Clinical Impact of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index on Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Multicenter Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Clinical Information

2.2. Calculation of GNRI

2.3. Definition and Calculation of RDI

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics at Diagnosis and Details of SAEs

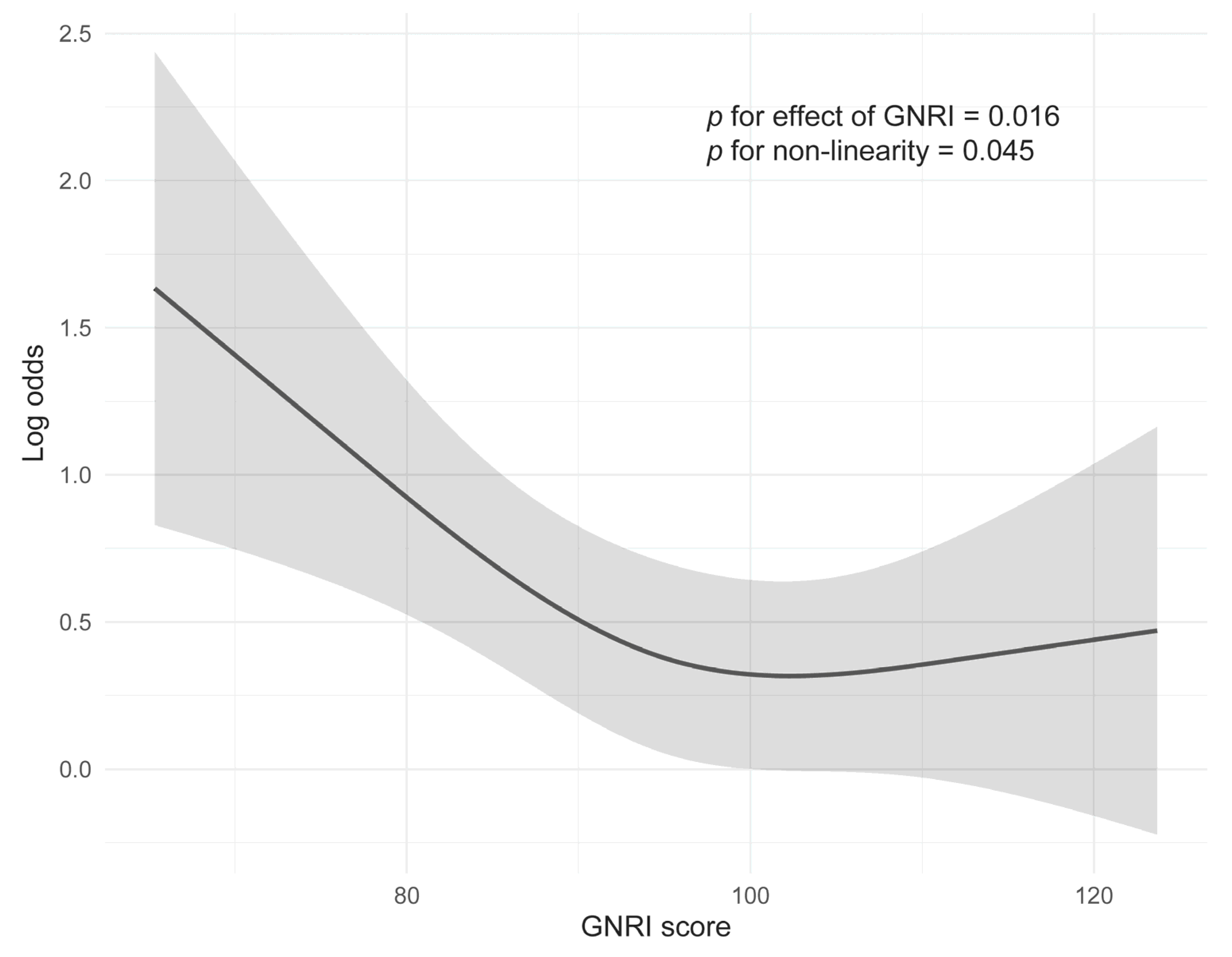

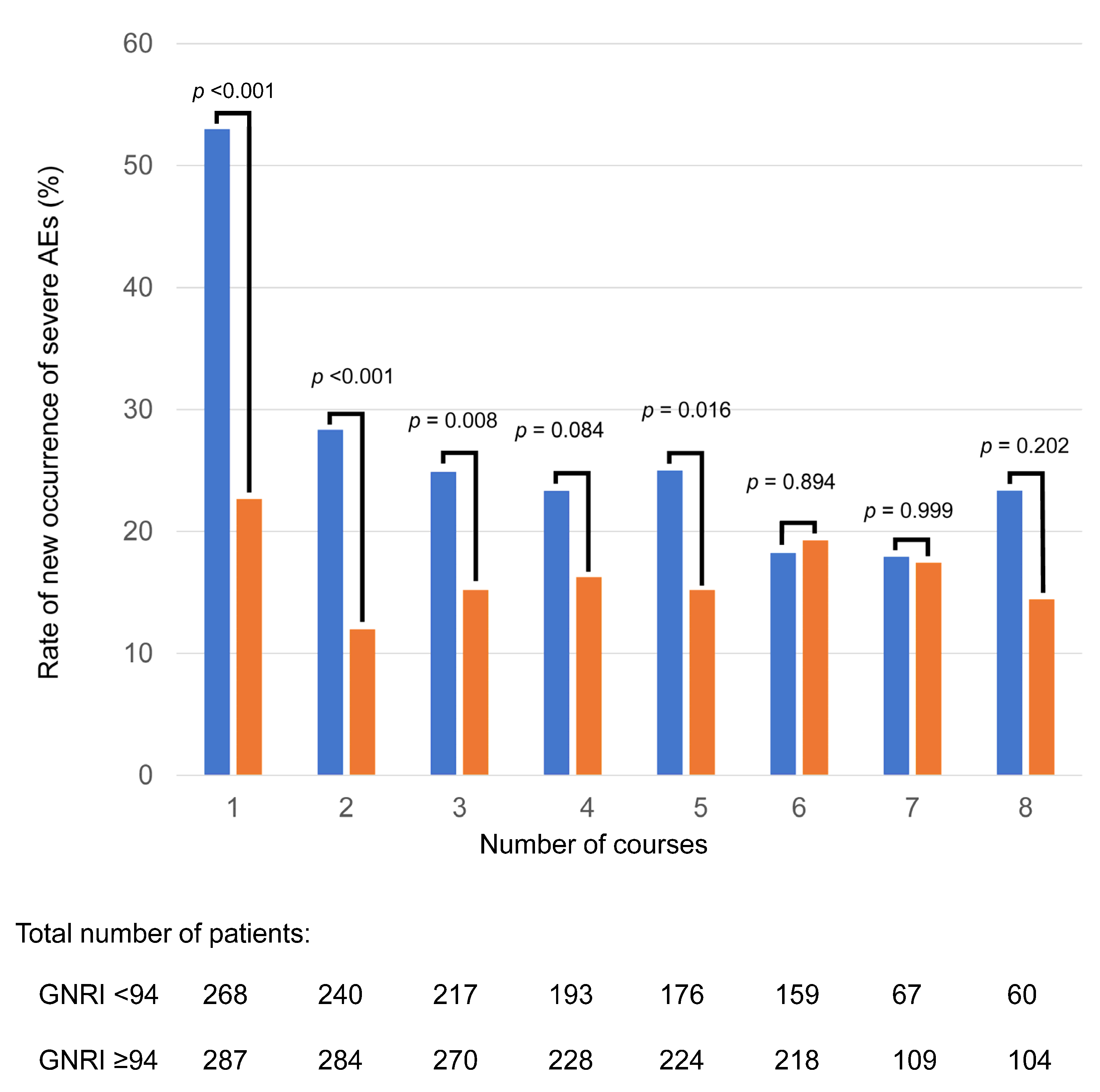

3.2. Relationship Between GNRI and Frequency of SAEs

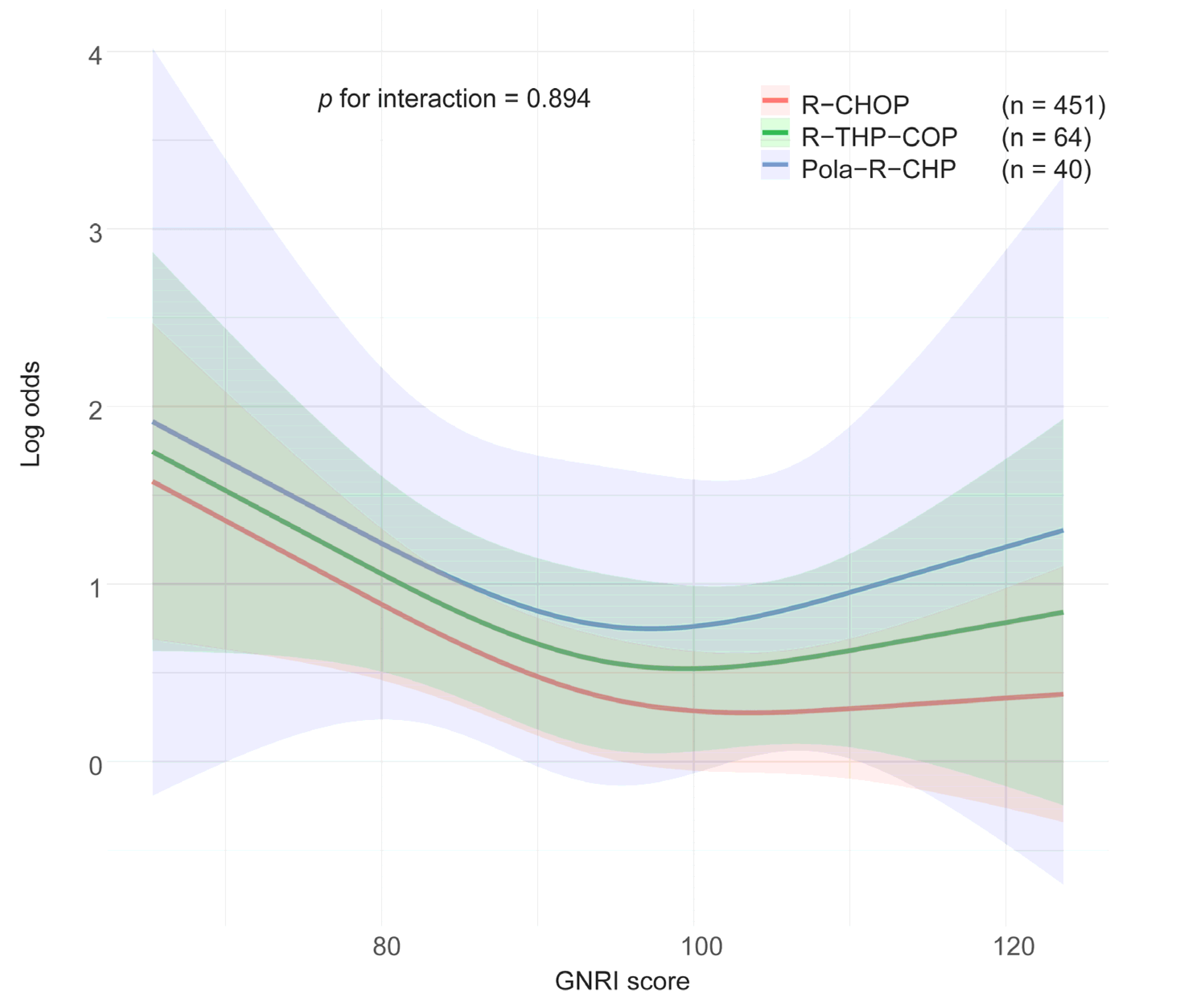

3.3. Impact of Treatment Regimen and Age on Associations Between GNRI and SAEs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Adverse event |

| ADR | Adriamycin |

| Alb | Serum albumin |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| ARDI | Average relative dose intensity |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CPA | Cyclophosphamide |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| DCA | Decision curve analysis |

| DI | Dose intensity |

| DLBCL | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| FN | Febrile neutropenia |

| G-CSF | Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| GNRI | Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index |

| IDI | Integrated Discrimination Improvement |

| IPI | International Prognostic Index |

| LR | Likelihood ratio |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| NRI | Net Reclassification Improvement |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PEG-G-CSF | Pegylated granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| Pola | Polatuzumab vedotin |

| Pola-R-CHP | Polatuzumab vedotin, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, and prednisolone |

| PNI | Prognostic Nutritional Index |

| PS | Performance status |

| PSL | Prednisolone |

| R | R programming language |

| R-CHOP | Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisolone |

| R-THP-COP | Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, tetrahydropyranyl adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisolone |

| RCS | Restricted cubic spline |

| RDI | Relative dose intensity |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| RTX | Rituximab |

| SAE | Severe adverse event |

| tARDI | Total average relative dose intensity |

| THP | Tetrahydropyranyl adriamycin |

| VCR | Vincristine |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Pileri, S.A.; Harris, N.L.; Stein, H.; Siebert, R.; Advani, R.; Ghielmini, M.; Salles, G.A.; Zelenetz, A.D.; et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016, 127, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.O.; Jeon, Y.K.; Paik, J.H.; Kim, W.Y.; Kim, Y.A.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, C.W. MYC translocation and an increased copy number predict poor prognosis in adult diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), especially in germinal centre-like B cell (GCB) type. Histopathology 2008, 53, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibiletti, M.G.; Martin, V.; Bernasconi, B.; Del Curto, B.; Pecciarini, L.; Uccella, S.; Pruneri, G.; Ponzoni, M.; Mazzucchelli, L.; Martinelli, G.; et al. BCL2, BCL6, MYC, MALT 1, and BCL10 rearrangements in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: A multicenter evaluation of a new set of fluorescent in situ hybridization probes and correlation with clinical outcome. Hum. Pathol. 2009, 40, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, L.W.; Halpern, J.; Olshen, R.A.; Horning, S.J. Prognostic significance of actual dose intensity in diffuse large-cell lymphoma: Results of a tree-structured survival analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990, 8, 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosly, A.; Bron, D.; Van Hoof, A.; De Bock, R.; Berneman, Z.; Ferrant, A.; Kaufman, L.; Dauwe, M.; Verhoef, G. Achievement of optimal average relative dose intensity and correlation with survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with CHOP. Ann. Hematol. 2008, 87, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Fujita, K.; Negoro, E.; Morishita, T.; Oiwa, K.; Tsukasaki, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Kawai, Y.; Ueda, T.; Yamauchi, T. Impact of relative dose intensity of standard regimens on survival in elderly patients aged 80 years and older with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2020, 105, e415–e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataillard, E.J.; Cheah, C.Y.; Maurer, M.J.; Khurana, A.; Eyre, T.A.; El-Galaly, T.C. Impact of R-CHOP dose intensity on survival outcomes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A systematic review. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 2426–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyman, G.H.; Dale, D.C.; Friedberg, J.; Crawford, J.; Fisher, R.I. Incidence and predictors of low chemotherapy dose-intensity in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A nationwide study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4302–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.P.; Marx, M.Z.; Henchen, C.; DeGroote, N.P.; Jones, S.; Weiland, J.; Fisher, B.D.; Esbenshade, A.J.M.; Aplenc, R.; Dvorak, C.C.; et al. Challenges and Barriers to Adverse Event Reporting in Clinical Trials: A Children’s Oncology Group Report. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e672–e679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauder, R.; Augschoell, J.; Hamaker, M.E.; Koinig, K.A. Malnutrition in Older Patients with Hematological Malignancies at Initial Diagnosis—Association with Impairments in Health Status, Systemic Inflammation and Adverse Outcome. Hemasphere 2020, 4, e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, F.; Pietras, E.M.; Manz, M.G. Inflammation as a regulator of hematopoietic stem cell function in disease, aging, and clonal selection. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20201541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillanne, O.; Morineau, G.; Dupont, C.; Coulombel, I.; Vincent, J.P.; Nicolis, I.; Benazeth, S.; Cynober, L.; Aussel, C. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index: A new index for evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemasa, Y.; Shimoyama, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Hishima, T.; Omuro, Y. Geriatric nutritional risk index as a prognostic factor in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2018, 97, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Fujita, K.; Morishita, T.; Negoro, E.; Oiwa, K.; Tsukasaki, H.; Yamamura, O.; Ueda, T.; Yamauchi, T. Prognostic utility of a geriatric nutritional risk index in combination with a comorbidity index in elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 192, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, K.; Sawada, M.; Takeda, G.; Watanabe, T.; Souma, T.; Sato, H. Influence of Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index on Occurrence of Adverse Events and Duration of Treatment in Patients with Lymphoma Receiving R-CHOP Therapy. In Vivo 2023, 37, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, K.; Tsukasaki, H.; Lee, S.; Morishita, T.; Negoro, E.; Oiwa, K.; Hara, T.; Tsurumi, H.; Ueda, T.; Yamauchi, T. Age interaction in associations between geriatric nutritional risk index and prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Harris, N.L.; Jaffe, E.S.; Pileri, S.A.; Stein, H.; Thiele, J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th ed.; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coiffier, B.; Lepage, E.; Briere, J.; Herbrecht, R.; Tilly, H.; Bouabdallah, R.; Morel, P.; Van Den Neste, E.; Salles, G.; Gaulard, P.; et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Goto, H.; Sawada, M.; Yamada, T.; Fukuno, K.; Kasahara, S.; Shibata, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Mabuchi, R.; et al. R-THP-COP versus R-CHOP in patients younger than 70 years with untreated diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A randomized, open-label, noninferiority phase 3 trial. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 36, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, H.; Morschhauser, F.; Sehn, L.H.; Friedberg, J.W.; Trněný, M.; Sharman, J.P.; Herbaux, C.; Burke, J.M.; Matasar, M.; Rai, S.; et al. Polatuzumab Vedotin in Previously Untreated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygin, C.; Jia, X.; Hill, B.; Dean, R.; Pohlman, B.; Smith, M.R.; Jagadeesh, D. Impact of comorbidities on outcomes of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Pencina, M.J.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; D’Agostino, R.B., Jr.; Vasan, R.S. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 157–172; discussion 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A.J.; Elkin, E.B. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Mak. 2006, 26, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Dhiman, P.; Andaur Navarro, C.L.; Ma, J.; Hooft, L.; Reitsma, J.B.; Logullo, P.; Beam, A.L.; Peng, L.; Van Calster, B.; et al. Protocol for development of a reporting guideline (TRIPOD-AI) and risk of bias tool (PROBAST-AI) for diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies based on artificial intelligence. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team; R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Li, Q. The controlling nutritional status score as a predictor of survival in hematological malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1402328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukawa, T.; Suto, K.; Kanaya, M.; Izumiyama, K.; Minauchi, K.; Yoshida, S.; Oda, H.; Miyagishima, T.; Mori, A.; Ota, S.; et al. Validation and comparison of prognostic values of GNRI, PNI, and CONUT in newly diagnosed diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 2859–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Lin, C.C.; Mariotto, A.B.; Kramer, J.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Stein, K.D.; Alteri, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.P.; Li, Y.; Getz, K.D.; Dudley, J.; Burrows, E.; Pennington, J.; Ibrahimova, A.; Fisher, B.T.; Bagatell, R.; Seif, A.E.; et al. Using electronic medical record data to report laboratory adverse events. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 177, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettengell, R.; Johnsen, H.E.; Lugtenburg, P.J.; Silvestre, A.S.; Dührsen, U.; Rossi, F.G.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Bendall, K.; Szabo, Z.; Jaeger, U. Impact of febrile neutropenia on R-CHOP chemotherapy delivery and hospitalizations among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Statistics. Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan (National Cancer Registry, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). Available online: https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/data/dl/index.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Don, B.R.; Kaysen, G. Serum albumin: Relationship to inflammation and nutrition. Semin. Dial. 2004, 17, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeters, P.B.; Wolfe, R.R.; Shenkin, A. Hypoalbuminemia: Pathogenesis and Clinical Significance. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2019, 43, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Gackowski, M.; Hołyńska-Iwan, I.; Parzych, D.; Czuczejko, J.; Graczyk, M.; Husejko, J.; Jabłoński, T.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Selected Biochemical, Hematological, and Immunological Blood Parameters for the Identification of Malnutrition in Polish Senile Inpatients: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mądra-Gackowska, K.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Gackowski, M.; Woźniak, A.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Evaluation of Selected Parameters of Oxidative Stress and Adipokine Levels in Hospitalized Older Patients with Diverse Nutritional Status. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Patients (N = 555) | With Severe AEs (n = 342) | Without Severe AEs (n = 213) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years-median, range | 74 | (27–96) | 75 | (35–96) | 72 | (27–96) | 0.008 |

| Male-n (%) | 284 | (51.2) | 170 | (49.7) | 114 | (53.5) | 0.384 |

| ECOG PS ≥ 2-n (%) | 169 | (30.5) | 134 | (39.2) | 35 | (16.4) | <0.001 |

| Extranodal sites ≥ 2-n (%) | 205 | (36.9) | 154 | (45.0) | 51 | (23.9) | <0.001 |

| Ann Arbor Stage III/IV-n (%) | 361 | (65.0) | 240 | (70.2) | 121 | (56.8) | 0.002 |

| Elevated LDH (>ULN)-n (%) | 350 | (63.1) | 230 | (67.3) | 120 | (56.3) | 0.011 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL)-median, range | 3.6 | (1.1–5.6) | 3.4 | (1.1–5.6) | 3.8 | (1.4–5.0) | <0.001 |

| IPI-n (%) | |||||||

| Score-median, range | 33 | (0–5) | 3 | (0–5) | 2 | (0–5) | <0.001 |

| Low (0, 1) | 121 | (21.8) | 57 | (16.7) | 64 | (30.1) | |

| Low intermediate (2) | 117 | (21.1) | 62 | (18.1) | 55 | (25.8) | <0.001 |

| High intermediate (3) | 112 | (20.2) | 67 | (19.6) | 45 | (21.1) | |

| High (4, 5) | 205 | (36.9) | 156 | (45.6) | 49 | (23.0) | |

| Bulky mass-n (%) | 132 | (23.8) | 91 | (26.6) | 41 | (19.3) | 0.058 |

| B symptoms-n (%) | 157 | (28.3) | 120 | (35.1) | 37 | (17.4) | <0.001 |

| CCI-n (%) | |||||||

| Score-median, range | 1 | (0–8) | 1 | (0–8) | 1 | (0–6) | 0.002 |

| 0 | 216 | (38.9) | 120 | (35.1) | 96 | (45.1) | |

| 1, 2 | 235 | (42.3) | 142 | (41.5) | 93 | (43.7) | <0.001 |

| 3, 4 | 78 | (14.1) | 57 | (16.7) | 21 | (9.9) | |

| ≥5 | 26 | (4.7) | 23 | (6.7) | 3 | (1.4) | |

| GNRI-n (%) | |||||||

| Score-median, range | 94.8 | (38.3–136.0) | 91.9 | (38.3–129.2) | 99.2 | (60.5–136.0) | <0.001 |

| No risk (>98) | 227 | (40.9) | 113 | (33.0) | 114 | (53.5) | |

| Mild (92–98) | 91 | (16.4) | 54 | (15.8) | 37 | (17.4) | <0.001 |

| Moderate (82 to <92) | 137 | (24.7) | 95 | (27.8) | 42 | (19.7) | |

| Severe (<82) | 100 | (18.0) | 80 | (23.4) | 20 | (9.4) | |

| Total ARDI, –median, range | 89.6 | (4.9–176.6) | 87.9 | (4.9–176.6) | 91.4 | (8.2–143.3) | 0.280 |

| Prophylactic oral antibiotics-n (%) | 69 | (12.4) | 48 | (14.0) | 21 | (9.9) | 0.194 |

| Prophylactic G-CSF-n (%) | 486 | (87.6) | 321 | (93.9) | 165 | (77.5) | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy-n (%) | |||||||

| R-CHOP | 451 | (81.3) | 272 | (79.5) | 179 | (84.0) | 0.403 |

| R-THP-COP | 64 | (11.5) | 44 | (12.9) | 20 | (9.4) | |

| Pola-R-CHP | 40 | (7.2) | 26 | (7.6) | 14 | (6.6) | |

| Adverse Event | All Duration (n = 555) n (%) | Course 1 (n = 555) n (%) | Course 2 (n = 524) n (%) | Course 3 (n = 487) n (%) | Course 4 (n = 421) n (%) | Course 5 (n = 400) n (%) | Course 6 (n = 377) n (%) | Course 7 (n = 176) n (%) | Course 8 (n = 164) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any non-hematological toxicity | 200 (36.0) | 94 (16.9) | 45 (8.6) | 44 (9.0) | 33 (7.8) | 27 (6.8) | 23 (6.1) | 15 (8.5) | 11 (6.7) |

| Anorexia | 33 (6.0) | 9 (1.6) | 5 (1.0) | 6 (1.2) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.2) |

| Lung infection | 32 (5.8) | 9 (1.6) | 10 (1.9) | 3 (0.6) | 4 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Sepsis | 30 (5.4) | 13 (2.3) | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 20 (3.6) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | 4 (1.0) | 6 (1.6) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Transaminase increased | 18 (3.2) | 8 (1.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | |||

| Hyperglycemia | 15 (2.7) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | |

| COVID-19 infection | 10 (1.8) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | ||||

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 10 (1.8) | 9 (1.6) | 1 (0.2) | ||||||

| Delirium | 9 (1.6) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Ileus | 9 (1.6) | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 277 (49.9) | 155 (27.9) | 70 (13.4) | 68 (14.0) | 65 (15.4) | 62 (15.5) | 57 (15.1) | 20 (11.4) | 23 (14.0) |

| Treatment-related mortality | 25 (4.5) | 7 (1.3) | 5 (1.0) | 8 (1.6) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujita, K.; Tsukasaki, H.; Lee, S.; Morishita, T.; Negoro, E.; Oiwa, K.; Hara, T.; Tsurumi, H.; Ueda, T.; Yamauchi, T. Clinical Impact of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index on Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Multicenter Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233785

Fujita K, Tsukasaki H, Lee S, Morishita T, Negoro E, Oiwa K, Hara T, Tsurumi H, Ueda T, Yamauchi T. Clinical Impact of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index on Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Multicenter Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233785

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujita, Kei, Hikaru Tsukasaki, Shin Lee, Tetsuji Morishita, Eiju Negoro, Kana Oiwa, Takeshi Hara, Hisashi Tsurumi, Takanori Ueda, and Takahiro Yamauchi. 2025. "Clinical Impact of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index on Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Multicenter Study" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233785

APA StyleFujita, K., Tsukasaki, H., Lee, S., Morishita, T., Negoro, E., Oiwa, K., Hara, T., Tsurumi, H., Ueda, T., & Yamauchi, T. (2025). Clinical Impact of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index on Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Multicenter Study. Nutrients, 17(23), 3785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233785