Influence of Bioactive Nutrients on the Atherosclerotic Process: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Nutrients in Atherosclerotic Disease

2.1. Fiber

2.2. Micronutrients

3. Bioactive Compounds and Atherosclerosis

3.1. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

3.2. Lycopene

3.3. Plant Sterols and Stanols

4. Polyphenols

4.1. Flavonoids

4.1.1. Flavanols

4.1.2. Catechins

4.1.3. Quercetin

4.1.4. Anthocyanins

4.1.5. Isoflavones

4.2. Stilbens

4.3. Other Polyphenols

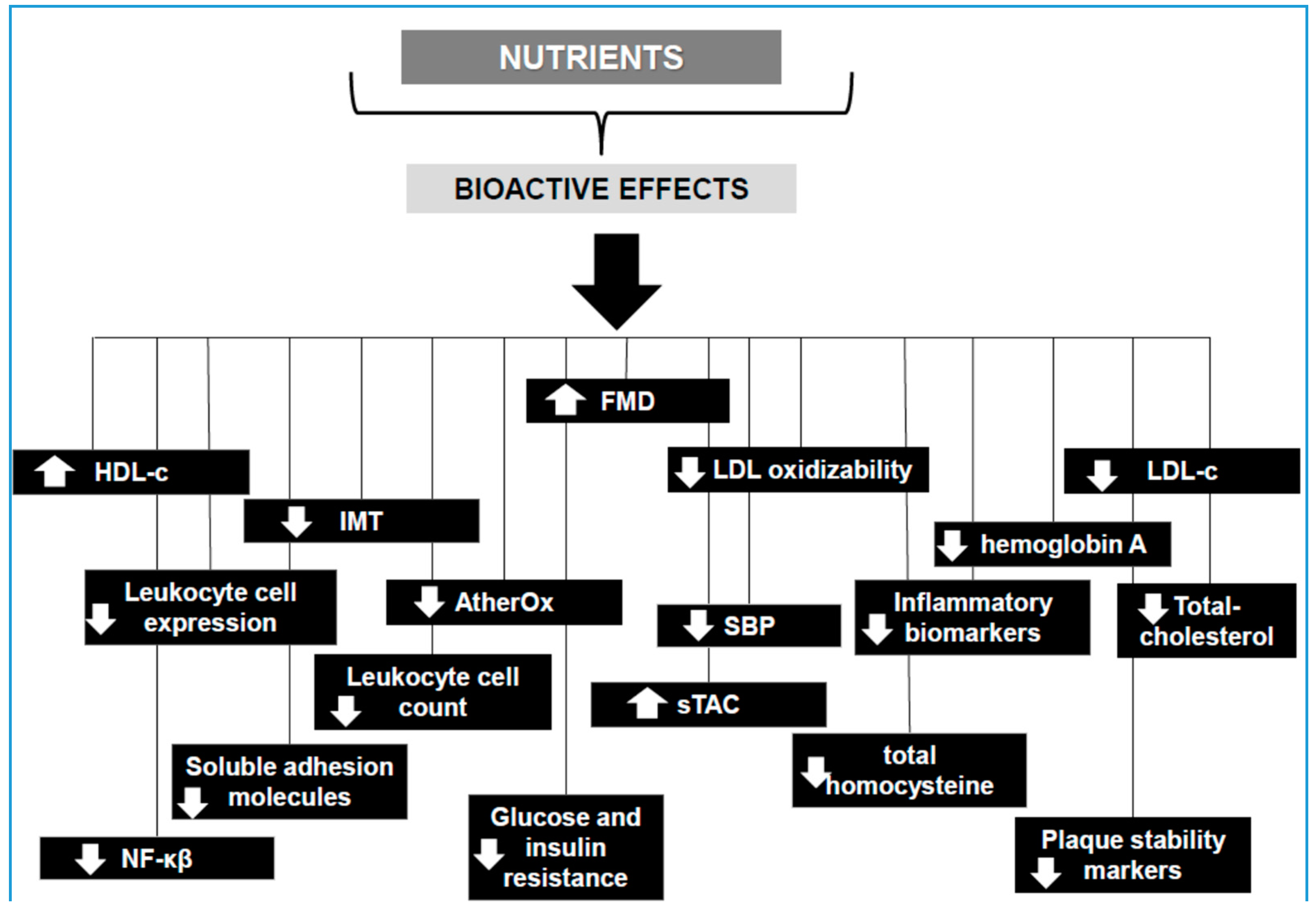

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansson, G.K.; Hermansson, A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, A.M.; Hansson, G.K. Innate immune signals in atherosclerosis. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 134, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Virani, S.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Delling, F.N.; Deo, R.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e67–e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Go, A.S.; Arnett, D.K.; Blaha, M.J.; Cushman, M.; Das, S.R.; de Ferranti, S.; Despres, J.P.; Fullerton, H.J.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 133, e38–e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosamond, W.; Flegal, K.; Furie, K.; Go, A.; Greenlund, K.; Haase, N.; Hailpern, S.M.; Ho, M.; Howard, V.; Kissela, B.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2008, 117, e25–e146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- European Cardiovascular Disease Statics 2017. Available online: http://www.ehnheart.org/cvd-statistics/cvd-statistics-2017.html (accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Vital Signs: Avoidable Deaths from Heart Disease, Stroke, and Hypertensive Disease—United States, 2001–2010. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6235a4.htm (accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Sisti, L.G.; Dajko, M.; Campanella, P.; Shkurti, E.; Ricciardi, W.; de Waure, C. The effect of multifactorial lifestyle interventions on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials conducted in the general population and high risk groups. Prev. Med. 2018, 109, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waure, C.; Lauret, G.-J.; Ricciardi, W.; Ferket, B.; Teijink, J.; Spronk, S.; Myriam Hunink, M.G. Lifestyle Interventions in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandian, J.; Gall, S.; Kate, M.; Silva, G.; Akinyemi, R.; Ovbiagele, B.; Lavados, P.; Gandhi, D.; Thrift, A. Prevention of stroke: A global perspective. Lancet 2018, 392, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, P.; Fuster, V. Cardiovascular Risk Factor Control for All. JAMA 2017, 318, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Roos, B. A key role for dietary bioactives in the prevention of atherosclerosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 1001–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.; Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention by Diet Modification: JACC Health Promotion Series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisamatsu, T.; Miura, K.; Fujiyoshi, A.; Kadota, A.; Miyagawa, N.; Satoh, A.; Zaid, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Horie, M.; Ueshima, H.; et al. Serum magnesium, phosphorus, and calcium levels and subclinical calcific aortic valve disease: A population-based study. Atherosclerosis 2018, 273, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, A.B.; Miyawaki, N.; Moon, J.; Kasselman, L.J.; Voloshyna, I.; D’Avino, R., Jr.; De Leon, J. CKD, arterial calcification, atherosclerosis and bone health: Inter-relationships and controversies. Atherosclerosis 2018, 278, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Calvo, N.; Martínez-González, M.Á. Vitamin C Intake is Inversely Associated with Cardiovascular Mortality in a Cohort of Spanish Graduates: The SUN Project. Nutrients 2017, 9, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Flint, A.J.; Qi, Q.; van Dam, R.M.; Sampson, L.A.; Rimm, E.B.; Holmes, M.D.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Association between dietary whole grain intake and risk of mortality: Two large prospective studies in US men and women. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; van Dam, R.M.; Rimm, E.; Hu, F.B.; Qi, L. Whole-grain, cereal fiber, bran, and germ intake and the risks of all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality among women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2010, 121, 2162–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.S.; Qi, L.; Fahey, G.C., Jr.; Klurfeld, D.M. Consumption of cereal fiber, mixtures of whole grains and bran, and whole grains and risk reduction in type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 594–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, J.; Ye, X.; Xu, G. Association between dietary fiber intake and risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Xu, M.; Lee, A.; Cho, S.; Qi, L. Consumption of whole grains and cereal fiber and total and cause-specific mortality: Prospective analysis of 367,442 individuals. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Tong, X.; Li, L.; Cao, S.; Yin, X.; Gao, C.; Herath, C.; Li, W.; Jin, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Consumption of fruit and vegetable and risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 183, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiavaroli, L.; Mirrahimi, A.; Ireland, C.; Mitchell, S.; Sahye-Pudaruth, S.; Coveney, J.; Olowoyeye, O.; Patel, D.; de Souza, R.J.; Augustin, L.S.; et al. Cross-sectional associations between dietary intake and carotid intima media thickness in type 2 diabetes: Baseline data from a randomised trial. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buil-Cosiales, P.; Irimia, P.; Ros, E.; Riverol, M.; Gilabert, R.; Martinez-Vila, E.; Núñez, I.; Diez-Espino, J.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Serrano-Martínez, M. Dietary fibre intake is inversely associated with carotid intima-media thickness: A cross-sectionalassessment in the PREDIMED study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellen, P.B.; Liese, A.D.; Tooze, J.A.; Vitolins, M.Z.; Wagenknecht, L.E.; Herrington, D.M. Whole-grain intake and carotid artery atherosclerosis in a multiethnic cohort: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRae, M.P. Dietary Fiber Is Beneficial for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. J. Chiropr. Med. 2017, 16, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, J.; Tang, J.; Wang, J.J.; Lu, C.H.; Wang, P.X. Beneficial Effect of Higher Dietary Fiber Intake on Plasma HDL-C and TC/HDL-C Ratio among Chinese Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4726–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Shi, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, D. Exploration of the Association between Dietary Fiber Intake and Hypertension among U. S. Adults Using 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Blood Pressure Guidelines: NHANES 2007–2014. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.V.; Hannon, B.A.; An, R.; Holscher, H.D. Effects of isolated soluble fiber supplementation on body weight, glycemia, and insulinemia in adults with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1514–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Tómas, R.; Pérez-Llamas, F.; Sánchez-Campillo, M.; Gonzaléz-Silvera, D.; Cascales, A.I.; García-Fernández, M.; López-Jiménez, J.A.; Zamora Navarro, S.; Burgos, M.I.; LópezAzorín, F.; et al. Daily intake of fruit and vegetable soups processed in different ways increases human serum β- carotene and lycopene concentrations and reduces levels of several oxidative stress markers in healthy subjects. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, Z.; Drogan, D.; Weikert, C.; Boeing, H. Vitamin E and risk of cardiovascular diseases: A review of epidemiologic and clinical trial studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myung, S.K.; Ju, W.; Cho, B.; Oh, S.W.; Park, S.M.; Koo, B.K.; Park, B.J.; Korean Meta-Analysis Study Group. Efficacy of vitamin and antioxidant supplements in prevention of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013, 346, f10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesso, H.D.; Buring, J.E.; Christen, W.G.; Kurth, T.; Belanger, C.; MacFadyen, J.; Bubes, V.; Manson, J.E.; Glynn, R.J.; Gaziano, J.M. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: The Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008, 300, 2123–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashor, A.W.; Lara, J.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Effect of vitamin C on endothelial function in health and disease: A systematic review and metaanalysis of randomised controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 2014, 235, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, B.; Saedisomeolia, A.; Skilton, M.R. Association between Micronutrients Intake/Status and Carotid Intima Media Thickness: A Systematic Review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Manson, J.E.; Song, Y.; Sesso, H.D. Systematic review: Vitamin D and calcium supplementation in prevention of cardiovascular events. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beveridge, L.A.; Khan, F.; Struthers, A.D.; Armitage, J.; Barchetta, I.; Bressendorff, I.; Cavallo, M.G.; Clarke, R.; Dalan, R.; Dreyer, G.; et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Markers of Vascular Function: A Systematic Review and Individual Participant Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, E008273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia, J.; Heiss, G.; Ren, H.; Dolan, N.C.; Greenland, P.; Heckbert, S.R.; Johnson, K.C.; Manson, J.E.; Sidney, S.; Trevisan, M.; et al. Calcium/vitamin D supplementation and cardiovascular events. Circulation 2007, 115, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponda, M.P.; Huang, X.; Odeh, M.A.; Breslow, J.L.; Kaufman, H.W. Vitamin D may not improve lipid levels: A serial clinical laboratory data study. Circulation 2012, 126, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrero, J.J.; Fonollá, J.; Marti, J.L.; Jiménez, J.; Boza, J.J.; López-Huertas, E. Intake of fish oil, oleic acid, folic acid, and vitamins B-6 and E for 1 year decreases plasma C-reactive protein and reduces coronary heart disease risk factors in male patients in a cardiac rehabilitation program. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanri, A.; Moore, M.; Kono, S. Impact of C-reactive protein on disease risk and its relation to dietary factors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2007, 8, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Alonso, A.; Lee, D.H.; Delclos, G.L.; Jenny, N.S.; Jiang, R.; Lima, J.A.; Symanski, E.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Nettleton, J.A. Dietary micronutrient intakes are associated with markers of inflammation but not with markers of subclinical atherosclerosis. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Carluccio, M.A.; De Caterina, R. Nutraceuticals and prevention of atherosclerosis: Focus on omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and Mediterranean diet polyphenols. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2010, 28, e13ee19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Influence of specific nutrients on progression of atherosclerosis, vascular function, haemostasis and inflammation in coronary heart disease patients: A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, S. Omacor and omega-3 fatty acids for treatment of coronary artery disease and the pleiotropic effects. Am. J. Ther. 2014, 21, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. The role of marine omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids in inflammatory processes, atherosclerosis and plaque stability. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thies, F.; Garry, J.M.C.; Yaqoob, P.; Rerkasem, K.; Williams, J.; Shearman, C.P.; Gallagher, P.J.; Calder, P.C.; Grimble, R.F. Association of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids with stability of atherosclerotic plaques: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003, 361, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawood, A.L.; Ding, R.; Napper, F.L.; Young, R.H.; Williams, J.A.; Ward, M.J.; Gudmundsen, O.; Vige, R.; Payne, S.P.; Ye, S.; et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) from highly concentrated n3 fatty acid ethyl esters is incorporated into advanced atherosclerotic plaques and higher plaque EPA is associated with decreased plaque inflammation and increased stability. Atherosclerosis 2010, 212, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, K.S.; Clifton, P.M.; Keogh, J.B. The association between carotid intima media thickness and individual dietary components and patterns. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Liu, K.; Daviglus, M.L.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Jenny, N.S.; Jiang, R.; Ouyang, P.; Steffen, L.M.; Siscovick, D.; Wu, C.; et al. Intakes of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish in relation to measurements of subclinical atherosclerosis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzese, C.J.; Bliden, K.P.; Gesheff, M.G.; Pandya, S.; Guyer, K.E.; Singla, A.; Tantry, U.S.; Toth, P.P.; Gurbel, P.A. Relation of fish oil supplementation to markers of atherothrombotic risk in patients with cardiovascular disease not receiving lipid-lowering therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 115, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagi, S.; Aihara, K.; Fukuda, D.; Takashima, A.; Hara, T.; Hotchi, J.; Ise, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Tobiume, T.; Iwase, T.; et al. Effects of docosahexaenoic acid on the endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2015, 22, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousoulis, D.; Plastiras, A.; Siasos, G.; Oikonomou, E.; Verveniotis, A.; Kokkou, E.; Maniatis, K.; Gouliopoulos, N.; Miliou, A.; Paraskevopoulos, T.; et al. Omega-3 PUFAs improved endothelial function and arterial stiffness with a parallel antiinflammatory effect in adults with metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis 2014, 232, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniarski, A.; Haberka, M.; Mostowik, M.; Gołębiowska-Wiatrak, R.; Poręba, M.; Malinowski, K.P.; Gąsior, Z.; Konduracka, E.; Nessler, J.; Gajos, G. Treatment with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids does not improve endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes and very high cardiovascular risk: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (Omega-FMD). Atherosclerosis 2018, 271, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, M.A.; Cohen, D.J.A.; Liddle, D.M.; Robinson, L.E.; Ma, D.W.L. A review of the effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on blood triacylglycerol levels in normolipidemic and borderline hyperlipidemic individuals. Lipids Health Dis. 2015, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidayat, K.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.C.; Qin, L.Q.; Eggersdorfer, M.; Zhang, W. Effect of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on heart rate: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, N.; Guevara-Cruz, M.; Velázquez-Villegas, L.A.; Tovar, A.R. Nutrition and Atherosclerosis. Arch. Med. Res. 2015, 46, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.R.; Zou, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.M.; Xiao, X.; Ma, L.; Lin, X.M. Serum carotenoids in relation to risk factors for development of atherosclerosis. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 45, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karppi, J.; Kurl, S.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Rissanen, T.H.; Kauhanen, J. Plasma carotenoids are related to intima-media thickness of the carotid artery wall in men from eastern Finland. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesso, H.D.; Buring, J.E.; Norkus, E.P.; Gaziano, J.M. Plasma lycopene, other carotenoids, and retinol, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesso, H.D.; Buring, J.E.; Norkus, E.P.; Gaziano, J.M. Plasma lycopene, other carotenoids, and retinol and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderas-Martinez, P.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Casas, R.; Arranz, S.; Martínez-Huélamo, M.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Torrado, X.; Corella, D.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Estruch, R. Tomato Sauce Enriched with Olive Oil Exerts Greater Effects on Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors than Raw Tomato and Tomato Sauce: A Randomized Trial. Nutrients 2016, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thies, F.; Masson, L.F.; Rudd, A.; Vaughan, N.; Tsang, C.; Brittenden, J.; Simpson, W.G.; Duthie, S.; Horgan, G.W.; Duthie, G. Effect of a tomato-rich diet on markers of cardiovascular disease risk in moderately overweight, disease-free, middle-aged adults: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abete, I.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Navas-Carretero, S.; Bondia-Pons, I.; Zulet, M.A.; Martinez, J.A. A regular lycopene enriched tomato sauce consumption influences antioxidant status of healthy young-subjects: A crossover study. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gylling, H.; Plat, J.; Turley, S.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Ellegård, L.; Jessup, W.; Jones, P.J.; Lütjohann, D.; Maerz, W.; Masana, L.; et al. Plant sterols and plant stanols in the management of dyslipidaemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2014, 232, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumeron, F.; Bard, J.M.; Lecerf, J.M. Interindividual variability in the cholesterol-lowering effect of supplementation with plant sterols or stanols. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ras, R.T.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Trautwein, E.A. LDL-cholesterol-lowering effect of plant sterols and stanols across different dose ranges: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansel, B.; Courie, R.; Bayet, Y.; Delestre, F.; Bruckert, E. Phytosterols and atherosclerosis. Rev. Med. Intern. 2011, 32, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabra, C.E.; Simas-TorresKlein, M.R. Phytosterols in the Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2017, 109, 475–482. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Jiao, J.; Xu, J.; Zimmermann, D.; Actis-Goretta, L.; Guan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, L. Effects of plant stanol or sterol-enriched diets on lipid profiles in patients treated with statins: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demonty, I.; Ras, R.T.; van der Knaap, H.C.; Duchateau, G.S.; Meijer, L.; Zock, P.L.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Trautwein, E.A. Continuous dose-response relationship of the LDL-cholesterol-lowering effect of phytosterol intake. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, V.Z.; Ras, R.T.; Gagliardi, A.C.; Mangili, L.C.; Trautwein, E.A.; Santos, R.D. Effects of phytosterols on markers of inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2016, 48, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholle, J.M.; Baker, W.L.; Talati, R.; Coleman, C.I. The effect of adding plant sterols or stanols to statin therapy in hypercholesterolemic patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2009, 28, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ras, R.T.; Fuchs, D.; Koppenol, W.P.; Garczarek, U.; Greyling, A.; Keicher, C.; Verhoeven, C.; Bouzamondo, H.; Wagner, F.; Trautwein, E.A. The effect of a low-fat spread with added plant sterols on vascular function markers: Results of the Investigating Vascular Function Effects of Plant Sterols (INVEST) study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eussen, S.R.; de Jong, N.; Rompelberg, C.J.; Garssen, J.; Verschuren, W.M.; Klungel, O.H. Dose-dependent cholesterol-lowering effects of phytosterol/phytostanol-enriched margarine in statin users and statin non-users under free-living conditions. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escurriol, V.; Cofán, M.; Moreno-Iribas, C.; Larrañaga, N.; Martínez, C.; Navarro, C.; Rodríguez, L.; González, C.A.; Corella, D.; Ros, E. Phytosterol plasma concentrations and coronary heart disease in the prospective Spanish EPICcohort. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Gallego, J.; García-Mediavilla, M.V.; Sánchez-Campos, S.; Tuñón, M.J. Fruit polyphenols, immunity and inflammation. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, S15–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wu, J.H.Y. Flavonoids, Dairy Foods, and Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health: A Review of Emerging Biologic Pathways. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Mazur, A.; Scalbert, A. Polyphenols and Prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2005, 16, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, L.; Kroon, P.A.; Rimm, E.B.; Cohn, J.S.; Harvey, I.; Le Cornu, K.A.; Ryder, J.J.; Hall, W.L.; Cassidy, A. Flavonoids, flavonoid-rich foods, and cardiovascular risk: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desch, S.; Schmidt, J.; Kobler, D.; Sonnabend, M.; Eitel, I.; Sareban, M.; Rahimi, K.; Schuler, G.; Thiele, H. Effect of cocoa products on blood pressure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Hypertens. 2010, 23, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostertag, L.M.; O’Kennedy, N.; Kroon, P.A.; Duthie, G.G.; de Roos, B. Impact of dietary polyphenols on human platelet function—A critical review of controlled dietary intervention studies. Mol. Nutr. Food. Res. 2010, 54, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Liu, X.; Bai, Y.Y.; Li, S.H.; Sun, K.; He, C.; Hui, R. Short-term effect of cocoa product consumption on lipid profile: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monagas, M.; Khan, N.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Casas, R.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Llorach, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Estruch, R. Effect of cocoa powder on the modulation of inflammatory biomarkers in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Agell, M.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Sacanella, E.; Camino-Lopez, S.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Llorente-Cortes, V.; Tobias, E.; Roura, E.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; et al. Cocoa consumption reduces NF-κB activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in humans. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esser, D.; Mars, M.; Oosterink, E.; Stalmach, A.; Müller, M.; Afman, L.A. Dark chocolate consumption improves leukocyte adhesion factors and vascular function in overweight men. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1464–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, D.; Aggio, A.; Onori, L.; Croce, G.; Tiberti, S.; Ferri, C.; Ferri, L.; Desideri, G. Tea, flavonoids, and nitric oxide-mediated vascular reactivity. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 1554S–1560S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, E.J.; Ruxton, C.H.S.; Leeds, A.R. Black tea—Helpful or harmful? A review of the evidence. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, L.; Liu, W.; Elashoff, D. Green and black tea consumption and risk of stroke: A meta-analysis. Stroke 2009, 40, 1786–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochmann, N.; Lorenz, M.; Krosigk, A.V.; Martus, P.; Böhm, V.; Baumann, G.; Stangl, K.; Stangl, V. The efficacy of black tea in ameliorating endothelial function is equivalent to that of green tea. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, D.; Mulder, T.P.; Draijer, R.; Desideri, G.; Molhuizen, H.O.; Ferri, C. Black tea consumption dose-dependently improves flow-mediated dilation in healthy males. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki-Sugihara, N.; Kishimoto, Y.; Saita, E.; Taguchi, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Ichitani, M.; Ukawa, Y.; Sagesaka, Y.M.; Suzuki, E.; Kondo, K. Green tea catechins prevent low-density lipoprotein oxidation via their accumulation in low-density lipoprotein particles in humans. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Andrea, G. Quercetin: A flavonol with multifaceted therapeutic applications? Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dower, J.I.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Gijsbers, L.; Schalkwijk, C.; Kromhout, D.; Hollman, P.C. Supplementation of the Pure Flavonoids Epicatechin and Quercetin Affects Some Biomarkers of Endothelial Dysfunction and Inflammation in (Pre)Hypertensive Adults: A Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, A.; Witman, M.A.; Guo, Y.; Ives, S.; Richardson, R.S.; Bruno, R.S.; Jalili, T.; Symons, J.D. Acute, quercetin-induced reductions in blood pressure in hypertensive individuals are not secondary to lower plasma angiotensin-converting enzyme activity or endothelin-1: Nitric oxide. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodagari, H.R.; Farzaei, M.H.; Bahramsoltani, R.; Abdolghaffari, A.H.; Mahmoudi, M.; Rezaei, N. Dietary anthocyanins as a complementary medicinal approach for management of inflammatory bowel disease. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 9, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Chen, G.; Liao, D.; Zhu, Y.; Xue, X. Effects of Berries Consumption on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Meta-analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luís, Â.; Domingues, F.; Pereira, L. Association between berries intake and cardiovascular diseases risk factors: A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 740–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntz, S.; Kunz, C.; Herrmann, J.; Borsch, C.H.; Abel, G.; Fröhling, B.; Dietrich, H.; Rudloff, S. Anthocyanins from fruit juices improve the antioxidant status of healthy young female volunteers without affecting anti-inflammatory parameters: Results from the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over ANTHONIA (ANTHOcyanins in Nutrition Investigation Alliance) study. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davinelli, S.; Bertoglio, J.C.; Zarrelli, A.; Pina, R.; Scapagnini, G. A Randomized Clinical Trial Evaluating the Efficacy of an Anthocyanin-Maqui Berry Extract (Delphinol®) on Oxidative Stress Biomarkers. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Song, F.; Yao, Y.; Ya, F.; Li, D.; Ling, W.; Yang, Y. Effects of purified anthocyanin supplementation on platelet chemokines in hypocholesterolemic individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Tian, J.; Deng, X.; Ren, J.; Andrews, M.C.; Ni, H.; Ling, W.; Yang, Y. Plant food anthocyanins inhibit platelet granule secretion in hypercholesterolaemia: Involving the signaling pathway of PI3K–Akt. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 112, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saita, E.; Kondo, K.; Momiyama, Y. Anti-Inflammatory Diet for Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease: Antioxidant Foods. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2015, 8, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, S.; Ho, S.C. Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein containing isoflavones on the lipid profile. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taku, U.; Umegaki, K.; Sato, Y.; Taki, Y.; Endoh, K.; Watanabe, S. Soyisoflavones lower serum total and LDL cholesterol in humans: A metaanalysisof 11 randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokede, O.A.; Onabanjo, T.A.; Yansane, A.; Gaziano, J.M.; Djoussé, L. Soya products and serum lipids: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodis, H.N.; Mack, W.J.; Kono, N.; Azen, S.P.; Shoupe, D.; Hwang-Levine, J.; Petitti, D.; Whitfield-Maxwell, L.; Yan, M.; Franke, A.A.; et al. Isoflavone soy protein supplementation and atherosclerosis progression in healthy postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2011, 42, 3168–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Sun, L.L.; He, L.P.; Ling, W.H.; Liu, Z.M.; Chen, Y.M. Soy food consumption, cardiometabolic alterations and carotid intima-media thickness in Chinese adults. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrikanta, A.; Kumar, A.; Govindaswamy, V. Resveratrol content and antioxidant properties of underutilized fruits. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalgol, B.; Batirel, S.; Taga, Y.; Ozer, N.K. Resveratrol: French paradox revisited. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigis, M.C.; Sinclair, D.A. Mammalian sirtuins: Biological insights and disease relevance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010, 5, 253–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canto, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Feige, J.N.; Lagouge, M.; Noriega, L.; Milne, J.C.; Elliott, P.J.; Puigserver, P.; Auwerx, J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NADþ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 2009, 458, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zordoky, B.N.; Robertson, I.M.; Dyck, J.R. Preclinical and clinical evidence for the role of resveratrol in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 6, 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, P.; He, S.; Huang, D. Effect of resveratrol on blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogacci, F.; Tocci, G.; Presta, V.; Fratter, A.; Borghi, C.; Cicero, A.F.G. Effect of resveratrol on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled, clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2018, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, J.K.; Thomas, S.; Nanjan, M.J. Resveratrol supplementation improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movahed, A.; Nabipour, I.; Lieben Louis, X.; Thandapilly, S.J.; Yu, L.; Kalantarhormozi, M.; Rekabpour, S.J.; Netticadan, T. Antihyperglycemic effects of short term resveratrol supplementation in type 2 diabetic patients. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 851267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tome-Carneiro, J.; Gonzalvez, M.; Larrosa, M.; García-Almagro, F.J.; Avilés-Plaza, F.; Parra, S.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; Ruiz-Ros, J.A.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; et al. Consumption of a grape extract supplement containing resveratrol decreases oxidized LDL and ApoB in patients undergoing primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A triple-blind, 6-month follow-up, placebo controlled, randomized trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nagayama, D.; Saiki, A.; Shirai, K.; Tatsuno, I. Resveratrol Ameliorates Arterial Stiffness Assessed by Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. Heart J. 2017, 58, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyyedebrahimi, S.; Khodabandehloo, H.; Nasli Esfahani, E.; Meshkani, R. The effects of resveratrol on markers of oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, B.; Campen, M.J.; Channell, M.M.; Wherry, S.J.; Varamini, B.; Davis, J.G.; Baur, J.A.; Smoliga, J.M. Resveratrol for primary prevention of atherosclerosis: Clinical trial evidence for improved gene expression in vascular endothelium. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, R.; Estruch, R.; Sacanella, E. The Protective Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil on Immune-mediated Inflammatory Responses. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2018, 18, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Luna, R.; Muñoz-Hernandez, R.; Miranda, M.L.; Costa, A.F.; Jimenez-Jimenez, L.; Vallejo-Vaz, A.J.; Muriana, F.J.; Villar, J.; Stiefel, P. Olive oil polyphenols decrease blood pressure and improve endothelial function in young women with mild hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2012, 25, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Castillejo, S.; Valls, R.M.; Castañer, O.; Rubió, L.; Catalán, Ú.; Pedret, A.; Macià, A.; Sampson, M.L.; Covas, M.I.; Fitó, M.; et al. Polyphenol rich olive oils improve lipoprotein particle atherogenic ratios and subclasses profile: A randomized, crossover, controlled trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential Health Benefits of Olive Oil and Plant Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernáez, Á.; Fernández-Castillejo, S.; Farràs, M.; Catalán, Ú.; Subirana, I.; Montes, R.; Solà, R.; Muñoz-Aguayo, D.; Gelabert-Gorgues, A.; Díaz-Gil, Ó.; et al. Olive oil polyphenols enhance high-density lipoprotein function in humans: A randomized controlled trial. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Agli, M.; Maschi, O.; Galli, G.V.; Fagnani, R.; Dal Cero, E.; Caruso, D.; Bosisio, E. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by olive oil phenols via cAMP-phosphodiesterase. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killeen, M.J.; Linder, M.; Pontoniere, P.; Crea, R. NF-κβ signaling and chronic inflammatory diseases: Exploring the potential of natural products to drive new therapeutic opportunities. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Covas, M.I.; Fiol, M.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; López-Sabater, M.C.; Vinyoles, E.; et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urpi-Sarda, M.; Casas, R.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Romero-Mamani, E.S.; Valderas-Martínez, P.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Toledo, E.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Llorach, R.; et al. The Mediterranean diet pattern and its main components are associated with lower plasma concentrations of tumor necrosis factor receptor 60 in patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, M.P.; Sacanella, E.; Vazquez-Agell, M.; Morales, M.; Fitó, M.; Escoda, R.; Serrano-Martínez, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Benages, N.; Casas, R.; et al. Inhibition of circulating immune cell activation: A molecular antiinflammatory effect of the Mediterranean diet. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, R.; Sacanella, E.; Urpí-Sardà, M.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Ros, E.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Covas, M.I.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Fiol, M.; et al. The effects of the mediterranean diet on biomarkers of vascular wall inflammation and plaque vulnerability in subjects with high risk for cardiovascular disease. A randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, R.; Sacanella, E.; Urpí-Sardà, M.; Corella, D.; Castañer, O.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Ros, E.; Estruch, R. Long-Term Immunomodulatory Effects of a Mediterranean Diet in Adults at High Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in the PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea (PREDIMED) Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1684–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, R.; Urpi-Sardà, M.; Sacanella, E.; Arranz, S.; Corella, D.; Castañer, O.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lapetra, J.; Portillo, M.P.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of the Mediterranean Diet in the Early and Late Stages of Atheroma Plaque Development. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 3674390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, A.; Delgado, J.; Garcia-Rios, A.; Cruz-Teno, C.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Lora-Aguilar, P.; Rodriguez-Cantalejo, F.; Fuentes-Jimenez, F.; et al. Expression of proinflammatory, proatherogenic genes is reduced by the Mediterranean diet in elderly people. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Torre-Carbot, K.; Chavez-Servin, J.L.; Jauregui, O.; Castellote, A.I.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Nurmi, T.; Poulsen, H.E.; Gaddi, A.V.; Kaikkonen, J.; Zunft, H.F.; et al. Elevated circulating LDL phenol levels in men who consumed virgin rather than refined olive oil are associated with less oxidation of plasma LDL. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niki, E. Do free radicals play causal role in atherosclerosis? Low density lipoprotein oxidation and vitamin E revisited play causal role in atherosclerosis? Low density lipoprotein oxidation and vitamin E revisited. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2011, 48, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covas, M.I. Bioactive effects of olive oil phenolic compounds in humans: Reduction of heart disease factors and oxidative damage. Inflammopharmacology 2008, 16, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernáez, Á.; Castañer, O.; Goday, A.; Ros, E.; Pintó, X.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Serra-Majem, L.; et al. The Mediterranean Diet decreases LDL atherogenicity in high cardiovascular risk individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañer, O.; Covas, M.-I.; Khymenets, O.; Nyyssonen, K.; Konstantinidou, V.; Zunft, H.-F.; de la Torre, R.; Muñoz-Aguayo, D.; Vila, J.; Fitó, M. Protection of LDL from oxidation by olive oil polyphenols is associated with a downregulation of CD40-ligand expression and its downstream products in vivo in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmer, R.J.; Freund, M.; Flamme, J.; Sexton, J.; Lennon, R.; Romani, A.; Mulinacci, N.; Vinceri, F.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Beneficial effects of polyphenol-rich olive oil in patients with early atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nutrient/Bioactive Compound | Study Design | Participants | Type of Study | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber Chiavaroli et al. [23] | Ultrasonographic carotid intima media thickness (CIMT) at baseline, and 7-day food records | 325 participants with type 2 diabetes from three randomized controlled trials collected | Cross-sectional analysis | CIMT was significantly inversely associated with dietary legume intake (β = −0.019, p = 0.009), available carbohydrate (β = −0.004, p = 0.008), glycemic load (β = −0.001, p = 0.007) and starch (β = −0.126, p = 0.010), and directly associated with total (β = 0.004, p = 0.028) and saturated fat (β = 0.012, p = 0.006) |

| Buil-Cosiales et al. [24] | MD + EVOO (50 mL daily) or nuts (30 g daily) vs. a LFD. Dietary habits were assessed with 137-item FFQ and a 14-item questionnaire. Ultrasonographic CCA-IMT measurement at baseline. | 457 men and women aged between 55 and 80 years at high cardiovascular risk. | Cross-sectional study. | Non-adjusted model: significant inverse correlation between fiber intake and IMT (r = −0.27, p < 0.001) and adjusted-model (p < 0.03) for >35 g fiber/day in adults. |

| Mellen et al. [25] | 114-item FFQ. Ultrasonographic CCA-IMT measurement at baseline and at 2 years. | Multiethnic cohort with 1178 participants (56% female) aged 40–69 years with a range of glucose tolerance (normal, impaired, and diabetic). | Multicenter, prospective, observational study. | Whole-grain intake was inversely associated with CCA-IMT (β ± SE: −0.043 ± 0.013, p = 0.005). |

| Micronutrients Ponda et al. [39] | Participants were stratified according to deficient (<20 ng/mL), insufficient (20–29 ng/mL), and optimal (≥30 ng/mL) vitamin D levels. | 107,811 participants. Aged between 40–80 years. | Cross-sectional study. | Optimal vitamin D levels (≥30 ng/mL) were associated with lower mean total cholesterol, LDL-c, and TGs and higher HDL-c (p < 0.0001; all). |

| Carrero et al. [40] | Over one year, intake of 500 mL/day of a fortified dairy product containing EPA, DHA, oleic acid, folic acid, and vitamins A, B-6, D, and E (supplemented group) or 500 mL/day of semi-skimmed milk with added vitamins A and D (control group). | Patients with MI with a mean age of 52.6 ± 1.9 years in the supplemented group and 57.4 ± 1.8 years in the control group. | Longitudinal, randomized, controlled, double-blind intervention study. | ↓ Plasma total and LDL-cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and CRPin the supplemented group (p < 0.05). ↓ Plasma tHcy in both groups. |

| De Oliveira et al. [41] | 120-item, self-administered FFQ was used to assess usual food intake over the previous year. | 5181 participants from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Aged 45–84 years and free of diabetes and CVD. | Cross-sectional study. | Dietary nonheme iron and Mg intakes were inversely associated with tHcy concentrations (p-trend < 0.001 for both). Dietary Zn and heme iron were positively associated with CRP (p-trend = 0.002 and 0.01, respectively). A positive association was found between tHcy concentrations and Vitamin C (p-trend = 0.01) and an inverse association between Mg with CCA-IMT (p-trend = 0.001). |

| n-3 PUFA Cawood et al. [48] | Daily intake of placebo or n-3 PUFA (1.8 g EPA + DHA/day) capsules until surgery (median 21 days). | 121 patients awaiting carotid endarterectomy. >18 years of age. | Double-blind, placebo-controlled design. | n-3 PUFA group: ↑EPA (p < 0.0001) and ↓ foam cells (p = 0.0390), mRNA for MMP-7 (p = 0.0055), -9 (p = 0.0048) and −12 (p = 0.0044) and for IL-6 (p = 0.0395) and ICAM-1 (p = 0.0142). |

| Franzese et al. [51] | Compared use of fish oil supplementation in various subgroups: non lipid-lowering therapy vs. lipid-lowering therapy. | 600 men with CVD, aged 64.4 ± 10.1 year. | Observational case series study. | VLDL, IDLs, remnant lipoproteins, TG, LDL, AtherOx levels, collagen-induced platelet aggregation, thrombin-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength, and shear elasticity (p < 0.03 for all). |

| Tousoulis et al. [53] | Daily intake of n-3 PUFAs (2 g/day) or placebo for 12 weeks. 4-week washout periods. | 29 subjects, 14 females, and 15 males with MetSaged 44 ± 12 years. | Double-blind, placebo controlled, cross-over trial. | PUFAs: Significant improvement of FMD and PWV (p < 0.001 for all). ↓ IL-6, PAI-1 (p = 0.003; both) ↓ TG and total cholesterol levels |

| Siniarski et al. [54] | Daily intake of n-3 PUFAs (2 g/day) or placebo for 3 months. 4-week washout periods. | 74 patients with established ASCVD and T2DM. | Two-center, prospective randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. | Did not improve endothelial function indices (FMD and NMD). |

| Lycopene Karppi et al. [59] | Determination of plasma carotenoid concentrations and measurements of CCA-IMT by B-mode ultrasound. ~20 years follow-up. | 1212 elderly Finnish men aged 61–80 year. | Prospective study. | Higher concentrations of plasma β-cryptoxanthin (p = 0.043), lycopene (p = 0.045), and α-carotene (p = 0.046) were associated with lower CCA-IMT. |

| Sesso et al. [61] | Plasma lycopene, other carotenoids, retinol, and total cholesterol were measured. Mean follow-up of 4.8 years. | 28,345 female US health professionals free of CVD and cancer. Aged 45 years. | A prospective, nested, case-control study. | Higher plasma lycopene concentrations were associated with a lower risk of CVD in women. |

| Valderas-Martinez et al. [62] | Intake of 7.0 g of RT/kg BW, 3.5 g of TS/kg BW, 3.5 g of TSOO/Kg BW and 0.25 g of sugar dissolved in water/kg BW on a single occasion on four different days. | 40 healthy subjects (mean age of 28 ± 11 years). | Open, prospective, randomized, cross-over, controlled feeding trial. | RT: ↓ SBP, total cholesterol, TGs, or MCP-1 and ↑ folic acid and IL-10. TSOO: ↓ SBP, DBP, total cholesterol, TGs, IL-6, IL-18, MCP-1 and VCAM-1 and ↑ folic acid, IL-10. ↓ LFA-1 from T-lymphocytes and CD36 from monocytes. |

| Thies et al. [63] | A control diet (low in tomato-based foods), a high-tomato-based diet, or a control diet supplemented with lycopene capsules (10 mg/day) for 12 weeks. | 225 healthy volunteers (94 men and 131 women), moderately overweight (BMI:18.5–35) and aged 40–65 years. | Single-blind, randomized controlled dietary intervention study. | No changes in systemic markers (inflammatory markers, markers of insulin resistance, and sensitivity), lipid concentrations or arterial stiffness in all interventions. |

| Abete et al. [64] | Effect of the consumption of 160 g of two TSs with different concentrations of lycopene on oxidative stress markers: high-lycopene TS (27.2 mg of lycopene) vs. commercial TS (12.3 mg of lycopene). 4 weeks separated by a 2-week washout period. | 32 healthy patients (18 males and 14 females). Aged between 18–50 years with a BMI of 18.5–29.9 kg/m2. | Double-blind crossover nutritional intervention. | High-lycopene TS: ↓ LDL-ox (−9.27 ± 16.8%; p = 0.014). |

| Plant Sterols and Stanols Ras et al. [74] | 20 g/day of low-fat spread without (control) PS vs. with added PSs (3 g/day) during 12 weeks. Measurement of: FMD, serum lipids, arterial stiffness, BP. | 232 hypercholesterolemic participants (healthy men and postmenopausal women), aged 40–65 years | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel design. | Lower LDL-c levels (average of 0.26 mmol/L) |

| Eussen et al. [75] | Questionnaires on health and food intake were used to assess PS intake. Measurement of serum lipids. 5-year follow-up | 3,829 men and women (aged 31–71 years). | Retrospective cohort study. | Significant decrease of cholesterol (−0.32 mmol/L) with increasing intake of enriched margarine. |

| Escurriol et al. [76] | FFQ was used to assess PS intake. Measurement of serum lipids | Healthy men and women: 299 developed CHD and 584 as controls, aged between 30 and 69 years (Spanish EPIC cohort) | Case-control study. | High levels of PS →↑ HDL-c, cholesterol/HDL ratios, and ↓ glucose, TG and lathosterol, (p < 0.02; all). No correlation between APOE genotype and CHD risk or plasma phytosterols |

| Flavonoids Monagas et al. [84] | 4-weeks of intervention of: 40 g cocoa powder with 500 mL skim milk/d (C + M) or only 500 mL skim milk/d (M). Daily: 40.41 mg (+)-catechin 46.08 mg (−)-epicatechin 36.54 mg procyanidin B2 495.2 mg tot.PPh 425.7 mg tot.Pr | 42 high-risk volunteers (19 men and 23 women). Aged ≥55 years. | Randomized crossover study. | C + M: ↓ VLA-4, CD40, CD36 (monocytes) (p ≤ 0.028; all) ↓ P-selectin and ICAM-1 (p = 0.007; both) Non-significant changes: ↓ VCAM-1 and MCP-1 No effect: hs-CRP, IL-6, E-selectin |

| Vázquez-Agell et al. [85] | Acute intervention (6 h) of: 40 g Cocoa powder with 250 mL milk or water (W). Daily: 40.41 mg (+)-catechin 46.08 mg (−)-epicatechin 36.54 mg procyanidin B2 495.2 mg tot.PPh 425.7 mg tot.Pr | 18 healthy volunteers: 9 men and 9 women, aged 19–49 years). | Randomized crossover study. | ↓ NF-κβ (cacao + W; p < 0.05) ↓ E-selectin (cacao + W; p = 0.028) ↓ ICAM-1 (cacao + W or M; p ≤ 0.026, both) No effect: VCAM-1 |

| Esser et al. [86] | Daily consumption of high flavanol chocolate (HFC) and normal flavanol chocolate (NFC). 4-week intervention. | Healthy overweight men (age 45–70 years). | Randomized crossover study. | HFC intake: ↑ FMD 1% (p = 0.010) ↓ ICAM-1, ICAM-3 (p ≤ 0.023; both) ↓ Leukocyte cell count (p = 0.023) ↓ Leukocyte adhesion marker expression (p ≤ 0.047; all). |

| Jochmann et al. [90] | Measurement of FMD, before and 2 h after ingestion of either 500 mL water (control), black tea, or green tea in a cross-over study. | 21 healthy postmenopausal women. Average age: 58.7 ± 4.5 years. | Randomized crossover study. | Green tea: from baseline of 5.4 ± 2.3% to 10.2 ± 3% 2 h, p < 0.001 Black tea: from baseline of 5 ± 2.6% to 9.1 ± 3.6% 2 h after black tea consumption; p < 0.001 |

| Grassi et al. [91] | Five treatments with a twice daily intake of black tea (0, 100, 200, 400, and 800 mg tea flavonoids/day) in five periods lasting 1 week each. | 19 healthy men ranging from 18 to 70 years. | Randomized crossover study. | Black tea dose dependently increased FMD from 7.8% (control) to 9.0, 9.1, 9.6, and 10.3% after the different flavonoid doses, respectively (p = 0.0001). |

| Suzuki-Sugihar et al. [92] | Two sessions in which green tea capsules containing 1 g of catechins or placebo capsules were taken. Test days were separated by at least a 2-week washout period. | 19 healthy male volunteers ranging from 25 to 53 years. | Randomized crossover study | Green tea could reduce oxLDL in human participants. ↑ sTAC value 1 h after intake (p < 0.001). |

| Dower et al. [94] | (−)-epicatechin (100 mg/day), quercetin-3-glucoside (160 mg/day), or placebo capsules for a period of 4 weeks, in random order. 4-week washout periods. | 37 healthy (pre)hypertensive men and women (40–80 years). | Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. | ↓ sE-selectin by 27.4 ng/mL (p = 0.03) ↓ IL-1β by 20.23 pg/mL (p = 0.009) Z score for inflammation by 20.33 (p = 0.02) |

| Larson et al. [95] | Intake of a single-dose of purified quercetin aglycone (1095 mg) or placebo. | 5 normotensive men (n = 5; 24 ± 3 years; 24 ± 4 kg/m2) and 12 stage 1 hypertensive men (41 ± 12 years; 29 ± 5 kg/m2). | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. | ↓ BP of stage 1 hypertensive men. |

| Kuntz et al. [99] | 330 mL of beverage (placebo, juice and smoothie with 8.9, 983.7, and 840.9 mg/L of anthocyanin, respectively, for 14 days. 10-day washout periods | 30 healthy female volunteers, age between 23 and 27 years. | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. | Anthocyanin beverages: ↑ SOD, catalase, Trolox ↓ MDA |

| Davinelli et al. [100] | Intake of a standardized extract of maqui berry (162 mg anthocyanins) or a matched placebo, given 3 times daily for 4 weeks. | 42 overweight volunteer smokers, aged between 45 to 65 years. | Double-blind, placebo-controlled design. | ↓ oxLDL and 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α |

| Zhang et al. [101] | Intake of two anthocyanin capsules (320 mg anthocyanin/capsule) or placebo capsules twice daily for 24 weeks. | 150 hypercholesterolemic individuals, age between 40 to 65 years. | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. | Anthocyanin group: ↓ CXCL7, CXCL8, CXCL12, CCL2. Positive association between CXCL7 and CCL2 with LDL-c, hsCRP and IL-1β. Negative correlation between CXCL8 and HDL-c. Positive correlation between CXCL8 and sP-Selectin. |

| Song et al. [102] | Consumption of four anthocyanins capsules/day (total of 320 mg/day) vs. placebo capsules for 24 weeks. | 150 hypercholesterolaemic patients. | Randomized, double-blind clinical trial. | Anthocyanin group: ↓ β-TG, sP-selectin, and RANTES. Inhibition of pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic factors. |

| Hodis et al. [107] | Intake of daily doses of 25 g soy protein containing 91 mg aglycon isoflavone equivalents or placebo for 2.7 years. | 350 postmenopausal American women, between 45 to 92 years of age, without diabetes and CVD. | Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. | CIMT progression in −16%. |

| Bhatt et al. [116] | Intervention group: 250 mg/Once Daily resveratrol capsule supplementation + oral hypoglycemic agents vs. control group: oral hypoglycemic agents for a period of 3 months. | 62 patients with T2DM, aged between 30 and 70 years. | Prospective, open-label, randomized, controlled study | Resveratrol: ↓ hemoglobin A(1c), SBP, total cholesterol and LDL-c. No changes in HDL-c. |

| Movahed et al. [117] | Daily: 1000 mg of resveratrol capsule supplementation+oral hypoglycemic agents vs. 1000 mg of placebo capsule supplementation +oral hypoglycemic agents for a period of 45 days. | 66 patients with T2DM, aged between 20 and 65 years. | Randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded parallel clinical trial. | Resveratrol: ↓ hemoglobin A(1c), glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, and SBP. ↑ HDL-c |

| Tomé-Carneiro et al. [118] | Intake of one capsule (350 mg) daily of GE-RES (8 mg resveratrol), GE or placebo for 6 months. | 75 patients with T2DM, aged between 18 and 80 years. | Triple-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | GE-RES: −20% of oxLDL (p < 0.001), −9.18% of ApoB (p = 0.014), −4.5% of LDL-c (p = 0.04). +8.5% non-HDLc (total atherogenic cholesterol load)/ApoB |

| Imamura et al. [119] | Intake of 100-mg resveratrol tablet or placebo tablet for 12 weeks. | 50 eligible patients with T2DM (HbA1c > 7.0%). Average age 57–58 years. | Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. | Resveratrol: ↓ SBP, CAVI, and d-ROMs |

| Agarwal et al. [120] | Intake of 400 mg trans-resveratrol, 400 mg grape skin extract, and 100 mg quercetin (RESV GROUP) or a cellulose placebo for 30 days | 44 healthy subjects, >18 years. | Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. | RESV GROUP: ↓ IL-8,IFN-γ, sVCAM-1, sICAM-1, and ↓ fasting insulin |

| Olive oil Camargo et al. [135] | MD+EVOO, SFA-rich diet, CHO-PUFA diet for 3 weeks. | 20 healthy and elderly people. Mean age: 67.1 years. | Randomized crossover design study. | MD + EVOO: ↓ NF-κβ, MMP-9, TNF-α, and MCP-1 and ↑ IκBα expression |

| Hernáez et al. [139] | MD + EVOO (50 mL daily) or nuts (30 g daily) vs. a LFD. Dietary habits were assessed with 137-item FFQ and a 14-item questionnaire. LDL atherogenic traits (resistance against oxidation, size, composition, cytotoxicity) after 1 year of intervention. | 210 men and women aged between 55 and 80 years at high cardiovascular risk. | Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trial. | ↑ LDL resistance against oxidation (+6.46%) and LDL particle size (+3.06%). ↓ the degree of LDL oxidative modifications (−36.3%). LDL particles became cholesterol-rich (+2.41%) and less cytotoxic (−13.4%) compared to LFD. |

| Castañer et al. [140] | 25 mL olive oil with a LPC (2.7 mg/kg) or a high polyphenol content (HPC: 366 mg/kg) for 3 weeks separated by 2-week washout periods. | 180 healthy European volunteers aged 20–60 years. | Randomized, crossover, controlled trial. | The intake of polyphenol-rich olive oil reduces LDL oxidation and gene expression related to atherosclerotic and inflammation processes in PBMCs (CD40, MCP-1, ICAM-1, etc.). |

| Widmer et al. [141] | Daily intake of 30 mL of EVOO or EGCG+EVOO for 4 months. | 52 volunteers with early atherosclerosis and over 18 years. | Randomized, double-blind, trial. | Improved endothelial function in both groups. EVOO group: ↓ sICAM, white blood cells, monocytes, lymphocytes, and platelets. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casas, R.; Estruch, R.; Sacanella, E. Influence of Bioactive Nutrients on the Atherosclerotic Process: A Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111630

Casas R, Estruch R, Sacanella E. Influence of Bioactive Nutrients on the Atherosclerotic Process: A Review. Nutrients. 2018; 10(11):1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111630

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasas, Rosa, Ramon Estruch, and Emilio Sacanella. 2018. "Influence of Bioactive Nutrients on the Atherosclerotic Process: A Review" Nutrients 10, no. 11: 1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111630

APA StyleCasas, R., Estruch, R., & Sacanella, E. (2018). Influence of Bioactive Nutrients on the Atherosclerotic Process: A Review. Nutrients, 10(11), 1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111630