A High-Accuracy Solid/Liquid Composite Packaging Method for Implantable Pressure Sensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

2.1. Packaging Preparation

2.2. Packaging Structure

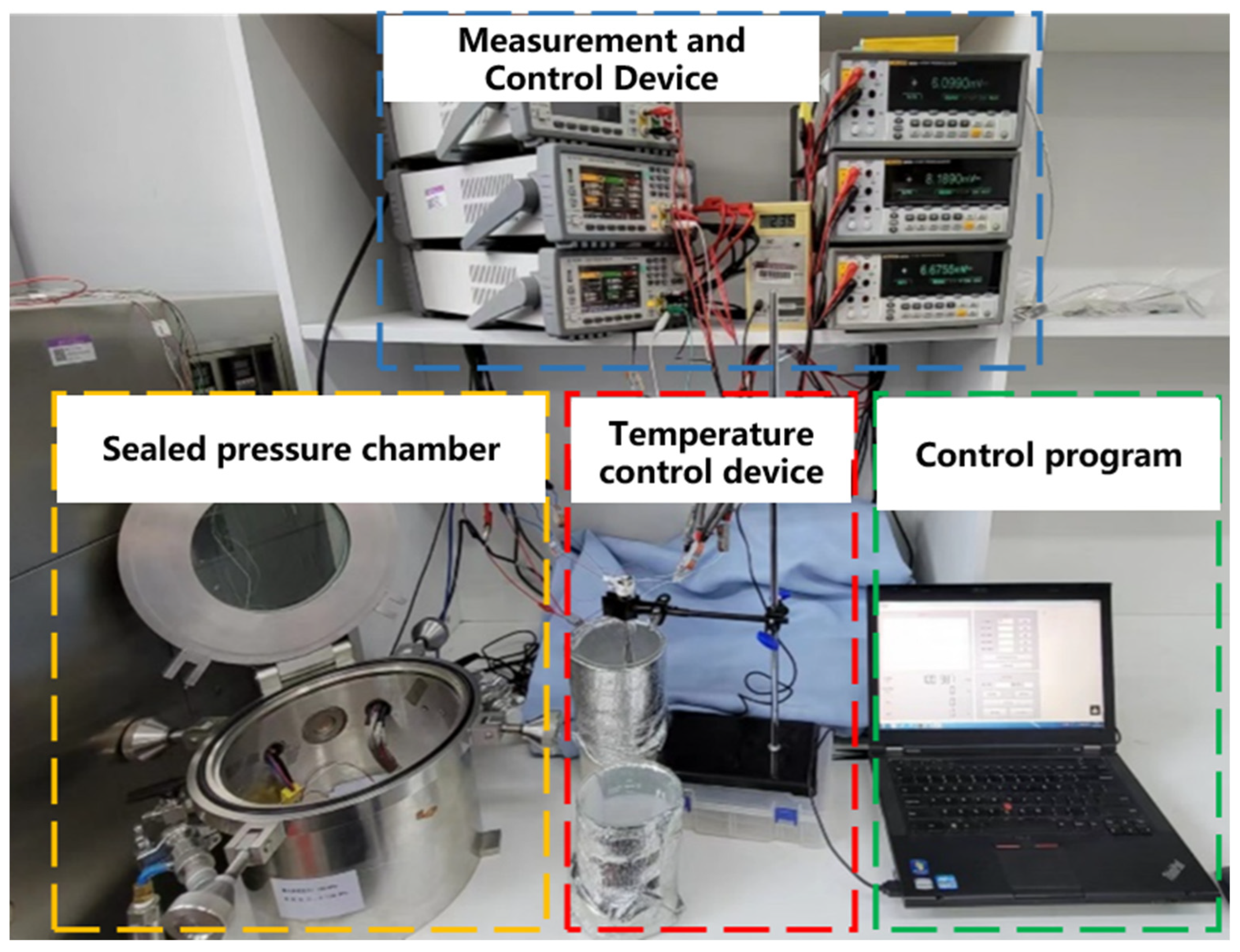

2.3. Testing Methodologies and Platform

3. Results and Discussion

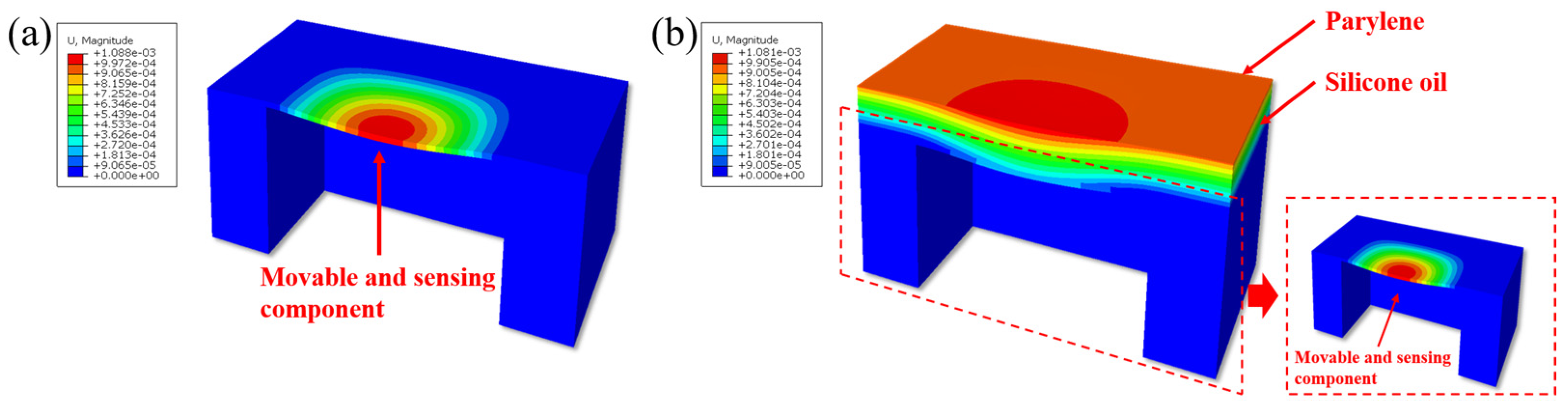

3.1. Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

3.2. Accuracy Testing

3.3. Stability Testing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, P.S.; Ma, Z.; Ma, J.; Yang, L.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, F.; Wang, X. Recent Progress of Miniature MEMS Pressure Sensors. Micromachines 2020, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, R.L.; Nixon, J. Measuring Mental Workload using Physiological Measures: A systematic review. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 74, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S.; Mohan, S.; Kuppusamy, R.; Suyambulingam, I.; Baby, B.; Ramesh, R.; Han, S.S. Advances in Bio-Microelectromechanical System-Based Sensors for Next-Generation Healthcare Applications. Acs Omega 2025, 10, 34088–34105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergele, L.; Mallard, J.; Magand, C.; Suyambulingam, I.; Baby, B.; Ramesh, R.; Han, S.S. In vivo Testing of the Pressio Intracranial Pressure Monitor. Neurocrit. Care 2025, 44, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolfaghari, P.; Yalcinkaya, A.D.; Ferhanoglu, O. MEMS Sensor-Glasses Pair for Real-Time Monitoring of Intraocular Pressure. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2023, 35, 887–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatiparthi, V.R.; Rao, M.D.V.; Kumar, S.; Hindumathi. Detection and analysis of coagulation effect in vein using MEMS laminar flow for the early heart stroke diagnosis. Aims Bioeng. 2023, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Z.; Cauwe, M.; Yang, Y.; Schaubroeck, D.; Mader, L.; de Beeck, M.O. Ultra-Long-Term Reliable Encapsulation Using an Atomic Layer Deposited HfO2/Al2O3/HfO2 Triple-Interlayer for Biomedical Implants. Coatings 2019, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.W.; Wei, L.; Zhang, M.L.; Yang, F.; Wang, X. Hermetic and Bioresorbable Packaging Materials for MEMS Implantable Pressure Sensors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 23633–23648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Kim, Y.S.; Tillman, B.W.; Yeo, W.-H.; Chun, Y. Advances in Materials for Recent Low-Profile Implantable Bioelectronics. Materials 2018, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, A.J.T.; Mishra, A.; Park, I.; Kim, Y.-J.; Park, W.-T.; Yoon, Y.-J. Polymeric Biomaterials for Medical Implants and Devices. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.; Stam, F.; O’Brien, J.; Kailas, L.; Mathewson, A.; O’Murchu, C. Crystallinity and mechanical effects from annealing Parylene thin films. Thin Solid Film. 2016, 603, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortigoza-Diaz, J.; Scholten, K.; Meng, E. Characterization and Modification of Adhesion in Dry and Wet Environments in Thin-Film Parylene Systems. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2018, 27, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.L.; Lee, Y.E.; Kim, D.H.; Ye, H.; Kwon, H.-J.; Kim, S.H. Research on Parylene-C application to wearable organic electronics: In the respect of substrate type. Macromol. Res. 2025, 33, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selbmann, F.; Kühn, M.; Roscher, F.; Wiemer, M.; Kuhn, H.; Joseph, Y. Parylene as a novel packaging material for adhesive bonding, flexible electronics and wafer level packaging. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE Electronics System-Integration Technology Conference (ESTC), Berlin, Germany, 11–13 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Selbmann, F.; Scherf, C.; Langenickel, J.; Roscher, F.; Wiemer, M.; Kuhn, H.; Joseph, Y. Impact of Non-Accelerated Aging on the Properties of Parylene C. Polymers 2022, 14, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, T.A.; Yao, T.J.; He, Q.; Shih, C.-Y.; Tai, Y.-C. Residual stress in thin-film Parylene-C. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS 2002), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 20–24 January 2002; pp. 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Xing, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.A. Comprehensive Review on Water Diffusion in Polymers Focusing on the Polymer-Metal Interface Combination. Polymers 2020, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariello, M.; Kim, K.; Wu, K.L.; Lacour, S.P.; Leterrier, Y. Recent Advances in Encapsulation of Flexible Bioelectronic Implants: Materials, Technologies, and Characterization Methods. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2201129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golda-Cepa, M.; Engvall, K.; Hakkarainen, M.; Kotarba, A. Recent progress on parylene C polymer for biomedical applications: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 140, 105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.L.; Qiang, W.J.; Guo, X.Q.; Fan, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X. Defect Filling Method of Sensor Encapsulation Based on Micro-Nano Composite Structure with Parylene Coating. Sensors 2021, 21, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, S.K.; Cui, L. Effect of Parylene Coating on the Performance of Implantable Pressure Sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 24593–24599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzar, G.; Freas, M.; Abel, P.; Fleischman, A.; Roy, S.; Zorman, C.; Moran, J.M.; Melzak, J. Evaluation of MEMS materials of construction for implantable medical devices. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 2737–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.C.; Xu, Q.; Dou, S.; Zhang, P.; Jin, Y.; Kang, J.; Wang, W. Copolymerization of Parylene C and Parylene F to Enhance Adhesion and Thermal Stability without Coating Performance Degradation. Polymers 2023, 15, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.H.; Chang, W.D. Blood Pressure Monitoring Based on Flexible Encapsulated Sensors. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwalder, S.; Hersberger, M.; Rebl, H.; Seemann, S.; Kram, W.; Hogg, A.; Tvedt, L.G.W.; Clausen, I.; Burger, J. An Evaluation of Parylene Thin Films to Prevent Encrustation for a Urinary Bladder Pressure MEMS Sensor System. Polymers 2023, 15, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, S.; Park, H.; Choi, W.; Kim, O.; Kim, J. Analysis of Thin Film Parylene-Metal-Parylene Device Based on Mechanical Tensile Strength Measurement. In Proceedings of the 21st Symposium on Design, Test, Integration and Packaging of MEMS and MOEMS (DTIP), Paris, France, 12–15 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, E.M.; Charlson, E.J.; Sabeti, R. Temperature selective deposition of Parylene-C. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1992, 39, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Meng, E. Micromachining of Parylene C for bioMEMS. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2016, 27, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, P.; Bartels, K.; Agrawal, C.M.; Bailey, S. A thin-film pressure transducer for implantable and intravascular blood pressure sensing. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2016, 248, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, Q.; Yang, X. A High-Accuracy Solid/Liquid Composite Packaging Method for Implantable Pressure Sensors. Micromachines 2026, 17, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020162

Wang B, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Li Z, Jiang S, Wang F, Liu Q, Yang X. A High-Accuracy Solid/Liquid Composite Packaging Method for Implantable Pressure Sensors. Micromachines. 2026; 17(2):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020162

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bo, Yubiao Zhang, Yuning Huang, Zhonghua Li, Senran Jiang, Fuji Wang, Qiang Liu, and Xing Yang. 2026. "A High-Accuracy Solid/Liquid Composite Packaging Method for Implantable Pressure Sensors" Micromachines 17, no. 2: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020162

APA StyleWang, B., Zhang, Y., Huang, Y., Li, Z., Jiang, S., Wang, F., Liu, Q., & Yang, X. (2026). A High-Accuracy Solid/Liquid Composite Packaging Method for Implantable Pressure Sensors. Micromachines, 17(2), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020162