Abstract

Background/Objectives: One of the main reasons for discrepancies in the role of vitamin D in ART could be the measurement of the conventional biomarker 25(OH)D3. It is known that this value is affected by multiple factors, such as tissue origin, assay variability, classification criteria, and potential storage-related degradation. In this study, we investigate 24,25(OH)2D3 as a new biomarker to improve vitamin D assessment in women’s reproductive health, particularly regarding oocyte development. Methods: A prospective cohort study including 35 oocyte donors undergoing controlled ovarian stimulation, who were recruited between October and November 2017, was conducted. Vitamin D metabolites were measured at the baseline and after seven months of storage at −80 °C. Paired serum and pooled follicular fluid (FF) samples were collected at oocyte retrieval. 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 were quantified by ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS). Statistical analyses included paired tests (serum vs. FF; baseline vs. stored) and Pearson’s correlations (two-sided α = 0.05). Results: At the baseline, the mean serum 25(OH)D3 concentration was 91.56 ± 39.01 nmol/L and the mean FF concentration was 58.13 ± 19.55 nmol/L (p < 0.0001). Serum 24,25(OH)2D3 averaged 15.62 ± 10.99 nmol/L, compared with 11.26 ± 6.09 nmol/L in FF (p = 0.004). In both fluids, 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 were strongly correlated (serum R2 = 0.92; FF R2 = 0.91). Across fluids, the serum–FF correlation was stronger for 24,25(OH)2D3 (R2 = 0.77, p <0.0001) than for 25(OH)D3 (R2 = 0.69, p < 0.0001). After seven months of storage, 25(OH)D3 concentrations decreased significantly (serum −32%; FF −38%; both p < 0.0001), whereas 24,25(OH)2D3 levels remained stable (serum p = 0.24; FF p = 0.36). Conclusions: Serum 24,25(OH)2D3 is a more reliable and minimally invasive biomarker for assessing ovarian vitamin D status than the current gold standard, 25(OH)D3. Incorporating this metabolite into research studies and storage quality control may improve the reliability of retrospective analyses based on cryopreserved material, contributing to a better understanding of the role of vitamin D in human reproduction.

1. Background

Vitamin D is a secosteroid hormone that becomes biologically active as 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) after sequential hydroxylations in the liver and kidney. Beyond calcium and phosphate homeostasis, its multiple effects are mediated through the vitamin D receptor, which is expressed in a broad range of tissues, including the ovary, endometrium, placenta, and testis [1,2,3,4]. In the context of female reproductive health, a recent narrative review [5] highlighted that vitamin D status influences multiple processes, including regulation of the menstrual cycle through steroidogenesis [6,7,8], and luteal function, thereby affecting progesterone production [9]. Adequate vitamin D levels have been associated with improved ovarian stimulation response [10] and enhanced fertility outcomes in in vitro fertilization (IVF) [11]. Conversely, vitamin D deficiency has been linked to pregnancy-related complications, such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, and preterm labour [12], as well as reproductive disorders, including infertility, endometriosis, and polycystic ovarian syndrome [13]. However, findings remain inconsistent when 25(OH)D levels are assessed in follicular fluid. Some studies reported no association between vitamin D concentrations in follicular fluid and IVF outcomes such as fertilization rate or embryo quality [14,15,16], whereas others found significant positive correlations between FF 25(OH)D levels and oocyte or embryo quality [17,18]. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent worldwide and has been frequently reported in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) [19,20,21]. While insufficient sun exposure and poor dietary intake are clear contributors [22], part of this apparent deficiency may be explained by methodological issues in vitamin D measurement. The most abundant circulating metabolite, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), is the conventional biomarker for assessing vitamin D status [23,24] and to establish supplementation regimens [25]. However, immunoassay-based quantification of 25(OH)D has been shown to present substantial bias—up to 30%—and inter-laboratory variability as high as 15% [26,27,28,29]. Furthermore, discrepancies between biochemical results and clinical phenotypes have been observed: African American populations often present with low serum 25(OH)D yet show low fracture risk [30,31], and individuals with normal parathyroid hormone levels may also present with low 25(OH)D [32]. Such inconsistencies call into question the accuracy of 25(OH)D as a universal marker of vitamin D status.

Other candidate markers, such as free or bioavailable 25(OH)D, have been proposed; however their interpretation is complicated by polymorphisms in the vitamin D-binding protein, which influence ligand binding and assay performance [33]. In addition, pre-analytical factors, including light exposure, freeze–thaw cycles, and storage duration, can alter measured concentrations, yet are not uniformly controlled. Many studies rely on stored serum and follicular fluid, often cryopreserved or lacking detailed information on storage conditions and processing times. Early studies had already warned about stability issues for vitamin D metabolites [34], and more recent data have reinforced concerns regarding storage-related changes in 25(OH)D [35].

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) has therefore emerged as the reference method to address these issues [36,37], with a reported bias of below 5% and coefficients of variation around 10%, consistent with standards from the Vitamin D Standardization Program [38]. Unlike immunoassays, LC–MS/MS avoids interference from protein binding and cross-reactivity with other vitamin D metabolites, thereby offering greater accuracy and comparability [39]. Nevertheless, inconsistencies in defining sufficiency thresholds, namely ≥50 nmol/L according to the Institute of Medicine [40] and >75 nmol/L by the Endocrine Society [41], further complicate interpretation and may explain conflicting reports regarding reproductive outcomes. Moreover, these cut-offs were established primarily to ensure bone health in the general population, without specifically addressing reproductive health or considering potential sex- or age-related differences. Recent updates from the Endocrine Society (2024) further emphasize that vitamin D sufficiency thresholds cannot be universally applied across populations, tissues, or physiological contexts, reinforcing the need for tissue-specific biomarkers, such as 24,25(OH)2D3, in reproductive research [42].

Among alternative biomarkers, 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (24,25(OH)2D) has attracted increasing interest. This metabolite, produced through Cytochrome P450 Family 24 Subfamily A Member 1 (CYP24A1)-mediated hydroxylation of 25(OH)D, represents the principal catabolic pathway of vitamin D [43]. Its synthesis in reproductive tissues, such as the human decidua and placenta, was already demonstrated by Weisman et al. (1979) [1], suggesting a potential physiological role in reproductive processes. Both its absolute concentration and the 24,25(OH)2D:25(OH)D ratio have been proposed as functional indices of vitamin D status, measurable only by LC–MS/MS. While systemic studies have validated serum 24,25(OH)2D as an accurate indicator of vitamin D metabolism [44], its behaviour in the ovary—particularly in follicular fluid—and its stability during long-term storage remain poorly characterised.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

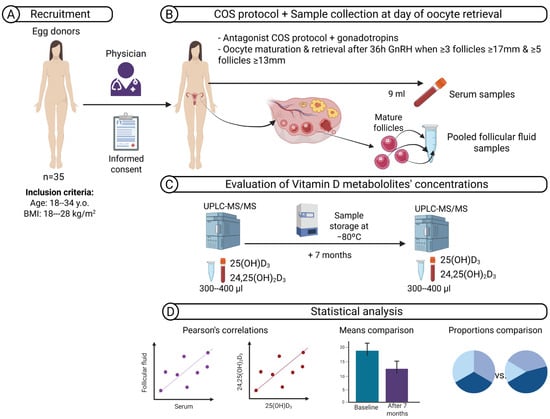

The study is schematised in Figure 1 and was designed to investigate whether serum 24,25(OH)2D3 provides a more reliable reflection of ovarian vitamin D status than 25(OH)D3, using paired serum and follicular fluid samples. Because reproductive research frequently relies on cryopreserved and stored material, we also examined the stability of both metabolites after prolonged storage at −80 °C to assess their reliability as biomarkers in studies based on stored samples.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the study workflow. (A) A cohort including 35 healthy women who met the criteria for oocyte donation was recruited. (B) Controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) was performed using antagonist protocols until criteria for triggering oocyte maturation were met. On the day of oocyte retrieval, paired serum and pooled follicular fluid (FF) samples were collected. (C) Vitamin D metabolites—25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25(OH)2D3)—were quantified by ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) at baseline and after seven months of storage at −80 °C. (D) Statistical analyses included Pearson’s correlations and means and proportions comparisons. Abbreviations: y.o., years old; BMI, body mass index; COS, controlled ovarian stimulation; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone; UPLC–MS/MS, ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.

This was a prospective cohort study including 35 healthy women who met the criteria for oocyte donation. Recruitment took place in autumn, between October and November 2017. Inclusion criteria were ages 18–34 years and a body mass index (BMI) of 18–28 kg/m2 (Figure 1A). All women underwent controlled ovarian stimulation using a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) antagonist protocol with recombinant or urinary follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), human menopausal gonadotrophin, or a combination, at doses determined by the treating physician. Final oocyte maturation was triggered with a GnRH agonist when ≥3 follicles of ≥17 mm and ≥5 follicles of ≥13 mm were observed. On the day of oocyte retrieval, 9 mL of peripheral blood was collected before follicular aspiration. Samples were immediately placed in light-protected tubes to prevent degradation, as indicated by previous reports [34]. After centrifugation (1500–2000× g, 10 min), serum was aliquoted. Follicular fluid from mature follicles was pooled per donor, centrifuged to remove cells, and aliquoted under the same conditions. (Figure 1B). All serum and follicular fluid (FF) samples were frozen at −80 °C until analysis. Baseline analyses were performed within one month after sample collection. A second measurement was performed after seven months of storage at −80 °C (Figure 1C). Finally, different statistical analyses were performed to assess correlations between metabolite values in serum and FF and between them. In addition, mean concentrations and different vitamin D classifications were compared (Figure 1D).

2.2. Measurement of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Concentration and Classification of Vitamin D Status

Serum and FF concentrations of 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 were measured by ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS), as previously described [36,37]. Internal standards (25-hydroxyvitamin D3-d6 and (24R),24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-d6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) were used. The same samples were re-analysed after seven months of storage at −80 °C (Figure 1C).

Serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations were classified according to two clinical guidelines: the Institute of Medicine (IOM) thresholds [40], defining sufficiency as ≥50 nmol/L, insufficiency as 30–50 nmol/L, and deficiency as <30 nmol/L, and the Endocrine Society criteria [41], defining sufficiency as ≥75 nmol/L, insufficiency as 50–75 nmol/L, and deficiency as <50 nmol/L.

These classifications were used to compare the distribution of vitamin D status in the cohort and to evaluate potential discrepancies between both systems after sample storage.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Paired t-tests were applied to compare serum vs. FF concentrations and baseline vs. stored values. Pearson’s correlations were calculated for metabolite associations. Kappa’s agreement coefficient was estimated using the vcd R package (version 1.4.8) [45] to assess concordance between the two classification systems. Agreement values were interpreted as follows: none (0–0.20), minimal (0.21–0.39), weak (0.40–0.59), moderate (0.60–0.79), strong (0.80–0.90), and almost perfect (>0.90) [46]. Fisher’s exact test was applied to evaluate the difference in classifications for serum 25(OH)D3 between the baseline and after seven months at −80 °C. All statistical analyses were performed using paired comparisons between serum and follicular fluid samples obtained from the same participants, along with before and after long-term storage, ensuring the removal of inter-individual variability and enhancing the power to detect intra-individual differences. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were performed using R version 4.4.3 [47] (Figure 1D).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

Of the 35 oocyte donors initially recruited, one was excluded due to technical failure in serum vitamin D measurement, leaving 34 women for analysis. The cohort presented a mean age of 25.4 ± 4.6 years and a mean BMI of 22.9 ± 2.7 kg/m2. The ovarian response to stimulation has an average of 28.2 ± 11.1 follicles aspirated and 23.3 ± 9.1 mature oocytes retrieved. Additional cycle characteristics, including menstrual cycle length, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels, and stimulation duration and hormone values on the day of triggering, are shown in Table 1. These results confirm that the study population represented a group of healthy young women with normal ovarian function and without clinical confounders.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

3.2. Serum Vitamin D Metabolites as Biomarkers of Follicular Fluid Concentrations

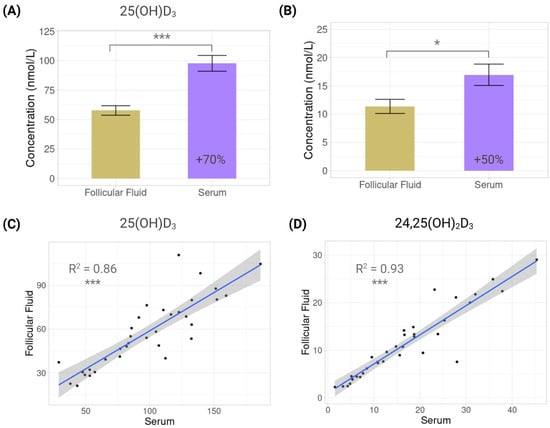

At the baseline, serum concentrations of 25(OH)D3 were significantly higher than those in follicular fluid (97.7 ± 39.0 vs. 57.7 ± 23.7 nmol/L, p < 0.0001), with serum levels 69.3% higher than FF levels (Figure 2A). A similar pattern was observed for 24,25(OH)2D3, with serum levels at 16.96 ± 11.0 nmol/L and FF at 11.3 ± 7.3 nmol/L (p = 0.0165) and with serum levels that were 49.1% higher than FF levels (Figure 2B). Finally, concentrations of 25(OH)D3 were 5.7 and 5.1 times higher than 24,25(OH)2D3 in serum and follicular fluid, respectively.

Figure 2.

Vitamin D metabolites in serum and follicular fluid. Bar plots showing mean concentration differences of vitamin D metabolites in serum and follicular fluid: (A) 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3); (B) 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25(OH)2D3). Scatterplots showing correlations between serum and follicular fluid: (C) 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3); (D) 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25(OH)2D3). Each dot represents one individual (n = 34). Regression line with 95% confidence interval is displayed. *: p < 0.05; ***: p < 0.001.

Despite these differences, cross-fluid correlations showed that serum values were predictive of FF concentrations, but the relationship was stronger for 24,25(OH)2D3 (R2 = 0.93, p < 0.0001) than for 25(OH)D3 (R2 = 0.86, p < 0.0001) (Figure 2C,D).

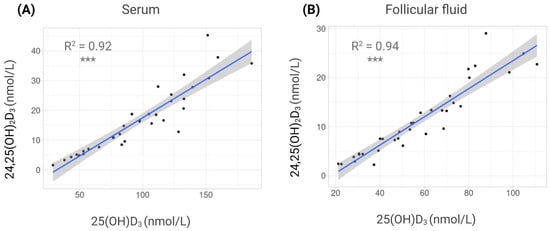

Finally, both metabolites were strongly correlated in each fluid, showing the same tendency: in serum, R2 = 0.92 (p < 0.0001), and in FF, R2 = 0.94 (p < 0.0001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlations between vitamin D metabolites in different fluids. Scatterplots showing correlations between 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25(OH)2D3) concentrations. (A) Serum. (B) Follicular fluid (FF). Each dot represents one individual. Regression line with 95% confidence interval is displayed. ***: p < 0.001.

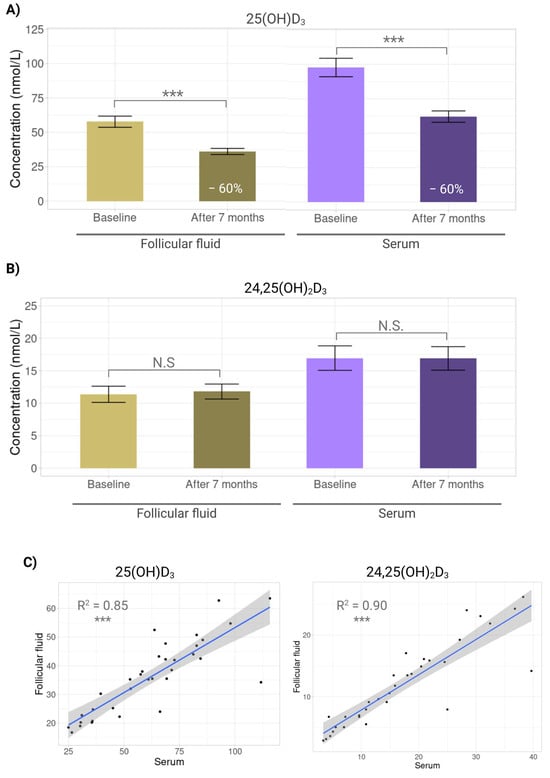

3.3. Effect of Long-Term Storage on Vitamin D Metabolite Levels

After seven months at −80 °C, concentrations of 25(OH)D3 declined markedly in both fluids. In FF, levels fell significantly from 57.7 ± 23.7 to 36.1 ± 12.9 nmol/L (p < 0.0001), which represents a decrease of 59.8%, and in serum, from 97.7 ± 39.0 to 62.1 ± 24.1 nmol/L (p < 0.0001), which represents a decrement of 57.5% (Figure 4A). By contrast, 24,25(OH)2D3 remained stable, with no significant changes in FF (11.4 ± 7.3 vs. 11.8 ± 6.8 nmol/L, p = 0.8043) or serum (17.0 ± 11.0 vs. 16.9 ± 10.6 nmol/L, p = 0.9825) (Figure 4B). These findings confirm that 25(OH)D3 is storage-sensitive, whereas 24,25(OH)2D3 is robustly stable. Despite the decline in 25(OH)D3, post-storage cross-fluid correlations remained high for both metabolites (25(OH)D3 R2 = 0.85, p < 0.0001; 24,25(OH)2D3 R2 = 0.90, p < 0.0001) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Effect of long-term storage on vitamin D metabolites. Bar plots showing mean concentration differences of vitamin D metabolites in serum and follicular fluid at baseline and after seven months storage at −80 °C. (A) 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3). (B) 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25(OH)2D3). (C) Scatterplots showing correlations between serum and follicular fluid for 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25(OH)2D3) after 7 months storage at −80 °C. N.S: No significant (p > 0.05); ***: p < 0.001.

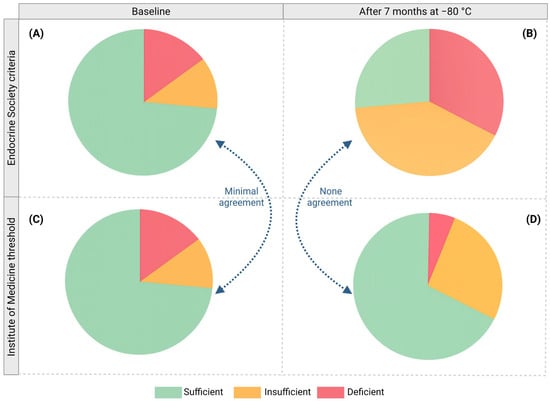

3.4. Inconsistency in Conventional Vitamin D Status Classification

When the baseline serum 25(OH)D3 was classified using the Endocrine Society criteria, most women (73.53%) were sufficient, 11.76% insufficient, and 14.71% deficient. In contrast, according to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) thresholds, most women (85.29%) were sufficient, 11.76% insufficient, and 2.94% deficient. These two classifications showed minimal agreement (Kappa value = 0.3369), illustrating how the choice of classification system substantially alters the apparent prevalence of sufficiency when applied to the same cohort.

These differences were more noticeable when serum 25(OH)D3 was evaluated after seven months at −80 °C. According to the Endocrine Society criteria, 26.47% of women were sufficient, 41.18% insufficient, and 32.35% deficient, while according to the IOM thresholds, most women remained sufficient (67.65%), 26.47% insufficient, and 5.88% deficient. Therefore, after seven months at −80 °C, both classifications showed no agreement (Kappa value = 0.0237) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Inconsistency of conventional vitamin D status classification. Classification of serum 25(OH)D3 levels according to two different systems: Endocrine Society criteria (A,B) and Institute of Medicine (IOM) thresholds (C,D) at baseline (A,C) and after seven months of storage at −80 °C (B,D). Both classifications were compared according to their Kappa value.

Furthermore, the proportions of both serum 25(OH)D3 classifications were significantly different between the baseline and after seven months at −80 °C (IOM thresholds: p = 0.0005; Endocrine Society criteria: p < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

This work highlights the problem of vitamin D measurement in women’s reproductive health and, in particular, provides evidence of a more reliable vitamin D biomarker for ovarian research. In this study, we found that the serum concentration of the proposed vitamin D metabolite, 24,25(OH)2D3, correlated more strongly with follicular fluid (FF) concentrations than did 25(OH)D3, the current gold standard, and that 24,25(OH)2D3 remained stable after long-term storage at −80 °C, whereas 25(OH)D3 decreased significantly. Taken together, these findings suggest that 24,25(OH)2D3, the proposed vitamin D metabolite, may serve as a more reliable indicator of ovarian vitamin D status than 25(OH)D3, especially when analyses are performed on stored samples.

The association between vitamin D and reproductive outcomes has been the focus of considerable debate. Some studies and meta-analyses have reported higher clinical pregnancy or live birth rates among women with sufficient vitamin D levels [21,48,49,50,51], whereas findings from other studies did not support a significant association [49,52,53,54,55,56]. Such conflicting results have fuelled ongoing controversy regarding the clinical relevance of vitamin D in ART. Several explanations have been proposed for these discrepancies, including differences in study populations, variable adjustment for confounders, and—importantly—heterogeneity in how vitamin D status is measured. Immunoassay-based quantification of 25(OH)D3 is prone to matrix effects, cross-reactivity, and inter-laboratory variability [37,57]. In addition, cut-offs applied to define sufficiency differ between guidelines: the Institute of Medicine [40] proposes ≥50 nmol/L, while the Endocrine Society recommends >75 nmol/L [41]. As shown in our data, prevalence estimates of deficiency and sufficiency change markedly depending on which threshold is used, and this lack of agreement is more noticeable after long-term storage at −80 °C. This variability illustrates the limitations of relying solely on serum 25(OH)D3 for classification in both clinical and research contexts. Standardisation initiatives have attempted to address these classification issues. Large population-based surveys applying liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) and aligned with the Vitamin D Standardisation Program have consistently reported higher mean serum 25(OH)D levels and lower prevalence of deficiency than studies relying on immunoassays [22,58,59,60]. These findings suggest that vitamin D deficiency may have been systematically overestimated. Our results add another layer to this problem by showing that 25(OH)D3 is also highly sensitive to cryopreservation and long-term storage, declining by approximately one third in both serum and follicular fluid after seven months at −80 °C. This raises the possibility that at least part of the variability in the literature, much of which is based on the use of stored samples, may be due to differences in pre-analytical handling and storage conditions.

By contrast, 24,25(OH)2D3 demonstrated remarkable stability, with minimal changes observed after the same storage interval. Its stronger serum–FF correlation further indicates that it may more faithfully represent ovarian vitamin D status and can be measured through a minimally invasive approach. Biologically, this is plausible: 24,25(OH)2D3 is the principal catabolic product of 25(OH)D3 via CYP24A1 and is therefore tightly linked to systemic vitamin D metabolism [39,43,61]. Its stability may reflect differences in molecular susceptibility to degradation during storage, while its tighter coupling with follicular fluid could relate to its role as a functional readout of enzymatic activity rather than absolute substrate concentration. Genetic variation in vitamin D binding protein can further influence metabolite distribution, and metabolites less dependent on binding dynamics may provide more reproducible measures across individuals. It is important to note that the present study was not intended to validate a new analytical method, as both 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 were measured using an already established LC–MS/MS platform. Instead, our work aimed to identify and propose 24,25(OH)2D3 as a more stable and reliable biomarker of vitamin D status for reproductive research. Future population-based studies will be required to establish reference ranges and assess its predictive value for reproductive outcomes.

The importance of storage effects on vitamin D metabolites was recently highlighted by Ko et al., 2025 [35], who demonstrated that serum 25(OH)D concentrations decrease significantly after storage at −80 °C. Their study raised the concern that a misclassification of vitamin D status could occur in research based on archived samples. Our data are consistent with these findings and extend them by showing that declines also occur in follicular fluid—an ovarian compartment directly relevant to oocyte development—and by demonstrating that 24,25(OH)2D3 remains unaffected by this storage effect. Furthermore, we show that serum 24,25(OH)2D3 provides a stronger reflection of FF levels than serum 25(OH)D3, which is an important methodological consideration for studies using serum as a surrogate for ovarian vitamin D status.

Several mechanisms could underlie the differential behaviour observed between these metabolites. The decline in 25(OH)D3 may reflect its greater chemical instability during freezing and thawing, while the stability of 24,25(OH)2D3 could relate to its different molecular structure or binding properties. The stronger serum–FF correlation observed for 24,25(OH)2D3 may also be due to its position in the metabolic pathway, functioning as a product of regulated catabolism rather than as a substrate whose concentration is influenced by diet, supplementation, and storage artefacts.

The clinical and wider implications of these findings merit discussion. For investigators relying on retrospective analyses of biobanked samples, the use of 24,25(OH)2D3, preferably measured by LC–MS/MS, may substantially improve the reliability and accuracy of results. Our results also caution against overinterpretation of 25(OH)D3 data from stored specimens, which may underestimate true values. From a clinical perspective, however, 25(OH)D3 will remain the pragmatic biomarker of choice because it is widely available, inexpensive, and recommended in guidelines [41]. The adoption of 24,25(OH)2D3 into routine clinical care is limited by the cost and technical requirements of LC–MS/MS, and the use of this metabolite would necessitate the development of new classification thresholds, since its levels in both serum and FF differ from those of 25(OH)D3. Our findings should therefore be interpreted primarily in the research context—as a methodological refinement to enhance our understanding of vitamin D physiology—rather than as a call to change clinical practice. In this context, our study offers a controlled experimental setting to examine vitamin D metabolism and to identify metabolites that may provide more stable and physiologically relevant information about ovarian vitamin D status. These results provide evidence supporting 24,25(OH)2D3 as a good candidate for studying the ovarian vitamin D profile, as we propose a more reliable metabolite between serum and follicular fluid as well as after months of storage, which is common in molecular research. However, for broader implications in clinical practice, it should be further tested in patient populations and associated with reproductive outcomes.

Although exploratory in nature, our study has some strengths worth noting. We assessed two metabolites in both serum and follicular fluid, used LC–MS/MS as a reference method, and explicitly tested the effect of long-term storage, which is often overlooked. The homogeneous cohort of young, healthy donors reduced confounding by age, BMI, and comorbidities, while collection only during the autumn season minimised seasonal variation in sun exposure that could otherwise influence vitamin D levels [62]. Together, this provided a clean model to explore methodological questions.

Limitations include the restriction to oocyte donors, which limits generalisability to infertile populations, older women, or those with comorbid conditions. Moreover, our design did not include a direct assessment of reproductive outcomes, which prevents drawing conclusions about clinical efficacy. Future research should explore whether 24,25(OH)2D3, alone or in combination with 25(OH)D3, predicts outcomes of clinical importance, such as oocyte competence, embryo quality, implantation, and live birth. Validation in larger and more diverse populations is needed, including infertile women; those with polycystic ovary syndrome, diminished ovarian reserve, and obesity; and across different ancestries. Prospective trials should incorporate standardised protocols for sample handling, storage, and analysis and should explore whether incorporating 24,25(OH)2D3 into multiparametric biomarker panels alongside other ovarian markers improves predictive models in ART.

In summary, this study contributes to clarifying a methodological source of variability in vitamin D research, which is essential for understanding the role of vitamin D in female fertility. By showing that serum 24,25(OH)2D3 remains stable during long-term storage and correlates more closely with follicular fluid than 25(OH)D3, we provide evidence that this metabolite may offer added value as a research biomarker, particularly for retrospective studies based on archived samples. Although its measurement by high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) remains challenging in clinical settings, the stability and stronger ovarian relevance of 24,25(OH)2D3 suggest that its incorporation into reproductive research may help overcome storage-related limitations and improve the reliability of studies based on archived samples.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17233783/s1, Supplementary File S1 (Datos.xlsx): Metabolite concentrations. Concentrations of vitamin D metabolites—25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25(OH)2D3)—quantified by ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) at baseline and after seven months of storage at −80 °C for serum and follicular fluid.

Author Contributions

E.E.L.-M. conceived and designed the study, collected samples, performed experiments, analysed data, drafted the manuscript, and coordinated project administration and funding acquisition. J.M.F. contributed to the study design and critically revised the manuscript. A.D.-P. contributed to methodology, performed analyses, and interpreted data. M.L.-N. contributed to methodology and sample processing. A.V. and D.A. contributed to the collection of samples. A.B. and A.P. contributed to the original idea, provided resources, and contributed to reviewing the manuscript; P.S.-L. performed the statistical analyses and contributed to data interpretation and manuscript writing. P.D.-G. contributed to the study design, curated data, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, supervised the project, and contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by IVIRMA Barcelona and IVI Foundation (project 1701-BCN-007-EL) by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant PI21/00310 to A.P.), and co-founded by the European Union and by the BIRTH Grant 2021 from Theramex UK to E.E.L.-M. Union. P.D.-G., which was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII; Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation) through the Miguel Servet program (CP20/00118), co-founded by the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona (protocol HCB/2017/0224, 6 April 2017). This study adhered to the fundamental principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, the Council of Europe Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, and the UNESCO Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights. It also complies with the good practice requirements established in Spanish legislation in the fields of biomedical research, personal data protection, and bioethics.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The clinical datasets generated and analysed during the current study have not been deposited in a public repository due to patient privacy and ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (P.D-G and P. S-L.). Metabolite concentrations are included in Supplementary File S1.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the volunteers who participated in the study and the staff of IVIRMA Barcelona and the IVI Foundation for their support throughout the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weisman, Y.; Harell, A.; Edelstein, S.; David, M.; Spirer, Z.; Golander, A. 1 Alpha, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 24,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 in Vitro Synthesis by Human Decidua and Placenta. Nature 1979, 281, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, W.E.; Sar, M.; Reid, F.A.; Tanaka, Y.; DeLuca, H.F. Target Cells for 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 in Intestinal Tract, Stomach, Kidney, Skin, Pituitary, and Parathyroid. Science 1979, 206, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoh, S.; Donaldson, C.A.; Marion, S.L.; Pike, J.W.; Haussler, M.R. The Ovary: A Target Organ for 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. Endocrinology 1983, 112, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Grande, J.P.; Roche, P.C.; Kumar, R. Immunohistochemical Detection and Distribution of the 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Receptor in Rat Reproductive Tissues. Histochem. Cell Biol. 1996, 105, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, R.E.; Toader, O.D.; Gheoca Mutu, D.E.; Stănculescu, R.V. The Key Role of Vitamin D in Female Reproductive Health: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e65560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łagowska, K. The Relationship between Vitamin D Status and the Menstrual Cycle in Young Women: A Preliminary Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, G.; Varadinova, M.; Suwandhi, P.; Araki, T.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Poretsky, L.; Seto-Young, D. Vitamin D Regulates Steroidogenesis and Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-1 (IGFBP-1) Production in Human Ovarian Cells. Horm. Metab. Res. 2010, 42, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Tamar, N.; Lone, Z.; Das, E.; Sahu, R.; Majumdar, S. Association between Serum 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D Level and Menstrual Cycle Length and Regularity: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2021, 19, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, Z.; Doswell, A.; Krebs, K.; Cipolla, M. Vitamin D Alters Genes Involved in Follicular Development and Steroidogenesis in Human Cumulus Granulosa Cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E1137–E1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.K.Y.; Shi, J.; Li, R.H.W.; Yeung, W.S.B.; Ng, E.H.Y. 100 YEARS OF VITAMIN D: Effect of Serum Vitamin D Level before Ovarian Stimulation on the Cumulative Live Birth Rate of Women Undergoing in Vitro Fertilization: A Retrospective Analysis. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, M.; Von Versen-Höynck, F. Vitamin D—Roles in Women’s Reproductive Health? Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahsin, T.; Khanam, R.; Chowdhury, N.H.; Hasan, A.S.M.T.; Hosen, M.D.B.; Rahman, S.; Roy, A.K.; Ahmed, S.; Raqib, R.; Baqui, A.H. Vitamin D Deficiency in Pregnancy and the Risk of Preterm Birth: A Nested Case–Control Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tienhoven, X.A.; Ruiz De Chávez Gascón, J.; Cano-Herrera, G.; Sarkis Nehme, J.A.; Souroujon Torun, A.A.; Bautista Gonzalez, M.F.; Esparza Salazar, F.; Sierra Brozon, A.; Rivera Rosas, E.G.; Carbajal Ocampo, D.; et al. Vitamin D in Reproductive Health Disorders: A Narrative Review Focusing on Infertility, Endometriosis, and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnanz, A.; De Munck, N.; El Khatib, I.; Bayram, A.; Abdala, A.; Melado, L.; Lawrenz, B.; Coughlan, C.; Pacheco, A.; Garcia-Velasco, J.A.; et al. Vitamin D in Follicular Fluid Correlates With the Euploid Status of Blastocysts in a Vitamin D Deficient Population. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11, 609524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, H.; Ku, S.-Y. The Level of Vitamin D in Follicular Fluid and Ovarian Reserve in an in Vitro Fertilization Program: A Pilot Study. Sci. Progress. 2022, 105, 00368504221103782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurt, R.; Karakus, C. Follicular Fluid 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels Determine Fertility Outcome in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 61, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremic, A.; Mikovic, Z.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Isenovic, E.; Perovic, M. Follicular and Serum Levels of Vitamin D in Women with Unexplained Infertility and Their Relationship with in Vitro Fertilization Outcome: An Observational Pilot Study. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putri Susilo, A.F.; Syam, H.H.; Bayuaji, H.; Rachmawati, A.; Halim, B.; Permadi, W.; Djuwantono, T. Free 25(OH)D3 Levels in Follicular Ovarian Fluid Top-Quality Embryos Are Higher than Non-Top-Quality Embryos in the Normoresponders Group. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapuy, M.-C.; Preziosi, P.; Maamer, M.; Arnaud, S.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Meunier, P.J. Prevalence of Vitamin D Insufficiency in an Adult Normal Population. Osteoporos. Int. 1997, 7, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacis, M.M.; Fortin, C.N.; Zarek, S.M.; Mumford, S.L.; Segars, J.H. Vitamin D and Assisted Reproduction: Should Vitamin D Be Routinely Screened and Repleted Prior to ART? A Systematic Review. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Gallos, I.; Tobias, A.; Tan, B.; Eapen, A.; Coomarasamy, A. Vitamin D and Assisted Reproductive Treatment Outcome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Human. Reprod. 2018, 33, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.D.; Dowling, K.G.; Škrabáková, Z.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Valtueña, J.; De Henauw, S.; Moreno, L.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Mølgaard, C.; et al. Vitamin D Deficiency in Europe: Pandemic? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoffferrari, H.; Dawsonhughes, B. Where Do We Stand on Vitamin D? Bone 2007, 41, S13–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Elamin, K.B.; Abu Elnour, N.O.; Elamin, M.B.; Alkatib, A.A.; Fatourechi, M.M.; Almandoz, J.P.; Mullan, R.J.; Lane, M.A.; Liu, H.; et al. The Effect of Vitamin D on Falls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 2997–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustina, A.; Bilezikian, J.P.; Adler, R.A.; Banfi, G.; Bikle, D.D.; Binkley, N.C.; Bollerslev, J.; Bouillon, R.; Brandi, M.L.; Casanueva, F.F.; et al. Consensus Statement on Vitamin D Status Assessment and Supplementation: Whys, Whens, and Hows. Endocr. Rev. 2024, 45, 625–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.D. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: A Difficult Analyte. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Interpreting Vitamin D Assay Results: Proceed with Caution. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Cheng, X.; Fang, H.; Zhang, R.; Han, J.; Qin, X.; Cheng, Q.; Su, W.; Hou, L.; Xia, L.; et al. 25OHD Analogues and Vacuum Blood Collection Tubes Dramatically Affect the Accuracy of Automated Immunoassays. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, D.; Lombardi, G.; Banfi, G. Concerning the Vitamin D Reference Range: Pre-Analytical and Analytical Variability of Vitamin D Measurement. Biochem. Medica 2017, 27, 030501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, J.A.; Barrett, J.; Malenka, D.; Fisher, E.; Kniffin, W.; Bubolz, T.; Tosteson, T. Racial differences in fracture risk. Epidemiology 1994, 5, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.S.; Soteriades, E.; Coolidge, J.A.S.; Mudgal, S.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Vitamin D Insufficiency and Hyperparathyroidism in a Low Income, Multiracial, Elderly Population1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 4125–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Tylavsky, F.; Kröger, H.; Kärkkäinen, M.; Lyytikäinen, A.; Koistinen, A.; Mahonen, A.; Alen, M.; Halleen, J.; Väänänen, K.; et al. Association of Low 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations with Elevated Parathyroid Hormone Concentrations and Low Cortical Bone Density in Early Pubertal and Prepubertal Finnish Girls. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Schuit, F.; Antonio, L.; Rastinejad, F. Vitamin D Binding Protein: A Historic Overview. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissner, D.; Mason, R.S.; Posen, S. Stability of Vitamin D Metabolites in Human Blood Serum and Plasma. Clin. Chem. 1981, 27, 773–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.K.Y.; Chen, S.P.L.; Lam, K.K.W.; Chan, T.O.; Li, R.H.W.; Ng, E.H.Y. Effect of Freezing and Storage on Serum Vitamin D Levels Measured by Mass Spectrometry and Immunoassay in Reproductive Age Women. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronov, P.A.; Hall, L.M.; Dettmer, K.; Stephensen, C.B.; Hammock, B.D. Metabolic Profiling of Major Vitamin D Metabolites Using Diels–Alder Derivatization and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 391, 1917–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineva, E.M.; Schleicher, R.L.; Chaudhary-Webb, M.; Maw, K.L.; Botelho, J.C.; Vesper, H.W.; Pfeiffer, C.M. A Candidate Reference Measurement Procedure for Quantifying Serum Concentrations of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 and 25-Hydroxyvitamin D2 Using Isotope-Dilution Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 5615–5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, S.A.; Phinney, K.W.; Tai, S.S.-C.; Camara, J.E.; Myers, G.L.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Tian, L.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Bachmann, L.M.; Young, I.S.; et al. Baseline Assessment of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Assay Performance: A Vitamin D Standardization Program (VDSP) Interlaboratory Comparison Study. J. AOAC Int. 2017, 100, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.; Farrell, C.-J.L.; Pusceddu, I.; Fabregat-Cabello, N.; Cavalier, E. Assessment of Vitamin D Status—A Changing Landscape. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017, 55, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; Ross, A.C., Taylor, C.L., Yaktine, A.L., Del Valle, H.B., Eds.; The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demay, M.B.; Pittas, A.G.; Bikle, D.D.; Diab, D.L.; Kiely, M.E.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Lips, P.; Mitchell, D.M.; Murad, M.H.; Powers, S.; et al. Vitamin D for the Prevention of Disease: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1907–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, M.; Gallagher, J.C.; Peacock, M.; Schlingmann, K.-P.; Konrad, M.; DeLuca, H.F.; Sigueiro, R.; Lopez, B.; Mourino, A.; Maestro, M.; et al. Clinical Utility of Simultaneous Quantitation of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and 24,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D by LC-MS/MS Involving Derivatization with DMEQ-TAD. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 2567–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.C.Y.; Nicholls, H.; Piec, I.; Washbourne, C.J.; Dutton, J.J.; Jackson, S.; Greeves, J.; Fraser, W.D. Reference Intervals for Serum 24,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D and the Ratio with 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Established Using a Newly Developed LC–MS/MS Method. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 46, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.; Zeileis, A.; Hornik, K. The Strucplot Framework: Visualizing Multi-Way Contingency Tables with Vcd. J. Stat. Soft. 2006, 17, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.; Jindal, S.; Greenseid, K.; Shu, J.; Zeitlian, G.; Hickmon, C.; Pal, L. Replete Vitamin D Stores Predict Reproductive Success Following in Vitro Fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudick, B.; Ingles, S.; Chung, K.; Stanczyk, F.; Paulson, R.; Bendikson, K. Characterizing the Influence of Vitamin D Levels on IVF Outcomes. Human. Reprod. 2012, 27, 3321–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.S.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y. Serum Vitamin D Status and in Vitro Fertilization Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, L.; Zhang, H.; Williams, J.; Santoro, N.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Schlaff, W.D.; Coutifaris, C.; Carson, S.A.; Steinkampf, M.P.; Carr, B.R.; et al. Vitamin D Status Relates to Reproductive Outcome in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Secondary Analysis of a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3027–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleyasin, A.; Hosseini, M.A.; Mahdavi, A.; Safdarian, L.; Fallahi, P.; Mohajeri, M.R.; Abbasi, M.; Esfahani, F. Predictive Value of the Level of Vitamin D in Follicular Fluid on the Outcome of Assisted Reproductive Technology. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011, 159, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franasiak, J.M.; Molinaro, T.A.; Dubell, E.K.; Scott, K.L.; Ruiz, A.R.; Forman, E.J.; Werner, M.D.; Hong, K.H.; Scott, R.T. Vitamin D Levels Do Not Affect IVF Outcomes Following the Transfer of Euploid Blastocysts. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 315.e1–315.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firouzabadi, R.D.; Rahmani, E.; Rahsepar, M.; Firouzabadi, M.M. Value of Follicular Fluid Vitamin D in Predicting the Pregnancy Rate in an IVF Program. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Vijver, A.; Drakopoulos, P.; Van Landuyt, L.; Vaiarelli, A.; Blockeel, C.; Santos-Ribeiro, S.; Tournaye, H.; Polyzos, N.P. Vitamin D Deficiency and Pregnancy Rates Following Frozen–Thawed Embryo Transfer: A Prospective Cohort Study. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1749–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabris, A.M.; Cruz, M.; Iglesias, C.; Pacheco, A.; Patel, A.; Patel, J.; Fatemi, H.; García-Velasco, J.A. Impact of Vitamin D Levels on Ovarian Reserve and Ovarian Response to Ovarian Stimulation in Oocyte Donors. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2017, 35, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C.-J.L.; Martin, S.; McWhinney, B.; Straub, I.; Williams, P.; Herrmann, M. State-of-the-Art Vitamin D Assays: A Comparison of Automated Immunoassays with Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Methods. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempos, C.T.; Vesper, H.W.; Phinney, K.W.; Thienpont, L.M.; Coates, P.M.; Vitamin D Standardization Program (VDSP). Vitamin D Status as an International Issue: National Surveys and the Problem of Standardization. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2012, 243, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, N.; Sempos, C.T.; Vitamin D Standardization Program (VDSP). Standardizing Vitamin D Assays: The Way Forward. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.D.; Berry, J.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Gunter, E.; Jones, G.; Jones, J.; Makin, H.L.J.; Pattni, P.; Sempos, C.T.; Twomey, P.; et al. Hydroxyvitamin D Assays: An Historical Perspective from DEQAS. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franasiak, J.M.; Lara, E.E.; Pellicer, A. Vitamin D in Human Reproduction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, S.; Barbieri, V.; Di Pierro, A.M.; Rossi, F.; Widmann, T.; Lucchiari, M.; Pusceddu, I.; Pilz, S.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Herrmann, M. LC–MS/MS Based 25(OH)D Status in a Large Southern European Outpatient Cohort: Gender- and Age-Specific Differences. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 2511–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).