The Effect of a Multivitamin and Mineral Supplement on Immune Function in Healthy Older Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

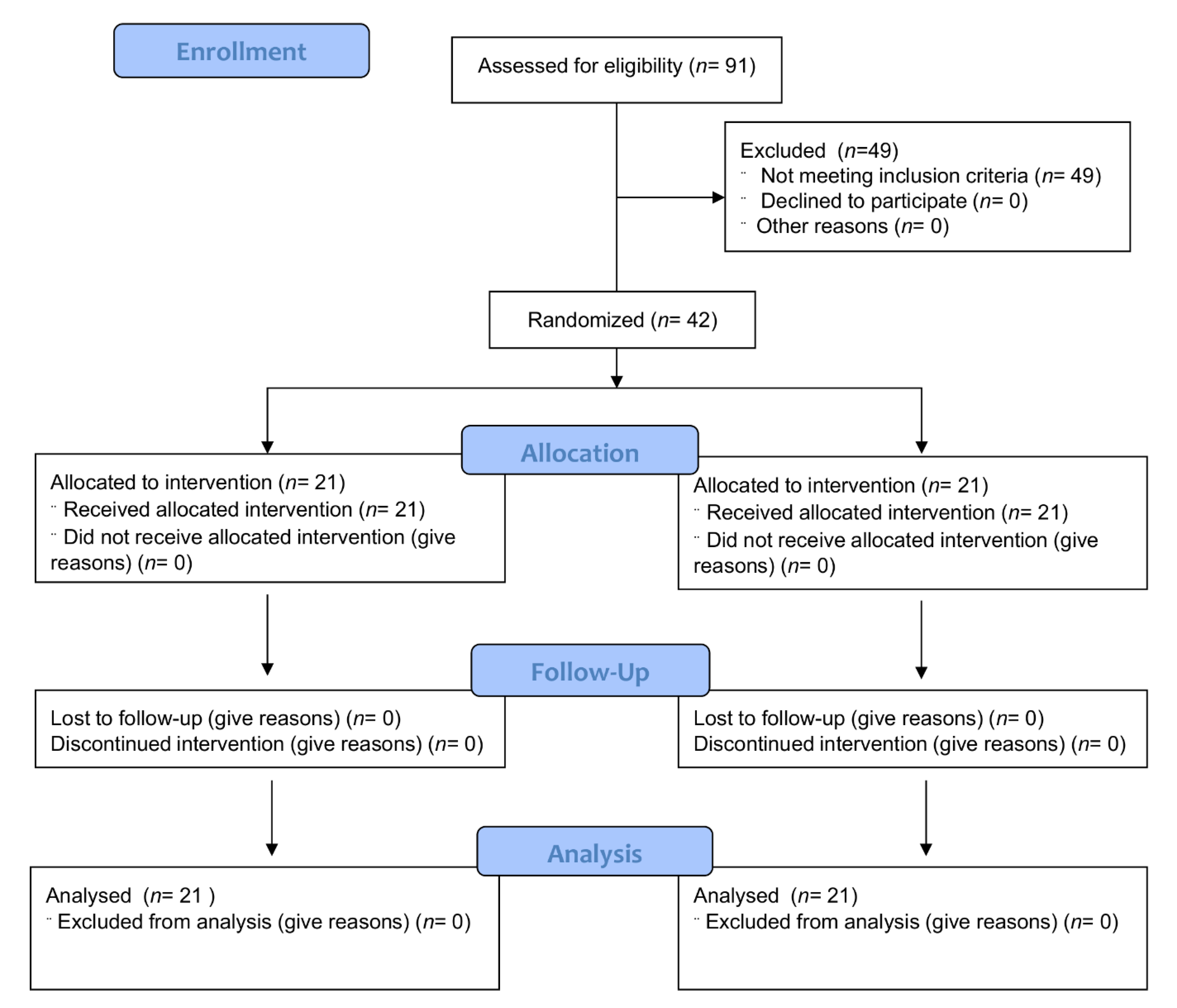

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Method of Assigning Participants to Intervention Groups

2.4. Intervention and Sample Collection

2.5. Whole Blood Killing Assay

2.6. Phagocytic Activity, Total ROS Generation, Cytokine and Salivary IgA Measurements

2.7. Vitamin C, D and Zinc Assessment

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Compliance

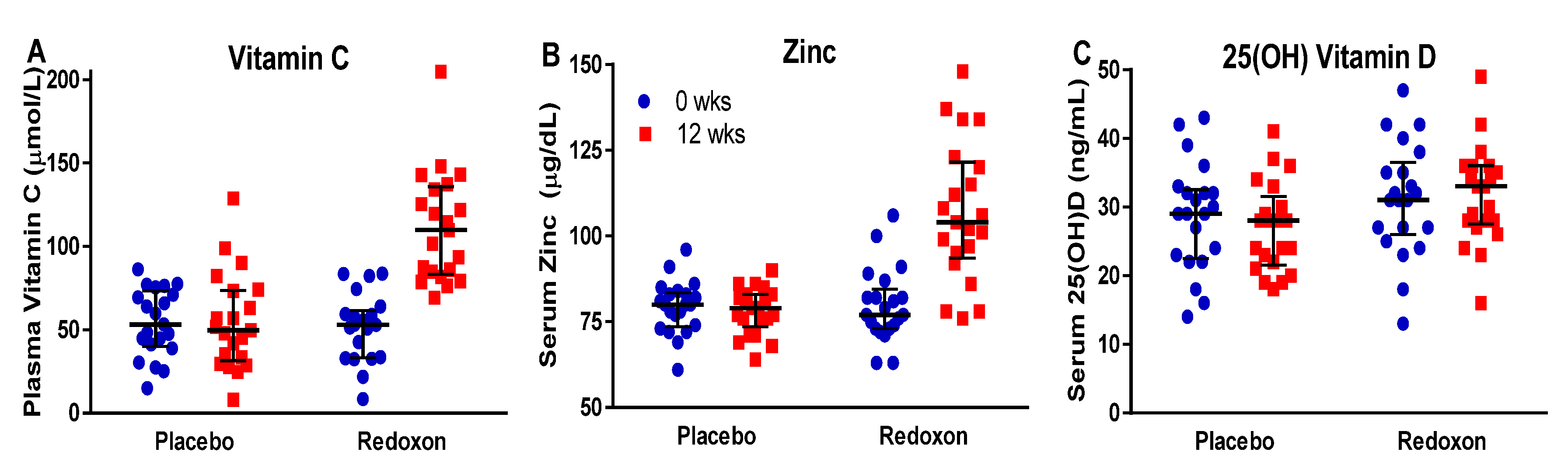

3.3. Response to Supplementation

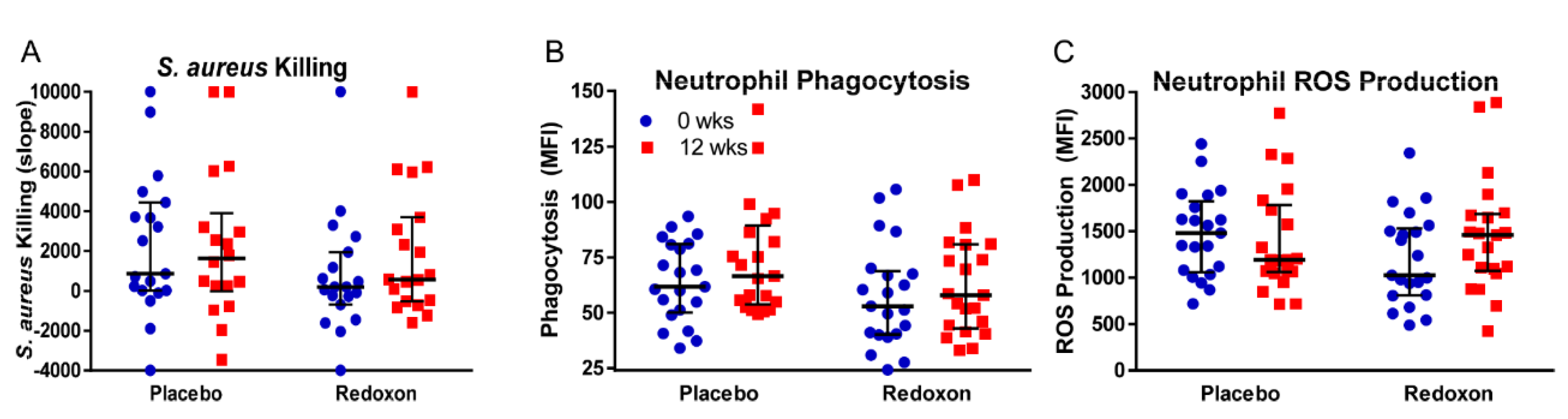

3.4. Whole Blood Killing of S. aureus

3.5. Neutrophil Phagocytosis

3.6. Neutrophil Superoxide Production

3.7. Salivary IgA and Serum Inflammatory Cytokine Levels

3.8. Reported Illness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darnton-Hill, I. Public Health Aspects in the Prevention and Control of Vitamin Deficiencies. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- High, K.P. Nutritional strategies to boost immunity and prevent infection in elderly individuals. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, R.K. Nutrition and the immune system from birth to old age. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, S73–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagaria, M.A.E. Vitamin Deficiencies in Seniors. USA Pharm. 2010, 35, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brubacher, D.; Moser, U.; Jordan, P. Vitamin C concentrations in plasma as a function of intake: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2000, 70, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.S. Zinc: An antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent: Role of zinc in degenerative disorders of aging. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2014, 28, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.P. Vitamin D and ageing. Biogerontology 2010, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D deficiency in 2010: Health benefits of vitamin D and sunlight: A D-bate. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 7, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, M.; Penckofer, S. The Role of Vitamin D in the Aging Adult. J. Aging Gerontol. 2014, 2, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.P.; Ho, E. Zinc and its role in age-related inflammation and immune dysfunction. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maywald, M.; Rink, L. Zinc homeostasis and immunosenescence. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2015, 29, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solana, R.; Tarazona, R.; Gayoso, I.; Lesur, O.; Dupuis, G.; Fulop, T. Innate immunosenescence: Effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Semin. Immunol. 2012, 24, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannizzo, E.S.; Clement, C.C.; Sahu, R.; Follo, C.; Santambrogio, L. Oxidative stress, inflamm-aging and immunosenescence. J. Proteom. 2011, 74, 2313–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gombart, A.F.; Pierre, A.; Maggini, S. A Review of Micronutrients and the Immune System-Working in Harmony to Reduce the Risk of Infection. Nutrients 2020, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C.; Carr, A.C.; Gombart, A.F.; Eggersdorfer, M. Optimal Nutritional Status for a Well-Functioning Immune System Is an Important Factor to Protect against Viral Infections. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzl, E.J.; Wasserman, S.I.; Gigli, I.; Austen, K.F. Enhancement of random migration and chemotactic response of human leukocytes by ascorbic acid. J. Clin. Invest. 1974, 53, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovitz, B.; Siegel, B.V. Ascorbic acid, neutrophil function, and the immune response. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1978, 48, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, C.E.; DeChatelet, L.R.; Cooper, M.R.; Ashburn, P. The effects of ascorbic acid on bactericidal mechanisms of neutrophils. J. Infect. Dis. 1971, 124, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boura, P.; Tsapas, G.; Papadopoulou, A.; Magoula, I.; Kountouras, G. Monocyte locomotion in anergic chronic brucellosis patients: The in vivo effect of ascorbic acid. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 1989, 11, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, N.; Eggermann, J.; Voo, S.; Kranz, A.; Waltenberger, J. Smoking-induced monocyte dysfunction is reversed by vitamin C supplementation in vivo. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, H.; Rink, L. Multiple impacts of zinc on immune function. Metallomics 2014, 6, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels, I.; Maywald, M.; Rink, L. Zinc as a Gatekeeper of Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, W.L.; Huff, J.C.; Humbert, J.R.; Hambidge, K.M.; Neldner, K.H.; Walravens, P.A. Zinc correction of defective chemotaxis in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Arch. Dermatol. 1977, 113, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Nestel, F.P.; Bourdeau, V.; Nagai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liao, J.; Tavera-Mendoza, L.; Lin, R.; Hanrahan, J.W.; Mader, S.; et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2909–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombart, A.F.; Borregaard, N.; Koeffler, H.P. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemila, H. Vitamin C and Infections. Nutrients 2017, 9, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemila, H.; Chalker, E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, CD000980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, H.; Mocchegiani, E.; Rink, L. Correlation between zinc status and immune function in the elderly. Biogerontology 2006, 7, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Hess, J.W.; Kaplan, J.; Pelen, F.; Dardenne, M. Zinc deficiency in elderly patients. Nutrition 1993, 9, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.S.; Beck, F.W.; Bao, B.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Snell, D.C.; Steinberg, J.D.; Cardozo, L.J. Zinc supplementation decreases incidence of infections in the elderly: Effect of zinc on generation of cytokines and oxidative stress. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrus, E.J.; Lawson, K.A.; Bucci, L.R.; Blum, K. Randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical study of the effectiveness of zinc acetate lozenges on common cold symptoms in allergy-tested subjects. Curr. Ther Res. Clin. Exp. 1998, 59, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Bao, B.; Beck, F.W.; Chandrasekar, P.H. Duration of symptoms and plasma cytokine levels in patients with the common cold treated with zinc acetate. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Beck, F.W.; Bao, B.; Snell, D.; Fitzgerald, J.T. Duration and severity of symptoms and levels of plasma interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor, and adhesion molecules in patients with common cold treated with zinc acetate. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemila, H.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Petrus, E.J.; Prasad, A. Zinc Acetate Lozenges May Improve the Recovery Rate of Common Cold Patients: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, ofx059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.X.; Win, S.S.; Pang, J. Zinc Supplementation Reduces Common Cold Duration among Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials with Micronutrients Supplementation. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, A.R.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Hooper, R.L.; Greenberg, L.; Aloia, J.F.; Bergman, P.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Esposito, S.; Ganmaa, D.; Ginde, A.A.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 2017, 356, i6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Miccono, A.; Lamburghini, S.; Avanzato, I.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Faliva, M.A.; Peroni, G.; Nichetti, M.; Perna, S. Self-Care for Common Colds: The Pivotal Role of Vitamin D, Vitamin C, Zinc, and Echinacea in Three Main Immune Interactive Clusters (Physical Barriers, Innate and Adaptive Immunity) Involved during an Episode of Common Colds-Practical Advice on Dosages and on the Time to Take These Nutrients/Botanicals in order to Prevent or Treat Common Colds. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 5813095. [Google Scholar]

- Maggini, S.; Beveridge, S.; Suter, M. A combination of high-dose vitamin C plus zinc for the common cold. J. Int. Med. Res. 2012, 40, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggini, S.; Pierre, A.; Calder, P.C. Immune Function and Micronutrient Requirements Change over the Life Course. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, B.; Brown, R.L.; Mundt, M.P.; Thomas, G.R.; Barlow, S.K.; Highstrom, A.D.; Bahrainian, M. Validation of a short form Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WURSS-21). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyme, P.; Thoennissen, N.H.; Tseng, C.W.; Thoennissen, G.B.; Wolf, A.J.; Shimada, K.; Krug, U.O.; Lee, K.; Muller-Tidow, C.; Berdel, W.E.; et al. C/EBPepsilon mediates nicotinamide-enhanced clearance of Staphylococcus aureus in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 3316–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, B.; England, L.; Ames, B.N. Ascorbate is an outstanding antioxidant in human blood plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6377–6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, M.B.; Kettle, A.J.; Winterbourn, C.C. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: Oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood 1998, 92, 3007–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, S.; Chahel, H.; Lord, J.M. Review article: Ageing and the neutrophil: No appetite for killing? Immunology 2000, 100, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilotri, P.G. Phagocytosis and leukocyte enzymes in ascorbic acid deficient guinea pigs. J. Nutr. 1977, 107, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, M.C. Reduced bactericidal activity in neutrophils from scorbutic animals and the effect of ascorbic acid on these target bacteria in vivo and in vitro. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 1214S–1220S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, M.C.; Wilkie, R.P. Ascorbate deficiency results in impaired neutrophil apoptosis and clearance and is associated with up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 81, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozonet, S.M.; Carr, A.C.; Pullar, J.M.; Vissers, M.C. Enhanced human neutrophil vitamin C status, chemotaxis and oxidant generation following dietary supplementation with vitamin C-rich SunGold kiwifruit. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2574–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.; Rink, L.; Haase, H. Chelation of Free Zn(2)(+) Impairs Chemotaxis, Phagocytosis, Oxidative Burst, Degranulation, and Cytokine Production by Neutrophil Granulocytes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 171, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibs, K.H.; Rink, L. Zinc-altered immune function. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1452S–1456S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretz, A.; Cantinieaux, B.; Neve, J.; Siderova, V.; Fondu, P. Effects of zinc supplementation on the phagocytic functions of polymorphonuclears in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. J. Trace Elem. Electrolytes Health Dis. 1994, 8, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Liugan, M.; Carr, A.C. Vitamin C and Neutrophil Function: Findings from Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolvers, D.A.; van Herpen-Broekmans, W.M.; Logman, M.H.; van der Wielen, R.P.; Albers, R. Effect of a mixture of micronutrients, but not of bovine colostrum concentrate, on immune function parameters in healthy volunteers: A randomized placebo-controlled study. Nutr. J. 2006, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieman, D.C.; Henson, D.A.; Sha, W. Ingestion of micronutrient fortified breakfast cereal has no influence on immune function in healthy children: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D.C.; Skinner, M.A.; Wolber, F.M.; Booth, C.L.; Loh, J.M.; Wohlers, M.; Stevenson, L.M.; Kruger, M.C. Consumption of gold kiwifruit reduces severity and duration of selected upper respiratory tract infection symptoms and increases plasma vitamin C concentration in healthy older adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maten, E.; de Jonge, M.I.; de Groot, R.; van der Flier, M.; Langereis, J.D. A versatile assay to determine bacterial and host factors contributing to opsonophagocytotic killing in hirudin-anticoagulated whole blood. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, T.; Rodrigues, D.; Sarraguça, M.; Rocha, S.; Lima, J.L.F.C.; Ribeiro, D.; Fernandes, E.; Freitas, M. Optimization of Experimental Settings for the Assessment of Reactive Oxygen Species Production by Human Blood. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7198484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, B.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Davies, K.J.; Dennery, P.A.; Forman, H.J.; Grisham, M.B.; Mann, G.E.; Moore, K.; Roberts, L.J.; Ischiropoulos, H. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: Challenges and limitations. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, R.; Bourdet-Sicard, R.; Braun, D.; Calder, P.C.; Herz, U.; Lambert, C.; Lenoir-Wijnkoop, I.; Meheust, A.; Ouwehand, A.; Phothirath, P.; et al. Monitoring immune modulation by nutrition in the general population: Identifying and substantiating effects on human health. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, S1–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Active Ingredients | Units | Amount | RDA | UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamins | ||||

| Vitamin A | µg | 700 | 700 | 3000 |

| Vitamin D | IU | 400 | 600 | 4000 |

| Vitamin E | mg | 45 | 15 | 1000 |

| Vitamin B6 | mg | 6.6 | 1.3 | 100 |

| Folate | μg | 400 | 400 | 1000 |

| Vitamin B12 | μg | 9.6 | 2.4 | - |

| Vitamin C | mg | 1000 | 75 | 2000 |

| Trace Elements | ||||

| Iron | mg | 5 | 18 | 45 |

| Copper | mg | 0.9 | 0.9 | 10 |

| Zinc | mg | 10 | 8 | 40 |

| Selenium | µg | 110 | 55 | 400 |

| Other Ingredients | ||||

| Microcrystalline cellulose, magnesium stearate, hydroxylpropylmethylcellulose, hydroxypropylcellulose hypromellose, titanium dioxide, microcrystalline cellulose, iron oxide yellow, sodium croscarmellose, and talc. | ||||

| Arms | Assigned Interventions |

|---|---|

| Redoxon® VI Comparison is made within participants prior to and after treatment and to placebo arm; n = 21 | Supplement: two Redoxon® VI tablets, 1X/day, oral; 12 weeks |

| Placebo Comparison is made within participants prior to and after placebo treatment and to the Redoxon® VI supplementation arm; n = 21 | Supplement: two tablets of inert materials, 1X/day, oral; 12 weeks |

| Characteristics | Placebo (n = 21) | MVM (n = 21) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 ± 5 | 64 ± 5 | 0.78 |

| Gender (self-identified) | 1 | ||

| Female | 16 | 15 | |

| Male | 5 | 6 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | 0.28 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 129 ± 13 | 122 ± 10 | 0.07 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81 ± 7 | 77 ± 6 | 0.08 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 66 ± 8 | 65 ± 8 | 0.66 |

| Plasma Vitamin C (µmol/L) | 54 ± 20 | 52 ± 20 | 0.68 |

| Serum 25(OH) vitamin D (ng/mL) | 29 ± 8 | 31 ± 8 | 0.89 |

| Serum Zinc (µg/dL) | 79 ± 8 | 80 ± 11 | 0.34 |

| Whole Blood S. aureus Killing (slope) | +1671 ± 3856 | +298 ± 3129 | 0.25 |

| Neutrophil Phagocytosis (MFI) | 64 ± 18 | 58 ± 23 | 0.33 |

| Neutrophil ROS Production (MFI) | 1471 ± 460 | 1201 ± 495 | 0.07 |

| Placebo | Redoxon® VI | P-Differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 0 | Wk 12 | Wk 0 | Wk 12 | SEM | PL | RDX | Treat | |

| Micronutrients: | ||||||||

| Vitamin C | 51.5 | 51.9 | 48.9 | 108.6 | 6.2 | 0.94 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Zinc | 78.9 | 77.7 | 79.1 | 106.4 | 2.9 | 0.75 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 25(OH) Vit D | 27 | 25.2 | 29.9 | 30.5 | 1.8 | 0.12 | 0.61 | 0.15 |

| Immune Function: | ||||||||

| Whole Blood | ||||||||

| Killing | 1588 | 1292 | 234 | 1292 | 877 | 0.74 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| Neutrophils: | ||||||||

| Phagocytosis | 64.3 | 73.9 | 57.4 | 62.5 | 5.3 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 0.53 |

| ROS Prod. | 1546 | 1465 | 1250 | 1503 | 118 | 0.59 | 0.1 | 0.13 |

| Cytokine/Chemokine | Placebo | Redoxon® VI | P-Differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 0 | Wk 12 | Wk 0 | Wk 12 | SEM | Plac | Red | Treat | |

| Saliva: | ||||||||

| IgA | 1.44 | 1.5 | 1.95 | 1.34 | 0.26 | 0.8 | 0.02 | 0.047 |

| Serum: | ||||||||

| ICAM 1 | 26 | 29.2 | 39.3 | 39.3 | 19.6 | 0.21 | 0.99 | 0.39 |

| IL 1A | 2.68 | 2.69 | 3.33 | 1.87 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.17 |

| IL 12p70 | 66.8 | 65.4 | 32.9 | 32 | 30.6 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| Placebo | Redoxon® VI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | P-Diff | |

| Ill (% of participants) | 65% | 44% | 48% | 11% | 0.35 |

| Days ill | 6.43 | 1.71 | 2.29 | 0.77 | 0.02 |

| Days Level 1 severity | 2.55 | 0.76 | 1.43 | 0.56 | 0.24 |

| Days Level 2 severity | 1.80 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.03 |

| Days Level 3 severity | 1.80 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.04 |

| Days Level 4 severity | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Days ill x Severity | 13.95 | 4.63 | 3.57 | 1.25 | 0.008 |

| Number of Symptoms | 2.55 | 0.61 | 1.14 | 0.38 | 0.06 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fantacone, M.L.; Lowry, M.B.; Uesugi, S.L.; Michels, A.J.; Choi, J.; Leonard, S.W.; Gombart, S.K.; Gombart, J.S.; Bobe, G.; Gombart, A.F. The Effect of a Multivitamin and Mineral Supplement on Immune Function in Healthy Older Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082447

Fantacone ML, Lowry MB, Uesugi SL, Michels AJ, Choi J, Leonard SW, Gombart SK, Gombart JS, Bobe G, Gombart AF. The Effect of a Multivitamin and Mineral Supplement on Immune Function in Healthy Older Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2020; 12(8):2447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082447

Chicago/Turabian StyleFantacone, Mary L., Malcolm B. Lowry, Sandra L. Uesugi, Alexander J. Michels, Jaewoo Choi, Scott W. Leonard, Sean K. Gombart, Jeffrey S. Gombart, Gerd Bobe, and Adrian F. Gombart. 2020. "The Effect of a Multivitamin and Mineral Supplement on Immune Function in Healthy Older Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial" Nutrients 12, no. 8: 2447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082447

APA StyleFantacone, M. L., Lowry, M. B., Uesugi, S. L., Michels, A. J., Choi, J., Leonard, S. W., Gombart, S. K., Gombart, J. S., Bobe, G., & Gombart, A. F. (2020). The Effect of a Multivitamin and Mineral Supplement on Immune Function in Healthy Older Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 12(8), 2447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082447