Greenhouse Irrigation Control Based on Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

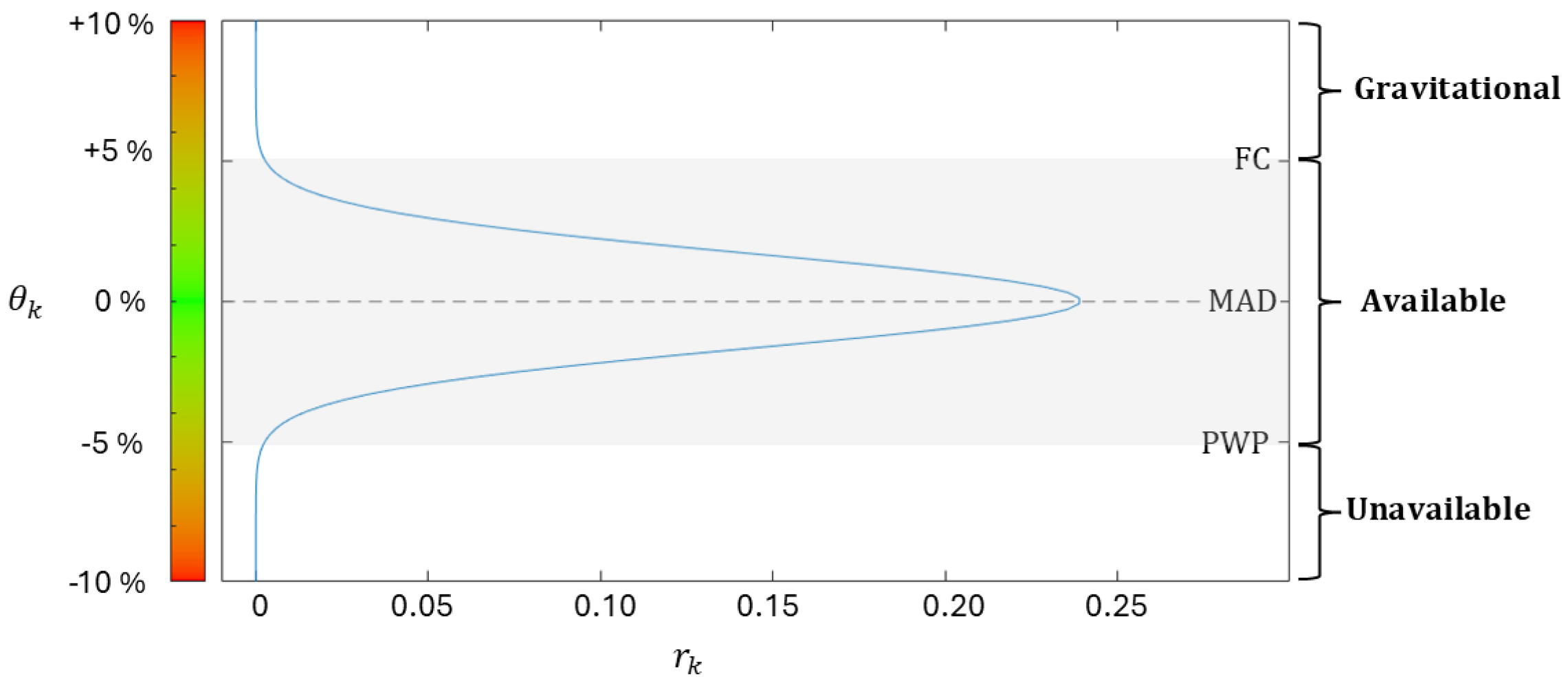

2.1. Crop Irrigation Dynamics

- Gravitational: Soil is oversaturated with water, waterlogging may be visibly present in the crop, and the water drains quickly due to gravity.

- Available water: In this region, water is available for crop roots. This region is delimited by the field-capacity (FC) and the permanent-wilting-point (PWP) thresholds.

- Unavailable water: In this region, water is not available to crops, and plants suffer from severe water stress.

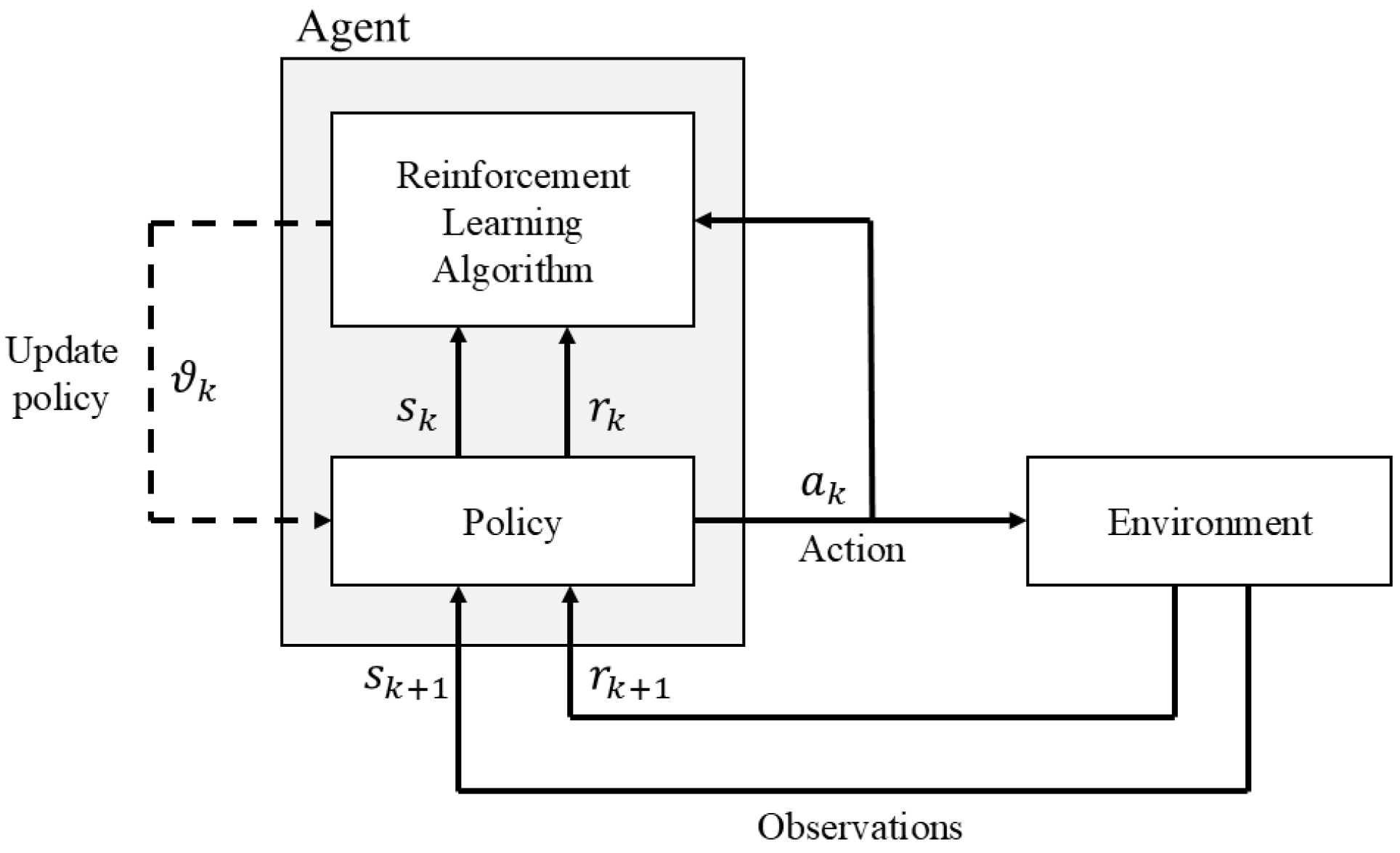

2.2. Reinforcement Learning Control

2.3. Advantage Actor–Critic Algorithm

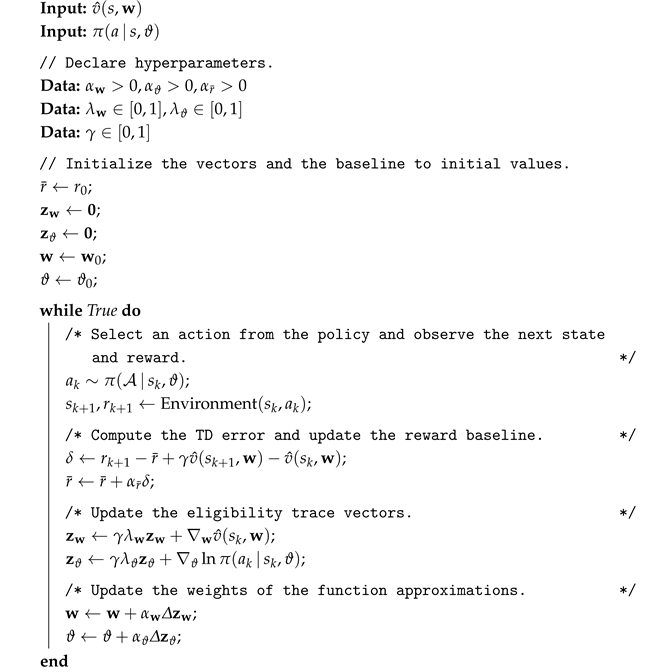

| Algorithm 1: Advantage actor–critic with eligibility traces algorithm |

|

3. Results

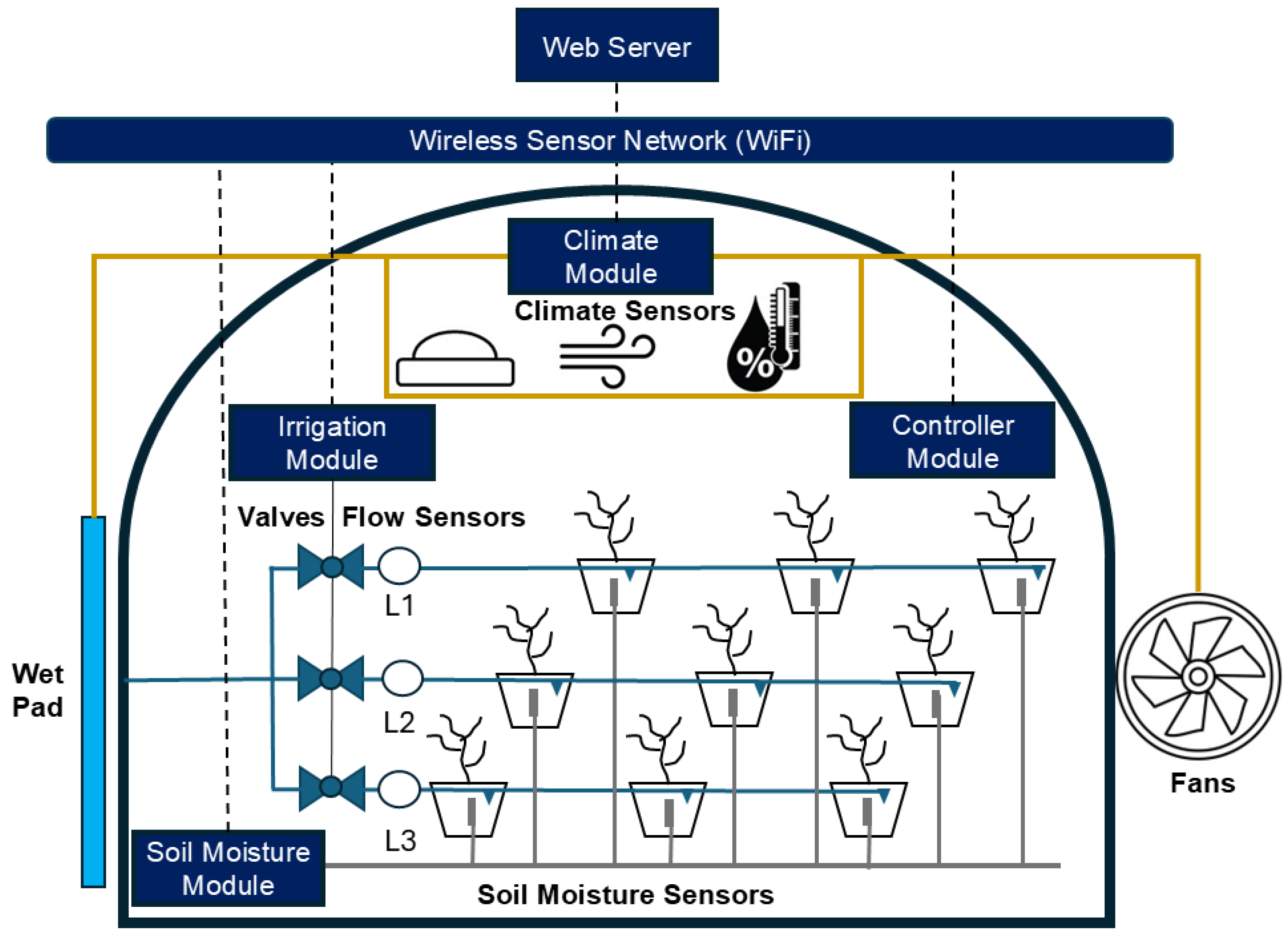

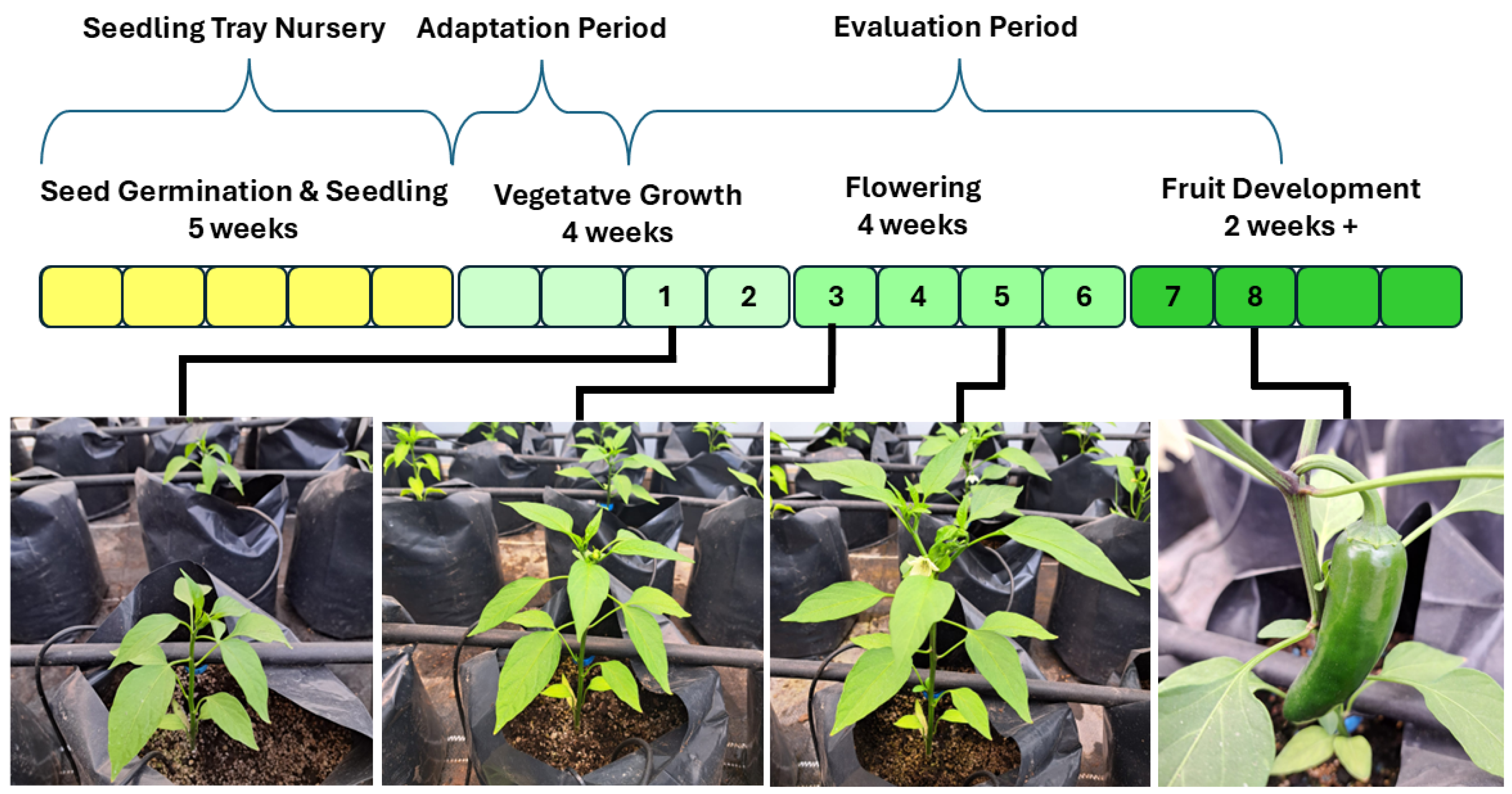

3.1. Experimental Setup

- Soil-moisture module: Nine soil-moisture sensors ECH2O EC-5 (METER Group Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) were deployed to measure the volumetric water content, with three sensors assigned to representative plants on each irrigation line. Data acquisition was carried out using an ESP32 microcontroller (Espressif Systems, Shanghai, China), which enabled real-time monitoring and integration with the irrigation control system.

- Irrigation module: This module manages the actuation of the three irrigation electrovalves and measures the corresponding water flow using YF-S201 sensors (Digiten, Shenzhen, China). The system is implemented on an ESP32 microcontroller, which enables precise valve control, flow-data acquisition, and integration with the overall irrigation management framework.

- Climate module: The climate monitoring module integrates three sensors: a solar-radiation PYR sensor (Apogee Instruments, Logan, UT, USA), a Davis Cup wind-speed sensor (Davis Instruments Corp., Hayward, CA, USA), and a combined Atmos 14 air temperature–relative humidity sensor (METER Group Inc., Pullman, WA, USA). In addition to data acquisition, the module controls the wet-pad pump and the extraction fans to regulate greenhouse climate conditions. The system is implemented on an ESP32 microcontroller, providing both sensor integration and actuator management within a unified platform.

- Controller module: The module executes the three evaluated irrigation control algorithms: (1) time-based control, (2) on–off control, and (3) reinforcement learning-based control. It is implemented on a Raspberry Pi 4 single-board computer (Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK), running Python 3.12 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA), providing sufficient computational resources for real-time algorithm execution, data processing, and integration with the greenhouse monitoring and actuation systems.

- Wireless sensor network: A WiFi communication network is established using a publish–subscribe messaging model implemented via the MQTT protocol (OASIS Open, Burlington, MA, USA), a standard widely used in IoT (Internet-of-Things) applications. This lightweight and flexible protocol enables real-time, asynchronous data exchange between all modules, allowing any device to transmit or receive information at any time with minimal overhead.

- Web server: A computer hosts Node-RED v3.1.6 services (OpenJS Foundation, San Francisco, CA, USA), providing a web-based interface that allows users to monitor and interact with the greenhouse systems in real time. This platform enables intuitive visualization, data logging, and system setup through a graphical, browser-accessible dashboard.

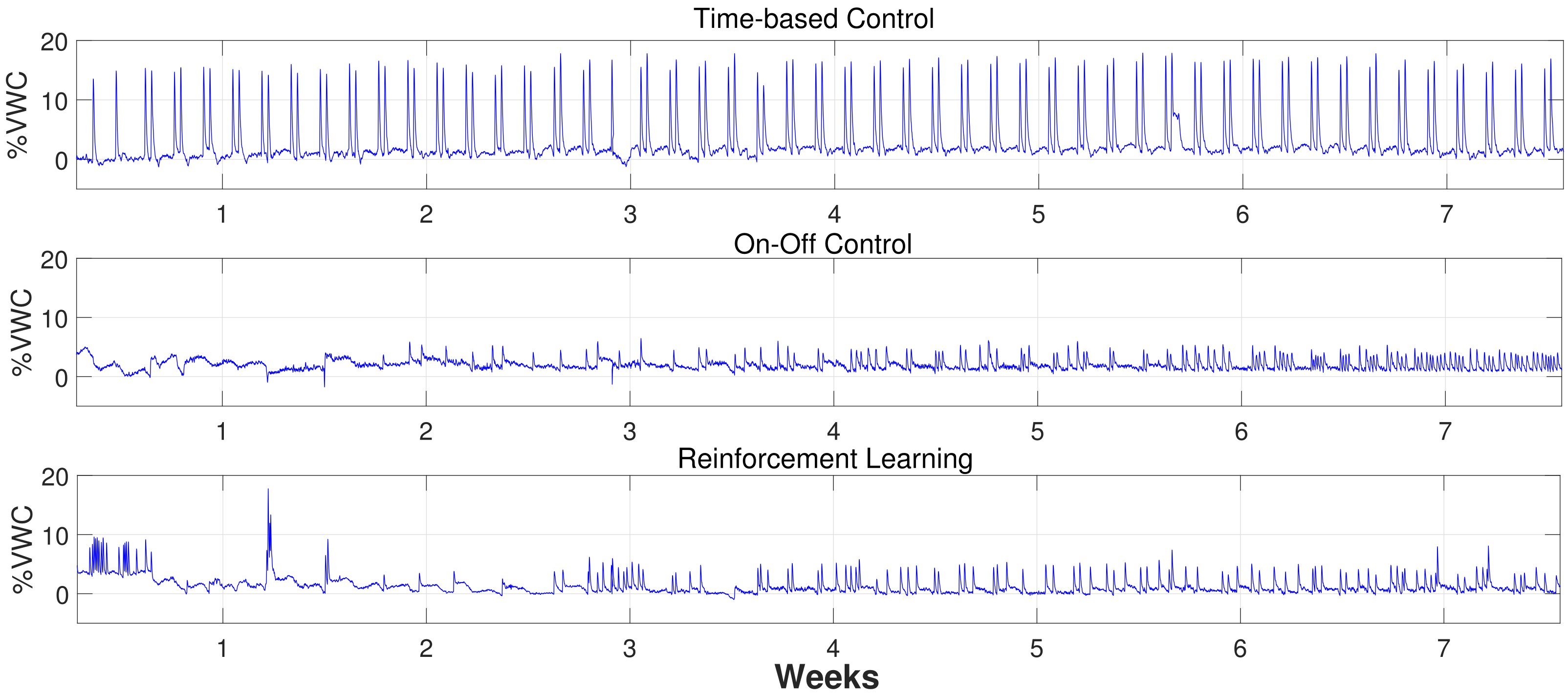

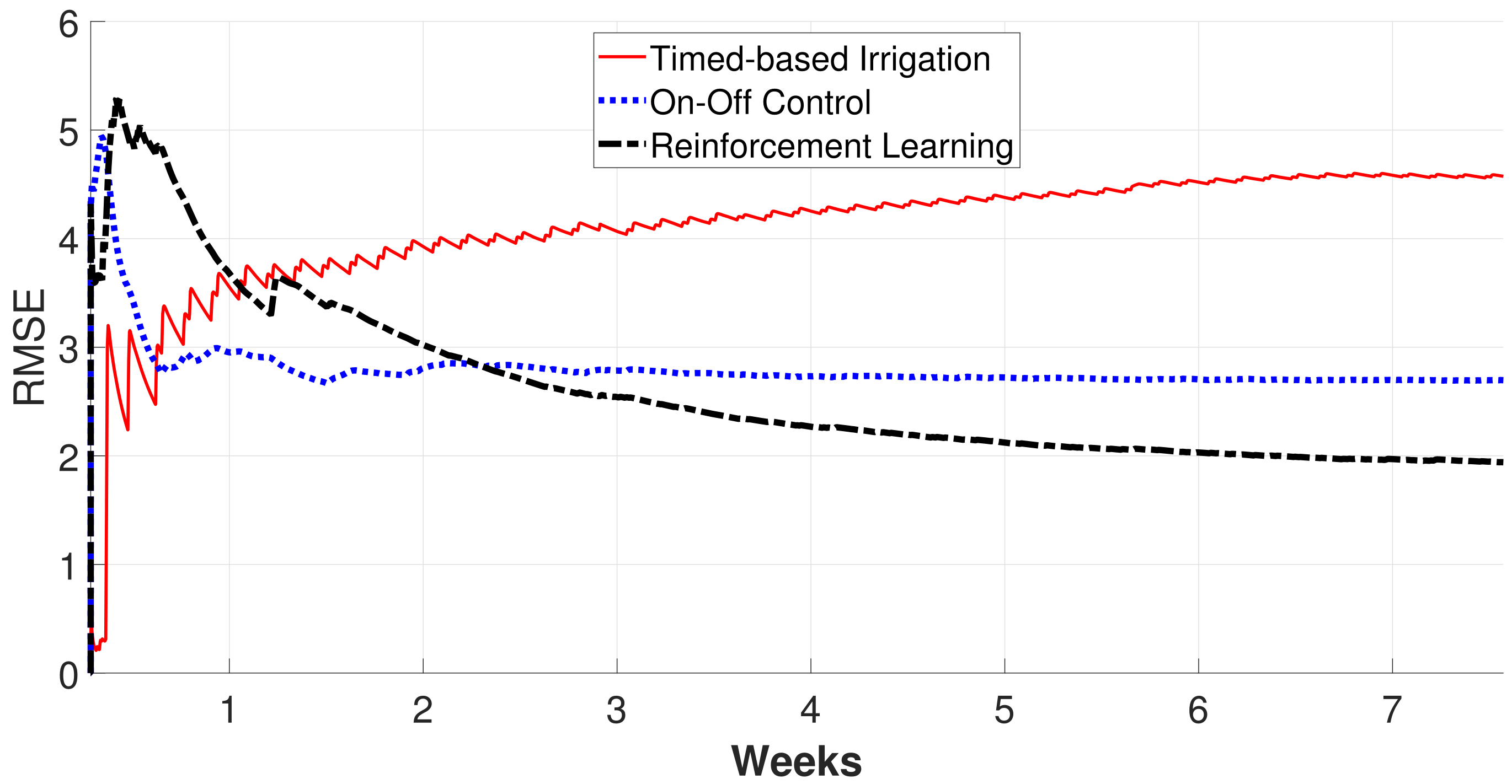

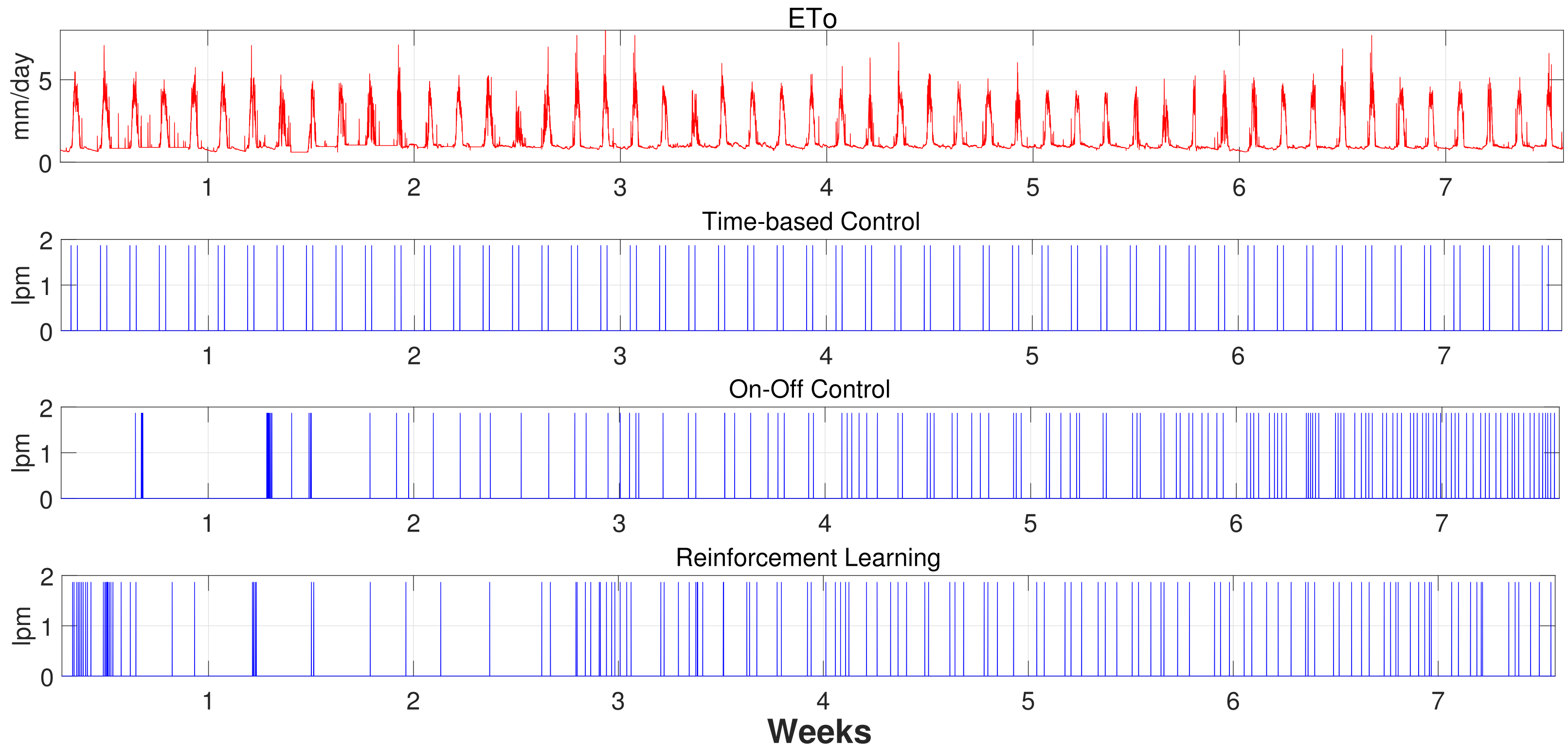

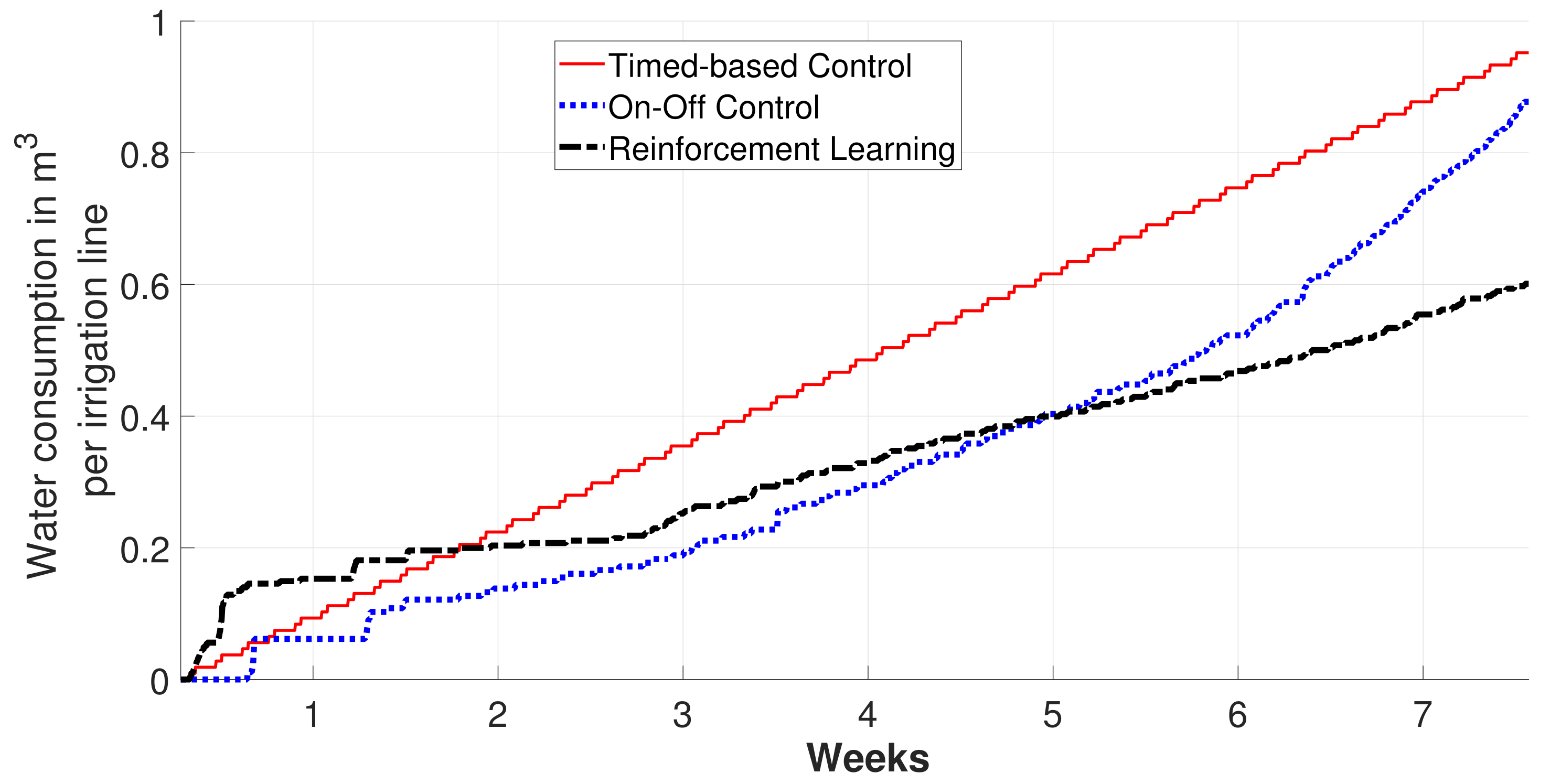

3.2. Experimental Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A2C | Advantage Actor–Critic |

| FC | Field Capacity |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MAD | Maximum Allowable Depletion |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| MQTT | Message-Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| PWP | Permanent Wilting Point |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| TD | Temporal Difference |

| VWC | Volumetric Water Content |

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Leveraging Automation in Agriculture for Transforming Agrifood Systems; Technical Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Amarillo, C.A.; Corrales-Muñoz, J.C.; Mendoza-Moreno, M.A.; Amarillo, A.M.G.; Hussein, A.F.; Arunkumar, N.; Ramirez-González, G. An IoT-Based Traceability System for Greenhouse Seedling Crops. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 67528–67535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwambale, E.; Abagale, F.K.; Anornu, G.K. Data-Driven Modelling of Soil Moisture Dynamics for Smart Irrigation Scheduling. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 5, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, B.T.; Naouri, M.; Appels, W.M.; Liu, J.; Shah, S.L. Learning-based multi-agent MPC for irrigation scheduling. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 147, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, E.A.; Abidin, M.S.Z.; Mahmud, M.S.A.; Buyamin, S.; Ishak, M.H.I.; Rahman, M.K.I.A.; Otuoze, A.O.; Onotu, P.; Ramli, M.S.A. A review on monitoring and advanced control strategies for precision irrigation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T.; Foster, T.; Schultz, D.M. Assessing the value of deep reinforcement learning for irrigation scheduling. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.J.; Hamann, H.F.; Hinds, N.; Guha, S.; Sanchez, L.; Sams, B.; Dokoozlian, N. Closed Loop Controlled Precision Irrigation Sensor Network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 4580–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Muriel, J.; García, I.; Muñoz de la Peña, D. Research on automatic irrigation control: State of the art and recent results. Agric. Water Manag. 2012, 114, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozoya, C.; Mendoza, C.; Aguilar, A.; Román, A.; Castelló, R. Sensor-based model driven control strategy for precision irrigation. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 9784071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, B.T.; Sahoo, S.R.; Liu, J.; Shah, S.L. LSTM-based model predictive control with discrete actuators for irrigation scheduling. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, G.B.; Ferramosca, A.; Gata, P.M.; Martín, M.P. Model Predictive Control Structures for Periodic ON–OFF Irrigation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 51985–51996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwambale, E.; Abagale, F.K.; Anornu, G.K. Smart irrigation monitoring and control strategies for improving water use efficiency in precision agriculture: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, O.; Grove, I.; Peets, S.; Domun, Y.; Norton, T. Dynamic Neural Network Modelling of Soil Moisture Content for Predictive Irrigation Scheduling. Sensors 2018, 18, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Zhu, T.; Jiao, X.; Xu, J.; Qi, Z. Neural network soil moisture model for irrigation scheduling. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, G.; Prati, R.C. Comparing modern and traditional modeling methods for predicting soil moisture in IoT-based irrigation systems. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Jain, A.; Gupta, P.; Chowdary, V. Machine Learning Applications for Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 4843–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umutoni, L.; Samadi, V. Application of machine learning approaches in supporting irrigation decision making: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 294, 108710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Wang, X. A smart agriculture IoT system based on deep reinforcement learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 99, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cui, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Liu, F.; Luo, T.; Zheng, S.; Luo, Y. A reinforcement learning approach to irrigation decision-making for rice using weather forecasts. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 250, 106838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagekar, A.; You, F. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Automatic Control in Semi-Closed Greenhouse Systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, X.; Luo, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Greenhouse Climate Control. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Knowledge Graph (ICKG), Nanjing, China, 9–11 August 2020; pp. 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Yao, Y.; An, Z.; Xiao, X.; Luo, D. Robust model-based reinforcement learning for autonomous greenhouse control. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 17–19 November 2021; pp. 1208–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenits, G.; Mallinger, K.; Raubitzek, S.; Neubauer, T. Current applications and potential future directions of reinforcement learning-based Digital Twins in agriculture. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Du, W. Poster Abstract: Smart Irrigation Control Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 21st ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN), Milano, Italy, 4–6 May 2022; pp. 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N. Intelligent control of agricultural irrigation based on reinforcement learning. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1601, 052031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; Porter, D.; Marek, T.; Hillyer, C. Reinforcement Learning Control for Water-Efficient Agricultural Irrigation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing with Applications and 2017 IEEE International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications (ISPA/IUCC), Guangzhou, China, 12–15 December 2017; pp. 1334–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Du, W. Optimizing irrigation efficiency using deep reinforcement learning in the field. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2024, 20, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Tang, J.; Abu Talip, M.S.; Aridas, N.K.; Guan, B. Reinforcement learning control method for greenhouse vegetable irrigation driven by dynamic clipping and negative incentive mechanism. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1632431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotarelli, L.; Dukes, M.D.; Romero, C.C.; Migliaccio, K.W.; Morgan, K.T. Step by Step Calculation of the Penman-Monteith Evapotranspiration (FAO-56 Method): AE459, 2/2010. EDIS. Available online: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AE/AE45900.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Lozoya, C.; Mendoza, G.; Mendoza, C.; Torres, V.; Grado, M. Experimental evaluation of data aggregation methods applied to soil moisture measurements. In Proceedings of the SENSORS, 2014 IEEE, Valencia, Spain, 2–5 November 2014; pp. 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.D.; Lozoya, C.; Castañeda, H.; Favela-Contreras, A. A discrete sliding mode control strategy for precision agriculture irrigation management. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 309, 109315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998; M-56. [Google Scholar]

- Lozoya, C.; Favela-Contreras, A.; Aguilar-Gonzalez, A.; Orona, L. A Precision Irrigation Model Using Hybrid Automata. Trans. Asabe 2019, 62, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Du, T.; Qiu, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, L.; Kang, S. Improved water use efficiency and fruit quality of greenhouse crops under regulated deficit irrigation in northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 179, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incrocci, L.; Thompson, R.B.; Fernandez-Fernandez, M.D.; De Pascale, S.; Pardossi, A.; Stanghellini, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Gallardo, M. Irrigation management of European greenhouse vegetable crops. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 242, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, G.; Neocleous, D.; Katsoulas, N.; Kittas, C. Irrigation of Greenhouse Crops. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value/Range | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate composition | 1:1:1 (v/v/v) | Loamy soil: peat moss: perlite |

| Total porosity | 65–75% | Typical range for greenhouse |

| horticultural media | ||

| Water-holding capacity | 45–55% | Volume of water retained at |

| container capacity | ||

| Air-filled porosity | 15–25% | Air volume after drainage |

| Container volume | 8 L | Common volume for pepper |

| per plant | in greenhouse cultivation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Padilla-Nates, J.P.; Garcia, L.D.; Lozoya, C.; Orona, L.; Cortes-Perez, A. Greenhouse Irrigation Control Based on Reinforcement Learning. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122781

Padilla-Nates JP, Garcia LD, Lozoya C, Orona L, Cortes-Perez A. Greenhouse Irrigation Control Based on Reinforcement Learning. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122781

Chicago/Turabian StylePadilla-Nates, Juan Pablo, Leonardo D. Garcia, Camilo Lozoya, Luis Orona, and Aldo Cortes-Perez. 2025. "Greenhouse Irrigation Control Based on Reinforcement Learning" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122781

APA StylePadilla-Nates, J. P., Garcia, L. D., Lozoya, C., Orona, L., & Cortes-Perez, A. (2025). Greenhouse Irrigation Control Based on Reinforcement Learning. Agronomy, 15(12), 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122781