Digital Nudges and Environmental Concern in Shaping Sustainable Consumer Behavior Aligned with SDGs 12 and 13

Abstract

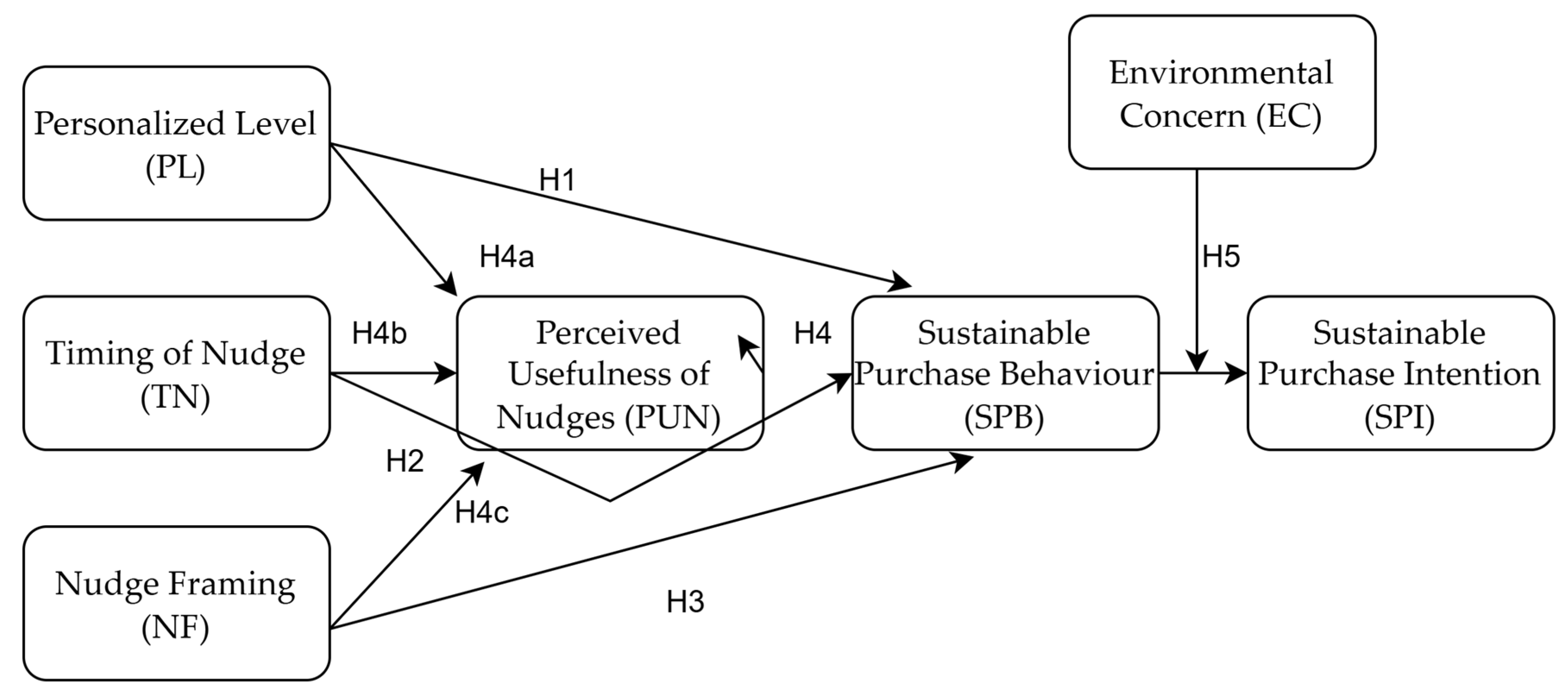

1. Introduction

- Research Question 1: What is the role of AI in driving nudge towards sustainable purchase intention and behavior?

- Research Question 2: What is the role of perceived usefulness towards purchase intention and behavior?

- Research Question 3: How do AI–driven digital nudges comply with SDGs 12 and 13?

- Research Question 4: What is the relationship between sustainable purchase intention and sustainable purchase in the presence of Environmental Concern as a moderator?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Anchoring

2.2. Gap Identification

2.3. Incorporation of the New Trends

2.4. Synthesis of Constructs

2.4.1. AI-Personalized Nudges

2.4.2. Timing of Nudges

2.4.3. Nudge Framing

2.4.4. Perceived Nudge Usefulness

2.4.5. Sustainable Purchase Intention and Behavior

2.4.6. Environmental Concern

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Measurement of Constructs

3.3. Sampling Strategy and Collection of Data

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

3.5. Ethical Considerations

3.6. Data Interpretation

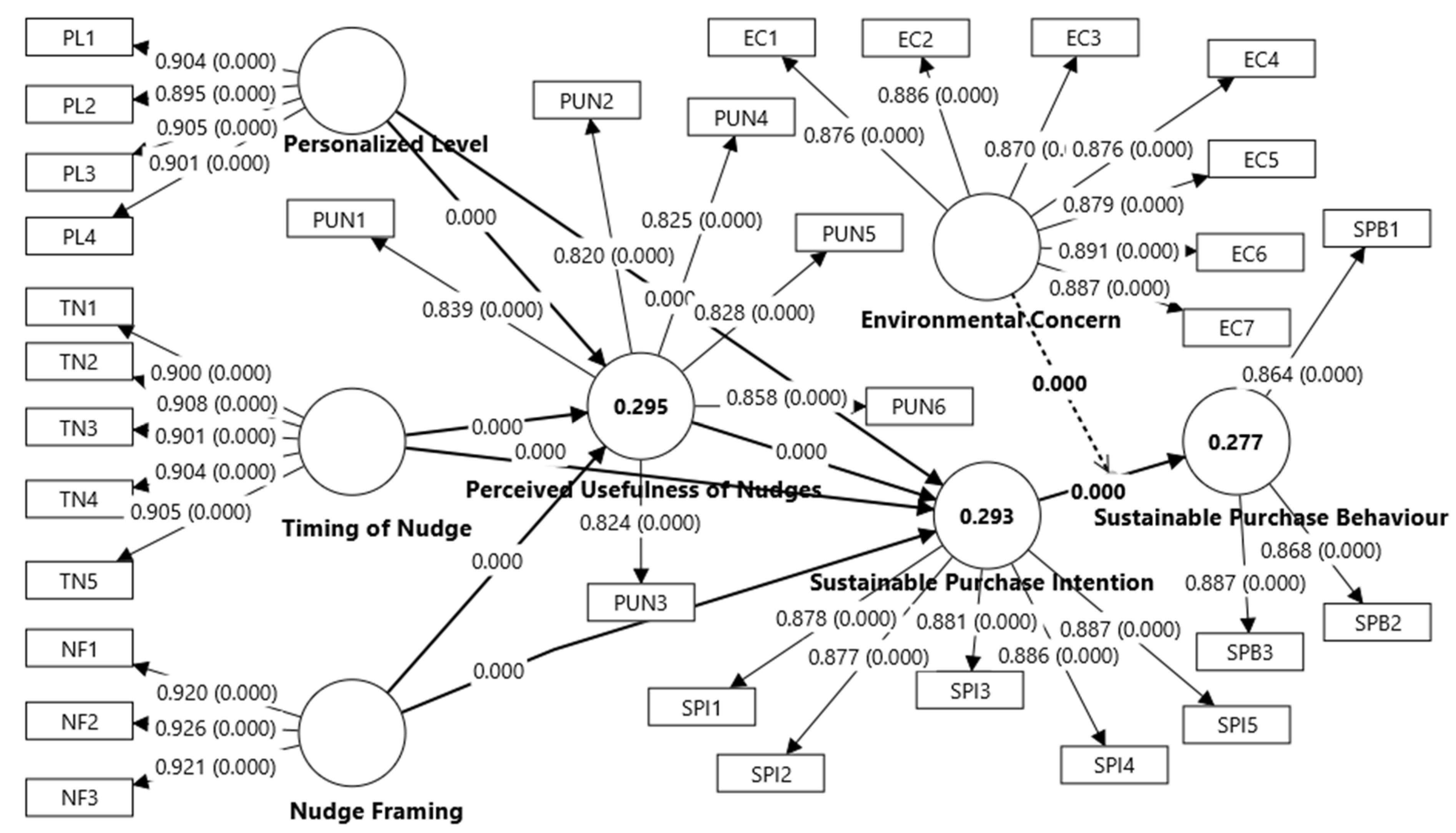

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

4.1. Model Fit Evaluation

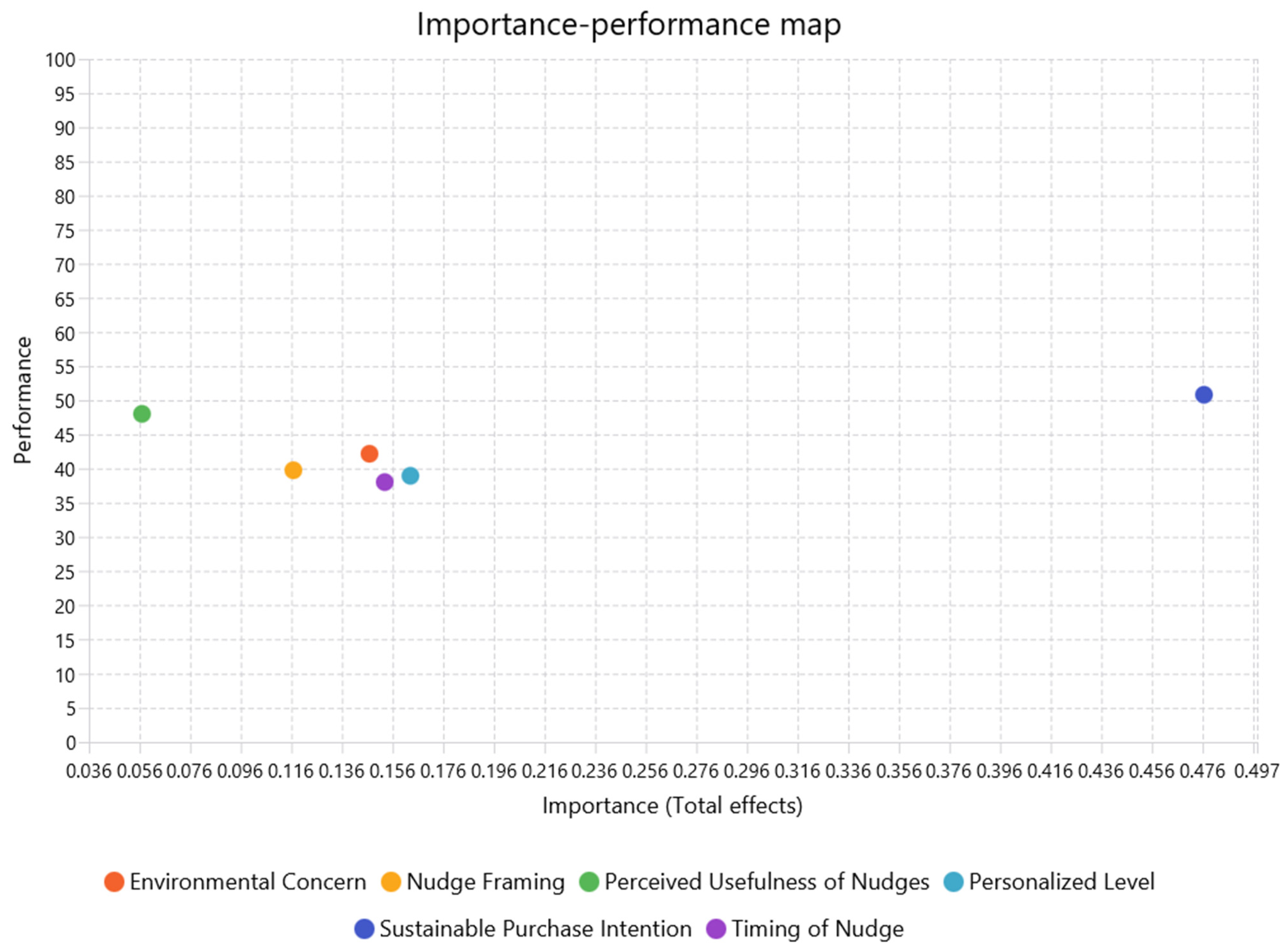

4.2. Importance–Performance Map Analysis (IPMA)

5. Discussion

5.1. Psychological Sustainability Intention Activators of Individualization and Timing

5.2. Framing and Perceived Usefulness Effects in Behavior Formation

5.3. Intention-Behavior Relationship and Environmental Concern Moderation

5.4. What It Means to AI-Powered Sustainable Consumption

Limitations & Future Avenues of Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form | Context/Meaning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence | Core term in digital interventions |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model | Theoretical framework |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals | United Nations’ global goals |

| SPI | Sustainable Purchase Intention | Dependent variable |

| SPB | Sustainable Purchase Behavior | Dependent variable |

| PL | Personalized Level | Independent construct |

| TN | Timing of Nudge | Independent construct |

| NF | Nudge Framing | Independent construct |

| PUN | Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | Mediating variable |

| EC | Environmental Concern | Moderating variable |

| IPMA | Importance–Performance Map Analysis | Advanced PLS-SEM analysis |

| SEM-PLS | Structural Equation Modeling–Partial Least Squares | Data analysis technique |

| PU | Perceived Usefulness | TAM construct |

| PEU | Perceived Ease of Use | TAM construct (mentioned conceptually) |

| SD | Standard Deviation | Statistical term |

| CR | Composite Reliability | Measurement model metric |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted | Convergent validity |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio | Discriminant validity |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor | Multicollinearity check |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual | Model fit index |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index | Model fit index |

| d_ULS | Unweighted Least Squares Discrepancy | Model fit index |

| d_G | Geodesic Discrepancy | Model fit index |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination | Structural model |

| Q2 | Predictive Relevance | Model predictive power |

| β | Path Coefficient | Structural equation output |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change | If mentioned in literature context |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council | If referred to Saudi regional context |

| CMB | Common Method Bias | Measurement bias check |

Appendix A

| Construct | Code | Item Statement | Scale (1–5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personalized Level (PL) | PL1 | The digital platform provides sustainability messages that match my personal preferences. | 1 = Strongly Disagree → 5 = Strongly Agree |

| PL2 | The personalized nudges I receive feel relevant and tailored to my needs. | ||

| PL3 | The system effectively customizes recommendations based on my previous behavior. | ||

| PL4 | I find personalized nudges more effective than general sustainability messages. | ||

| Timing of Nudge (TN) | TN1 | The sustainability reminders appear at the right time before I make a purchase. | |

| TN2 | I find timely nudges helpful in making better purchasing decisions. | ||

| TN3 | Receiving sustainability messages at convenient moments improves my decision-making. | ||

| TN4 | I am more likely to act sustainably when nudges are delivered at appropriate times. | ||

| Nudge Framing (NF) | NF1 | The sustainability messages emphasize positive outcomes of my actions. | |

| NF2 | The way messages are framed influences my motivation to act sustainably. | ||

| NF3 | Clear and persuasive framing makes sustainability messages more effective. | ||

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges (PUN) | PUN1 | The sustainability nudges help me make better purchasing decisions. | |

| PUN2 | I find the nudges valuable for identifying eco-friendly options. | ||

| PUN3 | The nudges make my shopping experience easier and more efficient. | ||

| PUN4 | I consider these digital nudges useful for promoting sustainable consumption. | ||

| PUN5 | The sustainability nudges motivate me to act in environmentally responsible ways. | ||

| Sustainable Purchase Intention (SPI) | SPI1 | I intend to buy eco-friendly products in the future. | |

| SPI2 | I prefer sustainable options when choosing products. | ||

| SPI3 | I am willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. | ||

| SPI4 | I plan to support brands that promote sustainable practices. | ||

| SPI5 | Digital nudges influence my willingness to choose sustainable products. | ||

| Sustainable Purchase Behaviour (SPB) | SPB1 | I frequently purchase products that are certified as sustainable. | |

| SPB2 | I consistently choose options that reduce environmental impact. | ||

| SPB3 | I make efforts to purchase from companies that follow eco-friendly practices. | ||

| Environmental Concern (EC) | EC1 | I am aware of the environmental challenges facing our planet. | |

| EC2 | I am concerned about the harm human activities cause to the environment. | ||

| EC3 | I believe it is everyone’s responsibility to protect the environment. | ||

| EC4 | I actively support products and companies that are environmentally responsible. | ||

| EC5 | I have changed aspects of my lifestyle to reduce environmental harm. | ||

| EC6 | Governments and organizations should enforce policies to protect the environment. | ||

| EC7 | I worry about the long-term environmental consequences of unsustainable behavior. |

Appendix B

| Constructs | Original sample (O) | Sample mean (M) | Standard deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Concern -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.147 | 0.148 | 0.034 | 4.360 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Concern x Sustainable Purchase Intention -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.142 | 0.141 | 0.031 | 4.609 | 0.000 |

| Nudge Framing -> Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.303 | 0.303 | 0.027 | 11.427 | 0.000 |

| Nudge Framing -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.117 | 0.117 | 0.016 | 7.444 | 0.000 |

| Nudge Framing -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.245 | 0.245 | 0.028 | 8.726 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.016 | 3.504 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.119 | 0.119 | 0.033 | 3.630 | 0.000 |

| Personalized Level -> Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.322 | 0.323 | 0.027 | 11.852 | 0.000 |

| Personalized Level -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.163 | 0.164 | 0.018 | 9.249 | 0.000 |

| Personalized Level -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.342 | 0.342 | 0.028 | 12.426 | 0.000 |

| Sustainable Purchase Intention -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.476 | 0.478 | 0.024 | 20.117 | 0.000 |

| Timing of Nudge -> Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.312 | 0.312 | 0.028 | 11.236 | 0.000 |

| Timing of Nudge -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.153 | 0.153 | 0.014 | 10.589 | 0.000 |

| Timing of Nudge -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.321 | 0.321 | 0.027 | 11.934 | 0.000 |

Appendix C

| Path coefficients | Alpha 1% | Alpha 5% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Concern -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.147 | 0.977 | 0.996 |

| Environmental Concern x Sustainable Purchase Intention -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.142 | 0.967 | 0.994 |

| Nudge Framing -> Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.303 | 1 | 1 |

| Nudge Framing -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.209 | 1 | 1 |

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.119 | 0.882 | 0.969 |

| Personalized Level -> Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.322 | 1 | 1 |

| Personalized Level -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.303 | 1 | 1 |

| Sustainable Purchase Intention -> Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.476 | 1 | 1 |

| Timing of Nudge -> Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.312 | 1 | 1 |

| Timing of Nudge -> Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.283 | 1 | 1 |

Appendix D

| Model | Core Constructs | Strengths | Limitations | Relevance Compared to TAM–Nudge Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAM (Technology Acceptance Model) | Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use | Strong predictor of technology adoption; simple and widely validated | Focuses mainly on cognitive evaluations; limited consideration of behavioral biases | Forms the cognitive foundation of this study; explains the rational evaluation of AI-enabled nudges |

| TPB (Theory of Planned Behavior) | Attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control | Explains intention formation influenced by social norms and perceived control | Does not account for digital design elements or choice architecture | Useful for intention modeling, but does not explain how nudges influence behavior |

| TRA (Theory of Reasoned Action) | Attitude, subjective norms | Good for predicting intentions in stable environments | Limited relevance in digital contexts; lacks behavioral mechanisms | Less suitable for AI-enabled or nudged decision environments |

| UTAUT (Unified Theory of Acceptance & Use of Technology) | Performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions | Strong explanatory power; integrates multiple models | Complex; requires many moderating variables | Useful for adoption but does not explain micro-level decision shifts caused by nudges |

| Nudge Theory | Defaults, framing, heuristics, social cues | Explains actual behavioral shifts; effective in sustainability contexts | Does not capture cognitive evaluations of technology | Complements TAM by explaining how design influences behavior beyond cognition |

| Dual-Process Models (e.g., System 1 & System 2) | Automatic vs. deliberate decision-making | Explains intuitive vs. reflective choices | Hard to operationalize in digital interfaces | Supports the role of nudges but does not link to technology acceptance |

| Behavioral Economics Models | Loss aversion, choice architecture, heuristics | Explains real-world deviations from rationality | Not technology-focused | Reinforces the need for nudges but lacks integration with technology adoption constructs |

| Value–Belief–Norm Theory | Environmental values, personal norms | Strong predictor of pro-environmental behavior | Not suitable for technology-specific contexts | Explains environmental concern but not digital adoption processes |

Appendix E

| SDG | Consumer Behaviors Aligned With the SDG | How AI-Driven Nudges Support These Behaviors | Relevant Constructs in This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 12—Responsible Consumption & Production |

|

| Personalization, Framing, Timing, Perceived Usefulness → Sustainable Purchase Intention |

| SDG 13—Climate Action |

|

| Environmental Concern (Moderator), Sustainable Purchase Behavior |

References

- Anuardo, R.G.; Espuny, M.; Costa, A.C.F.; Espuny, A.L.G.; Kazançoğlu, Y.; Kandsamy, J.; de Oliveira, O.J. Transforming E-Waste into Opportunities: Driving Organizational Actions to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Dwivedi, J.; Mathur, A. The Role of Behavioral Economics in Consumer Decision-Making Towards Sustainable Products. In Nudging Green: Behavioral Economics and Environmental Sustainability; World Sustainability Series; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume Part F3319, pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Alnyme, O.; Heldt, T. Testing the effectiveness of increased frequency of norm-nudges in encouraging sustainable tourist behaviour: A field experiment using actual and self-reported behavioural data. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1307–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulītis, A.; Silkāne, V.; Ozola, A.K. Enhancing sustainable consumer behaviour through Nudging: Insights from a field experiment on adoption of electronic receipts. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2025, 74, 101548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balconi, M.; Acconito, C.; Rovelli, K.; Angioletti, L. Influence of and Resistance to Nudge Decision-Making in Professionals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieskol, P.; Jakobi, T.; von Grafenstein, M. From consent to control by closing the feedback loop: Enabling data subjects to directly compare personalized and non-personalized content through an On/Off toggle. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2025, 59, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Bergianti, F.; Gabrielli, V.; Baghi, I. The effect of message framing on young adult consumers’ sustainable fashion consumption: The role of anticipated emotions and perceived ethicality. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemken, D.; Wahnschafft, S.; Eggers, C. Public acceptance of default nudges to promote healthy and sustainable food choices. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujalli, A.; Wani, M.J.G.; Almgrashi, A.; Khormi, T.; Qahtani, M. Investigating the factors affecting the adoption of cloud accounting in Saudi Arabia’s small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruyobeza, B.; Grobbelaar, S.S.; Botha, A. Forecasting the adoption of digital health technologies: The intention-expectation gap. Eval. Program Plan. 2025, 112, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettler, F.M.; Schumacher, J.-P.; Hammer, J.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding Digital Nudging for Overcoming Inertia Related to Sustainable Investment Decisions: An Experimental Study. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13132-025-02797-4 (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Wani, M.J.G.; Loganathan, N.; Mujalli, A. The impact of sustainable development goals (SDGs) on tourism growth. Empirical evidence from G-7 countries. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2397535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.; Shaw, P.J.; Richards, B.; Clegg, Z.; Smith, D. What nudge techniques work for food waste behaviour change at the consumer level? A systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Wang, W.H.; Huerta de Soto, J. Principles of Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Decision-Making for Behavioral Development Economics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartmann, M. The Ethics of AI-Powered Climate Nudging—How Much AI Should We Use to Save the Planet? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avasilcăi, S.; Tudose, M.B.; Gall, G.V.; Grădinaru, A.-G.; Rusu, B.; Avram, E. Digital Technologies to Support Sustainable Consumption: An Overview of the Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochi, P.; Pandya, K.; Lindberg, K.B.; Korpås, M. Social Nudging for Sustainable Electricity Use: Behavioral Interventions in Energy Conservation Policy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.; Amarilli, S. Feeding the behavioral revolution: Contributions of behavior analysis to nudging and vice versa. J. Behav. Econ. Policy 2018, 2, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Granato, G.; Mugge, R. Leveraging social norms for sustainable behaviour: How the exposure to static-and-dynamic-norms encourages sufficiency and consumption reduction of fashion. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 108, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, C.; Schulte, J.; Hallstedt, S. Implementing sustainability in product portfolio development through digitalization and a game-based approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 40, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolón-Canedo, V.; Morán-Fernández, L.; Cancela, B.; Alonso-Betanzos, A. A review of green artificial intelligence: Towards a more sustainable future. Neurocomputing 2024, 599, 128096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, D.; Tsekouropoulos, G. Sustainable Consumption and Branding for Gen Z: How Brand Dimensions Influence Consumer Behavior and Adoption of Newly Launched Technological Products. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Della Sciucca, M.; Gastaldi, M.; Lupi, B. Indicator Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; de Barcellos, M.D.; De Steur, H. The role of nudges in food choices: An umbrella review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 134, 105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, C.A.; Luppi, L.; Veiga, R.T. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in the pro-environmental behavior context: A longitudinal study about water conservation. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 524, 146499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehawy, Y.M.; Ali Khan, S.M.F. Consumer readiness for green consumption: The role of green awareness as a moderator of the relationship between green attitudes and purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention-behavior gap. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, T.; Arora, D.S. Influence Without Intrusion: Decoding the Role of Digital Nudging in Shaping Online Decisions. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezer, A.; Bodur, H.O. The greenconsumption effect: How using green products improves consumption experience. J. Consum. Res. 2021, 47, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalufi, N.A.M.; Sheikh, R.A.; Khan, S.M.; Onn, C.W. Evaluating the Impact of Sustainability Practices on Customer Relationship Quality: An SEM-PLS Approach to Align with SDG. Sustainability 2025, 17, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Mateus, R.; Silvestre, J.D.; Roders, A.P. Going beyond Good Intentions for the Sustainable Conservation of Built Heritage: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Lee, D.; Lee, S.W. Does Attitude or Intention Affect Behavior in Sustainable Tourism? A Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Suhluli, S. Generative AI and Cognitive Challenges in Research: Balancing Cognitive Load, Fatigue, and Human Resilience. Technologies 2025, 13, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.; Ali Khan, S.M. Assessing Consumer Behavior in Sustainable Product Markets: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach with Partial Least Squares Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderas, M. Artificial Intelligence for Sustainability: A Systematic Review and Critical Analysis of AI Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.; Spinelli, R. Decoding sustainable drivers: A systematic literature review on sustainability-induced consumer behaviour in the fast fashion industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 55, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmali, F.H.; Khan, S.M.; Hakim, T. IoT-Enabled Digital Nudge Architecture for Sustainable Energy Behavior: An SEM-PLS Approach. Technologies 2025, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehawy, Y.M.; Faisal Ali Khan, S.M.; Khalufi, N.A.M.; Abdullah, R.S. Customer adoption of robot: Synergizing customer acceptance of robot-assisted retail technologies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A.; Kolny, B.; Kucia, M. Smart Homes as Catalysts for Sustainable Consumption: A Digital Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.J.; Kang, E. Employee environmental capability and its relationship with corporate culture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley, D.; Wilson, G.T. Integrating ethics into design for sustainable behaviour. J. Des. Res. 2013, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Škare, V.; Dosen, D.O. Is AI-based digital marketing ethical? Assessing a new data privacy paradox. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersinas, K.; Bada, M.; Furnell, S. Cybersecurity behavior change: A conceptualization of ethical principles for behavioral interventions. Comput. Secur. 2025, 148, 104025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.; Faisal Ali Khan, S.M. Integrating IT and Sustainability in Higher Education Infrastructure: Impacts on Quality, Innovation and Research. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2023, 22, 210–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.; Ali Khan, S.M.F. Sustainability-Infused Learning Environments: Investigating the Role of Digital Technology and Motivation for Sustainability in Achieving Quality Education. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 23, 519–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, R.; Andersen, A. Recommendations with a Nudge. Technologies 2019, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniuk, S.; Grabowska, S.; Gajdzik, B.Z. Personalization of products in the industry 4.0 concept and its impact on achieving a higher level of sustainable consumption. Energies 2020, 13, 5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniuk, S.; Grabowska, S.; Straka, M. Identification of Social and Economic Expectations: Contextual Reasons for the Transformation Process of Industry 4.0 into the Industry 5.0 Concept. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Z. The Impact of Big Data-Driven Strategies on Sustainable Consumer Behaviour in E-Commerce: A Green Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swani, K.; Labrecque, L.; Markos, E. Are B2B data breaches concerning? Consequences of buyer’s or firm’s data loss on buyer and supplier related outcomes. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 119, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plak, S.; van Klaveren, C.; Cornelisz, I. Raising student engagement using digital nudges tailored to students’ motivation and perceived ability levels. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 554–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wu, L.; Long, F.; Ma, A. Exploiting user behavior learning for personalized trajectory recommendations. Front. Comput. Sci. 2022, 16, 163610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, B.; Jafarian, A.; Abdi, Z. Nudging towards sustainability: A comprehensive review of behavioral approaches to eco-friendly choice. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R.; Reisch, L.A.; Kaiser, M. Trusting nudges? Lessons from an international survey. J. Eur. Public Policy 2019, 26, 1417–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Shehawy, Y.M. Perceived AI Consumer-Driven Decision Integrity: Assessing Mediating Effect of Cognitive Load and Response Bias. Technologies 2025, 13, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, M.; Chu, M. Why is green consumption easier said than done? Exploring the green consumption attitude-intention gap in China with behavioral reasoning theory. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, A.; Tuimala, J.; Hammar, M. Enhancing the adoption of digital public services: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesoph, A.; Hoffmann, S.; Merk, C.; Rehdanz, K.; Schmidt, U. Guess what …?—How guessed norms nudge climate-friendly food choices in real-life settings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemken, D. Options to design more ethical and still successful default nudges: A review and recommendations. Behav. Public Policy 2024, 8, 349–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelez, J.; Wang, F.; Shreedhar, G. For the love of money and the planet: Experimental evidence on co-benefits framing and food waste reduction intentions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 192, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Xiao, J.; Ge, D.; Xin, L.; Gao, J.; He, S.; Hu, H.; Carlsson, J.G. JD.com: Operations Research Algorithms Drive Intelligent Warehouse Robots to Work. Interfaces 2022, 52, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozen, I.; Raedts, M.; Meijburg, L. Do verbal and visual nudges influence consumers’ choice for sustainable fashion? J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2021, 12, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperbauer, T.J. The permissibility of nudging for sustainable energy consumption. Energy Policy 2017, 111, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, G.; Supino, S.; Grimaldi, M.; Troisi, O. Exploring the political-institutional perspective of sustainable consumer behavior within the circular economy: A structural equation modeling approach from nudge theory. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2025, 100, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Sarigöllü, E. Is bigger better? How the scale effect influences green purchase intention: The case of washing machine. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, P.; Kwofie, E.M.; Baum, J.I.; Wang, D. Insights from consumers’ exposure to environmental nutrition information on a dashboard for improving sustainable healthy food choices. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 16, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Wieland, D.A.C. I Tell You What You Want, What You Really, Really Want: Digital Information Nudging as Bridge towards a Sustainable Purchase Decision. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Americas Conference on Information Systems, Panama City, Panama, 10–12 August 2023. AMCIS 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alyahya, M.; Agag, G.; Aliedan, M.; Abdelmoety, Z.H. Understanding the factors affecting consumers’ behaviour when purchasing refurbished products: A chaordic perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossin, M.A.; Xiong, S.; Alemzero, D.; Abudu, H. Analyzing the Progress of China and the World in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals 7 and 13. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frommeyer, B.; Wagner, E.; Hossiep, C.R.; Schewe, G. The utility of intention as a proxy for sustainable buying behavior—A necessary condition analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 143, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Chandra, B. Models for Predicting Sustainable Durable Products Consumption Behaviour: A Review Article. Vision 2020, 24, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelo, E.; Casalegno, C.G.; Civera, C. Digital transformation or analogic relationships? A dilemma for small retailer entrepreneurs and its resolution. J. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 15, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, L.; Jalal, R.N.-U.-D. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior impact on renewables investments: A moderating role of environmental concerns. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2025, 101, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, B.L.; De Fátima Salgueiro, M.; Rita, P. Accessibility and trust: The two dimensions of consumers’ perception on sustainable purchase intention. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guath, M.; Stikvoort, B.; Juslin, P. Nudging for eco-friendly online shopping—Attraction effect curbs price sensitivity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S.; Panagiotarou, A.; Rigou, M. Impact of Environmental Concern, Emotional Appeals, and Attitude toward the Advertisement on the Intention to Buy Green Products: The Case of Younger Consumer Audiences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D.K. How environmental concerns influence consumers’ anticipated emotions towards sustainable consumption: The moderating role of regulatory focus. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O. Factors influencing generation Y green behaviour on green products in Nigeria: An application of theory of planned behaviour. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2022, 13, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolleston, C.; Nyerere, J.; Brandli, L.; Lagi, R.; McCowan, T. Aiming Higher? Implications for Higher Education of Students’ Views on Education for Climate Justice. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, D.; Qian, J.; Li, Z. The Impact of Green Purchase Intention on Compensatory Consumption: The Regulatory Role of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, M.V.; Manalo, A.J.J.; Nadela, M.B.F.; Ngan, K.D.C.; Oyco, J.E.D. To Green or Not to Green: An Analysis of Green Purchase Intention among Fashion Brand Consumers using a Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2025, 14, 733–747. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, M. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, A.R.; Yuan, L.; Feng, X.; Webb, E.; Hsieh, C.J. Digital Nudging: Numeric and Semantic Priming in E-Commerce. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 37, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsch, T.; Lehrer, C.; Jung, R. Digital Nudging: Altering User Behavior in Digital Environments. In Proceedings of the 13 Internationalen Tagung Wirtschaftsinformatik (WI 2017), St. Gallen, Switzerland, 12–15 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Lathabai, H.H.; Nedungadi, P. Sustainable development goal 12 and its synergies with other SDGs: Identification of key research contributions and policy insights. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview—Vision 2030. Saudi Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/overview (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Truijens, D. Coherence between theory and policy in Nudge and Boost: Is it relevant for evidence-based policy-making? Ration. Soc. 2022, 34, 368–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. PLS-SEM Statistical Programs: A Review. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2021, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinner, I.; Johnson, E.J.; Goldstein, D.G.; Liu, K. Partitioning default effects: Why people choose not to choose. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2011, 17, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazi, M.; Namazi, N.R. An empirical investigation of the effects of moderating and mediating variables in business research: Insights from an auditing report. Contemp. Econ. 2017, 11, 459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Bohlen, G.M.; Diamantopoulos, A. The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, W.; Jin, Z.; Wang, Z. Influence of Environmental Concern and Knowledge on Households’ Willingness to Purchase Energy-Efficient Appliances: A Case Study in Shanxi, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, P.; Isaksson, O.; Maier, A.; Summers, J. Sampling in design research: Eight key considerations. Des. Stud. 2022, 78, 101077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.; Khan, S.M.F.A. Understanding deep learning across academic domains: A structural equation modelling approach with a partial least squares approach. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2024, 7, 1389–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C.; Boudreaux, M.; Oglesby, M. Can Harman’s single-factor test reliably distinguish between research designs? Not in published management studies. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2024, 33, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuberth, F.; Rademaker, M.E.; Henseler, J. Assessing the overall fit of composite models estimated by partial least squares path modeling. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 57, 1678–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Set Correlation and Contingency Tables. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 12, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Ding, B.; Guan, C.; Ding, D. Generative AI: A systematic review using topic modelling techniques. Data Inf. Manag. 2024, 8, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.B.; Wang, C.-K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Hoang, N.C.; Hai, L.N. Exploring behavioral dynamics in sustainable choices: Ethical insights from an emerging market. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 19, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Siwar, C.; Halim, S.A. Purchase intention of renewable energy technology in rural areas in Bangladesh: Empirical evidence. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauff, S.; Richter, N.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Importance and performance in PLS-SEM and NCA: Introducing the combined importance-performance map analysis (cIPMA). J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, G.; D’Adamo, I.; Di Leo, S.; Gastaldi, M.; Scarcelli, M. Advancing Sustainable Development Through Integrated Photovoltaic and Battery Energy Storage Systems in Commercial Buildings: A Strategic, Economic, and Environmental Perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 9144–9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.; Ruettgers, N.; Hasler, A.; Sonderegger, A.; Sauer, J. Questionnaire experience and the hybrid System Usability Scale: Using a novel concept to evaluate a new instrument. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2021, 147, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magno, F.; Cassia, F.; Ringle, C.M. A brief review of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) use in quality management studies. TQM J. 2022, 36, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.S.; Perng, S.K. A note on the consistency of the modified fisher prediction function. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1986, 13, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Longfor, N.R.; Dong, L.; Qian, X. Beyond theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis of psychological and contextual determinants of household waste separation. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 116, 108087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct/Theory | References | Core Concept | Identified Research Gap | Linked Hypothesis | Relevant SDGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) | [13,14,74] | Adoption depends on perceived usefulness and ease of use. | Limited integration of TAM with behavioral/digital interventions for sustainability. | — (Foundational Theory) | SDG 9, SDG 12 |

| Nudge Theory | [15,16,85] | Nudges influence behavior without restricting choice. | Long-term sustainability outcomes and ethics of nudging remain underexplored. | — (Foundational Theory) | SDG 12, SDG 13 |

| Digital Nudging | [2,46,86,87] | Digital environments provide context-aware nudges supporting sustainable choices. | Limited empirical testing on how AI cues shape cognitive beliefs in sustainability decisions. | Framework-level construct | SDG 12, SDG 13, SDG 9 |

| Personalization | [6,50,52] | Tailored messages increase engagement, trust, and intention. | Need to ensure personalization supports sustainability while protecting autonomy/control. | H1: Personalization → SPI | SDG 12 |

| Timing of Nudges | [3,56] | Well-timed nudges increase effectiveness and compliance. | Optimal contextual timing is understudied in digital sustainability nudges. | H2: Timing → SPI | SDG 12 |

| Framing of Nudges | [7,61,65,67] | Gain-framed and norm-based messages encourage pro-environmental choices. | Cross-cultural validation and ethical transparency require more evidence. | H3: Framing → SPI | SDG 12, SDG 13 |

| Perceived Usefulness | [68,69] | If nudges are seen as beneficial, intention strengthens. | Mediating role of usefulness is rarely tested in AI–sustainability models. | H4: PU mediates Nudge → SPI | SDG 9, SDG 12 |

| Sustainable Purchase Intention (SPI) | [73,88] | Willingness to choose environmentally friendly products. | Intention–behavior gap persists; digital nudging effects need more testing. | Core DV | SDG 12 |

| Sustainable Purchase Behavior (SPB) | [30] | Actual pro-environmental purchasing actions. | Few studies link AI nudges to real consumer actions/behavior. | Outcome variable | SDG 12, SDG 13 |

| Environmental Concern (Moderator) | [76,79,80,83,89] | Strong ecological concern can intensify responses to sustainability nudges. | Mixed evidence across contexts and cultures. | H5: EC moderates SPI → SPB | SDG 13 |

| Integration with SDGs / Vision 2030 | [90,91] | Sustainability agendas require behavioral change and digital innovation. | Limited empirical integration of AI + behavior + SDG measurement in one model. | Policy alignment | SDG 12, SDG 13, SDG 9, SDG 7 |

| Personalized Level | 4 | Perception of tailored nudges, relevance of personalized messages, alignment with preferences, and effectiveness of customization | [85,87] |

| Timing of Nudge | 4 | Appropriateness of timing, reminders before purchase, influence of timely cues, and convenience of intervention | [87,95] |

| Nudge Framing | 3 | Positive vs. negative framing, gain vs. loss emphasis, clarity of framed message | [85,96] |

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 5 | Ease of decision-making, helpfulness, perceived value, support in sustainable choice, clarity, motivation | [13,87] |

| Sustainable Purchase Intention | 5 | Willingness to buy eco-friendly products, preference for sustainable options, readiness to pay more, long-term intention, influence of nudges | [88,97] |

| Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 3 | Actual eco-friendly buying actions, frequency of green purchases, and consistency in sustainable choices | [30,98] |

| Environmental Concern (Moderator) | 7 | Awareness of environmental issues, concern about ecological harm, responsibility to act, support for eco-products, lifestyle adjustments, policy support, future concern | [89,99] |

| Constructs/Paths | α | ρₐ | ρ_c | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | VIF Range | Path Coefficient | Power (α = 1%) | Power (α = 5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Environmental Concern (EC) | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 3.18–3.50 | → Sustainable Purchase Behavior | 0.977 | 0.996 | ||||||

| 2. Nudge Framing (NF) | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 2.91–3.31 | → Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 1 | 1 | |||||

| → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3. Perceived Usefulness of Nudges (PUN) | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 2.23–2.54 | → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.882 | 0.969 | ||||

| 4. Personalized Level (PL) | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.90 | 3.01–3.16 | → Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 1 | 1 | |||

| → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5. Sustainable Purchase Behaviour (SPB) | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.87 | 1.95–2.12 | ← Sustainable Purchase Intention | 1 | 1 | ||

| 6. Sustainable Purchase Intention (SPI) | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 2.80–3.09 | — | — | — | |

| 7. Timing of Nudge (TN) | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 3.47–3.69 | → Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 1 | 1 |

| → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 8. EC × SPI (Interaction) | — | — | — | — | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 1.00 | → Sustainable Purchase Behavior | 0.967 | 0.994 |

| Constructs/Indices | R2 | Adj. R2 | Q2 Predict | RMSE | MAE | SRMR | d_ULS | d_G | χ2 | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.68 | |||||

| Sustainable Purchase Behavior | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.86 | 0.65 | |||||

| Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.85 | 0.67 | |||||

| Model Fit (Saturated) | 0.028 | 0.449 | 0.252 | 1296.16 | 0.943 | |||||

| Model Fit (Estimated) | 0.064 | 2.326 | 0.328 | 1555.05 | 0.932 |

| Hypothesis | Path Relationship | β (O) | t-Value | p-Value | f2 | Effect Size | Decision | SDG Linkage |

| H1 | Personalized Level → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.303 | 10.495 | 0.000 | 0.113 | Medium | Accepted | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption and Production |

| H2 | Timing of Nudge → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.283 | 9.980 | 0.000 | 0.100 | Medium | Accepted | SDG 13—Climate Action |

| H3 | Nudge Framing → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.209 | 7.003 | 0.000 | 0.054 | Small—Medium | Accepted | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption and Production |

| H4 | Perceived Usefulness of Nudges → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.064 | 3.524 | 0.000 | 0.014 | Small | Accepted | SDG 4—Quality Education/Awareness for Sustainability |

| H4a | Personalized Level → Perceived Usefulness → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.038 | 3.12 | 0.002 | Significant | Partial | Accepted | SDG 4—Quality Education (Awareness) |

| H4b | Timing of Nudge → Perceived Usefulness → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.037 | 3.04 | 0.002 | Significant | Partial | Accepted | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption |

| H4c | Nudge Framing → Perceived Usefulness → Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.036 | 2.98 | 0.003 | Significant | Partial | Accepted | SDG 13—Climate Action |

| H5 | Environmental Concern × Sustainable Purchase Intention → Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | 0.142 | 4.609 | 0.000 | 0.030 | Small | Accepted | SDG 13—Climate Action |

| Target Construct | Predictor Variable | Importance (Total Effect) | Performance Score | Aligned SDG | Priority Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | Nudge Framing | 0.303 | 39.752 | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption | High |

| Personalization Level | 0.322 | 38.941 | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption | High | |

| Timing of Nudge | 0.312 | 38.017 | SDG 13—Climate Action | High | |

| Sustainable Purchase Intention | Nudge Framing | 0.245 | 39.752 | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption | Moderate |

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.119 | 48.015 | SDG 4—Quality Education (Sustainability Awareness) | Low | |

| Personalization Level | 0.342 | 38.941 | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption | High | |

| Timing of Nudge | 0.321 | 38.017 | SDG 13—Climate Action | High | |

| Sustainable Purchase Behaviour | Environmental Concern | 0.147 | 42.165 | SDG 13—Climate Action | Moderate |

| Nudge Framing | 0.117 | 39.752 | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption | Low | |

| Perceived Usefulness of Nudges | 0.057 | 48.015 | SDG 4—Quality Education | Low | |

| Personalization Level | 0.163 | 38.941 | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption | Moderate | |

| Sustainable Purchase Intention | 0.476 | 50.815 | SDG 13—Climate Action | Very High | |

| Timing of Nudge | 0.153 | 38.017 | SDG 13—Climate Action | Moderate |

| Implication Type | Key Insight (Human Language) | Theoretical/Practical Contribution | Aligned SDGs | Relevance and Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Combining TAM and behavioral principles offers a comprehensive explanation of how and why consumers adopt AI-based sustainable technologies. | Extends TAM beyond technology perception to include behavioral triggers from Nudge Theory. | SDG 12 & SDG 13 | Strengthens academic understanding of digital sustainability models, especially within the Saudi context. |

| Environmental concern plays a motivational role, transforming intention into real behavior by appealing to moral responsibility. | Adds an ethical and emotional dimension to the integrated TAM framework. | SDG 13 | Supports the development of climate-conscious behavioral theories for sustainable consumption research. | |

| Managerial | Personalizing AI-driven digital interventions increases user engagement and promotes green purchase decisions. | Enhances perceived usefulness (TAM) while applying behavioral design principles. | SDG 12 | Helps businesses develop consumer-tailored AI systems that drive responsible buying. |

| Delivering AI prompts at the right time improves decision confidence and increases responsiveness to sustainable choices. | Connects real-time behavioral cues with user experience principles. | SDG 13 | Encourages firms to use predictive data to activate sustainable consumer actions at critical decision points. | |

| Transparent and positively framed sustainability messages build customer trust and encourage ethical engagement. | Supports normative influence in Nudge Theory and enhances perceived trustworthiness in TAM. | SDG 4 & SDG 12 | Fosters ethical communication strategies in digital sustainability initiatives. | |

| Policy | Promoting environmental awareness through education strengthens the link between intention and real sustainable behavior. | Integrates moral responsibility within technology adoption frameworks. | SDG 13 & SDG 4 | Supports Vision 2030 goals to cultivate environmentally responsible citizens through education. |

| AI sustainability strategies should incorporate personalization and ethical standards to ensure accountability. | Links digital transformation with fair governance and responsible innovation. | SDG 12 & SDG 13 | Enables policymakers to design inclusive and transparent digital sustainability frameworks. | |

| Collaboration among academia, government, and industry is essential to embed sustainability into technology innovation. | Extends TAM by promoting collective adoption and knowledge diffusion. | SDG 4 & SDG 13 | Supports human capital development for a digitally sustainable economy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khalufi, N.A.M. Digital Nudges and Environmental Concern in Shaping Sustainable Consumer Behavior Aligned with SDGs 12 and 13. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411292

Khalufi NAM. Digital Nudges and Environmental Concern in Shaping Sustainable Consumer Behavior Aligned with SDGs 12 and 13. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411292

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhalufi, Nasser Ali M. 2025. "Digital Nudges and Environmental Concern in Shaping Sustainable Consumer Behavior Aligned with SDGs 12 and 13" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411292

APA StyleKhalufi, N. A. M. (2025). Digital Nudges and Environmental Concern in Shaping Sustainable Consumer Behavior Aligned with SDGs 12 and 13. Sustainability, 17(24), 11292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411292