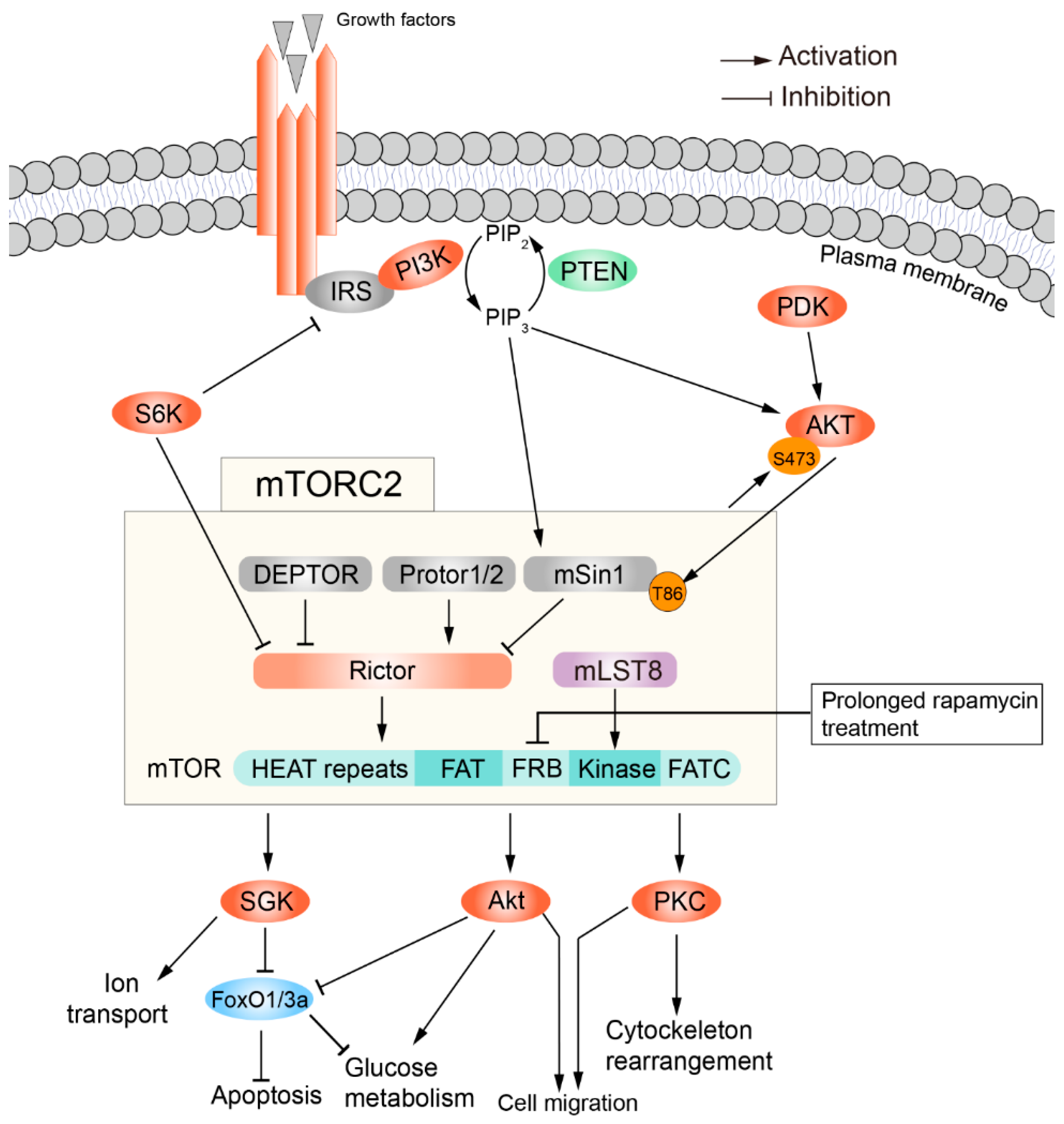

3. The Structure and Regulation of mTORC2

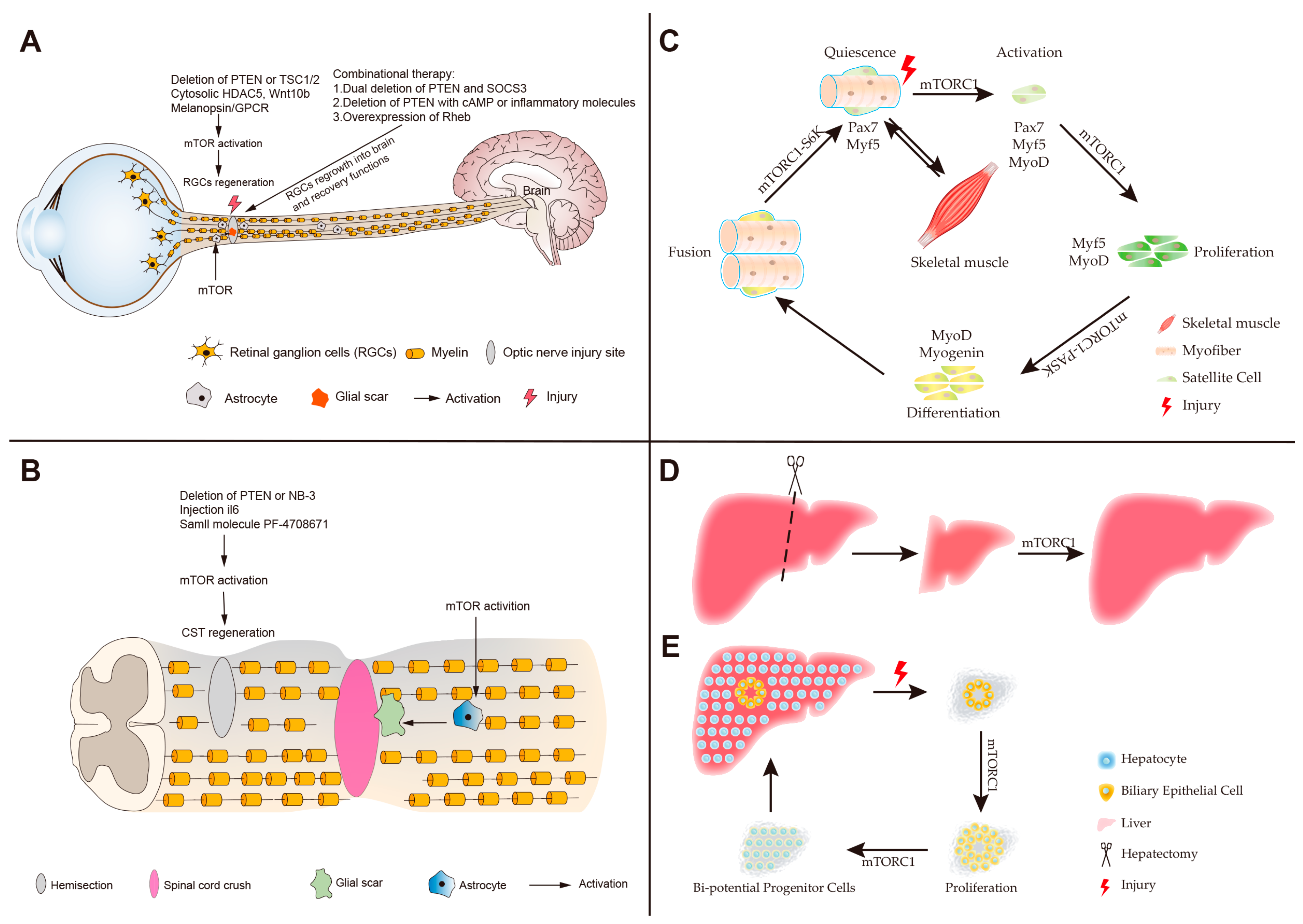

4. Roles of mTOR in Neuronal Regeneration

5. Roles of mTOR in Skeletal Muscle Regeneration

6. Roles of mTOR in Liver Regeneration

7. Roles of mTOR in Intestinal Regeneration

8. Perspectives

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.C.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Kaeberlein, M. mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature 2013, 493, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Kuo, C.J.; Crabtree, G.R.; Blenis, J. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth-dependent activation of and signaling by the 70 kd S6 protein kinases. Cell 1992, 69, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.J.; Albers, M.W.; Shin, T.B.; Keith, C.T.; Lane, W.S.; Schreiber, S.L. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature 1994, 369, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, W.J.; Jacinto, E. mTOR complex 2 signaling and functions. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2305–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Guan, K.L. mTOR as a central hub of nutrient signalling and cell growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Gan, W.; Chin, Y.R.; Ogura, K.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Blenis, J.; Cantley, L.C.; Toker, A.; et al. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-Dependent Activation of the mTORC2 Kinase Complex. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1194–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simioni, C.; Martelli, A.M.; Zauli, G.; Melloni, E.; Neri, L.M. Targeting mTOR in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cells 2019, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, N. Physical Activity Alleviates Cognitive Dysfunction of Alzheimer’s Disease through Regulating the mTOR Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.C.; Cook, R.S.; Chen, J. mTORC1 and mTORC2 in cancer and the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene 2017, 36, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, P.; Kandror, K.V. The role of mTOR in lipid homeostasis and diabetes progression. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2015, 22, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perl, A. mTOR activation is a biomarker and a central pathway to autoimmune disorders, cancer, obesity, and aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1346, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, A.M.; Buontempo, F.; McCubrey, J.A. Drug discovery targeting the mTOR pathway. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2018, 132, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, I.M.; Halder, G. Hippo-YAP/TAZ signalling in organ regeneration and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddour, J.A.; Sousounis, K.; Tsonis, P.A. Organ repair and regeneration: An overview. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 2012, 96, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.K.; Liu, K.; Hu, Y.; Smith, P.D.; Wang, C.; Cai, B.; Xu, B.; Connolly, L.; Kramvis, I.; Sahin, M.; et al. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the PTEN/mTOR pathway. Science 2008, 322, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimobayashi, M.; Hall, M.N. Making new contacts: The mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciarretta, S.; Forte, M.; Frati, G.; Sadoshima, J. New Insights Into the Role of mTOR Signaling in the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Guan, K.L. Expanding mTOR signaling. Cell Res. 2007, 17, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; King, J.E.; Latek, R.R.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell 2002, 110, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; Latek, R.R.; Guntur, K.V.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Sabatini, D.M. GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Maruki, Y.; Long, X.; Yoshino, K.; Oshiro, N.; Hidayat, S.; Tokunaga, C.; Avruch, J.; Yonezawa, K. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell 2002, 110, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancak, Y.; Thoreen, C.C.; Peterson, T.R.; Lindquist, R.A.; Kang, S.A.; Spooner, E.; Carr, S.A.; Sabatini, D.M. PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase. Mol. Cell 2007, 25, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Haar, E.; Lee, S.I.; Bandhakavi, S.; Griffin, T.J.; Kim, D.H. Insulin signalling to mTOR mediated by the Akt/PKB substrate PRAS40. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, T.R.; Laplante, M.; Thoreen, C.C.; Sancak, Y.; Kang, S.A.; Kuehl, W.M.; Gray, N.S.; Sabatini, D.M. DEPTOR is an mTOR inhibitor frequently overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells and required for their survival. Cell 2009, 137, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Rudge, D.G.; Koos, J.D.; Vaidialingam, B.; Yang, H.J.; Pavletich, N.P. mTOR kinase structure, mechanism and regulation. Nature 2013, 497, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, D.M. Twenty-five years of mTOR: Uncovering the link from nutrients to growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11818–11825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibble, C.C.; Elis, W.; Menon, S.; Qin, W.; Klekota, J.; Asara, J.M.; Finan, P.M.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Murphy, L.O.; Manning, B.D. TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Dibble, C.C.; Talbott, G.; Hoxhaj, G.; Valvezan, A.J.; Takahashi, H.; Cantley, L.C.; Manning, B.D. Spatial control of the TSC complex integrates insulin and nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome. Cell 2014, 156, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, Z.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Pandolfi, P.P. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell 2005, 121, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Ma, D.; Liu, A.; Shen, X.; Wang, Q.J.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y. Rheb activates mTOR by antagonizing its endogenous inhibitor, FKBP38. Science 2007, 318, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Jiang, X.; Li, B.; Yang, H.J.; Miller, M.; Yang, A.; Dhar, A.; Pavletich, N.P. Mechanisms of mTORC1 activation by RHEB and inhibition by PRAS40. Nature 2017, 552, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Palm, W.; Peng, M.; King, B.; Lindsten, T.; Li, M.O.; Koumenis, C.; Thompson, C.B. GCN2 sustains mTORC1 suppression upon amino acid deprivation by inducing Sestrin2. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 2331–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantranupong, L.; Scaria, S.M.; Saxton, R.A.; Gygi, M.P.; Shen, K.; Wyant, G.A.; Wang, T.; Harper, J.W.; Gygi, S.P.; Sabatini, D.M. The CASTOR Proteins Are Arginine Sensors for the mTORC1 Pathway. Cell 2016, 165, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebsamen, M.; Pochini, L.; Stasyk, T.; de Araujo, M.E.; Galluccio, M.; Kandasamy, R.K.; Snijder, B.; Fauster, A.; Rudashevskaya, E.L.; Bruckner, M.; et al. SLC38A9 is a component of the lysosomal amino acid sensing machinery that controls mTORC1. Nature 2015, 519, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goberdhan, D.C.; Wilson, C.; Harris, A.L. Amino Acid Sensing by mTORC1: Intracellular Transporters Mark the Spot. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, J.L.; Russell, R.C.; Guan, K.L. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, J.L.; Kim, Y.C.; Russell, R.C.; Yu, F.X.; Park, H.W.; Plouffe, S.W.; Tagliabracci, V.S.; Guan, K.L. Metabolism. Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science 2015, 347, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsun, Z.Y.; Bar-Peled, L.; Chantranupong, L.; Zoncu, R.; Wang, T.; Kim, C.; Spooner, E.; Sabatini, D.M. The folliculin tumor suppressor is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Mol. Cell 2013, 52, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Hu, W.; de Stanchina, E.; Teresky, A.K.; Jin, S.; Lowe, S.; Levine, A.J. The regulation of AMPK beta1, TSC2, and PTEN expression by p53: Stress, cell and tissue specificity, and the role of these gene products in modulating the IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 3043–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinn, D.M.; Shackelford, D.B.; Egan, D.F.; Mihaylova, M.M.; Mery, A.; Vasquez, D.S.; Turk, B.E.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoki, K.; Zhu, T.; Guan, K.-L. TSC2 Mediates Cellular Energy Response to Control Cell Growth and Survival. Cell 2003, 115, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoki, K.; Ouyang, H.; Zhu, T.; Lindvall, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Bennett, C.; Harada, Y.; Stankunas, K.; et al. TSC2 integrates Wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by AMPK and GSK3 to regulate cell growth. Cell 2006, 126, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.F.; Kuo, H.P.; Chen, C.T.; Hsu, J.M.; Chou, C.K.; Wei, Y.; Sun, H.L.; Li, L.Y.; Ping, B.; Huang, W.C.; et al. IKK beta suppression of TSC1 links inflammation and tumor angiogenesis via the mTOR pathway. Cell 2007, 130, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nojima, H.; Tokunaga, C.; Eguchi, S.; Oshiro, N.; Hidayat, S.; Yoshino, K.; Hara, K.; Tanaka, N.; Avruch, J.; Yonezawa, K. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) partner, raptor, binds the mTOR substrates p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 through their TOR signaling (TOS) motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 15461–15464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holz, M.K.; Ballif, B.A.; Gygi, S.P.; Blenis, J. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell 2005, 123, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrello, N.V.; Peschiaroli, A.; Guardavaccaro, D.; Colburn, N.H.; Sherman, N.E.; Pagano, M. S6K1- and betaTRCP-mediated degradation of PDCD4 promotes protein translation and cell growth. Science 2006, 314, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruvinsky, I.; Meyuhas, O. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: From protein synthesis to cell size. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.M.; Yoon, S.O.; Richardson, C.J.; Julich, K.; Blenis, J. SKAR links pre-mRNA splicing to mTOR/S6K1-mediated enhanced translation efficiency of spliced mRNAs. Cell 2008, 133, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingras, A.C.; Gygi, S.P.; Raught, B.; Polakiewicz, R.D.; Abraham, R.T.; Hoekstra, M.F.; Aebersold, R.; Sonenberg, N. Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: A novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 1422–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.R.; Sengupta, S.S.; Harris, T.E.; Carmack, A.E.; Kang, S.A.; Balderas, E.; Guertin, D.A.; Madden, K.L.; Carpenter, A.E.; Finck, B.N.; et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell 2011, 146, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Sahra, I.; Hoxhaj, G.; Ricoult, S.J.H.; Asara, J.M.; Manning, B.D. mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science 2016, 351, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvel, K.; Yecies, J.L.; Menon, S.; Raman, P.; Lipovsky, A.I.; Souza, A.L.; Triantafellow, E.; Ma, Q.; Gorski, R.; Cleaver, S.; et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kundu, M.; Viollet, B.; Guan, K.L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martina, J.A.; Chen, Y.; Gucek, M.; Puertollano, R. MTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB. Autophagy 2012, 8, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarbassov, D.D.; Ali, S.M.; Kim, D.H.; Guertin, D.A.; Latek, R.R.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Sabatini, D.M. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, M.A.; Thoreen, C.C.; Jaffe, J.D.; Schroder, W.; Sculley, T.; Carr, S.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1865–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Jun, C.B.; Kim, Y.M.; Haar, E.V.; Lee, S.I.; Hegg, J.W.; Bandhakavi, S.; Griffin, T.J.; Kim, D.H. PRR5, a novel component of mTOR complex 2, regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta expression and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25604–25612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, D.W.; Ye, L.; Katajisto, P.; Goncalves, M.D.; Saitoh, M.; Stevens, D.M.; Davis, J.G.; Salmon, A.B.; Richardson, A.; Ahima, R.S.; et al. Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science 2012, 335, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Murashige, D.S.; Humphrey, S.J.; James, D.E. A Positive Feedback Loop between Akt and mTORC2 via SIN1 Phosphorylation. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, O.J.; Wang, Z.; Hunter, T. Inappropriate activation of the TSC/Rheb/mTOR/S6K cassette induces IRS1/2 depletion, insulin resistance, and cell survival deficiencies. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1650–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Sommer, E.; Kozasa, T.; Srinivasula, S.; Alessi, D.; Offermanns, S.; Simon, M.I.; Wu, D. PRR5L degradation promotes mTORC2-mediated PKC-delta phosphorylation and cell migration downstream of Galpha12. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Gao, T. mTORC2 phosphorylates protein kinase Cζ to regulate its stability and activity. EMBO Rep. 2013, 15, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomanetz, V.; Angliker, N.; Cloetta, D.; Lustenberger, R.M.; Schweighauser, M.; Oliveri, F.; Suzuki, N.; Ruegg, M.A. Ablation of the mTORC2 component rictor in brain or Purkinje cells affects size and neuron morphology. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 201, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guertin, D.A.; Stevens, D.M.; Thoreen, C.C.; Burds, A.A.; Kalaany, N.Y.; Moffat, J.; Brown, M.; Fitzgerald, K.J.; Sabatini, D.M. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1. Dev. Cell 2006, 11, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacinto, E.; Facchinetti, V.; Liu, D.; Soto, N.; Wei, S.; Jung, S.Y.; Huang, Q.; Qin, J.; Su, B. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell 2006, 127, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Martinez, J.M.; Alessi, D.R. mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1). Biochem. J. 2008, 416, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.K.; Kwon, B.; Lemere, C.A.; de la Monte, S.; Itamura, K.; Ha, A.Y.; Querfurth, H.W. mTORC2 (Rictor) in Alzheimer’s Disease and Reversal of Amyloid-beta Expression-Induced Insulin Resistance and Toxicity in Rat Primary Cortical Neurons. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 56, 1015–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langen, U.H.; Ayloo, S.; Gu, C. Development and Cell Biology of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J.; Ronnback, L.; Hansson, E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wu, C.; Yang, Q.; Gao, J.; Li, L.; Yang, D.; Luo, L. Macrophages Mediate the Repair of Brain Vascular Rupture through Direct Physical Adhesion and Mechanical Traction. Immunity 2016, 44, 1162–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; He, J.; Ni, R.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, L. Cerebrovascular Injuries Induce Lymphatic Invasion into Brain Parenchyma to Guide Vascular Regeneration in Zebrafish. Dev. Cell 2019, 49, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.M.M.; Meyer, K.A.; Santpere, G.; Gulden, F.O.; Sestan, N. Evolution of the Human Nervous System Function, Structure, and Development. Cell 2017, 170, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richner, M.; Ulrichsen, M.; Elmegaard, S.L.; Dieu, R.; Pallesen, L.T.; Vaegter, C.B. Peripheral nerve injury modulates neurotrophin signaling in the peripheral and central nervous system. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 50, 945–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, P.N. A conditioning lesion induces changes in gene expression and axonal transport that enhance regeneration by increasing the intrinsic growth state of axons. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 223, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Jin, Y. Intrinsic Control of Axon Regeneration. Neuron 2016, 90, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omura, T.; Omura, K.; Tedeschi, A.; Riva, P.; Painter, M.W.; Rojas, L.; Martin, J.; Lisi, V.; Huebner, E.A.; Latremoliere, A.; et al. Robust Axonal Regeneration Occurs in the Injured CAST/Ei Mouse CNS. Neuron 2015, 86, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benowitz, L.I.; Yin, Y. Combinatorial treatments for promoting axon regeneration in the CNS: Strategies for overcoming inhibitory signals and activating neurons’ intrinsic growth state. Dev. Neurobiol. 2007, 67, 1148–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filbin, M.T. Myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the adult mammalian CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitch, M.T.; Silver, J. CNS injury, glial scars, and inflammation: Inhibitory extracellular matrices and regeneration failure. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 209, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Gauthier, S.; Corbett, A.; Brayne, C.; Aarsland, D.; Jones, E. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2011, 377, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, F.O. Huntington’s disease. Lancet 2007, 369, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gotz, J. Tau-based therapies in neurodegeneration: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 863–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, S.A. Stem and Progenitor Cell-Based Therapy of the Central Nervous System: Hopes, Hype, and Wishful Thinking. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.; Yang, L.; Huang, H.; Liang, F.; Ling, C.; Hu, Y. mTORC1 is necessary but mTORC2 and GSK3beta are inhibitory for AKT3-induced axon regeneration in the central nervous system. Elife 2016, 5, e14908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoya, K.; Tsukada, S.; Lu, P.; Coppola, G.; Geschwind, D.; Filbin, M.T.; Blesch, A.; Tuszynski, M.H. Combined intrinsic and extrinsic neuronal mechanisms facilitate bridging axonal regeneration one year after spinal cord injury. Neuron 2009, 64, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.; Schwab, M.E.; Popovich, P.G. Central nervous system regenerative failure: Role of oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and microglia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 7, a020602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiu, G.; He, Z. Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.; Miller, J.H. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; He, Z. Neuronal intrinsic barriers for axon regeneration in the adult CNS. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.K.; Hu, Y.; Muhling, J.; Pollett, M.A.; Dallimore, E.J.; Turnley, A.M.; Cui, Q.; Harvey, A.R. Cytokine-induced SOCS expression is inhibited by cAMP analogue: Impact on regeneration in injured retina. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2009, 41, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Zou, H. BMP signaling in axon regeneration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014, 27, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Hisamoto, N.; Nix, P.; Kanao, S.; Mizuno, T.; Bastiani, M.; Matsumoto, K. The growth factor SVH-1 regulates axon regeneration in C. elegans via the JNK MAPK cascade. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.; Liu, Y.; Sun, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; He, Z. Restoration of skilled locomotion by sprouting corticospinal axons induced by co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Ori-McKenney, K.M.; Zheng, Y.; Han, C.; Jan, L.Y.; Jan, Y.N. Regeneration of Drosophila sensory neuron axons and dendrites is regulated by the Akt pathway involving Pten and microRNA bantam. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 1612–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, A.B.; Walradt, T.; Gardner, K.E.; Hubbert, A.; Reinke, V.; Hammarlund, M. Insulin/IGF1 signaling inhibits age-dependent axon regeneration. Neuron 2014, 81, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wong, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the melanopsin/GPCR signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun-Julien, F.; Suter, U. Combined HDAC1 and HDAC2 Depletion Promotes Retinal Ganglion Cell Survival After Injury Through Reduction of p53 Target Gene Expression. ASN Neuro 2015, 7, 1759091415593066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, H.M.; Schlamp, C.L.; Nickells, R.W. Targeting HDAC3 Activity with RGFP966 Protects Against Retinal Ganglion Cell Nuclear Atrophy and Apoptosis After Optic Nerve Injury. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 34, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Cavalli, V. HDAC5 is a novel injury-regulated tubulin deacetylase controlling axon regeneration. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3063–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Sloutsky, R.; Naegle, K.M.; Cavalli, V. Injury-induced HDAC5 nuclear export is essential for axon regeneration. Cell 2013, 155, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita-Thomas, W.; Mahar, M.; Joshi, A.; Gan, D.; Cavalli, V. HDAC5 promotes optic nerve regeneration by activating the mTOR pathway. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 317, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassew, N.G.; Charish, J.; Shabanzadeh, A.P.; Luga, V.; Harada, H.; Farhani, N.; D’Onofrio, P.; Choi, B.; Ellabban, A.; Nickerson, P.E.B.; et al. Exosomes Mediate Mobilization of Autocrine Wnt10b to Promote Axonal Regeneration in the Injured CNS. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibinger, M.; Andreadaki, A.; Fischer, D. Role of mTOR in neuroprotection and axon regeneration after inflammatory stimulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 46, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-H.A.; Stafford, B.K.; Nguyen, P.L.; Lien, B.V.; Wang, C.; Zukor, K.; He, Z.; Huberman, A.D. Neural activity promotes long-distance, target-specific regeneration of adult retinal axons. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Park, K.K.; Belin, S.; Wang, D.; Lu, T.; Chen, G.; Zhang, K.; Yeung, C.; Feng, G.; Yankner, B.A.; et al. Sustained axon regeneration induced by co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nature 2011, 480, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, S.; Koriyama, Y.; Kurimoto, T.; Oliveira, J.T.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Gilbert, H.Y.; Fagiolini, M.; Martinez, A.M.; Benowitz, L. Full-length axon regeneration in the adult mouse optic nerve and partial recovery of simple visual behaviors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9149–9154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernet, V.; Schwab, M.E. Lost in the jungle: New hurdles for optic nerve axon regeneration. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, C.; Zhang, X. Rapamycin mediates mTOR signaling in reactive astrocytes and reduces retinal ganglion cell loss. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 176, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, C.S.; Wilson, J.R.; Nori, S.; Kotter, M.R.N.; Druschel, C.; Curt, A.; Fehlings, M.G. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codeluppi, S.; Svensson, C.I.; Hefferan, M.P.; Valencia, F.; Silldorff, M.D.; Oshiro, M.; Marsala, M.; Pasquale, E.B. The Rheb-mTOR pathway is upregulated in reactive astrocytes of the injured spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, H.; Ozawa, H.; Sekiguchi, A.; Yamaya, S.; Tateda, S.; Yahata, K.; Itoi, E. The role of mTOR signaling pathway in spinal cord injury. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 3175–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Sung, C.-S.; Huang, S.-Y.; Feng, C.-W.; Hung, H.-C.; Yang, S.-N.; Chen, N.-F.; Tai, M.-H.; Wen, Z.-H.; Chen, W.-F. The role of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in glial scar formation following spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 278, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhou, L. MiR-17 targets PTEN and facilitates glial scar formation after spinal cord injuries via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Brain Res. Bull. 2017, 128, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Lu, Y.; Lee, J.K.; Samara, R.; Willenberg, R.; Sears-Kraxberger, I.; Tedeschi, A.; Park, K.K.; Jin, D.; Cai, B.; et al. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, H.; Ding, Y.; Slepak, T.; Wu, W.; Sun, Y.; Martinez, Y.; Xu, X.M.; Lemmon, V.P.; Bixby, J.L. The mTOR Substrate S6 Kinase 1 (S6K1) Is a Negative Regulator of Axon Regeneration and a Potential Drug Target for Central Nervous System Injury. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 7079–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, K. Pten Deletion Promotes Regrowth of Corticospinal Tract Axons 1 Year after Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 9754–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wen, H.; Ou, S.; Cui, J.; Fan, D. IL-6 promotes regeneration and functional recovery after cortical spinal tract injury by reactivating intrinsic growth program of neurons and enhancing synapse formation. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 236, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yin, Y.; Shimoda, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Liu, Y. NB-3 signaling mediates the cross-talk between post-traumatic spinal axons and scar-forming cells. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 1745–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.K.; Liu, K.; Hu, Y.; Kanter, J.L.; He, Z. PTEN/mTOR and axon regeneration. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 223, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, N.; Borson, S.H.; Gambello, M.J.; Wang, F.; Cavalli, V. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation increases axonal growth capacity of injured peripheral nerves. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 28034–28043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lu, N.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chan, L.T.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Jiang, S.; Liu, K. Rapamycin-Resistant mTOR Activity Is Required for Sensory Axon Regeneration Induced by a Conditioning Lesion. eNeuro 2016, 3, ENEURO.0358-16.2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, S.E.; Charalambous, C.; Smith, C.A.; Tsimbouri, P.M.; Dejardin, T.; Kingham, P.J.; Hart, A.M.; Riehle, M.O. Microtopographical cues promote peripheral nerve regeneration via transient mTORC2 activation. Acta Biomater. 2017, 60, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kelamangalath, L.; Kim, H.; Han, S.B.; Tang, X.; Zhai, J.; Hong, J.W.; Lin, S.; Son, Y.J.; Smith, G.M. NT-3 promotes proprioceptive axon regeneration when combined with activation of the mTor intrinsic growth pathway but not with reduction of myelin extrinsic inhibitors. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 283, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.B.; Tajbakhsh, S. Regulation and phylogeny of skeletal muscle regeneration. Dev. Biol. 2018, 433, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawke, T.J.; Garry, D.J. Myogenic satellite cells: Physiology to molecular biology. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 91, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1961, 9, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.M. The Role of AMPK in the Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Size, Hypertrophy, and Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, S.; Rudnicki, M.A. The emerging biology of satellite cells and their therapeutic potential. Trends Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charge, S.B.; Rudnicki, M.A. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liang, X.; Shan, T.; Jiang, Q.; Deng, C.; Zheng, R.; Kuang, S. mTOR is necessary for proper satellite cell activity and skeletal muscle regeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 463, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Wu, A.L.; Warnes, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Kawasome, H.; Terada, N.; Boppart, M.D.; Schoenherr, C.J.; Chen, J. mTOR regulates skeletal muscle regeneration in vivo through kinase-dependent and kinase-independent mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 297, C1434–C1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepper, C.; Conway, S.J.; Fan, C.M. Adult satellite cells and embryonic muscle progenitors have distinct genetic requirements. Nature 2009, 460, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rion, N.; Castets, P.; Lin, S.; Enderle, L.; Reinhard, J.R.; Eickhorst, C.; Ruegg, M.A. mTOR controls embryonic and adult myogenesis via mTORC1. Development 2019, 146, dev172460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jash, S.; Dhar, G.; Ghosh, U.; Adhya, S. Role of the mTORC1 complex in satellite cell activation by RNA-induced mitochondrial restoration: Dual control of cyclin D1 through microRNAs. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 34, 3594–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikani, C.K.; Wu, X.; Fogarty, S.; Kang, S.A.W.; Dephoure, N.; Gygi, S.P.; Sabatini, D.M.; Rutter, J. Activation of PASK by mTORC1 is required for the onset of the terminal differentiation program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10382–10391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; De Simone, M.; Colussi, C.; Zaccagnini, G.; Fasanaro, P.; Pescatori, M.; Cardani, R.; Perbellini, R.; Isaia, E.; Sale, P.; et al. Common micro-RNA signature in skeletal muscle damage and regeneration induced by Duchenne muscular dystrophy and acute ischemia. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 3335–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, K.; Hagiwara, Y.; Ando, M.; Nakamura, A.; Takeda, S.I.; Hijikata, T. MicroRNA-206 is highly expressed in newly formed muscle fibers implications regarding potential for muscle regeneration and maturation in muscular dystrophy.pdf. Cell Struct. Funct. 2008, 33, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ge, Y.; Drnevich, J.; Zhao, Y.; Band, M.; Chen, J. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates miRNA-1 and follistatin in skeletal myogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. IGF-II is regulated by microRNA-125b in skeletal myogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 192, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Pasut, A.; Matsumoto, M.; Yamashita, R.; Fung, J.; Monteleone, E.; Saghatelian, A.; Nakayama, K.I.; Clohessy, J.G.; Pandolfi, P.P. mTORC1 and muscle regeneration are regulated by the LINC00961-encoded SPAR polypeptide. Nature 2017, 541, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.M.; Calejman, C.M.; Sanchez-Gurmaches, J.; Li, H.; Clish, C.B.; Hettmer, S.; Wagers, A.J.; Guertin, D.A. Rictor/mTORC2 loss in the Myf5 lineage reprograms brown fat metabolism and protects mice against obesity and metabolic disease. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadtler, K.; Estrellas, K.; Allen, B.W.; Wolf, M.T.; Fan, H.; Tam, A.J.; Patel, C.H.; Luber, B.S.; Wang, H.; Wagner, K.R.; et al. Developing a pro-regenerative biomaterial scaffold microenvironment requires T helper 2 cells. Science 2016, 352, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanou, N.; Schakman, O.; Louis, P.; Ruegg, U.T.; Dietrich, A.; Birnbaumer, L.; Gailly, P. Trpc1 ion channel modulates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway during myoblast differentiation and muscle regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 14524–14534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Fu, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Li, F. Protective Effects of Sonic Hedgehog Against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Mouse Skeletal Muscle via AKT/mTOR/p70S6K Signaling. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 43, 1813–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, A.P.; Hughes, D.C.; Deane, C.S.; Saini, A.; Selman, C.; Stewart, C.E. Longevity and skeletal muscle mass: The role of IGF signalling, the sirtuins, dietary restriction and protein intake. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, E.; Park, I.H.; Nuzzi, P.D.; Schoenherr, C.J.; Chen, J. IGF-II transcription in skeletal myogenesis is controlled by mTOR and nutrients. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 163, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, Y.S.; Lesmana, R.; Goenawan, H.; Sylviana, N.; Setiawan, I.; Tarawan, V.M.; Lestari, K.; Abdulah, R.; Dwipa, L.; Purba, A.; et al. Nutmeg Extract Increases Skeletal Muscle Mass in Aging Rats Partly via IGF1-AKT-mTOR Pathway and Inhibition of Autophagy. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. eCAM 2018, 2018, 2810840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, W.R.; Hughes, V.A.; Fielding, R.A.; Fiatarone, M.A.; Evans, W.J.; Roubenoff, R. Aging of skeletal muscle: A 12-yr longitudinal study. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 88, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharewicz, E.; Della Gatta, P.; Reynolds, J.; Garnham, A.; Crowley, T.; Russell, A.P.; Lamon, S. Identification of microRNAs linked to regulators of muscle protein synthesis and regeneration in young and old skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conboy, I.M.; Conboy, M.J.; Smythe, G.M.; Rando, T.A. Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science 2003, 302, 1575–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavlakadze, T.; McGeachie, J.; Grounds, M.D. Delayed but excellent myogenic stem cell response of regenerating geriatric skeletal muscles in mice. Biogerontology 2010, 11, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Silva, M.T.; da Cunha, F.M.; Moriscot, A.S.; Aoki, M.S.; Miyabara, E.H. Leucine supplementation improves regeneration of skeletal muscles from old rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 72, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.A., Jr.; Brown, L.A.; Lee, D.E.; Brown, J.L.; Baum, J.I.; Greene, N.P.; Washington, T.A. Differential effects of leucine supplementation in young and aged mice at the onset of skeletal muscle regeneration. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2016, 157, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Baptista, I.L.; Carlassara, E.O.; Moriscot, A.S.; Aoki, M.S.; Miyabara, E.H. Leucine supplementation improves skeletal muscle regeneration after cryolesion in rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.A., Jr.; Brown, L.A.; Lee, D.E.; Brown, J.L.; Baum, J.I.; Greene, N.P.; Washington, T.A. The Akt/mTOR pathway: Data comparing young and aged mice with leucine supplementation at the onset of skeletal muscle regeneration. Data Brief 2016, 8, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouisel, E.; Vignaud, A.; Hourde, C.; Butler-Browne, G.; Ferry, A. Muscle weakness and atrophy are associated with decreased regenerative capacity and changes in mTOR signaling in skeletal muscles of venerable (18-24-month-old) dystrophic mdx mice. Muscle Nerve 2010, 41, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Rando, T.A. Emerging models and paradigms for stem cell ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S.; Jasper, H.; Ho, T.T.; Passegue, E. Metabolic regulation of stem cell function in tissue homeostasis and organismal ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.; Kapuria, S.; Riley, R.R.; O’Leary, M.N.; Schreiber, K.H.; Andersen, J.K.; Melov, S.; Que, J.; Rando, T.A.; Rock, J.; et al. mTORC1 Activation during Repeated Regeneration Impairs Somatic Stem Cell Maintenance. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Robinson, A.; Hu, L.; Klein, J.D.; Hassounah, F.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Cai, H.; Wang, X.H. Acupuncture plus Low-Frequency Electrical Stimulation (Acu-LFES) Attenuates Diabetic Myopathy by Enhancing Muscle Regeneration. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaillou, T.; Koulmann, N.; Meunier, A.; Pugniere, P.; McCarthy, J.J.; Beaudry, M.; Bigard, X. Ambient hypoxia enhances the loss of muscle mass after extensive injury. Pflug. Archiv Eur. J. Physiol. 2014, 466, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favier, F.B.; Costes, F.; Defour, A.; Bonnefoy, R.; Lefai, E.; Bauge, S.; Peinnequin, A.; Benoit, H.; Freyssenet, D. Downregulation of Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in skeletal muscle is associated with increased REDD1 expression in response to chronic hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 298, R1659–R1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Nathan, J.A.; Goldberg, A.L. Muscle wasting in disease: Molecular mechanisms and promising therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyajima, A.; Tanaka, M.; Itoh, T. Stem/progenitor cells in liver development, homeostasis, regeneration, and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.A.; Glorioso, J.M.; Nyberg, S.L. Liver regeneration. Transl. Res. 2014, 163, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulos, G.K.; DeFrances, M.C. Liver regeneration. Science 1997, 276, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.K.; Puder, M. Partial hepatectomy in the mouse: Technique and perioperative management. J. Investig. Surg. 2003, 16, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, F.; Kohler, U.A.; Speicher, T.; Werner, S. Regulation of liver regeneration by growth factors and cytokines. EMBO Mol. Med. 2010, 2, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanger, K.; Knigin, D.; Zong, Y.; Maggs, L.; Gu, G.; Akiyama, H.; Pikarsky, E.; Stanger, B.Z. Adult hepatocytes are generated by self-duplication rather than stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Miyajima, A. Liver regeneration by stem/progenitor cells. Hepatology 2014, 59, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Lu, H.; Zou, Q.; Luo, L. Regeneration of liver after extreme hepatocyte loss occurs mainly via biliary transdifferentiation in zebrafish. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.Y.; Ninov, N.; Stainier, D.Y.; Shin, D. Extensive conversion of hepatic biliary epithelial cells to hepatocytes after near total loss of hepatocytes in zebrafish. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, A.; Lu, W.Y.; Man, T.Y.; Ferreira-Gonzalez, S.; O’Duibhir, E.; Dwyer, B.J.; Thomson, J.P.; Meehan, R.R.; Bogorad, R.; Koteliansky, V.; et al. Cholangiocytes act as facultative liver stem cells during impaired hepatocyte regeneration. Nature 2017, 547, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Feng, R.X.; Li, L.; Yi, G.R.; Zhang, X.N.; Yin, C.; Yu, H.Y.; Zhang, J.P.; et al. Chronic Liver Injury Induces Conversion of Biliary Epithelial Cells into Hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasyuk, G.; Patitucci, C.; Espeillac, C.; Pende, M. The role of the mTOR pathway during liver regeneration and tumorigenesis. Ann. D’endocrinologie 2013, 74, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, J.; Wei, X.; Leng, H.; Mu, H.; Cai, P.; Luo, L. mTORC1 Signaling is Required for the Dedifferentiation from Biliary Cell to Bi-potential Progenitor Cell in Zebrafish Liver Regeneration. Hepatology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiyoshi, M.; Ozaki, M. Molecular mechanisms of liver regeneration and protection for treatment of liver dysfunction and diseases. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2011, 18, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, S.; Ozaki, M.; Inoue, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Ogawa, W.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Todo, S. The survival pathways phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3-K)/phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1)/Akt modulate liver regeneration through hepatocyte size rather than proliferation. Hepatology 2009, 49, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouraschen, S.M.; de Ruiter, P.E.; Kwekkeboom, J.; de Bruin, R.W.; Kazemier, G.; Metselaar, H.J.; Tilanus, H.W.; van der Laan, L.J.; de Jonge, J. mTOR signaling in liver regeneration: Rapamycin combined with growth factor treatment. World J. Transplant. 2013, 3, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Won, Y.S.; Yoon, Y.D.; Yoon, W.K.; Nam, K.H.; Choi, I.P.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.C. Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 deficiency accelerates liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yan, H.; Chen, Y.; He, Z. The variation of AkT/TSC1–TSC1/mTOR signal pathway in hepatocytes after partial hepatectomy in rats. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2009, 86, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickheim, D.G.; Nelsen, C.J.; Fassett, J.T.; Timchenko, N.A.; Hansen, L.K.; Albrecht, J.H. Differential regulation of cyclins D1 and D3 in hepatocyte proliferation. Hepatology 2002, 36, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeillac, C.; Mitchell, C.; Celton-Morizur, S.; Chauvin, C.; Koka, V.; Gillet, C.; Albrecht, J.H.; Desdouets, C.; Pende, M. S6 kinase 1 is required for rapamycin-sensitive liver proliferation after mouse hepatectomy. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2821–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-P.; Ballou, L.M.; Lin, R.Z. Rapamycin-insensitive Regulation of 4E-BP1 in Regenerating Rat Liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 10943–10951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmes, D.; Zibert, A.; Budny, T.; Bahde, R.; Minin, E.; Kebschull, L.; Holzen, J.; Schmidt, H.; Spiegel, H.U. Impact of rapamycin on liver regeneration. Virchows Arch. 2008, 452, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matot, I.; Nachmansson, N.; Duev, O.; Schulz, S.; Schroeder-Stein, K.; Frede, S.; Abramovitch, R. Impaired liver regeneration after hepatectomy and bleeding is associated with a shift from hepatocyte proliferation to hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 5283–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, R.; Song, G.; Roll, G.R.; Frandsen, N.M.; Willenbring, H. A microRNA-21 surge facilitates rapid cyclin D1 translation and cell cycle progression in mouse liver regeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pu, S.; Chen, L.; Shen, J.; Cheng, S.; Kuang, J.; Li, H.; Wu, T.; Li, R.; Jiang, W.; et al. Liver-specific Sirtuin6 ablation impairs liver regeneration after 2/3 partial hepatectomy. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rodriguez, J.L.; Barbier-Torres, L.; Fernandez-Alvarez, S.; Gutierrez-de Juan, V.; Monte, M.J.; Halilbasic, E.; Herranz, D.; Alvarez, L.; Aspichueta, P.; Marin, J.J.; et al. SIRT1 controls liver regeneration by regulating bile acid metabolism through farnesoid X receptor and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. Hepatology 2014, 59, 1972–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J.; Xu, P.; Shi, H.; Yue, X.; Ren, F.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Z.; Chen, D. Deficiency of apoptosis-stimulating protein two of p53 promotes liver regeneration in mice by activating mammalian target of rapamycin. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Nguyen, L.H.; Zhou, K.; de Soysa, T.Y.; Li, L.; Miller, J.B.; Tian, J.; Locker, J.; Zhang, S.; Shinoda, G.; et al. Precise let-7 expression levels balance organ regeneration against tumor suppression. Elife 2015, 4, e09431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, K.; Yang, M.; Duan, E.; Zhao, J.; Yu, C.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, W.; et al. Rosmarinic acid stimulates liver regeneration through the mTOR pathway. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Kodama, T.; Hikita, H.; Tanaka, S.; Shigekawa, M.; Nawa, T.; Shimizu, S.; Li, W.; Miyagi, T.; Hiramatsu, N.; et al. Carbamazepine promotes liver regeneration and survival in mice. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Wu, H.; Bai, H.; Wang, M.; Wen, J.; Gong, J.; Miao, M.; Yuan, F. Panax notoginseng saponins promote liver regeneration through activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR cell proliferation pathway and upregulation of the AKT/Bad cell survival pathway in mice. BMC Complement. Altern Med. 2019, 19, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.X.; Li, C.H.; Zhang, A.Q.; Jiang, S.; Lai, Y.H.; Ge, X.L.; Pan, K.; Dong, J.H. mTOR-Dependent Suppression of Remnant Liver Regeneration in Liver Failure After Massive Liver Resection in Rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 2718–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, S.; Ogawa, W.; Inoue, H.; Terui, K.; Ogino, T.; Igarashi, R.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Enosawa, S.; Furukawa, H.; et al. Compensatory recovery of liver mass by Akt-mediated hepatocellular hypertrophy in liver-specific STAT3-deficient mice. J. Hepatol. 2005, 43, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas-Paz, L.; Sun, T.; Pikiolek, M.; Cochran, N.R.; Bergling, S.; Orsini, V.; Yang, Z.; Sigoillot, F.; Jetzer, J.; Syed, M.; et al. YAP, but Not RSPO-LGR4/5, Signaling in Biliary Epithelial Cells Promotes a Ductular Reaction in Response to Liver Injury. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturantabut, S.; Shwartz, A.; Evason, K.J.; Cox, A.G.; Labella, K.; Schepers, A.G.; Yang, S.; Acuna, M.; Houvras, Y.; Mancio-Silva, L.; et al. Estrogen Activation of G-Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor 1 Regulates Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase and mTOR Signaling to Promote Liver Growth in Zebrafish and Proliferation of Human Hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1788–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, N. Liver regeneration: From laboratory to clinic. Liver Transpl. 2001, 7, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataller, R.; Brenner, D.A. Liver fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, M.; Uribe-Echevarria, S.; Mandiola, C.; Zapata, M.I.; Riquelme, F.; Romanque, P. Insight on ALPPS—Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy—Mechanisms: Activation of mTOR pathway. HPB (Oxf.) 2018, 20, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Lv, X.; Liang, R.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q. Suppression of graft regeneration, not ischemia/reperfusion injury, is the primary cause of small-for-size syndrome after partial liver transplantation in mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Rehman, H.; Krishnasamy, Y.; Haque, K.; Schnellmann, R.G.; Lemasters, J.J.; Zhong, Z. Amphiregulin stimulates liver regeneration after small-for-size mouse liver transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2012, 12, 2052–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehart, H.; Clevers, H. Tales from the crypt: New insights into intestinal stem cells. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biteau, B.; Hochmuth, C.E.; Jasper, H. JNK activity in somatic stem cells causes loss of tissue homeostasis in the aging Drosophila gut. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 3, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Patel, P.H.; Kohlmaier, A.; Grenley, M.O.; McEwen, D.G.; Edgar, B.A. Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell 2009, 137, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amcheslavsky, A.; Ito, N.; Jiang, J.; Ip, Y.T. Tuberous sclerosis complex and Myc coordinate the growth and division of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 193, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makky, K.; Tekiela, J.; Mayer, A.N. Target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling controls epithelial morphogenesis in the vertebrate intestine. Dev. Biol. 2007, 303, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.; Kljavin, N.M.; Ybarra, R.; de Sauvage, F.J. Lgr5+ stem cells are indispensable for radiation-induced intestinal regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Es, J.H.; Sato, T.; van de Wetering, M.; Lyubimova, A.; Yee Nee, A.N.; Gregorieff, A.; Sasaki, N.; Zeinstra, L.; van den Born, M.; Korving, J.; et al. Dll1+ secretory progenitor cells revert to stem cells upon crypt damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, P.W.; Basak, O.; Farin, H.F.; Wiebrands, K.; Kretzschmar, K.; Begthel, H.; van den Born, M.; Korving, J.; de Sauvage, F.; van Es, J.H.; et al. Replacement of Lost Lgr5-Positive Stem Cells through Plasticity of Their Enterocyte-Lineage Daughters. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Tong, K.; Zhao, Y.; Balasubramanian, I.; Yap, G.S.; Ferraris, R.P.; Bonder, E.M.; Verzi, M.P.; Gao, N. Paneth Cell Multipotency Induced by Notch Activation following Injury. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Huang, D.G.; Qin, Y.C.; Li, X.G.; Gao, C.Q.; Yan, H.C.; Wang, X.Q. mTORC1 signaling activation increases intestinal stem cell activity and promotes epithelial cell proliferation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 19028–19038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, M.; Guarente, L. mTORC1 and SIRT1 Cooperate to Foster Expansion of Gut Adult Stem Cells during Calorie Restriction. Cell 2016, 166, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, G.H.; Morton, J.P.; Myant, K.; Phesse, T.J.; Ridgway, R.A.; Marsh, V.; Wilkins, J.A.; Athineos, D.; Muncan, V.; Kemp, R.; et al. Focal adhesion kinase is required for intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis downstream of Wnt/c-Myc signaling. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahama, Y.; Shimoda, M.; Mao, G.; Singh, S.K.; Kozakai, Y.; Sun, X.; Motooka, D.; Nakamura, S.; Tanaka, H.; Satoh, T.; et al. Regnase-1 controls colon epithelial regeneration via regulation of mTOR and purine metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11036–11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.P.; Myant, K.B.; Sansom, O.J. A FAK-PI-3K-mTOR axis is required for Wnt-Myc driven intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle 2014, 10, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, W.J.; Jackson, T.J.; Knight, J.R.; Ridgway, R.A.; Jamieson, T.; Karim, S.A.; Jones, C.; Radulescu, S.; Huels, D.J.; Myant, K.B.; et al. mTORC1-mediated translational elongation limits intestinal tumour initiation and growth. Nature 2015, 517, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Gao, N.; Li, L.; Gao, G.; Wei, G.; Chen, Z.; et al. Repression of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 Inhibits Intestinal Regeneration in Acute Inflammatory Bowel Disease Models. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, A. mTOR-dependent autophagy contributes to end-organ resistance and serves as target for treatment in autoimmune disease. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, K.; Chong, Z.Z.; Shang, Y.C.; Wang, S. mTOR: On target for novel therapeutic strategies in the nervous system. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, V.; Jalan, R. Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Definition, Diagnosis, and Clinical Characteristics. Semin. Liver Dis. 2016, 36, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Newman, M.R.; Ackun-Farmmer, M.; Baranello, M.P.; Sheu, T.-J.; Puzas, J.E.; Benoit, D.S.W. Fracture-Targeted Delivery of β-Catenin Agonists via Peptide-Functionalized Nanoparticles Augments Fracture Healing. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9445–9458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.-W.; Kelly, R.; Winans, T.; Marchena, I.; Shadakshari, A.; Yu, J.; Dawood, M.; Garcia, R.; Tily, H.; Francis, L.; et al. Sirolimus in patients with clinically active systemic lupus erythematosus resistant to, or intolerant of, conventional medications: A single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, X.; Luo, L.; Chen, J. Roles of mTOR Signaling in Tissue Regeneration. Cells 2019, 8, 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8091075

Wei X, Luo L, Chen J. Roles of mTOR Signaling in Tissue Regeneration. Cells. 2019; 8(9):1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8091075

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Xiangyong, Lingfei Luo, and Jinzi Chen. 2019. "Roles of mTOR Signaling in Tissue Regeneration" Cells 8, no. 9: 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8091075

APA StyleWei, X., Luo, L., & Chen, J. (2019). Roles of mTOR Signaling in Tissue Regeneration. Cells, 8(9), 1075. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8091075