1. Introduction

In the study of emergency service facility location, core decision criteria have traditionally emphasized coverage, reliability, cost-effectiveness, and, more recently, social equity [

1,

2]. Within the broader agenda of sustainable urban development and disaster risk reduction, these criteria must increasingly reflect the differentiated needs of vulnerable groups and the long-term performance of urban shelter systems [

3,

4]. To address these evolving requirements, this study develops a robust two-stage emergency shelter location–allocation model designed to minimize construction costs and evacuation distances while promoting equitable access, embedding social resilience in disaster planning, and supporting the long-term sustainability of urban shelter networks [

5].

The modern theory of facility location originated from early conceptualizations of “location” in the late nineteenth century and gradually evolved into formal optimization frameworks focused on minimizing distances between supply facilities and demand points [

6]. The classical continuous formulation introduced in 1929 cast the problem as minimizing the total distance between a warehouse and its customers [

7]. Subsequent scholarship systematized facility location problems into four foundational model families—p-median, p-center, set covering, and maximal covering—each addressing distinct operational objectives and service constraints [

8]. Within this classification, the p-median model aimed to minimize total weighted distances between demand nodes and selected facilities [

9], while later integer-programming formulations enabled exact optimization for increasingly complex spatial systems [

10]. Further refinements expanded these models into more general discrete location–allocation frameworks applicable across diverse contexts [

11]. Lagrangian-relaxation algorithms were developed to decompose and accelerate p-median computations for large-scale systems [

12], followed by additional algorithmic enhancements that improved convergence and solution quality [

13].

Complementary to average-distance minimization, the p-center model emerged to minimize the maximum distance between demand points and their nearest facility, including an absolute-center variant for single-facility problems [

14]. Binary-search procedures combined with maximal-covering logic further strengthened the computational performance of p-center and related formulations [

15]. Parallel research introduced the location set-covering model, which determines the minimum number of facilities required to meet predefined coverage standards for all demand points [

16]. This was further complemented by maximal-covering models that sought to maximize covered demand under limited facility budgets [

17].

Building on these foundations, emergency-oriented facility location models increasingly emphasized meeting strict time or distance constraints with minimal installations [

18]. Early formulations defined target response times or service distances and optimized facility placement to ensure full coverage with the fewest sites [

19]. Subsequent studies accounted for the stochastic nature of travel times, integrating probabilistic elements into set-covering models to determine facility requirements under uncertain service guarantees [

20]. To address the limitations of single coverage, double-coverage models were introduced to ensure that demand points remained adequately served even in cases of facility failure [

21]. Maximal accessibility models then incorporated emergency vehicle occupancy and facility reliability, capturing more realistic service availability under congestion or partial system disruption [

22].

Advances in robust and stochastic optimization further expanded the literature. Robust p-median models explicitly incorporated uncertainties in demand and network conditions to enhance solution stability, while stochastic set-covering approaches extended coverage planning to probabilistic disruption scenarios. Queue-based maximal-accessibility models integrated waiting times and congestion effects, offering improved performance evaluations for emergency response systems. These frameworks were subsequently adapted to healthcare planning, where maximal-covering models informed hospital location decisions aimed at improving medical service accessibility. Multi-objective models later combined construction and operational costs with coverage performance, enabling more balanced decisions under budgetary constraints. Additional work proposed minimizing maximum operational distances within discrete intervals to improve system regularity, while integrated strategies for allocating both new and existing hospital beds enhanced emergency treatment capacity under resource limitations. Generalized set-covering models introduced flexible thresholds and partial coverage options, and hierarchical covering models structured decisions across multiple service tiers, enabling progressively optimized emergency facility systems [

23].

Recent developments highlight the growing integration of spatial analysis and multi-criteria decision-making in emergency shelter planning. GIS-based spatial analysis has significantly improved urban emergency shelter site selection processes. For instance, Chen et al. [

24] combined systems theory with GIS technology to optimize shelter configurations in Guangzhou. Saadatseresht et al. [

25] used multi-objective evolutionary algorithms for evacuee allocation, though their work did not comprehensively address shelter distribution and capacity planning. Alcada-Almeida et al. [

26] optimized evacuation distances and risk trade-offs using multi-objective models, revealing opportunities to improve personnel allocation balance. Kulshrestha et al. [

27] applied robust optimization to address uncertainties in demand patterns, strengthening the adaptability of shelter planning. Li et al. [

28] examined evacuation proportions influenced by population density, hurricane intensity, and landfall locations, while Hu et al. [

29] analyzed the combined impacts of panic dynamics and government interventions on shelter requirements.

Further integration of spatial analysis with advanced decision-making is reflected in studies such as Anhorn et al. [

30], who evaluated shelter layouts in Kathmandu using suitability indicators and network accessibility metrics. Xia [

31] incorporated spatial and non-spatial datasets within a two-step floating catchment area framework to assess fire-facility accessibility. Kiran et al. [

32] employed analytic hierarchy processes to identify optimal disaster-prevention sites. Lee et al. [

33] used Gini coefficients and mobile data analytics to assess spatial equity and mobility patterns in Daegu, identifying persistent shelter distribution disparities. Yao et al. [

34] applied TOPSIS methods to evaluate shelter suitability on Vancouver Island, highlighting spatial deficiencies in safety and accessibility. European cases, particularly in Catania, Sicily, illustrate how optimized urban layouts can significantly enhance evacuation and refuge capacity following disasters.

Recent progress in meta-learning and feature optimization also offers methodological insights relevant to complex urban planning systems. Wan et al. [

35] proposed a task-adaptive selection mechanism within a meta-learning architecture that improves model generalization in heterogeneous environments. Wang et al. [

36] introduced channel-wise attention expansion to strengthen feature regularization, achieving a strong balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Leng et al. [

37] developed a feature distribution alignment strategy that enhances information sharing and robustness across data domains. These methodological advances—especially adaptive model tuning, robustness under limited data, and interpretable optimization—resonate with the heuristic design philosophy of the present study and suggest that intelligent learning approaches can inspire more flexible and adaptive emergency shelter planning solutions.

In conclusion, extensive theoretical and applied research has established a strong foundation for facility site selection in emergency contexts. However, rapid urbanization and increasingly complex disaster environments reveal persistent gaps in model adaptability, spatial accessibility, and equity—factors central to sustainable urban development. Integrating spatial analysis with advanced multi-criteria decision-making techniques represents a critical and promising research direction. Responding to these challenges, this study develops a robust two-stage emergency shelter location–allocation model that merges spatial analytics with dynamic multi-criteria optimization. Through a case study in Jinniu District, Chengdu, the proposed Phased Nested Local Search (PNLS) framework demonstrates its ability to incorporate equity constraints, manage spatial and demand uncertainties, and achieve adaptive trade-offs between assignment efficiency and spatial fairness, thereby contributing to sustainable urban disaster risk reduction.

2. Model Construction and Solution Methods

2.1. Pre-Disaster Stage: Robust Emergency Shelter Location Model

The proposed two-stage location–allocation model integrates both technical factors (such as shelter siting and evacuation efficiency) and social considerations (such as equitable access for vulnerable populations). In the pre-disaster stage, the robust location model minimizes construction costs while ensuring shelters’ capacity for worst-case scenarios. The post-disaster phase uses a multi-objective allocation model that optimizes both total and maximum evacuation distances while incorporating fairness constraints to prioritize vulnerable populations (such as the elderly, disabled, and low-income groups) in shelter assignments. This approach balances efficiency with social equity, ensuring that all evacuees, especially those in disadvantaged positions, have equitable access to shelter.

The following assumptions are made: (1) Each community is represented by its geographic center, concentrating all evacuees at this point. (2) All evacuees walk to their assigned shelter along the shortest available path. (3) Evacuees from the same community are allocated to the same shelter. (4) Peak demand during the evacuation period is used as the planning basis.

In the pre-disaster phase, the robust location model aims to minimize shelter construction costs and, through robust optimization, ensure that selected shelters can meet uncertain peak demand scenarios within budget constraints.

The urban emergency shelter location problem can be represented as a bipartite graph , where R denotes the set of all residential areas requiring service, and S denotes the set of candidate emergency shelter locations selected after initial screening. Let r = ∣R∣ be the number of residential areas and s = ∣S∣ be the number of candidate shelter sites.

After a disaster, the evacuation demand in residential area i∈R may fluctuate. In this model, Di denotes the baseline number of evacuees from residential area i at the peak demand time after a disaster. Each candidate shelter j∈S has a maximum capacity cj (number of people), as well as a fixed construction cost fj.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are used to compute the actual shortest path distance between residential area i and shelter j. The maximum service coverage radius for shelters is set as L. Residential area i can only be effectively served by shelter j if . Accordingly, we define the coverage sets: as set of residential areas covered by shelter j; as the set of candidate shelters capable of serving residential area i.

Two types of binary decision variables are introduced: yj indicates whether an emergency shelter is established at candidate site j; yj = 1 if selected, yj = 0 otherwise. xij indicates whether evacuees from residential area i are assigned to shelter j; xij = 1 if assigned, xij = 0 otherwise.

Objective Function (Minimize Construction Cost):

Constraints are:

(1) Each residential area must be assigned to exactly one open shelter:

This constraint ensures that all evacuees from a given residential area are assigned to one shelter, and implicitly enforces the evacuation distance does not exceed the maximum service radius L.

(2) The total number of evacuees assigned to any selected shelter cannot exceed its capacity, even under worst-case demand fluctuations:

Here, denotes the maximum potential increment of evacuees from residential area i relative to the baseline demand , capturing the magnitude of uncertainty. The robust parameter Γ represents the maximum number of residential areas simultaneously experiencing increased demands. When Γ = 0, it reflects a deterministic scenario, while a larger Γ corresponds to a more conservative scenario.

(3) Evacuees can only be assigned to shelters that are operational:

This constraint ensures evacuees are only placed in shelters that have been selected for use.

(4) Decision variables are binary:

2.2. Post-Disaster Stage: Multi-Objective Evacuee Allocation Model

The post-disaster allocation phase involves tactical and operational decision-making, assigning evacuees from each residential area to the established shelters. This stage considers multiple objectives such as evacuation efficiency, fairness, and safety. A multi-objective optimization model is constructed, seeking to minimize the total evacuation distance while also controlling the maximum individual evacuation distance. The model accounts for constraints on shelter capacity, assignment distance, and evacuation path capacity.

Let the set of open shelters determined by the site selection phase be , where . In this phase, only assignments to shelters in S′ are considered, and each residential area must still be assigned to a single shelter.

Objective 1 (Minimize total evacuation distance):

This objective minimizes the sum of all evacuees’ travel distances, improving overall evacuation efficiency.

Objective 2 (Minimize maximum evacuation distance):

This objective minimizes the longest distance any residential area must travel, enhancing fairness and safety.

Thus, the allocation model is a bi-objective optimization, balancing efficiency and individual risk. Multi-objective solution techniques, such as weighted sum or lexicographic methods, can be used to obtain a compromise or Pareto-optimal solution.

Constraints:

Each residential area must be assigned to one open shelter:

The number of evacuees assigned to each shelter must not exceed its capacity:

The path from each residential area to its assigned shelter must support the evacuee flow:

Decision variables for allocation are binary:

In summary, constraints (6) to (11) together with the two objectives define the post-disaster allocation model. The solution ensures both efficiency and fairness under capacity and path constraints. The allocation model must be solved based on the open shelter set S′ determined by the site selection phase, making this a sequential two-stage decision process.

3. Algorithm Design and Solution Strategy

Building upon the modeling framework and assumptions presented in

Section 2, this section introduces the solution strategy for the two-stage shelter location–allocation problem. The overall methodological flow proceeds as follows: the first stage establishes the multi-objective formulation integrating efficiency, equity, and robustness; the second stage applies the Phased Nested Local Search (PNLS) algorithm to obtain near-optimal Pareto solutions. Each phase of PNLS corresponds to a specific layer of the model—shelter site selection, demand allocation, and solution refinement—ensuring logical consistency between the model’s structure and computational implementation.

To efficiently solve the proposed two-stage robust multi-objective shelter site-allocation model, this study designs a Phased Nested Local Search (PNLS) algorithm. The PNLS method is tailored to the features of site selection and evacuee allocation decisions, iteratively optimizing both stages while embedding robust uncertainty handling and Pareto-based multi-objective selection within a nested structure. The algorithm aims to deliver solutions that are robust to uncertain demand, while optimizing performance metrics such as evacuation distance.

The algorithm begins with parameter initialization and scenario generation. Let R be the set of residential areas and S the set of candidate shelters. The robust parameter Γ is specified, and a scenario set Ω is generated to represent a range of possible post-disaster demand conditions, including baseline and high-demand scenarios. For each scenario ω∈Ω, the demand for residential area i is denoted as . The parameter Γ defines the maximum number of locations that may simultaneously experience extreme demand. Each candidate shelter j has a capacity cj, and each path eee has a capacity Le. The coverage matrix [aij] is computed in advance, with aij = 1 if shelter j covers area i within the service radius, and 0 otherwise. The decision variables for site selection yj and allocation are initialized as undetermined. The solution set is used to store Pareto-optimal solutions and is initially empty.

In the first phase, a robust initial site selection is constructed to minimize the total construction cost while satisfying all robust constraints. An adaptive random sampling strategy is adopted. A probability vector

is defined over

S, initialized either uniformly or based on heuristic information such as population coverage. At each iteration

t,

N candidate site selection solutions

are generated according to

, and are evaluated for constraint satisfaction and objective value. The best-performing

of solutions are retained, and the probability vector is updated according to:

where

is the empirical frequency of shelter

j being selected among elites and

is a smoothing parameter. This process iterates until convergence or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

Each solution must satisfy two robust feasibility conditions. First, the selected sites must provide sufficient total capacity for the worst-case scenario, that is:

where

denotes the worst-case demand for area

i. For all selected shelters

j and scenarios

, the following must hold:

Second, each residential area must be covered by at least one selected site, i.e., for all , there exists such that . If any candidate solution is infeasible, a fast repair mechanism is triggered by adding additional shelters until all constraints are met. The feasible solutions and their objective values are stored in the Pareto set .

After robust site selection is completed and the set of open shelters

S′ determined, the second phase focuses on evacuee allocation optimization to minimize total evacuation distance and explore trade-offs between multiple objectives. In this phase, each residential area

i is assigned to a shelter

according to the following model:

subject to

where

denotes the evacuation distance from area

i to shelter

j. An initial feasible assignment is generated greedily by assigning each area to its nearest available shelter, respecting capacity and path limits. Local search is then applied using two neighborhoods: relocation, in which an area is reassigned to another feasible shelter, and swap, in which the assignments of two areas are exchanged, provided the moves maintain feasibility and improve the objective. The process iterates until no further improvements can be made.

Upon obtaining an optimized allocation, the objective values such as total cost F1 and total evacuation distance F2 are computed, and the solution is compared with existing elements in to update the Pareto set if a non-dominated solution is found. In order to explore more cost-performance trade-offs, the algorithm incorporates nested neighborhood adjustments on the open shelter set S′. Specifically, the process alternately adds, removes, or swaps shelters in S′, each time re-optimizing the allocation and updating if Pareto improvements are realized. Adding a shelter can potentially reduce evacuation distances at the expense of higher cost, while removing underutilized shelters may reduce cost without significantly increasing distance, provided feasibility is maintained. Swapping shelters allows local adjustment of the open site set to better align with demand distribution.

This nested local search proceeds until no further Pareto improvements are possible in either the site selection or allocation dimensions. The resulting Pareto set offers a diverse range of robust, non-dominated solutions, supporting flexible decision-making for urban emergency shelter planning under uncertainty. The design of the PNLS algorithm effectively integrates robust and multi-objective optimization, incorporates scenario-based demand uncertainty, path capacity, and trade-off analysis, and is well suited for practical large-scale disaster planning.

To guarantee convergence, the PNLS algorithm incorporates an elitist selection mechanism that retains non-dominated solutions across iterations, ensuring that the Pareto front never deteriorates. The local search phase employs a monotonic improvement rule, where new candidate solutions are accepted only if they improve at least one objective without violating feasibility. This prevents cycling and ensures steady progress toward convergence. Meanwhile, to maintain solution diversity, PNLS introduces neighborhood diversification and adaptive perturbation. Specifically, alternate use of “relocation,” “swap,” and “add/remove” operators expands the search across different regions of the solution space. When the algorithm detects stagnation (i.e., no improvement over a set number of iterations), controlled perturbations are triggered by probabilistically modifying the shelter set or assignment mapping, allowing exploration of unexplored neighborhoods. The nested structure—alternating between shelter-level and assignment-level optimizations—further enhances diversity by preventing premature convergence on suboptimal local optima. These mechanisms collectively ensure that PNLS converges efficiently while preserving a well-distributed Pareto front of diverse trade-off solutions.

4. Case Study: Jinniu District, Chengdu

To evaluate the efficiency of the proposed phased nested local search (PNLS) heuristic algorithm, computational experiments were conducted using sample instances on a standard PC with a Windows 11 operating system and Intel Core i7 CPU. The PNLS algorithm was implemented in Python 3.8, integrated with Gurobi 9.5 (academic license) for solving linear programming subproblems, while CPLEX 12.10 served as the benchmark solver. All tests were conducted using 8 CPU threads and 16 GB RAM, with the time limit set to one hour for each run of the exact solver.

Table 1 compares the performance of PNLS with commercial solvers across progressively larger sample instances. This aligns with the known complexity of location–allocation problems, which are NP-hard and challenging for exact solvers at larger scales. PNLS compromises exact optimality slightly to achieve significantly improved computational speed, a critical advantage for large-scale emergency planning requiring prompt decision-making. Notably, when CPLEX could still obtain an optimal solution, the PNLS heuristic consistently provided solutions within a 1–3% deviation from CPLEX’s best objective, confirming its solution quality.

Jinniu District, located in central Chengdu, Sichuan Province, was selected for the case study. The district borders Chenghua, Xindu, Qingyang, Jinjiang, and Pidu districts and features flat terrain with elevations ranging from 476.9 to 594 m and slopes approximately between 2‰ and 10‰. According to the 2022 Chengdu Statistical Yearbook, Jinniu District has a permanent population of approximately 1.28 million with an urbanization rate of 100%. Due to its proximity to the Longmen Mountain fault zone, Jinniu District faces a high risk of severe earthquakes. According to the China Seismic Hazard Zonation Map (GB 18306–2015), Chengdu is located within a seismic intensity zone of VII–VIII degrees, with a design basic acceleration of 0.20–0.30 g, indicating a high hazard level in the Sichuan Basin. Jinniu District lies approximately 18 km southeast of the Longmen Mountain central fault, where several strong earthquakes have occurred over the past decades. Historical earthquake records show that ground motions in central Chengdu frequently exceed 200 cm/s2 during major seismic events, and local geological surveys identify the area as predominantly class III sites with soft sedimentary layers that amplify ground motion by a factor of about 1.4–1.6. Combined with its dense population of about 1.28 million and high building concentration, these factors make Jinniu District highly vulnerable to earthquake-induced damage and secondary disasters. Therefore, improving the layout and capacity planning of emergency shelters in this district is of critical importance for enhancing urban seismic resilience.

This study assumes an earthquake scenario characterized as moderate-intensity (magnitude approximately M ≈ 7, focal depth h = 10 km, and an epicenter roughly 18 km from the district center). The peak ground velocity and pipeline failure rates following the earthquake were estimated using the local geological amplification effect (predominantly class III site with an amplification factor of 1.5) and the Molas–Yamazaki model from Japan, considering factors such as soil liquefaction and pipeline diameter. Residential building damage was projected based on data from the Wenchuan earthquake survey: approximately 12%–15% of residential buildings are expected to suffer severe damage or collapse, around 12% moderate damage, 22% minor damage, while about half remain essentially intact under seismic intensity VII. These parameters form the basis for evacuation demand estimations.

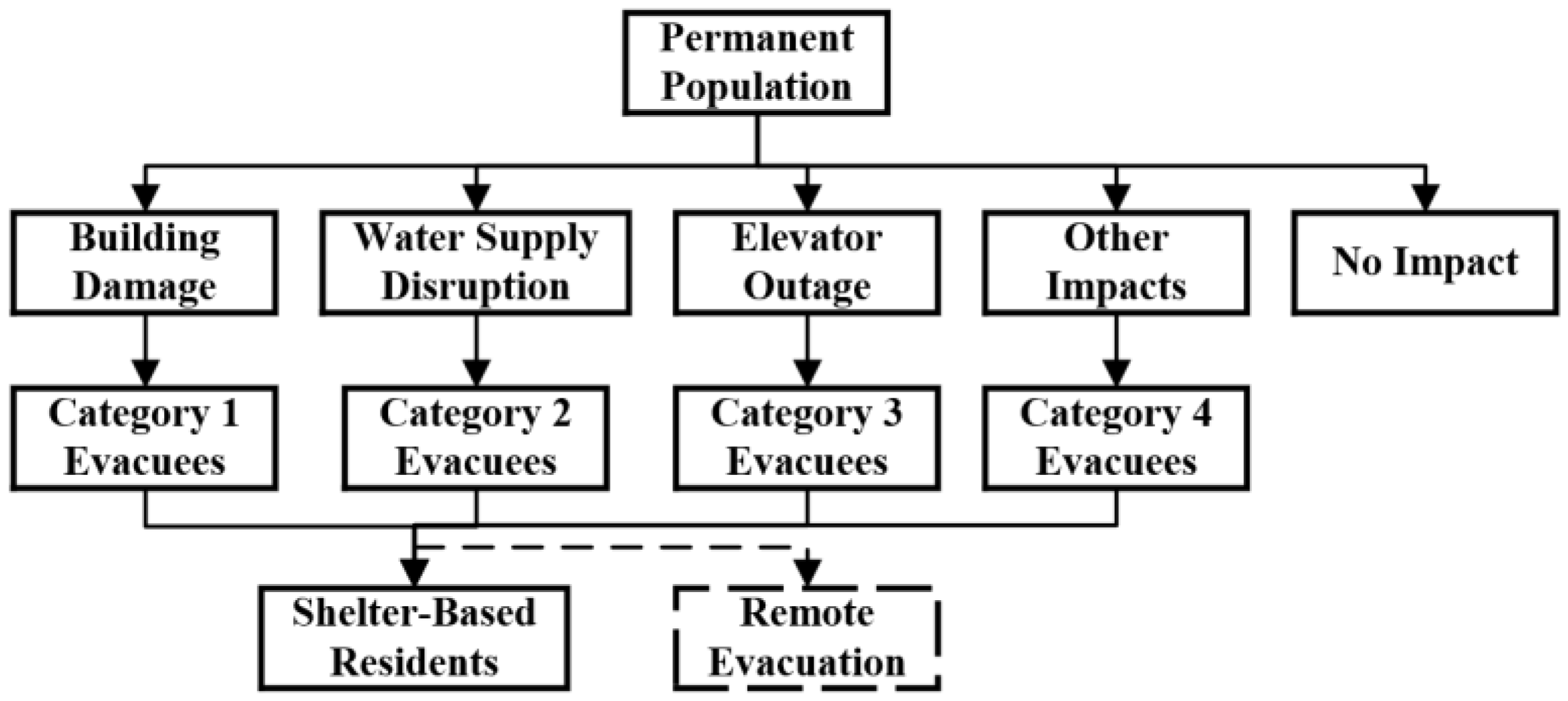

Evacuation demand post-earthquake primarily depends on building damage, loss of basic utilities such as water and electricity, and residents’ behavioral responses. This study integrates three primary factors into the demand analysis: housing damage, water supply disruptions, and power outages. Social factors like panic and misinformation were identified as having minor impacts and thus excluded from this model. The primary influencing factors for emergency evacuation demand are illustrated in

Figure 1, where dashed lines denote excluded socio-psychological elements.

To quantify the number of evacuees resulting from different post-earthquake factors, relevant model parameters must be specified and calculated. Based on the permanent population of Jinniu District (p = 1280, 200), and the previously estimated housing damage rates, the proportion of residents needing evacuation due to housing damage (denoted as h1, h2, etc.) can be determined. Under a seismic intensity VII scenario, the proportion of residents in completely destroyed or severely damaged housing is estimated as h1 ≈ 7%, those with moderate damage as h2 ≈ 12%, and those with minor damage or undamaged housing but affected by secondary factors as h3 ≈ 81%.

Here, residents corresponding to h1 and h2 become immediately homeless and require shelter after the earthquake. The h3 group refers to residents whose homes are basically intact but may experience temporary inconvenience due to loss of water or power.

Next, the proportion of the population needing evacuation due to infrastructure disruption is estimated based on population data and earthquake impact parameters. Calculations indicate that about 12–13% of Jinniu’s population may experience water supply disruption, and about 8% of high-rise residents may be affected by power outages such as elevator shutdowns (these groups may overlap with those affected by housing damage and should be considered together).

Finally, referring to the comprehensive evacuation demand model proposed by the Central Disaster Prevention Council of Japan, the proportion of each group actually choosing to evacuate to emergency shelters is specified as follows: for residents whose homes are destroyed, the evacuation rate is set as = 100%; for those with moderate damage, the evacuation rate is set empirically at approximately 50% ( = 50–60%), indicating that about half will go to shelters, while the rest may seek refuge with relatives or outdoors. For the group whose homes are intact but who temporarily evacuate due to water or power outages, the evacuation rate changes over time t, decreasing as utility services recover.

Following related research, this study models the time-dependent evacuation rate using an exponential decay function:

The infrastructure impact factor

describes the reduction in basic service disruption over time after the earthquake (assumed to decay exponentially).

The individual intolerance factor

reflects the residents’ tolerance for inconvenience, which tends to increase as time passes. Immediately after the earthquake (

t small), this value is near 1, indicating low tolerance.

The time-evolving evacuation rate is then set as

where parameters

,

,

,

are determined with reference to previous earthquake cases and local conditions. In this study, a set of values is adopted (

≈ 1.8,

≈ 0.22;

≈ 1.8,

≈ 4.4) to characterize the restoration of essential services and psychological adaptation in Jinniu District.

4.1. Evacuation Demand Estimation Method and Results

Using the parameters and models above, this paper estimates and analyzes the post-earthquake emergency shelter demand in Jinniu District.

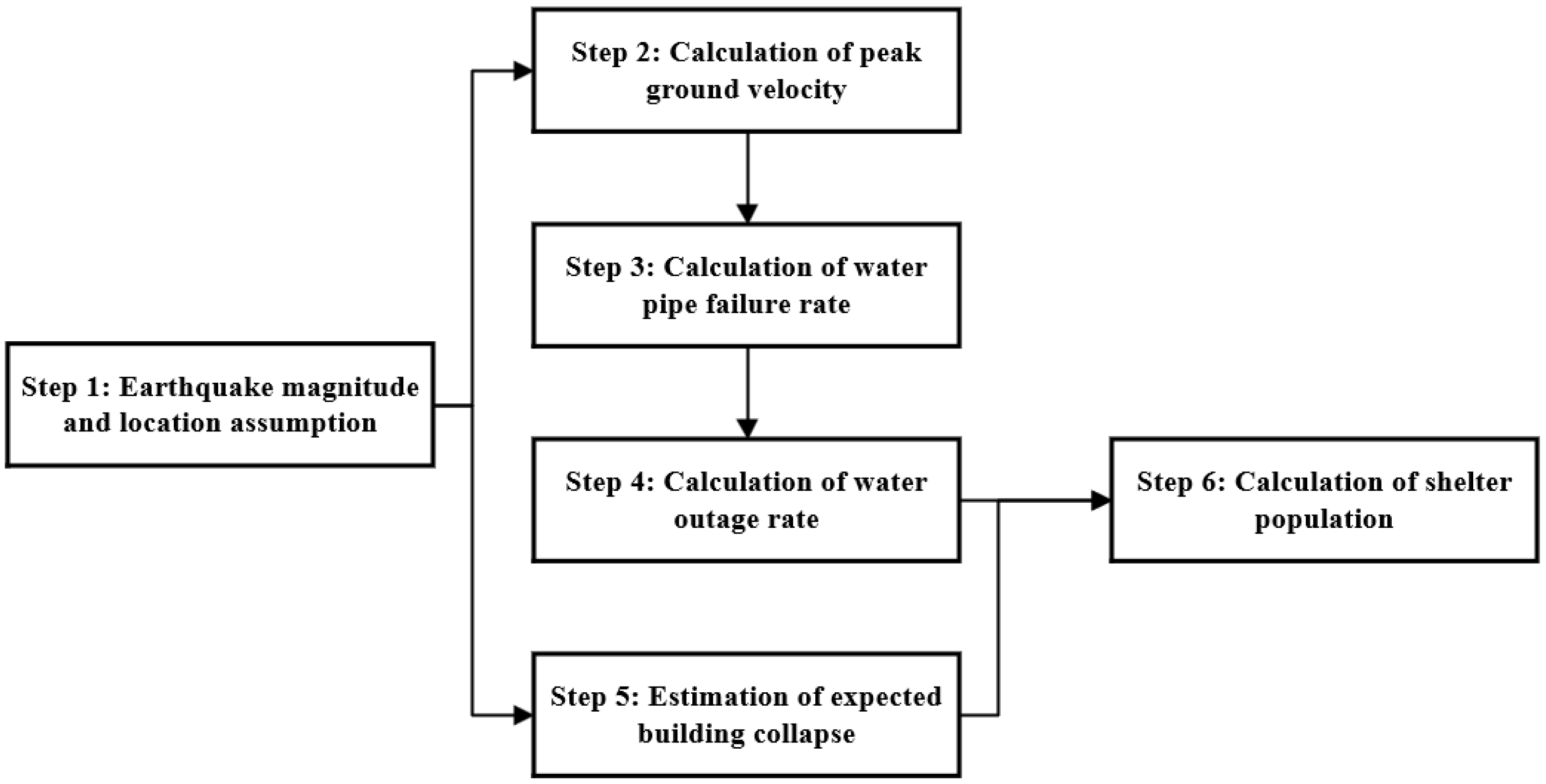

Figure 2 illustrates the calculation flow for evacuee numbers. The process first estimates the number of homeless residents due to housing destruction; then, the number affected by water supply disruption is calculated based on earthquake intensity, epicenter distance, and pipeline failure rates; subsequently, the number of residents affected by elevator outages is assessed. Finally, by integrating behavioral choice factors, the model yields the total number of evacuees as a continuous function of time after the earthquake.

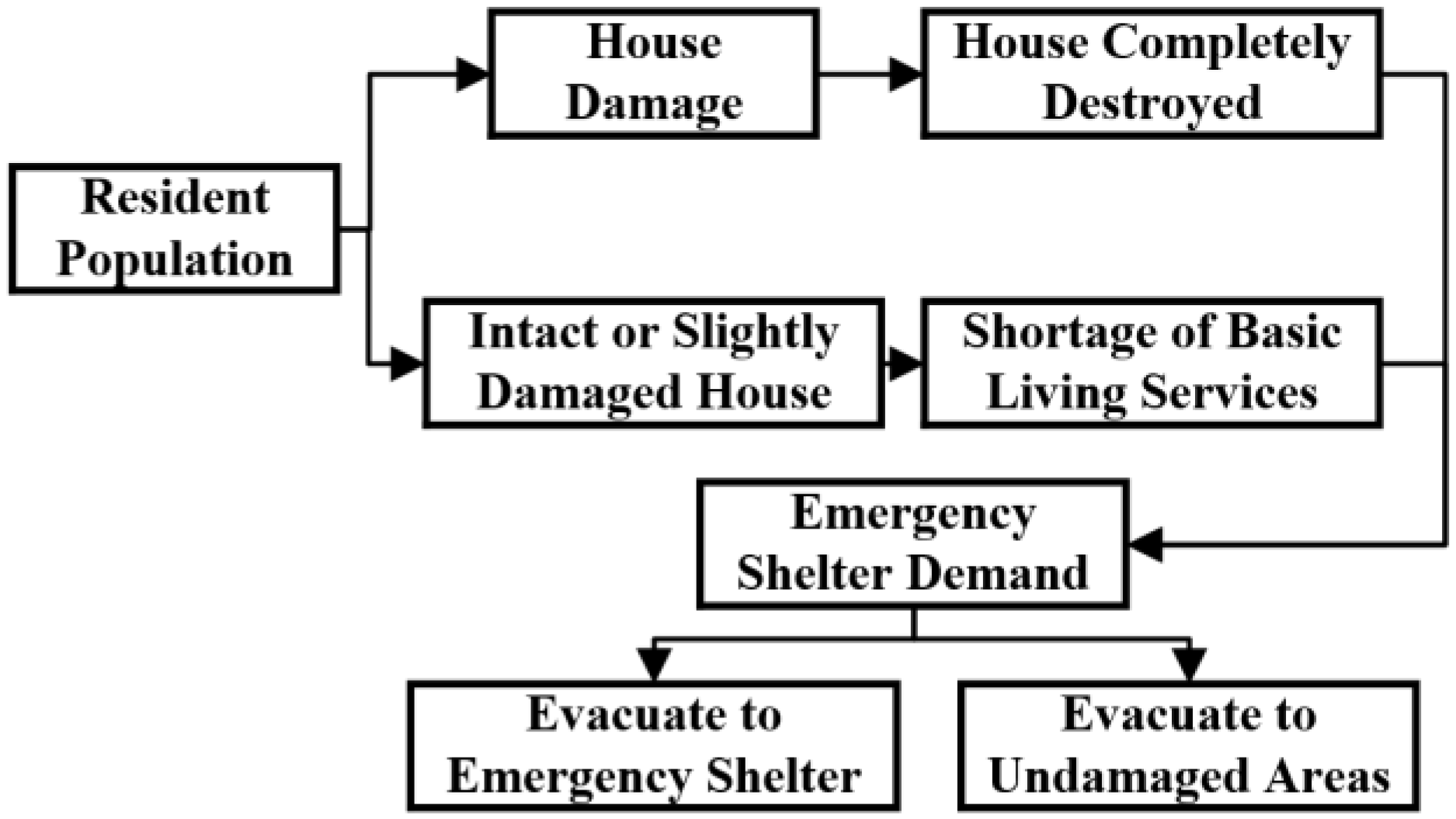

After completing the stepwise calculations above, the exponential model for the time-dependent evacuation rate

is introduced, resulting in a flowchart for the continuous estimation of evacuation demand over time, as shown in

Figure 3. The diagram illustrates the integration of engineering and human factors: for residents whose homes are completely destroyed or severely damaged, the evacuation rates

and

are assumed to remain constant over time, as these individuals are unable to return home in the short term. For residents whose homes are intact but who experience inconvenience in daily life, the rate

is modeled as a decreasing function over time, reflecting the gradual return of this group as basic utilities are restored.

Figure 3 provides an equivalent representation of this process, with key formulas and parameter relationships annotated to highlight the core methodology for continuously estimating time-varying evacuation demand.

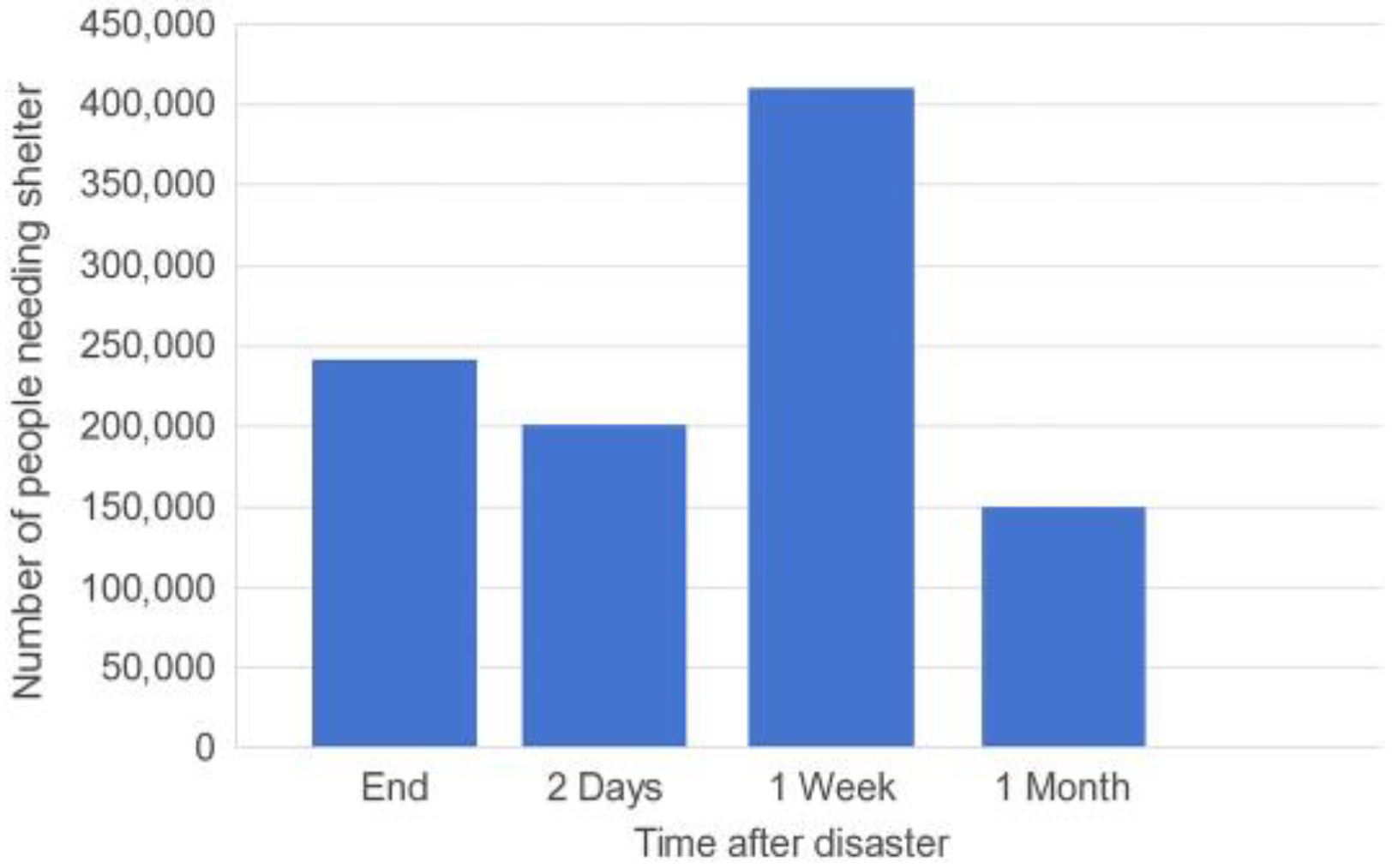

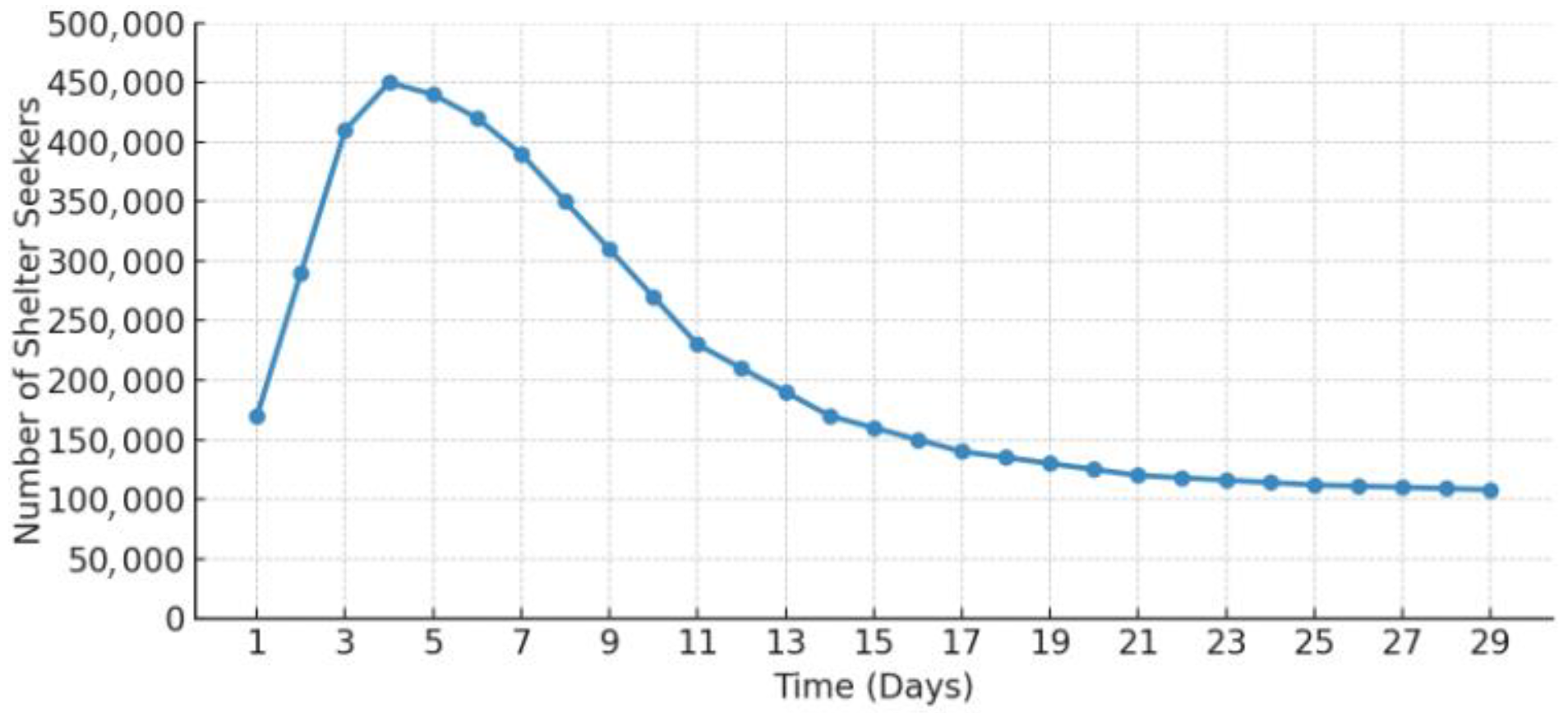

Based on the above methodology, the evacuation demand in Jinniu District under the assumed earthquake scenario was calculated for different days, and the results are plotted as curves in

Figure 4. The results show that the number of evacuees increases rapidly in the first few days after the earthquake, reaching a peak around day 4, when approximately 400,000 people—about 32% of the permanent population—require emergency shelter. Thereafter, as rescue operations proceed and basic infrastructure is gradually restored, some evacuees begin to return home and the number in shelters steadily decreases. By about two weeks after the earthquake, the number of people remaining in emergency shelters is significantly reduced.

This dynamic trend differs notably from traditional static estimates. For example, certain planning standards simply assume that 30% of the permanent population will require long-term shelter after a disaster. For Jinniu District, with a population of 1.28 million, this would correspond to about 384,000 evacuees. This figure is quite close—within 5–10%—to the peak of approximately 400,000 predicted by this model. However, when the temporal dimension and human factors are considered, the distribution of evacuees on different days differs significantly from models that only account for housing damage, with discrepancies exceeding 45% at some times. For instance, if large numbers of residents surge into shelters on the second or third day due to infrastructure failures, models based solely on building collapse will severely underestimate actual shelter demand. These findings demonstrate that including factors such as water and power supply disruptions is essential for accurately assessing both the peak of and temporal variation in evacuation demand.

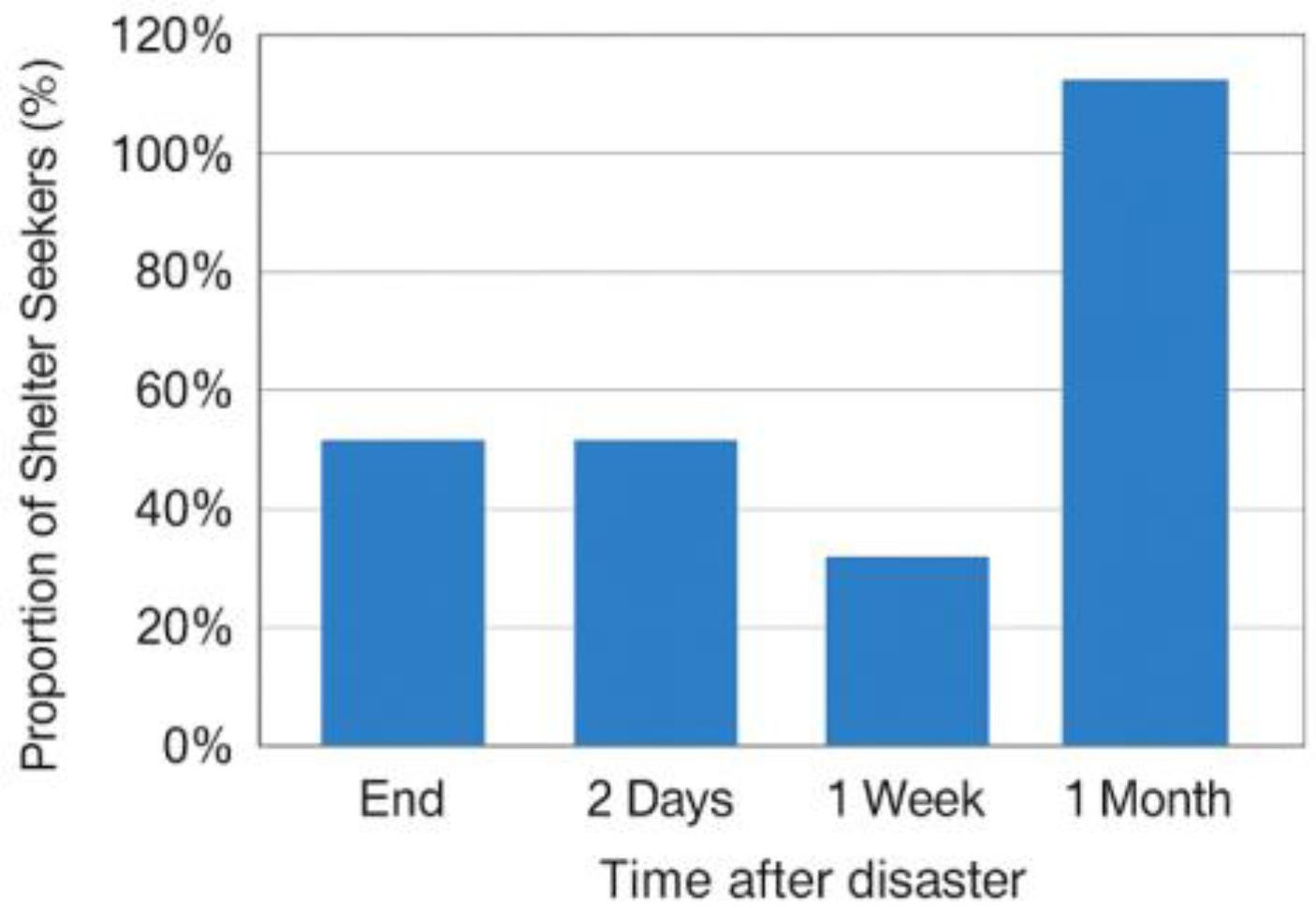

To further analyze the variation in the proportion of evacuees by cause,

Figure 5 presents the curve showing the share of evacuees whose need for shelter is directly due to building damage. The results indicate that, during the initial post-earthquake stage, a substantial proportion of shelter occupants are those affected by infrastructure disruptions, especially water outages, while the proportion of people rendered homeless by building collapse is relatively low. As time progresses and water and electricity services are gradually restored, residents whose homes are undamaged begin to return, leading to a steady increase in the proportion of evacuees who remain in shelters because their homes are uninhabitable.

Simulation results show that about one week after the earthquake, the share of evacuees caused by building damage can rise to over 50%. This trend highlights the importance of considering human behavioral factors: in the early aftermath, the pace of infrastructure restoration is crucial to alleviating pressure on emergency shelters, while in the later stages, the primary occupants of shelters are those whose homes remain uninhabitable.

In addition, this study assumes that a certain proportion of evacuees will choose to go to officially designated emergency shelters, while others may be accommodated elsewhere or seek refuge with relatives and friends. Drawing on Japanese post-disaster experience, it is generally observed that the number of people remaining in shelters one month after an earthquake is approximately 65% of those whose homes were completely destroyed. Referring to this empirical coefficient, this study assumes that φ = 65% of the total shelter demand will ultimately enter urban emergency shelters, while the remaining 35% will evacuate elsewhere.

Based on this assumption, the temporal variation in the number of evacuees entering emergency shelters is calculated and shown in

Figure 6. The results indicate that the number of shelter occupants also peaks on the fourth day after the earthquake, when about 33% of Jinniu District’s residents are housed in emergency shelters. This proportion then decreases daily, falling below 10% after about one month. Compared to the peak ratio of total evacuation demand, the proportion of residents actually entering shelters is slightly higher, as many residents unable to tolerate outages of water and electricity prefer to temporarily stay in public shelters. Overall, these results are consistent in magnitude with the conventional empirical estimate of 30%, demonstrating the reasonableness of the dynamic estimation method proposed in this study and providing a reliable basis for subsequent shelter site selection and allocation modeling.

4.2. Application of the Two-Stage Site Selection and Allocation Model

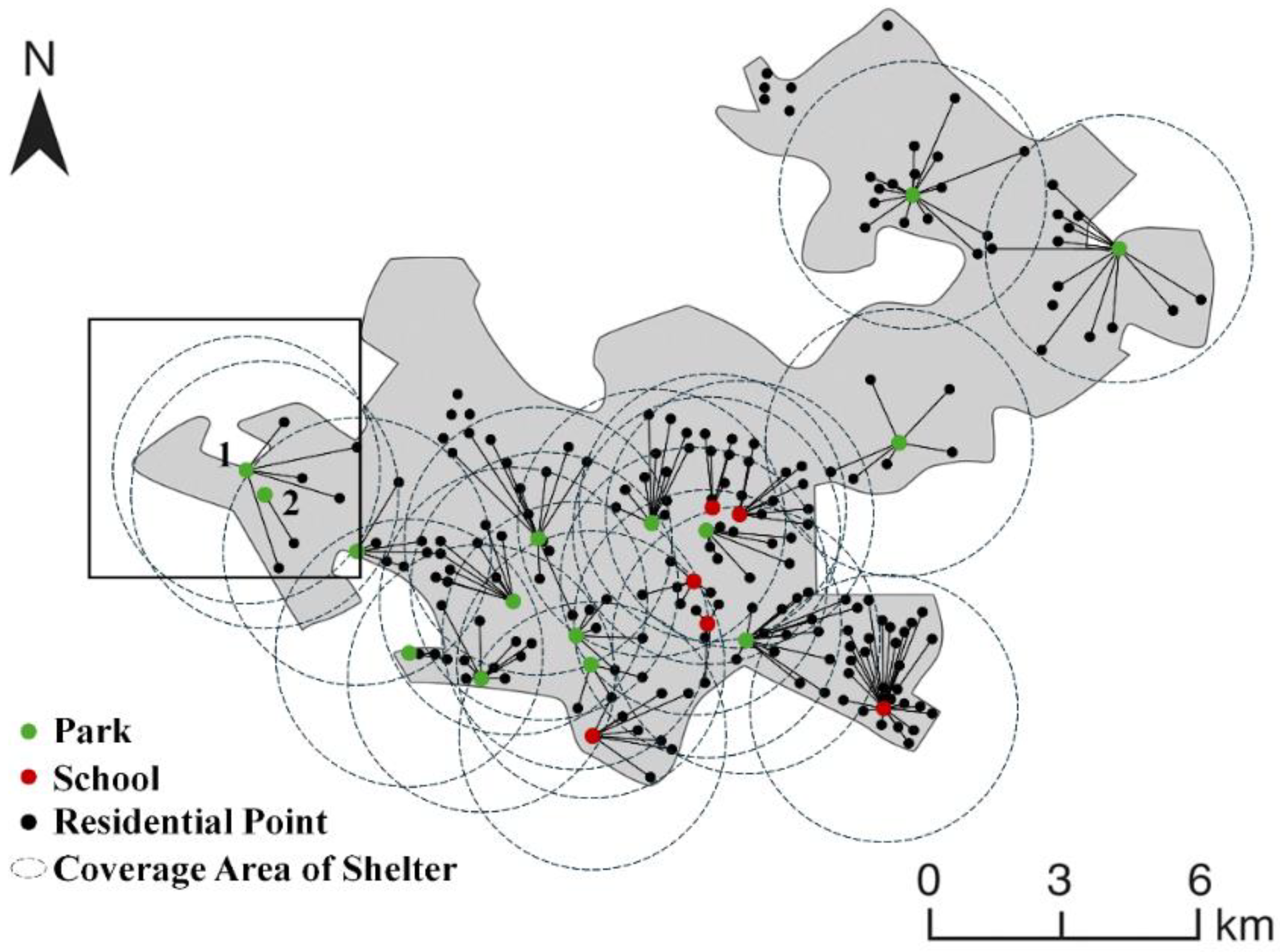

Based on the estimation of the time-varying evacuation demand in Jinniu District after an earthquake, the previously described two-stage location–allocation model was applied to emergency shelter planning for this area. Initially, 34 low-risk candidate evacuation sites, including parks and schools, were identified within Jinniu District using field surveys and GIS data. According to standards established by the China Earthquake Administration, the maximum service radius for evacuation shelters was set at 3 km. Capacity limits for each candidate site were determined based on their area and available facilities—for example, large parks could accommodate tens of thousands of people, while school playgrounds might hold several thousand—and estimated construction costs were assigned accordingly.

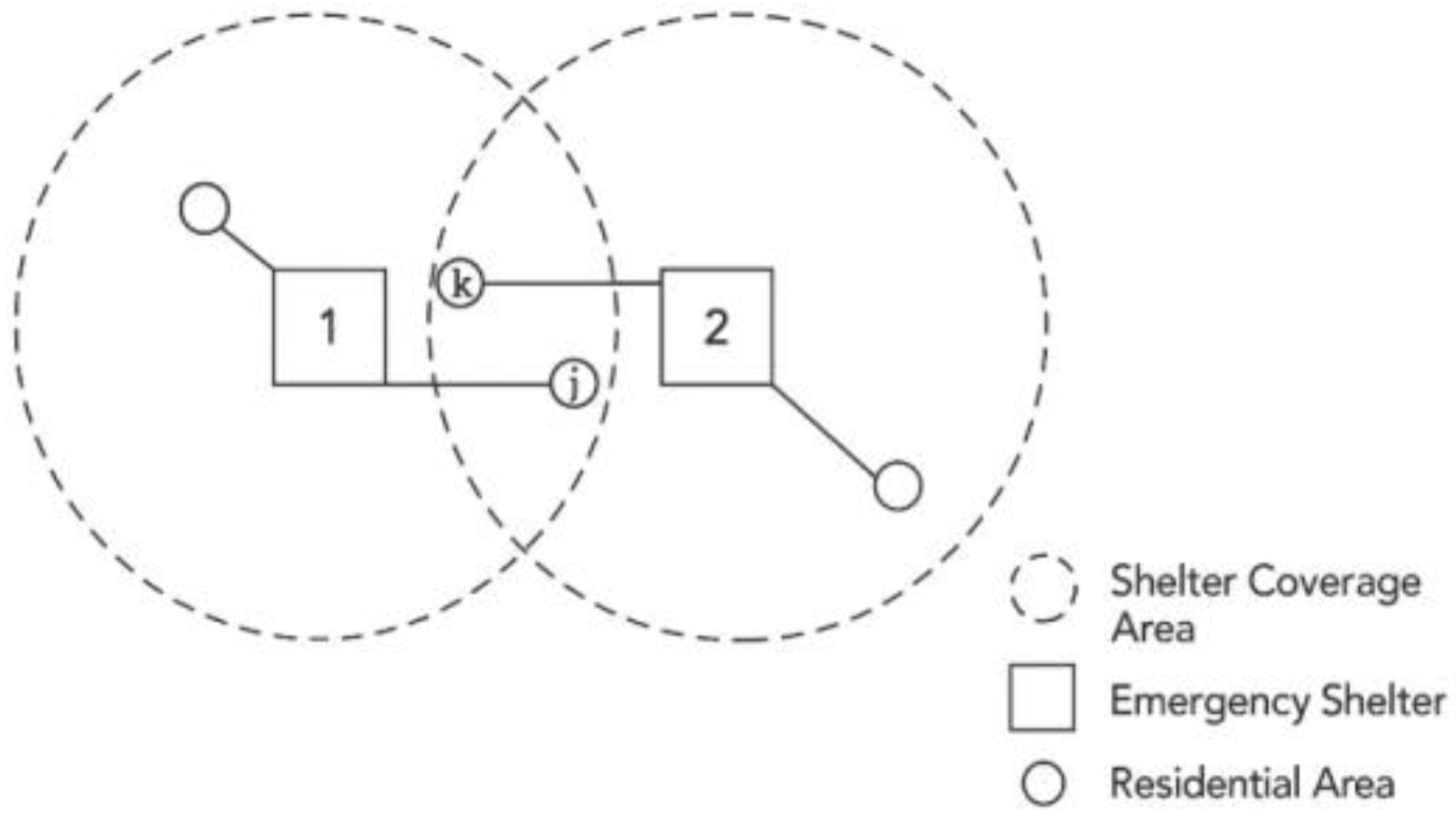

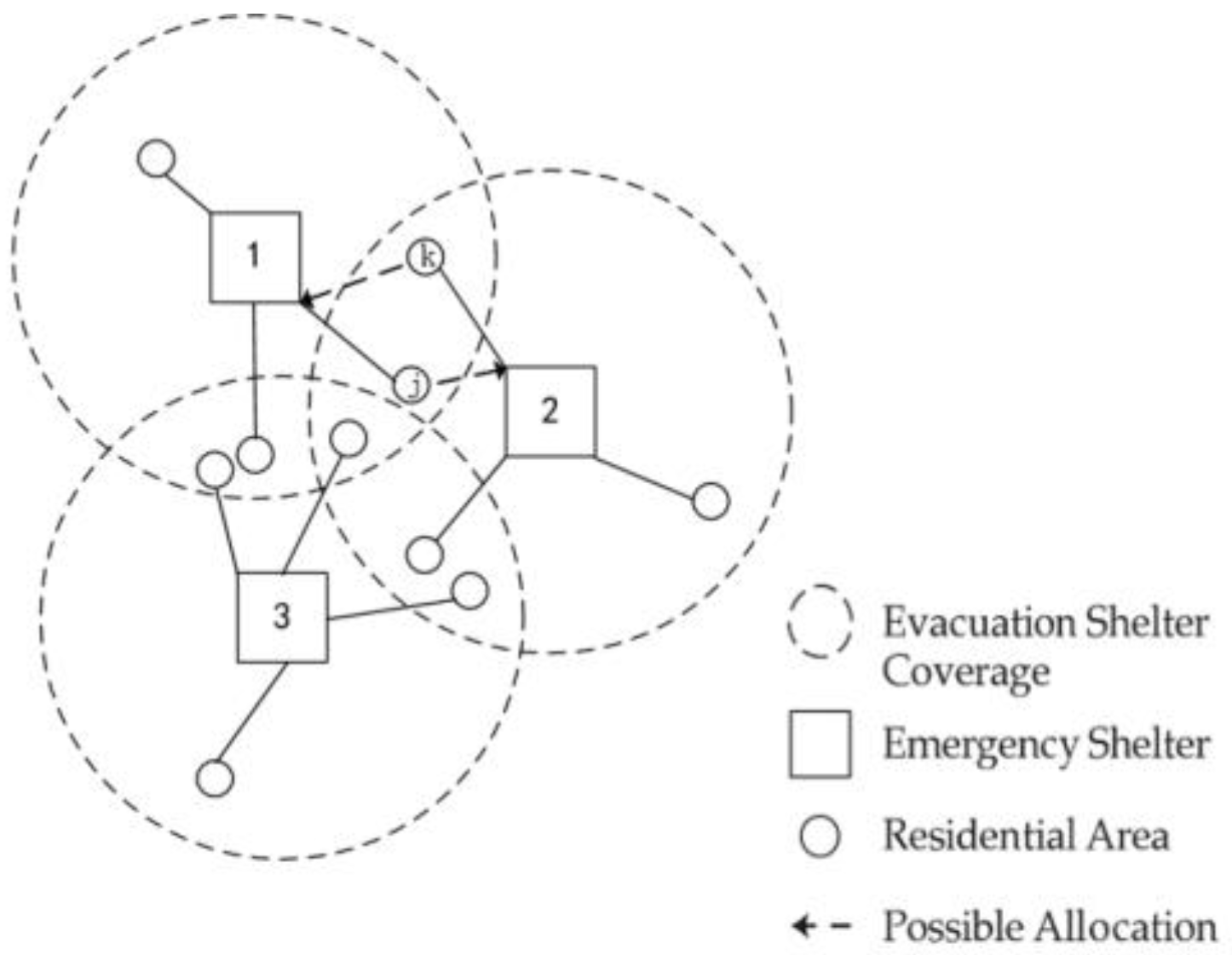

Figure 7 illustrates the spatial distribution of residential areas and candidate evacuation shelters in Jinniu District, including their respective 3-km service coverage zones. As shown in the figure, approximately 200 residential areas (communities/neighborhood committees) were identified as demand points within the district. Most residential areas fell within the service radius of at least one shelter; however, about 10 locations were found to be outside the coverage area of all candidate shelters. For these remote communities, evacuation plans should consider relocating residents to neighboring areas or potentially establishing additional temporary shelters in future planning efforts.

Based on the above data, an emergency shelter site selection and allocation optimization model was constructed. The first-stage decision of the model is to select which candidate shelters to open so as to accommodate the peak number of evacuees and satisfy coverage constraints. The objective is to minimize the total construction cost of shelters while ensuring that every residential site within the coverage area has at least one open shelter available, and that the number of people served by each shelter does not exceed its capacity limit. It should be noted that there may be a conflict between cost and distance objectives: a solution that purely minimizes construction cost may require some residents to travel relatively long distances to reach a shelter.

Figure 8 presents an illustrative example: in the initial site selection plan, residential area j is assigned to Shelter 1, even though Shelter 2 is actually closer to that community. This indicates that a cost-prioritized site selection result does not necessarily achieve optimal evacuation distance.

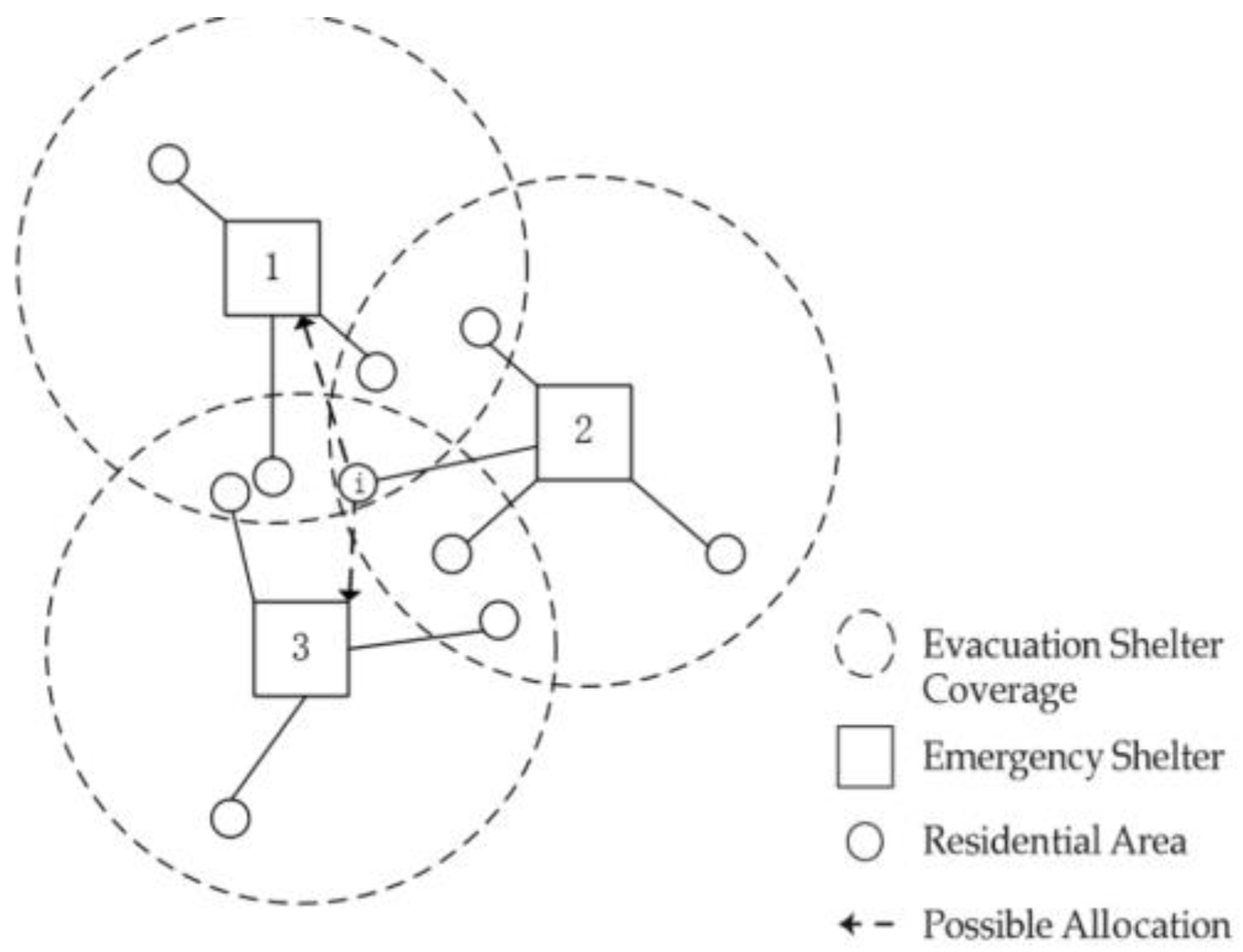

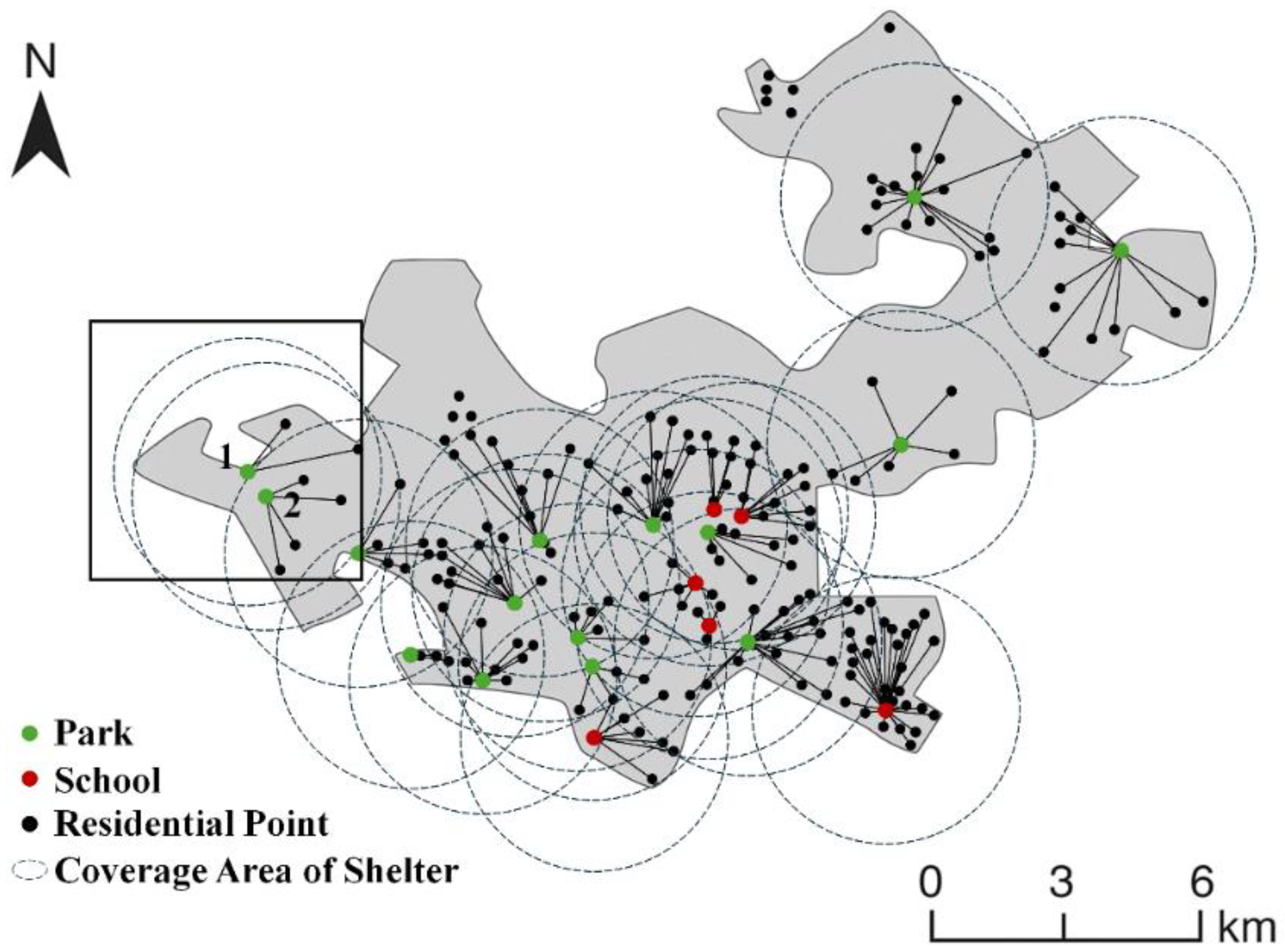

To overcome the above limitations, this study employs the PNLS algorithm to optimize shelter location and allocation. The algorithm consists of two main stages: first, robust site selection identifies which shelters to activate, improving adaptability to uncertain demand. Second, with the shelter locations fixed, evacuee reallocation optimizes total evacuation distance using a heuristic local search. Two neighborhood operations are defined: (1) “Insertion,” which reallocates a residential area to another activated shelter (see

Figure 9), and (2) “Swap,” which exchanges the assignments of two residential areas to improve evacuation efficiency (see

Figure 10). By repeatedly applying these operations, the algorithm reduces mismatches and total evacuation distance. When shelter capacity is exceeded, swap operations help redistribute evacuees to shelters with spare capacity, resolving allocation violations. Through iterative local search, the PNLS algorithm balances cost and evacuation distance, reaching near-optimal solutions efficiently. The algorithm’s search strategies and parameters are also adaptable to different problem scales and characteristics.

The location–allocation model and PNLS algorithm described above were applied to optimize the emergency shelter planning in Jinniu District. Under the baseline scenario, which was based on the previously estimated peak evacuation demand of approximately 400,000 residents, 21 candidate evacuation shelters were selected for activation, with a total estimated construction cost of approximately USD 1.89 million. Most selected shelters were large parks or schools with open spaces capable of accommodating over 90% of the evacuation demand in Jinniu District. Remaining demands were mainly addressed through coordinated arrangements in adjacent regions. Initially, the total evacuation distance calculated under this allocation plan was approximately 411,736 km.

Figure 11 presents the initial shelter location and residential allocation results calculated by the model. As indicated in the figure, some residential areas were not allocated to their nearest shelters. For instance, in the northwest area of the figure, multiple residential communities were grouped around Shelter 1, whereas a closer Shelter 2 served only one community. This outcome, similar to the scenario depicted in

Figure 8, illustrates that selection based purely on cost and coverage can lead to uneven service areas and locally suboptimal allocation results.

To address this issue, a second-stage reallocation optimization was performed using insertion and swap local search operations. Without adding new shelters, residential areas were reassigned to ensure more evacuees could reach closer shelters. After a few minutes of computation, the optimized results showed a significant reduction in the total evacuation distance, down to approximately 361,200 km, marking a decrease of over 12% from the initial solution. This greatly improved evacuation efficiency.

Figure 12 illustrates the optimized allocation between residential areas and shelters. Compared with

Figure 11,

Figure 12 clearly shows shorter and fewer connecting lines, indicating that more residential points were reassigned to closer shelters. For example, in the aforementioned northwest area, some residents initially assigned to Shelter 1 were reassigned to the adjacent Shelter 2. This new allocation improved the utilization of Shelter 2 and significantly reduced walking distances, achieving a mutually beneficial allocation scenario without additional cost, thereby enhancing evacuation efficiency and reducing evacuation risks.

Using Chengdu’s Jinniu District as a case study, this research illustrates the model’s practical application through parameterization and computational analysis. Since seismic resilience varies by city, the model’s parameters should be adjusted accordingly: cities with lower resilience require more emergency shelters due to higher evacuation demand, while those with higher resilience see more residents sheltering at home, leading to lower demand. Regardless, timely access to rescue information and support is critical. This study applies a continuously varying demand estimation method to analyze parameter sensitivity across different urban scenarios, capturing the dynamic nature of evacuation needs. Overall, the proposed two-stage location–allocation model offers valuable theoretical and practical guidance for optimizing shelter siting, minimizing costs, and enhancing disaster response.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a robust two-stage location–allocation model for urban emergency shelters, addressing the challenges of uncertain demand, evacuation efficiency, and social equity in disaster response as key dimensions of urban sustainability. The model integrates pre-disaster robust site selection with post-disaster multi-objective allocation, ensuring that shelters are adequately prepared for worst-case scenarios while minimizing evacuation distances and maximizing social resilience. By linking shelter provision to equity and long-term capacity planning, the framework supports more sustainable use of urban land and infrastructure and strengthens the continuity of essential public services before, during, and after earthquakes. The customized Phased Nested Local Search (PNLS) heuristic effectively solved the complex NP-hard problem, delivering near-optimal solutions with significantly reduced computation times compared to exact solvers. This study highlights the importance of integrating social considerations with technical solutions to improve urban disaster preparedness, offering a more holistic and sustainability-oriented approach to risk management.

(1) The proposed model demonstrated significant improvements in emergency shelter planning outcomes. In the case study of Jinniu District, dynamic demand estimation accurately captured the time-varying surge in evacuees, with approximately 400,000 people requiring shelter at the peak, closely matching empirical data. By selecting 21 shelters, the model met peak demand while minimizing construction costs, providing a practical approach to emergency shelter planning.

(2) The post-disaster reallocation optimization significantly enhanced evacuation efficiency. The study achieved a reduction of over 12% in the total evacuation distance, improving both evacuation efficiency and spatial equity. This optimization was realized without the need for additional shelter construction, thus providing a cost-effective solution to enhance evacuation outcomes in urban areas facing disaster risks.

(3) The two-stage model offers practical guidance for urban planners to optimize shelter locations and minimize risks during disasters. The adaptability of the model allows it to be applied in different cities by calibrating the demand model to local conditions and infrastructure resilience. Future research could enhance the model by integrating real-time data and considering additional behavioral factors, further refining dynamic evacuation planning strategies.

From a policy perspective, the results of the Chengdu case study—particularly the 12.3% reduction in total evacuation distance and 15.8% decrease in high-quantile travel burden—demonstrate that the proposed framework can directly support municipal emergency planning and be adapted to other urban contexts through parameter calibration. When applied to different cities, parameter adjustments should reflect local characteristics such as population density, infrastructure resilience, and behavioral patterns. Key parameters include the population exposure coefficient (derived from residential density and household size statistics), the infrastructure disruption coefficient (representing the expected duration and spatial extent of service interruptions in power, water, and transport systems), and the behavioral adaptation coefficient (capturing local evacuation tendencies and shelter preferences based on past events or survey data). Calibration can be achieved using statistical yearbooks, seismic zoning maps, and municipal infrastructure datasets. In practice, cities with high population density and lower infrastructure resilience require larger service coverage or higher shelter-to-population ratios, while those with stronger resilience and rapid recovery capacity can apply smaller scaling factors. The model’s outputs can then be integrated into existing GIS-based decision-support systems to visualize shelter accessibility, simulate evacuation scenarios, and prioritize resource allocation under different disaster intensities, enabling local governments to optimize shelter locations, refine evacuation routes, and enhance urban resilience within an evidence-based planning framework that supports long-term urban sustainability goals.