Psychiatric Symptoms and Frequency of Eating out among Commuters in Beijing: A Bidirectional Association?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

2.2. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Symptoms

2.3. Frequency of Eating out

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Sensitivity Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

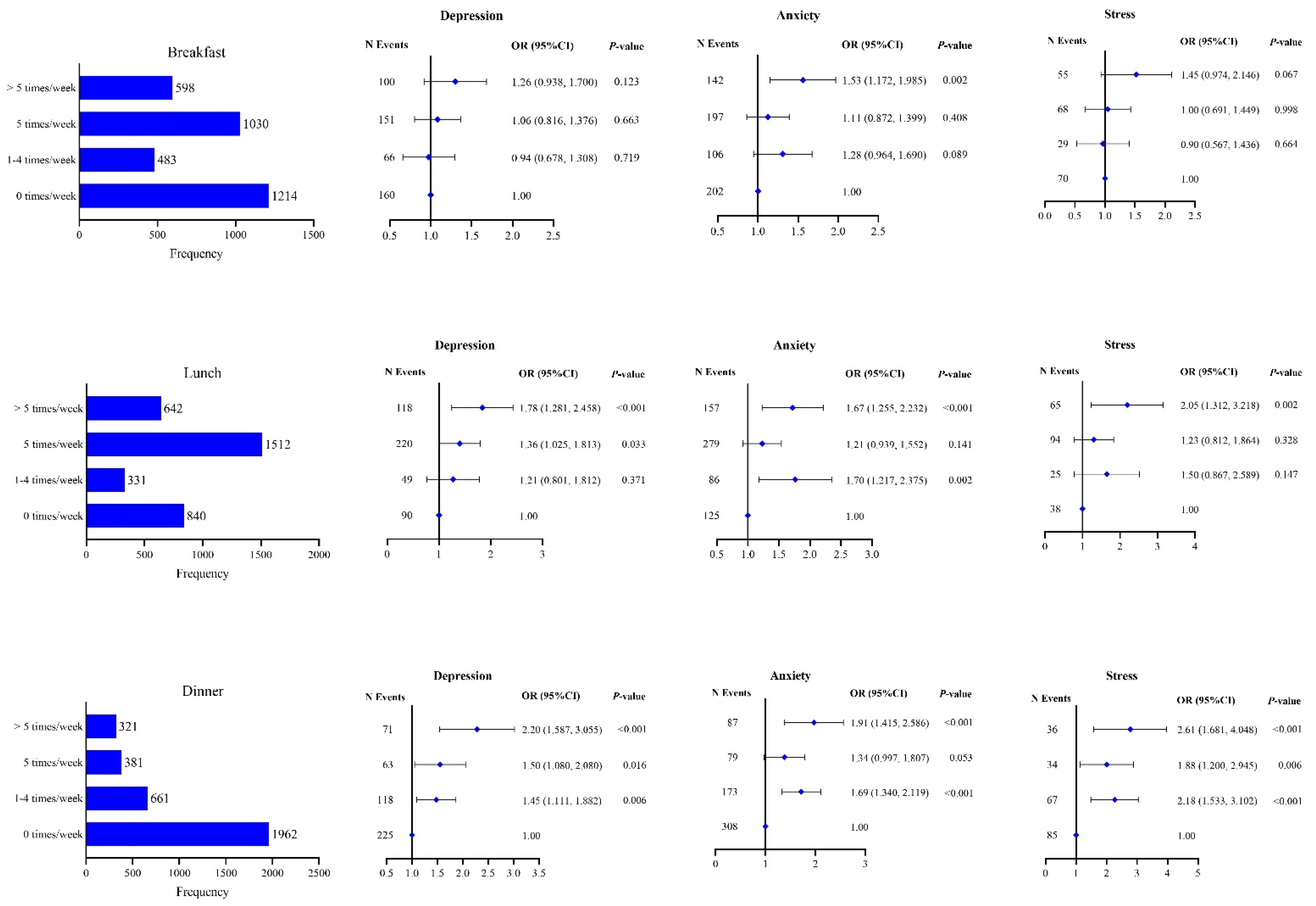

3.2. Distribution of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress according to the Frequency of Eating out

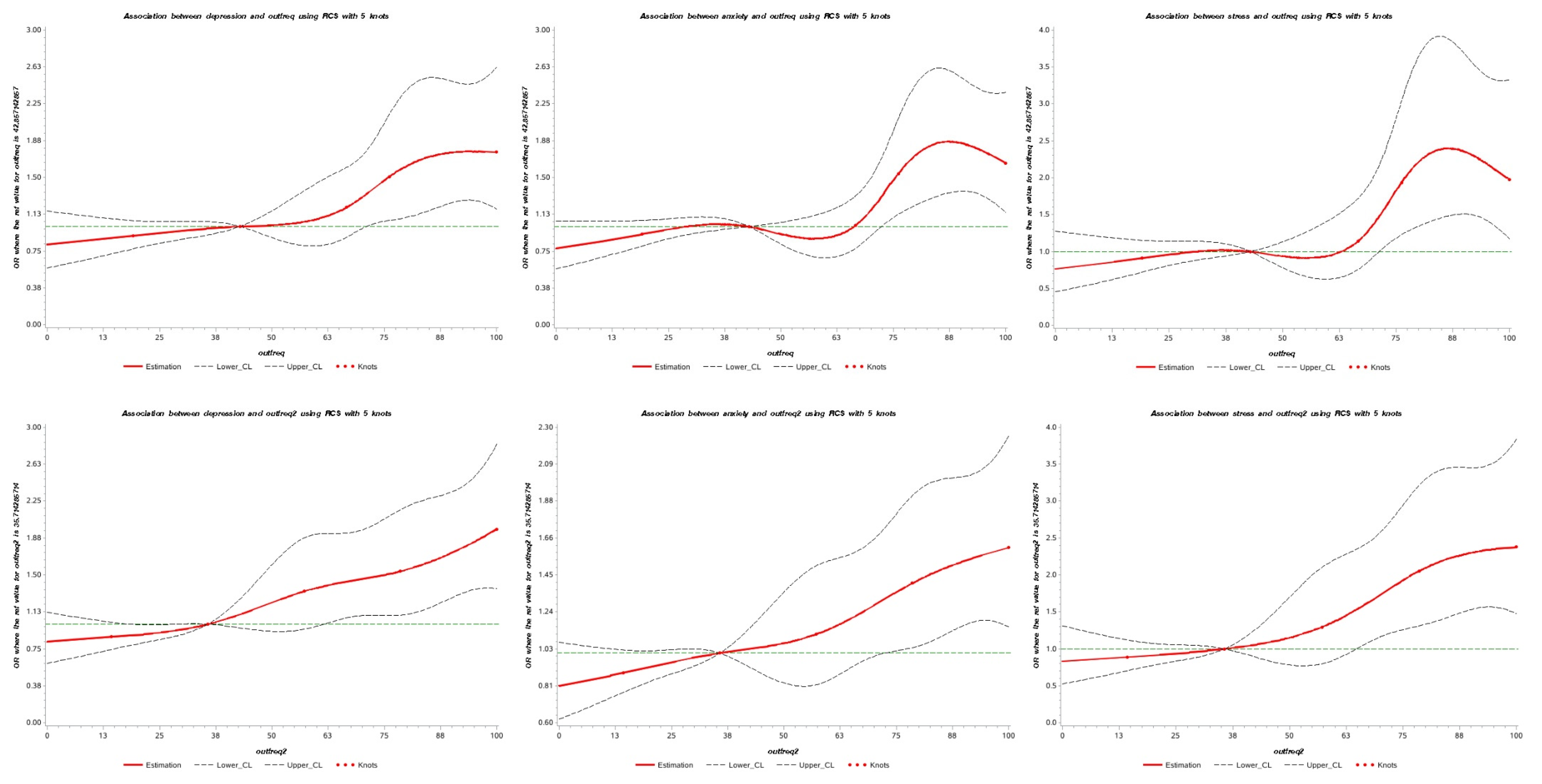

3.3. Associations between Frequency of Eating out and Mental Health

3.4. Associations between Psychiatric Symptoms and the Frequency of Eating Out

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis for Unmeasured Confounders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janssen, H.G.; Davies, I.G.; Richardson, L.D.; Stevenson, L. Determinants of takeaway and fast food consumption: A narrative review. Nutr Res Rev. 2018, 31, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, J.Y.; Garriguet, D. Eating away from home in Canada: Impact on dietary intake. Health Rep. 2021, 32, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; He, Y.; Zhuo, Q.; Yang, X. Status of dietary fat intake of Chinese residents in different dining locations and times. J. Hyg. Res. 2016, 45, 236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Goffe, L.; Rushton, S.; White, M.; Adamson, A.; Adams, J. Relationship between mean daily energy intake and frequency of consumption of out-of-home meals in the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, I.N.; Medeiros, H.B.; de Moura Souza, A.; Sichieri, R. Contribution of away-from-home food to the energy and nutrient intake among Brazilian adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3371–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachat, C.; Nago, E.; Verstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Ahn, B.-I. Eating Out and Consumers’ Health: Evidence on Obesity and Balanced Nutrition Intakes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, A.K.; Whitley, M.I.; Graubard, B.I. Away from home meals: Associations with biomarkers of chronic disease and dietary intake in American adults, NHANES 2005–2010. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2015, 39, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Rong, S.; Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Wallace, R.B.; Bao, W. Association Between Frequency of Eating Away-From-Home Meals and Risk of All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1741–1749.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Wang, L.; Xue, Q.; Yin, L.; Zhu, B.-H.; Wang, K.; Shangguan, F.-F.; Zhang, P.-R.; Niu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, W.-R.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Epidemic: Allostatic Load among Medical and Nonmedical Workers in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021, 90, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R.S.; Choo, F.N.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharma, V.K.; et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouso, J.C.; Jiménez-Garrido, D.; Ona, G.; Woźnica, D.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Paranhos, B.A.P.B.; de Almeida Mendes, F.; Yonamine, M.; Alcázar-Córcoles, M.Á.; et al. Quality of Life, Mental Health, Personality and Patterns of Use in Self-Medicated Cannabis Users with Chronic Diseases: A 12-Month Longitudinal Study. Phytother Res. 2020, 34, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, S.B.; Epstein, R.M.; Glozier, N.; Petrie, K.; Strudwick, J.; Gayed, A.; Dean, K.; Henderson, M. Mental illness and suicide among physicians. Lancet 2021, 398, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond-Rakerd, L.S.; D’Souza, S.; Milne, B.J.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E. Longitudinal Associations of Mental Disorders with Physical Diseases and Mortality among 2.3 Million New Zealand Citizens. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2033448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Teasdale, S.B.; Ward, P.B.; Veronese, N.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Berk, M.; Yung, A.R.; Sarris, J. Diet as a hot topic in psychiatry: A population-scale study of nutritional intake and inflammatory potential in severe mental illness. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, R.A.H.; van der Beek, E.M.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Hebebrand, J.; Higgs, S.; Schellekens, H.; Dickson, S.L. Nutritional psychiatry: Towards improving mental health by what you eat. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.R.; He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A.; Graudal, N. Sodium and health-concordance and controversy. BMJ 2020, 369, m2440, Epub 28 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Cao, H.; Guo, C.; Pan, L.; Cui, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhao, W.; Han, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Environmental and Genetic Determinants of Major Chronic Disease in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region: Protocol for a Community-Based Cohort Study. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 659701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Guo, C.; Cao, H.; Liu, K.; Peng, W.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, F.; Wen, F.; et al. Impact of lipoprotein(a) level on cardiometabolic disease in the Chinese population: The CHCN-BTH Study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 52, e13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yohannes, A.M.; Dryden, S.; Hanania, N.A. Validity and Responsiveness of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in COPD. Chest 2019, 155, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Cao, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Niu, K.; Tang, N.; Cui, Z.; Pan, L.; Yao, C.; Gao, Q.; et al. Association of chronic diseases with depression, anxiety and stress in Chinese general population: The CHCN-BTH cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D. The convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21). J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lu, F.C. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Env. Sci. 2004, 17, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.G.; Simera, I.; Hoey, J.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K. EQUATOR: Reporting guidelines for health research. Lancet 2008, 371, 1149–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Ding, P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, M.B.; Ding, P.; Riddell, C.A.; VanderWeele, T.J. Web Site and R Package for Computing E-values. Epidemiology 2018, 29, e45–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Lu, Z.-A.; Que, J.-Y.; Huang, X.-L.; Liu, L.; Ran, M.-S.; Gong, Y.-M.; Yuan, K.; Yan, W.; Sun, Y.-K.; et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors Associated with Mental Health Symptoms among the General Population in China during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2014053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, J.M.; Pinto, D.M.; Vecino-Ortiz, A.I.; Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Rondón, M. Presenteeism, Absenteeism, and Lost Work Productivity among Depressive Patients from Five Cities of Colombia. Value Health Reg. Issues 2017, 14, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.; Cho, E.; Kavelaars, R.; Jamieson, M.; Bao, B.; Rehm, J. Economic analyses of mental health and substance use interventions in the workplace: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, C.; Elovainio, M.; Arffman, M.; Lumme, S.; Pirkola, S.; Keskimäki, I.; Manderbacka, K.; Böckerman, P. Mental disorders and long-term labour market outcomes: Nationwide cohort study of 2 055 720 individuals. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 140, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, M.; Firth, J.; Miola, A.; Fornaro, M.; Frison, E.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Dragioti, E.; Shin, J.I.; Carvalho, A.F.; Stubbs, B.; et al. Disparities in cancer screening in people with mental illness across the world versus the general population: Prevalence and comparative meta-analysis including 4717839 people. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.E.; Banner, J.; Jensen, S.E. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.F.; Kolade, A.; Gellatly, J.; Osam, C.S.; Perchard, R.; Kosidou, K.; Dalman, C.; Morgan, V.; Di Prinzio, P.; et al. Effects of parental mental illness on children’s physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 217, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellard-Cole, L.; Davies, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Contribution of foods prepared away from home to intakes of energy and nutrients of public health concern in adults: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 5511–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Moseley, G.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F. Nutritional psychiatry: The present state of the evidence. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, L.; Corfe, B. The role of diet and nutrition on mental health and wellbeing. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hueston, C.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Nolan, Y.M. Stress and adolescent hippocampal neurogenesis: Diet and exercise as cognitive modulators. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigo, D.; Thornicroft, G.; Atun, R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Kou, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample, n (%) | 3337 (100%) | 2494 (74.74%) | 843 (25.26%) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 38.78 ± 10.41 | 39.40 ± 10.92 | 36.95 ± 8.47 |

| Education | |||

| Senior secondary | 864 (25.89) | 712 (28.55) | 152 (18.03) |

| University or college | 2010 (60.23) | 1502 (60.22) | 508 (60.26) |

| Postgraduate and above | 463 (13.87) | 280 (11.23) | 183 (21.71) |

| Marriage | |||

| Single | 723 (21.67) | 558 (22.37) | 165 (19.57) |

| Married | 2614 (78.33) | 1936 (77.63) | 678 (80.43) |

| Smoking | |||

| Never a smoker | 1986 (59.69) | 1157 (46.54) | 829 (98.57) |

| Previous smoker | 206 (6.19) | 204 (8.21) | 2 (0.24) |

| Current smoker | 1135 (34.11) | 1125 (42.25) | 10 (1.19) |

| Drinking | |||

| Never a drinker | 1478 (44.38) | 764 (30.71) | 714 (84.80) |

| Previous drinker | 124 (3.72) | 120 (4.82) | 4 (0.48) |

| Current drinker | 1728 (51.89) | 1604 (64.47) | 124 (14.73) |

| Exercise | |||

| 5–7 d/w | 727 (21.79) | 600 (24.06) | 127 (15.07) |

| 1–4 d/w | 1233 (36.95) | 927 (37.17) | 306 (36.30) |

| <1 d/w | 1377 (41.26) | 967 (38.77) | 410 (48.64) |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight | 78 (2.50) | 31 (1.32) | 47 (6.14) |

| Normal | 1184 (37.96) | 723 (30.73) | 461 (60.18) |

| Overweight | 1197 (38.38) | 1019 (43.31) | 178 (23.24) |

| Obesity | 660 (21.16) | 580 (24.65) | 80 (10.44) |

| Frequency of eating out for breakfast | |||

| 0 times per week | 1207 (36.42) | 798 (32.22) | 409 (48.86) |

| 1–4 times per week | 483 (14.57) | 372 (15.02) | 111 (13.26) |

| 5 times per week | 1028 (31.02) | 815 (32.90) | 213 (25.45) |

| >5 times per week | 596 (17.98) | 492 (19.86) | 104 (12.43) |

| Frequency of eating out for lunch | |||

| 0 times per week | 836 (25.23) | 564 (22.77) | 272 (32.50) |

| 1–4 times per week | 331 (9.99) | 237 (9.57) | 94 (11.23) |

| 5 times per week | 1507 (45.47) | 1158 (46.75) | 349 (41.70) |

| >5 times per week | 640 (19.31) | 518 (20.91) | 122 (14.58) |

| Frequency of eating out for dinner | |||

| 0 times per week | 1955 (58.99) | 1402 (56.60) | 553 (66.07) |

| 1–4 times per week | 659 (19.89) | 499 (20.15) | 160 (19.12) |

| 5 times per week | 380 (11.47) | 301 (12.15) | 79 (9.44) |

| >5 times per week | 320 (9.66) | 275 (11.10) | 45 (5.38) |

| Rate of eating out | |||

| 0% | 541 (16.32) | 343 (13.85) | 198 (23.66) |

| 1–50% | 1669 (50.36) | 1234 (49.82) | 435 (51.97) |

| 51–100% | 1104 (33.31) | 900 (36.33) | 204 (24.37) |

| Chronic diseases | 748 (22.47) | 635 (25.51) | 113 (13.45) |

| Depression | 477 (14.40) | 348 (14.06) | 129 (15.41) |

| Anxiety | 650 (19.63) | 469 (18.95) | 181 (21.62) |

| Stress | 222 (6.70) | 173 (6.99) | 49 (5.85) |

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of eating out for breakfast | |||

| 0 times per week | 160 (13.23) | 202 (16.71) | 70 (5.79) |

| 1–4 times per week | 66 (13.72) | 106 (22.04) | 29 (6.03) |

| 5 times per week | 151 (14.76) | 197 (19.26) | 68 (6.65) |

| >5 times per week | 100 (16.86) | 142 (23.95) | 55 (9.27) |

| (P) | −2.027 (0.043) | −3.201 (0.001) | −2.489 (0.013) |

| Frequency of eating out for lunch | |||

| 0 times per week | 90 (10.77) | 125 (14.95) | 38 (4.55) |

| 1–4 times per week | 49 (14.80) | 86 (25.98) | 25 (7.55) |

| 5 times per week | 220 (14.65) | 279 (18.58) | 94 (6.26) |

| >5 times per week | 118 (18.52) | 157 (24.65) | 65 (10.20) |

| (P) | −4.00 (<0.001) | −3.637 (<0.001) | −3.637 (<0.001) |

| Frequency of eating out for dinner | |||

| 0 times per week | 225 (11.53) | 308 (15.78) | 85 (4.35) |

| 1–4 times per week | 118 (17.93) | 173 (26.29) | 67 (10.18) |

| 5 times per week | 63 (16.62) | 79 (20.84) | 34 (8.97) |

| >5 times per week | 71 (22.40) | 87 (27.44) | 36 (11.36) |

| (P) | −5.693 (<0.001) | −5.622 (<0.001) | −5.818 (<0.001) |

| Rate of eating out | |||

| 0% | 56 (10.37) | 75 (13.89) | 22 (4.07) |

| 1–50% | 222 (13.30) | 310 (18.57) | 94 (5.63) |

| 51–100% | 199 (18.14) | 262 (23.88) | 106 (9.66) |

| (P) | −4.538 (<0.001) | −5.004 (<0.001) | −4.739 (<0.001) |

| Psychiatric Symptoms | 1–50% | 51–100% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | OR (95% CI) | No. | OR (95% CI) | |

| Depression | ||||

| No | 1447 | ref | 898 | ref |

| Yes | 222 | 1.01 (0.662, 1.528) | 199 | 1.21 (0.776, 1.897) |

| Anxiety | ||||

| No | 1359 | ref | 835 | ref |

| Yes | 310 | 1.32 (0.920, 1.891) | 262 | 1.46 (0.991, 2.152) |

| Stress | ||||

| No | 1575 | ref | 991 | ref |

| Yes | 94 | 0.98 (0.544, 1.755) | 106 | 1.34 (0.732, 2.463) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Xie, Y.; Li, B.; Weng, F.; Zhang, F.; Xia, J. Psychiatric Symptoms and Frequency of Eating out among Commuters in Beijing: A Bidirectional Association? Nutrients 2022, 14, 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204221

Zhang L, Xie Y, Li B, Weng F, Zhang F, Xia J. Psychiatric Symptoms and Frequency of Eating out among Commuters in Beijing: A Bidirectional Association? Nutrients. 2022; 14(20):4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204221

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ling, Yunyi Xie, Bingxiao Li, Fuyuan Weng, Fengxu Zhang, and Juan Xia. 2022. "Psychiatric Symptoms and Frequency of Eating out among Commuters in Beijing: A Bidirectional Association?" Nutrients 14, no. 20: 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204221

APA StyleZhang, L., Xie, Y., Li, B., Weng, F., Zhang, F., & Xia, J. (2022). Psychiatric Symptoms and Frequency of Eating out among Commuters in Beijing: A Bidirectional Association? Nutrients, 14(20), 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204221