Four Decades of Thermal Monitoring in a Tropical Urban Reservoir Using Remote Sensing: Trends, Climatic and External Drivers of Surface Water Warming in Lake Paranoá, Brazil

Highlights

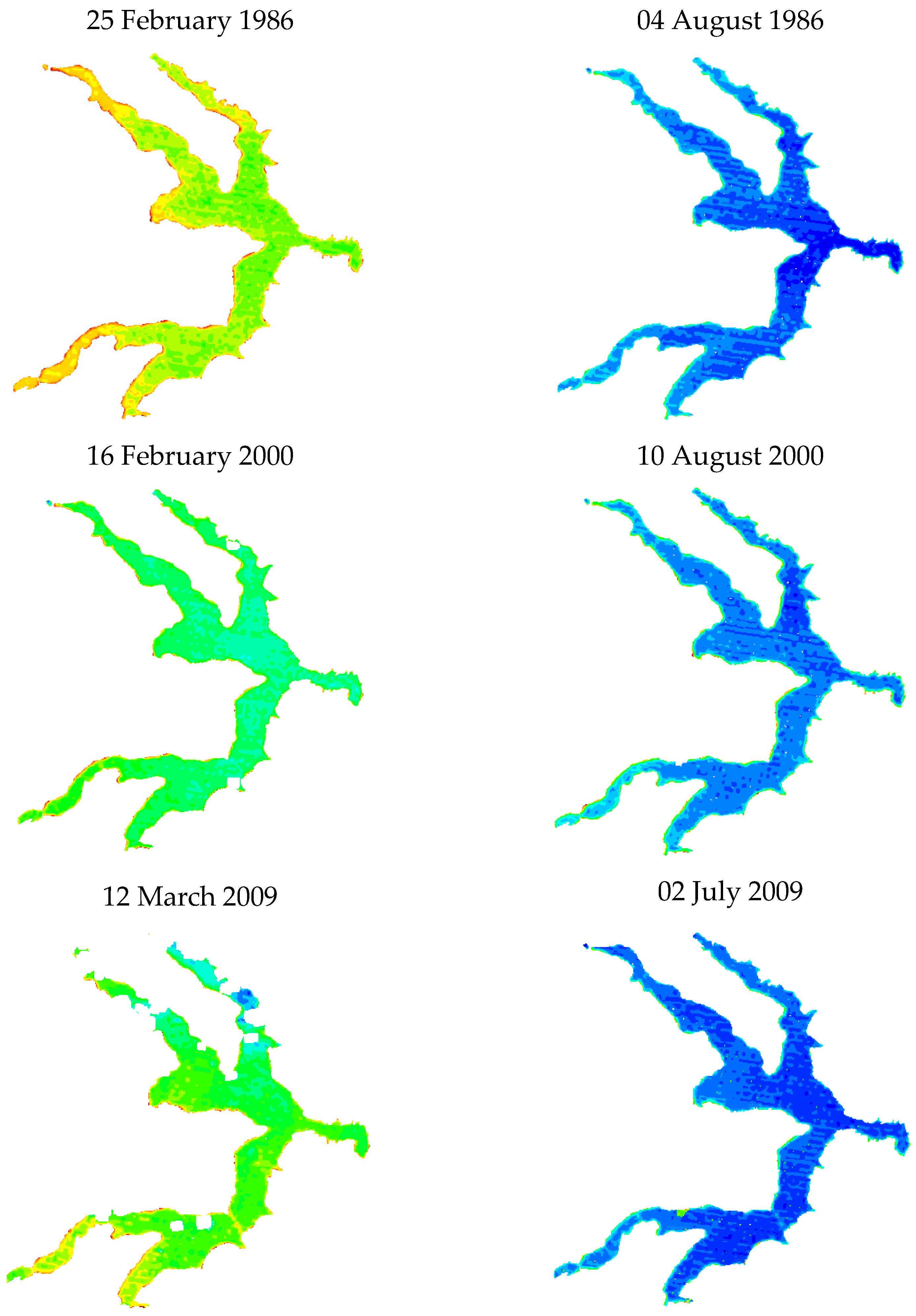

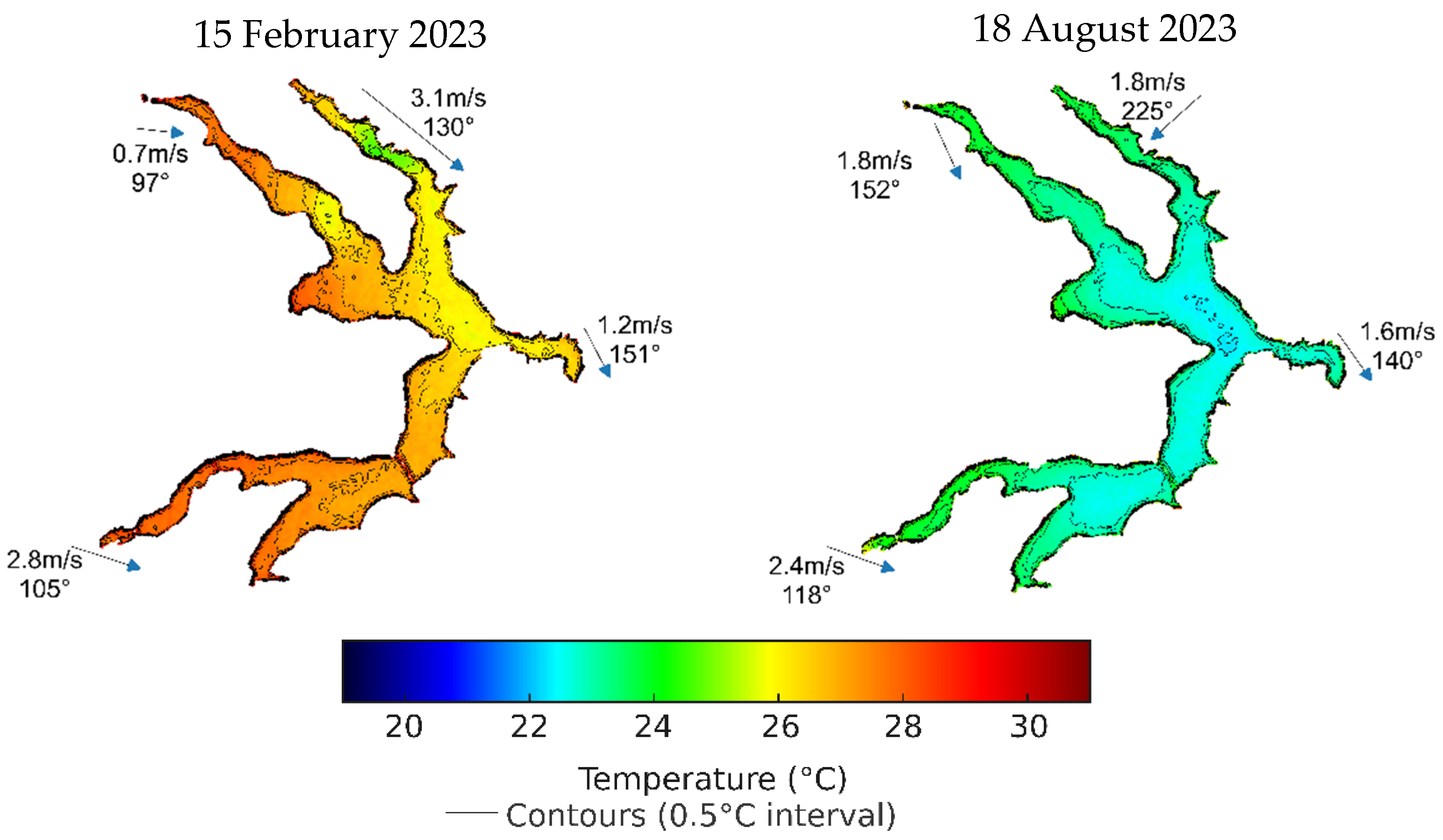

- Remote sensing revealed spatial and seasonal heterogeneity in lake surface warming.

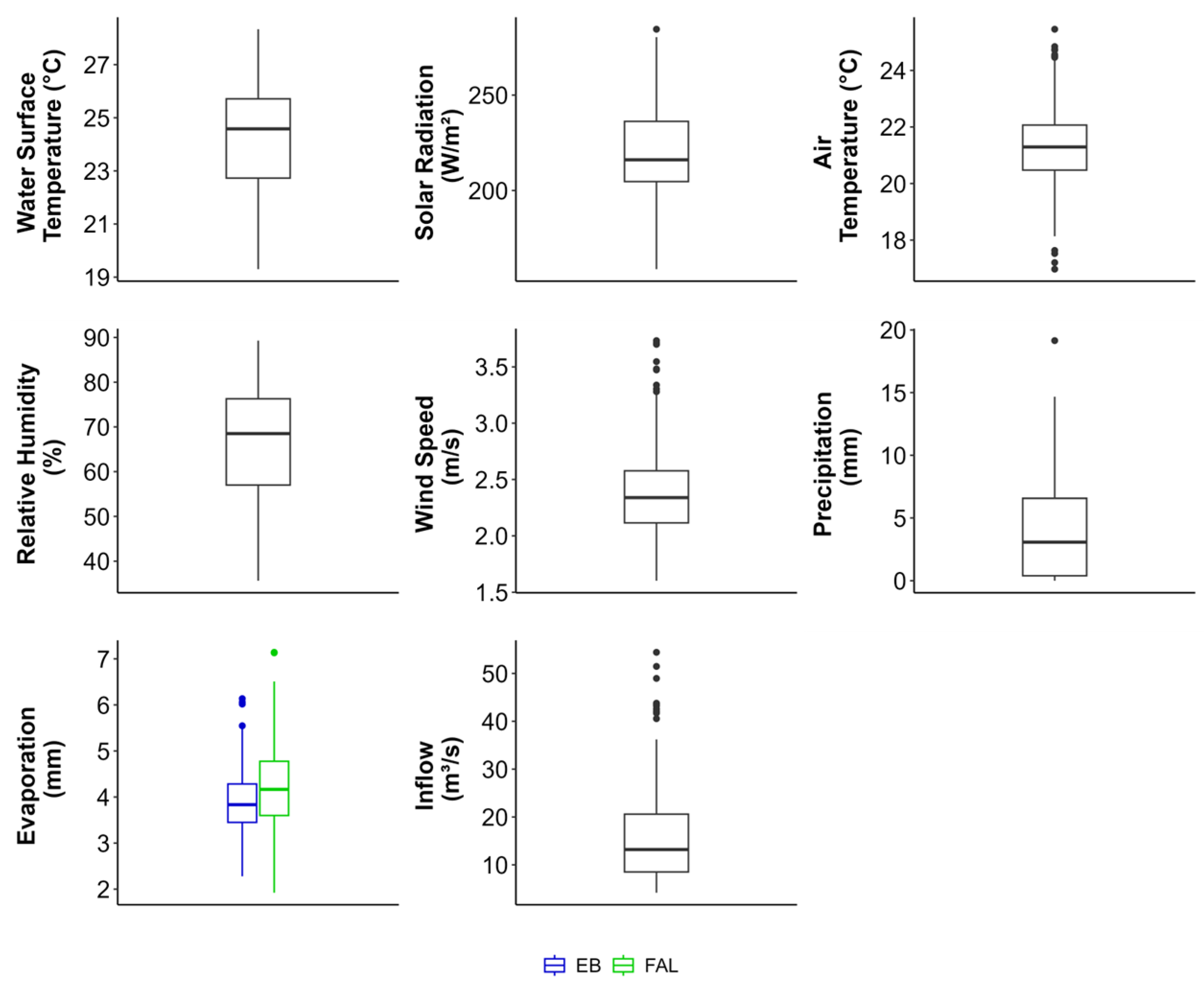

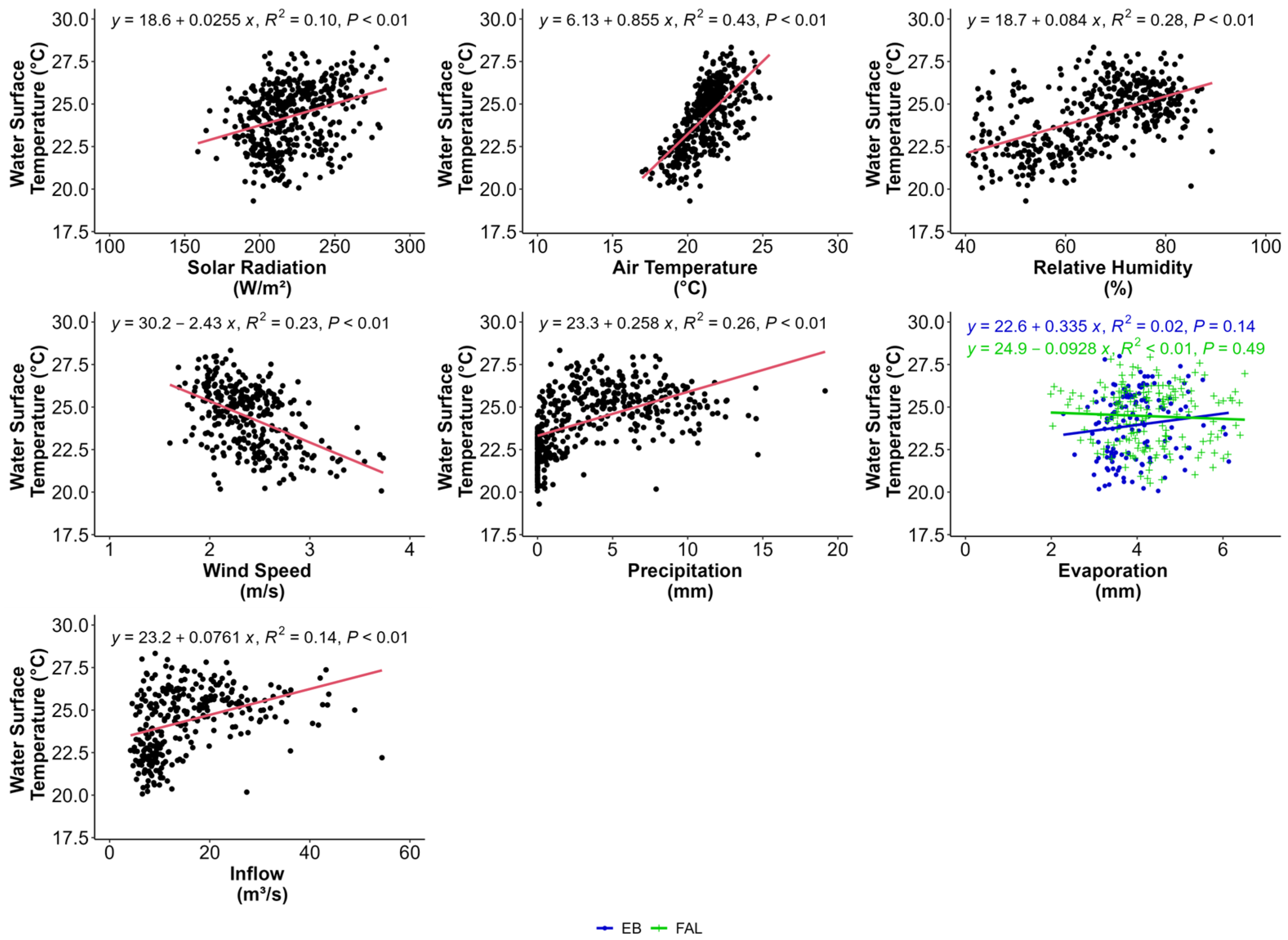

- Air temperature, solar radiation, humidity, and wind speed are the main external drivers.

- In situ and satellite-derived water surface temperatures reveal climate-driven lake warming.

- Findings support hydrodynamic modeling and water quality management in urban tropical reservoirs.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area: Paranoá Lake, a Tropical Urban Reservoir

2.2. Ground-Based Monitoring of WST, Meteorological and Hydrological Variables

2.3. Water Surface Temperature Retrieval from Landsat Imagery

2.4. Model Validation and Statistical Analysis of External Drivers

3. Results

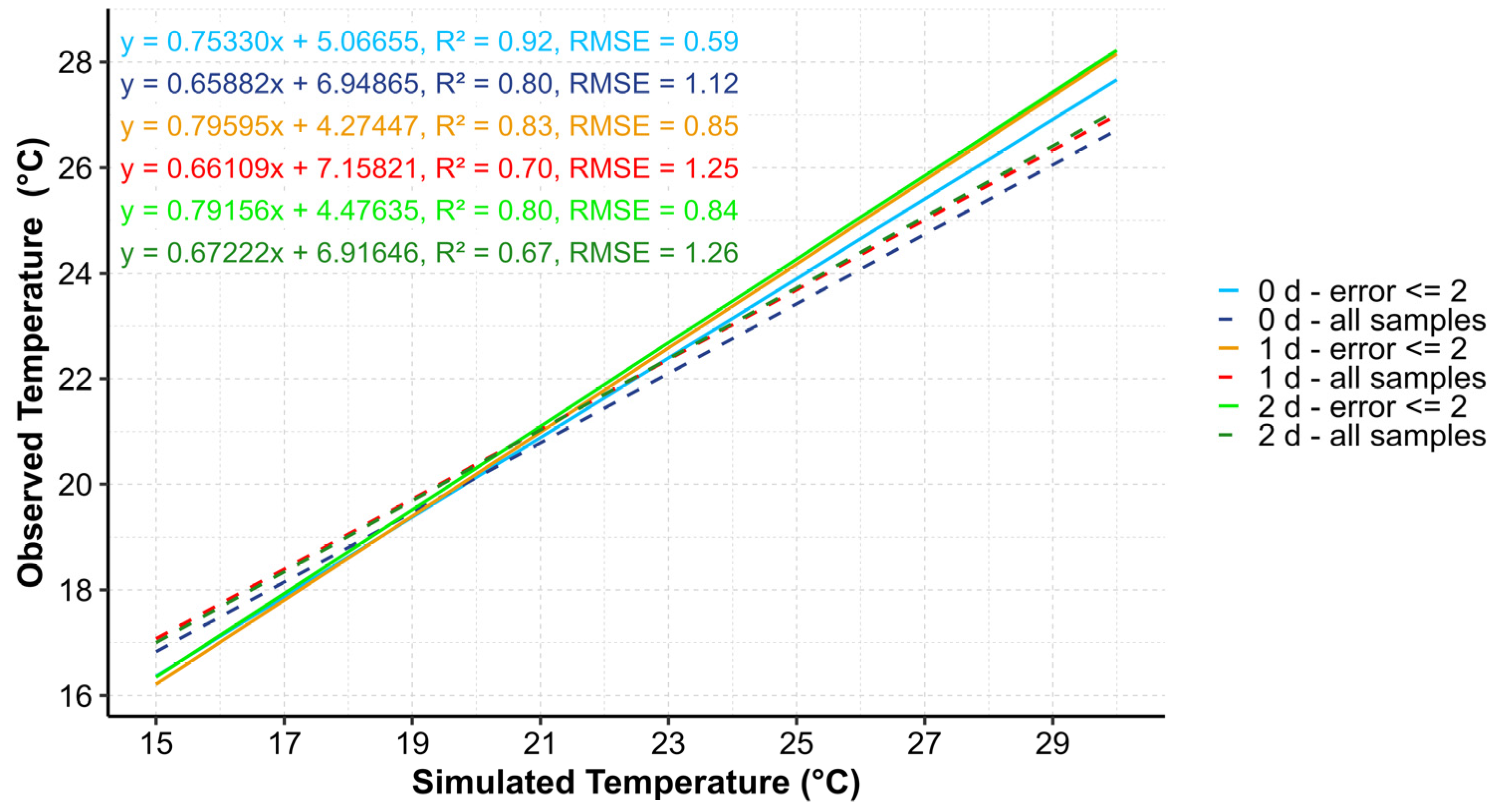

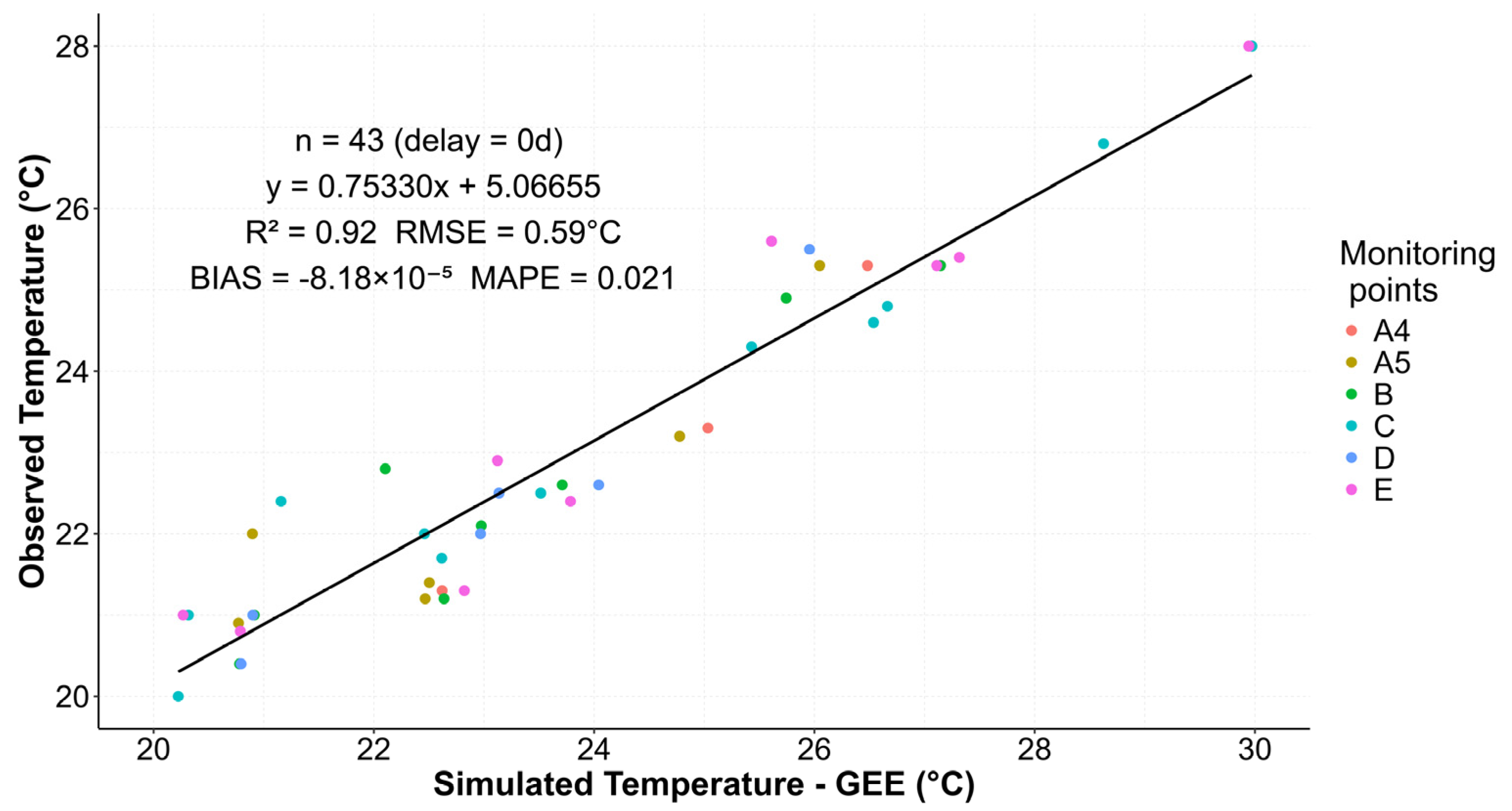

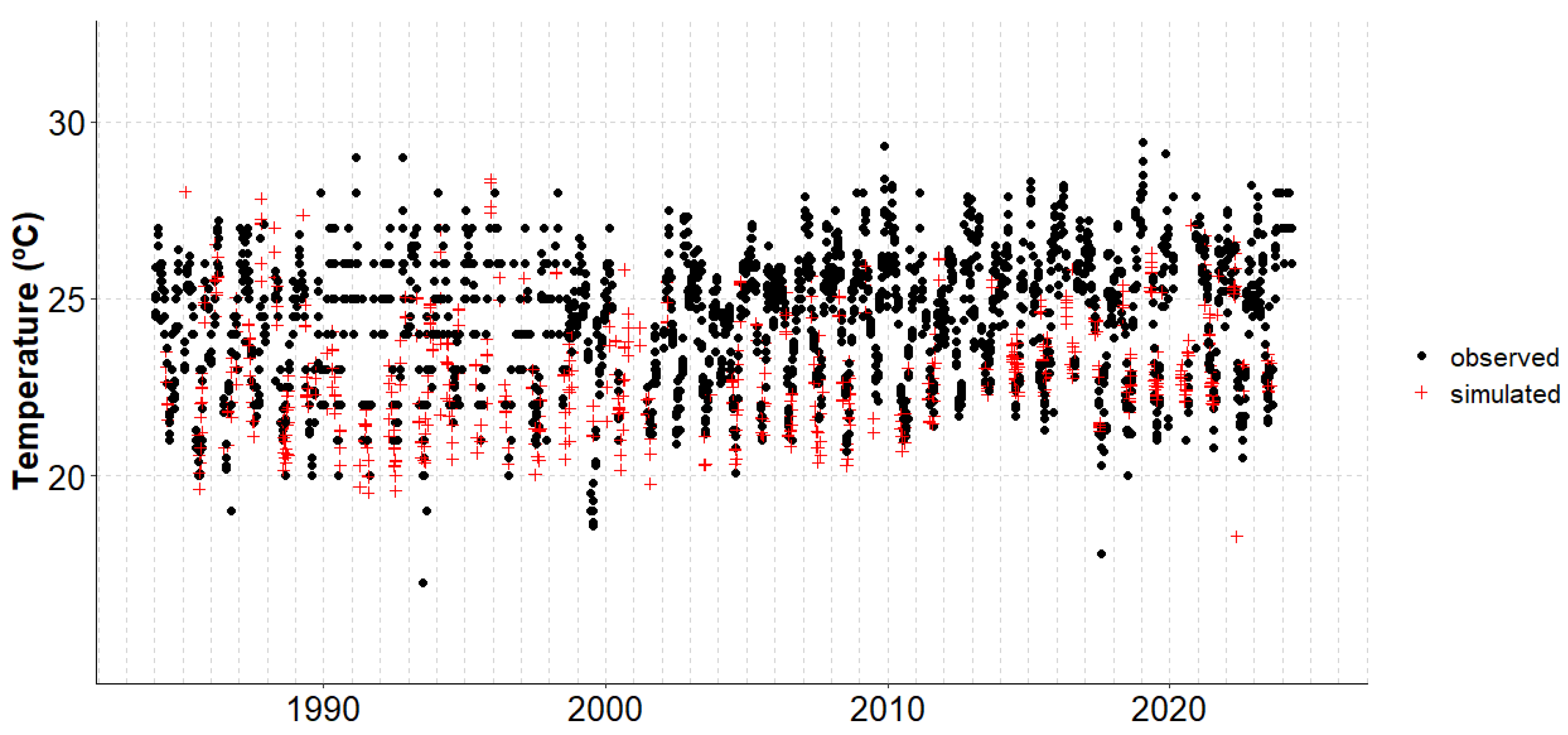

3.1. Estimation and Validation of Water Surface Temperature (WST)

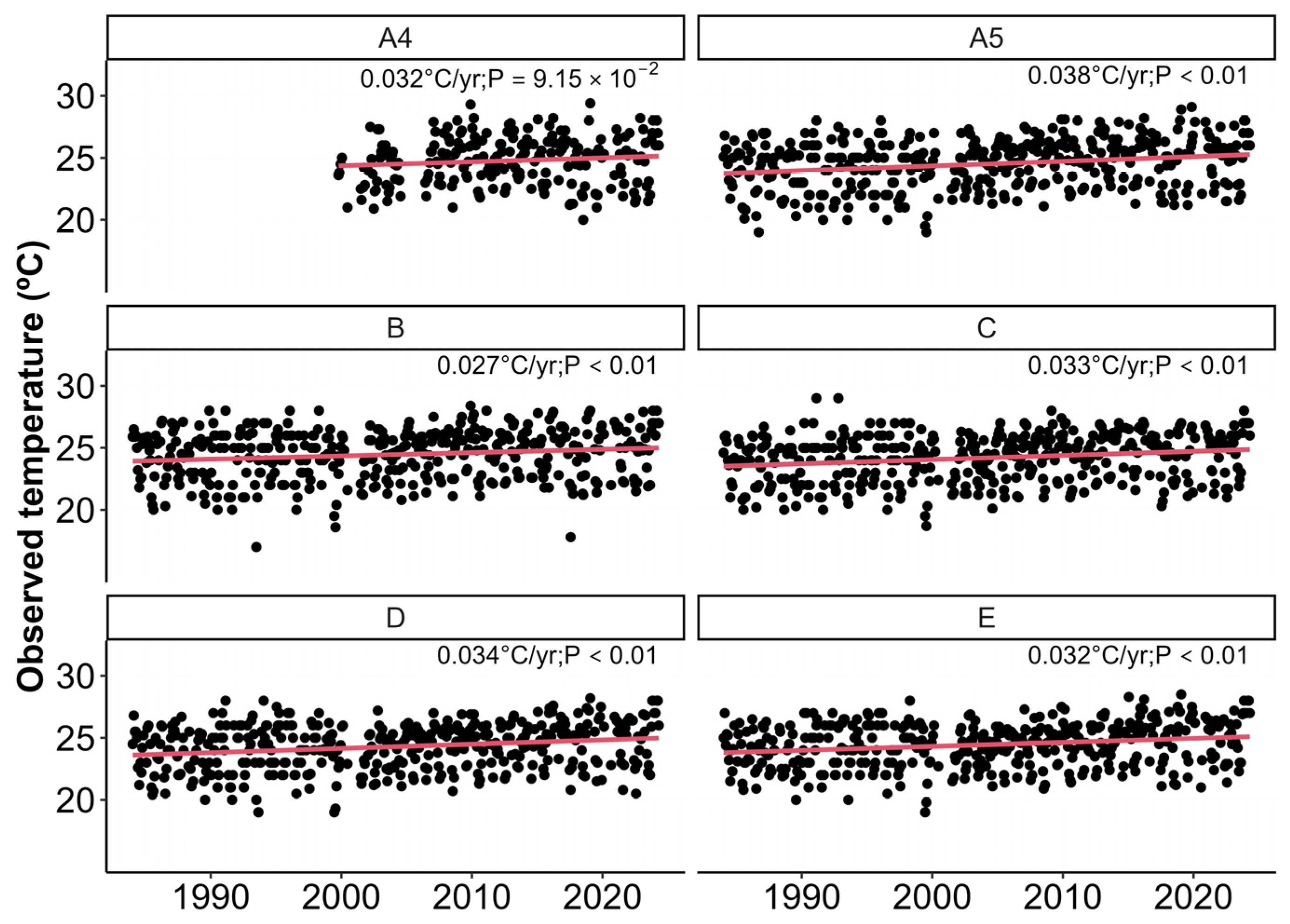

3.2. Temporal Trends in Water Surface Temperature and External Forcings

3.3. Multiscale Correlation Analysis Between WST and External Forcings

3.4. Key Drivers of Water Surface Temperature Across Temporal Scales

4. Discussion

4.1. Water Surface Temperature and External Forcings

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Management Implications and Future Perspectives

- Improve automation and reproducibility of WST retrievals by defining and implementing a lake-specific atmospheric-correction strategy for cirrus clouds and sunglint.

- Acquiring water temperature and meteorological data closer to the lake and, where necessary, at higher temporal frequency, enabling analysis of external forcings on both the central basin and the individual branches.

- Quantify the surface heat budget and large-scale climate drivers: compute and validate the main air–water heat-flux components, net shortwave and longwave radiation, sensible and latent heat fluxes, to better represent air–water energy exchange. In parallel, incorporate larger-scale climate factors (e.g., ENSO/ONI, PDO, AMO) to contextualize interannual–decadal variability and extremes.

- Examining heat-budget variables—sensible heat flux, latent heat flux, and longwave radiation— to improve the predictive skill of WST models.

- Integrating satellite-derived temperature fields into 3D hydrodynamic and ecological models to simulate stratification dynamics, nutrient cycling, and algal/cyanobacterial blooms under different climate and land-use/land-cover scenarios, as well as to test potential management interventions (e.g., artificial mixing or withdrawal).

- Assimilate satellite-derived WST into 3D hydrodynamic model to quantify the contributions of external forcings—including heat fluxes—to WST variability and long-term trends.

5. Conclusions

- improving automation and reproducibility of WST retrieval processes;

- defining a strategy and implementing atmospheric correction for cirrus clouds and sunglint over the lake to automate the estimation process;

- analyzing wind influence on lake thermal dynamics by incorporating additional descriptors such as fetch length, wind direction, persistence, and spatial heterogeneity of wind fields;

- expanding data acquisition and monitoring to evaluate these relationships between variables within each lake branch.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

| WTP | Water Treatment Plant |

| WST | Water Surface Temperature |

| FAL | Fazenda Água Limpa (location of an evaporation monitoring site) |

| EB | Estação da Biologia (location of an evaporation monitoring site) |

| INMET | National Institute of Meteorology (Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia) |

| CAESB | Environmental Sanitation Company of Federal District (Companhia de Saneamento Ambiental do Distrito Federal) |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| ANA | Water National Agency (Agência Nacional de Águas) |

| UnB | University of Brasília |

| SW | Shortwave Radiation |

| LW | Longwave Radiation |

| LH | Latent Heat |

| H | Sensible Heat |

| ENSO | El Niño-Southern Oscillation |

| ONI | Oceanic Niño Index |

| PDO | Pacific Decadal Oscillation |

| AMO | Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation |

| SAMS | South American Monsoon System |

| SACZ | South Atlantic Convergence Zone |

References

- Wang, X.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Woolway, R.I.; Piao, S.; Jeppesen, E. Climate Change Drives Rapid Warming and Increasing Heatwaves of Lakes. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, J.A.; García-Monteiro, S.; Julien, Y. An Analysis of the Lake Surface Water Temperature Evolution of the World’s Largest Lakes during the Years 2003–2020 Using MODIS Data. Recent Adv. Remote Sens. 2024, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Woolway, R.I.; Timmermann, A.; Lee, S.-S.; Rodgers, K.B.; Yamaguchi, R. Emergence of Lake Conditions That Exceed Natural Temperature Variability. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorjsuren, B.; Zemtsov, V.A.; Batsaikhan, N.; Demberel, O.; Yan, D.; Hongfei, Z.; Yadamjav, O.; Chonokhuu, S.; Enkhbold, A.; Ganzorig, B.; et al. Trend Analysis of Hydro-Climatic Variables in the Great Lakes Depression Region of Mongolia. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 940–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.I.; Merchant, C.J. Worldwide Alteration of Lake Mixing Regimes in Response to Climate Change. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Bai, G.; Zhou, J.; McKay, D. Lake Surface Water Temperature in China from 2001 to 2021 Based on GEE and HANTS. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 84, 102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S.; Gray, D.K.; Hampton, S.E.; Read, J.S.; Rowley, R.J.; Schneider, P.; Lenters, J.D.; McIntyre, P.B.; Kraemer, B.M.; et al. Rapid and Highly Variable Warming of Lake Surface Waters around the Globe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 10773–10781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Guo, C.; Su, F.; Xu, W.; Ma, L.; Cui, L.; Mi, C. Climate Warming Effects on Temperature Structure in Lentic Waters: A Bibliometric Analysis from the Recent 20 Years. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Leavitt, P.R.; Rose, K.C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Qin, B. Controls of Thermal Response of Temperate Lakes to Atmospheric Warming. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, X.; Pi, X.; Xu, W.; Woolway, R.I. Global Lakes Are Warming Slower than Surface Air Temperature Due to Accelerated Evaporation. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Yang, K.; Peng, Z.; Tang, L.; Duan, H.; Luo, Y. Review on the Change Trend, Attribution Analysis, Retrieval, Simulation, and Prediction of Lake Surface Water Temperature. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 6324–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, D.; Kiefer, I.; Wüest, A.; Wunderle, S.; Odermatt, D. Are Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll in a Large Deep Lake Related? An Analysis Based on Satellite Observations in Synergy with Hydrodynamic Modelling and in-Situ Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 209, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, B.; Du, Y.; Wang, L. Characteristics of Water Quality Response to Hypolimnetic Anoxia in Daheiting Reservoir. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winton, R.S.; Calamita, E.; Wehrli, B. Reviews and Syntheses: Dams, Water Quality and Tropical Reservoir Stratification. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 1657–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elçi, Ş. Effects of Thermal Stratification and Mixing on Reservoir Water Quality. Limnology 2008, 9, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greb, S.; Dekker, A.; Binding, C. (Eds.) Earth Observations in Support of Global Water Quality Monitoring; IOCCG Report Series, No. 17; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2018; ISBN 978-1-896246-67-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, D.R.; Ogashawara, I.; Gitelson, A.A. (Eds.) Bio-Optical Modelling and Remote Sensing of Inland Waters; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 978-0-12-804644-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gholizadeh, M.; Melesse, A.; Reddi, L. A Comprehensive Review on Water Quality Parameters Estimation Using Remote Sensing Techniques. Sensors 2016, 16, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedreros-Guarda, M.; Abarca-del-Río, R.; Escalona, K.; García, I.; Parra, Ó. A Google Earth Engine Application to Retrieve Long-Term Surface Temperature for Small Lakes. Case: San Pedro Lagoons, Chile. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Saravanakumar, R.; Arulanandam, M.; Ilakkiya, S. Google Earth Engine: Empowering Developing Countries with Large-Scale Geospatial Data Analysis—A Comprehensive Review. Arab. J. Geosci. 2024, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, P. Progress and Trends in the Application of Google Earth and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.I.; Kraemer, B.M.; Lenters, J.D.; Merchant, C.J.; O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S. Global Lake Responses to Climate Change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhellemont, Q. Automated Water Surface Temperature Retrieval from Landsat 8/TIRS. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgué-Itier, O.; Melo Vieira Soares, L.; Anneville, O.; Bouffard, D.; Chanudet, V.; Danis, P.A.; Domaizon, I.; Guillard, J.; Mazure, T.; Sharaf, N.; et al. Past and Future Climate Change Effects on the Thermal Regime and Oxygen Solubility of Four Peri-Alpine Lakes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 837–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, R.; O’Reilly, C.M.; Zagarese, H.; Baines, S.B.; Hessen, D.O.; Keller, W.; Livingstone, D.M.; Sommaruga, R.; Straile, D.; Van Donk, E.; et al. Lakes as Sentinels of Climate Change. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009, 54, 2283–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Liu, Y.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Søndergaard, M.; Han, B.; Wang, J.; Jeppesen, E.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Q.L. Warming Exacerbates the Impact of Nutrient Enrichment on Microbial Functional Potentials Important to the Nutrient Cycling in Shallow Lake Mesocosms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X. Spatial and Temporal Variations in the Relationship between Lake Water Surface Temperatures and Water Quality—A Case Study of Dianchi Lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brostel, R.; Mühlhofer, S.I.; Serique, E.F.S.; Starling, F.L.R.M.; Oliveira, L.S.; Borges, M.N.; de Lima, T.G. Caesb Inova—Crise Hídrica: Superação em Tempo Recorde; Companhia de Saneamento Ambiental do Distrito Federal (Caesb): Brasilia, Brazil, 2018; p. 48.

- Angelini, R.; Bini, L.M.; Starling, F.L.R.M. Efeitos de Diferentes Intervenções no Processo de Eutrofização do Lago Paranoá (BRASÍLIA-DF). Oecol. Austr. 2008, 12, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mar Da Costa, N.Y.; Boaventura, G.R.; Mulholland, D.S.; Araújo, D.F.; Moreira, R.C.A.; Faial, K.C.F.; Bomfim, E.D.O. Biogeochemical Mechanisms Controlling Trophic State and Micropollutant Concentrations in a Tropical Artificial Lake. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovesi-Fonseca, C.; Philomeno, M.G. Effects of Algicide (Copper Sulfate) Application on Short-Term Fluctuations of Phytoplankton in Lake Paranoá, Central Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 2004, 64, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, G.; Minoti, R.T.; Koide, S. Mathematical Modeling of Watersheds as a Subsidy for Reservoir Water Balance Determination: The Case of Paranoá Lake, Federal District, Brazil. Hydrology 2020, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, B.D.; Fonseca, B.M. Fitoplâncton Da Região Central Do Lago Paranoá (DF): Uma Abordagem Ecológica e Sanitária. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2018, 23, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.B.; Bellotto, V.R.; Barbosa, J.D.S.B.; Lima, T.B. Spatiotemporal Variation on Water Quality and Trophic State of a Tropical Urban Reservoir: A Case Study of the Lake Paranoá-DF, Brazil. Water 2021, 13, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Coelho, R.M. Flutuações sazonais e de curta duração na comunidade zooplanctônica do lago Paranoá, Brasília-DF, Brasil. Rev. Brasil. Biol. 1987, 47, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, C.A. Estrutura da Comunidade Zooplanctônica e Qualidade da água no Lago Paranoá, Brasília-DF. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília-DF, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, T.D.S.; Gomes, L.N.L. Avaliação do Comportamento de Parâmetros Limnológicos de Qualidade da água na Região mais Profunda do Lago Paranoá/DF. XIV Encontro Nacional de Estudantes de Engenharia Ambiental, Brasília, Brazil. Blucher Eng. Proc. 2016, 3, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.C.; Gomes, L.N.L.; Minoti, R.T. A Modelling Approach to Simulate Chlorophyta and Cyanobacteria Biomasses Based on Historical Data of a Brazilian Urban Reservoir. Rev. Ambiente Água 2021, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornelas, K.D.E.S.; Silva, C.L.D.; Oliveira, C.A.D.S. Coeficientes Médios da Equação de Angström-Prescott, Radiação Solar e Evapotranspiração de Referência em Brasília. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2006, 41, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pereira, A.R.; Argenta, T.S.; Cicerelli, R.E.; Koide, S. A Variabilidade do Evento em Agosto e Dezembro de 2021 às Margens do Lago Paranoá, Brasília-DF, Brasil. In Proceedings of the Anais do 32° Congresso da ABES, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 21–24 May 2023. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Verbesselt, J.; Hyndman, R.; Newnham, G.; Culvenor, D. Detecting Trend and Seasonal Changes in Satellite Image Time Series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Hunziker, S.; Wüest, A. Lake Surface Temperatures in a Changing Climate: A Global Sensitivity Analysis. Clim. Change 2014, 124, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.C.N.; Ianniruberto, M.; Borges, W.R.; Roig, H.L.; Turquetti, G.N.; de França, P.H.P. Mapeamento Topo-Batimétrico de Reservatório Utilizando LIDAR e Batimetria no Lago Paranoá-DF; Sociedade Brasileira de Geofísica (SBGf): Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.C.; Hinkley, D.V. Bootstrap Methods and Their Application, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0-521-57391-7. [Google Scholar]

- Canty, A.; Ripley, B.D. Boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions 2024. Available online: https://10.32614/CRAN.package.boot (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Verbesselt, J.; Hyndman, R.; Zeileis, A.; Culvenor, D. Phenological Change Detection While Accounting for Abrupt and Gradual Trends in Satellite Image Time Series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2970–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, R. Thermal Structure of Water During the Summer in Lakes of the Polish Lowlands as a Result of Their Varied Morphometry. Limnol. Rev. 2020, 20, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehrer, B.; Schultze, M. Stratification of Lakes. Rev. Geophys. 2008, 46, 2006RG000210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herb, W.R.; Stefan, H.G. Temperature Stratification and Mixing Dynamics in a Shallow Lake with Submersed Macrophytes. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2004, 20, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Deng, J.; Shi, K.; Wang, J.; Brookes, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Paerl, H.W.; Wu, L. Extreme Climate Anomalies Enhancing Cyanobacterial Blooms in Eutrophic Lake Taihu, China. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.Y.; Han, H.J.; Cho, Y.-C.; Kang, T.; Im, J.K. Seasonal Variations in the Thermal Stratification Responses and Water Quality of the Paldang Lake. Water 2024, 16, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, F.; Mackay, E.B.; Spears, B.M.; Barker, P.; Jones, I.D. Interacting Impacts of Hydrological Changes and Air Temperature Warming on Lake Temperatures Highlight the Potential for Adaptive Management. Ambio 2025, 54, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhateria, R.; Jain, D. Water Quality Assessment of Lake Water: A Review. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 2, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaro, A.A.; Mariñelarena, A.; Torrusio, S.E.; Sala, S.E. Water Surface Temperature Estimation from Landsat 7 ETM+ Thermal Infrared Data Using the Generalized Single-Channel Method: Case Study of Embalse Del Río Tercero (Córdoba, Argentina). Adv. Space Res. 2013, 51, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-L.; Tang, B.-H.; Wu, H.; Ren, H.; Yan, G.; Wan, Z.; Trigo, I.F.; Sobrino, J.A. Satellite-Derived Land Surface Temperature: Current Status and Perspectives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 131, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Han, J.-C.; Wang, P. Near Real-Time Retrieval of Lake Surface Water Temperature Using Himawari-8 Satellite Imagery and Machine Learning Techniques: A Case Study in the Yangtze River Basin. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1335725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Hook, S.J.; Radocinski, R.G.; Corlett, G.K.; Hulley, G.C.; Schladow, S.G.; Steissberg, T.E. Satellite Observations Indicate Rapid Warming Trend for Lakes in California and Nevada. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, 2009GL040846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, R.; Perez-Losada, J.; Schladow, G.; Richards, R.; Goldman, C. The Warming of Lake Tahoe. Clim. Change 2006, 76, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić, Ž. Increasing Water Temperature of the Largest Freshwater Lake on the Mediterranean Islands as an Indicator of Global Warming. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, R.; Acharya, K.; Ibrahim, M. Thermal Stratification and Mixing Processes Response to Meteorological Factors in a Monomictic Reservoir. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutsaert, W. Evaporation into the Atmosphere; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1982; ISBN 978-90-481-8365-4. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, W.J. Terrestrial Hydrometeorology; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-470-65937-3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, R. Lake Surface Temperature Predictions under Different Climate Scenarios with Machine Learning Methods: A Case Study of Qinghai Lake and Hulun Lake, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Li, C.; Wang, T. Estimating the Sensitivity of the Priestley–Taylor Coefficient to Air Temperature and Humidity. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 4349–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichet, A.; Wild, M.; Folini, D.; Schär, C. Causes for Decadal Variations of Wind Speed over Land: Sensitivity Studies with a Global Climate Model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 2012GL051685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, K.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Dickinson, R. Increase in Surface Friction Dominates the Observed Surface Wind Speed Decline during 1973–2014 in the Northern Hemisphere Lands. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 7421–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Liu, W.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Minola, L.; Chen, D. Terrestrial Stilling Projected to Continue in the Northern Hemisphere Mid-Latitudes. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jeong, S.; Park, H.; Kim, J.; Park, C.-R. Urbanization Has Stronger Impacts than Regional Climate Change on Wind Stilling: A Lesson from South Korea. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 054016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Yan, Z.; Zha, J. Urbanization Impact on Regional Wind Stilling: A Modeling Study in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region of China. JGR Atmos. 2020, 125, e2020JD033132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.; Ni, G.; Yang, H.; Lei, Z. Numerical Analysis on the Contribution of Urbanization to Wind Stilling: An Example over the Greater Beijing Metropolitan Area. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2013, 52, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.I.; Meinson, P.; Nõges, P.; Jones, I.D.; Laas, A. Atmospheric Stilling Leads to Prolonged Thermal Stratification in a Large Shallow Polymictic Lake. Clim. Change 2017, 141, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potisomporn, P.; Vogel, C.R. Spatial and Temporal Variability Characteristics of Offshore Wind Energy in the United Kingdom. Wind Energy 2022, 25, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, G.M.D.; Sobrinho, J.E.; Santos, W.D.O.; Costa, D.D.O.; Silva, S.T.A.D.; Maniçoba, R.M. Caracterização Da Velocidade e Direção Do Vento Em Mossoró/RN (Characterization of Wind Speed and Direction in Mossoró/RN). Rev. Bras. Geog. Fis. 2014, 7, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiotto, S.R.; Ferreira, F.M.; Maximiano, C.V. Um Estudo da Velocidade e Direção Predominante do Vento em Brasília, DF. In Proceedings of the XVIII Congresso Brasileiro de Agrometeorologia—XVIII CBA 2013 and VII Reunião Latino Americana de Agrometeorologia, Belém, PA, Brazil, 16–19 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak, O.M.; Fitzpatrick, F.A.; Dow, B.A.; Blount, J.D.; Sullivan, D.J.; Reneau, P.C. Influences of Meteorological Conditions, Runoff, and Bathymetry on Summer Thermal Regime of a Great Lakes Estuary. J. Great Lakes Res. 2024, 50, 102416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiao, W.; Cao, C.; Gao, Z.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Shen, S.; Wang, L.; Xiao, Q.; Xu, J.; et al. Temporal and Spatial Variations in Radiation and Energy Balance across a Large Freshwater Lake in China. J. Hydrol. 2014, 511, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, M.R.; Wu, C.H. Response of Water Temperatures and Stratification to Changing Climate in Three Lakes with Different Morphometry. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 6253–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, E.; Amadori, M.; Free, G.; Giardino, C.; Bresciani, M. A Satellite-Based Tool for Mapping Evaporation in Inland Water Bodies: Formulation, Application, and Operational Aspects. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, L.; Villarini, G. On the Impact of Gaps on Trend Detection in Extreme Streamflow Time Series. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 3976–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Razlustkij, V.; Rudstam, L.G.; Jeppesen, E.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Effects of Elevated Temperature on Resources Competition of Nutrient and Light Between Benthic and Planktonic Algae. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 908088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C.E.; Overholt, E.P.; Pilla, R.M.; Leach, T.H.; Brentrup, J.A.; Knoll, L.B.; Mette, E.M.; Moeller, R.E. Ecological Consequences of Long-Term Browning in Lakes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilla, R.M.; Williamson, C.E.; Zhang, J.; Smyth, R.L.; Lenters, J.D.; Brentrup, J.A.; Knoll, L.B.; Fisher, T.J. Browning-Related Decreases in Water Transparency Lead to Long-Term Increases in Surface Water Temperature and Thermal Stratification in Two Small Lakes. JGR Biogeosci. 2018, 123, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.C.; Verdan, I.; Silva, M.E.S.; Oscar-Júnior, A.C.; Ambrizzi, T. South Atlantic Convergence Zone and ENSO Occurrence in the 2000–2021 Period. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2024, 155, 7079–7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M.G.; Hamilton, D.P.; Trolle, D.; Muraoka, K.; McBride, C. Spatial Heterogeneity in Geothermally-Influenced Lakes Derived from Atmospherically Corrected Landsat Thermal Imagery and Three-Dimensional Hydrodynamic Modelling. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 50, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar-Sebens, M.; Li, L.; Song, K.; Xie, S. On the Use of Landsat-5 TM Satellite for Assimilating Water Temperature Observations in 3D Hydrodynamic Model of Small Inland Reservoir in Midwestern US. Adv. Remote Sens. 2013, 2, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracchini, T.; Chu, P.Y.; Šukys, J.; Lieberherr, G.; Wunderle, S.; Wüest, A.; Bouffard, D. Data Assimilation of in Situ and Satellite Remote Sensing Data to 3D Hydrodynamic Lake Models: A Case Study Using Delft3D-FLOW v4.03 and OpenDA v2.4. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaheri, A.; Babbar-Sebens, M.; Miller, R.N. From Skin to Bulk: An Adjustment Technique for Assimilation of Satellite-Derived Temperature Observations in Numerical Models of Small Inland Water Bodies. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 92, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duka, M.A.; Bernardo, T.L.B.; Casim, N.C.I.; Tamayo, L.V.Q.; Monterey, M.L.E.; Yokoyama, K. Understanding Stratification and Turnover Dynamics of a Tropical Lake Using Extensive Field Observations and 3D Hydrodynamic Simulations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, G.; Filho, W.P.; De Carvalho, L.A.S.; Trindade, P.M.P.; Da Rosa, C.N.; Dezordi, R. Performance and Validation of Water Surface Temperature Estimates from Landsat 8 of the Itaipu Reservoir, State of Paraná, Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Images | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Landsat 5 | Landsat 8 | Landsat 9 | Dry Period | Wet Period | |

| 0 d: all samples | 12 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 2 |

| 0 d: abs error ≤ 2 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 2 |

| 1 d: all samples | 27 | 6 | 18 | 3 | 22 | 5 |

| 1 d: abs error ≤ 2 | 26 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 21 | 5 |

| 2 d: all samples | 41 | 18 | 20 | 3 | 35 | 6 |

| 2 d: abs error ≤ 2 | 40 | 18 | 19 | 3 | 34 | 6 |

| Metrics | 95% Confidence Interval | Bias | Std Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | (0.8513, 0.9565) | −1.69 × 10−3 | 0.03 |

| RMSE | (0.4950, 0.7214) | −1.69 × 10−2 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, A.R.; Cicerelli, R.E.; de Almeida, A.; de Almeida, T.; Koide, S. Four Decades of Thermal Monitoring in a Tropical Urban Reservoir Using Remote Sensing: Trends, Climatic and External Drivers of Surface Water Warming in Lake Paranoá, Brazil. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3603. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213603

Pereira AR, Cicerelli RE, de Almeida A, de Almeida T, Koide S. Four Decades of Thermal Monitoring in a Tropical Urban Reservoir Using Remote Sensing: Trends, Climatic and External Drivers of Surface Water Warming in Lake Paranoá, Brazil. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(21):3603. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213603

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Alice Rocha, Rejane Ennes Cicerelli, Andréia de Almeida, Tati de Almeida, and Sergio Koide. 2025. "Four Decades of Thermal Monitoring in a Tropical Urban Reservoir Using Remote Sensing: Trends, Climatic and External Drivers of Surface Water Warming in Lake Paranoá, Brazil" Remote Sensing 17, no. 21: 3603. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213603

APA StylePereira, A. R., Cicerelli, R. E., de Almeida, A., de Almeida, T., & Koide, S. (2025). Four Decades of Thermal Monitoring in a Tropical Urban Reservoir Using Remote Sensing: Trends, Climatic and External Drivers of Surface Water Warming in Lake Paranoá, Brazil. Remote Sensing, 17(21), 3603. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213603