MicroRNAs in Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies: Early Detection, Prognosis, and Treatment Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

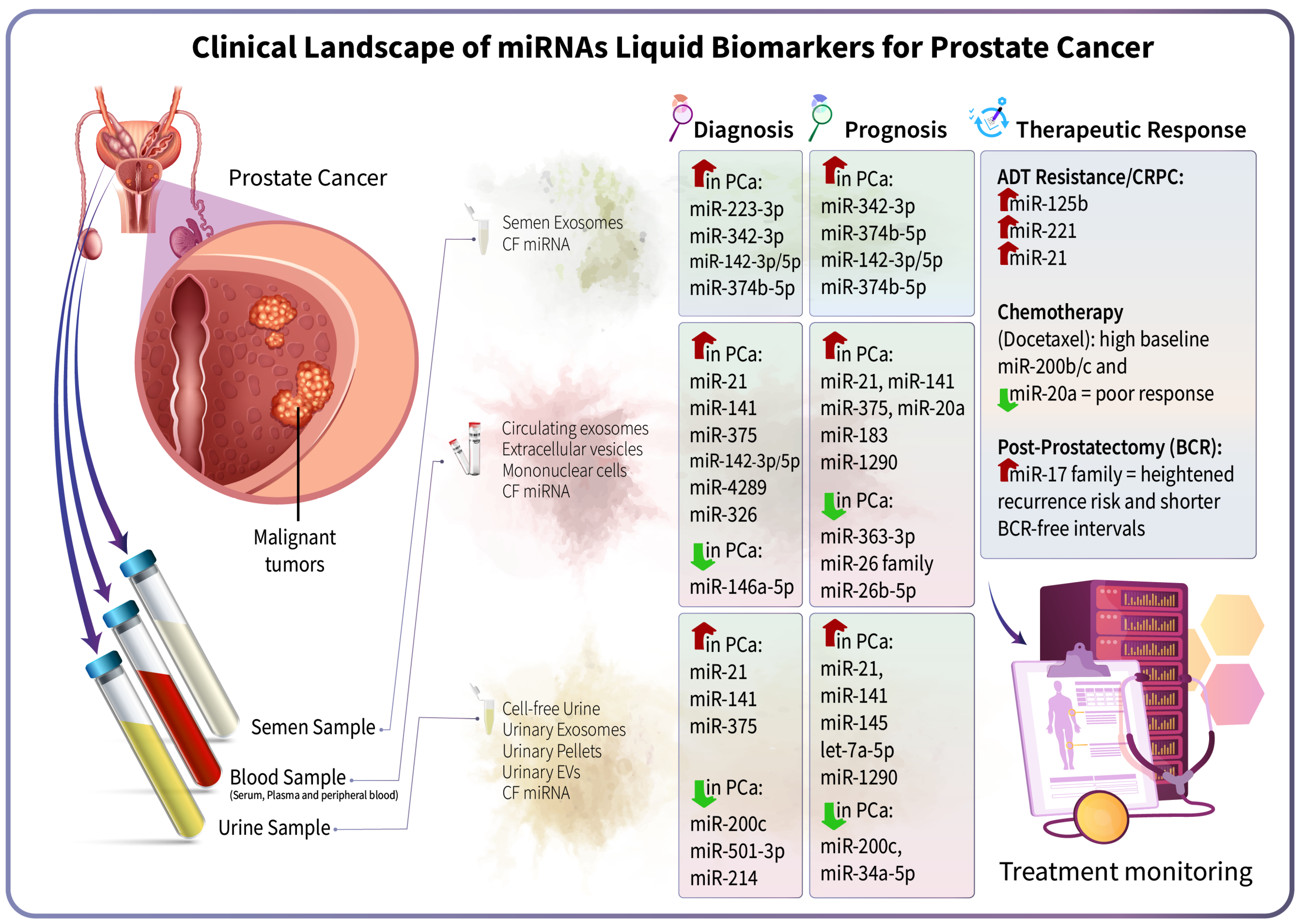

2. miRNAs in Early Detection of PCa

2.1. miRNAs in Blood Samples

2.2. miRNAs in Urine Samples

2.3. miRNAs in Semen and Other Biofluids

3. miRNAs as Prognostic Biomarkers in PCa

3.1. MiRNAs and Tumor Aggressiveness

3.2. MiRNAs and Metastasis/Poor Outcome

4. miRNAs for Treatment Monitoring and Therapeutic Response

4.1. MiRNA Dynamics with Systemic Therapy

4.2. Markers of Treatment Resistance

4.3. miRNAs as Predictive and Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers

5. Limitations and Specificity Considerations of Circulating miRNAs in PCa

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADT | Androgen-Deprivation Therapy |

| AR | Androgen Receptor |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BCR | Biochemical Recurrence |

| BPH | Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia |

| CAF | Cancer-Associated Fibroblast |

| CAPRA | Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment |

| CRPC | Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer |

| CTC | Circulating Tumor Cell |

| ctDNA | Circulating Tumor DNA |

| DDR | DNA Damage Repair |

| DRE | Digital Rectal Examination |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| EV | Extracellular Vesicle |

| GS | Gleason Score |

| HRPC | Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer |

| MET | Mesenchymal–Epithelial Transition |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| mCRPC | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PCa | Prostate Cancer |

| PBMC | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| PSMA | Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SEV | Small Extracellular Vesicle |

| TRUS | Transrectal Ultrasound |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VHR | Very High-Risk |

References

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Ebell, M.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kemper, A.R.; et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 1901–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, L.; Young, S.; Natarajan, S. MRI-ultrasound fusion for guidance of targeted prostate biopsy. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2013, 23, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, F.; Jeet, V.; Moya, L.; Selth, L.A.; Chambers, S.; Clements, J.A.; Batra, J. A Plasma Biomarker Panel of Four MicroRNAs for the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, D.; Çoban, S.; Çalışkan, A.; Şenoğlu, Y.; Kayıkçı, M.A.; Tekin, A. Optimizing Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: A Prospective, Randomized Comparison of 12-core vs. 20-core Biopsy for Detection Accuracy and Upgrading Risk. J. Urol. Surg. 2025, 12, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.D.; Chevillet, J.R.; Kroh, E.M.; Ruf, I.K.; Pritchard, C.C.; Gibson, D.F.; Mitchell, P.S.; Bennett, C.F.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Stirewalt, D.L.; et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5003–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Espinosa, I.; Serrato, J.A.; Cabello-Gutiérrez, C.; Carlos-Reyes, Á.; Ortiz-Quintero, B. Exosome-Derived miRNAs in Liquid Biopsy for Lung Cancer. Life 2024, 14, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, K.C.; Palmisano, B.T.; Shoucri, B.M.; Shamburek, R.D.; Remaley, A.T. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchinovich, A.; Weiz, L.; Langheinz, A.; Burwinkel, B. Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 7223–7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Lupold, S.E. MicroRNA expression and function in prostate cancer: A review of current knowledge and opportunities for discovery. Asian J. Androl. 2016, 18, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosland, M.C. Prostate cancer in low- and middle-income countries—Challenges and opportunities. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2025, 28, 743–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, L.; Meijer, J.; Schubert, S.; Matin, F.; Batra, J. Assessment of miR-98-5p, miR-152-3p, miR-326 and miR-4289 Expression as Biomarker for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinay, I.; Tan, M.; Gui, B.; Werner, L.; Kibel, A.S.; Jia, L. Functional roles and potential clinical application of miRNA-345-5p in prostate cancer. Prostate 2018, 78, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larne, O.; Östling, P.; Haflidadóttir, B.S.; Hagman, Z.; Aakula, A.; Kohonen, P.; Kallioniemi, O.; Edsjö, A.; Bjartell, A.; Lilja, H.; et al. miR-183 in prostate cancer cells positively regulates synthesis and serum levels of prostate-specific antigen. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.G.; Zhao, J.F.; Xiao, L.; Rao, W.Y.; Ran, C.; Xiao, Y.H. MicroRNA-19a-3p suppresses invasion and metastasis of prostate cancer via inhibiting SOX4. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 6245–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahdal, M.; Perera, R.A.; Moschovas, M.C.; Patel, V.; Perera, R.J. Current advances of liquid biopsies in prostate cancer: Molecular biomarkers. Mol. Ther.—Oncolytics 2023, 30, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foj, L.; Ferrer, F.; Serra, M.; Arevalo, A.; Gavagnach, M.; Gimenez, N.; Filella, X. Exosomal and Non-Exosomal Urinary miRNAs in Prostate Cancer Detection and Prognosis. Prostate 2017, 77, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.T.; Campos, R.; Trashin, S.; Daems, E.; Carneiro, D.; Fraga, A.; Ribeiro, R.; De Wael, K. Singlet oxygen-based photoelectrochemical detection of miRNAs in prostate cancer patients’ plasma: A novel diagnostic tool for liquid biopsy. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 158, 108698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pinheiro, P.; Ramalho-Carvalho, J.; Vieira, F.Q.; Torres-Ferreira, J.; Oliveira, J.; Gonçalves, C.S.; Costa, B.M.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C. MicroRNA-375 plays a dual role in prostate carcinogenesis. Clin. Epigenetics 2015, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Huang, Y.; Niu, X.; Tao, T.; Jiang, L.; Tong, N.; Chen, S.; Liu, N.; Zhu, W.; Chen, M. Hsa-miR-146a-5p modulates androgen-independent prostate cancer cells apoptosis by targeting ROCK1. Prostate 2015, 75, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ding, M.; Su, Y.; Cui, D.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, S.; Jia, G.; Wang, X.; Ruan, Y.; et al. Loss of exosomal miR-146a-5p from cancer-associated fibroblasts after androgen deprivation therapy contributes to prostate cancer metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrijević, Z.; Stevanović, J.; Šunderić, M.; Penezić, A.; Miljuš, G.; Danilović Luković, J.; Janjić, F.; Matijašević Joković, S.; Brkušanin, M.; Savić-Pavićević, D.; et al. Diagnostic properties of miR-146a-5p from liquid biopsies in prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 262, 155522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avasthi, K.K.; Choi, J.W.; Glushko, T.; Manley, B.J.; Yu, A.; Park, J.Y.; Brown, J.S.; Pow-Sang, J.; Gantenby, R.; Wang, L.; et al. Extracellular Microvesicle MicroRNAs and Imaging Metrics Improve the Detection of Aggressive Prostate Cancer: A Pilot Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qin, S.; An, T.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, L. MiR-145 detection in urinary extracellular vesicles increase diagnostic efficiency of prostate cancer based on hydrostatic filtration dialysis method. Prostate 2017, 77, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Zhong, B.-L.; Wang, X.-J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H. MicroRNA-145 inhibits cell migration and invasion and regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by targeting connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2016, 22, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.; Pawlowski, T.; Catto, J.; Marsden, G.; Vessella, R.; Rhees, B.; Kuslich, C.; Visakorpi, T.; Hamdy, F. Changes in circulating microRNA levels associated with prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selth, L.A.; Das, R.; Townley, S.L.; Coutinho, I.; Hanson, A.R.; Centenera, M.M.; Stylianou, N.; Sweeney, K.; Soekmadji, C.; Jovanovic, L. A ZEB1-miR-375-YAP1 pathway regulates epithelial plasticity in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.H.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Cui, P.G.; Liu, S.B.; Xu, Z.Y. MicroRNA-21 regulates the ERK/NF-κB signaling pathway to affect the proliferation, migration, and apoptosis of human melanoma A375 cells by targeting SPRY1, PDCD4, and PTEN. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzeniewski, N.; Tosev, G.; Pahernik, S.; Hadaschik, B.; Hohenfellner, M.; Duensing, S. Identification of cell-free microRNAs in the urine of patients with prostate cancer. In Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 16.e17–16.e22. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, K.; Fujita, K.; Tomiyama, E.; Hatano, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Wang, C.; Ishizuya, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Kato, T. MiR-30b-3p and miR-126-3p of urinary extracellular vesicles could be new biomarkers for prostate cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2021, 10, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, M.; Bajo-Santos, C.; Hessvik, N.P.; Lorenz, S.; Fromm, B.; Berge, V.; Sandvig, K.; Line, A.; Llorente, A. Identification of non-invasive miRNAs biomarkers for prostate cancer by deep sequencing analysis of urinary exosomes. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danarto, R.; Astuti, I.; Umbas, R.; Haryana, S.M. Urine miR-21-5p and miR-200c-3p as potential non-invasive biomarkers in patients with prostate cancer. Turk. J. Urol. 2019, 46, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Wu, L.; Zhao, J.C.; Jin, H.-J.; Yu, J. TMPRSS2–ERG gene fusions induce prostate tumorigenesis by modulating microRNA miR-200c. Oncogene 2014, 33, 5183–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiecki, R.; Popławski, P.; Sys, D.; Bogusławska, J.; Białas, A.; Zawadzki, M.; Piekiełko-Witkowska, A.; Dobruch, J. CIRCULATING miR-1-3p, miR-96-5p, miR-148a-3p, and miR-375-3p Support Differentiation Between Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostate Lesions. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2025, 23, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Yang, Y.; He, H.; Xiong, Y.; Zhong, M.; Wang, S.; Xia, Q. Integrating multi-cohort machine learning and clinical sample validation to explore peripheral blood mRNA diagnostic biomarkers for prostate cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plas, S.; Melchior, F.; Aigner, G.P.; Frantzi, M.; Pencik, J.; Kafka, M.; Heidegger, I. The impact of urine biomarkers for prostate cancer detection–A systematic state of the art review. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2025, 210, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, M.; Castells, M.; Bassas, L.; Vigués, F.; Larriba, S. Semen miRNAs contained in exosomes as non-invasive biomarkers for prostate cancer diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, T.; Hisamori, S.; Hogan, D.J.; Zabala, M.; Hendrickson, D.G.; Dalerba, P.; Cai, S.; Scheeren, F.; Kuo, A.H.; Sikandar, S.S. miR-142 regulates the tumorigenicity of human breast cancer stem cells through the canonical WNT signaling pathway. eLife 2014, 3, e01977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Hruby, G.W.; McKiernan, J.M.; Gurvich, I.; Lipsky, M.J.; Benson, M.C.; Santella, R.M. Dysregulation of circulating microRNAs and prediction of aggressive prostate cancer. Prostate 2012, 72, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Jiang, Z.B.; Xu, S.R.; Zhou, Z.H.; He, R.L. Increased serum levels of miR-214 in patients with PCa with bone metastasis may serve as a potential biomarker by targeting PTEN. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yuan, T.; Liang, M.; Du, M.; Xia, S.; Dittmar, R.; Wang, D.; See, W.; Costello, B.A.; Quevedo, F.; et al. Exosomal miR-1290 and miR-375 as prognostic markers in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldessari, C.; Pipitone, S.; Molinaro, E.; Cerma, K.; Fanelli, M.; Nasso, C.; Oltrecolli, M.; Pirola, M.; D’Agostino, E.; Pugliese, G.; et al. Bone Metastases and Health in Prostate Cancer: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications. Cancers 2023, 15, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Sánchez, M.V.; Picazo-Martínez, M.G.; Giménez-Bachs, J.M.; Donate-Moreno, M.J.; Navarro Jiménez, S.; Tárraga-Honrubia, M.A.; Salinas-Sánchez, A.S. Total quantification of circulating microRNAs and smallRNAs in plasma and urine as prognostic biomarkers in prostate cancer. Actas Urológicas Españolas (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 49, 501861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Castro, E.; Fizazi, K.; Heidenreich, A.; Ost, P.; Procopio, G.; Tombal, B.; Gillessen, S. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, N.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; De Santis, M.; Fanti, S.; Fossati, N.; Gandaglia, G.; Gillessen, S.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2020 Update. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, C.; Bernardino, R.M.; Fleshner, N.E. The natural history of prostate cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2025, 19, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brase, J.C.; Johannes, M.; Schlomm, T.; Fälth, M.; Haese, A.; Steuber, T.; Beissbarth, T.; Kuner, R.; Sültmann, H. Circulating miRNAs are correlated with tumor progression in prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, R.; Heukamp, L.C.; Rogenhofer, S.; von Ruecker, A.; Muller, S.C.; Ellinger, J. Circulating microRNAs (miRNA) in serum of patients with prostate cancer. Urology 2011, 77, 1265.e9–1265.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochetti, G.; Poli, G.; Guelfi, G.; Boni, A.; Egidi, M.G.; Mearini, E. Different levels of serum microRNAs in prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia: Evaluation of potential diagnostic and prognostic role. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 7545–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zaman, M.S.; Deng, G.; Majid, S.; Saini, S.; Liu, J.; Tanaka, Y.; Dahiya, R. MicroRNAs 221/222 and genistein-mediated regulation of ARHI tumor suppressor gene in prostate cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Thayanithy, V.; Subramanian, S.; Oberg, A.L.; Cunningham, J.M.; Cerhan, J.R.; Steer, C.J.; Thibodeau, S.N. Gene networks and microRNAs implicated in aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 9490–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpal, M.; Ell, B.J.; Buffa, F.M.; Ibrahim, T.; Blanco, M.A.; Celià-Terrassa, T.; Mercatali, L.; Khan, Z.; Goodarzi, H.; Hua, Y.; et al. Direct targeting of Sec23a by miR-200s influences cancer cell secretome and promotes metastatic colonization. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-M.; Castillo, L.; Mahon, K.; Chiam, K.; Lee, B.Y.; Nguyen, Q.; Boyer, M.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Pavlakis, N.; Marx, G. Circulating microRNAs are associated with docetaxel chemotherapy outcome in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 2462–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasan, A.H.; Scott, A.W.; Wu, J.J.; Feng, G.; Meeks, J.J.; Thaxton, C.S.; Mirkin, C.A. Circulating microRNA signature for the diagnosis of very high-risk prostate cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10655–10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Yang, L.F.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, X.D.; Zhang, S.L.; Dai, B.; Zhu, Y.P.; Shen, Y.J.; Shi, G.H.; Ye, D.W. Serum miRNA-21: Elevated levels in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer and potential predictive factor for the efficacy of docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Prostate 2011, 71, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Liu, M.; Fang, W.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. MiR-139-5p is Increased in the Peripheral Blood of Patients with Prostate Cancer. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 39, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Kang, X.L.; Cen, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. High-Level Expression of microRNA-21 in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Is a Diagnostic and Prognostic Marker in Prostate Cancer. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2015, 19, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, N.; Chavarriaga, J.; Ayala, P.; Pedraza, A.; Bolivar, J.; Prada, J.G.; Cataño, J.G.; García-Perdomo, H.A.; Villanueva, J.; Varela, D.; et al. MicroRNAs as Potential Liquid Biopsy Biomarker for Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Res. Rep. Urol. 2022, 14, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoey, C.; Ahmed, M.; Fotouhi Ghiam, A.; Vesprini, D.; Huang, X.; Commisso, K.; Commisso, A.; Ray, J.; Fokas, E.; Loblaw, D.A.; et al. Circulating miRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers to predict aggressive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Wang, F.; Su, P.; Han, J.; Song, Z.; Fei, Y. Prognostic implications of tissue and serum levels of microRNA-128 in human prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 8394–8401. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, C.; Rani, S.; O’Driscoll, L. miR-34a is an intracellular and exosomal predictive biomarker for response to docetaxel with clinical relevance to prostate cancer progression. Prostate 2014, 74, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, Z.; Ning, H.; Zhang, K.; Pan, D.; Ding, K.; Huang, W.; Kang, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. MicroRNA-21 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells as a novel biomarker in the diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2016, 17, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Chen, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, F.; Huang, S.; Tang, Y.; Yang, C.; Ding, W.; Ren, D.; et al. Decreased miR-218-5p Levels as a Serum Biomarker in Bone Metastasis of Prostate Cancer. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2019, 42, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.X.; Dong, B.; Du, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Gao, W.Q.; Xue, W. Discovery of extracellular vesicles derived miR-181a-5p in patient’s serum as an indicator for bone-metastatic prostate cancer. Theranostics 2021, 11, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Rivera, J.; De la Rosa Pérez, D.A.; Olvera, S.I.N.; Figueroa-Angulo, E.E.; Saucedo, J.G.C.; Hernández-León, O.; Alvarez-Sánchez, M.E. The Circulating miR-107 as a Potential Biomarker Up-Regulated in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Noncoding RNA 2024, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Aguayo, V.; Sáez-Martínez, P.; Jiménez-Vacas, J.M.; Moreno-Montilla, M.T.; Montero-Hidalgo, A.J.; Pérez-Gómez, J.M.; López-Canovas, J.L.; Porcel-Pastrana, F.; Carrasco-Valiente, J.; Anglada, F.J.; et al. Dysregulation of the miRNome unveils a crosstalk between obesity and prostate cancer: miR-107 asa personalized diagnostic and therapeutic tool. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramprasad, K.; Siddappa, M.N.; Siddaiah, M.C.; Moorthy, M.; Ramaswamy, G. Circulating microRNAs as biomarker in prostate cancer and their significance in the differentiation of benign and malignant conditions of the prostate. Urol. Ann. 2025, 17, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.; Nan, A.; Li, R.; Ding, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, B.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, L.; et al. A novel biochip-based liquid biopsy for extracellular vesicle RNA detection in prostate cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2025, 26, 2593744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagirath, D.; Yang, T.L.; Bucay, N.; Sekhon, K.; Majid, S.; Shahryari, V.; Dahiya, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Saini, S. microRNA-1246 Is an Exosomal Biomarker for Aggressive Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hong, J.; Kim, J.W.; Lim, S.; Choi, S.C.; Gim, J.A.; Kang, S.G.; Noh, T.I.; Park, K.H. Investigating miR-6880-5p in extracellular vesicle from plasma as a prognostic biomarker in endocrine therapy-treated castration-resistant prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Bi, X.; Shayiti, F.; Niu, Y.; Chen, P. Relationship between circulating miRNA-222-3p and miRNA-136-5p and the efficacy of docetaxel chemotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredsøe, J.; Rasmussen, A.K.I.; Thomsen, A.R.; Mouritzen, P.; Høyer, S.; Borre, M.; Ørntoft, T.F.; Sørensen, K.D. Diagnostic and Prognostic MicroRNA Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer in Cell-free Urine. Eur. Urol. Focus 2018, 4, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Park, Y.H.; Jung, S.H.; Jang, S.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Chung, Y.J. Urinary exosome microRNA signatures as a noninvasive prognostic biomarker for prostate cancer. npj Genom. Med. 2021, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, R.; Nguyen, C.; Lorch, R.; Chakrabarti, R. MicroRNA expressions associated with progression of prostate cancer cells to antiandrogen therapy resistance. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoshenko, M.Y.; Bryzgunova, O.E.; Laktionov, P.P. miRNAs and androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Rev. Cancer 2021, 1876, 188625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Xie, W.; Yang, M.; Hsieh, C.L.; Drouin, S.; Lee, G.S.; Kantoff, P.W. Expression differences of circulating microRNAs in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer and low-risk, localized prostate cancer. Prostate 2013, 73, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmusvaara, S.; Erkkilä, T.; Urbanucci, A.; Jalava, S.; Seppälä, J.; Kaipia, A.; Kujala, P.; Lähdesmäki, H.; Tammela, T.L.J.; Visakorpi, T. Goserelin and bicalutamide treatments alter the expression of microRNAs in the prostate. Prostate 2013, 73, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Huang, W.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Kong, Z.; Li, T.; Wu, H.; Jing, F.; Li, Y. Androgen-induced miR-27A acted as a tumor suppressor by targeting MAP2K4 and mediated prostate cancer progression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 79, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Yang, M.; Chen, S.; Balk, S.; Pomerantz, M.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Brown, M.; Lee, G.-S.M.; Kantoff, P.W. The altered expression of MiR-221/-222 and MiR-23b/-27b is associated with the development of human castration resistant prostate cancer. Prostate 2012, 72, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnau, C.G.H.; Fussek, S.; Smit, F.P.; Aalders, T.W.; van Hooij, O.; Pinto, P.M.C.; Burchardt, M.; Schalken, J.A.; Verhaegh, G.W. Upregulation of miR-3195, miR-3687 and miR-4417 is associated with castration-resistant prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 3789–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, C.; Linxweiler, J.; Schmucker, P.; Snaebjornsson, M.T.; Schmitz, W.; Wach, S.; Krebs, M.; Hartmann, E.; Puhr, M.; Müller, A.; et al. MiR-205-driven downregulation of cholesterol biosynthesis through SQLE-inhibition identifies therapeutic vulnerability in aggressive prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazova, A.; Samakova, A.; Laczo, E.; Hamar, D.; Polakovicova, M.; Jurikova, M.; Kyselovic, J. Clinical utility of miRNA-1, miRNA-29g and miRNA-133s plasma levels in prostate cancer patients with high-intensity training after androgen-deprivation therapy. Physiol. Res. 2019, 68, S139–s147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobrega, M.; Reis, M.B.D.; Souza, M.F.; Furini, H.H.; Costa Brandão Berti, F.; Souza, I.L.M.; Mingorance Carvalho, T.; Zanata, S.M.; Fuganti, P.E.; Malheiros, D.; et al. Comparative analysis of extracellular vesicles miRNAs (EV-miRNAs) and cell-free microRNAs (cf-miRNAs) reveals that EV-miRNAs are more promising as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for prostate cancer. Gene 2025, 939, 149186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Rivera, J.; Nuñez-Olvera, S.I.; Fernández-Sánchez, V.; Cureño-Díaz, M.A.; Gómez-Zamora, E.; Plascencia-Nieto, E.S.; Figueroa-Angulo, E.E.; Alvarez-Sánchez, M.E. miRNA Signatures as Predictors of Therapy Response in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Insights from Clinical Liquid Biopsies and 3D Culture Models. Genes 2025, 16, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, E.; Pashaei, E.; Ahmady, M.; Ozen, M.; Aydin, N. Meta-analysis of miRNA expression profiles for prostate cancer recurrence following radical prostatectomy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendler, A.; Jung, M.; Stephan, C.; Honey, R.J.; Stewart, R.J.; Pace, K.T.; Erbersdobler, A.; Samaan, S.; Jung, K.; Yousef, G.M. miRNAs can predict prostate cancer biochemical relapse and are involved in tumor progression. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 39, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Jung, M.; Mollenkopf, H.J.; Wagner, I.; Stephan, C.; Jentzmik, F.; Miller, K.; Lein, M.; Kristiansen, G.; Jung, K. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of microRNA profiling in prostate carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Qian, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Combinations of elevated tissue miRNA-17-92 cluster expression and serum prostate-specific antigen as potential diagnostic biomarkers for prostate cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 6943–6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberts, C.; Annala, M.; Sipola, J.; Ng, S.W.S.; Chen, X.E.; Nurminen, A.; Korhonen, O.V.; Munzur, A.D.; Beja, K.; Schönlau, E.; et al. Deep whole-genome ctDNA chronology of treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Nature 2022, 608, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, R.; Raymond, G.; Krishnan, S.; Tzou, K.S.; Baxi, S.; Ram, M.R.; Govind, S.K.; Chandramoorthy, H.C.; Abu-Khzam, F.N.; Shaw, P. Clinical Theragnostic Potential of Diverse miRNA Expressions in Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Ikeda, K.; Sato, W.; Horie-Inoue, K.; Okamoto, K.; Inoue, S. MicroRNA Library-Based Functional Screening Identified Androgen-Sensitive miR-216a as a Player in Bicalutamide Resistance in Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.F.d.; Kuasne, H.; Barros-Filho, M.d.C.; Cilião, H.L.; Marchi, F.A.; Fuganti, P.E.; Paschoal, A.R.; Rogatto, S.R.; Cólus, I.M.d.S. Circulating mRNAs and miRNAs as candidate markers for the diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltran, H.; Romanel, A.; Conteduca, V.; Casiraghi, N.; Sigouros, M.; Franceschini, G.M.; Orlando, F.; Fedrizzi, T.; Ku, S.-Y.; Dann, E.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA profile recognizes transformation to castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Liu, S.; Ma, L.; Cheng, L.; Li, Q.; Qing, L.; Yang, Y.; Dong, Z. Identification of miRNA signature in cancer-associated fibroblast to predict recurrent prostate cancer. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 180, 108989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabegina, L.; Nazarova, I.; Nikiforova, N.; Slyusarenko, M.; Sidina, E.; Knyazeva, M.; Tsyrlina, E.; Novikov, S.; Reva, S.; Malek, A. A New Approach for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis by miRNA Profiling of Prostate-Derived Plasma Small Extracellular Vesicles. Cells 2021, 10, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| miRNA | Liquid Biopsy | Target | Sources | Diagnostic Role | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-9-3p | Serum (blood) | Not specified | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Increases in PCa | [14] |

| miR-19a-3p | Blood | SOX4; EMT regulators (MMP2, MMP9, N-cadherin, Vimentin, α-SMA, E-cadherin) | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Tumor-suppressive function; reduces invasion and EMT | [16] |

| miR-21 | Urinary pellets, urinary exosomes | PTEN, PDCD4, SPRY1; AR signaling; EMT pathways | Pellets and exosomes | Increases in non-metastatic and metastatic PCa | [18,29,32] |

| miR-34a-5p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary exosomes | Decreases in PCa | [32] |

| miR-92a-1-5p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary exosomes | Decreases in PCa | [32] |

| miR-98-5p | Plasma (blood) | Not specified | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Increases in PCa; relatively PCa-specific; possible prognostic relevance | [13] |

| miR-126-3p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary EVs | Increases; significant early detection biomarker; better performance than PSA | [31] |

| miR-1290 | Urine | Not specified | Urinary EVs | Increases, higher in metastatic PCa | [25] |

| miR-141 | Urine pellets/EVs | Not specified | Urinary pellets and EVs | Increases; correlates with the Gleason score | [11,12,18] |

| miR-142-3p/5p | Semen | APC → Wnt/β-catenin pathway | Semen exosomes | Increases; improves PSA specificity in PCa vs. BPH | [38] |

| miR-143-3p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary exosomes | Decreases in PCa | [38] |

| miR-145 | Urine | FSCN1; EMT regulators | Urinary EVs/exosomes | Increases (especially GS ≥ 8); improves PSA diagnostic performance | [26,40] |

| miR-146a-5p | CAF-EVs | ROCK/Caspase-3; EGFR/ERK pathways | Tissue and CAF-derived exosomes | Decreases in high GS and metastatic PCa | [21,22] |

| miR-152-3p | Plasma (blood) | Not specified | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Increases as part of the diagnostic 4-miRNA plasma panel | [13] |

| miR-183 | Blood/tissue | PSA 3′UTR (direct regulation of PSA expression) | Prostate tissue and circulation | Increases; correlates with PSA, higher grade, and progression | [15] |

| miR-196a-5p | Urine | ERG, HOX genes | Urinary exosomes | Decreases; high sensitivity for distinguishing PCa from normal tissue. | [32] |

| miR-200c | Urine | EMT suppression pathways | Cell-free urine | Decreases in PCa | [33,34] |

| miR-214 | Urine | Not specified | Urinary exosomes | Decreases in PCa | [18,41] |

| miR-223-3p | Semen | TP53, FOXO1, CDK2, IGF1R, MDM2, CHUK, HSP90B1 | Semen exosomes | Increases; discriminates PCa from controls | [38] |

| miR-326 | Plasma (blood) | HOTAIR-regulated tumor-suppressive pathways | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Increases in plasma; tissue downregulation; linked to disease progression | [13] |

| miR-330-3p | Serum (blood) | Not specified | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Increases in PCa | [14] |

| miR-342-3p | Semen | IGF1R, E2F1, ATF4, IKBKG | Semen exosomes | Increases; predicts GS ≥ 7 with PSA | [38] |

| miR-345-5p | Serum (blood) | Not specified | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Increases; diagnostic and treatment response candidate | [14] |

| miR-374b-5p | Semen | Not specified | Semen exosomes | Increased; predicts GS ≥ 7 | [38] |

| miR-375 | Blood, urine | CCND2; ZEB1/miR-375/YAP1 signaling axis | Tissue, circulating miRNA, urinary EVs | Increases; associated with GS, stage, and metastasis; strong diagnostic performance | [20,28,42] |

| miR-4289 | Plasma (blood) | Not specified | Cell-free circulating miRNA | Increases as part of the diagnostic plasma panel | [13] |

| miR-483-5p | Urine | Angiogenesis and metastasis pathways | Cell-free urine fraction | Increased; enhances diagnostic performance with PSA | [30] |

| miR-501-3p | Urine | ERG, HOX genes | Urinary exosomes | Decreases in PCa | [32] |

| miR-574-3p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary EVs | Increases; improves multi-miRNA diagnostic panel | [27] |

| miRNA | Liquid Biopsy | Target | Sources | Diagnostic Role | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| let-7a-5p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary exosomal | Part of the tri-miRNA panel predicting biochemical recurrence | [73] |

| let-7i | Plasma/serum | Not specified | Cell-free | Decreases with increasing GS; discriminates low vs. high-risk disease | [49,75] |

| miR-17 | Serum | Not specified | Cell-free | Part of a four-miRNA panel associated with aggressive pathology and early recurrence | [60] |

| miR-18b-5p | Serum/plasma | Not specified | Cell-free | Decreases with increasing GS | [50] |

| miR-20a | Serum/plasma | E2F1 | Cell-free | Elevates in GS 7–10 and high CAPRA scores; identifies aggressive disease | [40] |

| miR-20b | Serum/plasma | Not specified | Cell-free | Component of recurrence and high-risk panels | [60] |

| miR-21 | Plasma, serum, PBMCs, urine exosomes | PTEN, TPM1, PDCD4 | Cell-free, PBMC, exosomal | Elevates in aggressive PCa, CRPC, recurrence, metastasis, and poor OS | [40,54,58,63,74] |

| miR-25-3p | Serum/plasma | Not specified | Cell-free | Reduces with increasing GS | [50] |

| miR-26a | Serum/plasma | EZH2 | Cell-free | Higher in low-risk disease; inverse correlation with malignancy | [50] |

| miR-26b-5p | Serum/plasma | EZH2 | Cell-free | Decreases with increasing GS; distinguishes pGS6/7 vs. pGS8 | [50,55] |

| miR-34a | Urine | Not specified | Cell-free | Reduces in metastatic disease; weak association with OS | [62] |

| miR-106a-5p | Serum/plasma | PI3K/AKT pathway | Cell-free | Reduces in high-risk Pca; included in recurrence panels | [50,55] |

| miR-107 | Plasma | Not specified | Cell-free | Upregulates in CRPC and stage IV; diagnostic adjunct to PSA | [66,67] |

| miR-1246 | Serum exosomes | Not specified | Exosomal | Elevates in LN-positive and aggressive disease | [70] |

| miR-125b-5p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary exosomal | Part of the tri-miRNA urinary recurrence panel | [73] |

| miR-128 | Serum & tissue | BMI1, E2F3, DCX, NTRK3 | Cell-free & tissue-derived | Decreases levels predict metastasis and reduced recurrence-free survival | [61,63] |

| miR-1290 | Plasma exosomes | Not specified | Exosomal | Elevates in CRPC; predicts poor OS | [42] |

| miR-135a | Serum | PI3K/AKT pathway | Cell-free | Component of validated VHR aggressive disease signature | [50,55] |

| miR-139-5p | Peripheral blood | Not specified | Cell-free | Associates with GS > 7, high PSA, and advanced pathological stage | [57] |

| miR-141 | Plasma/serum | Not specified | Cell-free | Elevates in high-grade and lymph node-positive disease | [42,48] |

| miR-145 | Plasma/serum | KIF23, CCNA2 | Cell-free | Increases in intermediate/high-risk D’Amico groups | [40,52] |

| miR-151-5p | Urine | Not specified | Urinary exosomal | Tri-miRNA panel component for biochemical recurrence | [73] |

| miR-181a-5p | Serum exosomes | Not specified | Exosomal | Elevates in bone-metastatic Pca; diagnostic marker | [65] |

| miR-200 family (miR-200c) | Plasma/serum | SEC23A | Cell-free | High levels predict metastatic colonization and poor OS in CRPC | [53,54] |

| miR-214 | Serum | PTEN | Cell-free | Increases in bone-metastatic and poorly differentiated Pca | [41] |

| miR-218-5p | Serum | Not specified | Cell-free | Reduces in bone metastasis; predicts shorter metastasis-free survival | [64] |

| miR-221 | Plasma/serum | p27Kip1, ARHI, DVL2 | Cell-free | OncomiR linked to invasion and aggressive disease | [40,51] |

| miR-331-3p | Blood | CDCA5 | Cell-free | Cell-cycle regulator; downregulation promotes aggressive behavior | [52] |

| miR-363-3p | Serum/plasma | Not specified | Cell-free | Reduces with rising pGS; high-risk prognostic biomarker | [50,55] |

| miR-375 | Plasma, serum, urine | CBX7, YAP1 | Cell-free & exosomal | Elevates in aggressive, metastatic, and CRPC disease; predicts poor OS | [18,42,48,53] |

| miR-433 | Serum | PI3K/AKT pathway | Cell-free | Part of VHR molecular signature | [50,55] |

| miR-451 | Urine exosomes | Not specified | Exosomal | Component of Pca-MRS metastasis/recurrence risk model | [74] |

| miR-605 | Serum | PI3K/AKT pathway | Cell-free | VHR disease signature biomarker | [50,55] |

| miR-636 | Urine exosomes | Not specified | Exosomal | Downregulates in metastatic-risk Pca-MRS model | [74] |

| miR-6880-5p | Plasma exosomes | Ras/MAPK/ErbB regulators | Exosomal | Suppressed in CRPC; tumor-suppressive prognostic biomarker | [71] |

| miR-855-3p | Peripheral blood | Not specified | Cell-free | Elevates in CRPC and progressive disease | [72] |

| miR-940 | Serum | MIEN1 | Cell-free | Elevates in GS ≥ 7; improves PSA diagnostic accuracy | [59] |

| miRNA Name | Source of Biopsy | Target of miR | Treatment Context | Change and Clinical Indication | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1 | Blood/plasma | Myogenic differentiation, Myogenic networks | ADT + resistance training, post prostatectomy | Upregulated, reflects improved lean mass and muscle regeneration during ADT, component of miRNA classifiers predicting BCR | [83,86] |

| miR-10b | Blood/plasma | Migration and metastasis pathways | Post-prostatectomy | Upregulated, independent early relapse marker | [87,88] |

| miR-17–92 cluster | Blood/plasma | MYC-regulated proliferation and apoptosis control | Post prostatectomy (BCR risk) | Upregulated, predicts shorter BCR-free survival | [89] |

| miR-20a | Blood/plasma | Immune differentiation and inflammatory chemoresistance | Chemotherapy (docetaxel) | Low or unchanged post-therapy, predicts poor PSA response and shorter OS | [54,60] |

| miR-21 | Blood/plasma | AR signaling, PI3K/AKT, VEGF pathways | ADT → CRPC | Upregulated, predicts ADT resistance and CRPC development | [76,79] |

| miR-23b | Blood/plasma | MAP2K4, EMT suppression | CRPC | Downregulated, loss associated with progression and therapy resistance | [76,79] |

| miR-27a | Blood/plasma | MAP2K4; AR/PI3K signaling | CRPC | Downregulated, de-repression of oncogenic signaling in advanced disease | [26,79] |

| miR-27b | Blood/plasma | MAP2K4, EMT suppression | CRPC | Downregulated, tumor-suppressive loss associated with CRPC | [76] |

| miR-29b | Blood/plasma | Myogenesis and metabolic regulation | ADT + resistance training | Upregulated, biomarker of beneficial metabolic adaptation | [83] |

| miR-92b | Blood/serum | Proliferation and invasion pathways | CRPC | Downregulated, indicator of aggressive transition to CRPC | [81] |

| miR-96 | Blood/plasma | Androgen and proliferative signaling | Post prostatectomy | Upregulated, correlates with higher Gleason score and BCR risk | [88] |

| miR-125A-5p | Blood/plasma | Proliferation and recurrence pathways | Post prostatectomy | Upregulated, predicts the probability of biochemical recurrence | [86] |

| miR-125b | Blood/plasma | AR signaling and anti-apoptotic pathways | ADT → CRPC | Upregulated, marker of resistance and castration resistance | [76] |

| miR-133a | Blood/plasma | Muscle regeneration signaling | ADT + resistance training | Upregulated, reflects functional muscle recovery | [83] |

| miR-133b | Blood/plasma | CAF-mediated tumor growth signaling | Post prostatectomy | Altered expression, incorporated into prognostic BCR models | [86] |

| miR-141 | Blood/serum | EMT and metastatic networks | ADT → mCRPC | Upregulated, marker of advanced disease and resistance | [75,76,77] |

| miR-146a-5p | Blood/plasma exosomes | EGFR/ERK and EMT regulation | ADT | Downregulated, loss promotes EMT-driven metastasis | [21,22] |

| miR-199a-3p | Blood/plasma | Morphogenesis and EMT regulation | Post prostatectomy | Upregulated, predictor of biochemical recurrence | [86] |

| miR-200b | Blood/plasma | SEC23A secretory pathway | Chemotherapy (docetaxel) | High baseline expression, predicts poor treatment response and shorter OS | [54] |

| miR-205 | Blood/serum | ZEB1-mediated EMT regulation | CRPC | Downregulated, associated with tumor progression | [81] |

| miR-221 | Blood/plasma | Androgen-independent growth signaling | ADT | Upregulated, correlates with castration resistance | [26,76,86] |

| miR-222 | Blood/plasma | KIT signaling and angiogenesis | Chemotherapy (docetaxel) | Decreased post therapy, indicates an unfavorable treatment response | [54] |

| miR-375 | Blood/serum | Neuroendocrine and survival pathways | ADT → mCRPC | Upregulated, early indicator of metastatic CRPC | [77] |

| miR-378 | Blood/plasma | Metabolic and survival signaling | ADT | Altered early, early detection of emerging resistance | [75,76] |

| miR-409-3p | Blood/plasma | EMT and metastatic regulators | ADT | Altered early, predictive of hormone-refractory transition | [75,76] |

| miR-449A | Blood/plasma | Cell cycle control pathways | Post prostatectomy | Differential expression, predictor of biochemical recurrence | [86] |

| miR-3195 | Blood/plasma | Migration and invasion signaling | CRPC | Upregulated, discriminates CRPC from localized PCa | [81] |

| miR-3687 | Blood/plasma | Migration and invasion signaling | CRPC | Upregulated, biomarker of late-stage disease progression | [81] |

| miR-4417 | Blood/plasma | Migration and invasion networks | CRPC | Upregulated, candidate biomarker of late-stage metastatic progression | [81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yaghoubi, S.M.; Zare, E.; Jafari Dargahlou, S.; Jafari, M.; Azimi, M.; Khoshnazar, M.; Shirjang, S.; Mansoori, B. MicroRNAs in Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies: Early Detection, Prognosis, and Treatment Monitoring. Cells 2026, 15, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010083

Yaghoubi SM, Zare E, Jafari Dargahlou S, Jafari M, Azimi M, Khoshnazar M, Shirjang S, Mansoori B. MicroRNAs in Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies: Early Detection, Prognosis, and Treatment Monitoring. Cells. 2026; 15(1):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010083

Chicago/Turabian StyleYaghoubi, Seyyed Mohammad, Erfan Zare, Sina Jafari Dargahlou, Maryam Jafari, Mahdiye Azimi, Maedeh Khoshnazar, Solmaz Shirjang, and Behzad Mansoori. 2026. "MicroRNAs in Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies: Early Detection, Prognosis, and Treatment Monitoring" Cells 15, no. 1: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010083

APA StyleYaghoubi, S. M., Zare, E., Jafari Dargahlou, S., Jafari, M., Azimi, M., Khoshnazar, M., Shirjang, S., & Mansoori, B. (2026). MicroRNAs in Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies: Early Detection, Prognosis, and Treatment Monitoring. Cells, 15(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010083