An Explainable Machine Learning Method for Neighborhood-Level Traffic Emissions Prediction: Insights from Ningbo, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Developing an interpretable machine learning model to investigate the nonlinear effect of influencing factors;

- Considering the spatially varying effects of the built environment on carbon emissions;

- Incorporating field-measured CO2 concentrations to validate the model results.

2. Case Study

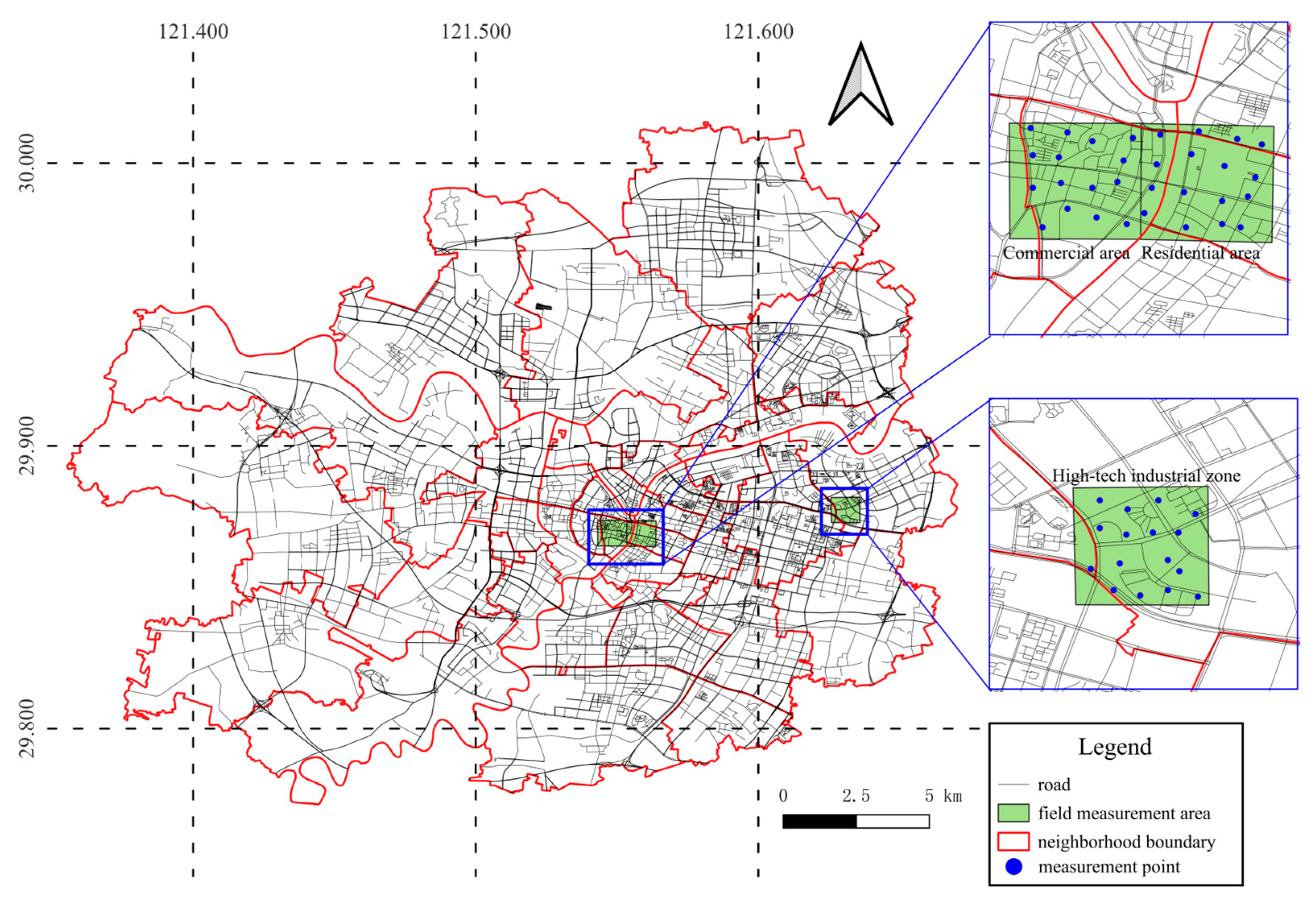

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Data

2.2.1. Built Environment

2.2.2. Carbon Emission

3. Methods

3.1. XGBoost Model

3.2. SHAP Model

3.3. GAM

4. Results

4.1. XGBoost-Based CO2 Emission Forecasting

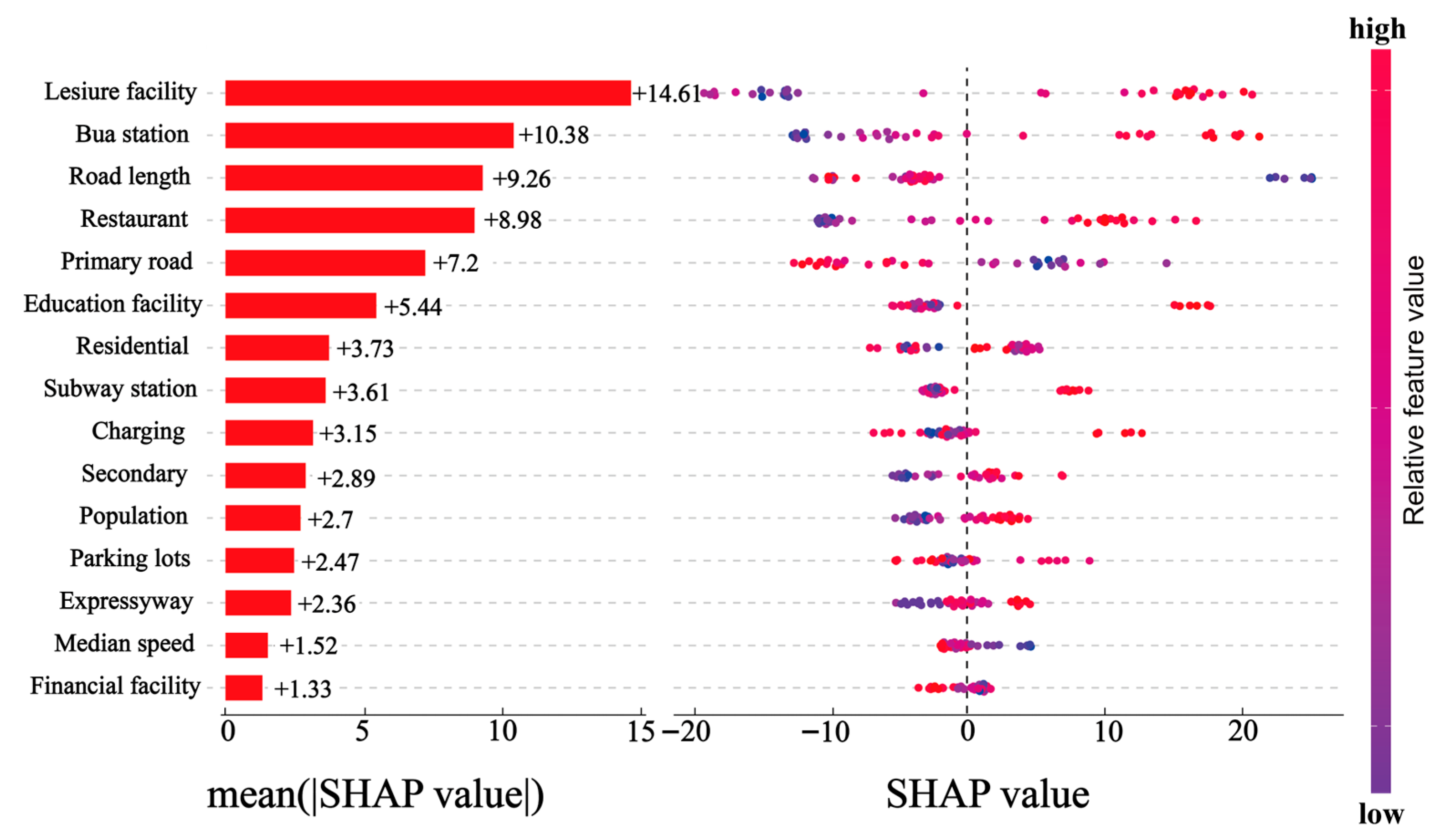

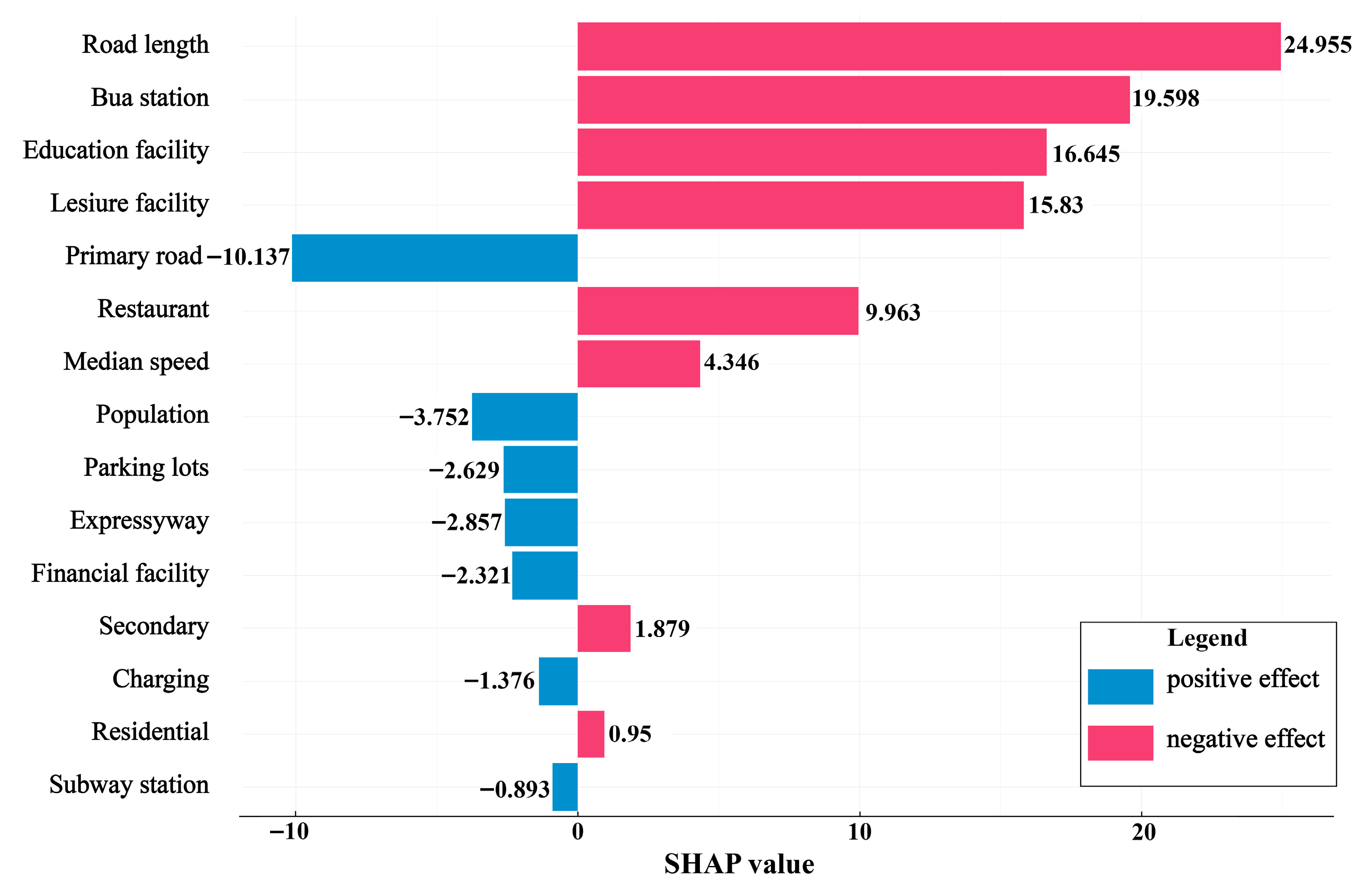

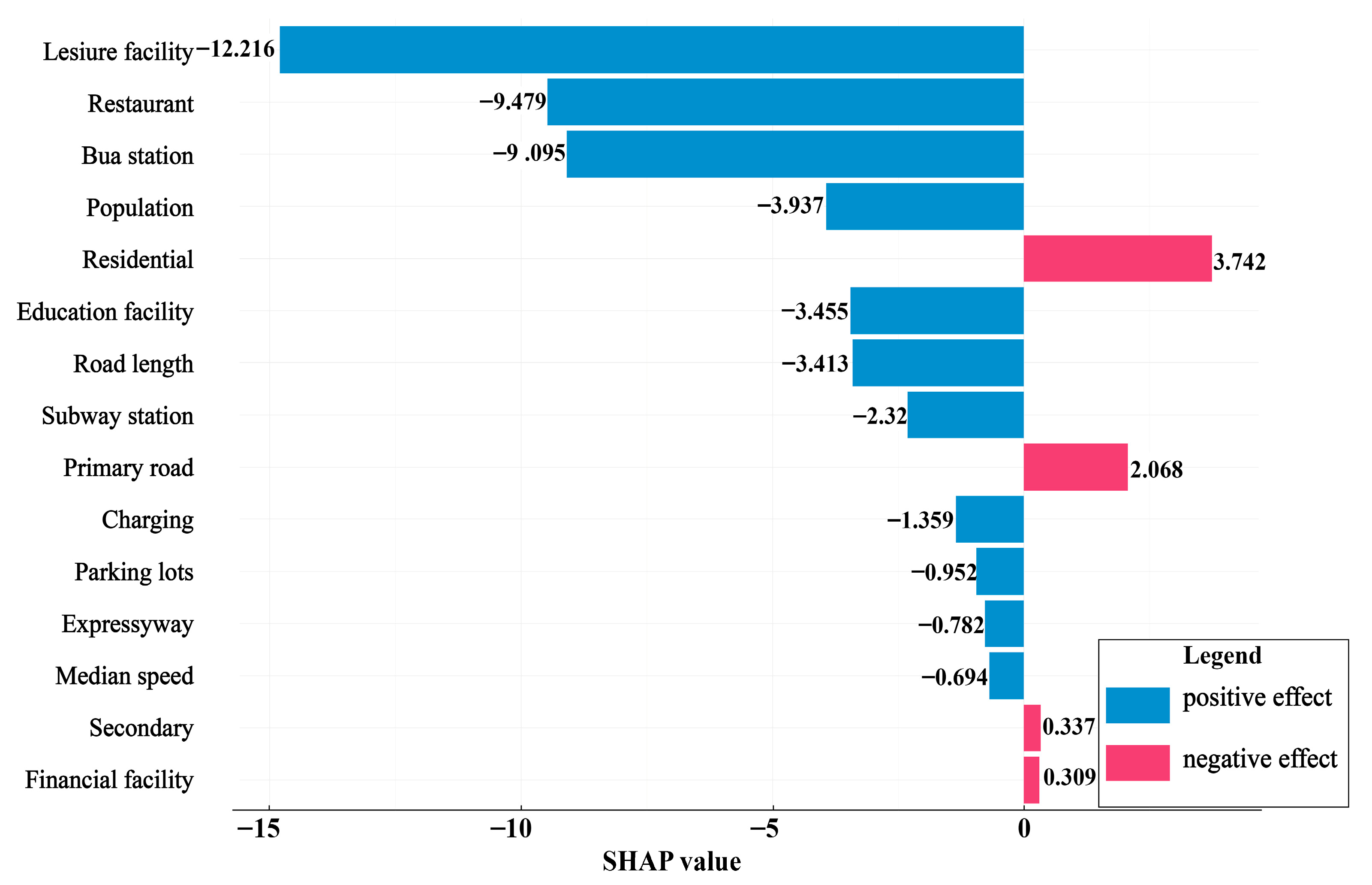

4.2. Analysis of Global Importance

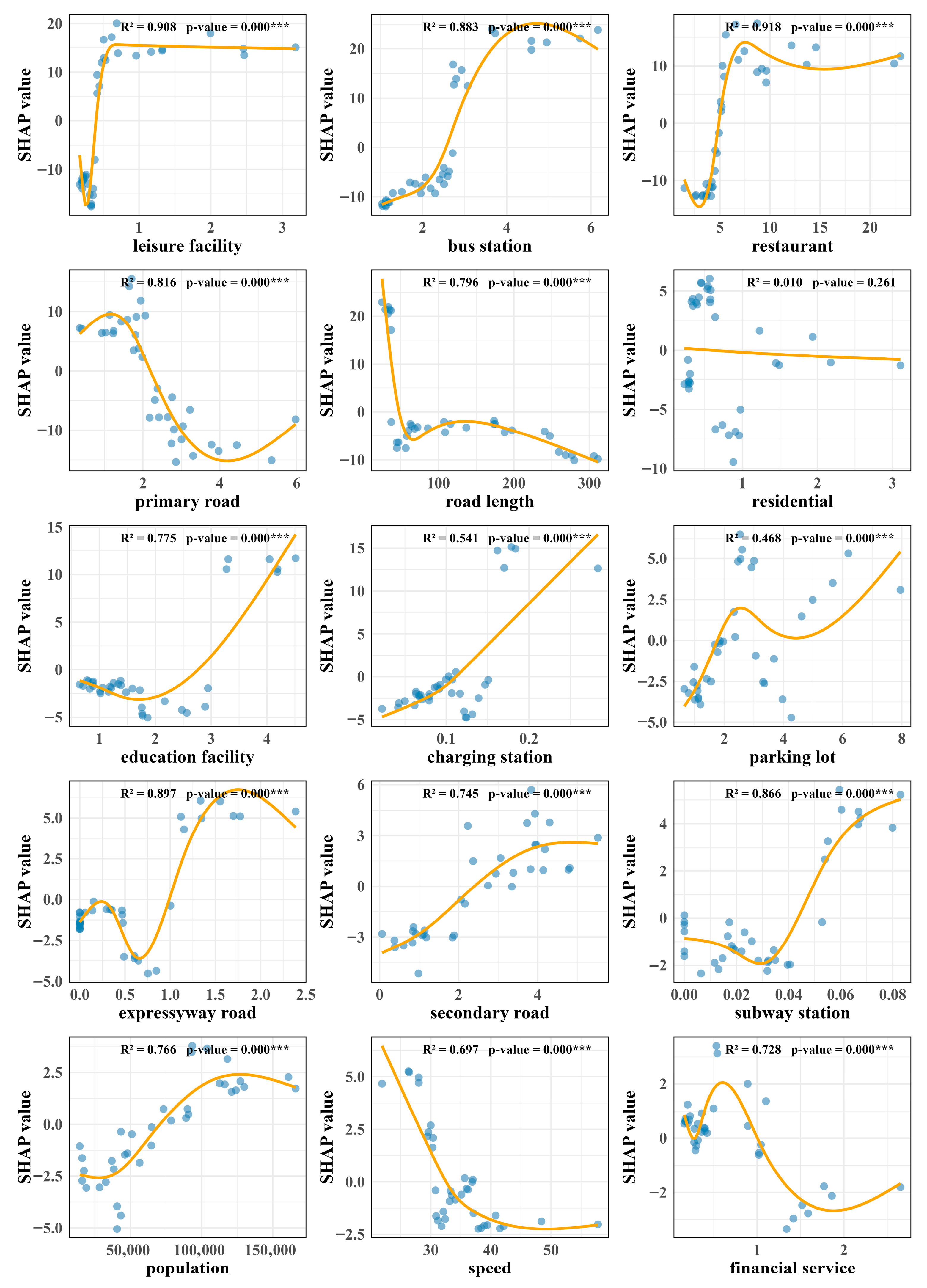

4.3. Nonlinear Relationships with Built Environment Variables

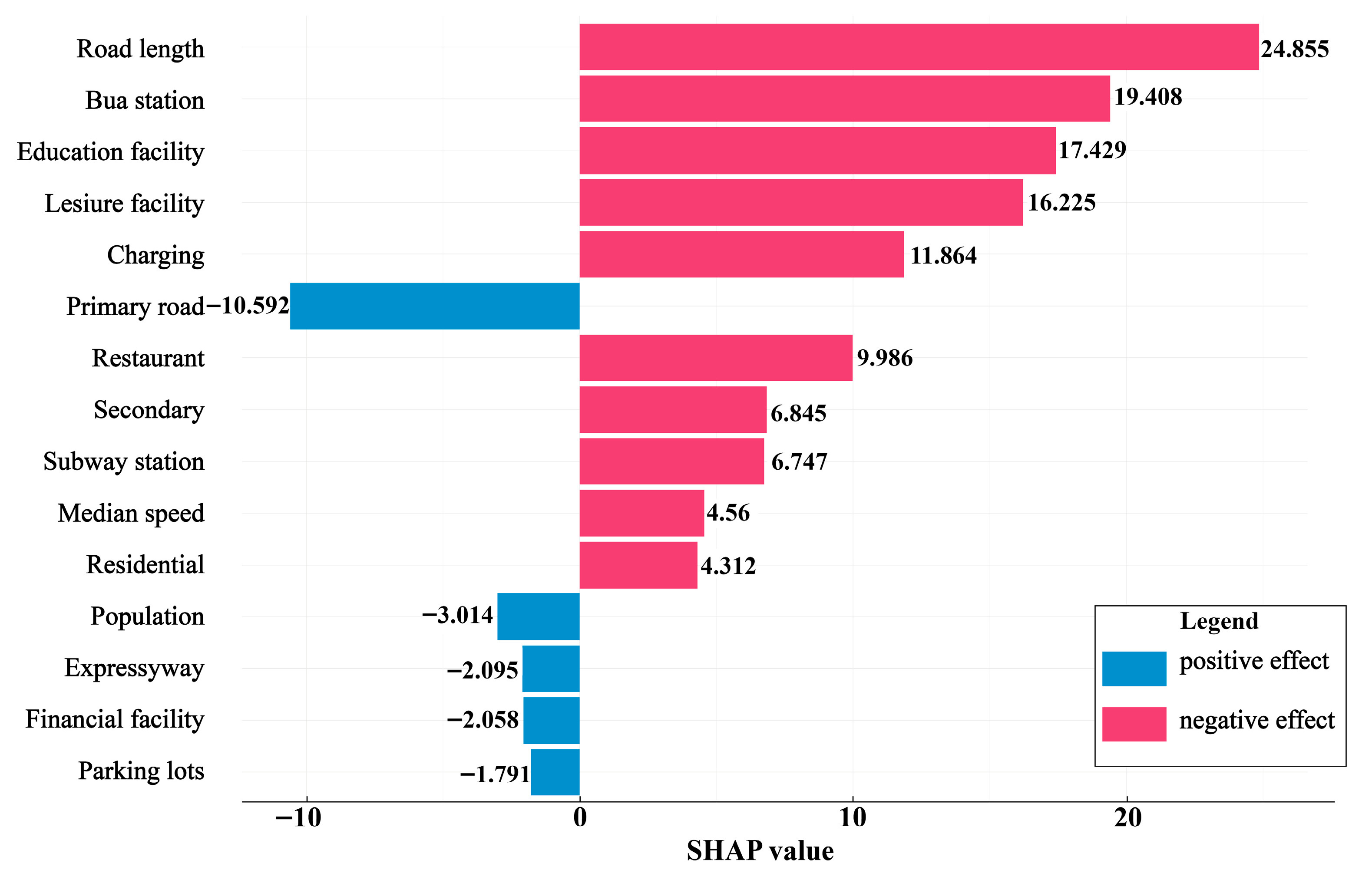

4.4. Analysis of Influencing Factors in Specific Urban Functional Areas

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOVES | Motor Vehicle Emissions Simulator |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| GAM | Generalized Additive Model |

| TOD | Transit-Oriented Development |

| LightGBM–LIME | Light Gradient Boosting Machine–Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| CatBoost–ALE | Categorical Boosting–Accumulated Local Effects |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

References

- Emissions Gap Report 2024. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Li, F.; Cai, B.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, P.; Chen, J. Changing patterns and determinants of transportation carbon emissions in Chinese cities. Energy 2019, 174, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhou, F.; Zhuang, G. Megacity pathways in China under the dual carbon goal: The case of Shanghai. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 22, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ai, S.; Li, F.; Xue, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, T. Impacts of different vehicle emissions on ozone levels in Beijing: Insights into source contributions and formation processes. Environ. Int. 2024, 191, 109002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macioszek, E.; Jurdana, I. Bicycle Traffic in the Cities. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2022, 117, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, B.; Li, A.R. Shared bicycle study to help reduce carbon emissions in Beijing. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Long, R.; Li, W.; Wei, J. Potential for reducing carbon emissions from urban traffic based on the carbon emission satisfaction: Case study in Shanghai. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 85, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.; Luo, J.; Hu, F. Prediction of the effect of bike-sharing on urban carbon emission reduction: Evidence from Beijing. J. Urban Manag. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpounakis, E.; Montesinos-Ferrer, M.; Gonzales, E.J.; Geroliminis, N. Empirical investigation of the emission-macroscopic fundamental diagram. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 101, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, H.A.; Farag, M.; Foroutan, H. Electric versus gasoline vehicle particulate matter and greenhouse gas emissions: Large-scale analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 104, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wu, P.; Chen, B. Estimation of traffic emissions in a polycentric urban city based on a macroscopic approach. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2022, 602, 127391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Li, K.; Sun, Q.; Duan, Z. Urban transport emission prediction analysis through machine learning and deep learning techniques. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 135, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, F.; Hou, Y.; Antonio Biancardo, S.; Ma, X. Unveiling built environment impacts on traffic CO2 emissions using Geo-CNN weighted regression. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 132, 104266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, G.; Yan, X.; Xia, P.; Chen, Z.; Wu, D. A differential evolution optimized hybrid XGBoost for accurate carbon emission prediction. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 193, 106627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, K.; Lee, E.H. Impact of road transport system on groundwater quality inferred from explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H. Understanding Gender Gap in Bike-Sharing Services via eXplainable Artificial Intelligence. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2025, 2679, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jin, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, W.; Sun, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S. Spatial prediction of PM2.5 concentration using hyper-parameter optimization XGBoost model in China. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y. A spatiotemporal XGBoost model for PM2.5 concentration prediction and its application in Shanghai. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfasanah, Z.; Niam, M.Z.H.; Wardiani, S.; Ahsan, M.; Lee, M.H. Monitoring air quality index with EWMA and individual charts using XGBoost and SVR residuals. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Xiao, K.; Xiang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Shi, G.; Zheng, X.; Tao, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Prediction of on-road CO2 emissions with high spatio-temporal resolution implementing multilayer perceptron. Atmos. Environ. X 2025, 27, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Choi, M.-Y.; Kim, B.; Choi, M.; Kang, S.; Park, H.; Park, M.; Kim, J.; Woo, J.-H. Integrating IAM-based CO2 projections and traffic demand forecasting for regional CO2 emission mapping in the transport sector. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Zhao, P.; Gong, Z. A review of transport carbon emissions: Insights from artificial intelligence and big data. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 532, 146906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, H.; Rastgoo, A. Predicting the carbon dioxide emission caused by road transport using a Random Forest (RF) model combined by Meta-Heuristic Algorithms. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 93, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Qiao, Z.; Wu, L.; Ren, X.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Forecasting carbon dioxide emissions using adjacent accumulation multivariable grey model. Gondwana Res. 2024, 134, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z. Carbon dioxide emission driving factors analysis and policy implications of Chinese cities: Combining geographically weighted regression with two-step cluster. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 684, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jia, P.; Feng, T.; Li, H.; Kuang, H.; Zhang, J. Uncovering the spatiotemporal impacts of built environment on traffic carbon emissions using multi-source big data. Land Use Policy 2023, 129, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ji, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Easa, S. Evaluating spatial effect of transportation planning factors on taxi CO2 emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 959, 178142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Y.; Song, W.; Song, D.; Yang, Y. Quantifying the heterogeneous impacts of the urban built environment on traffic carbon emissions: New insights from machine learning techniques. Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. The nonlinear effects of multi-scale built environments on CO2 emissions from commuting. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 118, 103736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Lee, E.H. Party politics in transport policy with a large language model. Transp. Policy 2025, 171, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H. eXplainable DEA approach for evaluating performance of public transport origin-destination pairs. Res. Transp. Econ. 2024, 108, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningbo Data Open Platform. Available online: http://data.ningbo.gov.cn/nbdata/fore/index.html/#/home?t=1678288126718&id=1 (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- OpenStreetMap. Available online: https://vdatahub.mapplus.cn/export#map=6/26.224/110.874 (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Amap. Available online: https://lbs.amap.com/ (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC). Available online: https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset/c0c49cd7-4a80-4a94-8c34-375289c12b2d (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Wu, J.; Jia, P.; Feng, T.; Li, H.; Kuang, H. Spatiotemporal analysis of built environment restrained traffic carbon emissions and policy implications. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Liu, T.; Cao, X.; Tian, L. Illustrating nonlinear effects of built environment attributes on housing renters’ transit commuting. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 112, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W. Nonlinear and interactive effects of complex built environment on travel-related CO2 emissions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Population per neighborhood | Ningbo Data Open Platform [32] |

| Road length | Road length in neighborhoods (km) | Open Street Map [33] |

| Expressway road density | Length of expressway road per unit area (km/km2) | Open Street Map |

| Primary road density | Length of primary road per unit area (km/km2) | Open Street Map |

| Secondary road density | Length of secondary road per unit area (km/km2) | Open Street Map |

| Parking lot density | The number of parking lots per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI [34] |

| Bus station density | The number of bus stations per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Subway station density | The number of subway stations per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Residential area density | The number of residential areas per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Charging station density | The number of charging stations per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Restaurant density | The number of restaurants per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Leisure facility density | The number of leisure facilities per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Financial service density | The number of financial services per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Education facility density | The number of education facilities per unit road length (POI/km) | Amap POI |

| Median speed | Median vehicle speed (km/h) | Ningbo Data Open Platform |

| Measure Area | Background Concentration of CO2 (ppm) | Concentration of Traffic CO2 Beside Road (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| Tianyi Square district | 435.21 | 470.44 |

| High-tech district | 425.68 | 446.40 |

| Laojiangdong district | 426.20 | 449.24 |

| Measure Area | Function Area | Concentration of Traffic CO2 (ppm) | Prediction of Carbon Emissions (t/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tianyi Square | Commercial area | 24.22 | 164 |

| High-tech district | High-tech industrial zone | 20.72 | 101.06 |

| Laojiangdong district | Residential area | 23.04 | 161.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. An Explainable Machine Learning Method for Neighborhood-Level Traffic Emissions Prediction: Insights from Ningbo, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310819

Huang Y, Liu C, Fan Y, Zhao J, Zhang C, Cao Y, Zhang Y, Zhang S. An Explainable Machine Learning Method for Neighborhood-Level Traffic Emissions Prediction: Insights from Ningbo, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310819

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yizhe, Cunzhuo Liu, Yikang Fan, Jun Zhao, Chuanli Zhang, Yiwei Cao, Yibin Zhang, and Shuichao Zhang. 2025. "An Explainable Machine Learning Method for Neighborhood-Level Traffic Emissions Prediction: Insights from Ningbo, China" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310819

APA StyleHuang, Y., Liu, C., Fan, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, C., Cao, Y., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, S. (2025). An Explainable Machine Learning Method for Neighborhood-Level Traffic Emissions Prediction: Insights from Ningbo, China. Sustainability, 17(23), 10819. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310819