Effect of Treated Wastewater Quality on Agronomic Performance, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Properties of Water Used in This Study

2.3. Measured Parameters

2.3.1. Soil Analysis

2.3.2. Agro-Morphological Parameters

2.3.3. Physiological and Biochemical Parameters

2.3.4. Yield Parameters and Fruit Quality

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

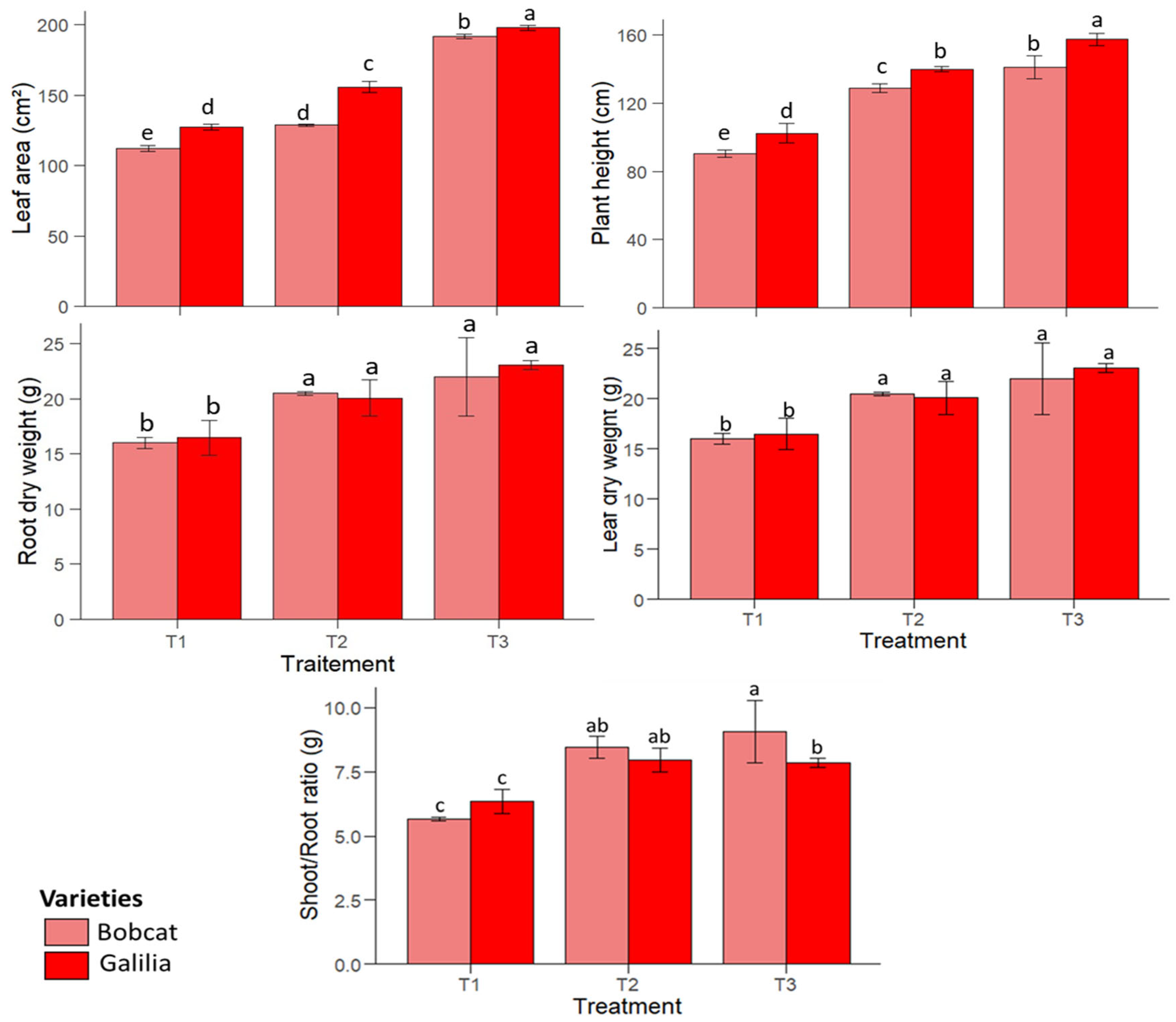

3.1. Agro-Morphological Parameter

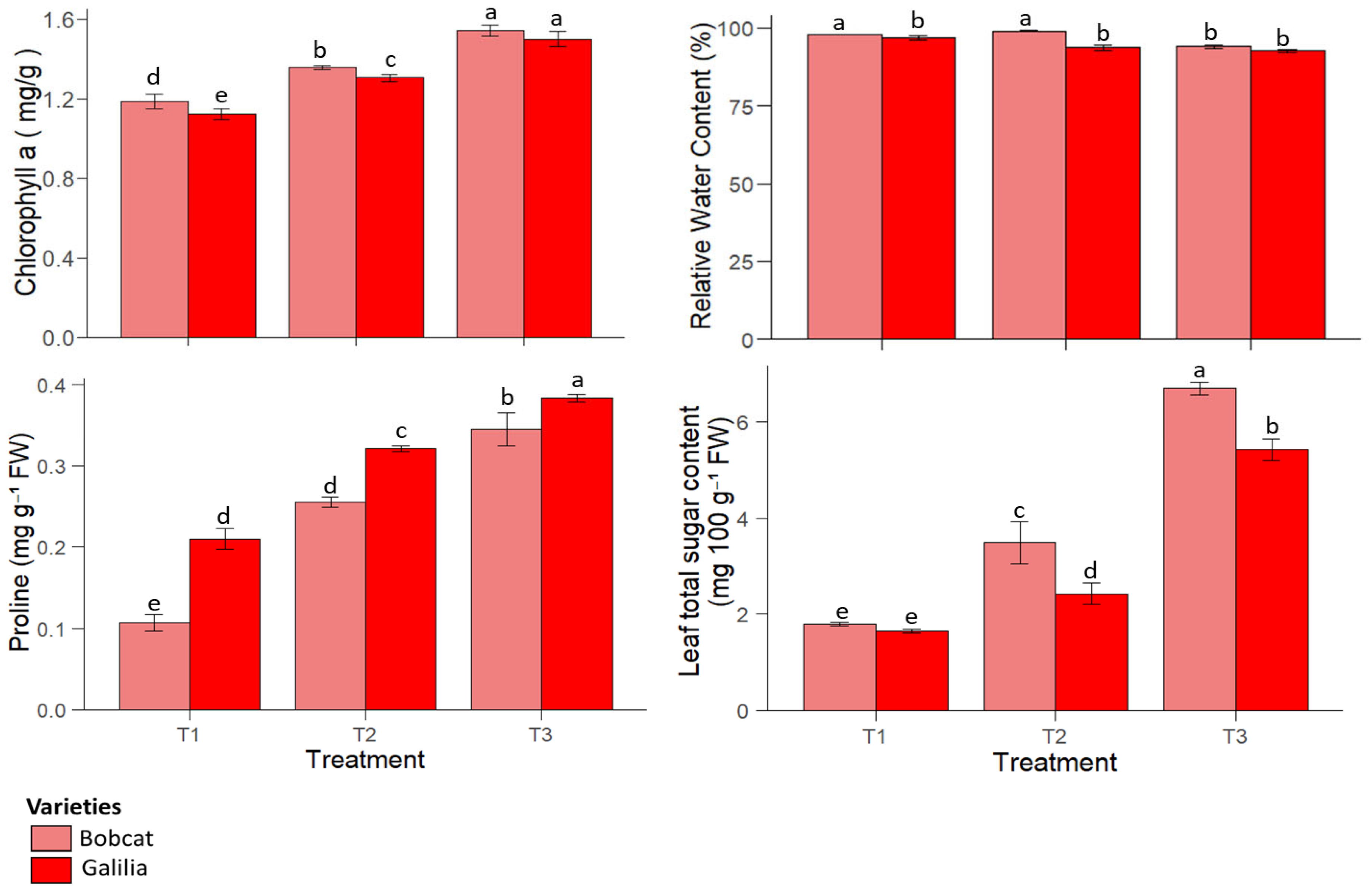

3.2. Physiological and Biochemical Parameters

3.3. Yield and Fruit Quality Parameters

3.3.1. Fruit Yield Parameters

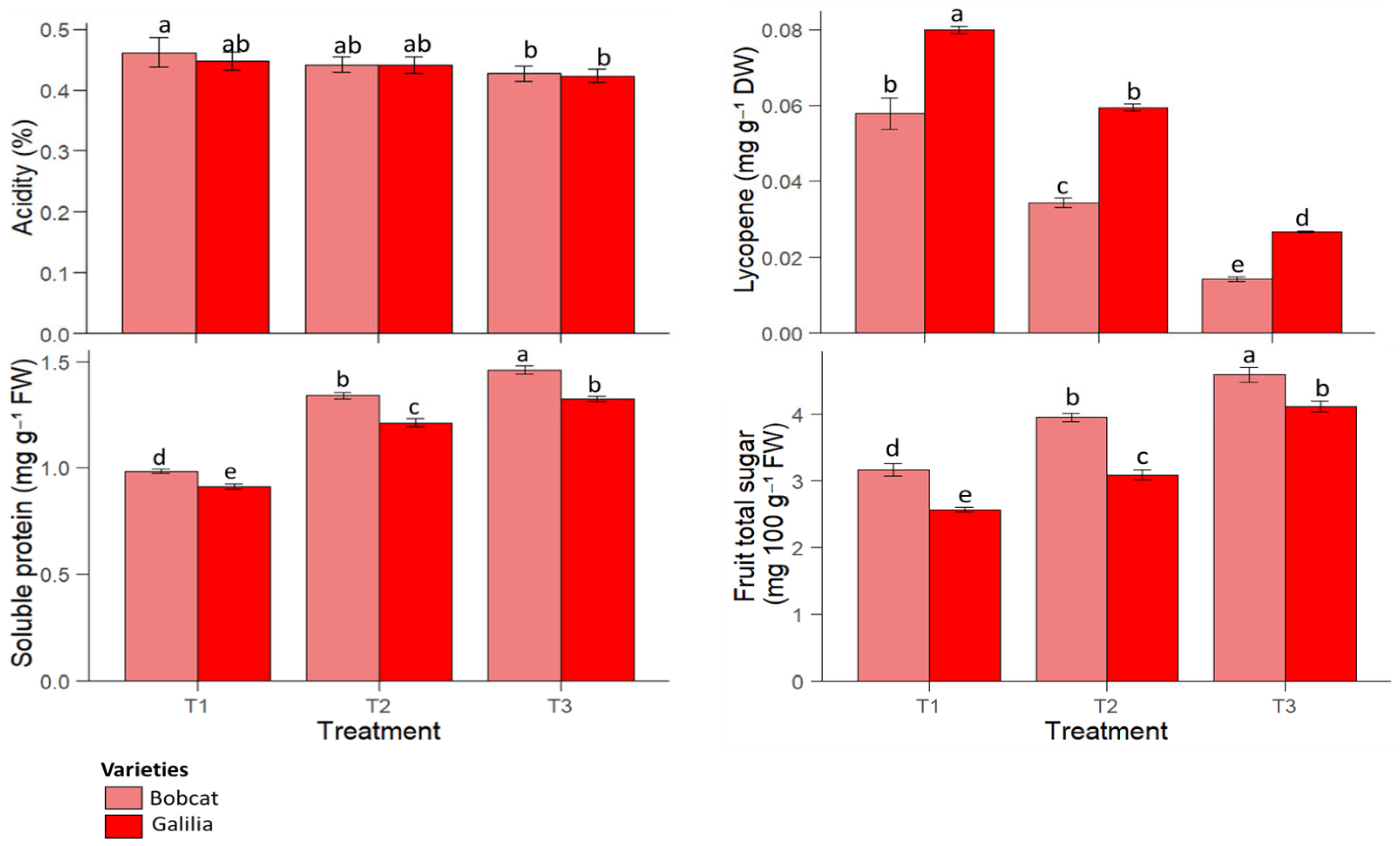

3.3.2. Fruit Quality Parameters

3.3.3. Soil Chemical Properties

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Chemical Properties

4.2. Growth Parameters

4.3. Physiological and Biochemical Traits

4.4. Yield Response

4.5. Fruit Quality Attributes

4.6. Correlations and Principal Component Analysis

4.7. Agronomic and Environmental Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAS | Atomic absorption spectroscopy |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| DBO5 | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| FM | Fresh matter |

| GW | Groundwater |

| MBR | Membrane bioreactor |

| OM | Organic matter |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RWC | Relative water content |

| SPAD | Soil–plant analysis development |

| TWW | Treated wastewater |

| WWTP | wastewater treatment plant |

References

- Kuper, M.; Leduc, C.; Massuel, S.; Bouarfa, S. Topical Collection: Groundwater-Based Agriculture in the Mediterranean. Hydrogeol. J. 2017, 25, 1525–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Pozo, J.L.; Alcalá, F.J.; Poyatos, J.M.; Martín-Pascual, J. Wastewater Reuse for Irrigation Agriculture in Morocco: Influence of Regulation on Feasible Implementation. Land 2022, 11, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Fader, M.; Garrabou, J.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Iglesias, A.; Lange, M.A.; Lionello, P.; Llasat, M.C.; Paz, S.; et al. Climate Change and Interconnected Risks to Sustainable Development in the Mediterranean. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheierling, S.M.; Bartone, C.R.; Mara, D.D.; Drechsel, P. Towards an Agenda for Improving Wastewater Use in Agriculture. Water Int. 2011, 36, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bdour, A.N.; Hamdi, M.R.; Tarawneh, Z. Perspectives on Sustainable Wastewater Treatment Technologies and Reuse Options in the Urban Areas of the Mediterranean Region. Desalination 2009, 237, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; Bahri, A.; Sato, T.; Al-Karadsheh, E. Wastewater Production, Treatment, and Irrigation in Middle East and North Africa. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2010, 24, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, F.J.; Martín-Martín, M.; Guerrera, F.; Martínez-Valderrama, J.; Robles-Marín, P. A Feasible Methodology for Groundwater Resource Modelling for Sustainable Use in Sparse-Data Drylands: Application to the Amtoudi Oasis in the Northern Sahara. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okello, C.; Githiora, Y.W.; Sithole, S.; Owuor, M.A. Nature-Based Solutions for Water Resource Management in Africa’s Arid and Sem-Arid Lands (ASALs): A Systematic Review of Existing Interventions. Nat.-Based Solut. 2024, 6, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, S. Gestion de la Rareté de l’Eau en Milieu Urbain au Maroc; Banque mondiale report; Banque mondiale: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benlemlih, N.; Elghali Khiyati, M.; El Aammouri, S.; Ibriz, M. A Review on Wastewater and Its Use in Agriculture in Morocco: Situation, Case Study and Recommendations. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2024, 17, 5132–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonel, L.P.; Bize, A.; Mariadassou, M.; Midoux, C.; Schneider, J.; Tonetti, A.L. Impacts of Disinfected Wastewater Irrigation on Soil Characteristics, Microbial Community Composition, and Crop Yield. Blue-Green. Syst. 2022, 4, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjaa, H.; Kajeiou, H.; Azizi, A.; Benayad, O.; Ibriz, M.; Ouhssine, M. Physico-Chemical and Bacteriological Evaluation of the Activated Sludge Wastewater Treatment Plant in Kenitra City, Morocco. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2025, 18, 2732–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, M.; Restrepo, I. Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture: A Review about Its Limitations and Benefits. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, N.; Auajjar, N.; El Aammouri, S.; Nizar, Y.; Ibriz, M. Physicochemical Characterization of the Sludge Generated by the Wastewater Treatment Plant of Kenitra. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2023, 16, 5366–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shao, G.; Wu, S.; Xiaojun, W.; Lu, J.; Cui, J. Changes in Soil Salinity under Treated Wastewater Irrigation: A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 106986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wakelin, S.A.; Liang, Y.; Chu, G. Soil Microbial Activity and Community Structure as Affected by Exposure to Chloride and Chloride-Sulfate Salts. J. Arid. Land. 2018, 10, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, S.M.; Alduina, R.; Badalucco, L.; Capri, F.C.; Di Leto, Y.; Gallo, G.; Laudicina, V.A.; Paliaga, S.; Mannina, G. Water Reuse of Treated Domestic Wastewater in Agriculture: Effects on Tomato Plants, Soil Nutrient Availability and Microbial Community Structure. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 928, 172259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brital, R.; Ibriz, M.; Benmrich, A.M.; Benyahia, H.; Aboutayeb, R.; Abail, Z. Soil and Leaf Nutrient Status of Selected Valencia Orange Orchards in the Gharb Plain of Morocco. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.L.; Nie, Z.Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, R.Z.; Zhang, T.Y.; Miao, Y.; Ma, L.; et al. Characteristics of Clay Dispersion and Its Influencing Factors in Saline-Sodic Soils of Songnen Plain, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonune, A.; Ghate, R. Developments in Wastewater Treatment Methods. Desalination 2004, 167, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanae, M.; Ouijdane, B.; Abdelmajid, S.; Hamza, K.; Abderrahim, B.; Mohammed, O. Evaluation of the Wastewater Treatment Plant Efficiency in Western Morocco, Kenitra City. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2024, 17, 3358–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, P.R.; Shahid, M.K.; Dash, R.R.; Bhunia, P.; Liu, D.; Varjani, S.; Zhang, T.C.; Surampalli, R.Y. Nutrient Removal from Domestic Wastewater: A Comprehensive Review on Conventional and Advanced Technologies. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayomi, O.V.; Olawoyin, D.C.; Oguntimehin, O.; Mustapha, L.S.; Kolade, S.O.; Oladoye, P.O.; Oh, S.; Obayomi, K.S. Exploring Emerging Water Treatment Technologies for the Removal of Microbial Pathogens. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2024, 8, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, R.G.; Bohs, L.; Migid, H.A.; Santiago-Valentin, E.; Garcia, V.F.; Collier, S.M. A Molecular Phylogeny of the Solanaceae. Taxon 2008, 57, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, R.U.; Abubakar, A.A.; Muhammad, A. Effect of Water Stress on the Morphology of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum M.) at Different Growth Stages. Asian J. Plant Biol. 2023, 5, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, V.; Russo, D.; Rivelli, A.R.; Battaglia, D.; Bufo, S.A.; Caccavo, V.; Forlano, P.; Lelario, F.; Milella, L.; Montinaro, L.; et al. Wastewater Irrigation and Trichoderma Colonization in Tomato Plants: Effects on Plant Traits, Antioxidant Activity, and Performance of the Insect Pest Macrosiphum Euphorbiae. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 18887–18899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Abubakar, M.M.; Sale, S. Enhancing the Shelf Life of Tomato Fruits Using Plant Material during Storage. J. Hortic. Postharvest Res. 2020, 3, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Pêche Maritime, du Développement Rural et des Eaux et Forêts. Agriculture en chiffres 2018; Morocco 2019. p. 26. Available online: http://www.mpm.gov.ma/wps/portal/PortaIl-MPM/ACCUEIL/!ut/p/b1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfGjzOIN3Nx9_I0MzAwsAlwNDTyDXC3CfEycgCxToIJIkAIcwNGAkP5w_Sj8SsxgCnBb4eeRn5uqX5AbYZBl4qgIAA-XFU8!/dl4/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/#&panel1-3 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Climate Toolbox. Data Download. Climate Toolbox. Available online: https://climatetoolbox.org/tool/data-download (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Tiwari, R.; Mahalpure, G.S. A Detailed Review of pH and Its Applications. J. Pharm. Biopharm. Res. 2024, 6, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, J.D.; Kandiah, A.; Mashali, A.M.; Rhoades, J.D. The Use of Saline Waters for Crop Production. In FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, L.E.; Moodie, C.D. Carbonate. In Methods of Soil Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1965; pp. 1379–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.; Sommers, L. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2, Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Benton Jones, J., Jr. Laboratory Guide for Conducting Soil Tests and Plant Analysis, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ruget, F.; Bonhomme, R.; Chartier, M. Estimation simple de la surface foliaire de plantes de maïs en croissance. Agronomie 1996, 16, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper Enzymes in Isolated Chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta Vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina, G.; Camelin, E.; Tommasi, T.; Fino, D.; Pugliese, M. Anaerobic Digestates from Sewage Sludge Used as Fertilizer on a Poor Alkaline Sandy Soil and on a Peat Substrate: Effects on Tomato Plants Growth and on Soil Properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 269, 110767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmés, J.; Flexas, J.; Savé, R.; Medrano, H. Water Relations and Stomatal Characteristics of Mediterranean Plants with Different Growth Forms and Leaf Habits: Responses to Water Stress and Recovery. Plant Soil. 2007, 290, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monneveux, P.; Nemmar, M. Contribution à l’étude de la résistance à la sécheresse chez le blé tendre (Triticum aestivum L.) et chez le blé dur (Triticum durum Desf.): Étude de l’accumulation de la proline au cours du cycle de développement. Agronomie 1986, 6, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.D.; Sahin, U. Effects of Different Irrigation Practices Using Treated Wastewater on Tomato Yields, Quality, Water Productivity, and Soil and Fruit Mineral Contents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 24856–24879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, W.W.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Collins, J.K. A Quantitative Assay for Lycopene That Utilizes Reduced Volumes of Organic Solvents. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2002, 15, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, F.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Niu, T.; Lü, X.; Liu, M. Effects of Monosaccharide Composition on Quantitative Analysis of Total Sugar Content by Phenol-Sulfuric Acid Method. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 963318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein Measurement with the Folin Phenol Reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Sarkar, U.; Taraphder, S.; Datta, S.; Swain, D.; Saikhom, R.; Panda, S.; Laishram, M. Multivariate Statistical Data Analysis-Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Int. J. Livest. Res. 2017, 7, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori, S.; Abebrese, D.K.; Růžičková, I.; Wanner, J. Reuse of Treated Wastewater for Crop Irrigation: Water Suitability, Fertilization Potential, and Impact on Selected Soil Physicochemical Properties. Water 2024, 16, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergine, P.; Salerno, C.; Libutti, A.; Beneduce, L.; Gatta, G.; Berardi, G.; Pollice, A. Closing the Water Cycle in the Agro-Industrial Sector by Reusing Treated Wastewater for Irrigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, O.; Budak, B.; Sen, F.; Ongun, A.R.; Tepecik, M.; Ata, S. Solid and Liquid Digestate Generated from Biogas Production as a Fertilizer Source in Processing Tomato Yield, Quality and Some Health-Related Compounds. J. Agric. Sci. 2025, 163, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedbabis, S.; Ben Rouina, B.; Boukhris, M.; Ferrara, G. Effects of Irrigation with Treated Wastewater on Root and Fruit Mineral Elements of Chemlali Olive Cultivar. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 973638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzakis, N.; Saridakis, C.; Chrysargyris, A. Treated Wastewater and Fertigation Applied for Greenhouse Tomato Cultivation Grown in Municipal Solid Waste Compost and Soil Mixtures. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F.; Farissi, M. Reuse of Treated Wastewater in Agriculture: Solving Water Deficit Problems in Arid Areas (Review). Ann. West Univ. Timis. Ser. Biol. 2014, 17, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori, S.; Abebrese, D.K.; Klement, A.; Provazník, D.; Tomášková, I.; Růžičková, I.; Wanner, J. Impact of treated wastewater on plant growth: Leaf fluorescence, reflectance, and biomass-based assessment. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 89, 1647–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghobar, M.A.; Suresha, S. Growth and Yield of Tomato, Napier Grass and Sugarcane Crops as Influenced by Wastewater Irrigation in Mysore, Karnataka, India. World Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 3, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Roosta, H.R.; Hamidpour, M. Effects of Foliar Application of Some Macro- and Micro-Nutrients on Tomato Plants in Aquaponic and Hydroponic Systems. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 129, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwaza, S.T.; Magwaza, L.S.; Odindo, A.O.; Mditshwa, A.; Buckley, C. Partially Treated Domestic Wastewater as a Nutrient Source for Tomatoes (Lycopersicum solanum) Grown in a Hydroponic System: Effect on Nutrient Absorption and Yield. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajlaoui, H.; Akrimi, R.; Sayehi, S.; Hachicha, S. Usage of Treated Greywater as an Alternative Irrigation Source for Tomatoes Cultivation. Water Environ. J. 2022, 36, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gaadi, K.A.; Tola, E.; Madugundu, R.; Zeyada, A.M.; Alameen, A.A.; Edrris, M.K.; Edrees, H.F.; Mahjoop, O. Response of Leaf Photosynthesis, Chlorophyll Content and Yield of Hydroponic Tomatoes to Different Water Salinity Levels. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0293098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.K.; Kumar, M.; Li, W.; Luo, Y.; Burritt, D.J.; Alkan, N.; Tran, L.-S.P. Enhancing Salt Tolerance of Plants: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Exogenous Chemical Treatments and Molecular Approaches. Cells 2020, 9, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouansafi, S.; Bellali, F.; Maaghloud, H.; Kabine, M. Treated Wastewater Irrigation of Tomato: Effects on Crop Production, and on Physico-Chemical Properties, SDH Activity and Microbiological Characteristics of Fruits. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2022, 24, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Christou, A.; Maratheftis, G.; Eliadou, E.; Michael, C.; Hapeshi, E.; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Impact Assessment of the Reuse of Two Discrete Treated Wastewaters for the Irrigation of Tomato Crop on the Soil Geochemical Properties, Fruit Safety and Crop Productivity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 192, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G.; Singh, K.G. Response of Greenhouse Tomato to Irrigation and Fertigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 84, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, G.; Libutti, A.; Gagliardi, A.; Beneduce, L.; Brusetti, L.; Borruso, L.; Disciglio, G.; Tarantino, E. Treated Agro-Industrial Wastewater Irrigation of Tomato Crop: Effects on Qualitative/Quantitative Characteristics of Production and Microbiological Properties of the Soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 149, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecka, D.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Jędrusek-Golińska, A.; Dziedzic, K.; Hamułka, J.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Walkowiak, J. Lycopene in Tomatoes and Tomato Products. Open Chem. 2020, 18, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, G.; Libutti, A.; Gagliardi, A.; Disciglio, G.; Beneduce, L.; d’Antuono, M.; Rendina, M.; Tarantino, E. Effects of Treated Agro-Industrial Wastewater Irrigation on Tomato Processing Quality. Ital. J. Agron. 2015, 10, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorais, M.; Ehret, D.L.; Papadopoulos, A.P. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Health Components: From the Seed to the Consumer. Phytochem. Rev. 2008, 7, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffo, A.; Leonardi, C.; Fogliano, V.; Ambrosino, P.; Salucci, M.; Gennaro, L.; Bugianesi, R.; Giuffrida, F.; Quaglia, G. Nutritional Value of Cherry Tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum Cv. Naomi F1) Harvested at Different Ripening Stages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6550–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.Y.; Sina, A.A.I.; Khandker, S.S.; Neesa, L.; Tanvir, E.M.; Kabir, A.; Khalil, M.I.; Gan, S.H. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds in Tomatoes and Their Impact on Human Health and Disease: A Review. Foods 2020, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattan, S.R.; Díaz, F.J.; Pedrero, F.; Vivaldi, G.A. Assessing the Suitability of Saline Wastewaters for Irrigation of Citrus Spp.: Emphasis on Boron and Specific-Ion Interactions. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 157, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Shahid, M.; Natasha; Bibi, I.; Sarwar, T.; Shah, A.H.; Niazi, N.K. A Review of Environmental Contamination and Health Risk Assessment of Wastewater Use for Crop Irrigation with a Focus on Low and High-Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.K.; Bhandari, S.R.; Jo, J.S.; Song, J.W.; Lee, J.G. Effect of Drought Stress on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters, Phytochemical Contents, and Antioxidant Activities in Lettuce Seedlings. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel Haj, H.; Ben Zhir, K.; Aboulhassan, M.A.; El Ouarghi, H. Impact Assessment of Treated Wastewater Reuse for Irrigation: Growth Potential and Development of Lettuce in Al Hoceima Province, Morocco. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 364, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijowska-Oberc, J.; Dylewski, Ł.; Ratajczak, E. Proline Concentrations in Seedlings of Woody Plants Change with Drought Stress Duration and Are Mediated by Seed Characteristics: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Psarras, G.; Chartzoulakis, K.; Kasapakis, I.; Kloppmann, W. Effect of Different Irrigation Techniques and Water Qualities on Yield, Fruit Quality and Health Risks of Tomato Plants. In Proceedings of the VII International Symposium on Irrigation of Horticultural Crops, Geisenheim, Germany, 16–20 July 2014; pp. 601–608. [Google Scholar]

- Alfosea-Simón, M.; Zavala-Gonzalez, E.A.; Camara-Zapata, J.M.; Martínez-Nicolás, J.J.; Simón, I.; Simón-Grao, S.; García-Sánchez, F. Effect of Foliar Application of Amino Acids on the Salinity Tolerance of Tomato Plants Cultivated under Hydroponic System. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, W.; Lv, H.; Liang, B.; Jin, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, W. Animal-Derived Plant Biostimulant Alleviates Drought Stress by Regulating Photosynthesis, Osmotic Adjustment, and Antioxidant Systems in Tomato Plants. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 305, 111365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.S.; Huda, A.K.S.; Alsafran, M.; Jayasena, V.; Jawaid, M.Z.; Chen, Z.-H.; Ahmed, T. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Yield Response to Drip Irrigation and Nitrogen Application Rates in Open-Field Cultivation in Arid Environments. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334, 113298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Olza, M.; Blanco-Gutiérrez, I.; Esteve, P.; Gómez-Ramos, A.; Bolinches, A. Using Reclaimed Water to Cope with Water Scarcity: An Alternative for Agricultural Irrigation in Spain. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.; Carlos, C.; Oliveira, A.A.; Barros, A.N. Reuse of Treated Wastewater to Address Water Scarcity in Viticulture: A Comprehensive Review. Agronomy 2025, 15, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, C.; Pellegrino, A.; Saita, A.; Calcagno, S.; Cosentino, S.L.; Scandurra, A.; Cafaro, V. A Study on the Effect of Biostimulant Application on Yield and Quality of Tomato under Long-Lasting Water Stress Conditions. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Average ± SE | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.8 ± 0.31 | |

| Electrical conductivity (EC) | 300 ± 5.2 | μS/cm |

| Total CaCO3 | 0.14 ± 0.07 | % |

| Organic matter (OM) | 0.26 ± 0.1 | % |

| P2O5 | 230 ± 1.63 | mg/kg |

| K2O | 56.55 ± 0.31 | mg/kg |

| Clay | 2.2 ± 0.47 | % |

| Fine silt | 1.6 ± 0.57 | % |

| Coarse silt | 2.4 ± 0.51 | % |

| Fine sand | 30 ± 2.7 | % |

| Coarse sand | 63.8 ± 6.55 | % |

| Parameters | GW T1 | TWW T2 | TWW T3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.29 ± 0.113 | 6 ± 0.26 | 7.29 ± 0.069 |

| EC (μS/cm) | 655 ± 5.213 | 767 ± 2.44 | 1579 ± 2.442 |

| T° | 19 ± 0.953 | 20 ± 0.44 | 22 ± 0.44 |

| N (mg/L) | 0.087 ± 0.02 | 1.73 ± 0.762 | 3.38 ± 2.442 |

| P (mg/L) | 0.009 ± 0.003 | 0.28 ± 0.026 | 0.77 ± 0.017 |

| K (mg/L) | 1.6 ± 0.042 | 6.76 ± 0.061 | 27.2 ± 0.589 |

| Na+ (mg/L) | 43.9 ± 0.139 | 71.5 ± 0.156 | 155.6 ± 0.225 |

| Cl− (mg/L) | 108 ± 0.433 | 132 ± 0.52 | 310.5 ± 2.078 |

| Ca2+ (mg/L) | 110 ± 0.052 | 121 ± 0.087 | 149 ± 0.156 |

| Mg2+ (mg/L) | 6.8 ± 0.225 | 8.45 ± 0.26 | 11.59 ± 0.346 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 0.4 ± 0.139 | 2 ± 0.346 | 3.9 ± 0.26 |

| TSS (mg/L) | 0.9 ± 0.173 | 2.34 ± 0.173 | 45 ± 1.091 |

| COD (mg O2/L) | 8.9 ± 0.208 | 30.61 ± 0.296 | 125 ± 1.542 |

| BOD5 (mg O2/L) | 1.45 ± 0.208 | 23.22 ± 0.191 | 34 ± 0.762 |

| Samples | pH | EC (μS/cm) | CaCO3 (%) | OM % | P2O5 | K2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Soil, T1) V1 | 7.40 ± 0.225 | 285.66 ± 2.546 | 2.18 ± 0.242 | 0.34 ± 0.069 | 15.93 ± 0.225 | 37.15 ± 0.225 |

| (Soil, T2) V1 | 7.64 ± 0.208 | 475.33 ± 2.338 | 2.01 ± 0.035 | 0.39 ± 0.069 | 16.42 ± 0.208 | 69.60 ± 0.641 |

| (Soil, T3) V1 | 7.85 ± 0.208 | 299.00 ± 1.420 | 2.23 ± 0.052 | 0.31 ± 0.069 | 12.35 ± 0.191 | 72.89 ± 0.866 |

| (Soil, T1) V2 | 7.75 ± 0.191 | 365.33 ± 1.871 | 1.42 ± 0.069 | 0.29 ± 0.052 | 16.12 ± 0.260 | 37.98 ± 0.849 |

| (Soil, T2) V2 | 7.71 ± 0.121 | 298.33 ± 1.749 | 1.12 ± 0.069 | 0.39 ± 0.052 | 16.66 ± 0.208 | 70.17 ± 0.468 |

| (Soil, T3) V2 | 7.67 ± 0.156 | 208.33 ± 2.546 | 1.56 ± 0.069 | 0.12 ± 0.052 | 12.57 ± 0.139 | 74.01 ± 0.675 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benlemlih, N.; Brienza, M.; Trotta, V.; Hammani, A.; Youssoufi, E.E.; El Bahja, F.; Brital, R.; El Aammouri, S.; Ait Barka, E.; Ibriz, M. Effect of Treated Wastewater Quality on Agronomic Performance, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122824

Benlemlih N, Brienza M, Trotta V, Hammani A, Youssoufi EE, El Bahja F, Brital R, El Aammouri S, Ait Barka E, Ibriz M. Effect of Treated Wastewater Quality on Agronomic Performance, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122824

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenlemlih, Noura, Monica Brienza, Vincenzo Trotta, Ali Hammani, Ehssan Elmeknassi Youssoufi, Fatima El Bahja, Rania Brital, Safae El Aammouri, Essaïd Ait Barka, and Mohammed Ibriz. 2025. "Effect of Treated Wastewater Quality on Agronomic Performance, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.)" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122824

APA StyleBenlemlih, N., Brienza, M., Trotta, V., Hammani, A., Youssoufi, E. E., El Bahja, F., Brital, R., El Aammouri, S., Ait Barka, E., & Ibriz, M. (2025). Effect of Treated Wastewater Quality on Agronomic Performance, Yield, and Nutritional Composition of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Agronomy, 15(12), 2824. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122824