Overcoming the Yield-Survival Trade-Off in Cereals: An Integrated Framework for Drought Resilience

Abstract

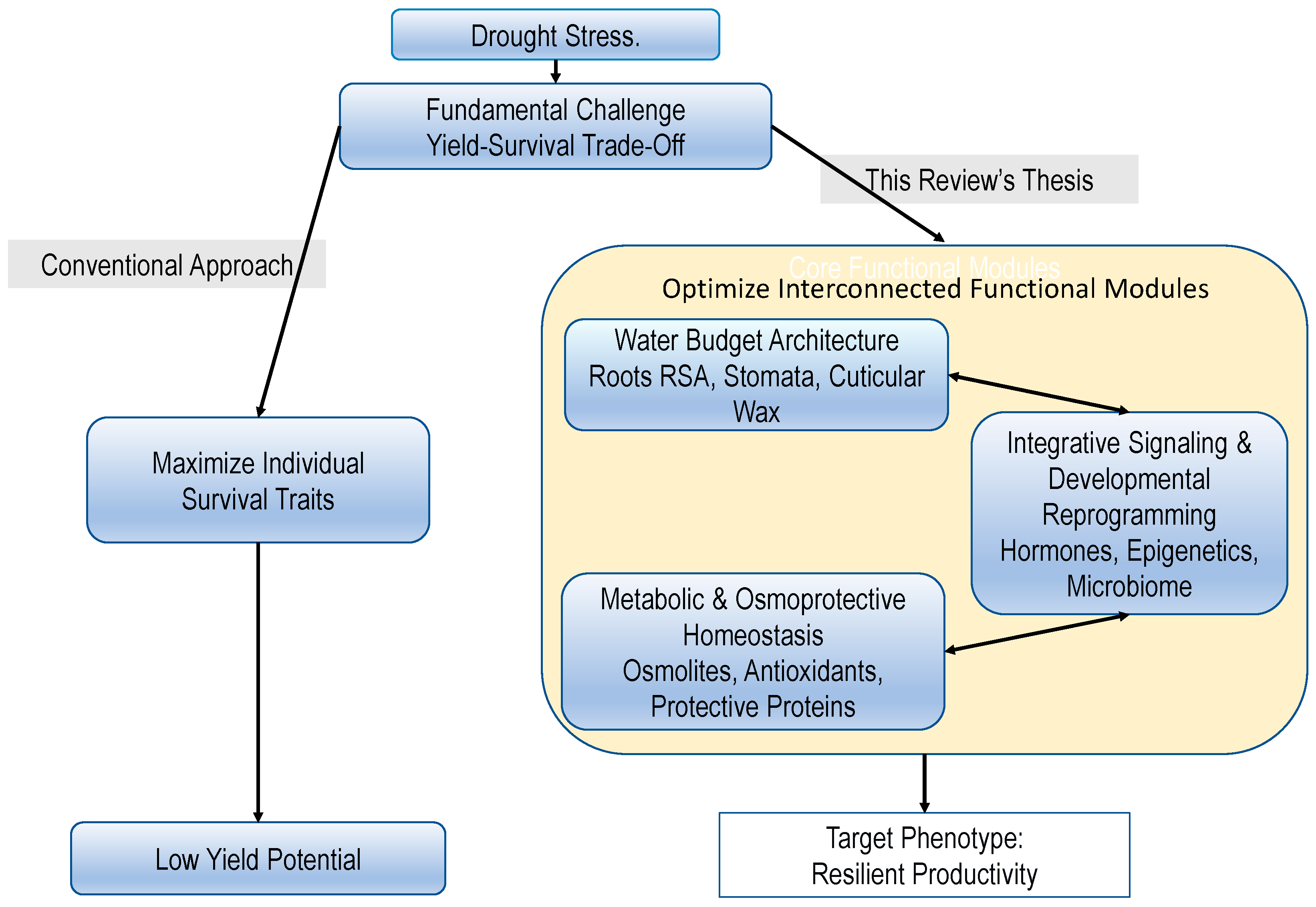

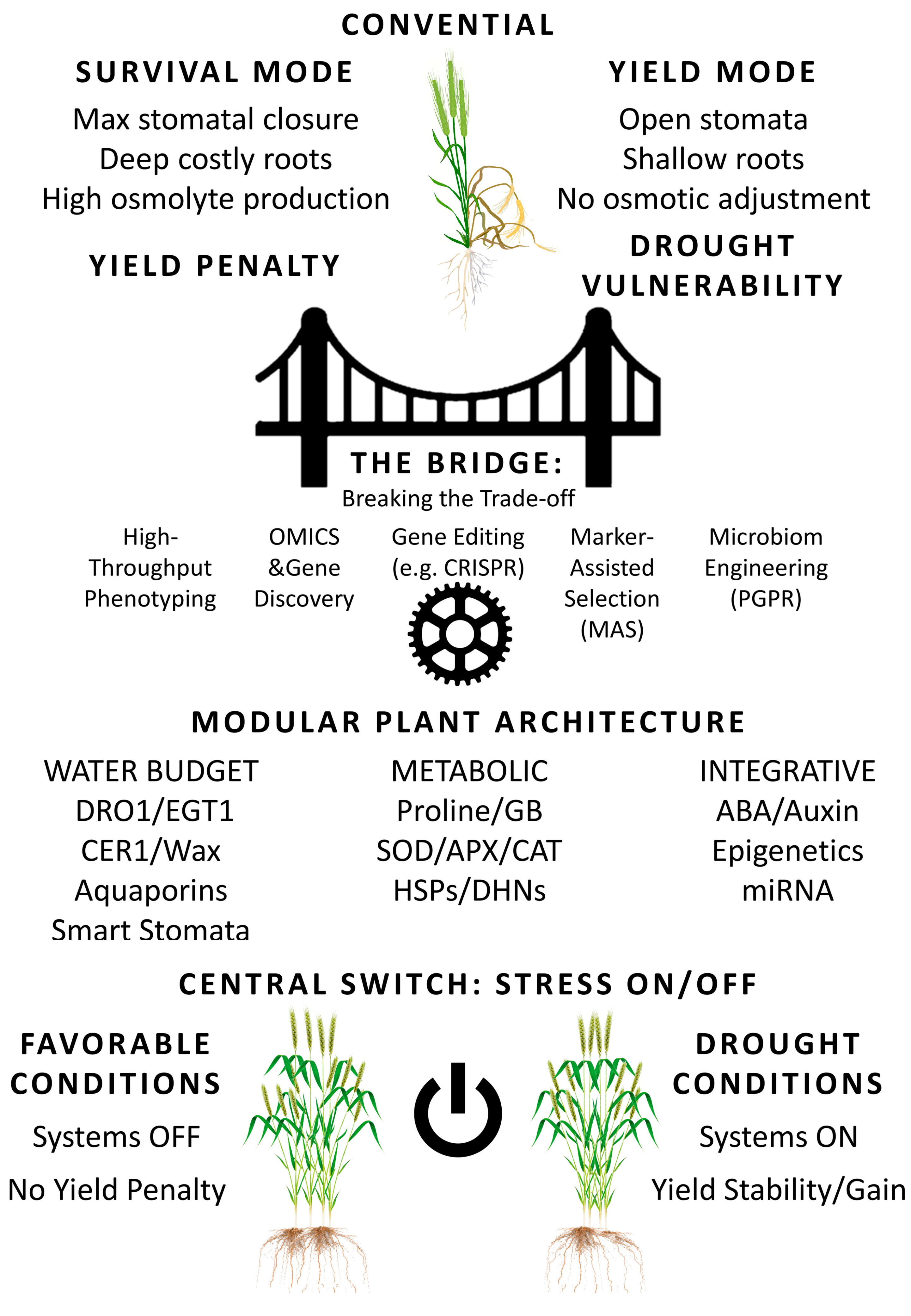

1. Introduction

2. Optimizing the Water Budget: Root System Architecture and Transpiration Control

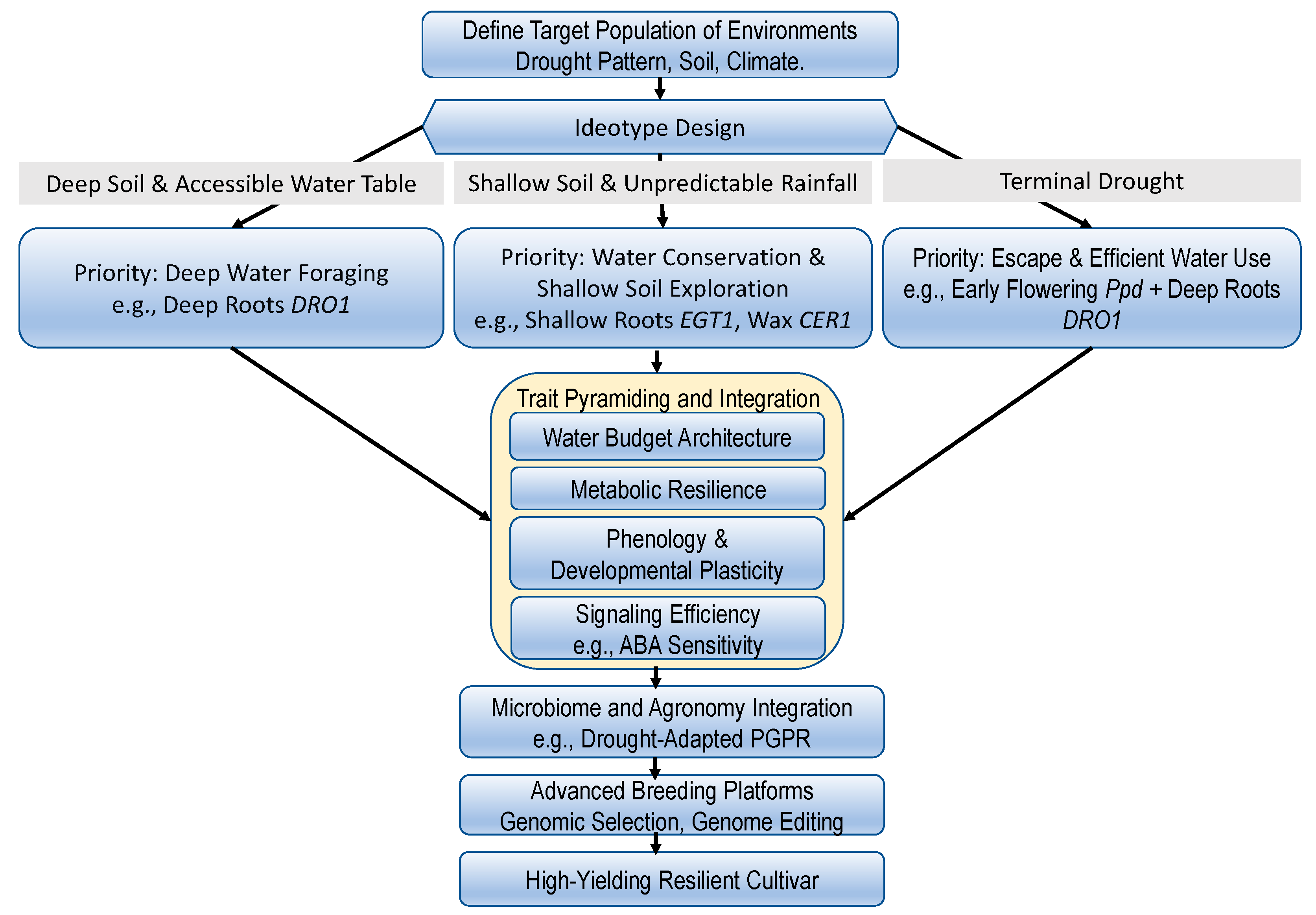

2.1. Root System Architecture as the Foundation of Water Foraging

2.2. Transpiration Control: From Stomata to Cuticle

- Rapid Stomatal Responses

Leaf Morphological Adaptations

2.3. Integration for Water Budget and Morphological Traits

3. Metabolic Resilience: Sustaining Productivity Under Stress

3.1. Osmotic Adjustment: The Role of Compatible Solutes

3.2. Antioxidant Defense: Managing Oxidative Stress

3.3. Protective Proteins and Metabolic Reprogramming

3.4. Breeding for Metabolic Efficiency

4. Integration and Reprogramming: Phytohormones as Conductors of the Stress Response

4.1. ABA: The Central Stress Signaling Hub

4.2. Hormonal Crosstalk: Fine-Tuning the Stress Response

4.3. Epigenetic Regulation: A Cereal-Specific Mechanism for Stress Memory and Breeding

4.4. Integration Through Regulation and Targeting Hormonal and Epigenetic Networks

4.5. The Plant Microbiome: PGPR as Bio-Enhancers of Drought Resilience

5. From Mechanisms to Ideotypes: Overcoming the Yield-Survival Trade-Off

6. A Practical Framework for Breeding Drought-Resilient Cereals

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| AGO | anti-gravitropic offset |

| APX | ascorbate peroxidase |

| ASA | ascorbate |

| BRs | brassinosteroids |

| CAT | catalase |

| CRISPR | clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| DHA | dehydroascorbate |

| DHAR | dehydroascorbate reductase |

| DHNs | dehydrins |

| DRO1 | gene DEEPER ROOTING1 |

| GB | glycine betaine |

| GR | glutathione reductase |

| HSP | heat shock proteins |

| MAS | marker-assisted selection |

| PGPR | plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RSA | root system architecture |

| SMART | selective multi-trait analysis and recombinant techniques |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| VLCFAs | very-long-chain fatty acids |

References

- Raven, P.H.; Johnson, G.B. Understanding Biology; William, C., Ed.; Brown Publishing: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-697-22213-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, C.W. An Overview of the Family of Cereal Grains Prominent in World Agriculture. In Encyclopedia of Food Grains; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 73–85. ISBN 978-0-12-394786-4. [Google Scholar]

- Jacott, C.N.; Boden, S.A. Feeling the Heat: Developmental and Molecular Responses of Wheat and Barley to High Ambient Temperatures. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5740–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyshi Rezaei, E.; Webber, H.; Gaiser, T.; Naab, J.; Ewert, F. Heat Stress in Cereals: Mechanisms and Modelling. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 64, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadish, S.V.K. Heat Stress during Flowering in Cereals—Effects and Adaptation Strategies. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovenali, G.; Di Romana, M.L.; Capoccioni, A.; Riccardi, V.; Kuzmanović, L.; Ceoloni, C. Exploring Thinopyrum Spp. Group 7 Chromosome Introgressions to Improve Durum Wheat Performance under Intense Daytime and Night-Time Heat Stress at Anthesis. Plants 2024, 13, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bome, N.A.; Ushakova, T.F.; Modenova, E.A.; Bome, A.Y. Research of dependence water-retentive capability for leaves of Triticum aestivum L. from their linear dimensions and the area. Int. Res. J. 2016, 4, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M.A. Plant Drought Stress: Effects, Mechanisms and Management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, K.; Muneer, S. Drought Stress-Induced Physiological Mechanisms, Signaling Pathways and Molecular Response of Chloroplasts in Common Vegetable Crops. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 669–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudinova, L.A.; Orlova, N.V. Fiziologija Ustojchivosti Rastenij: Ucheb. Posobie k Speckursu; Perm. un-t.: Perm, Russia, 2006; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Mwadzingeni, L.; Shimelis, H.; Rees, D.J.G.; Tsilo, T.J. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Agronomic Traits in Wheat under Drought-Stressed and Non-Stressed Conditions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanth, K.; Sanjay Mane, R.; Deo Prasad, B.; Sahni, S.; Kumari, P.; Quaiyum, Z.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.; Kumar Chaudhary, R. Editing the Future: CRISPR/Cas9 for Climate-Resilient Crops. In Genetics; Tombuloglu, H., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025; Volume 7, ISBN 978-1-83634-797-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Xiong, L. General Mechanisms of Drought Response and Their Application in Drought Resistance Improvement in Plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, A.; Goel, S.; Elias, A.A. Understanding Role of Roots in Plant Response to Drought: Way Forward to Climate-resilient Crops. Plant Genome 2024, 17, e20395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, S.; Hausman, J.-F.; Guerriero, G.; Esposito, S. Poaceae vs. Abiotic Stress: Focus on Drought and Salt Stress, Recent Insights and Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, I.P.; Schaaf, C.; De Setta, N. Drought Responses in Poaceae: Exploring the Core Components of the ABA Signaling Pathway in Setaria Italica and Setaria Viridis. Plants 2024, 13, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudle, E. Water Uptake by Plant Roots: An Integration of Views. Plant Soil 2000, 226, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudoyarova, G.; Veselova, S.; Hartung, W.; Farhutdinov, R.; Veselov, D.; Sharipova, G. Involvement of Root ABA and Hydraulic Conductivity in the Control of Water Relations in Wheat Plants Exposed to Increased Evaporative Demand. Planta 2011, 233, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Kianersi, F.; Poczai, P.; Moradkhani, H. Potential of Wild Relatives of Wheat: Ideal Genetic Resources for Future Breeding Programs. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreszies, T.; Eggels, S.; Kreszies, V.; Osthoff, A.; Shellakkutti, N.; Baldauf, J.A.; Zeisler-Diehl, V.V.; Hochholdinger, F.; Ranathunge, K.; Schreiber, L. Seminal Roots of Wild and Cultivated Barley Differentially Respond to Osmotic Stress in Gene Expression, Suberization, and Hydraulic Conductivity. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, P.; An, Y.; Wang, C.-M.; Hao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, P. Endodermal Apoplastic Barriers Are Linked to Osmotic Tolerance in Meso-Xerophytic Grass Elymus Sibiricus. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1007494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.J. The Increasing Importance of Distinguishing among Plant Nitrogen Sources. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Martinoia, E.; Renton, M. Plant Adaptations to Severely Phosphorus-Impoverished Soils. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 25, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowdar, H.S.; Wong, W.W.; Henry, R.; Cook, P.L.M.; McCarthy, D.T. Interactive Effect of Temperature and Plant Species on Nitrogen Cycling and Treatment in Stormwater Biofiltration Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.; Dong, M.; Wang, C.; Miao, Y. Effects of Drought and Salt Stress on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Elymus nutans. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, P. Climate Change and Adaptation Strategies: A Study of Agriculture and Livelihood Adaptation by Farmers in Bardiya District, Nepal. Adv. Agric. Environ. Sci. Open Access (AAEOA) 2019, 2, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uga, Y.; Okuno, K.; Yano, M. Dro1, a Major QTL Involved in Deep Rooting of Rice under Upland Field Conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2485–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Rehman, O.U.; Muzammil, S.; Léon, J.; Naz, A.A.; Rasool, F.; Ali, G.M.; Zafar, Y.; Khan, M.R. Evolution of Deeper Rooting 1-like Homoeologs in Wheat Entails the C-Terminus Mutations as Well as Gain and Loss of Auxin Response Elements. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.; Soolanayakanahally, R.; Ogawa, S.; Uga, Y.; Selvaraj, M.G.; Kagale, S. Drought Response in Wheat: Key Genes and Regulatory Mechanisms Controlling Root System Architecture and Transpiration Efficiency. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, R.; Rosignoli, S.; Lou, H.; Sangiorgi, G.; Bovina, R.; Pattem, J.K.; Borkar, A.N.; Lombardi, M.; Forestan, C.; Milner, S.G.; et al. Root Angle Is Controlled by EGT1 in Cereal Crops Employing an Antigravitropic Mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2201350119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosquete, M.R.; von Wangenheim, D.; Marhavý, P.; Barbez, E.; Stelzer, E.H.K.; Benková, E.; Maizel, A.; Kleine-Vehn, J. An Auxin Transport Mechanism Restricts Positive Orthogravitropism in Lateral Roots. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Kouser, S.; Asgher, M.; Gandhi, S.G. Plant Aquaporins: A Frontward to Make Crop Plants Drought Resistant. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1089–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreszies, T.; Shellakkutti, N.; Osthoff, A.; Yu, P.; Baldauf, J.A.; Zeisler-Diehl, V.V.; Ranathunge, K.; Hochholdinger, F.; Schreiber, L. Osmotic Stress Enhances Suberization of Apoplastic Barriers in Barley Seminal Roots: Analysis of Chemical, Transcriptomic and Physiological Responses. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Wu, P.; Gao, H.; Kosma, D.K.; Jenks, M.A.; Lü, S. Natural Variation in Root Suberization Is Associated with Local Environment in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uga, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Ogawa, S.; Rane, J.; Ishitani, M.; Hara, N.; Kitomi, Y.; Inukai, Y.; Ono, K.; Kanno, N.; et al. Control of Root System Architecture by DEEPER ROOTING 1 Increases Rice Yield under Drought Conditions. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, S.; Tuteja, N. Cold, Salinity and Drought Stresses: An Overview. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 444, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, B.; Foyer, C.H.; Pandey, G.K. The Integration of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Calcium Signalling in Abiotic Stress Responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1985–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Qin, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zeng, F.; Deng, F.; Chater, C.; Xu, S.; Chen, Z. Stomatal Evolution and Plant Adaptation to Future Climate. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3299–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Liu, L.; Facette, M. Flanking Support: How Subsidiary Cells Contribute to Stomatal Form and Function. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, T.D.G.; Zhang, D.; Raissig, M.T. Form, Development and Function of Grass Stomata. Plant J. 2020, 101, 780–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Blatt, M.R. Surrounded by Luxury: The Necessities of Subsidiary Cells. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3316–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-H.; Chen, G.; Dai, F.; Wang, Y.; Hills, A.; Ruan, Y.-L.; Zhang, G.; Franks, P.J.; Nevo, E.; Blatt, M.R. Molecular Evolution of Grass Stomata. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, S.; Wang, H. MicroRNA: A Mobile Signal Mediating Information Exchange within and beyond Plant Organisms. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2024, 43, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, N.; Maierhofer, T.; Herrmann, J.; Jørgensen, M.E.; Lind, C.; Von Meyer, K.; Lautner, S.; Fromm, J.; Felder, M.; Hetherington, A.M.; et al. A Tandem Amino Acid Residue Motif in Guard Cell SLAC1 Anion Channel of Grasses Allows for the Control of Stomatal Aperture by Nitrate. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 1370–1379.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Chang, L.; Chen, J.; Chai, S.; Li, M. Genetic Dissection of Flag Leaf Morphology in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) under Diverse Water Regimes. BMC Genet. 2016, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, R.; Choudhary, A.; Srivastava, P.; Kaur, H.; Padhy, A.K. Morpho-Physiological Evaluation of Elymus Semicostatus (Nees Ex Steud.) Melderis as Potential Donor for Drought Tolerance in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2022, 69, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Ramegowda, V.; Kumar, A.; Pereira, A. Plant Adaptation to Drought Stress. F1000Research 2016, 5, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, H.J.; Davis, R.F. Effect of Drought Stress on Leaf and Whole Canopy Radiation Use Efficiency and Yield of Maize. Agron. J. 2003, 95, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debangshi, U. Crop Microclimate Modification to Address Climate Change. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2021, 8, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.; Kiemnec, G. Seedling Growth and Interference of Diffuse Knapweed (Centaurea diffusa) and Bluebunch Wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata). Weed Technol. 2003, 17, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, L.H.; Greenall, A.; Carlyle, C.; Turkington, R.; Friedman, C.R. Adaptive Phenotypic Plasticity of Pseudoroegneria spicata: Response of Stomatal Density, Leaf Area and Biomass to Changes in Water Supply and Increased Temperature. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, P.J.; Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C.; Park, M.-J.; Go, Y.S.; Park, C.-M. The MYB96 Transcription Factor Regulates Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis under Drought Conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xiong, L. Putative Megaenzyme DWA1 Plays Essential Roles in Drought Resistance by Regulating Stress-Induced Wax Deposition in Rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17790–17795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mo, Y.; Cui, Q.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y.; Wei, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, X. Transcriptomic and Physiological Analyses Reveal Drought Adaptation Strategies in Drought-Tolerant and -Susceptible Watermelon Genotypes. Plant Sci. 2019, 278, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, M.; Keyl, A.; Feussner, I. Wax Biosynthesis in Response to Danger: Its Regulation upon Abiotic and Biotic Stress. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, L.; Kunst, L.; Jetter, R. Sealing Plant Surfaces: Cuticular Wax Formation by Epidermal Cells. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 683–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Li, C.; Hu, N.; Zhu, Y.; He, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. ECERIFERUM1-6A Is Required for the Synthesis of Cuticular Wax Alkanes and Promotes Drought Tolerance in Wheat. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 1640–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, N.; Tindjau, R.; Wong, D.C.J.; Matzat, T.; Haslam, T.; Song, C.; Gambetta, G.A.; Kunst, L.; Castellarin, S.D. Drought Stress Modulates Cuticular Wax Composition of the Grape Berry. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3126–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjari, S.; Shobbar, Z.-S.; Ghanati, F.; Afshari-Behbahanizadeh, S.; Farajpour, M.; Jokar, M.; Khazaei, A.; Shahbazi, M. Molecular, Chemical, and Physiological Analyses of Sorghum Leaf Wax under Post-Flowering Drought Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 159, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Wu, D.; Chen, C.; Yang, X.; Cheng, S.; Sha, L.; Deng, S.; Cheng, Y.; Fan, X.; Kang, H.; et al. A Chromosome Level Genome Assembly of Pseudoroegneria Libanotica Reveals a Key Kcs Gene Involves in the Cuticular Wax Elongation for Drought Resistance. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z.-H. Molecular and Evolutionary Mechanisms of Cuticular Wax for Plant Drought Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Batool, A.; Xu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Lin, X.; Bie, X.; et al. TabHLH27 Orchestrates Root Growth and Drought Tolerance to Enhance Water Use Efficiency in Wheat. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1295–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajhi, A.; Alharbi, S.; Beecham, S.; Alotaibi, F. Regulation of Root Growth and Elongation in Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1397337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Kitomi, Y.; Kuroda, R.; Nakata, R.; Iba, M.; Soma, F.; Teramoto, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Uga, Y. Vertical Rooting Caused by Enhanced Functional Allele of qSOR1 Improves Rice Yield under Drought Stress. bioRxiv 2025, 2025-06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chang, C. Interplays of Cuticle Biosynthesis and Stomatal Development: From Epidermal Adaptation to Crop Improvement. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 25449–25461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.; Roychowdhury, R.; Fujita, M. Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Mechanisms of Heat Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9643–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, M.; Iftikhar Hussain, M. Rising Atmospheric Temperature Impact on Wheat and Thermotolerance Strategies. Plants 2020, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, U.K.; Islam, M.N.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Khan, M.A.R. Understanding the Roles of Osmolytes for Acclimatizing Plants to Changing Environment: A Review of Potential Mechanism. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1913306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under Drought and Salt Stress: Regulation Mechanisms from Whole Plant to Cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyriac, D.; Hofmann, R.W.; Stewart, A.; Sathish, P.; Winefield, C.S.; Moot, D.J. Intraspecific Differences in Long-Term Drought Tolerance in Perennial Ryegrass. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of Proline under Changing Environments: A Review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Sinha, K.; Bhunia, R.K. Can Wheat Survive in Heat? Assembling Tools towards Successful Development of Heat Stress Tolerance in Triticum aestivum L. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 2577–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Mubeen, B.; Hasnain, A.; Rizwan, M.; Adrees, M.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Iqbal, S.; Kamran, M.; El-Sabrout, A.M.; Elansary, H.O.; et al. Role of Promising Secondary Metabolites to Confer Resistance Against Environmental Stresses in Crop Plants: Current Scenario and Future Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 881032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, J.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Ourang, S.F.; Mehrabi, A.A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Wild Relatives of Wheat: Aegilops–Triticum Accessions Disclose Differential Antioxidative and Physiological Responses to Water Stress. Acta Physiol. Plant 2018, 40, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Niu, L.; Jameson, P.E.; Zhou, W. Transcription-Associated Metabolomic Adjustments in Maize Occur during Combined Drought and Cold Stress. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 677–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Roles of Glycine Betaine and Proline in Improving Plant Abiotic Stress Resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, F.; Alyafei, M.; Hayat, F.; Al-Zayadneh, W.; El-Keblawy, A.; Sulieman, S.; Sheteiwy, M.S. Deciphering the Role of Glycine Betaine in Enhancing Plant Performance and Defense Mechanisms against Environmental Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1582332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Gambhir, G.; Dass, A.; Tripathi, A.K.; Singh, A.; Jha, A.K.; Yadava, P.; Choudhary, M.; Rakshit, S. Genetically Modified Crops: Current Status and Future Prospects. Planta 2020, 251, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Manna, M.; Thakur, T.; Gautam, V.; Salvi, P. Imperative Role of Sugar Signaling and Transport during Drought Stress Responses in Plants. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 171, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impa, S.M.; Sunoj, V.S.J.; Krassovskaya, I.; Bheemanahalli, R.; Obata, T.; Jagadish, S.V.K. Carbon Balance and Source-sink Metabolic Changes in Winter Wheat Exposed to High Night-time Temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Su, X.; Xiong, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, J.; Shu, X.; Bai, S.; Lei, X.; Yan, L.; et al. Comparative Metabolomic Studies of Siberian Wildrye (Elymus sibiricus L.): A New Look at the Mechanism of Plant Drought Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluru, R.; Van Den Ende, W. Plant Fructans in Stress Environments: Emerging Concepts and Future Prospects. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2905–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, R.; Palombi, N.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Proline Accumulation in Pollen Grains as Potential Target for Improved Yield Stability Under Salt Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 582877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Machinery in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Roychoudhury, A. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Response of Antioxidants as ROS-Scavengers during Environmental Stress in Plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Kang, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Comparative Physiological and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Genotype Specific Response to Drought Stress in Siberian Wildrye (Elymus sibiricus). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suneja, Y.; Gupta, A.K.; Bains, N.S. Bread Wheat Progenitors: Aegilops Tauschii (DD Genome) and Triticum Dicoccoides (AABB Genome) Reveal Differential Antioxidative Response under Water Stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Ali, A.; Ullah, Z.; Ali, I.; Kaushik, P.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Rasheed, A.; Sher, H. Exploiting the Drought Tolerance of Wild Elymus Species for Bread Wheat Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 982844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ullah, F.; Zhou, D.-X.; Yi, M.; Zhao, Y. Mechanisms of ROS Regulation of Plant Development and Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Reichheld, J.-P.; Foyer, C.H. ROS-Related Redox Regulation and Signaling in Plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 80, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Sharma, P. Superoxide Dismutases (SODs) and Their Role in Regulating Abiotic Stress Induced Oxidative Stress in Plants. In Reactive Oxygen, Nitrogen and Sulfur Species in Plants; Hasanuzzaman, M., Fotopoulos, V., Nahar, K., Fujita, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 53–88. ISBN 978-1-119-46869-1. [Google Scholar]

- Caverzan, A.; Casassola, A.; Brammer, S.P. Antioxidant Responses of Wheat Plants under Stress. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.; Bhardwaj, S.; Landi, M.; Sharma, A.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Sharma, A. The Impact of Drought in Plant Metabolism: How to Exploit Tolerance Mechanisms to Increase Crop Production. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Omidi, M.; Naghavi, M.R.; Etminan, A.; Mehrabi, A.A.; Poczai, P. Wild Relatives of Wheat Respond Well to Water Deficit Stress: A Comparative Study of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and Their Encoding Gene Expression. Agriculture 2020, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorová, Z.; Kováčik, J.; Klejdus, B.; Maglovski, M.; Kuna, R.; Hauptvogel, P.; Matušíková, I. Drought-Induced Responses of Physiology, Metabolites, and PR Proteins in Triticum aestivum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8125–8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikilitas, M.; Simsek, E.; Roychoudhury, A. Modulation of Abiotic Stress Tolerance Through Hydrogen Peroxide. In Protective Chemical Agents in the Amelioration of Plant Abiotic Stress; Roychoudhury, A., Tripathi, D.K., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 147–173. ISBN 978-1-119-55163-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.-W.; Zhang, C.-R.; Wang, W.-H.; Xu, G.-H.; Zhang, H.-Y. Seed Priming Improves Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Isatis Indigotica Fort. under Salt Stress. HortScience 2020, 55, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, M.; Geisler, M. HSP90 and Co-Chaperones: A Multitaskers’ View on Plant Hormone Biology. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmusoglu, S.; Saglam, A.; Kadıoglu, A. Modulation of HSPs by Phytohormone Applications. In Improving Stress Resilience in Plants; Elsevier: North Andover, MA, USA; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 277–295. ISBN 978-0-443-18927-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kosová, K.; Vítámvás, P.; Prášil, I.T. Wheat and Barley Dehydrins under Cold, Drought, and Salinity €“ What Can LEA-II Proteins Tell Us about Plant Stress Response? Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyazuddin, R.; Nisha, N.; Singh, K.; Verma, R.; Gupta, R. Involvement of Dehydrin Proteins in Mitigating the Negative Effects of Drought Stress in Plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, W.T.B. Drought-Resistant Cereals: Impact on Water Sustainability and Nutritional Quality. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahjib-Ul-Arif, M.; Zahan, M.I.; Karim, M.M.; Imran, S.; Hunter, C.T.; Islam, M.S.; Mia, M.; Hannan, M.A.; Rhaman, M.S.; Hossain, M.A.; et al. Citric Acid-Mediated Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Shiade, S.R.G.; Saleem, A.; Shohani, F.; Fazeli, A.; Riaz, A.; Zulfiqar, U.; Shabaan, M.; Ahmed, I.; Rahimi, M. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Antioxidant Systems in Enhancing Plant Resilience Against Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Agron. 2025, 2025, 8834883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.J.; Kudoyarova, G.; Hartung, W. Long-Distance ABA Signaling and Its Relation to Other Signaling Pathways in the Detection of Soil Drying and the Mediation of the Plant’s Response to Drought. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2005, 24, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Kuromori, T.; Urano, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Drought Stress Responses and Resistance in Plants: From Cellular Responses to Long-Distance Intercellular Communication. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 556972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.; Dubeaux, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Schroeder, J.I. Signaling Mechanisms in Abscisic Acid-mediated Stomatal Closure. Plant J. 2021, 105, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saradadevi, R.; Palta, J.A.; Siddique, K.H.M. ABA-Mediated Stomatal Response in Regulating Water Use during the Development of Terminal Drought in Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherzer, S.; Böhm, J.; Huang, S.; Iosip, A.L.; Kreuzer, I.; Becker, D.; Heckmann, M.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.S.; Dreyer, I.; Hedrich, R. A Unique Inventory of Ion Transporters Poises the Venus Flytrap to Fast-Propagating Action Potentials and Calcium Waves. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 4255–4263.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Szarejko, I. Open or Close the Gate – Stomata Action Under the Control of Phytohormones in Drought Stress Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharath, P.; Gahir, S.; Raghavendra, A.S. Abscisic Acid-Induced Stomatal Closure: An Important Component of Plant Defense Against Abiotic and Biotic Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 615114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Khurana, J.P. Transcript Profiling Reveals Diverse Roles of Auxin-responsive Genes during Reproductive Development and Abiotic Stress in Rice. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 3148–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Song, X.; Mehra, P.; Yu, S.; Li, Q.; Tashenmaimaiti, D.; Bennett, M.; Kong, X.; Bhosale, R.; Huang, G. ABA-Auxin Cascade Regulates Crop Root Angle in Response to Drought. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 542–553.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, J.; Li, Y.; Quan, R.; Huang, R. Abscisic Acid Promotes Auxin Biosynthesis to Inhibit Primary Root Elongation in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudesblat, G.E.; Russinova, E. Plants Grow on Brassinosteroids. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Zeng, F.; Han, Z.; Qiu, C.; Zeng, M.; Yang, Z.; Xu, F.; Wu, D.; Deng, F.; et al. Molecular Evidence for Adaptive Evolution of Drought Tolerance in Wild Cereals. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Xiong, Y.; Song, X.; Wadey, S.; Yu, S.; Rao, J.; Lale, A.; Lombardi, M.; Fusi, R.; Bhosale, R.; et al. Ethylene Regulates Auxin-Mediated Root Gravitropic Machinery and Controls Root Angle in Cereal Crops. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafique, S.; Quadri, S.N.; Abdin, M.Z. Plant Defense Mechanism in Combined Stresses—Cellular and Molecular Perspective. J. Plant Stress Physiol. 2024, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, A.; Ganguly, S.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Chakraborti, D. Understanding the Interaction of Molecular Factors During the Crosstalk Between Drought and Biotic Stresses in Plants. In Molecular Plant Abiotic Stress; Roychoudhury, A., Tripathi, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 427–446. ISBN 978-1-119-46366-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss, B.R.; Gangola, M.P.; Gurunathan, S. NAC Transcription Factor Family in Rice: Recent Advancements in the Development of Stress-Tolerant Rice. In Transcription Factors for Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 47–61. ISBN 978-0-12-819334-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, D.; Majgaonkar, A.; Maurya, A.K.; Das, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Saha, U.; Saha, B.; Dutta, S.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Chatterjee, C.; et al. Epigenetics for Developing Abiotic Stress-Tolerant Plants: Updated Methods and Current Achievements. In CABI Climate Change Series; Chen, J.-T., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2025; pp. 61–97. ISBN 978-1-80062-608-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, Z. Drought Stress Induces Differential DNA Methylation Shift at Symmetric and Asymmetric Cytosine Sites in the Promoter Region of ZmEXPB2 Gene in Maize. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2021, 25, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M. The Role of microRNA in Stress Signaling and Adaptive Response in Plants. In Stress Biology in Photosynthetic Organisms; Mishra, A.K., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 87–106. ISBN 978-981-97-1882-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhakypbek, Y.; Belkozhayev, A.M.; Kerimkulova, A.; Kossalbayev, B.D.; Murat, T.; Tursbekov, S.; Turysbekova, G.; Tursunova, A.; Tastambek, K.T.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. MicroRNAs in Plant Genetic Regulation of Drought Tolerance and Their Function in Enhancing Stress Adaptation. Plants 2025, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Das, S.P.; Choudhury, B.U.; Kumar, A.; Prakash, N.R.; Verma, R.; Chakraborti, M.; Devi, A.G.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Das, R.; et al. Advances in Genomic Tools for Plant Breeding: Harnessing DNA Molecular Markers, Genomic Selection, and Genome Editing. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadul, S.M.; Arshad, A.; Mehmood, R. CRISPR-Based Epigenome Editing: Mechanisms and Applications. Epigenomics 2023, 15, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Uğurlar, F.; Adamakis, I.-D.S. Epigenetic Modifications of Hormonal Signaling Pathways in Plant Drought Response and Tolerance for Sustainable Food Security. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnajmedin, F.; Majidi, M.M.; Jaškūnė, K. Adaptive Strategies to Drought Stress in Grasses of the Poaceae Family under Climate Change: Physiological, Genetic and Molecular Perspectives: A Review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 213, 108814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, D.; Yadav, A.N. Bacterial Mitigation of Drought Stress in Plants: Current Perspectives and Future Challenges. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosten, M.J.; Pepe, O.; De Pascale, S.; Silletti, S.; Maggio, A. The Role of Biostimulants and Bioeffectors as Alleviators of Abiotic Stress in Crop Plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C. Microbial Modulation of Hormone Signaling, Proteomic Dynamics, and Metabolomics in Plant Drought Adaptation. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.; Weinand, T.; Asch, F. Plant–Rhizobacteria Interactions Alleviate Abiotic Stress Conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 1682–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmusk, S.; Abd El-Daim, I.A.; Copolovici, L.; Tanilas, T.; Kännaste, A.; Behers, L.; Nevo, E.; Seisenbaeva, G.; Stenström, E.; Niinemets, Ü. Drought-Tolerance of Wheat Improved by Rhizosphere Bacteria from Harsh Environments: Enhanced Biomass Production and Reduced Emissions of Stress Volatiles. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngumbi, E.; Kloepper, J. Bacterial-Mediated Drought Tolerance: Current and Future Prospects. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 105, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnawal, D.; Bharti, N.; Pandey, S.S.; Pandey, A.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Kalra, A. Plant Growth-promoting Rhizobacteria Enhance Wheat Salt and Drought Stress Tolerance by Altering Endogenous Phytohormone Levels and TaCTR1/TaDREB2 Expression. Physiol. Plant. 2017, 161, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, C.; Duca, D.; Glick, B.R. Mechanisms of Plant Response to Salt and Drought Stress and Their Alteration by Rhizobacteria. Plant Soil 2017, 410, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khan, N. Delineation of Mechanistic Approaches Employed by Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms for Improving Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 249, 126771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vílchez, J.I.; García-Fontana, C.; Román-Naranjo, D.; González-López, J.; Manzanera, M. Plant Drought Tolerance Enhancement by Trehalose Production of Desiccation-Tolerant Microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkhani, K.; Sharma, A.K. Alleviation of Drought Stress by Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) in Crop Plants: A Review. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2024, 55, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Muhammad, S.; Jin, W.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Munir, R.; et al. Modulating Root System Architecture: Cross-Talk between Auxin and Phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1343928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, M.; Bodhankar, S.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, P.; Singh, J.; Nain, L. PGPR Mediated Alterations in Root Traits: Way Toward Sustainable Crop Production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 618230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Campo, R.J.; Souza, E.M.; Pedrosa, F.O. Inoculation with Selected Strains of Azospirillum Brasilense and A. Lipoferum Improves Yields of Maize and Wheat in Brazil. Plant Soil 2010, 331, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Outstanding Impact of Azospirillum Brasilense Strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 on the Brazilian Agriculture: Lessons That Farmers Are Receptive to Adopt New Microbial Inoculants. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2021, 45, e0200128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieb, M.; Gachomo, E.W. The Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in Plant Drought Stress Responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, D.; Pande, V.; Pandey, S.C.; Samant, M. Recent Advances in PGPR and Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Drought Stress Resistance. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Sogarwal, A.; Gargi; Mishra, S.; Kaur, S. Harnessing Plant-Bacterial Interactions to Enhance Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants: A Review. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Macdonald, C.A.; Singh, P.; Cong, V.T.; Klein, M.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Singh, B.K. Drought-Induced Plant Microbiome and Metabolic Enrichments Improve Drought Resistance. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 882–900.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavamura, V.N.; Santos, S.N.; Silva, J.L.D.; Parma, M.M.; Ávila, L.A.; Visconti, A.; Zucchi, T.D.; Taketani, R.G.; Andreote, F.D.; Melo, I.S.D. Screening of Brazilian Cacti Rhizobacteria for Plant Growth Promotion under Drought. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 168, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R.L.; Van Groenigen, K.J.; Hungate, B.A. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Are More Effective under Drought: A Meta-Analysis. Plant Soil 2017, 416, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Samad, A.; Faist, H.; Sessitsch, A. A Review on the Plant Microbiome: Ecology, Functions, and Emerging Trends in Microbial Application. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitter, E.K.; Tosi, M.; Obregón, D.; Dunfield, K.E.; Germida, J.J. Rethinking Crop Nutrition in Times of Modern Microbiology: Innovative Biofertilizer Technologies. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 606815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhao, X.; Gao, X.; Jia, R.; Yang, M.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M. Effect of Natural Factors and Management Practices on Agricultural Water Use Efficiency under Drought: A Meta-Analysis of Global Drylands. J. Hydrol. 2021, 594, 125977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D.; Sanong, J.; Dutta, A.J.; Nath, R.; Borkataky, M. Advancements in Induced Systemic Resistance: Mechanisms, Applications and Integration for Sustainable Crop Protection and Climate Adaptation. Plant Sci. Today 2025, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Thokchom, S.D.; Gupta, S.; Kapoor, R. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: Role as Biofertilizers, Technology Development, and Economics. In Fungi and Fungal Products in Human Welfare and Biotechnology; Satyanarayana, T., Deshmukh, S.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 3–30. ISBN 978-981-19-8852-3. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo, A.; Sadras, V.O.; Araus, J.L. Yield Potential and Stress Adaptation Are Not Mutually Exclusive: Wheat as a Case Study. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, S1360138525002201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Padilla, Y.G.; Álvarez, S.; Calatayud, Á.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Gómez-Bellot, M.J.; Hernández, J.A.; Martínez-Alcalá, I.; Penella, C.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; et al. Advancements in Water-Saving Strategies and Crop Adaptation to Drought: A Comprehensive Review. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasson, A.P.; Richards, R.A.; Chatrath, R.; Misra, S.C.; Prasad, S.V.S.; Rebetzke, G.J.; Kirkegaard, J.A.; Christopher, J.; Watt, M. Traits and Selection Strategies to Improve Root Systems and Water Uptake in Water-Limited Wheat Crops. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3485–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.J. (Ed.) Understanding and Improving Crop Root Function; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-78676-363-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, M.; Amir Naveed, S.; Masood Shah, S.; Rehman Khan, A.; Musaddiq Shah, M.; Awan, T.; Ramzan Khan, M.; Abbas, Z.; Arif, M. Introgression of Drought Tolerance into Elite Basmati Rice Variety through Marker-Assisted Backcrossing. Phyton 2023, 92, 1421–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justamante, M.S.; Larriba, E.; Luque, A.; Nicolás-Albujer, M.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M. A Systematic Review to Identify Target Genes That Modulate Root System Architecture in Response to Abiotic Stress. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, J.A.; Capó-Bauçà, S.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Galmés, J. Rubisco and Rubisco Activase Play an Important Role in the Biochemical Limitations of Photosynthesis in Rice, Wheat, and Maize under High Temperature and Water Deficit. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Cao, B.; Kang, J.; Wang, X.; Han, X.; Jiang, W.; Shi, X.; Zhang, L.; Cui, L.; Hu, Z.; et al. Fine-Tuning Stomatal Movement Through Small Signaling Peptides. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarto, M.V.M.; Sarto, J.R.W.; Rampim, L.; Rosset, J.S.; Bassegio, D.; Costa, P.F.D.; Inagaki, A.M. Wheat Phenology and Yield under Drought: A Review. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2017, 11, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, Y.D.; Bahuguna, R.N.; Garcia-Caparros, P.; Zwart, R.S.; Reddy, M.S.S.; Mir, R.R.; Jha, U.C.; Fakrudin, B.; Pandey, M.K.; Challabathula, D.; et al. Exploring the Multifaceted Dynamics of Flowering Time Regulation in Field Crops: Insight and Intervention Approaches. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.; Yadav, S.; Khare, V.; Gupta, V.; Patial, M.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, C.N.; Tyagi, B.S.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, A.K.; et al. Wheat Drought Tolerance: Unveiling a Synergistic Future with Conventional and Molecular Breeding Strategies. Plants 2025, 14, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragovich, A.Y.; Fisenko, A.V.; Yankovskaya, A.A. Vernalization (VRN) and Photoperiod (PPD) Genes in Spring Hexaploid Wheat Landraces. Russ. J. Genet. 2021, 57, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Silva, W.; Da Fonseca-Pereira, P.; Martins, A.O.; Zsögön, A.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Araújo, W.L. Engineering Improved Photosynthesis in the Era of Synthetic Biology. Plant Commun. 2020, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Kumar, R.; Tiwari, S.; Verma, L.; Park, S.; Shin, H. Adapting Crops to Rising Temperatures: Understanding Heat Stress and Plant Resilience Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Huang, F.; Wu, N.; Li, X.; Hu, H.; Xiong, L. Integrative Regulation of Drought Escape through ABA-Dependent and -Independent Pathways in Rice. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitomi, Y.; Kanno, N.; Kawai, S.; Mizubayashi, T.; Fukuoka, S.; Uga, Y. QTLs Underlying Natural Variation of Root Growth Angle among Rice Cultivars with the Same Functional Allele of DEEPER ROOTING 1. Rice 2015, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salina, E.A.; Adonina, I.G.; Badaeva, E.D.; Kroupin, P.Y.; Stasyuk, A.I.; Leonova, I.N.; Shishkina, A.A.; Divashuk, M.G.; Starikova, E.V.; Khuat, T.M.L.; et al. A Thinopyrum Intermedium Chromosome in Bread Wheat Cultivars as a Source of Genes Conferring Resistance to Fungal Diseases. Euphytica 2015, 204, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibikeev, S.N.; Badaeva, E.D.; Gultyaeva, E.I.; Druzhin, A.E.; Shishkina, A.A.; Dragovich, A.Y.; Kroupin, P.Y.; Karlov, G.I.; Khuat, T.M.; Divashuk, M.G. Comparative Analysis of Agropyron Intermedium (Host) Beauv 6Agi and 6Agi2 Chromosomes in Bread Wheat Cultivars and Lines with Wheat–Wheatgrass Substitutions. Russ. J. Genet. 2017, 53, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheoran, S.; Kaur, Y.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, S.; Rakshit, S.; Kumar, R. Recent Advances for Drought Stress Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays L.): Present Status and Future Prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 872566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene/Locus | Encoded Protein/Function | Physiological Role in Drought Resilience | Primary Cereal(s) | Potential Application in Breeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Budget Architecture Module | ||||

| DRO1 (DEEPER ROOTING 1) | Protein controlling root growth angle | Promotes steeper root growth angle for deeper soil water foraging. | Rice, Wheat | Introgression into elite varieties to enhance yield under terminal drought. |

| EGT1 (ENHANCED GRAVITROPISM 1) | Regulator of anti-gravitropic offset (AGO) | Fine-tunes root growth angle for shallower, wider soil exploration. | Wheat, Barley | Pyramiding with DRO1 to design root systems for specific soil profiles. |

| CER1 (ECERIFERUM 1) | Aldehyde decarbonylase in cuticular wax biosynthesis | Catalyzes alkane formation, reducing non-stomatal water loss. | Wheat, Barley | Marker-assisted selection for enhanced cuticular wax deposition (‘glaucous’ phenotype). |

| PIPs (Plasma membrane Intrinsic Proteins) | Aquaporins; water channels | Regulates root hydraulic conductivity for efficient water transport. | All major cereals | Selecting for alleles with sustained activity under ABA signaling and drought. |

| Metabolic Homeostasis Module | ||||

| BADH (Betaine Aldehyde Dehydrogenase) | Key enzyme in glycine betaine (GB) synthesis | Accumulates compatible solute GB for osmotic adjustment and macromolecule stabilization. | Wheat, Maize, Barley | Overexpression to enhance drought-tolerant phenotypes without toxicity. |

| P5CS (Δ1-Pyrroline-5-Carboxylate Synthetase) | Key enzyme in proline biosynthesis | Accumulates proline as an osmoprotectant and antioxidant. | All major cereals | Selection for alleles with efficient, inducible expression to manage metabolic cost. |

| SOD, APX, CAT (e.g., MnSOD, TaCAT1) | Antioxidant enzymes (Superoxide Dismutase, Ascorbate Peroxidase, Catalase) | Scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) to mitigate oxidative stress. | Wheat, Maize, Rice | Pyramiding alleles for a robust, coordinated antioxidant system. |

| DHNs (Dehydrins) | Intrinsically disordered protective proteins (LEA D-11 family) | Stabilize membranes and proteins during cellular dehydration. | Wheat, Barley | Use as biochemical markers; selection for favorable allelic variants linked to QTLs. |

| Integrative Signaling & Developmental Reprogramming Module | ||||

| ABA-responsive genes (e.g., OST1, SLAC1) | Kinases and anion channels in ABA signaling | Mediate rapid stomatal closure to minimize water loss. | All major cereals | Selecting for alleles conferring optimal stomatal sensitivity (rapid closure & reopening). |

| DREB2A (Dehydration-Responsive Element-Binding protein 2A) | AP2/ERF-type transcription factor | Master regulator of ABA-independent stress-responsive gene network. | Wheat, Maize, Rice | Genome editing to fine-tune its activity and enhance stress tolerance. |

| Ppd (Photoperiod response) genes | Pseudo-response regulator proteins | Control flowering time, enabling “drought escape” via phenological adjustment | Wheat, Barley | Introgression of photoperiod-insensitive alleles to align flowering with favorable conditions. |

| VRN (Vernalization) genes | MADS-box transcription factors | Regulate the vernalization requirement, influencing developmental timing. | Wheat, Barley | Manipulation to optimize life cycle duration for target environments. |

| HSP70/HSP90 (Heat Shock Proteins) | Molecular chaperones | Prevent protein aggregation and facilitate refolding under stress. | All major cereals | Selection for constitutive or highly inducible expression as a proxy for cellular stability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bursakov, S.A.; Karlov, G.I.; Kroupin, P.Y.; Divashuk, M.G. Overcoming the Yield-Survival Trade-Off in Cereals: An Integrated Framework for Drought Resilience. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122783

Bursakov SA, Karlov GI, Kroupin PY, Divashuk MG. Overcoming the Yield-Survival Trade-Off in Cereals: An Integrated Framework for Drought Resilience. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122783

Chicago/Turabian StyleBursakov, Sergey A., Gennady I. Karlov, Pavel Yu. Kroupin, and Mikhail G. Divashuk. 2025. "Overcoming the Yield-Survival Trade-Off in Cereals: An Integrated Framework for Drought Resilience" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122783

APA StyleBursakov, S. A., Karlov, G. I., Kroupin, P. Y., & Divashuk, M. G. (2025). Overcoming the Yield-Survival Trade-Off in Cereals: An Integrated Framework for Drought Resilience. Agronomy, 15(12), 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122783