Brain Tumors in Pregnancy: A Review of Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Ethical Dilemmas

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- Peer-reviewed journal articles, reviews, and clinical guidelines published in English from 1990–2025;

- Both retrospective and prospective studies, as well as systematic reviews addressing CNS tumors diagnosed during pregnancy;

- Publications describing diagnostic, therapeutic, prognostic, or ethical aspects of neuro-oncological management.

- Non-peer-reviewed materials;

- Animal studies or in vitro experiments without direct clinical relevance;

- Studies focusing exclusively on non-pregnant populations.

- Study design and patient population;

- Tumor type and clinical presentation;

- Diagnostic and therapeutic approach;

- Maternal and fetal outcomes;

- And ethical or decision-making aspects.

- Epidemiology of brain tumors in pregnancy;

- Pathophysiological mechanisms;

- Clinical presentation and diagnostic features;

- Therapeutic management (conservative and surgical);

- Maternal and fetal prognosis;

- Ethical dilemmas in clinical practice.

- The literature selection was independently verified by multiple co-authors with backgrounds in neurosurgery and obstetrics;

- The analytical process followed transparent documentation of search terms, databases, and inclusion decisions;

- Findings were cross-validated with systematic reviews and meta-analyses when available.

3. Epidemiology of Brain Tumors in Pregnancy

4. Pathophysiology of Brain Tumors During Pregnancy

5. Clinical Presentation of Brain Tumors During Pregnancy

6. Diagnostic Considerations in Brain Tumors During Pregnancy

7. Conservative Management of Brain Tumors During Pregnancy

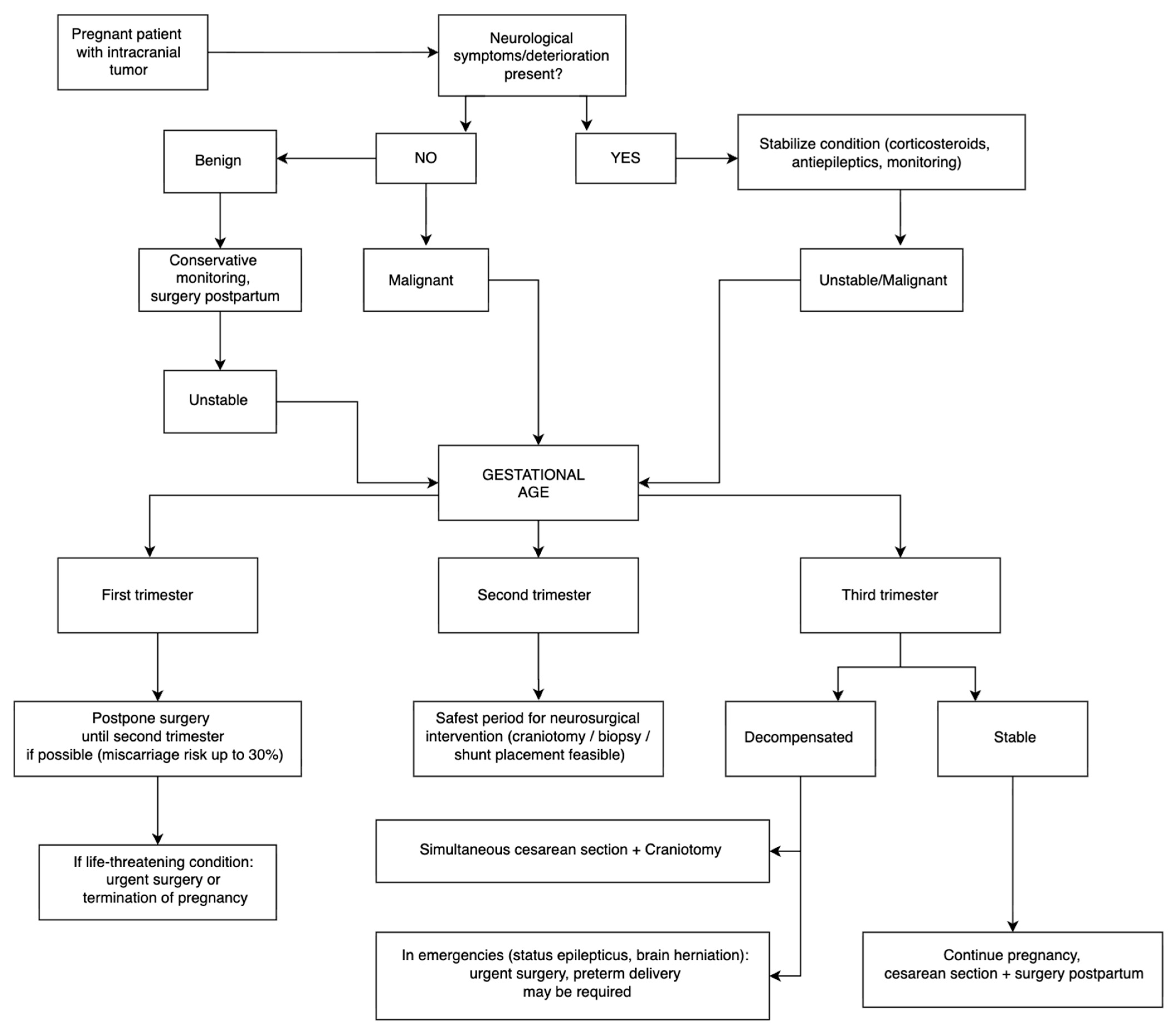

8. Surgical Management of Brain Tumors During Pregnancy

9. Maternal and Fetal Prognosis in Brain Tumors During Pregnancy

10. Ethical Considerations in the Management of Brain Tumors During Pregnancy

11. Limitations

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEER | Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results |

| CBTRUS | Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States |

| PR | Progesterone Receptor |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| JAK2/STAT5 | Janus Kinase 2/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5 |

| MAPK/ERK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| PRLR | Prolactin Receptor |

| ICP | Intracranial Pressure |

| GBCA | Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents |

| KPSS | Karnofsky Performance Status Scale |

| GOS | Glasgow Outcome Scale |

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

| ESMO | European Society for Medical Oncology |

References

- Eckenstein, M.; Thomas, A.A. Benign and malignant tumors of the central nervous system and pregnancy. In Neurology and Pregnancy: Neuro-Obstetric Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 3rd ed.; Steegers, E.A.P., Cipolla, M.J., Miller, E.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 172, pp. 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrikulu, S.; Yarman, S. Outcomes of patients with macroprolactinoma desiring pregnancy: Follow-up to 23 years from a single center. Horm. Metab. Res. 2021, 53, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elsayed, A.A.; Díaz-Gómez, J.; Barnett, G.H.; Kurz, A.; Inton-Santos, M.; Barsoum, S.; Avitsian, R.; Ebrahim, Z.; Jevtovic-Todorovic, V.; Farag, E. A case series discussing the anaesthetic management of pregnant patients with brain tumours [version 2; peer-reviewed article]. F1000Research 2013, 2, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinueza, D.; Rebellón-Sánchez, D.; Llanos, J.; Rosso, F. Cerebral tuberculoma in pregnant women: A systematic review and comprehensive analysis of literature. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohdy, Y.M.; Agam, M.; Maldonado, J.; Jahangiri, A.; Pradilla, G.; Garzon-Muvdi, T. Symptomatic intracranial tumors in pregnancy: An updated management algorithm. J. Neurosurg. Case Lessons 2023, 5, CASE2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson-Segerlind, J.; Mathiesen, T.; Elmi-Terander, A.; Edström, E.; Talbäck, M.; Feychting, M.; Tettamanti, G. The risk of developing a meningioma during and after pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, C.M.; Engh, J.A. Pregnancy and brain tumors. Neurol. Clin. 2012, 30, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, A.; Alvarez, F.; Gonzalez, A.; Garcia-Grande, A.; Perez-Alvarez, M.; Garcia-Blazquez, M. Brain tumor and pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 89, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.J.; Waldrop, A.R.; Suharwardy, S.; Druzin, M.L.; Iv, M.; Ansari, J.R.; Stone, S.A.; Jaffe, R.A.; Jin, M.C.; Li, G.; et al. Management of Brain Tumors Presenting in Pregnancy: A Case Series and Systematic Review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 3, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Truitt, G.; Boscia, A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20 (Suppl. S4), iv1–iv86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowppli-Bony, A.; Bouvier, G.; Rué, M.; Loiseau, H.; Vital, A.; Lebailly, P.; Fabbro-Peray, P.; Baldi, I. Brain tumors and hormonal factors: Review of the epidemiological literature. Cancer Causes Control. 2011, 22, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemels, J.; Wrensch, M.; Claus, E.B. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2010, 99, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea-Soriano, L.; Wallander, M.A.; García Rodríguez, L.A. Epidemiology of meningioma in the United Kingdom. Neuroepidemiology 2012, 39, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelvink, N.C.; Kamphorst, W.; van Urk, H.; Gispen, J.G. Pregnancy-related primary brain and spinal tumors. Arch. Neurol. 1987, 44, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitch, M.E. Pituitary tumors and pregnancy. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2003, 13 (Suppl. SA), S38–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yust-Katz, S.; de Groot, J.F.; Liu, D.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Anderson, M.D.; Conrad, C.A.; Milbourne, A.; Gilbert, M.R.; Armstrong, T.S. Pregnancy and glial brain tumors. Neuro-Oncology 2014, 16, 1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Botello, D.; Rodríguez-Sanchez, J.R.; Cuevas-García, J.; Cárdenas-Almaraz, B.V.; Morales-Acevedo, A.; Mejía-Pérez, S.I.; Ochoa-Martinez, E. Pregnancy and brain tumors: A systematic review of the literature. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 86, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortobágyi, T.; Bencze, J.; Murnyák, B.; Kouhsari, M.C.; Bognár, L.; Marko-Varga, G. Pathophysiology of meningioma growth in pregnancy. Open Med. 2017, 12, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurcay, A.G.; Bozkurt, I.; Senturk, S.; Kazanci, A.; Gurcan, O.; Turkoglu, O.F.; Beskonakli, E. Diagnosis, treatment, and management strategy of meningioma during pregnancy. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2018, 13, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.C.; Gouvêa, F.; Emmerich, J.C.; Kokinovrachos, G.; Pereira, C.; Welling, L.; Kislanov, S. Management strategy for brain tumour diagnosed during pregnancy. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 25, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, S.T.; Gelperin, K.; Sahin, L.; Bleich, K.B.; Fazio-Eynullayeva, E.; Woods, C.; Radden, E.; Greene, P.; McCloskey, C.; Johnson, T.; et al. First-trimester exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents: A utilization study of 4.6 million U.S. Pregnancies. Radiology 2019, 293, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecaveye, V.; Amant, F.; Lecouvet, F.; Van Calsteren, K.; Dresen, R.C. Imaging modalities in pregnant cancer patients. Imaging modalities in pregnant cancer patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021, 31, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviv, Y.; Ohla, V.; Kasper, E.M. Unique features of pregnancy-related meningiomas: Lessons learned from 148 reported cases and theoretical implications of a prolactin modulated pathogenesis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2016, 41, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasad, A.; Nicola Candia, A.J.; Gonzalez, N.; Zuccato, C.F.; Seilicovich, A.; Candolfi, M. The role of the prolactin receptor pathway in the pathogenesis of glioblastoma: What do we know so far? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2020, 24, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, A.R.; Barker, F.G.; Leffert, L.; Bateman, B.T.; Souter, I.; Plotkin, S.R. Outcomes of hospitalization in pregnant women with CNS neoplasms: A population-based study. Neuro-Oncology 2012, 14, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haan, J.; Vandecaveye, V.; Han, S.N.; Van de Vijver, K.K.; Amant, F. Difficulties with diagnosis of malignancies in pregnancy. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 33, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lum, M.; Tsiouris, A.J. MRI safety considerations during pregnancy. Clin. Imaging 2020, 62, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CT and MR Pregnancy Guidelines. UCSF Radiology Guidelines. 2024. Internal Clinical Document, University of California, San Francisco. Available online: https://radiology.ucsf.edu/patient-care/patient-safety/ct-mri-pregnancy#accordion-managing-pregnant-patients-who-are-irradiated (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Nguyen, T.; Bhosale, P.R.; Cassia, L.; Surabhi, V.; Javadi, S.; Milbourne, A.; Faria, S.C. Malignancy in pregnancy: Multimodality imaging and treatment. Cancer 2023, 129, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, L.M.; Yoshizumi, T.T.; Reiman, R.E.; Goodman, P.C.; Paulson, E.K.; Frush, D.P.; Toncheva, G.; Nguyen, G.; Barnes, L. Radiation dose to the fetus from body MDCT during early gestation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006, 186, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiesińska-Figatowska, M.; Romaniuk-Doroszewska, A.; Szkudlińska-Pawlak, S.; Duczkowska, A.; Mądzik, J.; Szopa-Krupińska, M.; Maciejewski, T.M. Diagnostic imaging of pregnant women—The role of magnetic resonance imaging. Pol. J. Radiol. 2017, 82, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; Schander, J.A.; Bariani, M.V.; Correa, F.; Rubio, A.P.D.; Cella, M.; Cymeryng, C.B.; Wolfson, M.L.; Franchi, A.M.; Aisemberg, J. Dexamethasone-induced intrauterine growth restriction modulates expression of placental vascular growth factors and fetal and placental growth. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 27, gaab006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, M.W.; Newnham, J.P.; Challis, J.G.; Jobe, A.H.; Stock, S.J. The clinical use of corticosteroids in pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadabad, H.N.; Jafari, S.K.; Firizi, M.N.; Abbaspour, A.R.; Gharib, F.G.; Ghobadi, Y.; Gholizadeh, S. Pregnancy outcomes following the administration of high doses of dexamethasone in early pregnancy. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2016, 43, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laviv, Y.; Bayoumi, A.; Mahadevan, A.; Young, B.; Boone, M.; Kasper, E.M. Meningiomas in pregnancy: Timing of surgery and clinical outcomes as observed in 104 cases and establishment of a best management strategy. Acta Neurochir. 2018, 160, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Gadol, A.A.; Friedman, J.A.; Friedman, J.D.; Tubbs, R.S.; Munis, J.R.; Meyer, F.B. Neurosurgical management of intracranial lesions in the pregnant patient: A 36-year institutional experience and review of the literature. J. Neurosurg. 2009, 111, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, K.S.; Cappuccini, F.; Asrat, T.; Flamm, B.L.; Carpenter, S.E.; DiSaia, P.J.; Quilligan, E.J. Obstetric emergencies precipitated by malignant brain tumors. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 182, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proskynitopoulos, P.J.; Lam, F.C.; Sharma, S.; Young, B.C.; Laviv, Y.; Kasper, E.M. A review of the neurosurgical management of brain metastases during pregnancy. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 48, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofatteh, M.; Mashayekhi, M.S.; Arfaie, S.; Wei, H.; Kazerouni, A.; Skandalakis, G.P.; Pour-Rashidi, A.; Baiad, A.; Elkaim, L.; Lam, J.; et al. Awake Craniotomy during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Neurosurg. Rev. 2023, 46, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, D.; Lu, Y.; Hao, B.; Cao, Y. Preoperative embolization versus direct surgery of meningiomas: A meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019, 128, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, M.; Uksul, N.; Hong, B.; von Kaisenberg, C.; Scheinichen, D.; Lang, J.M.; Hermann, E.J.; Hillemanns, P.; Krauss, J.K. Intracranial emergencies during pregnancy requiring urgent neurosurgical treatment. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 195, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffert, L.R.; Clancy, C.R.; Bateman, B.T.; Cox, M.; Schulte, P.J.; Smith, E.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; Schwamm, L.H.; Kuklina, E.V.; George, M.G.; et al. Patient characteristics and outcomes after hemorrhagic stroke in pregnancy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2015, 8 (Suppl. S3), S170–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Committee on Ethics. Ethical decision making in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervenak, F.A.; McCullough, L.B. Current Ethical Challenges in Obstetric and Gynecologic Practice, Research and Education, 1st ed.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers: Coimbatore, India, 2019; ISBN 978-93-5270-595-5. [Google Scholar]

- Linkeviciute, A.; Canario, R.; Peccatori, F.A.; Dierickx, K. Guidelines for Cancer Treatment during Pregnancy: Ethics-Related Content Evolution and Implications for Clinicians. Cancers 2022, 14, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Critical Care Decisions in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine: Ethical Issues; Nuffield Council on Bioethics: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 1-904384-14-5. Available online: http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Dotters-Katz, S.K.; McNeil, M.; Limmer, J.; Kuller, J. Cancer and pregnancy: The clinician’s perspective. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2014, 69, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chervenak, F.A.; McCullough, L.B. Ethics in obstetrics and gynecology: An overview. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1997, 75, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Number of Patients | Trimester of Operation | Intervention | Delivery | Histology | Maternal Outcome | Perinatal Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [38] | 1 | I | VP shunt for hydrocephalus after TAB | TAB at 9 weeks GA | Melanoma MTS | Mother succumbed to malignant cerebral edema. | N/A |

| 3 | II | Resection of cerebellar mass; palliative RT + chemo postpartum | C/S at 30 weeks GA | Breast cancer MTS | Mother and child are alive at the time of study termination. | ||

| Chemo at 9 weeks GA; craniotomy at 16 and 27 weeks GA; chemo at 22 weeks GA; RT at 30 weeks GA | C/S at 32 weeks GA. | Breast cancer MTS | Mother and child are alive and healthy at 6 weeks follow-up. | ||||

| Craniotomy + GTR of frontal met at 24 weeks GA; postop RT (GKRS) at 25 weeks GA | C/S at 36 weeks GA. | Breast cancer MTS | Mother and child are alive and well at 3.5 years follow-up. | ||||

| 1 | III | GTR at 24 weeks GA (2nd preg) + postop RT (5 fx) with maternal–fetal shielding | N/A | Lung cancer MTS | N/A | N/A | |

| 3 | Postpartum | Chemo during preg; post fossa decompression + RT + SRS; lapatinib + capecitabine postpartum | Forceps delivery at 37 weeks GA | Breast cancer MTS | Mother and child are alive at the time of study termination. | ||

| Resection of temporal mts after delivery of 1st preg | C/S at 36 weeks GA | Recurrent breast cancer MTS | N/A | The first child is alive and well at 5 years of age. | |||

| Emergency craniotomy for raised ICP + cerebellar lesion resection postpartum | C/S at 38 weeks GA | Alveolar soft tissue sarcoma MTS | Mother and child are alive and well at 10 months follow-up. | ||||

| [39] | 2 | I | AC + GTR | C/S at 34 weeks GA | Giant cell glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) | N/A | Fetus stable post-op; delivered at 34 weeks; healthy at 5 mo FU |

| AC + TR | N/A | Meningioma | Symptom resolution, stable hemodynamics | Fetus stable post-op | |||

| 5 | II | AC + TR | N/A | Glioma | Patient deceased 16 months after craniotomy | Viable infant with normal Apgar score | |

| AC + TR | Vaginal at term | Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (WHO grade III) | No deficits | Fetus stable post-op | |||

| AC + TR | Vaginal at term | Anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO grade III) | N/A | Fetus stable post-op | |||

| AC + TR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Fetus stable post-op | |||

| AC + TR | N/A | Astrocytoma (Grade II/III) | N/A | Fetus stable post-op | |||

| 1 | III | AC + TR—Two general anesthesia tumor debulking during the same pregnancy at 16 weeks and 28 weeks gestation | Vaginal (twins) at term | Anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO grade III) | No complication | Twins delivered post-op 4th day under spinal anesthesia. | |

| [36] | 3 | I | Stereo Bx TAB + XRT and chemo | TAB | Grade III astro | TAB at 4 weeks in preparation for XRT and chemo | 5 by GOS |

| VP shunt → TAB + XRT | TAB (2 weeks after shunt) | Intraventricular tumor (no tissue) | Therapeutic abortion at 2 weeks after shunt placement | 5 by GOS | |||

| Craniotomy + Resection + XRT | N/A | GBM | N/A | 5 by GOS | |||

| 6 | II | Craniotomy + Resection + XRT | N/A | GBM | N/A | 4 by GOS | |

| Stereo Bx + XRT; chemo postpartum | NSVD | Grade III astro | Normal | 5 by GOS | |||

| Craniotomy + Resection | NSVD | Grade II astro | Normal | 5 by GOS | |||

| Craniotomy + Resection | Pregnancy in progress | Meningioma | N/A | N/A | |||

| Ventriculoatrial shunt → TAB + XRT/chemo | TAB 6 days after shunt placement | Infiltrative pineal tumor (no tissue) | TAB | 4 by GOS | |||

| Emergency C/S → Craniotomy + Resection 12 h later | Emergency C/S | Meningioma | Normal | 5 by GOS | |||

| 1 | III | XRT | NSVD | Thalamic tumor (GBM at autopsy) | Normal | 1 by GOS | |

| Tumor Type | Preferred Management | Optimal Timing (Trimester) | Maternal Outcome | Fetal Outcome | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meningioma | Surgical resection if neurological deterioration; conservative otherwise | 2nd trimester | Excellent (no maternal mortality in reviewed series) | Good (>95% live births) | [23] |

| Glioma | Case-by-case; surgery for high-grade or symptomatic lesions | 2nd trimester | Variable (depends on grade) | Good if gestational age > 28 weeks | [37] |

| Pituitary adenoma | Medical management; surgery rare | 3rd trimester or postpartum | Excellent | Excellent | [15] |

| Metastatic tumors | Palliative or combined management; chemo after 2nd trimester | Any (if indicated) | Favorable (depends on primary site) | Excellent | [38] |

| Overall | Multidisciplinary individualized approach | 2nd trimester safest for surgery | Maternal survival ~95% | Fetal survival > 90% | Summary from current review |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tleubergenov, M.A.; Zhamoldin, D.K.; Baymukhanov, D.S.; Omarova, A.S.; Ryskeldiyev, N.A.; Doskaliyev, A.; Ukybassova, T.M.; Akshulakov, S. Brain Tumors in Pregnancy: A Review of Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Ethical Dilemmas. Cancers 2025, 17, 3854. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233854

Tleubergenov MA, Zhamoldin DK, Baymukhanov DS, Omarova AS, Ryskeldiyev NA, Doskaliyev A, Ukybassova TM, Akshulakov S. Brain Tumors in Pregnancy: A Review of Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Ethical Dilemmas. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3854. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233854

Chicago/Turabian StyleTleubergenov, Muratbek A., Daniyar K. Zhamoldin, Dauren S. Baymukhanov, Assel S. Omarova, Nurzhan A. Ryskeldiyev, Aidos Doskaliyev, Talshyn M. Ukybassova, and Serik Akshulakov. 2025. "Brain Tumors in Pregnancy: A Review of Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Ethical Dilemmas" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3854. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233854

APA StyleTleubergenov, M. A., Zhamoldin, D. K., Baymukhanov, D. S., Omarova, A. S., Ryskeldiyev, N. A., Doskaliyev, A., Ukybassova, T. M., & Akshulakov, S. (2025). Brain Tumors in Pregnancy: A Review of Pathophysiology, Clinical Management, and Ethical Dilemmas. Cancers, 17(23), 3854. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233854