Blueberries and Honeysuckle Berries: Anthocyanin-Rich Polyphenols for Vascular Endothelial Health and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- (1)

- Phytochemical composition studies characterizing the bioactive profile of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) or haskap/blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.), with an emphasis on anthocyanins, other (poly)phenols, and secondary metabolites relevant to vascular health.

- (2)

- In vitro or in vivo preclinical studies investigating mechanistic effects of blueberries, haskap, or their isolated (poly)phenolic constituents on endothelial function, vascular signaling pathways, oxidative stress, inflammation, platelet function, lipid handling, or related cardiometabolic endpoints.

- (3)

- Human observational studies or intervention trials (acute or chronic) assessing vascular, hemodynamic, or cardiometabolic outcomes after intake of blueberries, haskap, or their extracts, including outcomes such as flow-mediated dilation (FMD), arterial stiffness, pulse wave velocity, blood pressure, biomarkers of endothelial activation, or composite cardiovascular risk markers.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Approach to Evidence Synthesis

3. Bioactive Principles Composition of Honeysuckle Berries/Haskap (Lonicera caerulea L.)

3.1. General Phytochemical Profile

3.2. Anthocyanins as Key Bioactive Compounds

3.3. Other Polyphenols and Secondary Phytochemicals

3.4. Factors Influencing Bioactive Content

3.5. Bioavailability and Circulating Metabolites

4. Bioactive Principles Composition of Honeysuckle Berries/Haskap (Lonicera caerulea L.)

4.1. General Phytochemical Profile

4.2. Anthocyanins as Key Bioactive Compounds

4.3. Other Polyphenols and Secondary Phytochemicals

4.4. Factors Influencing Bioactive Compounds Content

4.5. Bioavailability and Circulating Metabolites

4.6. Comparative Phytochemistry

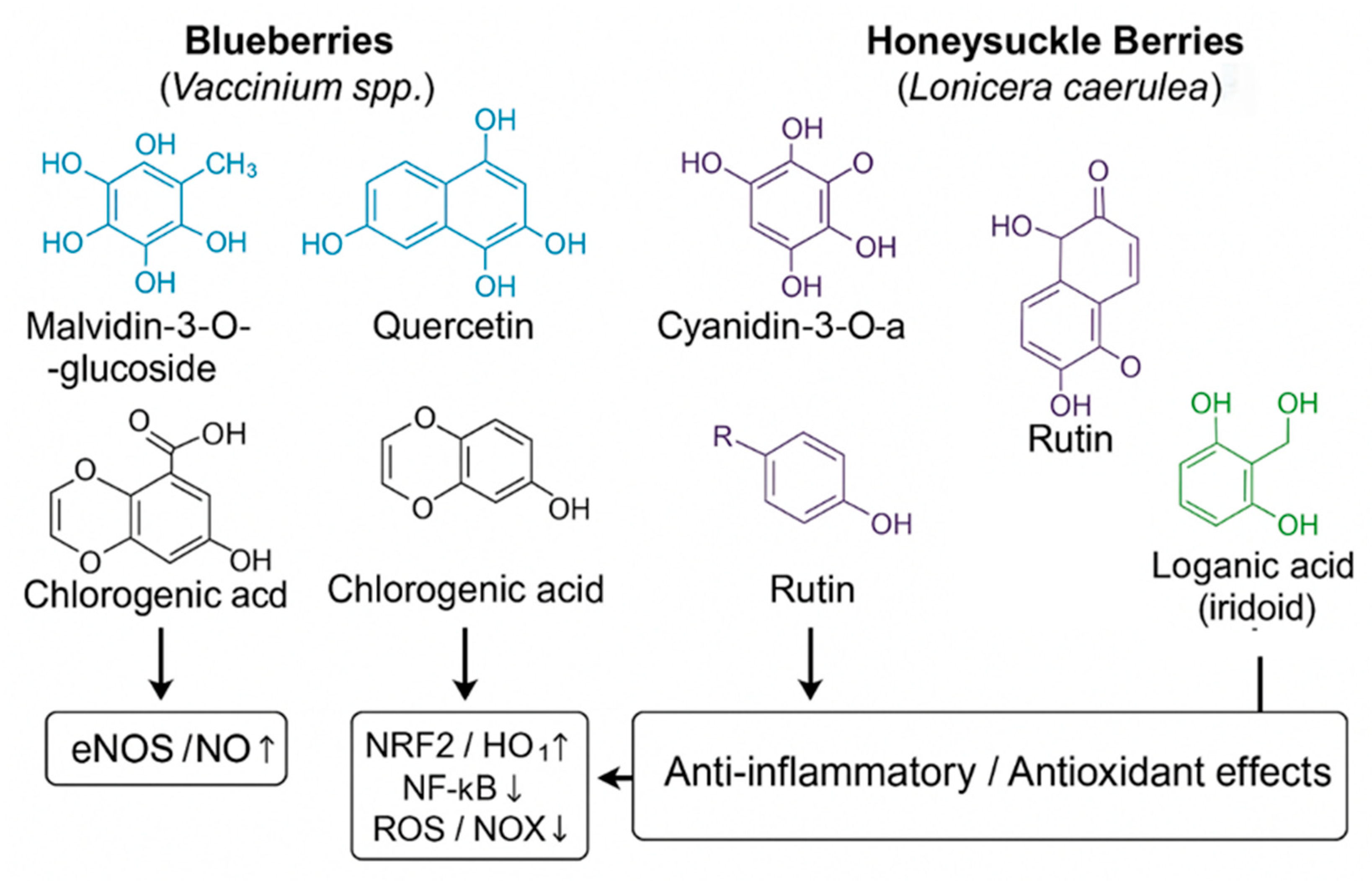

4.7. Mechanistic Complementarity Between Blueberries and Haskap Berries

5. Molecular Mechanisms

5.1. NO/eNOS-Mediated Vasodilation

5.2. NRF2-Dependent Antioxidant Defense

5.3. NF-κB and Inflammatory Signaling

5.4. Lipoprotein Oxidation and Platelet Function

5.5. Metabolic and Gut–Microbiota-Mediated Mechanisms

6. Preclinical Evidence

7. Clinical Evidence

Safety, Tolerability and Potential Interactions

8. Synergy Between Blueberries and Honeysuckle Berries

8.1. Mechanistic Complementarity in Phytochemical Profiles

8.2. A Hypothesis for Additive and Synergistic Vascular Effects

8.3. Roadmap for Mechanism-Aware Clinical Trials

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Allen, N.B.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Bansal, N.; Beaton, A.Z.; et al. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 151, e41–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics Date—At-a-Glance. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/-/media/PHD-Files-2/Science-News/2/2025-Heart-and-Stroke-Stat-Update/2025-Statistics-At-A-Glance.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Jurja, S.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Vasile, M.; Hincu, M.M.; Coviltir, V.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.S. Xanthophyll pigments dietary supplements administration and retinal health in the context of increasing life expectancy trend. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1226686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Popescu, A.; Bratu, M.M.; Udrea, M.; Busuricu, F. Comparative Antioxidant Properties of some Romanian Foods Fruits Extracts. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2014, 15, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Pober, J.S.; Sessa, W.C. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davignon, J.; Ganz, P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation 2004, 109, III27–III32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopych, V.; Da Costa, A.D.S.; Park, K. Endothelial Dysfunction in Atherosclerosis: Experimental Models and Therapeutics. Biomater. Res. 2025, 29, 0252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalba, G.; San José, G.; Moreno, M.U.; Fortuño, M.A.; Fortuño, A.; Beaumont, F.J.; Díez, J. Oxidative stress in arterial hypertension: Role of NAD(P)H oxidase. Hypertension 2001, 38, 1395–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, N.; Baldassarre, M.P.A.; Cichelli, A.; Pandolfi, A.; Formoso, G.; Pipino, C. Role of Polyphenols and Carotenoids in Endothelial Dysfunction: An Overview from Classic to Innovative Biomarkers. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 6381380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serino, A.; Salazar, G. Protective role of polyphenols against vascular inflammation, aging and cardiovascular disease. Nutrients 2018, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.; Marino, M.; Angelino, D.; Del Bo’, C.; Del Rio, D.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M. Role of berries in vascular function: A systematic review of human intervention studies. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, M.; Yang, J. Molecular mechanism and health role of functional ingredients in blueberry for chronic disease in human beings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different types of berries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24673–24706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martau, G.A.; Bernadette-Emoke, T.; Odocheanu, R.; Soporan, D.A.; Bochis, M.; Simon, E.; Vodnar, D.C. Vaccinium species (Ericaceae): Phytochemistry and biological properties of medicinal plants. Molecules 2023, 28, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Łysiak, G. Bioactive compounds of blueberries: Post-harvest factors influencing the nutritional value of prod-ucts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18642–18663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Lei, Y.; Zhou, R.; Ruan, T.; Lu, W.; Ying, J.; Yue, Y.; Mu, D. Effect of blueberry intervention on endothelial function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1368892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, A.; Mukamal, K.J.; Liu, L.; Franz, M.; Eliassen, A.H.; Rimm, E.B. High anthocyanin intake is associated with a reduced risk of myocardial infarction in young and middle-aged women. Circulation 2013, 127, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, A.; Bertoia, M.; Chiuve, S.; Flint, A.; Forman, J.; Rimm, E.B. Habitual intake of anthocyanins and flavanones and risk of cardiovascular disease in men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D.; Marino, M.; Venturi, S.; Tucci, M.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Del Bo’, C. Blueberries and their bioactives in the modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation an cardio/vascular function markers: A systematic review of human intervention studies. J. NutBiochem. 2023, 111, 109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent research on the health benefits of blueberries and their anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrame, S.; Adekeye, T.E.; Klimis-Zacas, D. The Role of Berry Consumption on Blood Pressure Regulation and Hyperension: An Overview of the Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, R.S.; Mu, S.; Feresin, R.G. Blueberry polyphenols increase nitric oxide and attenuate angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling in human aortic endothelial cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yan, Z.; Li, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sui, Z. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of blueberry anthocyanins on high glucose-induced human retinal capillary endothelial cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1862462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-Y.; Liu, Y.-M.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.-N.; Li, C.-Y. Anti-inflammatory effect of the blueberry anthocyanins malvidin-3-glucoside and malvidin-3-galactoside in endothelial cells. Molecules 2014, 19, 12827–12841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hutabarat, R.P.; Chai, Z.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, W.; Li, D. Antioxidant blueberry anthocyanins induce vasodilation via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in high-glucose-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Bartosz, G. Antioxidant activity of anthocyanins and anthocyanidins: A critical review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Yan, X.; Jin, T.; Ling, W. Protocatechuic acid, a metabolite of anthocyanins inhibits monocyte adhesion and reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 12722–12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Du, B.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, F. An Insight into Anti-Inflammatory Activities an Inflammation Related Diseases of Anthocyanins: A Review of Both In Vivo and In Vitro Investigations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.C.; Nunes, A.R.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G.; Silva, L.R. Dietary Effects of Anthocyanins in Human Health: A Com-prehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, R.; Xia, M. Anthocyanin supplementation improves HDL-associated paraoxonase 1 activity and enhances cholesterol efflux capacity in subjects with hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, J.; Zhang, H.; Pang, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Anthocyanin supplementation at different doses improves cholesterol efflux capacity in subjects with dyslipidemia—A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lan, W.; Chen, D. Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) anthocyanins and their functions, stability, bioavailability, and ap-plications. Foods 2024, 13, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, E.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Pasten, A.; Ah-Hen, K.S.; Mejías, N.; Sepúlveda, L.; Poblete, J.; Gómez-Pérez, L.S. Drying: A practical technology for blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.)—Processes and their effects on selected health-promoting properties. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LLin, Y.; Li, C.; Shi, L.; Wang, L. Anthocyanins: Modified new technologies and challenges. Foods 2023, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, M.E.; Aaby, K.; Budic-Leto, I.; Brncic´, S.R.; El, S.N.; Karakaya, S.; Simsek, S.; Manach, C.; Wiczkowski, W.; Pascual-Teresa, S. A review of factors affecting anthocyanin bioavailability Possible implications for the inter-individual variability. Foods 2019, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lila, M.A.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Grace, M.; Kalt, W. Unraveling anthocyanin bioavailability for human health. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhie, T.K.; Walton, M.C. The bioavailability and absorption of anthocyanins: Wards better understanding. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Murillo, S.S.; Sánchez-Bodón, J.; Hernández Olmos, S.L.; Ibarra-Vázquez, M.F.; Guerrero-Ramírez, L.G.; Pérez-Álvarez, L.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L. Anthocyanin-Loaded Polymers as Promising Nature-Based, Responsive, and Bioactive Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Xie, K.; Liao, X.; Tan, J. Factors affecting the stability of anthocyanins and strategies for improving their stability: A review. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X. Intermolecular copigmentation of anthocyanins with phenolic compounds improves color stability in the model and real blueberry fermented beverage. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashwan, A.K.; Karim, N.; Xu, Y.; Xie, J.; Cui, H.; Mozafari, M.R. Potential micro-/nano-encapsulation systems for improving stability and bioavailability of anthocyanins: An updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 3931–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Busuricu, F.; Jurja, S.; Craciunescu, O.; Oprea, O.; Motelica, L.; Oprita, E.I.; Roncea, F.N. The Role of Antioxidant Plant Extracts’ Composition and Encapsulation in Dietary Supplements and Gemmo-Derivatives, as Safe Adjuvants in Metabolic and Age-Related Conditions: A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šenica, M.; Stampar, F.; Sladonja, B.; Poljuha, D.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. The impact of drying on bioactive compounds of blue honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea var. edulis Turcz. ex Herder). Acta Bot. Croat. 2020, 79, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio-Mendoza, J.A.; Pokorski, P.; Aktas¸, H.; Napiórkowska, A.; Kurek, M.A. Advances in Chromatographic Analysis of Phenolic Phytochemicals in Foods: Bridging Gaps and Exploring New Horizons. Foods 2024, 13, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, E.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Ghanem, N.; Vázquez, A.R.; Johnson, S.A. Protective effects of blueberries on vascular function: A narrative review of preclinical and clinical evidence. Nutr. Res. 2023, 120, 20–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuh, J.; Dawkins, N.; Aluko, R. Cardiovascular disease protective properties of blueberry polyphenols (Vaccinium corymbosum): A concise review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2023, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Debnath, S.C.; Igamberdiev, A.U. Effects of Vaccinium-derived antioxidants on human health: The past, present and future. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1520661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stull, A.J.; Cassidy, A.; Djoussé, L.; Johnson, S.A.; Krikorian, R.; Lampe, J.W.; Mukamal, K.J.; Nieman, D.C.; Starr, K.N.P.; Rasmussen, H.; et al. The state of the science on the health benefits of blueberries: A perspective. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1415737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.Y.; Zhang, H.C.; Liu, W.X.; Li, C.Y. Survey of antioxidant capacity and phenolic composition of blueberry, blackberry, and strawberry in Nanjing. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2012, 13, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Mitra, S.; Hafiz Muhammad, R.; Debnath, B.; Lu, X.; Jian, H.; Qiu, D. Comparative phytochemical profiles and antioxidant enzyme activity analyses of the southern highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) at different developmental stages. Molecules 2018, 23, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Herrera-Balandrano, D.; Yu, H.; Beta, T.; Zeng, X.; Tian, L.; Niu, L.; Huang, W.-Y. A comparative analysis on the an-thocyanin composition of 74 blueberries Cultivars from China. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 102, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimando, A.M.; Kalt, W.; Magee, J.B.; Dewey, J.; Ballington, J.R. Resveratrol, pterostilbene, piceatannol in Vaccinium berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4713–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ye, Z.; Yang, W.; Xu, Y.J.; Tan, C.P.; Liu, Y. Blueberry Anthocyanins from Commercial Products: Structure Identification and Potential for Diabetic Retinopathy Amelioration. Molecules 2022, 27, 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gallegos, J.L.; Haskell-Ramsay, C.; Lodge, J.K. Effects of blueberry consumption on cardiovascular health in healthy adults: A cross-over randomised controlled trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, P.J.; van der Velpen, V.; Berends, L.; Jennings, A.; Feelisch, M.; Umpleby, M.A.; Evans, M.; Fernandez, B.O.; Meiss, M.S.; Minnion, M.; et al. Blueberries improve biomarkers of cardiometabolic function in participants with metabolic syndrome—Results from a 6-month, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bo, C.; Tucci, M.; Martini, D.; Marino, M.; Bertoli, S.; Battezzati, A.; Porrini, M.; Riso, P. Acute effect of blueberry intake on vascular function in older subjects: Study protocol for a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, A.J.; Cash, K.C.; Johnson, W.D.; Champagne, C.M.; Cefalu, W.T. Bioactives in blueberries improve insulin sensitivity in obese, insulin-resistant men and women. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1764–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, A.J.; Cash, K.C.; Champagne, C.M.; Gupta, A.K.; Boston, R.; Beyl, R.A.; Johnson, W.D.; Cefalu, W.T. Blueberries improve endothelial function, but not blood pressure, in adults with metabolic syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4107–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.; Hein, S.; Mesnage, R.; Fernandes, F.; Abhayaratne, N.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bell, L.; Rodrigues-Mateos, A. Wild blueberry (poly)phenols can improve vascular function and cognitive performance in healthy older individuals: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Rendeiro, C.; Bergillos-Meca, T.; Tabatabaee, S.; George, T.W.; Heiss, C.; Spencer, J.P.E. Intake and time dependence of blueberry flavonoid-induced improvements in vascular function. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Du, M.; Leyva, M.J.; Sanchez, K.; Betts, N.M.; Wu, M.; Aston, C.E.; Lyons, T.J. Blueberries decrease cardiovascular risk factors in obese men and women with metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Figueroa, A.; Navaei, N.; Wong, A.; Kalfon, R.; Ormsbee, L.T.; Hooshmand, S.; Payton, M.E.; Arjmandi, B.H. Daily blueberry consumption improves blood pressure and arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with pre- and stage 1-hypertension: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołba, M.; Sokół-Łetowska, A.; Kucharska, A.Z. Health properties and composition of honeysuckle berry Lonicera caerulea L.: An update on recent studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsavová, J.; Sytarová, I.; Mlcek, J.; Mišurcová, L. Phenolic compounds, vitamins C and E and antioxidant activity of edible honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea L. var. kamtschatica Pojark) in relation to their origin. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurikova, T.; Rop, O.; Mlcek, J.; Sochor, J.; Balla, S.; Szekeres, L.; Hegedusova, A.; Hubalek, J.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R. Phenolic pro-file of edible honeysuckle berries (genus Lonicera) and their biological effects. Molecules 2011, 17, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudone, L.; Liaudanskas, M.; Vilkickyte, G.; Kviklys, D.; Žvikas, V.; Viškelis, J.; Viškelis, P. Phenolic profiles, antioxidant activity and phenotypic characterization of Lonicera caerulea L. berries, cultivated in Lithuania. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarcova, I.; Heinrich, J.; Valentova, K. Berry fruits as a source of biologically active compounds: The case of Lonicera caerulea. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2007, 151, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, L.; Lombrea, A.; Batrina, S.L.; Buda, V.O.; Esanu, O.-M.; Pasca, O.; Dehelean, C.A.; Dinu, S.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Danciu, C. A Systematic Review of Cardio-Metabolic Properties of Lonicera caerulea L. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Qiao, J.; Mikhailovich, M.S.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Ji, X.; She, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, J. Comprehensive structural analysis of anthocyanins in blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.), bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum L.), cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.), and antioxidant capacity comparison. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Oszmiański, J.; Piórecki, N.; Fecka, I. Iridoids, phenoliccompounds and antioxidant activity of edible honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea var. kamtschatica Sevast.). Molecules 2017, 22, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Qiao, J.; Gong, C.; Wei, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Qin, D.; Huo, J. C3G quantified method verification and quantified in blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) using HPLC-DAD. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, N.; Pluta, S.; Seliga, Ł.; Lachowicz-Wisniewska, S.; Kapusta, I.T. Comparative evaluation of the phytochemical composition of fruits of ten haskap berry (Lonicera caerulea var. kamtschatica Sevast.) cultivars grown in Poland. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, X.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, A.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D.; Sui, X.; Huo, J.; Zhang, Y. Polyphenols in twenty cultivars of blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.): Profiling, antioxidant capacity, and α-amylase inhibitory activity. Food Chem. 2023, 421, 136148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciunescu, O.; Seciu-Grama, A.-M.; Mihai, E.; Utoiu, E.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Lupu, C.E.; Artem, V.; Ranca, A.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S. The chemical profile, antioxidant, and anti-lipid droplet activity of fluid extracts from Romanian cultivars of haskap berries, bitter cherries, and red grape pomace for the management of liver steatosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Gao, R.; Wang, Y.; An, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wan, H.; Wei, D.; Wang, F.; et al. Lonicera caerulea genome reveals molecular mechanisms of freezing tolerance and anthocyanin biosynthesis. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 76, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszkiewicz, M.; Sokół-Łetowska, A.; Pałczynska, A.; Kucharska, A.Z. Fruit smoothies enriched in a honeysuckle berry extract—An innovative product with health-promoting properties. Foods 2023, 12, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, N.; Pluta, S.; Świeca, M.; Potocki, L.; Seliga, Ł.; Kapusta, I. Bioactive compounds and in vitro health-promoting activity of the fruit skin and flesh of different haskap berry (Lonicera caerulea var. kamtschatica Sevast.) cultivars. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.; Boehm, M.M.; Sekhon-Loodu, S.; Parmar, I.; Bors, B.; Jamieson, A.R. Anti-inflammatory activity of haskap cultivars is polyphenols-dependent. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1079–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayar, E.; Cebová, M.; Lietava, J.; Panghyova, E.; Pechanova, O. Antioxidant effect of Lonicera caerulea L. in the cardiovascular system of obese Zucker rats. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, F.; Xu, W.; Ma, Q.; Hu, J. The therapeutic potential of honeysuckle in cardiovascular disease: An anti-inflammatory intervention strategy. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 7262–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Williams, C.M. A pilot dose-response study of the acute effects of haskap berry extract (Lonicera caerulea L.) on cog-nition, mood, and blood pressure in older adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 3325–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howatson, G.; Snaith, G.C.; Kimble, R.; Cowper, G.; Keane, K.M. Improved Endurance Running Performance Following Haskap Berry (Lonicera caerulea L.) Ingestion. Nutrients 2022, 14, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Arumuggam, N.; Amararathna, M.; Silva, A.B.K.H. The potential health benefits of haskap (Lonicera caerulea L.): Role of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 44, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Investigating the Effects of a Haskap Berry Supplement on Neurological and Cardiovascular Biomarkers in Adults 50+ (NCT07119788). ClinicalTrials. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT07119788 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Yousaf, M.; Razmovski-Naumovski, V.; Zubair, M.; Chang, D.; Zhou, X. Synergistic Effects of Natural Product Combinations in Protecting the Endothelium Against Cardiovascular Risk Factors. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2022, 27, 2515690X221113327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C.; Talalay, P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: The combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1984, 22, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou–Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czank, C.; Cassidy, A.; Zhang, Q.; Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T.; Kroon, P.A.; Botting, N.P.; Kay, C.D. Human metabolism and elimination of the anthocyanin, cyanidin-3-glucoside: A (13)C-tracer study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaglione, P.; Donnarumma, G.; Napolitano, A.; Galvano, F.; Gallo, A.; Scalfi, L.; Fogliano, V. Protocatechuic acid is the major human metabolite of cyanidin-glucosides. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2043–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Li, Y.; Hou, D.X.; Wu, S. The Effects and Mechanisms of Cyanidin-3-Glucoside and Its Phenolic Metabolites in Maintaining Intestinal Integrity. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Mesnage, R.; Tuohy, K.; Heiss, C.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. (Poly)phenol-related gut metabo-types and human health: An update. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, J.; Hussain, A.; Al-Hareth, Z.; Singh, H.; Da Boit, M. Anthocyanins and vascular health: A matter of metabolites. Foods 2023, 12, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, E.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Craciunescu, O.; Ciucan, T.; Iosageanu, A.; Seciu-Grama, A.-M.; Prelipcean, A.-M.; Utoiu, E.; Coroiu, V.; Ghenea, A.-M.; et al. In vitro hypoglycemic potential, antioxidant and prebiotic activity after simulated digestion of combined blueberry pomace and chia seed extracts. Processes 2023, 11, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, S.; Rendine, M.; Marino, M.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Riso, P.; Del Bo’, C. Differential effects of wild blueberry (poly)phenol metabolites in modulating lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in 782 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlund, I.; Koli, R.; Alfthan, G.; Marniemi, J.; Puukka, P.; Mustonen, P.; Mattila, P.; Jula, A. Favorable effects of berry consumption on platelet function, blood pressure, and HDL cholesterol. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.; Hosking, H.; Pederick, W.; Singh, I.; Santhakumar, A.B. The effect of anthocyanin supplementation in modu-lating platelet function in a sedentary population: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Li, K.; Fan, D.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, X.; Ma, X.; Xu, L.; Shi, Y.; Ya, F.; Zou, J.; et al. Dose-dependent effects of anthocyanin supplementation oplatelet function in subjects with dyslipidemia: A randomized clinical trial. EBioMedicine 2021, 70, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Popoviciu, D.R.; Artem, V.; Ranca, A.; Craciunescu, O.; Prelipcean, A.-M.; Motelica, L.; Vasile, M. Preliminary data regarding bioactive compounds and total antioxidant capacity of some fluid extracts of Lonicera caerulea L. berries. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. B Chem. Mater. Sci. 2023, 85, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Oprea, O.C.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Roncea, F.N.; Prelipcean, A.-M.; Craciunescu, O.; Iosageanu, A.; Artem, V.; Ranca, A.; Motelica, L.; et al. Health benefits of antioxidant bioactive compounds in the fruits and leaves of Lonicera caerulea L. and Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.) Elliot. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, A.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Yao, Y.; Guo, J. Understanding the effect of anthocyanin extracted from Lonicera caerulea L. on alcoholic hepatosteatosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Yoo, J.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, H.J. Lonicera caerulea extract attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in free fatty acid-induced HepG2 hepatocytes and in high-fat diet-fed mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Park, E.J.; Lee, H.J. Honeysuckle berry (Lonicera caerulea L.) inhibits lipase activity and modulates the gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed mice. Molecules 2022, 27, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.F.; Wu, C.Y.; Lin, C.F.; Liu, Y.W.; Lin, T.C.; Liao, H.J.; Chang, G.R. The anticancer effect of cyanidin 3-O-glucoside combined with 5-fluorouracil on lung large-cell carcinoma in nude mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, R.Y.; Brooks, M.-S.L.; Ghanem, A. Phenolic analyses of haskap berries (Lonicera caerulea L.): Spectrophotometry versus high-performance liquid chromatography. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 1708–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumny, D.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Czajor, K.; Bernacka, K.; Ziółkowska, S.; Krzyżanowska-Berkowska, P.; Magdalan, J.; Misiuk-Hojło, M.; Sozański, T.; Szeląg, A. Extract from Aronia melanocarpa, Lonicera caerulea, and Vaccinium myrtillus improves near visual acuity in people with presbyopia. Nutrients 2024, 16, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, E.; Jiang, Y.; Clemens, A.; Crossman, T.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Impact of thermal degradation of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside of haskap berry on cytotoxicity of hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 and breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alami, M.; Benchagra, L.; Ramchoun, M.; Khalil, A.; Berrougui, H. Antiatherogenic effect of blueberry fruit polyphenols extracts (Vaccinium angustifolium Ait) reduces oxidative stress and enhances the cholesterol efflux process. Atherosclerosis 2023, 379, S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.A.; Navarro-Nuñez, L.; Lozano, M.L.; Martínez, C.; Vicente, V.; Gibbins, J.M.; Rivera, J. Flavonoids inhibit the platelet TxA2_22 signalling pathway and antagonize TxA2_22 receptors (TP) in platelets and smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 64, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.C.; Hong, Q.; Wang, Y.G.; Tan, H.L.; Xiao, C.R.; Liang, Q.D.; Cai, S.H.; Gao, Y. Ferulic acid attenuates adhesion molecule expression in gamma-radiated human umbilical vascular endothelial cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Yang, Q.; Ma, W.; Li, J.; Qu, L.; Wang, M. Protocatechuic Acid Ameliorated Palmitic-Acid-Induced Oxidative Damage in Endothelial Cells through Activating Endogenous Antioxidant Enzymesvia an Adenosine-Monophosphate-Activated-Protein-Kinase-Dependent Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 10400–10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, M. Protocatechuic Acid-Ameliorated Endothelial Oxidative Stress through Regulating Acetylation Level via CD36/AMPK Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7060–7072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhao, R.; Shen, G.X. Impact of cyanidin-3-glucoside on glycated LDL-induced NADPH oxidase activation, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell viability in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 15867–15880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alul, R.H.; Wood, M.; Longo, J.; Marcotte, A.L.; Campione, A.L.; Moore, M.K.; Lynch, S.M. Vitamin C protects low-density lipoprotein from homocysteine-mediated oxidation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retsky, K.L.; Freeman, M.W.; Frei, B. Ascorbic acid oxidation product(s) protect human low density lipoprotein against atherogenic modification: Anti- rather than prooxidant activity of vitamin C in the presence of transition metal ions. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.J.; Endale, M.; Park, S.C.; Cho, J.Y.; Rhee, M.H. Dual Roles of Quercetin in Platelets: Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase and MAP Kinases Inhibition, and cAMP-Dependent Vasodilator-Stimulated Phosphoprotein Stimulation. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 485262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Adili, R.; McKeown, T.; Chen, P.; Zhu, G.; Li, D.; Ling, W.; Ni, H.; Yang, Y. Plant-based food cyanidin-3-glucoside modulates human platelet glycoprotein VI signaling and inhibits platelet activation and thrombus formation. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simu, S.Y.; Alam, M.B.; Kim, S.Y. The Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 by 8-Epi-7-deoxyloganic Acid Attenuates Inflammatory Symptoms through the Suppression of the MAPK/NF-κB Signaling Cascade in In Vitro and In Vivo Models. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.W.; Ikeda, K.; Yamori, Y. Cyanidin-3-glucoside regulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. FEBS Lett. 2004, 574, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.K.; Choi, S.; Lee, Y.R.; Lee, E.; Park, M.; Park, K.; Kim, C.-S.; Lim, Y.; Park, J.-T.; Jeon, B.H. Anthocyanin-Rich Extract from Red Chinese Cabbage Alleviates Vascular Inflammation in Endothelial Cells and Apo E Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.W.; Ikeda, K.; Yamori, Y. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by cyanidin-3-glucoside, a typical anthocyanin pigment. Hypertension 2004, 44, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, D.; Cimino, F.; Fratantonio, D.; Molonia, M.S.; Bashllari, R.; Busà, R.; Saija, A. Speciale, Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside Modulates the In Vitro Inflammatory Crosstalk between Intestinal Epithelial and Endothelial Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 3454023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Li, Q.; He, L.; Weng, H.; Su, D.; Liu, X.; Ling, W.; Wang, D. Protocatechuic Acid Inhibits Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Lesion Progression in Older Apoe-/- Mice. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, T.; Ebuchi, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Fukui, K.; Sugita, K.; Terahara, N.; Matsumoto, K. Anti-hyperglycemic effect of diacylated anthocyanin derived from Ipomoea batatas cultivar Ayamurasaki can be achieved through the α-glucosidase inhibitory action. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7244–7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Boon, H.; Rochon, P.; Moher, D.; Barnes, J.; Bombardier, C.; CONSORT Group. Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interventions: An elaborated CONSORT statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Berry/Source | Phytochemical Class | Representative Compounds | Main Vascular-Relevant Actions | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blueberries | Anthocyanins | Malvidin-, delphinidin-, cyanidin-, petunidin-, peonidin-glycosides | NO/eNOS activation; antioxidant & anti-inflammatory; improved endothelial function; modest BP reduction | [13,14,16,20,21,23,24,25,26,33,50,52,53,56,94] |

| Blueberries | Flavonols | Quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol glycosides | Antioxidant; improves NO bioavailability; supports vasodilation | [11,13,14,16,43,46,50,55] |

| Blueberries | Flavan-3-ols & PACs | Catechin, epicatechin, proanthocyanidin oligomers | Inhibits LDL oxidation; modulates platelets; supports cholesterol efflux | [14,16,20,23,27,50,98,108,109] |

| Blueberries | Phenolic acids | Chlorogenic, caffeic, ferulic, PCA | Reduces oxidative stress; improves endothelial function; anti-inflammatory | [14,28,89,90,94,110,111,112,113,114] |

| Blueberries | Stilbenes | Pterostilbene, resveratrol | Antioxidant; anti-inflammatory; eNOS activation; lipid effects | [13,14,16,21,50,52,53] |

| Blueberries | Vitamins & micronutrients | Vitamin C, vitamin E, trace elements | Antioxidant protection; prevents LDL oxidation; supports redox homeostasis | [11,16,50,115,116] |

| Blueberries | Dietary fiber & matrix | Fiber, organic acids, sugars | Modulates glycemia/lipemia; gut microbiota interactions | [14,16,21,34,35,36,37,38,48,94] |

| Haskap | Anthocyanins | C3G, cyanidin-3-rutinoside, cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside | Strong antioxidant/anti-inflammatory; AMPK/eNOS & PPAR-α activation | [64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,75,76,78,84,85,101,102,103,106,107] |

| Haskap | Flavonols | Quercetin, rutin, kaempferol | Antioxidant & anti-inflammatory; endothelial support | [64,65,68,79,104] |

| Haskap | Flavan-3-ols & PACs | Catechin, epicatechin, proanthocyanidins | Antioxidant; oxidative stress & inflammation modulation | [64,75,79,80,81,84] |

| Haskap | Phenolic acids | Chlorogenic, caffeic-type acids, PCA, vanillic | Antioxidant; AMPK/Nrf2/NF-κB modulation | [64,65,71,72,74,76,101,102,103,106,107] |

| Haskap | Iridoids | Loganic acid, loganin, sweroside | Anti-inflammatory & antioxidant; metabolic/vascular support | [62,64,65,66,68,71,72,74,75,76,84,85] |

| Haskap | Vitamins & micronutrients | Vitamin C, vitamin E, minerals | High antioxidant capacity; endothelial protection | [50,64,65,66,67,72] |

| Haskap | Dietary fiber & matrix | Fiber, organic acids, sugars | Modulates microbiota; impacts metabolism & lipid handling | [64,66,67,74,75,76,84,85,101,102,103,106,107] |

| Berry/Source | Major Anthocyanins (Predominant Glycosides) | Approximate Total Anthocyanin Content (mg/100 g Fresh Weight) * | Notable Features of Anthocyanin Profile and Differences | Selected References ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) | Malvidin-3-glucoside and malvidin-3-galactoside (often predominant); delphinidin-3-glucoside/-galactoside, petunidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin-3-glucoside, peonidin glycosides. | Typically ~80–300 mg/100 g FW across cultivated highbush and lowbush blueberries; wild or strongly pigmented cultivars can reach or exceed ~400–450 mg/100 g FW, depending on genotype, growing conditions and analytical method. | Broad and relatively balanced spectrum of malvidin-, delphinidin- and petunidin-based anthocyanins; pigments mainly localized in the skin. Compared with haskap, blueberry anthocyanins show a higher contribution of malvidin-based glycosides and a somewhat lower proportion of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G). | [13,14,16,20,21,23,24,25,26,29,30,33,50,52,53,56,94] (or subset used in Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4) |

| Honeysuckle berries/haskap (Lonicera caerulea L.) | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G; predominant); cyanidin-3-rutinoside, cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside; pelargonidin-3-glucoside, peonidin glycosides. | Across cultivars, total anthocyanin content commonly ranges from ≈150 up to >650 mg/100 g FW; values around 250–400 mg/100 g FW are frequently reported, with high-C3G genotypes (e.g., ‘Wuhezhen’) showing C3G levels ≈400–500 mg/100 g FW. | Anthocyanin profile is strongly dominated by C3G, leading to very intense dark-purple coloration. Compared with blueberries, haskap tends to have higher total anthocyanin concentrations and a more ‘cyanidin-centric’ profile, often accompanied by substantial contributions from iridoids and phenolic acids in the overall phytochemical matrix. | [39,40,54,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,75,76,78,84,101,102,103,106,107] (or subset used in Section 4.2, Section 4.3, Section 4.4) |

| Pathway/Endpoint | Key Molecular Targets & Effects | Evidence for Blueberries | Evidence for Haskap |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO/eNOS-mediated vasodilation | ↑ PI3K/Akt–eNOS; ↑ eNOS Ser1177; ↑ NO; ↓ eNOS uncoupling | ↑ NO & vasodilation in models; RCTs show ↑ FMD & modest DBP reductions | C3G/haskap activates AMPK–eNOS; ↑ NO; BP-lowering in animals; emerging acute BP effects |

| NRF2-dependent antioxidant defense | ↑ NRF2; ↑ HO-1, SOD, catalase, GPx; ↓ NOX4, XO; ↓ ROS | Blueberries activate NRF2; ↓ ROS; improved oxidative-stress markers | C3G/PCA induce HO-1/SOD; antioxidant protection in hepatic & CV models |

| Inflammatory signaling | ↓ NF-κB; ↓ ICAM-1, VCAM-1, MCP-1; ↓ TNF-α, IL-6; MAPK modulation | Malvidin anthocyanins ↓ NF-κB & adhesion molecules; vascular improvements in trials | Haskap/C3G/iridoids suppress NF-κB/MAPK; ↓ cytokines; early vascular inflammation signals |

| LDL oxidation & atherogenesis | ↓ LDL oxidation; ↓ oxLDL; ↑ antioxidant protection; anti-foam cell effects | ↓ LDL oxidation; some RCTs show ↓ oxLDL & improved redox status | Haskap/C3G reduce oxidative stress & lipid accumulation; anti-atherogenic potential |

| HDL function & cholesterol efflux | ↑ HDL PON1; ↑ cholesterol efflux | ↑ HDL efflux capacity & PON1 in dyslipidemia | Limited direct data; metabolites improve lipid handling in models |

| Platelet function & thrombosis | ↓ platelet activation/aggregation; ↓ TxA2; GPVI/Syk modulation | Blueberries reduce aggregation & TxA2 in human/ex vivo studies | No trials; C3G/flavonoids show antiplatelet effects in models |

| Endothelial barrier & leukocyte adhesion | ↓ adhesion molecules; ↓ monocyte adhesion; barrier protection | ↓ ICAM-1/VCAM-1 & monocyte adhesion; improved FMD & stiffness | Haskap/C3G reduce adhesion markers; consistent early human vascular signals |

| Metabolic & microbiota-mediated effects | AMPK activation; PPAR-α; improved insulin sensitivity; microbiota modulation | Improved insulin sensitivity & metabolic markers; metabotype-dependent | Haskap activates AMPK/PPAR-α; ↓ steatosis; modulates microbiota; improves cardiometabolic markers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jurja, S.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Mehedinți, M.-C.; Hincu, M.-A.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S.; Roncea, F.-N.; Laurențiu Tatu, A. Blueberries and Honeysuckle Berries: Anthocyanin-Rich Polyphenols for Vascular Endothelial Health and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3888. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243888

Jurja S, Negreanu-Pirjol T, Mehedinți M-C, Hincu M-A, Negreanu-Pirjol B-S, Roncea F-N, Laurențiu Tatu A. Blueberries and Honeysuckle Berries: Anthocyanin-Rich Polyphenols for Vascular Endothelial Health and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3888. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243888

Chicago/Turabian StyleJurja, Sanda, Ticuta Negreanu-Pirjol, Mihaela-Cezarina Mehedinți, Maria-Andrada Hincu, Bogdan-Stefan Negreanu-Pirjol, Florentina-Nicoleta Roncea, and Alin Laurențiu Tatu. 2025. "Blueberries and Honeysuckle Berries: Anthocyanin-Rich Polyphenols for Vascular Endothelial Health and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3888. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243888

APA StyleJurja, S., Negreanu-Pirjol, T., Mehedinți, M.-C., Hincu, M.-A., Negreanu-Pirjol, B.-S., Roncea, F.-N., & Laurențiu Tatu, A. (2025). Blueberries and Honeysuckle Berries: Anthocyanin-Rich Polyphenols for Vascular Endothelial Health and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Nutrients, 17(24), 3888. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243888