Index of Sustainability of Water Supply Systems (ISA): An Autonomous Framework for Urban Water Sustainability Assessment in Data-Scarce Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Urban Water Sustainability Imperative

1.2. The Persistent Gap in Diagnostic Tools

1.3. The Benchmarking Paradox and the Need for Autonomous Assessment

1.4. Toward an Autonomous Diagnostic Approach

1.5. The ISA Framework: Origins and Core Innovation

1.6. Scope and Structure of This Study

1.7. Objectives of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

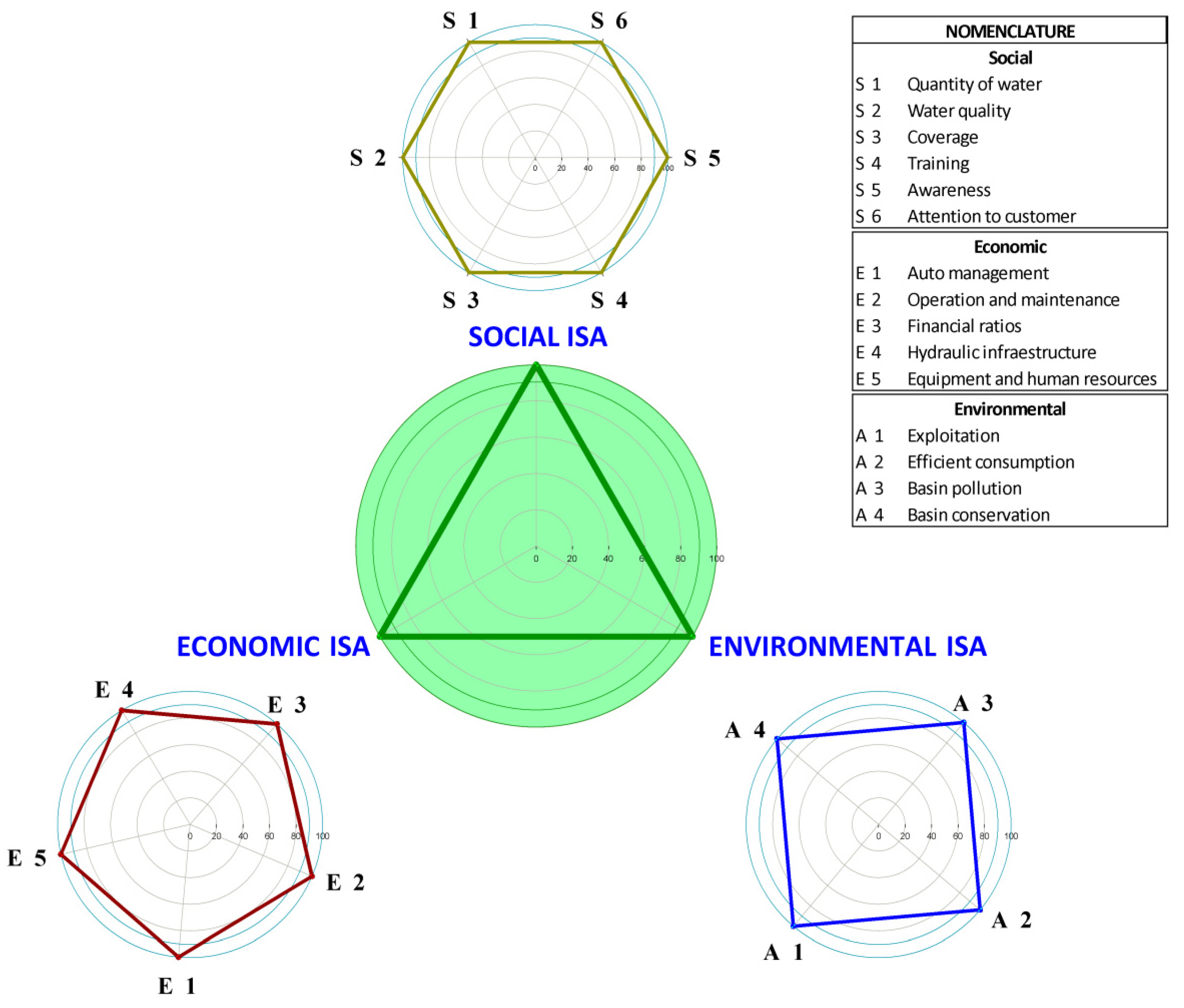

2.1. Conceptual Foundation of the ISA Framework

2.2. ISA Architecture and Indicator Structure

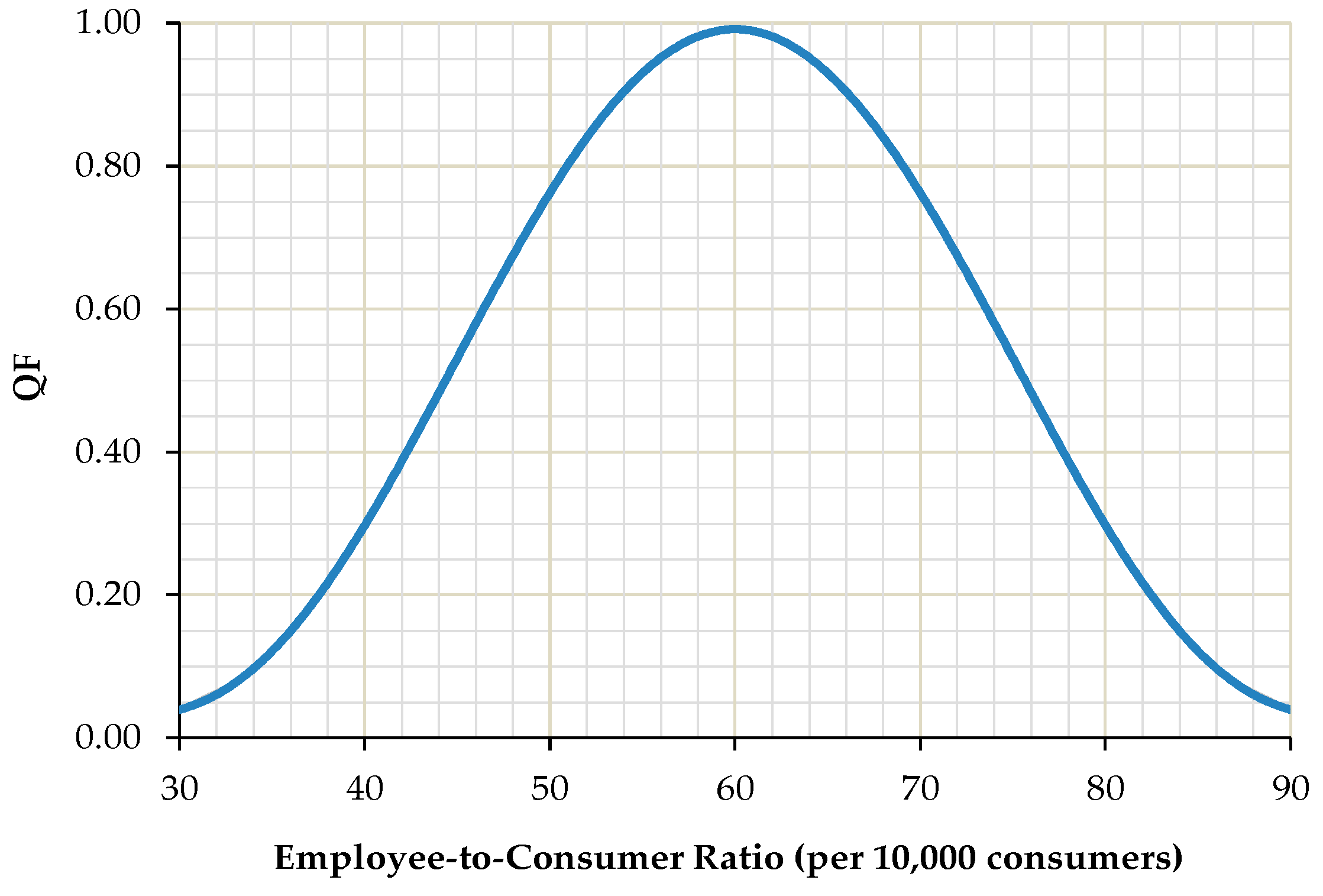

2.3. The Role and Necessity of Conversion Functions

2.4. Conversion Functions for Transforming Raw Indicators into Quality Factors (QF)

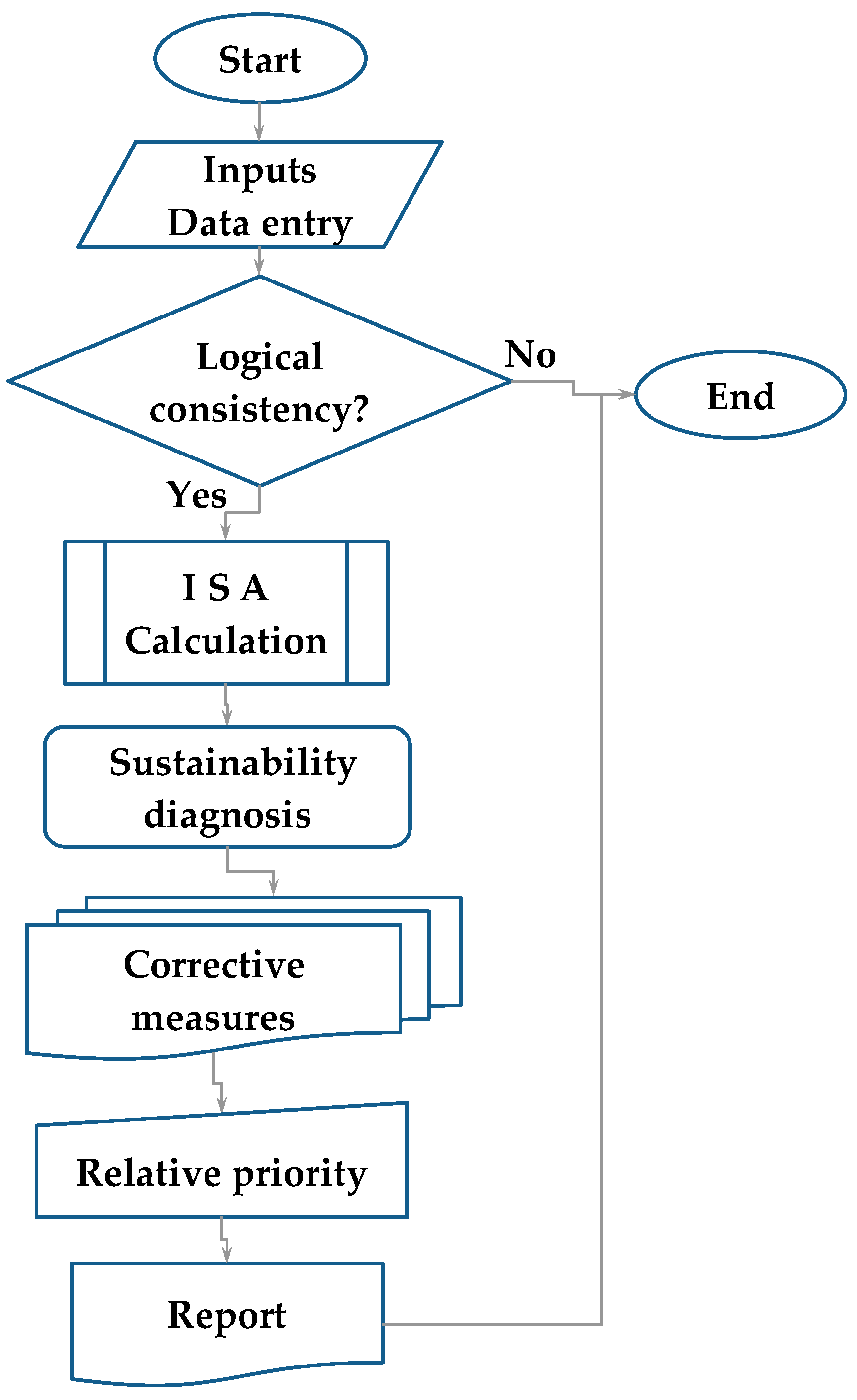

2.5. A Flexible and Cyclical Management Framework

- Assessment and Baseline Establishment: A comprehensive data-gathering phase to characterize the current state of the system.

- ISA Calculation and Diagnosis: The transformation of raw data into a holistic sustainability score and a detailed sub-component diagnosis.

- Characterization and Prioritization: The identification of critical vulnerabilities and the ranking of intervention areas based on their severity and urgency.

- Strategic Planning: The development of a concrete, evidence-based action plan to address the diagnosed deficits.

- Execution: The implementation of the prioritized interventions.

- Monitoring and Feedback: The systematic tracking of progress and the use of new data to refine the next cycle of assessment.

2.6. Classification and Interpretation of ISA Scores

2.7. Model Validation and Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Economic Sustainability: Structural Financial and Physical Deficits

3.1.1. Physical Water Losses

3.1.2. Insufficient Cost Recovery

3.1.3. Negligible Infrastructure Renewal

3.2. Social Sustainability: Intermittent and Functionally Unreliable Service

3.2.1. Intermittent Supply

3.2.2. Water Quality Failures at the Point of Use

3.2.3. Coverage vs. Delivered Service Quality

3.3. Environmental Sustainability: Systemic Failure in Stewardship

3.3.1. Absence of Wastewater Treatment

3.3.2. Weak or Non-Existent Source Protection

3.4. Holistic Diagnosis and Visualization

3.5. Synthesis of Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Work

6.1. Limitations

- (1)

- Geographic and Institutional Scope

- (2)

- Data Availability and Quality

- (3)

- Static Assessment

- (4)

- Subjectivity in Expert-Based Calibration

- (5)

- Limited Representation of Governance and Regulatory Dimensions

- (6)

- Lack of Integration with Hydro-Climatic Variability

6.2. Future Work

- (1)

- Expansion of ISA Applications Across Diverse Regions

- (2)

- Dynamic and Predictive Modeling

- (3)

- Refinement of Conversion Functions

- (4)

- Integration with Climate Resilience and Water Security Metrics

- (5)

- Strengthening Governance and Institutional Indicators

- (6)

- Development of a Decision-Support Platform

- (7)

- Linking ISA Outputs to Investment and Policy Planning

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Operational Application of the Sustainability Diagnosis

Appendix A.2. Summary of the ISA Aggregation Procedure

Appendix A.3. Systemic Considerations in ISA Application

Appendix A.3.1. Valuation Phase

Appendix A.3.2. Diagnosis Phase

Appendix A.3.3. Characterization Phase

Appendix A.4. Example of Indicator Conversion and Interpretation

Appendix A.5. Illustrative Diagnosis and Component Valuation

Appendix A.6. Corrective Action Framework

Appendix A.7. Prioritization Method

Appendix A.8. Key Insights and Broader Inferences

Appendix A.9. Recommendations for Future Development

References

- Maumela, K.G.; Mathaba, T.N.D.; Kao, M. An Integrated Framework for Urban Water Infrastructure Planning and Management: A Case Study for Gauteng Province, South Africa. Water 2025, 17, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebu, S.; Lee, A.; Salzberg, A.; Bauza, V. Adaptive strategies to enhance water security and resilience in low- and middle-income countries: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 925, 171520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beker, B.; Kansal, M. Complexities of the urban drinking water systems in Ethiopia and possible interventions for sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 4629–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Imminent Risk of a Global Water Crisis, Warns the UN World Water Development Report 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/reports/wwdr/2023/en/water-supply-and-sanitation (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Adom, R.; Simatele, M. Overcoming systemic and institutional challenges in policy implementation in South Africa’s water sector. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, K.; Zghibi, A.; Elomri, A.; Mazzoni, A.; Triki, C.A. Literature Review on System Dynamics Modeling for Sustainable Management of Water Supply and Demand. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBNET Benchmarking Database. World Bank Water Data. The World Bank Group. 2025. Available online: https://newibnet.org/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Sakai, H. Review of research on performance indicators for water utilities. AQUA—Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2024, 73, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, J.D. The Politics of Performance Benchmarking in Urban Water Supply: Sacrificing Equity on the Altar of Efficiency. Water Altern. 2024, 17, 415–436. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, Z.; Murtaza, N.; Pasha, G.A.; Iqbal, S.; Ghumman, A.R.; Abbas, F.M. Predicting scour depth in a meandering channel with spur dike: A comparative analysis of machine learning techniques. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 045158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Aslam, M.; Jasińska, E.; Javed, M.; Goňo, M. Guidelines for the Technical Sustainability Evaluation of the Urban Drinking Water Systems Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process. Resources 2023, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, R.; Loc, H.; Babel, M.; Chapagain, K. Assessment and enhancement of community water supply system sustainability: A dual Framework Approach. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 24512:2007; Activities Relating to Drinking Water and Wastewater Services—Guidelines for the Management of Drinking Water Utilities and for the Assessment of Drinking Water Services. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Benavides-Muñoz, H.M. Diagnóstico de la Sostenibilidad de un Abastecimiento de Agua e Identificación de las Propuestas que la Mejoren. Doctoral Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, C.; Danilenko, A. The IBNET Water Supply and Sanitation Performance Blue Book: The International Benchmarking Network for Water and Sanitation Utilities Databook; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780821385883. [Google Scholar]

- Orime, H.; Tait, S.; Boxall, J.; Shepherd, W.; Schellart, A. Evaluating the performance of water distribution network deterioration using customer-oriented performance indices. Water Supply 2024, 24, 3759–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namavar, M.; Moghaddam, M.; Shafiei, M. Developing an indicator-based assessment framework for assessing the sustainability of urban water management. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, I.; Oviedo-Ocaña, E.; Hurtado, K.; Barón, A.; Hall, R. Assessing Sustainability in Rural Water Supply Systems in Developing Countries Using a Novel Tool Based on Multi-Criteria Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaeed, B.S.; Dexter, V.L.H.; Soroosh, S. A sustainable water resources management assessment framework (SWRM-AF) for arid and semi-arid regions—Part 1: Developing the conceptual framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-F.; Peng, L.-P. Extracting Evaluation Factors of Social Resilience in Water Resource Protection Areas Using the Fuzzy Delphi Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; Sinha, R. Identification of Indicators for Developing an Integrated Study on Urban Water Supply System, Planning, and Management. J. Environ. Eng. 2023, 149, 04022095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palhares, J.C.P.; Matarim, D.L.; de Sousa, R.V.; Martello, L.S. Water Performance Indicators and Benchmarks for Dairy Production Systems. Water 2024, 16, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 2002; Reproduction of the Original 1975 Book; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237035943_The_Delphi_Method_Techniques_and_Applications#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 17 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Noori, A.; Bonakdari, H.; Morovati, K.; Gharabaghi, B. Development of an optimal water supply plan using integrated fuzzy Delphi and fuzzy ELECTRE III methods: Case study of the Gamasiab basin. Expert Syst. 2020, 37, e12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E., Jr.; Estruch-Juan, E.; Gómez, E.; Del Teso, R. Comprehensive regulation of water services. Why quality of service and economic costs cannot be considered separately. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 3247–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudi, M.; Gai, Q.; Yuan, H.; Guiqing, L.; Basirialmahjough, M.; Motamedi, A.; Galoie, M. A novel objective for improving the sustainability of water supply system regarding hydrological response. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, D.; Regan, H.; Andelman, S. Assessing the sustainability of freshwater systems: A critical review of composite indicators. Ambio 2016, 45, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarzebski, M.P.; Karthe, D.; Chapagain, S.K.; Setiawati, M.D.; Wadumestrige Dona, C.G.; Pu, J.; Fukushi, K. Comparative Analysis of Water Sustainability Indices: A Systematic Review. Water 2024, 16, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellbauer, M.; Jepson, W.; Lefore, N.; Thomson, P. Advancing multiple-use water services for development in low- and middle-income countries. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2025, 12, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim, D.L.; Fernandes, L.L. Application of the Rural Water Sustainability Index (RWSI) in Amazon rural communities, Pará, Brazil. Water Policy 2022, 24, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Espinosa, J.C.; Benavides-Muñoz, H.M. Adjustment value of water leakage index in infrastructure. Dyna 2019, 86, 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi-Dehkordi, M.; Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Chu, X. Development of a Combined Index to Evaluate Sustainability of Water Resources Systems. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 2965–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, B.; Tabesh, M. Urban Storm Water Drainage System Optimization using a Sustainability index and LID/BMPs. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 76, 103500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikakou, M.; Stanford, B.; Wiedmann, T.; Rowley, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ishii, S.; Gaitan, J.; Johns, G.; Lundie, S.; Khan, S. A flexible framework for assessing the sustainability of alternative water supply options. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliç, S.; Firat, M.; Yilmaz, S.; Ateş, A. A novel assessment framework for evaluation of the current implementation level of water and wastewater management practices. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2023, 23, 1787–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, E.Z.; Skarbek, M.; Kanta, L. A sociotechnical framework to characterize tipping points in water supply systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, E.; McPhearson, T.; Levin, S.A. Integrated assessment of urban water supply security and resilience: Towards a streamlined approach. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 075006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shao, Z.; Wang, W. Resilience Assessment and Critical Point Identification for Urban Water Supply Systems under Uncertain Scenarios. Water 2021, 13, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Inverno, G.; Carosi, L.; Romano, G. Environmental sustainability and service quality beyond economic and financial indicators: A performance evaluation of Italian water utilities. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 75, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.L.; Styles, D.; Gallagher, J.; Williams, A.P. Aligning efficiency benchmarking with sustainable outcomes in the United Kingdom water sector. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navia, M.R.; González Aguilera, J.C.; Cruz Bohórquez, J.M. Avances y Retos del Sector de Agua Potable y Saneamiento en Colombia: Una Mirada Desde el Sistema AquaRating; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmer, J.; Chojnacki, E. Forecast of environment systems using expert judgements: Performance comparison between the possibilistic and the classical model. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2021, 41, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carril Ferreira, J.; Costa dos Santos, D.; Campos, L.C. Blue-green infrastructure in view of Integrated Urban Water Management: A novel assessment of an effectiveness index. Water Res. 2024, 257, 121658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granda-Aguilar, F.; Benavides-Muñoz, H.; Arteaga-Marín, J.; Massa-Sánchez, P.; Ochoa-Cueva, P. Sustainable Water Service Tariff Model for Integrated Watershed Management: A Case Study in the Ecuadorian Andes. Water 2024, 16, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, S.; Martínez-Moscoso, A.; Quiroga, D.; Ochoa-Herrera, V. Challenges to Water Management in Ecuador: Legal Authorization, Quality Parameters, and Socio-Political Responses. Water 2021, 13, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossio, C.; Norrman, J.; McConville, J.; Mercado, Á.; Rauch, S. Indicators for sustainability assessment of small-scale wastewater treatment plants in low and lower-middle income countries. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2020, 6, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. Wastewater Treatment and Reuse for Sustainable Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Germain, E.; Murphy, R.; Saroj, D. Designing a Sustainability Assessment Framework for Selecting Sustainable Wastewater Treatment Technologies in Corporate Asset Decisions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.R. Indicadores para Avaliação de Comissões Gestoras de Sistemas Hídricos e sua Aplicação na Análise das Bacias da Região Metropolitana de Fortaleza. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal Do Ceará, Ceará, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, O.; Akhmouch, A. Water Governance in Cities: Current Trends and Future Challenges. Water 2019, 11, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goksu, A.; Bakalian, A.; Kingdom, B.; Saltiel, G.; Mumssen, Y.; Soppe, G.; Kolker, J.; Delmon, V. Reform and Finance for the Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Sector; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.sidalc.net/search/Record/dig-okr-1098632244/Description (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Esmail, B.; Suleiman, L. Analyzing Evidence of Sustainable Urban Water Management Systems: A Review through the Lenses of Sociotechnical Transitions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adank, M.; Godfrey, S.; Butterworth, J.; Defere, E. Small town water services sustainability checks: Development and application in Ethiopia. Water Policy 2018, 20, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossio, C.; McConville, J.; Mattsson, A.; Mercado, Á.; Norrman, J. EVAS—A practical tool to assess the sustainability of small wastewater treatment systems in low and lower-middle-income countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 140938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arana, E. Resolución de Acuerdo Tarifario Número 12. Consejo de Dirección del Instituto Nicaragüense de Acueductos y Alcantarillados (INAA). 2002. CD-RE-015-02: 7. Available online: http://www.inaa.gob.ni/normativas/CD-RE-015-02.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2010).

- Cáceres, V. Pago de Pasivo Laboral del SANAA Impide Municipalización del Agua en el Distrito Central; Unidad de Investigación de HRN: Tegucigalpa, Honduras, 2008; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

| Social [33.3] | Economic [33.4] | Environmental [33.3] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcomponent | Indicator | Subcomponent | Indicator | Subcomponent | Indicator |

| [6.0] Operational: Quantity | [2.0] Flow reductions | [11.0] Self-management | [5.0] Cost recovery | [7.0] Extraction & Use | [4.0] Extracted water flow |

| [2.0] Interruption duration | [2.0] Financial self-sufficiency | [3.0] Watershed legal regulation | |||

| [2.0] Service pressure | [1.0] Collection efficiency | [5.3] Efficient consumption | [2.0] Per capita consumption | ||

| [6.3] Operational: Quality | [2.0] Number of quality analyses | [3.0] Non-revenue water | [1.3] Hydric resource underuse | ||

| [2.0] Water stagnation | [9.2] Operation & Maintenance | [4.0] Infrastructure leakage index | [2.0] Energy consumption | ||

| [2.3] Residual chlorine | [1.2] Pipe breaks | [8.0] Operational pollution | [3.0] Drinking water sludge | ||

| [6.0] Operational: Coverage | [3.0] Properties connected | [1.0] Acoustic leak control | [3.0] Wastewater treatment | ||

| [3.0] Peak-hour coverage | [1.0] GIS information availability | [2.0] Impact mitigation | |||

| [5.0] Training: Capacity-building | [2.5] Field technicians and planners | [1.0] Reservoir maintenance | [13.0] Source conservation | [2.5] Source watershed belonging | |

| [2.5] Managers and coordinators | [1.0] Illegal connection search | [4.0] Reforestation underway | |||

| [4.0] Training: Awareness | [2.0] Customer training courses | [3.0] Financial indices | [1.5] Liquidity ratio | [2.5] Clean industries in watershed | |

| [2.0] TV and radio campaigns | [1.5] Debt stock | [4.0] Capital for conservation | |||

| [6.0] Customer service | [1.5] Complaint handling | [8.2] Supply infrastructure | [1.0] Hydrometric parcels | ||

| [1.5] Connections and repairs | [1.0] Number of hydrants | ||||

| [1.5] Outreach and marketing | [1.2] Collar replacement | ||||

| [1.5] Customer service infrastructure | [1.0] Working meters | ||||

| [1.0] Meter age | |||||

| [1.0] Accumulated meter volume | |||||

| [2.0] Renewed pipelines | |||||

| [2.0] Equipment & staff | [1.0] Machinery and equipment access | ||||

| [1.0] Staff performance | |||||

| Function Type | Quality Factor (QF) Equation | Number Equation | Modeled Behavioral Principle | Typical Indicators of Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sigmoidal | Equation (4) | Critical Threshold and Optimal Range: Captures behavior where benefits accelerate around a central value (threshold) and saturate at the extremes, penalizing both deficiency and excess. | Service Continuity, Service Pressure, Residual Chlorine, Treatment Efficiency. | |

| Logarithmic | Equation (5) | Diminishing Returns (for indicators where lower is better): Imposes strong penalties for initial poor performance, but the benefits decrease as the indicator improves. Ideal for modeling loss reduction. | Non-Revenue Water (NRW), Energy Consumption, Operating Cost Ratios. | |

| Exponential | Equation (6) | Increasing Returns (for indicators where higher is better): Models how high levels of performance produce disproportionately large sustainability benefits, incentivizing excellence. | Service Coverage, Micrometering Index, Billing Effectiveness. | |

| Polynomial | Equation (7) | Complex Curvature: Used when the relationship between the indicator and sustainability is complex and cannot be accurately represented by simpler functions. Offers maximum flexibility. | Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) [29], Rehabilitation Rates, Technical Productivity. | |

| Hyperbolic | Equation (8) | Impact Saturation:Reflects that initial improvements in an indicator have a large impact, but this impact diminishes drastically as performance levels increase. Common for institutional indicators. | Training Coverage, Community Participation, Administrative Efficiency. | |

| Piecewise Linear (Binary Threshold) | Equation (9) | Strict Compliance (Pass/Fail):Applies a total penalty (QF = 0) if a minimum legal or public health threshold is not met, and a full reward (QF = 1) if it is, reflecting a binary nature. | Drinking Water Quality Compliance, Wastewater Treatment, Watershed Protection. |

| ISA Phases | Constituent Actions |

|---|---|

| 1. Assessment | System Baseline |

| Information Gathering and Storage | |

| Analysis and Processing | |

| Stakeholder Consultation and Validation | |

| ISA Calculation | |

| 2. Diagnosis and Characterization | Indicator Aggregation |

| Analysis of Results | |

| Identification of System Pathologies Critical Deficiencies | |

| Disaggregation of Results | |

| Traceability | |

| 3. Action Plan | Analysis and Selection of Guidelines |

| Prioritization of Interventions/Actions | |

| Development of Action Plans | |

| Scheduling of Implementation | |

| 4. Implementation | Implementation of Plans |

| Project Management | |

| Execution Control | |

| Results Monitoring | |

| 5. Control, Monitoring of Results | Measurement of Achievements |

| Comparison with Baseline | |

| Analysis of Deviations | |

| Recommendations and Adjustments | |

| 6. Assessment | New Baseline |

| New Indicators | |

| Adjustments to the Method |

| Classification | ISA Threshold | Number of Systems | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 0–40 | 10 | 71 |

| Deficient | 41–60 | 4 | 29 |

| Regular | 61–75 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 76–90 | 0 | 0 |

| Excellent | 91–100 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benavides-Muñoz, H.M. Index of Sustainability of Water Supply Systems (ISA): An Autonomous Framework for Urban Water Sustainability Assessment in Data-Scarce Settings. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411293

Benavides-Muñoz HM. Index of Sustainability of Water Supply Systems (ISA): An Autonomous Framework for Urban Water Sustainability Assessment in Data-Scarce Settings. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411293

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenavides-Muñoz, Holger Manuel. 2025. "Index of Sustainability of Water Supply Systems (ISA): An Autonomous Framework for Urban Water Sustainability Assessment in Data-Scarce Settings" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411293

APA StyleBenavides-Muñoz, H. M. (2025). Index of Sustainability of Water Supply Systems (ISA): An Autonomous Framework for Urban Water Sustainability Assessment in Data-Scarce Settings. Sustainability, 17(24), 11293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411293