Sustainable Management Strategies for Acarine Pests of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Host Plants

2.2. Pest Mite Colonies

2.3. Botanical Pesticides—Laboratory Bioassays

2.4. Botanical Pesticides—Greenhouse Experiments

2.5. Biological Control of A. cannabicola—Laboratory Bioassays

2.6. Compatibility Bioassays

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

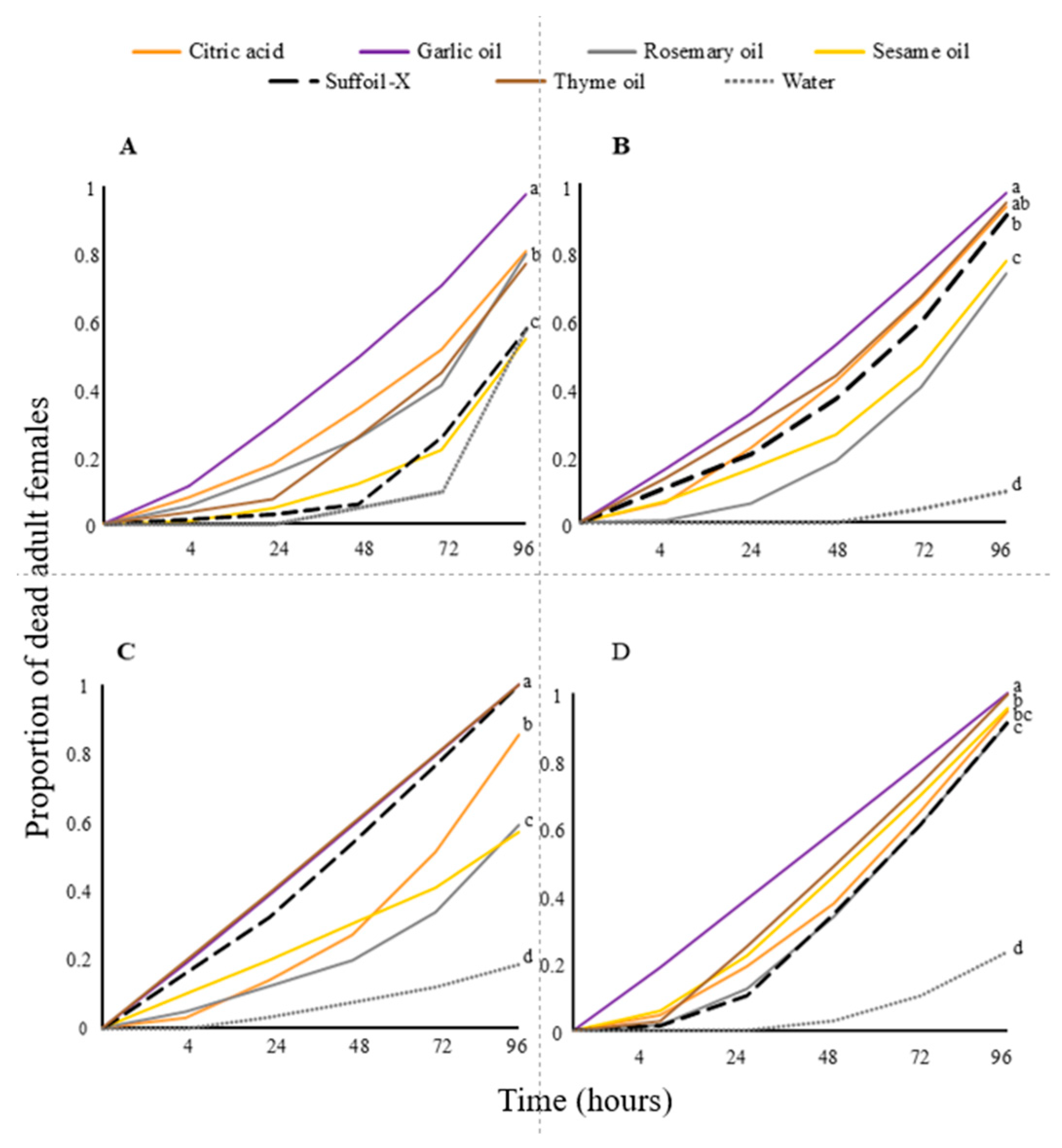

3.1. Botanical Pesticides—Laboratory Bioassays

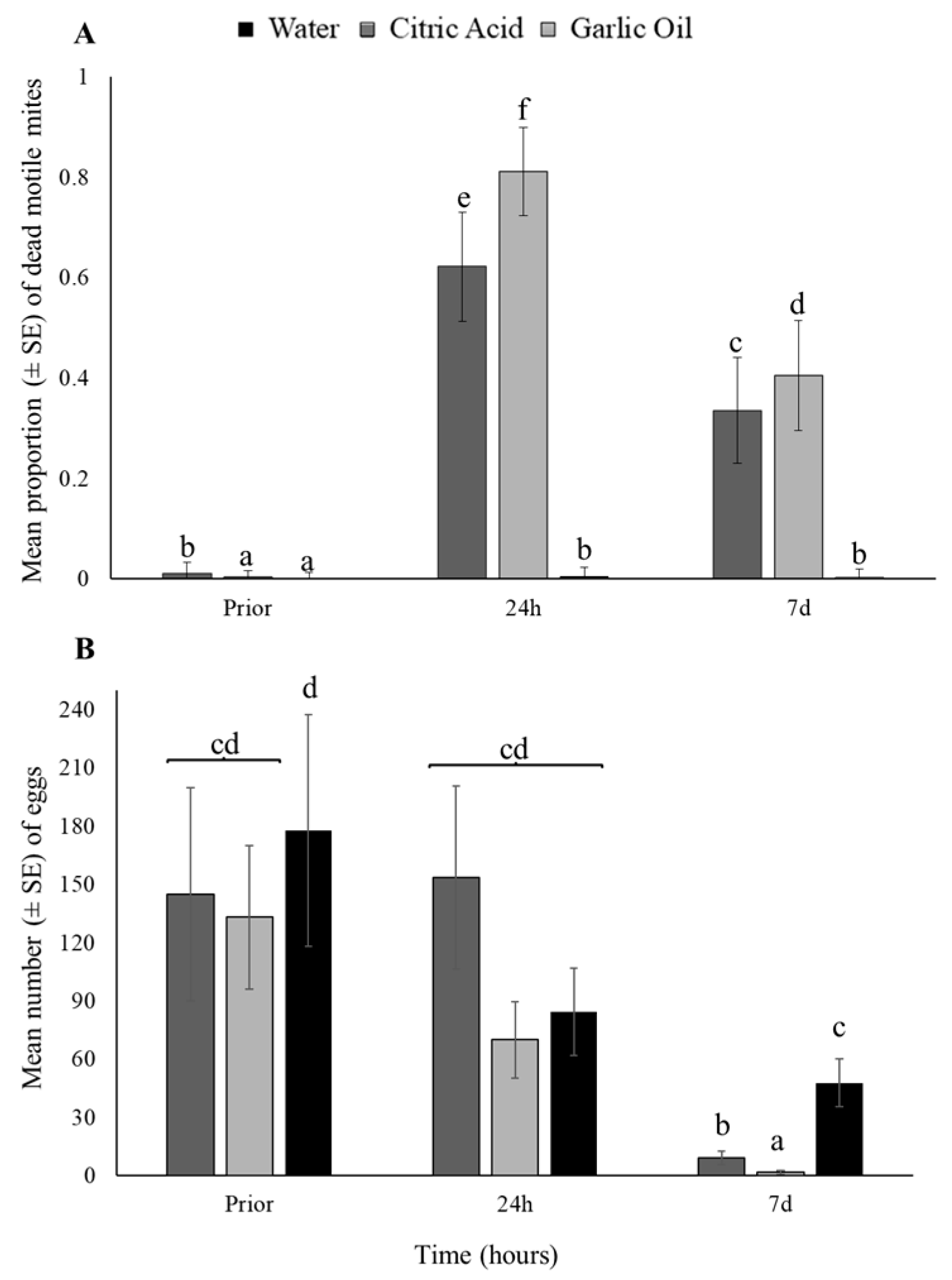

3.2. Botanical Pesticides—Greenhouse Experiments

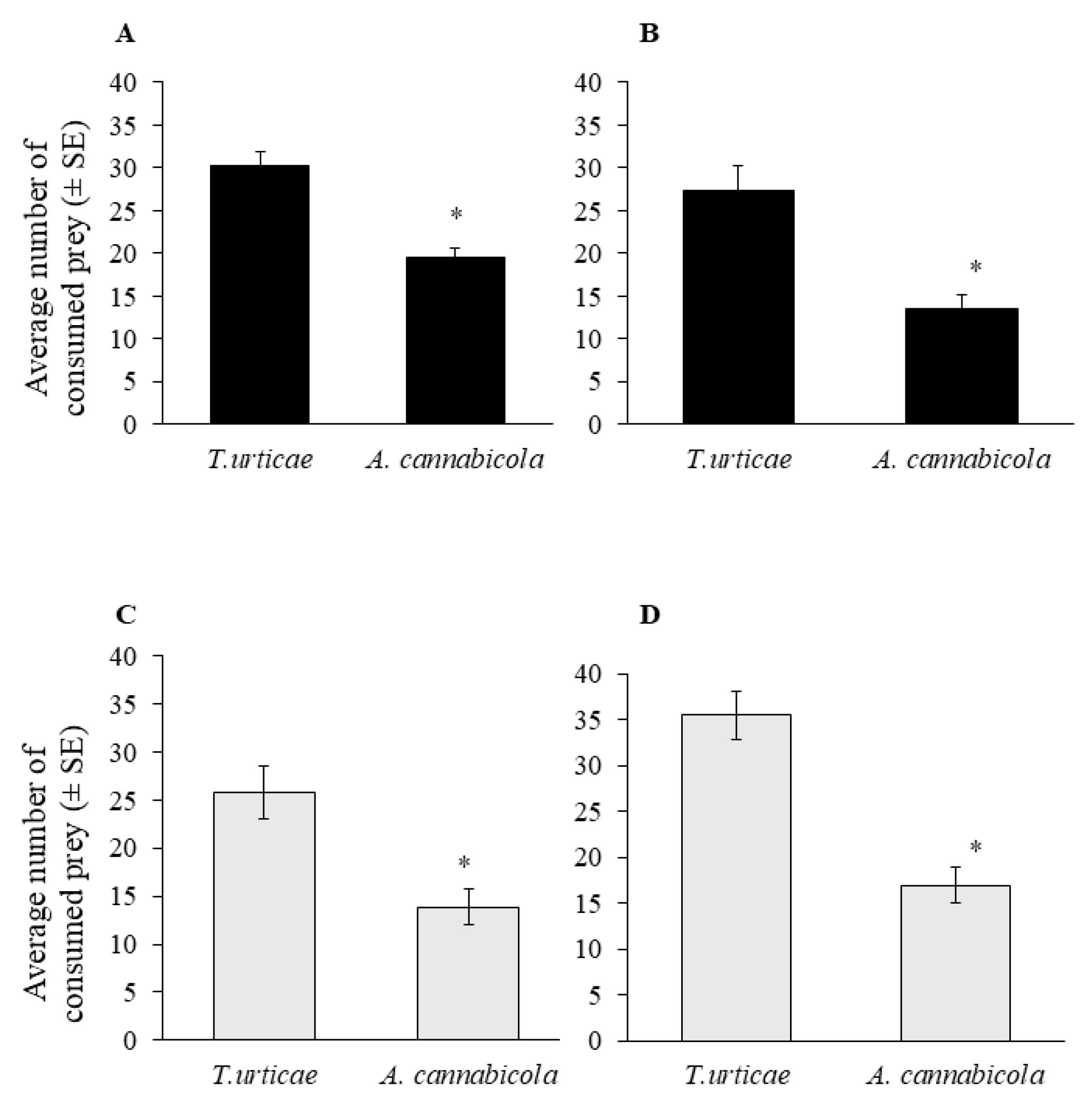

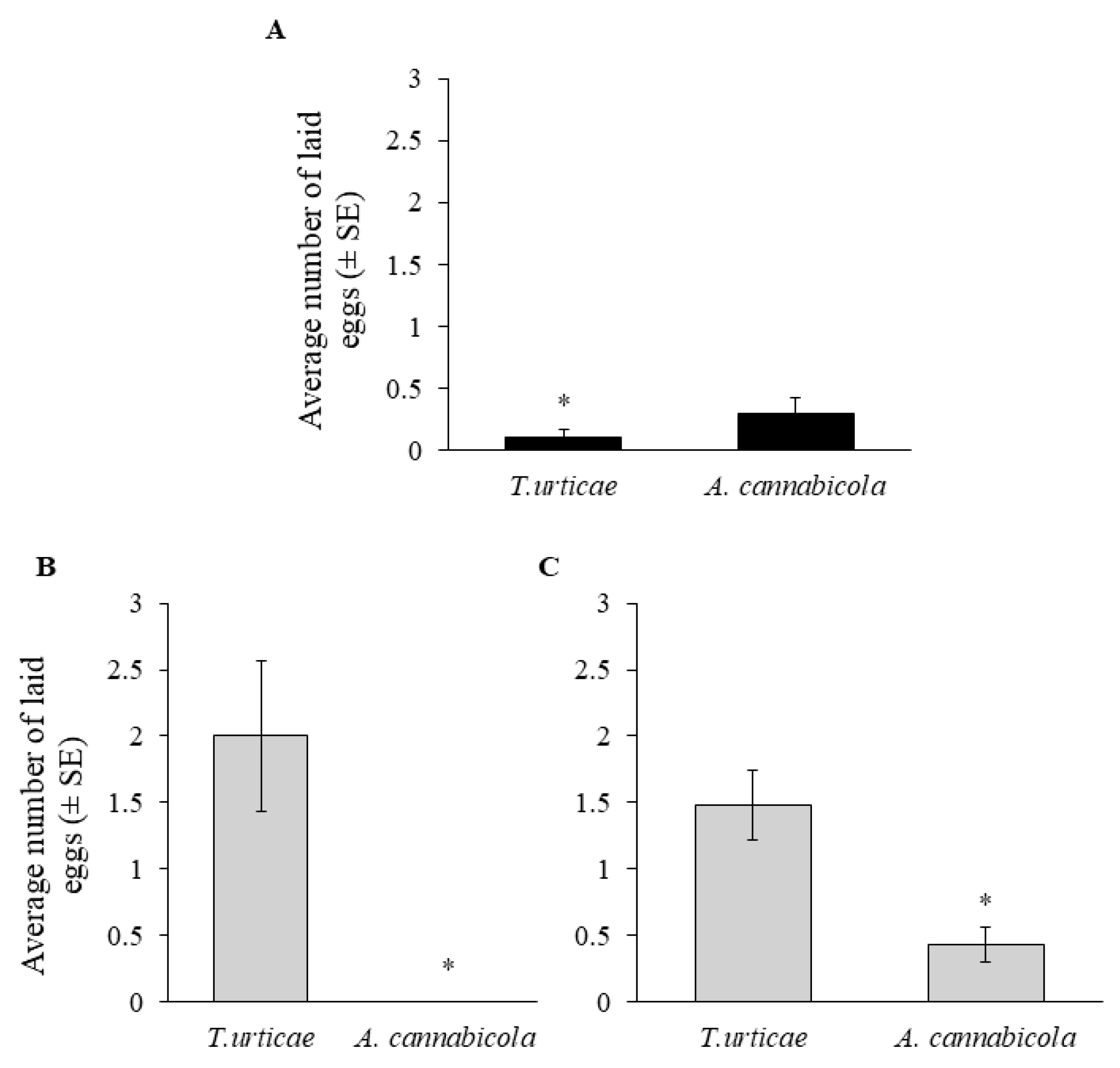

3.3. Biological Control of A. cannabicola—Laboratory Bioassays

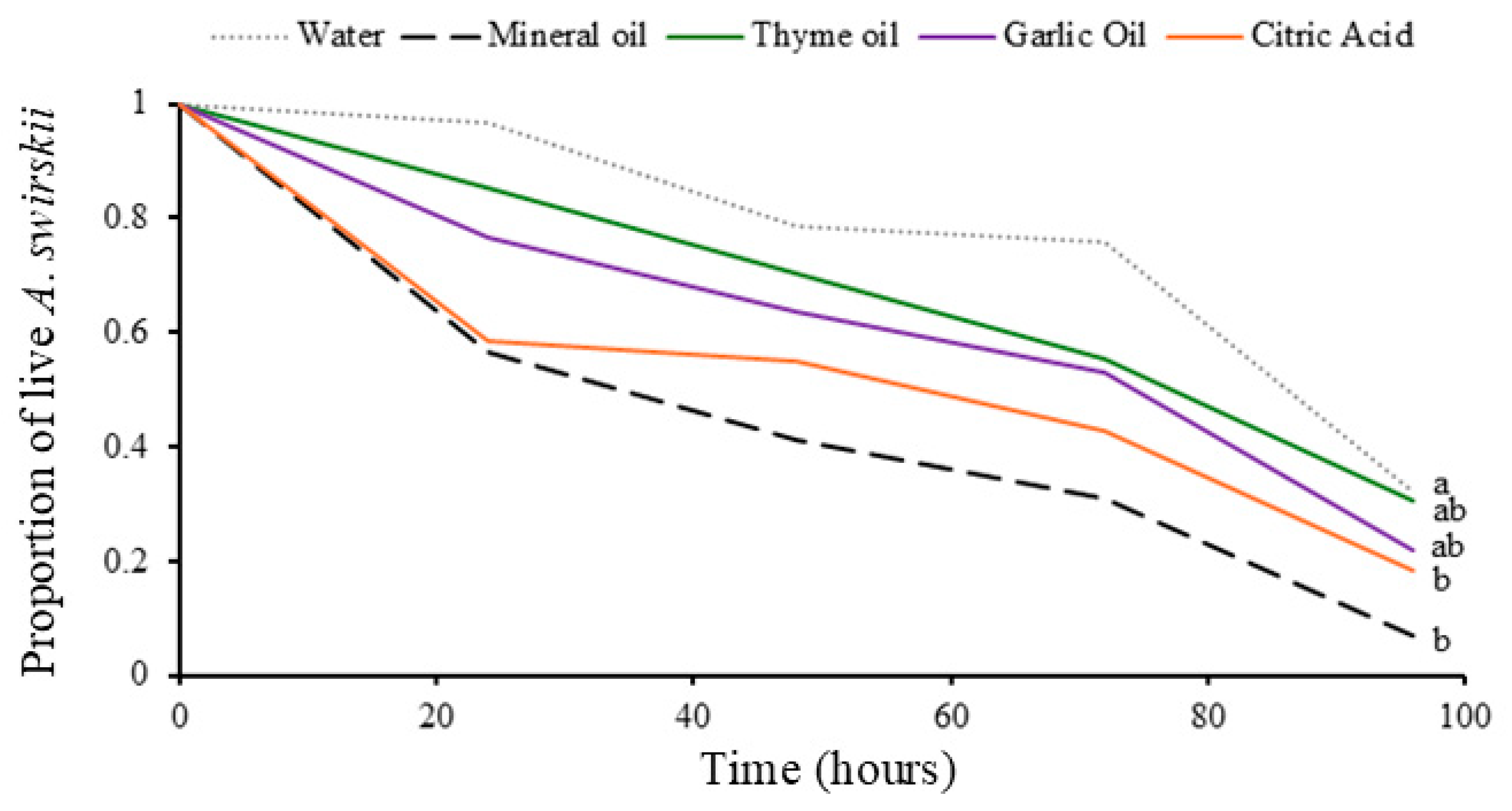

3.4. Compatibility Bioassays

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| FDACS-DPI | Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services-Division of Plant Industry |

| IPM | Integrated Pest Management |

| THC | Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol |

References

- Small, E.; Marcus, D. Hemp: A new crop with new uses for North America. Trends New Crops New Uses 2002, 24, 284–326. [Google Scholar]

- Tancig, M.; Kelly-Begazo, C.; Kaur, N.; Sharma, L.; Brym, Z. Industrial hemp in the United States: Definition and history: SS-AGR-457/AG458, 9/2021. EDIS 2021, 2021, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.W.; Mundell, R. An Introduction to Industrial Hemp and Hemp Agronomy; University Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service: Lexington, KY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blare, T.; Rivera, M.; Ballen, F.H.; Brym, Z. Is a viable hemp industry in Florida’s future? EDIS 2022, 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS); Agricultural Statistics Board; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). National Hemp Report 2025. Available online: https://share.google/eAPXInciZnf7MaCQW (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Fike, J. Industrial hemp: Renewed opportunities for an ancient crop. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2016, 35, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.Z.; McKenzie, C.L.; Osborne, L.S. Arthropod and mollusk pests of hemp, Cannabis sativa (Rosales: Cannabaceae), and their indoor management plan in Florida. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2024, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, E.A.; Skelley, P.E. An initial list of arthropods on hemp (Cannabis sativa L.: Cannabaceae) in Florida. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry (FDACS-DPI, P002203). Entomol. Circ. 2023, 445, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- McPartland, J.M. A survey of hemp diseases and pests. In Advances in Hemp Research; Haworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pulkoski, M.; Burrack, H. Assessing the impact of piercing-sucking pests on greenhouse-grown industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Environ. Entomol. 2024, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döker, İ.; Revynthi, A.M.; Mannion, C.; Carrillo, D. First report of acaricide resistance in Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) from South Florida. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2020, 25, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migeon, A.; Nouguier, E.; Dorkeld, F. Spider Mites Web: A Comprehensive Database for the Tetranychidae. Available online: https://www1.montpellier.inrae.fr/CBGP/spmweb (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Gerson, U. Biology and control of the broad mite, Polyphagotarsonemus latus (Banks) (Acari: Tarsonemidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1992, 13, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelley, P.E.; Buss, E.A.; Allen, J.S.; Bolton, S.J.; Deeter, L.A.; Fulton, J.C.; Greer, D.J.; Halbert, S.E.; Hayden, J.E.; Moore, M.R.; et al. Adventive arthropods in Florida as reported by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, 1990–2023. Fla. Entomol. 2025, 108, 20240027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, R.; Viloria, Z.; Ochoa, R.; Ulsamer, A. Hemp Russet Mite, a Key Pest of Hemp in Kentucky; University Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service: Lexington, KY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniec, A.; Lathrop-Melting, A.; Janecek, T.; Nachappa, P.; Cranshaw, W.; Alnajjar, G.; Axtell, A. Suppression of hemp russet mite, Aculops cannabicola (Acari: Eriophyidae), in industrial hemp in greenhouse and field. Environ. Entomol. 2024, 53, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.F.; Panizzi, A.R.; Hunt, T.E.; Dourado, P.M.; Pitta, R.M.; Gonçalves, J. Challenges for adoption of integrated pest management (IPM): The soybean example. Neotrop. Entomol. 2021, 50, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzman, M.; Bàrberi, P.; Birch, A.N.E.; Boonekamp, P.; Dachbrodt-Saaydeh, S.; Graf, B.; Hommel, B.; Jensen, J.E.; Kiss, J.; Kudsk, P.; et al. Eight principles of integrated pest management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, K.T.; Hubert, T.D.; Amberg, J.J.; Cupp, A.R.; Dawson, V.K. Chemical controls for an integrated pest management program. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2021, 41, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčić, D.; Döker, İ.; Tsolakis, H. Bioacaricides in crop protection—What is the state of play? Insects 2025, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.H.; Tayde, A.R. Evaluation of bio-rational pesticides, against brinjal fruit and shoot borer, Leucinodes orbonalis Guen. on brinjal at Allahabad agroclimatic region. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 2049–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Hemp and Pesticides Brochure. FDACS 2020. Available online: https://ccmedia.fdacs.gov/content/download/91491/file/hemp-pesticides-brochure.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Nur, M.W.; Miah, M.R.U.; Amin, M.R. Management of aphid and pod borer of country bean using bio-rational pesticides. Bangladesh J. Ecol. 2020, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nile, A.S.; Kwon, Y.D.; Nile, S.H. Horticultural oils: Possible alternatives to chemical pesticides and insecticides. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 21127–21139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, C.R.; Sadof, C.S. Efficacy of horticultural oil and insecticidal soap against selected armored and soft scales. HortTechnology 2017, 27, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.S.; Soliman, M.F.; Abo-Ghalia, A.H.; Ghallab, M.M. The acaricidal activity of some essential and fixed oils against the two-spotted spider mite in relation to different temperatures. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2015, 61, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, D.; De Moraes, G.J.; Peña, J.E. (Eds.) Prospects for Biological Control of Plant Feeding Mites and Other Harmful Organisms; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, M.; van Houten, Y.; van Baal, E.; Groot, T. Use of predatory mites in commercial biocontrol: Current status and future prospects. Acarologia 2018, 58, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, U.; Smiley, R.L.; Ochoa, R. Mites (Acari) for Pest Control; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2003; Volume 558, pp. 173–218. [Google Scholar]

- Vechia, J.F.D.; Andrade, D.J.; Tassi, A.D.; Roda, A.; van Santen, E.; Carrillo, D. Can predatory mites aid in the management of the citrus leprosis mite? Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1304656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloyd, R. Compatibility conflict: Is the use of biological control agents with pesticides a viable management strategy? Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, 384 National Soybean Research Laboratory, 1101 West Peabody Drive, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. 2005; Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- McMurtry, J.A.; De Moraes, G.J.; Sourassou, N.F. Revision of the lifestyles of phytoseiid mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae) and implications for biological control strategies. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2013, 18, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, T.; Witters, J.; Nauen, R.; Duso, C.; Tirry, L. The control of eriophyoid mites: State of the art and future challenges. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010, 51, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overmeer, W.P.J. Rearing and handling. In Spider Mites: Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; Volume 1, pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, F.; Hartig, M.F. Package ‘DHARMa’I; R Project: Vienna, Austria, 2017; Volume 531, p. 532. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R.; Singmann, H.; Love, J.; Buerkner, P.; Herve, M. Package “Emmeans”. R Package Version 2018, 4.0–3. Available online: http://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartland, J.M.; Clarke, R.C.; Watson, D.P. Hemp Diseases and Pests: Management and Biological Control—An Advanced Treatise; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Azandeme-Hounmalon, G.Y.; Fellous, S.; Kreiter, S.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Subramanian, S.; Kungu, M.; Martin, T. Dispersal behavior of Tetranychus evansi and T. urticae on tomato at several spatial scales and densities: Implications for integrated pest management. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, A.; Rector, B.G.; Przychodzka, A.; Majer, A.; Zalewska, K.; Kuczynski, L.; Skoracka, A. Do mites eat and run? A systematic review of feeding and dispersal strategies. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2023, 198, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogran, C.E.; Ludwig, S.; Metz, B. Using Oils as Pesticides; Texas A&M AgriLife Extension: College Station, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cranshaw, W.; Baxendale, B. Insect Control: Horticultural Oils; Colorado State University Extension Service: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mossa, A.T.H.; Afia, S.I.; Mohafrash, S.M.M.; Abou-Awad, B.A. Formulation and characterization of garlic (Allium sativum L.) essential oil nanoemulsion and its acaricidal activity on eriophyid olive mites (Acari: Eriophyidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 10526–10537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Handique, G.; Barua, A.; Bora, F.R.; Rahman, A.; Muraleedharan, N. Comparative performances of jatropha oil and garlic oil with synthetic acaricides against red spider mite infesting tea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 88, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giosa, M.; Dale, A.G.; Wu, X.; Revynthi, A.M. Potential of commercial biorational and conventional pesticides to manage the Ruellia erinose mite in ornamental landscapes. Insects 2025, 16, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Grissa, K.L.; Mailleux, A.C.; Lognay, G.; Heuskin, S.; Mayoufi, S.; Hance, T. Effective concentrations of garlic distillate (Allium sativum) for the control of Tetranychus urticae (Tetranychidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 136, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prowse, G.M.; Galloway, T.S.; Foggo, A. Insecticidal activity of garlic juice in two dipteran pests. Agric. For. Entomol. 2006, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.C.; da Câmara, C.A.G.; Melo, J.P.R.; de Moraes, M.M. Acaricidal properties of essential oils from agro-industrial waste products from citric fruit against Tetranychus urticae. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, W.; Sabelis, M.W. (Eds.) Spider Mites: Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; Volume 1, pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay, J.; Scott-Dupree, C. Management of insect pests on cannabis in controlled environment production. In Handbook of Cannabis Production in Controlled Environments; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; p. 275. [Google Scholar]

- Duso, C.; Castagnoli, M.; Simoni, S.; Angeli, G. The impact of eriophyoids on crops: Recent issues on Aculus schlechtendali, Calepitrimerus vitis and Aculops lycopersici. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010, 51, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momen, F.M.; Abdel-Khalek, A. Effect of the tomato rust mite Aculops lycopersici (Acari: Eriophyidae) on the development and reproduction of three predatory phytoseiid mites. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2008, 28, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervaet, L.; De Vis, R.; De Clercq, P.; Van Leeuwen, T. Is the emerging mite pest Aculops lycopersici controllable? Global and genome-based insights in its biology and management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2635–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.H.; Shipp, L.; Buitenhuis, R. Predation, development, and oviposition by the predatory mite Amblyseius swirkii (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on tomato russet mite (Acari: Eriophyidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2010, 103, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, N.; Fathipour, Y.; Talebi, A.A. The efficiency of Amblyseius swirskii in control of Tetranychus urticae and Trialeurodes vaporariorum is affected by various factors. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2019, 109, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, F.J.; Knapp, M.; van Houten, Y.M.; Hoogerbrugge, H.; Belda, J.E. Amblyseius swirskii: What made this predatory mite such a successful biocontrol agent? Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2015, 65, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, A. The cannabis plant: Botany, cultivation and processing for use. In Cannabis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten, Y.M.; Glas, J.J.; Hoogerbrugge, H.; Rothe, J.; Bolckmans, K.J.F.; Simoni, S.; Van Arkel, J.; Alba, J.M.; Kant, M.R.; Sabelis, M.W. Herbivory-associated degradation of tomato trichomes and its impact on biological control of Aculops lycopersici. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2013, 60, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, C. Developing Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Strategies for Hemp Russet Mite (Aculops cannabicola Farkas) on Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Master’s Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nomikou, M.; Janssen, A.; Schraag, R.; Sabelis, M.W. Phytoseiid predators as potential biological control agents for Bemisia tabaci. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2001, 25, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duso, C.; Van Leeuwen, T.; Pozzebon, A. Improving the compatibility of pesticides and predatory mites: Recent findings on physiological and ecological selectivity. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2020, 39, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busuulwa, A.; Riley, S.S.; Revynthi, A.M.; Liburd, O.E.; Lahiri, S. Residual effect of commonly used insecticides on key predatory mites released for biocontrol in strawberry. J. Econ. Entomol. 2024, 117, 2461–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Taka, S.M.; Sweelam, M.A.; Heikal, H.M.; Walash, I.H. Toxicity and biological activity of five plant extracts to the two-spotted spider mite, Teteunychus urticae, and predatory mite, Amblyseius swirskii (Tetranychidae: Phytoseiidae). Acarines 2014, 8, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, T.; Keratum, A.; El-Hetawy, L. Formulation of abamectin and plant oil-based nanoemulsions with efficacy against the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) under laboratory and field conditions. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2022, 65, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product | Active Ingredient | Rate/ha | Solution | EPA Registration Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bush Doctor Force of Nature Insect Repellent | Garlic oil | 1.53 L/ha | 11.8 mL/L | FIFRA 25b-exempt |

| Nuke EM | Citric Acid | 0.1 L/ha | 62.5 mL/L | FIFRA 25b-exempt |

| Organocide bee safe 3-in-1 garden spray concentrate | Sesame oil | 0.04 L/ha | 23.4 mL/L | FIFRA 25b-exempt |

| SNS 217C | Rosemary oil | 0.65 L/ha | 5 mL/L | FIFRA 25b-exempt |

| Thyme Guard | Thyme oil | 5% | 50 mL/L | FIFRA 25b-exempt |

| Suffoil-X | Mineral oil | 2% | 20 mL/L | 48813-1-68539 |

| Water | NA | NA | NA |

| Response Variable | Treatment Effect | Time Effect | Interaction Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mite mortality | χ2 = 3466.19; d.f. = 2; p < 0.001 | χ2 = 3466.84; d.f. = 2; p < 0.001 | χ2 = 201.93; d.f. = 4; p < 0.001 |

| Mite oviposition | χ2 = 81.64; d.f. = 2; p < 0.001 | χ2 = 329.16; d.f. = 2; p < 0.001 | χ2 = 156.08; d.f. = 4; p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canon, M.A.; Ataide, L.M.S.; Villamarin, P.; De Giosa, M.; Osborne, L.S.; Tabanca, N.; Lahiri, S.; Revynthi, A.M. Sustainable Management Strategies for Acarine Pests of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa L.). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122785

Canon MA, Ataide LMS, Villamarin P, De Giosa M, Osborne LS, Tabanca N, Lahiri S, Revynthi AM. Sustainable Management Strategies for Acarine Pests of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa L.). Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122785

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanon, Maria A., Livia M. S. Ataide, Paola Villamarin, Marcello De Giosa, Lance S. Osborne, Nurhayat Tabanca, Sriyanka Lahiri, and Alexandra M. Revynthi. 2025. "Sustainable Management Strategies for Acarine Pests of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa L.)" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122785

APA StyleCanon, M. A., Ataide, L. M. S., Villamarin, P., De Giosa, M., Osborne, L. S., Tabanca, N., Lahiri, S., & Revynthi, A. M. (2025). Sustainable Management Strategies for Acarine Pests of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa L.). Agronomy, 15(12), 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122785