Examining the Composition of the Oral Microbiota as a Tool to Identify Responders to Dietary Changes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

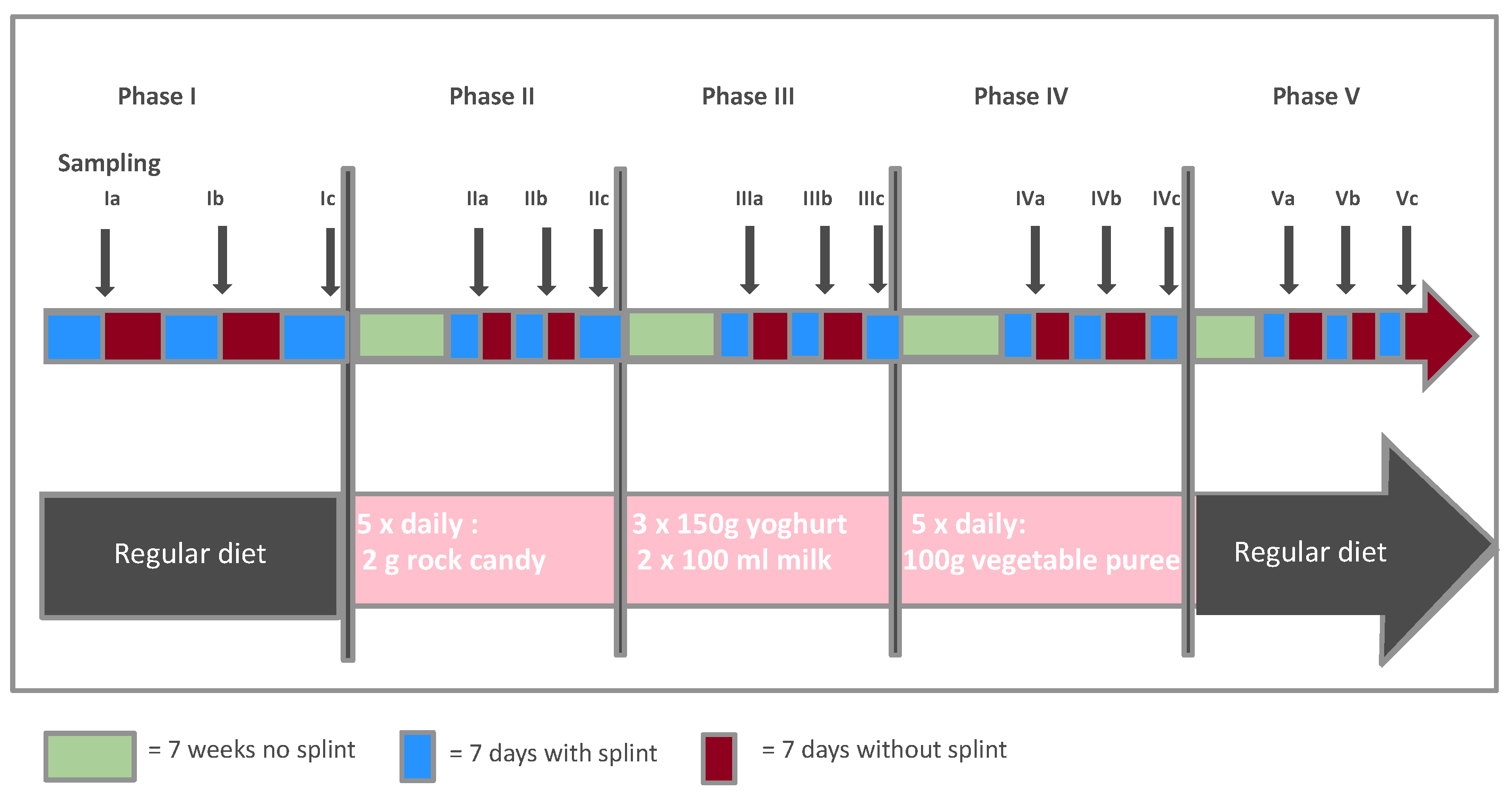

2.1. The Data

2.2. Analytic Strategy

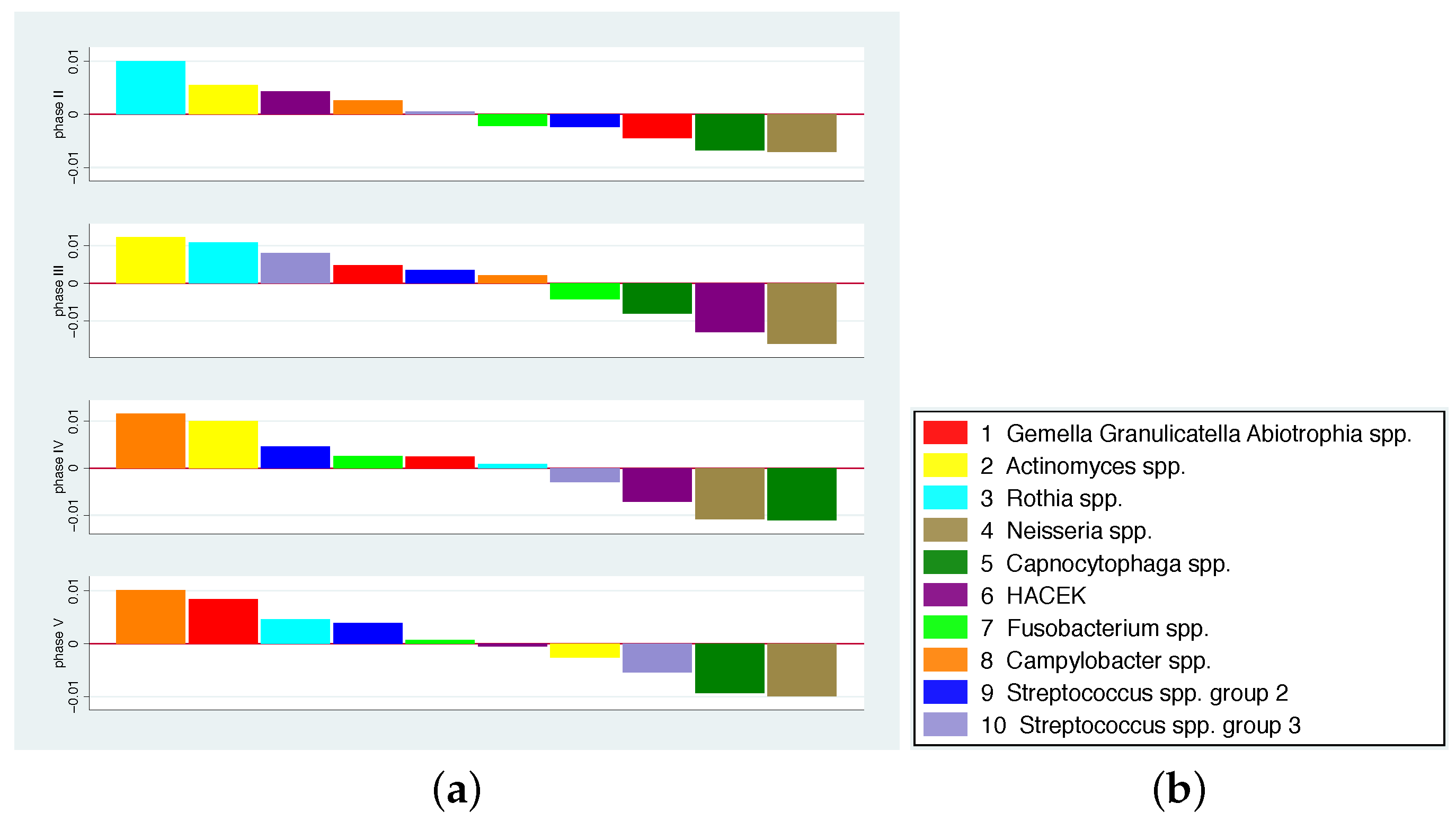

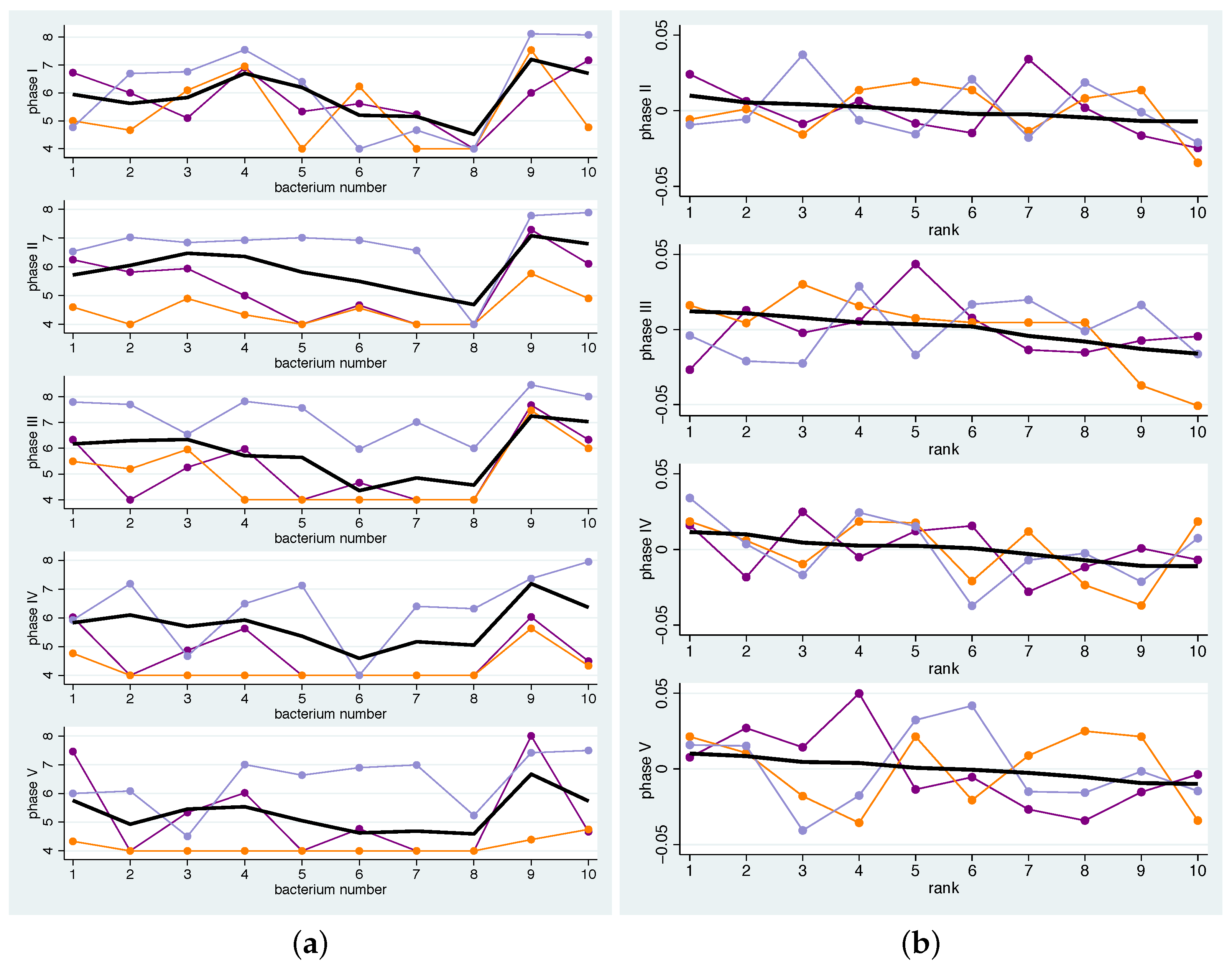

- Since we are interested in investigating the effects of the addition of various dietary components to the overall diet on the microbiome, we presented the changes in concentrations compared to the run-in phase. This means that for each bacterium b and phase p the mean change of its contribution to the total concentration is computed by averaging the individual changes , hence .Hence, a value greater than 0 for a bacterium means that its quantity has increased on average compared to all other bacteria. The bacterium that has increased the most compared to the rest thus receives the largest positive value. Bar charts representing the various bacterial species were used to graphically represent the distribution of changes.

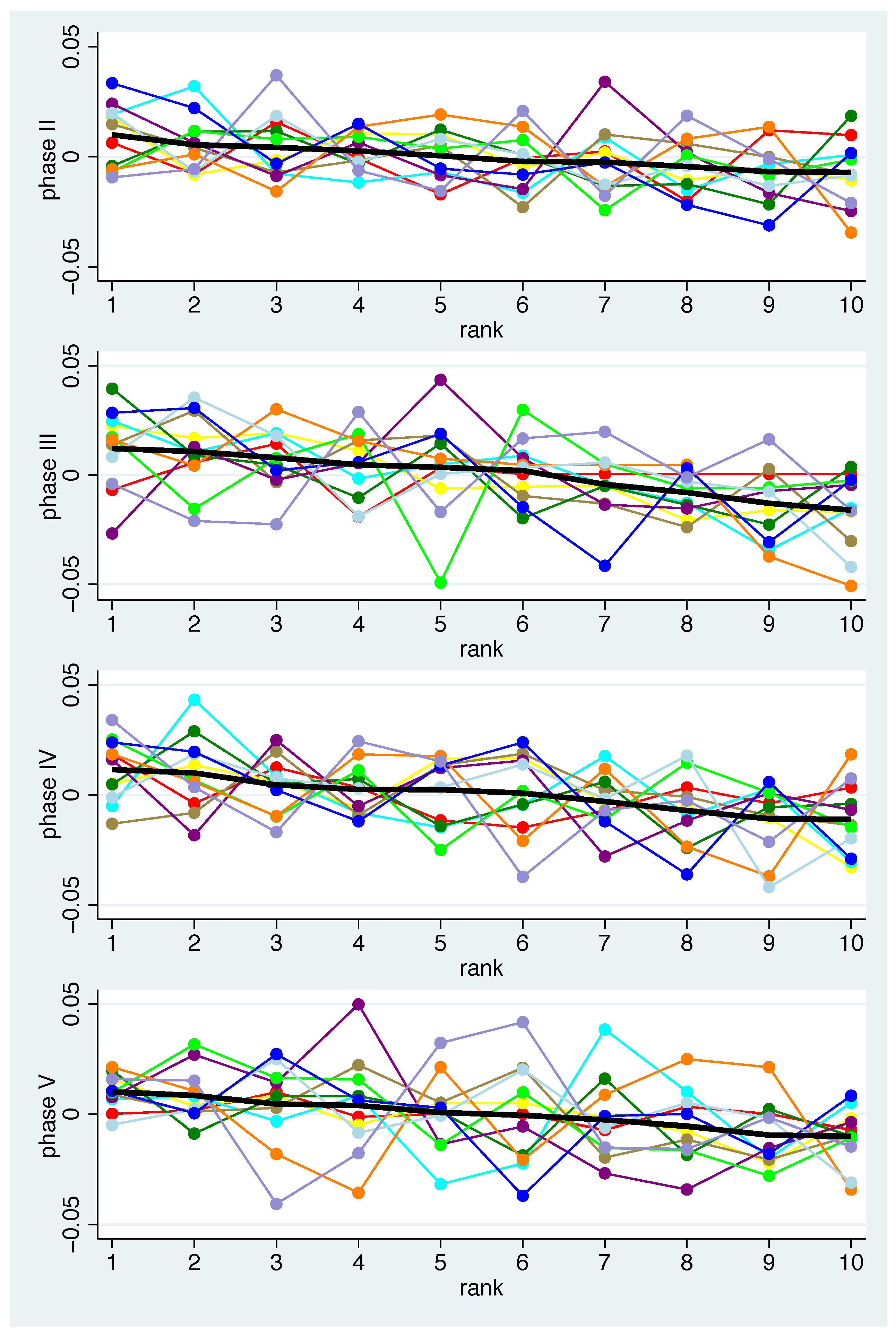

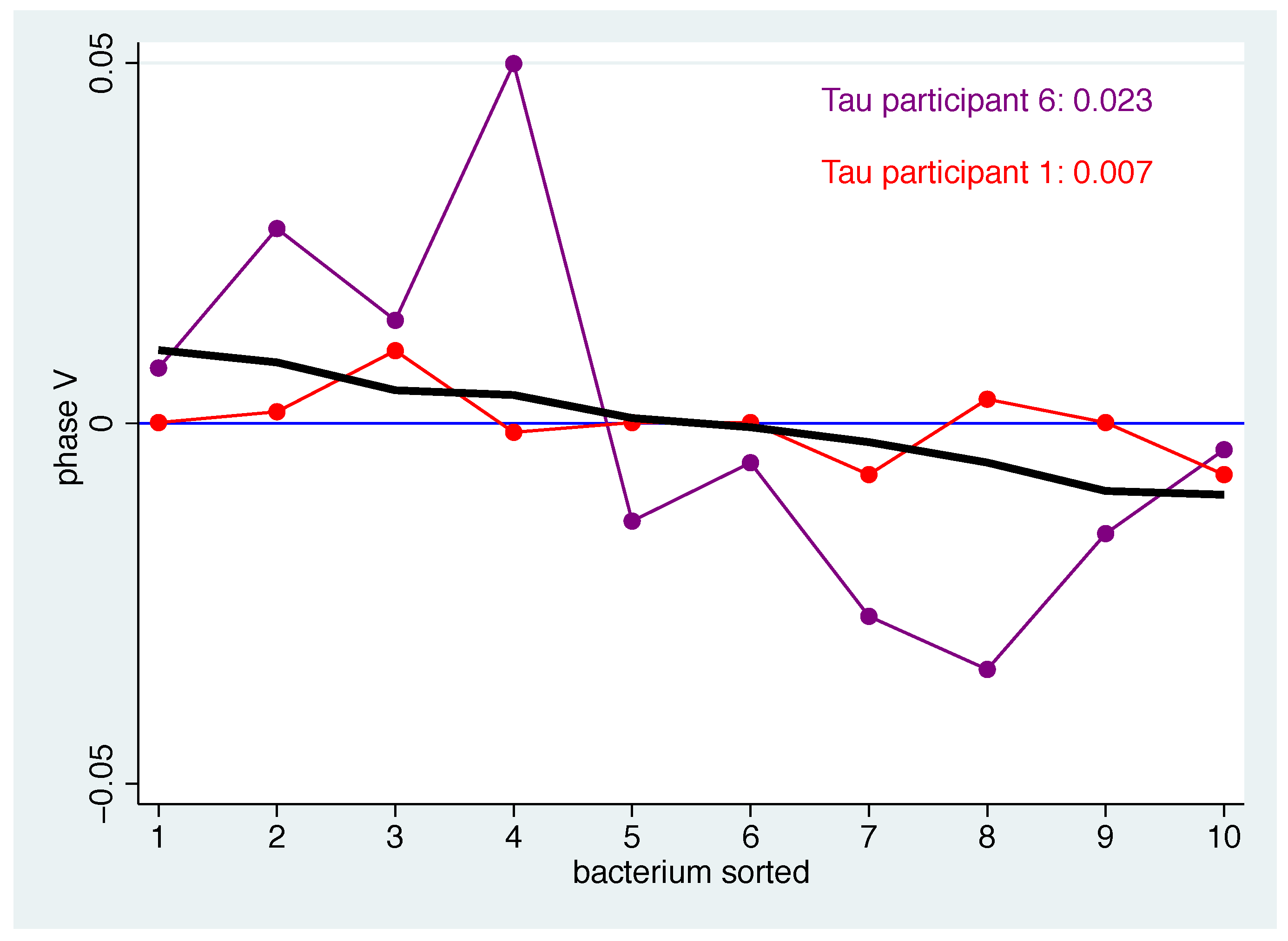

- Secondly, we examined how well the individual patterns match the mean pattern. To quantify the correspondence of the individual pattern with the mean pattern, the average squared distance was computed. In detail, a measure of the distance between the mean pattern and the individual pattern for the bacteria-specific mean changes of bacterium b and participant i can then be computed by for the bacteria to get a measure for each phase p. To avoid overoptimistic results, was replaced by , i.e., when computing the population average for participant i the value for participant i was omitted.

- Thirdly, based on the measure defined in this way, we defined participants as typical responders if their individual patterns match well with the mean pattern in all phases. Consequently, atypical responders are defined as those participants who repeatedly deviate from the expected profile. Specifically, participants are classified as typical (atypical) responders according to the distribution of if their value is smaller (larger) than the 40% (60%) percentile of in all phases.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Description of the Bacterial Groups

- Gemella, Granulicatella, Abiotrophia spp.: Gemella morbillorum, Gemella haemolysans, Gemella sanguinis, Granulicatella adiacens, Granulicatella elegans, Abiotrophia defectiva

- Actinomyces spp.: Actinomyces oris, Actinomyces odontolyticus, Actinomyces dentalis, Actinomyces georgiae, Actinomyces naeslundii

- Rothia spp.: Rothia mucilaginosa, Rothia dentocariosa, Rothia aeria, Corynebacterium spp.

- Neisseria spp.: Neisseria macacae/mucosa, Neisseria oralis, Neisseria subflava, Neisseria bacilliformis, Neisseria elongata, Neisseria flavescens, Neisseria perflava, Neisseria cinerea, Lautropia mirabilis

- Capnocytophaga spp.: Capnocytophaga granulosa, Capnocytophaga gingivalis, Capnocytophaga ochracea, Capnocytophaga sputigena

- HACEK: Haemophilus haemolyticus, Haemophilus parahaemolyticus, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Haemophilus influenzae, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella spp.

- Fusobacterium spp.: Fusobacterium nucleatum, Fusobacterium periodontium

- Campylobacter spp.: Campylobacter rectus, Campylobacter concisus, Campylobacter showae

- Streptococcus spp. group 2: Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus infantis, Streptococcus australis, Streptococcus peroris, Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus vestibularis, Streptococcus anginosus group

- Streptococcus spp. group 3: Streptococcus sanguinis, Streptococcus parasanguinis, Streptococcus gordonii

References

- Deo, P.N.; Deshmukh, R. Oral microbiome: Unveiling the fundamentals. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2019, 23, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, J.R.; Gabaldón, T. The Human Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease: From Sequences to Ecosystems. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, P.; Romei, F.M.; Bondi, D.; Giuliani, M.; Piattelli, A.; Curia, M.C. Microbiota and Oral Cancer as A Complex and Dynamic Microenvironment: A Narrative Review from Etiology to Prognosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Bhatia, S.; Sodhi, A.S.; Batra, N. Oral microbiome and health. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Haake, S.K.; Mannon, P.; Lemon, K.P.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Huttenhower, C.; Izard, J. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghi, L.; DiMassa, V.; Harrington, A.; Lynch, S.V.; Kapila, Y.L. The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease. Periodontol 2000 2021, 87, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.C.; Rothballer, M.; Altenburger, M.J.; Woelber, J.P.; Karygianni, L.; Vach, K.; Hellwig, E.; Al-Ahmad, A. Long-term fluctuation of oral biofilm microbiota following different dietary phases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01421-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, D.J.; Lynch, R.J.M. Diet and the microbial aetiology of dental caries: New paradigms. Int. Dent. J. 2013, 63, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, P.; Petersen, P.E. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of dental diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, S.; Simonetti, R.; Simonetti D’Arca, A. The effect of milk and sucrose consumption on caries in 6-to-11-year-old Italian schoolchildren. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 13, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimutis, W.R. Bioactive Properties of Milk Proteins with Particular Focus on Anticariogenesis. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 989S–995S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, E.C.; Cai, F.; Shen, P.; Walker, G.D. Retention in Plaque and Remineralization of Enamel Lesions by Various Forms of Calcium in a Mouthrinse or Sugar-free Chewing Gum. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 82, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlafer, S.; Ibsen, C.J.S.; Birkedal, H.; Nyvad, B. Calcium-Phosphate-Osteopontin Particles Reduce Biofilm Formation and pH Drops in in situ Grown Dental Biofilms. Caries Res. 2017, 51, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Nyvad, B. Caries ecology revisited: Microbial dynamics and the caries process. Caries Res. 2008, 42, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleskin, A.V. Microbial Communication and Microbiota-Host Interactivity: Neurophysiological, Biotechnological, and Biopolitical Implications; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.C.; Rothballer, M.; Altenburger, M.J.; Woelber, J.P.; Karygianni, L.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Hellwig, E.; Al-Ahmad, A. In-vivo shift of the microbiota in oral biofilm in response to frequent sucrose consumption. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.D. Are dental diseases examples of ecological catastrophes? Microbiology 2003, 149, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosier, B.T.; De Jager, M.; Zaura, E.; Krom, B.P. Historical and contemporary hypotheses on the development of oral diseases: Are we there yet? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.L.; Beall, C.J.; Kutsch, S.R.; Firestone, N.D.; Leys, E.J.; Griffen, A.L. Beyond Streptococcus mutans: Dental Caries Onset Linked to Multiple Species by 16S rRNA Community Analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.N.; Snesrud, E.; Liu, J.; Ong, A.C.; Kilian, M.; Schork, N.J.; Bretz, W. The Dental Plaque Microbiome in Health and Disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, V.P.; Alvarez, A.J.; Luce, A.R.; Bedenbaugh, M.; Mitchell, M.L.; Burne, R.A.; Nascimento, M.M. Microbiomes of Site-Specific Dental Plaques from Children with Different Caries Status. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00106-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Blesso, C.; Luo, Y. A Comprehensive Review of Nanoparticles for Oral Delivery in Food: Biological Fate, Evaluation Models, and Gut Microbiota Influences. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santonocito, S.; Giudice, A.; Polizzi, A.; Troiano, G.; Merlo, E.M.; Sclafani, R.; Grosso, G.; Isola, G. A Cross-Talk between Diet and the Oral Microbiome: Balance of Nutrition on Inflammation and Immune System’s Response during Periodontitis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vach, K.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Anderson, A.; Woelber, J.P.; Karygianni, L.; Wittmer, A.; Hellwig, E. Analysing the Relationship between Nutrition and the Microbial Composition of the Oral Biofilm—Insights from the Analysis of Individual Variability. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vach, K.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Anderson, A.; Woelber, J.P.; Karygianni, L.; Wittmer, A.; Hellwig, E. A Log Ratio-Based Analysis of Individual Changes in the Composition of the Oral Microbiota in Different Dietary Phases. Nutrients 2021, 3, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, S.; Karygianni, L.; Filippi, A.; Anderson, A.C.; Zürcher, A.; Hellwig, E.; Vach, K.; Macchiarelli, G.; Al-Ahmad, A. Combining culture and culture-independent methods reveals new microbial composition of halitosis patients’ tongue biofilm. Microbiol. Open 2020, 9, e958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, E.M.; Alipour, Z.; Wallace, M.A.; Burnham, C.A. Evaluation of Optimal Blood Culture Incubation Time To Maximize Clinically Relevant Results from a Contemporary Blood Culture Instrument and Media System. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e02459-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chastin, S.; Palarea–Albaladejo, J.; Dontje, M.; Skelton, D. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: A Novel Compositional Data Analysis Approach. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín Fernández, J.A.; Daunis i Estadella, J.; Mateu i Figueras, G. On the Interpretation of Differences between Groups for Compositional Data. Sort-Stat. Oper. Res. Trans. 2015, 39, 231–252. Available online: https://dugi-doc.udg.edu/handle/10256/13742 (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Lanzl, M.I.; van Mastrigt, O.; Zwietering, M.H.; Abee, T.; den Besten, H.M.W. Role of substrate availability in the growth of Campylobacter co-cultured with extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Bolton broth. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 363, 109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.W.; Hardt, M.; Zhang, Y.H.; Freire, M.; Ruhl, S. The Human Salivary Proteome Wiki: A Community-Driven Research Platform. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskip, H.; Baird, J.; Barker, M.; Briley, A.L.; D’Angelo, S.; Grote, V.; Koletzko, B.; Lawrence, W.; Manios, Y.; Moschonis, G.; et al. Influences on adherence to diet and physical activity recommendations in women and children: Insights from six European studies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 64, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartha, V.; Exner, L.; Meyer, A.L.; Basrai, M.; Schweikert, D.; Adolph, M.; Bruckner, T.; Meller, C.; Woelber, J.P.; Wolff, D. How to Measure Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet in Dental Studies: Is a Short Adherence Screener Enough? A Comparative Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1300, Erratum in Nutrients 2022, 14, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

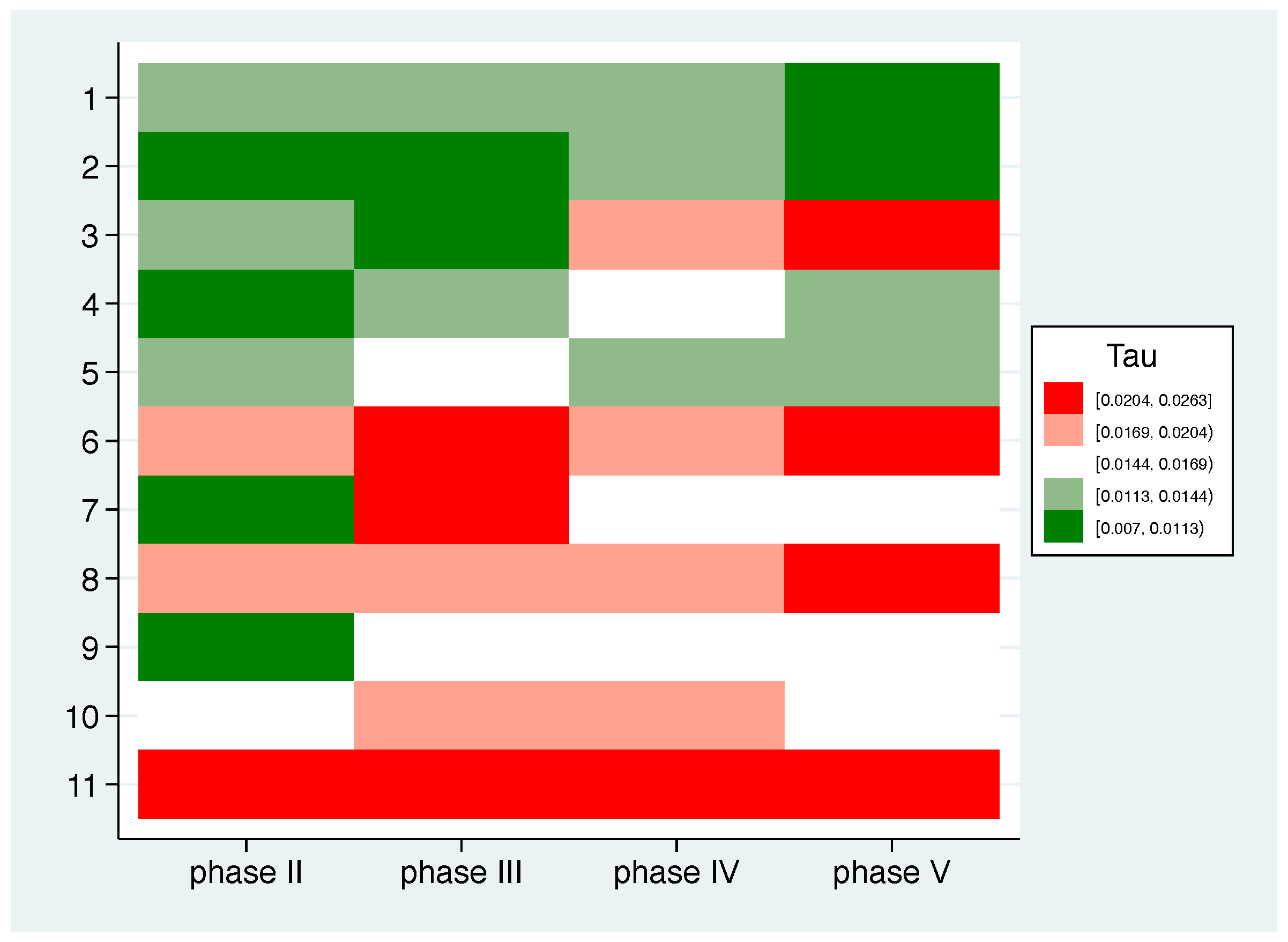

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p II | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.020 | 0.014 ( 0.004) |

| p III | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.020 | 0.024 | 0.017 (0.005) |

| p IV | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.016 ( 0.003) |

| p V | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.026 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.026 | 0.017 ( 0.006) |

| all | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.019 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.016 ( 0.005) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vach, K.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Anderson, A.; Woelber, J.P.; Karygianni, L.; Wittmer, A.; Hellwig, E. Examining the Composition of the Oral Microbiota as a Tool to Identify Responders to Dietary Changes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245389

Vach K, Al-Ahmad A, Anderson A, Woelber JP, Karygianni L, Wittmer A, Hellwig E. Examining the Composition of the Oral Microbiota as a Tool to Identify Responders to Dietary Changes. Nutrients. 2022; 14(24):5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245389

Chicago/Turabian StyleVach, Kirstin, Ali Al-Ahmad, Annette Anderson, Johan Peter Woelber, Lamprini Karygianni, Annette Wittmer, and Elmar Hellwig. 2022. "Examining the Composition of the Oral Microbiota as a Tool to Identify Responders to Dietary Changes" Nutrients 14, no. 24: 5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245389

APA StyleVach, K., Al-Ahmad, A., Anderson, A., Woelber, J. P., Karygianni, L., Wittmer, A., & Hellwig, E. (2022). Examining the Composition of the Oral Microbiota as a Tool to Identify Responders to Dietary Changes. Nutrients, 14(24), 5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245389