Design, Modeling, and Experiment Characterization of a Piezoelectric Inchworm Actuator for Long-Stroke and High-Resolution Positioning

Abstract

1. Introduction

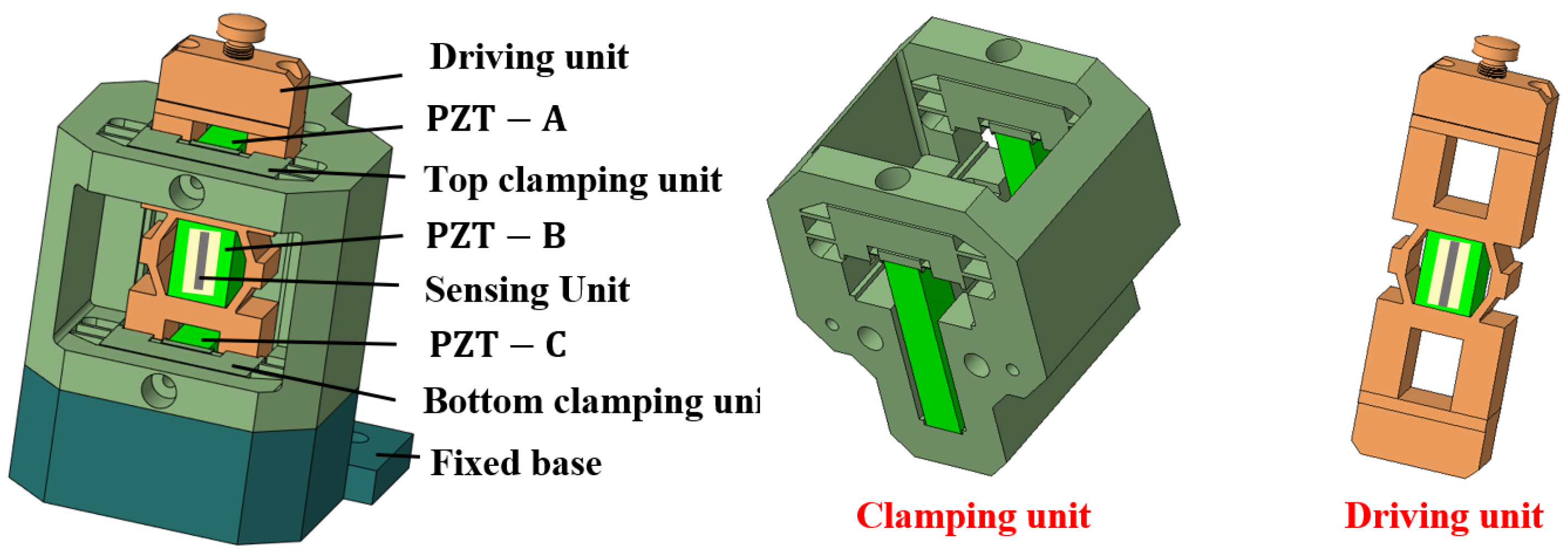

2. Structural Design and Operating Principle

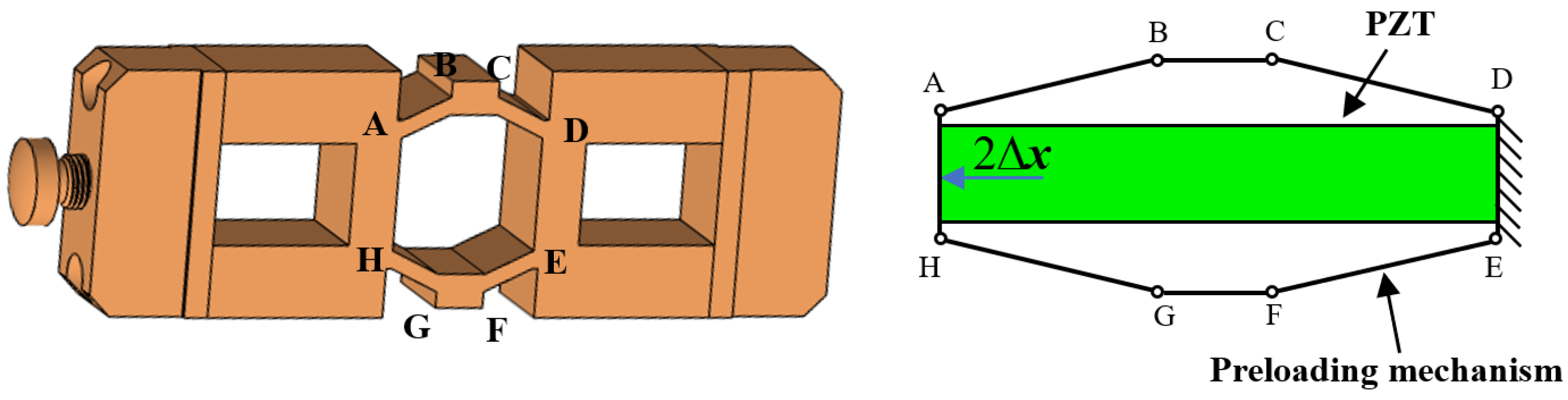

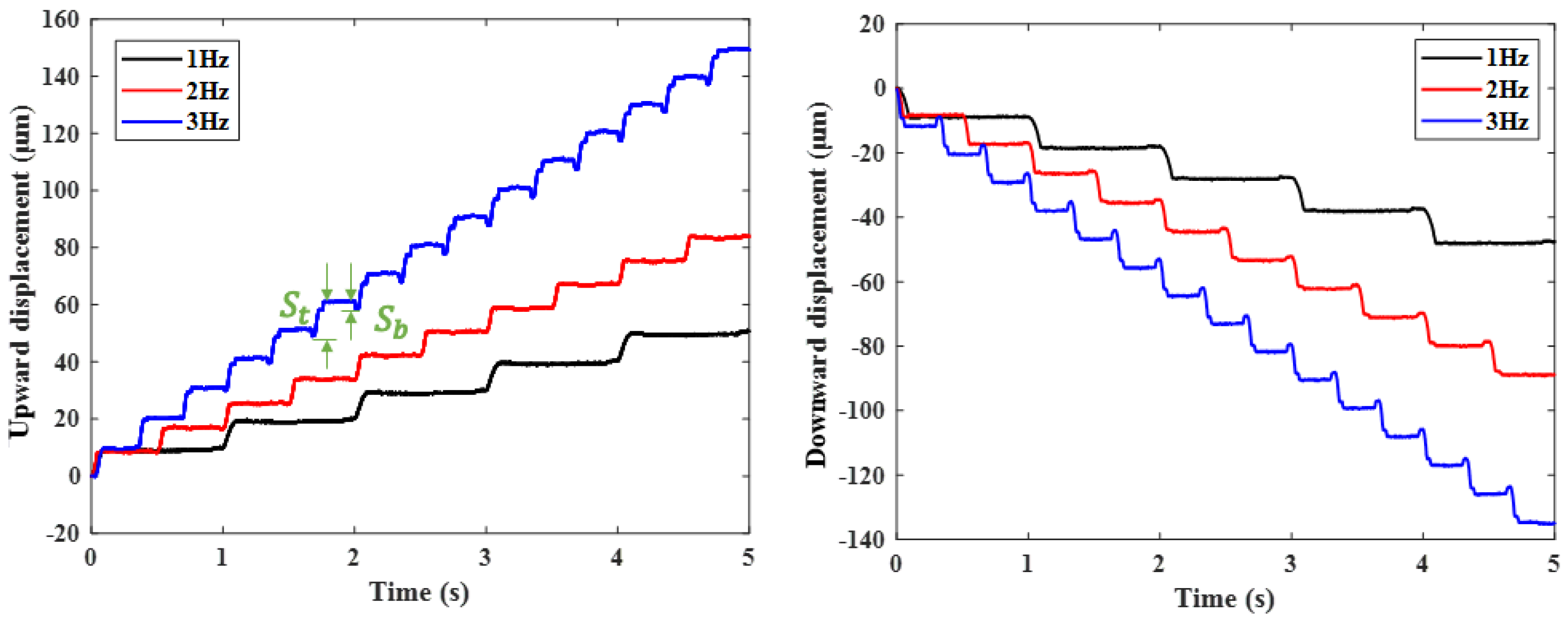

2.1. Mechanical Structural Design of the Actuator

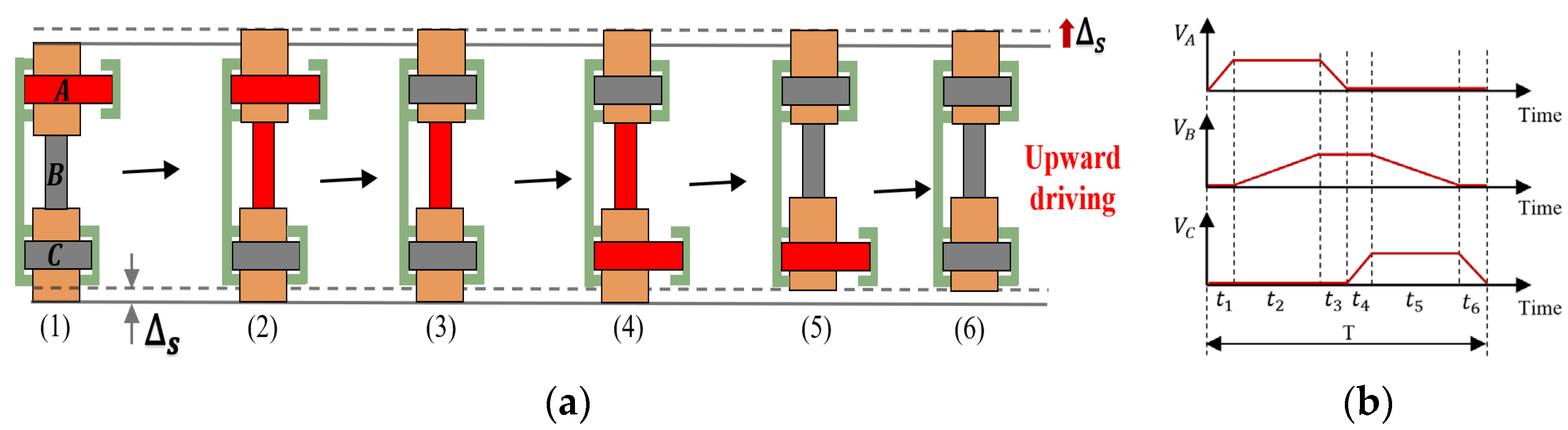

2.2. Operating Principle of the Actuator

- (1)

- PZT-A energized and extended, the top clamping unit leaves the driving unit.

- (2)

- PZT-B energized and extended, the driving unit produces an upward displacement of magnitude ∆s.

- (3)

- PZT-A deenergized, the actuator contracts back to the length it had before the high voltage was applied under its own elastic force.

- (4)

- PZT-C energized and extended, the bottom clamping unit leaves the driving unit.

- (5)

- PZT-B deenergized, the actuator contracts back to the length it had before the high voltage was applied.

- (6)

- PZT-C deenergized, the actuator contracts back to the length it had before the high voltage was applied. The actuator completes a single feed motion, outputting displacement ∆s.

- (1)

- PZT-A extended, the top clamping unit leaves the driving unit.

- (2)

- PZT-B generates controlled micro-displacement when driven by a voltage-modulated sinusoidal waveform, enabling precise motion regulation through electrical input adjustment.

3. Structural Modeling and Analysis

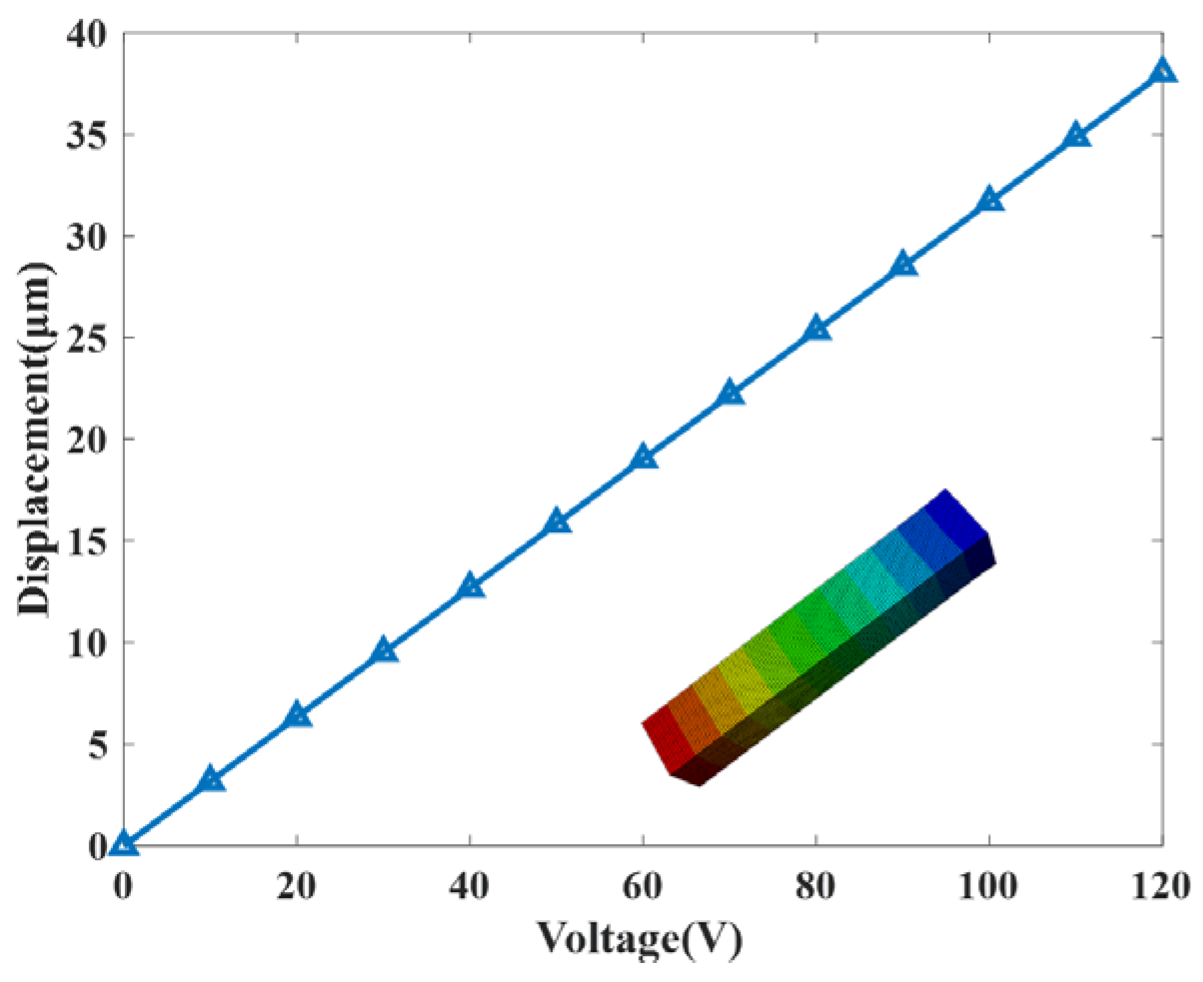

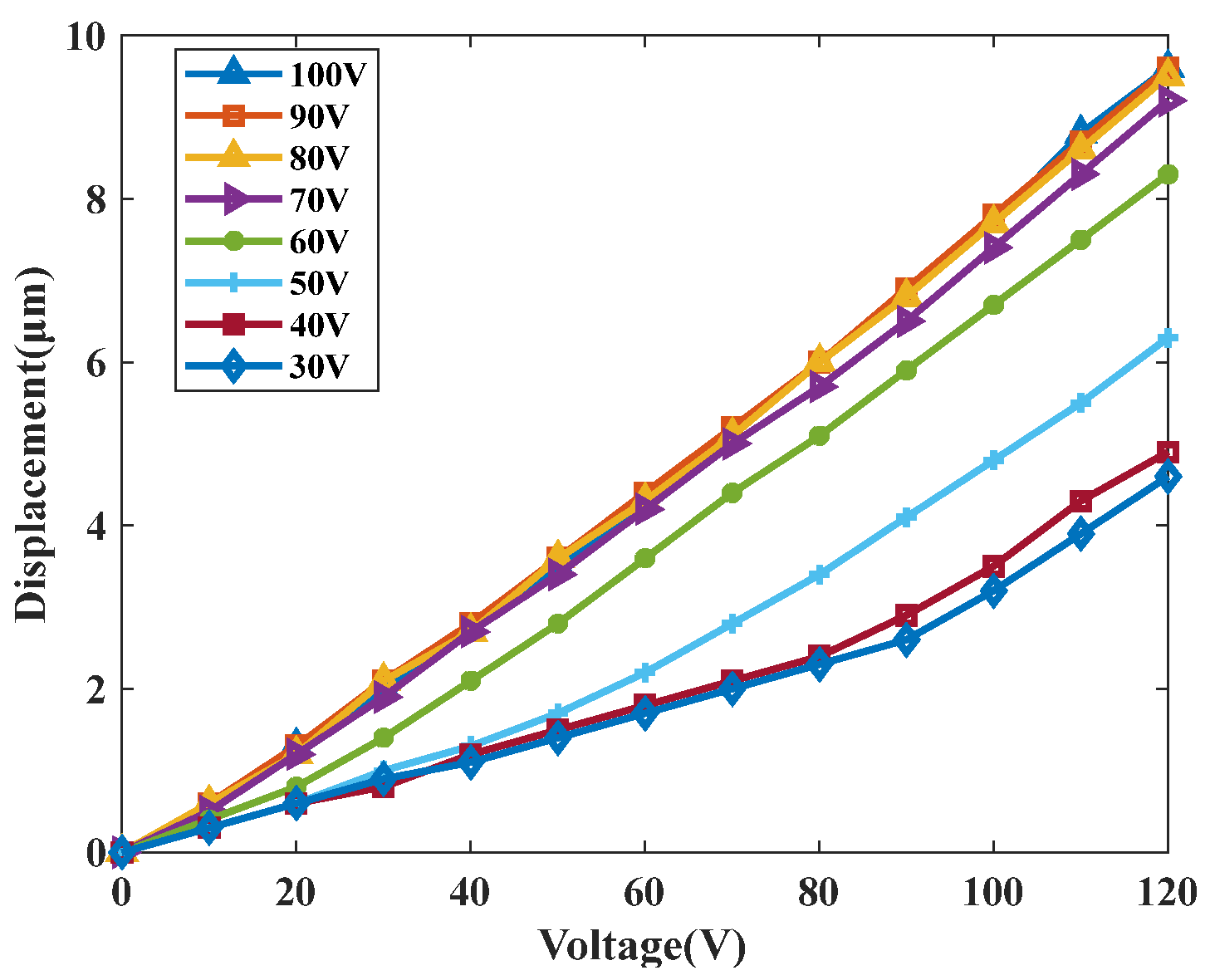

3.1. FEM of the PZT Stack

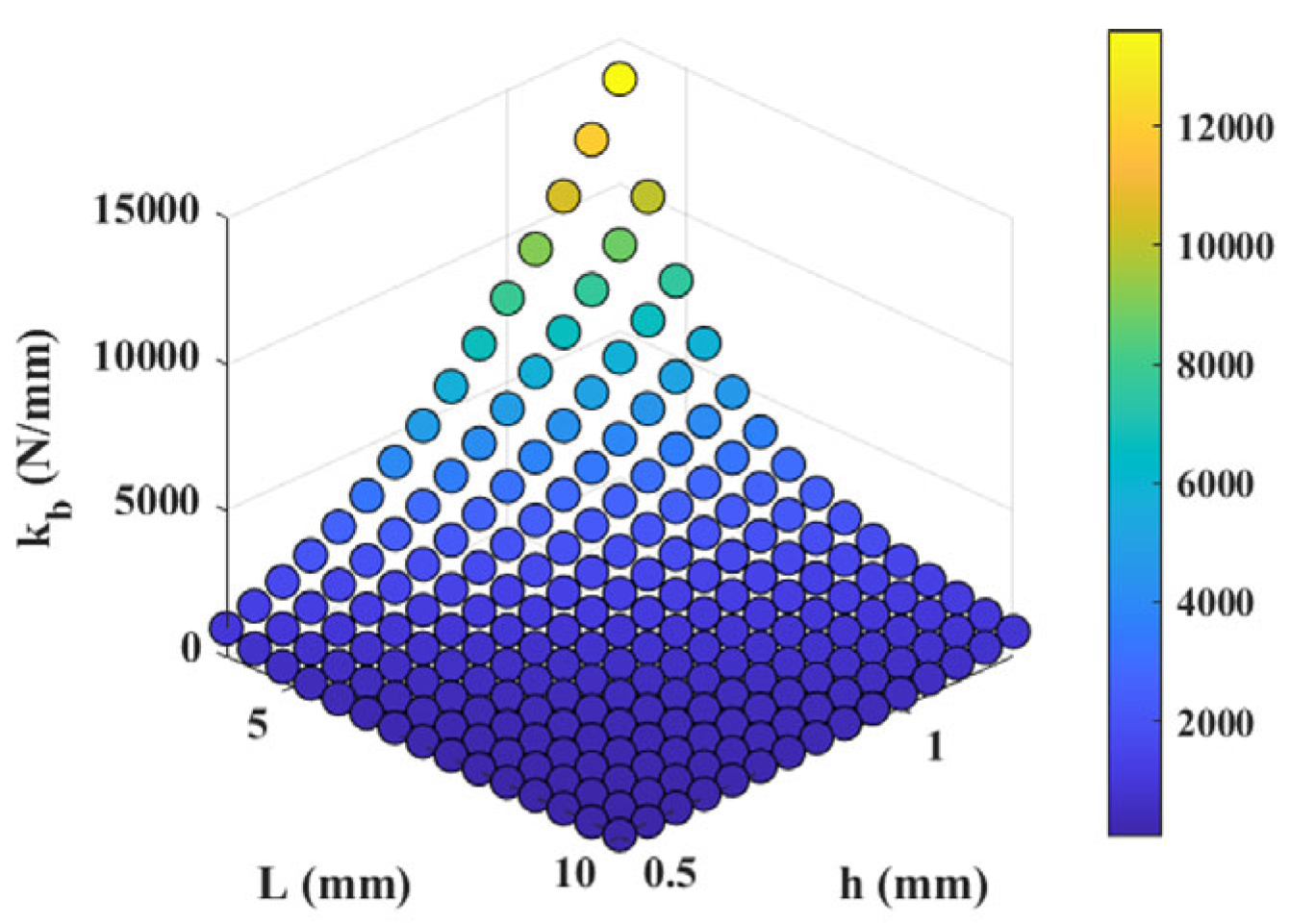

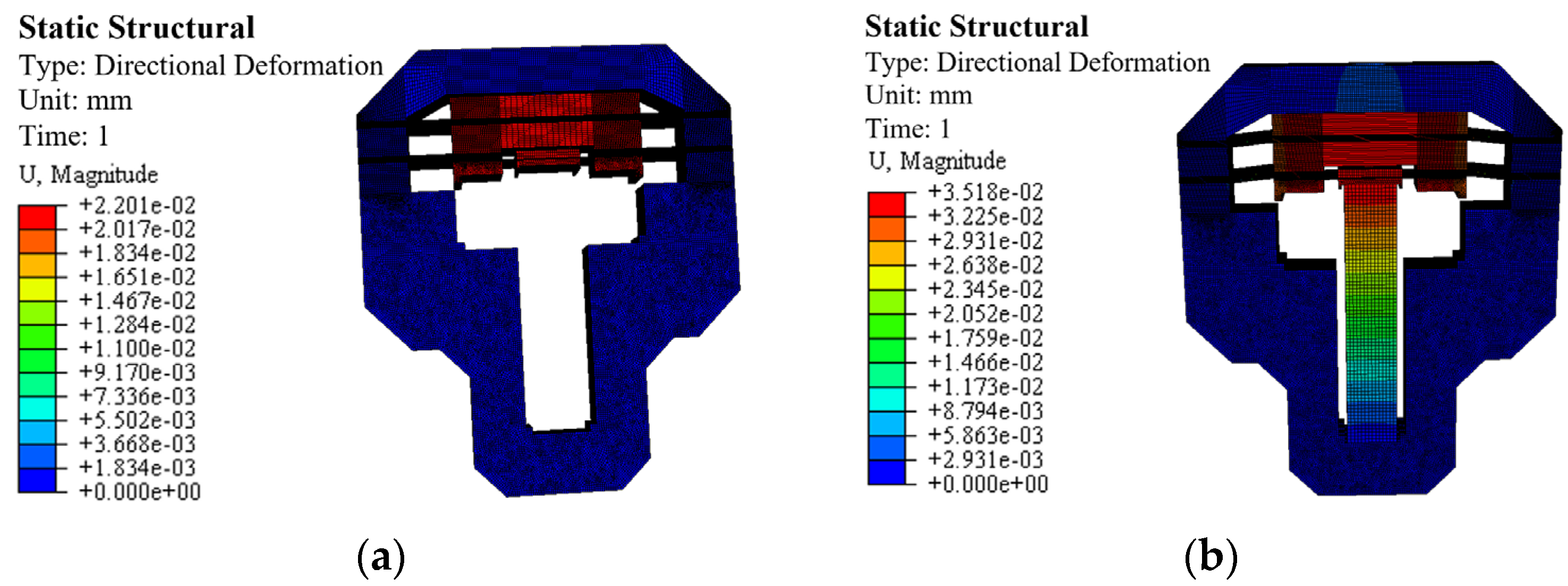

3.2. Modeling and Analysis of Clamping Units

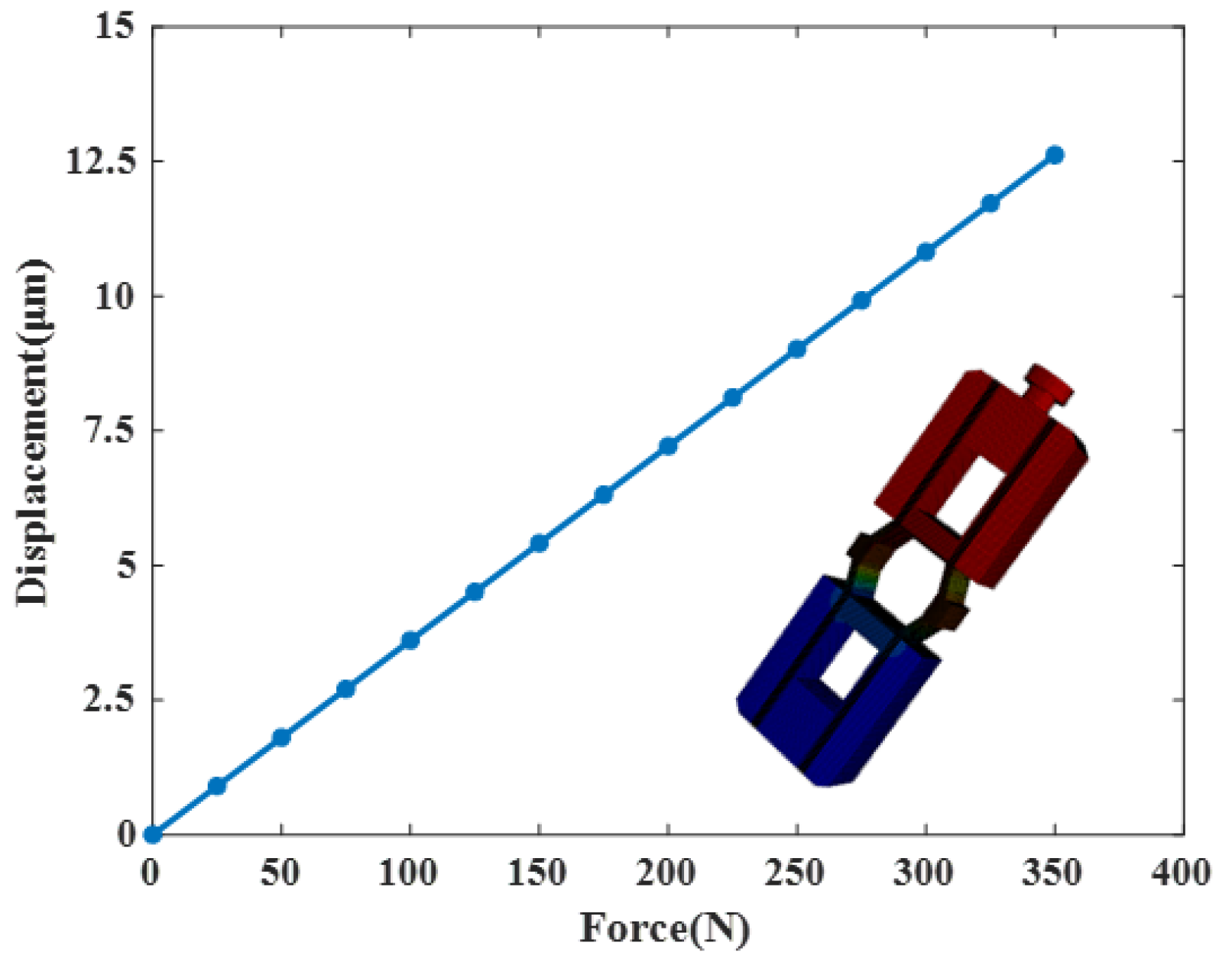

3.3. Modeling and Analysis of Driving Unit

3.4. Friction Calculation and Dynamic Model of the Actuator

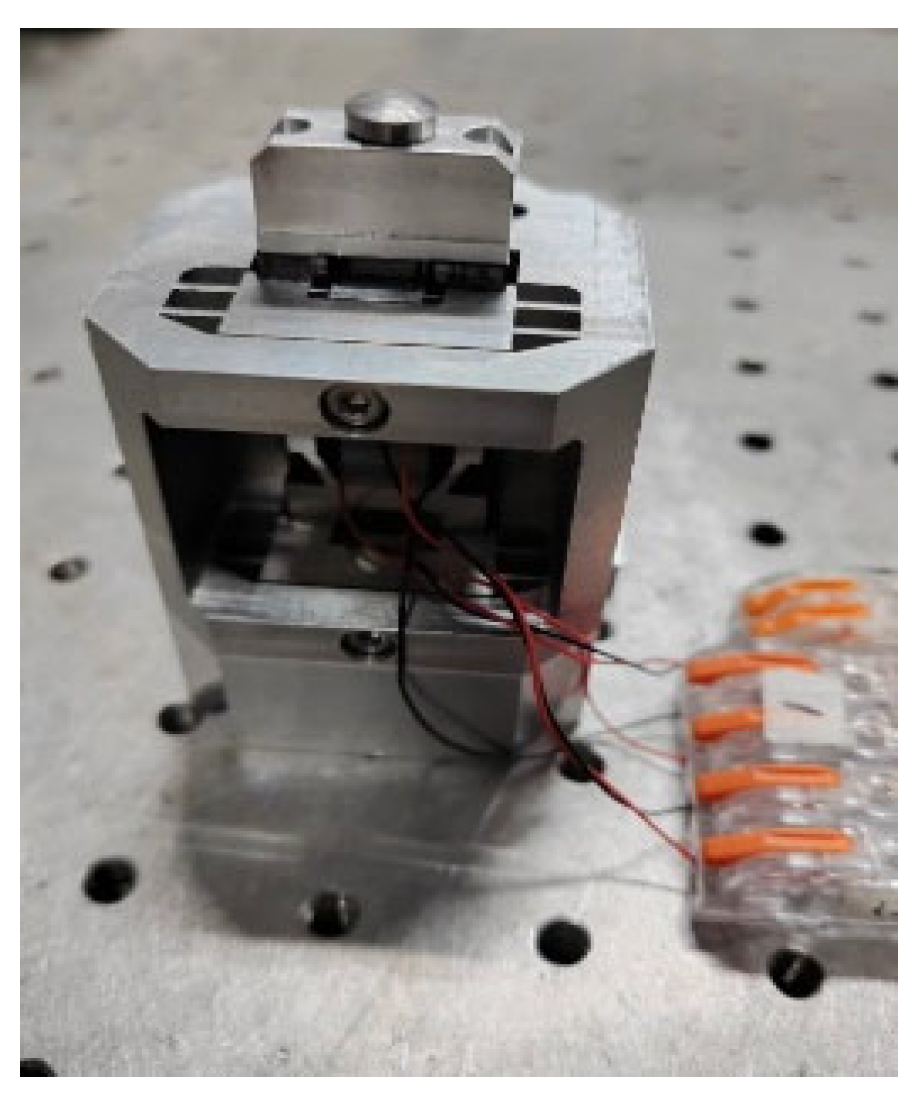

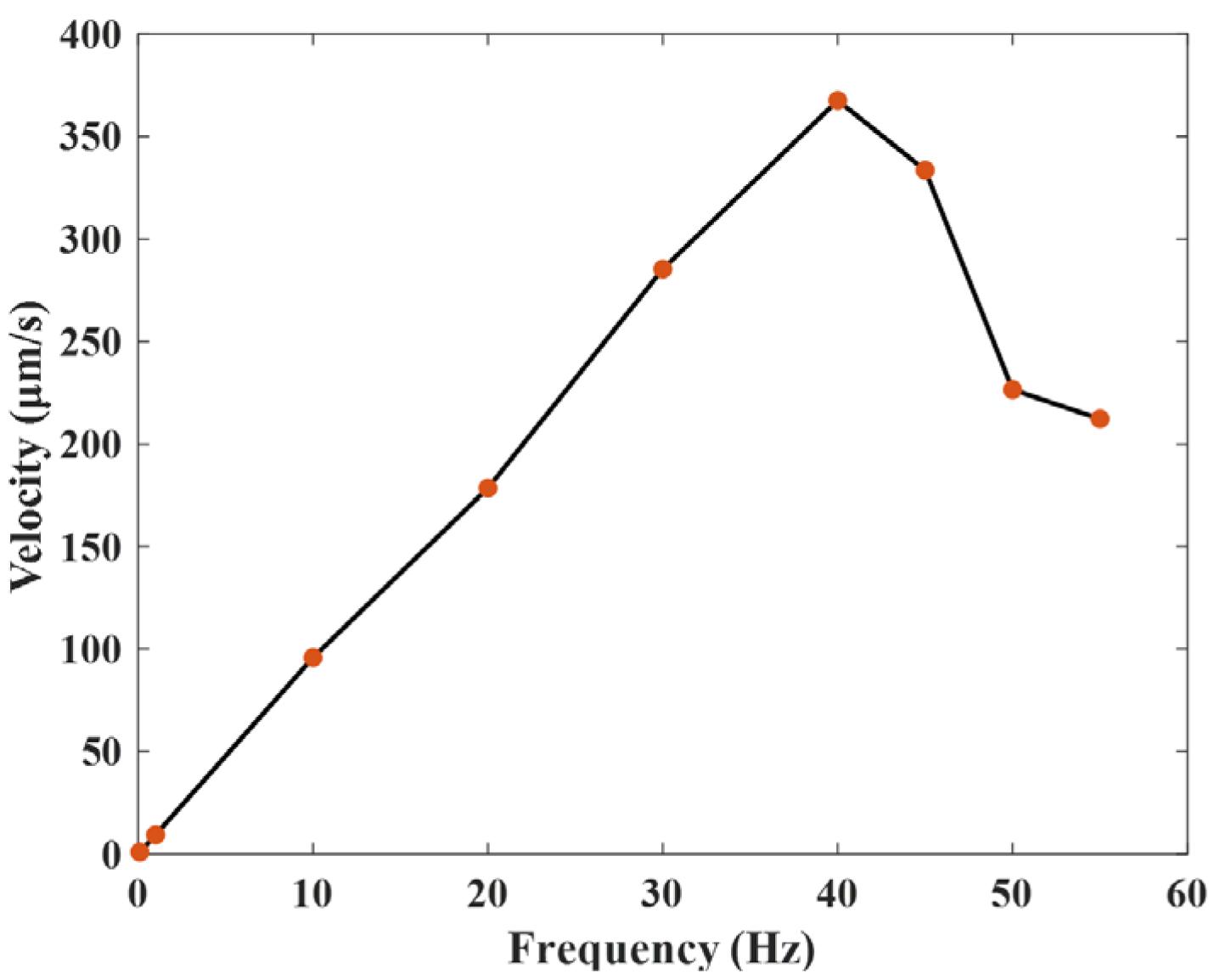

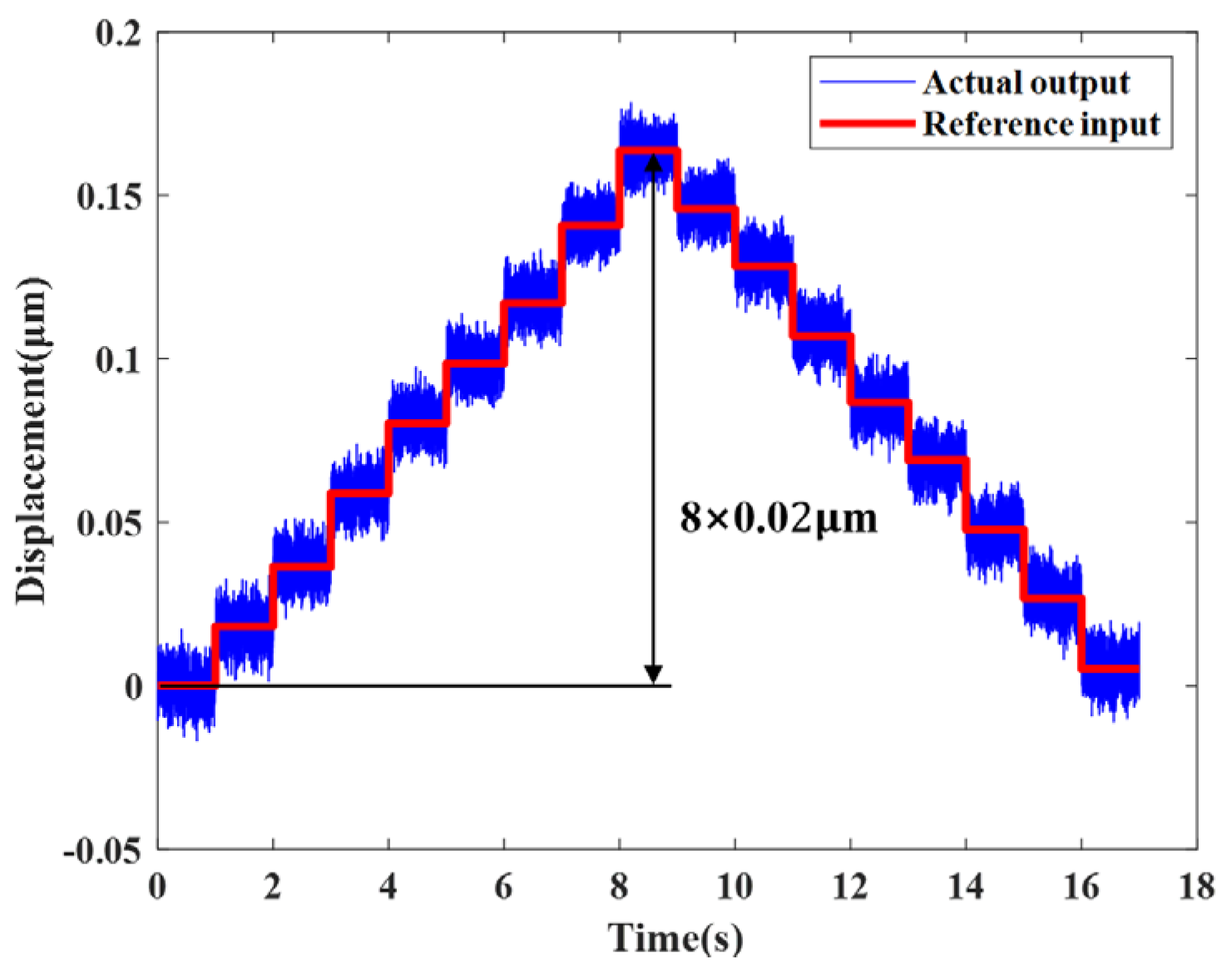

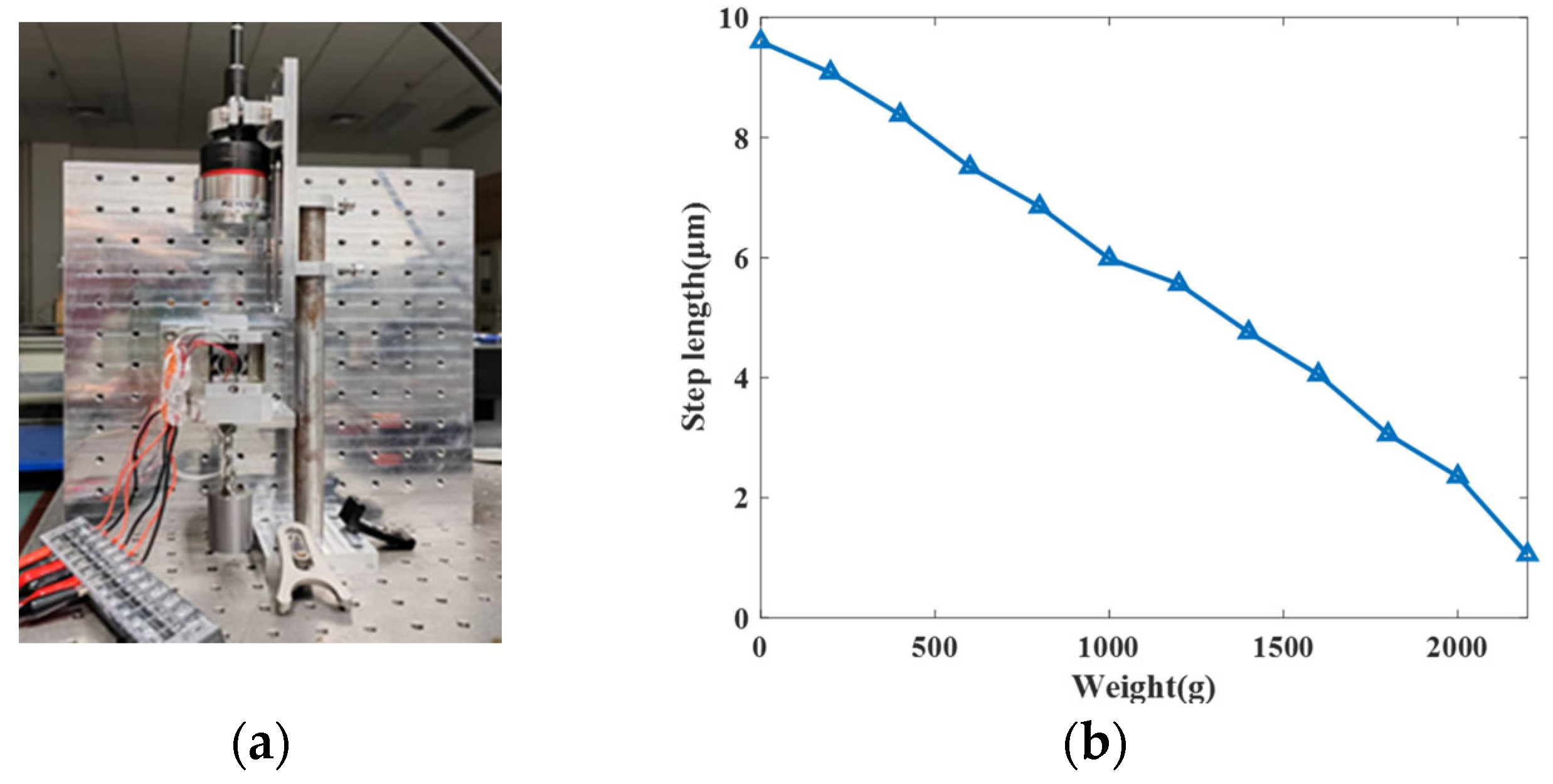

4. Characteristic Experiments of the Actuator

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.; Xu, Q. Design and precision position/force control of a piezo-driven microinjection system. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2017, 22, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.; Salim, D.; Chandran, D.; Aljibori, H.S.; Kherbeet, A.S. Review of nano piezoelectric devices in biomedicine applications. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2018, 29, 2105–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xu, Q. Design and testing of a new force-sensing cell microinjector based on small-stiffness compliant mechanism. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 26, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Li, K. A 2-DOF needle insertion device using inertial piezoelectric actuator. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 3918–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breguet, J.-M.; Driesen, W.; Kaegi, F.; Cimprich, T. Applications of piezo-actuated micro-robots in micro-biology and material science. In Proceedings of the 2007 International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Harbin, China, 5–8 August 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Qu, H.; Cui, T.; Fu, L.; Huang, H.; Ren, L.; Fan, Z. A piezoelectric-driven rotary actuator by means of inchworm motion. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2013, 194, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Piezoelectric hybrid actuation mode to improve speeds in cross-scale micromanipulations. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 240, 107943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Gao, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Chu, Z.; Dong, S. A ring-shaped, linear piezoelectric ultrasonic motor operating in E01 mode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 152902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delibas, B.; Koc, B. Single crystal piezoelectric motor operating with both inertia and ultrasonic resonance drives. Ultrasonics 2023, 136, 107140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, X.-H.; Nguyen, D.-T. A Novel Dynamic Modeling Framework for Flexure Mechanism-Based Piezoelectric Stick–Slip Actuators with Integrated Design Parameter Analysis. Machines 2025, 13, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tan, L.; Yu, Q.; Wu, H.; Meng, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, H.; Zhu, L. High-Throughput Uniform Scanning of Stick-Slip Actuators With Optimal Smooth Trajectory. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 13939–13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X. Design and experimental evaluation of an inchworm motor driven by bender-type piezoelectric actuators. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi, H.; Sawada, H. An Inchworm Robot with Self-Healing Ability Using SMA Actuators. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2023, 35, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, P. An Orthogonal and Stereoscopic Amplifying Mechanism with Nonparasitic Displacement for Parallel Piezoelectric Inchworm Actuators. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), Genova, Italy, 2–4 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Rong, W.; Wang, L.; Pei, Z.; Sun, L. A novel inchworm type piezoelectric rotary actuator with large output torque: Design, analysis and experimental performance. Precis. Eng. 2018, 51, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wen, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, Y.; Li, J. A self-adapting linear inchworm piezoelectric actuator based on a permanent magnets clamping structure. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 132, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yan, P.; Liu, P. A high-speed inchworm piezoelectric actuator with multi-layer flexible clamping: Design, modeling, and experiments. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 218, 111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Gao, X.; Xie, H.; Liu, Y. Development and experiment evaluation of a compact inchworm piezoelectric actuator using three-jaw type clamping mechanism. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 045020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J. A walker-pusher inchworm actuator driven by two piezoelectric stacks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 169, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; Deng, S.; Li, Y.; Li, H. A novel inchworm piezoelectric actuator with rhombic amplification mechanism. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 360, 114515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Gao, X.; Cheng, J. A compact inchworm piezoelectric actuator with high speed: Design, modeling, and experimental evaluation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 184, 109704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Xu, M.; Zhang, S.; Xie, S. Stroke maximizing and high efficient hysteresis hybrid modeling for a rhombic piezoelectric actuator. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 75, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Song, S.; Shao, Y.; Xu, M. Long-range piezoelectric actuator with large load capacity using inchworm and stick-slip driving principles. Precis. Eng. 2022, 75, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.-W.; Yao, S.-M.; Wang, L.-Q.; Zhong, Z. Analysis of the displacement amplification ratio of bridge-type flexure hinge. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2006, 132, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Huang, H.; Dong, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhao, H. On the suppression of the backward motion of a piezo-driven precision positioning platform designed by the parasitic motion principle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 3870–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, P. A novel bidirectional complementary-type inchworm actuator with parasitic motion based clamping. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 134, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Type | P-887.91 |

| Size of piezo stack | 7 mm × 7 mm × 36 mm |

| Operating voltage | 0–120 V |

| Maximum output | 1850 N |

| Maximum displacement | 38 ± 20% μm |

| Stiffness | 50 N/μm |

| Resonant frequency | 40 kHz |

| Piezoelectric constant | 0.108 μm/V |

| Type | P-888.31 |

| Size of piezo stack | 10 mm × 10 mm × 13.5 mm |

| Operating voltage | 0–120 V |

| Maximum output | 3500 N |

| Maximum displacement | 13 ± 20% μm |

| Stiffness | 267 N/μm |

| Resonant frequency | 90 kHz |

| Reference | Speed (μm/s) | Thrust Force (N) | Step Resolution (μm) | Guiding Structure? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al. [25] | 180 | 7.6 | 5.50 | No |

| Deng et al. [18] | 155.5 | 12.3 | 0.37/0.39 | No |

| Wang et al. [26] | 216.3 | 1.2 | N/A | Yes |

| Ma et al. [19] | 471.01 | 5.88 | N/A | Yes |

| Shao et al. [23] | 43 | 546 | 0.08 | No |

| This study | 367 | 22 | 0.02 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Jing, Z.; Wang, J.; Meng, F.; Yang, X.; Qin, T.; Yan, W.; Qi, B. Design, Modeling, and Experiment Characterization of a Piezoelectric Inchworm Actuator for Long-Stroke and High-Resolution Positioning. Micromachines 2026, 17, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020161

Li X, Jing Z, Wang J, Meng F, Yang X, Qin T, Yan W, Qi B. Design, Modeling, and Experiment Characterization of a Piezoelectric Inchworm Actuator for Long-Stroke and High-Resolution Positioning. Micromachines. 2026; 17(2):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020161

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xin, Zijian Jing, Jin Wang, Fanhui Meng, Xiaoli Yang, Tao Qin, Wei Yan, and Bo Qi. 2026. "Design, Modeling, and Experiment Characterization of a Piezoelectric Inchworm Actuator for Long-Stroke and High-Resolution Positioning" Micromachines 17, no. 2: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020161

APA StyleLi, X., Jing, Z., Wang, J., Meng, F., Yang, X., Qin, T., Yan, W., & Qi, B. (2026). Design, Modeling, and Experiment Characterization of a Piezoelectric Inchworm Actuator for Long-Stroke and High-Resolution Positioning. Micromachines, 17(2), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020161