Eating Attitudes, Body Appreciation, Perfectionism, and the Risk of Exercise Addiction in Physically Active Adults: A Cluster Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Exercise Addiction

2.2.2. Eating Attitudes

2.2.3. Orthorexic Behavior

2.2.4. Body Appreciation

2.2.5. Perfectionism

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Bivariate Associations

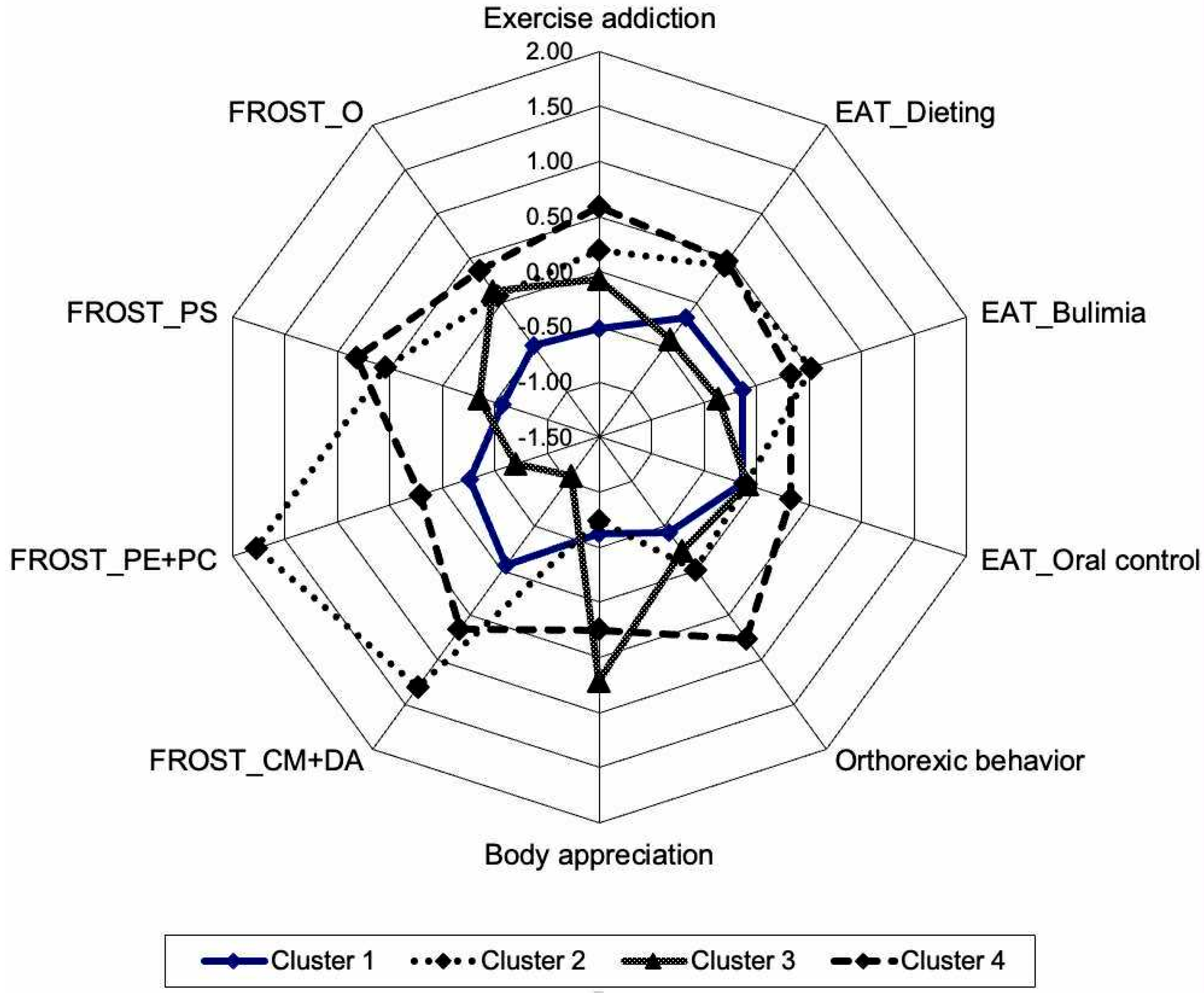

3.3. Cluster Analysis

3.4. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EA | Exercise addiction |

| DE | Disordered eating |

| AN | Anorexia nervosa |

| ON | Orthorexia nervosa |

| EAI-R | Exercise Addiction Inventory—Revised |

| EAT | Eating Attitude Test |

| BAS | Body Appreciation Scale |

| FMPS | Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale |

| FROST | Frost Perfectionism Scale |

| O | Organization |

| PS | Personal Standards |

| PE | Parental Expectations |

| PC | Parental Criticism |

| CM | Concern over Mistakes |

| DA | Doubts about Actions |

References

- Faghy, M.A.; Tatler, A.; Chidley, C.; Fryer, S.; Stoner, L.; Laddu, D.; Arena, R.; Ashton, R.E. The physiologic benefits of optimizing cardiorespiratory fitness and physical activity—From the cell to systems level in a post-pandemic world. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 83, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagodi, F.; Dommett, E.J.; Findon, J.L.; Gardner, B. Physical activity interventions to improve mental health and wellbeing in university students in the UK: A service mapping study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2024, 26, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Lee, S.; Yon, D.K.; Lee, S.W.; Udeh, R.; McEvoy, M.; Oh, H.; Butler, L.; Keyes, H.; Barnett, Y.; et al. Physical activity and prevention of mental health complications: An umbrella review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 160, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibsen, B.; Elmose-Řsterlund, K.; Hřyer-Kruse, J. Associations of types of physical activity with self-rated physical and mental health in Denmark. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 37, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sańudo, B.; Sanchez-Trigo, H.; Domínguez, R.; Flores-Aguilar, G.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.; Moral, J.E.; Oviedo-Car, M.Á. A randomized controlled mHealth trial that evaluates social comparison-oriented gamification to improve physical activity, sleep quantity, and quality of life in young adults. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2024, 72, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats-Arimon, M.; Puig-Llobet, M.; Barceló-Peiró, O.; Ribot-Domčnech, I.; Vilalta-Sererols, C.; Fontecha-Valero, B.; Heras-Ojeda, M.; Agüera, Z.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Moreno-Poyato, A.; et al. An Interdisciplinary intervention based on prescription of physical activity, diet, and positive mental health to promote healthy lifestyle in patients with obesity: A randomized control trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamroonsawasdi, K.; Chottanapund, S.; Pamungkas, R.A.; Tunyasitthisundhorn, P.; Sornpaisarn, B.; Numpaisan, O. Protection motivation theory to predict intention of healthy eating and sufficient physical activity to prevent diabetes mellitus in Thai population: A path analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2021, 15, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkiewicz, A.; Magnusson, K.; Timpka, S.; Kiadaliri, A.; Dell’Isola, A.; Englund, M. Physical health in young males and risk of chronic musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases by middle age: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2025, 22, e1004517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M.B.; Hinze, C.J.; Emborg, B.; Thomsen, F.; Hemmingsen, S.D. Compulsive exercise: Links, risks and challenges faced. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenblas, H.A.; Giacobbi, P.R., Jr. Relationship between exercise dependence symptoms and personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Hřglid, R.A.; Demetrovics, Z. Drug, nicotine, and alcohol use among exercisers: Does substance addiction co-occur with exercise addiction? Addict. Behav. Rep. 2018, 7, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasser, W. Positive Addiction; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-J. Frequent exercise: A healthy habit or a behavioral addiction? Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2016, 2, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, W.P. Negative addiction in runners. Phys. Sportsmed. 1979, 7, 7–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecker, H.; Sprenger, T.; Spilker, M.E.; Henriksen, G.; Koppenhoefer, M.; Wagner, K.J.; Valet, M.; Berthele, A.; Tolle, T.R. The runner’s high: Opioidergic mechanisms in the human brain. Cereb. Cortex 2008, 18, 2523–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M.D. A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Us 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Coverley Veale, D.M. Exercise dependence. Br. J. Addict. 1987, 82, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Szabo, A. Exercise addiction: A narrative overview of research issues. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.; Luke, R. Primary and secondary exercise dependence in a sample of cyclists. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 15, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Imani, V.; Potenza, M.N.; Chen, H.-P.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Mediating roles of psychological distress, insomnia, and body image concerns in the association between exercise addiction and eating disorders. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 2533–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R.; Rutkauskaite, R. The comparison of disordered eating, body image, sociocultural and coach-related pressures in athletes across age groups and groups of different weight sensitivity in sports. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lodovico, L.; Dubertret, C.; Ameller, A. Vulnerability to exercise addiction, socio-demographic, behavioral and psychological characteristics of runners at risk for eating disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 81, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Izquierdo, D.; Remírez, M.J.; Díaz, I.; López-Mora, C. A systematic review on exercise addiction and the disordered eating-eating disorders continuum in the competitive sport context. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 529–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Thang, G.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y. Athlete body image and eating disorders: A systematic review of their association and influencing factors. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levit, M.; Weinstein, A.; Weinstein, Y.; Tzur-Bitan, D.; Weinstein, A. A study on the relationship between exercise addiction, abnormal eating attitudes, anxiety and depression among athletes in Israel. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 73, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freimuth, M.; Moniz, S.; Kim, S.R. Clarifying exercise addiction: Differential diagnosis, co-occurring disorders, and phases of addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 4069–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M.B.; Christiansen, E.; Elklit, A.; Bilenberg, N.; Střving, R.K. Exercise addiction: A study of eating disorder symptoms, quality of life, personality traits and attachment styles. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 215, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, V.B.; Hill, A.P.; Madigan, D.J. A longitudinal study of perfectionism and orthorexia in exercisers. Appetite 2023, 183, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berengüí, R.; Angosto, S.; Hernández-Ruiz, A.; Rueda-Flores, M.; Castejón, M.A. Body image and eating disorders in aesthetic sports: A systematic review of assessment and risk. Sci. Sports 2024, 39, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.O.; Marten, P.; Lahart, C.; Rosenblate, R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1990, 14, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.O.; Heimberg, R.G.; Holt, C.S.; Mattia, J.I.; Neubauer, A.L. A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1993, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynos, A.F.; Utzingerm, L.M.; Lavender, J.M.; Crosby, R.D.; Cao, L.; Peterson, C.B.; Crow, S.J.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Engel, S.G.; Mitchell, J.E.; et al. Subtypes of adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism in anorexia nervosa: Associations with eating disorder and affective symptoms. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2018, 40, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limburg, K.; Watson, H.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Egan, S.J. The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackpole, R.; Greene, D.; Bills, E.; Egan, S.J. The association between eating disorders and perfectionism in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat. Behav. 2023, 50, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, S.E.; Mills, J.S. Orthorexia nervosa: A review of psychosocial risk factors. Appetite 2019, 140, 50–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piko, B.F.; Kulmán, E.; Mellor, D. Orthorexic tendency in light of eating disorder attitudes, social media addiction and regular sporting among young Hungarian women. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 45, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.K.; Hill, A.P.; Appleton, P.R.; Kozub, S.A. The mediating influence of unconditional self-acceptance and labile self-esteem on the relationship between multidimensional perfectionism and exercise dependence. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Cyr, J.; Gavrila, A.; Tanguay-Sela, M.; Vallerand, R.J. Perfectionism, disordered eating and well-being in aesthetic sports: The mediating role of passion. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2024, 73, 102648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.D.; Aron, C.M. A perfect storm for athletes—Body dysmorphia, problematic exercise, eating disorders, and other influences. Adv. Psychiatry Behav. Health 2024, 4, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, A.; Alcaraz-Ibańez, M.; Chiminazzo, J.G.C.; Fernandes, P.T. Latent profile analysis of exercise addiction symptoms in Brazilian adolescents: Association with health-related variables. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 273, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-J.; Zhao, K.; Fils-Aime, F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A. Model fit and reliability of the Hungarian version of the Revised Exercise Addiction Inventory (EAI-R-HU). J. Ment. Health Psychosom. 2021, 22, 376–394. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Pinto, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kovacsik, R.; Demetrovics, Z. The psychometric evaluation of the Revised Exercise Addiction Inventory: Improved psychometric properties by changing item response rating. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, A.; Szabo, A.; Griffiths, M. The exercise addiction inventory: A new brief screening tool. Addict. Res. Theory 2004, 12, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Túry, F.; Kollár, M.; Szabó, P. Táplálkozási attitűdök középiskolások között [Eating attitudes among highschool students]. Ideggyógy Szeml. 1991, 44, 173–181. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthels, F.; Meyer, F.; Pietrowsky, R. Die Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala—Konstruktion und Evaluation eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung orthorektischen Ernährungsverhaltens [Duesseldorf orthorexia scale—Construction and evaluation of a questionnaire measuring orthorexic eating behavior]. Z. Klin. Psych. Psychother. 2015, 44, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chard, C.A.; Hilzendegen, C.; Barthels, F.; Stroebele-Benschop, N. Düsseldorfer Orthorexie Skala Psychometric evaluation of the English version of the Düsseldorf Orthorexie Scale (DOS) and the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among a U.S. student sample. Eat. Weight Disord. 2019, 24, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béres, A.; Czeglédi, E.; Babusa, B. Examination of exercise dependence and body image in female fitness exercisers. J. Ment. Health Psychosom. 2013, 14, 91–114. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N.L. The body appreciation scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2015, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobos, B.; Piko, B.F.; Kenny, D.T. Music performance anxiety and its relationship with social phobia and dimensions of perfectionism. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2019, 41, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöber, J. The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale: More perfect with four (instead of six) dimensions. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 24, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. Chapter 15: Cluster Analysis. Int. Geophys. 2011, 100, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Madigan, D.J. A short review of perfectionism in sport, dance and exercise: Out with the old, in with the 2 × 2. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siska, D.; Cserép, M.; Szabó, B. Eating attitudes among Hungarian adolescents. Hung. Med. J. 2023, 164, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wider, W.; Mutang, J.A.; Chua, B.S.; Lin, J.; Kamu, A.; Pang, N.T.P. Assessing the factor structure of the Eating Attitude Test-26 among undergraduate students in Malaysia. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1212919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 47 (22.9) |

| Female | 158 (77.1) |

| Employment status | |

| White collar | 98 (47.8) |

| Blue collar | 21 (10.2) |

| Student | 86 (42.0) |

| Length of exercise time (years) | |

| 1 year or less | 40 (19.5) |

| 2–3 years | 24 (11.7) |

| 3–5 years | 17 (8.3) |

| 5–10 years | 37 (18.0) |

| >10 years | 87 (42.4) |

| Exercise on days/week | |

| 1–2 days | 86 (42.0) |

| 3–4 days | 90 (43.9) |

| 5 days of more | 29 (14.1) |

| Exercise time per occasion | |

| 1 h or less | 72 (35.1) |

| 1–2 h | 114 (55.6) |

| 3–5 h | 16 (7.8) |

| >5 h | 3 (1.5) |

| More than one occasion a day | |

| No | 126 (61.5) |

| Yes | 79 (38.5) |

| Level of exercise | |

| Hobby | 183 (89.3) |

| Competitive | 22 (10.7) |

| Min–Max | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exercise addiction | 6–35 | 19.30 (6.16) | 0.13 | −0.35 |

| 2. EAT—Dieting | 0–31 | 6.27 (6.38) | 1.35 | 1.50 |

| 3. EAT—Bulimia | 0–11 | 0.96 (1.86) | 2.69 | 8.20 |

| 4. EAT—Oral control | 0–18 | 2.31 (2.51) | 2.65 | 11.31 |

| 5. Orthorexic behavior | 10–33 | 18.29 (5.04) | 0.60 | 0.18 |

| 6. Body appreciation | 15–50 | 35.60 (8.05) | −0.54 | −0.26 |

| 7. Concern over Mistakes + Doubts about Actions | 13–65 | 36.53 (12.31) | 0.10 | −0.62 |

| 8. Parental Expectations + Parental Criticism | 9–45 | 20.28 (9.14) | 0.74 | −0.21 |

| 9. Personal Standards | 9–35 | 23.90 (6.12) | −0.18 | −0.75 |

| 10. Organization | 6–30 | 23.87 (4.81) | −0.78 | 0.33 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exercise addiction | (0.79) # | |||||||||

| 2. EAT—Dieting | 0.34 *** | (0.79) | ||||||||

| 3. EAT—Bulimia | 0.27 *** | 0.64 *** | (0.70) | |||||||

| 4. EAT—Oral Control | 0.15 * | 0.20 ** | 0.31 *** | (0.60) | ||||||

| 5. Orthorexic behavior | 0.48 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.19 ** | (0.80) | |||||

| 6. Body appreciation | 0.05 | −0.37 *** | −0.29 *** | 0.09 | 0.07 | (0.96) | ||||

| 7. Concern over Mistakes + Doubts about Actions | 0.21 ** | 0.32 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.13 | 0.27 *** | −0.35 *** | (0.92) | |||

| 8. Parental Expectations + Parental Criticism | 0.15 * | 0.17 * | 0.17 * | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.22 ** | 0.58 *** | (0.92) | ||

| 9. Personal Standards | 0.25 *** | 0.24 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.39 *** | 0.14 * | 0.51 *** | 0.31 *** | (0.83) | |

| 10. Organization | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.21 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.27 *** | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.53 *** | (0.89) |

| CLUSTER 1 Mean (SD) z-Score | CLUSTER 2 Mean (SD) z-Score | CLUSTER 3 Mean (SD) z-Score | CLUSTER 4 Mean (SD) z-Score | F-Value | η2p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise addiction | 16.11 (4.61) −0.52 | 20.46 (6.61) 0.19 | 18.86 (6.17) −0.07 | 22.96 (5.46) 0.59 | 14.36 ** | 0.18 |

| EAT—Dieting | 5.20 (5.58) −0.17 | 8.93 (7.42) 0.42 | 3.67 (3.64) −0.41 | 9.29 (7.59) 0.47 | 11.03 ** | 0.14 |

| EAT—Bulimia | 0.72 (1.51) −0.13 | 1.93 (2.24) 0.52 | 0.28 (0.72) −0.36 | 1.54 (2.52) 0.32 | 8.15 ** | 0.11 |

| EAT—Oral Control | 1.95 (1.89) −0.14 | 2.07 (2.87) −0.10 | 2.09 (1.81) −0.09 | 3.13 (3.42) 0.33 | 2.58 * | 0.04 |

| Orthorexic behavior | 16.20 (3.95) −0.42 | 18.29 (5.02) −0.001 | 17.16 (4.11) −0.22 | 22.15 (5.21) 0.77 | 18.57 ** | 0.22 |

| Body appreciation | 30.59 (6.93) −0.62 | 29.61 (7.76) −0.74 | 41.36 (5.51) 0.71 | 37.63 (6.17) 0.25 | 39.07 ** | 0.37 |

| Concern over Mistakes + Doubts about Actions | 35.84 (7.01) −0.06 | 52.71 (8.31) 1.31 | 23.52 (6.01) −1.06 | 44.63 (6.55) 0.66 | 156.12 ** | 0.67 |

| Parental Expectations + Parental Criticism | 17.90 (6.29) −0.26 | 36.54 (5.06) 1.78 | 13.89 (5.16) −0.70 | 22.17 (5.88) 0.21 | 108.57 ** | 0.62 |

| Personal Standards | 20.29 (4.89) −0.57 | 27.18 (4.51) 0.54 | 21.72 (5.72) −0.36 | 28.92 (4.26) 0.82 | 35.97 ** | 0.35 |

| Organization | 21.54 (5.24) −0.48 | 24.25 (4.73) 0.08 | 24.53 (4.53) 0.14 | 25.60 (3.60) 0.36 | 8.25 ** | 0.11 |

| Percentage (n) | 29.76% (61) | 13.66% (28) | 31.22% (64) | 25.36% (52) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piko, B.F.; Berki, T.L.; Kun, O.; Mellor, D. Eating Attitudes, Body Appreciation, Perfectionism, and the Risk of Exercise Addiction in Physically Active Adults: A Cluster Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132063

Piko BF, Berki TL, Kun O, Mellor D. Eating Attitudes, Body Appreciation, Perfectionism, and the Risk of Exercise Addiction in Physically Active Adults: A Cluster Analysis. Nutrients. 2025; 17(13):2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132063

Chicago/Turabian StylePiko, Bettina F., Tamás L. Berki, Orsolya Kun, and David Mellor. 2025. "Eating Attitudes, Body Appreciation, Perfectionism, and the Risk of Exercise Addiction in Physically Active Adults: A Cluster Analysis" Nutrients 17, no. 13: 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132063

APA StylePiko, B. F., Berki, T. L., Kun, O., & Mellor, D. (2025). Eating Attitudes, Body Appreciation, Perfectionism, and the Risk of Exercise Addiction in Physically Active Adults: A Cluster Analysis. Nutrients, 17(13), 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132063