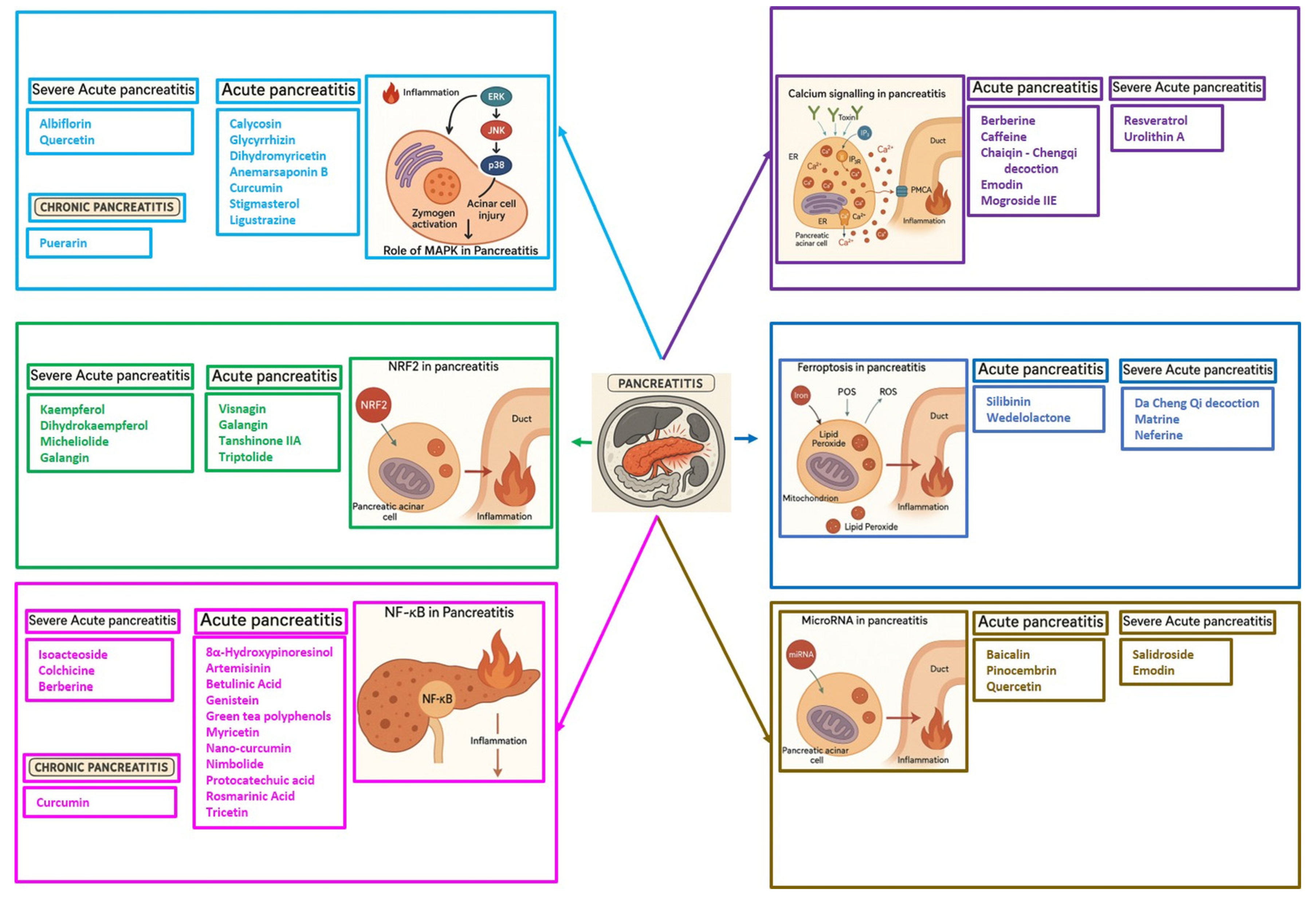

Therapeutic Potentials of Phytochemicals in Pancreatitis: Targeting Calcium Signaling, Ferroptosis, microRNAs, and Inflammation with Drug-Likeness Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. In Vivo Model of Pancreatitis

3.1. In Vivo Animal Models of Acute Pancreatitis

3.1.1. Caerulein-Induced Acute Pancreatitis

3.1.2. Alcohol-Induced AP (FAEE Model)

3.1.3. Basic Amino Acids

3.1.4. Pancreatic Duct Ligation

3.1.5. Bile Acid Salts

3.2. In Vivo Animal Models of Severe Acute Pancreatitis

3.2.1. Two-Hit L-Arginine

3.2.2. Sodium Taurocholate-Induced Severe Acute Pancreatitis

3.3. Animal Models of Chronic Pancreatitis

3.3.1. Pancreatic Duct Ligation

3.3.2. Repeated Cerulein Injection

3.3.3. Alcohol-Induced Chronic Pancreatitis Model

3.3.4. L-Arginine-Induced Chronic Pancreatitis

4. Pancreatitis Pathophysiology

4.1. Calcium Signaling Dysregulation

4.1.1. Physiological Calcium Signaling in Pancreatic Acinar Cells

4.1.2. Calcium Signaling Dysregulation in Pancreatitis

4.2. Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis Role in Pancreatitis

4.3. Nrf2 Role in Pancreatitis

4.4. NF-κB in Pancreatitis

4.5. p38 MAPK in Pancreatitis

4.6. MiRNA Role in Pancreatitis

| MicroRNA | MicroRNAs Status of the Disease | Target Protein | Studied Model | Function of MicroRNAs | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-22 | Upregulated | ↓ ErbB3 | In vitro and in vivo rat model | Promotes apoptosis of PACs | [118] |

| miR-135a | Upregulated | ↓ Ptk2 | In vitro and in vivo rat model | Promotes apoptosis of PACs | [118] |

| miR-141 | Given to the mice | ↓ HMGB1 | In vivo mouse model | Block the process of autophagosome formation. | [119] |

| miR-19b | Upregulated | NA | In vitro and in vivo rat model | promotes the necrosis of PACs | [137] |

| miR-21 | upregulated | ↓ PTEN/FASL | In vivo mouse model | Enhances RIP1/3-mediated necroptosis | [120] |

| miR-148a-3p | upregulated | ↓ PTEN | In vitro and in vivo mouse model | Induces necrosis and inflammatory infiltration | [123] |

| miR-216a | upregulated | ↓ Smad7 | In vitro and in vivo mouse model | Activation of TGF-β signaling | [122] |

| miR-26a | Downregulated | ↓ Trpc3 and Trpc6 | In vitro, in vivo mouse model, and human data | increases SOCE channel expression and [Ca2+]i overload, | [125] |

| miR-29a-3p | Downregulated | ↓ HMGB1 | In vitro and in vivo rat model | Inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inflammation during SAP. | [128] |

| rno-miR-29a-3p | Downregulated | NA | In vivo rat model | Possesses anti-inflammatory properties and mitigates SAP-ALI. | [132] |

| miR-141 | Given to the rats | ↓ PI3K/Mtor | In vivo rat model | inhibits autophagy, and ameliorates the development of SAP | [133] |

| miR-155 | upregulated | ↓ RhoA | In vivo mouse model | Inhibits the synthesis of ZO-1 and E-cadherin and disrupts the intestinal epithelial barrier in experimental SAP | [129] |

| miR-15b and miR-16 | Downregulated | ↓ Bcl-2 | In vitro model | Induce apoptosis of rat PSCs | [135] |

| miR-21 | Upregulated | ↑ CCN2 | In vitro model | Amplifies fibrotic signaling in the pancreas during CP | [136] |

5. Phytochemicals for Acute and Severe Acute Pancreatitis

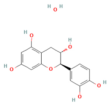

5.1. Phytochemicals Target Calcium Signaling

Phytochemicals Target Calcium Signaling in Other Diseases

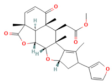

5.2. Phytochemicals Target Ferroptosis

5.3. Phytochemicals Target NF-κB

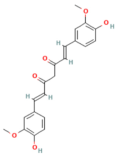

5.4. Phytochemicals Targeted the p38-MAPK Pathway

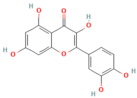

5.5. Phytochemicals Target the Nrf2 Pathway

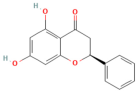

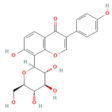

5.6. Phytochemicals Target MicroRNAs

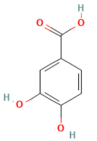

5.7. Phytochemicals Target Other Pathways

5.7.1. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

5.7.2. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

| Phytochemical Name | Class/Plant | Therapeutic Dose/Route of Administration | Main Target Pathway/Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium signaling | ||||

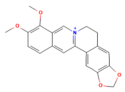

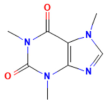

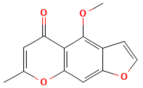

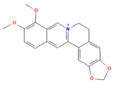

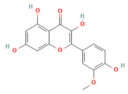

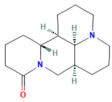

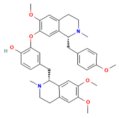

| Berberine | Isoquinoline alkaloid Coptis chinensis, Phellodendron chinensis, or three needles | 10 µM in vitro | ↓ M3 muscarinic receptor, Ach-induced Ca2+ oscillations | [141] |

| Caffeine | Methylxanthine alkaloid Coffea arabica Camellia sinensis | 1, 5, 10, or 25 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ IP3R activity, Cytosolic Ca2+ overload | [140] |

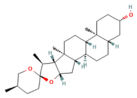

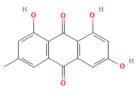

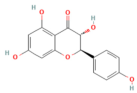

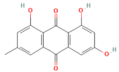

| Emodin | Anthraquinone rhubarb | 10 and 20 μM In vitro | ↓ Ca2+ concentration, Bip, PERK, ATF6, IRE1 | [177] |

| Chaiqinchengqi decoction | Genus: Artemisiae Scopariae, Gardenia, and Rhubarb | 10 mL/kg Oral | ↑ SERCA2, ER Ca2+ reuptake, ↓ Cytosolic Ca2+ overload, acinar cell necrosis | [178] |

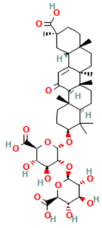

| Mogroside IIE | Triterpenoid saponin Unripe Siraitia grosvenorii | 10 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ IL-9, IL-9R signaling, Cytosolic Ca2+ overload, LC3-II, Cathepsin B activity, ↑ p62 | [179] |

| Ferroptosis pathway | ||||

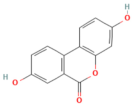

| Silibinin | Flavonoid milk thistle (Silybum marianum) | 100 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ FAT10, NCOA4, TFRC, ACSL4, ↓ Free Fe2+ ↑ FTH1 | [70] |

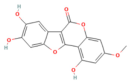

| Wedelolactone | Coumarin-like compound Eclipta prostrata | 25 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg i.p. | ↑ GPX4 → ↓ Ferroptosis | [151] |

| NF-κB pathway | ||||

| 8α-Hydroxypinoresinol | Lignan Nardostachys jatamansi | 0.5, 5 or 10 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ IκBαdegradation, NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | [50] |

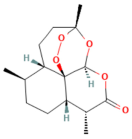

| Artemisinin | Sesquiterpene lactone Artemisia annua | 50 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ NF-κB, MIP-1α, IL-1β ↑ Caspase-3 | [180] |

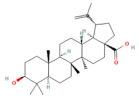

| Betulinic acid | Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Betula platyphylla | 1, 5, or 10 mg/kg i.p | ↓ IκBα degradation, NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2, CXCL2, MPO | [181] |

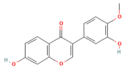

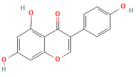

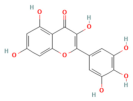

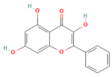

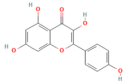

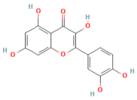

| Genistein | Flavonoids soy and other legumes | 10, 100 mg/kg i.p | ↓ NF-κB p65, TNF-α, iNOS, COX-2, MPO | [182] |

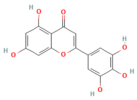

| Myricetin | Flavonoid fruits and vegetables | 0.5, 2, 5 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ Calcineurin activity, CaMKK2, CaMKIV, NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, Cathepsin B ↑ AMPK, SIRT1 | [94] |

| Nanocurcumin | Polyphenol Curcuma longa | 100 mg/kg/day | ↓ TLR4, NF-κB p65, TNF-α | [98] |

| Nimbolide | Limonoid (from Azadirachta indica/neem) | 0.3 and 1 mg/kg i.p | ↓ IκBα degradation, NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, nitrotyrosine, ↑ SIRT1 | [183] |

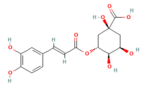

| Protocatechuic acid | Phenolic acid Ginkgo biloba, Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | 50, 100 mg/kg oral | ↓ HMGB1, TLR4, NF-κB p65, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α | [184] |

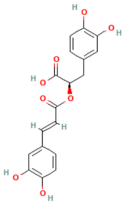

| Rosmarinic acid | Polyphenolic caffeic acid ester rosemary, sage, lemon balm | 50 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | [185] |

| Tricetin | Flavonoids Eucalyptus | 10, 30 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ NF-κB p65, MPO, TNF-α, IL-6, PARP1 | [186] |

| MAPK pathway | ||||

| Anemarsaponin B | Steroidal saponin Anemarrhena asphodeloides | 20, 40, 80 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ Occludin-TAK1, p-JNK, p-ERK, p-p38, TRAF6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, cleaved caspase-3 ↑ SOD, GSH-Px | [109] |

| Calycosin | Isoflavonoid Radix astragali | 25, 50 mg/kg i.p. | ↓p38 MAPK and NF-κB, NF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, MDA ↑ SOD, GSH-Px | [187] |

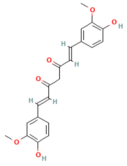

| Curcumin | Polyphenol Curcuma longa | 200 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, TNF-α, and CRP | [173] |

| Dihydromyricetin | Flavonoid Ampelopsis grossedentata | 25, 100 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ TRAF3, TRAF3–MKK3, p38 MAPK, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17 | [188] |

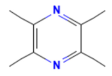

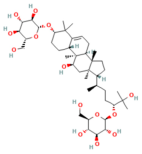

| Glycyrrhizin | Triterpenoid saponin Glycyrrhiza glabra | NA | ↓ ERK1/2, STAT3, AKT | [189] |

| Green tea polyphenols | Catechins Camellia sinensis | 25 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ NF-κB, NF-κB p65, TNF-α, TGF-ββ, VEGF, ICAM-1, P-selectin, PARS | [190] |

| Ligustrazine | Alkaloid Ligusticum wallichii | 150 mg/kg day i.p. | ↓ p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 ↑ p53, cleaved caspase-3 | [191] |

| Stigmasterol | Phytosterol, vegetable oils, nuts, seeds, and legumes | 50, 100 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ ERK1, KRAS, B-RAF, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β | [192] |

| Nrf2 pathway | ||||

| Galangin | Flavonol Plantago major L., Alpinia officinarum Hance, and Scutellaria galericulata L. | 50 mg/kg Oral | ↓ ROS levels, M1 macrophage polarization ↑ Nrf2, SRXN1 | [158] |

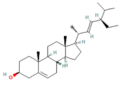

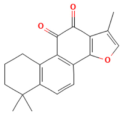

| Tanshinone IIA | Diterpenoid quinone Salvia miltiorrhiza | 5, 25, 50 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ ROS, MDA ↑ Nrf2, ↑ HO-1 | [79] |

| Triptolide | Diterpene triepoxide Tripterygium wilfordii Hook.f. | 50, 100 μg/kg Oral | ↑ Nrf2, HO-1, SOD1, GPx1, NQO1, GSH, SOD ↓ ROS and MDA, NF-κB p65 | [193] |

| Visengin | Furanocoumarin derivative Ammi visnaga | 10, 30, 60 mg/kg oral | ↑ Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1 ↓ NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β | [27] |

| Antioxidant/Anti-inflammatory pathway | ||||

| Chlorogenic acid | Polyphenols, coffee beans, cocoa leaves and seeds, yerba mate | 20 mg/kg oral | ↓ MPO, MIF, Serum amylase | [194] |

| Withaferin A | Steroidal lactone roots of Withania somnifera | 2 and 10 mg/kg Oral | ↓ MDA, NO, MPO, nitro tyrosine ↑ GSH | [195] |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | ||||

| Dihydro- diosgenin | Steroidal saponins Dioscorea zingiberensis C. H. | (5 or 10 mg·kg−1) i.p. | ↓ (ΔΨm) loss, ATP depletion, ROS, PI3K/Akt pathway | [170] |

| Dioscorea zingiberensis | Phenolic compounds rhizomes of D. zingiberensis | 0.5 mM of compound 6 In vitro | ↓ATP depletion and ROS generation | [196] |

| Rhizoma Alismatis Decoction | Genus: Alisama, Juzep Atractylodes, macrocephala Koidz | (36 g crude drug/kg/d) 4 g crude drug/kg Oral | ↓ p16INK4a, p21, p62 ↑ Beclin-1, ATG5, LC3-II | [172] |

| MicroRNA pathway | ||||

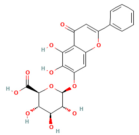

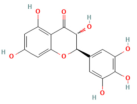

| Baicalin | Flavonoid Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi | 50, 100 mg/kg (i.p.) (5−75 μM) in vitro | ↑ miR-15a, ↓ MAP2K4, CDC42, MAP3K1 ↓ miR-136-5p/↑ SOD | [159,197] |

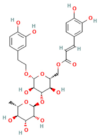

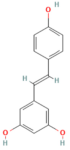

| Quercetin | Flavonoid Fruits and vegetables | 50 and 100 mg/kg oral | ↑ miR-216b ↓ MAP2K6, NEAT1, TRAF2 | [17] |

| Pinocembrin | Flavonoid propolis | 10 mg/kg oral | ↓ miR-34a-5p → ↑ SIRT1 → ↑ PPAR-α and IκB-α → ↓ NF-Κb/↑ Pancreatic Nrf2 and HO-1 | [16] |

| Phytochemical Name | Class/Plant | Therapeutic Dose/Route of Administration | Main Target Pathway/Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium signaling | ||||

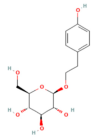

| Resveratrol | Polyphenol Grape | 10 mg/kg i.v | ↑ Ca2+-ATPase activities, Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase activity, ↓ [Ca2+]i, PLA2activity | [198] |

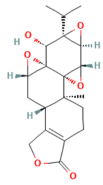

| Urolithin A | Coumarins Pomegranate (Punica granatum) | 30 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ IP3R, VDAC1, GRP75, MPTP opening, Cytochrome c release, RIPK1/RIPK3 | [59] |

| Ferroptosis pathway | ||||

| Da Cheng Qi Decoction | Decoction of rhubarb, mirabilitum, bitter orange, and magnolia bark | 7 g/kg oral | ↓ Ferroptosis ↓ NOX2, ROS ↑ GPX4 | [199] |

| Matrine | Alkaloid herbal plants | 200 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ Ferroptosis ↑ UCP2, PGC1α, GPX4, SLC7A11 | [72] |

| Neferine | Bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids of Nelumbinis plumula | 50, 75 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ Ferroptosis ↑ NRF2, HO-1, GPX4, FPN | [152] |

| NF-κB pathway | ||||

| Berberine | Isoquinoline alkaloid coptis chinensis, phellodendron chinensis, or three needles | 10 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ NF-κB p65, JNK, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MPO | [200] |

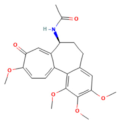

| Colchicine | Alkaloid Autumn crocus | 0.5 mg/kg oral | ↓ NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, STAT3, AKT, iNOS, MPO, ROS | [201] |

| Isoacteoside | Coumaricacids Monochasma savatieri Franch. Ex Maxim | 40 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ TLR4, NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-6, MPO, NO | [202] |

| p38/MAPK pathway | ||||

| Albiflorin | Monoterpenoid Paeonia lactiflora Pall. or Paeonia veitchii Lynch | 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ p-p38 MAPK, NF-κB p65, ALT, AST, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, MDA ↑ SOD and GSH-Px | [203] |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid Fruits and vegetables | 50 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ TLR4, MyD88, p-p38 MAPK, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17, Bip, p-IRE1α, sXBP1, p-eIF2α, ATF6 ↑ ZO-1, occludin, claudin-1 | [204] |

| Nrf2 pathway | ||||

| Dihydro- kaempferol | Flavonoid Bauhinia championii (Benth) | 20, 40, 80 mg/kg oral | ↓ Keap1, ↓ MDA, and ROS ↑ Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, GSH | [160] |

| Galangin | Flavonol lesser galangal | 10, 20, or 40 mg/kg Oral | ↑ Nrf2, HO-1 ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, ROS | [86] |

| Kaempferol | Flavonoid leafy green vegetables: broccoli, cabbage, spinach, | 25 or 50 mg/kg KA (oral); 2.5 or 5 mg/kg (DTM@KA NPs) i.v | ↑ Nrf2, GSH, Drp1, Pink1/Parkin, ATP production ↓ ROS | [205] |

| Micheliolide | Sesquiterpene lactone Michelia champaca | 25, 50 mg/kg Oral | ↑ Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1 ↓ NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, ROS | [89] |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | ||||

| Isorhamnetin | methylated derivative of quercetin | 10, 30 mg/kg i.p. | Mitochondrial dysfunction ↓ ROS, mtDNA, KDM5B ↑ ATP, HtrA2 | [171] |

| MicroRNA | ||||

| Emodin | Anthraquinone Rheum palmatum L., Polygonum multiflorum Thunb., and Polygonum cuspidatum Siebold and Zucc. | 40 mg/kg Oral | ↑ rno-miR-29a-3p ↓ Macrophage activation | [132] |

| Salidroside | phenolic glycoside Rhodiola rosea L. | 20 mg/kg i.p. | ↓ miR-217-5p, p38 MAPK ↑ YAF2 | [206] |

| Phytochemical Name | Class/Plant | Therapeutic Dose/Route of Administration | Main Target Pathway/Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puerarin | Isoflavones Radix Puerariae | 100 mg/kg Oral | MAPK signaling ↓ JNK1/2, ERK1/2,p38 MAPK, α-SMA, Fibronectin, Col1α1, GFAP | [115] |

| Curcumin | Polyphenol Curcuma longa | 10 or 20 mg/kg i.p. | Nrf-2 pathway ↑ Nrf2, HO-1 ↓ TGF-β1, α-SMA, Col1a1, Col4a1, Fn1 | [26] |

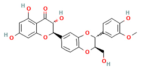

| Catechin hydrate | Flavonoids green tea | 1, 5 or 10 mg/kg i.p. | TGF-β/Smad2 ↓ TGF-β1, Smad2, α-SMA/Acta2, fibronectin 1, collagen-I/III/IV | [207] |

| Psidium guajava Flavonoids | Flavonoids Psidium guajava | Anti-inflammatory ↓ NLRP3, IL-1β, IL-18, Caspase-1 | [208] |

| Phytochemical/Intervention | Study Type and Setting | Population (n) | Type of Model/Control Used | Dose/Route/Duration | Key Outcomes | Statistical Significance | Safety/Toxicity | Major Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese herbal medicine + Western medicine (broader AP population) | Systematic review and meta-analysis (Front Pharmacol. 2025) | Multiple RCTs pooled (counts vary by endpoint) | Clinical population (acute pancreatitis); controls = standard Western care | Varies; oral decoctions most common | ↑ clinical efficacy (RR≈1.26); ↓ TNF-α, IL-6; ↓ time to pain relief; ↓ ICU stay | All pooled endpoints statistically significant (p < 0.05) | Safety acceptable overall; AE reporting heterogeneous | Risk of bias; heterogeneity in interventions and endpoints | [209] |

| Nanocurcumin (adjuvant to standard care) | Double-blind RCT; single center (Iran) | Mild/moderate AP (n = 42; 21 vs. 21) | Randomized control; placebo group (identical capsule) | 40 mg nanocurcumin twice daily (oral), 2 weeks | ↓ GI ward length of stay; ↓ analgesic requirement; ↑ appetite score | p < 0.05 for all endpoints | No adverse effects reported; no mortality; no withdrawals | Small sample; single center; short follow-up; adjuvant use only | [210] |

| Chinese herbal medicine (various multi-herb formulas) + Western medicine vs. Western medicine alone | Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs in hyperlipidemic AP | 50 trials; n = 3635 total | Clinical trials vs. Western medicine control arms | Varies by formula; mostly oral decoctions; inpatient courses | Improved composite clinical efficacy; ↓ inflammatory markers; faster symptom resolution | Pooled effect sizes significant (p < 0.01) | Generally reported as safe; adverse event reporting inconsistent/limited | Heterogeneity; variable formula composition; risk of bias concerns | [211] |

| Dachengqi (Chaiqinchengqi) series formulas (TCM) | Randomized trials and meta-analyses in AP/SAP (China) | Multiple small-to-moderate RCTs | AP/SAP patients vs. standard care; placebo/sham in some | Oral/NG decoctions; duration varies | ↓ mortality; ↓ hospital stay; ↓ surgery rate; ↓ serum resistin (some trials) | p < 0.05 in most studies; meta-analytic effect confirmed | Generally, well tolerated; variable AE reporting | Methodological quality variable; publication bias possible; formula heterogeneity | [212] |

| Resveratrol (pre-ERCP to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis) | Registered clinical trial (status unclear) | Adults undergoing ERCP (planned) | Preventive model; placebo control planned | Oral resveratrol pre-procedure (planned regimen) | Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis (primary) | Not reported/trial results pending | Not reported | Results not posted/unclear | [213] |

| Study/Ref. | Species/Strain and Sex | Control Details | Model (Trigger) | Induction Details (Dose, Route, Schedule) | Severity Determination (Pre-Specified Readouts) | Primary Outcomes | Statistical Significance | Toxicity/Safety | Key Model Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | Mouse (C57BL/6J), Male | Saline-injected controls under identical timing and handling | Caerulein (CCK analog) | 50 μg/kg IP, hourly × 6 (±LPS 10 μg/kg) | Serum amylase/lipase; pancreatic histology score (edema/infiltrate/vacuolization/necrosis); MDA; cytokines | ↓ Enzyme rise; ↓ histologic injury; ↓ MPO | p < 0.05 vs. control | No weight loss; no mortality | Mild, reversible edema-predominant AP; limited necrosis |

| SAP | Mouse (C57BL/6J), Male | Sham-operated mice (saline duct infusion) | NaT retrograde infusion | 2.5% NaT, 10 μL/min × 3 min via biliopancreatic duct | % necrosis; hemorrhage; ALI score; lung MPO; BUN/Cr; IL-6 | ↓ Pancreatic necrosis; ↓ ALI; ↑ ATP | p < 0.01 for biochemical and histologic scores | Peri-op mortality reported | Surgical model; uneven injury near the main duct |

| AP (alcoholic) | Rat, Male | Vehicle (ethanol alone) | FAEE (EtOH + POA) | Ethanol + palmitoleic/oleic acid, IP | Ca2+ overload indices; mitochondrial ΔΨm; amylase/lipase; histology | ↓ Ca2+ overload; ↓ necrosis | p < 0.05 | – | Protocol/strain variability |

| CP | Mouse, Male | Saline-injected controls | Repeated caerulein | 50 μg/kg/h, 6 h/day, 2 days/week × 10 weeks | Fibrosis score; Sirius Red; hydroxyproline; α-SMA/Col-I | ↓ Fibrosis; ↓ PSC activation markers | p < 0.001 | – | Models fibrosis but not pain/duct obstruction |

| CP | Rat, Male, Female | Sham laparotomy without duct ligation | PDL | Ligation of pancreatic duct(s) | Atrophy/fibrosis; ECM markers | ↓ Fibrosis progression | p < 0.05 | Surgical risk | Mouse ductal anatomy complicates uniform PDL |

6. Clinical Evidence of Phytochemical Interventions in Pancreatitis

6.1. Nanocurcumin

6.2. Chaiqinchengqi Decoction

6.3. Dachengqi Decoction

7. Preclinical Animal Models and Severity Assessment: Models, Readouts, and Limitations

8. Assessment of Lipinski’s Rule of Five and Absorption Properties

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ach | Acetylcholine |

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 |

| ALOX | Arachidonate lipoxygenase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ANAPC13 | Anaphase-promoting complex subunit 13 |

| ANP | Acute necrotizing pancreatitis |

| AP | Acute pancreatitis |

| AR42J | Rat pancreatic acinar-like cell line |

| BAPTA | 1,2-Bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (Ca2+ chelator) |

| BMSCs | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells |

| Caco-2 | Human intestinal epithelial cell line used for permeability assays |

| CAE | Caerulein |

| cADPR | Cyclic ADP-ribose |

| CCK | Cholecystokinin |

| CCK | Cholecystokinin receptor type |

| CCN2 | Cellular communication network factor 2 |

| CD36 | Cluster of differentiation 36 |

| CDE | Choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented (diet) |

| COX5A | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5A |

| CP | Chronic pancreatitis |

| CRAC | Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel |

| Cyt c | Cytochrome c |

| DCQD | Da Cheng Qi decoction |

| DHODH | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ERBB3 | Receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB3/HER3 |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FAEE | Fatty acid ethyl ester |

| FAT10 | HLA-F adjacent transcript 10 |

| FoxO1 | Forkhead box O1 |

| FPN (SLC40A1) | Ferroportin (iron exporter) |

| FSP1 (AIFM2) | Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 |

| FTH1 | Ferritin heavy chain 1 |

| FTL | Ferritin light chain |

| GCLC/GCLM | Glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic/modifier subunit |

| GCH1 | GTP cyclohydrolase 1 |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| Grp75 | Mitochondrial chaperone mortalin/Grp75 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha |

| HMGB1 | High-mobility group box-1 |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HSP | Heat-shock protein |

| HTGP | Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis |

| IDH2 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (mitochondrial) |

| IEP | Interstitial edematous pancreatitis |

| IKKβ | IκB kinase beta |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IP3 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate |

| IP3R | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| KO | Knockout |

| LPCAT3 | Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAP2K4/MAP2K6 | MAPK kinase 4/6 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCU | Mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter |

| MEK | MAPK/ERK (MAP2K1/2) |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MK2 | MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 |

| MOD | Multiple organ dysfunction |

| MPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| mTORC2 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 |

| MNCX/NCLX | Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger |

| MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 |

| NAADP | Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NaT | Sodium taurocholate |

| NFAT | Nuclear factor of activated T cells |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| NP | Necrotizing pancreatitis |

| OA | Oleic acid |

| Orai1 | Calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1 |

| PAK1 | p21-activated kinase 1 |

| PAC | Pancreatic acinar cell |

| PDL | Pancreatic duct ligation |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1 alpha |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PLA2 | Phospholipase A2 |

| PMCA | Plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| PTK2 | Protein tyrosine kinase 2 |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| PUFA-PL | PUFA-containing phospholipid |

| RELA | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A |

| Rictor | Rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR |

| RIP1/3 | Receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1/3 |

| Ro5 | Lipinski’s Rule of Five |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RyR | Ryanodine receptor |

| SAP | Severe acute pancreatitis |

| SAP-ALI | Severe acute pancreatitis-associated acute lung injury |

| SARAF | SOCE-associated regulatory factor |

| SERCA | Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase |

| SIRT3/SIRT4 | Sirtuin-3/Sirtuin-4 |

| SLC3A2 | Solute carrier family 3 member 2 |

| SLC7A11 | Cystine/glutamate antiporter light chain |

| SOCE | Store-operated Ca2+ entry |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase 1 |

| STIM1 | Stromal interaction molecule 1 |

| TAK1 | TGF-β-activated kinase 1 |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase 1 |

| TCA | Taurocholic acid |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TNFRSF1A | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TRAF3/6 | TNF receptor-associated factor 3/6 |

| TRP | Transient receptor potential |

| TRPC3/TRPC6 | Transient receptor potential canonical channels 3/6 |

| TRPV | Transient receptor potential vanilloid |

| UCP2 | Uncoupling protein-2 |

| USP25 | Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 25 |

| VDAC1 | Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens-1 |

References

- Foster, B.R.; Jensen, K.K.; Bakis, G.; Shaaban, A.M.; Coakley, F.V. Revised Atlanta classification for acute pancreatitis: A pictorial essay. Radiographics 2016, 36, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryvoruchko, I.A.; Kopchak, V.M.; Usenko, O.; Honcharova, N.M.; Balaka, S.M.; Teslenko, S.M.; Andreieshchev, S.A. Classification of an acute pancreatitis: Revision by international consensus in 2012 of classification, adopted in Atlanta. Klin. Khirurhiia 2014, 9, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mederos, M.A.; Reber, H.A.; Girgis, M.D. Acute pancreatitis: A review. JAMA 2021, 325, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, A.Y.; Tan, M.L.; Wu, L.M.; Asrani, V.M.; Windsor, J.A.; Yadav, D.; Petrov, M.S. Global incidence and mortality of pancreatic diseases: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of population-based cohort studies. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 1, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, O.H.; Sutton, R. Ca2+ signalling and pancreatitis: Effects of alcohol, bile and coffee. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 27, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, J.V.; Gerasimenko, O.V.; Petersen, O.H. The role of Ca2+ in the pathophysiology of pancreatitis. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, J.; Wen, L.; Huang, K.; Liu, H.; Zeng, L.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Mo, Z. Ion channels in acinar cells in acute pancreatitis: Crosstalk of calcium, iron, and copper signals. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1444272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramnath, R.D.; Sun, J.; Adhikari, S.; Zhi, L.; Bhatia, M. Role of PKC-δ on substance P-induced chemokine synthesis in pancreatic acinar cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008, 294, C683–C692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Lugea, A.; Zheng, L.; Gukovsky, I.; Edderkaoui, M.; Rozengurt, E.; Pandol, S.J. Protein kinase D1 mediates NF-κB activation induced by cholecystokinin and cholinergic signaling in pancreatic acinar cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 295, G1190–G1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Gong, Y.; He, P.; Qi, M.; Dong, W. 4-octyl Itaconate Attenuates Acute Pancreatitis and Associated Lung Injury by Suppressing Ferroptosis in Mice. Inflammation 2025, 48, 3156–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xu, M. The role of iron and ferroptosis in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. J. Histotechnol. 2023, 46, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, H.; Mei, C.; Cui, M.; He, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, D.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; et al. Sirtuin4 alleviates severe acute pancreatitis by regulating HIF-1α/HO-1 mediated ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntzinger, E.; Izaurralde, E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: Contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsaro, J.J.; Joshua-Tor, L. From guide to target: Molecular insights into eukaryotic RNA-interference machinery. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharap, A.; Pokrzywa, C.; Murali, S.; Pandi, G.; Vemuganti, R. MicroRNA miR-324-3p induces promoter-mediated expression of RelA gene. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.M.; Al-Mokaddem, A.K.; Selim, H.M.R.M.; Alherz, F.A.; Saleh, A.; Hamdan, A.M.E.; Ousman, M.S.; El-Emam, S.Z. Pinocembrin’s protective effect against acute pancreatitis in a rat model: The correlation between TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 and miR-34a-5p/SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, B.; Zhao, L.; Zang, X.; Zhen, J.; Liu, Y.; Bian, W.; Chen, W. Quercetin inhibits caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis through regulating miR-216b by targeting MAP2K6 and NEAT1. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beij, A.; Verdonk, R.C.; van Santvoort, H.C.; de-Madaria, E.; Voermans, R.P. Acute Pancreatitis: An Update of Evidence-Based Management and Recent Trends in Treatment Strategies. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2025, 13, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tłustochowicz, K.; Krajewska, A.; Kowalik, A.; Małecka-Wojciesko, E. Treatment Strategies for Chronic Pancreatitis (CP). Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckler, M.; Hackert, T.; Hu, K.; Halloran, C.M.; Büchler, M.W.; Neoptolemos, J.P. Severe acute pancreatitis: Surgical indications and treatment. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachheti, A.; Sharma, A.; Bachheti, R.; Husen, A.; Pandey, D. Plant allelochemicals and their various applications. In Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Asmamaw, D.; Achamyeleh, H. Assessment of medicinal plants and their conservation status in case of Daligaw Kebela, Gozamen Werda, East Gojjam Zone. J. Biodivers. Bioprospect. Dev. 2018, 5, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaymaz, K.; Hensel, A.; Beikler, T. Polyphenols in the prevention and treatment of periodontal disease: A systematic review of in vivo, ex vivo and in vitro studies. Fitoterapia 2019, 132, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, M.; Datta, A. Fundamentals of phytochemicals. In Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics: Focus on Phytochemicals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-U.; Kweon, B.; Oh, J.-Y.; Noh, G.-R.; Lim, Y.; Yu, J.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, D.-G.; Park, S.-J.; Bae, G.-S. Curcumin ameliorates cerulein-induced chronic pancreatitis through Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 31, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasari, L.P.; Khurana, A.; Anchi, P.; Saifi, M.A.; Annaldas, S.; Godugu, C. Visnagin attenuates acute pancreatitis via Nrf2/NFκB pathway and abrogates associated multiple organ dysfunction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, F.S.; Lerch, M.M. Do animal models of acute pancreatitis reproduce human disease? Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 4, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Cerulein pancreatitis: Oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Gut Liver 2008, 2, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Tang, X.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J. Melatonin attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress in acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 2018, 47, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendler, M.; Weiss, F.-U.; Golchert, J.; Homuth, G.; van den Brandt, C.; Mahajan, U.M.; Partecke, L.-I.; Döring, P.; Gukovsky, I.; Gukovskaya, A.S.; et al. Cathepsin B-mediated activation of trypsinogen in endocytosing macrophages increases severity of pancreatitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 704–718.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criddle, D.N.; Murphy, J.; Fistetto, G.; Barrow, S.; Tepikin, A.V.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Sutton, R.; Petersen, O.H. Fatty acid ethyl esters cause pancreatic calcium toxicity via inositol trisphosphate receptors and loss of ATP synthesis. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yao, L.; Fu, X.; Mukherjee, R.; Xia, Q.; Jakubowska, M.A.; Ferdek, P.E.; Huang, W. Experimental acute pancreatitis models: History, current status, and role in translational research. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 614591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Tang, H.; Liang, S.; Shi, X.; Liu, Z. Beneficial effects of trypsin inhibitors derived from a spider venom peptide in L-arginine-induced severe acute pancreatitis in mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales-Munoz, G.J.; Souza-Arroyo, V.; Bucio-Ortiz, L.; Miranda-Labra, R.U.; Gomez-Quiroz, L.E.; Gutierrez-Ruiz, M.C. Acute pancreatitis experimental models, advantages and disadvantages. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 81, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Tang, X.; Wu, Q.; Ren, P.; Yan, Y. A severe acute pancreatitis mouse model transited from mild symptoms induced by a “two-hit” strategy with L-arginine. Life 2022, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, M.B.; Koike, M.K.; Barbeiro, D.F.; Machado, M.C.C.; de Souza, H.P. Sodium taurocholate induced severe acute pancreatitis in c57bl/6 mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2021, 28, 34251363. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, J.J.; Lee, H.S. Experimental models of pancreatitis. Clin. Endosc. 2014, 47, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Otani, M.; Otsuki, M. A new model of chronic pancreatitis in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006, 291, G700–G708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonlaufen, A.; Xu, Z.; Daniel, B.; Kumar, R.K.; Pirola, R.; Wilson, J.; Apte, M.V. Bacterial endotoxin: A trigger factor for alcoholic pancreatitis? Evidence from a novel, physiologically relevant animal model. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, O.H.; Gerasimenko, J.V.; Gerasimenko, O.V.; Gryshchenko, O.; Peng, S. The roles of calcium and ATP in the physiology and pathology of the exocrine pancreas. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1691–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboloff, J.; Hooper, R. STIMATE reveals a STIM1 transitional state. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1232–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, R.T.; Chen, Y.; Pham, H.; Go, A.; Su, H.Y.; Hu, C.; Wen, L.; Husain, S.Z.; Sugar, C.A.; Roos, J. The Orai Ca2+ channel inhibitor CM4620 targets both parenchymal and immune cells to reduce inflammation in experimental acute pancreatitis. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 3085–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Ahuja, M.; Maléth, J.; Moreno, C.M.; Yuan, J.P.; Kim, M.S.; Muallem, S. The STIM1 CTID domain determines access of SARAF to SOAR to regulate Orai1 channel function. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maléth, J.; Choi, S.; Muallem, S.; Ahuja, M. Translocation between PI (4, 5) P2-poor and PI (4, 5) P2-rich microdomains during store depletion determines STIM1 conformation and Orai1 gating. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerasimenko, J.V.; Gerasimenko, O.V. The role of Ca2+ signalling in the pathology of exocrine pancreas. Cell Calcium 2023, 112, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruen, C.; Miller, J.; Wilburn, J.; Mackey, C.; Bollen, T.L.; Stauderman, K.; Hebbar, S. Auxora for the treatment of patients with acute pancreatitis and accompanying systemic inflammatory response syndrome: Clinical development of a calcium release-activated calcium channel inhibitor. Pancreas 2021, 50, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogami, H.; Tepikin, A.V.; Petersen, O.H. Termination of cytosolic Ca2+ signals: Ca2+ reuptake into intracellular stores is regulated by the free Ca2+ concentration in the store lumen. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogami, H.; Nakano, K.; Tepikin, A.V.; Petersen, O.H. Ca2+ flow via tunnels in polarized cells: Recharging of apical Ca2+ stores by focal Ca2+ entry through basal membrane patch. Cell 1997, 88, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-W.; Shin, J.Y.; Jo, I.-J.; Kim, D.-G.; Song, H.-J.; Yoon, C.-S.; Oh, H.; Kim, Y.-C.; Bae, G.-S.; Park, S.-J. 8α-Hydroxypinoresinol isolated from Nardostachys jatamansi ameliorates cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis through inhibition of NF-κB activation. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 114, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.-G.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, F. NFAT gene family in inflammation and cancer. Curr. Mol. Med. 2013, 13, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Javed, T.A.; Yimlamai, D.; Mukherjee, A.; Xiao, X.; Husain, S.Z. Transient high pressure in pancreatic ducts promotes inflammation and alters tight junctions via calcineurin signaling in mice. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1250–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.-D.; Yu, T.; Liu, H.-J.; Jin, J.; He, J. SOCE induced calcium overload regulates autophagy in acute pancreatitis via calcineurin activation. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habtezion, A.; Gukovskaya, A.S.; Pandol, S.J. Acute pancreatitis: A multifaceted set of organelle and cellular interactions. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hann, J.; Bueb, J.-L.; Tolle, F.; Bréchard, S. Calcium signaling and regulation of neutrophil functions: Still a long way to go. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 107, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, D.; Johnson, R.; Pashos, M.; Cummings, C.; Kang, C.; Sampedro, G.R.; Tycksen, E.; McBride, H.J.; Sah, R.; Lowell, C.A.; et al. ORAI1 and ORAI2 modulate murine neutrophil calcium signaling, cellular activation, and host defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24403–24414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, M.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, B.; Bao, J.; Dai, J.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Li, L.; Pandol, S.; et al. Neutrophil-specific ORAI1 calcium channel inhibition reduces pancreatitis-associated acute lung injury. Function 2024, 5, zqad061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, C.; Shi, K.; Huang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Huang, W. AICAR, an AMP-activated protein kinase activator, ameliorates acute pancreatitis-associated liver injury partially through Nrf2-mediated antioxidant effects and inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 724514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Hu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Huang, G.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, L.; Su, H.; Tang, W.; Wan, M. Urolithin A’s Role in Alleviating Severe Acute Pancreatitis via Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Calcium Channel Modulation. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 13885–13898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Mareninova, O.A.; Odinokova, I.V.; Huang, W.; Murphy, J.; Chvanov, M.; Javed, M.A.; Wen, L.; Booth, D.M.; Cane, M.C.; et al. Mechanism of mitochondrial permeability transition pore induction and damage in the pancreas: Inhibition prevents acute pancreatitis by protecting production of ATP. Gut 2016, 65, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Olzmann, J.A. The cell biology of ferroptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassannia, B.; Vandenabeele, P.; Vanden Berghe, T. Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, V.E.; Mao, G.; Qu, F.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Doll, S.; Croix, C.S.; Dar, H.H.; Liu, B.; Tyurin, V.A.; Ritov, V.B.; et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Kim, K.J.; Gaschler, M.M.; Patel, M.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E4966–E4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhu, W.; Wei, L.; Zhao, J. Iron homeostasis imbalance and ferroptosis in brain diseases. MedComm 2023, 4, e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Amino acid transporter SLC7A11/xCT at the crossroads of regulating redox homeostasis and nutrient dependency of cancer. Cancer Commun. 2018, 38, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Che, B.; Zhang, W.; Du, D.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Yu, X.; Ye, M.; Wang, W.; et al. Mechanistic insights into the role of FAT10 in modulating NCOA4-mediated ferroptosis in pancreatic acinar cells during acute pancreatitis. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, L.; Meng, N.; Lei, Y.; Feng, Y.; Tang, G. Liproxstatin-1 attenuates acute hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis through inhibiting ferroptosis in rats. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhao, K.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Liao, S.; Sun, S. Matrine alleviates oxidative stress and ferroptosis in severe acute pancreatitis-induced acute lung injury by activating the UCP2/SIRT3/PGC1α pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 117, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Wang, D.; Zheng, C.; Xie, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.; Hong, W. Elimination of intracellular Ca2+ overload by BAPTA-AM liposome nanoparticles: A promising treatment for acute pancreatitis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 53, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, X.; Feng, S.; Shao, H. Lactate-Dependent HIF1A Transcriptional Activation Exacerbates Severe Acute Pancreatitis Through the ACSL4/LPCAT3/ALOX15 Pathway Induced Ferroptosis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 126, e30687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, J.; Zou, B.; Li, C.; Zeh, H.J.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G.; Huang, J.; Tang, D. Trypsin-mediated sensitization to ferroptosis increases the severity of pancreatitis in mice. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 13, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, Q.; Yu, H.; Du, H. Secondary iron overload induces chronic pancreatitis and ferroptosis of acinar cells in mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 51, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, M. Stress-sensing mechanisms and the physiological roles of the Keap1–Nrf2 system during cellular stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 16817–16824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykiotis, G.P. Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yuan, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, X.; Xiao, W.; Gong, W.; Huang, W.; Xia, Q.; Lu, G.; et al. Tanshinone IIA protects against acute pancreatitis in mice by inhibiting oxidative stress via the Nrf2/ROS pathway. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5390482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardyn, J.D.; Ponsford, A.H.; Sanderson, C.M. Dissecting molecular cross-talk between Nrf2 and NF-κB response pathways. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimmulappa, R.K.; Lee, H.; Rangasamy, T.; Reddy, S.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Biswal, S. Nrf2 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and survival during experimental sepsis. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Sui, J.; Fan, R.; Qu, W.; Dong, X.; Sun, D. Emodin protects against acute pancreatitis-associated lung injury by inhibiting NLPR3 inflammasome activation via Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 1971–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Fang, R.; Ding, J.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, M.; Zhou, F.; Liu, F.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Jiang, K.; et al. Melatonin ameliorates multiorgan injuries induced by severe acute pancreatitis in mice by regulating the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 975, 176646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzinger, M.; Fischhuber, K.; Pölöske, D.; Mechtler, K.; Heiss, E.H. AMPK leads to phosphorylation of the transcription factor Nrf2, tuning transactivation of selected target genes. Redox Biol. 2020, 29, 101393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.-L.; Zhao, B.; Sun, S.-L.; Yu, S.-F.; Wang, Y.-M.; Ji, R.; Yang, Z.-T.; Ma, L.; Yao, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. High-dose vitamin C alleviates pancreatic injury via the NRF2/NQO1/HO-1 pathway in a rat model of severe acute pancreatitis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.-D.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Li, D.-J.; Yang, S.-J.; Wang, Q.-F.; Liu, Y.-N.; Li, M.-K.; Mei, C.-P.; Cui, H.-N.; Chen, S.-Y.; et al. Galangin ameliorates severe acute pancreatitis in mice by activating the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2/heme oxygenase 1 pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Z.; Rützler, M.; Lu, Q.; Xu, H.; Andersson, R.; Dai, Y.; Shen, Z.; Calamita, G.; et al. Inhibition of aquaporin-9 ameliorates severe acute pancreatitis and associated lung injury by NLRP3 and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 137, 112450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Zheng, C.; Xu, X.; Ni, X.; Hu, S.; Cai, B.; Sun, L.; Shi, K.; et al. DPP4 Inhibitor Attenuates Severe Acute Pancreatitis-Associated Intestinal Inflammation via Nrf2 Signaling. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 6181754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Wang, K.-Q.; Qin, Y.-Y.; Wang, H.-W.; Wu, M.-M.; Zhu, X.-D.; Lu, X.-Y.; Zhu, M.-M.; Lu, C.-S.; Hu, Q.-Q. Micheliolide ameliorates severe acute pancreatitis in mice through potentiating Nrf2-mediated anti-inflammation and anti-oxidation effects. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Sun, W.; Tang, X.; Chen, J.; Zheng, H.; Yang, G.; Yao, G. Bufalin alleviates inflammatory response and oxidative stress in experimental severe acute pancreatitis through activating Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 and inhibiting NF-κB pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 142, 113113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakonczay, Z.; Hegyi, P.; Takacs, T.; McCarroll, J.; Saluja, A.K. The role of NF-κB activation in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2008, 57, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakkampudi, A.; Jangala, R.; Reddy, B.R.; Mitnala, S.; Reddy, D.N.; Talukdar, R. NF-κB in acute pancreatitis: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Pancreatology 2016, 16, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muili, K.A.; Jin, S.; Orabi, A.I.; Eisses, J.F.; Javed, T.A.; Le, T.; Bottino, R.; Jayaraman, T.; Husain, S.Z. Pancreatic acinar cell nuclear factor κB activation because of bile acid exposure is dependent on calcineurin. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 21065–21073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.-W.; Shin, J.; Zhou, Z.; Song, H.-J.; Bae, G.-S.; Kim, M.S.; Park, S.-J. Myricetin ameliorates the severity of pancreatitis in mice by regulating cathepsin B activity and inflammatory cytokine production. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 136, 112284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, I.; Yorek, M.A.; Zaheer, A.; Fisher, R.A. Bile-pancreatic juice exclusion promotes Akt/NF-k B activation and chemokine production in ligation-induced acute pancreatitis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2006, 10, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Signaling to NF-κB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.-G.; Xia, Q.-J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.-G.; Cao, G.-Q.; Wang, R.; Lu, Y.-L.; Hu, T.-Z. Toll-like receptor 4 detected in exocrine pancreas and the change of expression in cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas 2005, 30, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian, A.; Ghafari, H.; Chamanara, M.; Dehpour, A.; Muhammadnejad, A.; Akbarian, R.; Mousavi, S.E.; Rezayat, S. The protective effect of nano-curcumin in experimental model of acute pancreatitis: The involvement of TLR4/NF-kB pathway. Nanomed. J. 2018, 5, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dong, W.-H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J. Two-layer regulation of TRAF6 mediated by both TLR4/NF-kB signaling and miR-589-5p increases proinflammatory cytokines in the pathology of severe acute pancreatitis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 2379. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Wu, X.; Yang, L.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, X.; Yuan, H. TLR4-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway mediates HMGB1-induced pancreatic injury in mice with severe acute pancreatitis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, C.S.; Vidhya, R.; Kalpana, K.; Anuradha, C. Indirubin-3′-monoxime prevents aberrant activation of GSK-3β/NF-κB and alleviates high fat-high fructose induced Aβ-aggregation, gliosis and apoptosis in mice brain. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 70, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Chen, C.; Shi, Q.; Deng, W.; Zuo, T.; He, X.; Liu, T.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β attenuates acute kidney injury in sodium taurocholate-induced severe acute pancreatitis in rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 3185–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-F.; Liu, F.; Xin, J.-Q.; Fan, J.-W.; Wu, N.; Zhu, L.-J.; Duan, L.-F.; Li, Y.-Y.; Zhang, H. Respective roles of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family members in pancreatic stellate cell activation induced by transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Xu, X.F.; Xin, J.Q.; Fan, J.W.; Wei, Y.Y.; Peng, Q.X.; Duan, L.F.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. The effects of nuclear factor-kappa B in pancreatic stellate cells on inflammation and fibrosis of chronic pancreatitis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, R.P.; Dudeja, V.; Dawra, R.K.; Saluja, A.K. Cerulein-induced chronic pancreatitis does not require intra-acinar activation of trypsinogen in mice. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, I.; Zaheer, A.; Fisher, R.A. In vitro evidence for role of ERK, p38, and JNK in exocrine pancreatic cytokine production. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2006, 10, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Haynes, C.L. The role of p38 MAPK in neutrophil functions: Single cell chemotaxis and surface marker expression. Analyst 2013, 138, 6826–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asih, P.R.; Prikas, E.; Stefanoska, K.; Tan, A.R.P.; Ahel, H.I.; Ittner, A. Functions of p38 MAP kinases in the central nervous system. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 570586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Huang, W.; Liu, J.; Ding, L. Anemarsaponin B mitigates acute pancreatitis damage in mice through apoptosis reduction and MAPK pathway modulation. Biocell 2024, 48, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williard, D.E.; Twait, E.; Yuan, Z.; Carter, A.B.; Samuel, I. Nuclear factor kappa B–dependent gene transcription in cholecystokinin-and tumor necrosis factor-α–stimulated isolated acinar cells is regulated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Am. J. Surg. 2010, 200, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Wang, H.-Y.; Yang, X.-F.; Lin, Z.-Q.; Shi, N.; Chen, C.-J.; Yao, L.-B.; Yang, X.-M.; Guo, J.; Xia, Q. Alleviation of acute pancreatitis-associated lung injury by inhibiting the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mei, F.; Zhao, L.; Zuo, T.; Hong, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, J.; Wang, W. Inhibition of the p38 MAPK pathway attenuates renal injury in pregnant rats with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Immunol. Res. 2021, 69, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.F.; Nebreda, Á.R. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.-M.; Kudo, M.; Hagiwara, S.; Tabuchi, M.; Watanabe, T.; Munakata, H.; Sakurai, T. p38MAPK suppresses chronic pancreatitis by regulating HSP27 and BAD expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.P.; Zeng, J.H.; Lin, X.; Ni, Y.H.; Jiang, C.S. Puerarin ameliorates caerulein-induced chronic pancreatitis via inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 686992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.-T.; Liu, G.; Jiang, C.-S.; Ni, Y.-H.; Zeng, J.-H.; Lin, X.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Li, D.-Z.; Wang, W.; et al. COMP promotes pancreatic fibrosis by activating pancreatic stellate cells through CD36-ERK/AKT signaling pathways. Cell. Signal. 2024, 118, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.M. An overview of microRNAs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 87, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Fu, Q.; Pan, Y.-F.; Liu, C.-J.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Hu, M.-X.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, H.-W. Expressions of miR-22 and miR-135a in acute pancreatitis. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2014, 34, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Huang, L.; Zhu, S.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Yu, C.; Yu, X. Regulation of autophagy by systemic admission of microRNA-141 to target HMGB1 in l-arginine-induced acute pancreatitis in vivo. Pancreatology 2016, 16, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Conklin, D.J.; Li, F.; Dai, Z.; Hua, X.; Li, Y.; Xu-Monette, Z.Y.; Young, K.H.; Xiong, W.; Wysoczynski, M.; et al. The oncogenic microRNA miR-21 promotes regulated necrosis in mice. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Putta, S.; Wang, M.; Yuan, H.; Lanting, L.; Nair, I.; Gunn, A.; Nakagawa, Y.; Shimano, H.; Todorov, I.; et al. TGF-β activates Akt kinase through a microRNA-dependent amplifying circuit targeting PTEN. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ning, X.; Cui, W.; Bi, M.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-induced microRNA-216a promotes acute pancreatitis via Akt and TGF-β pathway in mice. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.-W.; Han, Y.; Wang, G.-P. miR-148a-3p exhaustion inhibits necrosis by regulating PTEN in acute pancreatitis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 5647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Ooi, L.L.P.J.; Hui, K.M. MicroRNA-216a/217-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition targets PTEN and SMAD7 to promote drug resistance and recurrence of liver cancer. Hepatology 2013, 58, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Liu, G.; Shi, N.; Tang, D.; Ferdek, P.E.; Jakubowska, M.A.; Liu, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yao, L.; et al. A microRNA checkpoint for Ca2+ signaling and overload in acute pancreatitis. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1754–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankisch, P.G.; Apte, M.; Banks, P.A. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet 2015, 386, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, B. Steroid receptor coactivator-interacting protein (sip) suppresses myocardial injury caused by acute pancreatitis. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Pan, L.; Yang, L.; Niu, Z.; Wang, L.; Feng, H.; Yuan, M. miR-29a-3p transferred by mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles protects against myocardial injury after severe acute pancreatitis. Life Sci. 2021, 272, 119189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Wang, R.-L.; Xie, H.; Jin, W.; Yu, K.-L. Overexpressed miRNA-155 dysregulates intestinal epithelial apical junctional complex in severe acute pancreatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 8282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Lu, J.; Jia, Y.; Bian, C.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Mei, W.; Cao, F.; Li, F. Identification of key microRNAs in exosomes derived from patients with the severe acute pancreatitis. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Luo, Y.; Okoye, C.S.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Xu, C.; Chen, H. Intestinal barrier damage, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and acute lung injury: A troublesome trio for acute pancreatitis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 132, 110770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Ge, P.; Lan, B.; Liu, J.; Wen, H.; Cao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yuan, H.; et al. Emodin ameliorates severe acute pancreatitis-associated acute lung injury in rats by modulating exosome-specific miRNA expression profiles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 6743–6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Guo, X.; Feng, B.; Guo, F. miR-141-Modified Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs) Inhibits the Progression of Severe Acute Pancreatitis. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 2023, 13, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masamune, A.; Watanabe, T.; Kikuta, K.; Shimosegawa, T. Roles of pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, S48–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Wan, R.; Hu, G.; Yang, L.; Xiong, J.; Wang, F.; Shen, J.; He, S.; Guo, X.; Ni, J.; et al. miR-15b and miR-16 induce the apoptosis of rat activated pancreatic stellate cells by targeting Bcl-2 in vitro. Pancreatology 2012, 12, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrier, A.; Chen, R.; Chen, L.; Kemper, S.; Hattori, T.; Takigawa, M.; Brigstock, D.R. Connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) and microRNA-21 are components of a positive feedback loop in pancreatic stellate cells (PSC) during chronic pancreatitis and are exported in PSC-derived exosomes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2014, 8, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.-X.; Zhang, H.-W.; Fu, Q.; Qin, T.; Liu, C.-J.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Tang, Q.; Chen, Y.-X. Functional role of MicroRNA-19b in acinar cell necrosis in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2016, 36, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xin, L.; Lin, J.-H.; Liao, Z.; Ji, J.-T.; Du, T.-T.; Jiang, F.; Li, Z.-S.; Hu, L.-H. Identifying miRNA-mRNA regulation network of chronic pancreatitis based on the significant functional expression. Medicine 2017, 96, e6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Jin, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Bai, Y. Association between microRNA polymorphisms and chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2016, 16, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Cane, M.C.; Mukherjee, R.; Szatmary, P.; Zhang, X.; Elliott, V.; Ouyang, Y.; Chvanov, M.; Latawiec, D.; Wen, L.; et al. Caffeine protects against experimental acute pancreatitis by inhibition of inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor-mediated Ca2+ release. Gut 2017, 66, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Hei, Z.; Li, S.; Song, H.; Huang, R.; Ji, X.; Zhang, F.; Shen, J.; Zhang, S.; Peng, S.; et al. Berberine inhibits intracellular Ca2+ signals in mouse pancreatic acinar cells through M3 muscarinic receptors: Novel target, mechanism, and implication. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 225, 116279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliem, C.; Merling, A.; Giaisi, M.; Köhler, R.; Krammer, P.H.; Li-Weber, M. Curcumin suppresses T cell activation by blocking Ca2+ mobilization and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 10200–10209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, S.; Cao, N.; Wu, W.; Liu, G.; Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Lu, D.; Zeng, L. Berberine is a Novel Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Inhibitor that Disrupts MCU-EMRE Assembly. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2412311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Gong, J.; Chen, Z. EGCG suppressed activation of hepatic stellate cells by regulating the PLCE1/IP3/Ca2+ pathway. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 3255–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyuva, Y.; Nazıroğlu, M. Resveratrol attenuates hypoxia-induced neuronal cell death, inflammation and mitochondrial oxidative stress by modulation of TRPM2 channel. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armağan, H.H.; Nazıroğlu, M. Curcumin attenuates hypoxia-Induced oxidative neurotoxicity, apoptosis, calcium, and zinc ion influxes in a neuronal cell line: Involvement of TRPM2 channel. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostál, Z.; Zholobenko, A.; Přichystalová, H.; Gottschalk, B.; Valentová, K.; Malli, R.; Modrianský, M. Quercetin protects cardiomyoblasts against hypertonic cytotoxicity by abolishing intracellular Ca2+ elevations and mitochondrial depolarisation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 222, 116094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Nie, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Cheng, J. Rhynchophylline regulates calcium homeostasis by antagonizing ryanodine receptor 2 phosphorylation to improve diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 882198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ling, D.; Wu, C.; Han, J.; Zhao, Y. Baicalin prevents the up-regulation of TRPV1 in dorsal root ganglion and attenuates chronic neuropathic pain. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 6, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.K.C.; Jeong, J.H.; Sharma, N.; Nguyen, Y.N.D.; Tran, H.-Y.P.; Dang, D.-K.; Park, J.H.; Byun, J.K.; Jin, D.; Xiaoyan, Z.; et al. Ginsenoside Re blocks Bay k-8644-induced neurotoxicity via attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction and PKCδ activation in the hippocampus of mice: Involvement of antioxidant potential. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 178, 113869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Sui, J.; Dong, X.; Jing, B.; Gao, Z. Wedelolactone alleviates acute pancreatitis and associated lung injury via GPX4 mediated suppression of pyroptosis and ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 173, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Jiang, W.; Ding, P.; Wang, W.; Zhao, K.; Chen, C. Neferine Ameliorates Severe Acute Pancreatitis-Associated Intestinal Injury by Promoting NRF2-mediated Ferroptosis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-kappaB in biology and targeted therapy: New insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Islam, A.U.; Prakash, H.; Singh, S. Phytochemicals targeting NF-kappaB signaling: Potential anti-cancer interventions. J. Pharm. Anal. 2022, 12, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaubitz, J.; Asgarbeik, S.; Lange, R.; Mazloum, H.; Elsheikh, H.; Weiss, F.U.; Sendler, M. Immune response mechanisms in acute and chronic pancreatitis: Strategies for therapeutic intervention. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1279539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.-H.; Xu, J.; Cai, H.-D.; Lv, Z.-W.; Feng, Y.-J.; Li, K.; Chen, C.-Q.; Li, Y.-Y. p38 MAPK inhibition alleviates experimental acute pancreatitis in mice. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2015, 14, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gu, T.; Wang, D. Inhibition of PAK1 alleviates cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis via p38 and NF-κB pathways. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20182221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Yi, Y.; Jiang, S.; Qi, X.; Wei, Z.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Galangin protects against acute pancreatitis by inhibiting ROS-induced acinar cell apoptosis and M1-type macrophage polarization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Basis Dis. 2025, 1871, 167887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Zang, X. Baicalin protects against acute pancreatitis involving JNK signaling pathway via regulating miR-15a. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2021, 49, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Hu, C.; Liu, C.; Yu, K.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Y. Dihydrokaempferol (DHK) ameliorates severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) via Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Life Sci. 2020, 261, 118340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovac, S.; Angelova, P.R.; Holmstrom, K.M.; Zhang, Y.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Abramov, A.Y. Nrf2 regulates ROS production by mitochondria and NADPH oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1850, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darakhshan, S.; Bidmeshki Pour, A.; Hosseinzadeh Colagar, A.; Sisakhtnezhad, S. Thymoquinone and its therapeutic potentials. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 95–96, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.F.; Pereira-Wilson, C.; Rattan, S.I. Curcumin induces heme oxygenase-1 in normal human skin fibroblasts through redox signaling: Relevance for anti-aging intervention. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.-Y.; Chuang, Y.-T.; Shiau, J.-P.; Yen, C.-Y.; Chang, F.-R.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Farooqi, A.A.; Chang, H.-W. Connection between Radiation-Regulating Functions of Natural Products and miRNAs Targeting Radiomodulation and Exosome Biogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Chang, P.-J.; Lin, S.-J.; Liaw, C.-C.; Shih, Y.-H.; Chen, L.-W.; Lin, C.-L. Curcumin Reinforces MiR-29a Expression, Reducing Mesangial Fibrosis in a Model of Diabetic Fibrotic Kidney via Modulation of CB1R Signaling. Processes 2021, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubrey, J.A.; Lertpiriyapong, K.; Steelman, L.S.; Abrams, S.L.; Yang, L.V.; Murata, R.M.; Rosalen, P.L.; Scalisi, A.; Neri, L.M.; Cocco, L.; et al. Effects of resveratrol, curcumin, berberine and other nutraceuticals on aging, cancer development, cancer stem cells and microRNAs. Aging 2017, 9, 1477–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, K.; Han, Y.; Ding, J.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Cao, F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in pancreatic acinar cells: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in acute pancreatitis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1503087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, R.; Hu, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2025, 24, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davi, F.; Iaconis, A.; Cordaro, M.; Di Paola, R.; Fusco, R. Nutraceutical Strategies for Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Foods 2025, 14, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wen, L.; Zhang, R.; Wei, Z.; Shi, N.; Xiong, Q.; Xia, Q.; Xing, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Niu, H.; et al. Dihydrodiosgenin protects against experimental acute pancreatitis and associated lung injury through mitochondrial protection and PI3Kγ/Akt inhibition. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1621–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, F.; Liu, T.; Zhang, K.; Wen, A.; Feng, L.; Shu, X.; Tian, S.; et al. Isorhamnetin alleviates mitochondrial injury in severe acute pancreatitis via modulation of KDM5B/HtrA2 signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Tang, T.; Wu, J.; Huang, F.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J. Rhizoma Alismatis Decoction improved mitochondrial dysfunction to alleviate SASP by enhancing autophagy flux and apoptosis in hyperlipidemia acute pancreatitis. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bu, C.; Wu, K.; Wang, R.; Wang, J. Curcumin protects the pancreas from acute pancreatitis via the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 3027–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Wang, K.; Yuan, C.; Xing, R.; Ni, J.; Hu, G.; Chen, F.; Wang, X. Luteolin protects mice from severe acute pancreatitis by exerting HO-1-mediated anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Wang, M.; Guo, X.; Qin, R. Curcumin Attenuates Inflammation in a Severe Acute Pancreatitis Animal Model by Regulating TRAF1/ASK1 Signaling. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 2280–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, L.I.; Balaban, D.V.; Dumbravă, B.F.; Păunescu, H.; Marin, R.-C.; Costescu, M.; Dima, L.; Jinga, M.; Coman, O.A. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Acute Pancreatitis: A Critical Review of Antioxidant Strategies. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Cai, B.; Liu, X.; Cai, H. Emodin attenuates calcium overload and endoplasmic reticulum stress in AR42J rat pancreatic acinar cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 9, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Deng, L.H.; Zhang, Z.D.; Yang, X.N.; Xia, Q.; Xiang, D.K.; Huang, L.; Wan, M.H. Effect of Chaiqinchengqi decoction on sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase mRNA expression of pancreatic tissues in acute pancreatitis rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 2343–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Huang, K.; Lin, H.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Jin, J. Mogroside IIE inhibits digestive enzymes via suppression of interleukin 9/interleukin 9 receptor signalling in acute pancreatitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xue, D.-B.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, W.-H.; Pan, S.-H.; Sun, B. Induction of apoptosis by artemisinin relieving the severity of inflammation in caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Choi, J.-W.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, D.-U.; Kweon, B.; Oh, H.; Kim, Y.-C.; Song, H.-J.; Bae, G.-S.; Park, S.-J. Betulinic acid ameliorates the severity of acute pancreatitis via inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriviriyakul, P.; Sriko, J.; Somanawat, K.; Chayanupatkul, M.; Klaikeaw, N.; Werawatganon, D. Genistein attenuated oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in L-arginine induced acute pancreatitis in mice. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansod, S.; Godugu, C. Nimbolide ameliorates pancreatic inflammation and apoptosis by modulating NF-κB/SIRT1 and apoptosis signaling in acute pancreatitis model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 90, 107246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmageed, M.E.; Nader, M.A.; Zaghloul, M.S. Targeting HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway by protocatechuic acid protects against l-arginine induced acute pancreatitis and multiple organs injury in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 906, 174279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.-T.; Yin, G.-J.; Xiao, W.-Q.; Qiu, L.; Yu, G.; Hu, Y.-L.; Xing, M.; Wu, D.-Q.; Cang, X.-F.; Wan, R.; et al. Rosmarinic acid attenuates sodium taurocholate-induced acute pancreatitis in rats by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB activation. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2015, 43, 1117–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy-Pénzes, M.; Hajnády, Z.; Regdon, Z.; Demény, M.Á.; Kovács, K.; El-Hamoly, T.; Maléth, J.; Hegyi, P.; Hegedűs, C.; Virág, L. Tricetin reduces inflammation and acinar cell injury in Cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis: The role of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage signaling. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Yuan, F.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Fan, T.; Wang, F. Calycosin alleviates cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis by inhibiting the inflammatory response and oxidative stress via the p38 MAPK and NF-κB signal pathways in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 105, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Ma, J.; Meng, W.; Wang, N. Dihydromyricetin inhibits caerulin-induced TRAF3-p38 signaling activation and acute pancreatitis response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 1696–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Asikaer, A.; Chen, Q.; Wang, F.; Lan, J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhao, H.; Duan, H. Network pharmacology and in vitro experimental verification unveil glycyrrhizin from glycyrrhiza glabra alleviates acute pancreatitis via modulation of MAPK and STAT3 signaling pathways. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.I.; Malleo, G.; Genovese, T.; Mazzon, E.; Di Paola, R.; Crisafulli, C.; Caminiti, R.; Siriwardena, A.K.; Cuzzocrea, S. Green tea polyphenols ameliorate pancreatic injury in cerulein-induced murine acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 2009, 38, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Cao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Cui, M.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, G. Ligustrazine alleviates acute pancreatitis by accelerating acinar cell apoptosis at early phase via the suppression of p38 and Erk MAPK pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 82, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Wen, A.; Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Wan, C.; Cao, Y.; Xin, G.; Huang, W. Elucidating the mechanism of stigmasterol in acute pancreatitis treatment: Insights from network pharmacology and in vitro/in vivo experiments. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1485915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tang, X.; Ke, X.; Dai, Y.; Shi, J. Triptolide suppresses NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses and activates expression of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant genes to alleviate caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasiuk, A.; Bulak, K.; Talar, M.; Fichna, J. Chlorogenic acid reduces inflammation in murine model of acute pancreatitis. Pharmacol. Rep. 2021, 73, 1448–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiruveedi, V.L.; Bale, S.; Khurana, A.; Godugu, C. Withaferin A, a novel compound of Indian ginseng (Withania somnifera), ameliorates C erulein-induced acute pancreatitis: Possible role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2586–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, D.; Jin, T.; Zhang, R.; Hu, L.; Xing, Z.; Shi, N.; Shen, Y.; Gong, M. Phenolic compounds isolated from Dioscorea zingiberensis protect against pancreatic acinar cells necrosis induced by sodium taurocholate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1467–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, C.-H.; Liu, M.-W. Protective effects of baicalin on caerulein-induced AR42J pancreatic acinar cells by attenuating oxidative stress through miR-136-5p downregulation. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211026118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, Q.; Chen, X.; Sha, H.; Ma, Z. Effects of resveratrol on calcium regulation in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 580, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, F.; Luo, W.-S.; Zhu, M.-F.; Zhao, N.-J.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Chen, Y.-F.; Feng, D.-X.; Yang, S.-Y.; Sun, W.-J. Therapeutic potential of Da Cheng Qi Decoction and its ingredients in regulating ferroptosis via the NOX2-GPX4 signaling pathway to alleviate and predict severe acute pancreatitis. Cell. Signal. 2025, 131, 111733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-B.; Bae, G.-S.; Jo, I.-J.; Song, H.-J.; Park, S.-J. Effects of berberine on acute necrotizing pancreatitis and associated lung injury. Pancreas 2017, 46, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Tang, J.; Man, X.; Liu, F. Colchicine improves severe acute pancreatitis-induced acute lung injury by suppressing inflammation, apoptosis and oxidative stress in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, X.-H.; Song, Z.; Li, M.-L.; Wu, X.-W.; Guo, M.-X.; Zhang, X.-H.; Zou, X.-P. Isoacteoside attenuates acute kidney injury induced by severe acute pancreatitis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zeng, X.; Sun, D.; Qi, X.; Li, D.; Wang, W.; Lin, Y. Albiflorin Alleviates Severe Acute Pancreatitis-Associated Liver Injury by Inactivating P38MAPK/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 4987–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, H.; Huang, C.; Fan, J.; Mei, Q.; Lu, Y.; Lou, L.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Y. Quercetin protects against intestinal barrier disruption and inflammation in acute necrotizing pancreatitis through TLR4/MyD88/p38 MAPK and ERS inhibition. Pancreatology 2018, 18, 742–752. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, E.; Cao, Y.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; You, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; He, J.; Feng, Y. The mitochondria-targeted Kaempferol nanoparticle ameliorates severe acute pancreatitis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Qian, J.; Meng, Y.; Wang, P.; Cheng, R.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, S.; Liu, C. Salidroside alleviates severe acute pancreatitis-triggered pancreatic injury and inflammation by regulating miR-217-5p/YAF2 axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, B.; Kim, D.-U.; Oh, J.-Y.; Park, S.-J.; Bae, G.-S. Catechin hydrate ameliorates cerulein-induced chronic pancreatitis via the inactivation of TGF-β/Smad2 signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 28, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Tang, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, D.; Wang, M.; Cai, J.; Liu, W.; Nie, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X. Psidium guajava flavonoids prevent NLRP3 inflammasome activation and alleviate the pancreatic fibrosis in a chronic pancreatitis mouse model. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2021, 49, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Hu, S. Efficacy of integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine in managing mild-moderate acute pancreatitis: A real-world clinical perspective analysis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1429546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Zaeri, F.; Zamani, M.; Hekmatdoost, A. Nano-curcumin supplementation in patients with mild and moderate acute pancreatitis: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 5279–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.X.; Lu, X.G.; Zhan, L.B.; Song, Y. Chinese herbal medicine therapy for hyperlipidemic acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 2256–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, J.; Jin, T.; Lin, Z.; Zhu, P.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Sun, X.; Du, D.; et al. AGI grade-guided chaiqin chengqi decoction treatment for predicted moderately severe and severe acute pancreatitis (CAP trial): Study protocol of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, pragmatic clinical trial. Trials 2022, 23, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]