Influence of Vitamin D on Islet Autoimmunity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 1 Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction: Pathogenesis and Natural History of Type 1 Diabetes

- Stage 1: Subjects exhibit islet autoimmunity, as evidenced by the persistent presence of at least two islet autoantibodies [autoantibodies directed against insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65), insulinoma-associated antigen 2 (IA-2), or zinc transporter-8 (ZnT8)], but remain normoglycemic and asymptomatic.

- Stage 2: Subjects maintain multiple islet autoantibody positivity and remain asymptomatic, but exhibit dysglycemia, as evidenced by impaired fasting glucose, an abnormal oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or HbA1c (glycated hemoglobin) ≥5.7% [13].

- Stage 4: Established/long-term disease [11].

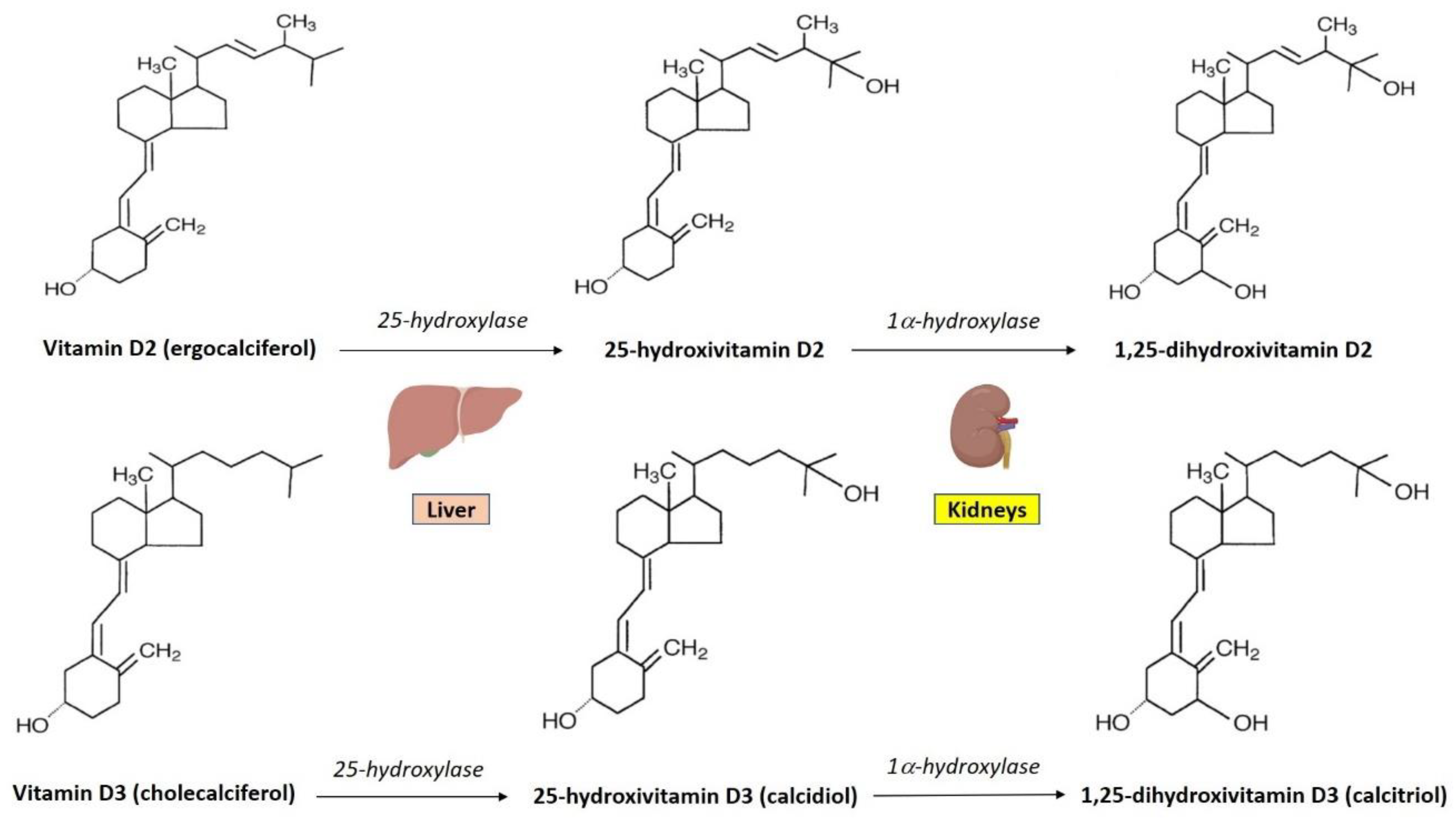

2. Chemical and Pharmacokinetic Properties of Vitamin D

3. Vitamin D Synthesis and Metabolism

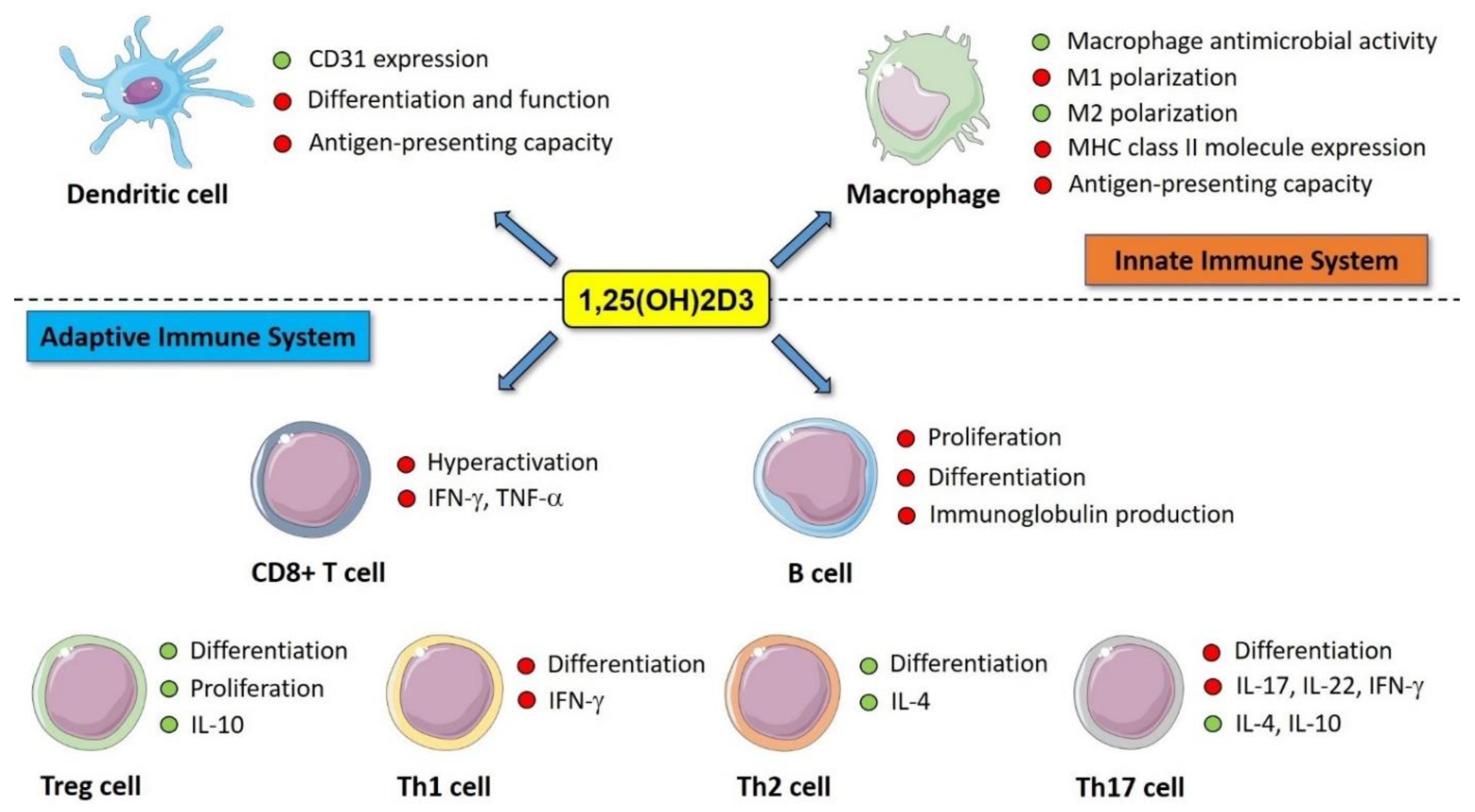

4. Immunomodulatory Effects of Vitamin D

5. Role of Vitamin D in Islet Autoimmunity, Inflammation, and Beta-Cell Function: Evidence from Pre-Clinical Studies

6. The Role of Polymorphisms of Vitamin D Metabolism Genes in T1D

7. Role of Vitamin D Status and Vitamin D Supplementation in T1D: Epidemiologic Evidence

8. Vitamin D Supplementation as an Immunomodulatory Therapy for T1D: Clinical Evidence

9. Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3)

10. Cholecalciferol in Combination with Anti-Inflammatory or Anti-Hyperglycemic Agents

11. Ergocalciferol (Vitamin D2)

12. Calcidiol (25-Hydroxyvitamin D3)

13. Calcitriol (1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3)

14. Alfacalcidol (1α-hydroxycholecalciferol)

15. Discussion

16. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisenbarth, G.S. Type I diabetes mellitus. A chronic autoimmune disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 314, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, M.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Michels, A.W. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2014, 383, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulis, A.K.; McGill, M.; Farquharson, M.A. Insulitis in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus in man--macrophages, lymphocytes, and interferon-gamma containing cells. J. Pathol. 1991, 165, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, D.; Vence, L.; Benoist, C. beta-Cell death during progression to diabetes. Nature 2001, 414, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.S.; von Herrath, M. CD4 T cell differentiation in type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2016, 183, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honkanen, J.; Nieminen, J.K.; Gao, R.; Luopajarvi, K.; Salo, H.M.; Ilonen, J.; Vaarala, O. IL-17 immunity in human type 1 diabetes. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 1959–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, S.; Dayan, C.M.; Bishop, A.; Roep, B.O.; Peakman, M.; Tree, T.I. Defective suppressor function in CD4(+)CD25(+) T-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2005, 54, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusko, T.M.; Wasserfall, C.H.; Clare-Salzler, M.J.; Schatz, D.A.; Atkinson, M.A. Functional defects and the influence of age on the frequency of CD4+ CD25+ T-cells in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseda, F.; Imagawa, A.; Murase-Mishiba, Y.; Terasaki, J.; Hanafusa, T. CD4⁺ CD45RA⁻ FoxP3high activated regulatory T cells are functionally impaired and related to residual insulin-secreting capacity in patients with type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013, 173, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, R.A.; Dunne, J.L.; Atkinson, M.A.; Chiang, J.L.; Dabelea, D.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Ratner, R.E. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: A scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1964–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, C.J.; Speake, C.; Krischer, J.; Buckner, J.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Schatz, D.A.; Atkinson, M.A. Strength in Numbers: Opportunities for Enhancing the Development of Effective Treatments for Type 1 Diabetes-The TrialNet Experience. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenbaum, C.; van Buecken, D.; Lord, S. Disease-Modifying Therapies in Type 1 Diabetes: A Look into the Future of Diabetes Practice. Drugs 2019, 79, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosenko, J.M.; Skyler, J.S.; Palmer, J.P.; Krischer, J.P.; Yu, L.; Mahon, J.; Eisenbarth, G. The prediction of type 1 diabetes by multiple autoantibody levels and their incorporation into an autoantibody risk score in relatives of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2615–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcox, A.; Gillespie, K.M. Histology of Type 1 Diabetes Pancreas. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1433, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, M.A.; Maclaren, N.K. The pathogenesis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabbah, E.; Savola, K.; Ebeling, T.; Kulmala, P.; Vähäsalo, P.; Ilonen, J.; Knip, M. Genetic, autoimmune, and clinical characteristics of childhood-and adult-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maahs, D.M.; West, N.A.; Lawrence, J.M.; Mayer-Davis, E.J. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 39, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonolleda, M.; Murillo, M.; Vázquez, F.; Bel, J.; Vives-Pi, M. Remission Phase in Paediatric Type 1 Diabetes: New Understanding and Emerging Biomarkers. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2017, 88, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkey, J.H.; Bingley, P.J.; Sawtell, P.A.; Dunger, D.B.; Gale, E.A. Presentation and progress of childhood diabetes mellitus: A prospective population-based study. The Bart’s-Oxford Study Group. Diabetologia 1994, 37, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallensteen, M.; Dahlquist, G.; Persson, B.; Landin-Olsson, M.; Lernmark, A.; Sundkvist, G.; Thalme, B. Factors influencing the magnitude, duration, and rate of fall of B-cell function in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic children followed for two years from their clinical diagnosis. Diabetologia 1988, 31, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rasoul, M.; Habib, H.; Al-Khouly, M. The honeymoon phase in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: Frequency, duration, and influential factors. Pediatr. Diabetes 2006, 7, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokołowska, M.; Chobot, A.; Jarosz-Chobot, P. The honeymoon phase—what we know today about the factors that can modulate the remission period in type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 22, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, H.; Gottlieb, P. The honeymoon phase: Intersection of metabolism and immunology. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2009, 16, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschou, S.A.; Papadopoulou-Marketou, N. Chrousos GP, Kanaka-Gantenbein, C. On type 1 diabetes mellitus pathogenesis. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, R38–R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frongia, O.; Pascutto, C.; Sechi, G.M.; Soro, M.; Angioi, R.M. Genetic and environmental factors for type 1 diabetes: Data from the province of Oristano, Sardinia, Italy. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1846–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pociot, F.; Lernmark, Å. Genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2016, 387, 2331–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewers, M.; Ludvigsson, J. Environmental risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2016, 387, 2340–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knip, M.; Simell, O. Environmental triggers of type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a007690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotta, F.; Censini, S.; van Halteren, A.G.; Marselli, L.; Masini, M.; Dionisi, S.; Censini, S. Coxsackie B4 virus infection of beta cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5115–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.J.; Willcox, A.; Bone, A.J.; Foulis, A.K.; Morgan, N.G. The prevalence of enteroviral capsid protein vp1 immunostaining in pancreatic islets in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.T.; Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Giongo, A.; Gano, K.A.; Crabb, D.B.; Mukherjee, N.; Hyöty, H. Gut microbiome metagenomics analysis suggests a functional model for the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederiksen, B.; Kroehl, M.; Lamb, M.M.; Seifert, J.; Barriga, K.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Norris, J.M. Infant exposures and development of type 1 diabetes mellitus: The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, V.S.; Vanleeuwen, J.A.; Taylor, J.; Somers, G.S.; McKinney, P.A.; Van Til, L. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and components in drinking water and diet: A population-based, case-control study in Prince Edward Island, Canada. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2010, 29, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parslow, R.C.; McKinney, P.A.; Law, G.R.; Staines, A.; Williams, R.; Bodansky, H.J. Incidence of childhood diabetes mellitus in Yorkshire, northern England, is associated with nitrate in drinking water: An ecological analysis. Diabetologia 1997, 40, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlquist, G.G.; Blom, L.G.; Persson, L.A.; Sandström, A.I.; Wall, S.G. Dietary factors and the risk of developing insulin dependent diabetes in childhood. BMJ 1990, 300, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostraba, J.N.; Gay, E.C.; Rewers, M.; Hamman, R.F. Nitrate levels in community drinking waters and risk of IDDM. An ecological analysis. Diabetes Care 1992, 15, 1505–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, C.C.; Dahlquist, G.G.; Gyürüs, E.; Green, A.; Soltész, G.; Group, E.S. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005–2020: A multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet 2009, 373, 2027–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehik, K.; Dabelea, D. The changing epidemiology of type 1 diabetes: Why is it going through the roof? Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2011, 27, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S.Y.; Gordon, C.M. Vitamin D deficiency in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, impact and treatment. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2008, 9, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootton, A.M. Improving the measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2005, 26, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carrelli, A.; Bucovsky, M.; Horst, R.; Cremers, S.; Zhang, C.; Bessler, M.; Stein, E.M. Vitamin D Storage in Adipose Tissue of Obese and Normal Weight Women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengist, A.; Perkin, O.; Gonzalez, J.T.; Betts, J.A.; Hewison, M.; Manolopoulos, K.N.; Thompson, D. Mobilising vitamin D from adipose tissue: The potential impact of exercise. Nutr. Bull. 2019, 44, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. The use and interpretation of assays for vitamin D and its metabolites. J. Nutr. 1990, 120 (Suppl. 11), 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 582S–586S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.R.; Pilbeam, C.; Hanafin, N.; Holick, M.F. An evaluation of the relative contributions of exposure to sunlight and of diet to the circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in an elderly nursing home population in Boston. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 51, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.; Walther, B. Natural vitamin D content in animal products. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakos, S.; Dhawan, P.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D: Metabolism, Molecular Mechanism of Action, and Pleiotropic Effects. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 365–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Prosser, D.E.; Kaufmann, M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D-24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1): Its important role in the degradation of vitamin D. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 523, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; DeLuca, H.F. Where is the vitamin D receptor? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 523, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio, M.; Infante, M.; Calanchini, M.; Mammi, C.; Fabbri, A. Vitamin D: Not just the bone. Evidence for beneficial pleiotropic extraskeletal effects. Eat. Weight Disord. 2017, 22, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio, M.; Mammi, C.; Rosano, G.M. Vitamin D: A novel player in endothelial function and dysfunction. Arch. Med. Sci. 2012, 8, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, D.; Idolazzi, L.; Fassio, A. Vitamin D: Not just bone, but also immunity. Minerva Med. 2016, 107, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- White, J.H. Vitamin D metabolism and signaling in the immune system. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2012, 13, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prietl, B.; Treiber, G.; Pieber, T.R.; Amrein, K. Vitamin D and immune function. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2502–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbergh, L.; Decallonne, B.; Valckx, D.; Verstuyf, A.; Depovere, J.; Laureys, J.; Mathieu, C. Identification and immune regulation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-alpha-hydroxylase in murine macrophages. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2000, 120, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffels, K.; Overbergh, L.; Giulietti, A.; Verlinden, L.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Immune regulation of 25-hydroxyvitamin-D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in human monocytes. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbergh, L.; Stoffels, K.; Waer, M.; Verstuyf, A.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Immune regulation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1alpha-hydroxylase in human monocytic THP1 cells: Mechanisms of interferon-gamma-mediated induction. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.K.; van den Berg, P.R.; Long, M.D.; Vreugdenhil, A.; Grieshober, L.; Ochs-Balcom, H.M.; Campbell, M.J. Integration of VDR genome wide binding and GWAS genetic variation data reveals co-occurrence of VDR and NF-κB binding that is linked to immune phenotypes. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillon, R.; Carmeliet, G.; Verlinden, L.; van Etten, E.; Verstuyf, A.; Luderer, H.F.; Demay, M. Vitamin D and human health: Lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 726–776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.S.; Madsen, M.W.; Lukas, J.; Binderup, L.; Bartek, J. Inhibitory effects of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) on the G(1)-S phase-controlling machinery. Mol. Endocrinol. 2001, 15, 1370–1380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Piemonti, L.; Monti, P.; Sironi, M.; Fraticelli, P.; Leone, B.E.; Dal Cin, E.; di Carlo, V. Vitamin D3 affects differentiation, maturation, and function of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 4443–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, G.; Adorini, L. 1 Alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 2405–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauzzi, M.C.; Purificato, C.; Donato, K.; Jin, Y.; Wang, L.; Daniel, K.C.; Gessani, S. Suppressive effect of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on type I IFN-mediated monocyte differentiation into dendritic cells: Impairment of functional activities and chemotaxis. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, G.B.; Vanherwegen, A.S.; Eelen, G.; Gutiérrez, A.C.F.; van Lommel, L.; Marchal, K.; Schuit, F. Vitamin D3 Induces Tolerance in Human Dendritic Cells by Activation of Intracellular Metabolic Pathways. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, G.B.; van Etten, E.; Verstuyf, A.; Waer, M.; Overbergh, L. Gysemans, C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 alters murine dendritic cell behaviour in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2011, 27, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saul, L.; Mair, I.; Ivens, A.; Brown, P.; Samuel, K.; Campbell, J.D.M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Restrains CD4+ T Cell Priming Ability of CD11c+ Dendritic Cells by Upregulating Expression of CD31. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, G.; Selvaraj, P.; Jawahar, M.S.; Banurekha, V.V. Narayanan. P.R. Effect of vitamin D3 on phagocytic potential of macrophages with live Mycobacterium tuberculosis and lymphoproliferative response in pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Clin. Immunol. 2004, 24, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado Diago, C.A.; García-Unzueta, M.T.; Fariñas, M.C.; Amado, J.A. Calcitriol-modulated human antibiotics: New pathophysiological aspects of vitamin D. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2016, 63, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korf, H.; Wenes, M.; Stijlemans, B.; Takiishi, T.; Robert, S.; Miani, M.; Mathieu, C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 curtails the inflammatory and T cell stimulatory capacity of macrophages through an IL-10-dependent mechanism. Immunobiology 2012, 217, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Guo, Y.; Song, Z.; Liu, B. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D₃ Promotes High Glucose-Induced M1 Macrophage Switching to M2 via the VDR-PPARγ Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 157834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Leung, D.Y.; Richers, B.N.; Liu, Y.; Remigio, L.K.; Riches, D.W.; Goleva, E. Vitamin D inhibits monocyte/macrophage proinflammatory cytokine production by targeting MAPK phosphatase-1. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Heilmann, C.; Poulsen, L.K.; Barington, T.; Bendtzen, K. The role of monocytes and T cells in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 mediated inhibition of B cell function in vitro. Immunopharmacology 1991, 21, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, G.; Anton, K.; Henz, B.M.; Worm, M. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits anti-CD40 plus IL-4-mediated IgE production in vitro. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002, 32, 3395–3404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Sims, G.P.; Chen, X.X.; Gu, Y.Y.; Lipsky, P.E. Modulatory effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human B cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1634–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, L.E.; Burke, F.; Mura, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qureshi, O.S.; Hewison, M.; Sansom, D.M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and IL-2 combine to inhibit T cell production of inflammatory cytokines and promote development of regulatory T cells expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 5458–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbergh, L.; Decallonne, B.; Waer, M.; Rutgeerts, O.; Valckx, D.; Casteels, K.M.; Mathieu, C. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces an autoantigen-specific T-helper 1/T-helper 2 immune shift in NOD mice immunized with GAD65 (p524-543). Diabetes 2000, 49, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, A.; Barrat, F.J.; Crain, C.; Heath, V.L.; Savelkoul, H.F.; O’Garra, A. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin d3 has a direct effect on naive CD4(+) T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 4974–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Lieben, L.; Mathieu, C.; Verstuyf, A.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D action: Lessons from VDR and Cyp27b1 null mice. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2013, 10 (Suppl. 2), 354–366. [Google Scholar]

- Lysandropoulos, A.P.; Jaquiéry, E.; Jilek, S.; Pantaleo, G.; Schluep, M.; Du Pasquier, R.A. Vitamin D has a direct immunomodulatory effect on CD8+ T cells of patients with early multiple sclerosis and healthy control subjects. J. Neuroimmunol. 2011, 233, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankers, W.; Colin, E.M.; van Hamburg, J.P.; Lubberts, E. Vitamin D in Autoimmunity: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ambrosio, D.; Cippitelli, M.; Cocciolo, M.G.; Mazzeo, D.; di Lucia, P.; Lang, R.; Panina-Bordignon, P. Inhibition of IL-12 production by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Involvement of NF-kappaB downregulation in transcriptional repression of the p40 gene. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Reddy, G.S.; Kobayashi, T.; Okano, T.; Park, J.; Sharma, S. Nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) as a molecular target for 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated effects. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reichel, H.; Koeffler, H.P.; Tobler, A.; Norman, A.W. 1 alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits gamma-interferon synthesis by normal human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 3385–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cippitelli, M.; Santoni, A. Vitamin D3: A transcriptional modulator of the interferon-gamma gene. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998, 28, 3017–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Chung, Y.; Dong, C. Vitamin D suppresses Th17 cytokine production by inducing C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 38751–38755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachapati, K.; Adams, D.; Bednar, K.; Ridgway, W.M. The non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse as a model of human type 1 diabetes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 933, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Giulietti, A.; Gysemans, C.; Stoffels, K.; van Etten, E.; Decallonne, B.; Overbergh, L.; Mathieu, C. Vitamin D deficiency in early life accelerates Type 1 diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Diabetologia 2004, 47, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C.; Waer, M.; Laureys, J.; Rutgeerts, O.; Bouillon, R. Prevention of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3. Diabetologia 1994, 37, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C.; Waer, M.; Casteels, K.; Laureys, J.; Bouillon, R. Prevention of type I diabetes in NOD mice by nonhypercalcemic doses of a new structural analog of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, KH1060. Endocrinology 1995, 136, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C.; Laureys, J.; Sobis, H.; Vandeputte, M.; Waer, M.; Bouillon, R. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 prevents insulitis in NOD mice. Diabetes 1992, 41, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casteels, K.M.; Mathieu, C.; Waer, M.; Valckx, D.; Overbergh, L.; Laureys, J.M.; Bouillon, R. Prevention of type I diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice by late intervention with nonhypercalcemic analogs of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in combination with a short induction course of cyclosporin A. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregori, S.; Giarratana, N.; Smiroldo, S.; Uskokovic, M.; Adorini, L. A 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) analog enhances regulatory T-cells and arrests autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casteels, K.; Waer, M.; Bouillon, R.; Depovere, J.; Valckx, D.; Laureys, J.; Mathieu, C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 restores sensitivity to cyclophosphamide-induced apoptosis in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice and protects against diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998, 112, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casteels, K.M.; Gysemans, C.A.; Waer, M.; Bouillon, R.; Laureys, J.M.; Depovere, J.; Mathieu, C. Sex difference in resistance to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in NOD mice: Treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 restores defect. Diabetes 1998, 47, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Halteren, A.G.; van Etten, E.; de Jong, E.C.; Bouillon, R.; Roep, B.O.; Mathieu, C. Redirection of human autoreactive T-cells Upon interaction with dendritic cells modulated by TX527, an analog of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D(3). Diabetes 2002, 51, 2119–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Halteren, A.G.; Tysma, O.M.; van Etten, E.; Mathieu, C.; Roep, B.O. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 or analogue treated dendritic cells modulate human autoreactive T cells via the selective induction of apoptosis. J. Autoimmun. 2004, 23, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiishi, T.; Ding, L.; Baeke, F.; Spagnuolo, I.; Sebastiani, G.; Laureys, J.; Gysemans, C.A. Dietary supplementation with high doses of regular vitamin D3 safely reduces diabetes incidence in NOD mice when given early and long term. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2026–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizirik, D.L.; Colli, M.L.; Ortis, F. The role of inflammation in insulitis and beta-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, S.; Buschard, K.; Bendtzen, K. Effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and the analogues MC903 and KH1060 on interleukin-1 beta-induced inhibition of rat pancreatic islet beta-cell function in vitro. Immunol. Lett. 1994, 41, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.J.; Kuttler, B.; Mathieu, C.; Bouillon, R. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces MHC antigen expression on pancreatic beta-cells in vitro. Transplant. Proc. 1997, 29, 2156–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riachy, R.; Vandewalle, B.; Kerr Conte, J.; Moerman, E.; Sacchetti, P.; Lukowiak, B. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 protects RINm5F and human islet cells against cytokine-induced apoptosis: Implication of the antiapoptotic protein A20. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 4809–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riachy, R.; Vandewalle, B.; Belaich, S.; Kerr-Conte, J.; Gmyr, V.; Zerimech, F.; Pattou, F. Beneficial effect of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 on cytokine-treated human pancreatic islets. J. Endocrinol. 2001, 169, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Yoshihara, E.; He, N.; Hah, N.; Fan, W.; Pinto, A.F.M.; Dai, Y. Vitamin D Switches BAF Complexes to Protect β Cells. Cell 2018, 173, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Ashraf, A. Role of vitamin d in insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity for glucose homeostasis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 2010, 351385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, A.W.; Frankel, J.B.; Heldt, A.M.; Grodsky, G.M. Vitamin D deficiency inhibits pancreatic secretion of insulin. Science 1980, 209, 823–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, R.; Markovic, D.; Hills, C.E.; Hughes, S.V.; Chan, S.L.; Squires, P.E. Expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in pancreatic islets. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 89–90, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Grande, J.P.; Roche, P.C.; Kumar, R. Immunohistochemical localization of the 1,25(OH)2D3 receptor and calbindin D28k in human and rat pancreas. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267 Pt 1, E356–E360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestro, B.; Dávila, N.; Carranza, M.C.; Calle, C. Identification of a Vitamin D response element in the human insulin receptor gene promoter. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 84, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitz, U.; Weber, K.; Soegiarto, D.W.; Wolf, E.; Balling, R.; Erben, R.G. Impaired insulin secretory capacity in mice lacking a functional vitamin D receptor. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourlon, P.M.; Billaudel, B.; Faure-Dussert, A. Influence of vitamin D3 deficiency and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 on de novo insulin biosynthesis in the islets of the rat endocrine pancreas. J. Endocrinol. 1999, 160, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade, C.; Norman, A.W. Vitamin D3 improves impaired glucose tolerance and insulin secretion in the vitamin D-deficient rat in vivo. Endocrinology 1986, 119, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.A.; Stumpf, W.E.; Sar, M. Effect of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 on insulin secretion. Diabetes 1981, 30, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyomba, B.L.; Bouillon, R.; de Moor, P. Influence of vitamin D status on insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in the rabbit. Endocrinology 1984, 115, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Lopez, E.; Brück, P.; Jansen, T.; Herwig, J.; Badenhoop, K. CYP2R1 (vitamin D 25-hydroxylase) gene is associated with susceptibility to type 1 diabetes and vitamin D levels in Germans. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2007, 23, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.D.; Smyth, D.J.; Walker, N.M.; Stevens, H.; Burren, O.S.; Wallace, C.; Spector, T.D. Inherited variation in vitamin D genes is associated with predisposition to autoimmune disease type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60, 1624–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.; Cooper, J.D.; Zeitels, L.; Smyth, D.J.; Yang, J.H.; Walker, N.M.; Nejentsev, S. Association of the vitamin D metabolism gene CYP27B1 with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2616–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.G.; Mohamed, R.H.; Alghobashy, A.A. Synergism of CYP2R1 and CYP27B1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 1 diabetes in Egyptian children. Cell. Immunol. 2012, 279, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, S.U.; Mortensen, H.B.; Carstensen, B.; Fenger, M.; Thuesen, B.H.; Husemoen, L.; Svensson, J. No association between type 1 diabetes and genetic variation in vitamin D metabolism genes: A Danish study. Pediatr. Diabetes 2014, 15, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongagna, J.C.; Kaltenbacher, M.C.; Sapin, R.; Pinget, M.; Belcourt, A. The HLA-DQB alleles and amino acid variants of the vitamin D-binding protein in diabetic patients in Alsace. Clin Biochem. 2001, 34, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongagna, J.C.; Pinget, M.; Belcourt, A. Vitamin D-binding protein gene polymorphism association with IA-2 autoantibodies in type 1 diabetes. Clin Biochem. 2005, 38, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaud, J.; Constans, J. Affinity differences for vitamin D metabolites associated with the genetic isoforms of the human serum carrier protein (DBP). Hum Genet. 1993, 92, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanton, D.; Han, Z.; Bierschenk, L.; Linga-Reddy, M.V.; Wang, H.; Clare-Salzler, M.; Wasserfall, C. Reduced serum vitamin D-binding protein levels are associated with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2566–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, G.; Mårild, K.; Dahl, S.R.; Lund-Blix, N.A.; Viken, M.K.; Lie, B.A.; Størdal, K. Maternal and Newborn Vitamin D-Binding Protein, Vitamin D Levels, Vitamin D Receptor Genotype, and Childhood Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, K.; Zhao, Z.; Toda, K.; Yip, L.; Fuhlbrigge, R.; Miao, D.; Yu, L. Expression-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Links Vitamin D-Binding Protein with Autoantigenicity in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, J.M.; Lee, H.S.; Frederiksen, B.; Erlund, I.; Uusitalo, U.; Yang, J. Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration and Risk of Islet Autoimmunity. Diabetes 2018, 67, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Allah, S.H.; Pasha, H.F.; Hagrass, H.A.; Alghobashy, A.A. Vitamin D status and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 1 diabetes in Egyptian children. Gene 2014, 536, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.J.; Lei, H.H.; Yeh, J.I.; Chiu, K.C.; Lee, K.C.; Chen, M.C. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms influence susceptibility to type 1 diabetes mellitus in the Taiwanese population. Clin. Endocrinol. 2000, 52, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, N.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.; He, W.; Yang, T. Associations between two polymorphisms (FokI and BsmI) of vitamin D receptor gene and type 1 diabetes mellitus in Asian population: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, O.A.; Goksen, D.; Ozpinar, A.; Serdar, M.; Onay, H. Association of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and type 1 diabetes susceptibility in children: A meta-analysis. Endocr. Connect. 2017, 6, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhtar, M.; Batool, A.; Wajid, A.; Qayyum, I. Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphisms Influence T1D Susceptibility among Pakistanis. Int. J. Genom. 2017, 2017, 4171254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R.; Fawzy, I.; Mohsen, I.; Settin, A. Evaluation of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms (Fok-I and Bsm-I) in T1DM Saudi children. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2018, 32, e22397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibian, N.; Amoli, M.M.; Abbasi, F.; Rabbani, A.; Alipour, A.; Sayarifard, F.; Setoodeh, A. Role of vitamin D and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms on residual beta cell function in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 71, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W.P.; Henneberg, M. Type 1 diabetes prevalence increasing globally and regionally: The role of natural selection and life expectancy at birth. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2016, 4, e000161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, D.J.; Talton, J.; Dabelea, D.; Divers, J.; Imperatore, G.; Lawrence, J.M. Prevalence of diabetes in U.S. youth in 2009: The SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Dabelea, D.; Divers, J.; Isom, S.; Dolan, L.; Pihoker, C. Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002–2012. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, M.; Viik-Kajander, M.; Moltchanova, E.; Libman, I.; LaPorte, R.; Tuomilehto, J. Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes Mondiale (DiaMond) Project Group. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, M.; Jäntti, V.; Muntoni, S.; Stabilini, M.; Stabilini, L.; Tuomilehto, J. Comparison of the seasonal pattern in the clinical onset of IDDM in Finland and Sardinia. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostman, J.; Lönnberg, G.; Arnqvist, H.J.; Blohmé, G.; Bolinder, J.; Ekbom Schnell, A. Gender differences and temporal variation in the incidence of type 1 diabetes: Results of 8012 cases in the nationwide Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden 1983–2002. J. Intern. Med. 2008, 263, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorham, E.D.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Highfill-McRoy, R.M.; Mohr, S.B.; Garland, C.F.; Garland, F.C. Incidence of insulin-requiring diabetes in the US military. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2087–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, S.B.; Garland, C.F.; Gorham, E.D.; Garland, F.C. The association between ultraviolet B irradiance, vitamin D status and incidence rates of type 1 diabetes in 51 regions worldwide. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, S.B.; Garland, F.C.; Garland, C.F.; Gorham, E.D.; Ricordi, C. Is there a role of vitamin D deficiency in type 1 diabetes of children? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzilli, P.; Manfrini, S.; Crinò, A.; Picardi, A.; Leomanni, C.; Cherubini, V. Low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Horm. Metab. Res. 2005, 37, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littorin, B.; Blom, P.; Schölin, A.; Arnqvist, H.J.; Blohmé, G.; Bolinder, J. Lower levels of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D among young adults at diagnosis of autoimmune type 1 diabetes compared with control subjects: Results from the nationwide Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden (DISS). Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2847–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkar, V.V.; Devidayal Verma, S.; Bhalla, A.K. Low levels of vitamin D in North Indian children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2010, 11, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zubeidi, H.; Leon-Chi, L.; Newfield, R.S. Low vitamin D level in pediatric patients with new onset type 1 diabetes is common, especially if in ketoacidosis. Pediatr. Diabetes 2016, 17, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daga, R.A.; Laway, B.A.; Shah, Z.A.; Mir, S.A.; Kotwal, S.K.; Zargar, A.H. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among newly diagnosed youth-onset diabetes mellitus in north India. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2012, 56, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, R.M.; Portelli, S.L.; Hung, B.S.; Cleghorn, G.J.; McMahon, S.K.; Batch, J.A. Serum vitamin D levels are lower in Australian children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes than in children without diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2013, 14, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Al-Attas, O.S.; Alokail, M.S.; Alkharfy, K.M.; Yakout, S.M.; Aljohani, N.J.; Alharbi, M. Lower vitamin D status is more common among Saudi adults with diabetes mellitus type 1 than in non-diabetics. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, G.; Genoni, A.; Puggioni, A.; Saba, A.; Gallo, D.; Randazzo, E.; Toniolo, A. Vitamin D status, enterovirus infection, and type 1 diabetes in Italian children/adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadario, F.; Prodam, F.; Savastio, S.; Monzani, A.; Balafrej, A.; Bellomo, G. Vitamin D status and type 1 diabetes in children: Evaluation according to latitude and skin color. Minerva Pediatr. 2015, 67, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rasoul, M.A.; Al-Mahdi, M.; Al-Kandari, H.; Dhaunsi, G.S.; Haider, M.Z. Low serum vitamin-D status is associated with high prevalence and early onset of type-1 diabetes mellitus in Kuwaiti children. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raab, J.; Giannopoulou, E.Z.; Schneider, S.; Warncke, K.; Krasmann, M.; Winkler, C.; Ziegler, A.G. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pre-type 1 diabetes and its association with disease progression. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadario, F.; Savastio, S.; Pagliardini, V.; Bagnati, M.; Vidali, M.; Cerutti, F. Vitamin D levels at birth and risk of type 1 diabetes in childhood: A case-control study. Acta Diabetol. 2015, 52, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkinen, M.; Mykkänen, J.; Koskinen, M.; Simell, V.; Veijola, R.; Hyöty, H. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations in Children Progressing to Autoimmunity and Clinical Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorham, E.D.; Garland, C.F.; Burgi, A.A.; Mohr, S.B.; Zeng, K.; Hofflich, H. Lower prediagnostic serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration is associated with higher risk of insulin-requiring diabetes: A nested case-control study. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 3224–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munger, K.L.; Levin, L.I.; Massa, J.; Horst, R.; Orban, T.; Ascherio, A. Preclinical serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of type 1 diabetes in a cohort of US military personnel. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronczak, C.M.; Barón, A.E.; Chase, H.P.; Ross, C.; Brady, H.L.; Hoffman, M.; Norris, J.M. In utero dietary exposures and risk of islet autoimmunity in children. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 3237–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stene, L.C.; Ulriksen, J.; Magnus, P.; Joner, G. Use of cod liver oil during pregnancy associated with lower risk of Type I diabetes in the offspring. Diabetologia 2000, 43, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, I.M.; Joner, G.; Jenum, P.A.; Eskild, A.; Torjesen, P.A.; Stene, L.C. Maternal serum levels of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of type 1 diabetes in the offspring. Diabetes 2012, 61, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, M.E.; Reinert, L.; Kinnunen, L.; Harjutsalo, V.; Koskela, P.; Surcel, H.M. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level during early pregnancy and type 1 diabetes risk in the offspring. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marjamäki, L.; Niinistö, S.; Kenward, M.G.; Uusitalo, L.; Uusitalo, U.; Ovaskainen, M.L. Maternal intake of vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of advanced beta cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in offspring. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1599–15607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brekke, H.K.; Ludvigsson, J. Vitamin D supplementation and diabetes-related autoimmunity in the ABIS study. Pediatr. Diabetes 2007, 8, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granfors, M.; Augustin, H.; Ludvigsson, J.; Brekke, H.K. No association between use of multivitamin supplement containing vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of Type 1 Diabetes in the child. Pediatr. Diabetes 2016, 17, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.Y.; Zhang, W.G.; Chen, J.J.; Zhang, Z.L.; Han, S.F.; Qin, L.Q. Vitamin D intake and risk of type 1 diabetes: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3551–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvis, K.; Aronsson, C.A.; Liu, X.; Uusitalo, U.; Yang, J.; Tamura, R. Maternal dietary supplement use and development of islet autoimmunity in the offspring: TEDDY study. Pediatr. Diabetes 2019, 20, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyppönen, E.; Läärä, E.; Reunanen, A.; Järvelin, M.R.; Virtanen, S.M. Intake of vitamin D and risk of type 1 diabetes: A birth-cohort study. Lancet 2001, 358, 1500–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EURODIAB Substudy 2 Study Group. Vitamin D supplement in early childhood and risk for Type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1999, 42, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipitis, C.S.; Akobeng, A.K. Vitamin D supplementation in early childhood and risk of type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008, 93, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stene, L.C.; Joner, G.; Group NCDS. Use of cod liver oil during the first year of life is associated with lower risk of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: A large, population-based, case-control study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, A.K.; Hollander, G.A.; McMichael, A. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20143085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfvenborg, J.E.; Andersson, T.; Carlsson, P.O.; Dorkhan, M.; Groop, L.; Martinell, M. Fatty fish consumption and risk of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Nutr. Diabetes 2014, 4, e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbay, M.A.; Sato, M.N.; Finazzo, C.; Duarte, A.J.; Dib, S.A. Effect of cholecalciferol as adjunctive therapy with insulin on protective immunologic profile and decline of residual β-cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanou, D.; Penna-Martinez, M.; Filmann, N.; Chung, T.L.; Moran-Auth, Y.; Wehrle, J.; Badenhoop, K. T-lymphocyte and glycemic status after vitamin D treatment in type 1 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial with sequential crossover. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2017, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiber, G.; Prietl, B.; Fröhlich-Reiterer, E.; Lechner, E.; Ribitsch, A.; Fritsch, M. Cholecalciferol supplementation improves suppressive capacity of regulatory T-cells in young patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus—A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 161, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Dayal, D.; Sachdeva, N.; Attri, S.V. Effect of 6-months’ vitamin D supplementation on residual beta cell function in children with type 1 diabetes: A case control interventional study. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 29, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, D.; Pintus, D.; Burnside, G.; Ghatak, A.; Mehta, F.; Paul, P. Treating vitamin D deficiency in children with type I diabetes could improve their glycaemic control. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panjiyar, R.P.; Dayal, D.; Attri, S.V.; Sachdeva, N.; Sharma, R.; Bhalla, A.K. [Sustained serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations for one year with cholecalciferol supplementation improves glycaemic control and slows the decline of residual β cell function in children with type 1 diabetes]. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2018, 2018, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, E.M.; Mittelman, S.; Pitukcheewanont, P.; Azen, C.G.; Monzavi, R. Effects of vitamin D repletion on glycemic control and inflammatory cytokines in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2016, 17, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Biswal, N.; Bethou, A.; Rajappa, M.; Kumar, S.; Vinayagam, V. Does Vitamin D Supplementation Improve Glycaemic Control In Children With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus?-A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, SC15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perchard, R.; Magee, L.; Whatmore, A.; Ivison, F.; Murray, P.; Stevens, A. A pilot interventional study to evaluate the impact of cholecalciferol treatment on HbA1c in type 1 diabetes (T1D). Endocr. Connect. 2017, 6, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, M.D.; Binongo, J.N.; Watson, D.; Alvarez, J.A.; Lodin, D.; Ziegler, T.R. The effect of a single, large bolus of vitamin D in healthy adults over the winter and following year: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Endres, S.; Ghorbani, R.; Kelley, V.E.; Georgilis, K.; Lonnemann, G.; van der Meer, J.W. The effect of dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on the synthesis of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor by mononuclear cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 320, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spite, M.; Clària, J.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvins, specialized proresolving lipid mediators, and their potential roles in metabolic diseases. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 2014, 510, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002, 56, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. An Increase in the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio Increases the Risk for Obesity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagohashi, Y.; Otani, H. Diet with a low n-6/n-3 essential fatty acid ratio when started immediately after the onset of overt diabetes prolongs survival of type 1 diabetes model NOD mice. Congenit. Anom. 2010, 50, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinistö, S.; Takkinen, H.M.; Erlund, I.; Ahonen, S.; Toppari, J.; Ilonen, J. Fatty acid status in infancy is associated with the risk of type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T. ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids ameliorate type 1 diabetes and autoimmunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1757–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, M.J.; Wasserfall, C.H.; Hulme, M.A.; Cintron, M.; Brusko, T.M.; McGrail, K.M. Autologous umbilical cord blood infusion followed by oral docosahexaenoic acid and vitamin D supplementation for C-peptide preservation in children with Type 1 diabetes. Biol. Blood Marrow. Transplant. 2013, 19, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baidal, D.A.; Ricordi, C.; Garcia-Contreras, M.; Sonnino, A.; Fabbri, A. Combination high-dose omega-3 fatty acids and high-dose cholecalciferol in new onset type 1 diabetes: A potential role in preservation of beta-cell mass. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 3313–3318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cadario, F.; Savastio, S.; Rizzo, A.M.; Carrera, D.; Bona, G.; Ricordi, C. Can Type 1 diabetes progression be halted? Possible role of high dose vitamin D and omega 3 fatty acids. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cadario, F.; Savastio, S.; Ricotti, R.; Rizzo, A.M.; Carrera, D.; Maiuri, L. Administration of vitamin D and high dose of omega 3 to sustain remission of type 1 diabetes. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baidal, D.A.; Sanchez, J.; Alejandro, R.; Blaschke, C.E.; Hirani, K.; Matheson, D.L.; Messinger, S.; Pugliese, A.; Rafkin, L.E.; Roque, L.A.; et al. POSEIDON study: A pilot, safety and feasibility trial of high--dose omega-3 fatty acids and high--dose cholecalciferol supplementation in type 1 diabetes. CellR4 2018, 6, e2489. [Google Scholar]

- Holst, J.J. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 1409–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Nian, C.; Doudet, D.J.; McIntosh, C.H. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition with MK0431 improves islet graft survival in diabetic NOD mice partially via T-cell modulation. Diabetes 2009, 58, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Gao, J.; Hao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, H.; O’Brien, T.D. Reversal of new-onset diabetes through modulating inflammation and stimulating beta-cell replication in nonobese diabetic mice by a dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 3049–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Nian, C.; McIntosh, C.H. Sitagliptin (MK0431) inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV decreases nonobese diabetic mouse CD4+ T-cell migration through incretin-dependent and -independent pathways. Diabetes 2010, 59, 1739–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Long, M.; Qu, H.; Shen, R.; Zhang, R.; Xu, J. DPP-4 Inhibitors as Treatments for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 5308582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, M.M.; Pinheiro, F.M.; Torres, M.A. Four-year clinical remission of type 1 diabetes mellitus in two patients treated with sitagliptin and vitamin D3. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case. Rep. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapti, E.; Karras, S.; Grammatiki, M.; Mousiolis, A.; Tsekmekidou, X.; Potolidis, E. Combined treatment with sitagliptin and vitamin D in a patient with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case. Rep. 2016, 2016, 150136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, M.M.; Pinheiro, F.M.M.; Trabachin, M.L. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) combined with vitamin D3: An exploration to treat new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus and latent autoimmune diabetes in adults in the future. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 57, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, G.; Focosi, D.; Marchi, B.; Randazzo, E.; De Donno, M.; Vierucci, F. Administering 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in vitamin D-deficient young type 1A diabetic patients reduces reactivity against islet autoantigens. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitocco, D.; Crinò, A.; di Stasio, E.; Manfrini, S.; Guglielmi, C.; Spera, S. The effects of calcitriol and nicotinamide on residual pancreatic beta-cell function in patients with recent-onset Type 1 diabetes (IMDIAB XI). Diabet. Med. 2006, 23, 920–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.; Kaupper, T.; Adler, K.; Foersch, J.; Bonifacio, E.; Ziegler, A.G. No effect of the 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on beta-cell residual function and insulin requirement in adults with new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, C.; Pitocco, D.; Napoli, N.; di Stasio, E.; Maggi, D.; Manfrini, S. No protective effect of calcitriol on beta-cell function in recent-onset type 1 diabetes: The IMDIAB XIII trial. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1962–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubodera, N. A new look at the most successful prodrugs for active vitamin D (D hormone): Alfacalcidol and doxercalciferol. Molecules 2009, 14, 3869–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zold, E.; Szodoray, P.; Nakken, B.; Barath, S.; Kappelmayer, J.; Csathy, L.; Barta, Z. Alfacalcidol treatment restores derailed immune-regulation in patients with undifferentiated connective tissue disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2011, 10, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizka, A.; Setiati, S.; Harimurti, K.; Sadikin, M.; Mansur, I.G. Effect of Alfacalcidol on Inflammatory markers and T Cell Subsets in Elderly with Frailty Syndrome: A Double Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Acta Med. Indones. 2018, 50, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ataie-Jafari, A.; Loke, S.C.; Rahmat, A.B.; Larijani, B.; Abbasi, F.; Leow, M.K. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of alphacalcidol on the preservation of beta cell function in children with recent onset type 1 diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liao, L.; Yan, X.; Huang, G.; Lin, J.; Lei, M. Protective effects of 1-alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 on residual beta-cell function in patients with adult-onset latent autoimmune diabetes (LADA). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2009, 25, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. SACN Vitamin D and Health Report; Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition: London, UK, 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-vitamin-d-and-health-report (accessed on 3 September 2019).

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyatzadeh, S.S.; Bagherniya, M.; Abdollahi, Z.; Ferns, G.A.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M. What is the best solution to manage vitamin D deficiency? IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Givens, D.I. Food fortification and biofortification as potential strategies for prevention of vitamin D deficiency. Nutr. Bull. 2019, 44, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S.; März, W.; Cashman, K.D.; Kiely, M.E.; Whiting, S.J.; Holick, M.F. Rationale and Plan for Vitamin D Food Fortification: A Review and Guidance Paper. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoriou, E.; Mamais, I.; Tzanetakou, I.; Lavranos, G.; Chrysostomou, S. The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation in Newly Diagnosed Type 1 Diabetes Patients: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2017, 14, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazahery, H.; von Hurst, P.R. Factors Affecting 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration in Response to Vitamin D Supplementation. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5111–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Boucher, B.J.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Lahore, H. Why vitamin D clinical trials should be based on 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante, M.; Ricordi, C.; Baidal, D.A.; Alejandro, R.; Lanzoni, G.; Sears, B. VITAL study: An incomplete picture? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 3142–3147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Study Design | Study Population | Study Treatment and Duration | Main Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial | n = 38 Mean age (intervention group and placebo group): 13.5 ± 5.1 vs. 12.5 ± 4.8 years Mean T1D duration: (intervention group and placebo group): 2.2 ± 1.2 vs. 2.7 ± 1.7 months | Patients were randomly assigned to receive cholecalciferol (2000 IU/day) or placebo for 18 months | Significant increase in Tregs percentage and MCP-1 levels at 12 months in cholecalciferol group vs. placebo group Significant decrease in HbA1c levels at six months in cholecalciferol group vs. placebo group Significant decrease in GAD65 autoantibody titers at 18 months in cholecalciferol group vs. placebo group Stimulated C-peptide was significantly enhanced during the first 12 months in cholecalciferol group vs. placebo group Subjects in the cholecalciferol group were significantly less likely to progress towards undetectable fasting C-peptide at 18 months compared to subjects in the placebo group | Gabbay et al. [174] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | n = 30 Median age: 12 years (interquartile range, 11–16 years) Mean T1D duration (intervention group and placebo group): 61 ± 20 days vs. 61 ± 28 days | Patients were randomly assigned to receive cholecalciferol (70 IU/kg body weight/day) or placebo for 12 months | Significant improvement in suppressive capacity of Tregs in cholecalciferol group vs. placebo group | Treiber et al. [176] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial | n = 39 Median age: 44 years (interquartile range, 34–52 years) Mean T1D duration: 12.3 years (interquartile range, 2.8–24.5 years) | Patients were randomly assigned to receive either cholecalciferol (4000 IU/day) for three months and placebo for the following three months, or the sequential alternative Effects of cholecalciferol treatment were assessed based on intra-individual changes between intervention and placebo periods for outcome measures (primary outcome was a change of Tregs percentage, whereas secondary outcomes were changes in HbA1c and daily insulin requirements) | Cholecalciferol treatment was associated with a significant increase in Tregs percentage (only in males), along with a significant reduction in daily insulin requirements and HbA1c | Bogdanou et al. [175] |

| Prospective, case-control interventionaltrial | n = 30 Mean age (intervention group and control group): 10.8 ± 1.78 years vs. 9.73 ± 1.38 years Mean T1D duration: 1.12 ± 1.73 years | Fifteen T1D patients were assigned to the intervention group (cholecalciferol 2000 IU/day plus calcium 25 mg/kg/day) for six months, whereas fifteen age-matched T1D patients were enrolled and followed up as controls for six months | Patients in the intervention group showed a non-significant trend towards a lower decline in stimulated C-peptide levels at six months compared to patients in the control group | Mishra et al. [177] |

| Retrospective study | n = 73 children included in the final analysis Mean age: 7.7 ± 4.4 years Duration of T1D: n/a | Patients with serum 25(OH)D levels < 12 ng/mL * were treated with cholecalciferol 6000 IU/day for three months Patients with serum 25(OH)D levels between 12 and 20 ng/mL * were treated with cholecalciferol 400 IU/day for three months | Cholecalciferol treatment was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c levels | Giri et al. [178] |

| Prospective, case-control interventionalstudy | n = 72 Age (inclusion criteria): six to 12 years Duration of T1D (inclusion criteria): between one and two years | Forty-two participants received cholecalciferol(3000 IU/day) in combination with insulin therapy for one year, whereas thirty age-matched controls received insulin therapy alone | Patients in cholecalciferol group exhibited significantly lower mean levels of fasting blood glucose, HbA1c and total daily insulin doses, along with greater mean levels of stimulated C-peptide compared to the control group | Panjiyar et al. [179] |

| Randomized, prospective, crossover study | n = 25 Mean age (vitamin D-sufficient group and vitamin D-deficient group): 17.2 ± 1.9 years vs. 16.2 ± 1.8 years Mean T1D duration (vitamin D-sufficient group and vitamin D-deficient group): 8.4 ± 4.67 years vs. 7.0 ± 3.94 years | Subjects received cholecalciferol (20,000 IU/week) for six months, either immediately or after six months of observation | Cholecalciferol treatment did not affect HbA1c, total daily insulin doses, and serum levels of inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α) | Shih et al. [180] |

| Randomized, double-blind controlled trial | n = 52 Mean age (intervention group and control group): 9.5 ± 3.9 vs. 9.0 ± 4.4 years Duration of T1D (intervention group and control group): 4.75 ± 3.0 vs. 4.0 ± 2.5 years | Oral cholecalciferol was administered at a dose of 60,000 IU/monthly for six months in addition to insulin therapy in the intervention group, whereas only insulin therapy was administered in the control group | Significant increase in mean fasting C-peptide levels in the intervention group compared to the control group No significant changes were observed between intervention and control group in HbA1c levels and mean daily insulin requirements | Sharma et al. [181] |

| Pilot interventional study | n = 42 Mean age: 12.5 ± 3.5 years Mean T1D duration: 4.8 ± 3.3 years | Participants with serum 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL * were treated with a single oral cholecalciferol dose of 100,000 IU (two to 10 years) or 160,000 IU (>10 years) | No significant differences in mean HbA1c levels for one year before and one year after cholecalciferol treatment, or for three months before and after cholecalciferol treatment | Perchard et al. [182] |

| Open-label, randomized trial | n = 15 Median age (intervention group and control group): 7.2 vs. 6.6 years Duration of T1D: median time from diagnosis to screening was 119 days in the intervention group and 106 days in the control group | Participants received either autologous UCB infusion followed by 12-month supplementation with oral cholecalciferol (2000 IU/day) and DHA (38 mg/kg/day) plus intensive diabetes management (intervention group), or intensive diabetes management alone (control group) | Area under the curve C-peptide declined and daily insulin doses increased in both groups compared to baseline No significant differences were observed between groups in terms of HbA1c levels, Tregs frequency, total CD4 counts, and autoantibody titers | Haller et al. [193] |

| Pilot interventional study | n = 15 patients Mean age: 12 ± 0.9 years Mean T1D duration: 0.7 ± 0.2 years | Eight patients with vitamin D deficiency (out of fifteen consecutive T1D patients) received calcidiol to achieve and maintain serum 25(OH)D levels between 50 and 80 ng/mL for up to one year. The remaining seven patients with serum 25(OH)D levels ≥20 ng/mL were not supplemented Starting calcidiol dose was 10 μg/day. Calcidiol dose was progressively adjusted (up to 28 ± 8.2 μg/day) until serum 25(OH)D levels were steadily in the desired range (50–80 ng/mL) | Significant reduction in peripheral blood mononuclear cell reactivity against GAD65 and proinsulin was observed in the supplemented group at two months Fasting C-peptide levels remained stable after one-year treatment with calcidiol | Federico et al. [206] |

| Open-label, randomized controlled trial | n = 70 Mean age: 13.6 ± 7.6 years Duration of T1D (inclusion criteria): <four weeks | Participants were randomized to receive calcitriol (0.25 μg on alternate days) or nicotinamide (25 mg/kg/day) and followed up for one year | Calcitriol treatment was temporarily associated with a significant reduction in daily insulin requirements (up to six months) No significant differences were observed between calcitriol and nicotinamide groups in terms of fasting and stimulated C-peptide and HbA1c levels | Pitocco et al. [207] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | n = 40 Median age: 31.4 ± 6.8 years Median T1D duration (intervention group and placebo group): 35 days vs. 40 days | Participants were randomly assigned to calcitriol (0.25 μg/day) or placebo for nine months and followed up for a total of 18 months | No significant differences were observed between groups in terms of fasting and stimulated C-peptide levels and daily insulin requirements | Walter et al. [208] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | n = 27 Median age: 18 years Duration of T1D (inclusion criteria): <12 weeks | Participants were randomized to receive calcitriol (0.25 μg/day) or placebo and followed up for two years | No significant differences were observed between groups in terms of fasting and stimulated C-peptide levels, HbA1c levels and daily insulin requirements | Bizzarri et al. [209] |

| Randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial | n = 54 Mean age: 10.1 ± 2.1 years Mean T1D duration: 43 ± 15 days | Participants were randomized to receive alfacalcidol (0.25 μg twice daily) or placebo for six months | Participants in alfacalcidol group showed significantly higher fasting C-peptide levels and lower daily insulin requirements compared to placebo group | Ataie-Jafari et al. [213] |

| Prospective randomized controlled trial | n = 35 (LADA patients) Mean age (insulin group and insulin plus alfacalcidol group): 42.8 ± 12.9 years vs. 38.5 ± 12.5 years Median duration of LADA (insulin group and insulin plus alfacalcidol group): 0.5 years vs. one year | Participants were randomly assigned to receive insulin therapy alone or insulin therapy plus alfacalcidol (0.5 μg/day) for one year | 70% of patients treated with alfacalcidol maintained or increased fasting C-peptide levels after one year of treatment, whereas only 22% of patients treated with insulin therapy alone maintained stable fasting C-peptide levels Subgroup analysis showed that patients with a shorter disease duration (<one year) in the alfacalcidol plus insulin group exhibited significantly higher fasting and post-prandial C-peptide levels | Li et al. [214] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Infante, M.; Ricordi, C.; Sanchez, J.; Clare-Salzler, M.J.; Padilla, N.; Fuenmayor, V.; Chavez, C.; Alvarez, A.; Baidal, D.; Alejandro, R.; et al. Influence of Vitamin D on Islet Autoimmunity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2185. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092185

Infante M, Ricordi C, Sanchez J, Clare-Salzler MJ, Padilla N, Fuenmayor V, Chavez C, Alvarez A, Baidal D, Alejandro R, et al. Influence of Vitamin D on Islet Autoimmunity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2019; 11(9):2185. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092185

Chicago/Turabian StyleInfante, Marco, Camillo Ricordi, Janine Sanchez, Michael J. Clare-Salzler, Nathalia Padilla, Virginia Fuenmayor, Carmen Chavez, Ana Alvarez, David Baidal, Rodolfo Alejandro, and et al. 2019. "Influence of Vitamin D on Islet Autoimmunity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 1 Diabetes" Nutrients 11, no. 9: 2185. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092185

APA StyleInfante, M., Ricordi, C., Sanchez, J., Clare-Salzler, M. J., Padilla, N., Fuenmayor, V., Chavez, C., Alvarez, A., Baidal, D., Alejandro, R., Caprio, M., & Fabbri, A. (2019). Influence of Vitamin D on Islet Autoimmunity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients, 11(9), 2185. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092185