Abstract

The dynamic relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and sustainable development has become a central topic of inquiry for academics and policymakers with rapid global economic growth. This study aims to clarify the impact mechanism and regional heterogeneity of FDI on total factor productivity (TFP) of Chinese high-tech enterprises, providing empirical evidence for optimizing foreign investment policies and promoting sustainable growth of enterprises. We utilized panel data from 30 provinces in China from 2009 to 2022. The DEA-Malmquist index method is firstly employed to dynamically measure the TFP of high-tech enterprises, while a static panel model is utilized to empirically test the impact of FDI on TFP. A particular emphasis is then placed on analyzing the regional heterogeneity of technology spillovers. The findings reveal that FDI significantly enhances both the production efficiency and the technological innovation capacity of high-tech enterprises overall, thereby facilitating the sustainable growth of enterprises. Furthermore, technological innovation emerges as the core driving force behind TFP growth, whereas the expansion of labor input significantly decreases efficiency improvements. Notably, the technology spillover effects of FDI illustrate significant heterogeneity across different regions and types of enterprises. To promote the sustainable development of high-tech enterprises, this study provides evidence-based insights for foreign direct investment technologies to better enhancing the overall sustainable competitiveness of the economy in China.

1. Introduction

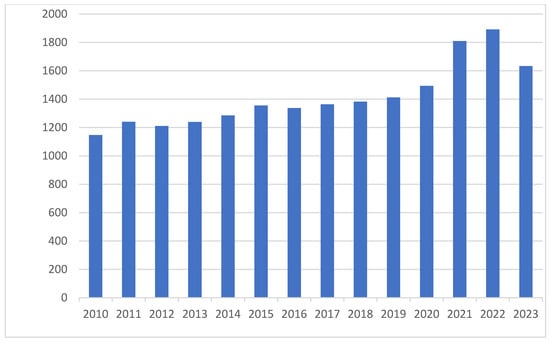

As the global economy undergoes rapid transformation, the relationship between FDI and sustainable development has emerged as a key concern for both scholars and policymakers. FDI, serving as a crucial channel for cross-border knowledge, technology, and capital, has long been recognized as a vital mechanism for host countries to access advanced technologies and enhance productivity. Its significance is particularly pronounced in the field of high technology, where it promotes improvements in enterprise productivity, fosters technological innovation, and underpins sustainable development. Attracting FDI constitutes a fundamental pathway toward achieving sustainable growth and technological advancement. As shown in Figure 1, since 2010, the scale of China’s actual utilization of foreign direct investment has been continuously expanding. In 2010, China’s actual utilization of foreign investment was 114.73 billion US dollars, and by 2022, this figure has increased to a maximum of 189.13 billion US dollars, firmly ranking second in the world, which has facilitated technology diffusion and reinforced the sustainable development of the industrial landscape. High-tech enterprises, characterized by their potential for technological innovation, are at the forefront of driving breakthroughs in core technologies and nurturing sustainable innovation ecosystems. Their sustainable development has significant implications for the transformation of the national economy and social progress. In 2020, profits within China’s high-tech sector rose by 16.4% year-on-year, accounting for 17.8% of total industrial profits. By 2022, the high-tech industry represented 36.1% of the actual utilization of foreign investment, underscoring its role as a core engine of high-quality development.

Figure 1.

Actual utilization of foreign direct investment in China from 2010 to 2023. Data source: National Bureau of Statistics.

Conceptual explanations are provided in this article. Sustainable growth refers to the coordinated improvement of economic benefits, technological progress, and environmental and social impact through technological innovation, efficient resource utilization, and eco-friendly models in the long-term development of enterprises, rather than a stable growth state of simple scale expansion. Technology spillover refers to the indirect effects of advanced technology, management experience, etc., brought about by FDI inflows, which spread to local enterprises in the host country through demonstration effects, personnel mobility, industry linkages, and other channels, and promote their technological advancement. TFP refers to the comprehensive output efficiency of all input factors (capital, labor, etc.) in the production process, and is a core indicator reflecting the contribution of intangible factors such as technological progress and management optimization to economic growth.

Despite existing literature that has established theoretical frameworks on the relationship between FDI and productivity, there still exist such research gaps. Firstly, the current literature has concentrated on developed economies or the manufacturing sector as a whole, and lack of targeted analyses on high-tech enterprises in developing countries, thereby limiting the applicability of findings. Secondly, common senses are lacking regarding the specific mechanisms such as the pathways of technology spillovers through which FDI influences the TFP of high-tech enterprises in China, with a particular absence of systematic exploration into the causes of regional differences. Thirdly, key moderating variables, including industry concentration and governmental support, are frequently overlooked in empirical analyses, and a comprehensive framework integrating multidimensional control variables with regional heterogeneity has yet to be established. Furthermore, the existing methodologies often fail to employ the synergistic capabilities of the DEA-Malmquist index and panel models, complicating the accurate capture of the relationship between dynamic changes in TFP and the impacts of FDI.

In response to these identified research gaps, we put forward the following three hypotheses in this study:

Hypothesis 1.

FDI exerts a significant positive impact on the TFP of Chinese high-tech enterprises, primarily driving technological innovation and efficiency improvements through technology spillover effects.

Hypotheses 2.

There exists considerable regional heterogeneity in the spillover effects of FDI-derived technology, with the eastern region exhibiting positive spillovers attributable to strong absorption capabilities, while the central, western, and northeastern regions experience relatively moderate spillover effects due to constraints related to factor endowments and technology compatibility.

Hypotheses 3.

Technological innovation positively influences TFP growth in high-tech enterprises, whereas the expansion of labor input adversely impacts TFP improvements, with these effects remaining consistent across various regions.

To fill the research gap, this article uses panel data from 30 provinces in China from 2009 to 2022, combined with DEA-Malmquist index and static panel model, and incorporates multidimensional control variables such as industrial concentration and technological innovation level to systematically measure the direct impact of FDI on the TFP of high-tech enterprises. China is divided into four major regions: East, Central, West, and Northeast, and the mechanism by which differences in factor endowments and innovation capabilities affect technology absorption efficiency is analyzed. We make three contributions in this study: (1) Firstly, focusing on high-tech enterprises, constructing a robust control variable and regional heterogeneity integration analysis framework, and clarifying the boundary conditions of FDI’s impact on sustainable growth of enterprises. (2) Secondly, by combining the DEA-Malmquist index with panel models, this study systematically reveals for the first time the causes of differences in technology spillovers among the four major regions: knowledge transfer in the east, technology mismatch in the central region, incremental absorption in the west, and imbalance in human capital in the northeast. (3) The third is to provide empirical support for the formulation of differentiated foreign investment policies in the region, and to assist high-tech enterprises in achieving sustainable positioning within the framework of economic development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background on Technology Spillovers

Technology spillover refers to the indirect influence of FDI on the technological progress of enterprises or enterprises in host countries, facilitated by knowledge transfer, diffusion, or demonstration effects from multinational corporations without the latter receiving direct compensation. The theoretical discourse surrounding technology spillover effects has undergone significant evolution over the past half-century. Since the 1960s, the economists have used modern economic methodologies, including game theory and strategic analysis, to construct a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding technology spillovers. This framework incorporates various dimensions, such as the developmental stages of countries, regional economic characteristics, and the market environments of host countries. Findlay (1987) developed a dynamic model illustrating the process of technology diffusion through direct investment from developed to developing countries, highlighting the increasing characteristic of technology transfer [1]. Likewise, Grossman et al. (1991) introduced an innovation-driven mechanism, indicating the pathways through which FDI fosters growth in host country total factor productivity via technology diffusion channels [2]. Buckley and Casson (1976) analyzed the global strategic logic of multinational corporations from a transaction cost perspective [3]. This organizational innovation generates dual technological spillover effects: on the supply side, multinational corporations establish research and development (R&D) centers and conduct technical training in host countries, thus cultivating knowledge diffusion channels. On the demand side, domestic firms often use R&D investments to enhance their reverse engineering capabilities, striving to transcend technological barriers imposed by multinational entities.

Notably, studies in developed countries often emphasize innovation-driven spillovers, whereas research in developing contexts, such as Kokko (1994, 1996) on Mexico and Uruguay, highlights the role of technological gaps and absorption capacity [4,5]. Kokko (1994, 1996) utilized cross-sectional industry data from Mexico and Uruguay to investigate technology spillover effects [4,5]. He observed that a smaller technological gap between the host country and the spillover source (i.e., the multinational corporation) correlates with a greater extent of spillovers, indicating an inverse relationship. Anwar (2014) conducted an empirical analysis of manufacturing firms in Vietnam, revealing that FDI spillover effects exhibit considerable regional heterogeneity [6]. Positive impacts on total factor productivity through backward linkages were primarily observed in four coastal regions, including the Red River Delta, while other areas demonstrated negative or negligible outcomes. Abdullah and Chowdhury (2020) examined panel data from 77 middle- and low-income countries, concluding that FDI does not significantly enhance TFP in these contexts, suggesting that insufficient absorption capacity within host countries may be a critical factor behind this phenomenon [7]. Collectively, these studies show that the impact of FDI on productivity is mediated by multiple factors, including the host country’s economic development level, regional characteristics, and absorption capacity. Furthermore, the interaction between technology spillovers and total factor productivity (TFP) is complex. The spillovers can enhance TFP through knowledge diffusion, but their effectiveness depends on host country conditions, such as innovation infrastructure and firm capabilities.

2.2. Measurement of Total Factor Productivity (TFP)

The high-tech industry in China has experienced remarkable growth. As noted by Schreyer and Pilat (2001), output growth can be achieved through two channels: increasing factor inputs and enhancing productivity levels [8]. Total Factor Productivity (TFP) has become a widely recognized indicator of productivity levels, frequently employed to assess sustainable development and economic growth among enterprises (Po-Chi et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021) [9,10,11]. Current studies on TFP mainly employ two methodologies: parametric and nonparametric approaches. The parametric method, particularly stochastic frontier production, describes the production frontier by determining TFP through an appropriate frontier production function. Conversely, the nonparametric method, exemplified by Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), utilizes linear mathematical programming to identify the production frontier, gaining extensive application in productivity analysis (Zhu et al., 2022) [12]. Among these methodologies, the Malmquist index method, proposed by Malmquist in 1953 based on the DEA framework, serves as a key indicator of TFP growth, which was first employed as a productivity index by Caves et al. (1982) and further developed by Färe et al. (1984) [13,14]. The DEA-Malmquist index method has been extensively utilized to measure productivity growth and decompose the pathways of sustainable development (Chen and Ali, 2004; Liu and Wang, 2008; Huang et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020) [15,16,17,18].

2.3. Empirical Studies on China’s High-Tech Industry

While the literature on high-tech enterprises is relatively limited, with a predominant focus on R&D efficiency rather than total factor productivity (Zhang et al., 2019; An et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020), many scholars have turned their attention to the technical efficiency and total factor productivity within these sectors, emphasizing their implications for sustainable economic growth [19,20,21]. Consequently, the measurement of productivity in China’s high-tech enterprises has gained attention from researchers across multiple levels. Numerous studies have employed the Malmquist index to estimate productivity changes within high-tech sectors. Liu and Ye (2006) analyzed the technical efficiency of these sub-sectors, revealing that TFP growth stems from accelerated technological progress, which is an essential driver of sustainable development [22]. Wei and Wang (2009) utilized the Malmquist index to assess TFP in high-tech enterprises and their sub-sectors, uncovering instability in overall TFP growth rates due to fluctuations in technological advancement [23]. Wang and Zhu (2011) applied the DEA-Malmquist method to compute and decompose TFP in China’s high-tech enterprises, indicating that the declines in TFP were linked to the pace of technological progress [24]. Similarly, Feng and Wang (2012) investigated TFP changes and technical efficiency across five major enterprises, concluding that increases in TFP were largely attributable to technological innovations [25]. Moreover, Xu and Li (2016) employed the DEA-Malmquist framework to examine the efficiency of technological innovation in China’s high-tech sectors, highlighting that technological progress constitutes the major contributor to TFP growth across various enterprises [26]. Recent studies have further focused on the complex role of FDI in TFP growth within emerging economies. Li et al. (2023), examining Myanmar’s manufacturing sector, revealed a nuanced spillover pattern where backward linkages positively impacted TFP, while horizontal spillovers showed adverse effects, underscoring the critical role of absorption capacity [27]. Concurrently, the study on China’s high-tech industries demonstrated that the relationship between FDI and TFP is significantly mediated by the bias of technological progress, with the alignment between this bias and the industrial factor structure being a key determinant of FDI’s ultimate impact on productivity [28].

Furthermore, some scholars underline the persistent regional imbalances in the evolution of high-tech enterprises, indicating an urgent need for studies on productivity variations across different regions. Li (2010) utilized a nonparametric Malmquist index method to assess TFP in China’s high-tech enterprises and revealed substantial declines in productivity across various regions, notably indicating that the eastern region lacks competitive advantages in TFP [29]. Wu and Liu (2011) calculated inter-provincial TFP for high-tech sectors in China using the Malmquist index and found negative TFP growth rates in 19 regions [30]. Their analysis revealed that 43% of provinces experienced technological progress, while 67% lacked scale efficiency. Jiang (2013a) further employed the DEA-Malmquist method to measure TFP and its decomposition across China’s high-tech enterprises, reinforcing the idea that technological progress drives TFP growth in most regions [31]. Yan et al. (2014) applied the DEA-Malmquist index to evaluate TFP changes across 30 provinces from 1996 to 2010, and found significant disparities in technological progress but an observable trend toward interregional convergence in TFP growth [32]. In contrast to the eastern regions, central and western areas exhibited a notable enhancement in technological efficiency, contributing positively to TFP growth.

Additionally, some scholars propose that the high-tech industry can be divided into two sub-stages: the initial focus on technological development and the subsequent pursuit of economic transformation. Outputs from the first sub-stage serve as critical inputs for the second, enhancing the need for efficient innovation across different sections. Wang et al. (2020) established a two-stage DEA evaluation framework for high-tech enterprises, sharing inputs, intermediate inputs, and final outputs, indicating that overall efficiency remains relatively low among most enterprises, with significant variations present across the five major high-tech sectors [33]. Yu et al. (2021) introduced a network DEA model to analyze innovation performance within high-tech enterprises, revealing pronounced differences in innovation outcomes among various Chinese high-tech firms [34]. Moreover, scholars have thoroughly examined the influencing factors of TFP growth in high-tech enterprises, primarily focusing on themes of innovation efficiency, R&D investment, and industrial structure optimization. Connolly et al. (2006) analyzed the impact mechanism of high-tech capital accumulation on industrial productivity in Australia, emphasizing the critical role of capital deepening in fueling productivity enhancements [35]. In exploring the relationship between R&D investment and productivity, Higon (2007) demonstrated that intra-industry R&D investments and spillovers substantially promote productivity growth within high-tech sectors, while the effects of transnational R&D spillovers prove limited [36]. This finding offers valuable insights into the spatial dynamics of R&D investments. Hsiao et al. (2005) employed the Malmquist index to compare productivity among traditional manufacturing, basic manufacturing, and high-tech manufacturing in South Korea and Taiwan, China, revealing significant disparities in productivity growth patterns across regions and manufacturing types [37].

In summary, the current literature establishes the critical role of FDI-induced technology spillovers and TFP measurement in understanding high-tech industry growth. However, persistent ambiguities remain, particularly regarding the FDI-TFP relationship in the unique context of China’s high-tech enterprises and the integrated role of multidimensional control variables. Building on the foundational work of scholars such as Kokko (1994) [4] on absorption capacity and Anwar (2014) [6] on regional heterogeneity, this study selects a system of control variables including industrial agglomeration, technological innovation, government support, and firm size to address this gap. This study contributes by proposing testable hypotheses and by employing a combined DEA-Malmquist and panel data approach. Our findings aim to provide new insights into the role of FDI in fostering sustainable development and productivity enhancement, offering theoretical implications for refining foreign investment and industrial policies.

3. Research Design and Data Sources

3.1. Model Specification and Variable Selection

To investigate the impact of foreign direct investment on total factor productivity within high-tech enterprises, this study formulates the following linear benchmark regression model:

where represents the total factor productivity of the high-tech industry in region i during period t, used to measure the production efficiency and technological progress level of the high-tech industry in that region; represents the amount of foreign direct investment in the high-tech industry in region i during period t, reflecting the capital investment and market participation level of foreign capital in the high-tech industry of that region; represents the scale of labor input in the high-tech industry in region i during period t; represents the capital input in the high-tech industry in region i during period t; indicates the degree of industrial agglomeration of high-tech enterprises in region i during period t, measured by the number of locational enterprises; indicates the level of technological innovation of high-tech enterprises in region i during period t; indicates the degree of government support for high-tech enterprises in region i during period t; indicates the enterprise scale characteristics of high-tech enterprises in region i during period t, is the intercept term. Additionally, the model controls for regional heterogeneity by introducing regional fixed effects , absorbs the impact of macroeconomic cyclical fluctuations using time fixed effects , and is a random disturbance term following an independent and identically distributed process.

3.1.1. Explained Variable

Regional TFP of high-tech enterprises is of considerable importance in academic research, with methodologies including the Solow residual method, stochastic frontier analysis, and data envelopment analysis (DEA). While the Solow residual method is grounded in classical economic theory, its application needs strict assumptions of constant returns to scale and neutral technological progress. Although the stochastic frontier analysis method has refined the approach to determining the frontier surface, it still requires empirical models with certain constraints, such as pre-specifying the type of production function and estimating output elasticity parameters. These preconditions introduce a degree of subjectivity that may influence measurement results. In contrast, the non-parametric data envelopment analysis method offers greater flexibility and applicability: by constructing a multi-dimensional efficiency frontier based on input-output datasets, this method effectively avoids the strict constraints associated with traditional production function forms and mitigates potential systematic biases in parameter estimation. Relying solely on objective data, the DEA approach not only enhances the universality of empirical analysis but also facilitates the systematic identification of the driving forces behind productivity growth by decomposing technical and scale efficiency. Given the focus on examining the evolution of efficiency within enterprises and the utilization of high-dimensional sample data, the DEA-Malmquist index model is particularly well-suited for capturing the dynamic characteristics of total factor productivity. Consequently, this study develops a cross-period Malmquist index system to comprehensively measure and analyze changes in total factor productivity across high-tech enterprises in China.

The formula for the DEA-Malmquist index model is as follows:

where is the total factor productivity index, which measures the change in TFP from period t to t+1. A value greater than 1 indicates an increase in productivity, while a value less than 1 indicates a decrease. and represent the input and output quantities in periods t and t+1, respectively. The distance function is used to measure the distance (i.e., efficiency value) between the current period (period t) DMU and the production frontier, using the technology of period t as a reference. Thus, D∈ (0,1], where D = 1 indicates that production in this period is on the frontier (fully efficient). represents the efficiency value of the DMU in period t+1, measured across periods using the technology of period t as a reference. > 1 indicates that efficiency has improved relative to the technology of period t, and the geometric mean measured using the technology standards of two periods is used to eliminate base period selection bias, thereby ensuring symmetry.

Regarding the decomposition mechanism of the Malmquist index, Färe et al. (1994) proposed the classic decomposition framework (FGNZ model), which constructs a two-dimensional decomposition system of “efficiency change (EC)—technological progress (TC)” [38].

By adjusting Equation (3), the Malmquist total factor productivity index can be decomposed into the technical efficiency change index (EC) and the technical progress index (TC). EC represents the actual change in the utilization efficiency of production technology from period t to t+1 (distance change), i.e., when EC > 1, technical efficiency improves, bringing the DMU closer to the production frontier, indicating that the DMU has more effectively utilized existing technology.

As shown in Equation (4), TC represents the movement of the production frontier itself (technological innovation or decline). When TC > 1, technological progress occurs, and the frontier expands outward. It is worth noting that Term 1 = is used to measure the efficiency difference between the two technologies in period t+1. If the denominator is larger, it indicates that the technology in period t+1 is more advanced, resulting in Term 1 < 1. However, due to the expansion of the frontier caused by technological advancement in period t+1, the old DMU becomes relatively more backward, i.e., Term 2 = > 1, which makes TC = > 1. Therefore, TC reflects the net effect of technological progress, influenced by the disproportion of technological change.

Within this modeling framework, changes in total factor productivity can be further divided into two dimensions: pure technical efficiency changes (PEC) and scale efficiency changes (SEC), as shown in Equation (6).

Based on the total factor productivity evaluation index system, we used the DEAP 2.1 software Malmquist index model (based on DMU = province year), and summarized the high-tech industry indicators at the provincial level to calculate the total factor productivity of 30 provincial-level high-tech industry administrative regions from 2009 to 2022 under the condition of constant scale efficiency.

3.1.2. Explanatory Variable

FDI: Given data availability constraints, this study adopts the internal R&D expenditures of foreign-invested enterprises in each region as a proxy for FDI, in alignment with the research conducted by Jin (2016) [39].

3.1.3. Control Variables

To mitigate the influence of potential disturbance factors and avoid multicollinearity while maintaining representativeness, this study selects the following key control variables grounded in existing research findings:

Labor Input (L): To fully utilize the promotive role of FDI in driving technological progress, developing countries must possess the essential capabilities for technology absorption. In this context, human capital serves as a vital channel for knowledge dissemination and technological innovation, directly influencing the host country’s efficiency in absorbing FDI-induced technological spillovers. Moreover, FDI can significantly promote technological advancement in developing nations only when the accumulation of human capital reaches a critical threshold. Consequently, this study employs the number of R&D personnel, measured in full-time equivalent terms, to represent labor input within high-tech enterprises.

Capital Input (K): Considering the production characteristics inherent to high-tech enterprises, this study measures capital input by utilizing expenditure on instruments and equipment within these sectors. The core competitiveness of high-tech enterprises is predominantly evident in their R&D innovation capabilities and advanced manufacturing levels. In this context, instruments and equipment serve as the material foundation for R&D activities, thereby providing a direct reflection of the intensity of a company’s investment in research and development.

Industrial Agglomeration Degree (AG): This study measures industrial agglomeration by examining the number of high-tech industry enterprises that engage in local R&D activities. From the perspective of industrial synergy effects, the spatial concentration of R&D-oriented enterprises fosters enhanced knowledge spillovers and facilitates technology diffusion. The defining characteristic of high-tech enterprises is their innovation-driven development. Thus, only those enterprises involved in R&D can truly reflect the technological agglomeration effects within the sector. This indicator, as opposed to simple enterprise count statistics, provides a more precise reflection of the agglomeration level of regional innovation factors, effectively excluding low-end manufacturing enterprises that lack robust R&D capabilities from the assessment.

Technological Innovation Level (Tech): In line with the framework established by Liang (2015), this study employs the number of invention patent applications in high-tech enterprises as a metric for assessing technological innovation levels [40]. As a significant output of technological innovation, the volume of invention patent applications provides a direct reflection of a company’s R&D achievements and innovation capabilities. In comparison to utility model and design patents, invention patents are subject to more strict authorization standards, thereby more accurately capturing original technological breakthroughs that are characteristic of high-tech enterprises.

Government Support (Gov): In accordance with the methodology established by Yang et al. (2018), this study utilizes the proportion of government funding to the internal R&D expenditure of high-tech enterprises as a proxy variable to assess the level of governmental support for these sectors [41].

Enterprise Size (Size): As posited by Chen et al. (2004), enhancements in R&D efficiency necessitate a scale effect, with enterprise size positively correlating to R&D productivity [42]. Consequently, building upon the work of Ai et al. (2021), this study measures average enterprise size within each region by calculating the ratio of total high-tech output value to the number of high-tech enterprises in that region [43].

This study selected the above variables as control variables, which not only fit the production characteristics of high-tech enterprises with R&D innovation as the core, but also comprehensively avoid potential interference and multicollinearity. Labor input and capital input are the fundamental elements of production activities, directly affecting the absorption efficiency of FDI technology spillovers. The degree of industrial agglomeration and the level of technological innovation reflect the regional innovation ecology and core capabilities of enterprises, which are closely related to the technology diffusion effect of FDI. Government support and enterprise size, respectively, reflect the external policy environment and internal scale effects, both of which affect the total factor productivity of enterprises. Including control can ensure the accuracy and effectiveness of FDI’s impact assessment on TFP. It is worth noting that numerous studies concurrently employ R&D personnel, measured in full-time equivalents, alongside internal R&D expenditure to quantify labor and capital inputs. However, given the high correlation between the two within empirical research, this study utilizes only one of these variables as a measure of labor input. Furthermore, to mitigate heteroskedasticity and minimize the impact of extreme values, this study performs a log transformation on all the aforementioned data, thereby compressing the data scale and enhancing comparability across the dataset. The variable selection and data calculation methodologies are succinctly summarized in Table 1:

Table 1.

Variable selection and sources.

3.2. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

This study mainly draws upon two data sources: firstly, the statistical yearbooks published by provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions spanning from 2010 to 2022; and secondly, the “China High-Tech Industry Statistical Yearbook” for the same period. These official statistical datasets provide a robust empirical foundation for the research. In terms of industry selection, the study refers to the provisions outlined in “Detailed Classification of High-Tech Enterprises (Manufacturing)” (the National Bureau of Statistics), concentrating on manufacturing sectors characterized by high R&D intensity. The focus is narrowed to five primary enterprises: pharmaceutical manufacturing, electronic and communication equipment manufacturing, aerospace manufacturing, computer and office equipment manufacturing, and medical instruments and equipment manufacturing. Through data processing, linear interpolation was employed to estimate missing data from 2017 in instances where the 2018 China High-Tech Industry Statistical Yearbook did not publish relevant figures, which ensured the integrity of the time-series data. Due to significant data gaps in key indicators such as FDI and R&D expenditure within the Tibet, as well as the exclusion of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao from the statistical framework, the analysis ultimately encompasses 14 years of panel data from 30 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions. As for isolated missing data in certain regions and years, linear regression methods were utilized to provide reasonable estimations. Throughout the data processing phase, all monetary values were standardized to “billion RMB” units. To mitigate heteroskedasticity and enhance data comparability, all variables used log transformation in the analysis of the impact of FDI on TFP.

To investigate the differentiated impact of FDI across various regions, this study categorizes the 30 provincial-level administrative regions into four major economic areas, in accordance with the regional classification standards set forth by the National Bureau of Statistics. These regions include the Eastern Region (including Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan), the Central Region (including Shanxi, Jiangxi, Hubei, Hunan, Anhui, and Henan), the Western Region (including Chongqing, Sichuan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Xinjiang), and the Northeast Region (including Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning). This regional classification approach helps to explain the regional heterogeneity of FDI’s impacts on the total factor productivity of high-tech enterprises.

Following statistical analysis, the descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. The standard deviations for FDI, technological innovation (Tech), and capital input (K) are relatively large, indicating substantial disparities among provinces in terms of levels of foreign direct investment, technological innovation, and capital allocation. These findings provide a solid foundation for subsequent analyses tailored to specific regional contexts.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

This study used robust modeling methods for regression analysis of data, which combine random effects models (RE) with individual fixed effects, time fixed effects, and bidirectional fixed effects models. Based on the Hausman test results (chi2 (7) = 13.06, Prob > chi2 = 0.0707), the RE model is preferred for its effectiveness in controlling unobservable regional heterogeneity, while mitigating the degree of freedom loss that may occur in fixed effects models (FE) that contain a large number of regional dummy variables. Due to the relatively limited explanatory power of time fixed effects and bidirectional fixed effects models, the RE model and regional individual fixed effects model are the main focus of this analysis.

As shown in Table 3, the test results from the random effects (RE) model show that FDI exerts a significant positive influence on the TFP of high-tech enterprises. Specifically, a 1% increase in FDI-R&D funding corresponds to an average increase of 0.041% in TFP, which remains statistically significant at the 1% level. This effect holds strong even after accounting for regional variations and two-way fixed factors. Furthermore, the results from the time fixed-effects model demonstrate that, when only the temporal dimension is controlled for, the model becomes insignificant, and the effect shifts from positive to negative. This finding reveals the substantial role of regional differences in shaping the impacts of FDI on productivity.

Table 3.

Regression results on the impact of FDI on TFP.

In terms of factor inputs, the investment in human capital reveals a significant negative effect on TFP, with a 1% increase in human capital investment correlating with a reduction in TFP of 0.422%. This finding maintains significance in both the regional fixed effects model and the two-way fixed effects model, although it weakens in the time fixed effects model, where the coefficient is −0.113. This difference suggests a potential imbalance between the structure of available talent and the demands of industry, or it may indicate institutional barriers hindering inter-regional talent mobility. Conversely, capital input shows mixed significance, which is only significant at the 10% level in the random effects (RE) model, but reaches significance at the 5% level in both the fixed effects (FE) model and the two-way fixed effects model. This variation notes that the impact of capital input on TFP depends on regional contexts.

The impact of industrial agglomeration on TFP is found to be insignificant and negative in both the random effects (RE) and fixed effects (FE) models. Conversely, it is significant and positive in both the time fixed-effects and two-way fixed-effects models. The significance observed when controlling for time effects suggests that the technological spillover benefits associated with industrial agglomeration can only be fully realized within a dynamic temporal context.

The contribution of technological innovation levels to TFP is the most obvious, with a coefficient of 0.459 (p < 0.01), demonstrating a positive and significant impact across all modeled conditions, indicating the pivotal role of innovation-driven growth in enhancing productivity.

Notably, government support demonstrates a positive but statistically insignificant effect in the other models, while it attains significance and reaches its maximum effect (0.137) in the time fixed-effect model. This observation suggests that the influence of government support may be more closely tied to general temporal trends at the national level, which indicates that policy subsidies are likely aligned with the macroeconomic cycle with a limited causal relationship between government support and productivity outcomes.

4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

Recognizing the significant variances in factor endowments, policy environments, and capabilities for attracting foreign investment across regions in China, we classified the provinces into four major regions: Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeast based on the High-Tech Industry Statistical Yearbook to facilitate comparative analysis. Each region was subjected to a Hausman test and the Eastern, Central, and Northeast regions passed the test, indicating that the random effects (RE) model is more appropriate for these areas. In contrast, the Western region was determined to be better suited for the fixed effects (FE) model. The final results derived from these various models are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Heterogeneity analysis of major regions in China.

As illustrated in Table 4, FDI significantly boosts total factor productivity across eastern, western, and northeastern regions in China, with the most significant effect observed in the northeastern region (0.180), followed by the eastern region (0.094), and the weakest impact noted in the western region (0.067). In contrast, the central region displays a non-significant negative effect. Furthermore, technological progress significantly enhances total factor productivity in all regions except for the central region. Labor input, on the other hand, exerts a significant negative influence across all regions, with the coefficient for the Northeast (−1.149) being three times greater than that of the East.

The empirical results for the eastern region indicate that FDI significantly enhances TFP, with a coefficient of 0.094, consistent with the theory of technology spillovers. In this region, the substantial capital expenditures by foreign-invested enterprises (0.050) alongside high levels of technological innovation (0.417) yield a synergistic effect, validating the effectiveness of the “knowledge transfer” mechanism inherent in technology spillover theory. Conversely, the adverse effects of competitive pressures are also apparent that the firm size coefficient (−0.373) suggests that expansionary development may hinder efficiency improvements. However, government support shows a positive effect, with a coefficient of 0.098, indicating that policy measures can effectively enhance efficiency. From the perspective of appropriate technology theory, the relatively modest negative impact of the labor coefficient (−0.374), especially in comparison to regions where labor input positively affects productivity, reflects the robust human capital reserves in eastern regions.

The central region presents a particularly unique case. The negative FDI coefficient (−0.042) fails to pass the significance test, underscoring the dilemma posed by the threshold effect inherent in negative effects theory. This mismatch of factors is evident in the coexistence of a capital investment coefficient of 0.222, a number of enterprises coefficient of 0.282, and a technological innovation capability coefficient of −0.201. Applying the theory of suitable technology analysis reveals that the introduction of foreign technology is misaligned with the local factor structure. The flow of advanced technologies appears to surpass the region’s capacity for absorption, resulting in a failure to translate these innovations into outputs, and thus the efficiency of research and development innovation in the central region remains low. Moreover, government support has not effectively enhanced technology spillovers, with a non-significant coefficient of 0.017, which suggests that rather than fostering innovation, FDI may aggravate market segmentation within the region.

In the western region, FDI is found to enhance efficiency improvements, evidenced by a coefficient of 0.067, thereby supporting the increasing development path outlined in the appropriate technology theory. The relatively low technological barriers, indicated by a constant term of 1.539, facilitate the absorption of foundational technologies introduced by foreign-invested enterprises. Additionally, industrial support policies, as reflected in the government support coefficient of 0.029, have contributed to some extent in driving the reallocation of factors, further resulting in efficiency enhancements. However, the constraints posed by human capital are pronounced. The full-time equivalent coefficient of −0.471 reveals a significant mismatch between labor skills and the requirements of foreign-invested technologies, suggesting that the “human capital mobility effect” posited in technology spillover theory is not effectively realized in this context.

The remarkable promotional effect of FDI on TFP in Northeast China, with a coefficient of 0.180, significantly higher than other regions. This phenomenon may be attributed to the robust industrial foundation in this region, as indicated by a constant term of 8.252, as well as effective policy coordination, evidenced by a government support coefficient of 0.309, which together enhance the positive impacts of foreign investment. However, the obvious contrast between the technological innovation coefficient (0.549) and the labor input coefficient (−1.149) highlights an issue of mismatched human capital development from an overreliance on capital-intensive technologies, as reflected in the relatively low capital input coefficient of 0.024, which highlights the challenges faced in coordinating technological advancement with the local labor market’s capabilities.

The above results demonstrate the regional conditionality of technology spillover effects: (1) the eastern regions exemplify the ideal model of utilizing FDI to foster technology-driven development; (2) the central regions need to deal with FDI displacement effects stemming from technology mismatches; (3) the western regions demonstrate steady progress characterized by a “gradual absorption” approach; (4) the northeastern regions reveal a disjunction between FDI-driven innovation and human capital development. Positive technology spillovers can only be realized when the complexity of FDI technologies dynamically aligns with local factor endowments, institutional environments, and industrial foundations.

4.3. Endogeneity Test

When analyzing the impacts of FDI on the TFP of high-tech enterprises, there may exist a bidirectional causal relationship between these variables. On one hand, FDI may enhance TFP through mechanisms such as technology spillovers, management experience sharing, and other channels. On the other hand, enterprises characterized by higher TFP typically exhibit stronger technological absorption capabilities and greater market competitiveness, thereby making them more attractive to FDI inflows. This endogeneity issue poses significant challenges, potentially leading to biased results in traditional estimation methods.

To effectively tackle the issue of endogeneity, this study employs the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method for estimation in conjunction with the Hausman test. In the selection of instrumental variables, we recognize that FDI decisions frequently exhibit temporal continuity, and thus the lagged value of FDI from the previous period, denoted as FDIt-1, is utilized as the instrumental variable.

The regression results presented in Table 5 demonstrate that the instrumental variables have successfully passed the strict validity test. Specifically, the instrumental variables in the first-stage regression model exhibit significance at the 1% level, with a test statistic of F = 365.134, substantially exceeding the conventional threshold of 10. Furthermore, the adjusted R2 of 0.859 in the first stage shows robust explanatory power for these variables.

Table 5.

Two-stage test results.

Following the validation of the instrumental variables, the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test was performed to assess the exogeneity of FDI with respect to total factor productivity. As illustrated in Table 6, the null hypothesis notes that all explanatory variables are exogenous, which is not rejected the p-values exceed 0.05, indicating the absence of endogeneity in the model.

Table 6.

Durbin–Wu–Hausman test for exogeneity.

4.4. Robustness Test

This study employs the methodology proposed by Xia (2017) to ensure the robustness of the research findings [44]. Specifically, the variable for new product development expenses was excluded from the input factors, prompting a recalibration of the TFP within the high-tech industry. The descriptive statistics for the recalculated TFP (denoted as new TFP) and its logarithmically transformed counterpart (TFP2) are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of the new TFP.

The Hausman test results demonstrate that the random effects (RE) model is more suitable for this analysis (χ2(6) = −18.167, p = 1.000). The findings from the panel data analysis are presented in Table 8. Notably, after adjusting the TFP calculation methodology, the regression coefficient for FDI remains constant and statistical significance, corroborating the robustness of the experimental results.

Table 8.

Results of the re-regression.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study focuses on the essential role of foreign direct investment (FDI) in fostering sustainable productivity growth among high-tech enterprises through the application of multidimensional modeling methodologies. The empirical findings reveal that FDI significantly enhances both the production efficiency and technological innovation capabilities of these enterprises, thereby establishing a robust foundation for their sustainable development. Notably, this positive impact exists when accounting for temporal and regional heterogeneities. Our results verify the validity of our initial hypothesis (H1), demonstrating that FDI exerts a substantial positive influence on TFP within Chinese high-tech enterprises, primarily by driving technological innovation and efficiency improvements via technology spillover effects.

Among the variables examined, technological innovation emerges as the primary factor for TFP growth, as evidenced by a patent application coefficient of 0.459, which underscores the significant positive effect of innovation quality on productivity enhancement. Conversely, investments in human resources exhibit a notable negative impact, indicating negative effects on TFP growth in regional analyses. This finding reflects a weakening demographic dividend, while the anticipated human capital dividend has yet to be fully realized, which aligns with the expectations outlined in Hypothesis 3, confirming that technological innovation positively influences TFP growth in high-tech enterprises, whereas increased labor input inversely affects productivity improvements.

Analysis of regional heterogeneity reveals substantial variations in technology spillover effects, in line with Hypothesis 2. In the eastern region, a favorable alignment of technology absorption capacity and factor endowments allows FDI to yield considerable technological dividends through strong spillover effects. Conversely, in the central region, technological mismatches and limitations in absorption capacity inhibit local innovation increase. Meanwhile, the western region, bolstered by policy coordination and strategic redistribution of resources, is steadily advancing towards technological catch-up. In the Northeast, however, a structural imbalance in human resources creates a mismatch with technology absorption, thus impeding the full realization of FDI benefits.

Despite achieving these significant findings, this study acknowledges several limitations. Firstly, there is a reliance on a single proxy variable for FDI, which is quantified only by actual foreign investment utilization within each province and overlooks the differentiated impacts of sub-dimensions such as the sources and modes of foreign investment (e.g., greenfield investments versus mergers and acquisitions) on technology spillover effects. Secondly, some provinces exhibited missing data for certain years, which were supplemented using linear interpolation, which may introduce biases that affect result accuracy. Thirdly, the omission of spatial econometric models overlooks the spatial correlations of FDI flows between regions and the attendant spatial spillover effects of technology dissemination, thereby complicating the ability to comprehensively capture the interactive mechanisms.

To address these limitations, future research could be improved in several ways: first, by refining the FDI proxy variable system to incorporate multidimensional indicators including technological level, investment mode, and equity structures of foreign investment sources, thus providing a more accurate measure of FDI’s impact on TFP in high-tech enterprises. Second, employing more data imputation techniques could improve the handling of missing data or, alternatively, supplement macro panel data with micro-level enterprise research to enhance data quality. Third, incorporating spatial econometric models such as the spatial Durbin model and spatial lag model into the analysis could facilitate a deeper investigation of spatial correlations and spillover effects arising from FDI technology dissemination, expanding the scope of regional heterogeneity research. Lastly, further studies could target the micro-level dynamics of enterprises, employing case analysis methods to explore the complex transmission mechanisms through which FDI influences TFP in high-tech sectors.

Given the importance of enhancing total factor productivity through foreign direct investment, our findings may stimulate policy discussions about what strategies should be developed to promote sustainable development in high-tech enterprises. Firstly, enhancing the mechanisms for FDI attraction and technology spillover facilitation is critical. This necessitates accurately matching high-tech industry demands, prioritizing the attraction of technology-intensive foreign investment projects, and establishing technology exchange platforms to facilitate spillover channels, thereby improving sustainable development for high-tech enterprises. Secondly, it is suggested to address human resource challenges by shifting the labor resource focus from “quantity dividends” to “quality dividends”. This can be achieved through strengthened training initiatives and strategic recruitment of professionals in high-tech domains, optimizing talent incentive structures to enhance the role of human capital in TFP growth. Furthermore, fostering the development of regional collaborative innovation networks and establishing cross-regional technology cooperation mechanisms is essential to facilitate the transfer and diffusion of advanced technologies from the eastern to the central, western, and northeastern regions, thereby bridging technological development gaps and promoting the sustainable growth of high-tech enterprises. Finally, a dynamic policy adjustment framework should be established to enhance policy adaptability and innovation incentives. In the eastern region, this could involve encouraging the transition of FDI from traditional processing and manufacturing towards high value-added sectors, such as research and development and design. For the central region, a mechanism to evaluate the applicability of foreign technologies should prioritize the introduction of medium-complexity technology projects that align with local absorption capabilities. Considering the opportunities presented by the “Belt and Road” initiative, the western region should focus on attracting FDI that emphasizes infrastructure development and specific application products. In the Northeast, foreign investment participation is encouraged in the transformation and upgrading of industrial bases will facilitate the realization of targeted FDI technology spillover benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and X.F.; methodology, S.Z.; software, X.F.; validation, X.T., Y.H. and X.F.; formal analysis, X.T., Y.H. and X.F.; investigation, X.T., Y.H. and X.F.; resources, X.T., Y.H. and X.F.; data curation, X.T., Y.H. and X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z. and X.F.; writing—review and editing, X.T., Y.H. and S.Z.; visualization, X.T., Y.H. and S.Z.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20230390), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (N2406017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study mainly draws upon two data sources: firstly, the statistical yearbooks published by provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions spanning from 2010 to 2022; and secondly, the “China High-Tech Industry Statistical Yearbook” for the same period.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Findlay, R. Free Trade and Protection; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Quality Ladders in the Theory of Growth. Review of Economic Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, P.J.; Casson, M. The Multinational Enterprise in the World Economy. In The Future of the Multinational Enterprise; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kokko, A. Technology, Market Characteristics, and Spillovers. J. Dev. Econ. 1994, 43, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokko, A.; Tansini, R.; Zejan, M.C. Local Technological Capability and Productivity Spillovers from FDI in the Uruguayan Manufacturing Sector. J. Dev. Stud. 1996, 32, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Nguyen, L.P. Is foreign direct investment productive? A case study of the regions of Vietnam. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Chowdhury, M. Foreign Direct Investment and Total Factor Productivity: Any Nexus? Margin J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2020, 14, 164–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreyer, P.; Pilat, D. Measuring productivity. OECD Econ. Stud. 2001, 33, 127–170. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-C.; Yu, M.-M.; Chang, C.-C.; Hsu, S.-S. Total factor productivity growth in China’s agricultural sector. China Econ. Rev. 2008, 19, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y. China’s agricultural green total factor productivity based on carbon emission: An analysis of evolution trend and influencing factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xie, R.; Ma, C.; Fu, Y. Market-based environmental regulation and total factor productivity: Evidence from Chinese enterprises. Econ. Model. 2021, 95, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Aparicio, J.; Li, F.; Wu, J.; Kou, G. Determining Closest Targets on the Extended Facet Production Possibility Set in Data Envelopment Analysis: Modeling and Computational Aspects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 296, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, D.W.; Christensen, L.R.; Diewert, W.E. The economic theory of index numbers and the measurement of input, output, and productivity. Econometrica 1982, 50, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Lovell, C.K. The structure of technical efficiency. In Topics in Production Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1984; pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Ali, A.I. DEA Malmquist productivity measure: New insights with an application to computer industry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 159, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-H.F.; Wang, P.-H. DEA Malmquist productivity measure: Taiwanese semiconductor companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 112, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Du, D.; Hao, Y. The driving forces of the change in China’s energy intensity: An empirical research using DEA-Malmquist and spatial panel estimations. Econ. Model. 2017, 65, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Song, Y.-Y.; Pan, J.-F.; Yang, G.-L. Measuring destocking performance of the Chinese real estate industry: A DEA-Malmquist approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 69, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Luo, Y.; Chiu, Y.-H. Efficiency evaluation of China’s high-tech industry with a multi-activity network data envelopment analysis approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2019, 66, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Meng, F.; Xiong, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X. Assessing the relative efficiency of China’s high-tech enterprises: A dynamic network data envelopment analysis approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 290, 707–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gao, X.; Ma, W.; Chen, X. Research on regional differences and influencing factors of green technology innovation efficiency of China’s high-tech industry. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2020, 369, 112597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ye, Z. An Empirical Analysis on Technical Efficiency of China’s Hi-Tech Industry: A Nonparametric Malmquist Index Approach. Sci. Sci. Manag. 2006, 9, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.B.; Wang, S.J. Measuring and Comparing Total Factor Productivity in China’s High-Tech Enterprises. Value Eng. 2009, 10, 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.P.; Zhu, Y.C. The Efficiency Sources of Chinese Hi-tech Enterprises. China Sci. Technol. Forum 2011, 7, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F.; Wang, M.M. Research on the Promotion of Efficiency in High-Tech Enterprises from the Perspective of Total Factor Productivity. J. Northwest A&F Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2012, 12, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.Q.; Li, C.B. Research on Technology Innovation Efficiency of High-tech Industry Based on DEA-Malmquist. Pioneer. Sci. Technol. Mon. 2016, 24, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mon, A.M. Research on the Spillover Effects of Foreign Direct Investment on Total Factor Productivity (TFP) in Myanmar’s Manufacturing Industry. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, Nanchang, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.T. Research on the Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Total Factor Productivity of China’s High-Tech Industries. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University of Finance and Economics, Lanzhou, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.D. Decomposition of Total Factor Productivity Changes in China’s High-Tech Enterprises—Non-parametric Malmquist Index-Based Method. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2010, 8, 247–249. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.X.; Liu, M.F. Spatial differences and causes analysis of total factor productivity in China’s interprovincial high-tech industry. Sci.-Technol. Manag. 2011, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.T. Study on the Total Factor Productivity of High-tech Industry in Different Provinces of China. J. Shandong Norm. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 58, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Yu, L.P.; Song, X.Y. A Factor Analysis of Total Factor Productivity Differences in China’s High-Tech Industry. Sci. Technol. Econ. 2014, 27, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, J.-F.; Pei, R.-M.; Yi, B.-W.; Yang, G.-L. Assessing the technological innovation efficiency of China’s high-tech industries with a two-stage network DEA approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 71, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Shi, Y.; You, J.; Zhu, J. Innovation performance evaluation for high-tech companies using a dynamic network data envelopment analysis approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 292, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, E.; Fox, K.J. The impact of high-tech capital on productivity: Evidence from Australia. Econ. Inq. 2006, 44, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higón, D.A. The impact of R&D spillovers on UK manufacturing TFP: A dynamic panel approach. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, F.S.; Park, C. Korean and Taiwanese productivity performance: Comparisons at matched manufacturing levels. J. Prod. Anal. 2005, 23, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Zhang, N.Z. Productivity Growth, Technical Progress and Efficiency Change in Industrialized Countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.Y.; Wang, W.Q. The Nonlinear Effects of FDI Technology Spillovers in China’s High-Tech Industry: An Empirical Test Based on Panel Data of Domestic and Foreign Enterprises in 13 Sub-sectors. Ind. Econ. Rev. 2016, 7, 41–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Foreign Direct Investment, Technological Innovation, and Total Factor Productivity: An Empirical Analysis Based on Interprovincial Panel Data. Explor. Econ. Issues 2015, 9, 9–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, X.; Tang, L. Evaluation of High-Tech Industrial Development Efficiency and Regional Influencing Factors in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Res. Macroecon. 2018, 8, 68–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.T.; Chien, C.F.; Lin, M.H.; Wang, J.T. Using DEA to Evaluate R&D Performance of the Computers and Peripherals Firms in Taiwan. Int. J. Bus. 2004, 9, 347–360. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, Y.; Peng, D. Autonomous Innovation, Opening Up, and Total Factor Productivity in High-Tech Industries: An Absorption Capacity Perspective. Financ. Econ. 2021, 9, 68–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xia, C.Y.; Luo, Z. Research on the Improvement of R&D Efficiency in High-Tech Industries along the ‘Belt Road’ Provinces. J. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2017, 36, 31–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).