Optimal Operation Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Using Electric Vehicle Agent-Based Model Considering Operational Profitability

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- It introduces a behavior-aware operational approach that quantifies EV behavioral dynamics and translates them into real-time flexibility indicators via the BFT, establishing a direct connection between human mobility patterns and system operation.

- (2)

- It develops a unified data-driven framework combining behavioral simulation, renewable forecasting, and two-stage optimization for realistic VPP coordination under uncertainty.

- (3)

- It demonstrates, through an integrated simulation using empirical travel data, ERA5 meteorological data, and market prices, that the proposed approach enhances both profitability and operational stability by leveraging EV-based flexibility.

2. Modeling Framework

2.1. AB-TCC Model

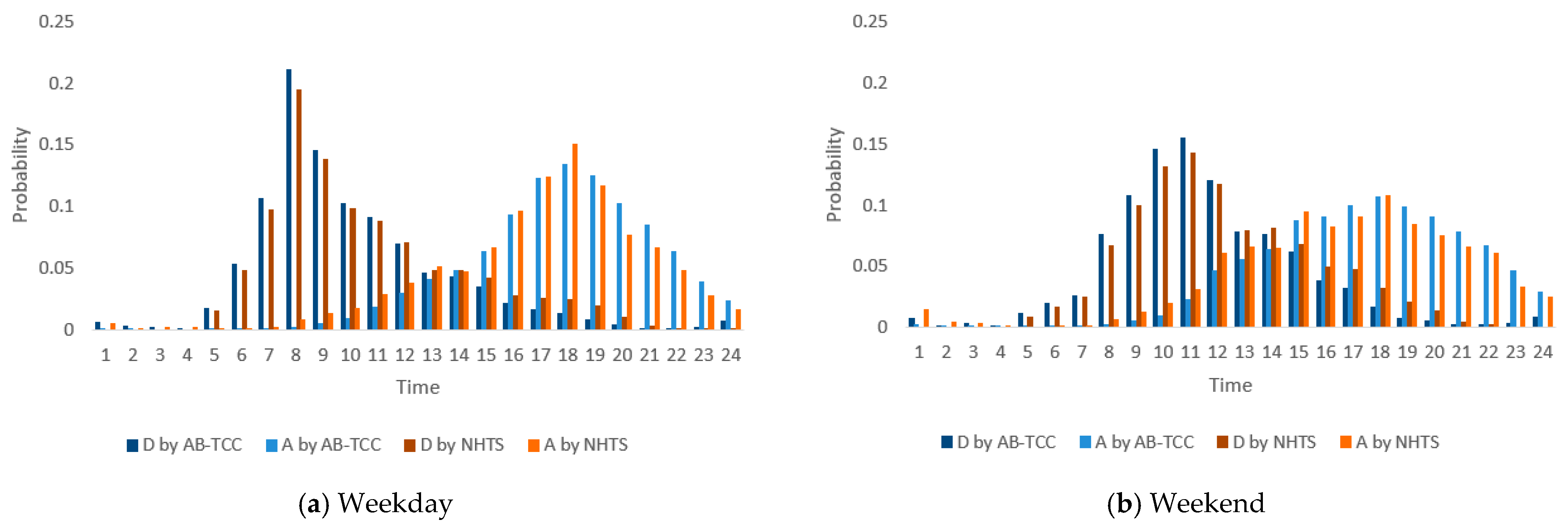

2.1.1. Trip Data and Probability Distributions

2.1.2. Trip and Charging Chain Generation

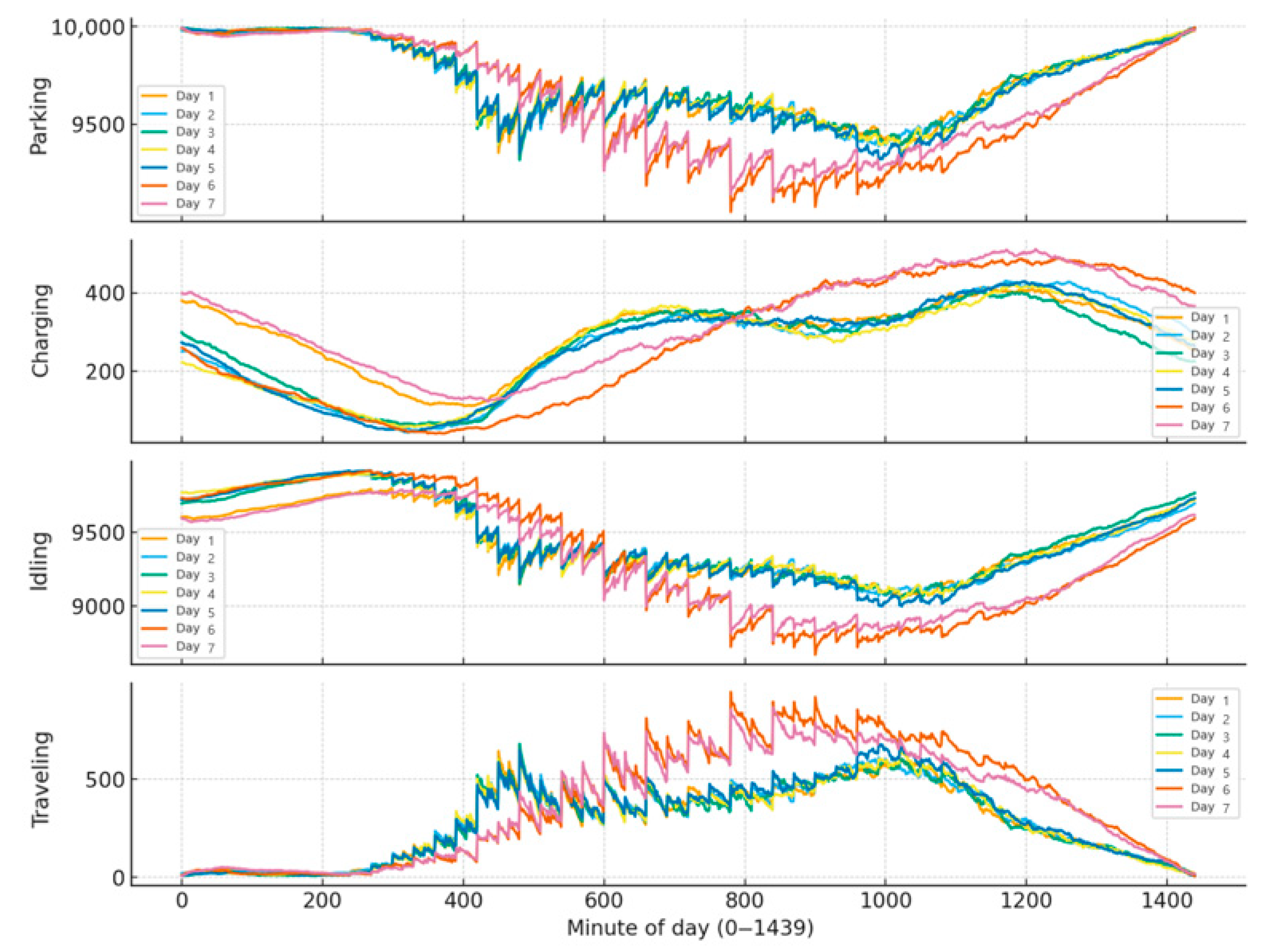

2.1.3. Aggregated Outputs and Behavioral Flexibility Trace

2.2. Wind Forecasting Model

2.2.1. Spatio-Temporal Structure and Dataset

2.2.2. Feature Engineering

2.2.3. Data Preprocessing and Sequence Formation

2.2.4. Model Architecture and Training Configuration

2.2.5. Forecasting, Evaluation, and Rationale

2.3. Two-Stage VPP Optimization Model

2.3.1. Day-Ahead Optimization

2.3.2. Real-Time Optimization

3. Case Study and Numerical Results

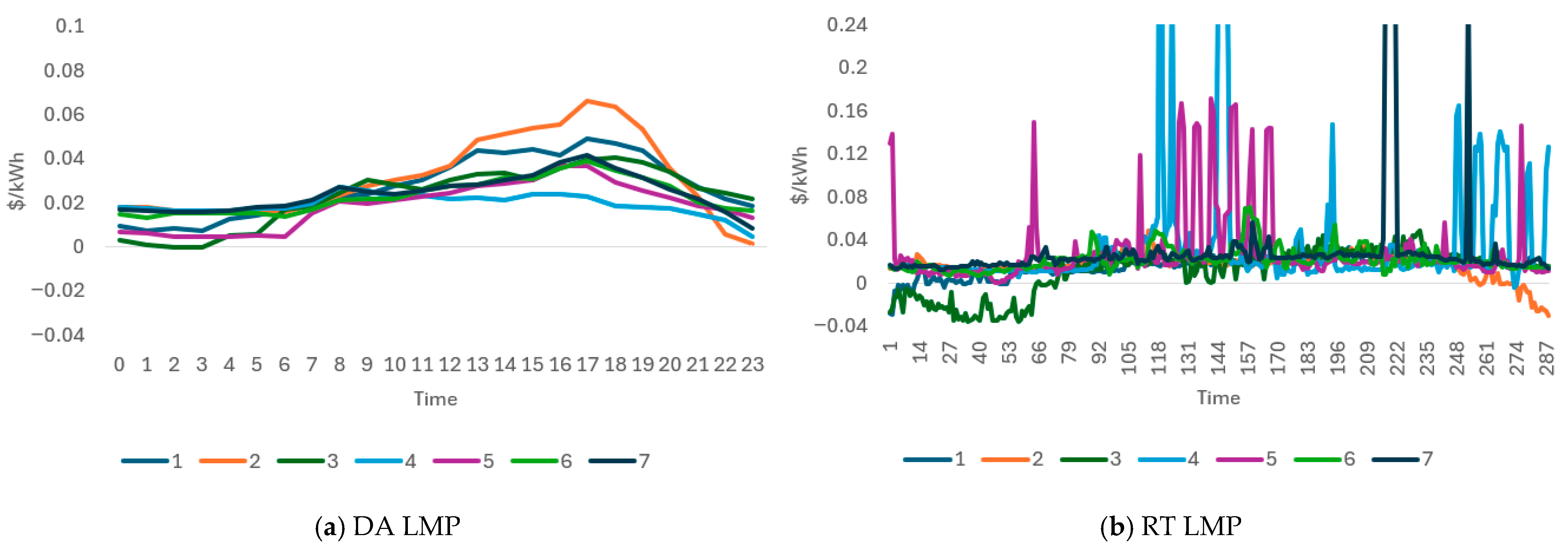

3.1. Simulation Setup and Data Description

3.2. EV Behavioral Dynamics and Flexibility Traces

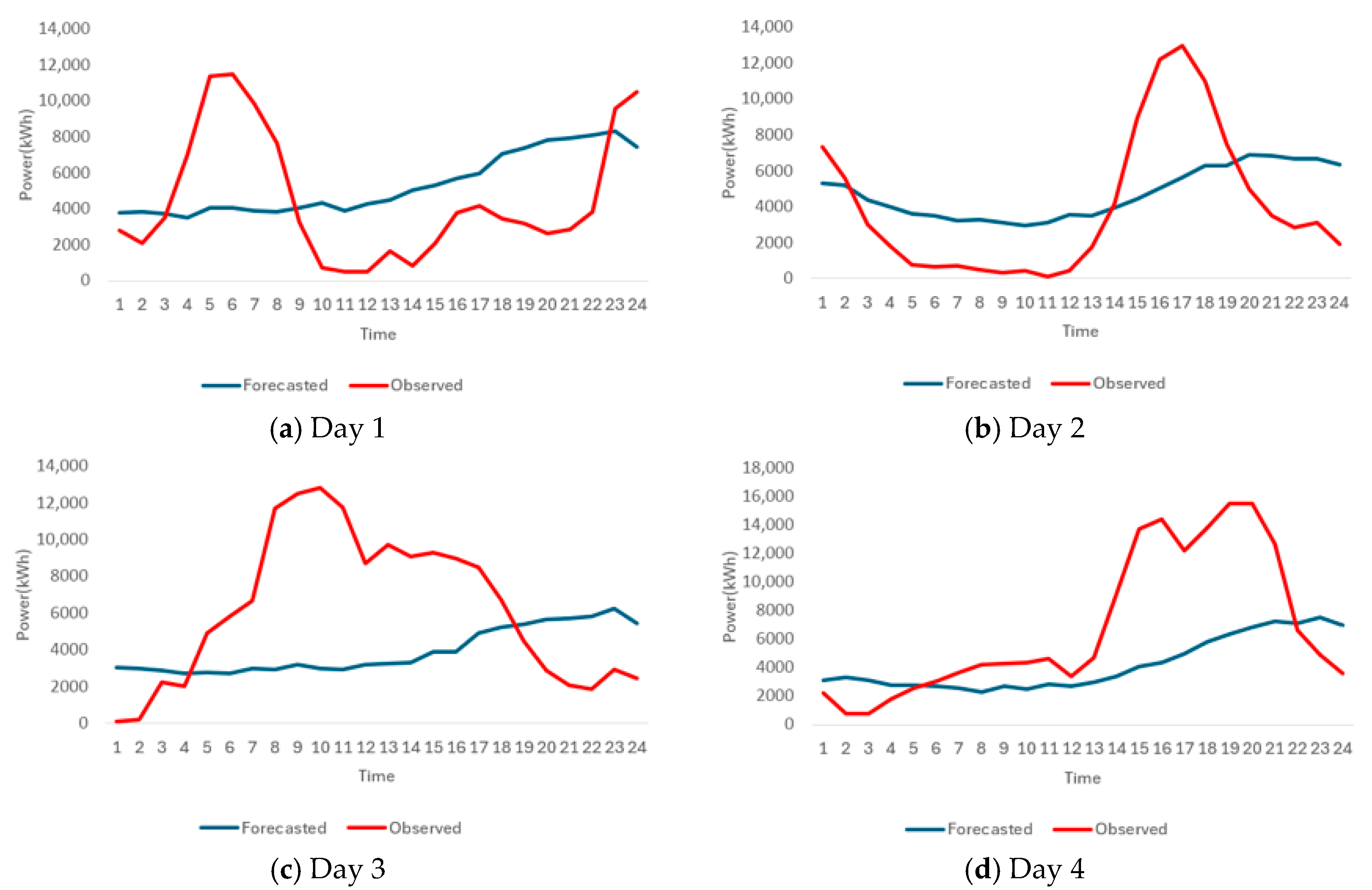

3.3. Wind Power Forecasting Results

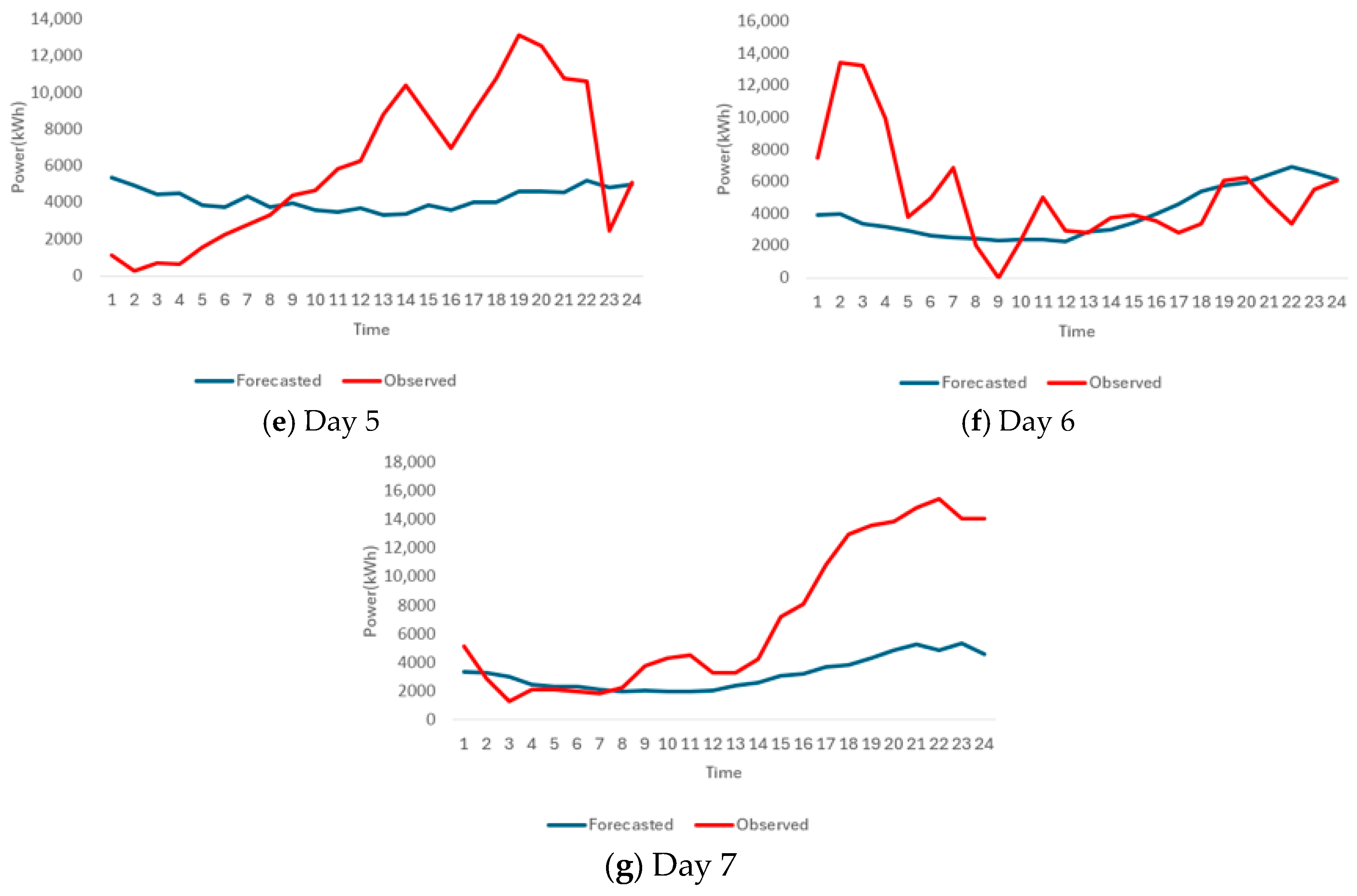

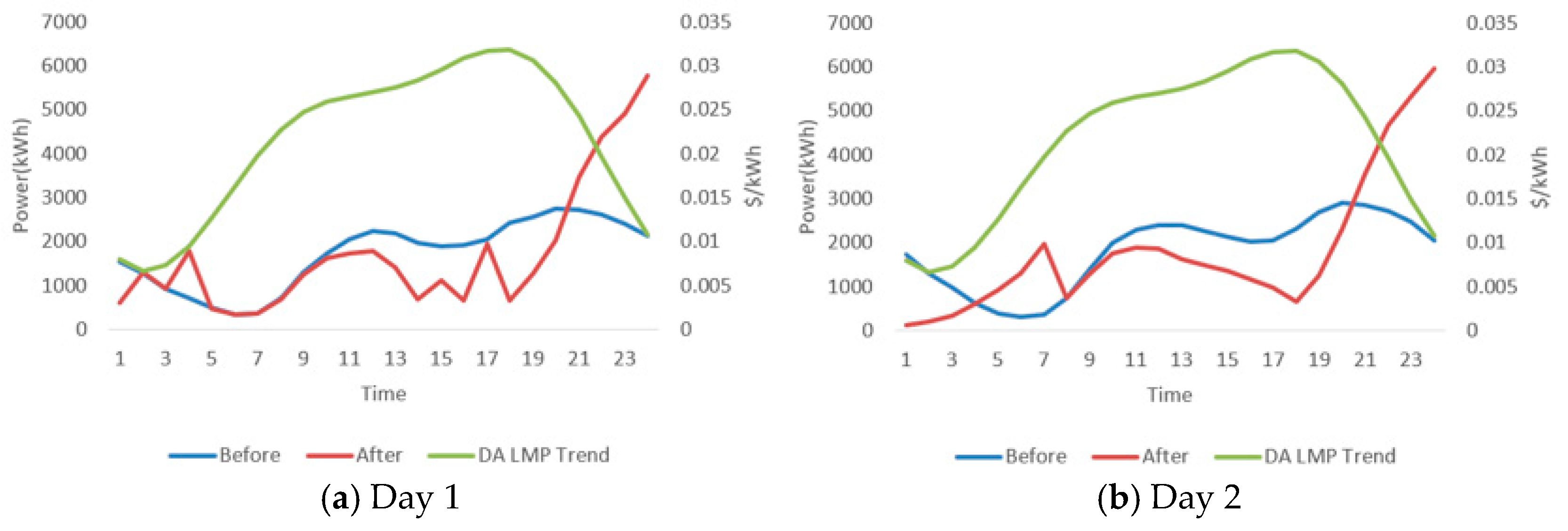

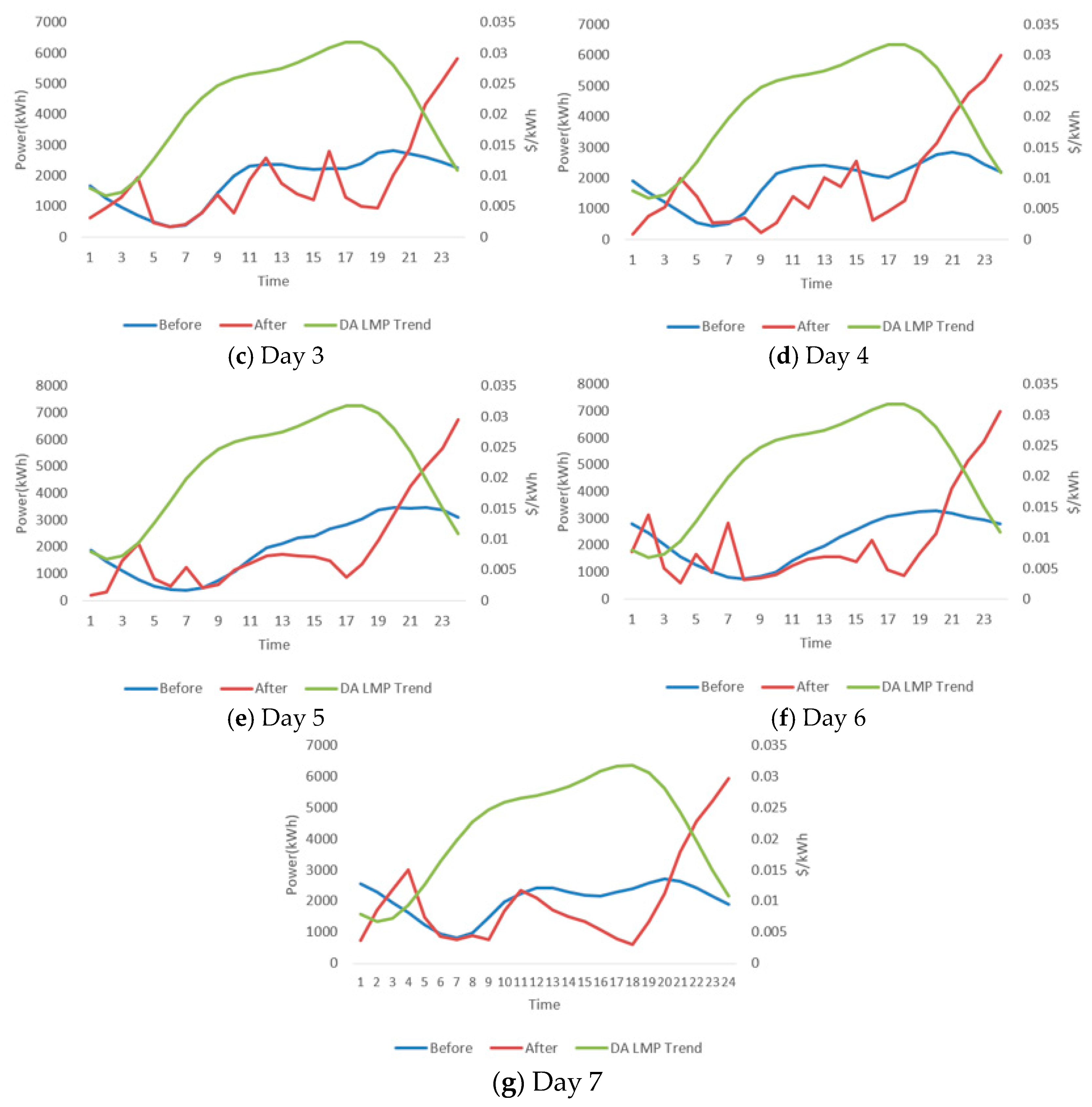

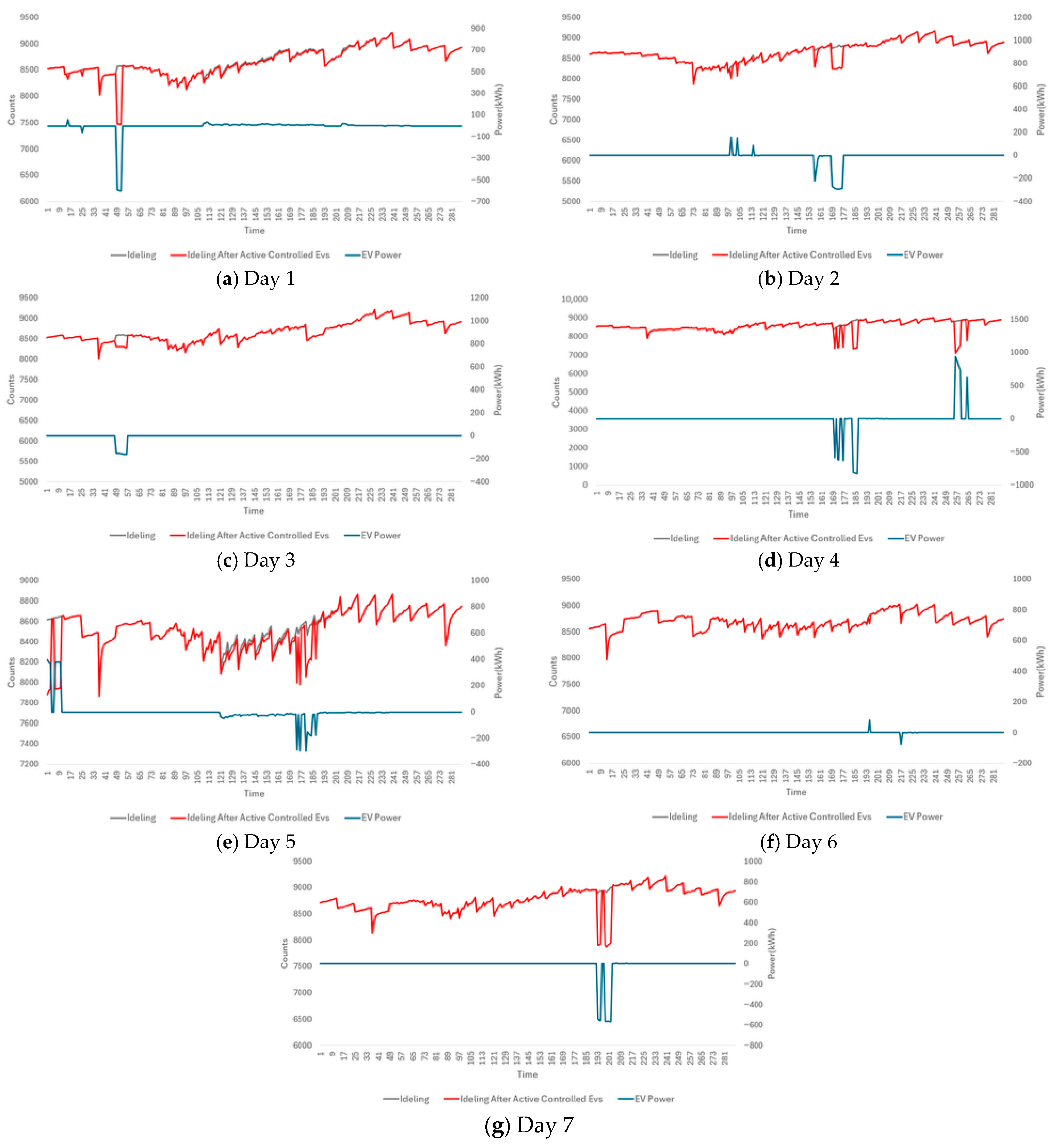

3.4. Two-Stage Scheduling Plan and Strategy of the VPP Operator

3.5. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Review of virtual power plant operations: Resource coordination and multidimensional interaction. Appl. Energy 2024, 357, 122284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ran, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M. Optimal energy scheduling of virtual power plant integrating electric vehicles and energy storage systems under uncertainty. Energy 2024, 309, 132988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, N.M.; Saha, T.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Sharma, P.; Singh, B. A comprehensive review of vehicle-to-grid integration in electric vehicles: Powering the future. Energy Rep. 2024, 10, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsma, M.K.; AlSkaif, T.A.; Fidder, H.A.; van Sark, W.G.J.H.M. Flexibility of Electric Vehicle Demand: Analysis of Measured Charging Data and Simulation for the Future. World Electr. Veh. J. 2019, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Li, X.; Tian, Z.; Yang, H. Uncertainty analysis of the electric vehicle potential for a household to enhance robustness in decision on the EV/V2H technologies. Appl. Energy 2024, 365, 123294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Xu, Y.; Gu, W.; Yang, L.; Sun, H. Multi-time-scale scheduling strategy for virtual power plants considering uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 11, 4208–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedipour-Dahraie, M.; Najafi, H.R.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; Guerrero, J.M. Risk-averse scheduling of virtual power plants in energy and reserve markets considering demand response programs. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 2964–2976. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.H.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Rastegar, M. Coordinated operation of electric vehicle charging and wind power generation as a virtual power plant. Appl. Energy 2019, 256, 113961. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, J. Multi-objective dispatching optimization of virtual power plants in vehicle-to-grid mode. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1178273. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, F.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J. Data-driven stochastic robust optimization for virtual power plant operation under renewable and market uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 4965–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Zhang, T.; Li, K.; Liu, P. Optimal allocation model of virtual power plant capacity considering electric vehicles. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6658437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, P. Electric power dispatching of virtual power plant with electric vehicles. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2275, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. The optimal energy management of virtual power plants with electric vehicles based on information gap decision theory. Processes 2025, 13, 157. [Google Scholar]

- González-Romera, E.; Amarís Duarte, J.; Romero-Cadaval, E. A genetic algorithm for residential virtual power plants: Optimal day-ahead scheduling of storage and electric vehicles. Electronics 2023, 12, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. National Household Travel Survey. 2022. Available online: http://nhts.ornl.gov (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Power Systems Economics Laboratory, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology. EV Driving and Charging Data Repository for the Converged Charging Station R&D Project. 2024. Available online: http://psel.gist.ac.kr/prog/bbsArticle/BBSMSTR_000000011963/view.do?nttId=B000000069959Np1yY3w&mno=59118 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1940 to Present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Preis, V.; Biedenbach, F. Assessing the incorporation of battery degradation in vehicle-to-grid optimization models. Energy Inf. 2023, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas EV Hub. State EV Registration Data. Available online: http://www.atlasevhub.com/market-data/state-ev-registration-data/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS); Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL); American Clean Power Association (ACP). U.S. Wind Turbine Database (USWTDB). Available online: http://eerscmap.usgs.gov/uswtdb/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

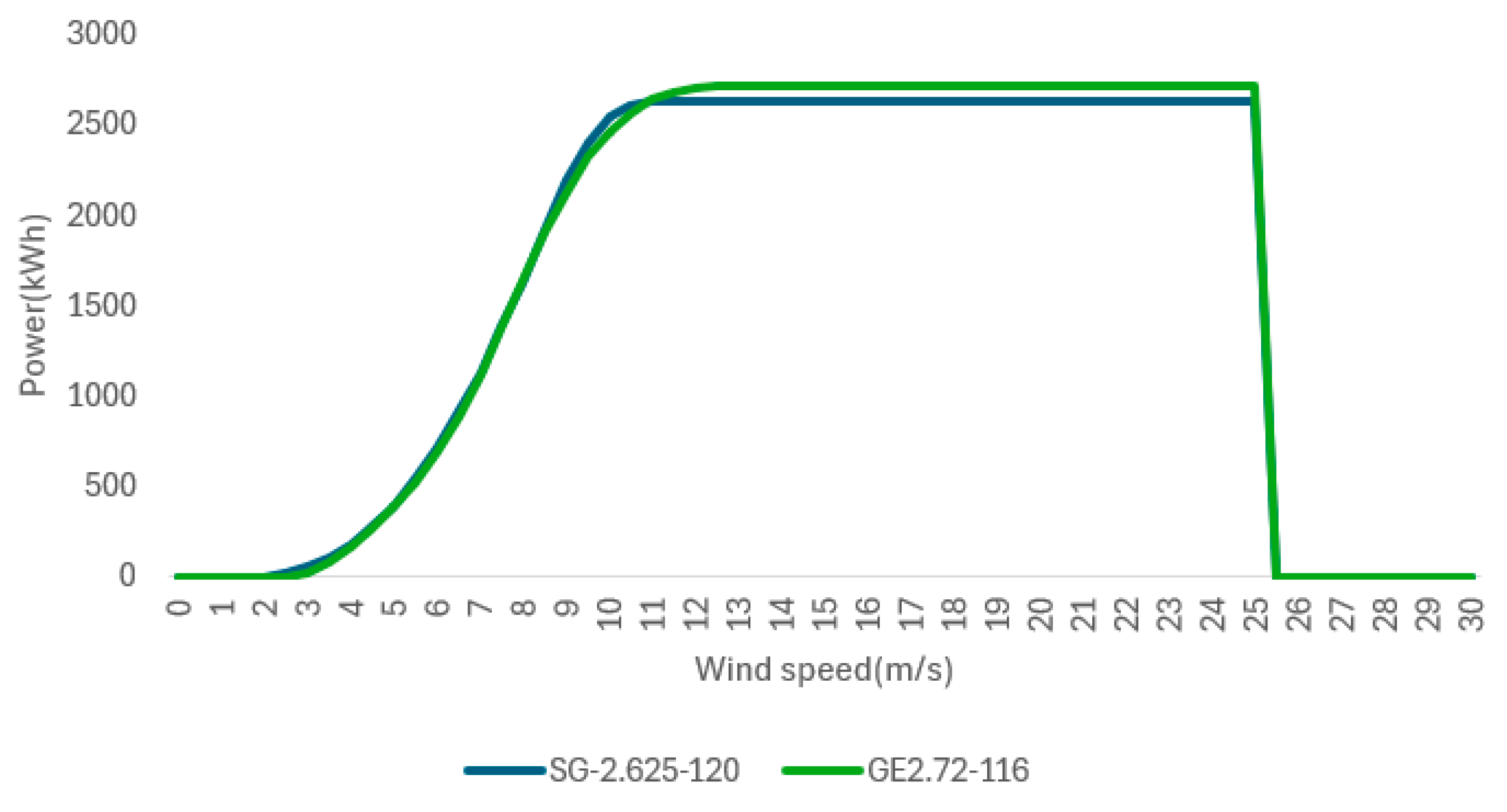

| Turbine Model | Capacity (kW) | Hub Heigh (m)t | Rotor Diameter (m) | Rotor Swept Area (m2) | Total Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG-2.625-120 | 2625 | 85 | 120 | 11,309.73 | 145.1 |

| GE2.72-116 | 2720 | 90 | 116 | 10,568.32 | 148.1 |

| Pair | MAE | RMSE | TVD (0–1) | Hellinger (0–1) | JS Distance (0–1) | Pearson r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday-Departure | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.062 | 0.107 | 0.118 | 0.995 |

| Weekday-Arrival | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.087 | 0.106 | 0.122 | 0.977 |

| Weekend-Departure | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.078 | 0.132 | 0.142 | 0.987 |

| Weekend-Arrival | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.084 | 0.096 | 0.114 | 0.978 |

| Pair | MAE | RMSE | TVD (0–1) | Hellinger (0–1) | JS Distance (0–1) | Pearson r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday-Dwell time | 29.3 | 65.4 | 0.043 | 0.029 | 0.007 | 0.997 |

| Weekend-Dwell time | 44.4 | 106.5 | 0.046 | 0.032 | 0.009 | 0.996 |

| Day | MAE (kW) | NMAE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3473.67 | 21.7 |

| 2 | 3012.62 | 18.8 |

| 3 | 4325.56 | 27.1 |

| 4 | 3689.75 | 23.1 |

| 5 | 3811.55 | 23.9 |

| 6 | 2316.14 | 14.5 |

| 7 | 4075.05 | 25.5 |

| Day | Charging Demands (kWh) | Baseline Cost ($) | Cost Saving ($) | DA Optimization Cost ($) | Cost Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41,445.9 | 1307.3 | 186.7 | 1120.6 | 14.3 |

| 2 | 43,616.8 | 1549.1 | 403.1 | 1146.0 | 26.0 |

| 3 | 44,083.1 | 1216.0 | 108.2 | 1107.8 | 8.9 |

| 4 | 45,263.2 | 881.5 | 136.7 | 744.8 | 15.5 |

| 5 | 48,067.5 | 1072.9 | 141.0 | 931.9 | 13.1 |

| 6 | 52,282.8 | 1293.9 | 160.6 | 1133.3 | 12.4 |

| 7 | 48,731.5 | 1230.6 | 185.5 | 1045.1 | 15.1 |

| Day | Baseline Net Revenue ($) | Net Revenue by Controlling EVs ($) | RT Optimization Net Revenue ($) | Battery Degradation Cost ($) | Discharging Power (kWh) | Charging Power (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 651.34 | 13.46 | 664.80 | 8.45 | 1224.20 | 2450.03 |

| 2 | −393.96 | 88.02 | −305.94 | 7.22 | 445.81 | 2694.33 |

| 3 | −414.70 | 40.22 | −374.48 | 2.89 | 11.37 | 1243.16 |

| 4 | 277.08 | 492.98 | 770.06 | 22.49 | 4077.79 | 5702.30 |

| 5 | 165.96 | 104.05 | 270.01 | 14.50 | 3074.59 | 3229.51 |

| 6 | 38.08 | 3.57 | 41.65 | 0.38 | 83.41 | 81.79 |

| 7 | 2095.95 | 56.23 | 2152.18 | 10.40 | 54.16 | 4468.34 |

| Day | Baseline Revenue ($) | DA Cost Saving ($) | RT Net Revenue ($) | Total Daily Benefit ($) | Proposed Model Revenue ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3122.44 | 186.67 | 5.01 | 191.68 | 3314.12 |

| 2 | 1747.38 | 403.04 | 80.80 | 483.84 | 2231.22 |

| 3 | 758.37 | 108.26 | 37.34 | 145.60 | 903.97 |

| 4 | 1244.79 | 136.72 | 470.49 | 607.21 | 1852.00 |

| 5 | 926.66 | 140.93 | 89.55 | 230.48 | 1157.14 |

| 6 | 1021.07 | 160.55 | 3.19 | 163.74 | 1184.81 |

| 7 | 2752.02 | 185.46 | 45.80 | 231.26 | 2983.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, H.; Kim, J. Optimal Operation Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Using Electric Vehicle Agent-Based Model Considering Operational Profitability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411291

Jeong H, Kim J. Optimal Operation Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Using Electric Vehicle Agent-Based Model Considering Operational Profitability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411291

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Hwanmin, and Jinho Kim. 2025. "Optimal Operation Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Using Electric Vehicle Agent-Based Model Considering Operational Profitability" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411291

APA StyleJeong, H., & Kim, J. (2025). Optimal Operation Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Using Electric Vehicle Agent-Based Model Considering Operational Profitability. Sustainability, 17(24), 11291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411291