Caralluma fimbriata Extract Improves Vascular Dysfunction in Obese Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Animals and Ethical Approval

2.3. Diet Protocol and Jelly Treatment

2.4. Body Weight and EchoMRI

2.5. Humane Dispatch and Isometric Tension Analysis

2.6. Immunohistochemistry Technique and Semi-Quantitative Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

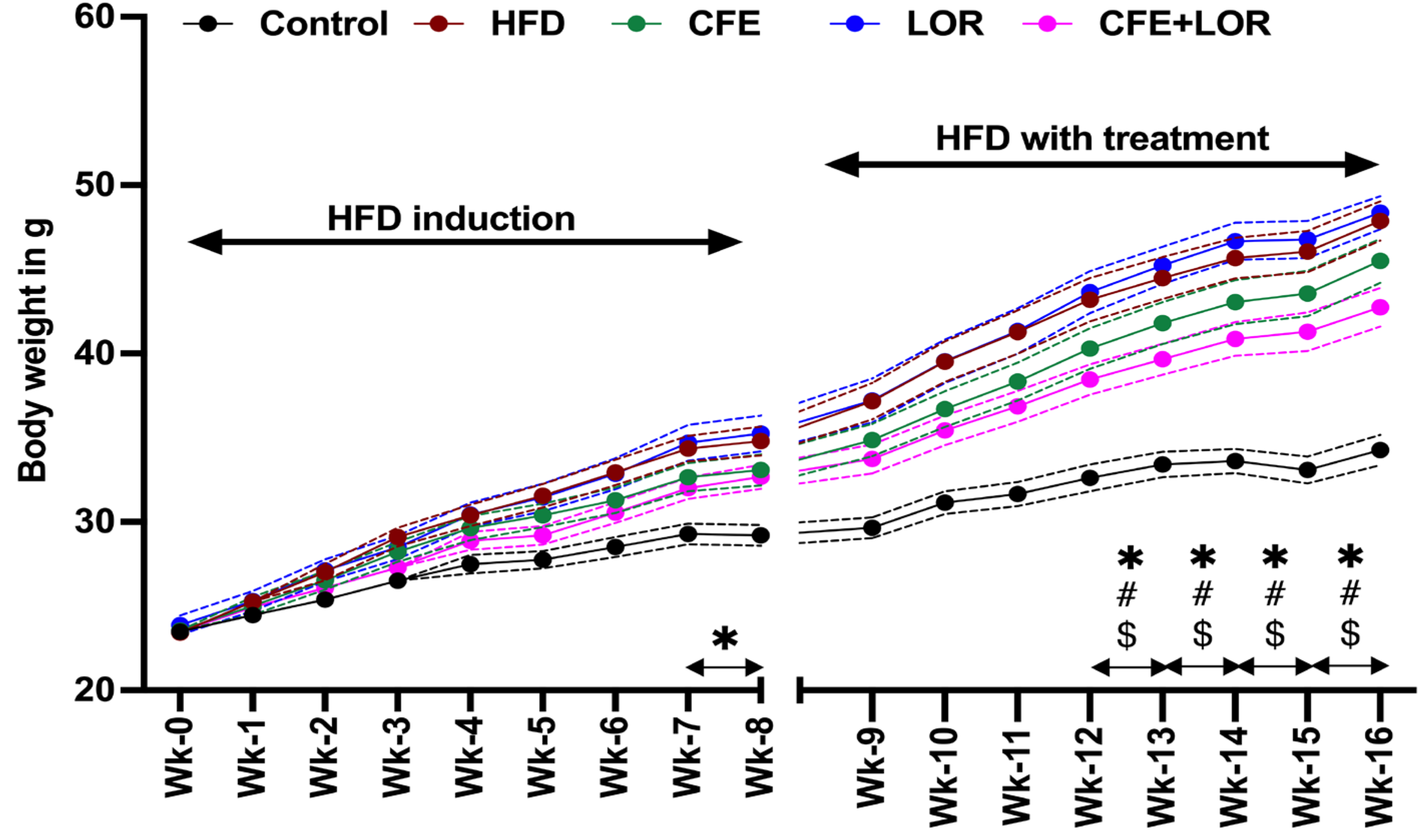

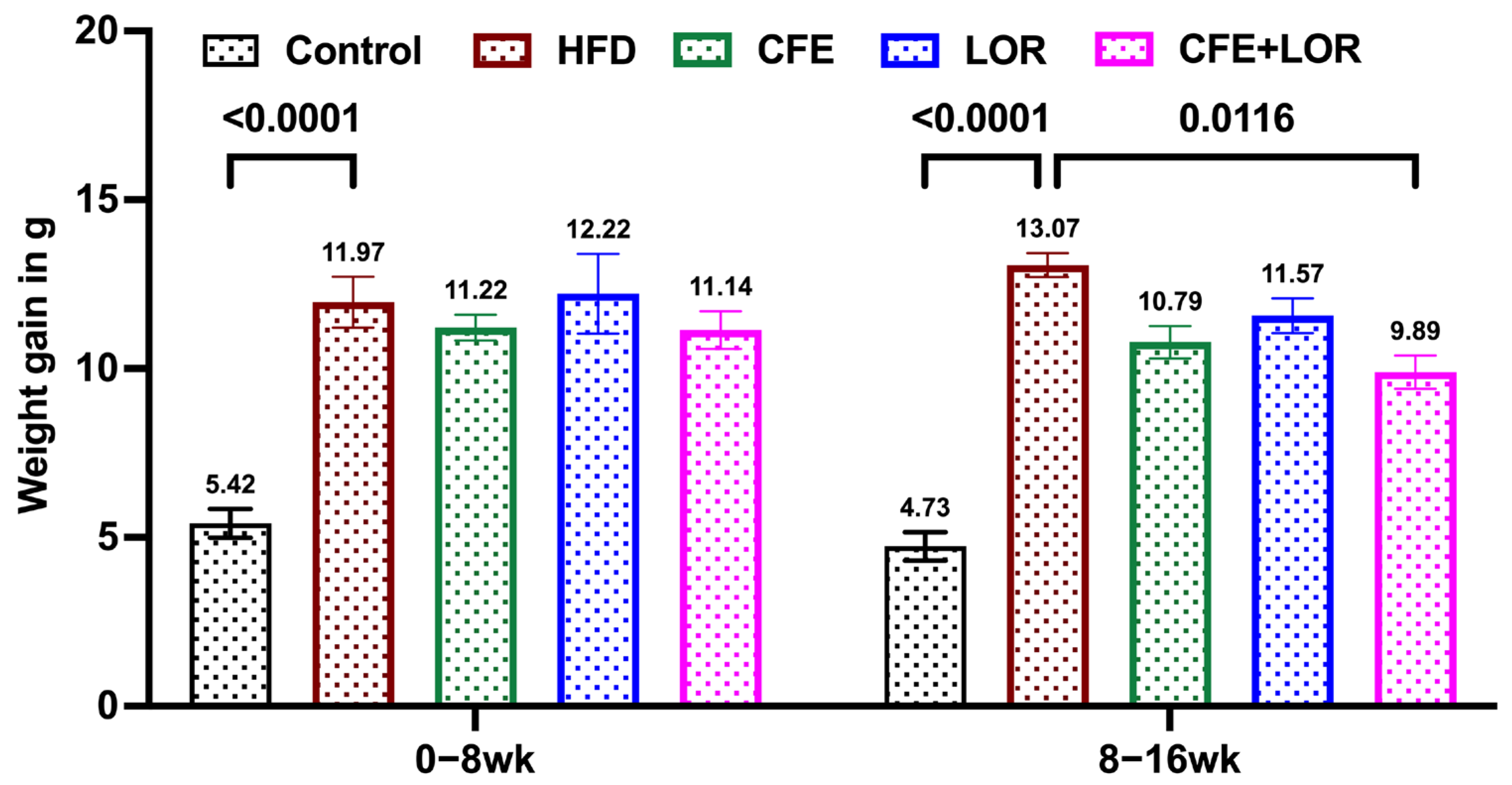

3.1. CFE Reduces Weight Gain in Mice Fed a HFD

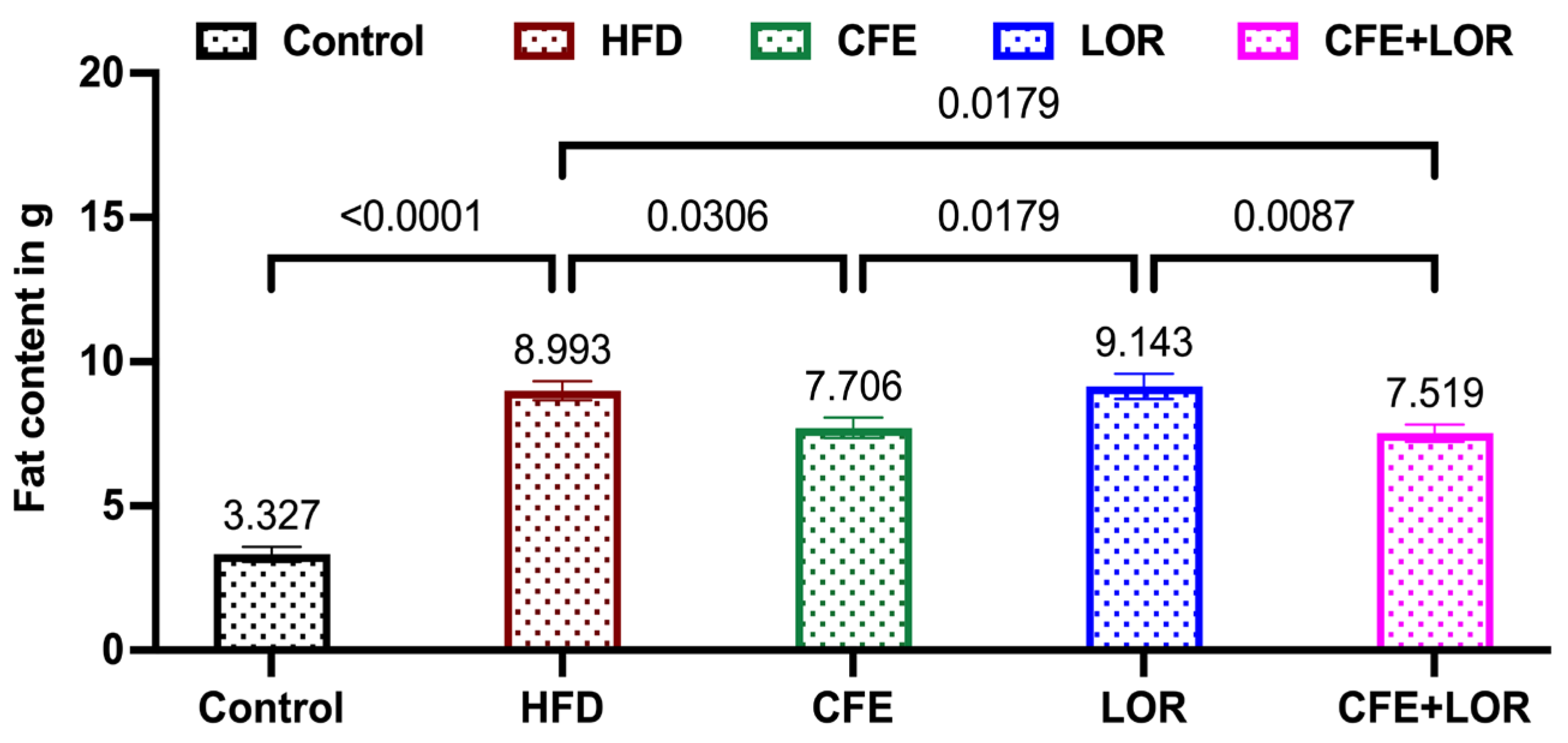

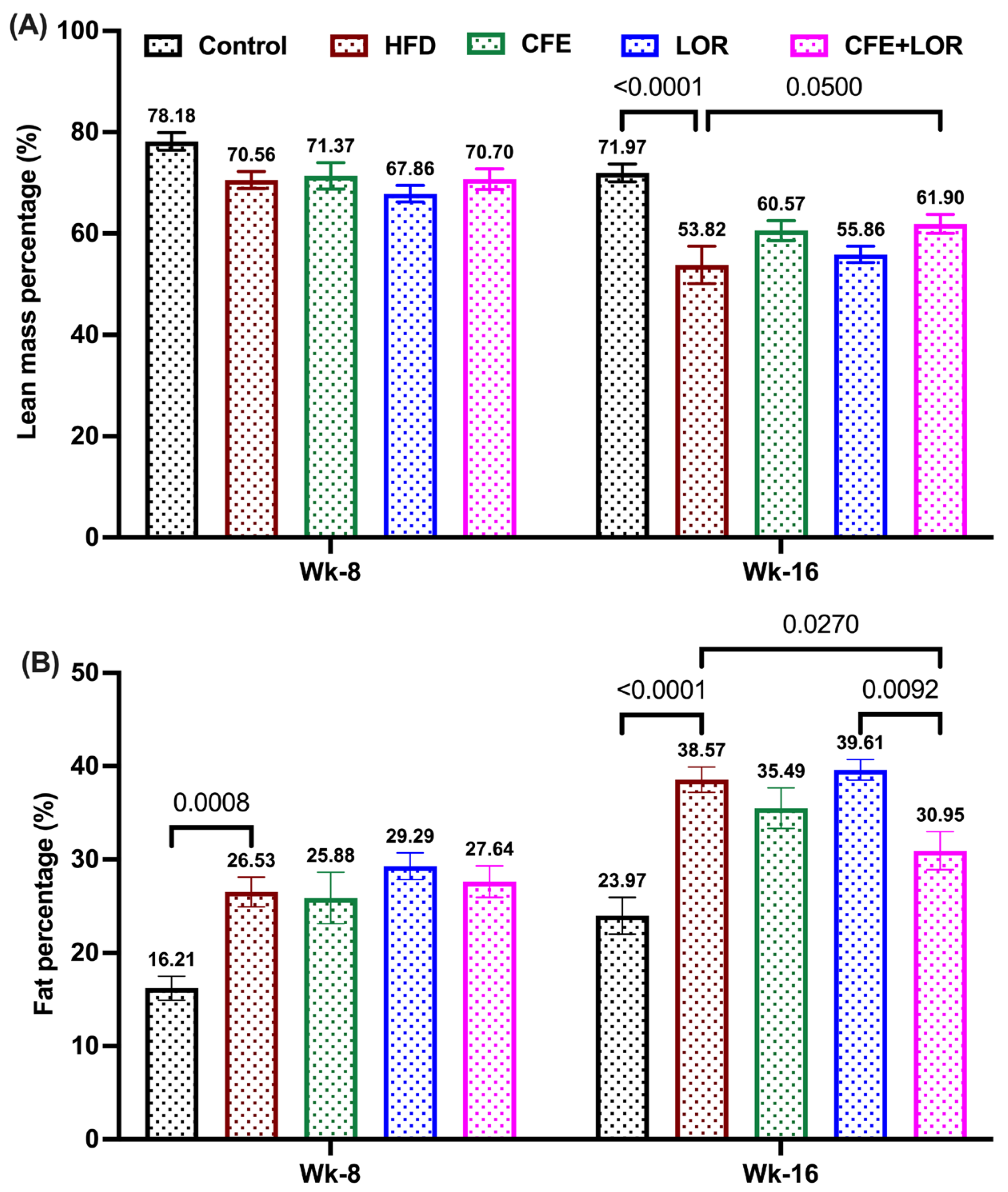

3.2. CFE Reduces Fat Mass

3.3. A HFD Reduces Relaxation to ACh and Is Imrpoved by CFE

3.4. HFD-Induced Obesity Reduces eNOS and Increases GRP78 and NT Expression in Abdominal Aorta: Improvements Achieved with CFE Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhattacharya, P.; Kanagasooriyan, R.; Subramanian, M. Tackling inflammation in atherosclerosis: Are we there yet and what lies beyond? Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022, 66, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, e153–e639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Sadykhov, N.K.; Kartuesov, A.G.; Borisov, E.E.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Hypertension as a risk factor for atherosclerosis: Cardiovascular risk assessment. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 959285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, R.J. Obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory disease contribute to atherosclerosis: A review of the pathophysiology and treatment of obesity. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 11, 504. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, M.S.; Freiberg, M.S.; Greevy, R.A.; Kundu, S.; Vasan, R.S.; Tindle, H.A. Association of smoking cessation with subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2019, 322, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. The current status of homocysteine as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A mini review. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2018, 16, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, H.; Platat, C.; Ali, H.I.; Ismail, L.C.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Bosevski, M.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Stojanovska, L. The benefits of physical activity in middle-aged individuals for cardiovascular disease outcomes. Maturitas 2023, 168, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosevski, M.; Stojanovska, L.; Apostolopoulos, V. Inflammatory biomarkers: Impact for diabetes and diabetic vascular disease. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2015, 47, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitevska, I.P.; Baneva, N.; Srbinovska, E.; Stojanovska, L.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Bosevski, M. Prognostic implications of myocardial perfusion imaging and coronary calcium score in a Macedonian cohort of asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2017, 14, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.A.; Mannarini, S.; Castelnuovo, G.; Pietrabissa, G. Disordered Eating Behaviors Related to Food Addiction/Eating Addiction in Inpatients with Obesity and the General Population: The Italian Version of the Addiction-like Eating Behaviors Scale (AEBS-IT). Nutrients 2023, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, A.; Gratteri, S.; Gualtieri, P.; Cammarano, A.; Bertucci, P.; Di Renzo, L. Why primary obesity is a disease? J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardestani, S.B.; Eftedal, I.; Pedersen, M.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Nørregaard, R.; Matchkov, V.V. Endothelial dysfunction in small arteries and early signs of atherosclerosis in ApoE knockout rats. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15296. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolopoulos, V.; De Courten, M.P.; Stojanovska, L.; Blatch, G.L.; Tangalakis, K.; De Courten, B. The complex immunological and inflammatory network of adipose tissue in obesity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgescu, A.; Popov, D.; Constantin, A.; Nemecz, M.; Alexandru, N.; Cochior, D.; Tudor, A. Dysfunction of human subcutaneous fat arterioles in obesity alone or obesity associated with Type 2 diabetes. Clin. Sci. 2011, 120, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, G.; Seravalle, G.; Scopelliti, F.; Dell’Oro, R.; Fattori, L.; Quarti-Trevano, F.; Brambilla, G.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Mancia, G. Structural and functional alterations of subcutaneous small resistance arteries in severe human obesity. Obesity 2010, 18, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Guilder, G.P.; Stauffer, B.L.; Greiner, J.J.; DeSouza, C.A. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in overweight and obese adult humans is not limited to muscarinic receptor agonists. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H1685–H1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Corral, A.; Sert-Kuniyoshi, F.H.; Sierra-Johnson, J.; Orban, M.; Gami, A.; Davison, D.; Singh, P.; Pusalavidyasagar, S.; Huyber, C.; Votruba, S. Modest visceral fat gain causes endothelial dysfunction in healthy humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Yang, Y.; Nong, A.; Tang, Z.; Li, Q.X. GRP78 activity moderation as a therapeutic treatment against obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawietz, H.; Brendel, H.; Diaba-Nuhoho, P.; Catar, R.; Perakakis, N.; Wolfrum, C.; Bornstein, S.R. Cross-talk of NADPH oxidases and inflammation in obesity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choromańska, B.; Myśliwiec, P.; Łuba, M.; Wojskowicz, P.; Myśliwiec, H.; Choromańska, K.; Dadan, J.; Zalewska, A.; Maciejczyk, M. The impact of hypertension and metabolic syndrome on nitrosative stress and glutathione metabolism in patients with morbid obesity. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1057570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Xu, S.; Huang, L.; Chen, C. Obesity and insulin resistance: Pathophysiology and treatment. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.-N.; Wu, T.-Y.; Chau, C.-F. Natural dietary and herbal products in anti-obesity treatment. Molecules 2016, 21, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, H.E. Lorcaserin and adiposopathy: 5-HT2c agonism as a treatment for ‘sick fat’and metabolic disease. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2009, 7, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade Mesquita, L.; Fagundes Piccoli, G.; Richter da Natividade, G.; Frison Spiazzi, B.; Colpani, V.; Gerchman, F. Is lorcaserin really associated with increased risk of cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell, K.J.; Mathai, M.L.; McAinch, A.J.; Stathis, C.G.; Su, X.Q. A pilot study investigating the effect of Caralluma fimbriata extract on the risk factors of metabolic syndrome in overweight and obese subjects: A randomised controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2013, 21, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyan, R.; Raj, T.; Srinivas, S.; Vaz, M.; Rajendran, R.; Kurpad, A.V. Effect of Caralluma fimbriata extract on appetite, food intake and anthropometry in adult Indian men and women. Appetite 2007, 48, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalakkannan, S.; Rajendran, R.; Venkatesh, R.V.; Clayton, P.; Akbarsha, M.A. Antiobesogenic and antiatherosclerotic properties of Caralluma fimbriata extract. J. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 2010, 285301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Briskey, D.; Dos Reis, C.; Mallard, A.R. The effect of an orally-dosed Caralluma Fimbriata extract on appetite control and body composition in overweight adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, J.L.; Mathai, M.L.; Sinnayah, P. Caralluma fimbriata extract activity involves the 5-HT2c receptor in PWS Snord116 deletion mouse model. Brain Behav. 2018, 8, e01102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, S.; Gruber, S.B.; Rabchevsky, A.G.; Emeson, R.B. The activity of the serotonin receptor 2C is regulated by alternative splicing. Hum. Genet. 2017, 136, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R.; Rajendran, K. Caralluma Extract Products and Processes for Making the Same. U.S. Patent No. 7390516B2, 24 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.M.; Kupchik, Y.M.; Spencer, S.; Garcia-Keller, C.; Spanswick, D.C.; Lawrence, A.J.; Simonds, S.E.; Schwartz, D.J.; Jordan, K.A.; Jhou, T.C. Addiction-like synaptic impairments in diet-induced obesity. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Purtell, L.; Fu, M.; Lee, N.J.; Aepler, J.; Zhang, L.; Loh, K.; Enriquez, R.F.; Baldock, P.A.; Zolotukhin, S. Snord116 is critical in the regulation of food intake and body weight. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18614. [Google Scholar]

- d’Agostino, G.; Lyons, D.; Cristiano, C.; Lettieri, M.; Olarte-Sanchez, C.; Burke, L.K.; Greenwald-Yarnell, M.; Cansell, C.; Doslikova, B.; Georgescu, T. Nucleus of the solitary tract serotonin 5-HT2C receptors modulate food intake. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 619–630.e615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Gomes, A.; Escobar, A.; Soares, J.S.; Silva, A.A.d.; Dessimoni-Pinto, N.A.V.; Riul, T.R. Chemical composition and hypocholesterolemic effect of milk kefir and water kefir in Wistar rats. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 31, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betik, A.C.; Aguila, J.; McConell, G.K.; McAinch, A.J.; Mathai, M.L. Tocotrienols and whey protein isolates substantially increase exercise endurance capacity in diet-induced obese male sprague-dawley rats. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152562. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, J.P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Novak, C.M.; Levine, J.A.; Billington, C.J.; Kotz, C.M. Evaluation of a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging system for whole body composition analysis in rodents. Obesity 2010, 18, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Gadanec, L.K.; McSweeney, K.R.; Kubatka, P.; Caprnda, M.; Gaspar, L.; Prosecky, R.; Dragasek, J.; Kruzliak, P.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Zulli, A. Angiotensin II constricts mouse iliac arteries: Possible mechanism for aortic aneurysms. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gadanec, L.K.; Andersson, U.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Zulli, A. Glycyrrhizic acid inhibits high-mobility group box-1 and homocysteine-induced vascular dysfunction. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, A.S.; Khavandi, K.; Withers, S.B.; Sonoyama, K.; Clancy, O.; Jeziorska, M.; Laing, I.; Yates, A.P.; Pemberton, P.W.; Malik, R.A. Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anticontractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients. Circulation 2009, 119, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjala, S.; Putakala, M.; Bongu, S.B.R.; Ramaswamy, R.; Desireddy, S. Preventive effect of Caralluma fimbriata against high-fat diet induced injury to heart by modulation of tissue lipids, oxidative stress and histological changes in Wistar rats. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 128, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenen, M.; Hill, M.A.; Cohen, P.; Sowers, J.R. Obesity, adipose tissue and vascular dysfunction. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vitalone, A.; Di Sotto, A.; Mammola, C.L.; Heyn, R.; Miglietta, S.; Mariani, P.; Sciubba, F.; Passarelli, F.; Nativio, P.; Mazzanti, G. Phytochemical analysis and effects on ingestive behaviour of a Caralluma fimbriata extract. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 108, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campia, U.; Tesauro, M.; Cardillo, C. Human obesity and endothelium-dependent responsiveness. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Correa, E.; González-Pérez, I.; Clavel-Pérez, P.I.; Contreras-Vargas, Y.; Carvajal, K. Biochemical and nutritional overview of diet-induced metabolic syndrome models in rats: What is the best choice? Nutr. Diabetes 2020, 10, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, E.A.; Rice, T.; Eikelis, N.; Straznicky, N.E.; Lambert, G.W.; Head, G.A.; Hensman, C.; Schlaich, M.P.; Dixon, J.B. Sympathetic activity and markers of cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic severely obese patients: The effect of the initial 10% weight loss. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Wu, Y.; Fried, S.K. Adipose tissue heterogeneity: Implication of depot differences in adipose tissue for obesity complications. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Handakas, E.; Lau, C.H.; Alfano, R.; Chatzi, V.L.; Plusquin, M.; Vineis, P.; Robinson, O. A systematic review of metabolomic studies of childhood obesity: State of the evidence for metabolic determinants and consequences. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Garcia-Barrio, M.T.; Chen, Y.E. Perivascular adipose tissue regulates vascular function by targeting vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1094–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-F.; Liu, H.-T.; Chen, P.-Y.; Lin, H.; Tseng, T.-L. Role of PVAT in obesity-related cardiovascular disease through the buffering activity of ATF3. iScience 2022, 25, 105631. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, P.; Fan, H.; Liu, Z.; He, J.-Q. Small mammalian animal models of heart disease. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brainard, R.E.; Watson, L.J.; DeMartino, A.M.; Brittian, K.R.; Readnower, R.D.; Boakye, A.A.; Zhang, D.; Hoetker, J.D.; Bhatnagar, A.; Baba, S.P. High fat feeding in mice is insufficient to induce cardiac dysfunction and does not exacerbate heart failure. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moura e Dias, M.; Dos Reis, S.A.; da Conceição, L.L.; Sediyama, C.M.N.d.O.; Pereira, S.S.; de Oliveira, L.L.; Gouveia Peluzio, M.d.C.; Martinez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I. Diet-induced obesity in animal models: Points to consider and influence on metabolic markers. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.; Hasselwander, S.; Li, H.; Xia, N. Effects of different diets used in diet-induced obesity models on insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction in C57BL/6 mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L. High fat diet induced obesity model using four strains of mice: Kunming, C57BL/6, BALB/c and ICR. Exp. Anim. 2020, 69, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.M.; Hilgers, R.H.; Das, K.C. Decreased EDHF-mediated relaxation is a major mechanism in endothelial dysfunction in resistance arteries in aged mice on prolonged high-fat sucrose diet. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.; Brettle, H.; Diep, H.; Dinh, Q.N.; O’Keeffe, M.; Fanson, K.V.; Sobey, C.G.; Lim, K.; Drummond, G.R.; Vinh, A. Sex-specific effects of a high fat diet on aortic inflammation and dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, M.R.; Hunt, T.C.; Pak, E.S.; Hannan, J.L. High-fat diet induces obesity in adult mice but fails to develop pre-penile and penile vascular dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2022, 34, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Tang, M. Exercise improves high fat diet-impaired vascular function. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 7, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Weisenburger, S.; Koch, E.; Burkart, M.; Reifenberg, G.; Förstermann, U.; Li, H. Restoration of perivascular adipose tissue function in diet-induced obese mice without changing bodyweight. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 3443–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Horke, S.; Habermeier, A.; Closs, E.I.; Reifenberg, G.; Gericke, A.; Mikhed, Y.; Münzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Förstermann, U. Uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in perivascular adipose tissue of diet-induced obese mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Huang, F.; Ni, M.; Zhao, X.B.; Deng, Y.P.; Yu, J.W.; Jiang, G.J.; Tao, X. Cognitive function is impaired by obesity and alleviated by lorcaserin treatment in mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2015, 21, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elangbam, C.S.; Lightfoot, R.M.; Yoon, L.W.; Creech, D.R.; Geske, R.S.; Crumbley, C.W.; Gates, L.D.; Wall, H.G. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5HT) receptors in the heart valves of cynomolgus monkeys and Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2005, 53, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikova, L.; Mesitov, M.; Moskovtsev, A. Agonists of 5HT2C-receptors SCH 23390 and MK 212 incresase the force of rat aorta contraction in the presence of vasopressin and angiotensin II. Patol. Fiziol. Eksp. Ter. 2014, 58, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, H.S.; Oliveira, E.; Faustino, T.N.; e Silva, E.d.C.; Fregoneze, J.B. Effect of the activation of central 5-HT2C receptors by the 5-HT2C agonist mCPP on blood pressure and heart rate in rats. Brain Res. 2005, 1040, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I.K.; Martin, G.R.; Ramage, A.G. Central administration of 5-HT activates 5-HT1A receptors to cause sympathoexcitation and 5-HT2/5-HT1C receptors to release vasopressin in anaesthetized rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992, 107, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, K.; Schmidt, E.E.; Sayin, V.I. Cellular redox homeostasis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Rubio-Ruíz, M.E.; Soto, M.E.; Guarner-Lans, V. Nitrosative stress and its association with cardiometabolic disorders. Molecules 2020, 25, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, F.; Pang, J.; Pan, C.; Xu, F.; Chen, Y. Fundamental mechanisms of the cell death caused by nitrosative stress. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 742483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serano, M.; Paolini, C.; Michelucci, A.; Pietrangelo, L.; Guarnier, F.A.; Protasi, F. High-fat diet impairs muscle function and increases the risk of environmental heatstroke in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrosova, I.G.; Ilnytska, O.; Lyzogubov, V.V.; Pavlov, I.A.; Mashtalir, N.; Nadler, J.L.; Drel, V.R. High-fat diet–induced neuropathy of pre-diabetes and obesity: Effects of “healthy” diet and aldose reductase inhibition. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wicks, S.E.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Breaux, C.; Kruger, C.; Stadler, K. Diet-induced obesity and kidney disease–in search of a susceptible mouse model. Biochimie 2016, 124, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Torres, C.M.; Ortiz-Reyes, A.E.; Murguía-Romero, M. Oxidative damage by 3-nitrotyrosine in young adults with obesity: Its implication in chronic and contagious diseases. Curr. Mol. Med. 2023, 23, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, V.H.; Smith, J.; McLea, S.A.; Heizer, A.B.; Richardson, J.L.; Myatt, L. Effect of increasing maternal body mass index on oxidative and nitrative stress in the human placenta. Placenta 2009, 30, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakara, G.; Mallaiah, P.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Sasi Bhusana Rao, B.; Rajendran, R.; Saralakumari, D. Beneficial effects of hydro-alcoholic extract of Caralluma fimbriata against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and oxidative stress in Wistar male rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 70, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Gujjala, S.; Putakala, M.; Nukala, S.; Bangeppagari, M.; Ramaswamy, R.; Desireddy, S. Renoprotective effect of Caralluma fimbriata against high-fat diet-induced oxidative stress in Wistar rats. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 586–593. [Google Scholar]

- Gujjala, S.; Putakala, M.; Gangarapu, V.; Nukala, S.; Bellamkonda, R.; Ramaswamy, R.; Desireddy, S. Protective effect of Caralluma fimbriata against high-fat diet induced testicular oxidative stress in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakara, G.; Mallaiah, P.; Rajendran, R.; Saralakumari, D. Caralluma fimbriata and metformin protection of rat pancreas from high fat diet induced oxidative stress. Biotech. Histochem. 2018, 93, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Cuevas, J.; López-Cifuentes, D.; Sandoval-Rodriguez, A.; García-Bañuelos, J.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. Medicinal Plant Extracts against Cardiometabolic Risk Factors Associated with Obesity: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciumărnean, L.; Milaciu, M.V.; Runcan, O.; Vesa, Ș.C.; Răchișan, A.L.; Negrean, V.; Perné, M.-G.; Donca, V.I.; Alexescu, T.-G.; Para, I. The effects of flavonoids in cardiovascular diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, H.M.; Abd-Alla, H.I.; Mahmoud, K.H.; El-Toumy, S.A. In vitro anti-nitrosative, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of plant flavonoids: A comparative study. Med. Chem. Res. 2014, 23, 3298–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, H.C.R.; Cruz, Y.M.C.; Bertolino, J.S.; Garcia, R.C.T.; Fernandes, L. Protective effects of luteolin on the venous endothelium. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Wyeth, R.P.; Liu, D. The flavonoid luteolin induces nitric oxide production and arterial relaxation. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, C.; Fondevila, M.F.; López, M. Hypothalamic GRP78, a new target against obesity? Adipocyte 2018, 7, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbank, E.; Martinez, M.C.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Extracellular vesicles: Pharmacological modulators of the peripheral and central signals governing obesity. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 157, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marycz, K.; Kornicka, K.; Szlapka-Kosarzewska, J.; Weiss, C. Excessive endoplasmic reticulum stress correlates with impaired mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy and apoptosis, in liver and adipose tissue, but not in muscles in EMS horses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Tabiatnejad, P.; Young, C.N. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in a circumventricular organ-hypothalamic neuronal circuit alters hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism during obesity. Physiology 2024, 39, 460. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, K.; Li, H.-P.; Wang, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.-M.; Zhang, X.; Xing, B.-W. GRP78 protein metabolism in obese and diabetic rats: A study of its role in metabolic disorders. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, C.Y. Allium macrostemon whole extract ameliorates obesity-induced inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in adipose tissue of high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6N mice. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girona, J.; Rodríguez-Borjabad, C.; Ibarretxe, D.; Vallvé, J.-C.; Ferré, R.; Heras, M.; Rodríguez-Calvo, R.; Guaita-Esteruelas, S.; Martínez-Micaelo, N.; Plana, N. The circulating GRP78/BiP is a marker of metabolic diseases and atherosclerosis: Bringing endoplasmic reticulum stress into the clinical scenario. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suganya, N.; Bhakkiyalakshmi, E.; Suriyanarayanan, S.; Paulmurugan, R.; Ramkumar, K. Quercetin ameliorates tunicamycin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in endothelial cells. Cell Prolif. 2014, 47, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Bao, L.; Dai, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Quercetin protects RAW264. 7 macrophages from glucosamine-induced apoptosis and lipid accumulation via the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 7545–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, Y.S.; Mustafa, M.R.; Choy, K.W.; Chan, S.M.; Potocnik, S.; Herbert, T.P.; Woodman, O.L. 3′,4′-dihydroxyflavonol ameliorates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and endothelial dysfunction in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | Animal Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | HFD | HFD + CFE | HFD + LOR | HFD + CFE + LOR | |

| Gelatine (%) | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Saccharine (mg/mL) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CFE (mg/kg bwt) | - | - | 100 | - | 100 |

| LOR (mg/kg bwt) | - | - | - | 5 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thunuguntla, V.B.S.C.; Gadanec, L.K.; McGrath, C.; Griggs, J.L.; Sinnayah, P.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Zulli, A.; Mathai, M.L. Caralluma fimbriata Extract Improves Vascular Dysfunction in Obese Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244296

Thunuguntla VBSC, Gadanec LK, McGrath C, Griggs JL, Sinnayah P, Apostolopoulos V, Zulli A, Mathai ML. Caralluma fimbriata Extract Improves Vascular Dysfunction in Obese Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients. 2024; 16(24):4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244296

Chicago/Turabian StyleThunuguntla, Venkata Bala Sai Chaitanya, Laura Kate Gadanec, Catherine McGrath, Joanne Louise Griggs, Puspha Sinnayah, Vasso Apostolopoulos, Anthony Zulli, and Michael L. Mathai. 2024. "Caralluma fimbriata Extract Improves Vascular Dysfunction in Obese Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet" Nutrients 16, no. 24: 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244296

APA StyleThunuguntla, V. B. S. C., Gadanec, L. K., McGrath, C., Griggs, J. L., Sinnayah, P., Apostolopoulos, V., Zulli, A., & Mathai, M. L. (2024). Caralluma fimbriata Extract Improves Vascular Dysfunction in Obese Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients, 16(24), 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244296