Mental Health and Body Image and the Reduction of Excess Body Weight in Woman (Polish Sample)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

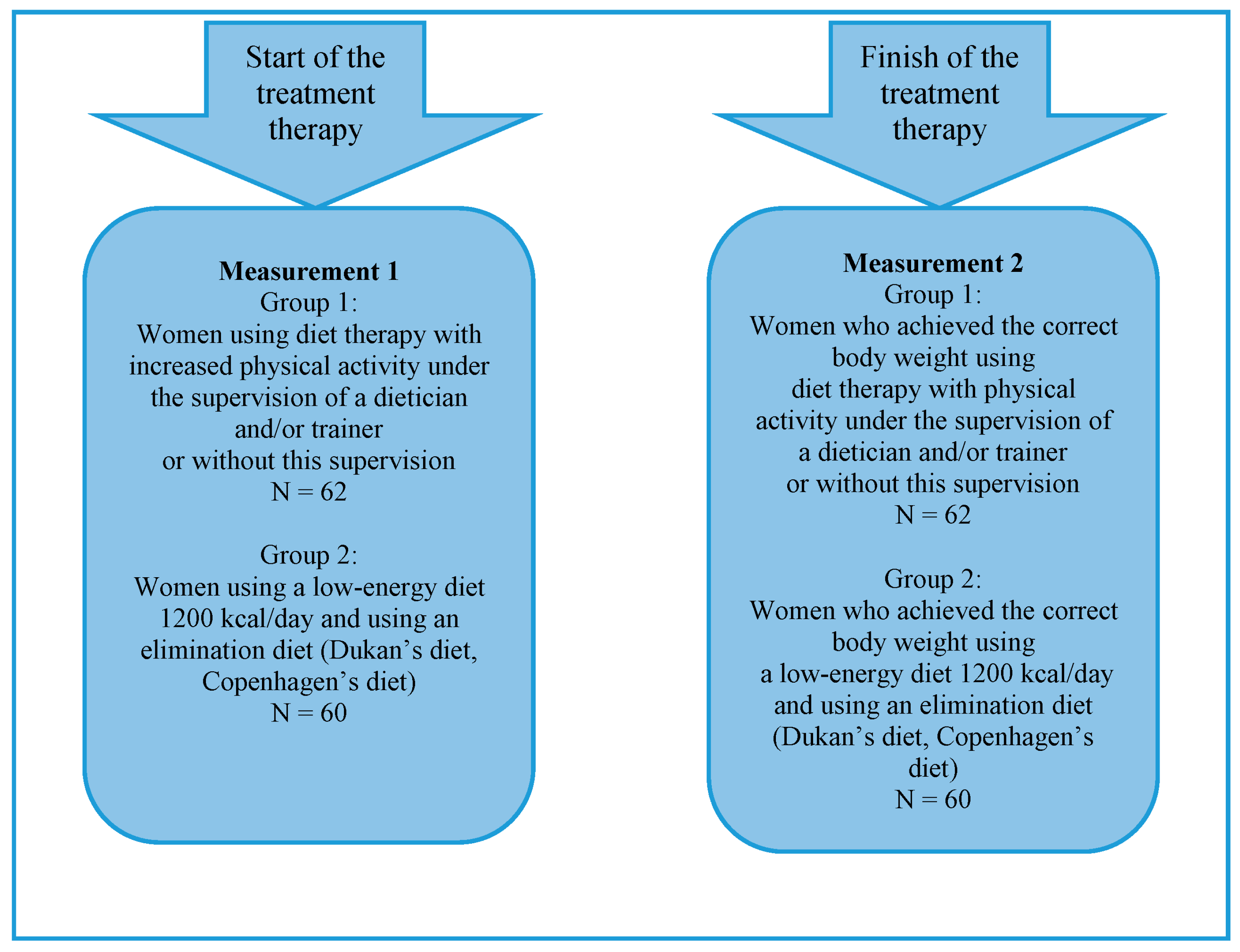

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences between the Means in Terms of the Studied Variables before and after the Start of the Weight Loss Therapies

3.2. Differences between the Studied Variables in Two Separate Study Groups of Women before and after Weight Loss Therapies

3.3. Relationships between Body Assessment and the Level of Mental Health in the Group of Surveyed Women

4. Discussion

5. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miniszewska, J.; Kogut, K. Social competence and the need for approval and life satisfaction of women with excess body weight and women of normal weight—preliminary report. Curr. Probl. Psychiatry 2016, 17, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigos, C.; Hainer, V.; Basdevant, A.; Finer, N.; Fried, M.; Mathus-Vliegen, E.; Micic, D.; Maislos, M.; Roman, G.; Schutz, Y.; et al. Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity. Management of obesity in adults: European clinical practice guidelines. Obes. Facts 2008, 1, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Obesity Federation. Available online: https://www.worldobesity.org/resources/resource-library/world-obesity-atlas-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Otyłość w UE, Polsce i na świecie. Choroba XXI wieku. Available online: https://demagog.org.pl/analytic_i_raporty/otylosc-w-ue-polsce-i-na-swiecie-choroba-xxi-wie/ (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Ponury raport NIK na temat otyłości w Polsce. Available online: https://zdrowie.dziennik.pl/aktualnosci/artykuly/9449453,ponury-raport-nik-na-temat-otylosci-w-polsce-tam-jest-najgorzej-mapa.html#otylosc-w-polsce- (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Women in Poland; GUS CSO: Warszawa, Polska, 2007.

- Swami, V.; Frederick, D.A.; Aavik, T.; Alcalay, L.; Allik, J.; Anderson, D.; Andrianto, S.; Arora, A.; Brännström, Å.; Cunningham, J.; et al. The Attractive Female Body Weight and Female Body Dissatisfaction in 26 Countries Across 10 World Regions: Results of the International Body Project, I. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Zamacona, M.; Poveda, A.; Rebato, E. Body image in relation to nutritional status in adults from the Basque Country, Spain. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2020, 52, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadzadeh, A.S.; Rafik-Galea, S.; Alavi, M.; Amini, M. Relationship between body mass index, body image, and fear of negative evaluation: Moderating role of self-esteem. Health Psychol. Open 2018, 5, 2055102918774251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricatore, A.N.; Wadden, T.A. Psychological aspects of obesity. Clin. Dermatol. 2004, 22, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziółkowska, B. Psychologia zaburzeń odżywiania. In Psychologia Kliniczna; Cierpiałkowska, L., Sęk, H., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Polska, 2017; pp. 407–426. ISBN 978-83-01-18825-2. [Google Scholar]

- Flegal, K.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Overweight, Mortality and Survival. Obesity 2013, 21, 1744–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremner, J.D.; Moazzami, K.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Nye, J.A.; Lima, B.B.; Gillespie, C.F.; Rapaport, M.H.; Pearce, B.D.; Shah, A.J.; Vaccarino, V. Diet, Stress and Mental Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paans, N.P.G.; Bot, M.; Brouwer, I.A.; Visser, M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Contributions of depression and body mass index to body image. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 103, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.A.; Brownell, K.D. Psychological correlates of obesity: Moving to the next research generation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.; Knafl, K.A. Dimensional analysis of the concept of obesity. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 54, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amianto, F. Non-surgical Weight Loss and Body Image Changes in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. In Body Image, Eating, and Weight; Cuzzolaro, M., Fassino, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, N.-A.; Kersting, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Luck-Sikorski, C. The Relationship between Weight Status and Depressive Symptoms in a Population Sample with Obesity: The Mediating Role of Appearance Evaluation. Obes. Facts 2018, 11, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, T.E.; McCabe, M.P. Relationships between men’s and women’s body image and their psychological, social and sexual functioning. Sex Roles A J. Res. 2005, 52, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtala, J.C.; Fardouly, J. Does medium matter? Investigating the impact of viewing ideal image or short-form video content on young women’s body image, mood, and self objectification. Body Image 2023, 46, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronne, L.J.; Brown, W.V.; Isoldi, K.K. Cardiovascular disease in obesity: A review of related risk factors and risk-reduction strategies. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2007, 1, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poobalan, A.; Aucott, L.; Smith, W.C.; Avenell, A.; Jung, R.; Broom, J.; Grant, A.M. Effects of weight loss in overweight/obese individuals and long-term lipid outcomes—A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2004, 5, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.D.; Wadden, T.A.; Kendall, P.C.; Stunkard, A.J.; Vogt, R.A. Psychological effects of weight loss and regain: A prospective evaluation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, K.R.; Barofsky, I.; Cheskin, L.J. Predictors of quality of life for obese persons. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1997, 185, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, M. Quality of life and psychological well-being in obesity management: Improving the odds of success by managing distress. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2016, 70, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolotkin, R.L.; Andersen, J.R. A systematic review of reviews: Exploring the relationship between obesity, weight loss and health-related quality of life. Clin. Obes. 2017, 7, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronne, L.J. Therapeutic options for modifying cardiometabolic risk factors. Am. J. Med. 2007, 120 (Suppl. S1), 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Białek-Dratwa, A.; Sobczyk, K.; Grot, M.; Kowalski, O.; Staśkiewicz, W. Nutrition and mental health: A review of current knowledge about the impact of diet on mental health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 943998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice; (Summary Report); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Tydzień Zdrowia Kobiet. Available online: https://pacjent.gov.pl/zapobiegaj/zadbaj-o-woje-zdrowie-psychiczne (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Ogden, J. The Psychology of Eating: From Healthy to Disordered Behavior, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Flegal, K.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Kit, B.K.; Ogden, C.L. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA 2012, 307, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szreder, M. O weryfikacji i falsyfikacji hipotez. Przegląd Stat. 2010, 2–3, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Franzoi, S.L.; Shields, S.A. The Body-Esteem Scale: Multidimensional structure and sex differences in a college population. J. Personal. Assess. 1984, 48, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowska, M.; Lipowski, M. Polish normalization of the Body Esteem Scale. Health Psychol. Rep. 2013, 1, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.P. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire; NFER-NELSON Publishers: Windsor, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Makowska, Z.; Merecz, D.; Mościcka, A.; Kolasa, W. The validity of general health questionnaires, GHO-12 and GHO-28, in mental health studies of working people. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2001, 15, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lipowska, M.; Lipowski, M. The evaluation of own attractiveness by females of different age. In The Woman in the Culture—The Culture in the Woman; Chybicka, A., Kaźmierczak, M., Eds.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls: Kraków, Poland, 2006; pp. 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Flegal, K.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Ogden, C.L.; Curtin, L.R. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 288, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwierzchowska, A. BAI (Body Adiposity Index)—Nowy wskaźnik interpretacji otłuszczenia w programie promocji zdrowia. In W: Promocja Zdrowia Wyzwaniem XXI; Tracz, W., Kapserczyk, T., Eds.; Krakowska Wyższa Szkoła Promocji Zdrowia: Kraków, Poland, 2012; pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Melmer, A.; Lamina, C.; Tschoner, A.; Ress, C.; Kaser, S.; Laimer, M.; Sandhofer, A.; Paulweber, B.; Ebenbichler, C.F. Body adiposity index and other indexes of body composition in the SAPHIR study: Association with cardiovascular risk factors. Obesity 2013, 21, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Cooper, J.A. Validation study of the body adiposity index as a predictor of percent body fat in older individuals: Findings from the BLSA. J. Gerontol A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geliebter, A.; Atalayer, D.; Flancbaum, L.; Gibson, C.D. Comparison of body adiposity index (BAI) and BMI with estimations of % body fat in clinically severe obese women. Obesity 2013, 21, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinknes, K.J.; Elshorbagy, A.K.; Drevon, C.A.; Gjesdal, C.G.; Tell, G.S.; Nygård, O.; Vollset, S.E.; Refsum, H. Evaluation of the body adiposity index in a Caucasian population: The Hordaland Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, J.; Stachowski, R. Zastosowanie Analizy Wariancji w Eksperymentalnych Abdanich Psychologicznych; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, M.; Darimont, C.; Panahi, S.; Drapeau, V.; Marette, A.; Taylor, V.H.; Doré, J.; Tremblay, A. Effects of a Diet-Based Weight-Reducing Program with Probiotic Supplementation on Satiety Efficiency, Eating Behaviour Traits, and Psychosocial Behaviours in Obese Individuals. Nutrients 2017, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butki, B.D.; Baumstark, J.; Driver, S. Effects of a carbohydrate-restricted diet on affective responses to acute exercise among physically active participants. Percept. Mot. Skills 2003, 96, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M. Understanding and Treatment of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents. In Comprehensive Clinical Psychology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 453–494. ISBN 9780128222324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberska, H.; Boniecka, K. Health behaviours and body image of girls in the second phase of adolescence. Health Psychol. Rep. 2016, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paixão, C.; Dias, C.M.; Jorge, R.; Carraça, E.V.; Yannakoulia, M.; de Zwaan, M.; Soini, S.; Hill, J.O.; Teixeira, P.J.; Santos, I. Successful weight loss maintenance: A systematic review of weight control registries. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Bird, C. Sex stratification and health lifestyle: Consequences for Men’s and Women’s perceived health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1994, 35, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Torsheim, T.; Hetland, J.; Vollebergh, W.; Cavallo, F.; Jericek, H.; Alikasifoglu, M.; Välimaa, R.; Ottova, V.; Erhart, M.; et al. Subjective health, symptom load and quality of life of children and adolescents in Europe. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54 (Suppl. S2), 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A.F.; Korten, A.E.; Christensen, H.; Jacomb, P.A.; Rodgers, B.; Parslow, R.A. Association of obesity with anxiety, depression and emotional well-being: A community survey. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Public Health 2003, 27, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Behrens, S.C.; Favaro, A.; Tenconi, E.; Vindigni, V.; Teufel, M.; Skoda, E.-M.; Lindner, M.; Quiros-Ramirez, M.A.; Mohler, B.; et al. Body Image Disturbances and Weight Bias after Obesity Surgery: Semantic and Visual Evaluation in a Controlled Study, Findings from the BodyTalk Project. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.P. Snowball Sampling: Introduction. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, 1st ed.; Balakrishnan, N., Colton, T., Everitt, B., Piegorsch, W., Ruggeri, F., Teugels, J.L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łobocki, M. Metody i Techniki Badań Pedagogicznych; Oficyna Wydawnicza “Impuls”: Kraków, Polska, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Analyzed Variables | Measurement 1 N = 122 | Measurement 2 N = 122 | Difference | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| BMI | 29.94 | 3.72 | 22.35 | 1.90 | 7.60 | 23.77 | <0.001 |

| Mental state | 31.6 | 5.31 | 24.89 | 6.31 | −6.75 | −8.36 | <0.001 |

| Body assessment | |||||||

| Sexual attractiveness | 37.85 | 9.71 | 51.07 | 7.11 | −13.22 | −11.84 | <0.001 |

| Weight control | 24.56 | 8.96 | 38.74 | 6.78 | −14.18 | −13.44 | <0.001 |

| Physical condition | 24.82 | 7.40 | 36.63 | 4.98 | −11.81 | −14.37 | <0.001 |

| Analyzed Variables | Group 1 N = 62 | Group 2 N = 60 | t/z * | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Initial BMI | 30.41 | 4.02 | 29.49 | 3.37 | 1.33 * | 0.184 |

| Mental state | 25.45 | 7.01 | 25.48 | 5.77 | 0.17 * | 0.866 |

| Body assessment | ||||||

| Sexual attractiveness | 37.67 | 10.45 | 38.03 | 9.02 | 0.10 * | 0.922 |

| Weight control | 23.90 | 9.56 | 25.19 | 8.36 | −0.94 * | 0.344 |

| Physical condition | 23.80 | 7.86 | 25.81 | 6.85 | −1.49 * | 0.135 |

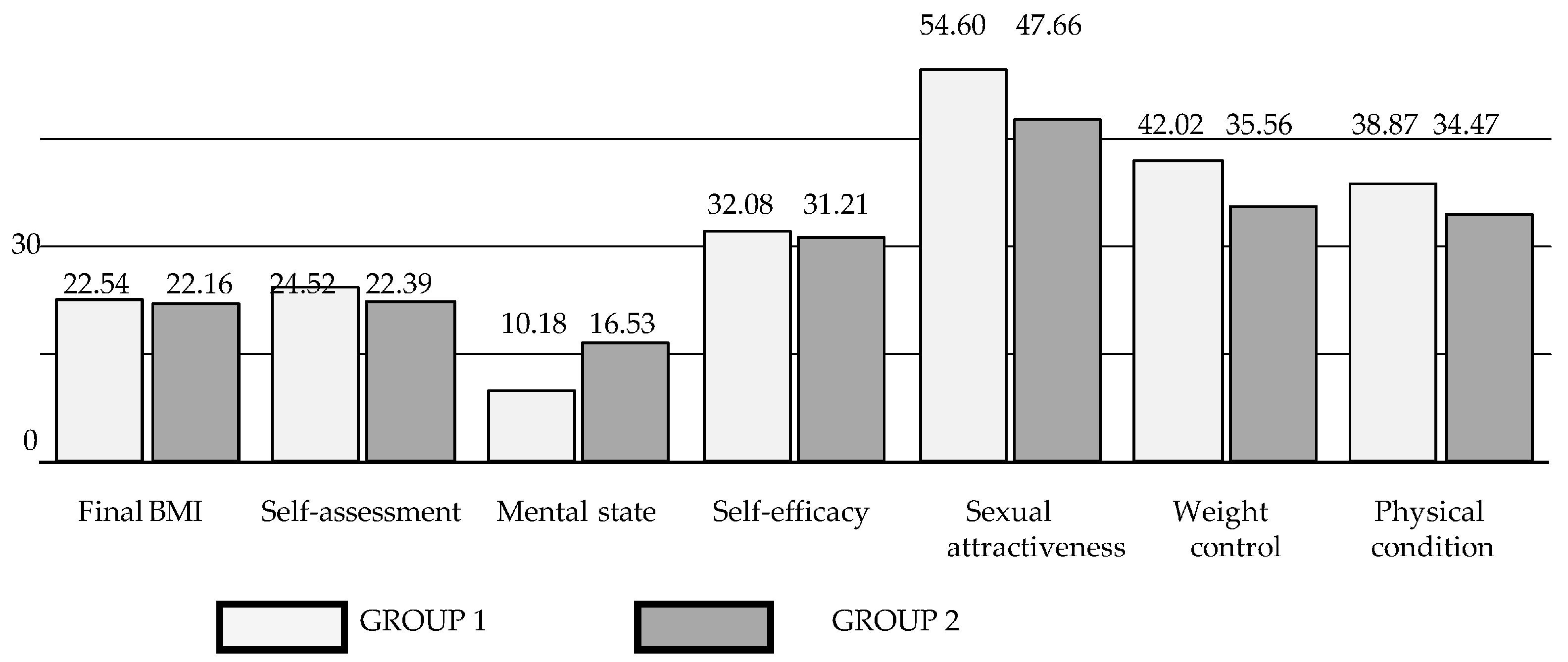

| Analyzed Variables | Group 1 N = 62 | Group 2 N = 60 | t/z * | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Final BMI | 22.54 | 1.88 | 22.16 | 1.91 | 1.08 * | 0.282 |

| Self-assessment | 24.52 | 4.72 | 22.39 | 3.80 | 2.38 * | 0.017 |

| Mental state | 10.18 | 8.45 | 16.53 | 9.46 | −3.77 * | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy | 32.08 | 4.87 | 31.21 | 5.71 | 0.62 | 0.533 |

| Body assessment | ||||||

| Sexual attractiveness | 54.60 | 5.87 | 47.66 | 6.55 | 6.15 | <0.001 |

| Weight control | 42.02 | 5.82 | 35.56 | 6.13 | 5.80 * | <0.001 |

| Physical condition | 38.87 | 3.97 | 34.47 | 4.92 | 5.10 * | <0.001 |

| Analyzed Variables | Body Assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Attractiveness | Weight Control | Physical Condition | |

| Level of mental health (first measurement) | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| Level of mental health (second measurement) | −0.37 | −0.42 | −0.47 |

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables Which Reached Statistical Significance in the Model | Corr. R2 | F | Beta | T | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of mental health (second measurement) | Weight control, Physical condition | 0.24 | 20.49 | −0.23 | −2.40 | 0.018 |

| −0.34 | −3.63 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liberska, H.; Boniecka, K. Mental Health and Body Image and the Reduction of Excess Body Weight in Woman (Polish Sample). Nutrients 2024, 16, 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16060811

Liberska H, Boniecka K. Mental Health and Body Image and the Reduction of Excess Body Weight in Woman (Polish Sample). Nutrients. 2024; 16(6):811. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16060811

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiberska, Hanna, and Klaudia Boniecka. 2024. "Mental Health and Body Image and the Reduction of Excess Body Weight in Woman (Polish Sample)" Nutrients 16, no. 6: 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16060811

APA StyleLiberska, H., & Boniecka, K. (2024). Mental Health and Body Image and the Reduction of Excess Body Weight in Woman (Polish Sample). Nutrients, 16(6), 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16060811