Integrating UAV Multi-Temporal Imagery and Machine Learning to Assess Biophysical Parameters of Douro Grapevines

Highlights

- UAV multispectral data combined with machine learning enabled the estimation of grapevine biophysical parameters, including LAI, pruning wood biomass, and yield.

- Geometric features, such as canopy area and volume, improved model accuracy and reduced the number of predictors, while the integration of spectral and geometric data improved prediction robustness across different phenological stages.

- UAV-based monitoring can be applied in different grapevine varieties without cultivar-specific calibration, providing a non-invasive tool for vineyard assessment.

- Identifying the most informative features and suitable acquisition periods supports more accurate decisions in vineyard management, including pruning, canopy control, and yield estimation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

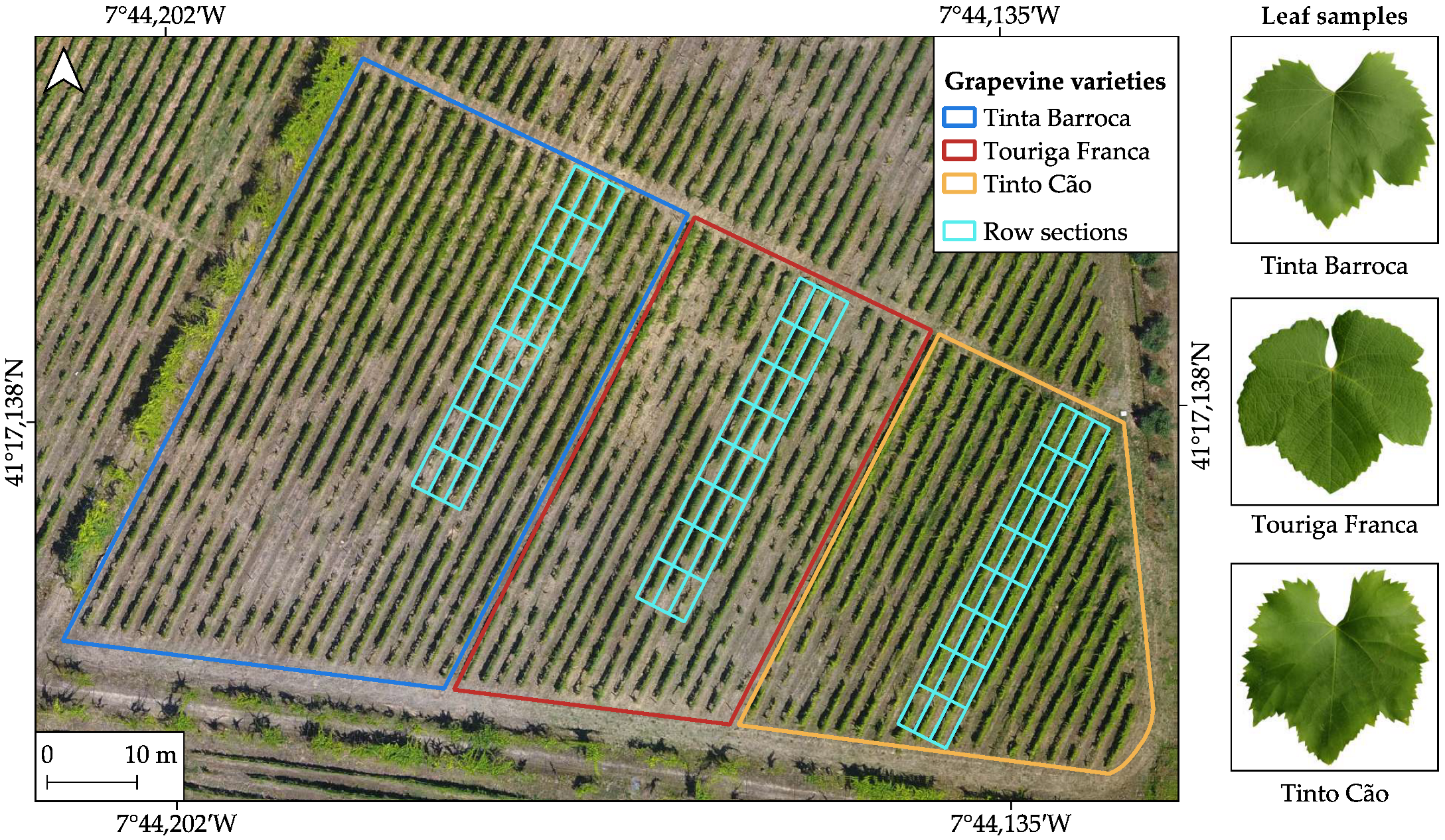

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2.1. Field Data

2.2.2. UAV Data Acquisition and Photogrammetric Processing

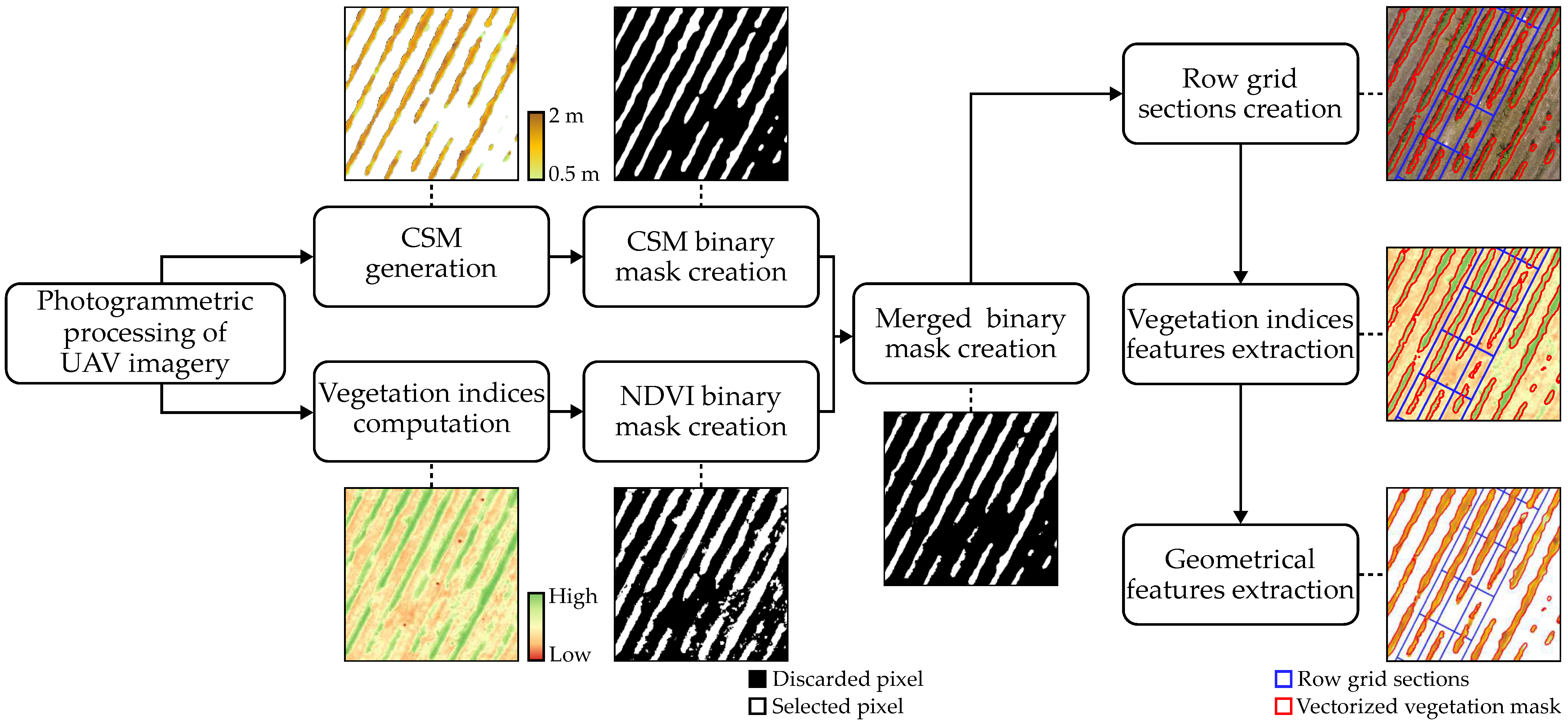

2.3. Feature Extraction from UAV-Based Data

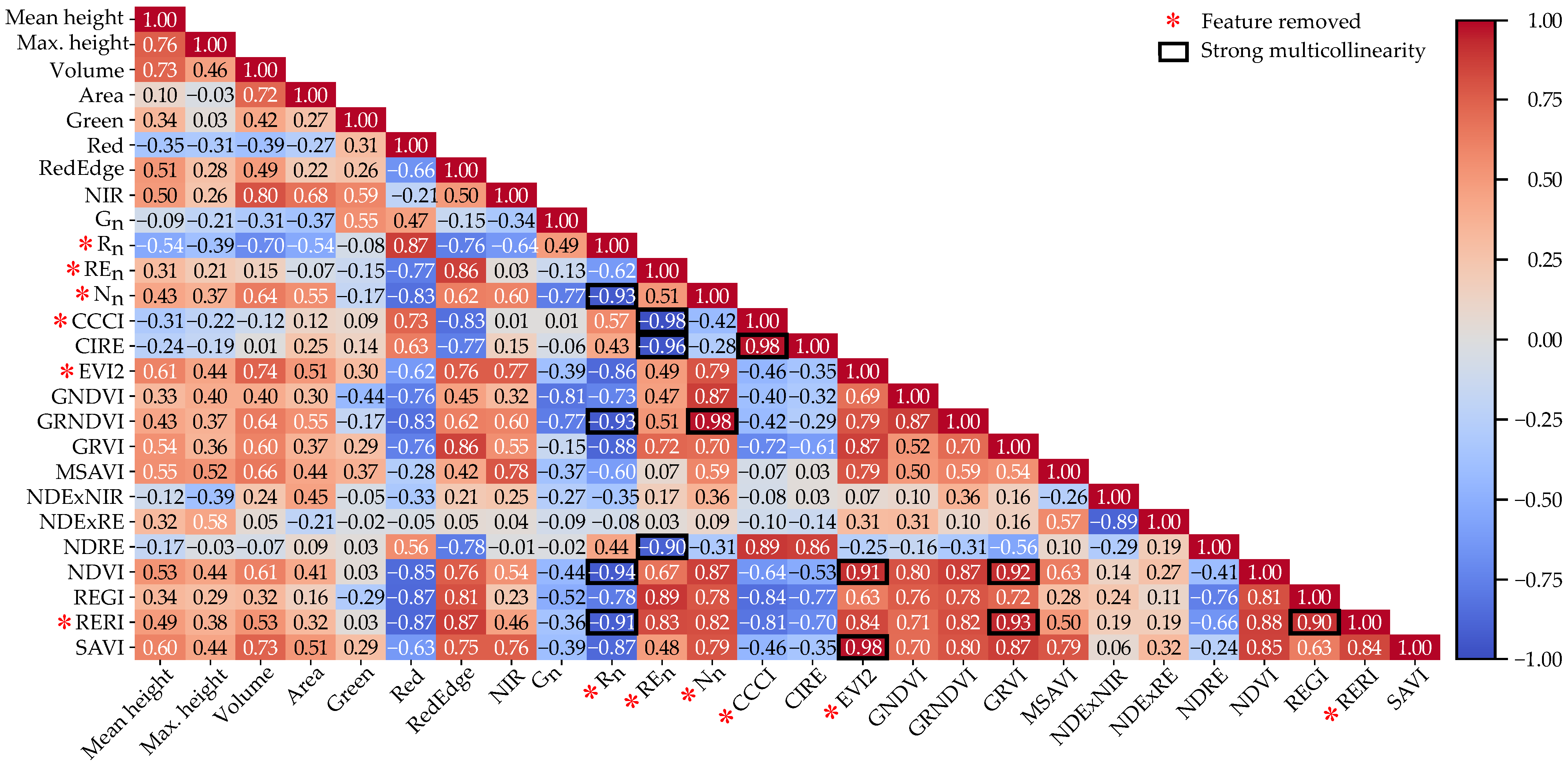

2.4. Features Selection

2.5. Modeling LAI, Pruning Wood Biomass, and Yield

2.5.1. Multiple Linear Regression

2.5.2. Machine Learning

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Model Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Data Characterization

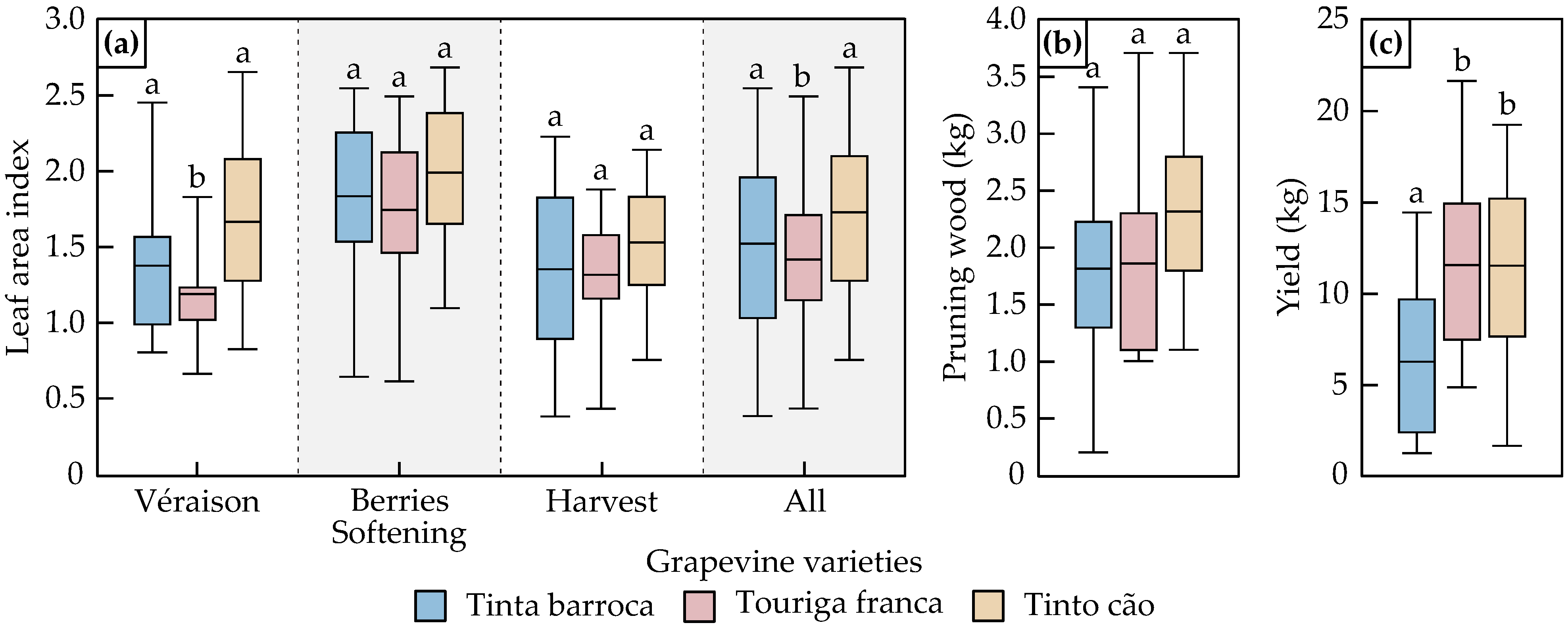

3.1.1. Leaf Area Index, Pruning Wood Biomass and Yield

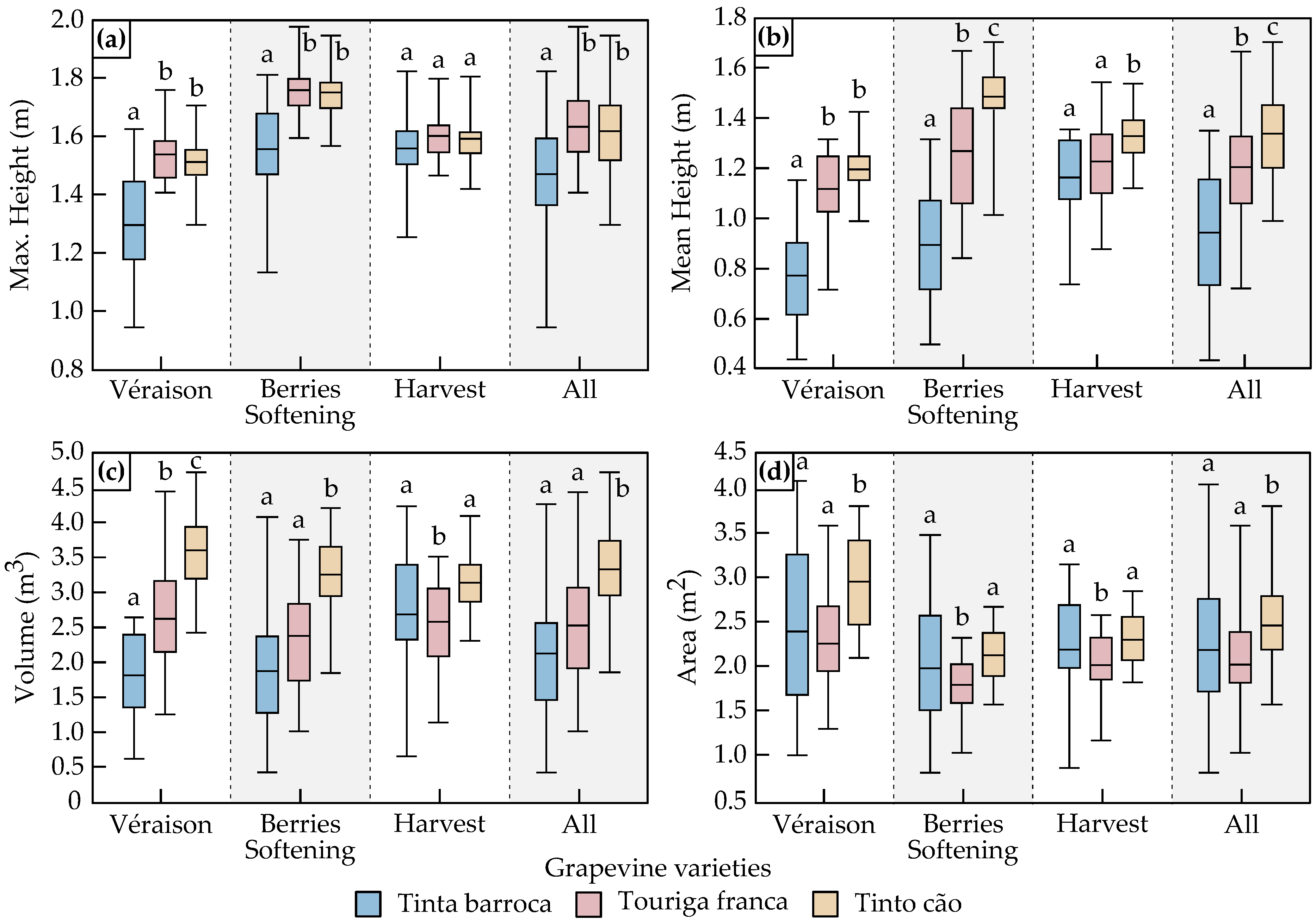

3.1.2. Geometrical Features

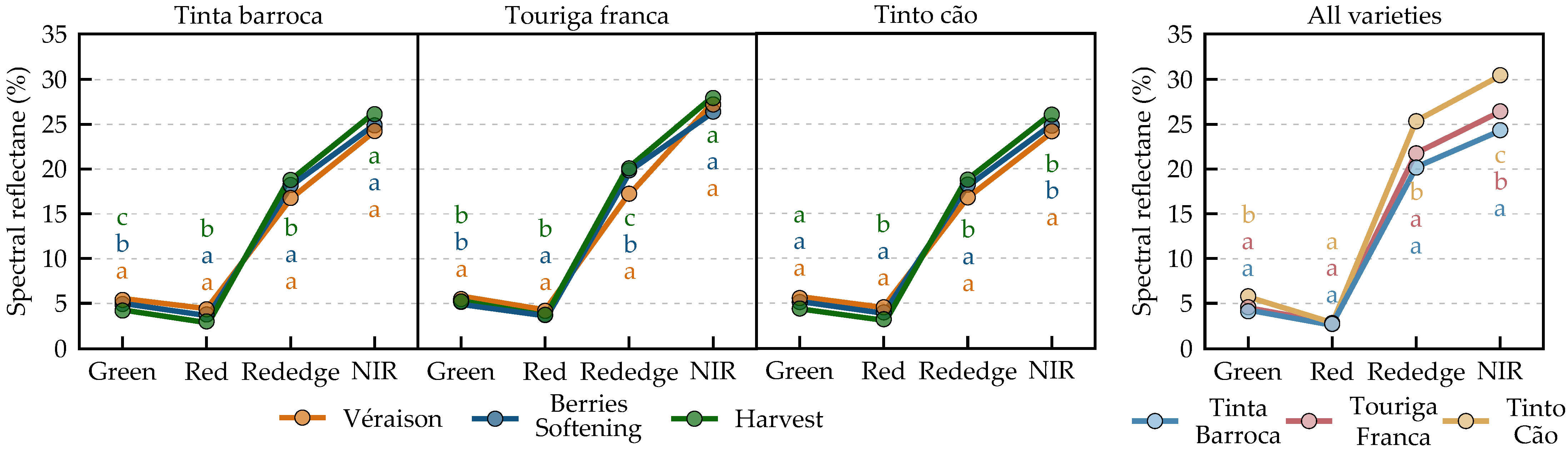

3.1.3. Spectral Features

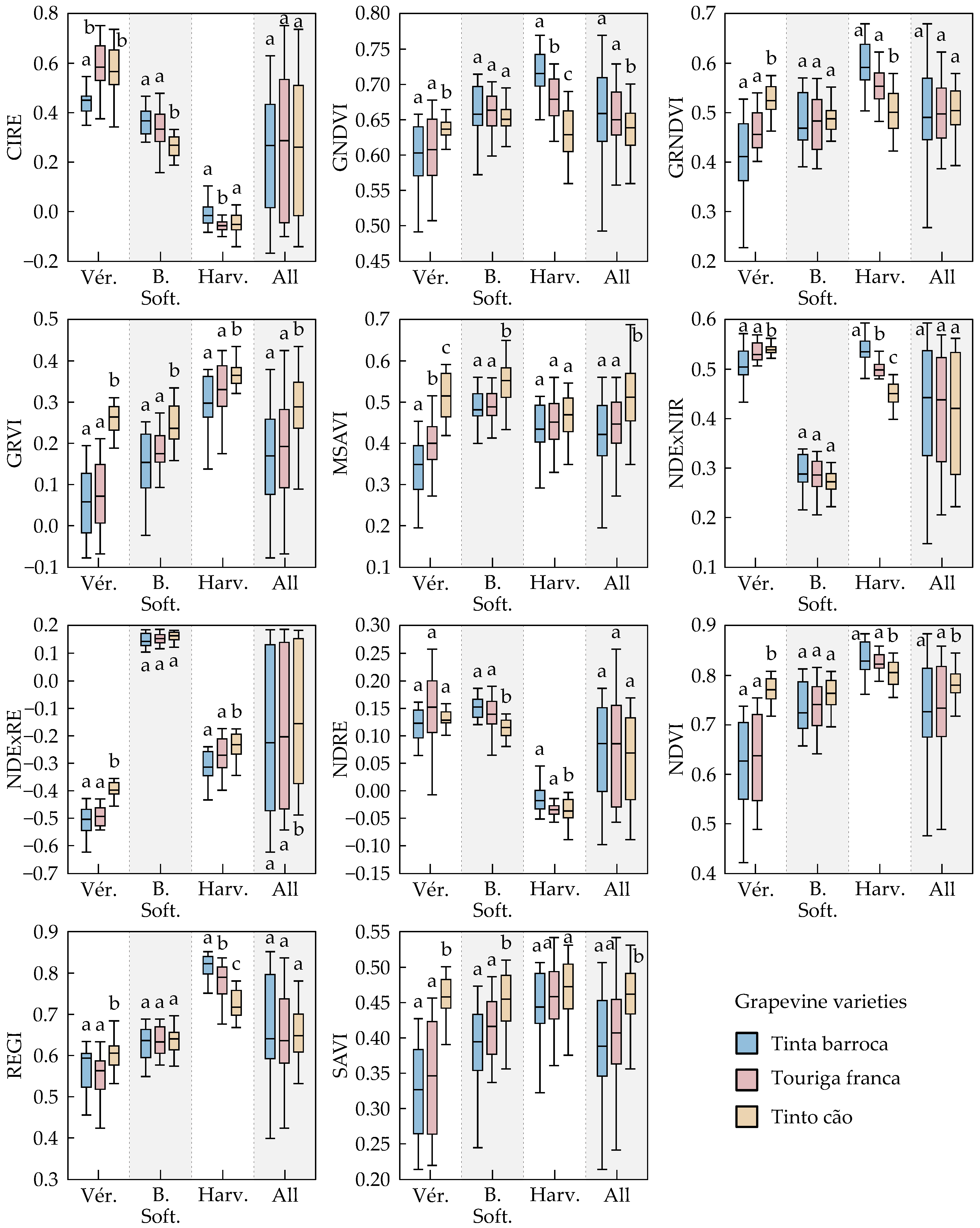

3.2. Correlation Between Predictor and Response Variables

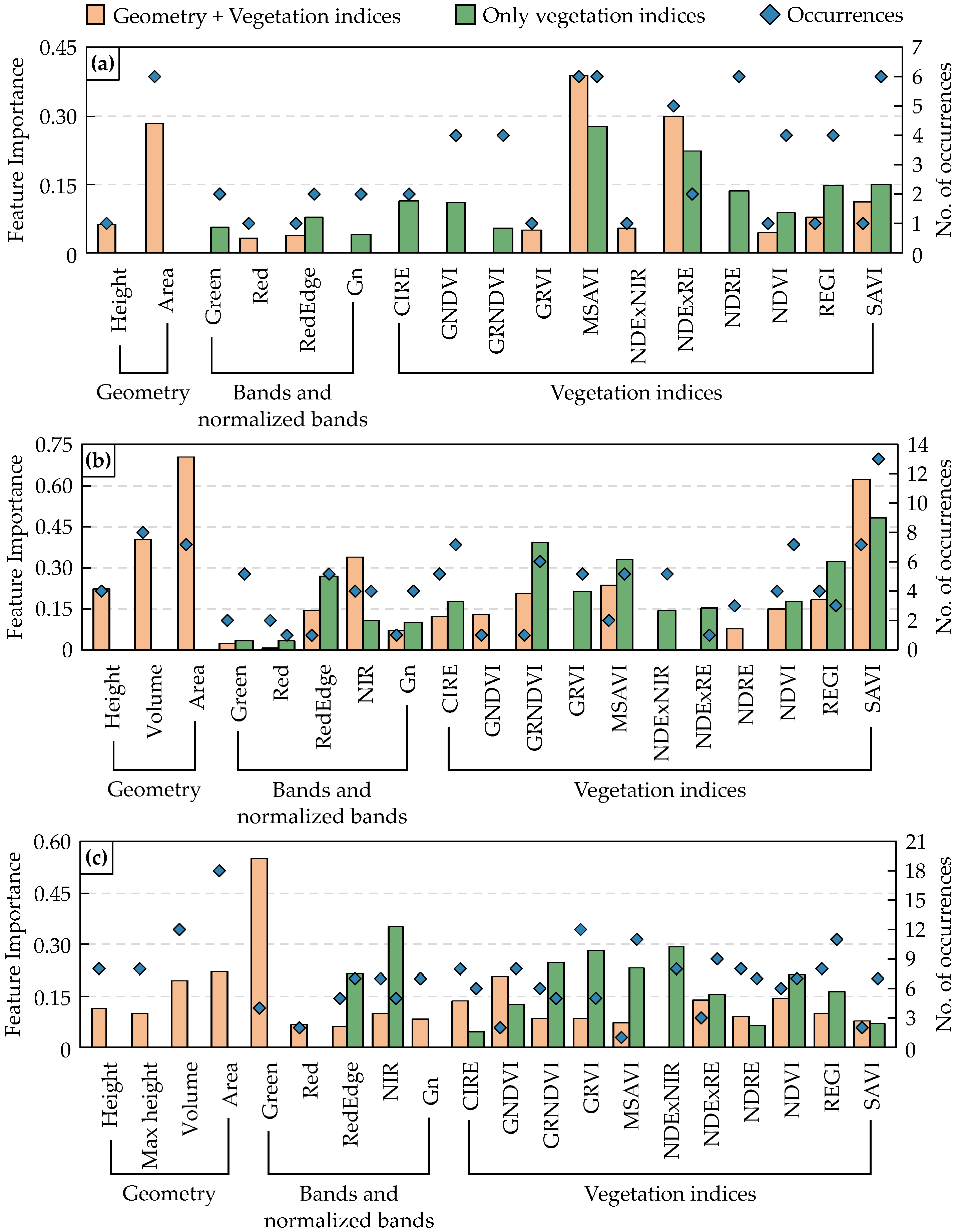

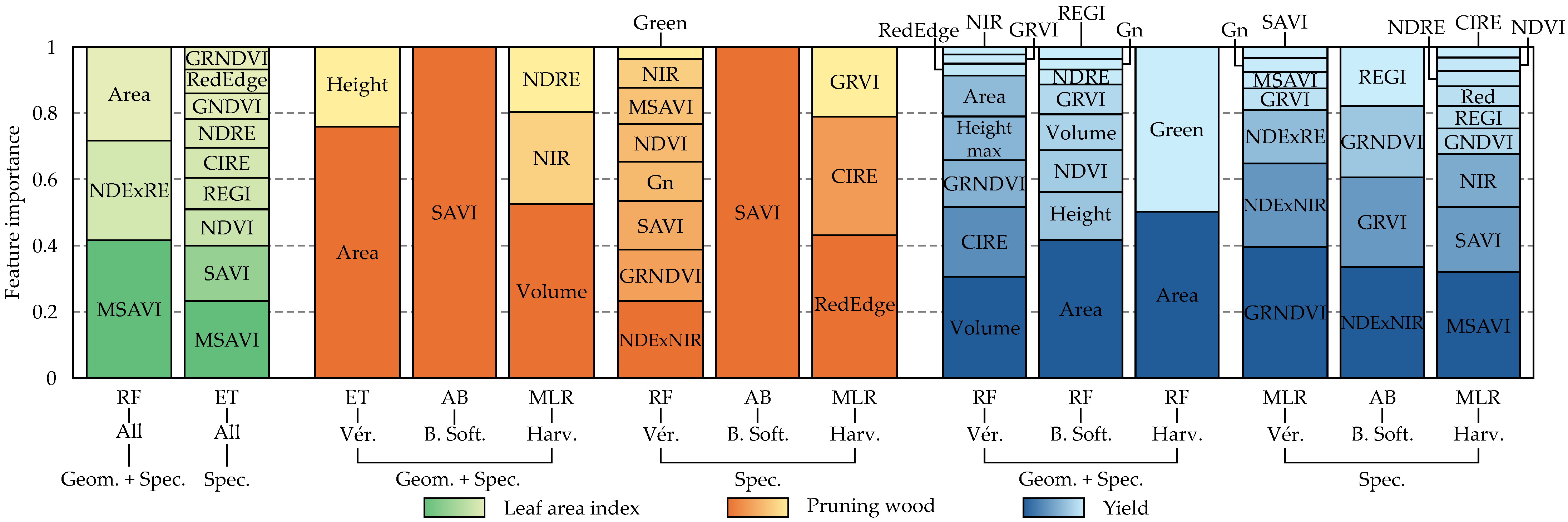

3.3. Feature Importance Across Selected Models

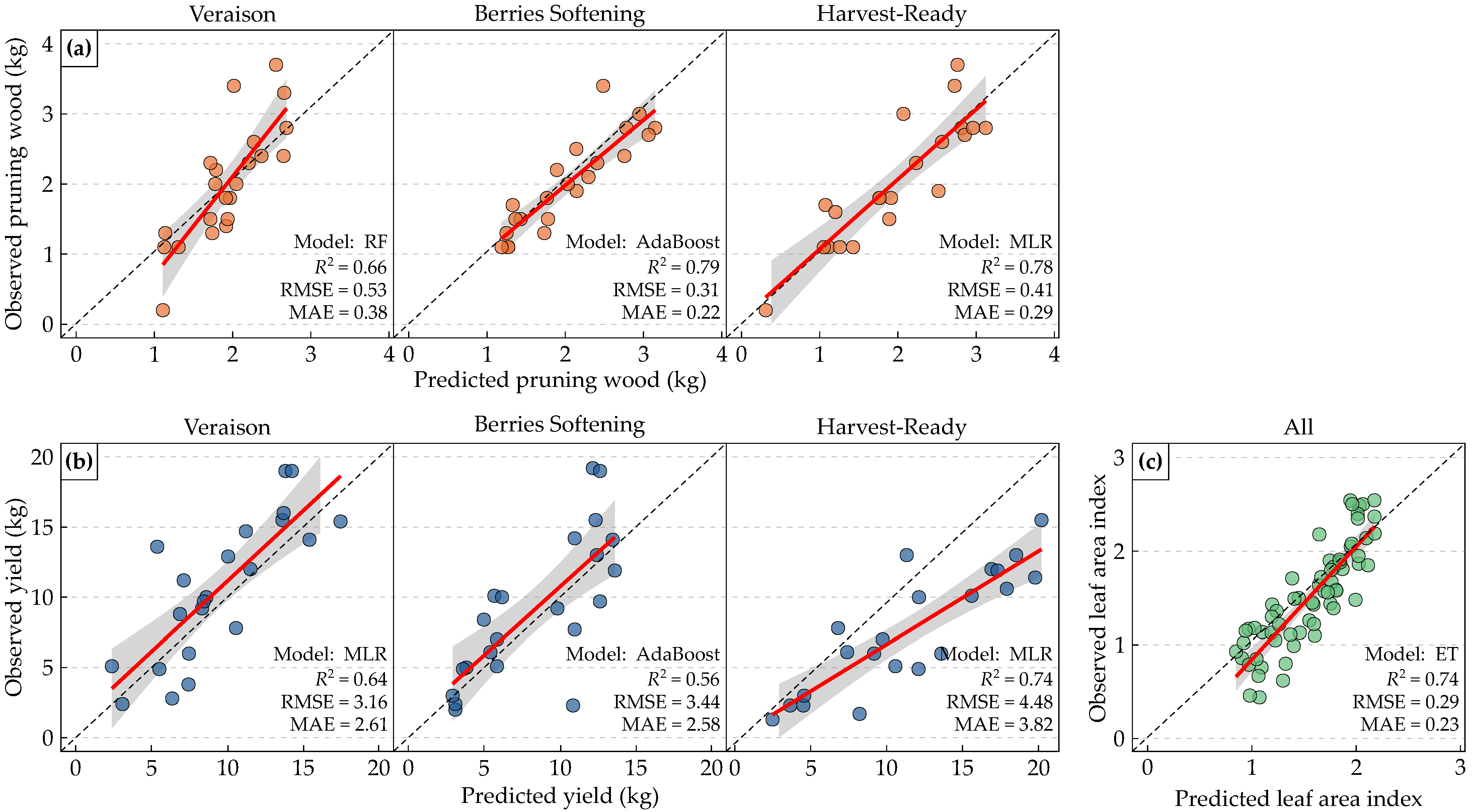

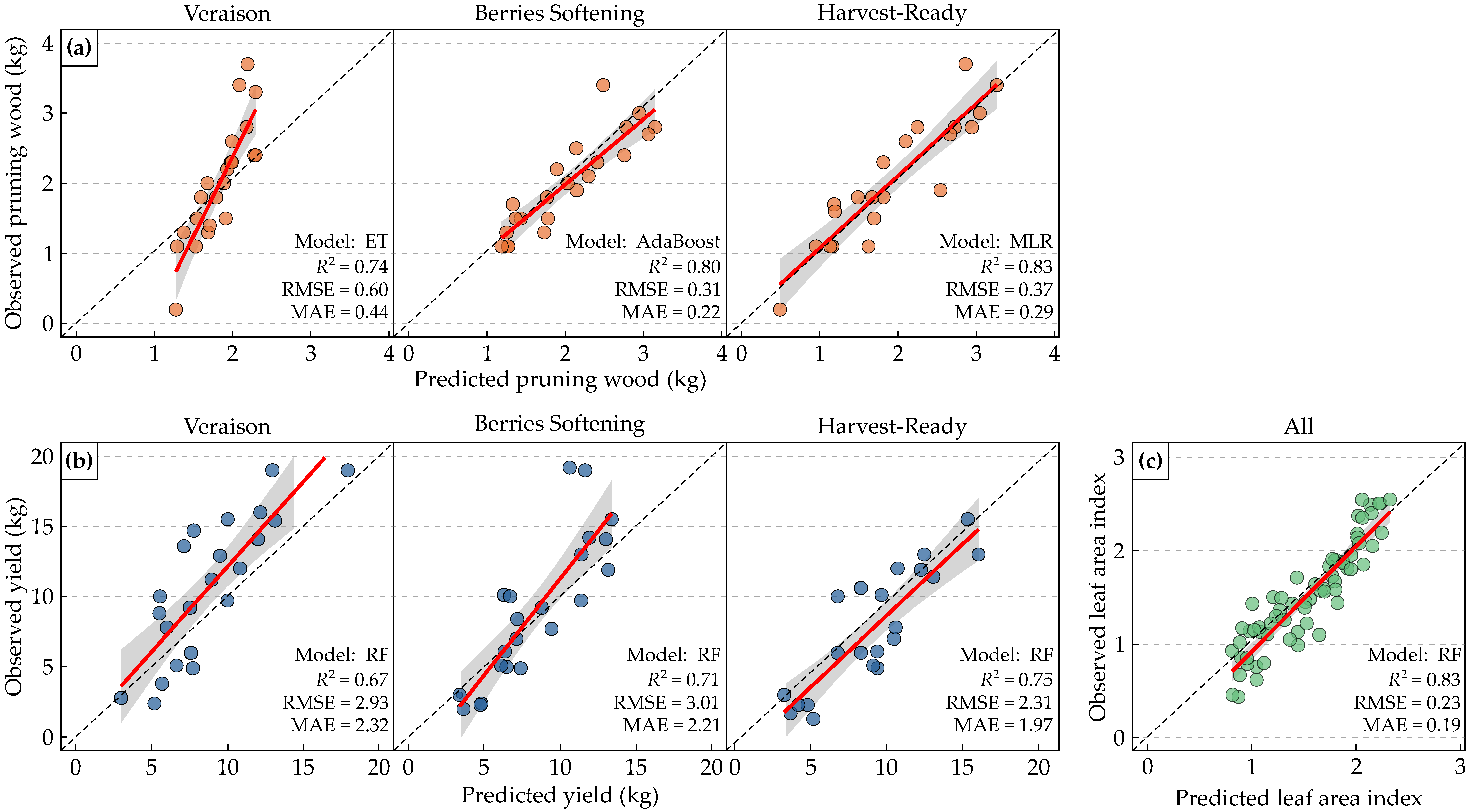

3.4. Best Performing Models

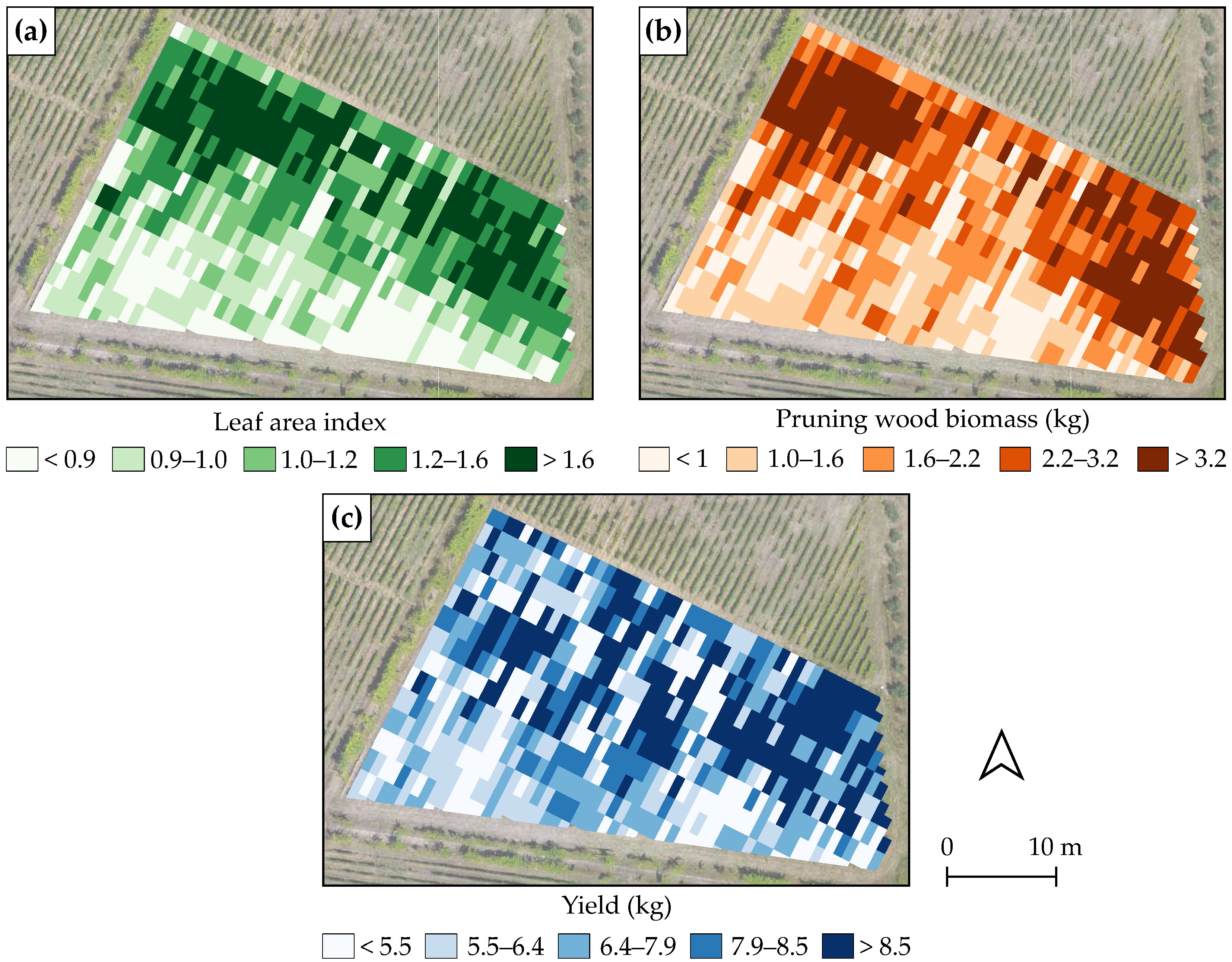

3.5. Spatial Distribution of Estimated Leaf Area Index, Pruning Wood Biomass, and Yield

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance and Feature Relevance

4.2. Temporal Dynamics Across Phenological Stages

4.3. Contribution of Geometric Features

4.4. Methodological Considerations

4.5. Implications for Viticulture and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Equation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Canopy Chlorophyll Content Index | [83] | |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index 2 | [93] | |

| Green Normalized Vegetation Index | [35] | |

| Green Red Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [94] | |

| Green Red Vegetation Index | [95] | |

| Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | [96] | |

| Normalized Difference Excess Near-Infrared | [97] | |

| Normalized Difference Excess Red Edge | [97] | |

| Normalized Difference Red Edge | [34] | |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [21] | |

| Red Edge Chlorophyll Index | [98] | |

| Red Edge Green Index | [99] | |

| Red Edge Rouge Index | [99] | |

| Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | [73] |

| Predictive Variable | Phen. Stage | Model | Data Scale | Stepwise Type | Number of Features | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAI | All | RF | Linear | Forward | 3 | 0.83 | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| XGBoost | Linear | Forward | 3 | 0.79 | 0.25 | 0.20 | ||

| GBoost | Linear | Forward | 3 | 0.80 | 0.24 | 0.20 | ||

| AdaBoost | Linear | Backward | 10 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.23 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Linear | Forward | 3 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.19 | ||

| MLR | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.80 | 0.24 | 0.19 | ||

| Pruning wood | Vér. | RF | Linear | Forward | 2 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.38 |

| XGBoost | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.46 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.43 | ||

| AdaBoost | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.40 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.44 | ||

| MLR | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.43 | ||

| B. soft. | RF | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.77 | 0.34 | 0.24 | |

| XGBoost | Linear | Forward | 1 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.36 | ||

| GBoost | Linear | Forward | 1 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.24 | ||

| AdaBoost | Linear | Forward | 1 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.22 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Backward | 6 | 0.78 | 0.34 | 0.26 | ||

| MLR | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.79 | 0.31 | 0.23 | ||

| Harv. | RF | Linear | Backward | 9 | 0.81 | 0.42 | 0.34 | |

| XGBoost | Linear | Forward | 3 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 0.45 | ||

| GBoost | Linear | Forward | 3 | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.36 | ||

| AdaBoost | Linear | Backward | 9 | 0.76 | 0.47 | 0.38 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Linear | Forward | 3 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 0.45 | ||

| MLR | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.29 | ||

| Yield | Vér. | RF | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.67 | 2.93 | 2.32 |

| XGBoost | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.68 | 3.82 | 3.13 | ||

| GBoost | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.64 | 4.01 | 3.36 | ||

| AdaBoost | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.63 | 3.23 | 2.60 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.68 | 3.43 | 2.87 | ||

| MLR | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.35 | 4.76 | 3.27 | ||

| B. soft. | RF | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.71 | 3.01 | 2.21 | |

| XGBoost | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.63 | 3.23 | 2.29 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.61 | 3.48 | 2.53 | ||

| AdaBoost | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.46 | 3.98 | 3.10 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.66 | 3.57 | 2.86 | ||

| MLR | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.46 | 4.46 | 3.54 | ||

| Harv. | RF | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.75 | 2.31 | 1.97 | |

| XGBoost | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.59 | 3.19 | 2.54 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.70 | 2.65 | 2.16 | ||

| AdaBoost | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.64 | 2.85 | 2.35 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Backward | 11 | 0.65 | 3.06 | 2.67 | ||

| MLR | Log | Backward | 11 | 0.45 | 4.96 | 3.66 |

| Predictive Variable | Phen. Stage | Model | Data Scale | Stepwise Type | Number of Features | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAI | All | RF | Linear | Forward | 4 | 0.73 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| XGBoost | Linear | Forward | 4 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.23 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.24 | ||

| AdaBoost | Linear | Backward | 9 | 0.71 | 0.30 | 0.24 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Linear | Backward | 9 | 0.74 | 0.29 | 0.23 | ||

| MLR | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.24 | ||

| Pruning wood | Vér. | RF | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.38 |

| XGBoost | Linear | Backward | 8 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.43 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.45 | ||

| AdaBoost | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.39 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Forward | 2 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.52 | ||

| MLR | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.59 | ||

| B. soft. | RF | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.77 | 0.34 | 0.24 | |

| XGBoost | Linear | Backward | 1 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.36 | ||

| GBoost | Linear | Forward | 1 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.24 | ||

| AdaBoost | Linear | Forward | 1 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.22 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 0.32 | ||

| MLR | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.79 | 0.31 | 0.23 | ||

| Harv. | RF | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.42 | |

| XGBoost | Linear | Forward | 1 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.43 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Backward | 8 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.41 | ||

| AdaBoost | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.40 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.40 | ||

| MLR | Log | Forward | 3 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.29 | ||

| Yield | Vér. | RF | Log | Backward | 7 | 0.54 | 4.37 | 3.61 |

| XGBoost | Linear | Forward | 1 | 0.50 | 4.02 | 3.51 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Backward | 7 | 0.42 | 5.16 | 4.30 | ||

| AdaBoost | Log | Backward | 7 | 0.39 | 4.86 | 4.00 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Linear | Backward | 1 | 0.38 | 4.12 | 3.48 | ||

| MLR | Log | Backward | 7 | 0.64 | 3.16 | 2.61 | ||

| B. soft. | RF | Log | Backward | 4 | 0.53 | 3.70 | 2.98 | |

| XGBoost | Log | Backward | 4 | 0.49 | 3.85 | 3.00 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Backward | 4 | 0.48 | 4.08 | 3.27 | ||

| AdaBoost | Log | Backward | 4 | 0.56 | 3.44 | 2.58 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Forward | 1 | 0.47 | 4.16 | 3.28 | ||

| MLR | Linear | Backward | 5 | 0.17 | 5.63 | 4.68 | ||

| Harv. | RF | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.62 | 3.12 | 2.88 | |

| XGBoost | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.57 | 4.13 | 3.41 | ||

| GBoost | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.57 | 3.49 | 3.00 | ||

| AdaBoost | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.57 | 3.36 | 2.92 | ||

| ExtraTrees | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.57 | 3.31 | 2.99 | ||

| MLR | Log | Backward | 9 | 0.74 | 4.48 | 3.82 |

References

- Paiola, A.; Assandri, G.; Brambilla, M.; Zottini, M.; Pedrini, P.; Nascimbene, J. Exploring the potential of vineyards for biodiversity conservation and delivery of biodiversity-mediated ecosystem services: A global-scale systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Costa, R.; Santos, J. Modelling the terroir of the Douro demarcated region, Portugal. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Zaragoza, Spain, 18–22 June 2018; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 50, p. 02009. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, J.B.; Brinca, P.; Gonçalves, M.J. Setor do Vinho-Avaliação de Impacto Socioeconómico em Portugal; Technical Report; Nova School of Business & Economics: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, A.L.; Fernão-Pires, M.J.; Bianchi-de Aguiar, F. Portuguese vines and wines: Heritage, quality symbol, tourism asset. Cienc. E Tec. Vitivinic. 2018, 33, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, J.M.; Jámbor, A. The global competitiveness of European wine producers. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2076–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.; Teixeira-Santos, M.; Brazaão, J.; Fevereiro, P.; Eiras-Dias, J.E. Portuguese Vitis vinifera L. germplasm: Accessing its diversity and strategies for conservation. In The Mediterranean Genetic Code-Grapevine and Olive; Intechopen: London, UK, 2013; pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga, H.; de Cortázar Atauri, I.G.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Santos, J.A. Viticulture in Portugal: A review of recent trends and climate change projections. OENO One 2017, 51, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Darriet, P. The impact of climate change on viticulture and wine quality. J. Wine Econ. 2016, 11, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matese, A.; Toscano, P.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Genesio, L.; Vaccari, F.P.; Primicerio, J.; Belli, C.; Zaldei, A.; Bianconi, R.; Gioli, B. Intercomparison of UAV, aircraft and satellite remote sensing platforms for precision viticulture. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 2971–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librán-Embid, F.; Klaus, F.; Tscharntke, T.; Grass, I. Unmanned aerial vehicles for biodiversity-friendly agricultural landscapes—A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréda, N.J. Ground-based measurements of leaf area index: A review of methods, instruments and current controversies. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 2403–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonckheere, I.; Fleck, S.; Nackaerts, K.; Muys, B.; Coppin, P.; Weiss, M.; Baret, F. Review of methods for in situ leaf area index determination: Part I. Theories, sensors and hemispherical photography. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 121, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, A.; Noory, H.; Vazifedoust, M. Improving crop yield estimation by assimilating LAI and inputting satellite-based surface incoming solar radiation into SWAP model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 250, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, W.; Tian, Y. Integrating remotely sensed leaf area index and leaf nitrogen accumulation with RiceGrow model based on particle swarm optimization algorithm for rice grain yield assessment. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2014, 8, 083674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Rajib, A.; Negahban-Azar, M.; Shirmohammadi, A.; Srivastava, P. Improved agricultural Water management in data-scarce semi-arid watersheds: Value of integrating remotely sensed leaf area index in hydrological modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, R.; Ortega, J.F.; Hernández, D.; Moreno, M.Á. Characterization of Vitis vinifera L. canopy using unmanned aerial vehicle-based remote sensing and photogrammetry techniques. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munitz, S.; Schwartz, A.; Netzer, Y. Water consumption, crop coefficient and leaf area relations of a Vitis vinifera cv.‘Cabernet Sauvignon’vineyard. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 219, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Tozzini, L.; Rallo, G.; Primicerio, J.; Moriondo, M.; Palai, G.; Gucci, R. Estimating biophysical and geometrical parameters of grapevine canopies (‘Sangiovese’) by an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) and VIS-NIR cameras. Vitis 2017, 56, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.; Lucieer, A.; Watson, C. Development of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) for hyper resolution vineyard mapping based on visible, multispectral, and thermal imagery. In Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10–15 April 2011; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tondriaux, C.; Costard, A.; Bertin, C.; Duthoit, S.; Hourdel, J.; Rousseau, J. How can remote sensing techniques help monitoring the vine and maximize the terroir potential? In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Zaragoza, Spain, 18–22 June 2018; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 50, p. 02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS; NASA Special Publication; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; Volume 351, pp. 309–317.

- Puig-Sirera, À.; Antichi, D.; Warren Raffa, D.; Rallo, G. Application of remote sensing techniques to discriminate the effect of different soil management treatments over rainfed vineyards in chianti terroir. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Palai, G.; Tozzini, L.; D’Onofrio, C.; Gucci, R. The role of LAI and leaf chlorophyll on NDVI estimated by UAV in grapevine canopies. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 322, 112398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Torres-Rua, A.F.; Aboutalebi, M.; White, W.A.; Anderson, M.; Kustas, W.P.; Agam, N.; Alsina, M.M.; Alfieri, J.; Hipps, L.; et al. LAI estimation across California vineyards using sUAS multi-seasonal multi-spectral, thermal, and elevation information and machine learning. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 731–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisperakis, I.; Stentoumis, C.; Grammatikopoulos, L.; Karantzalos, K. Leaf area index estimation in vineyards from UAV hyperspectral data, 2D image mosaics and 3D canopy surface models. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 40, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilniyaz, O.; Du, Q.; Shen, H.; He, W.; Feng, L.; Azadi, H.; Kurban, A.; Chen, X. Leaf area index estimation of pergola-trained vineyards in arid regions using classical and deep learning methods based on UAV-based RGB images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 107723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchard-Levine, V.; Guerra, J.G.; Borra-Serrano, I.; Nieto, H.; Mesías-Ruiz, G.; Dorado, J.; de Castro, A.; Herrezuelo, M.; Mary, B.; Aguirre, E.; et al. Evaluating the utility of combining high resolution thermal, multispectral and 3D imagery from unmanned aerial vehicles to monitor water stress in vineyards. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2447–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutalebi, M.; Torres-Rua, A.F.; McKee, M.; Kustas, W.P.; Nieto, H.; Alsina, M.M.; White, A.; Prueger, J.H.; McKee, L.; Alfieri, J.; et al. Incorporation of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) point cloud products into remote sensing evapotranspiration models. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, S.; Poblete-Echeverría, C.; Rubio, J.A.; Barajas, E. Estimation of Leaf Area Index in vineyards by analysing projected shadows using UAV imagery. OENO One 2021, 55, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, J.; Ramírez-Pérez, P.; León-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; López-Granados, F. Estimation of vineyard vegetative growth: Analysis of 3D point cloud from unmanned aerial vehicle imagery. Asoc. Interprofesional Para El Desarro. Agrar. 2022, 118, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leolini, L.; Bregaglio, S.; Ginaldi, F.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; Di Gennaro, S.; Matese, A.; Maselli, F.; Caruso, G.; Palai, G.; Bajocco, S.; et al. Use of remote sensing-derived fPAR data in a grapevine simulation model for estimating vine biomass accumulation and yield variability at sub-field level. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, M.; Sanz-Ablanedo, E.; Pereira-Obaya, D.; Rodríguez-Pérez, J.R. Vineyard pruning weight prediction using 3D point clouds generated from UAV imagery and structure from motion photogrammetry. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.V.; Catania, P.; Micciche, D.; Pisciotta, A.; Vallone, M.; Orlando, S. Assessment of vineyard vigour and yield spatio-temporal variability based on UAV high resolution multispectral images. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 231, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.; Clarke, T.; Richards, S.; Colaizzi, P.; Haberland, J.; Kostrzewski, M.; Waller, P.; Choi, C.; Riley, E.; Thompson, T.; et al. Coincident detection of crop water stress, nitrogen status and canopy density using ground based multispectral data. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Bloomington, MN, USA, 16–19 July 2000; Volume 1619. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastonchi, L.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Toscano, P.; Matese, A. Comparison between satellite and ground data with UAV-based information to analyse vineyard spatio-temporal variability: This article is published in cooperation with the XIIIth International Terroir Congress November 17–18 2020, Adelaide, Australia. Guest editors: Cassandra Collins and Roberta De Bei. OENO One 2020, 54, 919–934. [Google Scholar]

- Kasimati, A.; Psiroukis, V.; Darra, N.; Kalogrias, A.; Kalivas, D.; Taylor, J.; Fountas, S. Investigation of the similarities between NDVI maps from different proximal and remote sensing platforms in explaining vineyard variability. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1220–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, G.; Matese, A.; Ulrici, A.; Calvini, R.; Berton, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F. Automated yield prediction in vineyard using RGB images acquired by a UAV prototype platform. OENO One 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, J.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F.J.; Santesteban, L.G.; Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; Oneka, O.; Villa-Llop, A.; Loidi, M.; López-Granados, F. Grape cluster detection using UAV photogrammetric point clouds as a low-cost tool for yield forecasting in vineyards. Sensors 2021, 21, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codes-Alcaraz, A.M.; Furnitto, N.; Sottosanti, G.; Failla, S.; Puerto, H.; Rocamora-Osorio, C.; Freire-García, P.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M. Automatic Grape Cluster Detection Combining YOLO Model and Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, P.; Ortega, J.F.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Moreno, M.A.; Ramírez, J.M.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Ballesteros, R. Yield estimations in a vineyard based on high-resolution spatial imagery acquired by a UAV. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 224, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šupčík, A.; Milics, G.; Matečnỳ, I. Predicting Grape Yield with Vine Canopy Morphology Analysis from 3D Point Clouds Generated by UAV Imagery. Drones 2024, 8, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Burnside, N.G.; Brolly, M.; Joyce, C.B. Investigating the Role of Cover-Crop Spectra for Vineyard Monitoring from Airborne and Spaceborne Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilović, M.; Jovanović, D.; Božović, P.; Benka, P.; Govedarica, M. Vineyard Zoning and Vine Detection Using Machine Learning in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchard-Levine, V.; Nieto, H.; Kustas, W.P.; Gao, F.; Alfieri, J.G.; Prueger, J.H.; Hipps, L.E.; Bambach-Ortiz, N.; McElrone, A.J.; Castro, S.J.; et al. Application of a remote-sensing three-source energy balance model to improve evapotranspiration partitioning in vineyards. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magarreiro, C.; Gouveia, C.M.; Barroso, C.M.; Trigo, I.F. Modelling of wine production using land surface temperature and FAPAR—The case of the Douro Wine Region. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, B. Uav data as an alternative to field sampling to monitor vineyards using machine learning based on uav/sentinel-2 data fusion. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenghua, Y.; Tongyu, X.; Wen, D.; Hang, M.; Guosheng, Z.; Chunling, C. Radiative transfer models (RTMs) for field phenotyping inversion of rice based on UAV hyperspectral remote sensing. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Luo, X.; Ran, P.; Zhang, H. Forest canopy water content monitoring using radiative transfer models and machine learning. Forests 2023, 14, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Gao, F.; Anderson, M.; Kustas, W.; Nieto, H.; Knipper, K.; Yang, Y.; White, W.; Alfieri, J.; Torres-Rua, A.; et al. Evaluation of satellite Leaf Area Index in California vineyards for improving water use estimation. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.I.; Awrangjeb, M.; Pan, S.; Mamun, A.A. Transfer learning in agriculture: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takáts, T.; Pásztor, L.; Árvai, M.; Albert, G.; Mészáros, J. Testing the Applicability and Transferability of Data-Driven Geospatial Models for Predicting Soil Erosion in Vineyards. Land 2025, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Santos, J.A. Application of crop modelling to portuguese viticulture: Implementation and added-values for strategic planning. Ciênc. E Téc. Vitiviníc. 2015, 30, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Morais, R.; Peres, E.; Sousa, J.J. Vineyard classification using OBIA on UAV-based RGB and multispectral data: A case study in different wine regions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Rosinskaya, E.; Häni, N.; D’Angelo, E.; Strecha, C. Classification of aerial photogrammetric 3D point clouds. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2018, 84, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovos, R.; Tassopoulos, D.; Kalivas, D.; Lougkos, N.; Priovolou, A. Remote sensing vegetation indices in viticulture: A critical review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N. A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1979, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, O.; Fraga, H.; Sousa, J.J.; Pádua, L. Synergistic use of sentinel-2 and uav multispectral data to improve and optimize viticulture management. Drones 2022, 6, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Chiroque-Solano, P.M.; Marques, P.; Sousa, J.J.; Peres, E. Mapping the leaf area index of castanea sativa miller using uav-based multispectral and geometrical data. Drones 2022, 6, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, B.P.; Spangenberg, G.; Kant, S. Fusion of spectral and structural information from aerial images for improved biomass estimation. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X. A Comprehensive Study of Feature Selection Techniques in Machine Learning Models. Insights Comput. Signals Syst. 2024, 1, 10-70088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.H. Confronting multicollinearity in ecological multiple regression. Ecology 2003, 84, 2809–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerbrei, W.; Royston, P.; Binder, H. Selection of important variables and determination of functional form for continuous predictors in multivariable model building. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 5512–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marill, K.A. Advanced statistics: Linear regression, part II: Multiple linear regression. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2004, 11, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Sanchez-Castillo, M.; Chica-Olmo, M.; Chica-Rivas, M. Machine learning predictive models for mineral prospectivity: An evaluation of neural networks, random forest, regression trees and support vector machines. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 2006, 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Xgboost: Extreme Gradient Boosting; R Package Version 0.4-2; 2015; Volume 1. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/xgboost/index.html (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Natekin, A.; Knoll, A. Gradient boosting machines, a tutorial. Front. Neurorobotics 2013, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Rosset, S.; Zhu, J.; Zou, H. Multi-class adaboost. Stat. Its Interface 2009, 2, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, N.; Fraga, H.; Sousa, J.J.; Pádua, L.; Bento, A.; Couto, P. Comparative Evaluation of Remote Sensing Platforms for Almond Yield Prediction. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Pradhan, B.; Chakraborty, S.; Behera, M.D. Winter wheat yield prediction in the conterminous United States using solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence data and XGBoost and random forest algorithm. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.; Yushchenko, A.; Stratmann, B.; Steinhage, V. Extreme Gradient Boosting for yield estimation compared with Deep Learning approaches. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Pattey, E.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Strachan, I. Effects of chlorophyll concentration on green LAI prediction in crop canopies: Modelling and assessment. In Proceedings of the First International Sysmposium on Recent Advances in Quantitative Remote Sensing, Valencia, Spain, 16–20 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Towers, P.C.; Strever, A.; Poblete-Echeverría, C. Comparison of vegetation indices for leaf area index estimation in vertical shoot positioned vine canopies with and without grenbiule hail-protection netting. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darra, N.; Psomiadis, E.; Kasimati, A.; Anastasiou, A.; Anastasiou, E.; Fountas, S. Remote and proximal sensing-derived spectral indices and biophysical variables for spatial variation determination in vineyards. Agronomy 2021, 11, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Esmeraldas, A.; Pizarro-Oteíza, S.; Labbé, M.; Rojo, F.; Salazar, F. UAV-Based Spectral and Thermal Indices in Precision Viticulture: A Review of NDVI, NDRE, SAVI, GNDVI, and CWSI. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, S.F.; Toscano, P.; Cinat, P.; Berton, A.; Matese, A. A low-cost and unsupervised image recognition methodology for yield estimation in a vineyard. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, R.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Ortega, J.F.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Buesa, I.; Moreno, M.A. Vineyard yield estimation by combining remote sensing, computer vision and artificial neural network techniques. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 1242–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.F. Temporal stability of an NDVI-LAI relationship in a Napa Valley vineyard. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2003, 9, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, A.I.; Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Peña, J.M.; Borra-Serrano, I.; López-Granados, F. 3-D characterization of vineyards using a novel UAV imagery-based OBIA procedure for precision viticulture applications. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Berton, A. Assessment of a canopy height model (CHM) in a vineyard using UAV-based multispectral imaging. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 2150–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.; Rodriguez, D.; O’Leary, G. Measuring and predicting canopy nitrogen nutrition in wheat using a spectral index—The canopy chlorophyll content index (CCCI). Field Crops Res. 2010, 116, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Santesteban, L.G. Methods to compare the spatial variability of UAV-based spectral and geometric information with ground autocorrelated data. A case of study for precision viticulture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F. Practical applications of a multisensor UAV platform based on multispectral, thermal and RGB high resolution images in precision viticulture. Agriculture 2018, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, L.; Biglia, A.; Ricauda Aimonino, D.; Tortia, C.; Mania, E.; Guidoni, S.; Gay, P. Leaf Area Index evaluation in vineyards using 3D point clouds from UAV imagery. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Sen, P.K.; Peddada, S.D. Robust nonlinear regression in applications. J. Indian Soc. Agric. Stat. Indian Soc. Agric. Stat. 2013, 67, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Farokhi, F. Distributionally-robust machine learning using locally differentially-private data. Optim. Lett. 2022, 16, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Marques, P.; Hruška, J.; Adão, T.; Bessa, J.; Sousa, A.; Peres, E.; Morais, R.; Sousa, J.J. Vineyard properties extraction combining UAS-based RGB imagery with elevation data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 5377–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriguinha, A.; Jardim, B.; de Castro Neto, M.; Gil, A. Using NDVI, climate data and machine learning to estimate yield in the Douro wine region. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 114, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.A.; Alsina, M.M.; Nieto, H.; McKee, L.G.; Gao, F.; Kustas, W.P. Determining a robust indirect measurement of leaf area index in California vineyards for validating remote sensing-based retrievals. Irrig. Sci. 2019, 37, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiat, I.; Mackey, H.R.; Al-Ansari, T. A review of evapotranspiration measurement models, techniques and methods for open and closed agricultural field applications. Water 2021, 13, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a two-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.M.; Huang, J.F.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, X.Z. New vegetation index and its application in estimating leaf area index of rice. Rice Sci. 2007, 14, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A modified soil adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Marques, P.; Martins, L.; Sousa, A.; Peres, E.; Sousa, J.J. Monitoring of chestnut trees using machine learning techniques applied to UAV-based multispectral data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote estimation of canopy chlorophyll content in crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L08403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albetis, J.; Jacquin, A.; Goulard, M.; Poilvé, H.; Rousseau, J.; Clenet, H.; Dedieu, G.; Duthoit, S. On the potentiality of UAV multispectral imagery to detect Flavescence dorée and Grapevine Trunk Diseases. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| RF | n_estimators; max_depth; min_samples_split; min_samples_leaf; max_features; bootstrap |

| ET | n_estimators; max_depth; min_samples_split; min_samples_leaf; max_features; bootstrap |

| XGBoost | n_estimators; max_depth; learning_rate; subsample; colsample_bytree; gamma; alpha; lambda |

| GB | n_estimators; learning_rate; max_depth; min_samples_split; min_samples_leaf; subsample; max_features |

| AdaBoost | n_estimators; learning_rate; max_depth; min_samples_split; min_samples_leaf |

| Category | Parameter | Pruning Wood | Yield | LAI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veraison | Berries Softening | Harvest Ready | Veraison | Berries Softening | Harvest Ready | All | ||

| Geometrical features | Height | 0.30 * | 0.49 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.35 ** | 0.30 *** |

| Max height | 0.22 | 0.38 ** | 0.43 *** | 0.34 ** | 0.30 * | 0.15 | 0.33 *** | |

| Volume | 0.71 *** | 0.75 *** | 0.82 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.25 * | 0.53 *** | |

| Area | 0.81 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.77 *** | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.54 *** | |

| Bands and Normalized Bands | Green | 0.25 * | 0.23 * | 0.33 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.39 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.17 * |

| Red | −0.51 *** | −0.48 *** | −0.03 | −0.36 ** | −0.07 | 0.32 ** | −0.16 * | |

| Red Edge | 0.66 *** | 0.73 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.31 ** | 0.43 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.29 *** | |

| NIR | 0.67 *** | 0.82 *** | 0.78 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.59 *** | |

| Gn | −0.71 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.21 | −0.28 * | 0.02 | 0.25 * | −0.33 *** | |

| Vegetation indices | CIRE | 0.30 * | 0.06 | 0.49 *** | 0.40 *** | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.08 |

| GNDVI | 0.59 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.27 * | 0.42 ** | 0.08 | −0.23 * | 0.41 *** | |

| GRNDVI | 0.76 *** | 0.78 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.23 * | −0.15 | 0.45 *** | |

| GRVI | 0.54 *** | 0.70 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.29 * | 0.42 *** | 0.25 * | 0.32 *** | |

| MSAVI | 0.69 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.79 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.30 ** | 0.78 *** | |

| NDExNIR | 0.72 *** | 0.56 *** | −0.03 | 0.44 *** | 0.14 | −0.36 ** | −0.15 * | |

| NDExRE | 0.67 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.64 *** | 0.31 ** | 0.28 * | 0.45 *** | 0.56 *** | |

| NDRE | −0.18 | 0.09 | 0.48 *** | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.19 ** | |

| NDVI | 0.58 *** | 0.84 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.34 ** | 0.02 | 0.39 *** | |

| REGI | 0.75 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.20 | 0.26 * | 0.11 | −0.27 * | 0.20 ** | |

| SAVI | 0.60 *** | 0.86 *** | 0.79 *** | 0.39 ** | 0.46 *** | 0.31 ** | 0.63 *** | |

| Predictive Variable | Phen. Stage | Data Type | Model | Model Configuration | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAI | All | Geom. + Spec. | RF | n_estimators: 200; max_depth: None; min_samples_split: 5; min_samples_leaf: 2; max_features: sqrt; bootstrap: True | 0.83 | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| Spec. | ET | n_estimators: 150; max_depth: None; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 2; max_features: sqrt; bootstrap: False | 0.74 | 0.29 | 0.23 | ||

| Pruning wood biomass | Vér. | Geom. + Spec. | ET | n_estimators: 200; max_depth: 10; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 2; max_features: sqrt; bootstrap: False | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.44 |

| Spec. | RF | n_estimators: 50; max_depth: None; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 4; max_features: sqrt; bootstrap: True | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.38 | ||

| B. soft. | Geom. + Spec. | AB | n_estimators: 100; max_depth: 3; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 4; learning_rate: 0.005 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.22 | |

| Spec. | AB | n_estimators: 100; max_depth: 3; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 4; learning_rate: 0.005 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.22 | ||

| Harv. | Geom. + Spec. | MLR | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.29 | ||

| Spec. | MLR | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.29 | |||

| Yield | Vér. | Geom. + Spec. | RF | n_estimators: 200; max_depth: 3; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 4; max_features: log2; bootstrap: False | 0.67 | 2.93 | 2.32 |

| Spec. | MLR | 0.64 | 3.16 | 2.61 | |||

| B. soft. | Geom. + Spec. | RF | n_estimators: 100; max_depth: 3; min_samples_split: 12; min_samples_leaf: 4; max_features: log2; bootstrap: False | 0.71 | 3.01 | 2.21 | |

| Spec. | AB | n_estimators: 50; max_depth: 7; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 4; learning_rate: 1 | 0.56 | 3.44 | 2.58 | ||

| Harv. | Geom. + Spec. | RF | n_estimators: 100; max_depth: 5; min_samples_split: 10; min_samples_leaf: 3; max_features: log2; bootstrap: False | 0.75 | 2.31 | 1.97 | |

| Spec. | MLR | 0.74 | 4.48 | 3.82 |

| Grapevine Variety | Mean LAI | Pruning Wood Biomass (kg) | Yield (kg) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vér. | B. Soft. | Harv. | Vér. | B. Soft. | Harv. | Vér. | B. Soft. | Harv. | |

| Tinto Cão | 1.75 () | 1.79 () | 1.43 () | 74.4 () | 48.2 () | 50.7 () | 299.6 () | 280.8 () | 249.0 () |

| Touriga Franca | 1.23 () | 1.58 () | 1.27 () | 48.8 () | 40.6 () | 44.3 () | 274.5 () | 203.7 () | 228.1 () |

| Tinta Barroca | 1.21 () | 1.60 () | 1.35 () | 58.3 () | 37.9 () | 44.4 () | 235.6 () | 148.3 () | 197.7 () |

| Total Analyzed Blocks | 1.39 () | 1.66 () | 1.35 () | 181.5 () | 126.8 () | 139.4 () | 809.7 () | 632.8 () | 674.7 () |

| Total Vineyard | 1.28 | 1.55 | 1.22 | 1208.4 | 896.5 | 1051.5 | 6013.6 | 4437.8 | 4868.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, P.; Ferreira, L.; Adão, T.; Sousa, J.J.; Morais, R.; Peres, E.; Pádua, L. Integrating UAV Multi-Temporal Imagery and Machine Learning to Assess Biophysical Parameters of Douro Grapevines. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233915

Marques P, Ferreira L, Adão T, Sousa JJ, Morais R, Peres E, Pádua L. Integrating UAV Multi-Temporal Imagery and Machine Learning to Assess Biophysical Parameters of Douro Grapevines. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233915

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Pedro, Leilson Ferreira, Telmo Adão, Joaquim J. Sousa, Raul Morais, Emanuel Peres, and Luís Pádua. 2025. "Integrating UAV Multi-Temporal Imagery and Machine Learning to Assess Biophysical Parameters of Douro Grapevines" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233915

APA StyleMarques, P., Ferreira, L., Adão, T., Sousa, J. J., Morais, R., Peres, E., & Pádua, L. (2025). Integrating UAV Multi-Temporal Imagery and Machine Learning to Assess Biophysical Parameters of Douro Grapevines. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3915. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233915