1. Introduction

Plastics, as a revolutionary class of materials, have profoundly reshaped human society, particularly in the food packaging sector. Their light weight, low cost, and excellent barrier properties have led to their widespread application [

1]. This convenience, however, has come at a significant environmental cost. Globally, over 350 million tons of plastic waste are generated annually, with packaging waste accounting for nearly 40% of the total [

2]. The majority of these petroleum-derived plastics are non-biodegradable, leading to long-term environmental contamination, notably “white pollution,” which poses a severe threat to terrestrial and marine ecosystems and enters the food chain as microplastics, ultimately impacting human health [

3,

4]. Concurrently, approximately one-third of the food produced for human consumption is wasted each year, amounting to about 1.3 billion tons of food waste [

5]. This not only exacerbates the environmental burden but also results in substantial economic losses. Therefore, developing sustainable packaging alternatives and achieving the valorization of waste have become critical tasks for both academia and industry worldwide.

To address these challenges, academia and industry are actively promoting a transition from the traditional “take-make-dispose” linear economic model to a circular economy [

6]. The core principle of the circular economy is to maximize resource utilization while minimizing waste generation. In this context, abundant resources such as agricultural, food, and animal processing wastes are being redefined as valuable biomass repositories rather than mere burdens [

7]. These wastes are rich in natural polymers, including proteins (e.g., collagen, keratin, soy protein), polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, chitosan), and lipids, making them ideal precursors for constructing bio-based materials [

8]. Converting these wastes into biodegradable packaging materials not only reduces our dependence on fossil resources but also effectively mitigates environmental pollution, aligning with the core principles of the circular economy and waste valorization.

Biodegradable packaging films are materials that can be completely decomposed by microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi) into natural substances such as carbon dioxide, water, and biomass under specific environmental conditions (e.g., soil, compost) [

9]. Compared to conventional plastics, these films offer distinct advantages. Firstly, their biodegradability and biocompatibility allow them to return to natural cycles harmlessly after disposal, preventing long-term pollution. Secondly, their renewability contributes to a lower carbon footprint. More importantly, by integrating natural active compounds from waste or through functional design, these films can exhibit antimicrobial, antioxidant, and even smart-responsive properties (e.g., responding to pH/temperature changes or indicating food freshness) [

10,

11]. For instance, anthocyanins extracted from fruit and vegetable peels can serve not only as natural colorants but also as pH indicators, visually signaling the spoilage of packaged food through color changes [

12].

Although the development of biodegradable packaging films from waste biomass has become a significant research area with a substantial body of literature, a systematic and integrated knowledge framework remains notably absent. Our review offers three distinctive advances over existing works. First, unlike reviews focused on single waste streams [

9,

13], we provide integrated comparative analysis across agricultural, food, and animal-derived wastes, revealing cross-stream synergies for material optimization. Second, while recent bibliometric studies map publication trends, we uniquely connect these quantitative patterns to the entire value chain, from raw material extraction and film fabrication to performance characteristics and practical applications. Third, our extended coverage through early 2025 identifies emerging research frontiers in real time, particularly the intensifying focus on nanocellulose and the strategic gap in smart packaging implementation. To bridge these gaps, this review aims to construct a more comprehensive and empirically supported analytical framework (

Figure 1). We will first employ bibliometric analysis to map the overall knowledge structure and developmental dynamics of the field. Subsequently, we will conduct an in-depth exploration of the entire technological chain, from the extraction of raw materials and fabrication of bio-based materials to the performance evaluation and application of packaging films. Finally, based on this analysis, we will critically review the key challenges and relevant regulations, and propose a systematic outlook for future research directions.

2. Bibliometric Analysis: Research Landscape and Evolutionary Trajectory

2.1. Bibliometric Methodology

The bibliometric analysis was conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection, covering publications from 2008 to 2025. The search string employed was: ((((((TS = (film OR package)) AND TS = (waste)) AND TS = (fresh*)) AND TS = (food OR meat OR fruit)) NOT TS = (plastic*)) NOT TS = (poly*)), which yielded 413 documents. After excluding Editorial Materials (n = 1), Early Access articles (n = 7), Proceeding Papers (n = 16), and Non-English publications (n = 2), a final dataset of 387 documents (318 research articles and 69 reviews) was retained for analysis. Network visualization and keyword co-occurrence analysis were performed using VOSviewer (version 1.6.19), while temporal trends were analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

2.2. From Incubation to Prominence: The Field’s Maturation Pathway

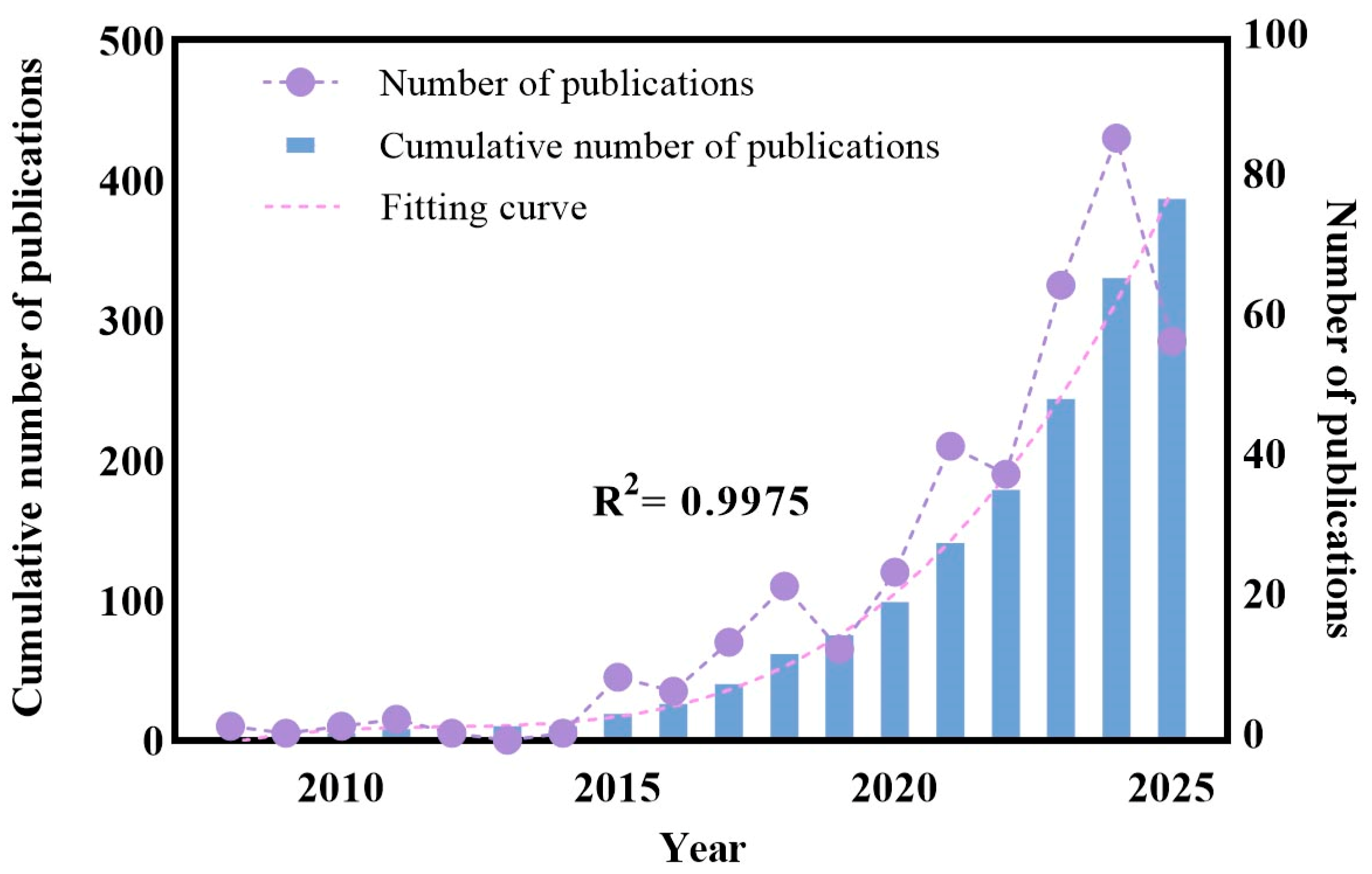

Over the past two decades, the academic inquiry into sustainable food packaging has matured from a nascent, peripheral topic into a vibrant and critical frontier in sustainability science. A bibliometric analysis of its developmental timeline reveals three distinct phases of evolution (

Figure 2). The initial incubation period (2008–2014) was characterized by sparse and exploratory research, indicating a formative stage where foundational concepts were being forged. A pivotal turning point occurred in 2015, marking the onset of an acceleration phase (2015–2019), during which scholarly output began to grow exponentially. This surge signified the consolidation of the field’s core research questions and its broad recognition as a viable solution to pressing global challenges.

Most notably, the period since 2020 represents an explosive growth phase, with literature produced in the last three years alone constituting over half of the entire corpus. This recent scholarly boom is not merely a quantitative increase; it reflects the field’s escalating strategic importance amidst intensified global imperatives related to food security, resource depletion, and the circular economy agenda [

9,

12,

13]. The sustained, near-exponential growth trend strongly indicates that this field has solidified its status as a key area of international research, having achieved the critical mass required for continued expansion and profound impact.

2.3. The Global Research Landscape: Collaborative Dynamics and Knowledge Flow

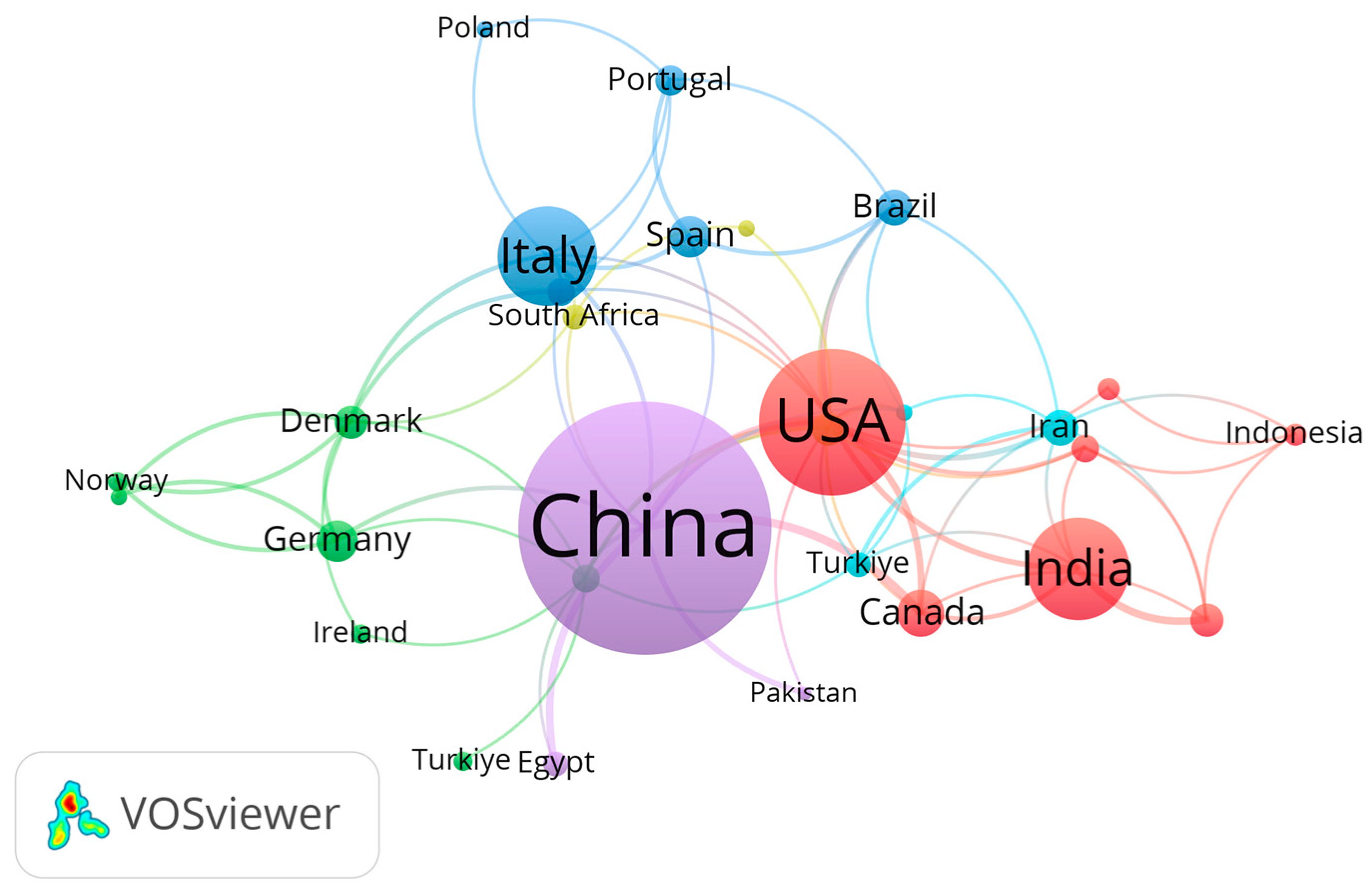

The global research architecture is characterized by a dominant bipolar network led by China and the United States (

Figure 3). These two nations not only lead in research productivity but also form the central axis of international collaboration, acting as the primary engine for global innovation and agenda-setting. A significant feature of this network is a pattern of knowledge transfer from this core to developing nations, including India, Egypt, and Pakistan. This network visualizes the collaborations among the top 10 most productive countries, as quantified in

Table 1. This core–periphery dynamic facilitates the adaptation of advanced technological solutions to address urgent regional sustainability challenges, such as post-harvest food loss and waste reduction, thereby directly contributing to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (e.g., SDG 2, Zero Hunger, and SDG 12, Responsible Consumption and Production).

In parallel, distinct regional innovation ecosystems have emerged within Europe, notably a Northern European cluster centered around Denmark and a Southern European hub involving Italy and Spain. These sub-networks highlight the role of regional funding and policy priorities in shaping research directions. However, the relative insularity of several scientifically active nations reveals a persistent imbalance in global scientific collaboration, presenting a barrier to the inclusive and equitable advancement of sustainable solutions worldwide [

14].

2.4. Thematic Evolution: An Intellectual Deepening from ‘Why’ to ‘How’

The field’s intellectual trajectory reveals a clear and logical progression from macro-level problem assessment (‘why’ alternatives are needed) to micro-level material innovation (‘how’ to create them), reflecting a deepening engagement with sustainability principles [

15,

16].

Initially, the research was firmly anchored in a systems-level environmental perspective. Keywords such as “life cycle assessment (LCA)” and “carbon dioxide emission” functioned as foundational pillars of the knowledge network (

Table 2), indicating that from its inception, the field was driven by the imperative to quantify and mitigate environmental burdens. This early focus established the systemic context and validated the environmental rationale for developing novel technologies.

Table 2.

Top 10 High-Frequency and Burst Keywords in the Research on Waste-Derived Biodegradable Films.

Table 2.

Top 10 High-Frequency and Burst Keywords in the Research on Waste-Derived Biodegradable Films.

| High Frequency Keywords | Frequency | Centrality | Bust Keywords | Year | Strength | Begin | End | 2008–2025 |

|---|

| shelf-life | 66 | 0.71 | life cycle assessment (lca) | 2010 | 4.37 | 2010 | 2021 | ▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂ |

| quality | 61 | 0.23 | carbon dioxide emission | 2011 | 3.45 | 2011 | 2018 | ▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| films | 58 | 0.17 | systems | 2011 | 3.25 | 2011 | 2019 | ▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| chitosan | 55 | 0.34 | food waste | 2008 | 7.09 | 2018 | 2022 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂ |

| food waste | 42 | 0.42 | carbon footprint | 2018 | 2.54 | 2018 | 2019 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| antioxidants | 41 | 0.26 | quality | 2019 | 2.67 | 2019 | 2022 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▂▂▂ |

| waste | 32 | 0.04 | waste | 2017 | 2.84 | 2021 | 2022 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂ |

| anthocyanins | 26 | 0.01 | shelf-life | 2015 | 4.7 | 2022 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂ |

| essential oils | 24 | 0.38 | storage | 2015 | 2.11 | 2022 | 2023 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂ |

| edible films | 24 | 0 | cellulose | 2023 | 3.62 | 2023 | 2025 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃ |

Subsequently, the research agenda pivoted towards a more solution-oriented paradigm, bridging environmental concerns with practical applications. The concurrent emergence of “food waste” and “quality” as major research hotspots signifies this critical shift. This demonstrates that the academic community moved from merely diagnosing the problem to actively developing interventions that directly address food loss while maintaining product integrity. Maximizing “shelf life” became the absolute core of the field’s technological pursuits, connecting material science with tangible sustainability outcomes. This phase is dominated by research into bio-based solutions, with materials like “chitosan” and active agents such as “essential oils” forming the mainstream technological pathway (

Figure 4). The sophistication of the knowledge structure is exemplified by bridging nodes like “antioxidants,” which connect technical performance metrics (e.g., “storage”) with overarching sustainability goals (“sustainable development”), illustrating a mature, integrative research approach.

2.5. Emerging Frontiers and Strategic Gaps

Based on this analysis, the future trajectory of the field is projected to advance along several key frontiers, while also revealing critical strategic gaps that require attention.

The most prominent emerging frontier is the pursuit of next-generation, high-performance biomaterials. The recent and intense focus on “cellulose,” particularly at the nanoscale, signals a new wave of innovation. Future research will likely concentrate on engineering advanced bio-composites that are not only biodegradable and renewably sourced but also offer superior barrier properties, mechanical strength, and tunable functionalities. This represents a move towards materials that are sustainable by design and can compete with, or even outperform, conventional petroleum-based plastics. Recent work on advanced, functional cellulose-based membranes with controlled properties provides a clear example of this emerging innovation wave [

17].

Conversely, a significant strategic gap lies in the domain of “smart and intelligent packaging.” Despite its conceptual appeal, this topic remains on the periphery of the core research network, indicating that its potential is largely untapped. Integrating sensor technologies and data carriers into sustainable packaging materials could revolutionize supply chain management, provide consumers with real-time quality information, and further reduce food waste. Future work should focus on integrating these smart functionalities into the bio-based material platforms that currently dominate the field [

18].

This multi-level focus will ensure that the solutions developed are not only scientifically novel but also practically effective and truly sustainable. Importantly, our integrated approach—comparing waste streams, linking bibliometric trends with technical development, and tracking temporal evolution—provides a systematic framework that addresses the fragmentation and methodological limitations identified in existing literature.

2.6. Bridging Bibliometric Insights with Technological Pathways

The bibliometric analysis presented above reveals critical patterns that directly inform the technological review in subsequent sections. A clear correspondence exists between keyword clusters and the technological chain from waste valorization to functional films.

The early dominance of “life cycle assessment” and “carbon dioxide emission” keywords (

Table 2) established the environmental rationale that underpins waste feedstock selection (

Section 3). The explosive growth of “food waste” and “cellulose” as burst keywords since 2018 and 2023, respectively, directly corresponds to intensified research on agricultural and food industry waste streams and nanocellulose extraction technologies (

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2 and

Section 4.3). The persistent centrality of “chitosan” in the co-occurrence network (

Figure 4) reflects its dual role as both a waste-derived material from crustacean shells (

Section 3.3) and a versatile film-forming matrix (

Section 5 and

Section 6).

Furthermore, the recent emergence of “shelf-life,” “antioxidants,” and “anthocyanins” as high-frequency keywords signals the field’s strategic pivot toward functional packaging, which is comprehensively addressed in

Section 6.5 and

Section 7. The relative peripherality of “smart packaging” in the network (

Section 2.5) highlights an underexplored frontier that is critically examined in

Section 8.4’s future prospects.

This synthesis demonstrates that the bibliometric landscape is not merely descriptive but predictive of technological priorities, guiding our structured exploration of the complete value chain in the following sections.

3. Waste Feedstocks: Sources, Classification, and Composition

The keyword burst analysis (

Table 2) reveals that “food waste” exhibited the strongest citation burst (strength = 7.09) from 2018–2022, while “cellulose” emerged as the most recent frontier (2023–2025, strength = 3.62). These patterns directly reflect the field’s evolution in feedstock prioritization, as detailed below.

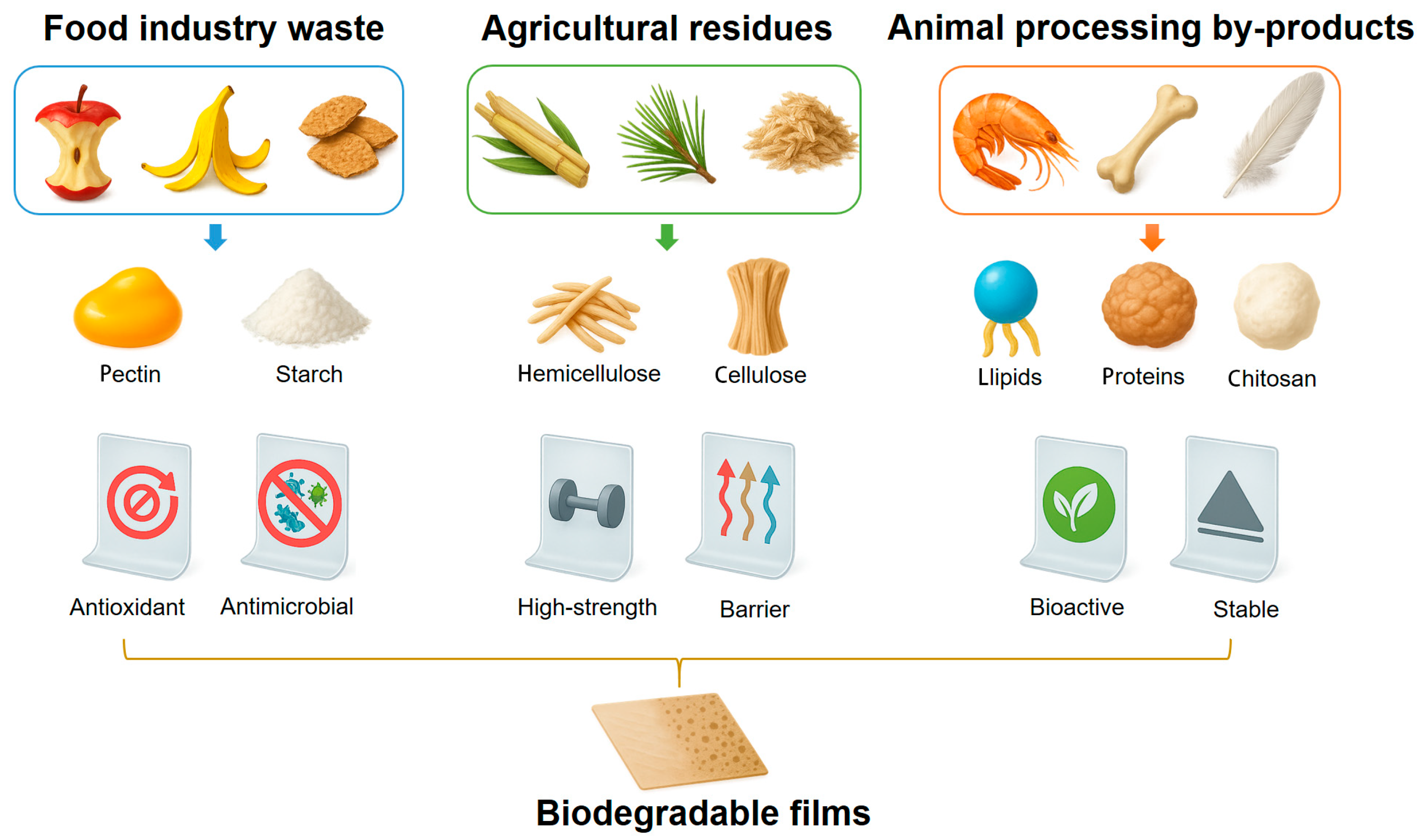

The performance of biodegradable packaging films is fundamentally determined by the characteristics of their raw materials. During production, the chemical composition and molecular structure of waste biomass directly influence the film’s final properties and processing feasibility. Natural polymers (polysaccharides, proteins, lipids) extracted from different waste sources vary markedly in type, content, purity, and structural characteristics. These differences determine their suitability and functional role in film production—whether as the primary structural matrix, reinforcing fillers, or functional additives.

In the context of waste-derived biopolymers, purity refers to the proportion of the target polymer (e.g., cellulose, protein, pectin) relative to contaminants such as residual lignin, ash, lipids, pigments, or other non-target biomolecules in the extracted material. For instance, cellulose extracted from agricultural straw may contain 5–20% residual lignin and hemicellulose, while protein isolates from food waste may retain 2–10% lipids and minerals. Higher purity typically yields more predictable film-forming behavior, improved mechanical properties, better optical transparency, and enhanced barrier performance. Conversely, low purity can cause processing difficulties (e.g., poor solubility, gel formation), structural defects, discoloration, and batch-to-batch variability, all of which compromise efficiency and quality. Therefore, scaling up production requires optimizing extraction protocols to achieve appropriate purity levels while balancing cost and environmental impact.

From a material production perspective, systematic characterization of waste feedstocks is essential for rational design and efficient manufacturing. The chemical profile of the waste stream constrains all subsequent processing decisions: extraction methods, film fabrication techniques, and modification strategies must be tailored to the specific composition of the feedstock. As illustrated in

Figure 5, a clear hierarchical relationship links the source and composition of the waste to the processing pathway and the final performance of the film.

3.1. Agricultural Wastes

Agricultural wastes, also known as agro-industrial residues, represent one of the most abundant and accessible renewable resources globally. This category primarily includes post-harvest crop residues, by-products from fruit and vegetable processing, and nutshells. Crop straws (e.g., rice, wheat, corn stover), rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, are a primary source for extracting nanocellulose, which is frequently used to engineer reinforced composite films. Research has demonstrated that nanocellulose derived from these biomass sources exhibits excellent mechanical strength and film-forming capabilities, showing great promise for food packaging applications [

19]. Furthermore, fruit and vegetable pomaces (e.g., apple pomace, grape skins, potato peels), valued for their high content of pectin, polyphenols, and dietary fiber, are widely exploited for fabricating functional films. For instance, the vast quantities of potato peels and starch residues generated during processing have been successfully converted into edible films with notable preservative and antimicrobial properties using green processing technologies [

20]. Lignin-rich wastes like nutshells and coffee silverskin can also serve as sources for cellulose nanocrystals or be used directly as reinforcing fillers to enhance the thermal stability and mechanical properties of film materials [

21].

3.2. Food Industry Wastes

The food industry generates substantial volumes of by-products during processing, storage, and consumption, which often retain high nutritional and functional value, particularly in their protein, polysaccharide, and polyphenol content. Globally, the food processing industry produces approximately 1.3 billion tons of waste annually, with fruit and vegetable processing alone accounting for over 500 million tons. In the European Union, food waste from manufacturing represents roughly 17% of total food waste, equivalent to about 16.9 million tons per year [

22]. This massive waste stream, when properly valorized, represents a significant opportunity for sustainable material development.

Cereal processing by-products such as wheat bran, rice bran, and okara (soybean pulp) are rich in plant proteins and cellulose, making them ideal substrates for biodegradable films. Okara, for instance, is produced at a rate of approximately 1.1 kg per kilogram of soybeans processed for tofu or soymilk production, resulting in over 14 million tons of okara waste globally each year [

23]. Due to its high protein and insoluble fiber content, has been extensively investigated in recent years for creating edible and active packaging films [

24].

Recent advances in composite material development have shown promising results in utilizing diverse food processing residues. Research on biocomposites produced with thermoplastic starch and digestate has demonstrated that these materials can exhibit mechanical properties comparable to conventional plastics, with tensile strengths ranging from 5–15 MPa, while offering complete biodegradability [

25]. Similarly, biocomposites fabricated from rapeseed meal, fruit pomace, and microcrystalline cellulose through press-pressing techniques have shown excellent structural integrity and barrier properties, achieving water vapor permeability values as low as 2.5 × 10

−10 g·m

−1·s

−1·Pa

−1, which is competitive with some synthetic polymers [

26]. These studies highlight the technical feasibility of converting multi-source food waste streams into high-performance packaging materials.

Residues from the beverage industry, including brewers’ spent grain (20–25 million tons annually worldwide) and tea and coffee processing wastes (over 8 million tons annually), are also research hotspots. These materials typically contain residual amounts of polysaccharides, proteins, and polyphenolic compounds with antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, rendering them suitable for developing packaging with active-release capabilities [

24]. For example, spent coffee grounds contain 8–18% residual lipids that can be extracted for barrier coatings, while their lignocellulosic fraction can yield nanocellulose for mechanical reinforcement [

27].

In addition, vast quantities of fruits and vegetables (approximately 100–150 million tons globally) discarded due to cosmetic imperfections or over-ripeness serve as important sources of bioactive pigments like lycopene, carotenes, and betalains, which have been successfully incorporated into smart packaging materials to provide colorimetric indication and antioxidant functions [

28]. Tomato processing waste alone, generated at approximately 4–5 million tons per year worldwide, has been utilized to extract pectin (yield: 5–15%), lycopene (yield: 100–200 mg/kg), and cellulosic materials for film production [

29].

3.3. Animal Processing By-Products

While research into animal-derived by-products began more recently than that for plant-based wastes, their unique proteinaceous structures offer distinct and often irreplaceable advantages in film-forming properties. Gelatin and collagen, the primary components of animal tissues (e.g., skin, bones, connective tissue), are widely used to produce edible and composite films owing to their excellent film-forming ability, biocompatibility, and oxygen barrier capacity [

30]. Keratin, the main protein in feathers, wool, and other epidermal structures, is rich in sulfur-containing amino acids. Following hydrolysis via physical or chemical methods, keratin can be regenerated into film materials with good mechanical properties and biodegradability, showing broad prospects in both biomedical and packaging applications [

31]. Myofibrillar proteins from the meat industry have also been shown to possess good emulsifying and film-forming properties, capable of enhancing the mechanical strength and gas barrier performance of packaging films [

32]. Chitosan, derived from the shells of crustaceans like shrimp and crabs, is a cornerstone material in active packaging research due to its intrinsic antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities. Composites of chitosan with other biopolymers can further enhance film performance [

33].

3.4. Regional Distribution and Resource Accessibility

The type and volume of available waste are significantly influenced by regional industrial structures, agricultural practices, and climatic conditions. Europe, for example, generates large quantities of sugar beet pulp and cereal straw from its extensive cultivation of these crops, making them priority targets under the EU’s bioeconomy strategy [

34]. In contrast, Asian regions, particularly China and India, possess abundant rice husk and straw resources. Meanwhile, North and South America have vast supplies of corn stover and soybean by-products, constituting the basis for the spatial heterogeneity of global agricultural by-products resources [

35]. This geographical distribution is a critical factor for developing scalable and economically viable supply chains.

Furthermore, many of these by-products, especially from fruit and vegetable processing plants which produce the bulk of this raw material, are also used as animal feed or natural fertilizers, setting them apart from typical waste and supporting circular economy models.

3.5. Compositional Analysis of Wastes

The chemical composition of waste directly determines its application potential in biodegradable packaging films. The compositional data, summarized in

Table 3, reveal distinct functional roles for each waste category, enabling the targeted design of packaging materials with enhanced structural integrity or added functionality.

As highlighted in the table, agricultural wastes are predominantly valued as sources of structural polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. These components make them excellent reinforcing materials capable of enhancing the mechanical strength of films. For example, the cellulose and hemicellulose abundant in wheat straw are commonly extracted to produce nanocellulose-reinforced films [

40]. In contrast, food industry wastes, particularly fruit pomaces and soybean residues, are rich reservoirs of bioactive substances such as pectin, proteins, phenolic compounds, and natural pigments. These components can serve not only as film-forming matrices but also as sources for active ingredients to develop packaging with antioxidant, antimicrobial, or smart-responsive functionalities [

38,

41]. Apple pomace, for instance, provides pectin as a film matrix and phenolic compounds as active additives [

37].

Finally, animal by-products are distinguished by their high content of quality proteins, which are extensively utilized in film fabrication. Proteins like gelatin and chitosan exhibit outstanding film-forming properties and biocompatibility. Shrimp shells and bovine hides, as representative animal wastes, are rich in chitin and collagen, respectively. These natural polymers are widely employed to create packaging films with superior antimicrobial and oxygen barrier properties [

39]. By strategically harnessing the intrinsic composition of these diverse waste streams, it is possible not only to mitigate their environmental burden but also to engineer multifunctional packaging films, thereby driving the development of the next generation of green packaging materials.

4. Extraction of Bio-Based Materials from Wastes

The successful conversion of waste from agriculture, the food industry, and animal processing into biodegradable packaging films is contingent upon the efficient and environmentally benign extraction of target macromolecules—namely, proteins, polysaccharides, and various bioactive compounds—from complex biomass matrices. The selection of an extraction technology is a critical control point, as it not only dictates the yield and purity of the extracted components but also profoundly influences their structural integrity, functional properties, and, ultimately, the economic viability and sustainability of the entire value chain.

4.1. Overview of Extraction Methodologies

Extraction technologies for target components from waste biomass can be broadly classified into conventional physical/chemical methods and emerging green extraction techniques. Conventional physical methods, such as ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and high-pressure processing, primarily disrupt cellular structures to facilitate the release of intracellular contents, offering advantages like reduced energy consumption and shorter processing times. The cavitation effect induced by ultrasound, in particular, significantly enhances mass transfer efficiency [

40]. Chemical methods rely on the selective solvency or hydrolytic action of reagents, such as the widespread use of acid/alkali hydrolysis to deconstruct lignocellulosic complexes or degrade proteins. However, these traditional methods are often associated with environmental pollution and solvent residue concerns, necessitating greener alternatives. In recent years, green technologies like supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), subcritical water extraction (SWE), and deep eutectic solvents (DESs) have gained prominence. SWE, in particular, is valued for its use of non-toxic, inexpensive water as a solvent and its ability to preserve thermally sensitive active compounds, demonstrating excellent results in extracting bioactive molecules from various biological wastes [

41]. This shift toward green technologies are directly evidenced in our bibliometric analysis, where “supercritical fluid extraction” and “subcritical water” appeared as emerging keywords in the 2020–2025 period, reflecting the field’s methodological maturation toward sustainable processes.

To provide a quantitative comparison of these approaches,

Table 4 summarizes the typical extraction yields, efficiencies, and key techno-economic considerations for major components from these waste streams. This analysis reveals a critical trade-off: while conventional chemical methods are often mature and achieve high yields (e.g., 39.4% cellulose from wheat straw [

1] or 58.3% protein recovery from okara [

42]), they typically involve high consumption of harsh chemicals and significant wastewater treatment costs. Conversely, emerging green technologies (e.g., UAE) promise lower processing times (e.g., 30 min for pectin extraction [

43]), but may be constrained by high capital equipment costs (for SFE [

44]) and challenges in industrial scalability. The selection of an optimal method is therefore a complex balance between yield, purity, cost, and environmental impact.

4.2. Extraction of Proteins and Lipids

Proteins, which serve as excellent film-forming matrices, are abundant in both animal by-products and plant residues. The conventional extraction of gelatin involves acid or alkaline hydrolysis of collagen. More recently, research has explored the use of enzymes like pepsin to achieve milder and more efficient protein extraction, yielding protein molecules with superior functional properties [

48]. For plant-based proteins, okara (soybean pulp) is a common feedstock from which soy protein isolate is typically extracted via an alkaline solubilization and isoelectric precipitation method. The resulting protein films exhibit good mechanical properties and film-forming capabilities [

42]. In lipid extraction, supercritical CO

2 extraction is a preferred green method for oil-rich wastes like spent coffee grounds and rice bran, celebrated for its high efficiency, absence of organic solvent residues, and suitability for heat-sensitive compounds [

49].

4.3. Extraction of Polysaccharides and Fibers

Polysaccharides—particularly, cellulose, pectin, and starch—are the most abundant components in plant-derived wastes and are prized for their excellent biodegradability and film-forming properties. For instance, in the case of agricultural straws like wheat straw, an initial alkaline treatment is used to remove lignin and hemicellulose. Subsequent acid hydrolysis and mechanical shearing processes yield nanocellulose, a high-value material used to enhance the mechanical and barrier properties of packaging films [

30]. Similarly, green extraction methods for pectin from citrus peel waste have been extensively studied, leading to films with notable antimicrobial and oxygen barrier characteristics [

46].

4.4. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds

The integration of natural active substances with antioxidant, antimicrobial, or pH-responsive functions is a key strategy for developing active and smart packaging. By-products such as fruit and vegetable peels and seed meals are rich sources of anthocyanins, phenolic compounds, and carotenoids. These compounds are often extracted using green techniques like ultrasound, microwave, or subcritical water to preserve their bioactivity before incorporation into functional films [

50]. For example, one study successfully fabricated an SPI-based film with enhanced antioxidant and antimicrobial activity by compounding it with nanocellulose and polyphenols green-extracted from date palm leaves, significantly improving its overall performance [

51].

4.5. Challenges and Future Prospects

Despite significant technological advancements, the industrial-scale implementation of these extraction processes faces persistent challenges, including high energy consumption, potential solvent residues, difficulties in controlling product purity, and elevated production costs. The expense of enzymatic preparations, capital investment in specialized equipment, and process complexity currently limit the widespread adoption of many green extraction methods. Future research must focus on developing highly efficient, low-cost, and scalable green extraction systems. A particularly promising avenue is the development of integrated processes that combine in situ extraction and film fabrication in a single step. Such a paradigm shift towards process intensification would streamline the workflow, reduce costs, and realize a closed-loop, high-value utilization pathway from waste to functional film materials [

52].

5. Fabrication Methods for Biodegradable Packaging Films

As promising alternatives to conventional plastics, biodegradable packaging films derived from waste valorization are central to achieving a low-carbon, circular economy. The film fabrication method is the pivotal stage where the material’s micro- and nanostructure is engineered, thereby dictating its mechanical integrity, barrier performance, and functional capabilities. The choice of fabrication technology not only influences the film’s final properties but also determines its potential for scalability and application in practical packaging scenarios.

5.1. Conventional Film Fabrication Technologies

Conventional fabrication techniques are widely employed in both laboratory research and certain commercial applications due to their operational simplicity and accessible equipment.

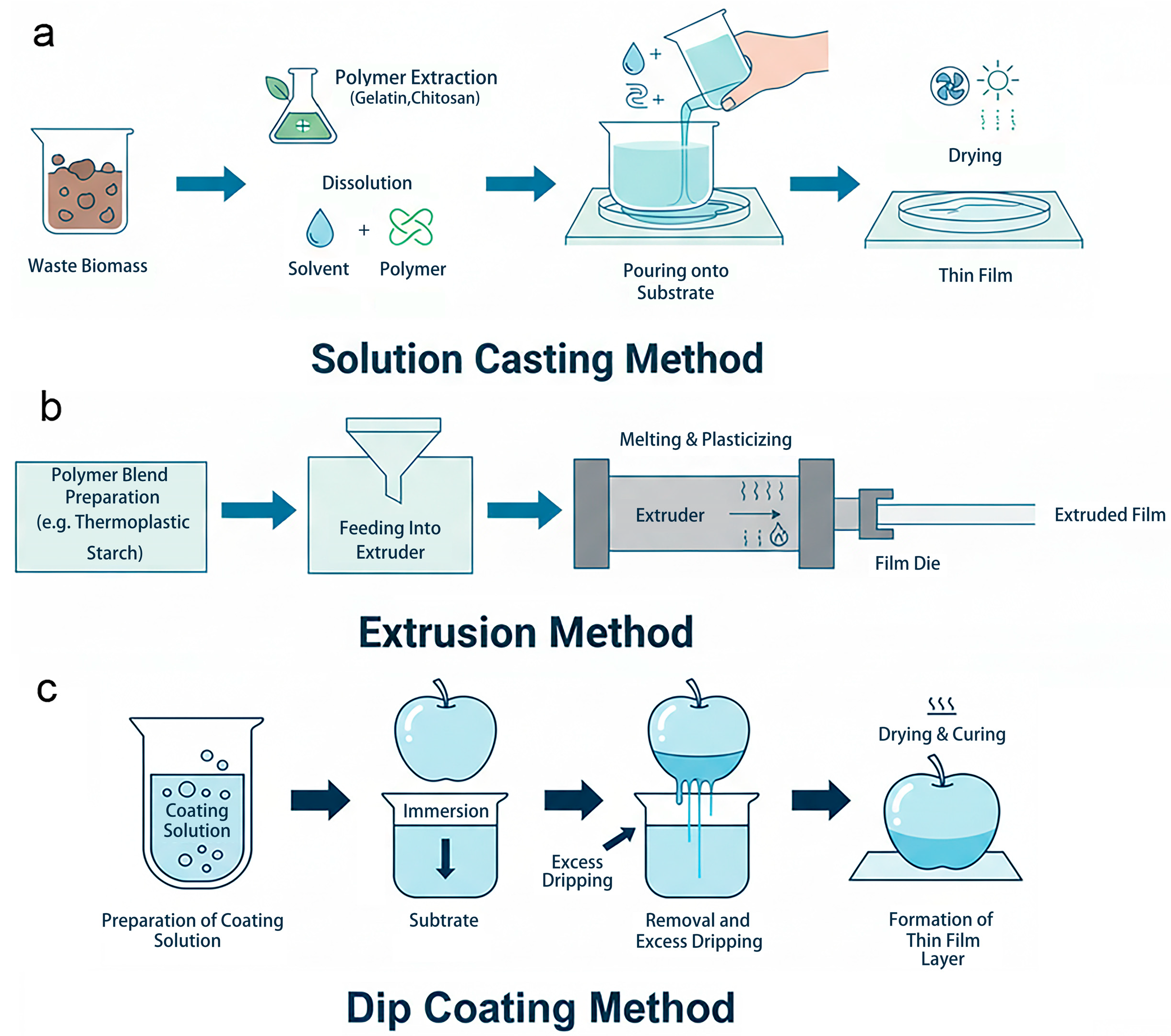

Solution Casting: This is the most common laboratory-scale method for film preparation (

Figure 6a). The technique involves dissolving biopolymers extracted from waste (e.g., gelatin, chitosan, pectin) in a suitable solvent to form a homogeneous solution, which is then cast onto a flat substrate and dried via evaporation. Films cast on glass plates can adhere strongly and be difficult to remove, whereas Teflon molds generally provide better release. Although thickness control is less precise than with some alternative methods, solution casting is well suited to multi-component composite films and to incorporating heat-sensitive functional additives, and is therefore widely used in functional-film research [

51].

Extrusion: In contrast, extrusion is geared towards large-scale industrial production, particularly for thermoplastic polymers like thermoplastic starch or polylactic acid blended with waste-derived fillers (e.g., nanocellulose from rice husks). In this process, the material is melted, plasticized, forced through a die, and rapidly cooled to form a continuous film (

Figure 6b). Its high throughput and efficiency make it the preferred method for commercial manufacturing of biodegradable packaging [

53].

Dip Coating: This method is primarily used to apply protective surface coatings, especially for fresh produce preservation. By immersing the target substrate into a film-forming solution, a thin, uniform layer is deposited, imparting antimicrobial and barrier properties (

Figure 6c). Although not suitable for producing standalone films, dip coating is highly effective for short-term protection of perishable foods [

54].

5.2. Advanced Film Fabrication Technologies

The co-occurrence network (

Figure 4) shows “electrospinning” and “nanocomposite” forming a distinct cluster, indicating their recognition as key enabling technologies. This section examines these advanced methods that correspond to the field’s push toward high-performance materials. To overcome the limitations of conventional methods in structural precision and functional integration, several advanced fabrication technologies have emerged. These techniques enable the engineering of sophisticated nano- and micro-architectures for enhanced performance.

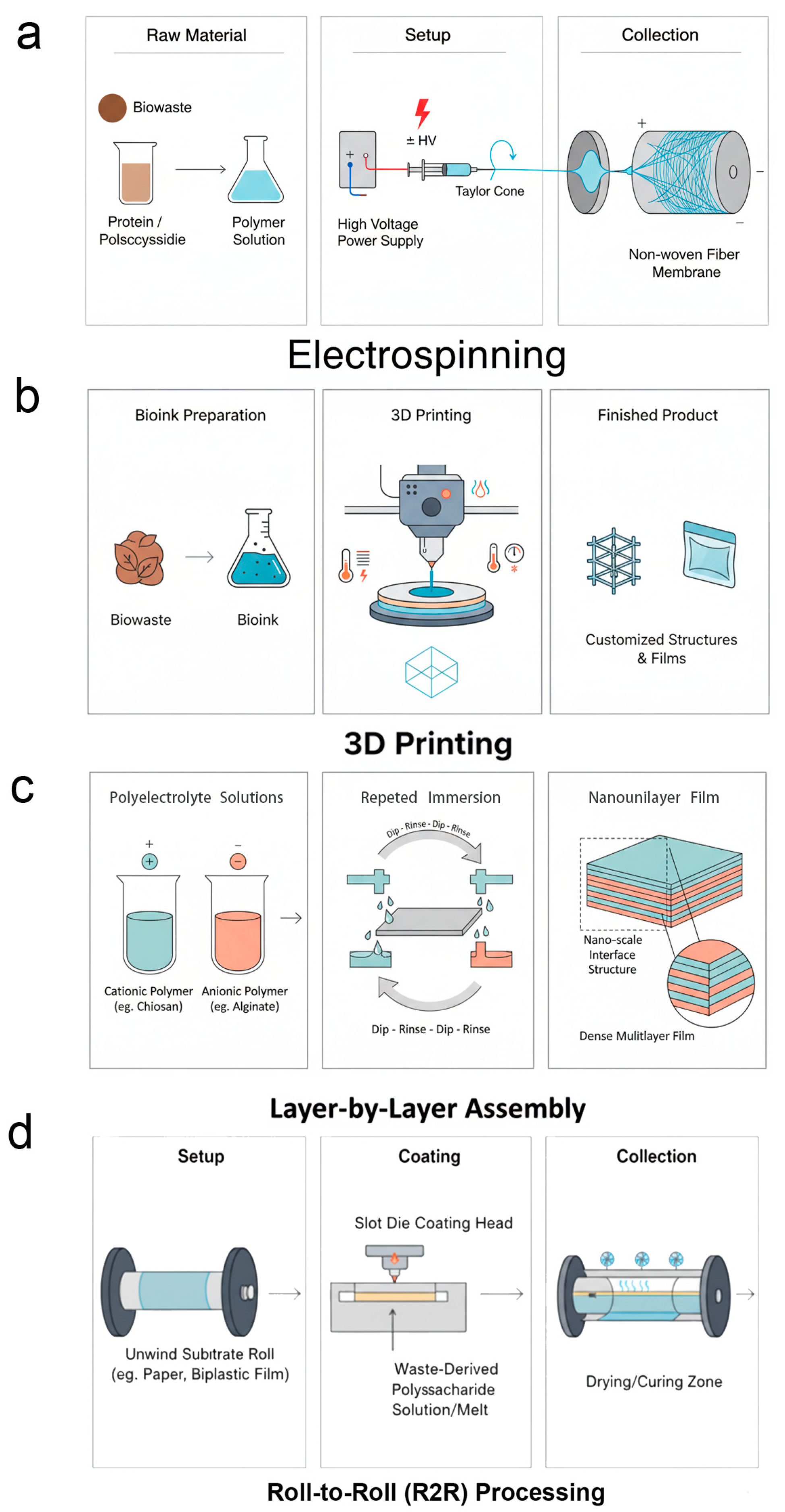

Electrospinning: This technology is widely recognized for its ability to produce non-woven mats of nanoscale fibers. By applying a high-voltage electrostatic field to a polymer solution, a continuous jet is ejected and collected as a fibrous membrane (

Figure 7a). The resulting structure, characterized by a high surface-area-to-volume ratio and high porosity, is ideal for applications requiring controlled release, such as drug delivery and active antimicrobial packaging. For instance, keratin extracted from waste feathers has been successfully electrospun to create functional membranes that are both biodegradable and antimicrobial [

55]. Although structurally distinct from continuous films, these nonwoven mats can serve as functional analogues in biodegradable packaging applications, offering comparable barrier properties, flexibility, and potential for active agent incorporation, such as in breathable or controlled-release packaging systems.

3D Printing (Additive Manufacturing): 3D printing constructs films or packaging units layer-by-layer from a digital model, offering unparalleled control over geometry and architecture (

Figure 7b). This makes it ideal for fabricating customized smart labels and functional structured films. Panraksa et al. developed a “bio-ink” from carboxymethyl cellulose extracted from durian peel waste, enabling the 3D printing of bespoke edible packaging films [

56].

Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly: LbL assembly builds nanometer-scale multilayer films by alternately adsorbing oppositely charged polyelectrolytes (e.g., cationic chitosan and anionic alginate) onto a substrate (

Figure 7c). This method provides precise control over film thickness and interfacial properties, making it highly suitable for high-performance applications requiring superior gas barrier properties, smart-responsive behavior, or encapsulated active agents [

54].

Roll-to-Roll (R2R) Processing: This advanced technique enables continuous, large-scale production of biopolymer films by unwinding a substrate roll, applying coatings or extrusions (e.g., slot die coating for waste-derived polysaccharides), and rewinding the finished product (

Figure 7d). It is particularly suitable for integrating functional additives from biomass waste, offering high throughput, cost-efficiency, and scalability for industrial applications in sustainable packaging. For instance, R2R has been used to produce uniform thin films from modified biopolymers, enhancing barrier properties while minimizing material waste [

57].

5.3. Strategic Integration of Waste-Derived Components

In the fabrication process, components derived from waste are strategically integrated to fulfill specific roles within the film matrix, serving as the structural backbone, reinforcing phase, or functional additive.

As a Matrix Material: Natural polymers with inherent film-forming capabilities, such as gelatin (from animal hides), soy protein (from okara), and pectin (from fruit pomace), can be used directly as the primary film-forming matrix.

As a Reinforcing Component: Materials like nanocellulose, extracted from agricultural straws, are incorporated as reinforcing agents. Their high modulus and aspect ratio effectively enhance the mechanical strength and thermal stability of the composite film [

58].

As a Functional Additive: Bioactive compounds, such as natural pigments and polyphenols from waste fruits and vegetables (e.g., red cabbage, beetroot) or tea residues, can be incorporated via blending, encapsulation, or surface coating. These additives impart antioxidant, antimicrobial, or pH-responsive properties, which are critical for realizing active and smart packaging solutions [

58].

5.4. Modification and Optimization Strategies

To overcome the inherent limitations of films made from natural biopolymers—such as poor mechanical properties, water sensitivity, or processability—various modification strategies are employed. Plasticizers (e.g., glycerol) are added to increase film flexibility by disrupting intermolecular polymer chain interactions. Cross-linking agents (e.g., glutaraldehyde, genipin) create covalent bonds between polymer chains, forming a stable network that enhances water resistance and thermal stability. Finally, blending multiple polymers (e.g., gelatin–chitosan) allows for the creation of composite materials where the properties of each component are combined to achieve synergistic performance and broaden the application scope [

54].

6. Performance Evaluation of Packaging Films

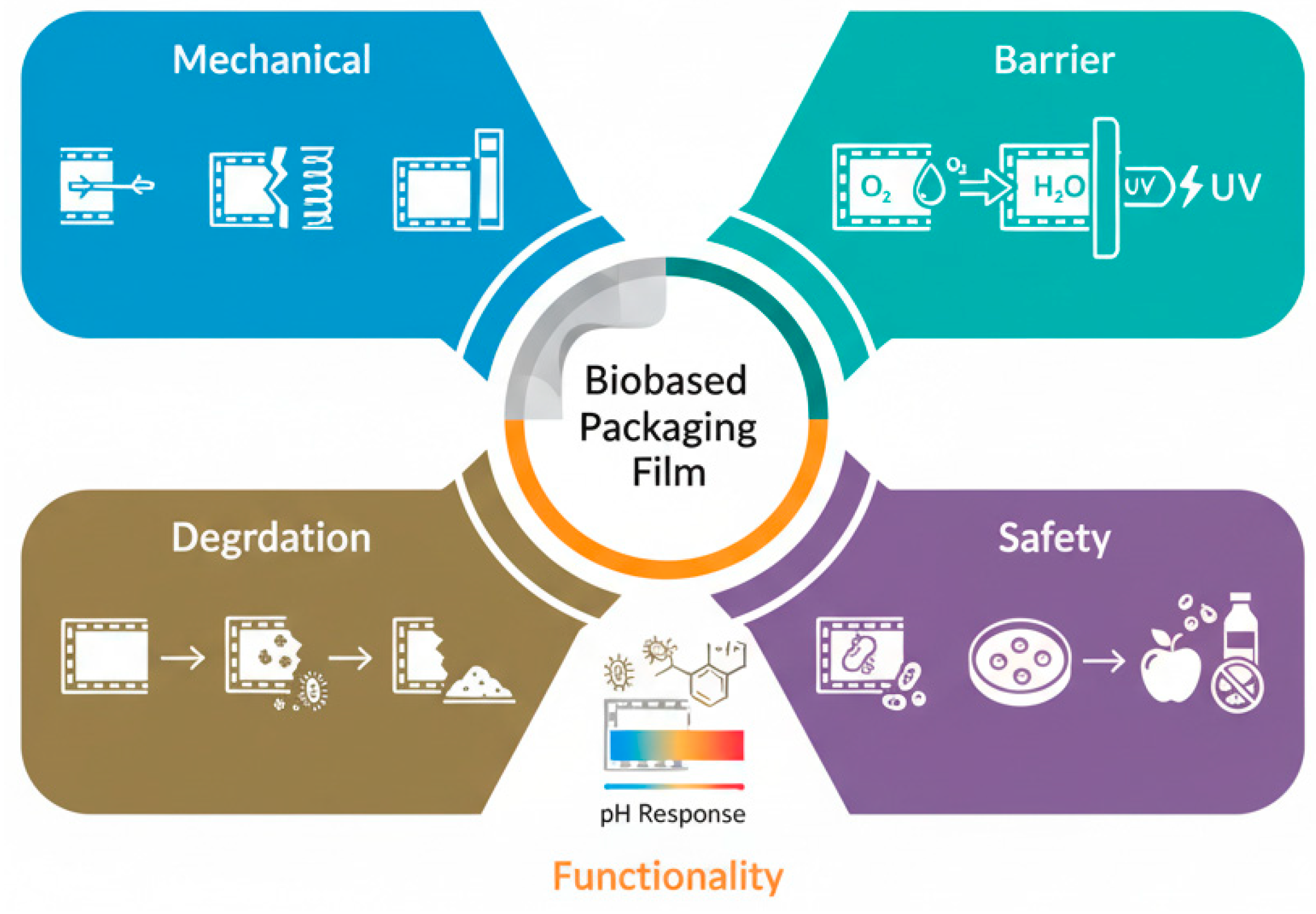

The performance profile of a biodegradable packaging film is the ultimate determinant of its viability and market potential in applications ranging from food preservation to medical materials. A systematic evaluation of its mechanical, barrier, biodegradable, safety, and functional properties is therefore essential for optimizing material formulations, controlling fabrication processes, and enabling industrial scale-up. As outlined in

Figure 8, these performance metrics are deeply interconnected, collectively reflecting the complex interplay between the film’s composition, microstructure, and functional behavior. This evaluation serves as a critical feedback mechanism for the rational design of next-generation sustainable materials.

To achieve optimal mechanical and functional properties in waste-derived biodegradable packaging films, the material structure must be carefully engineered. Key structural features include multilayer architectures, which combine barrier layers for moisture and gas resistance, active layers for antimicrobial or antioxidant release, and control layers for regulated functionality. Nanocomposite reinforcements, such as incorporation of nanocellulose or other nanofillers, enhance mechanical strength through improved dispersion and interfacial interactions within the polymer matrix. Additionally, cross-linked polymer networks promote structural integrity, reducing brittleness and improving flexibility, water resistance, and overall stability. These designs ensure a homogeneous, robust film matrix that balances biodegradability with performance requirements, as evidenced in recent advancements.

6.1. Mechanical Properties

Mechanical properties are the core indicators of a packaging film’s structural integrity and its ability to withstand physical stress during handling, transport, and storage. The primary metrics include tensile strength (TS), which reflects the maximum stress a material can endure before fracturing; elongation at break (EAB), which measures its ductility and ability to deform; and Young’s modulus, which quantifies its stiffness. The mechanical characteristics of bio-based films are highly dependent on their molecular structure, component ratios, and interfacial compatibility within composites. For instance, Riaz et al. developed an active film by compounding orange peel waste with wheat straw, finding that tensile strength peaked at a fiber content of 6% but subsequently decreased due to particle agglomeration at higher concentrations [

41]. This highlights the critical need for optimizing filler content to avoid defects. Furthermore, films based on animal-derived gelatin typically exhibit excellent flexibility and elongation but possess lower tensile strength compared to more rigid materials derived from plant polysaccharides like cellulose or chitosan [

59].

6.2. Barrier Properties

Barrier properties define a film’s ability to control the transmission of gases (e.g., oxygen), water vapor, and lipids, making them a critical determinant of food shelf life and quality preservation. Key evaluation parameters include gas transmission rate (GTR), water vapor permeability (WVP), and oil permeation. The performance in this domain varies significantly among different biopolymer-based films and is often a primary challenge for replacing conventional plastics. Research by Riaz et al. demonstrated that films developed from avocado seed by-products exhibited low WVP and excellent UV-blocking capabilities, showcasing the potential of underutilized waste streams to yield high-performance barrier materials [

41]. Moreover, the incorporation of nanofillers, such as nanocellulose or montmorillonite clay, is a common strategy to enhance barrier performance by creating a more tortuous path for permeating molecules, thereby increasing the film’s structural density.

6.3. Biodegradability

Biodegradability is the cornerstone of a packaging film’s environmental credentials, defining its capacity to be broken down by microorganisms into benign natural products. It is crucial to recognize that biodegradability is not an intrinsic material property but is highly dependent on the specific receiving environment (e.g., industrial compost, soil, marine). Standard evaluation methods include soil burial tests, simulated composting, and hydrolysis assays. A review by Duguma et al. indicated that films derived from agricultural by-products resources exhibit excellent degradation rates under composting conditions, with over 70% mass loss within 30 days—a stark contrast to synthetic plastics [

60]. The molecular structure of the film, such as a higher content of hydroxyl groups and lower crystallinity, can significantly accelerate microbial decomposition.

6.4. Safety

For applications involving direct food contact, the toxicological safety, migrant release, and microbial safety of bio-based packaging films must be rigorously assessed. This is a non-negotiable prerequisite governed by stringent regulatory standards. Toxicity is typically evaluated using in vitro cell culture assays or in vivo animal models to confirm biocompatibility. Migration tests are conducted using food simulants to quantify the potential transfer of substances from the packaging to the food. Microbial safety assesses the material’s resistance to microbial growth. In a study by Bahar et al., the incorporation of zinc oxide nanoparticles into a gelatin/chitosan composite film significantly enhanced its antimicrobial activity and storage stability without compromising its biocompatibility [

59]. Such strategies, which combine natural polymers with functional additives, are effectively expanding the application boundaries for biopolymer films in food packaging.

6.5. Functional Properties

The bibliometric analysis identified “shelf-life” (frequency = 66, centrality = 0.71) and “antioxidants” (frequency = 41) as core high-frequency keywords, with “shelf-life” showing strong citation burst from 2022–2023. This quantitatively validates that functional properties, particularly preservation efficacy, constitute the field’s primary technological objective, as examined below.

Modern packaging is evolving from a passive container to an active system that enhances product quality and communicates with the consumer. This “value-added” dimension includes properties such as antimicrobial activity, antioxidant capacity, and environmental responsiveness. Antimicrobial and antioxidant functions are typically conferred by incorporating active agents that inhibit microbial growth or scavenge free radicals. Smart-responsive functions, such as colorimetric indication of pH or temperature changes, enable real-time monitoring of food freshness. For example, Dordević et al. engineered a chitosan–carrageenan composite film incorporating black lentil extract. This film exhibited antioxidant, antimicrobial, and pH-responsive capabilities, undergoing a distinct color change in response to pH shifts, thereby providing a viable material solution for intelligent food packaging that can visually monitor food spoilage [

61].

7. Application Domains

Driven by escalating global concerns over environmental sustainability, plastic pollution, and food safety, biodegradable packaging films developed from waste biomass are demonstrating vast potential across multiple industrial sectors. This versatility positions them as a platform technology capable of delivering sustainable solutions beyond the food industry.

7.1. Food Packaging

Food packaging remains the primary and most extensively researched application for biodegradable films. Materials based on gelatin, whey protein, chitosan, polysaccharides, and their composites have been successfully applied to extend the shelf life of perishable foods, including fresh fruits and vegetables, dairy products, and meat. These films create a modified environment that can inhibit microbial growth, control moisture migration, and slow down oxidative reactions, thereby preserving the quality and safety of the food product [

59].

For Fresh Produce: Alginate–chitosan composite films, for example, are widely used for coating fruits like strawberries and tomatoes. Their excellent gas barrier properties and biocompatibility significantly reduce decay rates and help maintain the fruit’s color, firmness, and nutritional value [

61].

For Dairy and Meat Products: Films derived from whey protein have been used as edible coatings or packaging for cheese and yogurt, effectively controlling the growth of lactic acid bacteria and molds. Similarly, active films containing natural antimicrobials are being developed to package fresh meat, inhibiting spoilage pathogens and extending its refrigerated shelf life.

7.2. Medical and Biomedical Packaging

In the medical field, the application of biodegradable films is concentrated in areas requiring biocompatibility and controlled degradation, such as pharmaceutical packaging, medical device wrapping, and advanced wound dressings. Their ability to degrade safely within a biological environment makes them ideal for short-term, single-use medical applications. Recently, electrospun membranes fabricated from natural proteins and polysaccharides have been extensively investigated as functional wound dressings. The nanofibrous architecture of these materials promotes cell adhesion and tissue regeneration while allowing for the sustained release of therapeutic agents like antibiotics or growth factors to facilitate healing and prevent infection [

57]. Furthermore, their excellent barrier properties make them suitable for packaging sensitive biologics and pharmaceuticals that are susceptible to degradation from moisture or oxygen.

7.3. Personal Care and Cosmetics Packaging

The personal care industry is increasingly demanding green and safe packaging solutions that align with the “natural” ethos of many products. High-end brands have begun to adopt biodegradable films made from plant proteins, chitosan, or pectin for the primary or secondary packaging of cosmetics and skincare items. These materials not only provide mechanical protection but can also offer complementary benefits such as antioxidant and moisturizing properties, making them particularly suitable for products rich in natural extracts [

62]. Additionally, water-soluble films are being used for single-dose packaging of products like bath bombs or laundry pods, as well as for sheet masks, where the packaging can be designed to dissolve harmlessly after use, minimizing its environmental footprint.

7.4. Sustainable Consumer Goods Packaging

The rapid growth of e-commerce and food delivery services has dramatically increased the consumption of single-use plastics, intensifying their negative environmental impact. Consequently, biodegradable films derived from agricultural wastes (e.g., straw, fruit peels, coffee grounds) are emerging as a key material for a new generation of eco-friendly consumer packaging. These materials offer a compelling combination of mechanical and barrier performance with the crucial advantage of degrading into harmless substances in natural or managed environments [

63]. Key applications include biodegradable shopping bags, compostable food service containers, and edible coatings for on-the-go food items. While challenges related to production cost and standardization remain, their superior environmental profile is driving strong policy support and stimulating innovation across the entire supply chain.

8. Challenges, Life-Cycle Assessment, and Future Prospects

Despite the significant scientific progress and immense potential of biodegradable packaging films, their transition from laboratory-scale innovation to widespread industrial adoption is impeded by a confluence of technical, economic, and regulatory challenges. As illustrated in

Figure 9, these factors are interconnected and overcoming them requires a holistic and strategic approach. This section will critically analyze these barriers and outline a forward-looking perspective on the future trajectory of the field.

8.1. LCA and Environmental Trade-Offs

While “biodegradability” and “waste valorization” imply sustainability, a holistic LCA is essential to quantify the true environmental impact and avoid problem-shifting [

64,

65]. The bibliometric analysis (

Section 2.4) identified LCA as a foundational theme, and a review of LCA literature reveals a complex picture of trade-offs [

66].

- (1).

Advantages: Compared to conventional petrochemical plastics (e.g., polyethylene, polypropylene), bio-based films derived from waste consistently demonstrate significant advantages in categories like Global Warming Potential (GWP) and fossil fuel depletion. Studies have reported CO

2-eq reductions ranging from 30% to 70% [

64,

67], primarily because the feedstock is waste-based and biogenic carbon is utilized.

- (2).

Environmental Trade-offs: However, these advantages often come at the cost of higher impacts in other categories. The primary trade-offs include increased eutrophication and acidification potential [

65,

66]. These are frequently linked not to the waste itself, but to the energy- and chemical-intensive “hotspots” in the value chain: namely, the extraction and purification processes (as discussed in

Section 4) and, in some cases, the transportation of bulky, high-moisture-content waste.

- (3).

Implications: This underscores that “bio-based” or “biodegradable” does not inherently mean “sustainable” [

66]. The overall environmental benefit is critically dependent on optimizing the energy and chemical inputs during extraction and processing. These LCA findings strongly reinforce the necessity of developing and scaling the green extraction technologies (

Section 4) and efficient fabrication methods (

Section 5) to realize the full environmental potential of these materials.

8.2. Techno-Economic Hurdles: Cost Competitiveness and Scalability

A primary impediment to market penetration is the unfavorable cost–performance ratio of many bio-based films compared to their petroleum-based counterparts. The high cost stems largely from the energy- and resource-intensive processes required for the extraction, purification, and modification of biopolymers from heterogeneous waste feedstocks [

68]. To quantify this gap, conventional petroleum-based packaging plastics (e.g., PE, PET) have a mature market price in the range of

$1.5–

$2.5/kg. Even the most established industrial-scale bioplastic, Polylactic Acid (PLA), competes at a higher bracket of

$2.5–

$4.0/kg. In stark contrast, the purified raw materials derived from waste, such as food-grade gelatin or industrial-grade chitosan powder, often have a baseline cost exceeding

$10–

$20/kg before they are even processed into a film [

69]. This high feedstock cost is directly coupled with the issue of scalability [

70]. Current fabrication methods, while effective at the lab or pilot scale (e.g., solution casting, as discussed in

Section 5.1), often face significant obstacles in achieving the consistent, high-throughput production (e.g., extrusion) required for commercial viability [

38]. Furthermore, the seasonal and geographical variability of waste biomass poses a significant challenge to establishing a stable and standardized raw material supply chain, which is essential for industrial-scale manufacturing [

39].

8.3. Performance and Reliability: Overcoming Inconsistency and Unpredictable Degradation

The inherent variability of waste feedstocks is a major source of performance inconsistency in the final film products. Differences in the composition of agricultural residues, such as those from various fruit peels or nut shells, can lead to significant batch-to-batch variations in mechanical strength, barrier properties, and even film uniformity [

38]. This lack of reliability is a critical barrier for commercial applications that demand stringent quality control.

Furthermore, while “biodegradability” is their key selling point, the actual degradation process is highly dependent on environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, microbial population). In non-ideal environments, the degradation rate can be significantly slower than anticipated, or the process may be incomplete, failing to fully mitigate environmental persistence [

38]. A critical concern is the potential for secondary pollution, where additives, cross-linkers, or nanomaterials incorporated into the film matrix could be released during degradation, posing risks to soil and aquatic ecosystems [

37]. Ensuring predictable end-of-life behavior and environmentally benign degradation products remains a key research challenge.

8.4. The Regulatory Maze: A Need for Harmonization

The global regulatory landscape for biodegradable and food-contact materials is fragmented and often inconsistent across different countries and regions. This lack of harmonization creates significant barriers to international trade and market entry for new products [

40]. Manufacturers face uncertainty in navigating the complex web of standards for material safety, compostability certification, and food-contact compliance. Ambiguities regarding end-of-life labeling (e.g., “compostable” vs. “biodegradable”) can confuse consumers and lead to improper disposal, undermining the material’s intended environmental benefits. Establishing clear, globally harmonized standards and certification protocols is therefore crucial for building consumer trust and enabling a functional circular economy for these materials [

41].

8.5. Future Prospects: A Roadmap for Next-Generation Sustainable Packaging

Despite these challenges, the future for biodegradable packaging films is bright, with research poised to advance along several strategic fronts:

- (1)

Ternary Hybrid Nanocomposites. Instead of simple blends, future work must focus on hybrid ternary systems that leverage the unique strengths of different waste streams (e.g., the mechanical strength of nanocellulose [agricultural waste], the antimicrobial activity of chitosan [animal waste], and the film-forming/flexibility of gelatin or pectin [food waste]).

Key Research Question: How can the interfacial compatibility between hydrophilic (nanocellulose) and amphiphilic (proteins) components be precisely engineered (e.g., using green cross-linkers like genipin or enzymatic treatment) to create a nanostructure that synergistically blocks water and oxygen, achieving barrier properties comparable to synthetic EVOH?

- (2)

Integrated Biorefinery Pathways. To overcome the techno-economic hurdles (

Section 8.2), process intensification is non-negotiable. For instance, the lignocellulosic residues remaining after biopolymer extraction could be diverted to alternative high-value pathways, such as pyrolysis to produce biochar for soil amendment, a process that has been shown to enhance the circular economy of agricultural residues [

71]. A key pathway is the use of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES). Key Research Question: Can novel DES systems be designed to serve a dual purpose: first, to selectively extract target biopolymers (e.g., pectin, protein) from the raw biomass, and second, to act directly as the solvent and plasticizer in the final film fabrication (e.g., extrusion), thus creating a “one-pot” process that eliminates the costly separation, drying, and re-solubilization steps?

- (3)

Specific-Target Intelligent Sensors. The field must move beyond simple pH-responsive anthocyanin indicators. The next generation requires specificity. This involves integrating enzyme-immobilized sensors into waste-derived substrates (e.g., electrospun keratin or cellulose nanofibers, as discussed in

Section 5.2).

Research Question: Can specific enzymes (e.g., amine oxidase) be successfully immobilized onto these bio-based nanofiber mats to detect specific spoilage markers (e.g., biogenic amines like histamine) via a highly visible colorimetric change, offering true spoilage detection rather than just pH monitoring?

- (4)

Designing for Anaerobic Digestion (AD). “Biodegradable” is insufficient; the end-of-life must align with existing, high-value waste infrastructure, such as AD. Research Question: How do critical material modifications (e.g., nanocomposite reinforcement with cellulose, or chemical cross-linking to improve water resistance) quantitatively impact the Biomethane Potential (BMP) and degradation kinetics within an anaerobic digester? Can formulations be optimized to be not only compostable but also a valuable feedstock for biogas generation?

In summary, while the path to widespread adoption is challenging, continued innovation in material science, process engineering, and regulatory alignment will undoubtedly unlock the full potential of biodegradable films. They are poised to become not just a sustainable alternative, but a superior, functional, and intelligent packaging solution for the future.

9. Conclusions

Biodegradable packaging films, engineered from the valorization of agricultural, food, and animal processing wastes, represent a cornerstone of sustainable material science. This review has systematically charted the landscape of this rapidly evolving field, from its conceptual foundations in the circular economy to the intricate details of material fabrication and performance. By leveraging abundant and underutilized biomass, these materials offer a compelling pathway to mitigate the dual crises of plastic pollution and resource depletion.

Despite their significant environmental and functional advantages, the journey from laboratory potential to ubiquitous commercial application is contingent upon overcoming several critical challenges. The primary barriers remain the high production costs, inconsistencies in material performance, the complexities of industrial-scale production, and the need for a harmonized regulatory framework. To accelerate progress and realize the full potential of these materials, future research and development efforts must be strategically focused on the following key pillars:

- (1)

Overcoming the Core Techno-Economic Barrier: The primary challenge is economical. Future work must focus on integrated biorefinery pathways (e.g., using Deep Eutectic Solvents) to drastically reduce the feedstock cost, which (at >$10–$20/kg for materials like chitosan) is an order of magnitude higher than petroleum plastics ($1.5–$2.5/kg).

- (2)

Engineering for High-Performance and Specific End-of-Life: The field must move beyond simple blends to ternary hybrid nanocomposites to solve the critical moisture barrier challenge. Furthermore, the goal must shift from “biodegradability” to “designing for a managed end-of-life,” such as optimizing formulations for Anaerobic Digestion (AD) compatibility.

- (3)

Validating and Mitigating Environmental Trade-offs: While LCA studies confirm significant benefits, such as 30–70% CO2-eq reductions, they also highlight critical environmental trade-offs (e.g., eutrophication and acidification) from the energy-intensive extraction processes. Future research must prioritize scaling green extraction technologies to mitigate these hot spots.

- (4)

Advancing from Simple to Specific Functionality: The field must mature from simple pH indicators to high-value smart systems. This includes developing specific-target intelligent sensors (e.g., for biogenic amines) and integrating them into functional waste-derived substrates like electrospun nanofibers.

In conclusion, biodegradable packaging films are poised to become a transformative technology in the global shift towards a sustainable future. As scientific innovation continues to address the existing challenges, and as market demand for green solutions intensifies, these materials are set to transition from a promising niche to a mainstream pillar of the packaging industry, making a substantial contribution to global environmental stewardship.