Temporary Intercropping as a Management Option for Increasing Plant Diversity in Southern Australian Cropping Systems: A Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

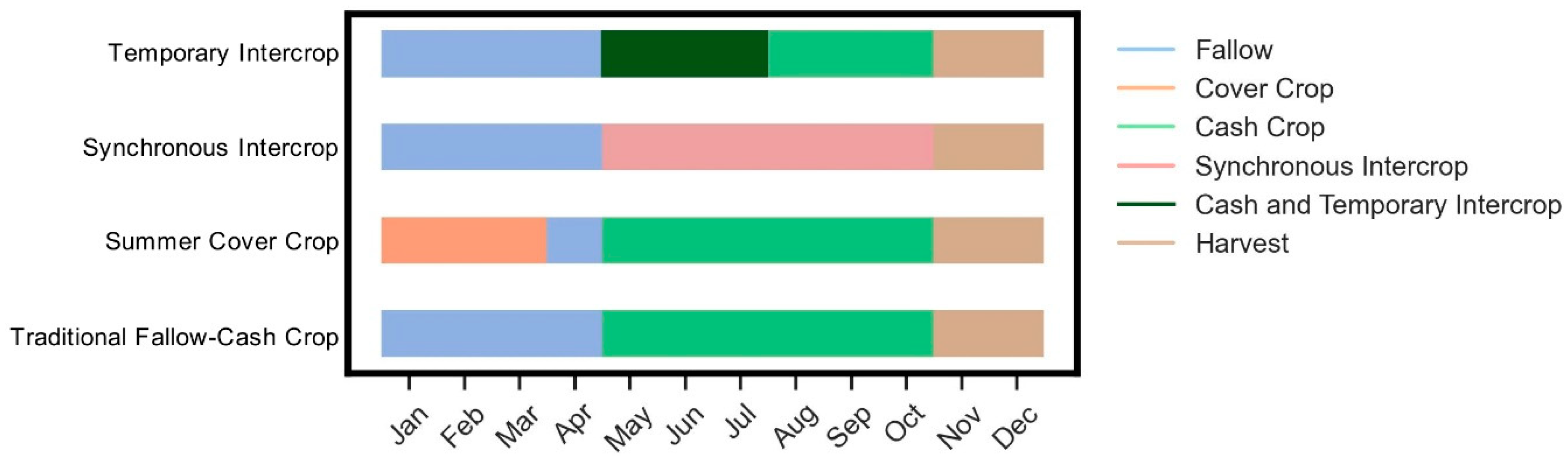

2. Options for Improving Plant Diversity in Southern Australian Cropping Systems

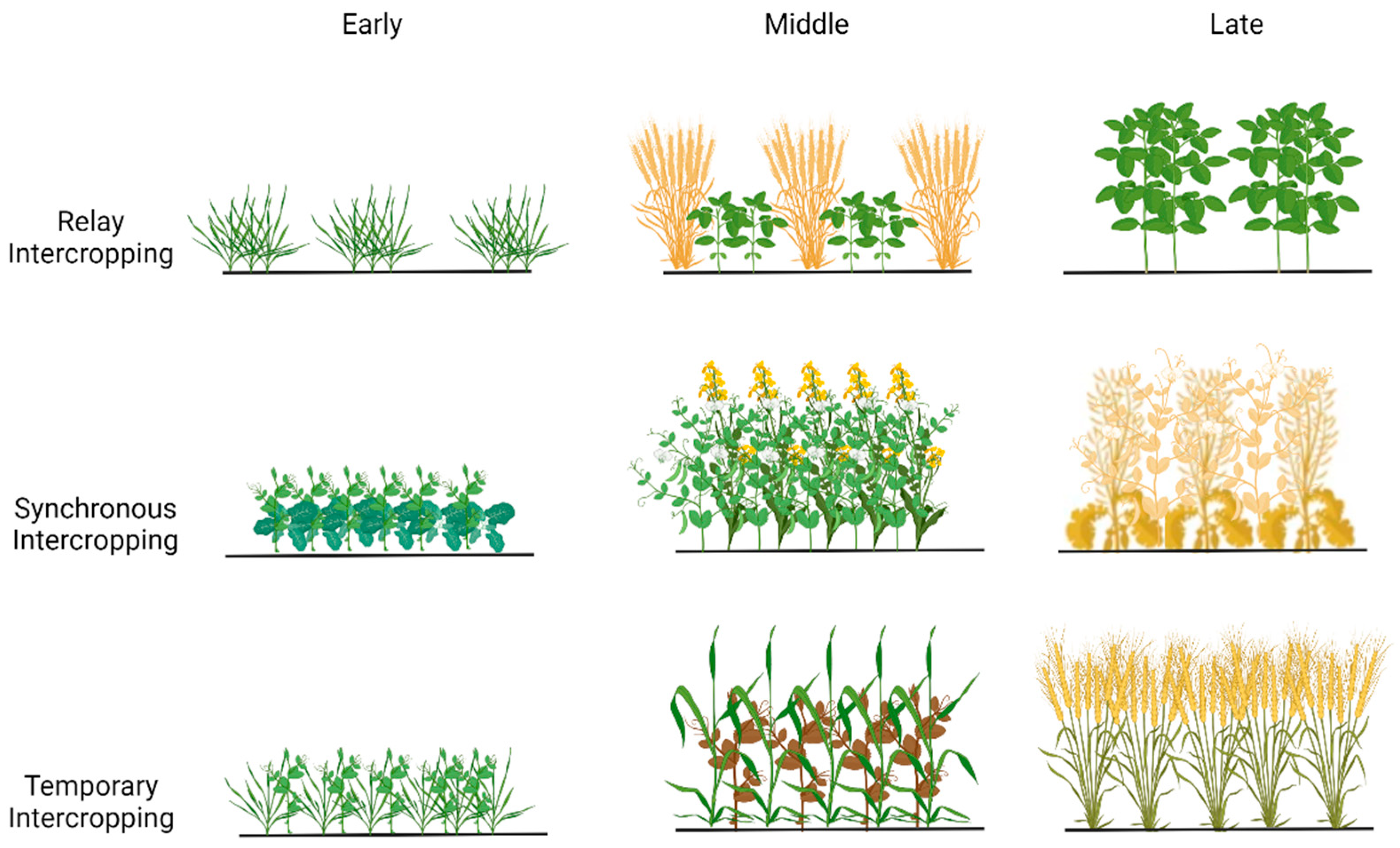

3. Intercropping and Challenges in Mechanised Farming Systems

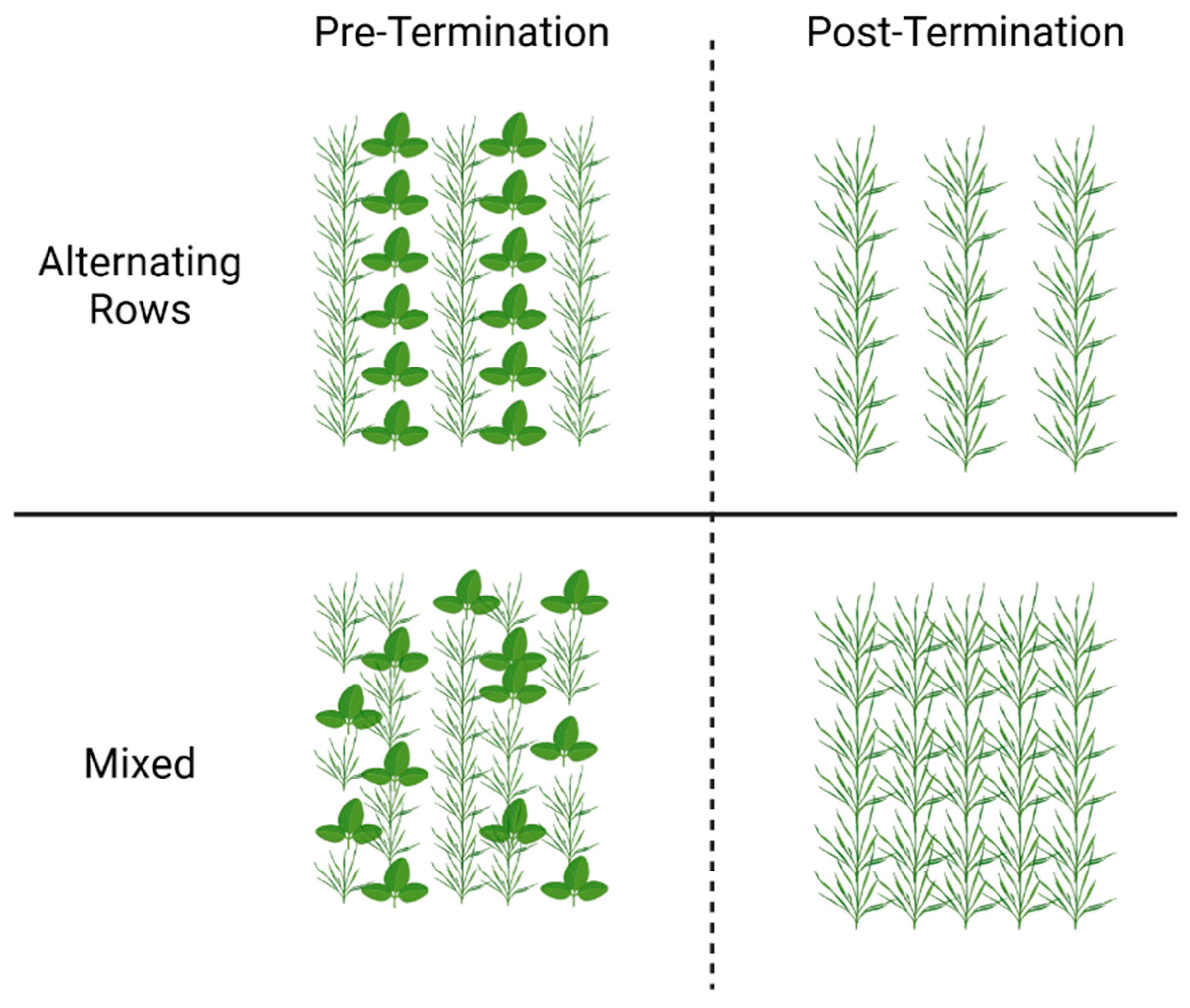

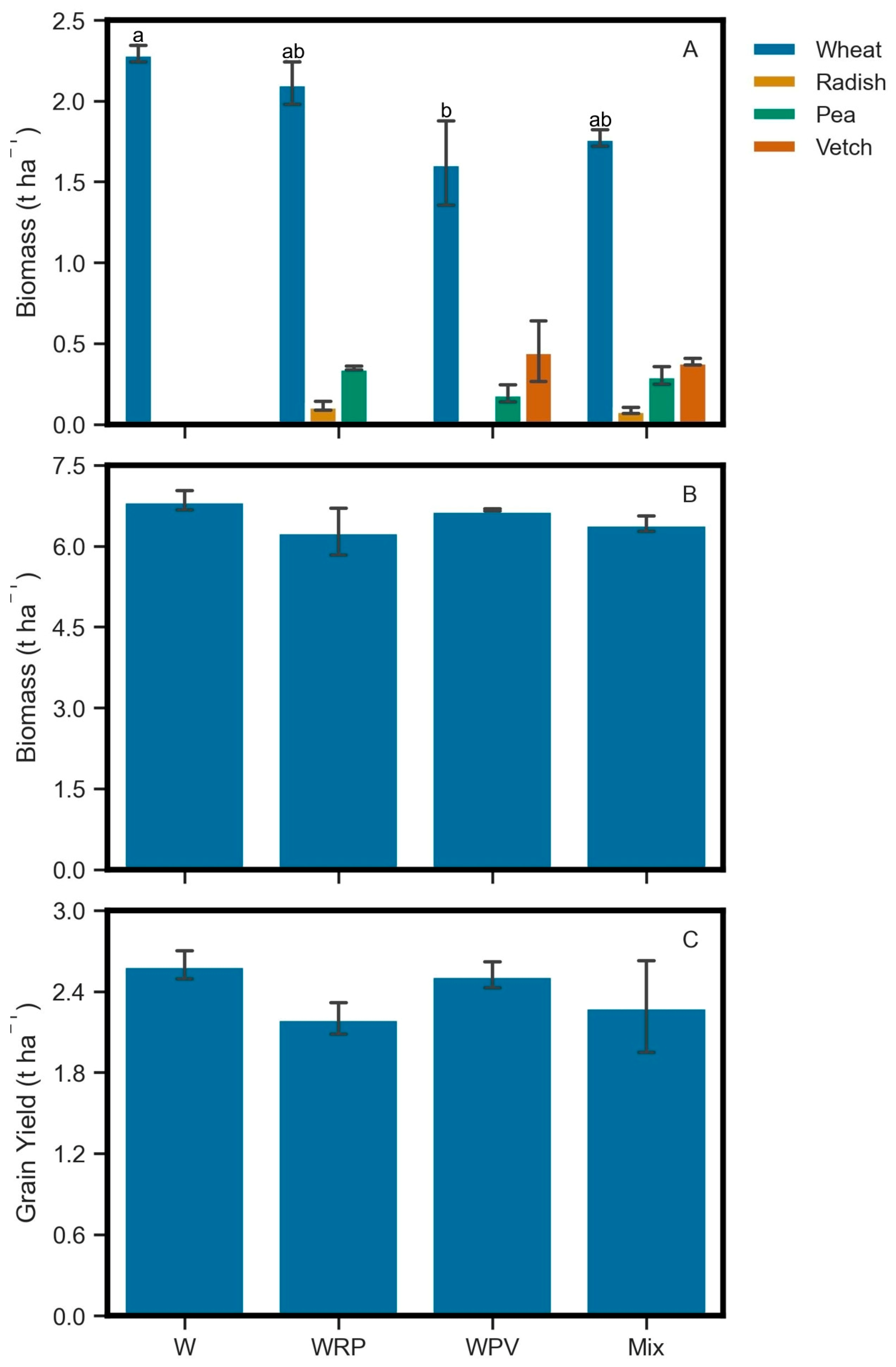

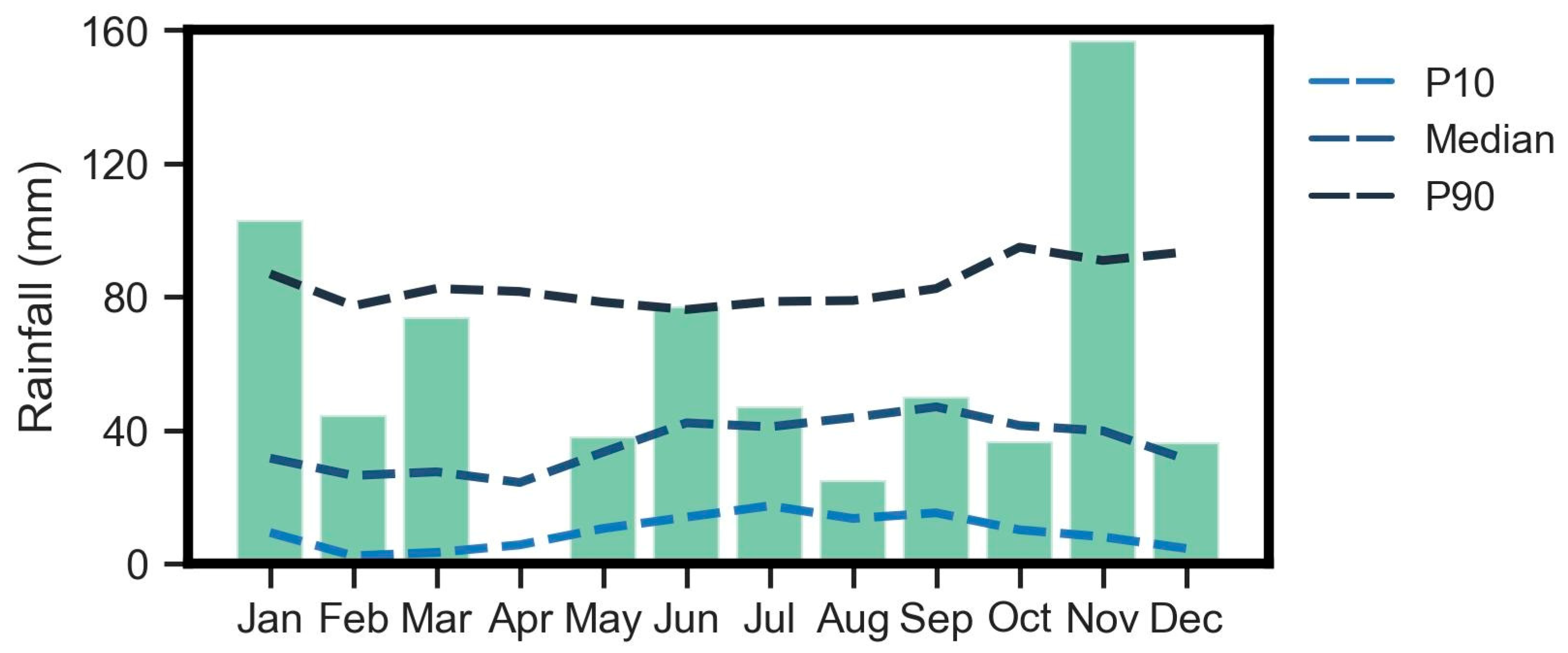

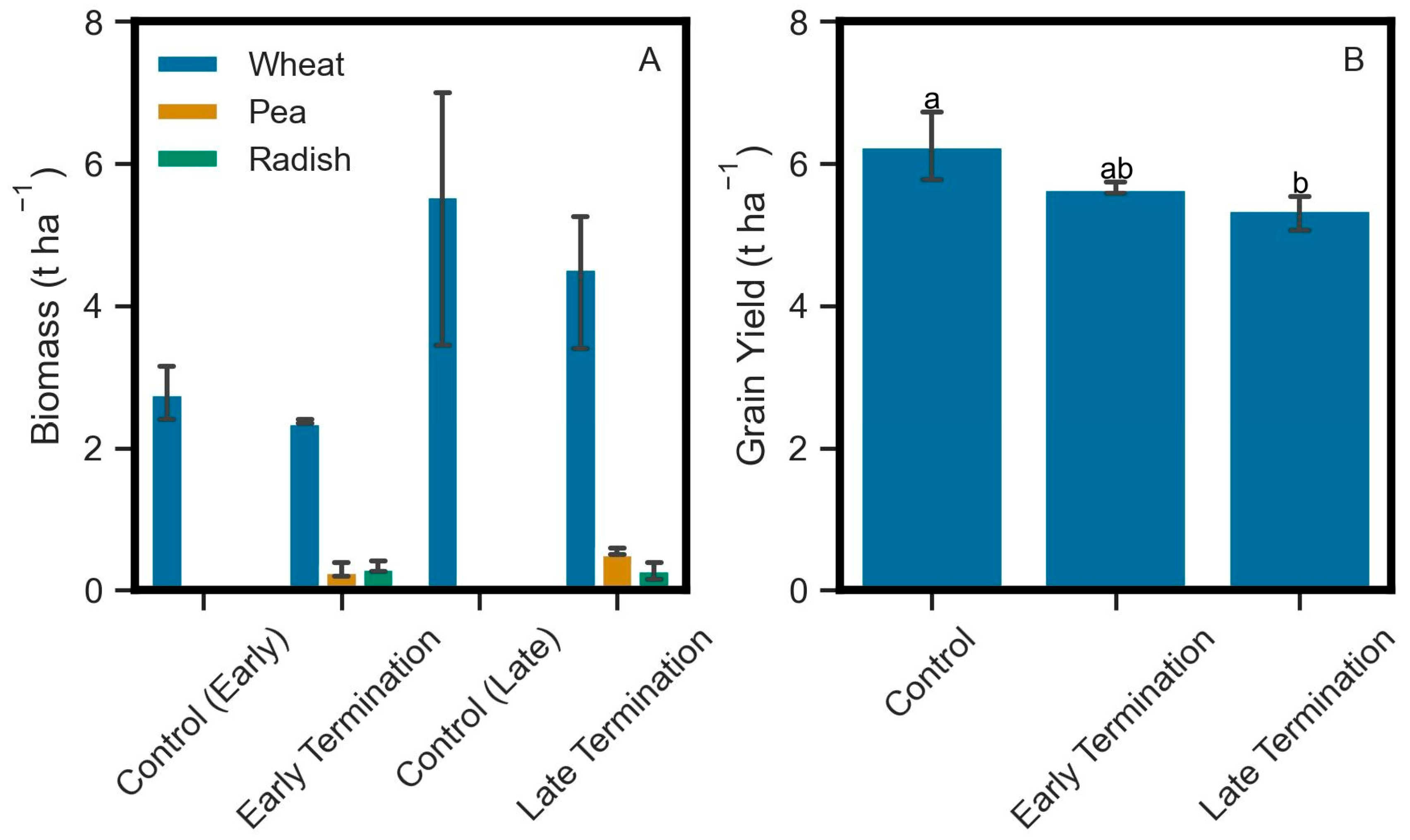

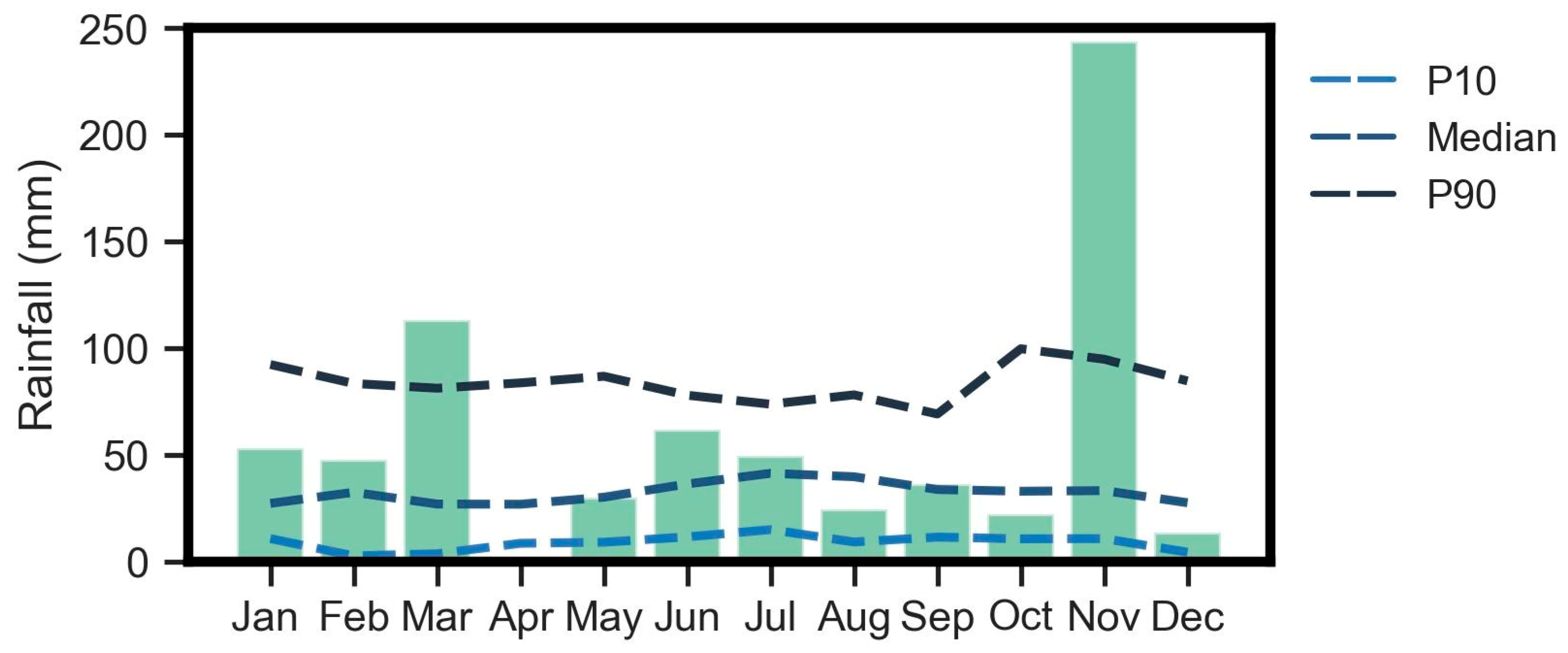

4. Temporary Intercropping and Ease of Integration into Farming Systems, Plus Potential Benefits

5. Ease of On-Farm Trialling of Temporary Intercropping

6. Future Research and Practicalities

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirkegaard, J.; van Rees, H. Evolution of conservation agriculture in winter rainfall areas. In Australian Agriculture in 2020: From Conservation to Automation; Pratley, J., Kirkegaard, J., Eds.; Agronomy Australia and Charles Sturt University: Wagga Wagga, Australia, 2019; Chapter 4; pp. 47–64. Available online: http://agronomyaustraliaproceedings.org/index.php/special-publications (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Armstrong, R.D.; Perris, R.; Munn, M.; Dunsford, K.; Robertson, F.; Hollaway, G.J.; Leary, G.J.O. Effects of long-term rotation and tillage practice on grain yield and protein of wheat and soil fertility on a Vertosol in a medium-rainfall temperate environment. Crop Pasture Sci. 2019, 70, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, M.; Flower, K.C.; Scanlan, C.A.; Rose, M.T.; Renton, M. Interactions between crop sequences, weed populations and herbicide use in Western Australian broadacre farms: Findings of a six-year survey. Crop Pasture Sci. 2020, 71, 491–505, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, A.D.; Goward, L.; Hunt, J.R.; Kirkegaard, J.A.; Peoples, M.B. Diverse systems and strategies to cost-effectively manage herbicide-resistant annual ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) in no-till wheat (Triticum aestivum) based cropping sequences in south-eastern Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 2023, 74, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.; Howieson, J.; Nutt, B.; Yates, R.; O’Hara, G.; Van Wyk, B.-E. A ley-farming system for marginal lands based upon a self-regenerating perennial pasture legume. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Moore, A. Whole farm implications of lucerne transitions in temperate crop-livestock systems. Agric. Syst. 2020, 177, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, F.; Adler, P.R.; Eisenhauer, N.; Fornara, D.; Kimmel, K.; Kremen, C.; Letourneau, D.K.; Liebman, M.; Polley, H.W.; Quijas, S.; et al. Benefits of increasing plant diversity in sustainable agroecosystems. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, S.L.; Domeignoz-Horta, L.A.; Loaiza, V.; Laine, A.-L. Plant biodiversity promotes sustainable agriculture directly and via belowground effects. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R.; Mirsky, S.B.; Tully, K.L. Cover crops reduce nitrate leaching in agroecosystems:A global meta-analysis. J. Environ. Qual. 2018, 47, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetunji, A.T.; Ncube, B.; Mulidzi, R.; Lewu, F.B. Management impact and benefit of cover crops on soil quality: A review. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 204, 104717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Abou Najm, M.; Steenwerth, K.L.; Nocco, M.A.; Basset, C.; Daccache, A. Are there universal soil responses to cover cropping? A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 861, 160600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, J.P.; Quemada, M. Using cover crops to mitigate and adapt to climate change. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.R.; Kirkegaard, J.A. Re-evaluating the contribution of summer fallow rain to wheat yield in southern Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 2011, 62, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, I.I.; Bell, L.W.; Williams, A. Cover crop legacy impacts on soil water and nitrogen dynamics, and on subsequent crop yields in drylands: A meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.R.; Browne, C.; McBeath, T.M.; Verburg, K.; Craig, S.; Whitbread, A.M. Summer fallow weed control and residue management impacts on winter crop yield though soil water and N accumulation in a winter-dominant, low rainfall region of southern Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 2013, 64, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.J.; Parvin, S.; Han, E.; Condon, J.; Flohr, B.M.; Schefe, C.; Rose, M.T.; Kirkegaard, J.A. Prospects for summer cover crops in southern Australian semi-arid cropping systems. Agric. Syst. 2022, 200, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNee, M.E.; Rose, T.J.; Minkey, D.M.; Flower, K.C. Effects of dryland summer cover crops and a weedy fallow on soil water, disease levels, wheat growth and grain yield in a Mediterranean-type environment. Field Crops Res. 2022, 280, 108472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.J.; Parvin, S.; McInnes, J.; van Zwieten, L.; Gibson, A.J.; Kearney, L.J.; Rose, M.T. Summer cover crop and temporary legume-cereal intercrop effects on soil microbial indicators, soil water and cash crop yields in a semi-arid environment. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, S.; Condon, J.; Rose, T. Rooting depth and water use of summer cover crops in a semi-arid cropping environment. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 147, 126847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, M.; Milroy, S.; Poole, M.L. Green and brown manures in dryland wheat production systems in mediterranean-type environments. Adv. Agron. 2012, 117, 275–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, E.; O’Connor, G.; Gaynor, L.; Ellis, S.; Coombes, N. Brown manuring pulses on acidic soils in southern NSW—Is it worth it? “Building Productive, Diverse and Sustainable Landscapes”. In Proceedings of the 17th ASA Conference, Hobart, Australia, 20–24 September 2015; Available online: www.agronomy2015.com.au (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Flower, K.C.; Cordingley, N.; Ward, P.R.; Weeks, C. Nitrogen, weed management and economics with cover crops in conservation agriculture in a Mediterranean climate. Field Crops Res. 2012, 132, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R.W.; Bennett, A.E.; Cong, W.-F.; Daniell, T.J.; George, T.S.; Hallett, P.D.; Hawes, C.; Iannetta, P.P.M.; Jones, H.G.; Karley, A.J.; et al. Improving intercropping: A synthesis of research in agronomy, plant physiology and ecology. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, A.; Sadras, V.; Roberts, P.; Doolette, A.; Zhou, Y.; Denton, M. Legume-oilseed intercropping in mechanised broadacre agriculture—A review. Field Crops Res. 2021, 260, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, L.E.; Barrett, G.W. A comparison of conventional and alternative agroecosystems using alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum). Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2005, 20, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridley, J.D. The Influence of species diversity on ecosystem productivity: How, where, and why? OIKOS 2001, 93, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betencourt, E.; Duputel, M.; Colomb, B.; Desclaux, D.; Hinsinger, P. Intercropping promotes the ability of durum wheat and chickpea to increase rhizosphere phosphorus availability in a low P soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Jensen, E.S. Facilitative root interactions in intercrops. Plant Soil 2005, 274, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aphalo, P.J.; Ballaré, C.L. On the importance of information-acquiring systems in plant–plant interactions. Funct. Ecol. 1995, 9, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.S. Grain yield, symbiotic N2 fixation and interspecific competition for inorganic N in pea-barley intercrops. Plant Soil 1996, 182, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malézieux, E.; Crozat, Y.; Dupraz, C.; Laurans, M.; Makowski, D.; Ozier-Lafontaine, H.; Rapidel, B.; de Tourdonnet, S.; Valantin-Morison, M. Mixing plant species in cropping systems: Concepts, tools and models. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardarin, A.; Celette, F.; Naudin, C.; Piva, G.; Valantin-Morison, M.; Vrignon-Brenas, S.; Verret, V.; Médiène, S. Intercropping with service crops provides multiple services in temperate arable systems: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, G.D.; Jones, R.E.; Michalk, D.L.; Brady, S. An exploratory tool for analysis of forage and livestock production options. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2009, 49, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithourgidis, A.S.; Dordas, C.A.; Damalas, C.A.; Vlachostergios, D.N. Annual intercrops: An alternative pathway for sustainable agriculture. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 396–410. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, U.; Stott, K.J.; Armstrong, R.; Nuttall, J.G.; Henry, F.; Christy, B.P.; Mitchell, M.; Riffkin, P.A.; Wallace, A.J.; McCaskill, M.; et al. Intercropping—Evaluating the advantages to broadacre systems. Agriculture 2021, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Bastiaans, L.; Anten, N.P.R.; Makowski, D.; van der Werf, W. Annual intercropping suppresses weeds: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verret, V.; Gardarin, A.; Pelzer, E.; Médiène, S.; Makowski, D.; Valantin-Morison, M. Can legume companion plants control weeds without decreasing crop yield? A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2017, 204, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, G. Influence of white clover traits on biomass and yield in winter wheat- or winter oilseed rape-clover intercrops. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2003, 21, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, G.; Stenberg, M.; Wetterlind, J.; Båth, B.; Elfstrand, S. Clover cover crops under-sown in winter wheat increase yield of subsequent spring barley—Effect of N dose and companion grass. Field Crops Res. 2011, 120, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.V.; Pereira, L.C.R.; De Almeida, L.; Williams, R.L.; Freach, J.; Nesbitt, H.; Erskine, W. Maize-mucuna (Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC) relay intercropping in the lowland tropics of Timor-Leste. Field Crops Res. 2014, 156, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, O.A.; Zhou, X.M.; Cloutier, D.; Coulman, D.C.; Faris, M.A.; Smith, D.L. Cover crops and interrow tillage for weed control in short season maize (Zea mays). Eur. J. Agron. 2000, 12, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, R.L.; Sheaffer, C.C.; Barnes, D.K. Effect of annual medic smother plants on weed control and yield in corn. Agron. J. 1997, 89, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.; Kirkegaard, J.; Peoples, M.B.; Robertson, M.; Whish, J.; Swan, A. Prospects to utilise intercrops and crop variety mixtures in mechanised, rain-fed, temperate cropping systems. Crop Pasture Sci. 2016, 67, 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, K.J.; Wallace, A.J.; Khanal, U.; Christy, B.P.; Mitchell, M.L.; Riffkin, P.A.; McCaskill, M.R.; Henry, F.J.; May, M.D.; Nuttall, J.G.; et al. Intercropping—Towards an understanding of the productivity and profitability of dryland crop mixtures in southern australia. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.; McNee, M.; Ogden, G.; Robertson, M. The residual N benefits of temporary intercropping field pea with wheat. In Proceedings of the 17th ASA Conference, Hobart, Australia, 20–24 September 2015; pp. 987–990. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, W.S.; Hoover, R.J.; Mirsky, S.B.; Roth, G.W.; Ryan, M.R.; Ackroyd, V.J.; Wallace, J.M.; Dempsey, M.A.; Pelzer, C.J. Evaluation of cover crops drill interseeded into corn across the mid-Atlantic region. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefanis, E.; Sgrulletta, D.; Pucciarmati, S.; Ciccoritti, R.; Quaranta, F. Influence of durum wheat-faba bean intercrop on specific quality traits of organic durum wheat. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2017, 33, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, F.; Carlesi, S.; Nardi, G.; Bàrberi, P. Wheat–clover temporary intercropping under Mediterranean conditions affects wheat biomass, plant nitrogen dynamics and grain quality. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 130, 126347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiducci, M.; Tosti, G.; Falcinelli, B.; Benincasa, P. Sustainable management of nitrogen nutrition in winter wheat through temporary intercropping with legumes. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, G.; Guiducci, M. Durum wheat–faba bean temporary intercropping: Effects on nitrogen supply and wheat quality. Eur. J. Agron. 2010, 33, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, S.; Bajwa, A.; Uddin, S.; Sandral, G.; Rose, M.T.; Van Zwieten, L.; Rose, T.J. Impact of wheat-vetch temporary intercropping on soil functions and grain yield in a dryland semi-arid environment. Plant Soil 2023, 506, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendiburu, F. R Package, Version 1.3-7. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R foundation for statistical computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

| Source | Country | Cereal Component | Legume Component | Termination Method | Termination Timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rose et al. [18] | Australia | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Vetch (Vicia sativa), subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum) | Herbicide | 17 weeks post-sowing |

| Parvin et al. [51] | Australia | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Vetch (Vicia sativa) | Herbicide | 9 weeks post sowing |

| Tosti and Guiducci [50] | Italy | Durum wheat (Triticum durum) | Faba bean (Vicia faba) | Cultivation | 21 weeks post sowing |

| Guiducci et al. [49] | Italy | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Faba bean (Vicia faba), peas (Pisum sativum), Squarrose clover (Trifolium squarrosum) | Cultivation | 21 weeks post sowing |

| De Stafanis et al. [47] | Italy | Durum wheat (Triticum durum) | Faba bean (Vicia faba) | Cultivation | 21 weeks post sowing |

| Pellegrini et al. [48] | Italy | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Persian clover (Trifolium resupinatum) | Cultivation | 18 weeks post sowing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thompson, H.; Condon, J.; Gibson, A.J.; Parvin, S.; Rose, T.J. Temporary Intercropping as a Management Option for Increasing Plant Diversity in Southern Australian Cropping Systems: A Perspective. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122784

Thompson H, Condon J, Gibson AJ, Parvin S, Rose TJ. Temporary Intercropping as a Management Option for Increasing Plant Diversity in Southern Australian Cropping Systems: A Perspective. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122784

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Hayden, Jason Condon, Abraham J. Gibson, Shahnaj Parvin, and Terry J. Rose. 2025. "Temporary Intercropping as a Management Option for Increasing Plant Diversity in Southern Australian Cropping Systems: A Perspective" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122784

APA StyleThompson, H., Condon, J., Gibson, A. J., Parvin, S., & Rose, T. J. (2025). Temporary Intercropping as a Management Option for Increasing Plant Diversity in Southern Australian Cropping Systems: A Perspective. Agronomy, 15(12), 2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122784