Targeting CXCR6 Disrupts β-Catenin Signaling and Enhances Sorafenib Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

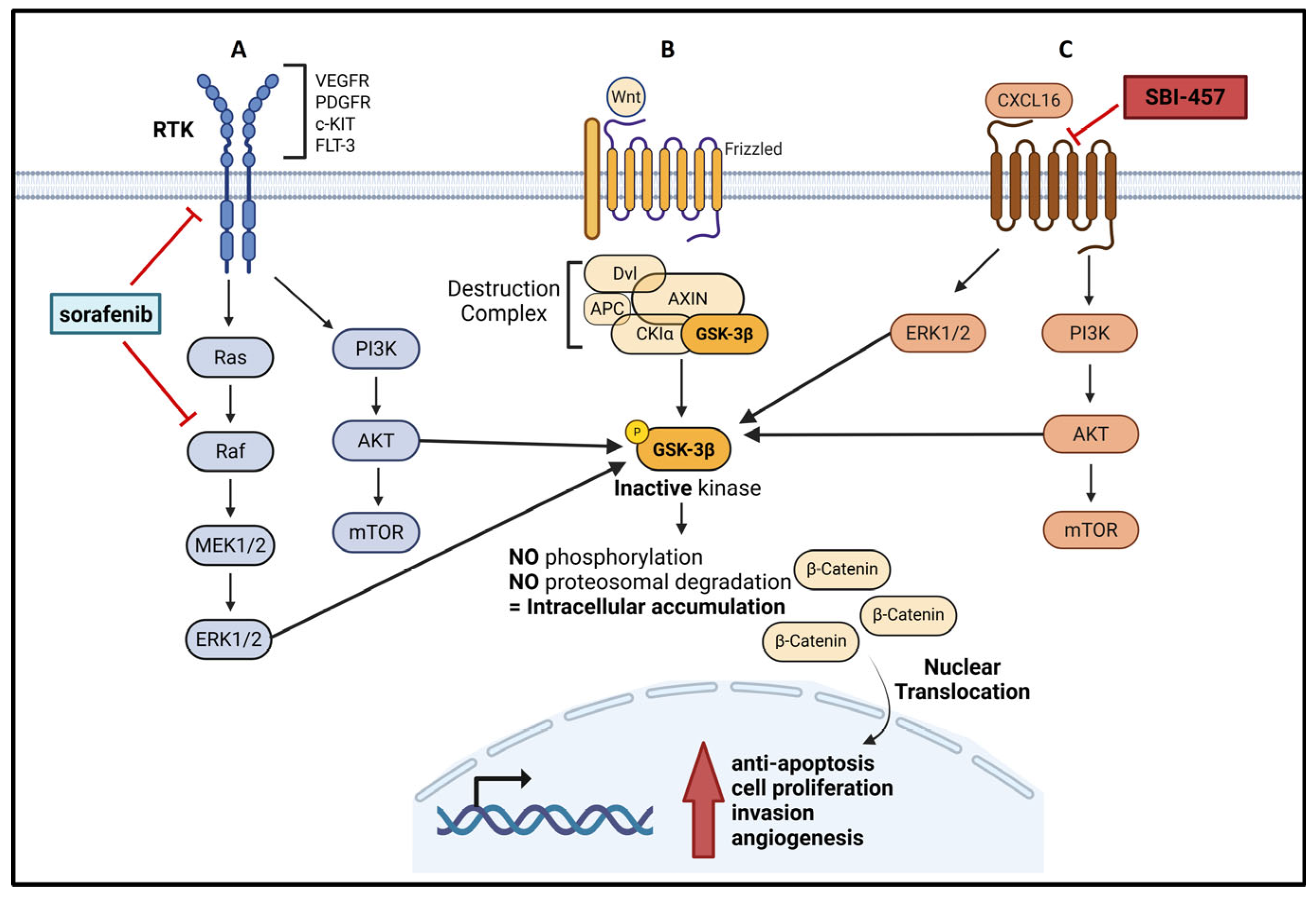

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

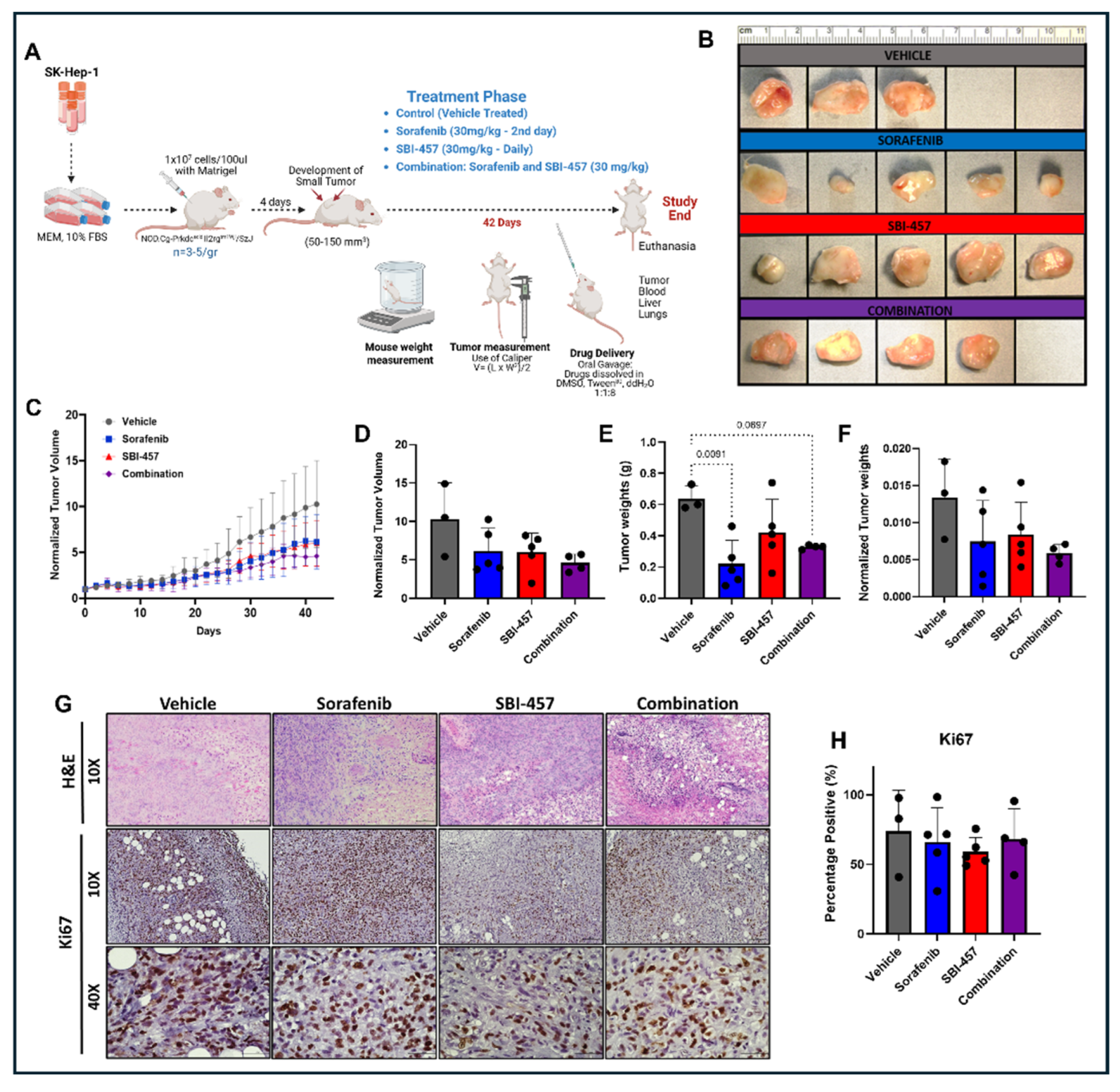

2.2. Xenograft Model

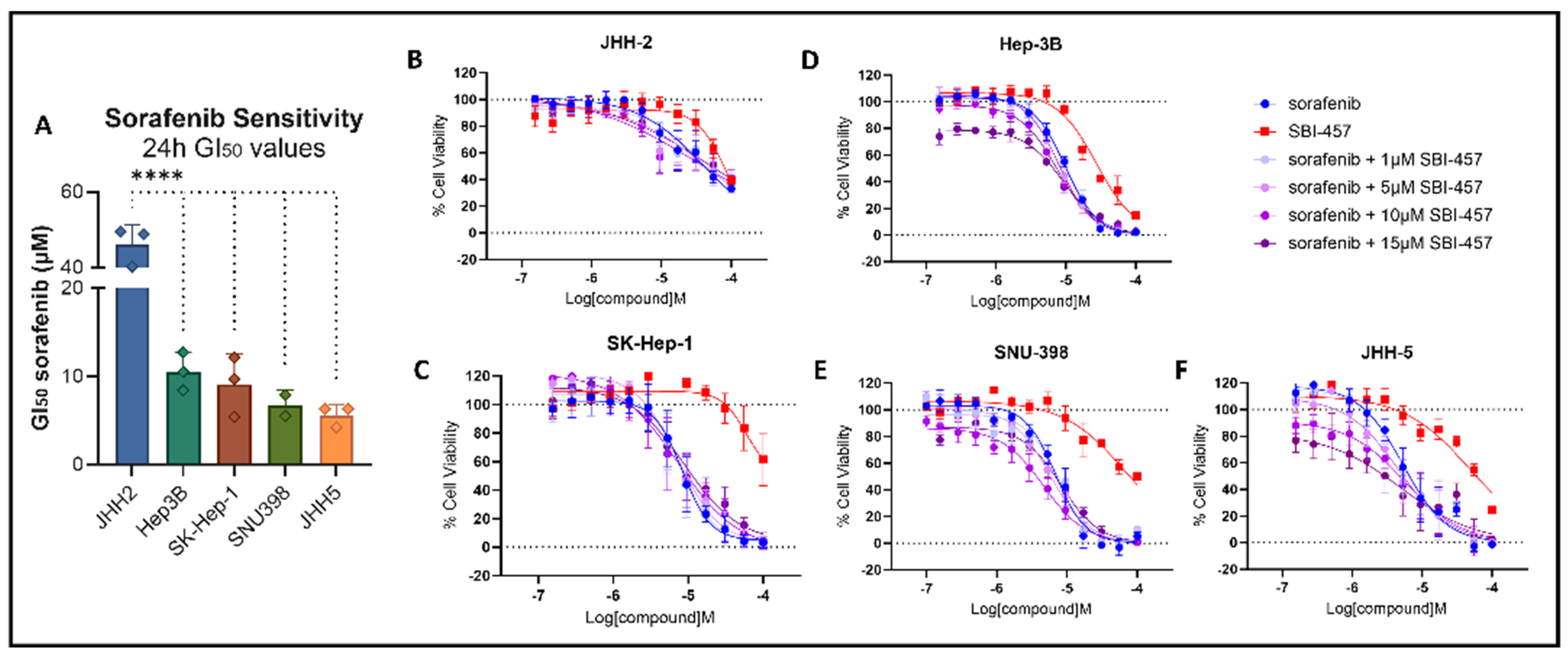

2.3. Drug Treatment and Viability Assays

2.4. Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

2.5. Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

2.6. ELISA for Soluble CXCL16

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. CXCR6 Antagonism with SBI-457 Reduces Tumor Growth In Vivo

3.2. SBI-457 Attenuates Sorafenib-Induced β-Catenin Activation and Modulates GSK3β

3.3. SBI-457 Blocks Nuclear Accumulation of β-Catenin in SK-Hep-1 Cells

3.4. CXCR6 Antagonism Enhances Sorafenib-Mediated Cell Death in Select HCC Cell Lines

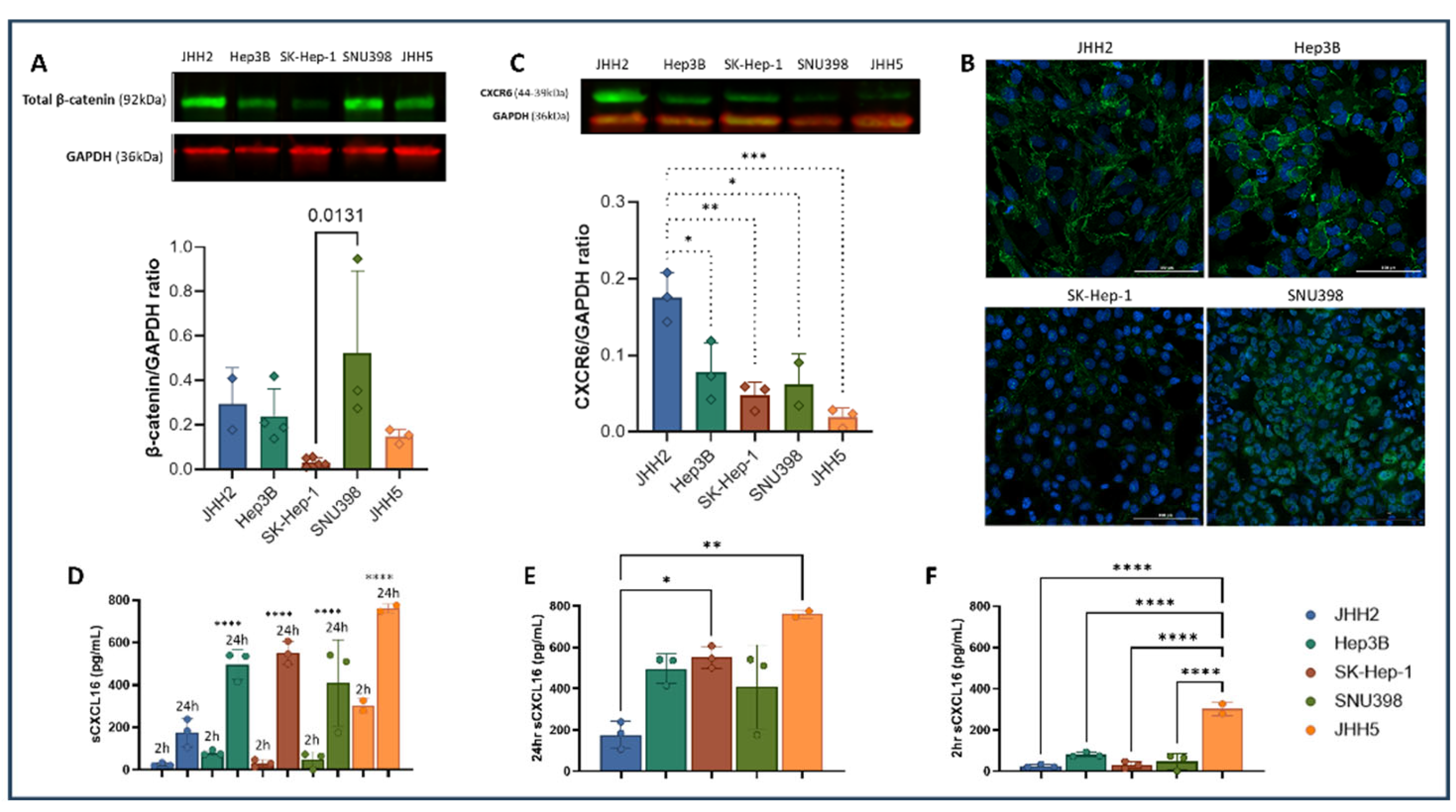

3.5. Response to Combination Therapy Correlates with CXCL16 Secretion and CXCR6 Isoform Expression

4. Discussion

4.1. CXCR6/β-Catenin Crosstalk and Resistance

4.2. CXCR6/GSK3β/β-Catenin Crosstalk

4.3. Differential Responses Across HCC Models

4.4. Experimental Rationale and Future in Vivo Validation

4.5. Implications for Biomarker-Guided Therapy

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAM | A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic Acid |

| BME | Basement Membrane Extract |

| CDX | Cell-Line-Derived Xenograft |

| CHO | Chinese Hamster Ovary |

| CXCR6 | C-X-C Chemokine Receptor 6 |

| CXCL16 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 16 |

| DAB | 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FFPE | Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded |

| GI50 | 50% Growth Inhibition Concentration |

| GPCR | G Protein-Coupled Receptor |

| GSK3β | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| HRP | Horseradish Peroxidase |

| IF | Immunofluorescence |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| LEF | Lymphoid Enhancer Factor |

| MEM | Minimum Essential Medium |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2-5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| NE-PER | Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NSG | NOD scid gamma (mice) |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| pCREB | Phosphorylated cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene Difluoride |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium 1640 |

| SBI-457 | Small-Molecule CXCR6 Antagonist |

| sCXCL16 | Soluble CXCL16 |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TCF | T-Cell Factor |

| tmCXCL16 | Transmembrane CXCL16 |

References

- Desert, R.; Gianonne, F.; Saviano, A.; Hoshida, Y.; Heikenwälder, M.; Nahon, P.; Baumert, T.F. Improving immunotherapy for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: Learning from patients and preclinical models. npj Gut Liver 2025, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabrouk, N.; Tran, T.; Sam, I.; Pourmir, I.; Gruel, N.; Granier, C.; Pineau, J.; Gey, A.; Kobold, S.; Fabre, E.; et al. CXCR6 expressing T cells: Functions and role in the control of tumors. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1022136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Zhao, Y.-J.; Wang, X.-Y.; Qiu, S.-J.; Shi, Y.-H.; Sun, J.; Yi, Y.; Shi, J.-Y.; Shi, G.-M.; Ding, Z.-B.; et al. CXCR6 Upregulation Contributes to a Proinflammatory Tumor Microenvironment That Drives Metastasis and Poor Patient Outcomes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Bajdak-Rusinek, K.; Kupnicka, P.; Kapczuk, P.; Simińska, D.; Chlubek, D.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. The Role of CXCL16 in the Pathogenesis of Cancer and Other Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-M.; Weng, M.-Z.; Song, F.-B.; Chen, J.-Y.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Qin, J.; Jin, T.; Wang, X.-L. Blockade of the CXCR6 Signaling Inhibits Growth and Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells through Inhibition of the VEGF Expression. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2014, 27, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddibhotla, S.; Hershberger, P.M.; Kirby, R.J.; Sugarman, E.; Maloney, P.R.; Sessions, E.H.; Divlianska, D.; Morfa, C.J.; Terry, D.; Pinkerton, A.B.; et al. Discovery of small molecule antagonists of chemokine receptor CXCR6 that arrest tumor growth in SK-HEP-1 mouse xenografts as a model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Ricci, S.; Mazzaferro, V.; Hilgard, P.; Gane, E.; Blanc, J.-F.; De Oliveira, A.C.; Santoro, A.; Raoul, J.-L.; Forner, A.; et al. Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.-L.; Kang, Y.-K.; Chen, Z.; Tsao, C.-J.; Qin, S.; Kim, J.S.; Luo, R.; Feng, J.; Ye, S.; Yang, T.-S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Lau, G.; Kudo, M.; Chan, S.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Furuse, J.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Kang, Y.-K.; Van Dao, T.; De Toni, E.N.; et al. Tremelimumab plus Durvalumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. NEJM Évid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.H.; Brewer, J.R.; Fan, J.; Cheng, J.; Shen, Y.-L.; Xiang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Lemery, S.J.; Pazdur, R.; Kluetz, P.G.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Tremelimumab in Combination with Durvalumab for the Treatment of Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 30, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves Nivolumab with Ipilimumab for Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-nivolumab-ipilimumab-unresectable-or-metastatic-hepatocellular-carcinoma (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Shen, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y. Phosphorylated ERK is a potential predictor of sensitivity to sorafenib when treating hepatocellular carcinoma: Evidence from an in vitrostudy. BMC Med. 2009, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braconi, C.; Valeri, N.; Gasparini, P.; Huang, N.; Taccioli, C.; Nuovo, G.; Suzuki, T.; Croce, C.M.; Patel, T. Hepatitis C Virus Proteins Modulate MicroRNA Expression and Chemosensitivity in Malignant Hepatocytes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eritja, N.; Chen, B.-J.; Rodríguez-Barrueco, R.; Santacana, M.; Gatius, S.; Vidal, A.; Martí, M.D.; Ponce, J.; Bergadà, L.; Yeramian, A.; et al. Autophagy orchestrates adaptive responses to targeted therapy in endometrial cancer. Autophagy 2017, 13, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, Y.; Kanda, T.; Nakamura, M.; Nakamoto, S.; Sasaki, R.; Takahashi, K.; Wu, S.; Yokosuka, O. Overexpression of c-Jun contributes to sorafenib resistance in human hepatoma cell lines. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tian, C.; Puszyk, W.M.; O Ogunwobi, O.; Cao, M.; Wang, T.; Cabrera, R.; Nelson, D.R.; Liu, C. OPA1 downregulation is involved in sorafenib-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 93, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, R.; Kanda, T.; Fujisawa, M.; Matsumoto, N.; Masuzaki, R.; Ogawa, M.; Matsuoka, S.; Kuroda, K.; Moriyama, M. Different Mechanisms of Action of Regorafenib and Lenvatinib on Toll-Like Receptor-Signaling Pathways in Human Hepatoma Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-F.; Tai, W.-T.; Liu, T.-H.; Huang, H.-P.; Lin, Y.-C.; Shiau, C.-W.; Li, P.-K.; Chen, P.-J.; Cheng, A.-L. Sorafenib Overcomes TRAIL Resistance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells through the Inhibition of STAT3. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5189–5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhuang, B.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ge, C.; Yu, M.; Yu, S.; Lin, H. Hypoxia-induced HIF1A impairs sorafenib sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma through NSUN2-mediated stabilization of GDF15. Cell. Signal. 2025, 135, 112076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.A.; Verzeroli, C.; Suarez, A.A.R.; Farca-Luna, A.-J.; Tonon, L.; Esteban-Fabró, R.; Pinyol, R.; Plissonnier, M.-L.; Chicherova, I.; Dubois, A.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma hosts cholinergic neural cells and tumoral hepatocytes harboring targetable muscarinic receptors. JHEP Rep. 2024, 7, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wu, F.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Rong, D.; Reiter, F.P.; et al. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: Theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, E.H.; El Gayar, A.M.; El-Magd, N.F.A. Insights into Sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanisms and therapeutic aspects. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2025, 212, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Wang, P.; Shao, H. Natural Bioactive Compounds Targeting the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2025, 12, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Galarreta, M.R.; Bresnahan, E.; Molina-Sánchez, P.; Lindblad, K.E.; Maier, B.; Sia, D.; Puigvehi, M.; Miguela, V.; Casanova-Acebes, M.; Dhainaut, M.; et al. β-Catenin Activation Promotes Immune Escape and Resistance to Anti–PD-1 Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, D. Nek2 augments sorafenib resistance by regulating the ubiquitination and localization of β-catenin in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ye, X.; Zhang, J.-B.; Ouyang, H.; Shen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Tao, S.; Yang, X.; et al. PROX1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and sorafenib resistance by enhancing β-catenin expression and nuclear translocation. Oncogene 2015, 34, 5524–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, D.; Ling, A.; Han, Z.; Cui, J.; Cheng, J.; Feng, Y.; Liu, W.; Gong, W.; Xia, Y.; et al. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin increases anti-tumor activity by synergizing with sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pellegars-Malhortie, A.; Lasorsa, L.P.; Mazard, T.; Granier, F.; Prévostel, C. Why Is Wnt/β-Catenin Not Yet Targeted in Routine Cancer Care? Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Kimelman, D. Mechanistic insights from structural studies of β-catenin and its binding partners. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 3337–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Qu, Y.; Ke, X. Is β-Catenin a Druggable Target for Cancer Therapy? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Chao, C.C.-K. Identification of the β-catenin/JNK/prothymosin-alpha axis as a novel target of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38999–39017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Feng, W.-C.; Lu, L.-C.; Shao, Y.-Y.; Hsu, C.-H.; Cheng, A.-L. Inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway improves the anti-tumor effects of sorafenib against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2016, 381, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, N.; Mir, H.; Sonpavde, G.P.; Jain, S.; Bae, S.; Lillard, J.W.; Singh, S. Prostate cancer cells hyper-activate CXCR6 signaling by cleaving CXCL16 to overcome effect of docetaxel. Cancer Lett. 2019, 454, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yu, C.; Li, F.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Ye, L. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancers and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Shi, C.; Jiang, L.; Tolstykh, T.; Cao, H.; Bangari, D.S.; Ryan, S.; Levit, M.; Jin, T.; Mamaat, K.; et al. Oncogenic dependency on β-catenin in liver cancer cell lines correlates with pathway activation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 114526–114539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, M.; Lu, L.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Y. Drug resistance mechanism of kinase inhibitors in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1097277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, S.A.; Tiirikainen, M. Beta-catenin activation and immunotherapy resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanisms and biomarkers. Hepatoma Res. 2021, 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, A.D.; Duarte, S.; Sahin, I.; Zarrinpar, A. Mechanisms of drug resistance in HCC. Hepatology 2023, 79, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muche, S.; Kirschnick, M.; Schwarz, M.; Braeuning, A. Synergistic effects of β-catenin inhibitors and sorafenib in hepatoma cells. Anticancer. Res. 2014, 34, 4677–4683. [Google Scholar]

- Desbois-Mouthon, C. Dysregulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology 2002, 36, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Le, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Shen, F. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3β Is Associated with the Prognosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and May Mediate the Influence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, R.; Zhao, J.; Yao, Z.; Cai, Y.; Shou, C.; Lou, D.; Zhou, L.; Qian, Y. Knockdown of Obg-like ATPase 1 enhances sorafenib sensitivity by inhibition of GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2022, 13, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenoue, T.; Ijichi, H.; Kato, N.; Kanai, F.; Masaki, T.; Rengifo, W.; Okamoto, M.; Matsumura, M.; Kawabe, T.; Shiratori, Y.; et al. Analysis of the β-Catenin/T Cell Factor Signaling Pathway in 36 Gastrointestinal and Liver Cancer Cells. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2002, 93, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.-Y.; Kim, C.-M.; Park, Y.-M.; Ryu, W.-S. Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential for the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hepatoma cells. Hepatology 2004, 39, 1683–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fako, V.; Yu, Z.; Henrich, C.J.; Ransom, T.; Budhu, A.S.; Wang, X.W. Inhibition of wnt/β-catenin Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by an Antipsychotic Drug Pimozide. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 12, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zhuang, B.; Zhang, H.; Yan, H.; Xiao, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Q.; Hu, K.; Koeffler, H.P.; et al. Hepatitis B Virus X Protein (HBx) Is Responsible for Resistance to Targeted Therapies in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Ex Vivo Culture Evidence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4420–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darash-Yahana, M.; Gillespie, J.W.; Hewitt, S.M.; Chen, Y.-Y.K.; Maeda, S.; Stein, I.; Singh, S.P.; Bedolla, R.B.; Peled, A.; Troyer, D.A.; et al. The Chemokine CXCL16 and Its Receptor, CXCR6, as Markers and Promoters of Inflammation-Associated Cancers. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bild, A.H.; Yao, G.; Chang, J.T.; Wang, Q.; Potti, A.; Chasse, D.; Joshi, M.-B.; Harpole, D.; Lancaster, J.M.; Berchuck, A.; et al. Oncogenic pathway signatures in human cancers as a guide to targeted therapies. Nature 2006, 439, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.-P.; Qin, B.-D.; Jiao, X.-D.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zang, Y.-S. New clinical trial design in precision medicine: Discovery, development and direction. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ma, Y.; Luo, J.; Xu, K.; Tian, P.; Lu, C.; Song, J. Blocking the WNT/β-catenin pathway in cancer treatment:pharmacological targets and drug therapeutic potential. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Streiff, H.; Gonzalez, I.; Adekoya, O.O.; Silva, I.; Shenoy, A.K. Wnt Pathway-Targeted Therapy in Gastrointestinal Cancers: Integrating Benchside Insights with Bedside Applications. Cells 2025, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peddibhotla, S.; Hershberger, P.M.; Kirby, R.J.; Malany, S.; Smith, L.H.; Maloney, P.R.; Sessions, H.; Divlianska, D.; Pinkerton, A.B. Preparation of Azabicyclononanes and Diazabicyclononanes as CXCR6 Inhibitors and Methods of Use. WO Patent No.WO/2021/007208, 14 January 2021. US20220402908, 22 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reeves, M.; Chambers, A.; Shrestha, A.; Duarte, S.; Zarrinpar, A.; Malany, S.; Peddibhotla, S. Targeting CXCR6 Disrupts β-Catenin Signaling and Enhances Sorafenib Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233818

Reeves M, Chambers A, Shrestha A, Duarte S, Zarrinpar A, Malany S, Peddibhotla S. Targeting CXCR6 Disrupts β-Catenin Signaling and Enhances Sorafenib Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233818

Chicago/Turabian StyleReeves, Morgan, Anastasia Chambers, Abhishek Shrestha, Sergio Duarte, Ali Zarrinpar, Siobhan Malany, and Satyamaheshwar Peddibhotla. 2025. "Targeting CXCR6 Disrupts β-Catenin Signaling and Enhances Sorafenib Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233818

APA StyleReeves, M., Chambers, A., Shrestha, A., Duarte, S., Zarrinpar, A., Malany, S., & Peddibhotla, S. (2025). Targeting CXCR6 Disrupts β-Catenin Signaling and Enhances Sorafenib Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers, 17(23), 3818. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233818