Bridging the Gap to Sustainability: How Culture and Context Shape Green Transparency in Chinese Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

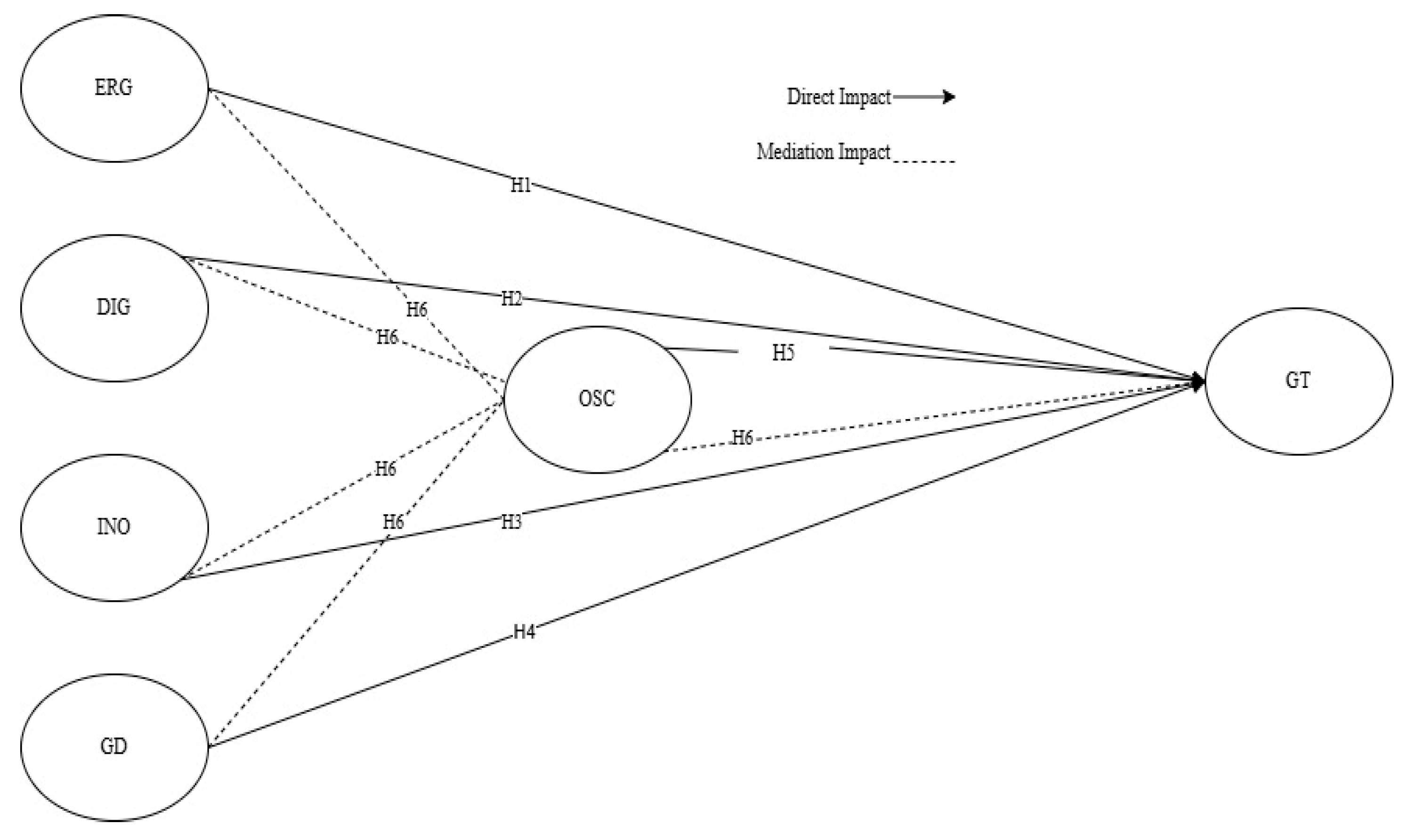

2. Hypothesis Development and Review of Literature

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Empirical Analysis

- Y and X are matrices of observed variables;

- Λy and Λx are matrices of factor loadings;

- B is a matrix of path coefficients among endogenous latent variables;

- Γ is a matrix of path coefficients between exogenous and endogenous latent variables;

- η and ξ are vectors of latent variable;

- ζ is a vector of residual terms.

4. Results

4.1. Validating Measurement Model

4.2. Direct Path Analysis

4.3. Mediation Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, P.; Imran, M.; Nadeem, M.; Haq, S.U. The Role of Environmental Law in Farmers’ Environment-Protecting Intentions and Behavior Based on Their Legal Cognition: A Case Study of Jiangxi Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, E.; Haq, S.U.; Aziz, B. Green Finance and Globally Competitive and Diversified Production: Powering Renewable Energy Growth and GHG Emission Reduction. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2025, 34, 1867–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, M.D.; Dimian, G.C.; Gradinaru, G.I. Green entrepreneurship in challenging times: A quantitative approach for European countries. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2023, 36, 1828–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Zhou, R.; Anwar, M.A.; Siddiquei, A.N.; Asmi, F. Entrepreneurs and environmental sustainability in the digital era: Regional and institutional perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T.A.; Benzie, M.; Börner, J.; Dawkins, E.; Fick, S.; Garrett, R.; Godar, J.; Grimard, A.; Lake, S.; Larsen, R.K.; et al. Transparency and sustainability in global commodity supply chains. World Dev. 2019, 121, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Transparency under scrutiny: Information disclosure in global environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Politics 2008, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michener, G.; Bersch, K. Identifying transparency. Inf. Polity 2013, 18, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheyle, N.; De Ville, F. How much is Enough? Explaining the continuous transparency conflict in TTIP. Politics Gov. 2013, 5, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, D.; Graham, M.; Fung, A. Targeting transparency. Science 2013, 340, 1410–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. Report of the Working Group on Transparency and Accountability; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/np/g22/taarep.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Hess, D. Social reporting and new governance regulation: The prospects of achieving corporate accountability through transparency. Bus. Ethics Q. 2007, 17, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. The legitimizing effect of social and environmental disclosures: A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.A.; Qiao, Y.; Li, X.; Li, S. Does improvement of environmental information transparency boost firms’ green innovation? Evidence from the air quality monitoring and disclosure program in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.Y.; Guo, C.Q.; Luu, B.V. Environmental, social and governance transparency and firm value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoang, T.H.; Przychodzen, W.; Przychodzen, J.; Segbotangni, E.A. Environmental transparency and performance: Does the corporate governance matter? Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 10, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Goodell, J.W.; Li, M.; Wang, Y. Environmental information transparency and green innovations. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2023, 86, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zeng, S.; Chen, H.; Meng, X.; Jin, Z. Monitoring effect of transparency: How does government environmental disclosure facilitate corporate environmentalism? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1594–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, B. How innovative knowledge assets and firm transparency affect sustainability-friendly practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinca, M.S.; Madaleno, M.; Baba, M.C.; Dinca, G. Environmental information transparency—Evidence from Romanian companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Pizzi, S.; Ligorio, L.; Leopizzi, R. Enhancing environmental information transparency through corporate social responsibility reporting regulation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3470–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Farooq, U.; Alam, M.M.; Dai, J. How does cultural diversity determine green innovation? New empirical evidence from Asia region. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber, T.B. The work of the symbolic in institutional processes: Translations of rational myths in Israeli high tech. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.J.; Zilber, T. Conversation at the border between organizational culture theory and institutional theory. J. Manag. Inq. 2012, 21, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, R.; Lim, W.M.; Sareen, M.; Kumar, S.; Panwar, R. Stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166, 114104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoskey, D.G.; Luo, Y.; Wang, J. Does board gender diversity affect the transparency of corporate political disclosure? Asian Rev. Account. 2018, 26, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, K.; Cassidy, H. As big scandals mount, experts say be truthful—and careful—in ads. (Strategy). Brandweek 2002, 43, 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Parris, D.L.; Dapko, J.L.; Arnold, R.W.; Arnold, D. Exploring transparency: A new framework for responsible business management. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. The ethical, social and environmental reporting-performance portrayal gap. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2004, 17, 731–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Thirty years of social accounting, reporting and auditing: What (if anything) have we learnt? Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2001, 10, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.; Wong, C.Y.; Boon-Itt, S.; Tang, A.K. Strategies for building environmental transparency and accountability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebinger, F.; Omondi, B. Leveraging digital approaches for transparency in sustainable supply chains: A conceptual paper. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Zicari, A.; Jabeen, F.; Bhatti, Z.A. How digitalization supports a sustainable business model: A literature review. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 187, 122146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Exploring how usage-focused business models enable circular economy through digital technologies. Sustainability 2023, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.; Reim, W. Reviewing literature on digitalization, business model innovation, and sustainable industry: Past achievements and future promises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellermann, D.; Fliaster, A.; Kolloch, M. Innovation risk in digital business models: The German energy sector. J. Bus. Strategy 2017, 38, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, E.; Rajala, R. Material intelligence as a driver for value creation in IoT-enabled business ecosystems. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, W.; Goleman, D.; O’Toole, J. Transparency: How Leaders Create a Culture of Candor; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov, V.; Verschraegen, G.; Van Assche, K. The limits of transparency: A systems theory view. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Heikkurinen, P. Transparency fallacy: Unintended consequences of stakeholder claims on responsibility in supply chains. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 318–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.M.; Gunasekaran, A. Sustainability development in high-tech manufacturing firms in Hong Kong: Motivators and readiness. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 137, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletič, M.; Maletič, D.; Gomišček, B. The impact of sustainability exploration and sustainability exploitation practices on the organisational performance: A cross-country comparison. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutz, M.A.; Sharma, S. Green Growth, Technology and Innovation. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (5932). Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/897251468156871535/green-growth-technology-and-innovation (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Luo, X.; Nipo, D.T.; Jaidi, J. Technological innovation and the quality of environmental information disclosure: Evidence from a-share companies listed on China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2023, 13, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, C.; Gonçalves, T.C. Gender diversity on the board and firms’ corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2022, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.M.; Kramer, V.W. How many women do boards need. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Heminway, J.M. Sex, trust, and corporate boards. Hastings Women’s Law J. 2007, 18, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adams, R.B.; Funk, P. Beyond the glass ceiling: Does gender matter? Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A.; Arshad, S.; Azeem, H.; Naseer, K.; Rehan, M. Shattering the glass ceiling: The unseen impact of gender diversity on financial transparency. Forum Econ. Financ. Stud. 2024, 2, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, E.; Alkayed, H.; Aly, D.A. The impact of gender diversity on digital reporting in the USA. Int. J. Digit. Account. Res. 2022, 22, 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.; Iskandar-Datta, M. Gender in the C-Suite and informational transparency. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2018, 15, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Suárez-Fernández, O.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Female directors and impression management in sustainability reporting. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khan, I.; Saeed, B.B. Does board diversity affect quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure? Evidence from Pakistan. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingbani, I.; Chithambo, L.; Tauringana, V.; Papanikolaou, N. Board gender diversity, environmental committee and greenhouse gas voluntary disclosures. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2194–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, R.A.; Maqsood, U.S.; Irshad, S.; Khan, M.K. The role of women on board in combatting greenwashing: A new perspective on environmental performance. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 34, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Olcina-Sempere, G.; López-Zamora, B. Female directorship on boards and corporate sustainability policies: Their effect on sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.; Webster, F.E., Jr. Organizational culture and marketing: Defining the research agenda. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. Business leaders’ personal values, organisational culture and market orientation. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Dollar, B.; Melián, V.; Van Durme, Y.; Wong, J. Global Human Capital Trends; The New Organization: Different by Design; Deloitte University Press: London, UK, 2016; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck, B.; Walker, K.; Caza, A. Antecedents of sustainable organizing: A look at the relationship between organizational culture and the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quantis. Organizational Culture: The Missing Link That Can Make or Break Your Sustainability Ambitions. Available online: https://quantis.com/news/organizational-culture-the-key-to-sustainable-business-transformation/#:~:text=An%20organization%E2%80%99s%20sustainability%20culture%20is%20its%20peoples%E2%80%99%20assumptions,it%20or%20not%2C%20your%20company%20already%20has%20one (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Mingaleva, Z.; Shironina, E.; Lobova, E.; Olenev, V.; Plyusnina, L.; Oborina, A. Organizational culture management as an element of innovative and sustainable development of enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth, R.; Tukiran, M.; Erlinagentari, R.E.G.; Wiguna, W.; Santoso, S.; Pratiwi, I. Digitalization beyond technology: Organisational culture sustainability and their change due to the pandemic (literature review). Int. J. Econ. Educ. Entrep. (IJE3) 2023, 3, 553–565. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, E.C.; Terblanche, F. Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2003, 6, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspersen, S. Understanding Compliance Behaviour in an Organisational Culture Context. Master’s Thesis, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua. Number of Listed Companies in China Reaches 5346 by End of 2023. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202402/03/content_WS65bdd86dc6d0868f4e8e3c12.html#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20companies%20listed%20on%20the%20country%27s,said%20a%20monthly%20report%20published%20by%20the%20association (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Thomas, G.; Hult, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. EzPATH: Causal Modeling; Systat: Evanston, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, L.T.; Fok, L.; Tsang, E.P.; Fang, W.; Tsang, H.Y. Understanding residents’ environmental knowledge in a metropolitan city of Hong Kong, China. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Gazi, M.A.I.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Rahaman, M.A. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, M.A.; Akhtaruddin, M. Factors affecting the voluntary disclosure: A study by using smart PLS-SEM approach. Int. J. Law Manag. 2018, 60, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, V.; Janković, I.; Vasić, V.; Ljumović, I. Does transparency pay off for green bond issuers? Evidence from EU state agencies’ green bonds. Ekon. Poljopr. 2023, 70, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, S.; Scannella, E. Corporate environmental disclosure in Europe: The effects of the regulatory environment. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.; Ortiz-Martínez, E.; Marin-Hernandez, S.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. How does the European Green Deal affect the disclosure of environmental information? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2766–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzillo, G.; Farina, E.; Cantone, C. The effects of regulation on social and environmental reporting. In Corporate Governance: Theory and Practice, Proceedings of the International Online Conference, Virtual, 26 May 2022; Mantovani, G.M., Kostyuk, A., Govorun, D., Eds.; Virtus Interpress: Sumy, Ukraine, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Zhang, B. Environmental regulation, emissions and productivity: Evidence from Chinese COD-emitting manufacturers. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 92, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Jiang, Q.; Mi, L. One-vote veto: The threshold effect of environmental pollution in China’s economic promotion tournament. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 185, 107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Symbol or substance? Environmental regulations and corporate environmental actions decoupling. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 346, 118950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo-Márquez, A.J.; González-González, J.M.; Zamora-Ramírez, C. An international empirical study of greenwashing and voluntary carbon disclosure. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, L. Voluntary climate action and credible regulatory threat: Evidence from the carbon disclosure project. J. Regul. Econ. 2019, 56, 188–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Enterprise digital transformation and green innovation. Ind. Eng. Innov. Manag. 2023, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xie, H. Digitalization transformation and enterprise green innovation: Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1361576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitoniene, S.; Kundeliene, K. Sustainability reporting: The environmental impacts of digitalization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Technology and Entrepreneurship (ICTE), Kaunas, Lithuania, 24–27 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, D.; Losa-Jonczyk, A. Building Digital Trust by Communicating Environmental, Social, and Governance Activities; Trust and Digital Business; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, T.; Sun, R.; Sun, G.; Song, Y. Effects of digital finance on green innovation considering information asymmetry: An empirical study based on Chinese listed firms. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 4399–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Hao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L. Moving toward sustainable development: The influence of digital transformation on corporate ESG performance. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, J. Research on the mechanism of digital transformation to improve enterprise environmental performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 3137–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriekhoe, O.I.; Oyeyemi, O.P.; Bello, B.G.; Omotoye, G.B.; Daraojimba, A.I.; Adefemi, A. Blockchain in supply chain management: A review of efficiency, transparency, and innovation. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, C.; Coll, A. The influence of technologies in increasing transparency in textile supply chains. Logistics 2023, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M.; Shaukat, A.; Qiu, Y.; Trojanowski, G. Environmental and social disclosures and firm risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakutnia, A.O.; Hayriyan, A. Transparency as competitive advantage of innovation driven companies. Bus. Ethics Leadersh. 2017, 1, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandker, M.; Lindquist, E.; Poultouchidou, A.; Gill, G.; Santos-Acuña, L.; Neeff, T.; Fox, J. Technological Innovation Driving Transparent Forest Monitoring and Reporting for Climate Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd0143en (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Al-Shaer, H.; Zaman, M. Board gender diversity and sustainability reporting quality. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2016, 12, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Cannella, A.A., Jr.; Harris, I.C. Women and racial minorities in the boardroom: How do directors differ? J. Manag. 2002, 28, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S.A.; Teh, B.H.; Ong, T.S.; Chong, L.L.; Abd Rahim, M.F.B.; Latief, R. How does green innovation strategy influence corporate financing? Corporate social responsibility and gender diversity play a moderating role. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.B.; dos Santos, J.I.A.S.; Costa, M.F.D.; Carraro, W.B.W.H. Breaking through the glass ceiling: Women on the board as a mechanism for greater environmental transparency. Int. J. Dev. Issues 2024, 23, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.I.; Pinheiro, P.; Fernandes, S. Gender diversity and climate disclosure: A tcfd perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, A.; Thenmozhi, M.; Nair, B.A.V.; Chawla, S.; Liu, J.S.C. Does Gender Diversity on the Board Matter for ESG Performance? ESG Frameworks for Sustainable Business Practices. In Advances in Logistics, Operations, and Management Science Book Series; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 194–209. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, D.A.S.R.; Oliva, E.C.; Kubo, E.K.M.; Parente, V.; Tanaka, K.T. Organizational culture and sustainability in Brazilian electricity companies. RAUSP Manag. J. 2018, 53, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covas, L. Modifying the organisational culture in order to increase the company’s level of sustainability. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2019, 13, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Galera, A.; Ruiz-Lozano, M.; Tirado-Valencia, P.; Ríos-Berjillos, A.D.L. Promoting Sustainability Transparency in European Local Governments: An Empirical Analysis Based on Administrative Cultures. Sustainability 2017, 9, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A. Corporate Sustainability and Organizational Culture. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B. Corporate environmentalism: The construct and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.; Joseph, M.; Blodgett, J. Toward the creation of an eco-oriented corporate culture: A proposed model of internal and external antecedents leading to industrial firm eco-orientation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2004, 19, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. How organizational green culture influences green performance and competitive advantage: The mediating role of green innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Is skilled immigration always good for growth in the receiving economy? Econ. Lett. 2010, 108, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Transportation costs and the Great Divergence. Macroecon. Dyn. 2016, 20, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Mode | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Regulations (ERG) | 3.65 | |

| ERG1 | 3 | 3.01 |

| ERG2 | 4 | 3.67 |

| ERG3 | 4 | 3.89 |

| ERG4 | 4 | 3.22 |

| ERG5 | 4 | 3.75 |

| ERG6 | 5 | 4.79 |

| ERG7 | 4 | 3.44 |

| ERG8 | 4 | 3.57 |

| ERG9 | 3 | 3.88 |

| ERG10 | 5 | 4.58 |

| Digitalization (DIG) | 3.87 | |

| DIG1 | 4 | 3.67 |

| DIG2 | 4 | 3.92 |

| DIG3 | 5 | 4.67 |

| DIG4 | 4 | 3.88 |

| DIG5 | 4 | 3.75 |

| DIG6 | 4 | 3.83 |

| DIG7 | 4 | 3.68 |

| DIG8 | 4 | 3.77 |

| DIG9 | 4 | 3.69 |

| Innovativeness (INO) | 3.54 | |

| INO1 | 4 | 3.77 |

| INO2 | 4 | 3.81 |

| INO3 | 3 | 2.85 |

| INO4 | 4 | 3.69 |

| INO5 | 4 | 3.28 |

| INO6 | 4 | 3.73 |

| INO7 | 4 | 3.63 |

| Gender Diversity (GD) | 4.01 | |

| GD1 | 5 | 4.78 |

| GD2 | 4 | 3.66 |

| GD3 | 4 | 3.82 |

| GD4 | 4 | 3.59 |

| GD5 | 5 | 4.62 |

| GD6 | 4 | 3.73 |

| GD7 | 4 | 3.82 |

| Organizational Sustainability Culture (OSC) | 4.27 | |

| OSC1 | 5 | 4.63 |

| OSC2 | 4 | 3.87 |

| OSC3 | 5 | 4.59 |

| OSC4 | 4 | 3.96 |

| OSC5 | 4 | 3.59 |

| OSC6 | 5 | 4.71 |

| OSC7 | 4 | 3.91 |

| OSC8 | 5 | 4.93 |

| Green Transparency (GT) | 3.33 | |

| GT1 | 4 | 3.62 |

| GT2 | 4 | 3.71 |

| GT3 | 4 | 3.28 |

| GT4 | 4 | 3.58 |

| GT5 | 3 | 2.81 |

| GT6 | 3 | 2.94 |

| GT7 | 3 | 2.78 |

| GT8 | 4 | 3.63 |

| GT9 | 4 | 3.61 |

| Constructs | Factor Loadings | Cronbach Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Regulations (ERG) | 0.835 | 0.958 | 0.698 | |

| ERG1 | 0.945 | |||

| ERG2 | 0.935 | |||

| ERG3 | 0.927 | |||

| ERG4 | 0.916 | |||

| ERG5 | 0.894 | |||

| ERG6 | 0.866 | |||

| ERG7 | 0.849 | |||

| ERG8 | 0.837 | |||

| ERG9 | 0.825 | |||

| ERG10 | 0.829 | |||

| Digitalization (DIG) | 0.812 | 0.950 | 0.680 | |

| DIG1 | 0.946 | |||

| DIG2 | 0.927 | |||

| DIG3 | 0.917 | |||

| DIG4 | 0.895 | |||

| DIG5 | 0.864 | |||

| DIG6 | 0.839 | |||

| DIG7 | 0.827 | |||

| DIG8 | 0.819 | |||

| DIG9 | 0.801 | |||

| Innovativeness (INO) | 0.822 | 0.937 | 0.679 | |

| INO1 | 0.944 | |||

| INO2 | 0.929 | |||

| INO3 | 0.935 | |||

| INO4 | 0.901 | |||

| INO5 | 0.883 | |||

| INO6 | 0.867 | |||

| INO7 | 0.834 | |||

| Gender Diversity (GD) | 0.806 | 0.924 | 0.635 | |

| GD1 | 0.945 | |||

| GD2 | 0.938 | |||

| GD3 | 0.917 | |||

| GD4 | 0.873 | |||

| GD5 | 0.859 | |||

| GD6 | 0.841 | |||

| GD7 | 0.826 | |||

| Organizational Sustainability Culture (OSC) | 0.825 | 0.941 | 0.666 | |

| OSC1 | 0.945 | |||

| OSC2 | 0.917 | |||

| OSC3 | 0.894 | |||

| OSC4 | 0.867 | |||

| OSC5 | 0.849 | |||

| OSC6 | 0.832 | |||

| OSC7 | 0.819 | |||

| OSC8 | 0.810 | |||

| Green Transparency (GT) | 0.831 | 0.935 | 0.615 | |

| GT1 | 0.946 | |||

| GT2 | 0.928 | |||

| GT3 | 0.925 | |||

| GT4 | 0.900 | |||

| GT5 | 0.893 | |||

| GT6 | 0.864 | |||

| GT7 | 0.829 | |||

| GT8 | 0.810 | |||

| GT9 | 0.807 | |||

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | ||||||

| Constructs | ERG | DIG | INO | GD | OSC | GT |

| ERG | 0.835 | |||||

| DIG | 0.352 | 0.825 | ||||

| INO | 0.463 | 0.352 | 0.824 | |||

| GD | 0.273 | 0.164 | 0.174 | 0.797 | ||

| OSC | 0.187 | 0.262 | 0.163 | 0.352 | 0.816 | |

| GT | 0.372 | 0.415 | 0.173 | 0.165 | 0.261 | 0.784 |

| Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||||

| Constructs | ERG | DIG | INO | GD | OSC | GT |

| ERG | ||||||

| DIG | 0.243 | |||||

| INO | 0.415 | 0.362 | ||||

| GD | 0.267 | 0.263 | 0.273 | |||

| OSC | 0.371 | 0.176 | 0.362 | 0.173 | ||

| GT | 0.462 | 0.263 | 0.173 | 0.362 | 0.276 | |

| Fitness Tests | χ2/df | CFI | GFI | AGFI | NFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical values | <3.0 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.08 |

| Computed values | 2.11 | 0.941 | 0.925 | 0.927 | 0.915 | 0.051 |

| Paths | Beta-Value | Std. Err. | t-Value | f2 | Q2 | R2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERG → OSC | 0.104 | 0.026 | 3.944 | 0.483 | 0.203 | 0.564 | Accepted |

| DIG → OSC | 0.107 | 0.032 | 3.353 | 0.575 | 0.264 | 0.653 | Accepted |

| INO → OSC | 0.356 | 0.056 | 6.335 | 1.094 | 0.323 | 0.687 | Accepted |

| GD → OSC | 0.464 | 0.152 | 3.041 | 2.448 | 0.418 | 0.786 | Accepted |

| ERG → GT | 0.483 | 0.173 | 2.792 | 0.862 | 0.225 | 0.648 | Accepted |

| DIG → GT | 0.382 | 0.084 | 4.531 | 0.982 | 0.352 | 0.623 | Accepted |

| INO → GT | 0.502 | 0.103 | 4.874 | 1.419 | 0.370 | 0.732 | Accepted |

| GD → GT | 0.027 | 0.012 | 2.258 | 0.486 | 0.229 | 0.587 | Accepted |

| OSC → GT | 0.392 | 0.052 | 7.538 | 1.635 | 0.231 | 0.754 | Accepted |

| Paths | Beta-Value | Std. Err. | t-Value | p-Value | C.I. | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERG → OSC → GT | 0.041 | 0.009 | 4.670 | 0.000 | 0.001, 0.189 | accepted |

| DIG → OSC → GT | 0.042 | 0.010 | 4.165 | 0.000 | 0.007, 0.203 | accepted |

| INO → OSC → GT | 0.140 | 0.037 | 3.800 | 0.000 | 0.095, 0.271 | accepted |

| GD → OSC → GT | 0.182 | 0.029 | 6.180 | 0.000 | 0.055, 0.301 | accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y. Bridging the Gap to Sustainability: How Culture and Context Shape Green Transparency in Chinese Firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031157

Zhang Y. Bridging the Gap to Sustainability: How Culture and Context Shape Green Transparency in Chinese Firms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(3):1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031157

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuan. 2025. "Bridging the Gap to Sustainability: How Culture and Context Shape Green Transparency in Chinese Firms" Sustainability 17, no. 3: 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031157

APA StyleZhang, Y. (2025). Bridging the Gap to Sustainability: How Culture and Context Shape Green Transparency in Chinese Firms. Sustainability, 17(3), 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031157