Probing Early and Long-Term Drought Responses in Kauri Using Canopy Hyperspectral Imaging

Highlights

- A combination of structural and pigment-related narrow band hyperspectral indices (NBHIs), analysed across multiple time points, enabled earlier detection of water stress in kauri seedlings compared to conventional physiological measures.

- Pigment-related indices robustly predicted variation in equivalent water thickness (EWT), accounting for up to 87% of observed variance in field-based juvenile kauri trees.

- Demonstrated the consistency and efficacy of canopy hyperspectral imaging to characterise water stress in kauri.

- Offers scalable pathways for broader forest health monitoring of indigenous species such as kauri and drought-sensitive forest species.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

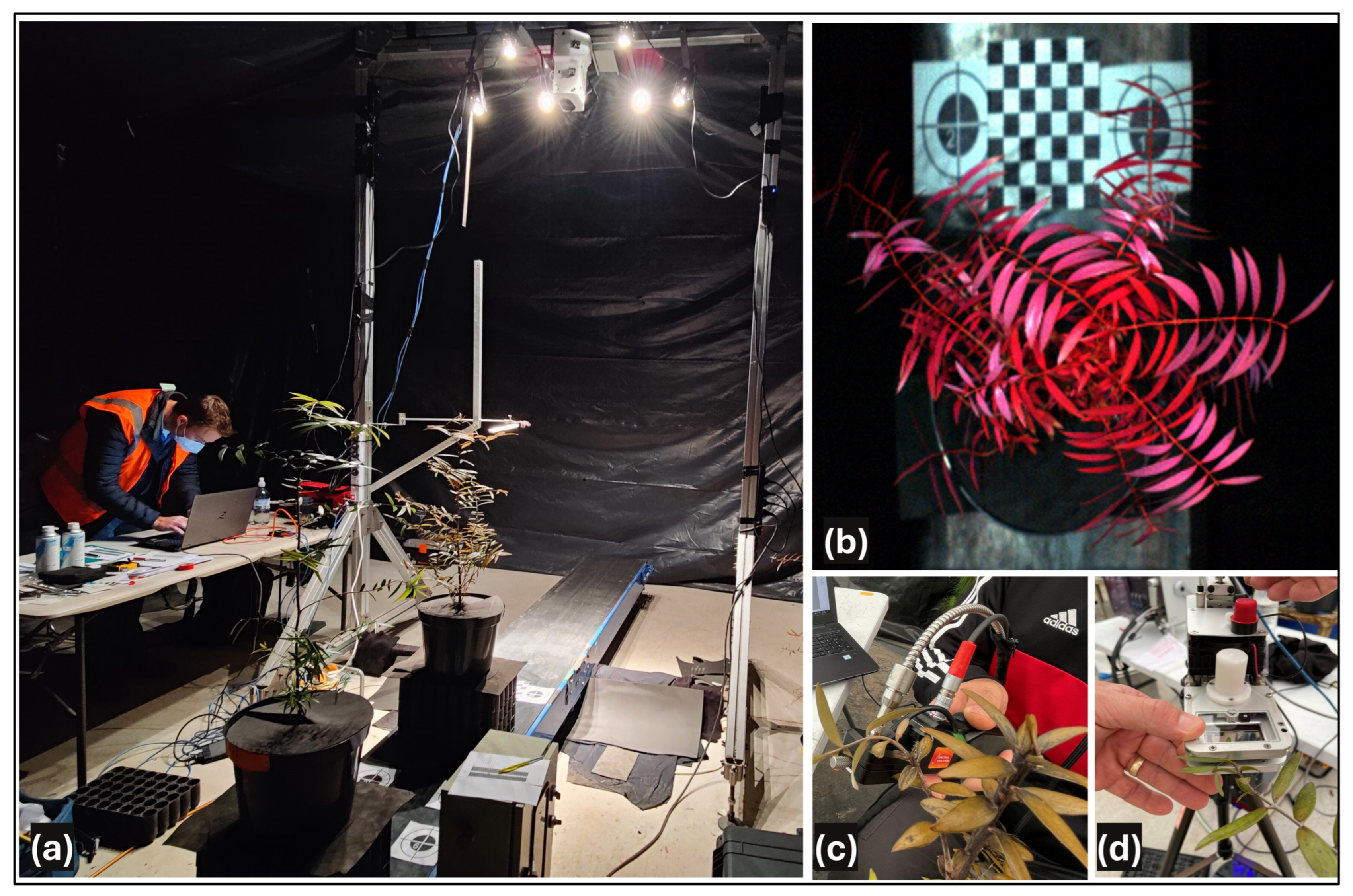

2.1. Controlled-Environment Experimental Design

2.1.1. Physiological and Biophysical Measurements

Stomatal Conductance and Assimilation

Leaf Water Content

Volumetric Water Content

2.1.2. Hyperspectral Measurements

Canopy-Level Hyperspectral Imaging

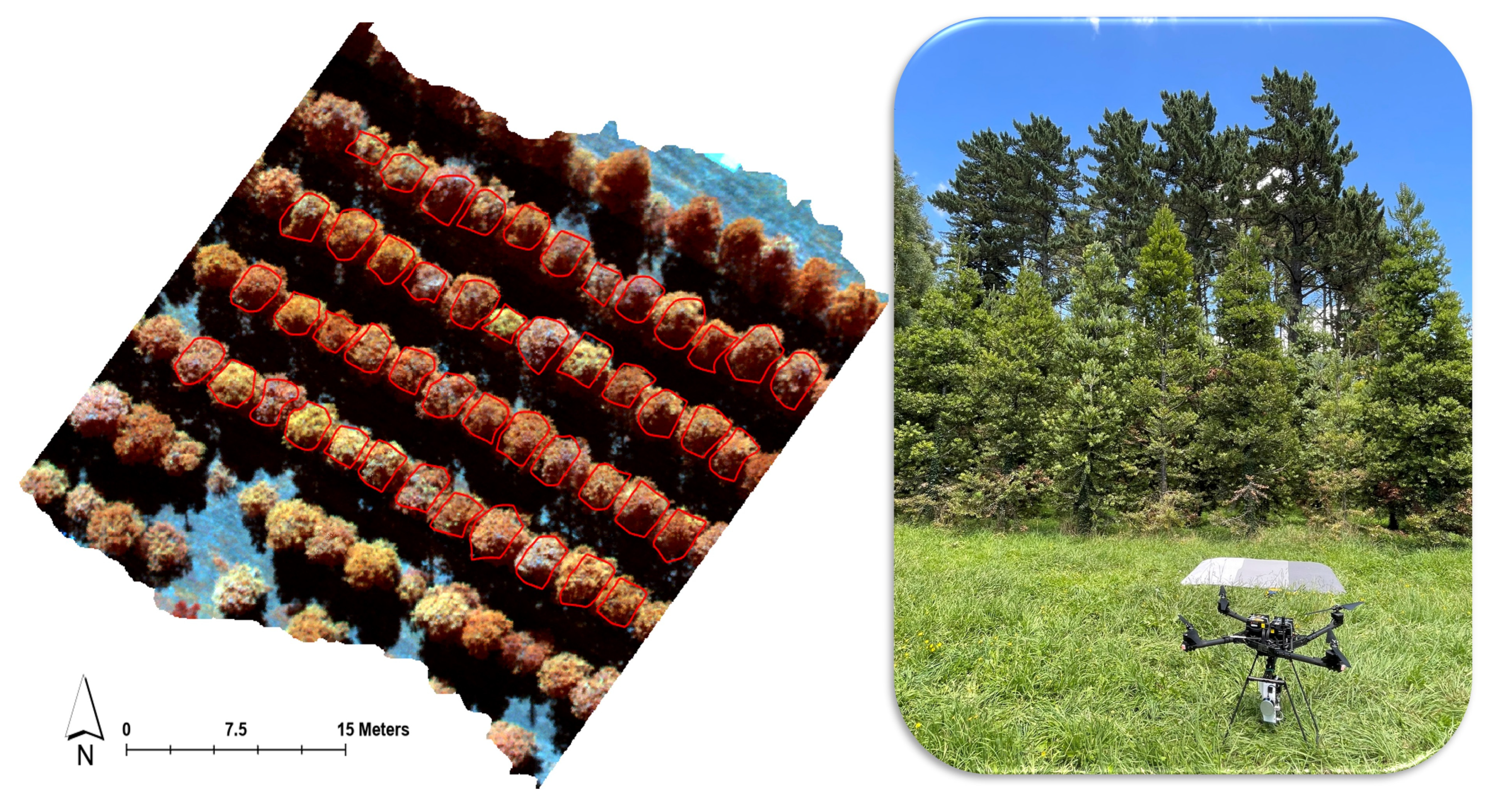

2.2. Experimental Design for the Juvenile Kauri Field Trial

2.2.1. UAV-Based Hyperspectral Data Acquisition

2.2.2. Field-Based Physiological and Biophysical Measurements

Soil Volumetric Water Content

Leaf Equivalent Water Thickness

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

2.3.1. Processing and Analysis of Hyperspectral Data

2.3.2. Approach for Classifying Control and Drought Treatments

3. Results

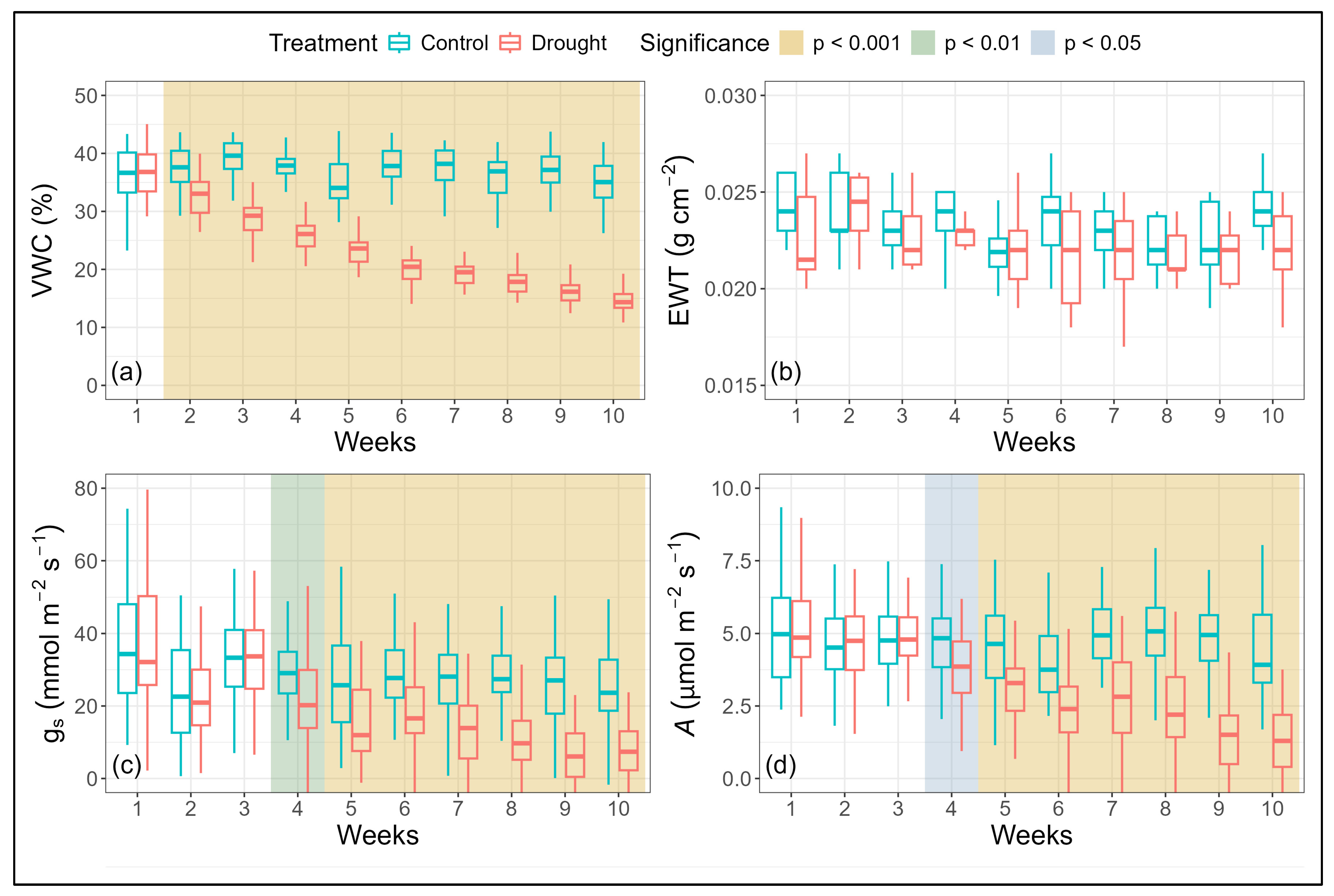

3.1. Kauri Seedlings Under Controlled-Environment

3.1.1. Variation in Seedling Physiology

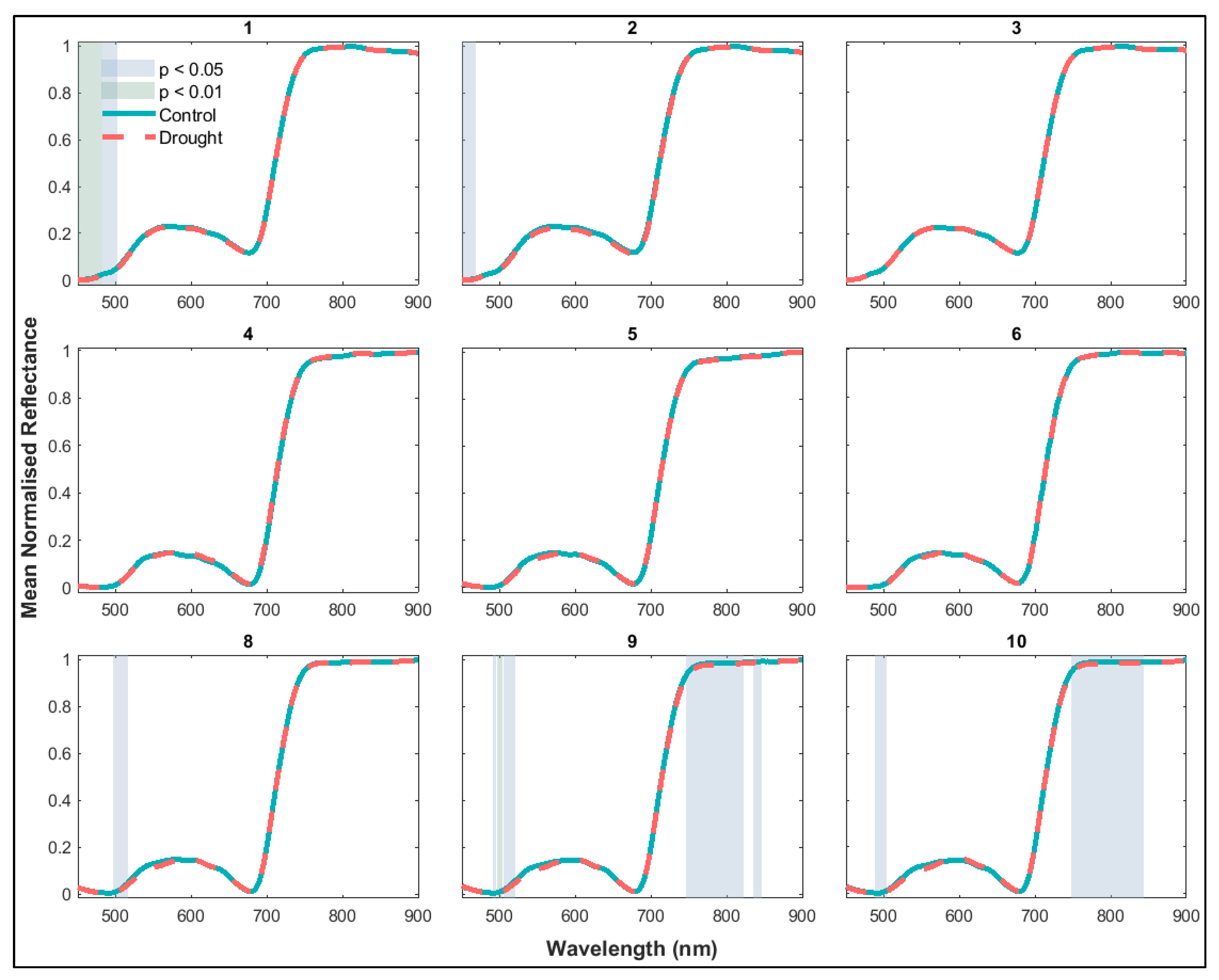

3.1.2. Variation in Seedling Canopy Spectra and Derived NBHIs

3.1.3. Classification of Control and Drought Kauri Seedlings

3.2. Field-Based Juvenile Kauri Trees

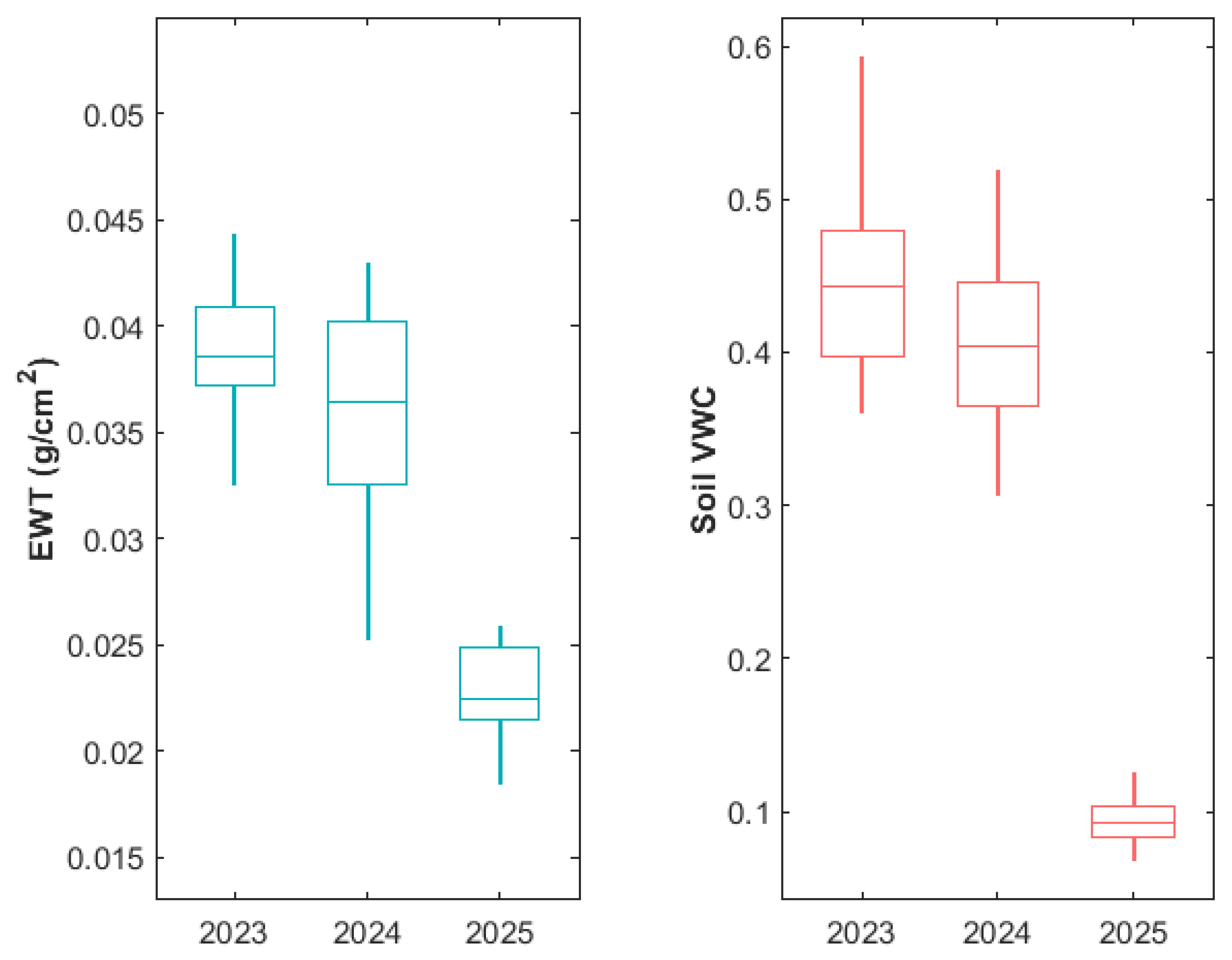

3.2.1. Variation in Juvenile Kauri Physiology

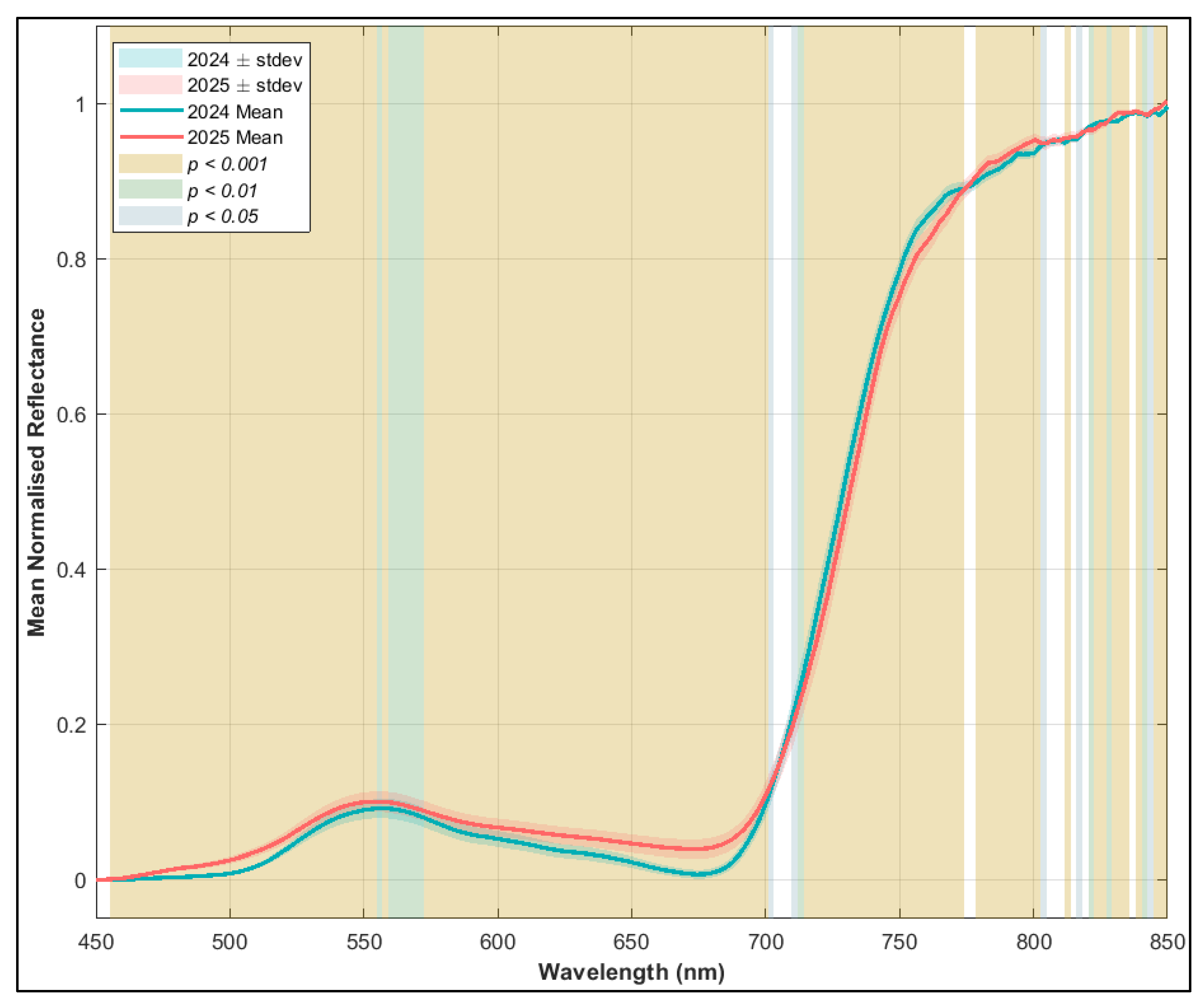

3.2.2. Variation in Juvenile Kauri Spectra and Derived NBHIs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Indices | Index Code | Equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural indices | |||

| Enhanced Vegetation Index | EVI | [56] | |

| Modified Simple Ratio | MSR | [57] | |

| Modified Triangular Veg. Index 1 | MTVI1 | [58] | |

| Normalized Difference Veg. Index | NDVI | [59] | |

| Optimized Soil-Adjusted Veg. Index | OSAVI | [60] | |

| Renormalized Difference Veg. Index | RDVI | [61] | |

| Simple Ratio | SR | [62] | |

| Triangular Vegetation Index | TVI | [63] | |

| Pigment indices | |||

| Carter Index | CAR | [64] | |

| Chlorophyll Index Red Edge | CI | [65] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Indices | CRI550 | [66,67] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Indices | CRI550_515 | [67] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Indices | CRI700 | [66,67] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Indices | CRI700_515 | [67] | |

| Reflectance band ratio indices | DCab | [68] | |

| Reflectance band ratio indices | DNIRCab | [68] | |

| Gitelson & Merzlyak index 1 | GM1 | [69] | |

| Gitelson & Merzlyak index 2 | GM2 | [69] | |

| Pigment Specific Normalized Difference c | PSNDc | [70] | |

| Plant Senescence Reflectance Index | PSRI | [71] | |

| Pigment Specific Simple Ratio Chlorophyll a | PSSRa | [70] | |

| Pigment Specific Simple Ratio Chlorophyll b | PSSRb | [70] | |

| Pigment Specific Simple Ratio Carotenoids c | PSSRc | [70] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Index | RNIR_CRI550 | [66,67] | |

| Carotenoid Reflectance Index | RNIR_CRI700 | [66,67] | |

| Structure-Intensive Pigment Index | SIPI | [72] | |

| Modified Chlorophyll Abs. Index | MCARI | [73] | |

| Modified Chlorophyll Abs. Index 1 | MCARI1 | [74] | |

| Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index | TCARI | [75] | |

| Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index/Optimized Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index | TCARI_OSAVI | [75] | |

| Vogelmann indices | VOG | [76] | |

| Vogelmann indices | VOG2 | [76] | |

| Vogelmann indices | VOG3 | [76] | |

| Normalized Pigments Index | NPCI | [72] | |

| Reflectance Curvature Index | CUR | [77] | |

| Carotenoid/Chlorophyll Ratio Index | PRICI | [78] | |

| Photochemical Refl. Index (515) | PRI515 | [79] | |

| Photochemical Refl. Index (570) | PRI570 | [43] | |

| Photochemical Refl. Index (512) | PRIm1 | [79] | |

| Photochemical Refl. Index (600) | PRIm2 | [43] | |

| Photochemical Refl. Index (670) | PRIm3 | [43] | |

| Photochemical Refl. Index (670 and 570) | PRIm4 | [79] | |

| Normalized Photoch. Refl. Index | PRIn | [80] | |

| Healthy-index | HI | [81] | |

| R/G/B indices | |||

| Blue Index | B | [82] | |

| Blue/green index | BGI | [83] | |

| Blue/red index | BRI | [15] | |

| Greenness Index | G | [82] | |

| Lichtenthaler Index 1 | LIC1 | [84] | |

| Lichtenthaler Index 2 | LIC2 | [84] | |

| Lichtenthaler Index 3 | LIC3 | [84] | |

| Lichtenthaler Index 4 | LIC4 | [84] | |

| Lichtenthaler Index 5 | LIC5 | [84] | |

| Lichtenthaler Index 6 | LIC6 | [84] | |

| Lichtenthaler Index 7 | LIC7 | [84] | |

| Redness Index | R | [85] | |

| Ratio Analysis of Reflectance Spectra | RARS | [86] | |

| Red/green indices | RGI | [82] | |

References

- Steward, G.A.; Beveridge, A.E. A review of New Zealand kauri (Agathis australis (D. Don) Lindl.): Its ecology, history, growth and potential for management for timber. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2010, 40, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, D.A. Communities and Ecosystems: Linking the Aboveground and Belowground Components; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R.; Taonui, R.; Wild, S. The concept of taonga in Māori culture: Insights for accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2012, 25, 1025–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.; Pockman, W.T.; Allen, C.D.; Breshears, D.D.; Cobb, N.; Kolb, T.; Plaut, J.; Sperry, J.; West, A.; Williams, D.G.; et al. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: Why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol. 2008, 178, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beever, R.E.; Waipara, N.W.; Ramsfield, T.D.; Dick, M.A.; Horner, I.J. Kauri (Agathis australis) under threat from Phytophthora? Phytophthoras For. Nat. Ecosyst. 2009, 74, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.T.; et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jactel, H.; Petit, J.; Desprez-Loustau, M.L.; Delzon, S.; Piou, D.; Battisti, A.; Koricheva, J. Drought effects on damage by forest insects and pathogens: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl, R.; Schelhaas, M.J.; Lexer, M.J. Unraveling the drivers of intensifying forest disturbance regimes in Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 2842–2852. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, G.G. Physiological Responses of Three Native Plants to Drought and Heatwave. Master’s Thesis, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cranston, B. Water-Use Patterns in New Zealand Kauri (Agathis Australis) Canopy and Stems Under Artificial Droughts. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meiforth, J.J.; Buddenbaum, H.; Hill, J.; Shepherd, J. Monitoring of canopy stress symptoms in New Zealand kauri trees analysed with AISA hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiforth, J.J.; Buddenbaum, H.; Hill, J.; Shepherd, J.D.; Dymond, J.R. Stress detection in New Zealand kauri canopies with WorldView-2 satellite and LiDAR data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.S.; Buddenbaum, H.; Leonardo, E.M.C.; Estarija, H.J.; Bown, H.E.; Gomez-Gallego, M.; Hartley, R.J.L.; Pearse, G.D.; Massam, P.; Wright, L.; et al. Monitoring biochemical limitations to photosynthesis in N- and P-limited radiata pine using plant functional traits quantified from hyperspectral imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 248, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.S.; Bartlett, M.; Soewarto, J.; de Silva, D.; Estarija, H.J.C.; Massam, P.; Cajes, D.; Yorston, W.; Graevskaya, E.; Dobbie, K. Previsual and early detection of myrtle rust on rose apple using indices derived from thermal imagery and visible-to-short-infrared spectroscopy. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Gonzalez-Dugo, V.; Berni, J.A.J. Fluorescence, temperature and narrow-band indices acquired from a UAV platform for water stress detection using a micro-hyperspectral imager and a thermal camera. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Clemente, R.; Hornero, A.; Mottus, M.; Peñuelas, J.; González-Dugo, V.; Jiménez, J.C.; Suárez, L.; Alonso, L.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Early diagnosis of vegetation health from high-resolution hyperspectral and thermal imagery: Lessons learned from empirical relationships and radiative transfer modelling. Curr. For. Rep. 2019, 5, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere, F.G.; Cudjoe, D.K.; Virlet, N.; Castle, M.; Riche, A.B.; Greche, L.; Mohareb, F.; Simms, D.; Mhada, M.; Hawkesford, M.J. Hyperspectral imaging for phenotyping plant drought stress and nitrogen interactions using multivariate modeling and machine learning techniques in wheat. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homolová, L.; Malenovský, Z.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; García-Santos, G.; Schaepman, M.E. Review of optical-based remote sensing for plant trait mapping. Ecol. Complex. 2013, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, M.J.B.; Main, R.; Watt, M.S.; Arpanaei, M.-M.; Patuawa, T. Early detection of water stress in kauri seedlings using multitemporal hyperspectral indices and inverted plant traits. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.S.; Jayathunga, S.; Hartley, R.J.L.; Pearse, G.D.; Massam, P.D.; Cajes, D.; Steer, B.S.C.; Estarija, H.J.C. Use of a ConsumerGrade UAV Laser Scanner to Identify Trees and Estimate Key Tree Attributes across a Point Density Range. Forests 2024, 15, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazdeyasna, S.; Arefin, M.S.; Fales, A.; Leavesley, S.J.; Pfefer, T.J.; Wang, Q. Evaluating normalization methods for robust spectral performance assessments of hyperspectral imaging cameras. Biosensors 2025, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Yang, Z.; Ren, J.; Jiang, M.; Ling, W.-K. Does normalization methods play a role for hyperspectral image classification? arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.02939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-387-98780-4. [Google Scholar]

- Main, R.; Felix, M.J.B.; Watt, M.S.; Hartley, R.J.L. Early detection of herbicide-induced tree stress using UAV-based multispectral and hyperspectral imagery. Forests 2025, 16, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodribb, T.J.; McAdam, S.A.M.; Jordan, G.J.; Martins, S.C.V. Conifer species adapt to low-rainfall climates by following one of two divergent pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14489–14493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, C.J.; Brodribb, T.J. Two measures of leaf capacitance: Insights into the water transport pathway and hydraulic conductance in leaves. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzer, F.C.; Johnson, D.M.; Lachenbruch, B.; McCulloh, K.A.; Woodruff, D.R. Xylem hydraulic safety margins in woody plants: Coordination of stomatal control of xylem tension with hydraulic capacitance. Funct. Ecol. 2009, 23, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, T.; Blatt, M.R. Stomatal size, speed, and responsiveness impact on photosynthesis and water use efficiency. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1556–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Delzon, S.; Clearwater, M.J.; Bellingham, P.J.; McGlone, M.S.; Richardson, S.J. Climatic limits of temperate rainforest tree species are explained by xylem embolism resistance among angiosperms but not among conifers. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macinnis-Ng, C.; Schwendenmann, L. Litterfall, carbon and nitrogen cycling in a southern hemisphere conifer forest dominated by kauri (Agathis australis) during drought. Plant Ecol. 2015, 216, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macinnis-Ng, C.; Wyse, S.; Veale, A.; Schwendenmann, L.; Clearwater, M. Sap flow of the southern conifer, Agathis australis during wet and dry summers. Trees 2016, 30, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.S.; Whitehead, D.; Richardson, B.; Mason, E.G.; Leckie, A.C. Modelling the influence of weed competition on the growth of young Pinus radiata at a dryland site. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 178, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Filella, I. Visible and near-infrared reflectance techniques for diagnosing plant physiological status. Trends Plant Sci. 1998, 3, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.; Chuvieco, E.; Nieto, H.; Aguado, I. Combining AVHRR and meteorological data for estimating live fuel moisture content. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3618–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.H.; Roberts, D.A.; Dennison, P.E. Mapping live fuel moisture with MODIS data: A multiple regression approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 4272–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbulsky, M.F.; Peñuelas, J.; Gamon, J.; Inoue, Y.; Filella, I. The photochemical reflectance index (PRI) and the remote sensing of leaf, canopy and ecosystem radiation use efficiencies: A review and meta-analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Garbulsky, M.F.; Filella, I. Photochemical reflectance index (PRI) and remote sensing of plant CO2 uptake. New Phytol. 2011, 191, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, R.C.; Hill, J.; Werner, W.; Buddenbaum, H.; Dash, J.P.; Gomez Gallego, M.; Rolando, C.A.; Pearse, G.D.; Hartley, R.; Estarija, H.J.; et al. Hyperspectral VNIR-spectroscopy and imagery as a tool for monitoring herbicide damage in wilding conifers. Biol. Invasions 2019, 21, 3395–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.; Serrano, L.; Surfus, J.S. The photochemical reflectance index: An optical indicator of photosynthetic radiation use efficiency across species, functional types, and nutrient levels. Oecologia 1997, 112, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripullone, F.; Rivelli, A.R.; Baraldi, R.; Guarini, R.; Guerrieri, R.; Magnani, F.; Peñuelas, J.; Raddi, S.; Borghetti, M. Effectiveness of the photochemical reflectance index to track photosynthetic activity over a range of forest tree species and plant water statuses. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.S.; Leonardo, E.M.C.; Estarija, H.J.; Massam, P.; de Silva, D.; O’Neill, R.; Lane, D.; McDougal, R.; Buddenbaum, H.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Long-term effects of water stress on hyperspectral remote sensing indicators in young radiata pine. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 502, 119707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.A.; Peñuelas, J.; Field, C.B. A narrow-waveband spectral index that tracks diurnal changes in photosynthetic efficiency. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 41, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacrés, J.; Fuentes, A.; Reszka, P.; Cheein, F.A. Retrieval of vegetation indices related to leaf water content from a single index: A case study of Eucalyptus globulus (Labill.) and Pinus radiata (D. Don.). Plants 2021, 10, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danson, F.M.; Bowyer, P. Estimating live fuel moisture content from remotely sensed reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 92, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipling, E.B. Physical and physiological basis for the reflectance of visible and near-infrared radiation from vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1970, 1, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.R.; Namken, L.N.; Oerther, G.F.; Brown, R.G. Estimating leaf water content by reflectance measurements. Agron. J. 1971, 63, 845–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Remote sensing of leaf water content in the near infrared. Remote Sens. Environ. 1980, 10, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourty, T.; Baret, F. Vegetation water and dry matter contents estimated from top-of-the-atmosphere reflectance data: A simulation study. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 61, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Datt, B. Remote sensing of water content in Eucalyptus leaves. Aust. J. Bot. 1999, 47, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wigneron, J.-P.; Xiao, Q.; Al-Yaari, A.; Wen, J.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Dupuy, J.-L.; Pimont, F.; Al Bitar, A.; Fernandez-Moran, R. Evaluation of microwave remote sensing for monitoring live fuel moisture content in the Mediterranean region. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 205, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, M.A.; Nova, J.P.G.; Marino, E.; Aponte, C.; Tomé, J.L.; Yáñez, L.; Madrigal, J.; Guijarro, M.; Hernando, C. Characterizing live fuel moisture content from active and passive sensors in a Mediterranean environment. Forests 2022, 13, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotzler, S.; Hill, J.; Buddenbaum, H.; Stoffels, J. The potential of EnMAP and Sentinel-2 data for detecting drought stress phenomena in deciduous forest communities. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 14227–14258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.P.; Reyes-Muñoz, P.; Morata, M.; Amin, E.; Tagliabue, G.; Panigada, C.; Hank, T.; Berger, K. Mapping landscape canopy nitrogen content from space using PRISMA data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einzmann, K.; Atzberger, C.; Pinnel, N.; Glas, C.; Böck, S.; Seitz, R.; Immitzer, M. Early detection of spruce vitality loss with hyperspectral data: Results of an experimental study in Bavaria, Germany. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 266, 112676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huete, A.R. A feedback based modification of the NDVI to minimize canopy background and atmospheric noise. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M. Evaluation of vegetation indices and a modified simple ratio for boreal applications. Can. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Pattey, E.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Strachan, I.B. Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of the Third Earth Resources Technology Satellite-1 Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 10–14 December 1973; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; Volume 1, pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roujean, J.-L.; Bréon, F.-M. Estimating PAR absorbed by vegetation from bidirectional reflectance measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 1995, 51, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of leaf-area index from quality of light on the forest floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broge, N.H.; Leblanc, E. Comparing prediction power and stability of broadband and hyperspectral vegetation indices for estimation of green leaf area index and canopy chlorophyll density. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.A.; Cibula, W.G.; Dell, T.R. Spectral reflectance characteristics and digital imagery of a pine needle blight in the Southeastern United States. Can. J. For. Res. 1996, 26, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Miller, J.R.; Noland, T.L.; Mohammed, G.H.; Sampson, P.H. Scaling-up and model inversion methods with narrowband optical indices for chlorophyll content estimation in closed forest canopies with hyperspectral data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 1491–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Keydan, G.P.; Merzlyak, M.N. Three-band model for noninvasive estimation of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and anthocyanin contents in higher plant leaves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L11402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, B. Remote sensing of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, chlorophyll A+B, and total carotenoid content in Eucalyptus leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 66, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Remote estimation of chlorophyll content in higher plant leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1997, 18, 2691–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, G.A. Spectral indices for estimating photosynthetic pigment concentrations: A test using senescent tree leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzlyak, M.N.; Gitelson, A.A.; Chivkunova, O.B.; Rakitin, V.Y. Non-destructive optical detection of pigment changes during leaf senescence and fruit ripening. Physiol. Plant. 1999, 106, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Baret, F.; Filella, I. Semi-empirical indices to assess carotenoids/chlorophyll a ratio from leaf spectral reflectance. Photosynthetica 1995, 31, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Daughtry, C.S.T.; Walthall, C.L.; Kim, M.S.; de Colstoun, E.B.; McMurtrey, J.E. Estimating corn leaf chlorophyll concentration from leaf and canopy reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Niu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Huang, W. Estimating chlorophyll content from hyperspectral vegetation indices: Modeling and validation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2008, 148, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Tremblay, N.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Dextraze, L. Integrated narrow-band vegetation indices for prediction of crop chlorophyll content for application to precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmann, J.E.; Rock, B.N.; Moss, D.M. Red edge spectral measurements from sugar maple leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1993, 14, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Miller, J.R.; Mohammed, G.H.; Noland, T.L. Chlorophyll fluorescence effects on vegetation apparent reflectance: I. Leaf-level measurements and model simulation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, S.R.; Eitel, J.U.H.; Vierling, L.A. Disentangling the relationships between plant pigments and the photochemical reflectance index reveals a new approach for remote estimation of carotenoid content. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Clemente, R.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M.; Suárez, L.; Morales, F.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Assessing structural effects on PRI for stress detection in conifer forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 2360–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Morales, A.; Testi, L.; Villalobos, F.J. Spatio-temporal patterns of chlorophyll fluorescence and physiological and structural indices acquired from hyperspectral imagery as compared with carbon fluxes measured with eddy covariance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 133, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlein, A.-K.; Rumpf, T.; Welke, P.; Dehne, H.-W.; Plümer, L.; Steiner, U.; Oerke, E.-C. Development of spectral indices for detecting and identifying plant diseases. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 128, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, R.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Lucena, C.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. High-resolution airborne hyperspectral and thermal imagery for early detection of Verticillium wilt of olive using fluorescence, temperature and narrow-band spectral indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 139, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Berjón, A.; Lopez-Lozano, R.; Miller, J.R.; Martín, P.; Cachorro, V.; González, M.R.; de Frutos, A. Assessing vineyard condition with hyperspectral indices: Leaf and canopy reflectance simulation in a row-structured discontinuous canopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 99, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Vegetation stress: An introduction to the stress concept in plants. J. Plant Physiol. 1996, 148, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Yacobi, Y.Z.; Schalles, J.F.; Rundquist, D.C.; Han, L.; Stark, R.; Etzion, D. Remote estimation of phytoplankton density in productive waters. Adv. Limnol. 2000, 55, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chappelle, E.W.; Kim, M.S.; McMurtrey, J.E. Ratio analysis of reflectance spectra (RARS): An algorithm for the remote estimation of the concentrations of chlorophyll A, chlorophyll B, and carotenoids in soybean leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 39, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NBHI | p Values | Rank | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| PRI570 | 0.604 | 0.548 | 0.952 | 0.541 | 0.155 | 0.488 | 0.342 | 0.033 | 0.019 | 0.014 | 1 |

| EVI | 0.406 | 0.089 | 0.922 | 0.869 | 0.192 | 0.644 | 0.259 | 0.368 | 0.022 | 0.013 | 2 |

| PSSRc | 0.155 | 0.224 | 0.662 | 0.238 | 0.514 | 0.658 | 0.894 | 0.108 | 0.098 | 0.249 | 3 |

| PSSRa | 0.654 | 0.258 | 0.665 | 0.401 | 0.243 | 0.763 | 0.093 | 0.456 | 0.112 | 0.239 | 4 |

| PSRI | 0.312 | 0.558 | 0.902 | 0.265 | 0.254 | 0.952 | 0.205 | 0.158 | 0.271 | 0.059 | 5 |

| LIC4 | 0.009 | 0.037 | 0.826 | 0.508 | 0.314 | 0.974 | 0.853 | 0.140 | 0.103 | 0.247 | 6 |

| RDVI | 0.482 | 0.115 | 0.994 | 0.235 | 0.257 | 0.935 | 0.078 | 0.544 | 0.331 | 0.092 | 7 |

| MCARI | 0.953 | 0.590 | 0.620 | 0.200 | 0.214 | 0.822 | 0.160 | 0.245 | 0.189 | 0.073 | 8 |

| TVI | 0.970 | 0.758 | 0.939 | 0.484 | 0.093 | 0.621 | 0.140 | 0.094 | 0.036 | 0.016 | 9 |

| CRI550 | 0.354 | 0.329 | 0.706 | 0.368 | 0.434 | 0.743 | 0.912 | 0.101 | 0.056 | 0.191 | 10 |

| B | 0.011 | 0.081 | 0.768 | 0.323 | 0.952 | 0.803 | 0.655 | 0.101 | 0.266 | 0.236 | 11 |

| MTVI1 | 0.869 | 0.756 | 0.984 | 0.425 | 0.128 | 0.640 | 0.185 | 0.098 | 0.085 | 0.038 | 12 |

| MCARI1 | 0.869 | 0.756 | 0.984 | 0.425 | 0.128 | 0.640 | 0.185 | 0.098 | 0.085 | 0.038 | 13 |

| G | 0.898 | 0.858 | 0.710 | 0.214 | 0.209 | 0.730 | 0.271 | 0.155 | 0.123 | 0.091 | 14 |

| TCA_OSA | 0.717 | 0.217 | 0.764 | 0.737 | 0.142 | 0.448 | 0.634 | 0.145 | 0.108 | 0.373 | 15 |

| RNIR_CRI550 | 0.368 | 0.333 | 0.707 | 0.377 | 0.451 | 0.735 | 0.947 | 0.104 | 0.065 | 0.210 | 16 |

| PRIm2 | 0.757 | 0.763 | 0.943 | 0.460 | 0.199 | 0.558 | 0.428 | 0.079 | 0.067 | 0.044 | 17 |

| CRI550_515 | 0.449 | 0.336 | 0.771 | 0.480 | 0.417 | 0.771 | 0.863 | 0.095 | 0.078 | 0.173 | 18 |

| CRI700 | 0.370 | 0.310 | 0.796 | 0.493 | 0.426 | 0.787 | 0.891 | 0.110 | 0.082 | 0.204 | 19 |

| TCARI | 0.850 | 0.361 | 0.763 | 0.726 | 0.138 | 0.441 | 0.626 | 0.144 | 0.106 | 0.365 | 20 |

| Week | Confusion Matrix (%) | Classification Statistics | Important Variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TN | FP | FN | TP | Prec. | Rec. | F1 | |||

| SiD | 1 | 24.9 | 25.1 | 14.8 | 35.2 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.64 | VOG2, PSNDc, TCA_OSA, PRICI, EVI |

| 2 | 23.9 | 26.1 | 13.9 | 36.1 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.64 | LIC7, CRI550_515, NPCI, LIC5, PRIm4 | |

| 3 | 23.0 | 27.0 | 31.6 | 18.4 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.39 | PSSRa, B, PSNDc, PRIm1, DCab | |

| 4 | 25.5 | 24.5 | 14.8 | 35.2 | 0.59 | 0.70 | 0.64 | PRIn, PSSRc, B, TCARI, NDVI | |

| 5 | 20.8 | 29.2 | 18.6 | 31.4 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.57 | PRICI, MCARI, PRI570, PSSRa, LIC7 | |

| 6 | 15.3 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 15.7 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.62 | CUR, EVI, MCARI, CAR, LIC4 | |

| 7 | 14.6 | 10.4 | 9.0 | 16.0 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.62 | PSSRc, MCARI1, PRI570, PRI515, PSSRa | |

| 8 | 29.8 | 20.2 | 17.6 | 32.4 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.63 | PRIm3, PSRI, PRIn, LIC4, CUR | |

| 9 | 36.7 | 13.3 | 18.5 | 31.5 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.66 | GM1, DCab, PRIm3, PRI570, HI | |

| 10 | 32.9 | 17.1 | 11.3 | 38.7 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.73 | PRIm4, DCab, HI, PSNDc, SIPI | |

| TS | 1–2 | 34.4 | 15.6 | 10.9 | 39.1 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.75 | EVI, CUR, R, PSNDc, BRI |

| 1–3 | 35.9 | 14.1 | 10.8 | 39.2 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.76 | MCARI, R, PSNDc, TCA_OSA, LIC7 | |

| 1–4 | 36.8 | 13.2 | 9.4 | 40.6 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.78 | PSSRc, HI, LIC7, NDVI, VOG3 | |

| 1–5 | 37.3 | 12.7 | 10.8 | 39.2 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 | LIC6, PSSRb, PSRI, PRIm4, PRIm1 | |

| 1–6 | 38.8 | 11.2 | 8.3 | 41.7 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.81 | TCA_OSA, MCARI, PRIn, LIC5, PRIm4 | |

| 1–7 | 38.1 | 11.9 | 8.5 | 41.5 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.80 | PRICI, TCARI, PSNDc, PSSRb, SR | |

| 1–8 | 41.5 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 42.4 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.84 | MTVI1, PRIm, LIC7, PRI570, VOG3 | |

| 1–9 | 44.1 | 5.9 | 9.9 | 40.1 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.84 | LIC5, PRIn, VOG3, PRI570, PSNDc | |

| 1–10 | 42.1 | 7.9 | 4.3 | 45.7 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.88 | PRI570, PRIm3, GM1, TCA_OSA, LIC5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Felix, M.J.B.; Main, R.; Watt, M.S.; Patuawa, T. Probing Early and Long-Term Drought Responses in Kauri Using Canopy Hyperspectral Imaging. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233914

Felix MJB, Main R, Watt MS, Patuawa T. Probing Early and Long-Term Drought Responses in Kauri Using Canopy Hyperspectral Imaging. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233914

Chicago/Turabian StyleFelix, Mark Jayson B., Russell Main, Michael S. Watt, and Taoho Patuawa. 2025. "Probing Early and Long-Term Drought Responses in Kauri Using Canopy Hyperspectral Imaging" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233914

APA StyleFelix, M. J. B., Main, R., Watt, M. S., & Patuawa, T. (2025). Probing Early and Long-Term Drought Responses in Kauri Using Canopy Hyperspectral Imaging. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233914