Abstract

Selenium (Se) is an essential trace element for humans and its low or high concentration in vivo is associated with the high risk of many diseases. It is important to identify influential factors of Se status. The present study aimed to explore the association between several factors (Se intake, gender, age, race, education, body mass index (BMI), income, smoking and alcohol status) and blood Se concentration using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2020 data. Demographic characteristics, physical examination, health interviews and diets were compared among quartiles of blood Se concentration using the Rao-Scott χ2 test. Se levels were compared between the different groups of factors studied, measuring the strength of their association. A total of 6205 participants were finally included. The normal reference ranges of blood Se concentration were 142.3 (2.5th percentile) and 240.8 μg/L (97.5th percentile), respectively. The mean values of dietary Se intake, total Se intake and blood Se concentration of the participants were 111.5 μg/day, 122.7 μg/day and 188.7 μg/L, respectively, indicating they were in the normal range. Total Se intake was the most important contributor of blood Se concentration. Gender, race, education status, income, BMI, smoking and alcohol status were associated with blood Se concentration.

1. Introduction

Selenium (Se) as a crucial trace mineral for humans exerts substantial biological functions, such as the endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis, immune response, regulation of transcription factors and apoptosis, control of the cellular redox state and development of the central nervous system through selenoproteins []. Humans obtain Se mainly through foods and supplements, whereby the Se contents depend on the varied soil Se contents. Approximately 80% of the population in the world are deficient in Se (less than 55 μg/day) due to insufficient Se consumption [].

Unfortunately, owing to a narrow safe range of Se, low or high Se status is found to be associated with the increased high risk of many diseases. Low Se levels increase the risk of Keshan disease, cretinism, immune dysfunction and cognitive impairment, whereas high Se levels elevate the occurrence of cancer, type 2 diabetes mellitus, neurological diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and endocrine diseases []. In addition, excessive Se intake or selenosis leads to some acute reactions, including garlic odor and metallic taste in mouth, hair or nail loss, nausea, diarrhea, skin rashes and irritability []. Because blood Se concentration is recognized as the reflection of Se intake [], it is important to identify influential factors of Se status for the maintenance of a safe blood Se range to decrease those risks.

To our knowledge, there are few studies to simultaneously evaluate the effects of several factors (Se intake, gender, age, race, education, body mass index (BMI), income, smoking and alcohol status) on blood Se. Based on the controllability and practical significance of most of these factors, i.e., some factors are influenced by self-development and lifestyles of participants, we hypothesize that blood Se levels in the US adult population are normal and that there is an association between blood Se and diet, gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, BMI and lifestyle. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore the association between those factors and blood Se concentration among American adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The national cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) used a complex multistage sampling method to obtain representative samples with a combination of interviews and examinations for the assessment of the health and nutritional status of children and adults in the USA. All the participants provided informed consent. Initially, questionnaires including demographic, health-related history and cigarette use were carried out among the participants aged 18 years or older via household interview by trained interviewers. After the at-home interview, the participants meeting all the inclusion criteria were invited to continue participation in the survey by coming to a mobile examination center (MEC) two to four weeks later. At the MEC, the first dietary recall interview was collected in-person followed by the alcohol data collection, and the second interview was collected by telephone 3 to 10 days later. During the MEC, body measure data and blood samples were collected for further testing.

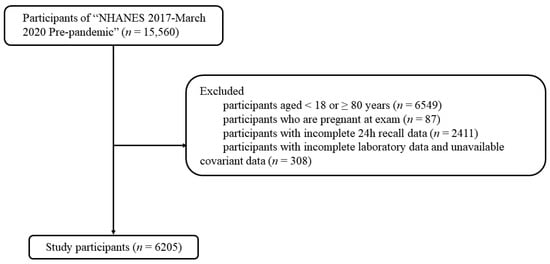

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suspended field operations due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, resulting in an incomplete cycle for the NHANES 2019–2020; therefore, the data of the NHANES 2019–2020 must be combined with NHANES 2017–2018 for analysis. The present study was based on the NHANES 2017–March 2020 with a total of 15,560 individuals, and following exclusion criteria as shown in Figure 1, 6205 participants were finally included. The NHANES was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its ethics was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the NCHS. Due to the present study being based on the secondary analysis, it did not need additional ethics approval.

Figure 1.

The selection process of study participants.

Gender, age and race were self-reported demographic information. Among these, race was categorized into Mexican American, other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black and other race. Education was defined by the question “What is the highest grade or level of school completed or the highest degree received?” and categorized into three levels: <high school, high school and >high school. The ratio of family income to poverty (PIR, <1.3 (low), 1.3–4.0 (medium), >4.0 (high)) [] was a measure of household income and calculated by dividing total annual family (or individual) income by the poverty guidelines specific to the survey year. The lower PIR, the poorer participants []. The BMI data were calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and classified <18.5 (underweight), 18.5–25.0 (normal weight), 25.0–30.0 (overweight), ≥30.0 (obese). Smoking status was assessed via the question “Do you now smoke cigarettes?” and grouped as every day, somedays and never. Alcohol information was based on the self-report of the participants to the question “Ever have 4/5 or more drinks every day?” (yes/no).

2.2. Dietary and Supplemental Se Intakes, and Blood Se Concentration

Dietary data were acquired via two 24 h recalls. Total Se intake consisted of dietary and supplemental Se intakes obtained by averaging two respective 24 h recall data. Inadequate and excessive Se intakes were defined as less than the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of 55 μg Se/day and more than the tolerable upper intake level of 400 μg Se/day for adults, respectively []. Blood Se concentration was detected by triple quadrupole inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. According to the previous study [], the normal ranges of blood Se concentration were defined as the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles for the overall US population. More experimental method details were described in the NHANES web at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm (accessed on 1 November 2021).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Blood Se concentration was divided into quartiles based on the weighted population distribution. Demographic characteristics, physical examination, health interviews and diets were compared among quartiles of blood Se concentration using the Rao-Scott χ2 test. The LSD (least significant difference) test was used to compare the differences in Se intake and Se level between different groups of factors. Weighted linear regression was conducted to evaluate the association between several factors (Se intake, gender, age, race, education, BMI, PIR, smoking and alcohol status) and blood Se concentration. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted by SAS 9.4 version (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics for Blood Se Concentration

Table 1 shows characteristics of the population categorized by quartiles of blood Se concentration. The percentage values of males and females were 48.7% and 51.3%, respectively. The age of the participants varied from 18 to 79 years old. More than half the participants had a degree of more than high school level. Additionally, the percentage values of the participants with hypertension, diabetes and stroke history were 31.0%, 11.0% and 3.5%, respectively. The weighted mean values of dietary Se intake, total Se intake and blood Se concentration of participants were 111.5 μg/day, 122.7 μg/day and 188.7 μg/L, respectively. The numbers of the participants with inadequate and excessive Se intakes were 602 and 17, respectively. The normal reference ranges of blood Se concentration were 142.3 (2.5th percentile) and 240.8 μg/L (97.5th percentile), respectively. There were 155 (only 2%) persons with blood Se deficiency and 155 (also only 2%) participants with Se toxicity. The percentage of participants taking Se supplements was 18.7% (1162 participants). For gender, race and education, statistically significant differences were observed among quartiles of blood Se concentration. There was no significant difference for age, BMI, PIR, smoking status, alcohol status, dietary Se intake, total Se intake, hypertension history, diabetes history and stroke history between quartiles of blood Se concentration.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics categorized by blood Se concentration in the NHANES 2017–2020.

3.2. Comparison of Se Intake and Se Level between Different Groups of Factors

Table 2 shows the Se intake and Se level between different groups of factors. Males had higher Se intake and blood Se than females. The participants aged 40–59 years had higher Se intake, but no difference in blood concentration was found among the three age groups. As for race, Mexican American, Non-Hispanic Whites and other races had greater Se intakes than Non-Hispanic Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites, and Non-Hispanic Blacks had lower Se levels compared to other races. Additionally, Non-Hispanic Whites had higher Se levels than Non-Hispanic Blacks. The participants with more than high school level education possessed higher Se intake and blood Se concentration than those with less than high school and equal to high school education. Blood Se level was higher in overweight participants than in underweight, normal and obese participants. The participants with the highest income possessed the highest Se intake and those with the lowest income presented with the lowest blood Se concentration. Smokers showed lower blood Se. Alcohol users had higher Se intakes but lower blood Se concentrations.

Table 2.

Comparison of Se intake and Se level between different groups of factors in the NHANES 2017–2020.

3.3. Association between Factors and Blood Se Concentration

The association between all the factors and blood Se concentration is presented in Table 2. Total Se intake was the most important determinant of blood Se concentration (Table 3). Males tended to have higher blood Se concentration than females. The participants with greater educational levels appeared to have higher blood Se concentrations. The Non-Hispanic Blacks had lower blood Se concentration. Smokers had lower blood Se concentrations than nonsmokers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Weighted linear regression analyses of the association between several factors (Se intake, gender, age, race, education, BMI, income, smoking and alcohol status) and blood Se concentration in the NHANES 2017–2020.

4. Discussion

In this study, the NHANES 2017–2020 data were used to explore several factors affecting blood Se level. Males aged 40–59 years, some races (Mexican American, Non-Hispanic White and other race) and highest educated population had higher Se consumption. Overweight participants, highest educated Non-Hispanic White and Non-Hispanic Black had higher blood Se levels. Smokers and alcohol users showed lower Se levels.

The average total Se intake and blood Se concentration were 122.7 μg/day and 188.7 μg/L, respectively, which were lower than those (174 μg/day and 253 μg/L) in the American seleniferous areas []. However, Se intake and blood Se concentration in this study were higher than those reported in other countries worldwide [,], with Se intake of approximately 95% of the participants above 55 μg/day, suggesting sufficient soil Se content in the USA. The Se-rich foods include Brazil nuts, crab meat, shrimp, allium vegetables, brown rice, whole wheat bread and skimmed milk. Se intake and blood Se vary globally. In Finland, Se fertilization increased average dietary intake from 40.0 μg Se/day to 80.0 μg Se/day []. In the low Se area of China, mean daily Se intake was 8.8 μg/day, resulting in the very low serum Se (24 μg/L) in that population []. In the present study, only 17 participants (only 0.3%) had excessive Se intake (>400 μg/day), nevertheless, considering that excessive Se intake led to acute side effects and chronic Se exposure increased the risks of nervous system abnormalities, it was very vital to maintain a safe Se intake range to reduce Se toxicity.

In the present study, there was a significantly positive association between dietary Se/total Se intakes and blood Se concentration, especially, total Se was the most important contributor for blood Se. Similarly, a previous study conducted in the American seleniferous area also found a strong correlation between Se intake and blood Se concentration []. A dose-response analysis found a non-linear relationship between Se intake and plasma Se concentration, and the predicted coefficients below and above such a cut-off of 70.0 μg/day were 1.25 and 0.43, respectively []. The aforementioned different results might be attributed to the sample size and source, Se species in foods and supplements consumed by the participants (organic Se mainly in foods and inorganic Se mainly in supplements), Se bioavailability (organic Se > inorganic Se) and analysis methods []. Additionally, some metals such as lead and mercury could interact with Se [,,]; unfortunately, the intake information for those metals were not available in the NHANES.

In the present study, males had higher blood Se than females, which was consistent with the results of previous studies [,,], partly due to the apparent sexual dimorphism related to sex hormones []. The trans-selenation pathway was regulated by sex hormones, suggesting selenomethionine metabolism and selenocysteine formation and the availability for selenoprotein synthesis are not the same in both sexes []. Given the sex difference in Se intake and blood Se concentration, establishing gender-based Se reference intakes should be considered in future Se RDA revisions [].

In our study, age was not significantly associated with blood Se concentration, which coincided with the findings of other studies in the USA [,]. There was no significant difference in blood Se concentration among the three age groups (18–39, 40–59, 60–79), although the participants aged 40–59 years had higher Se intake than those aged 60–79. However, the results of some previous studies were inconsistent, i.e., decreased blood Se [] with age and increased serum Se [] with age, partly because of changed absorption and excretion efficiency. Elevated Se concentration was demonstrated to improve cognitive functions [,], which was beneficial to the amelioration of cognitive decline in the elderly.

In the USA, the mean blood Se concentration was higher in white subjects compared to black subjects, which might be attributed to different geographical areas with varied soil Se content, differences in food choices and genetic differences in Se pharmacokinetics []. The participants with the education status of more than high school possessed prominently higher blood Se concentration, which was in line with the findings of the NHANES 2011–2014 [,], possibly because they cared more about dietary quality and had access to Se-enriched foods to enhance Se intake. The participants with low income had lower blood Se concentration than those with high income, which was similar to the previous report []. Interestingly, in our study, Se intake was higher in the high-income participants than those low-income participants. Moreover, participants with underweight were found to have a lower blood Se level than overweight participants, partly due to their lesser Se intake. Our study showed higher blood Se concentration in overweight participants compared to that in obese participants, and the previous result found reduced serum Se level in obese female patients []. There was an inverse association between smoking and blood Se. Smokers, especially those smoking every day, had significantly lower Se intake than non-smokers, which was in agreement with previous findings in the USA []. Notably, drinkers with more Se intake showed lower blood Se concentration compared to non-drinkers with less Se intake, which was caused by changes in hepatic structure and function induced by alcohol []

The strengths of the present study included a large representative sample for the reduction in sampling error, high-quality NHANES datasets and the weighted liner regression because of a complex survey design. The results could direct health-related policy decisions in the field of health and disease in the future.

However, there were several limitations in the present study. Firstly, owing to NHANES data based on a cross-sectional study, dietary Se data were self-reported with two 24 h recalls with inevitable recall bias and it only reflected short-term Se intake not long-term Se intake status. Therefore, a longitudinal study might be reasonable. Additionally, dietary data plus occupational exposure data more truly evaluated Se level in the human body. Secondly, Se species in foods and supplements were not available in the NHANES 2017–2020. Thirdly, alcohol information in the present study was not an optimal reflection of alcohol consumption levels of the participants.

5. Conclusions

The present results showed that the majority of US adults were in the safe range of blood Se concentrations and few participants were at risk of selenosis. Taken together, Se intake was the most primary determinant of blood Se. Gender, race, education status, income, BMI, smoking and alcohol status were associated with blood Se concentration. Considering the effects of Se status on certain chronic diseases shown in epidemiological studies, this study can provide baseline information for future health-related research and revision of guidance values.

Author Contributions

Original draft preparation; generation, collection, assembly, analysis and interpretation of data, Y.-Z.B.; data analysis and review, Y.-X.G.; conceptualization, supervision, review and editing, S.-Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The NHANES was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the National Centre for Health Statistics. Due to the present study based on the secondary analysis, additional ethics approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in the present study are available on the website of NHANES datasets 2017–2020 (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm (accessed in 2022)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, Y.Z.; Zhang, S.Q. Do selenium-enriched foods provide cognitive benefit? Metab. Brain Dis. 2023, 38, 1501–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Song, Z.; Kong, F.; Zhang, X. Selenium in Wheat from Farming to Food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 15458–15467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.Z.; Zhang, S.Q. Evidence-based proposal for lowering Chinese tolerable upper intake level for selenium. Nutr. Res. 2024, 123, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.B.; Choi, Y.S. Normal reference ranges for and variability in the levels of blood manganese and selenium by gender, age, and race/ethnicity for general U.S. population. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2015, 30, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Shen, S.; Zhang, Y. Comparison of Bioavailability, Pharmacokinetics, and Biotransformation of Selenium-Enriched Yeast and Sodium Selenite in Rats Using Plasma Selenium and Selenomethionine. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 196, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Liu, K.; Sun, X.; Qin, S.; Wu, M.; Qin, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhong, X.; Wei, X. A cross-sectional study of blood selenium concentration and cognitive function in elderly Americans: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2020, 47, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids; Institute of Medicine, The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, C.A.; Longnecker, M.P.; Veillon, C.; Howe, M.; Levander, O.A.; Taylor, P.R.; McAdam, P.A.; Brown, C.C.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C. Selenium intake, age, gender, and smoking in relation to indices of selenium status of adults residing in a seleniferous area. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 52, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.M.; Wei, H.J.; Yang, C.L.; Xing, J.; Qiao, C.H.; Feng, Y.M.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.X.; et al. Selenium intake and metabolic balance of 10 men from a low selenium area of China. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 42, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfthan, G.; Eurola, M.; Ekholm, P.; Venäläinen, E.R.; Root, T.; Korkalainen, K.; Hartikainen, H.; Salminen, P.; Hietaniemi, V.; Aspila, P.; et al. Effects of nationwide addition of selenium to fertilizers on foods, and animal and human health in Finland: From deficiency to optimal selenium status of the population. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2015, 31, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Peláez, C.; et al. Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level for selenium. Efsa J. 2023, 21, e07704. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Bai, Y.Z. Strategies for enhancing beneficial effects of selenium on cognitive function. Metab. Brain Dis. 2023, 38, 1857–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderi, M.; Puar, P.; Zonouzi-Marand, M.; Chivers, D.P.; Niyogi, S.; Kwong, R.W.M. A comprehensive review on the neuropathophysiology of selenium. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 144329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.J.; Duguay, A. Selenium-mercury interactions and relationship to aquatic toxicity: A review. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, L.; Xia, D.; Ying, J. Selenium protects against Pb-induced renal oxidative injury in weaning rats and human renal tubular epithelial cells through activating NRF2. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 83, 127420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Yan, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, H.; Li, H. Association between low blood selenium concentrations and poor hand grip strength in United States adults participating in NHANES (2011–2014). Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 48, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.F.; Chan, H.M. Factors associated with the blood and urinary selenium concentrations in the Canadian population: Results of the Canadian Health Measures Survey (2007–2011). Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, L.A.; Ogawa-Wong, A.N.; Berry, M.J. Sexual dimorphism in selenium metabolism and selenoproteins. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2018, 127, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, P.A.; Smith, D.K.; Feldman, E.B.; Hames, C. Effect of age, sex, and race on selenium status of healthy residents of Augusta, Georgia. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1984, 6, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.C.; Tomlinson, R.H. Selenium in blood and human tissues. Clin. Chim. Acta 1967, 16, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Banares, F.; Dolz, C.; Mingorance, M.D.; Cabré, E.; Lachica, M.; Abad-Lacruz, A.; Gil, A.; Esteve, M.; Giné, J.J.; Gassull, M.A. Low serum selenium concentration in a healthy population resident in Catalunya: A preliminary report. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 44, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.Q. Selenium and cognitive function. Metab. Brain Dis. 2023, 38, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, S.; Baral, B.K.; Feng, D.; Sy, F.S.; Rodriguez, R. Is selenium intake associated with the presence of depressive symptoms among US adults? Findings from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2014. Nutrition 2019, 62, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niskar, A.S.; Paschal, D.C.; Kieszak, S.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Bowman, B.; Gunter, E.W.; Pirkle, J.L.; Rubin, C.; Sampson, E.J.; McGeehin, M. Serum selenium levels in the US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2003, 91, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasfar, F.; Ben-Nakhi, M.; Khoursheed, M.; Kehinde, E.O.; Alsaleh, M. Selenium is significantly depleted among morbidly obese female patients seeking bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2011, 21, 1710–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, H.; Kumpulainen, J.; Luoma, P.V.; Arranto, A.J.; Sotaniemi, E.A. Decreased serum selenium in alcoholics as related to liver structure and function. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 42, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).