Adolescent Eating Disorder Risk in a Bilingual Region: Clinical Prevalence, Screening Challenges and Treatment Gap in South Tyrol, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To estimate the prevalence of ICD-10 diagnosed EDs among adolescents aged 11–17 years in South Tyrol.

- To estimate the prevalence of symptomatic EDs as assessed by SCOFF, to assess the differences between the German and Italian versions.

- To compare clinically diagnosed EDs and symptomatic SCOFF cases regarding age and gender.

- To associate psychosocial and lifestyle factors with symptomatic SCOFF scores.

- To identify discrepancies between answers of parents and children in body image perception.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Assessment of Clinically Diagnosed EDs

2.2. Screening of SCOFF Prevalence in the General Population

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Measures

2.2.2. Eating Disorders

2.2.3. Additional Psychosocial and Lifestyle Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

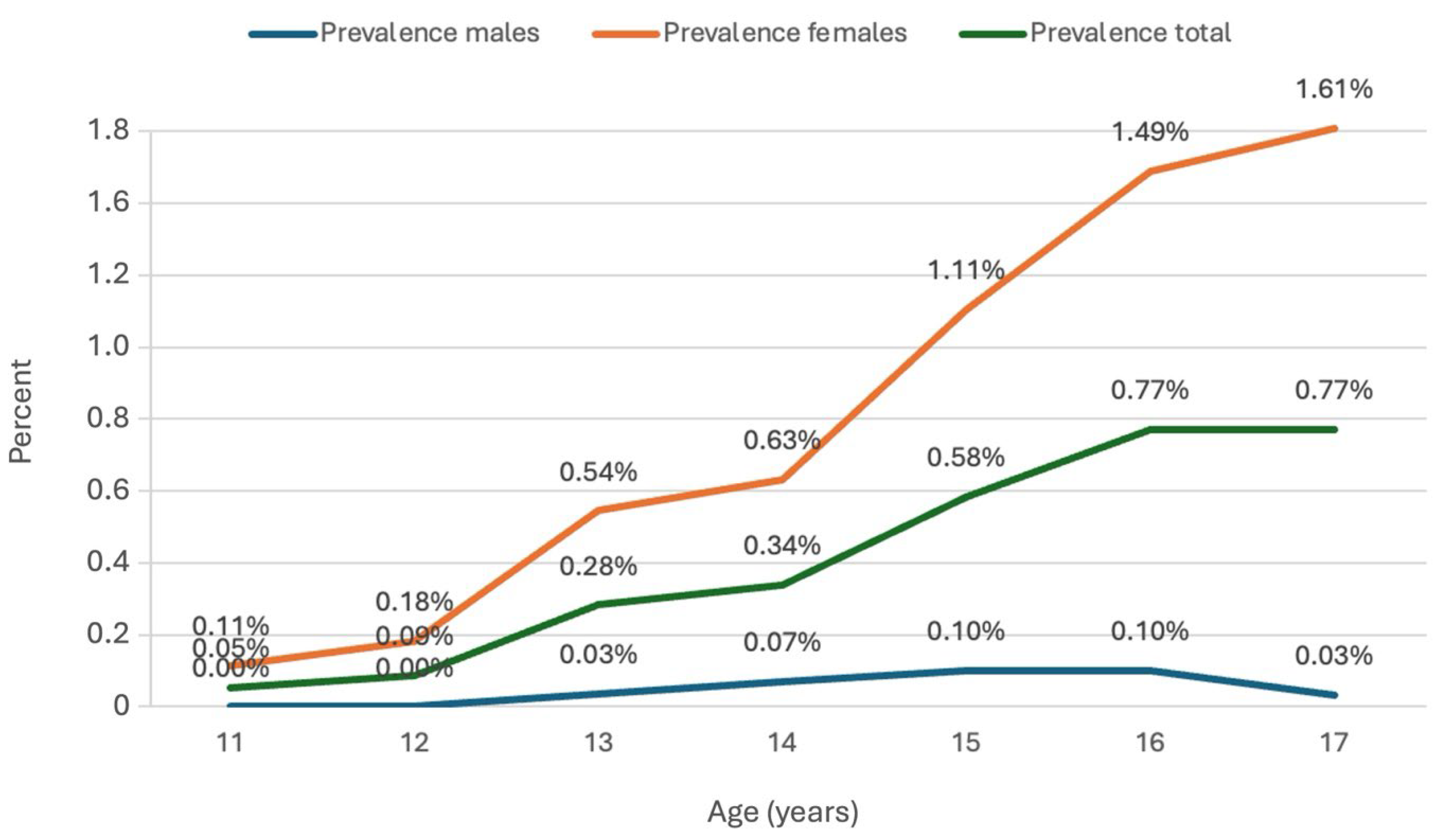

3.1. Clinically Diagnosed Eating Disorders in Adolescents

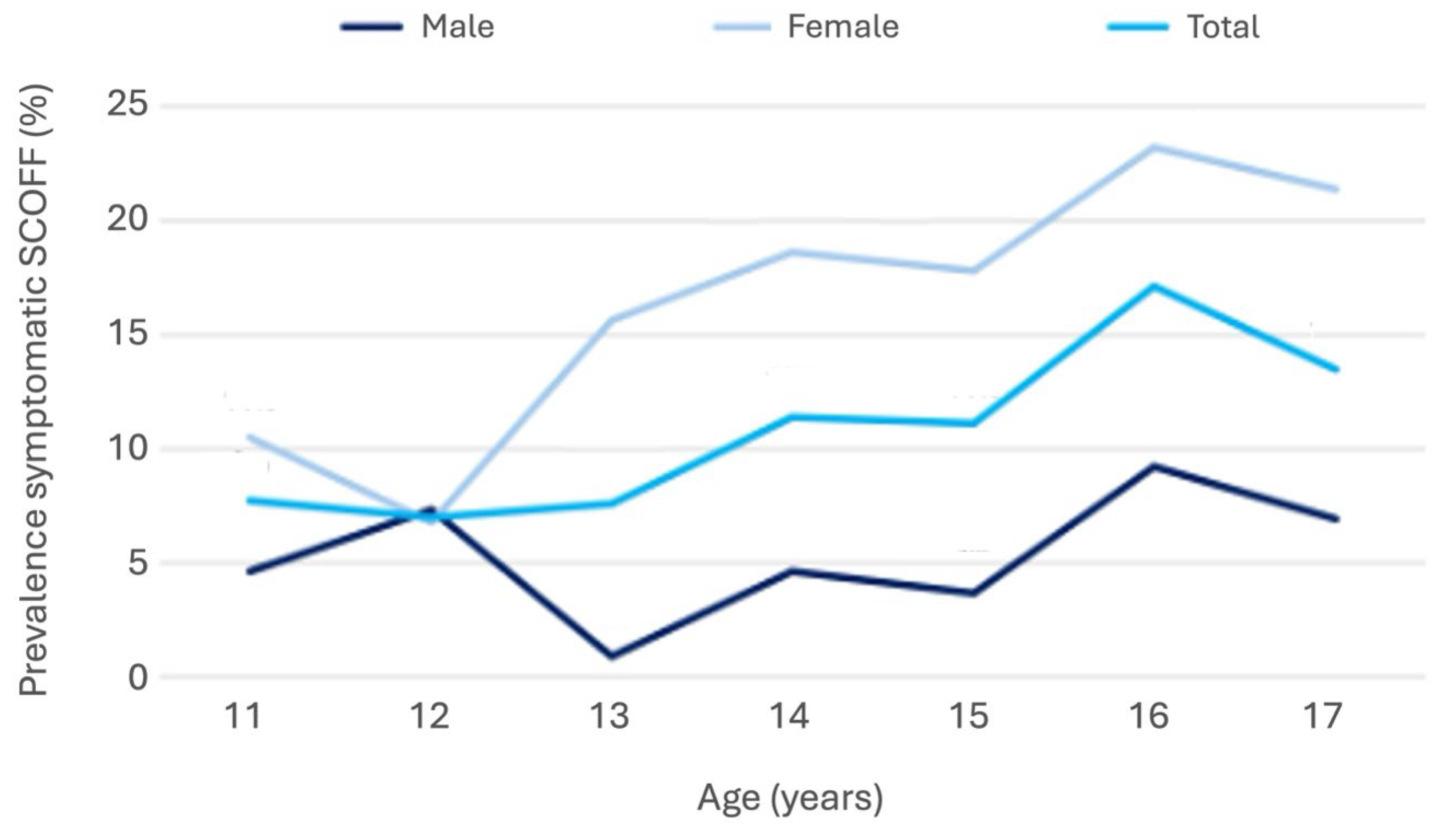

3.2. Screening Results

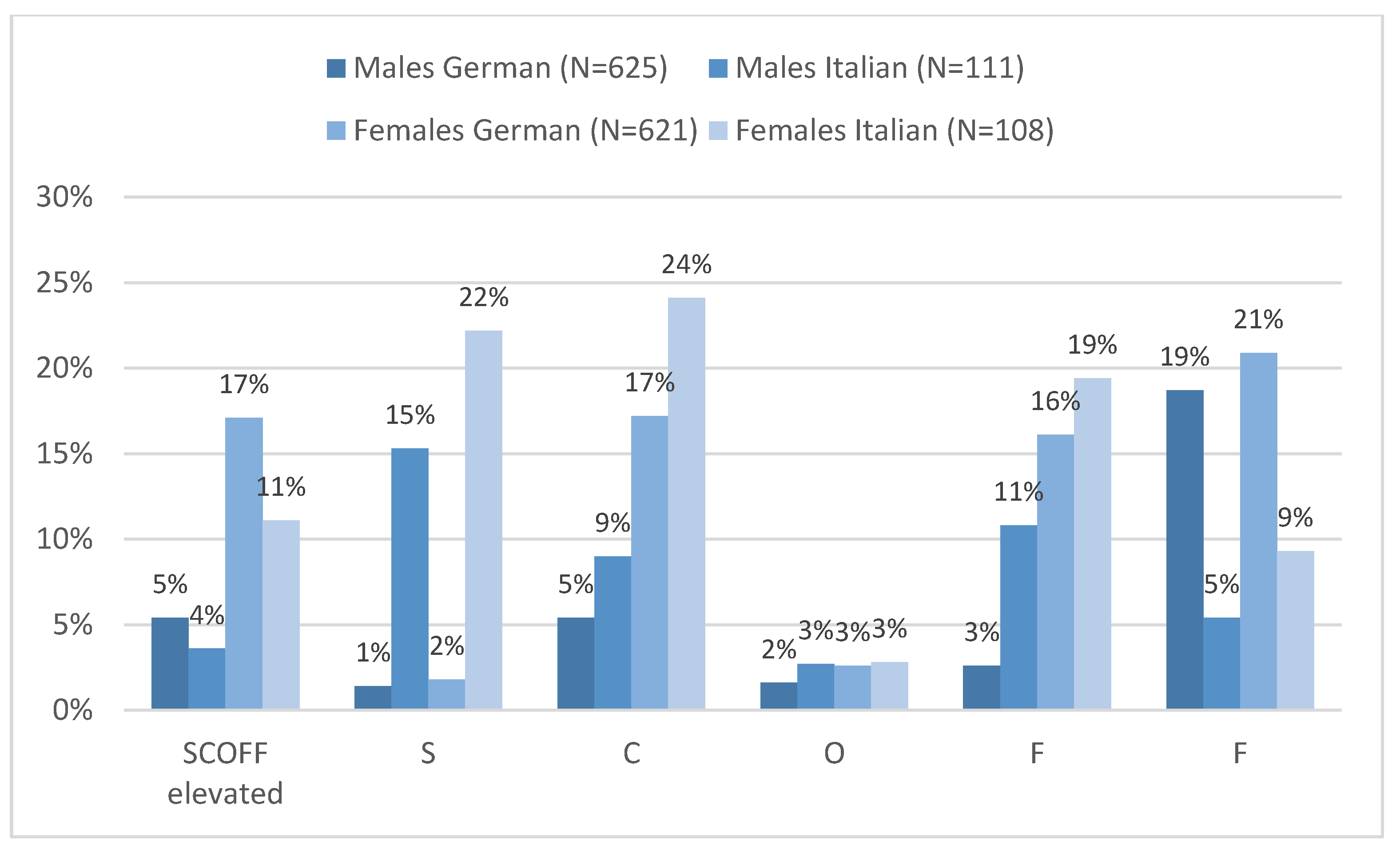

3.3. SCOFF in German- and Italian-Speaking Adolescents

3.4. Body Mass Index and Body Image

3.5. SCOFF Correlates and Predictors

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical vs. Screening Prevalence in a Bilingual Context

4.2. Psychosocial and Family-Related Determinants

4.3. Implications for Local Policies

4.4. Methodological Considerations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASTAT | Landesinstitut für Statistik der Autonomen Provinz Bozen-Südtirol |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CI | Confidence Intervals |

| COPSY | Corona and Psyche |

| ED | Eating Disorder |

| FAS | Family Affluence Scale |

| GPIUS | Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale |

| HLSAC | Health Literacy for School-Aged Children |

| HRQoL | Health Related Quality of Life |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases |

| KIGGS | German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents |

| M | mean |

| MSPSS | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support |

| n.s. | Not significant |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic curve, |

| SCOFF | Eating Disorder screening questionnaire (Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food) |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDQ | Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire |

Appendix A

| Item (Acronym) | English Wording | German Wording | Italian Wording |

|---|---|---|---|

| S (Sick) | Do you make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortably full? | Übergibst du dich, wenn du dich unangenehm voll fühlst? | Ti sei mai sentito/a eccessivamente disgustato/a perché eri sgradevolmente pieno/a? |

| C (Control) | Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat? | Machst du dir Sorgen, weil du manchmal nicht mit dem Essen aufhören kannst? | Ti sei mai preoccupato/a di aver perso il controllo su quanto avevi mangiato? |

| O (One stone) | Have you recently lost more than one stone (6.35 kg) in a three-month period? | Hast du in der letzten Zeit mehr als 6 kg in 3 Monaten abgenommen? | Hai perso recentemente più di 6 kg in un periodo di tre mesi? |

| F (Fat) | Do you believe yourself to be fat when others say you are too thin? | Findest du dich zu dick, während andere dich zu dünn finden? | Ti è mai capitato di sentirti grasso/a anche se gli altri ti dicevano che eri troppo magro/a? |

| F (Food) | Would you say food dominates your life? | Würdest du sagen, dass Essen dein Leben sehr beeinflusst? | Affermeresti che il cibo domina la tua vita? |

Appendix B

| Variable | Male German | Male Italian | Female German | Female Italian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body image “somewhat/much too thick” | 0.250 *** | 0.421 *** | 0.382 *** | 0.416 *** |

| Psychosomatic complaints | 0.120 ** | 0.236 * | 0.351 *** | 0.213 * |

| Parental HLS-score | −0.090 * | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| BSMAS score | 0.105 * | 0.190 * | 0.294 *** | n.s. |

| MSPSS total | −0.112 ** | −0.200 * | −0.121 ** | n.s. |

| MSPSS family | −0.089 * | −0.210 * | −0.211 *** | −0.208 * |

| Parental mental health problems | 0.135 ** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Digital media use (private) | n.s. | n.s. | 0.139 ** | n.s. |

| Child’s health literacy | n.s. | n.s. | −0.140 ** | n.s. |

| HRQoL | n.s. | n.s. | 0.353 *** | −0.265 *** |

| Age | n.s. | n.s. | 0.124 *** | 0.218 * |

| School burden | n.s. | n.s. | 0.172 *** | 0.248 *** |

| General health state | n.s. | n.s. | 0.306 *** | 0.251 ** |

References

- Lin, B.Y.; Moog, D.; Xie, H.; Sun, C.; Deng, W.Y.; McDaid, E.; Liebesny, K.V.; Kablinger, A.S.; Xu, K.Y. Increasing prevalence of eating disorders in female adolescents compared with children and young adults: An analysis of real-time administrative data. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 37, e101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Gao, R.; Kuang, H.; Ranbo, E.; Zhang, C.; Guo, X. Global, regional, and national burdens of eating disorder in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years from 1990 to 2021: A trend analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 388, 119596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne, H.; Kildegaard, H.; Strandberg-Larsen, K.; Rasmussen, L.; Wesselhoeft, R.; Bliddal, M. Eating Disorders in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Danish Nationwide Register-Based Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 57, 2487–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruccoli, J.; Rosa, S.; Chiavarino, F.; Cava, M.; Gazzano, A.; Gualandi, P.; Marino, M.; Moscano, F.; Rossi, F.; Sacrato, L.; et al. Feeding and eating disorders in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Real-word data from an observational, naturalistic study. Minerva Pediatr. 2024; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, G.; Elhadidy, H.S.; Paladini, G.; Onorati, R.; Sciurpa, E.; Gianino, M.M.; Borraccino, A. Eating Disorders in Hospitalized School-Aged Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study of Discharge Records in Developmental Ages in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelletto, P.; Luca, L.D.; Taddei, B.; Taddei, S.; Nocentini, A.; Pisano, T. COVID-19 pandemic impact among adolescents with eating disorders referred to Italian psychiatric unit. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2024, 37, e12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrdes, C.; Göbel, K.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H. [Symptoms of eating disorders in children and adolescents: Frequencies and risk factors: Results from KiGGS Wave 2 and trends]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2019, 62, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, L.; Schröder, R.; Hamer, T.; Suhr, R. Eating disorders and health literacy in Germany: Results from two representative samples of adolescents and adults. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1464651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.F.; Reid, F.; Lacey, J.H. The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999, 319, 1467–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda Jaimes, G.E.; Díaz Martínez, L.A.; Ortiz Barajas, D.P.; Pinzón Plata, C.; Rodríguez Martínez, J.; Cadena Afanador, L.P. [Validation of the SCOFF questionnaire for screening the eating behaviour disorders of adolescents in school]. Aten Primaria 2005, 35, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, C.S.; Lüken, L.M.; Eggendorf, J.; Holtmann, M.; Legenbauer, T. Validation of the SCOFF as a Simple Screening Tool for Eating Disorders in an Inpatient Sample Before and During COVID-19. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 58, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napp, A.-K.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Westenhöfer, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Eating disorder symptoms among children and adolescents in Germany before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1157402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Anna, G.; Lazzaretti, M.; Castellini, G.; Ricca, V.; Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; Silvestri, C.; Voller, F. Risk of eating disorders in a representative sample of Italian adolescents: Prevalence and association with self-reported interpersonal factors. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Kaman, A.; Erhard, M.; Piccoliori, G.; Plagg, B.; Mahlknecht, A.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engl, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents after the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Large Population-Based Survey in South Tyrol, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Piccoliori, G.; Mahlknecht, A.; Plagg, B.; Ausserhofer, D.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Evolution of Youth’s Mental Health and Quality of Life during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Tyrol, Italy: Comparison of Two Representative Surveys. Children 2023, 10, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, V.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Wiedermann, C.J. Parental Mental Health, Gender, and Lifestyle Effects on Post-Pandemic Child and Adolescent Psychosocial Problems: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Northern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecon, R.S.; Franceschini, S.D.C.C.; Peluzio, M.D.C.G.; Hermsdorff, H.H.M.; Priore, S.E. Overweight and Body Image Perception in Adolescents with Triage of Eating Disorders. Sci. World J. 2017, 2017, 8257329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporta-Herrero, I.; Jáuregui-Lobera, I.; Barajas-Iglesias, B.; Serrano-Troncoso, E.; Garcia-Argibay, M.; Santed-Germán, M.Á. Attachment to parents and friends and body dissatisfaction in adolescents with eating disorders. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, I.; Ribovski, M.; Claumann, G.S.; Folle, A.; Beltrame, T.S.; Laus, M.F.; Pelegrini, A. Secular trends in body image dissatisfaction and associated factors among adolescents (2007–2017/2018). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, L.P.; Best, L.A.; Davis, L.L. The role of personality in body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Discrepancies between men and women. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, H.; Scherer, S.; Steinmann, S. The CASMIN Educational Classification in International Comparative Research. In Advances in Cross-National Comparison: A European Working Book for Demographic and Socio-Economic Variables; Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J.H.P., Wolf, C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)—Scale Items and Scoring Information. 2016.

- Barke, A.; Nyenhuis, N.; Kröner-Herwig, B. The German version of the Generalized Pathological Internet Use Scale 2: A validation study. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Primi, C.; Fioravanti, G. Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2: Update on the psychometric properties among Italian young adults. In The Psychology of Social Networking: Identity and Relationships in Online Communities; Riva, G., Wiederhold, B.K., Cipresso, P., Eds.; De Gruyter: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machimbarrena, J.M.; González-Cabrera, J.; Ortega-Barón, J.; Beranuy-Fargues, M.; Álvarez-Bardón, A.; Tejero, B. Profiles of Problematic Internet Use and Its Impact on Adolescents’ Health-Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlack, R.; Hölling, H. Essstörungen im Kindes-und Jugendalter: Erste Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder-und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). In Bundesgesundheitsblatt—Gesundheitsforschung—Gesundheitsschutz; Epidemiologie und Gesundheitsberichterstattung; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2007; Volume 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannocchia, L.; Di Fiorino, M.; Giannini, M.; Vanderlinden, J. A psychometric exploration of an Italian translation of the SCOFF questionnaire. In European Eating Disorders Review; Eating Disorders Association (Great Britain): New York, NY, USA; John Wiley&Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISSN 1099-09681.38. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/050-001l_S3_Praevention-Therapie-Adipositas_2024-10.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Paakkari, L.; Torppa, M.; Mazur, J.; Boberova, Z.; Sudeck, G.; Kalman, M.; Paakkari, O. A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Herdman, M.; Devine, J.; Otto, C.; Bullinger, M.; Rose, M.; Klasen, F. The European KIDSCREEN approach to measure quality of life and well-being in children: Development, current application, and future advances. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian. Kidscreen.org. Available online: http://www.kidscreen.org/contacts/italian/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Zarate, D.; Hobson, B.A.; March, E.; Griffiths, M.D.; Stavropoulos, V. Psychometric properties of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale: An analysis using item response theory. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2023, 17, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Sa’at, N.; Sidik, T.M.I.T.A.B.; Joo, L.C. Sample Size Guidelines for Logistic Regression from Observational Studies with Large Population: Emphasis on the Accuracy Between Statistics and Parameters Based on Real Life Clinical Data. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispas, A.G.; Forray, A.I.; Lacurezeanu, A.; Petreuș, D.; Gavrilaș, L.I.; Cherecheș, R.M. Eating Disorder Risk Among Adolescents: The Influence of Dietary Patterns, Physical Activity, and BMI. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Arshad, A.; Hussain, A.; Hashmi, A. Screening of Eating Disorders Among Adolescents: A Study from Pakistan. Int. J. Health Sci. 2023, 7, 1881–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamay-Weber, C.; Narring, F.; Michaud, P.-A. Partial eating disorders among adolescents: A review. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 37, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, N.H.; Katzman, D.K.; Kreipe, R.E.; Stevens, S.L.; Sawyer, S.M.; Rees, J.; Nicholls, D.; Rome, E.S. Eating disorders in adolescents: Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 33, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micali, N.; Solmi, F.; Horton, N.J.; Crosby, R.D.; Eddy, K.T.; Calzo, J.P.; Sonneville, K.R.; Swanson, S.A.; Field, A.E. Adolescent Eating Disorders Predict Psychiatric, High-Risk Behaviors and Weight Outcomes in Young Adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 652–659.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebeile, H.; Lister, N.B.; Baur, L.A.; Garnett, S.P.; Paxton, S.J. Eating disorder risk in adolescents with obesity. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarraj, S.; Berry, S.L.; Burton, A.L. A Scoping Review of Eating Disorder Prevention and Body Image Programs Delivered in Australian Schools. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Shaw, H.; Marti, C.N. A meta-analytic review of eating disorder prevention programs: Encouraging findings. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, S.L.; Burton, A.L.; Rogers, K.; Lee, C.M.; Berle, D.M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of eating disorder preventative interventions in schools. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2025, 33, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S.; Chan, B.N.K.; Lai, S.I.; Tung, K.T.S. School-based eating disorder prevention programmes and their impact on adolescent mental health: Systematic review. BJPsych Open 2024, 10, e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickhardt, M.; Adametz, L.; Richter, F.; Strauß, B.; Berger, U. [German Prevention Programs for Eating Disorders—A Systematic Review]. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2019, 69, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grave, R.D. School-based prevention programs for eating disorders: Achievements and opportunities. In Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-Assessed Reviews; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK): York, UK, 2003. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK70226/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Garcia, F.D.; Grigioni, S.; Chelali, S.; Meyrignac, G.; Thibaut, F.; Dechelotte, P. Validation of the French version of SCOFF questionnaire for screening of eating disorders among adults. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 11, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Campayo, J.; Sanz-Carrillo, C.; Ibañez, J.A.; Lou, S.; Solano, V.; Alda, M. Validation of the Spanish version of the SCOFF questionnaire for the screening of eating disorders in primary care. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 59, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.F.; Lee, K.L.; Lee, S.M.; Leung, S.C.; Hung, W.S.; Lee, W.L.; Leung, Y.Y.; Li, M.W.; Tse, T.K.; Wong, H.K.; et al. Psychometric properties of the SCOFF questionnaire (Chinese version) for screening eating disorders in Hong Kong secondary school students: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzazian, S.; Ozgoli, G.; Kariman, N.; Nasiri, M.; Mokhtaryan-Gilani, T.; Hajiesmaello, M. The translation and psychometric assessment of the SCOFF eating disorder screening questionnaire: The Persian version. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, Y.; Ohtani, T.; Hanazawa, H.; Tanaka, M.; Kimura, H.; Ohsako, N.; Hashimoto, T.; Kobori, O.; Iyo, M.; Nakazato, M. Establishment of a Japanese version of the Sick, Control, One Stone, Fat, and Food (SCOFF) questionnaire for screening eating disorders in university students. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M.B.; Hemmingsen, S.D.; Støving, R.K. Identification of eating disorder symptoms in Danish adolescents with the SCOFF questionnaire. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2017, 71, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.A.; Roque, M.A.; de Freitas, A.A.; Dos Santos, N.F.; Garcia, F.M.; Khoury, J.M.; Albuquerque, M.R.; das Neves, M.; Garcia, F.D. The Brazilian version of the SCOFF questionnaire to screen eating disorders in young adults: Cultural adaptation and validation study in a university population. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2021, 43, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutz, A.M.; Marsh, A.G.; Gunderson, C.G.; Maguen, S.; Masheb, R.M. Eating Disorder Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Characteristics of the SCOFF. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coop, A.; Clark, A.; Morgan, J.; Reid, F.; Lacey, J.H. The use and misuse of the SCOFF screening measure over two decades: A systematic literature review. Eat. Weight Disord. 2024, 29, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekola, A.; Regassa, L.D.; Mandefro, M.; Shawel, S.; Kassa, O.; Shasho, F.; Demis, T.; Masrie, A.; Tamire, A.; Roba, K.T. Body image dissatisfaction is associated with perceived body weight among secondary school adolescents in Harar Town, eastern Ethiopia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1397155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beese, S.E.; Harris, I.M.; Dretzke, J.; Moore, D. Body image dissatisfaction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019, 6, e000255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffoul, A.; Turner, S.L.; Salvia, M.G.; Austin, S.B. Population-level policy recommendations for the prevention of disordered weight control behaviors: A scoping review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 1463–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Plagg, B.; Marino, P.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Fortifying the Foundations: A Comprehensive Approach to Enhancing Mental Health Support in Educational Policies Amidst Crises. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Males | Underweight (%) | Normal (%) | Overweight (%) | |||

| Proxy 11–17 | Self 11–17 | Proxy 11–17 | Self 11–17 | Proxy 11–17 | Self 11–17 | |

| Much too thin | 3.1 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Somewhat too thin | 39.2 | 37.1 | 14.3 | 16.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Right weight | 56.7 | 55.7 | 76.7 | 72.2 | 40.0 | 27.7 |

| Somewhat too thick | 0.0 | 2.1 | 7.4 | 8.5 | 50.8 | 61.5 |

| Much too thick | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 9.2 | 10.8 |

| Females | Underweight (%) | Normal (%) | Overweight (%) | |||

| Proxy 11–17 | Self 11–17 | Proxy 11–17 | Self 11–17 | Proxy 11–17 | Self 11–17 | |

| Much too thin | 4.0 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 |

| Somewhat too thin | 19.2 | 23.2 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Right weight | 69.6 | 62.4 | 80.1 | 71.1 | 33.9 | 16.9 |

| Somewhat too thick | 6.4 | 9.6 | 15.7 | 22.9 | 57.6 | 76.3 |

| Much too thick | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 8.5 | 5.1 |

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCOFF Normal | SCOFF Symptomatic | SCOFF Normal | SCOFF Symptomatic | |

| Total | 94% | 6% | 83% | 17% |

| Underweight | ||||

| Much too thin | 4 (100%) | 0 | 3 (100%) | 0 |

| Too thin | 31 (100%) | 0 | 22 (100%) | 0 |

| Normal | 50 (98.0%) | 1 (2%) | 62 (91.2%) | 6 (8.8%) |

| Somewhat too thick | 1 (100%) | 0 | 5 (45.5%) | 6 (54.5%) |

| Much too thick | 0 | 1 (100%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) |

| Normal weight | ||||

| Much too thin | 8 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Too thin | 82 (96.5%) | 3 (3.5%) | 19 (90.5%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Normal | 380 (97.2%) | 11 (2.8%) | 345 (91.8%) | 31 (8.2%) |

| Somewhat too thick | 40 (81.6%) | 9 (18.4%) | 76 (62.3%) | 46 (37.7%) |

| Much too thick | 4 (80%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Overweight | ||||

| Much too thin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

| Normal | 17 (94.4%) | 1 (5.6%) | 8 (100%) | 0 |

| Somewhat too thick | 34 (87.2%) | 5 (12.8%) | 28 (65.1%) | 15 (34.9%) |

| Much too thick | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) |

| Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | |

| BSMAS score | 1.11 [1.03; 1.20] | 0.009 | 1.12 [1.06; 1.18] | <0.001 |

| MSPSS score | 0.75 [0.60; 0.92] | 0.006 | n.s. | |

| Body image too thick | 11.61 [5.57; 24.19] | <0.001 | 5.34 [3.25; 8.76] | <0.001 |

| Number of psychosomatic complaints | 1.27 [1.12; 1.44] | <0.001 | ||

| Age | n.s. | |||

| General health state | 1.64 [1.20; 2.24] | 0.002 | ||

| Nagelkerkes’ R2 | 0.237 | 0.363 | ||

| Hoshmer-Lemeshow | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| Area under the ROC curve | 0.511 | n.s. | 0.645 | <0.001 |

| N | 652 | 620 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbieri, V.; Zöbl, M.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Hager-von Strobele-Prainsack, D.; Wiedermann, C.J. Adolescent Eating Disorder Risk in a Bilingual Region: Clinical Prevalence, Screening Challenges and Treatment Gap in South Tyrol, Italy. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223549

Barbieri V, Zöbl M, Piccoliori G, Engl A, Hager-von Strobele-Prainsack D, Wiedermann CJ. Adolescent Eating Disorder Risk in a Bilingual Region: Clinical Prevalence, Screening Challenges and Treatment Gap in South Tyrol, Italy. Nutrients. 2025; 17(22):3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223549

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbieri, Verena, Michael Zöbl, Giuliano Piccoliori, Adolf Engl, Doris Hager-von Strobele-Prainsack, and Christian J. Wiedermann. 2025. "Adolescent Eating Disorder Risk in a Bilingual Region: Clinical Prevalence, Screening Challenges and Treatment Gap in South Tyrol, Italy" Nutrients 17, no. 22: 3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223549

APA StyleBarbieri, V., Zöbl, M., Piccoliori, G., Engl, A., Hager-von Strobele-Prainsack, D., & Wiedermann, C. J. (2025). Adolescent Eating Disorder Risk in a Bilingual Region: Clinical Prevalence, Screening Challenges and Treatment Gap in South Tyrol, Italy. Nutrients, 17(22), 3549. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223549