Nutritive Value of Silage from Two Genotypes of Sugarcane Associated with Calcium Oxide and Sodium Hydroxide as Chemical Additives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Treatments

2.2. Silage Production

2.3. Chemical Analysis and Degradability

2.4. Statistical Analysis and Calculations

3. Results

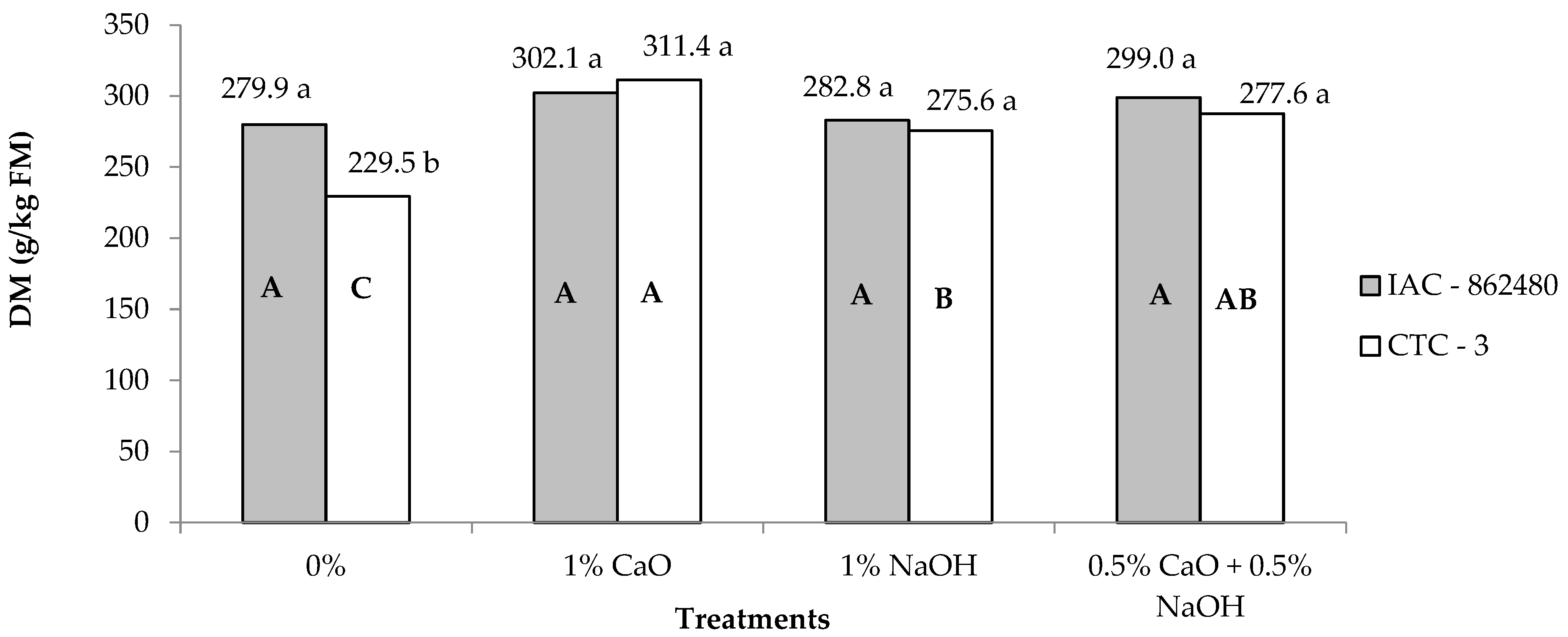

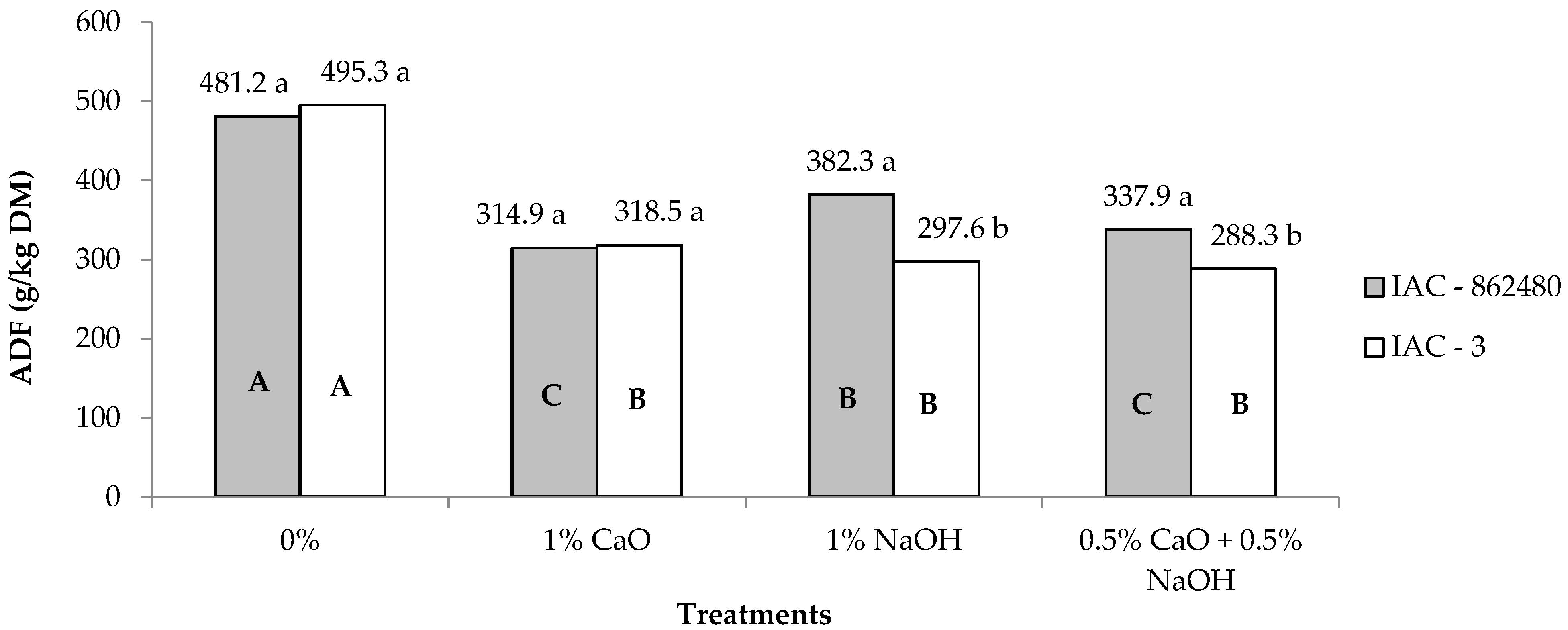

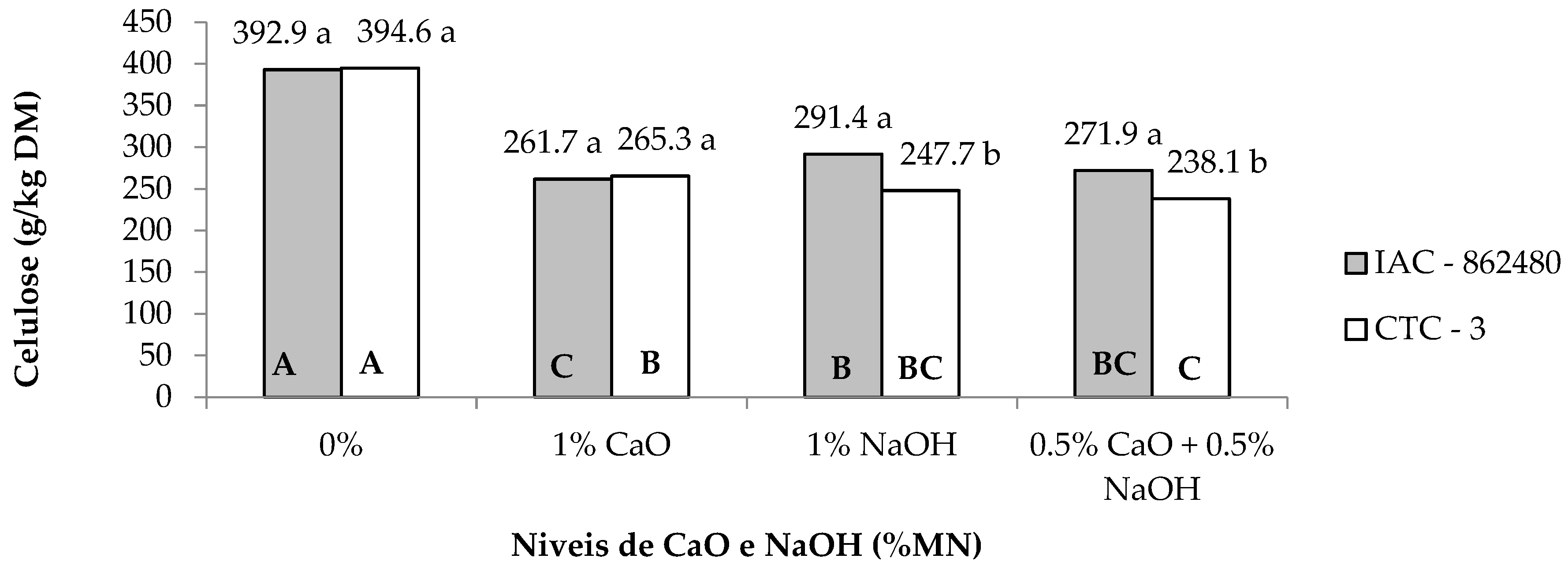

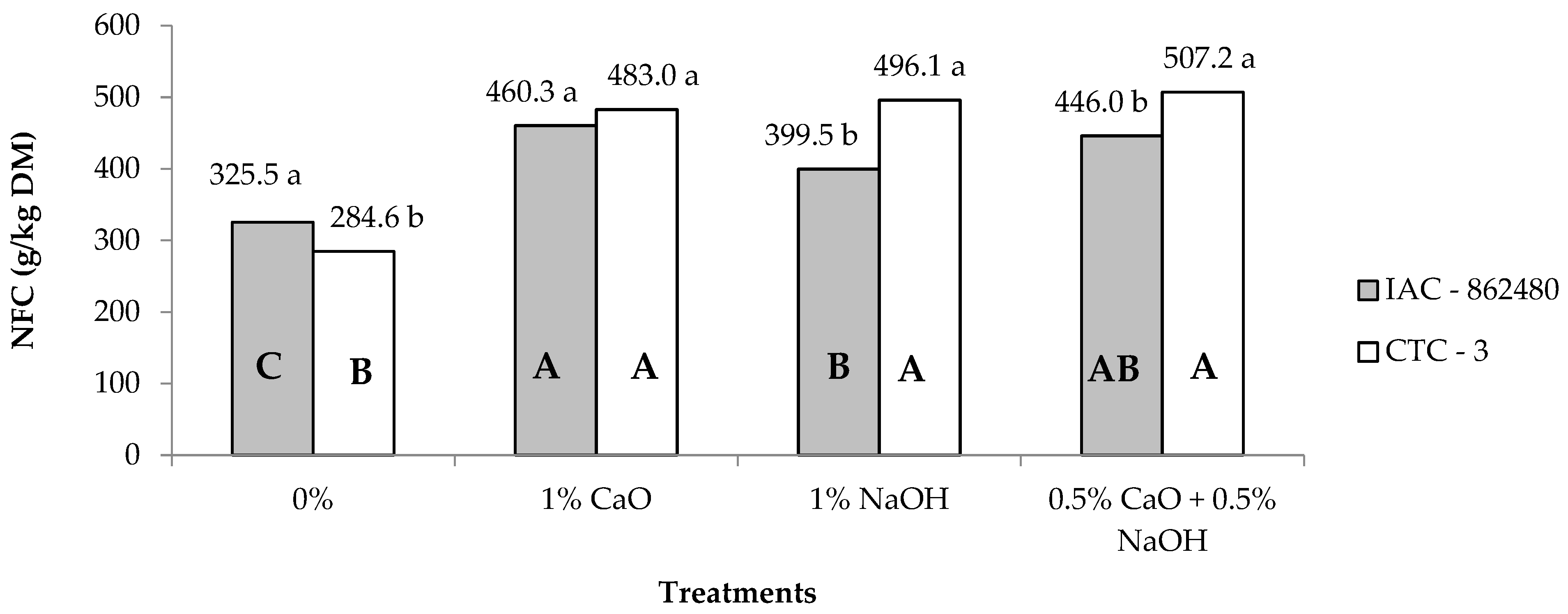

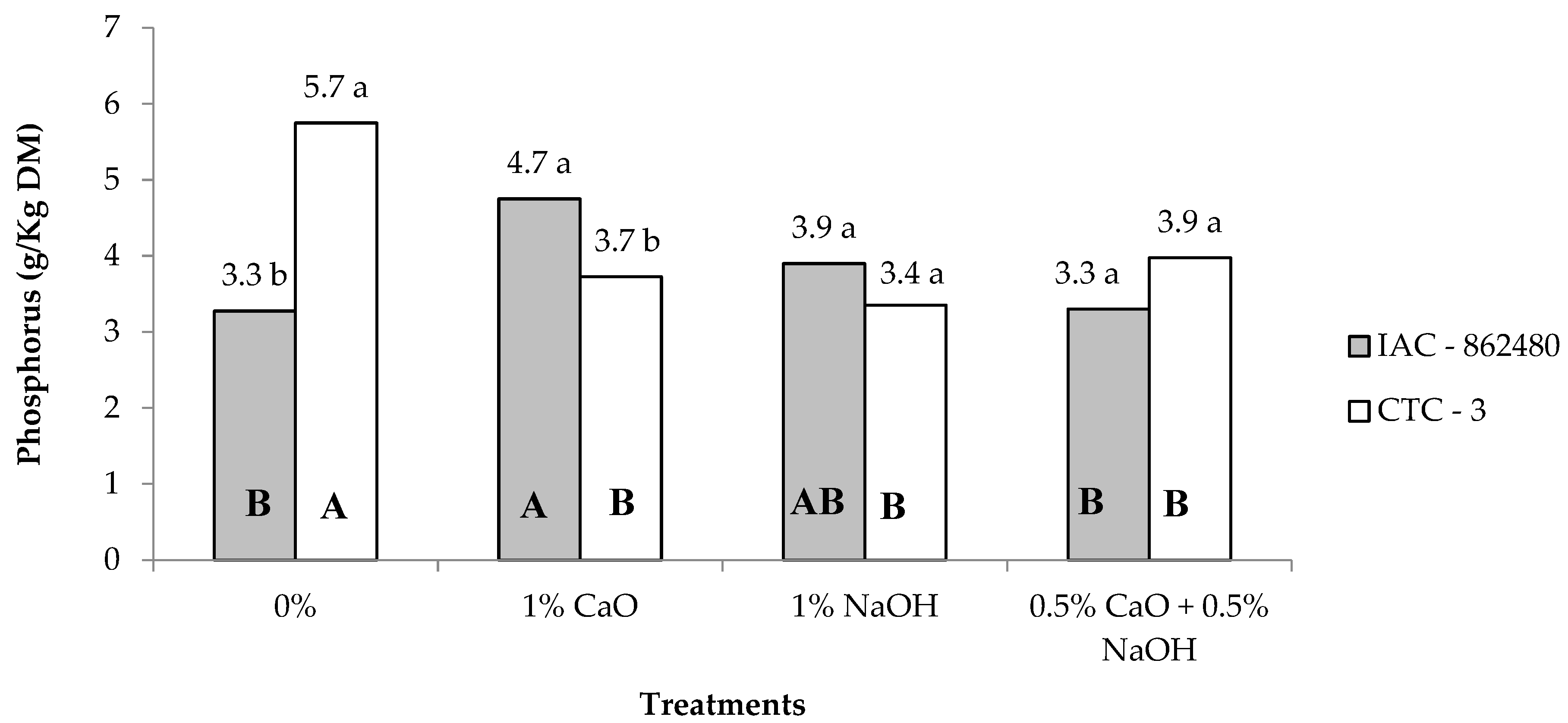

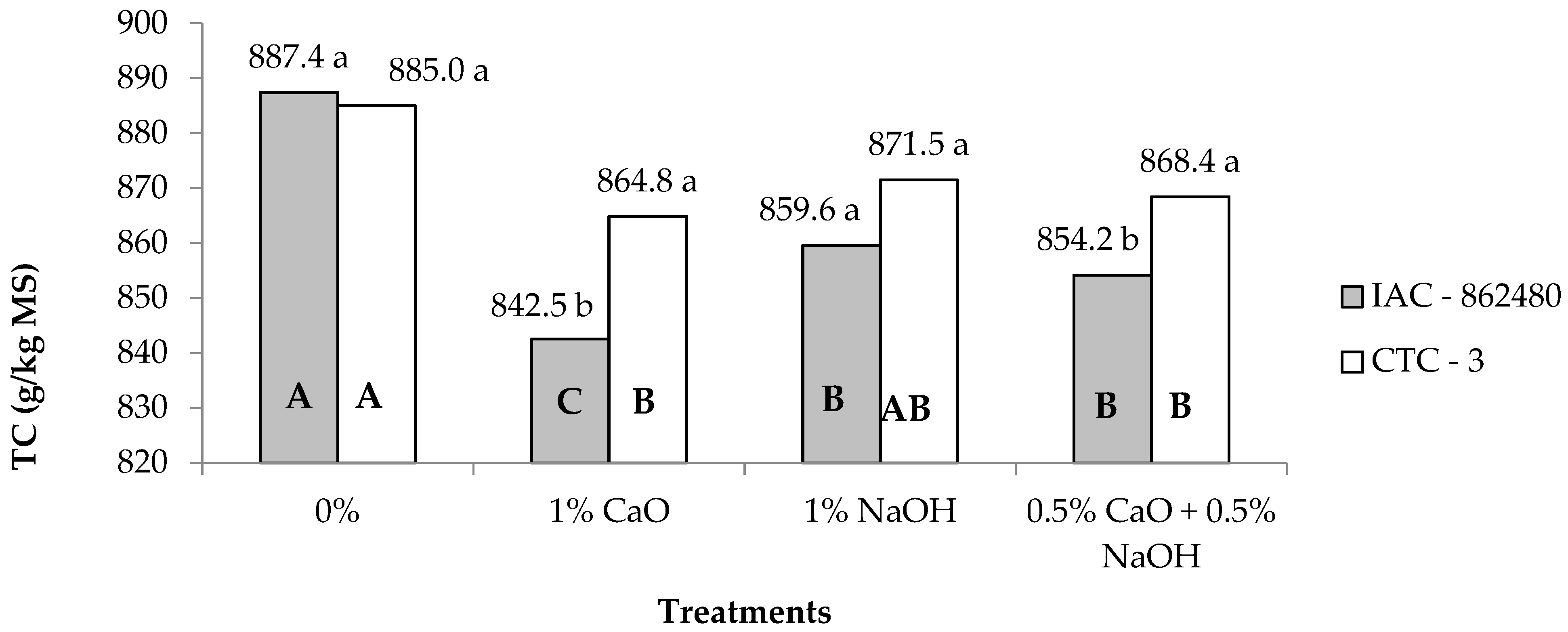

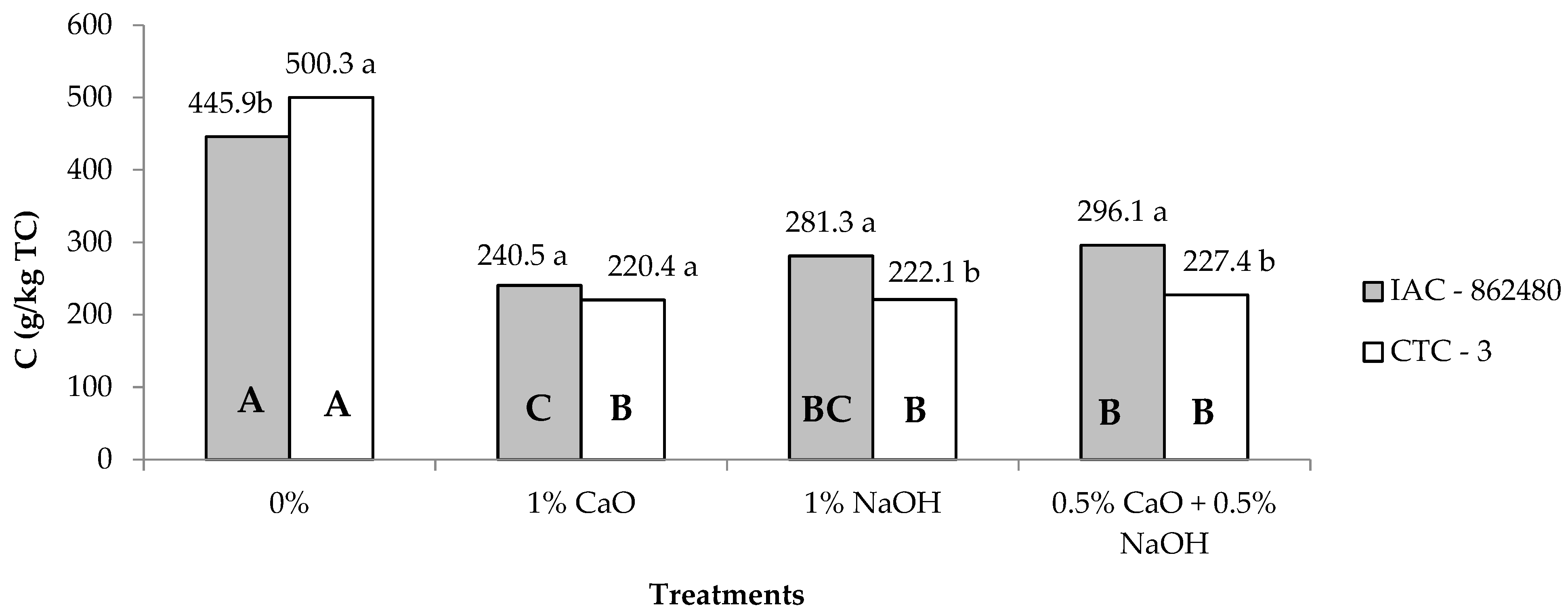

3.1. Chemical Composition of the Silages

3.2. Degradability Profile of the Silages

4. Discussion

4.1. Chemical Composition of the Silages

4.2. Degradability Profile of the Silages

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Sugar Annual: Brazil [S.l.]; 22 April 2025, Report Number: BR2025-0011; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Sugar%20Annual_Brasilia_Brazil_BR2025-0011.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Melo, P.L.; Cherubin, M.R.; Gomes, T.C.; Lisboa, I.P.; Satiro, L.S.P.; Cerri, C.E.; Siqueira-Neto, M. Straw removal effects on sugarcane root system and stalk yield. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.L.; Dall’Antonia, C.B.; Shiga, E.A.; Alvim, L.J.; Pessoni, R.A.B. Sugarcane bagasse as a source of carbon for enzyme production by filamentous fungi1. Hoehnea 2018, 45, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Jawaid, M.; Chandrasekar, M.; Senthilkumar, K.; Yadav, B.; Saba, N.; Siengchin, S. Sugarcane wastes into commercial products: Processing methods, production optimization and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, P.R.D.S.; Braga, A.L.F.; Ramos, E.M.C.; Oliveira, A.F.D.; Osadnik, C.R.; Ferreira, A.D.; Ramos, D. Effects of air pollution caused by sugarcane burning in Western São Paulo on the cardiovascular system. Rev. Saúde Pública 2017, 51, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, F.E.L.; Campos, A.G.; Domingues, R.C.; Santos, R.C.D.; Bezerra, V.C.R.; Gurgel, A.D.M. Fires in sugarcane cultivation and associated respiratory diseases in a municipality in Pernambuco. Saúde Debate 2025, 49, e9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B.F.; Ávila, C.L.S.; Pinto, J.C.; Schwan, R.F. Effect of propionic acid and Lactobacillus plantarum UFLA SIL 1 on the sugarcane silage with and without calcium oxide. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 7, 4159–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archimède, H.; Martin, C.; Périacarpin, F.; Rochette, Y.; Etienne, T.S.; Anais, C.; Doreau, M. Methane emission of Blackbelly rams consuming whole sugarcane forage compared with Dichanthium sp. Hay. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 190, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavian, M.; Ghorbani, G.R.; Rafiee, H.; Beauchemin, K.A. Substitution of wheat straw with sugarcane bagasse in low-forage diets fed to mid-lactation dairy cows: Milk production, digestibility, and chewing behavior. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 8034–8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadas, H.M.; Valadares Filho, S.C.; Silva, F.F.; Silva, F.A.S.; Pucetti, P.; Pacheco, M.V.C.; Silva, B.C.; Tedeschi, L.O. Effects of including physically effective fiber from sugarcane in whole corn grain diets on the ingestive, digestive, and ruminal parameters of growing beef bulls. Livest. Sci. 2021, 248, 104508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, C.O.; Carvalho, G.G.P.; Tosto, M.S.L.; Santos, S.A.; Pires, A.J.V.; Maranhão, C.M.A.; Rufino, L.M.A.; Correia, G.S.; de Oliveira, P.A. Nutritional profiles of three genotypes of sugarcane silage associated with calcium oxide. Grassl. Sci. 2018, 64, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.P.; Carvalho, B.F.; Ávila, C.L.S.; Júnior, G.S.D.; Pereira, M.N.; Schwan, R.F. Glycerin as an additive for sugarcane silage. Ann. Microbiol. 2014, 65, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.J.M.; Silva, A.V.; Silva, J.S.L.; Silva, J.F.; Silva, J.H.B.; Pereira Neto, F.; Borba, M.A.; Barreto, S.S.C.; Rodrigues, H.A.; Sousa, V.F.O.; et al. Sugarcane productivity and economic viability in response to planting density. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e279536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, N.R.D.; Fracarolli, J.A.; Junqueira, T.L.; Chagas, M.F.; Cardoso, T.F.; Watanabe, M.D.; Cavalett, O.; Venzke Filho, S.P.; Dale, B.E.; Bonomi, A.; et al. Sugarcane ethanol and beef cattle integration in Brazil. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 120, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordonal, R.D.O.; Carvalho, J.L.N.; Lal, R.; De Figueiredo, E.B.; De Oliveira, B.G.; La Scala Jr, N. Sustainability of sugarcane production in Brazil. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driehuis, F. Silage and the safety and quality of dairy foods: A review. Agric. Food Sci. 2013, 22, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, C.L.S.; Carvalho, B.F.; Pinto, J.C.; Duarte, W.F.; Schwan, R.F. The use of Lactobacillus species as starter cultures for enhancing the quality of sugar cane silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romão, C.O.; Tosto, M.S.L.; Santos, S.A.; Pires, A.J.V.; Ribeiro, O.L.; Maranhão, C.M.A.; Rufino, L.M.A.; Correia, G.S.; Alba, H.D.R.; Carvalho, G.G.P. Nutritive profile, digestibility, and carbohydrate fractionation of three sugarcane genotypes treated with calcium oxide. Agronomy 2023, 13, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.P.; Hartung, L.; Nunes, M.A.; Sobires, P.D.; Pereira, F.C.; Vargas, M.E.; Valle, T.A.; Campana, M. Calcium oxide reduces fermentation losses and improves the nutritional value of brewery-spent grain silage. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2025, 319, 116187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.; Martens, S.D.; Le Brech, Y.; Kervern, G.; Bayreuther, R.; Steinhöfel, O.; Zeyner, A. Physicochemical characterisation of barley straw treated with sodium hydroxide or urea and its digestibility and in vitro fermentability in ruminants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.; Rossi Junior, P.; Junges, D.; Dias, L.T.; Almeida, R.D.; Mari, L.J. New microbial additives on sugarcane ensilage: Bromatological composition, fermentative losses, volatile compounds and aerobic stability. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2011, 40, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC—Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists Inc.: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.R. Gravimetric determination of amylase-treated neutral detergent fiber in feeds with refluxing in beakers or crucibles: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2002, 85, 1217–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, H.K.; Van Soest, P.J. Forage Fiber Analysis; Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sniffen, C.J.; O’connor, J.D.; Van Soest, P.J.; Fox, D.G.; Russell, J.B. A net carbohydrate and protein system for evaluating cattle diets: II. Carbohydrate and protein availability. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 3562–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizsan, S.J.; Huhtanen, P. Effect of diet composition and incubation time on feed indigestible neutral detergent fiber concentration in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocek, J.E.; Russell, J. Protein and energy as an integrated system. Relationship of ruminal protein and carbohydrate availability to microbial synthesis and milk production. J. Dairy Sci. 1988, 71, 2070–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B. Challenges with nonfiber carbohydrate methods. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 81, 3226–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørskov, E.R.; McDonald, I. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 92, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.R.; Loften, J.R. The effect of starch on forage fiber digestion kinetics in vitro. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, C.; Yang, M.; Zang, L. Comparison of calcium oxide and calcium peroxide pretreatments of wheat straw for improving biohydrogen production. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 9151–9161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Ge, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Keener, H.; Li, Y. Comparison of sodium hydroxide and calcium hydroxide pretreatments of giant reed for enhanced enzymatic digestibility and methane production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Dai, R.; Chang, S.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, B. Antibacterial mechanism of biogenic calcium oxide and antibacterial activity of calcium oxide/polypropylene composites. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 650, 129446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.U.; Hussain, T.; Abdullah; Khan, M.A.; Almostafa, M.M.; Younis, N.S.; Yahya, G. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of Ficus carica-mediated calcium oxide (CaONPs) phyto-nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borreani, G.; Tabacco, E.; Schmidt, R.J.; Holmes, B.J.; Muck, R.A. Silage review: Factors affecting dry matter and quality losses in silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3952–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung Jr, L.; Shaver, R.D.; Grant, R.J.; Schmidt, R.J. Silage review: Interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4020–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, A.V.; Silveira Rabelo, C.H.; Andrade, L.P.; Silveira Rabelo, F.H.; Dos Santos, W.B. Characteristics of sugar cane in natura and hydrolyzed with lime in different storage times. Rev. Caatinga 2013, 26, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rabelo, C.H.S.; De Rezende, A.V.; Rabelo, F.H.S.; Nogueira, D.A.; Elias, R.F.; de Faria Júnior, D.C. Estabilidade aeróbia de cana-de-açúcar in natura hidrolisada com cal virgem. Braz. Anim. Sci. 2011, 12, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permata, D.A.; Kasim, A.; Alfi Asben, Y. Delignification of lignocellulosic biomass. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2021, 12, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorvash, M.; Kargar, S.; Yalchi, T.; Ghorbani, G.R. Effects of calcium oxide and calcium hydroxide on the chemical composition and in vitro digestibility of soybean straw. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2010, 8, 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, A.W.P.; Rocha, F.C.; Fagundes, J.L.; Fonseca, R.; Zonta, A. Evaluation of sugar cane with calcium hydroxide different levels. Bol. Ind. Anim. 2009, 66, 137–144. Available online: https://bia.iz.sp.gov.br/index.php/bia/article/view/1093 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Nadeem, M.; Ashgar, U.; Abbas, S.; Ullah, S.; Syed, Q. Alkaline pretreatment: A potential tool to explore kallar grass (Leptochloa fusca) as a substrate for bio-fuel production. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 18, 1133–1139. Available online: https://idosi.org/mejsr/mejsr18(8)13.htm (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Tan, X.; Zhuang, X.; Yuan, Z. Effect of sodium hydroxide pretreatment on physicochemical changes and enzymatic hydrolysis of herbaceous and woody lignocelluloses. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 112145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, D.A.; Oliveira, M.D.S.; Domingues, F.N.; Manzi, G.M.; Ferreira, D.S.; Santos, J. Hydrolysis of cane sugar with lime or hydrated lime. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2010, 39, 1186–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.P.; Yayen, J.; Chiou, T.J. Mobilization and recycling of intracellular phosphorus in response to availability. Quant. Plant Biol. 2025, 6, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, L.S.O.; Pires, A.J.V.; Carvalho, G.G.P.; Chagas, D.M.T. Dry matter and fiber fraction degradability of sugar cane treated with calcium oxide or sodium hydroxide. Rev. Bras. Saúde Prod. Anim. 2009, 10, 573–585. Available online: https://revbaianaenferm.ufba.br/index.php/rbspa/article/view/40002 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

| Item * | Genotype (G) | Additives (A) | SEM | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAC-862480 | CTC-3 | Without Additive | 1% CaO | 1% NaOH | 0.5%CaO + 0.5%NaOH | G | A | G × A | ||

| Dry matter 1 | 290.9 | 296.0 | 254.6C | 306.7A | 279.2B | 293.2AB | 2.36 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| OM 2 | 934.9 | 936.4 | 977.0A | 917.9C | 930.2B | 927.6B | 0.66 | 0.27 | <0.01 | 0.17 |

| Crude protein 2 | 52.4 | 49.1 | 59.0A | 45.9B | 51.1AB | 47.0B | 1.06 | 0.14 | <0.01 | 0.68 |

| Ether extract 2 | 21.6 | 16.1 | 21.8A | 19.6AB | 14.8B | 19.2AB | 0.66 | <0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| NDFa 2 | 459.8 | 438.2 | 575.6A | 408.4B | 421.7B | 390.4B | 4.67 | 0.02 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ADF 2 | 379.0 | 349.9 | 488.2A | 316.7B | 339.9B | 313.1B | 3.93 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Hemicellulose 2 | 73.9 | 79.7 | 92.8A | 65.3B | 77.8AB | 71.5B | 2.15 | 0.19 | <0.01 | 0.12 |

| Lignin 2 | 61.9 | 64.3 | 88.6A | 49.5B | 57.9B | 56.4B | 1.33 | 0.37 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cellulose 2 | 304.4 | 286.4 | 393.7A | 263.4B | 269.5B | 254.9B | 2.41 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| NFC 2 | 407.8 | 442.7 | 305.0B | 471.6A | 447.8A | 476.6A | 4.24 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| TDN 2 | 675.9 | 672.6 | 635.6B | 702.9A | 672.9A | 685.6A | 3.88 | 0.68 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Phosphorous | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| Calcium | 135.1 | 120.1 | 17.9C | 312.6A | 22.7C | 157.2B | 3.90 | 0.07 | <0.01 | 0.46 |

| TC 2 | 860.9 | 872.4 | 886.1A | 853.6C | 865.5B | 861.2AB | 1.48 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.05 |

| A + B1 3 | 474.9 | 508.2 | 344.0C | 552.4A | 516.7B | 553.1A | 4.52 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| B2 3 | 209.1 | 199.4 | 182.8B | 217.1AB | 232.0A | 185.1B | 4.66 | 0.31 | <0.01 | 0.18 |

| C 3 | 315.9 | 292.3 | 473.0A | 230.4B | 251.2B | 261.7B | 4.43 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Item | A (%) | B (%) | kd (g/h) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media | SEM | LI | LS | Media | SEM | LI | LS | Media | SEM | LI | LS | |

| IAC-862480 | ||||||||||||

| Without additive | 34.84 | 0.47 | 33.88 | 35.80 | 15.32 | 0.53 | 14.25 | 16.39 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 1% CaO | 34.79 | 0.78 | 33.22 | 36.37 | 15.96 | 0.88 | 14.18 | 17.74 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| 1% NaOH | 43.49 | 0.97 | 41.52 | 45.46 | 19.95 | 1.10 | 17.73 | 22.18 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| 0.5% CaO + 0.5% NaOH | 39.58 | 0.88 | 37.78 | 41.37 | 18.16 | 1.00 | 16.14 | 20.18 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| CTC-3 | ||||||||||||

| Without additive | 36.25 | 0.49 | 35.25 | 37.25 | 15.94 | 0.55 | 14.82 | 17.06 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 1% CaO | 36.20 | 0.81 | 34.56 | 37.83 | 16.61 | 0.91 | 14.76 | 18.46 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| 1% NaOH | 44.18 | 0.99 | 42.18 | 46.19 | 20.30 | 1.12 | 18.03 | 22.56 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| 0.5% CaO + 0.5% NaOH | 39.87 | 0.89 | 38.07 | 41.68 | 18.33 | 1.01 | 16.29 | 20.38 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Item | Lag (h) | B (%) | kd (g/h) | I (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media | SEM | LI | LS | Media | SEM | LI | LS | Media | SEM | LI | LS | Media | SEM | LI | LS | |

| IAC-862480 | ||||||||||||||||

| Without additive | 6.6 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 12.4 | 92.1 | 25.1 | 41.3 | 143 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 7.7 | 25.1 | −43.1 | 58.5 |

| 1% CaO | 6.9 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 9.4 | 53.0 | 1.9 | 49.1 | 56.9 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 46.6 | 1.9 | 42.8 | 50.5 |

| 1% NaOH | 7.0 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 9.1 | 50.8 | 1.3 | 48.3 | 53.4 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.022 | 48.8 | 1.2 | 46.5 | 51.3 |

| 0.5% CaO + 0.5% NaOH | 6.3 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 50.5 | 1.1 | 48.2 | 52.7 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.024 | 49.3 | 1 | 47.2 | 51.3 |

| CTC-3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Without additive | 6.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 12.3 | 90.2 | 24.5 | 40.4 | 140.1 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 9.5 | 24.5 | −40.2 | 59.3 |

| 1% CaO | 6.9 | 1.2 | 4.4 | 9.4 | 51.9 | 1.9 | 48.1 | 55.8 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 47.6 | 1.8 | 43.8 | 51.4 |

| 1% NaOH | 7.0 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 9.1 | 49.8 | 1.2 | 47.3 | 52.3 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.022 | 49.9 | 1.1 | 47.5 | 52.2 |

| 0.5% CaO + 0.5% NaOH | 6.3 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 49.4 | 1 | 47.2 | 51.6 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.018 | 0.024 | 50.2 | 0.9 | 48.2 | 52.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romão, C.d.O.; Tosto, M.S.L.; Santos, S.A.; Pires, A.J.V.; Ribeiro, O.L.; Maranhão, C.M.A.; Rufino, L.M.A.; Alba, H.D.R.; Correia, G.S.; de Carvalho, G.G.P. Nutritive Value of Silage from Two Genotypes of Sugarcane Associated with Calcium Oxide and Sodium Hydroxide as Chemical Additives. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2826. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122826

Romão CdO, Tosto MSL, Santos SA, Pires AJV, Ribeiro OL, Maranhão CMA, Rufino LMA, Alba HDR, Correia GS, de Carvalho GGP. Nutritive Value of Silage from Two Genotypes of Sugarcane Associated with Calcium Oxide and Sodium Hydroxide as Chemical Additives. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2826. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122826

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomão, Claudio de O., Manuela S. L. Tosto, Stefanie A. Santos, Aureliano J. V. Pires, Ossival L. Ribeiro, Camila M. A. Maranhão, Luana M. A. Rufino, Henry D. R. Alba, George S. Correia, and Gleidson G. P. de Carvalho. 2025. "Nutritive Value of Silage from Two Genotypes of Sugarcane Associated with Calcium Oxide and Sodium Hydroxide as Chemical Additives" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2826. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122826

APA StyleRomão, C. d. O., Tosto, M. S. L., Santos, S. A., Pires, A. J. V., Ribeiro, O. L., Maranhão, C. M. A., Rufino, L. M. A., Alba, H. D. R., Correia, G. S., & de Carvalho, G. G. P. (2025). Nutritive Value of Silage from Two Genotypes of Sugarcane Associated with Calcium Oxide and Sodium Hydroxide as Chemical Additives. Agronomy, 15(12), 2826. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122826