Evidence for Quasi-High-LET Biological Effects in Clinical Proton Beams That Suppress c-NHEJ and Enhance HR and Alt-EJ

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines, Growth and Irradiation Conditions

2.2. Indirect Immunofluorescence (IF) Analysis of γH2AX, RAD51, and pRPA32-T21 Foci

2.3. Quantitative Image-Based Cytometry (QIBC) Analysis in A549 Cells

2.4. Two-Parametric Flow Cytometry Analysis to Evaluate Activation and Recovery of the G2-Checkpoint in G2-Irradiated Cells

2.5. Multicolor Fluorescence “In Situ” Hybridization (mFISH) Analysis of Hamster Cell Lines

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Increased Dependence on HR Rather than c-NHEJ for Survival in Cells Exposed to Protons Versus X-Rays

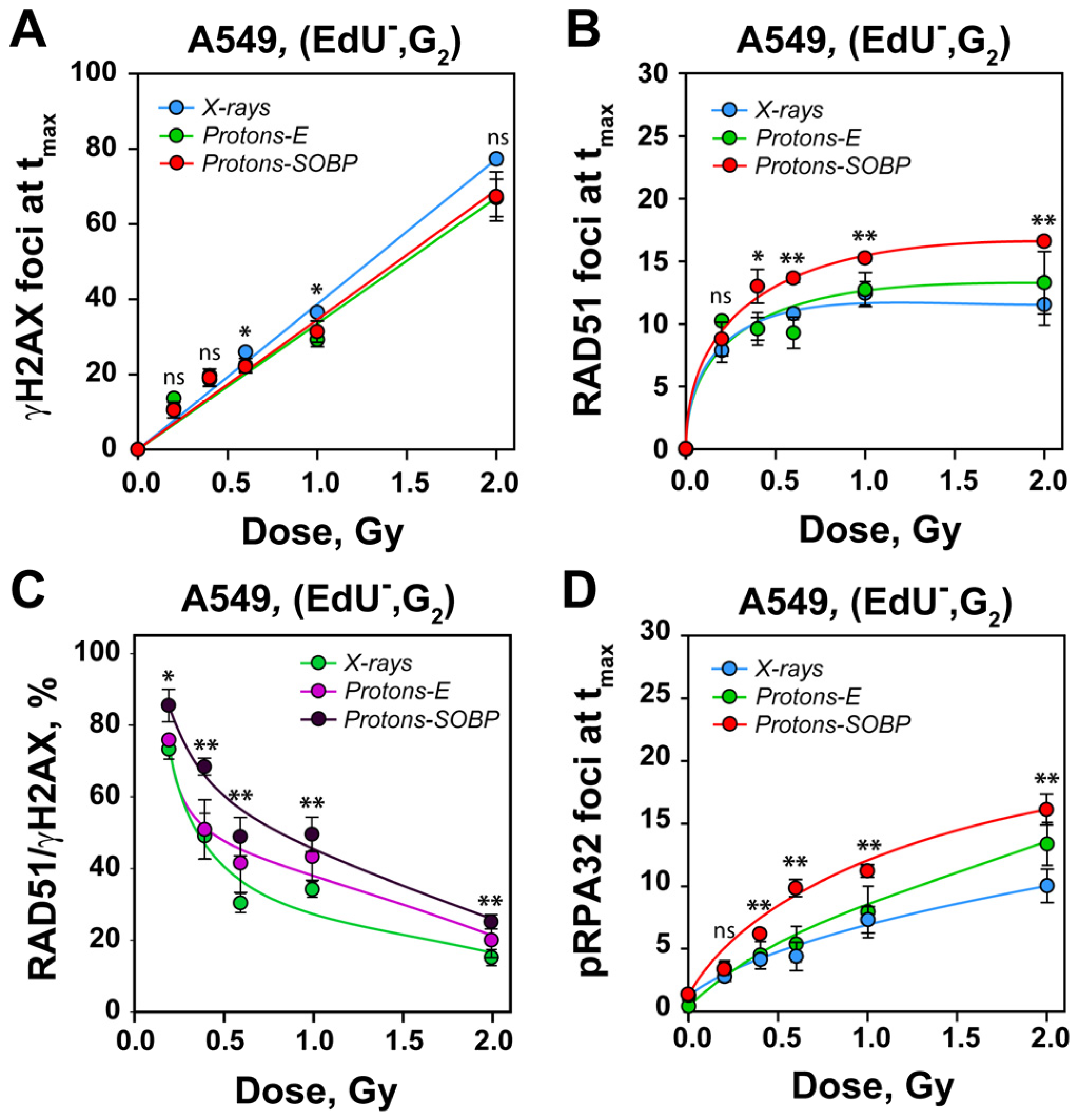

3.2. Enhanced Recruitment of RAD51 Protein to DSBs After Exposure to SOBP Protons Versus X-Rays

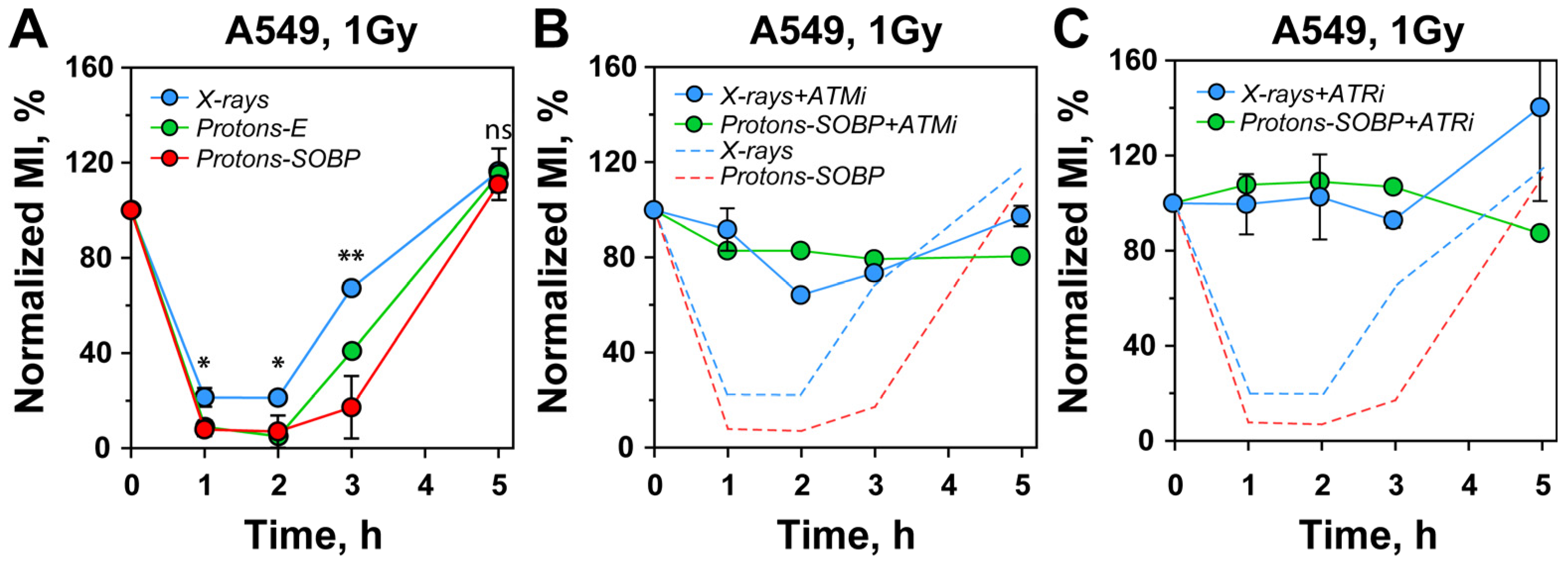

3.3. Stronger G2-Checkpoint Activation After Exposure to Protons

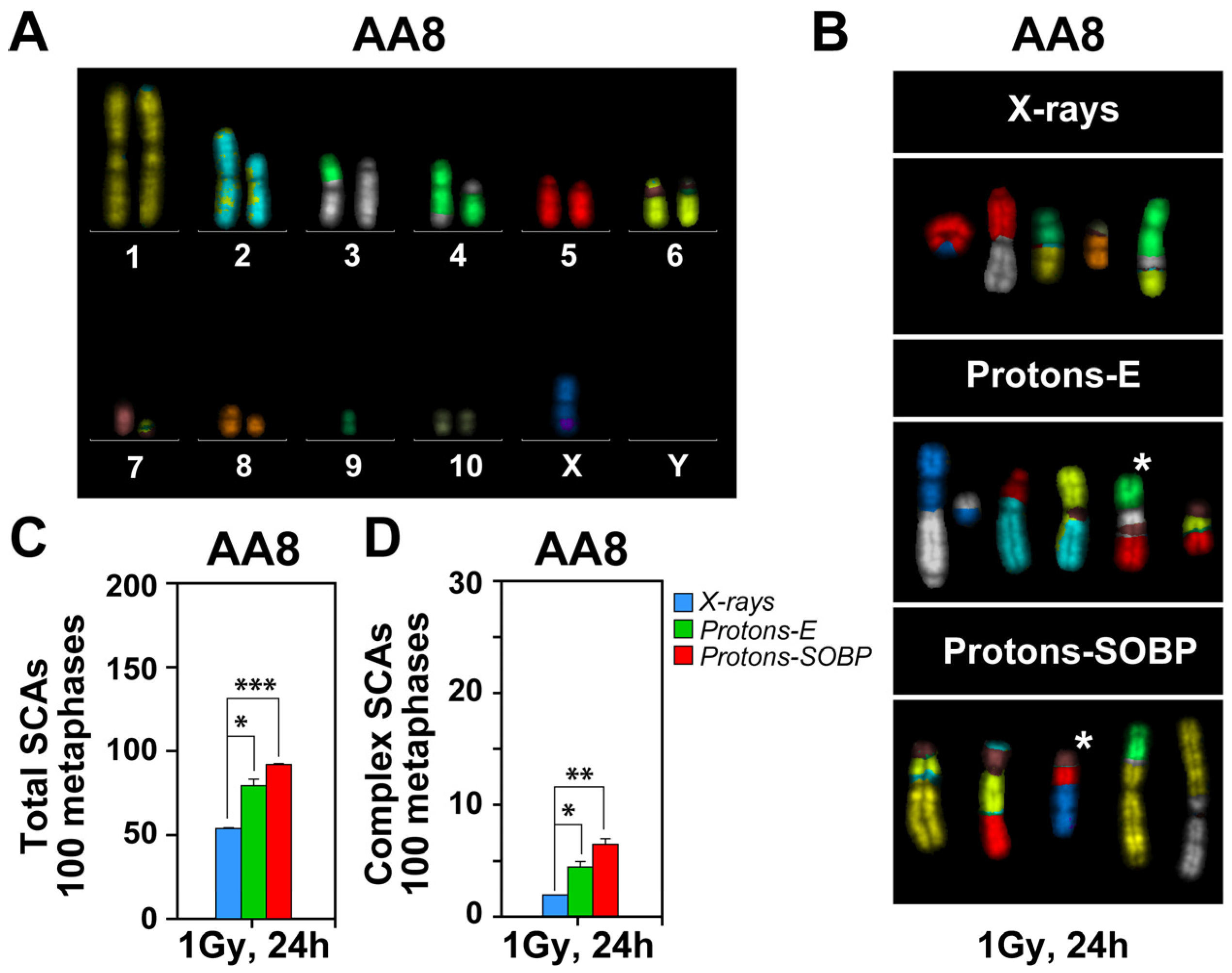

3.4. Enhanced Formation of Chromosomal Abnormalities After Exposure to Protons

4. Discussion

4.1. DSBs Induced by Protons Show Dose-Dependent HR Confinement Similar to X-Rays

4.2. A Quasi High-LET Radiation Component in Proton Beams May Underpin Shifts to HR and Alt-EJ

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IR | Ionizing Radiation |

| LET | Linear Energy Transfer |

| RBE | Relative Biological Effectiveness |

| DSBs | Double-Strand Breaks |

| SOBP | Spread-Out Bragg Peak |

| HR | Homologous Recombination |

| c-NHEJ | Classical Non-Homologous End Joining |

| alt-EJ | Alternative End Joining |

| SSA | Single-Strand Annealing |

| SCAs | Structural Chromosomal Abnormalities |

References

- Mohan, R. A review of proton therapy—Current status and future directions. Precis. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 6, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitti, E.T.; Parsons, J.L. The Radiobiological Effects of Proton Beam Therapy: Impact on DNA Damage and Repair. Cancers 2019, 11, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioen, S.; Vanhove, O.; Vanderstraeten, B.; De Wagter, C.; Engelbrecht, M.; Vandevoorde, C.; De Kock, E.; Van Goethem, M.-J.; Vral, A.; Baeyens, A. Impact of proton therapy on the DNA damage induction and repair in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worawongsakul, R.; Steinmeier, T.; Lin, Y.L.; Bauer, S.; Hardes, J.; Hecker-Nolting, S.; Dirksen, U.; Timmermann, B. Proton Therapy for Primary Bone Malignancy of the Pelvic and Lumbar Region—Data From the Prospective Registries ProReg and KiProReg. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 805051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabbakh, F.; Hosmane, N.S. Enhancement of Radiation Effectiveness in Proton Therapy: Comparison Between Fusion and Fission Methods and Further Approaches. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meester, M.-E.; Paulus, H.; Michiels, C.; Heuskin, A.-C.; Debacq-Chainiaux, F. Senescence Under the Lens: X-ray vs. Proton Irradiation at Conventional and Ultra-High Dose Rate. Radiat. Res. 2025, 204, 467–476, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rødland, G.E.; Temelie, M.; Eek Mariampillai, A.; Hauge, S.; Gilbert, A.; Chevalier, F.; Savu, D.I.; Syljuåsen, R.G. Potential Benefits of Combining Proton or Carbon Ion Therapy with DNA Damage Repair Inhibitors. Cells 2024, 13, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, T.S.A.; McNamara, A.L.; Appelt, A.; Haviland, J.S.; Sørensen, B.S.; Troost, E.G.C. A systematic review of clinical studies on variable proton Relative Biological Effectiveness (RBE). Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 175, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Timmermann, B. Paediatric proton therapy. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganetti, H.; Niemierko, A.; Ancukiewicz, M.; Gerweck, L.E.; Goitein, M.; Loeffler, J.S.; Suit, H.D. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) values for proton beam therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2002, 53, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, A.; Fournier, C. High-LET charged particles: Radiobiology and application for new approaches in radiotherapy. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2023, 199, 1225–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasino, F.; Durante, M. Proton radiobiology. Cancers 2015, 7, 353–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbacz, M.; Gajewski, J.; Durante, M.; Kisielewicz, K.; Krah, N.; Kopec, R.; Olko, P.; Patera, V.; Rinaldi, I.; Rydygier, M.; et al. Quantification of biological range uncertainties in patients treated at the Krakow proton therapy centre. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, B.S.; Pawelke, J.; Bauer, J.; Burnet, N.G.; Dasu, A.; Hoyer, M.; Karger, C.P.; Krause, M.; Schwarz, M.; Underwood, T.S.A.; et al. Does the uncertainty in relative biological effectiveness affect patient treatment in proton therapy? Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 163, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemskerk, T.; van de Kamp, G.; Rovituso, M.; Kanaar, R.; Essers, J. Enhanced radiosensitivity of head and neck cancer cells to proton therapy via hyperthermia-induced homologous recombination deficiency. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2025, 51, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemskerk, T.; Groenendijk, C.; Rovituso, M.; van der Wal, E.; van Burik, W.; Chatzipapas, K.; Lathouwers, D.; Kanaar, R.; Brown, J.M.C.; Essers, J. Position in proton Bragg curve influences DNA damage complexity and survival in head and neck cancer cells. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2025, 51, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniewind, I.; Hadiwikarta, W.W.; Grajek, J.; Poleszczuk, J.; Richter, S.; Peitzsch, M.; Müller, J.; Klusa, D.; Beyreuther, E.; Löck, S.; et al. Cellular plasticity upon proton irradiation determines tumor cell radiosensitivity. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willers, H.; Allen, A.; Grosshans, D.; McMahon, S.J.; von Neubeck, C.; Wiese, C.; Vikram, B. Toward A variable RBE for proton beam therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 128, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleei, R. Modelling Dsb Repair Kinetics for DNA Damage Induced by Proton and Carbon Ions. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2019, 183, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohberger, B.; Glänzer, D.; Eck, N.; Kerschbaum-Gruber, S.; Mara, E.; Deycmar, S.; Madl, T.; Kashofer, K.; Georg, P.; Leithner, A.; et al. Activation of efficient DNA repair mechanisms after photon and proton irradiation of human chondrosarcoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, E.; Mladenova, V.; Stuschke, M.; Iliakis, G. New Facets of DNA Double Strand Break Repair: Radiation Dose as Key Determinant of HR versus c-NHEJ Engagement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolo, I.; Altmeyer, M.; Legube, G.; Mekhail, K. Nuclear and genome dynamics underlying DNA double-strand break repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccaldi, R.; Cejka, P. Mechanisms and regulation of DNA end resection in the maintenance of genome stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymonowicz, K.; Krysztofiak, A.; Linden, J.V.; Kern, A.; Deycmar, S.; Oeck, S.; Squire, A.; Koska, B.; Hlouschek, J.; Vullings, M.; et al. Proton Irradiation Increases the Necessity for Homologous Recombination Repair Along with the Indispensability of Non-Homologous End Joining. Cells 2020, 9, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deycmar, S.; Pruschy, M. Combined Treatment Modalities for High-Energy Proton Irradiation: Exploiting Specific DNA Repair Dependencies. Int. J. Part. Ther. 2018, 5, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.O.; Augsburger, M.A.; Grosse, N.; Guckenberger, M.; Lomax, A.J.; Sartori, A.A.; Pruschy, M.N. Differential DNA repair pathway choice in cancer cells after proton- and photon-irradiation. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 116, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosse, N.; Fontana, A.O.; Hug, E.B.; Lomax, A.; Coray, A.; Augsburger, M.; Paganetti, H.; Sartori, A.A.; Pruschy, M. Deficiency in Homologous Recombination Renders Mammalian Cells More Sensitive to Proton Versus Photon Irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014, 88, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliakis, G.; Mladenova, V.; Sharif, M.; Chaudhary, S.; Mavragani, I.V.; Soni, A.; Saha, J.; Schipler, A.; Mladenov, E. Defined Biological Models of High-Let Radiation Lesions. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2019, 183, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenova, V.; Mladenov, E.; Chaudhary, S.; Stuschke, M.; Iliakis, G. The high toxicity of DSB-clusters modelling high-LET-DNA damage derives from inhibition of c-NHEJ and promotion of alt-EJ and SSA despite increases in HR. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1016951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeck, S.; Szymonowicz, K.; Wiel, G.; Krysztofiak, A.; Lambert, J.; Koska, B.; Iliakis, G.; Timmermann, B.; Jendrossek, V. Relating Linear Energy Transfer to the Formation and Resolution of DNA Repair Foci After Irradiation with Equal Doses of X-ray Photons, Plateau, or Bragg-Peak Protons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, E.; Staudt, C.; Soni, A.; Murmann-Konda, T.; Siemann-Loekes, M.; Iliakis, G. Strong suppression of gene conversion with increasing DNA double-strand break load delimited by 53BP1 and RAD52. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 1905–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Lamerdin, J.E.; Tebbs, R.S.; Schild, D.; Tucker, J.D.; Shen, M.R.; Brookman, K.W.; Siciliano, M.J.; Walter, C.A.; Fan, W.; et al. XRCC2 and XRCC3, new human Rad51-family members, promote chromosome stability and protect against DNA cross-links and other damages. Mol. Cell 1998, 1, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errami, A.; He, D.M.; Friedl, A.A.; Overkamp, W.J.I.; Morolli, B.; Hendrickson, E.A.; Eckardt-Schupp, F.; Oshimura, M.; Lohman, P.H.M.; Jackson, S.P.; et al. XR-C1, a new CHO cell mutant which is defective in DNA-PKcs, is impaired in both V(D)J coding and signal joint formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 3146–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, A.; Mladenov, E.; Iliakis, G. Proficiency in homologous recombination repair is prerequisite for activation of G2-checkpoint at low radiation doses. DNA Repair 2021, 101, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Bencsik-Theilen, A.; Mladenov, E.; Jakob, B.; Taucher-Scholz, G.; Iliakis, G. Reduced contribution of thermally labile sugar lesions to DNA double strand break formation after exposure to heavy ions. Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacker, J.; Stretch, A. Responses of 4 X-ray-sensitive CHO cell mutants to different radiations and to irradiation conditions promoting cellular recovery. Mutat. Res. 1985, 146, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadley, J.D.; Whitlock, J.L.; Rotmensch, J.; Atcher, R.W.; Tang, J.; Schwartz, J.L. The effects of radon daughter alpha-particle irradiation in K1 and xrs-5 CHO cell lines. Mutat. Res. 1991, 248, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zyuzikov, N.A.; Prise, K.M.; Zdzienicka, M.Z.; Newman, H.C.; Michael, B.D.; Trott, K.R. The relationship between the RBE of alpha particles and the radiosensitivity of different mutations of Chinese hamster cells. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2001, 40, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.A.; Herdman, M.T.; Stevens, D.L.; Jones, N.J.; Thacker, J.; Goodhead, D.T. Relative Sensitivities of Repair-Deficient Mammalian Cells for Clonogenic Survival after a-Particle Irradiation. Radiat. Res. 2004, 162, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrather, W.K.; Ritter, S.; Scholz, M.; Kraft, G. RBE for carbon track-segment irradiation in cell lines of differing repair capacity. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1999, 75, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, S.J.; Flint, D.B.; Chakraborty, S.; McFadden, C.H.; Yoon, D.S.; Bronk, L.; Titt, U.; Mohan, R.; Grosshans, D.R.; Sumazin, P.; et al. Nonhomologous End Joining Is More Important Than Proton Linear Energy Transfer in Dictating Cell Death. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 105, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Huang, J. DNA End Resection: Facts and Mechanisms. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2016, 14, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Howard, M.E.; Tu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Denbeigh, J.M.; Remmes, N.B.; Herman, M.G.; Beltran, C.J.; Yuan, J.; Greipp, P.T.; et al. Inhibition of ATM induces hypersensitivity to proton irradiation by upregulating toxic end joining. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 3333–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, E.; Fan, X.; Dueva, R.; Soni, A.; Iliakis, G. Radiation-dose-dependent functional synergisms between ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs in checkpoint control and resection in G2-phase. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurm, F.M.; Hacker, D. First CHO genome. Nat. Biotech. 2011, 29, 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vcelar, S.; Melcher, M.; Auer, N.; Hrdina, A.; Puklowski, A.; Leisch, F.; Jadhav, V.; Wenger, T.; Baumann, M.; Borth, N. Changes in Chromosome Counts and Patterns in CHO Cell Lines upon Generation of Recombinant Cell Lines and Subcloning. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, e1700495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostek, C.; Turner, E.L.; Robbins, M.; Rightnar, S.; Xiao, W.; Obenaus, A.; Harkness, T.A.A. Involvement of homologous recombination repair after proton-induced DNA damage. Mutagenesis 2008, 23, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panek, A.; Miszczyk, J. ATM and RAD51 Repair Pathways in Human Lymphocytes Irradiated with 70 MeV Therapeutic Proton Beam. Radiat. Res. 2022, 197, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deycmar, S.; Mara, E.; Kerschbaum-Gruber, S.; Waller, V.; Georg, D.; Pruschy, M. Ganetespib selectively sensitizes cancer cells for proximal and distal spread-out Bragg peak proton irradiation. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipler, A.; Mladenova, V.; Soni, A.; Nikolov, V.; Saha, J.; Mladenov, E.; Iliakis, G. Chromosome thripsis by DNA double strand break clusters causes enhanced cell lethality, chromosomal translocations and 53BP1-recruitment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7673–7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliakis, G.; Mladenov, E.; Mladenova, V. Necessities in the Processing of DNA Double Strand Breaks and Their Effects on Genomic Instability and Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mladenov, E.; Pressler, M.; Mladenova, V.; Soni, A.; Li, F.; Heinzelmann, F.; Esser, J.N.; Hessenow, R.; Gkika, E.; Jendrossek, V.; et al. Evidence for Quasi-High-LET Biological Effects in Clinical Proton Beams That Suppress c-NHEJ and Enhance HR and Alt-EJ. Cells 2026, 15, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010086

Mladenov E, Pressler M, Mladenova V, Soni A, Li F, Heinzelmann F, Esser JN, Hessenow R, Gkika E, Jendrossek V, et al. Evidence for Quasi-High-LET Biological Effects in Clinical Proton Beams That Suppress c-NHEJ and Enhance HR and Alt-EJ. Cells. 2026; 15(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleMladenov, Emil, Mina Pressler, Veronika Mladenova, Aashish Soni, Fanghua Li, Feline Heinzelmann, Johannes Niklas Esser, Razan Hessenow, Eleni Gkika, Verena Jendrossek, and et al. 2026. "Evidence for Quasi-High-LET Biological Effects in Clinical Proton Beams That Suppress c-NHEJ and Enhance HR and Alt-EJ" Cells 15, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010086

APA StyleMladenov, E., Pressler, M., Mladenova, V., Soni, A., Li, F., Heinzelmann, F., Esser, J. N., Hessenow, R., Gkika, E., Jendrossek, V., Timmermann, B., Stuschke, M., & Iliakis, G. (2026). Evidence for Quasi-High-LET Biological Effects in Clinical Proton Beams That Suppress c-NHEJ and Enhance HR and Alt-EJ. Cells, 15(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010086