Identification of Potential Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Microarray Gene Expression Leveraging Explainable Machine Learning Classifiers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

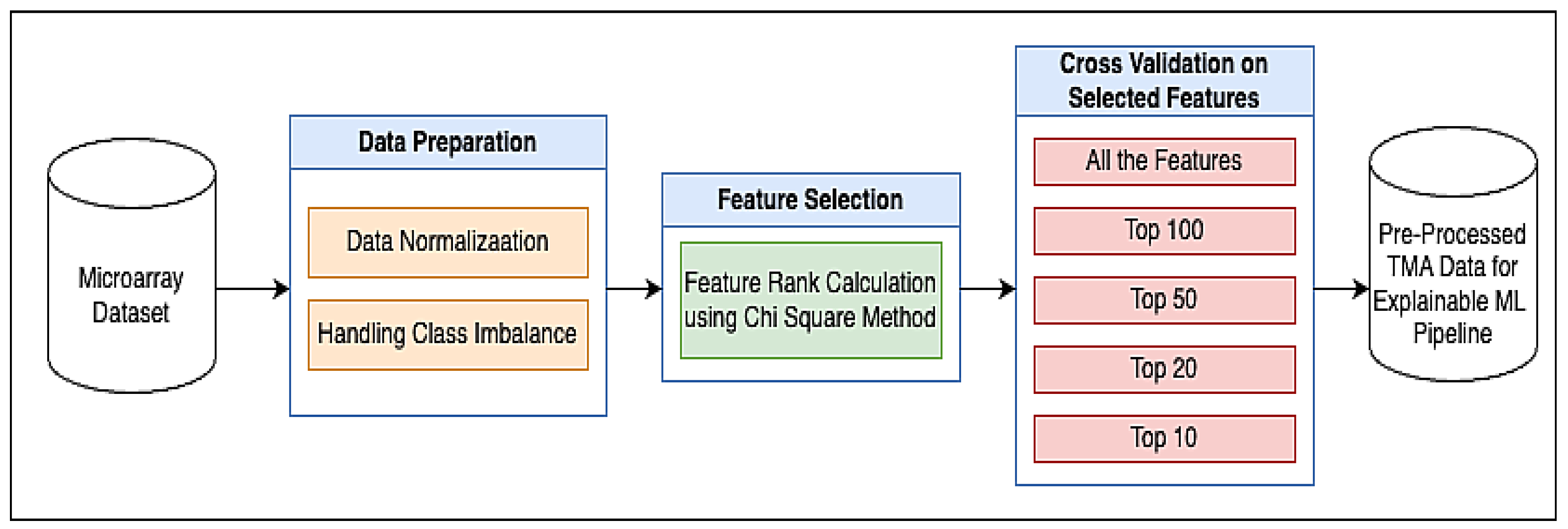

2.1. Proposed Methodology

2.1.1. Dataset

2.1.2. Data Preparation

Data Normalization

Handling Class Imbalance Problem Using the SMOTE-Tomek Link Method

2.1.3. Applying Machine Learning Methods

2.1.4. Chi-Square Method for Feature Selection

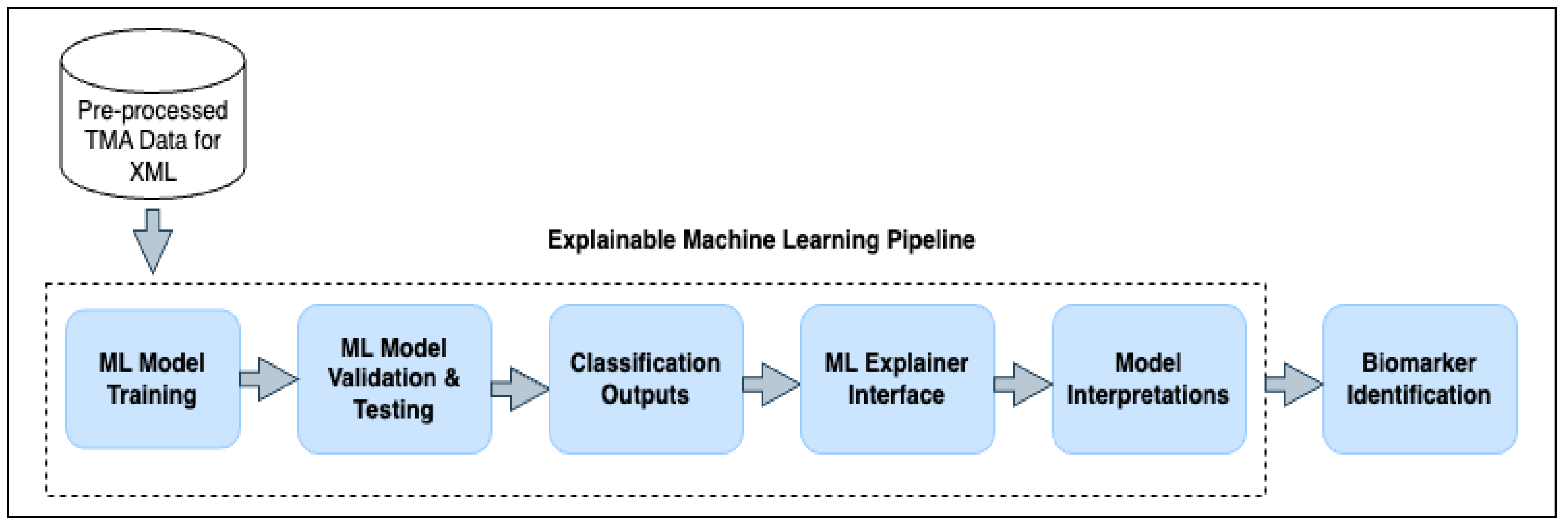

2.1.5. Explainable Machine Learning Pipeline

2.2. Quantifying Performances

3. Results

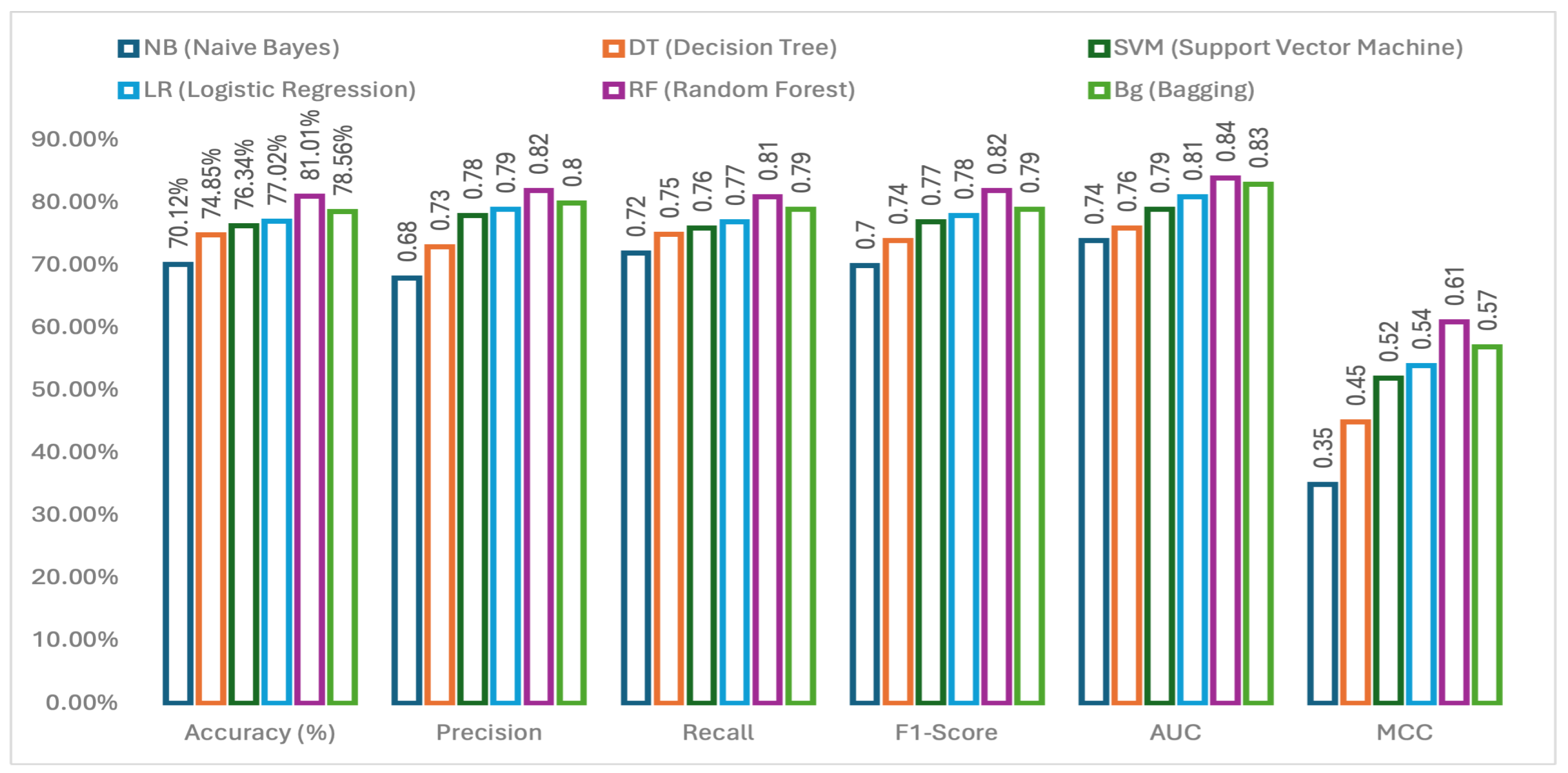

3.1. Performance Comparison of Applied Machine Learning Methods

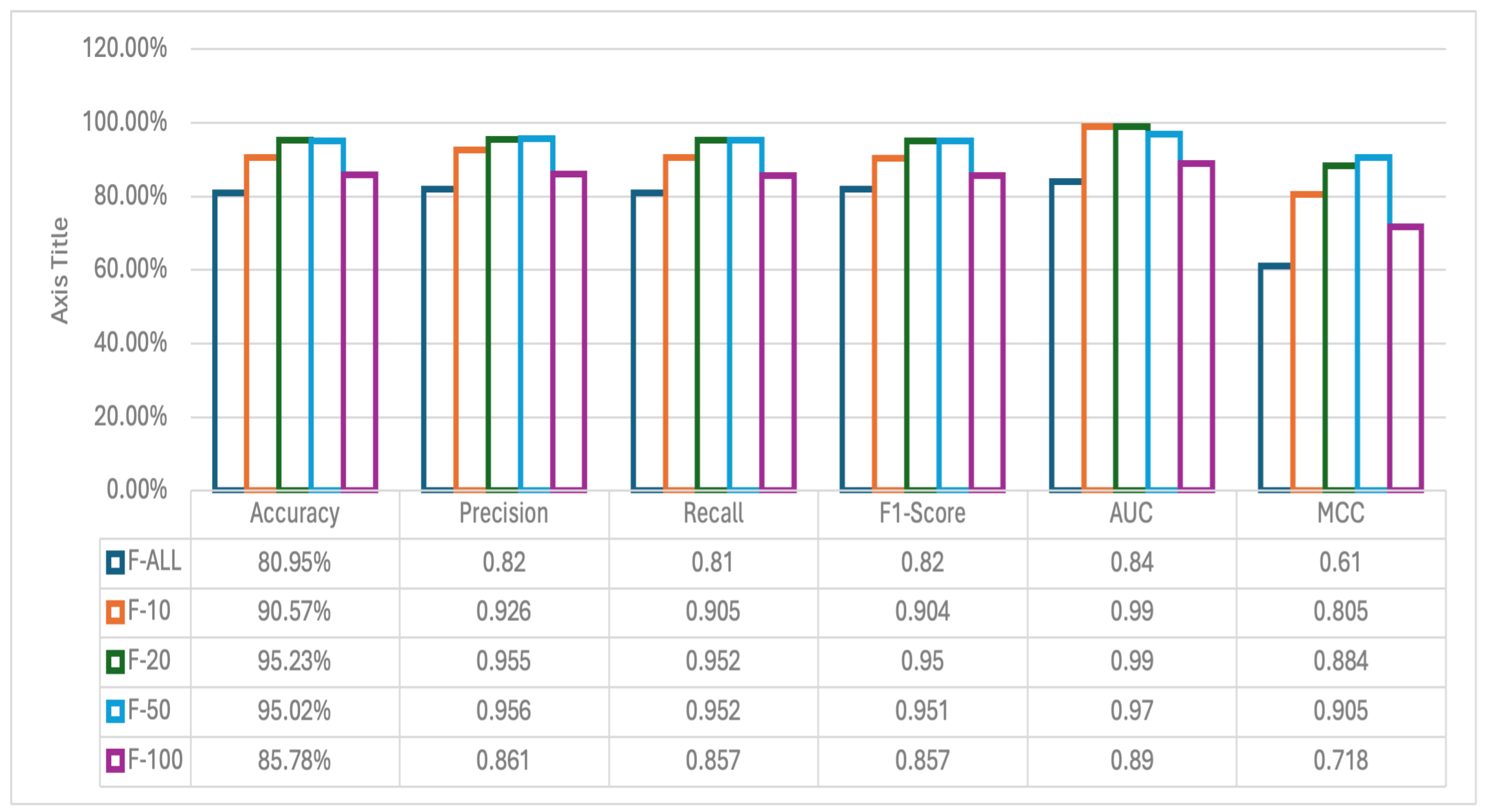

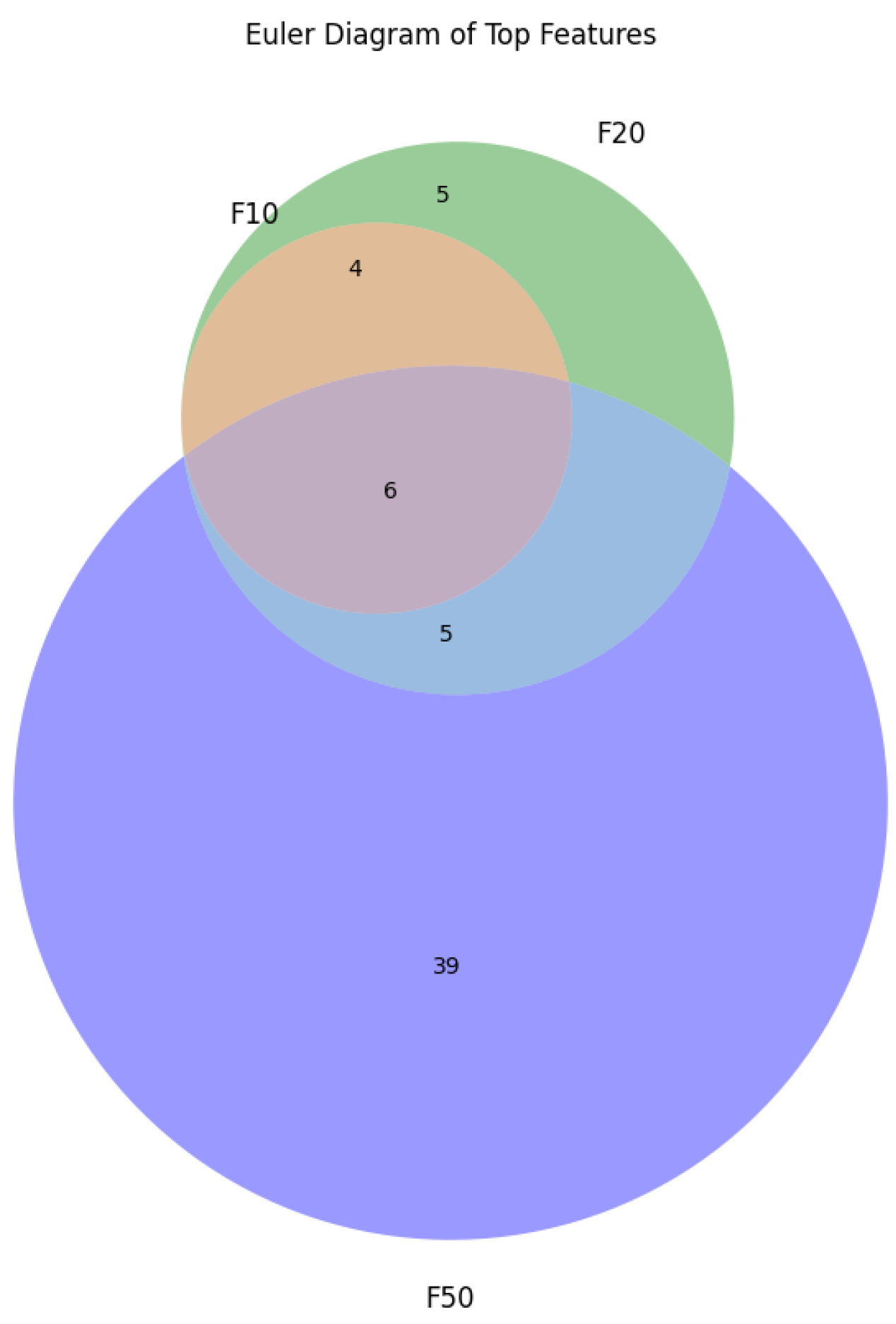

3.2. Experiments on Feature Selection

- F-ALL: Experiment with all genes.

- F-10: Experiment with the top 10 genes.

- F-20: Experiment with the top 20 genes.

- F-50: Experiment with the 50 best genes.

- F-100: Experiment with the top 100 genes.

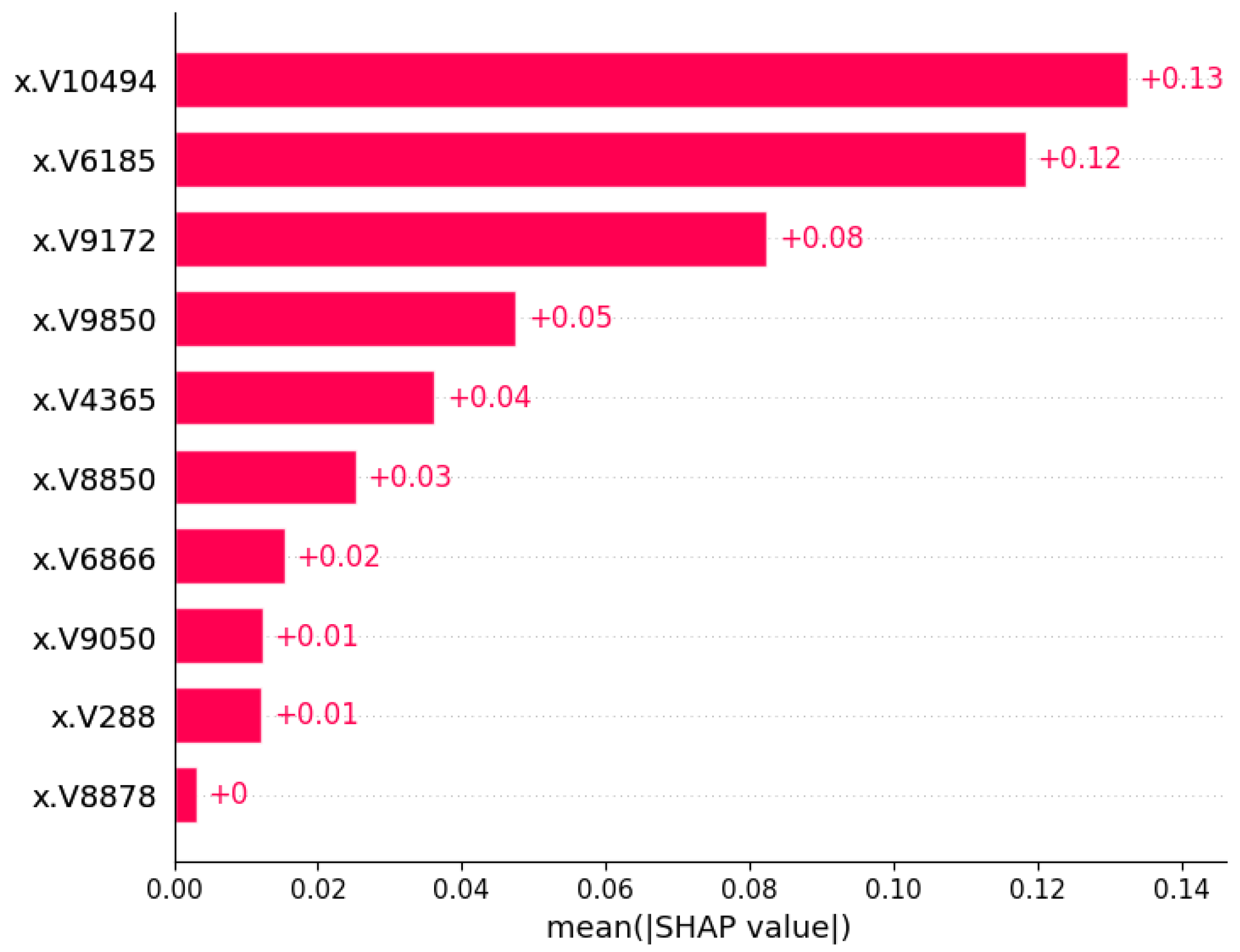

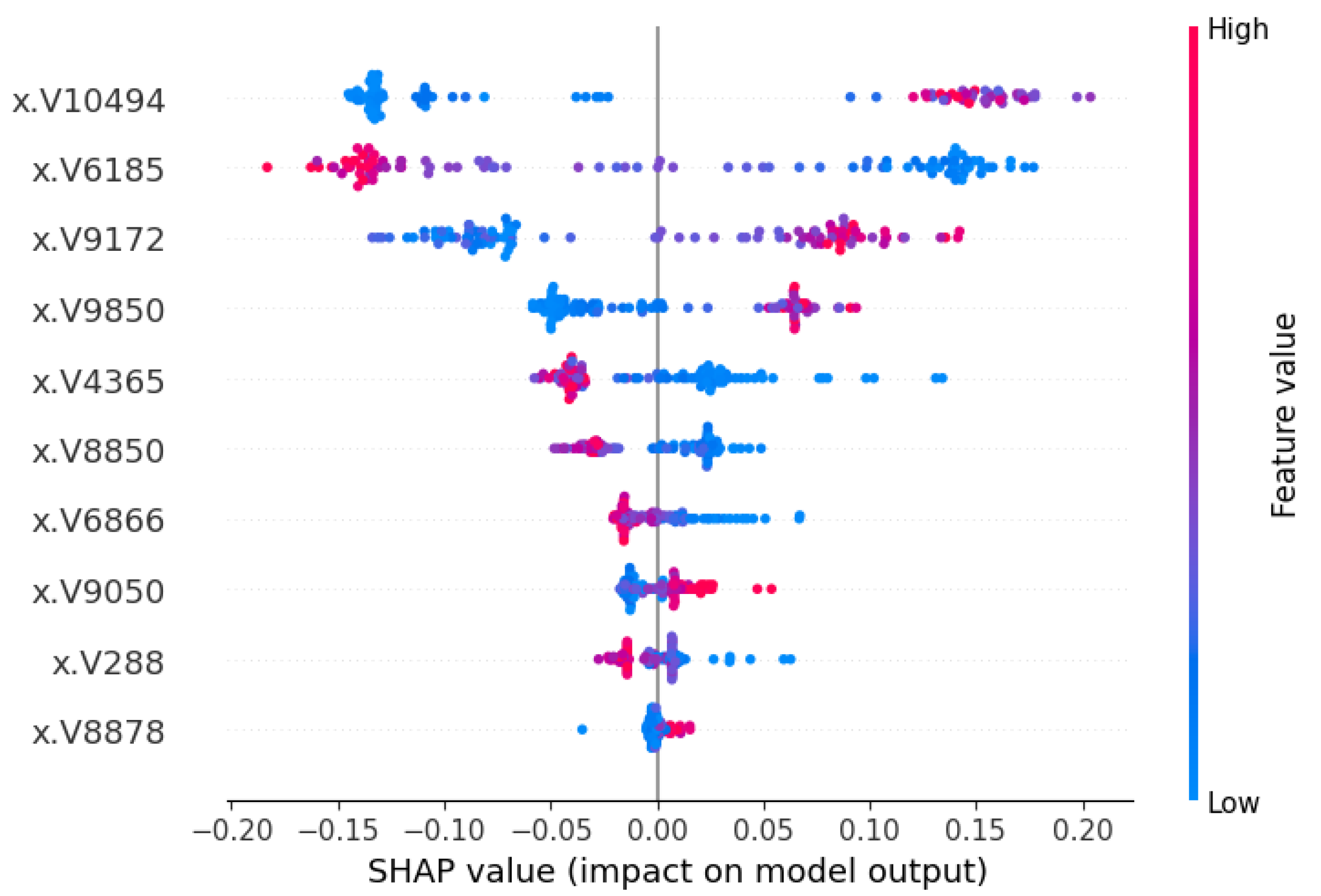

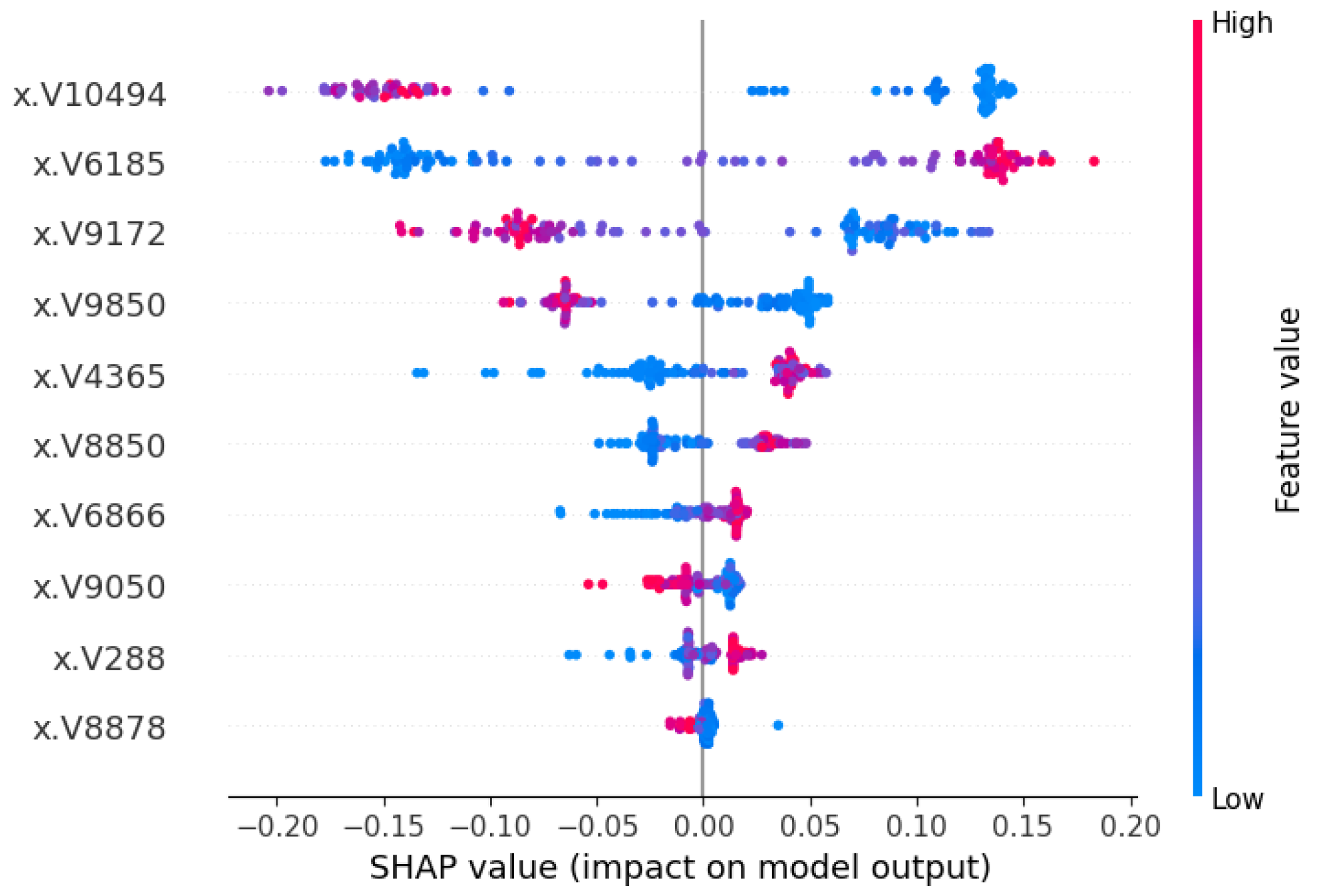

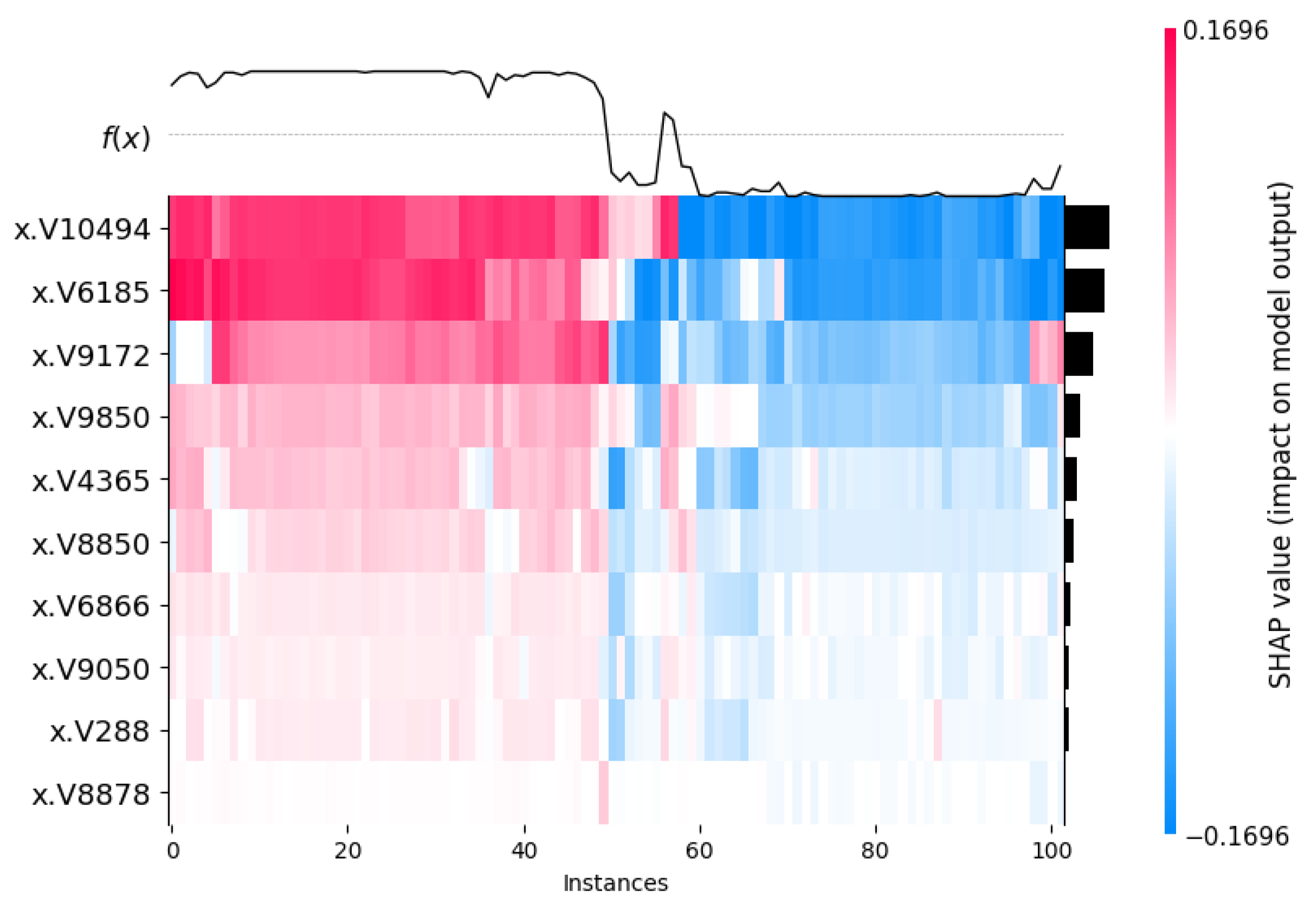

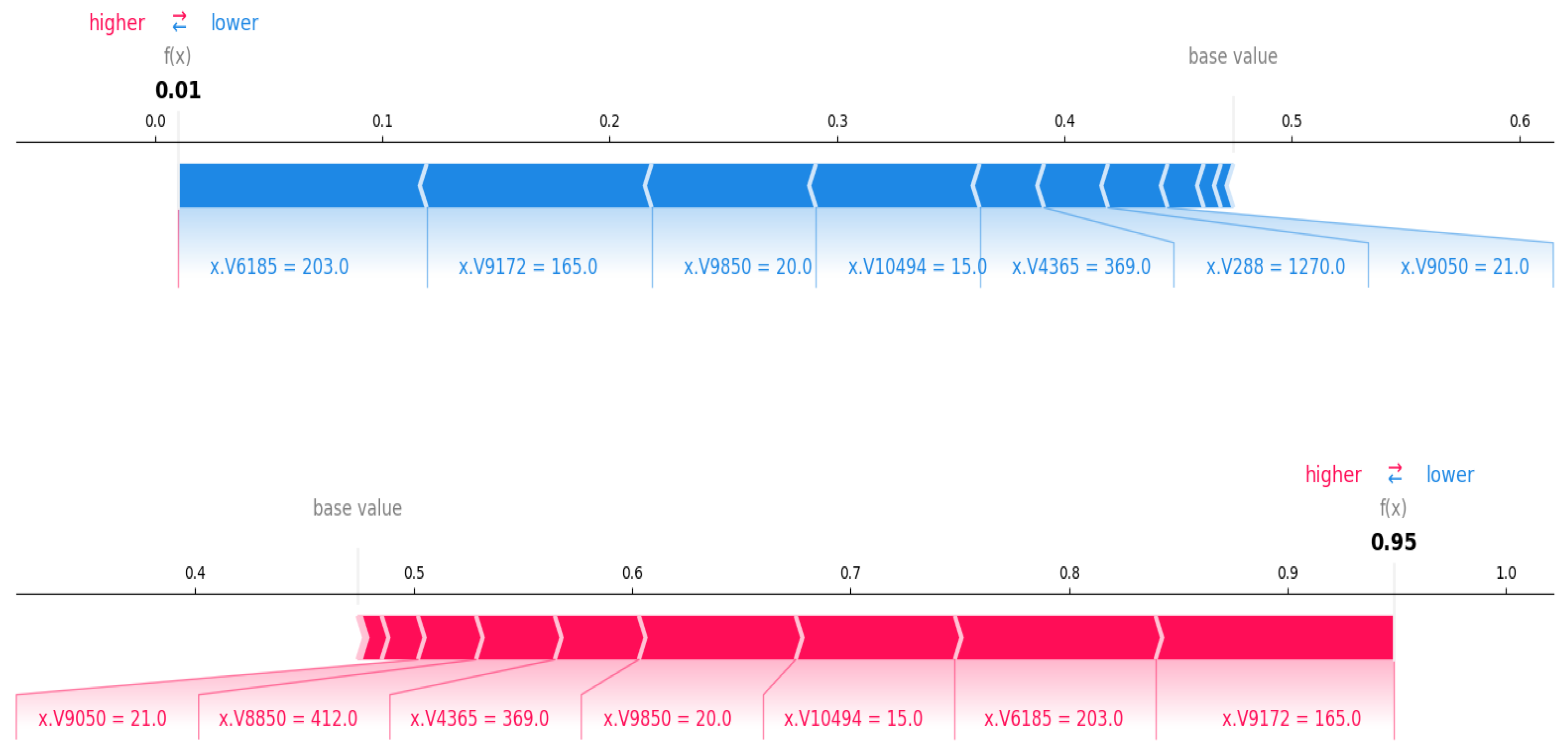

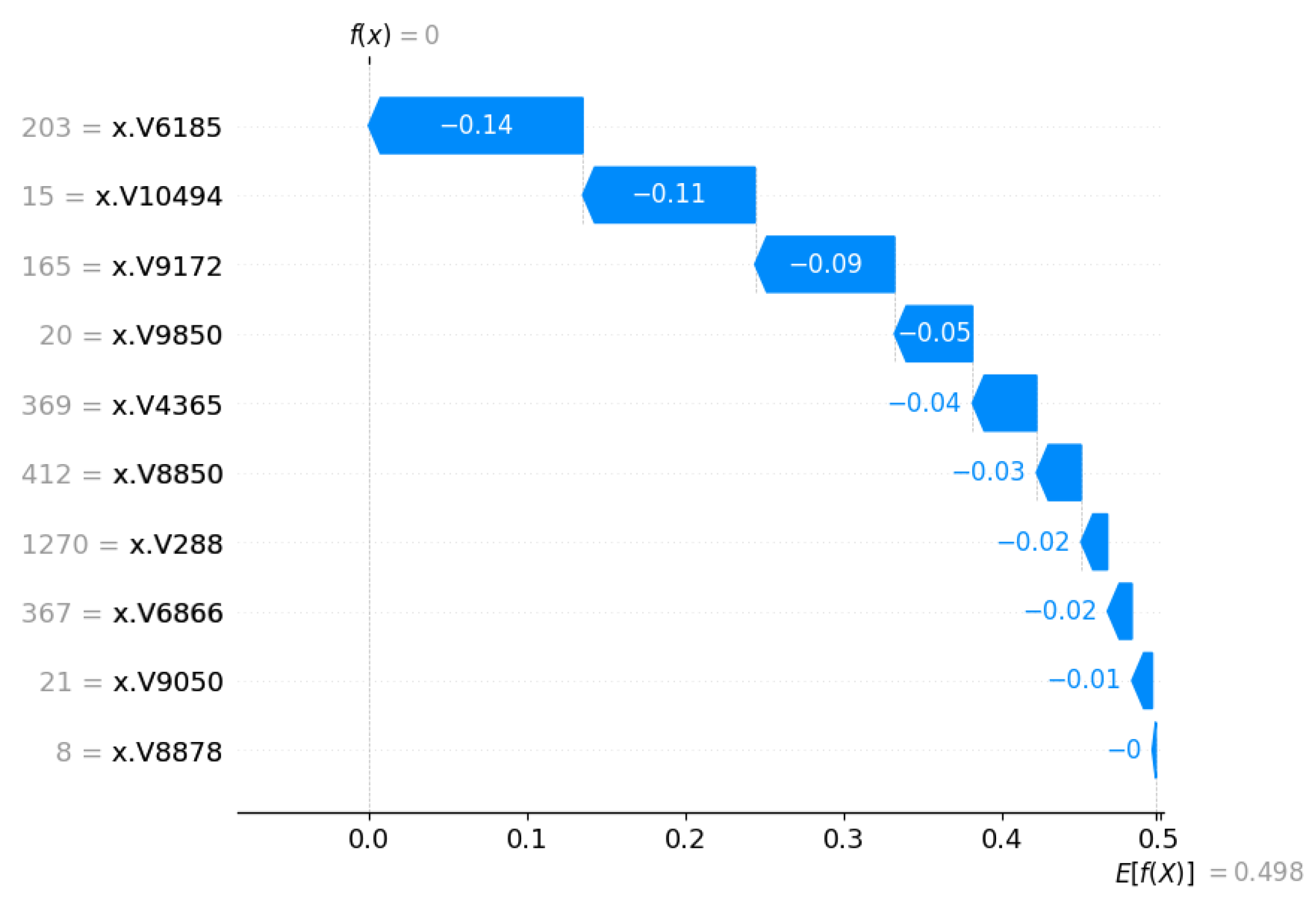

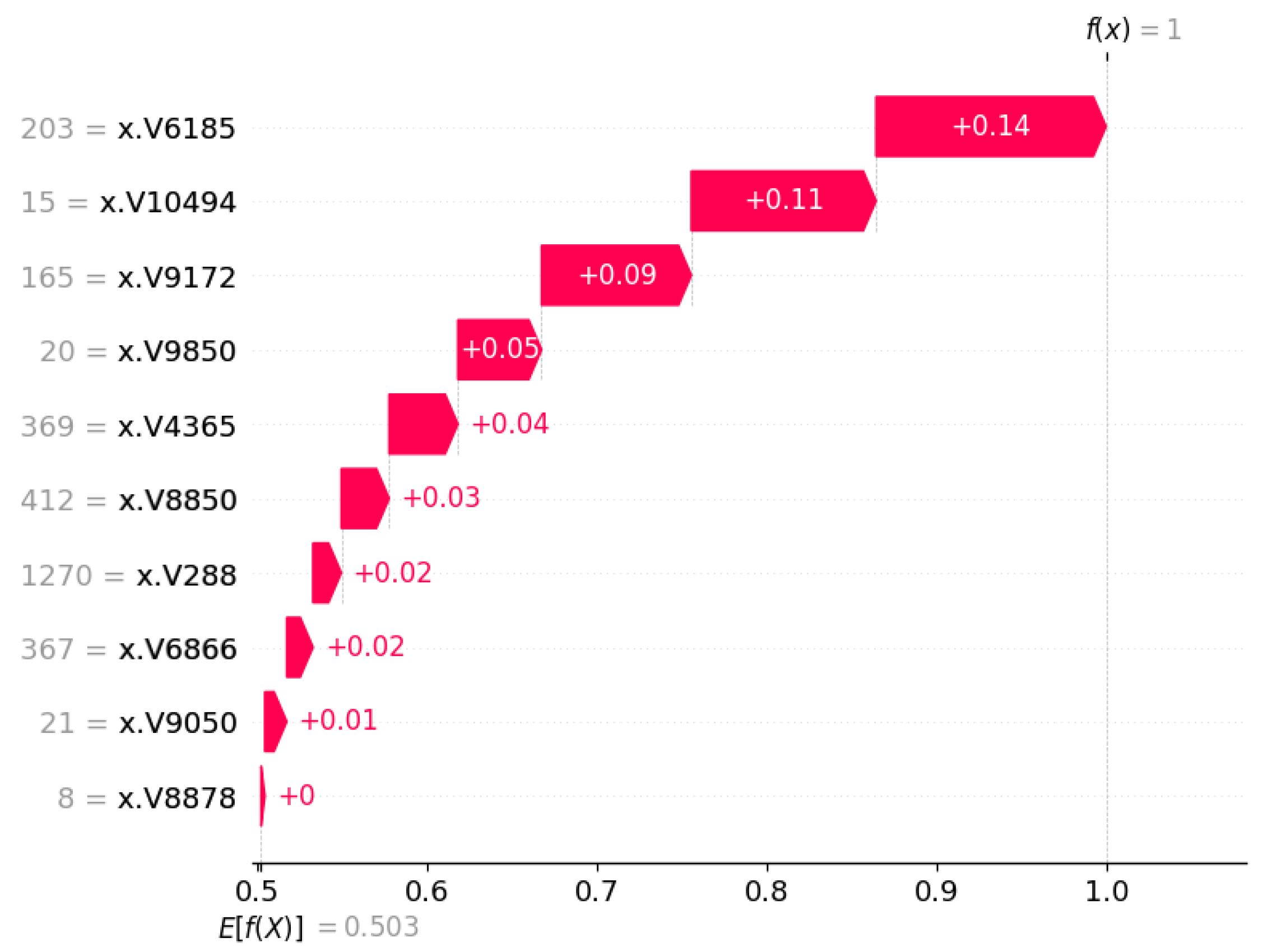

3.3. Outcome Interpretations Using Explainable Machine Learning Pipeline

3.3.1. Global Interpretation—Feature Importance

3.3.2. Local Interpretation

3.4. Tools and Hyper-Parameters of the Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological Significance of Top Genes

4.2. Constraints on Dataset Used for the Study

4.3. Comparative Overview with Other Explainability Models

4.4. Clinical Translational Linkages with PCa Pathways

4.5. Practical Challenges in XML Integration into Clinical Workflows

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R.; Lou, Y.; Gehrke, J.; Koch, P.; Sturm, M.; Elhadad, N. Intelligible models for healthcare: Predicting pneumonia risk and hospital 30-day readmission. In Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10–13 August 2015; pp. 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why should I trust you? Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidey-Gibbons, J.A.M.; Sidey-Gibbons, C.J. Machine learning in medicine: A practical introduction. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperberg, M.R.; Carroll, P.R. Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990–2013. JAMA 2015, 314, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S.; Folkvaljon, Y.; Robinson, D.; Lissbrant, I.F.; Egevad, L.; Stattin, P. Evaluation of the 2015 Gleason grade groups in a nationwide population-based cohort. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraujalis, V.; Ruzgas, T.; Milonas, D. Mortality rate estimation models for patients with prostate cancer diagnosis. Balt. J. Mod. Comput. 2022, 10, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanya, S.V.G.; Shetty, D.K.; Patil, V.; Hameed, B.M.Z.; Paul, R.; Smriti, K.; Naik, N.; Somani, B.K. The role of data science in healthcare advancements: Applications, benefits, and future prospects. Ir. J. Med Sci. 2022, 191, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahabreh, I.J. Randomization, randomized trials, and analyses using observational data: A commentary on Deaton and Cartwright. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 210, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, A.J.; Feudale, R.N.; Liu, Y.; Woody, N.A.; Brown, S.D. An introduction to decision tree modeling. J. Chemom. A J. Chemom. Soc. 2004, 18, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaValley, M.P. Logistic regression. Circulation 2008, 117, 2395–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995; Volume 1, pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Febbo, P.G.; Ross, K.; Jackson, D.G.; Manola, J.; Ladd, C.; Tamayo, P.; Renshaw, A.A.; D’Amico, A.V.; Richie, J.P.; et al. Gene expression correlates of clinical prostate cancer behavior. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomek, I. Two modifications of CNN. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Commun. 1976, 6, 769–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rish, I. An empirical study of the naive Bayes classifier. In Proceedings of the IJCAI 2001 Workshop on Empirical Methods in Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, DC, USA, 4–6 August 2001; Volume 3, pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, C.; da Costa, K.; Modenesi, B.; Koshiyama, A. Local and Global Explainability Metrics for Machine Learning Predictions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.12094. Available online:https://openreview.net/forum?id=ce66vlkdAz (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Lee, H.; Yune, S.; Mansouri, M.; Kim, M.; Tajmir, S.H.; Guerrier, C.E.; Ebert, S.A.; Pomerantz, S.R.; Romero, J.M.; Kamalian, S.; et al. An explainable deep-learning algorithm for the detection of acute intracranial haemorrhage from small datasets. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, T.; Anjaria, K. Applications of game theory in deep learning: A survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 8963–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.G.; Lee, S.-I. Consistent individualized feature attribution for tree ensembles. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03888. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning; Lulu. com: Durham, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, W. pandas: A foundational Python library for data analysis and statistics. Python High Perform. Sci. Comput. 2011, 14, 1–9. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:61539023 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Idris, I. NumPy: Beginner’s Guide, 3rd ed.; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/numpy-beginners-guide/9781785281969/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Tosi, S. Matplotlib for Python Developers; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2009; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Matplotlib-Python-Developers-Sandro-Tosi/dp/1847197906/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Regular Expression Operations. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Scikit-Learn, Machine Learning in Python. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Zeng, M.; Zou, B.; Wei, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Effective prediction of three common diseases by combining SMOTE with Tomek links technique for imbalanced medical data. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference of Online Analysis and Computing Science (ICOACS), Chongqing, China, 28–29 May 2016; pp. 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, G.E.; Bazzan, A.L.C.; Monard, M.-C. Balancing training data for automated annotation of keywords: Case study. In Proceedings of the Second Brazilian Workshop on Bioinformatics, Macae, Brazil, 3–5 December 2003; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- SHAP Waterfall Plot. Available online: https://shap.readthedocs.io/en/latest/example_notebooks/api_examples/plots/waterfall.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ross-Adams, H.; Lamb, A.D.; Dunning, M.J.; Halim, S.; Lindberg, J.; Massie, C.M.; Egevad, L.A.; Russell, R.; Ramos-Montoya, A.; Vowler, S.L.; et al. Integration of copy number and transcriptomics provides risk stratification in prostate cancer: A discovery and validation cohort study. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan-Alexandru, L.; Brewer, D.S.; Edwards, D.R.; Edwards, S.; Whitaker, H.C.; Merson, S.; Dennis, N.; Cooper, R.A.; Hazell, S.; Warren, A.Y.; et al. DESNT: A Poor Prognosis Category of Human Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. Focus 2017, 4, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, K.L.; Sinnott, J.A.; Tyekucheva, S.; Gerke, T.; Shui, I.M.; Kraft, P.; Sesso, H.D.; Freedman, M.L.; Loda, M.; Mucci, L.A.; et al. Association of prostate cancer risk variants with gene expression in normal and tumor tissue. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2015, 24, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbé, D.P.; Zadra, G.; Yang, M.; Reyes, J.M.; Lin, C.Y.; Cacciatore, S.; Ebot, E.M.; Creech, A.L.; Giunchi, F.; Fiorentino, M.; et al. High-fat diet fuels prostate cancer progression by rewiring the metabolome and amplifying the MYC program. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep Inside Convolutional Networks: Visualising Image Classification Models and Saliency Maps. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) Workshop, Banff, AB, Canada, 14–16 April 2014; Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6034 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic Attribution for Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 3319–3328. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v70/sundararajan17a.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, J.T.; Fu, H.; Xia, S.; Hu, Q. Deep-LIFT: Deep label-specific feature learning for image annotation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 7732–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, P.E.; Tindall, D.J. Androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer development and progression. J. Carcinog. 2011, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlins, S.A.; Rhodes, D.R.; Perner, S.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Mehra, R.; Sun, X.-W.; Varambally, S.; Cao, X.; Tchinda, J.; Kuefer, R.; et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science 2005, 310, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, S.V.M.; García-Perdomo, H.A. Diagnostic accuracy of prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3) prior to first prostate biopsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2019, 14, E214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussemakers, M.J.G.; Bokhoven, A.V.; Verhaegh, G.W.; Smit, F.P.; Karthaus, H.F.M.; Schalken, J.A.; Debruyne, F.M.J.; Ru, N.; Isaacs, W.B. Dd3: A new prostate-specific gene, highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 5975–5979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Properties | Description |

|---|---|

| Dataset Availability | Publicly available [14] |

| Platform | Affymetrix |

| Number of Genes | 12,600 |

| Number of Samples | Tumor (52) and Normal (50) |

| Imputation Technique | Precision (SD) | Recall (SD) | F1-Score (SD) | Accuracy (%) (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.7948 (0.0232) | 0.8084 (0.0224) | 0.8015 (0.0227) | 80.92% (1.390%) |

| Median | 0.8001 (0.0203) | 0.8052 (0.0198) | 0.8026 (0.0210) | 80.85% (1.412%) |

| Most Frequent | 0.7923 (0.0245) | 0.8100 (0.0212) | 0.8002 (0.0234) | 81.01% (1.564%) |

| Constant | 0.7867 (0.0251) | 0.8009 (0.0209) | 0.7938 (0.0238) | 80.76% (1.473%) |

| Method/Model | Hyperparameters/Configuration |

|---|---|

| Naive Bayes (NB) | GaussianNB(var_smoothing=1e-9) |

| Decision Tree (DT) | criterion=’gini’, max_depth=None, random_state=42 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | C=1.0, kernel=’rbf’, gamma=’scale’ |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | C=1.0, solver=’lbfgs’, max_iter=1000, random_state=42 |

| Random Forest (RF) | n_estimators=100, max_depth=None, random_state=42 |

| Bagging Classifier | n_estimators=10, base_estimator=DecisionTreeClassifier(), random_state=42 |

| SMOTE (Oversampling) | k_neighbors=5, sampling_strategy=’auto’, random_state=42 |

| Tomek Links (Undersampling) | sampling_strategy=’auto’ |

| SMOTE + Tomek Links | Combination pipeline using SMOTETomek(random_state=42) |

| SHAP (Explainability) | TreeExplainer(model) for tree-based models, KernelExplainer(f, X_background) for black-box models; Interpretation thresholds: SHAP > 0.10 = strong influence, 0.01–0.10 = moderate influence, <0.01 = negligible influence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marouf, A.A.; Rokne, J.G.; Alhajj, R. Identification of Potential Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Microarray Gene Expression Leveraging Explainable Machine Learning Classifiers. Cancers 2025, 17, 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233853

Marouf AA, Rokne JG, Alhajj R. Identification of Potential Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Microarray Gene Expression Leveraging Explainable Machine Learning Classifiers. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233853

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarouf, Ahmed Al, Jon George Rokne, and Reda Alhajj. 2025. "Identification of Potential Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Microarray Gene Expression Leveraging Explainable Machine Learning Classifiers" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233853

APA StyleMarouf, A. A., Rokne, J. G., & Alhajj, R. (2025). Identification of Potential Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Microarray Gene Expression Leveraging Explainable Machine Learning Classifiers. Cancers, 17(23), 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233853