Polyphenol-Microbiota Interactions in Atherosclerosis: The Role of Hydroxytyrosol and Tyrosol in Modulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

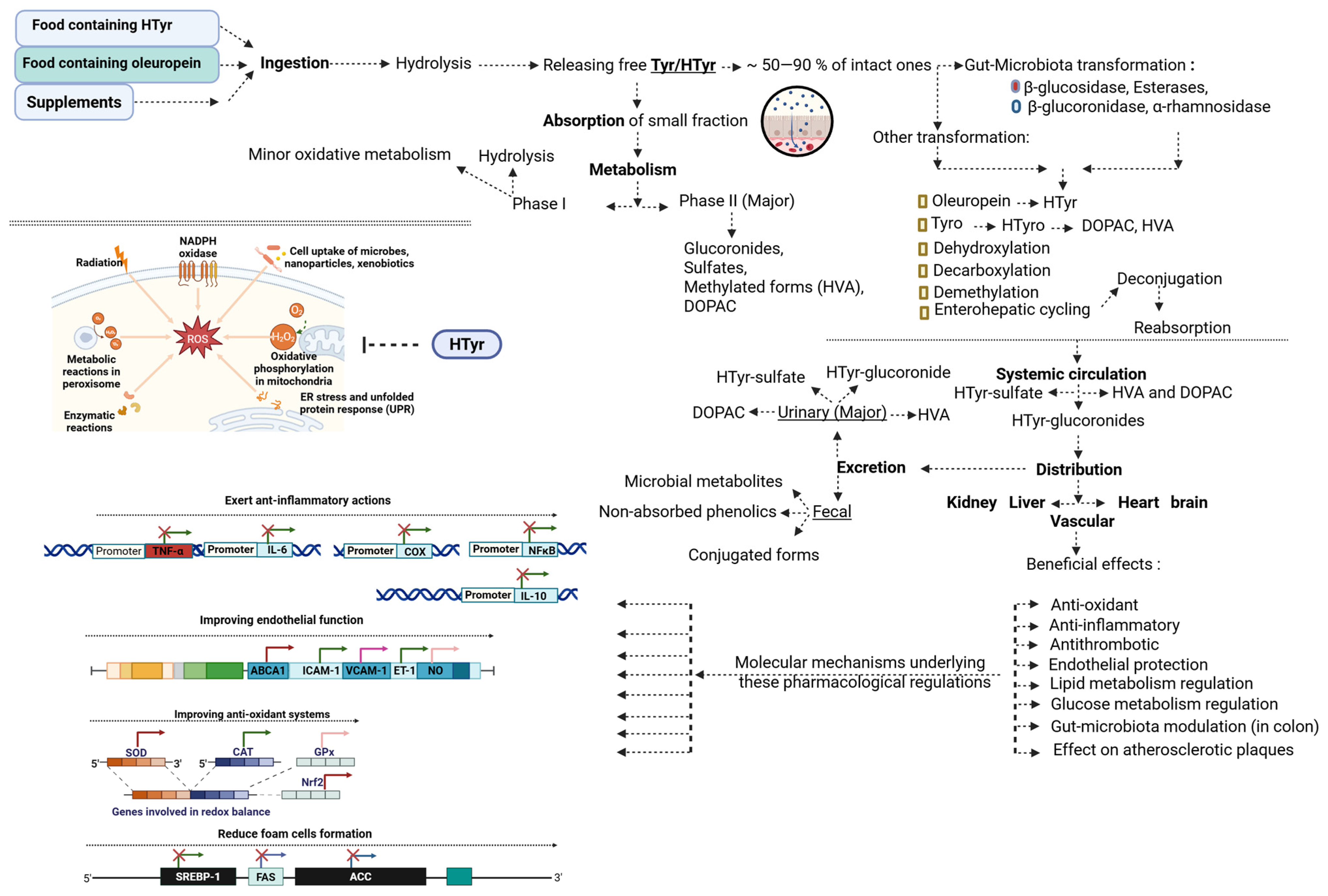

2. Metabolism and Bioavailability of Hydroxytyrosol and Tyrosol

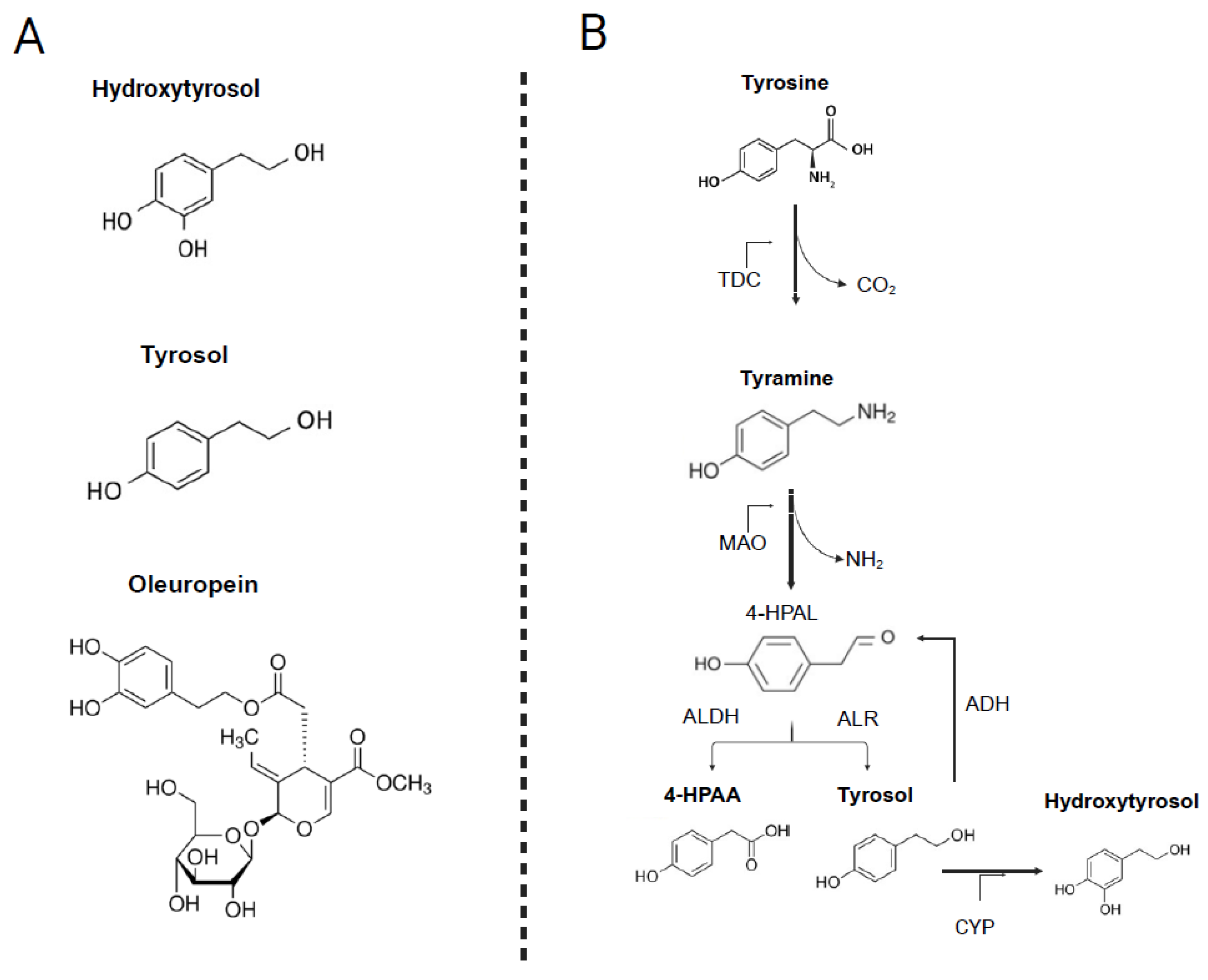

2.1. Chemical Structure

2.2. Natural Dietary Sources

2.3. Absorption and Metabolism of HTyr and Tyr

2.4. Endogenous Metabolism of Tyrosol

2.5. Factors Modulating Bioavailability and Interindividual Variability

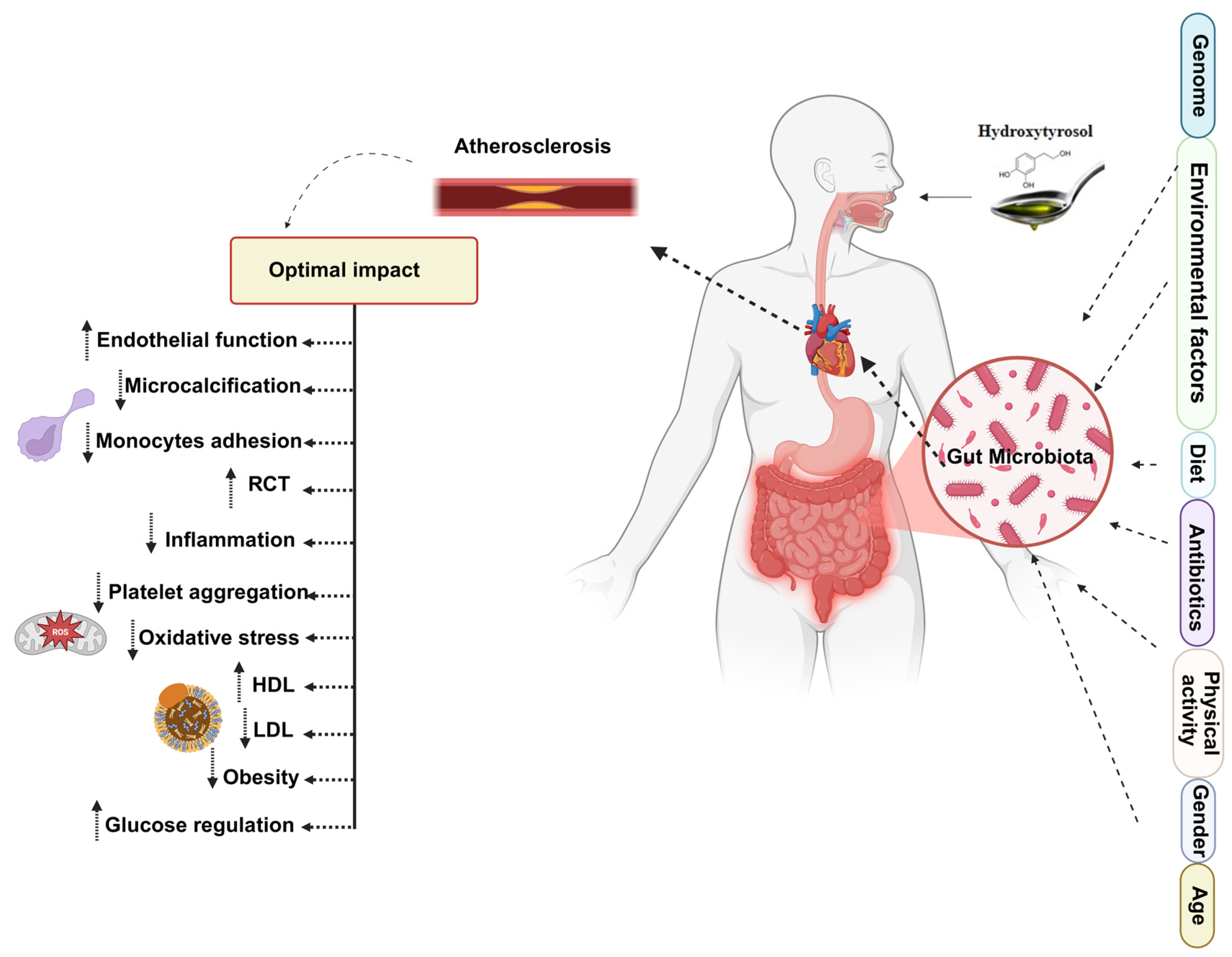

3. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Atherosclerosis

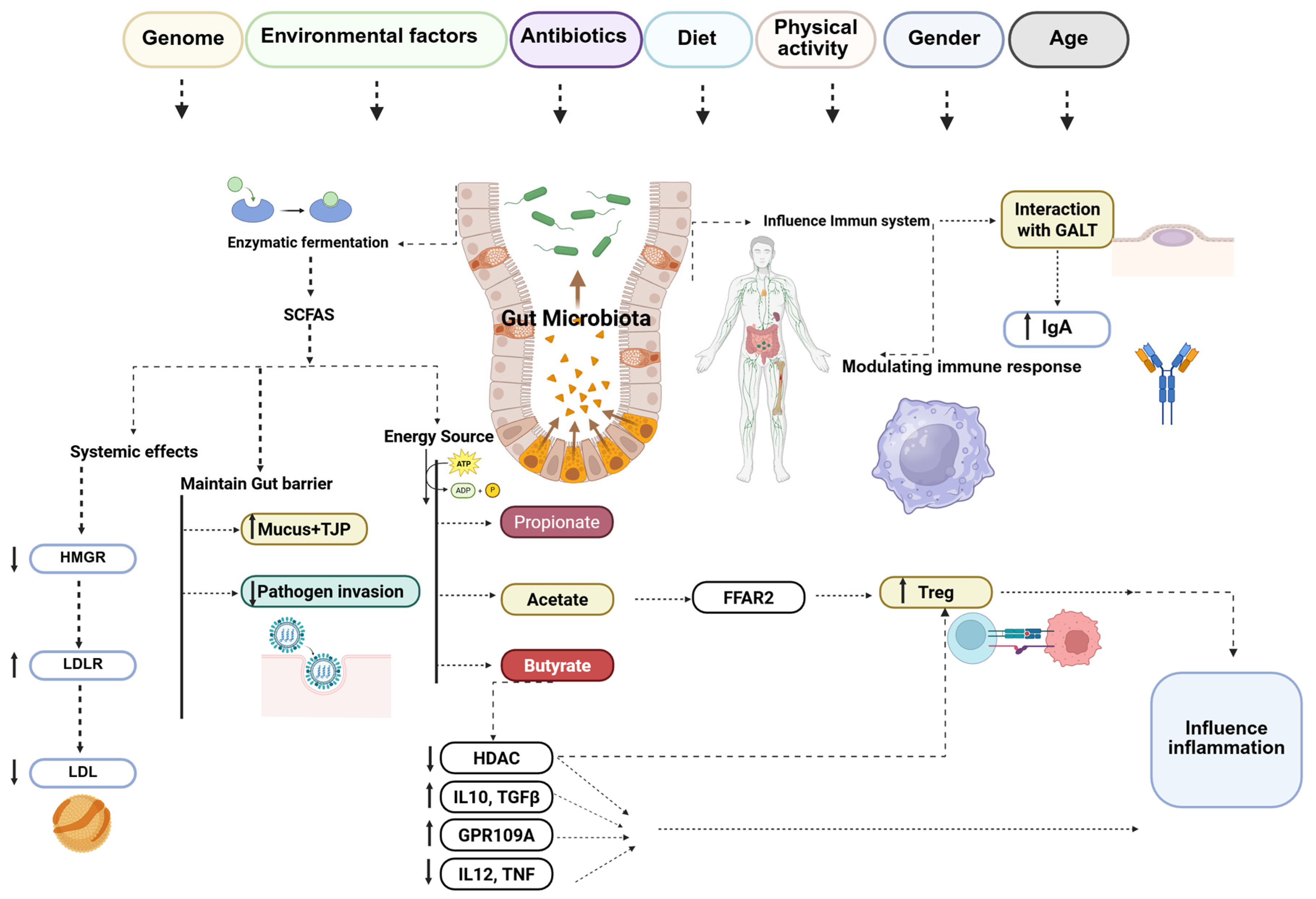

3.1. Gut Microbiota Composition

3.2. Gut Microbiota Functions Related to Host Metabolism

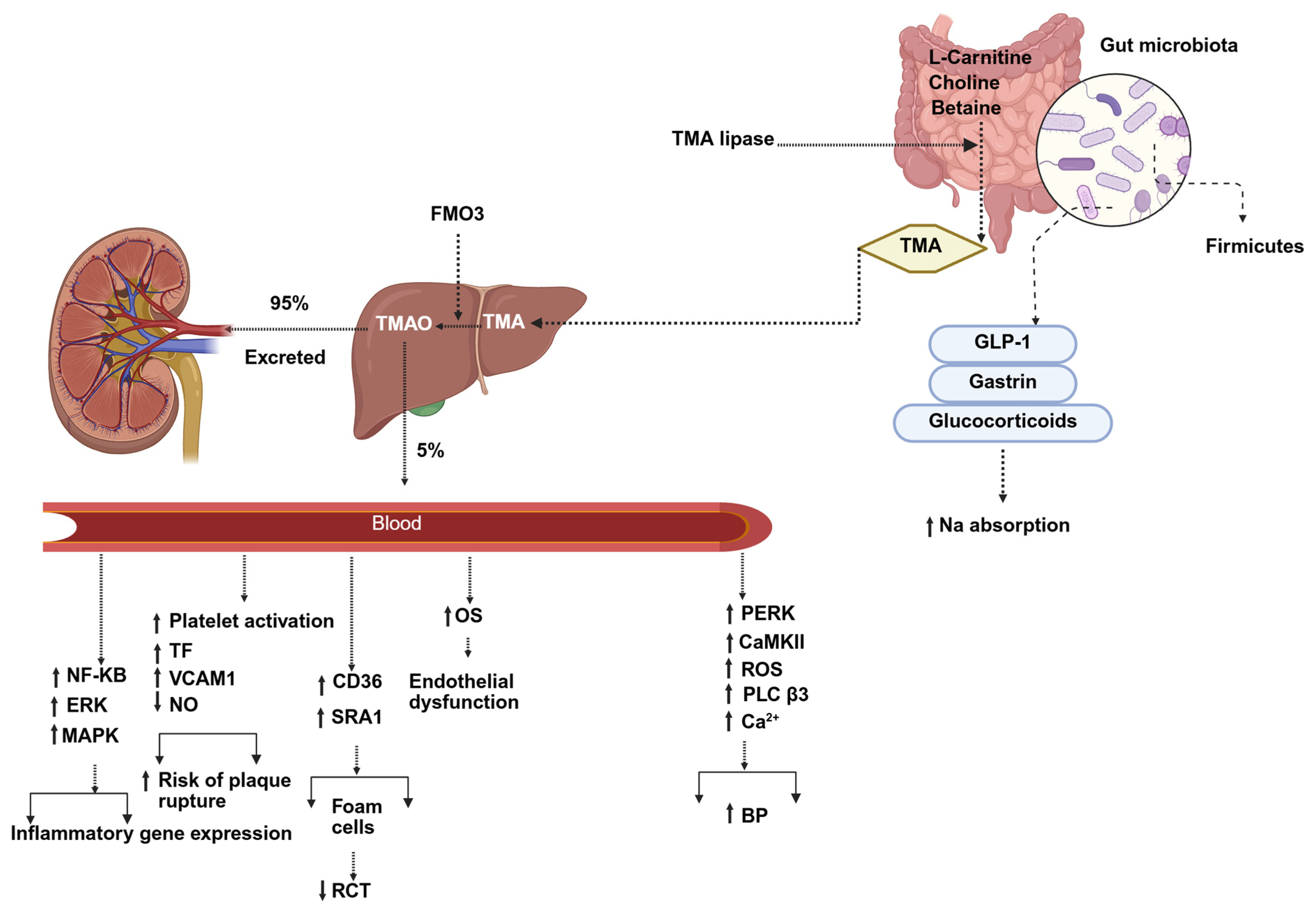

3.3. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Atherosclerosis

4. Bidirectional Interactions Between Polyphenols (with a Focus on HTyr/Tyr) and the Gut Microbiota

4.1. Microbial Biotransformation of Hydroxytyrosol and Tyrosol

4.2. Effects of HTyr/Tyr on Gut Microbiota Composition

4.3. Host and Dietary Factors Influencing Polyphenol-Microbiota Interactions

4.4. Interindividual Variability and the Concept of “Metabotypes”

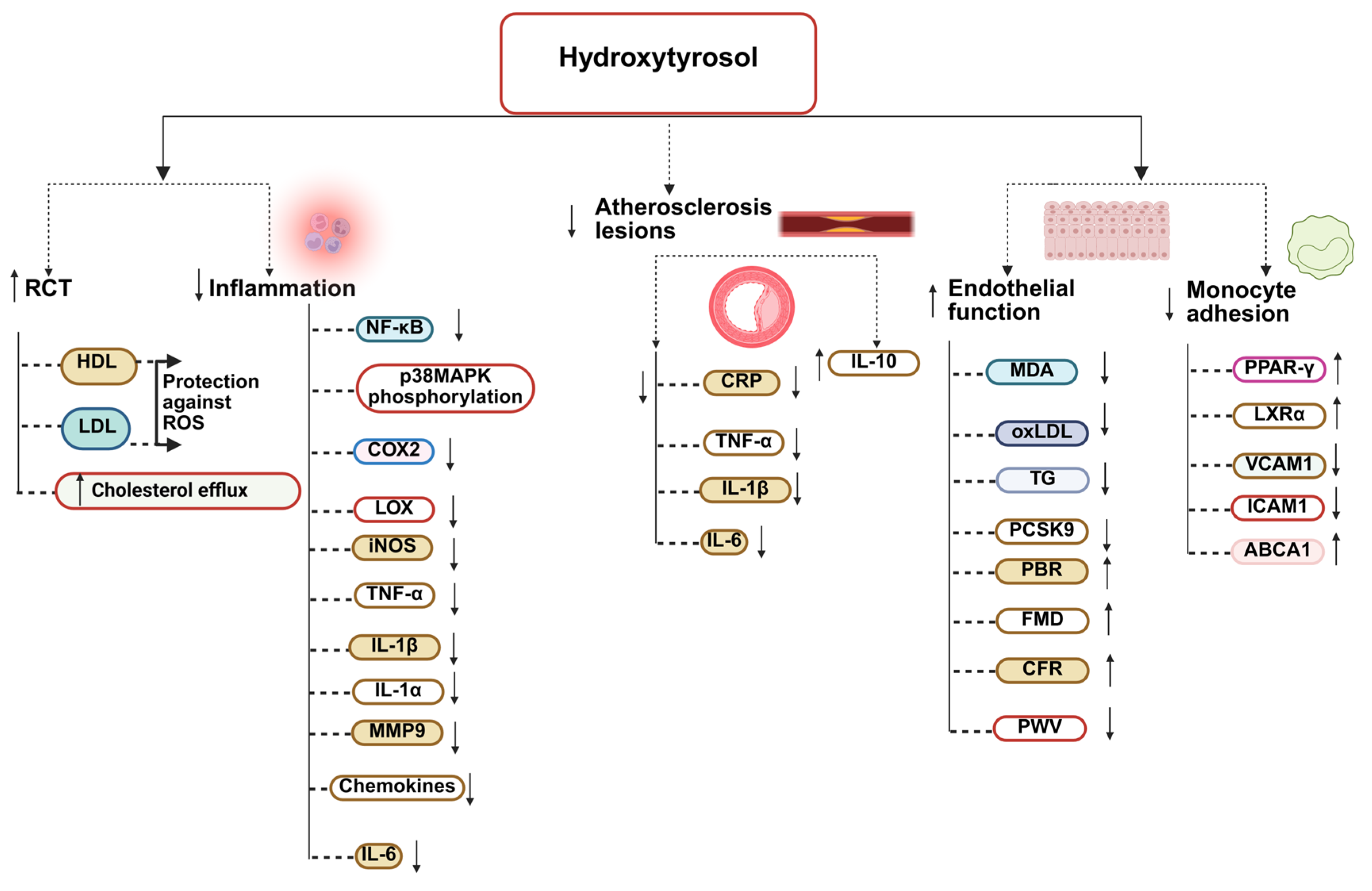

5. Mechanistic Insights into Cardiometabolic Protection

5.1. Endothelial Protective and Anti-Thrombotic Effects

5.2. Antioxidant and Mitochondrial Protective Effects

5.3. Anti-Inflammatory Pathways

5.4. Effects on Lipid and Glucose Metabolism

5.5. Evidence from Human Clinical Studies

5.5.1. Overall Effects on Cardiometabolic Biomarkers

| Study, Year | Country | Study Design | Population | Duration (Weeks) | Intervention | N | Control | Sex (M/F) | Measured Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |||||||||

| Vázquez-Velascoet al., 2011 [222] | Spain | Randomized controlled trial, crossover | Healthy subjects | 3 | Enriched sunflower: 10–15 g/d (45–50 mg/d HTyr) | 22 | 22 | Non-enriched sunflower oil | M/F | ↑ ARE (PON-1 activity), ↓ ox-LDL, ↓ sVCAM-1, ↔ TC, ↔ HDL, ↔ LDL, ↔ TG, ↔ BMI, ↔ BW |

| de Bock et al., 2013 [223] | New Zealand | Randomized controlled trial, crossover | Overweight subjects | 12 | Olive leaf extract capsules: (51.1 mg/d oleuropein and 9.7 mg/d HTyr) | 22 | 23 | Safflower oil | M | ↑ IL-6, ↔ IL-8, ↔ TNF-α, ↔ CRP, ↔ ox-LDL, ↔ TC, ↔ HDL, ↔ LDL, ↔ TG, ↔ BW, ↔ BMI, ↔ BP |

| Crespo et al., 2015 [202] | Spain | Randomized controlled trial, Latin square design | Healthy subjects | 1 | Enriched olive mill wastes water extract: 5 or 25 mg/d HTyr | 21 | 21 | Placebo (maltodextrin) | M/F | ↔ IL-6, ↔ IL-8, ↔ IL-10, ↔ IL-17, ↔ MCP-1, ↔ TNF-α, ↔ VEGF, ↔ hs-CRP, ↔ Iso, ↔ ox-LDL, ↔ TXB2, ↔ TC, ↔ HDL, ↔ LDL, ↔ TG, ↔ BW, ↔ BMI, ↔ BP, ↔ BF |

| Filip et al., 2015 [224] | Poland | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Postmenopausal and osteopenic | 52 | Supplementation: 250 mg/d olive extract (100 mg/d oleuropein) + 1000 mg Ca | 32 | 32 | Placebo + 1000 mg Ca | F | ↔ hs-CRP, ↔ IL-6, ↓ TC, ↓ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↓ TG, ↔ BW, ↔ BMI |

| Colica et al., 2017 [225] | Italy | Randomized controlled trial, crossover | Healthy subjects | 3 | Supplementation: (15 mg/d HTyr) | 28 | 28 | Placebo | M/F | ↑ TAS, ↑ Thiols, ↑ SOD-1, ↓ MDA, ↔ TC, ↔ HDL, ↔ LDL, ↔ TG, ↔ FBG, ↔ Ins, ↔ ox-LDL, ↓ BW, ↔ WC, ↔ WHR |

| Lockyer et al., 2017 [226] | New Zealand | Randomized controlled trial, crossover | Pre-hypertensive subjects | 6 | Olive leaf extract: (136.2 mg/d oleuropein and 6.4 mg/d HTyr) | 60 | 60 | Placebo | M | ↓ IL-8, ↔ ox-LDL, ↔ CRP, ↔ ICAM, ↔ VCAM, ↔ P-s, ↔ E-s, ↔ IL-1β, ↔ IL-6, ↔ IL-10, ↔ TNF-α, ↓ TC, ↓ HDL, ↓ LDL, ↓ TG, ↔ FBG, ↔ Ins, ↔ HOMA-IR, ↔ QUICKI, ↔ BP |

| Araki et al., 2019 [227] | Japan | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Pre-diabetic subjects | 12 | Olive leaf tea: (324 mg/d oleuropein and 12 mg/d HTyr) | 28 | 29 | Olive leaf tea: (24 mg/d oleuropein and 3 mg/d HT) | M/F | ↓ TG, ↓ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↓ FBG, ↔ Ins, ↔ HOMA-IR, ↔ HbA1c, ↔ BW, ↔ WC |

| Conterno et al., 2019 [228] | Italy | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Hypercholesterolaemic subjects | 8 | Enriched biscuits with olive pomace: (15.39 mg/d HTyr and its derivatives) | 34 | 28 | Control biscuits | M/F | ↔ BW, ↔ BMI, ↔ WC, ↔ BP, ↔ HDL, ↔ TC, ↔ LDL, ↔ TG, ↔ Apo A1, ↔ Apo B, ↔ FBG, ↔ Ins, ↔ CRP, ↔ ox-LDL, ↔ F2 Iso |

| Dinu et al., 2021 [229] | Italy | Randomized controlled trial, crossover | Healthy subjects | 8.5 | Olive pâté supplementation: (30 mg/d HTyr) | 19 | 19 | Placebo | M/F | ↑ Nrf-2, ↓ MCP-1, ↔ IL-1 ra, ↔ IL-6, ↔ IL-8, ↔ IL-10, ↔ IL-12, ↔ IL-17, ↔ TNF-α, ↔ VEGF, ↓ TC, ↔ HDL, ↓ LDL, ↔ TG, ↔ HOMA-IR, ↔ Ins, ↔ FBG, ↔ BW, ↔ BMI |

| Stevens et al., 2021 [230] | Netherlands | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Overweight/obese subjects | 8 | Olive leaf extract supplementation: (83.5 mg/d oleuropein) | 39 | 38 | Placebo | M/F | ↔ ox-LDL, ↔ BP, ↔ HR, ↔ BW, ↔ BMI, ↔ TG, ↔ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↔ TC, ↔ FBG, ↔ Ins |

| Fytili et al., 2022 [231] | Greece | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Overweight/obese subjects | 24 | Supplementation: (15 mg/d HTyr) | 9 | 11 | Placebo | F | ↓ BW, ↓ BF |

| Horcajada et al., 2022 [232] | Belgium | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Subjects with knee pain | 26 | Olive leaf extract supplementation: (100 mg/d oleuropein) | 59 | 59 | Placebo | M/F | ↔ PGE2, ↔ IL-8, ↔ TNF-α |

| Binou et al., 2023 [233] | Greece | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Overweight/obese subjects with T2DM | 12 | Enriched whole wheat bread: (32.5 mg/d HTyr) | 30 | 30 | Control whole wheat bread | M/F | ↔ HbA1c, ↓ FBG, ↓ TC, ↓ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↔ TG, ↔ Ins, ↔ Leptin, ↔ BP, ↔ Adiponectin, ↔ hs-CRP, ↔ TNF-α, ↔ ox-LDL, ↔ BW, ↔ BMI, ↔ WC, ↓ BF |

| Ikonomidis et al., 2023 [201] | Greece | Randomized controlled trial, crossover | Subjects with chronic CAS | 4 | Supplementation: (Olive oil + 10 mg/d HTyr) | 30 | 30 | Olive oil | M/F | ↑ FMD, ↑ PWV, ↑ PBR, ↑ CFR, ↓ MDA, ↓ PCSK9, ↓ CRP, ↓ ox-LDL, ↓ TG, ↔ TC, ↔ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↔ BP |

| Naranjo et al., 2024 [234] | Spain | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Subjects with acute ischemic stroke | 6 | Supplementation: (15 mg/d HTyr) | 4 | 4 | Placebo | M | ↔ FBG, ↔ HbA1c, ↔ TC, ↔ LDL, ↓ HDL, ↔ TG, ↓ NO, ↔ IL-6, ↔ TBARS, ↔ BMI, ↔ BP |

| Imperatrice et al., 2024 [235] | Netherlands | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Postmenopausal women | 12 | Olive leaf extract supplementation: (100 mg/d oleuropein) | 29 | 31 | Placebo | F | ↓ TG, ↔ TC, ↔ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↔ BF |

| Pinckaers et al., 2025 [236] | Netherlands | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Older males | 5 | Olive leaf extract supplementation: (100 mg/d oleuropein) | 20 | 20 | Placebo | M | ↓ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↔ TG, ↔ TC |

| Moratilla-Rivera et al., 2025 [237] | Spain | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Overweight subjects with prediabetes | 16 | Supplementation: (15 mg/d HTyr) | 24 | 25 | Placebo | M/F | ↓ ox-LDL, ↓ PCO, ↓ 8-OHdG, ↓ IL-6, ↔ *TAS, ↔ *GPx, ↔ TC, ↔ LDL, ↔ HDL, ↔ TG, ↔ BW, ↔ BMI |

| Haidari et al., 2025 [238] | Iran | Randomized controlled trial, parallel | Obese subjects | 8 | Olive leaf extract supplementation: (100 mg/d oleuropein) | 31 | 32 | Placebo | F | ↓ MDA, ↔ TAS |

5.5.2. Dose–Response Considerations

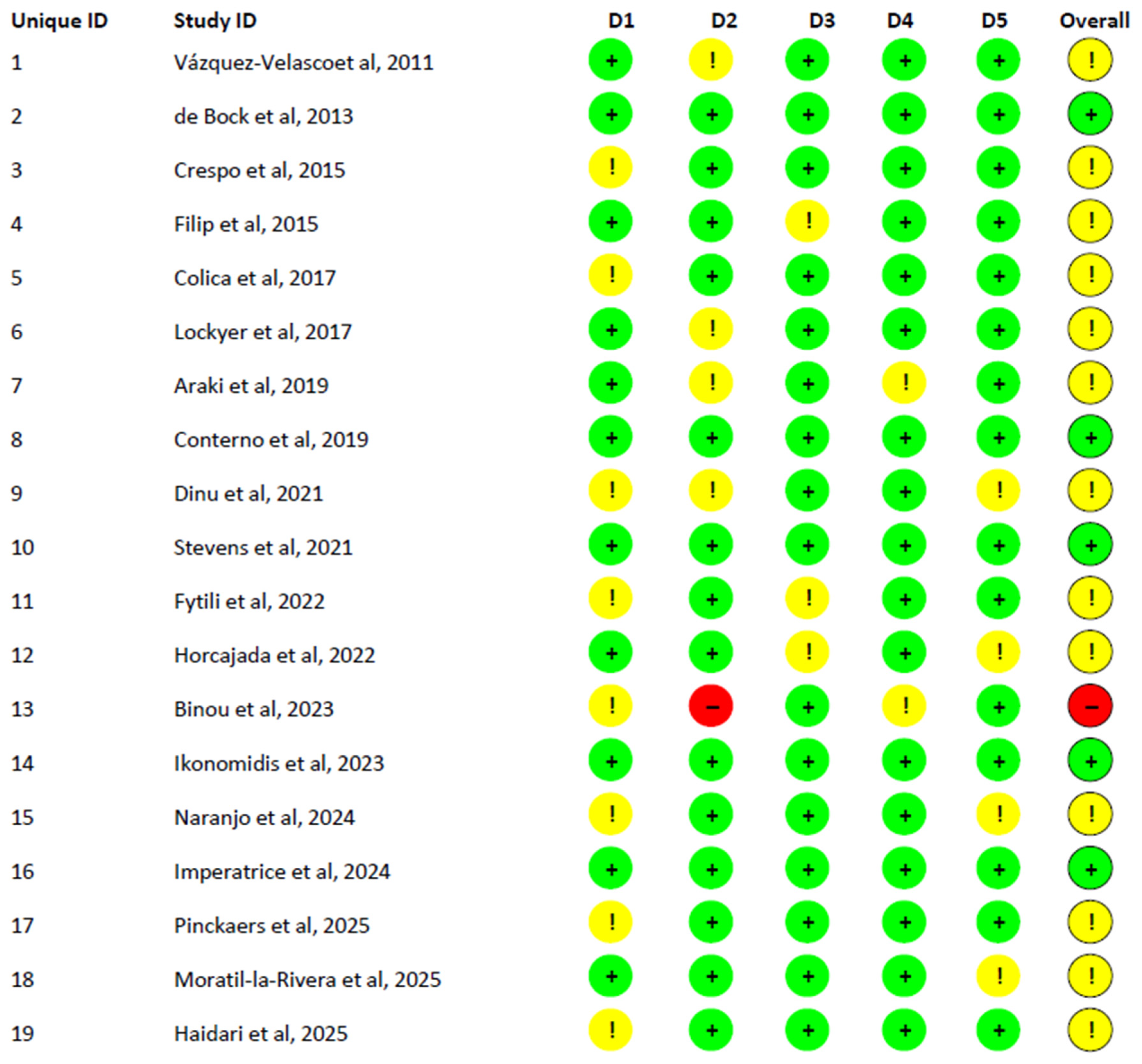

5.5.3. Risk of Bias (RoB2) Assessment

5.6. Summary of Clinical and Mechanistic Benefits

5.7. Summary of Preclinical Evidence (In Vitro and Animal Studies)

6. The HTyr/Tyr-Gut Microbiota-Atherosclerosis Axis

7. Challenges, Translational Limitations, and Future Perspectives

7.1. Methodological, Bioavailability, and Dose-Relevance Limitations

7.2. Biological Differences Between HTyr and Tyr, Safety, and Potential Interactions

7.3. Interindividual Responses and Microbiota-Driven Variability

7.4. Priority Gaps for Future Human Studies

- Dose-ranging randomized controlled trials using standardized and chemically characterized phenolic compositions.

- Longer intervention durations capable of assessing glycemic control, adiposity, vascular remodeling, and cardiometabolic outcomes.

- Parallel profiling of circulating metabolites (metabolomics, lipidomics) to confirm bioavailability and metabolic pathways in humans.

- Detailed microbiome sequencing to identify HTyr/Tyr metabotypes and characterize responder vs. non-responder phenotypes.

- Controlled lifestyle factors, including dietary background, to reduce confounding from macronutrient and micronutrient patterns, fiber intake, or other polyphenols.

- Systematic evaluation of drug-nutrient interactions, especially in populations taking cardiometabolic medications.

- Comparative studies of HTyr vs. Tyr to clarify their differential potency and specific mechanisms.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABCA1 | ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 |

| ABCG1 | ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 1 |

| ACC | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 |

| ADH | Alcohol dehydrogenase |

| ALDH | Aldehyde dehydrogenase |

| ALR | Aldehyde reductase |

| AMPK | Activated AMP-activated protein kinase |

| APC | Antigen presenting cell |

| Apo | Apolipoprotein |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| CA | Cholic acid |

| CAT | Catalase |

| Ca2+ | Calcium ion |

| CaMKII | Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| CD36 | Cluster of differentiation 36 |

| CDCA | Chenodeoxycholic acid |

| CFR | Coronary flow reserve |

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyltransferase |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CYP | Cytochrome P |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| DCA | Deoxycholic acid |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DOPAC | 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid |

| EA | Ellagic acid |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| FAS | Fatty acid synthase |

| FFAR2 | Free fatty acid receptor 2 |

| FMD | Flow-mediated dilation |

| FMO3 | Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| GALT | Gut-associated lymphoid tissue |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GPR109A | G protein-coupled receptor 109A |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HMGR | 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase |

| 4-HPAA | 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid |

| 4-HPAL | 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde |

| hs-CRP | High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| HTyr | Hydroxytyrosol |

| HVA | Homovanillic acid |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| IFNγ | Interferon gamma |

| IgA | Immunoglobulin A |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ITS | Internal transcribed spacer |

| JNK | Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LCA | Lithocholic acid |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| LXRα | Liver X Receptor Alpha |

| MAIT | Mucosal-associated invariant T |

| MAO | Monoamine oxidase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 |

| MerTK | Mer proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NKT | Natural killer T |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| Npc1l1 | Niemann-Pick C1-like1 |

| NRF-1 | Nuclear respiratory factor-1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor-E2-related factor 2 |

| Ox-LDL | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| PA | Propionic acid |

| PAGln | Phenylacetylglutamine |

| PBR | Perfused boundary region |

| PCSK9 | Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 |

| PDE | Phosphodiesterase |

| PERK | Protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α |

| PLC β3 | Phospholipase C β3 |

| PPyA | Phenylpyruvic acid |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma |

| PSA | Polysaccharide A |

| PWV | Pulse wave velocity |

| RCT | Reverse cholesterol transport |

| rRNA | ribosomal Ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCD1 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SR-A1 | Scavenger receptor class A1 |

| SREBP | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein |

| SULT | Sulfotransferase |

| TDC | Tyrosine decarboxylase |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TF | Tissue factor |

| TFAM | Mitochondrial transcription factor A |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TGR5 | Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 |

| Th | T-helper |

| TJP | Tight junction proteins |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| Tyr | Tyrosol |

| UGT | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase |

| VCAM1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VLDL | Very- low-density lipoprotein |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebari-Benslaiman, S.; Galicia-García, U.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Olaetxea, J.R.; Alloza, I.; Vandenbroeck, K.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Hashim, M.J.; Mustafa, H.; Baniyas, M.Y.; Al Suwaidi, S.K.B.M.; AlKatheeri, R.; Alblooshi, F.M.K.; Almatrooshi, M.E.A.H.; Alzaabi, M.E.H.; Al Darmaki, R.S.; et al. Global epidemiology of ischemic heart disease: Results from the global burden of disease study. Cureus 2020, 12, e9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Buring, J.E.; Badimon, L.; Hansson, G.K.; Deanfield, J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Lewis, E.F. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, T.; Hu, M.; Xu, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhou, T.; Liu, J.; Guo, L.; Ao, H.; Ye, Q. Novel wine in an old bottle: Preventive and therapeutic potentials of andrographolide in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. J. Pharm. Anal. 2023, 13, 563–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47 (Suppl. S8), C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Rimm, E.B.; Medina-Remón, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; López-Sabater, M.C.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Polyphenol intake and mortality risk: A re-analysis of the PREDIMED trial. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, C.; Franceschelli, S.; Quiles, J.L.; Speranza, L. Wide Biological Role of Hydroxytyrosol: Possible Therapeutic and Preventive Properties in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rienks, J.; Barbaresko, J.; Nöthlings, U. Association of Polyphenol Biomarkers with Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P.E.; Abd El Mohsen, M.M.; Minihane, A.M.; Mathers, J.C. Biomarkers of the intake of dietary polyphenols: Strengths, limitations and application in nutrition research. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinane, C.M.; Cotter, P.D. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: Understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.F.; Dwivedi, G.; O’Gara, F.; Caparros-Martin, J.; Ward, N.C. The gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease: Current knowledge and clinical potential. Am. J. Physiol-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317, H923–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, R.; Bermúdez, V.; Galban, N.; Garrido, B.; Santeliz, R.; Gotera, M.P.; Duran, P.; Boscan, A.; Carbonell-Zabaleta, A.-K.; Durán-Agüero, S.; et al. Dietary Polyphenols and Gut Microbiota Cross-Talk: Molecular and Therapeutic Perspectives for Cardiometabolic Disease: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, L. Gut microbiome and metabolites, the future direction of diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis? Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 187, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Hazen, S.L. The gut microbial endocrine organ: Bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carding, S.; Verbeke, K.; Vipond, D.T.; Corfe, B.M.; Owen, L.J. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 26191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamada, D.; Vodnar, D.C. Polyphenols-Gut Microbiota Interrelationship: A Transition to a New Generation of Prebiotics. Nutrients 2021, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.L.Y.; Co, V.A.; El-Nezami, H. Dietary polyphenol impact on gut health and microbiota. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, 2, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Souto, E.B.; Cicala, C.; Caiazzo, E.; Izzo, A.A.; Novellino, E.; Santini, A. Polyphenols: A concise overview on the chemistry, occurrence, and human health. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2221–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential Health Benefits of Olive Oil and Plant Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.E.M.; Badran, K.S.A.; Baraka, M.A.; Althagafy, H.S.; Hassanein, E.H.M. Mechanism and impact of heavy metal-aluminum (Al) toxicity on male reproduction: Therapeutic approaches with some phytochemicals. Life Sci. 2024, 340, 122461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T. Polyphenols-absorption and occurrence in the body system. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2022, 28, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.; Strassmann, S.; Golz, C. Oral Bioavailability and Metabolism of Hydroxytyrosol from Food Supplements. Nutrients 2023, 15, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronat, A.; Rodriguez-Morató, J.; Serreli, G.; Fitó, M.; Tyndale, R.F.; Deiana, M.; de la Torre, R. Contribution of Biotransformations Carried Out by the Microbiota, Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes, and Transport Proteins to the Biological Activities of Phytochemicals Found in the Diet. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2172–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, G.; Spencer, J.P.; Dessi, M.A. Extra virgin olive oil phenolics: Absorption, metabolism, and biological activities in the GI tract. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2009, 25, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaforio, J.J.; Sánchez-Quesada, C.; López-Biedma, A.; del Carmen Ramírez-Tortose, M.; Warleta, F. Molecular aspects of squalene and implications for olive oil and the mediterranean diet. In The Mediterranean Diet; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Mar, M.I.; Mateos, R.; García-Parrilla, M.C.; Puertas, B.; Cantos-Villar, E. Bioactive compounds in wine: Resveratrol, hydroxytyrosol and melatonin: A review. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.; Manna, C.; Migliardi, V.; Mazzoni, O.; Morrica, P.; Capasso, G.; Pontoni, G.; Galletti, P.; Zappia, V. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of hydroxytyrosol, a natural antioxidant from olive oil. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001, 29, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Morató, J.; Boronat, A.; Kotronoulas, A.; Pujadas, M.; Pastor, A.; Olesti, E.; Pérez-Mañá, C.; Khymenets, O.; Fitó, M.; Farré, M.; et al. Metabolic disposition and biological significance of simple phenols of dietary origin: Hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol. Drug Metab. Rev. 2016, 48, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karković Marković, A.; Torić, J.; Barbarić, M.; Jakobušić Brala, C. Hydroxytyrosol, Tyrosol and Derivatives and Their Potential Effects on Human Health. Molecules 2019, 24, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotronoulas, A.; Pizarro, N.; Serra, A.; Robledo, P.; Joglar, J.; Rubió, L.; Hernáez, Á.; Tormos, C.; Motilva, M.J.; Fitó, M.; et al. Dose-dependent metabolic disposition of hydroxytyrosol and formation of mercapturates in rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 77, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubió, L.; Macià, A.; Valls, R.M.; Pedret, A.; Romero, M.P.; Solà, R.; Motilva, M.-J. A new hydroxytyrosol metabolite identified in human plasma: Hydroxytyrosol acetate sulphate. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordán, M.; García-Acosta, N.; Espartero, J.L.; Goya, L.; Mateos, R. Hydroxytyrosol Bioavailability: Unraveling Influencing Factors and Optimization Strategies for Dietary Supplements. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiara, I.; Hervás Povo, B.; Alotaibi, W.; Young Tie Yang, P.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Globisch, D. Characterizing the Sulfated and Glucuronidated (Poly)phenol Metabolome for Dietary Biomarker Discovery. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 6702–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarewicz, M.; Drożdż, I.; Tarko, T.; Duda-Chodak, A. The Interactions between Polyphenols and Microorganisms, Especially Gut Microbiota. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, A.; Rubió, L.; Borràs, X.; Macià, A.; Romero, M.P.; Motilva, M.J. Distribution of olive oil phenolic compounds in rat tissues after administration of a phenolic extract from olive cake. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Santiago, M.; Fonollá, J.; Lopez-Huertas, E. Human absorption of a supplement containing purified hydroxytyrosol, a natural antioxidant from olive oil, and evidence for its transient association with low-density lipoproteins. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 61, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Almazan, M.; Pulido-Moran, M.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Ramirez-Tortosa, C.; Rodriguez-Garcia, C.; Quiles, J.L.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M. Hydroxytyrosol: Bioavailability, toxicity, and clinical applications. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products N and A (NDA). Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to polyphenols in olive and protection of LDL particles from oxidative damage (ID 1333, 1638, 1639, 1696, 2865), maintenance of normal blood HDL cholesterol concentrations (ID 1639), maintenance of normal blood pressure (ID 3781), “anti-inflammatory properties” (ID 1882), “contributes to the upper respiratory tract health” (ID 3468), “can help to maintain a normal function of gastrointestinal tract” (3779), and “contributes to body defences against external agents” (ID 3467) pursuant to Article 13 (1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2033. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, M.J.; Ahn, J.; Ha, T.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, Y.J.; Jung, C.H. Pharmacokinetics of Tyrosol Metabolites in Rats. Molecules 2016, 21, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriana, F.J.G.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Lucas, R.; Bermudez, B.; Jaramillo, S.; Morales, J.C.; Abia, R.; Lopez, S. Tyrosol and its metabolites as antioxidative and anti-inflammatory molecules in human endothelial cells. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2905–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, R.; Goya, L.; Bravo, L. Metabolism of the Olive Oil Phenols Hydroxytyrosol, Tyrosol, and Hydroxytyrosyl Acetate by Human Hepatoma HepG2 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 9897–9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López de las Hazas, M.C.; Piñol, C.; Macià, A.; Motilva, M.J. Hydroxytyrosol and the Colonic Metabolites Derived from Virgin Olive Oil Intake Induce Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6467–6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosele, J.I.; Martín-Peláez, S.; Macià, A.; Farràs, M.; Valls, R.M.; Catalán, Ú.; Motilva, M. Faecal microbial metabolism of olive oil phenolic compounds: In vitro and in vivo approaches. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, J.I.; Macià, A.; Motilva, M.J. Metabolic and Microbial Modulation of the Large Intestine Ecosystem by Non-Absorbed Diet Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Molecules 2015, 20, 17429–17468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.; Silva, A.F.R.; Resende, D.; Braga, S.S.; Coimbra, M.A.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Strategies to Broaden the Applications of Olive Biophenols Oleuropein and Hydroxytyrosol in Food Products. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaplana-Pérez, C.; Auñón, D.; García-Flores, L.A.; Gil-Izquierdo, A. Hydroxytyrosol and potential uses in cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and AIDS. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán-Jiménez, C.; Domínguez-Perles, R.; Medina, S.; Prgomet, I.; López-González, I.; Simonelli-Muñoz, A.; Campillo-Cano, M.; Auñón, D.; Ferreres, F.; Gil-Izquierdo, Á. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of hydroxytyrosol are dependent on the food matrix in humans. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de las Hazas, M.C.; Piñol, C.; Macià, A.; Romero, M.P.; Pedret, A.; Solà, R.; Rubió, L.; Motilva, M.-J. Differential absorption and metabolism of hydroxytyrosol and its precursors oleuropein and secoiridoids. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 22, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Z.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Yuan, L.M.; Xu, M.C.; Gu, J.K.; Jiang, H.D.; Yu, L.S.; Zeng, S. The regioselective glucuronidation of morphine by dimerized human UGT2B7, 1A1, 1A9 and their allelic variants. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbring, S.J.; Adjei, A.A.; Baer, J.L.; Jenkins, G.D.; Zhang, J.; Cunningham, J.M.; Schaid, D.J.; Weinshilboum, R.M.; Thibodeau, S.N. Human SULT1A1 gene: Copy number differences and functional implications. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morató, J.; Robledo, P.; Tanner, J.A.; Boronat, A.; Pérez-Mañá, C.; Oliver Chen, C.Y.; Tyndale, R.F.; de la Torre, R. CYP2D6 and CYP2A6 biotransform dietary tyrosol into hydroxytyrosol. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronat, A.; Mateus, J.; Soldevila-Domenech, N.; Guerra, M.; Rodríguez-Morató, J.; Varon, C.; Muñoz, D.; Barbosa, F.; Morales, J.C.; Gaedigk, A.; et al. Cardiovascular benefits of tyrosol and its endogenous conversion into hydroxytyrosol in humans. A randomized, controlled trial. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 143, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Lu, C.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Gut microbiota as an “invisible organ” that modulates the function of drugs. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 121, 109653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardona, F.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Tulipani, S.; Tinahones, F.J.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I. Benefits of polyphenols on gut microbiota and implications in human health. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Zang, G.; Zhang, L.; Shao, C.; Wang, Z. Gut Microbiota and Atherosclerosis-Focusing on the Plaque Stability. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 668532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moco, S.; Martin, F.P.J.; Rezzi, S. Metabolomics view on gut microbiome modulation by polyphenol-rich foods. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 4781–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, U.; Fernández-Quintela, A.; Milagro, F.I.; Aguirre, L.; Martínez, J.A.; Portillo, M.P. Impact of polyphenols and polyphenol-rich dietary sources on gut microbiota composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 9517–9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.; Valdés-Varela, L.; González, S.; Gueimonde, M.; De Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G. Nutrition and the gut microbiome in the elderly. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.; Arboleya, S.; Fernández-Navarro, T.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Gonzalez, S.; Gueimonde, M. Age-associated changes in gut microbiota and dietary components related with the immune system in adulthood and old age: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersin, S.; Vonaesch, P. Small intestinal microbiota: From taxonomic composition to metabolism. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Tsolis, R.M.; Bäumler, A.J. The microbiome and gut homeostasis. Science 2022, 377, eabp9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, M.K.; Winter, S.E. Nutrient acquisition strategies by gut microbes. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byndloss, M.X.; Olsan, E.E.; Rivera-Chávez, F.; Tiffany, C.R.; Cevallos, S.A.; Lokken, K.L.; Torres, T.P.; Byndloss, A.J.; Faber, F.; Gao, Y.; et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-γ signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science 2017, 357, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.J.; Zheng, L.; Campbell, E.L.; Saeedi, B.; Scholz, C.C.; Bayless, A.J.; Wilson, K.E.; Glover, L.E.; Kominsky, D.J.; Magnuson, A.; et al. Crosstalk between Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Epithelial HIF Augments Tissue Barrier Function. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, B.D.; Funabashi, M.; Adame, M.D.; Wang, Z.; Boktor, J.C.; Haney, J.; Wu, W.-L.; Rabut, C.; Ladinsky, M.S.; Hwang, S.-J.; et al. A gut-derived metabolite alters brain activity and anxiety behaviour in mice. Nature 2022, 602, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, H.; Haga, S.; Aoyama, Y.; Kiriyama, S. Short-chain fatty acids suppress cholesterol synthesis in rat liver and intestine. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rosa, S.L.; Ostrowski, M.P.; de Leon, A.V.P.; McKee, L.S.; Larsbrink, J.; Eijsink, V.G.; Lowe, E.C.; Martens, E.C.; Pope, P.B. Glycan processing in gut microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 67, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T.; et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.M.; Howitt, M.R.; Panikov, N.; Michaud, M.; Gallini, C.A.; Bohlooly, Y.M.; Glickman, J.N.; Garrett, W.S. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 2013, 341, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, M.T.; Cresci, G.A.M. The Immunomodulatory Functions of Butyrate. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 6025–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, J.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12204–12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.K.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Dietary fiber and SCFAs in the regulation of mucosal immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Yan, L.; Fang, L.; Fan, C.; Sun, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z. Possible immune mechanisms of gut microbiota and its metabolites in the occurrence and development of immune thrombocytopenia. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1426911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankararaman, S.; Noriega, K.; Velayuthan, S.; Sferra, T.; Martindale, R. Gut Microbiome and Its Impact on Obesity and Obesity-Related Disorders. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2023, 25, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, E.; Bayomy, H.; Mohammedsaledh, Z. The Role of Gut Microbiome in Obesity: A Systematic Review. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Geurts, L.; Hoyles, L.; Iozzo, P.; Kraneveld, A.D.; La Fata, G.; Miani, M.; Patterson, E.; Pot, B.; Shortt, C.; et al. The microbiota–gut–brain axis: Pathways to better brain health. Perspectives on what we know, what we need to investigate and how to put knowledge into practice. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Dey, S.; Kumar, Y.; Malviya, R.; Prajapati, B.G.; Chaiyasut, C. Probiotics as modulators of gut-brain axis for cognitive development. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1348297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Hamady, M.; Yatsunenko, T.; Cantarel, B.L.; Duncan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Sogin, M.L.; Jones, W.J.; Roe, B.A.; Affourtit, J.P.; et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 2009, 457, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Gewirtz, A.T. Gut microbiota, low-grade inflammation, and metabolic syndrome. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014, 42, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmor-Barkan, Y.; Bar, N.; Shaul, A.A.; Shahaf, N.; Godneva, A.; Bussi, Y.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Weinberger, A.; Shechter, A.; Chezar-Azerrad, C.; et al. Metabolomic and microbiome profiling reveals personalized risk factors for coronary artery disease. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromentin, S.; Forslund, S.K.; Chechi, K.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Chakaroun, R.; Nielsen, T.; Tremaroli, V.; Ji, B.; Prifti, E.; Myridakis, A.; et al. Microbiome and metabolome features of the cardiometabolic disease spectrum. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhê, F.F.; Varin, T.V.; Le Barz, M.; Desjardins, Y.; Levy, E.; Roy, D.; Marette, A. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Obesity-Linked Metabolic Diseases and Prebiotic Potential of Polyphenol-Rich Extracts. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; DuGar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.W.; Chen, H.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Yen, C.Y.; Lin, C.J.; Prajnamitra, R.P.; Chen, L.L.; Ruan, S.C.; Lin, J.H.; Lin, P.J.; et al. Loss of gut microbiota alters immune system composition and cripples postinfarction cardiac repair. Circulation 2019, 139, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalon, D.; Culver, R.N.; Grembi, J.A.; Folz, J.; Treit, P.V.; Shi, H.; Rosenberger, F.A.; Dethlefsen, L.; Meng, X.; Yaffe, E.; et al. Profiling the human intestinal environment under physiological conditions. Nature 2023, 617, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettinger, G.; MacDonald, K.; Reid, G.; Burton, J.P. The influence of the human microbiome and probiotics on cardiovascular health. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraszthy, V.I.; Zambon, J.J.; Trevisan, M.; Zeid, M.; Genco, R.J. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Hazen, S.L. Microbial modulation of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.F.; Chen, Y.H.; Liu, S.F.; Kao, H.L.; Wu, M.S.; Yang, K.C.; Wu, W.K. Mutual Interplay of Host Immune System and Gut Microbiota in the Immunopathology of Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimet, M.; Barrett, T.J.; Fisher, E.A. HDL and Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.D.; Hamp, T.J.; Reid, R.W.; Fischer, L.M.; Zeisel, S.H.; Fodor, A.A. Association between composition of the human gastrointestinal microbiome and development of fatty liver with choline deficiency. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatarek, P.; Kaluzna-Czaplinska, J. Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) in human health. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 301. [Google Scholar]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Sannino, A.; Toscano, E.; Giugliano, G.; Gargiulo, G.; Franzone, A.; Trimarco, B.; Esposito, G.; Perrino, C. Gut microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2948–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Cheng, A.; Song, B.; Zhao, M.; Xue, J.; Wang, A.; Dai, L.; Jing, J.; Meng, X.; Li, H.; et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide and stroke recurrence depends on ischemic stroke subtypes. Stroke 2022, 53, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, W.W.; Buffa, J.A.; Fu, X.; Britt, E.B.; Koeth, R.A.; Levison, B.S.; Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Prognostic value of choline and betaine depends on intestinal microbiota-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennema, D.; Phillips, I.R.; Shephard, E.A. Trimethylamine and trimethylamine N-oxide, a flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3)-mediated host-microbiome metabolic axis implicated in health and disease. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Zampino, M.; Moaddel, R.; Chen, T.K.; Tian, Q.; Ferrucci, L.; Semba, R.D. Plasma metabolites associated with chronic kidney disease and renal function in adults from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Metabolomics 2021, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M.; Witkowski, M.; Friebel, J.; Buffa, J.A.; Li, X.S.; Wang, Z.; Sangwan, N.; Li, L.; DiDonato, J.A.; Tizian, C.; et al. Vascular endothelial tissue factor contributes to trimethylamine N-oxide-enhanced arterial thrombosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2367–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugham, M.; Bellanger, S.; Leo, C.H. Gut-Derived Metabolite, Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in Cardio-Metabolic Diseases: Detection, Mechanism, and Potential Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.B.; Zhang, Y.; Boini, K.M.; Koka, S. High Mobility Group Box 1 Mediates TMAO-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seldin, M.M.; Meng, Y.; Qi, H.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Z.; Hazen, S.L.; Lusis, A.J.; Shih, D.M. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes vascular inflammation through signaling of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, M.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Zeng, A.; Shi, X.; Cheng, S.; Pan, B.; Zheng, L.; et al. Gut flora-dependent metabolite Trimethylamine-N-oxide accelerates endothelial cell senescence and vascular aging through oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 116, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, W.J.; Shi, J.Y.; Su, Y.L.; Liu, Y.C.; Wang, L.; Xiao, C.X.; Chen, C.; Lu, Q. The gut microbial metabolite phenylacetylglycine protects against cardiac injury caused by ischemia/reperfusion through activating β2AR. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 697, 108720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Vaziri, N.D.; Aslan, G.; Tarim, K.; Kanbay, M. Gut hormones and gut microbiota: Implications for kidney function and hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2016, 10, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkin, A.C.; Tontonoz, P. Transcriptional integration of metabolism by the nuclear sterol-activated receptors LXR and FXR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anto, L.; Blesso, C.N. Interplay between diet, the gut microbiome, and atherosclerosis: Role of dysbiosis and microbial metabolites on inflammation and disordered lipid metabolism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 105, 108991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubal, A.; Kiaf, B.; Beaudoin, L.; Cagninacci, L.; Rhimi, M.; Fruchet, B.; da Silva, J.; Corbett, A.J.; Simoni, Y.; Lantz, O.; et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells promote inflammation and intestinal dysbiosis leading to metabolic dysfunction during obesity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, F. Immunological Impact of Intestinal T Cells on Metabolic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 639902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, H.; Sharma, A.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Torres, R.; Tatebe, K.; Chmura, S.J.; et al. Suppression of local type I interferon by gut microbiota-derived butyrate impairs antitumor effects of ionizing radiation. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20201915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Park, J.; Kim, M. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids, T cells, and inflammation. Immune Netw. 2014, 14, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, C.; Fredholm, S.; Willerslev-Olsen, A.; Hansen, M.; Bonefeld, C.M.; Geisler, C.; Andersen, M.H.; Ødum, N.; Woetmann, A. Butyrate and propionate inhibit antigen-specific CD8+ T cell activation by suppressing IL-12 production by antigen-presenting cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, M.; Weigand, K.; Wedi, F.; Breidenbend, C.; Leister, H.; Pautz, S.; Adhikary, T.; Visekruna, A. Regulation of the effector function of CD8+ T cells by gut microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, M.; Riester, Z.; Baldrich, A.; Reichardt, N.; Yuille, S.; Busetti, A.; Klein, M.; Wempe, A.; Leister, H.; Raifer, H.; et al. Microbial short-chain fatty acids modulate CD8+ T cell responses and improve adoptive immunotherapy for cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, K.; Krautkramer, K.A.; Org, E.; Romano, K.A.; Kerby, R.L.; Vivas, E.I.; Mehrabian, M.; Denu, J.M.; BäcKhed, F.; Lusis, A.J.; et al. Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, L.A.; He, J.; Ogden, L.G.; Loria, C.M.; Whelton, P.K. Dietary fiber intake and reduced risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fushimi, T.; Suruga, K.; Oshima, Y.; Fukiharu, M.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Goda, T. Dietary acetic acid reduces serum cholesterol and triacylglycerols in rats fed a cholesterol-rich diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.S.; Anderson, J.W.; Bridges, S.R. Propionate inhibits hepatocyte lipid synthesis. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1990, 195, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.M.; De Souza, R.; Kendall, C.W.; Emam, A.; Jenkins, D.J. Colonic health: Fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 40, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghikia, A.; Zimmermann, F.; Schumann, P.; Jasina, A.; Roessler, J.; Schmidt, D.; Heinze, P.; Kaisler, J.; Nageswaran, V.; Aigner, A.; et al. Propionate attenuates atherosclerosis by immune-dependent regulation of intestinal cholesterol metabolism. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, N.; Vollmer, M.; Holtrop, G.; Farquharson, F.M.; Wefers, D.; Bunzel, M.; Duncan, S.H.; Drew, J.E.; Williams, L.M.; Milligan, G.; et al. Specific substrate-driven changes in human faecal microbiota composition contrast with functional redundancy in short-chain fatty acid production. ISME J. 2018, 12, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampa, A.; Silvi, S.; Fabiani, R.; Morozzi, G.; Orpianesi, C.; Cresci, A. Effects of different digestible carbohydrates on bile acid metabolism and SCFA production by human gut micro-flora grown in an in vitro semi-continuous culture. Anaerobe 2004, 10, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, J.G.; Chain, F.; Martín, R.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Courau, S.; Langella, P. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria. Microb. Cell Factories 2017, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geirnaert, A.; Calatayud, M.; Grootaert, C.; Laukens, D.; Devriese, S.; Smagghe, G.; De Vos, M.; Boon, N.; Van De Wiele, T. Butyrate-producing bacteria supplemented in vitro to Crohn’s disease patient microbiota increased butyrate production and enhanced intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Hao, W.; Zhu, H.; Liang, N.; He, Z.; Ma, K.Y.; Chen, Z.-Y. Structure-Specific Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Plasma Cholesterol Concentration in Male Syrian Hamsters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10984–10992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damodharan, K.; Lee, Y.S.; Palaniyandi, S.A.; Yang, S.H.; Suh, J.W. Preliminary probiotic and technological characterization of Pediococcus pentosaceus strain KID7 and in vivo assessment of its cholesterol-lowering activity. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, J.A.; Reimer, R.A. Effect of prebiotic fibre supplementation on hepatic gene expression and serum lipids: A dose-response study in JCR:LA-cp rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minois, N.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Madeo, F. Polyamines in aging and disease. Aging 2011, 3, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, S. Polyamine metabolism and transport in gut microbes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2022, 86, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Molina, B.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Lambertos, A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Peñafiel, R. Dietary and Gut Microbiota Polyamines in Obesity- and Age-Related Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Esparza, N.C.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Comas-Basté, O.; Toro-Funes, N.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Polyamines in Food. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, M.; Kitada, Y.; Naito, Y. Endothelial function is improved by inducing microbial polyamine production in the gut: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeun, J.; Kim, S.; Cho, S.Y.; Jun Hjin Park, H.J.; Seo, J.G.; Chung, M.J.; Lee, S.J. Hypocholesterolemic effects of Lactobacillus plantarum KCTC3928 by increased bile acid excretion in C57BL/6 mice. Nutrition 2010, 26, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, D.R.; Davies, T.S.; Moss, J.W.E.; Calvente, D.L.; Ramji, D.P.; Marchesi, J.R.; Pechlivanis, A.; Plummer, S.F.; Hughes, T.R. The anti-cholesterolaemic effect of a consortium of probiotics: An acute study in C57BL/6J mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, K.; Saadati, S.; Yari, Z.; Asbaghi, O.; Hezaveh, Z.S.; Mafi, D.; Hoseinian, P.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Hekmatdoost, A.; de Courten, B. Beneficial effects of probiotic and synbiotic supplementation on some cardiovascular risk factors among individuals with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A grade-assessed systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 182, 106288. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Aguirre, C.E.; Cortés-Martín, A.; Ávila-Gálvez, M.Á.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; Selma, M.V.; González-Sarrías, A.; Espín, J.C. Main drivers of (poly)phenol effects on human health: Metabolite production and/or gut microbiota-associated metabotypes? Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10324–10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowd, V.; Karim, N.; Shishir, M.R.I.; Xie, L.; Chen, W. Dietary polyphenols to combat the metabolic diseases via altering gut microbiota. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavel, T.; Henderson, G.; Engst, W.; Doré, J.; Blaut, M. Phylogeny of human intestinal bacteria that activate the dietary lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006, 55, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalán, Ú.; Rubió, L.; López de las Hazas, M.C.; Herrero, P.; Nadal, P.; Canela, N.; Pedret, A.; Motilva, M.; Solà, R. Hydroxytyrosol and its complex forms (secoiridoids) modulate aorta and heart proteome in healthy rats: Potential cardio-protective effects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2114–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasinetti, G.M.; Singh, R.; Westfall, S.; Herman, F.; Faith, J.; Ho, L. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Metabolism of Polyphenols as Characterized by Gnotobiotic Mice. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 63, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Santos, A.M.; Sugizaki, C.S.A.; Lima, G.C.; Naves, M.M.V. Prebiotic effect of dietary polyphenols: A systematic review. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 74, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomova, A.; Bukovsky, I.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Alwarith, J.; Barnard, N.D.; Kahleova, H. The effects of vegetarian and vegan diets on gut microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 447652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Daza, M.C.; Pulido-Mateos, E.C.; Lupien-Meilleur, J.; Guyonnet, D.; Desjardins, Y.; Roy, D. Polyphenol-Mediated Gut Microbiota Modulation: Toward Prebiotics and Further. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 689456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, J.F.; Okamoto, S.; Teruya, T.; Uema, T.; Ikematsu, S.; Shimabukuro, M.; Masuzaki, H. Extra-virgin olive oil and the gut-brain axis: Influence on gut microbiota, mucosal immunity, and cardiometabolic and cognitive health. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisi, M.L.E.; Lucarini, L.; Biffi, B.; Rafanelli, E.; Pietramellara, G.; Durante, M.; Vidali, S.; Provensi, G.; Madiai, S.; Gheri, C.F.; et al. Effect of Mediterranean diet enriched in high quality extra virgin olive oil on oxidative stress, inflammation and gut microbiota in obese and normal weight adult subjects. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farràs, M.; Martinez-Gili, L.; Portune, K.; Arranz, S.; Frost, G.; Tondo, M.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Modulation of the gut microbiota by olive oil phenolic compounds: Implications for lipid metabolism, immune system, and obesity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Romero, M.; Díez-Municio, M.; Moreno, F.J. Exploring the Impact of Olive-Derived Bioactive Components on Gut Microbiota: Implications for Digestive Health. Foods 2025, 14, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalkaya, G.; Venema, K.; Lucini, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Delmas, D.; Daglia, M.; De Filippis, A.; Xiao, H.; Quiles, J.L.; Xiao, J.; et al. Interaction of dietary polyphenols and gut microbiota: Microbial metabolism of polyphenols, influence on the gut microbiota, and implications on host health. Food Front. 2020, 1, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, M.; Rocchetti, G.; Ghisoni, S.; Giuberti, G.; Capanoglu, E.; Lucini, L. Effect of different soluble dietary fibres on the phenolic profile of blackberry puree subjected to in vitro gastrointestinal digestion and large intestine fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Giuberti, G.; Busconi, M.; Marocco, A.; Trevisan, M.; Lucini, L. Pigmented sorghum polyphenols as potential inhibitors of starch digestibility: An in vitro study combining starch digestion and untargeted metabolomics. Food Chem. 2020, 312, 126077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali Čepo, D.; Radić, K.; Turčić, P.; Anić, D.; Komar, B.; Šalov, M. Food (Matrix) Effects on Bioaccessibility and Intestinal Permeability of Major Olive Antioxidants. Foods 2020, 9, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, T. Dietary factors affecting polyphenol bioavailability. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzah, C.S. How to increase dietary polyphenol bioavailability: Understanding the roles of modulating factors, lifestyle and gut microbiota. Food Humanit. 2025, 4, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, N.; Laursen, M.F.; La Barbera, G.; Tsekitsidi, E.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Raes, J.; Licht, T.R.; Dragsted, L.O.; Roager, H.M. Gut physiology and environment explain variations in human gut microbiome composition and metabolism. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 3210–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankenfeld, C.L. O-desmethylangolensin: The importance of equol’s lesser known cousin to human health. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villalba, R.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Nevedomskaya, E.; Mayboroda, O.A.; Deelder, A.M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Exploratory analysis of human urine by LC–ESI-TOF MS after high intake of olive oil: Understanding the metabolism of polyphenols. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; González-Sarrías, A.; García-Villalba, R.; Núñez-Sánchez, M.A.; Selma, M.V.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Espín, J.C. Urolithins, the rescue of “old” metabolites to understand a “new” concept: Metabotypes as a nexus among phenolic metabolism, microbiota dysbiosis, and host health status. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1500901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, C.; Franch, O.; Fernández-Paredes, L.; Oreja-Guevara, C.; Núñez-Beltrán, M.; Comins-Boo, A.; Reale, M.; Sánchez-Ramón, S. Antiphospholipid antibodies overlapping in isolated neurological syndrome and multiple sclerosis: Neurobiological insights and diagnostic challenges. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, C.A.; Handler, N.; Heiss, E.H.; Erker, T.; Dirsch, V.M. No evidence for modulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by the olive oil polyphenol hydroxytyrosol in human endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 2007, 195, e58–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storniolo, C.E.; Roselló-Catafau, J.; Pintó, X.; Mitjavila, M.T.; Moreno, J.J. Polyphenol fraction of extra virgin olive oil protects against endothelial dysfunction induced by high glucose and free fatty acids through modulation of nitric oxide and endothelin-1. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalán, Ú.; López de Las Hazas, M.C.; Rubió, L.; Fernández-Castillejo, S.; Pedret, A.; de la Torre, R.; Motilva, M.-J.; Solà, R. Protective effect of hydroxytyrosol and its predominant plasmatic human metabolites against endothelial dysfunction in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 2523–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrougui, H.; Ikhlef, S.; Khalil, A. Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols Promote Cholesterol Efflux and Improve HDL Functionality. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 208062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perona, J.S.; Cabello-Moruno, R.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V. The role of virgin olive oil components in the modulation of endothelial function. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, S.M.; Thirunavukkarasu, M.; Penumathsa, S.V.; Paul, D.; Maulik, N. Akt/FOXO3a/SIRT1-Mediated Cardioprotection by n-Tyrosol against Ischemic Stress in Rat in Vivo Model of Myocardial Infarction: Switching Gears toward Survival and Longevity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9692–9698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Agli, M.; Maschi, O.; Galli, G.V.; Fagnani, R.; Dal Cero, E.; Caruso, D.; Bosisio, E. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by olive oil phenols via cAMP-phosphodiesterase. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, E.; de Castro, A.; Romero, C.; Brenes, M. Comparison of the concentrations of phenolic compounds in olive oils and other plant oils: Correlation with antimicrobial activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4954–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubdane, N.; Abdo, R.A.; Nguyen, M.; Bentourkia, M.; Turcotte, E.E.; Berrougui, H.; Fulop, T.; Khalil, A. High Tyrosol and Hydroxytyrosol Intake Reduces Arterial Inflammation and Atherosclerotic Lesion Microcalcification in Healthy Older Populations. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preedy, V.R.; Watson, R.R. Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Senoner, T.; Dichtl, W. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases: Still a therapeutic target? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Torre-Carbot, K.; Jauregui, O.; Gimeno, E.; Castellote, A.I.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; López-Sabater, M.C. Characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds in olive oils by solid-phase extraction, HPLC-DAD, and HPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4331–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitó, M.; Cladellas, M.; De La Torre, R.; Marti, J.; Alcántara, M.; Pujadas-Bastardes, M.; Marrugat, J.; Bruguera, J.; López-Sabater, M.C.; Vila, J.; et al. Antioxidant effect of virgin olive oil in patients with stable coronary heart disease: A randomized, crossover, controlled, clinical trial. Atherosclerosis 2005, 181, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, M.A.; Gualtieri, P.; Gratteri, S.; Ali, W.; Sergi, D.; Muscoli, S.; Cammarano, A.; Bernardini, S.; Di Renzo, L.; Romeo, F. Effects of postprandial hydroxytyrosol and derivates on oxidation of LDL, cardiometabolic state and gene expression: A nutrigenomic approach for cardiovascular prevention. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 20, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijakumaran, U.; Shanmugam, J.; Heng, J.W.; Azman, S.S.; Yazid, M.D.; Haizum Abdullah, N.A.; Sulaiman, N. Effects of Hydroxytyrosol in Endothelial Functioning: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabriso, N.; Gnoni, A.; Stanca, E.; Cavallo, A.; Damiano, F.; Siculella, L.; Carluccio, M.A. Hydroxytyrosol ameliorates endothelial function under inflammatory conditions by preventing mitochondrial dysfunction. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 9086947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozbek, N.; Bali, E.B.; Karasu, C. Quercetin and hydroxytyrosol attenuates xanthine/xanthine oxidase-induced toxicity in H9c2 cardiomyocytes by regulation of oxidative stress and stress-sensitive signaling pathways. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2015, 34, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Zrelli, H.; Matsuoka, M.; Kitazaki, S.; Zarrouk, M.; Miyazaki, H. Hydroxytyrosol reduces intracellular reactive oxygen species levels in vascular endothelial cells by upregulating catalase expression through the AMPK–FOXO3a pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 660, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.R.; Pernomian, L.; Bendhack, L.M. Contribution of oxidative stress to endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, M.; Ogura, Y.; Koya, D. The protective role of Sirt1 in vascular tissue: Its relationship to vascular aging and atherosclerosis. Aging 2016, 8, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrelli, H.; Kusunoki, M.; Miyazaki, H. Role of hydroxytyrosol-dependent regulation of HO-1 expression in promoting wound healing of vascular endothelial cells via Nrf2 de novo synthesis and stabilization. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J. The role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress-induced endothelial injuries. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 225, R83–R99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Duan, H.; Li, R.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling: An important molecular mechanism of herbal medicine in the treatment of atherosclerosis via the protection of vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 34, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonelli, C.; Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, M.; Kiani, A.K.; Paolacci, S.; Manara, E.; Kurti, D.; Dhuli, K.; Bushati, V.; Miertus, J.; Pangallo, D.; Baglivo, M.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol: A natural compound with promising pharmacological activities. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 309, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Martínez, M.S.; Truchado, P.; Castro-Ibáñez, I.; Allende, A. Antimicrobial activity of hydroxytyrosol: A current controversy. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Benedetto, R.; Varì, R.; Scazzocchio, B.; Filesi, C.; Santangelo, C.; Giovannini, C.; Matarrese, P.; D’ARchivio, M.; Masella, R. Tyrosol, the major extra virgin olive oil compound, restored intracellular antioxidant defences in spite of its weak antioxidative effectiveness. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2007, 17, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Hur, J.; Lee, Y.; Yoon, B.R.; Choi, S.Y. Protective Effects of Tyrosol Against Oxidative Damage in L6 Muscle Cells. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2018, 24, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Liu, M.; Ahmad, Z. Understanding the link between antimicrobial properties of dietary olive phenolics and bacterial ATP synthase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, L.; Ros, G.; Nieto, G. Hydroxytyrosol: Health benefits and use as functional ingredient in meat. Medicines 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, R.; Trovato Salinaro, A.; Cordaro, M.; Fusco, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Interdonato, L.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Crea, R.; Siracusa, R.; et al. Hidrox® and chronic cystitis: Biochemical evaluation of inflammation, oxidative stress, and pain. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, N.; Arnold, S.; Hoeller, U.; Kilpert, C.; Wertz, K.; Schwager, J. Hydroxytyrosol is the major anti-inflammatory compound in aqueous olive extracts and impairs cytokine and chemokine production in macrophages. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1890–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qin, Y.; Wan, X.; Liu, H.; Iv, C.; Ruan, W.; Lu, L.; He, L.; Guo, X. Hydroxytyrosol Plays Antiatherosclerotic Effects through Regulating Lipid Metabolism via Inhibiting the p38 Signal Pathway. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 5036572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuccelli, R.; Fabiani, R.; Rosignoli, P. Hydroxytyrosol Exerts Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidant Activities in a Mouse Model of Systemic Inflammation. Molecules 2018, 23, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonomidis, I.; Katogiannis, K.; Chania, C.; Iakovis, N.; Tsoumani, M.; Christodoulou, A.; Brinia, E.; Pavlidis, G.; Thymis, J.; Tsilivarakis, D.; et al. Association of hydroxytyrosol enriched olive oil with vascular function in chronic coronary disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.C.; Tomé-Carneiro, J.; Burgos-Ramos, E.; Loria Kohen, V.; Espinosa, M.I.; Herranz, J.; Visioli, F. One-week administration of hydroxytyrosol to humans does not activate Phase II enzymes. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 95–96, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Holvoet, S.; Mercenier, A. Dietary polyphenols in the prevention and treatment of allergic diseases. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persia, F.A.; Mariani, M.L.; Fogal, T.H.; Penissi, A.B. Hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein of olive oil inhibit mast cell degranulation induced by immune and non-immune pathways. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschelli, S.; De Cecco, F.; Pesce, M.; Ripari, P.; Guagnano, M.T.; Nuevo, A.B.; Grilli, A.; Sancilio, S.; Speranza, L. Hydroxytyrosol Reduces Foam Cell Formation and Endothelial Inflammation Regulating the PPARγ/LXRα/ABCA1 Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Huang, I.T.; Shih, H.J.; Chang, Y.Y.; Kao, M.C.; Shih, P.C.; Huang, C.J. Cluster of differentiation 14 and toll-like receptor 4 are involved in the anti-inflammatory effects of tyrosol. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 53, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Huang, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhuang, S.; Xu, L.; Song, B.; Xiong, Y.; Guan, S. Tyrosol exhibits negative regulatory effects on LPS response and endotoxemia. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 62, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Santiago, M.; Martín-Bautista, E.; Carrero, J.J.; Fonollá, J.; Baró, L.; Bartolomé, M.V.; Gil-Loyzaga, P.; López-Huertas, E. One-month administration of hydroxytyrosol, a phenolic antioxidant present in olive oil, to hyperlipemic rabbits improves blood lipid profile, antioxidant status and reduces atherosclerosis development. Atherosclerosis 2006, 188, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Huertas, E.; Fonolla, J. Hydroxytyrosol supplementation increases vitamin C levels in vivo. A human volunteer trial. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoditti, E.; Calabriso, N.; Massaro, M.; Pellegrino, M.; Storelli, C.; Martines, G.; De Caterina, R.; Carluccio, M.A. Mediterranean diet polyphenols reduce inflammatory angiogenesis through MMP-9 and COX-2 inhibition in human vascular endothelial cells: A potentially protective mechanism in atherosclerotic vascular disease and cancer. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 527, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurylowicz, A.; Jonas, M.; Lisik, W.; Jonas, M.; Wicik, Z.A.; Wierzbicki, Z.; Chmura, A.; Puzianowska-Kuznicka, M. Obesity is associated with a decrease in expression but not with the hypermethylation of thermogenesis-related genes in adipose tissues. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanon, B.; Colitti, M. Original Research: Hydroxytyrosol, an ingredient of olive oil, reduces triglyceride accumulation and promotes lipolysis in human primary visceral adipocytes during differentiation. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1796–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagla, I.; Benaki, D.; Baira, E.; Lemonakis, N.; Poudyal, H.; Brown, L.; Tsarbopoulos, A.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Mikros, E.; Gikas, E. Alteration in the liver metabolome of rats with metabolic syndrome after treatment with Hydroxytyrosol. A Mass Spectrometry And Nuclear Magnetic Resonance-based metabolomics study. Talanta 2018, 178, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wen, D. Hydroxytyrosol ameliorates insulin resistance by modulating endoplasmic reticulum stress and prevents hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obesity mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 57, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illesca, P.; Valenzuela, R.; Espinosa, A.; Echeverría, F.; Soto-Alarcon, S.; Ortiz, M.; Videla, L.A. Hydroxytyrosol supplementation ameliorates the metabolic disturbances in white adipose tissue from mice fed a high-fat diet through recovery of transcription factors Nrf2, SREBP-1c, PPAR-γ and NF-κB. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 2472–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigacci, S.; Stefani, M. Nutraceutical Properties of Olive Oil Polyphenols. An Itinerary from Cultured Cells through Animal Models to Humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamden, K.; Allouche, N.; Jouadi, B.; El-Fazaa, S.; Gharbi, N.; Carreau, S.; Damak, M.; Elfeki, A. Inhibitory action of purified hydroxytyrosol from stored olive mill waste on intestinal disaccharidases and lipase activities and pancreatic toxicity in diabetic rats. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 19, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramohan, R.; Pari, L. Anti-inflammatory effects of tyrosol in streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 27, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Im, S.W.; Jung, C.H.; Jang, Y.J.; Ha, T.Y.; Ahn, J. Tyrosol, an olive oil polyphenol, inhibits ER stress-induced apoptosis in pancreatic β-cell through JNK signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 469, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priore, P.; Siculella, L.; Gnoni, G.V. Extra virgin olive oil phenols down-regulate lipid synthesis in primary-cultured rat-hepatocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumuzachi, O.; Kieserling, H.; Rohn, S.; Mocan, A. The impact of oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and tyrosol on cardiometabolic risk factors: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 6898–6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Velasco, M.; Esperanza Díaz, L.; Lucas, R.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Bastida, S.; Marcos, A.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J. Effects of hydroxytyrosol-enriched sunflower oil consumption on CVD risk factors. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 1448–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bock, M.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Brennan, C.M.; Biggs, J.B.; Morgan, P.E.; Hodgkinson, S.C.; Hofman, P.L.; Cutfield, W.S. Olive (Olea europaea L.) leaf polyphenols improve insulin sensitivity in middle-aged overweight men: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, R.; Possemiers, S.; Heyerick, A.; Pinheiro, I.; Raszewski, G.; Davicco, M.J.; Coxam, V. Twelve-month consumption of a polyphenol extract from olive (Olea europaea) in a double blind, randomized trial increases serum total osteocalcin levels and improves serum lipid profiles in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colica, C.; Di Renzo, L.; Trombetta, D.; Smeriglio, A.; Bernardini, S.; Cioccoloni, G.; De Miranda, R.C.; Gualtieri, P.; Salimei, P.S.; De Lorenzo, A. Antioxidant Effects of a Hydroxytyrosol-Based Pharmaceutical Formulation on Body Composition, Metabolic State, and Gene Expression: A Randomized Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 2473495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, S.; Rowland, I.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Yaqoob, P.; Stonehouse, W. Impact of phenolic-rich olive leaf extract on blood pressure, plasma lipids and inflammatory markers: A randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, R.; Fujie, K.; Yuine, N.; Watabe, Y.; Nakata, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Isoda, H.; Hashimoto, K. Olive leaf tea is beneficial for lipid metabolism in adults with prediabetes: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Res. 2019, 67, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conterno, L.; Martinelli, F.; Tamburini, M.; Fava, F.; Mancini, A.; Sordo, M.; Pindo, M.; Martens, S.; Masuero, D.; Vrhovsek, U.; et al. Measuring the impact of olive pomace enriched biscuits on the gut microbiota and its metabolic activity in mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Scavone, F.; Bellumori, M.; Cecchi, L.; Nediani, C.; Maggini, N.; Sofi, F.; Giovannelli, L.; Mulinacci, N. Effects of an Olive By-Product Called Pâté on Cardiovascular Risk Factors. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2021, 40, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Y.; Winkens, B.; Jonkers, D.; Masclee, A. The effect of olive leaf extract on cardiovascular health markers: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fytili, C.; Nikou, T.; Tentolouris, N.; Tseti, I.K.; Dimosthenopoulos, C.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Simos, D.; Kokkinos, A.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Katsilambros, N.; et al. Effect of Long-Term Hydroxytyrosol Administration on Body Weight, Fat Mass and Urine Metabolomics: A Randomized Double-Blind Prospective Human Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horcajada, M.N.; Beaumont, M.; Sauvageot, N.; Poquet, L.; Saboundjian, M.; Costes, B.; Verdonk, P.; Brands, G.; Brasseur, J.; Urbin-Choffray, D.; et al. An oleuropein-based dietary supplement may improve joint functional capacity in older people with high knee joint pain: Findings from a multicentre-RCT and post hoc analysis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2022, 14, 1759720X211070205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binou, P.; Stergiou, A.; Kosta, O.; Tentolouris, N.; Karathanos, V.T. Positive contribution of hydroxytyrosol-enriched wheat bread to HbA1c levels, lipid profile, markers of inflammation and body weight in subjects with overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, Á.; Álvarez-Soria, M.J.; Aranda-Villalobos, P.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.M.; Martínez-Lara, E.; Siles, E. Hydroxytyrosol, a Promising Supplement in the Management of Human Stroke: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatrice, M.; Lasfar, A.; van Kalkeren, C.A.J.; Troost, F. Olive Leaf Extract Supplementation Improves Postmenopausal Symptoms: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Parallel Study on Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinckaers, P.J.; Petrick, H.L.; Horstman, A.M.; Moreno-Asso, A.; De Marchi, U.; Hendriks, F.K.; Kuin, L.M.; Fuchs, C.J.; Grathwohl, D.; Verdijk, L.B.; et al. Oleuropein Supplementation Increases Resting Skeletal Muscle Fractional Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Activity but Does Not Influence Whole-Body Metabolism: A Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Trial in Healthy, Older Males. J. Nutr. 2025, 155, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratilla-Rivera, I.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Ramos, S.; Portillo, M.P.; Martín, M.Á.; Mateos, R. Hydroxytyrosol supplementation improves antioxidant and anti-inflammatory status in individuals with overweight and prediabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel trial. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 52, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidari, F.; Mohammad-shahi, M.; Jalali, M.T.; Ahmadi-Angali, K.; Shayesteh, F. Phenolic-rich extract of olive leaf with a hypocaloric diet alleviates oxidative stress in obese females: A randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Senizza, B.; Giuberti, G.; Montesano, D.; Trevisan, M.; Lucini, L. Metabolomic study to evaluate the transformations of extra-virgin olive oil’s antioxidant phytochemicals during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Lde, L.; Costa, G.R.; Dörr, F.A.; Ong, T.P.; Pinto, E.; Lajolo, F.M.; Hassimotto, N.M.A. Potential antiproliferative activity of polyphenol metabolites against human breast cancer cells and their urine excretion pattern in healthy subjects following acute intake of a polyphenol-rich juice of grumixama (Eugenia brasiliensis Lam.). Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2266–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreli, G.; Deiana, M. Biological relevance of extra virgin olive oil polyphenols metabolites. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, S.; Pochard, C.; Diounou, H.; Castillo, V.; Divoux, J.; Alcantara, J.; Leclerc, J.; Guilmeau, S.; Huet, C.; Charifi, W.; et al. Deletion of intestinal epithelial AMP-activated protein kinase alters distal colon permeability but not glucose homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 2021, 47, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Abdullah Tian, W.; Qiu, Z.; Song, M.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, J. Hydroxytyrosol Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Modulating Inflammatory Responses, Intestinal Barrier, and Microbiome. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, R.; Fuccelli, R.; Pieravanti, F.; De Bartolomeo, A.; Morozzi, G. Production of hydrogen peroxide is responsible for the induction of apoptosis by hydroxytyrosol on HL60 cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Cui, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wurtz, K.; Weber, P.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol promotes superoxide production and defects in autophagy leading to anti-proliferation and apoptosis on human prostate cancer cells. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2013, 13, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T. Possible Side Effects of Polyphenols and Their Interactions with Medicines. Molecules 2023, 28, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.A.G.; López-Villodres, J.A.; Asensi, R.; Espartero, J.L.; Rodríguez-Gutiérez, G.; De La Cruz, J.P. Virgin olive oil polyphenol hydroxytyrosol acetate inhibits in vitro platelet aggregation in human whole blood: Comparison with hydroxytyrosol and acetylsalicylic acid. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]