Potential Proteins Associated with Canine Epididymal Sperm Motility

Highlights

- Dog epididymal sperm with differing progressive motility exhibit unique protein profile signatures.

- Ce10 and NPC2 differed significantly between good and poor sperm motility groups and may serve as motility-related sperm proteins.

- A comprehensive analysis of the protein components of epididymal sperm in relation to their functional features may serve to select protein markers of epididymal semen quality.

- Ce10 and NPC2 emerge as promising candidates for molecular biomarkers associated with canine epididymal sperm motility.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Media

2.2. Animals

2.3. Cauda Epididymal Semen Collection

2.4. Cauda ES Quality Assessment

2.5. Cluster Analysis

2.6. Preliminary Sample Preparation

2.7. Sample Preparation for Proteomic Analysis

2.7.1. Sample Preparation for NanoUPLC-Q-TOF/MS

2.7.2. In-Solution Trypsin Digestion

2.8. NanoUPLC-Q-TOF/MS

- from 0 to 2 min: 5% B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile);

- from 2 to 15 min: 5% to 30% B;

- from 15 to 45 min: 30% to 60% B;

- from 45 to 48 min: 60% to 85% B;

- from 45 to 58 min: held at 85% B;

- from 58 to 58.5 min: reduced back to 5% B.

2.9. Bioinformatic Analyses and Imaging of Data

2.10. Western Blot Analysis

- Bcl-10 rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog number: PA5-88067, Thermo Fisher Scientific; dilution 1:500; the gene name Bcl-10 was used as the alias name for ce10, according to the manufacturer’s information, it is an antibody that recognizes ce10),

- NPC2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog number: PA5-51463, Thermo Fisher Scientific; dilution 1:500), and,

- rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (catalog number: G9545, Sigma-Aldrich; dilution 1:2000), as a loading control.

2.11. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

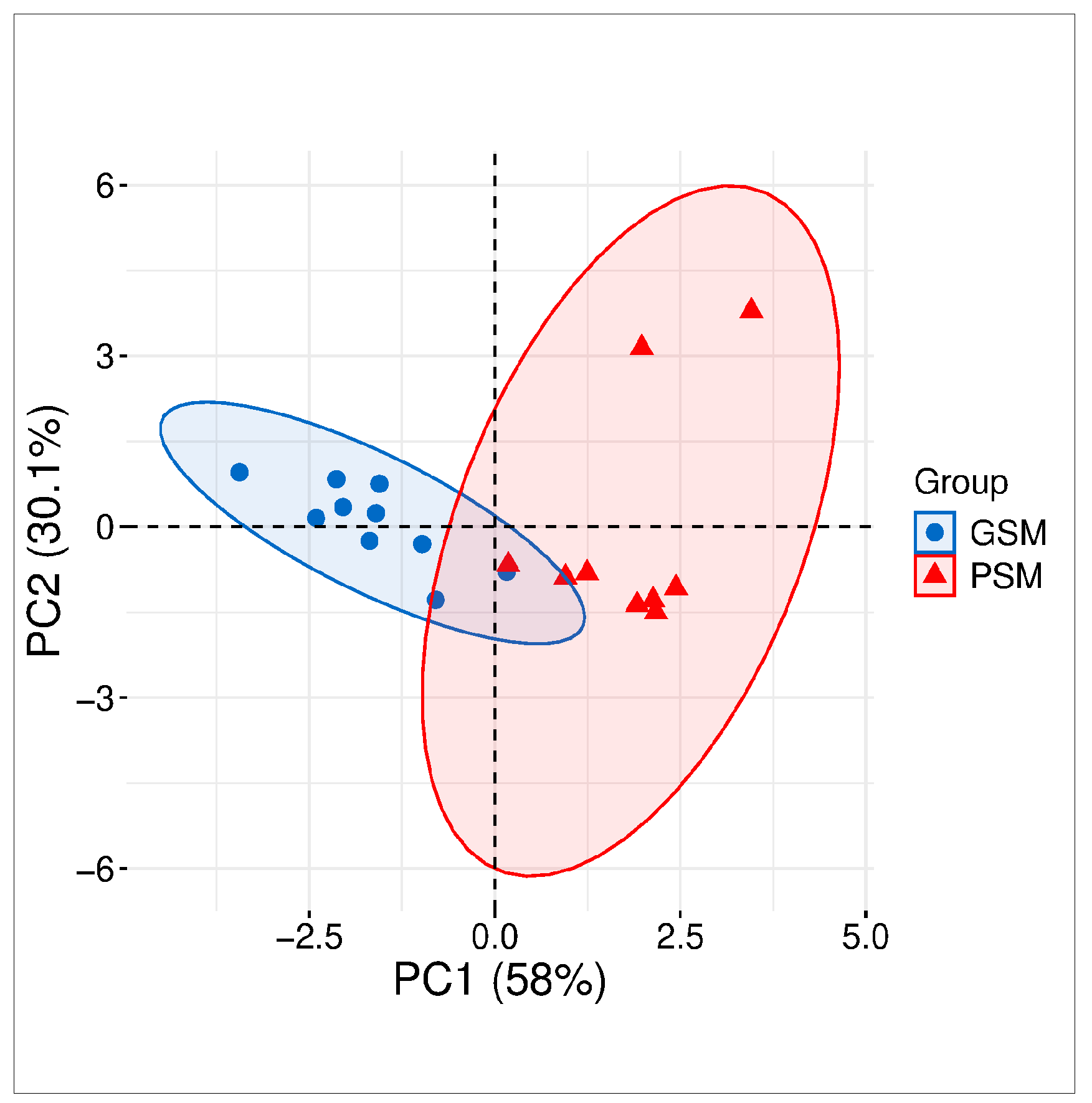

3.1. Cluster Analysis

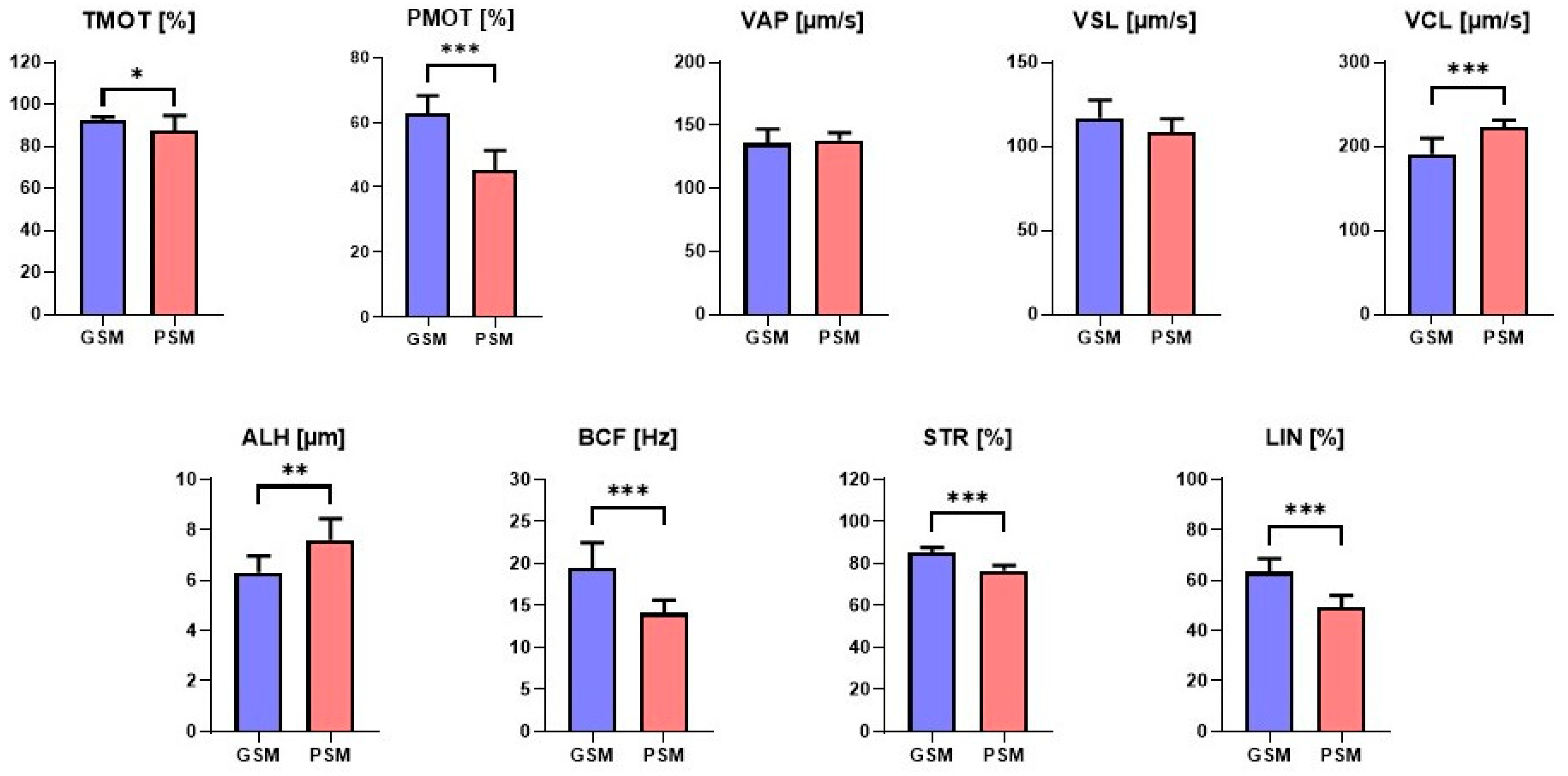

3.2. ES Motility and Motion Parameters in Research Groups

3.3. Whole ES Proteome Profiling According to Research Group

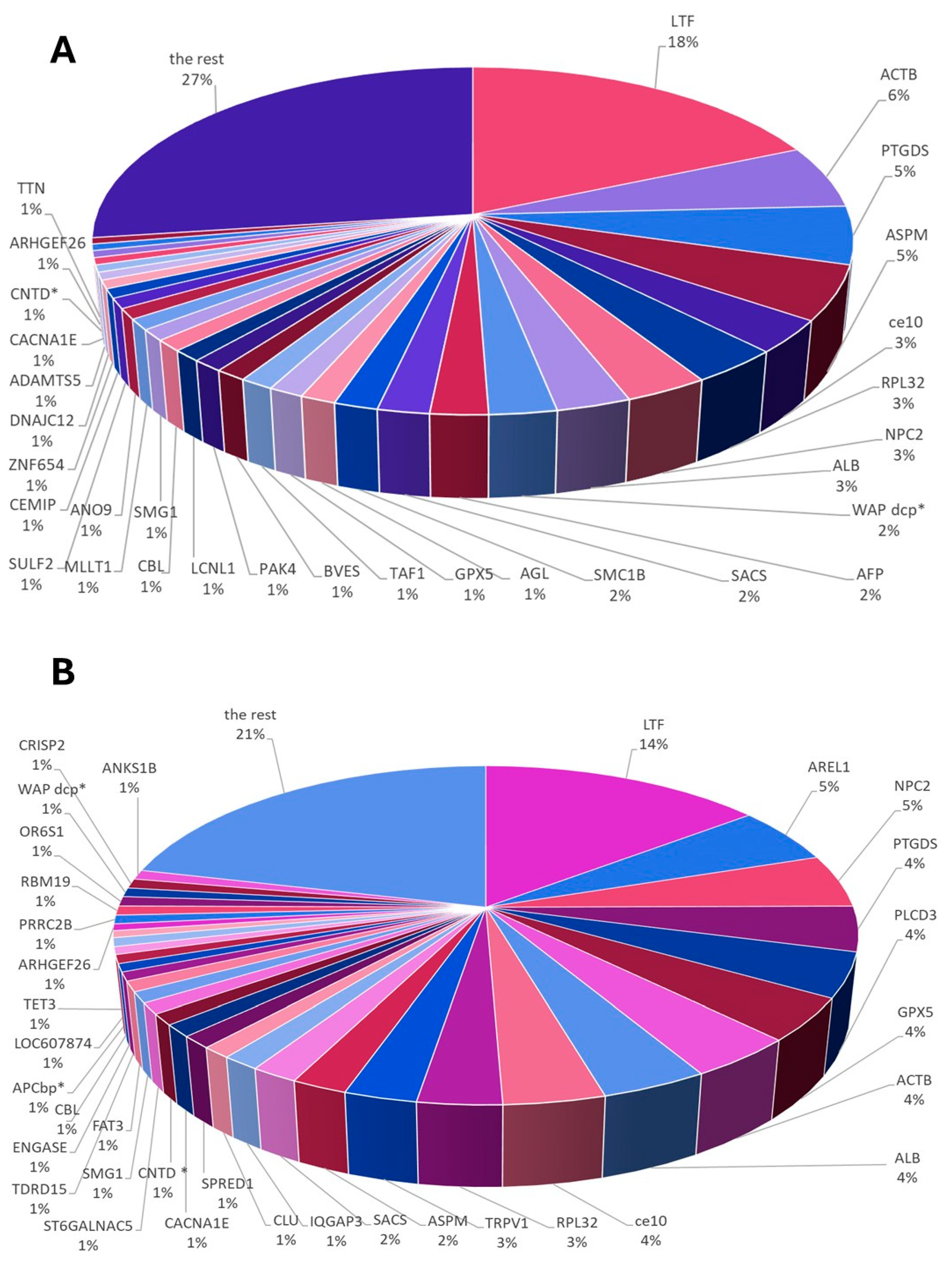

3.3.1. Protein Contribution in GSM and PSM Groups

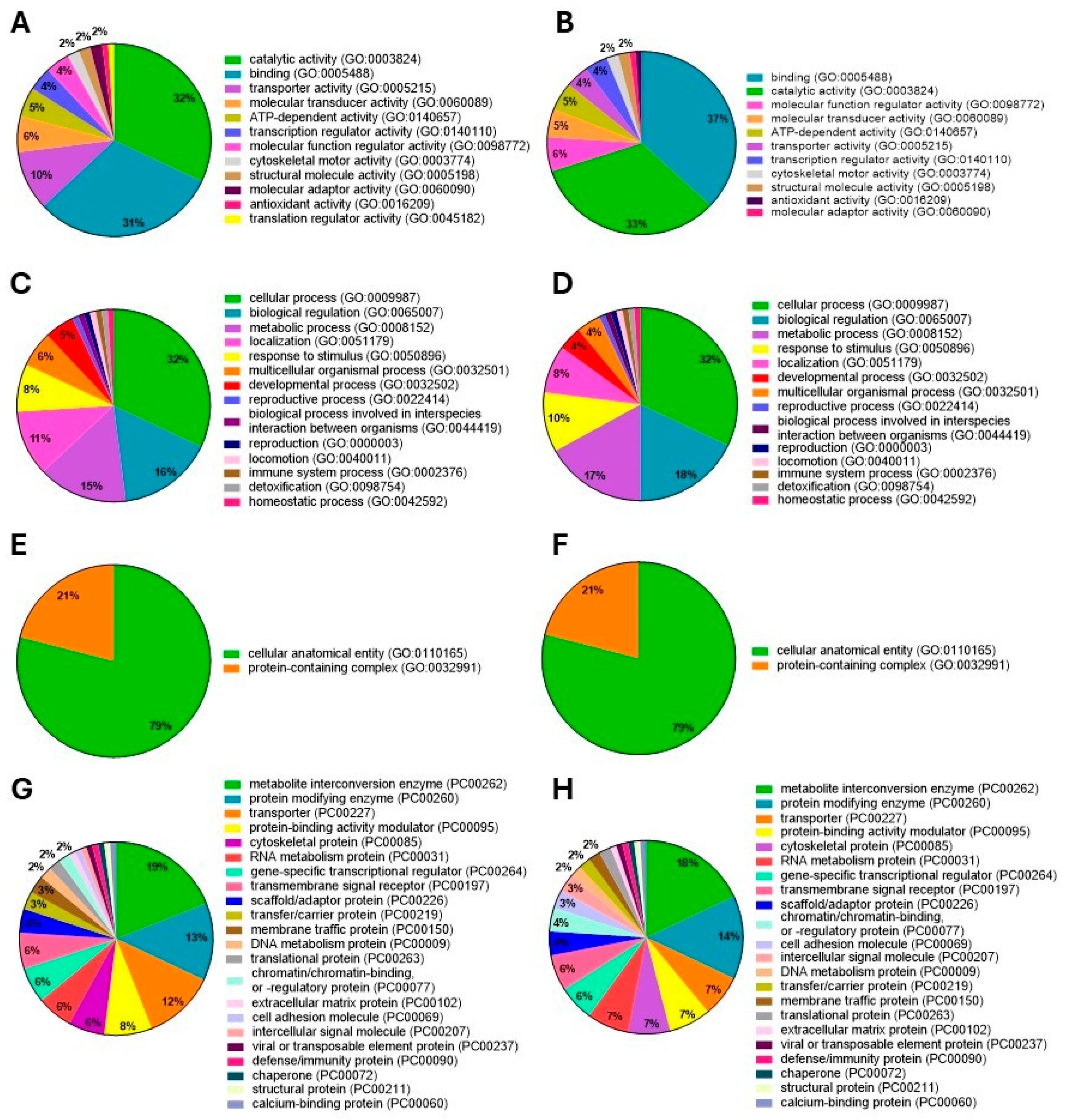

3.3.2. Gene Ontology

3.4. Selection of Potential MRSPs

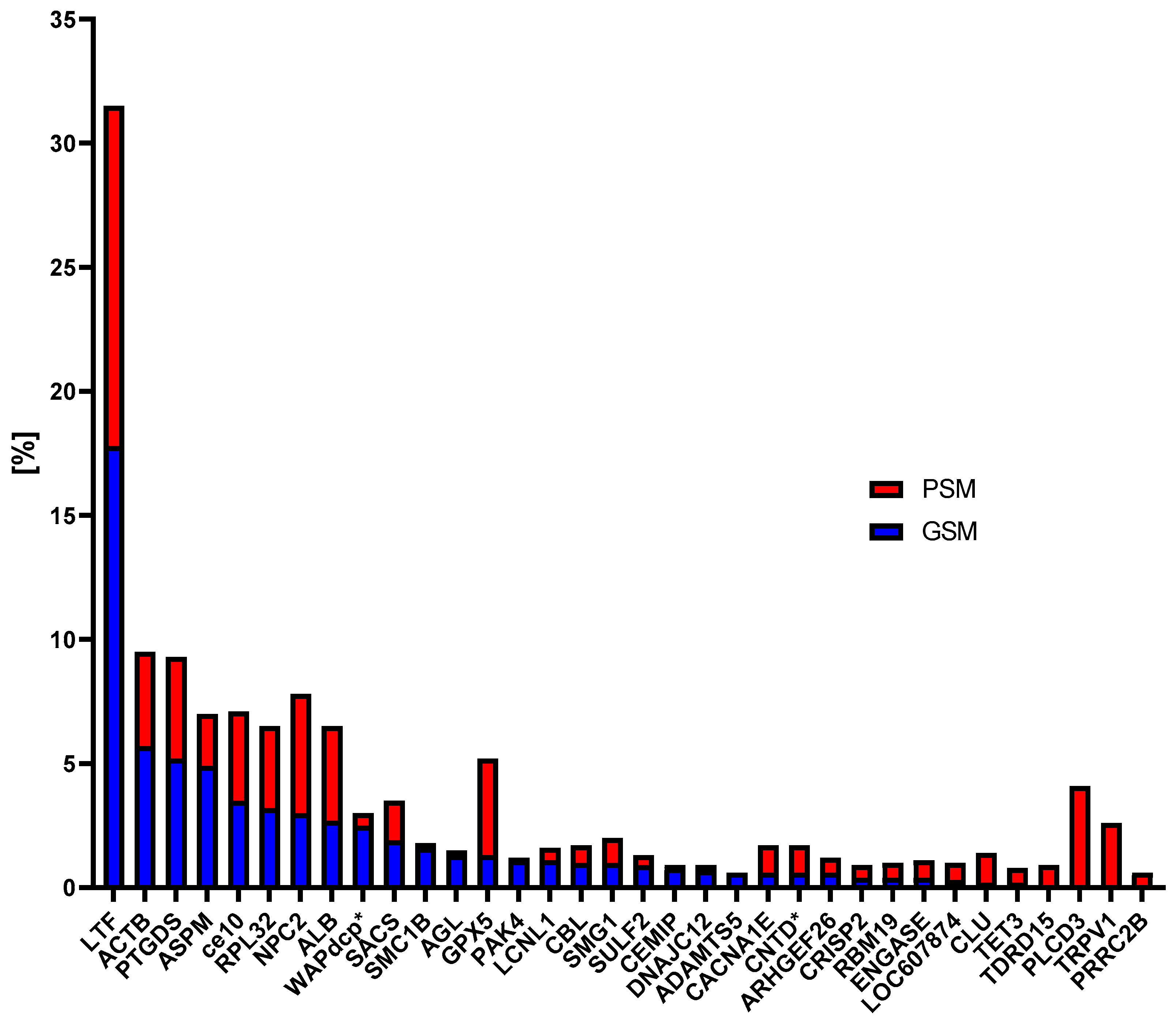

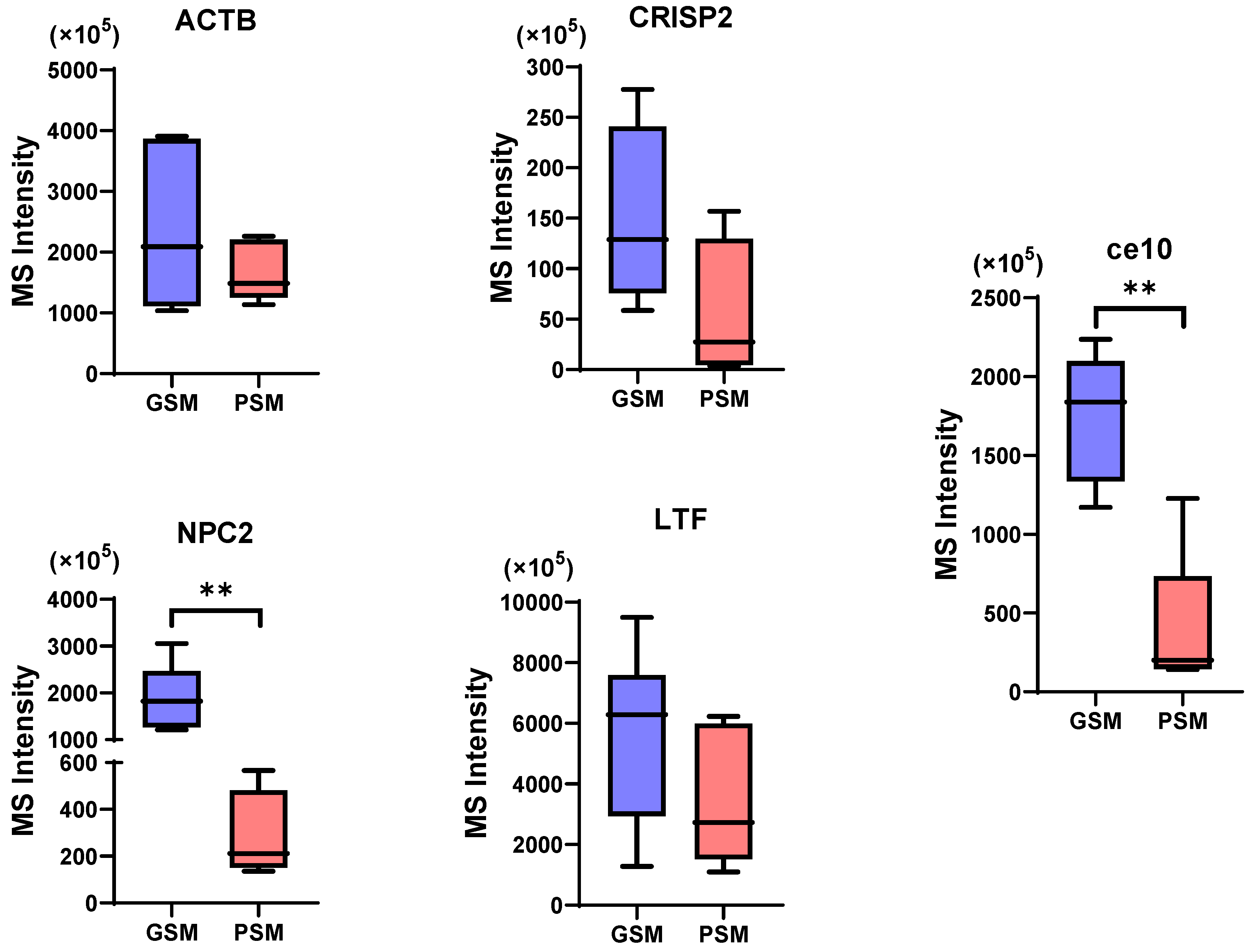

3.4.1. Analysis of the CPs Content in the Research Groups

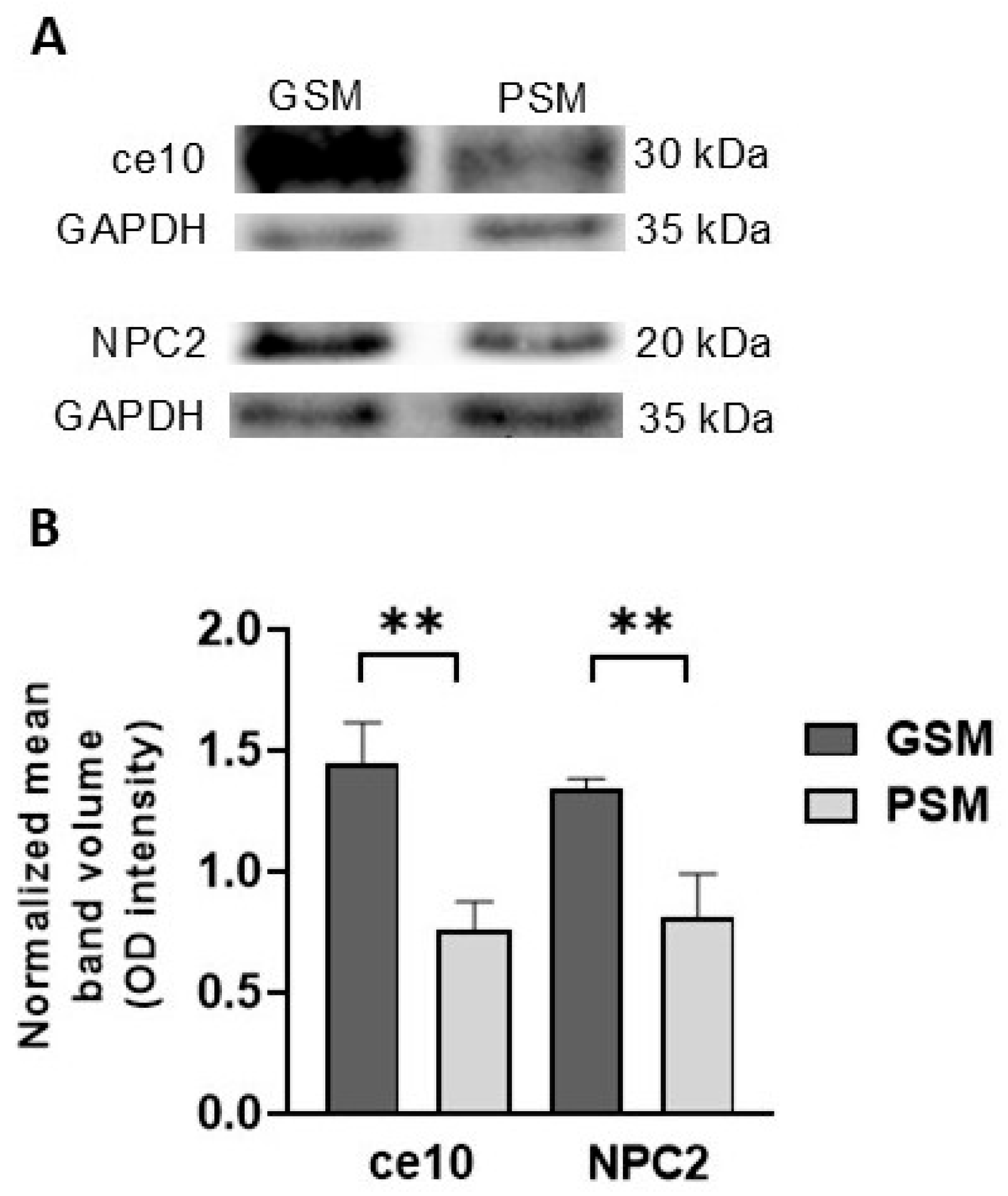

3.4.2. Validation of Potential MRSPs

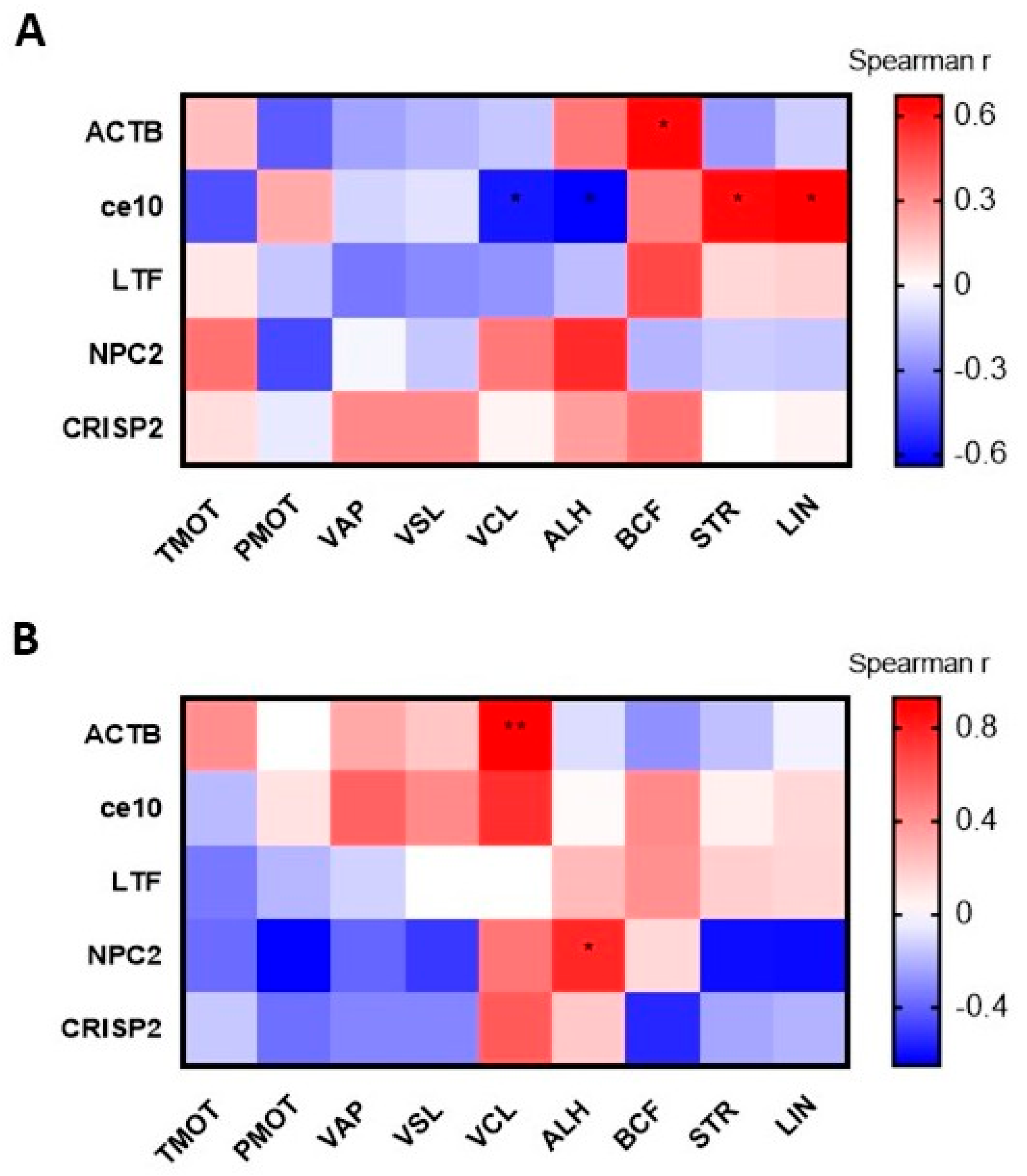

3.4.3. Correlation Between the CPs Content and ES Motility

4. Discussion

| Protein | Functions in Reproductive Processes | References |

|---|---|---|

| ACTB (Actin, cytoplasmic 1) |

| [9,15,30,31,32] |

| ce10 (CE10 protein) |

| [9,15,44,45,46,47,48,49] |

| CRISP2 (Cysteine-rich secretory protein 2) |

| [15,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] |

| LTF (Lactotransferrin) |

| [60,61,62] |

| NPC2 (NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 2) |

| [15,36,38,39,40,43] |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTB | Actin cytoplasmic 1 |

| ADAMTS5 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 5 |

| AFP | alpha fetoprotein |

| AGL | Glycogen debranching enzyme |

| AKAP4 | A-Kinase anchoring protein 4 |

| ALB/ALBs | Albumin/Albumins |

| ALH | Amplitude of lateral head displacement |

| ANKS1B | Ankyrin repeat and sterile alpha motif domain-containing protein 1B |

| ANO9 | Anoctamin-9 |

| APCbp* | APC-binding protein EB1 |

| AREL1 | Apoptosis-resistant E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 |

| ASPM | Abnormal spindle-like microcephaly-associated protein homolog |

| BCF | Beat cross frequency |

| BP | Biological process (GO category) |

| BVES | Blood vessel epicardial substance |

| CASA | Computer-assisted semen analysis |

| CC | Cellular component (GO category) |

| ce10 | CE10 protein (canine epididymal protein 10) |

| CBL | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CBL |

| CEMIP | Hyaluronoglucosaminidase |

| CLU | Clusterin |

| CPs | Common proteins |

| CRISP2 | Cysteine-rich secretory protein 2 |

| CNTD* | Cyclin N-terminal domain-containing protein |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline |

| ES | Epididymal sperm |

| ENGASE | Endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| FAT3 | FAT atypical cadherin 3 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GPX5 | Glutathione peroxidase 5 |

| GSM | Good sperm motility group |

| HE | Human epididymal proteins |

| IQGAP3 | IQ motif-containing GTPase-activating protein 3 |

| LCNL1 | Lipocln_cytosolic_FA-bd_dom domain-containing protein |

| LC–MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LIN | Linearity |

| LOC607874 | Cystatin domain-containing protein |

| LTF | Lactotransferrin |

| MF | Molecular function (GO category) |

| MLLT1 | Myeloid/lymphoid leukemia translocated to 1 |

| MMP2 | Metalloproteinase 2 |

| MS/MS | Tandem mass spectrometry |

| MRSPs | Motility-related sperm proteins |

| NanoUPLC-Q-TOF/MS | Nano-ultra performance liquid chromatography–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| NPC2 | NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 2 |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| PAK4 | non-specific serine/threonine protein kinase |

| PC | Protein class (PANTHER) |

| PANTHER | Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PMOT | Progressive motility |

| PSM | Poor sperm motility group |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride membranes |

| PTGDS | Prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer |

| RPL32 | 60S ribosomal protein L32 |

| SACS | Sacsin molecular chaperone |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| SIPs | Sperm intracellular proteins |

| SMAPs | Sperm membrane-associated proteins |

| SMC1B | Structural maintenance of chromosomes protein |

| SPRED1 | Sprouty-related EVH1 domain-containing protein 1 |

| STR | Straightness |

| ST6GALNAC5 | ST6 N-acetylgalactosaminide alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase 5 |

| SWISSPROT | Swiss-Prot protein database |

| TAF1 | Transcription initiation factor TFIID subunit |

| TMOT | Total motility |

| TET3 | Methylcytosine dioxygenase TET3 |

| TRPV1 | Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 |

| TTN | Titin |

| UPs | Unique proteins |

| VAP | Average path velocity |

| VCL | Curvilinear velocity |

| VSL | Straight-line velocity |

| v/v | Volume per volume |

| WAPdcp* | WAP domain-containing protein |

| ZNF654 | Zinc finger protein 654 |

References

- Chakraborty, S.; Saha, S. Understanding sperm motility mechanisms and the implication of sperm surface molecules in promoting motility. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2022, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E.R.; Carrell, D.T.; Aston, K.I.; Jenkins, T.G.; Yeste, M.; Salas-Huetos, A. The Role of the Epididymis and the Contribution of Epididymosomes to Mammalian Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasi, M.G.; Visconti, P.E. Molecular changes and signaling events occurring in spermatozoa during epididymal maturation. Andrology 2017, 5, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Hassan, H.; Domain, G.; Luvoni, G.C.; Chaaya, R.; Van Soom, A.; Wydooghe, E. Canine and Feline Epididymal Semen-A Plentiful Source of Gametes. Animals 2021, 11, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogielnicka-Brzozowska, M.; Cichowska, A.W. Molecular Biomarkers of Canine Reproductive Functions. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 6139–6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkgren, I.; Sipilä, P. The impact of epididymal proteins on sperm function. Reproduction 2019, 158, R155–R167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, E.; Scapigliati, G.; Pascarelli, N.A.; Baccetti, B.; Collodel, G. Localization of AKAP4 and tubulin proteins in sperm with reduced motility. Asian J. Androl. 2007, 9, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tentes, I.; Asimakopoulos, B.; Mourvati, E.; Diedrich, K.; Al-Hasani, S.; Nikolettos, N. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 in seminal plasma. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2007, 24, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichowska, A.W.; Wisniewski, J.; Bromke, M.A.; Olejnik, B.; Mogielnicka-Brzozowska, M. Proteome Profiling of Canine Epididymal Fluid: In Search of Protein Markers of Epididymal Sperm Motility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekin, K.; Kurtdede, E.; Salmanoğlu, B.; Uysal, O.; Stelletta, C. Osteopontin Concentration in Prostates Fractions: A Novel Marker of Sperm Quality in Dogs. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Swerdloff, R.S. Limitations of semen analysis as a test of male fertility and anticipated needs from newer tests. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 1502–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottola, F.; Palmieri, I.; Carannante, M.; Barretta, A.; Roychoudhury, S.; Rocco, L. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Male Infertility: Established Methodologies and Future Perspectives. Genes 2024, 15, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ďuračka, M.; Benko, F.; Tvrdá, E. Molecular Markers: A New Paradigm in the Prediction of Sperm Freezability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Angrimani, D.S.; Nichi, M.; Losano, J.D.A.; Lucio, C.F.; Lima Veiga, G.A.; Franco, M.V.M.J.; Franco, M.V.M.J.; Vannucchi, C.I. Fatty acid content in epididymal fluid and spermatozoa during sperm maturation in dogs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmudzinska, A.; Wisniewski, J.; Mlynarz, P.; Olejnik, B.; Mogielnicka-Brzozowska, M. Age-Dependent Variations in Functional Quality and Proteomic Characteristics of Canine (Canis lupus familiaris) Epididymal Spermatozoa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacheux, J.L.; Belghazi, M.; Lanson, Y.; Dacheux, F. Human epididymal secretome and proteome. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2006, 250, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intasqui, P.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.; Samanta, L.; Bertolla, R.P. Towards the identification of reliable sperm biomarkers for male infertility: A sperm proteomic approach. Andrologia 2018, 50, e12919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogielnicka-Brzozowska, M.; Prochowska, S.; Niżański, W.; Bromke, M.A.; Wiśniewski, J.; Olejnik, B.; Kuzborska, A.; Fraser, L.; Młynarz, P.; Kordan, W. Proteome of cat semen obtained after urethral catheterization. Theriogenology 2020, 141, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelle, W.; Michalski, J.C. Analysis of protein glycosylation by mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1585–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towbin, H.; Staehelin, T.; Gordon, J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: Procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 4350–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, A.; Galgano, M.; Mutinati, M.; Sciorsci, R.L. Alpha-fetoprotein in animal reproduction. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 123, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizejewski, G.J. Biological roles of alpha-fetoprotein during pregnancy and perinatal development. Exp. Biol. Med. 2004, 229, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terentiev, A.A.; Moldogazieva, N.T. Alpha-fetoprotein: A renaissance. Tumour Biol. 2013, 34, 2075–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, P.R.; Foerster, F.; Kudo, M.; Chan, S.L.; Llovet, J.M.; Qin, S.; Schelman, W.R.; Chintharlapalli, S.; Abada, P.B.; Sherman, M.; et al. Biology and significance of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 2214–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Wang, Q.; Liu, K.; Dong, X.; Zhu, M.; Li, M. Alpha-Fetoprotein Binding Mucin and Scavenger Receptors: An Available Bio-Target for Treating Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 625936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glowska-Ciemny, J.; Pankiewicz, J.; Malewski, Z.; von Kaisenberg, C.; Kocylowski, R. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)—New aspects of a well-known marker in perinatology. Ginekol. Pol. 2022, 93, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Ng, J.; Nayak, D.; Sivaraman, J. Structural insights into a HECT-type E3 ligase AREL1 and its ubiquitination activities in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 19934–19949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Kim, B.; Shin, D.Y. AREL1 E3 ubiquitin ligase inhibits TNF-induced necroptosis via the ubiquitination of MTX2. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.F.; Hoffmann, E.K.; Mills, J.W. The cytoskeleton and cell volume regulation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001, 130, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Agüeros, J.F.; Hernández-González, E.O.; Mújica, A. The role of F-actin cytoskeleton-associated gelsolin in the guinea pig capacitation and acrosome reaction. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2003, 56, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, S. Effect of cooling (4 °C) and cryopreservation on cytoskeleton actin and protein tyrosine phosphorylation in buffalo spermatozoa. Cryobiology 2016, 72, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.L.; Ma, W.; Zhu, Y.B.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.Y.; An, N.; An, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.H.; Tian, J.H. The microtubule-associated protein ASPM regulates spindle assembly and meiotic progression in mouse oocytes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouprina, N.; Pavlicek, A.; Collins, N.K.; Nakano, M.; Noskov, V.N.; Ohzeki, J.; Mochida, G.H.; Risinger, J.I.; Goldsmith, P.; Gunsior, M. The microcephaly ASPM gene is expressed in proliferating tissues and encodes for a mitotic spindle protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüers, G.H.; Michels, M.; Schwaab, U.; Franz, T. Murine calmodulin-binding protein 1 (Calmbp1): Tissue-specific expression during development and in adult tissues. Mech. Dev. 2002, 118, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naureckiene, S.; Sleat, D.E.; Lackland, H.; Fensom, A.; Vanier, M.T.; Wattiaux, R.; Jadot, M.; Lobel, P. Identification of HE1 as the second gene of Niemann-Pick C disease. Science 2000, 290, 2298–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanier, M.T. Niemann–pick diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 113, 1717–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterhoff, C.; Kirchhoff, C.; Krull, N.; Ivell, R. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel human sperm antigen (HE2) specifically expressed in the proximal epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 1994, 50, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sèdes, L.; Thirouard, L.; Maqdasy, S.; Garcia, M.; Caira, F.; Lobaccaro, J.-M.A.; Beaudoin, C.; Volle, D.H. Cholesterol: A Gatekeeper of Male Fertility? Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, C.G.; Lindsay, K.S. Corrected cholesterol, a novel marker for predicting semen post-thaw quality: A pilot study. Hum. Fertil. 2017, 22, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busso, D.; Onate-Alvarado, M.J.; Balboa, E.; Castro, J.; Lizama, C.; Morales, G.; Vargas, S.; Hartel, S.; Moreno, R.D.; Zanlungo, S. Spermatozoa from mice deficient in Niemann-Pick disease type C2 (NPC2) protein have defective cholesterol content and reduced in vitro fertilizing ability. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2014, 26, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnis, E.Z.; Crowe, L.M.; Berger, T.; Anchordoguy, T.J.; Overstreet, J.W.; Crowe, J.H. Cold shock damage is due to lipid phase transitions in cell membranes: A demonstration using sperm as a model. J. Exp. Zool. 1993, 265, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, J.; Yeste, M.; Quintero-Moreno, A.; Nino-Cardenas, C.D.P.; Henao, F.J. Relative content of Niemann-Pick C2 protein (NPC2) in seminal plasma, but not that of spermadhesin AQN-1, is related to boar sperm cryotolerance. Theriogenology 2020, 145, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchhoff, C. The dog as a model to study human epididymal function at a molecular level. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 8, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, K.; Pera, I.; Hartung, S.; Ivell, R. Gene expression in the dog epididymis: A model for human epididymal function. Int. J. Androl. 1994, 17, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgano, M.; Hampton, G.; Frierson, H. Comprehensive analysis of HE4 expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, K.; Ellerbrock, K.; Pera, I.; Ivell, R.; Kirchhoff, C. Differential expression of novel abundant and highly regionalized mRNAs of the canine epididymis. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1999, 116, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhen, S.; Wan, D.; Cao, J.; Gao, X. Expression and biochemical characterization of recombinant human epididymis protein 4. Protein Expr. Purif. 2014, 102, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurupriya, V.S.; Roy, S.C.; Dhama, K.; Gopinath, D.; Rekha, V.; Aswathi, P.B.; John, J.K.; Gopalakrishnan, A. Proteases and Proteases Inhibitors of Semen—A Review. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2014, 2, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, Y.; Shibahara, H.; Obara, H.; Suzuki, T.; Takamizawa, S.; Yamaguchi, C.; Tsunoda, H.; Sato, I. Relationships between sperm motility characteristics assessed by the computer-aided sperm analysis (CASA) and fertilization rates in vitro. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2001, 18, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.; Holt, W.V.; Moore, H.D.; Reed, H.C.; Curnock, R.M. Objectively measured boar sperm motility parameters correlate with the outcomes of on-farm inseminations: Results of two fertility trials. J. Androl. 1997, 18, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekhuijse, M.L.; Šoštarić, E.; Feitsma, H.; Gadella, B.M. Application of computer-assisted semen analysis to explain variations in pig fertility. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, T.; Sakashita, M.; Ohba, Y.; Nakanishi, Y. Molecular cloning of the rat Tpx-1 responsible for the interaction between spermatogenic and Sertoli cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 248, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Teng, M.; Niu, L.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Hao, Q. Crystal structure of the cysteine-rich secretory protein stecrisp reveals that the cysteine-rich domain has a K+ channel inhibitor-like fold. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 12405–12412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G.M.; Scanlon, M.J.; Swarbrick, J.; Curtis, S.; Gallant, E.; Dulhunty, A.F.; O’Bryan, M.K. The cysteine-rich secretory protein domain of Tpx-1 is related to ion channel toxins and regulates ryanodine receptor Ca2+ signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 4156–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamsai, D.; Reilly, A.; Smith, S.J.; Gibbs, G.M.; Baker, H.W.G.; McLachlan, R.I.; de Kretser, D.M.; O’Bryan, M.K. Polymorphisms in the human cysteine-rich secretory protein 2 (CRISP2) gene in Australian men. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 2151–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Schneiter, R. Pathogen-related yeast (PRY) proteins and members of the CAP superfamily are secreted sterol binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16882–16887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.H.; Zhou, Q.Z.; Lyu, X.M.; Zhu, T.; Chen, Z.J.; Chen, M.K.; Xia, H.; Wang, C.Y.; Qi, T.; Li, X.; et al. The expression of cysteine rich secretory protein 2 (CRISP2) and its specific regulator miR-27b in the spermatozoa of patients with asthenozoospermia. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 92, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, M.; Metzger, J.; Martinsson, G.; Sieme, H.; Distl, O. Genome-wide association study for semen quality traits in German Warmblood stallions. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 171, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlerova, L.; Bartoskova, A.; Faldyna, M. Lactoferrin: A review. Vet. Med. 2008, 53, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiso, W.K.; Selvaraj, V.; Nagashima, J.; Asano, A.; Brown, J.L.; Schmitt, D.L.; Leszyk, J.; Travis, A.J.; Pukazhenthi, B.S. Lactotransferrin in Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) seminal plasma correlates with semen quality. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Wang, C.; Song, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, G. Effect of lactoferrin on ram sperm motility after cryopreservation. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 35, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mogielnicka-Brzozowska, M.; Cichowska-Likszo, A.W.; Likszo, P.; Fraser, L.; Popielarczyk, W.; Pieklik, J.; Kamińska, M.; Luvoni, G.C. Potential Proteins Associated with Canine Epididymal Sperm Motility. Cells 2026, 15, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010085

Mogielnicka-Brzozowska M, Cichowska-Likszo AW, Likszo P, Fraser L, Popielarczyk W, Pieklik J, Kamińska M, Luvoni GC. Potential Proteins Associated with Canine Epididymal Sperm Motility. Cells. 2026; 15(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleMogielnicka-Brzozowska, Marzena, Aleksandra Wiktoria Cichowska-Likszo, Pawel Likszo, Leyland Fraser, Weronika Popielarczyk, Julia Pieklik, Maja Kamińska, and Gaia Cecilia Luvoni. 2026. "Potential Proteins Associated with Canine Epididymal Sperm Motility" Cells 15, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010085

APA StyleMogielnicka-Brzozowska, M., Cichowska-Likszo, A. W., Likszo, P., Fraser, L., Popielarczyk, W., Pieklik, J., Kamińska, M., & Luvoni, G. C. (2026). Potential Proteins Associated with Canine Epididymal Sperm Motility. Cells, 15(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010085