Assessment of the Impact of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Carbon Emissions Using Remote Sensing and Deep Learning: A Case Study of the Kağıthane Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

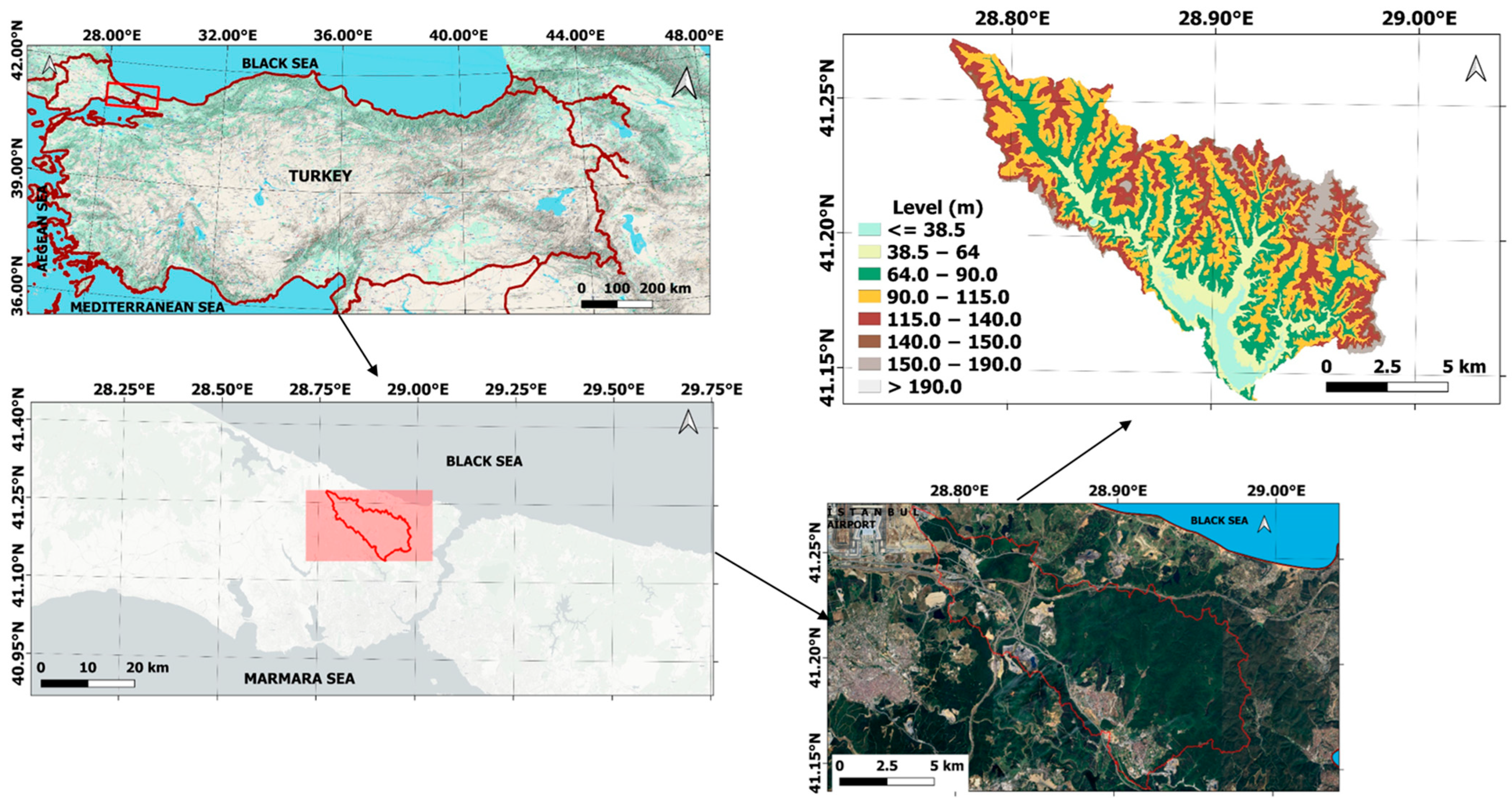

2.1. Study Area

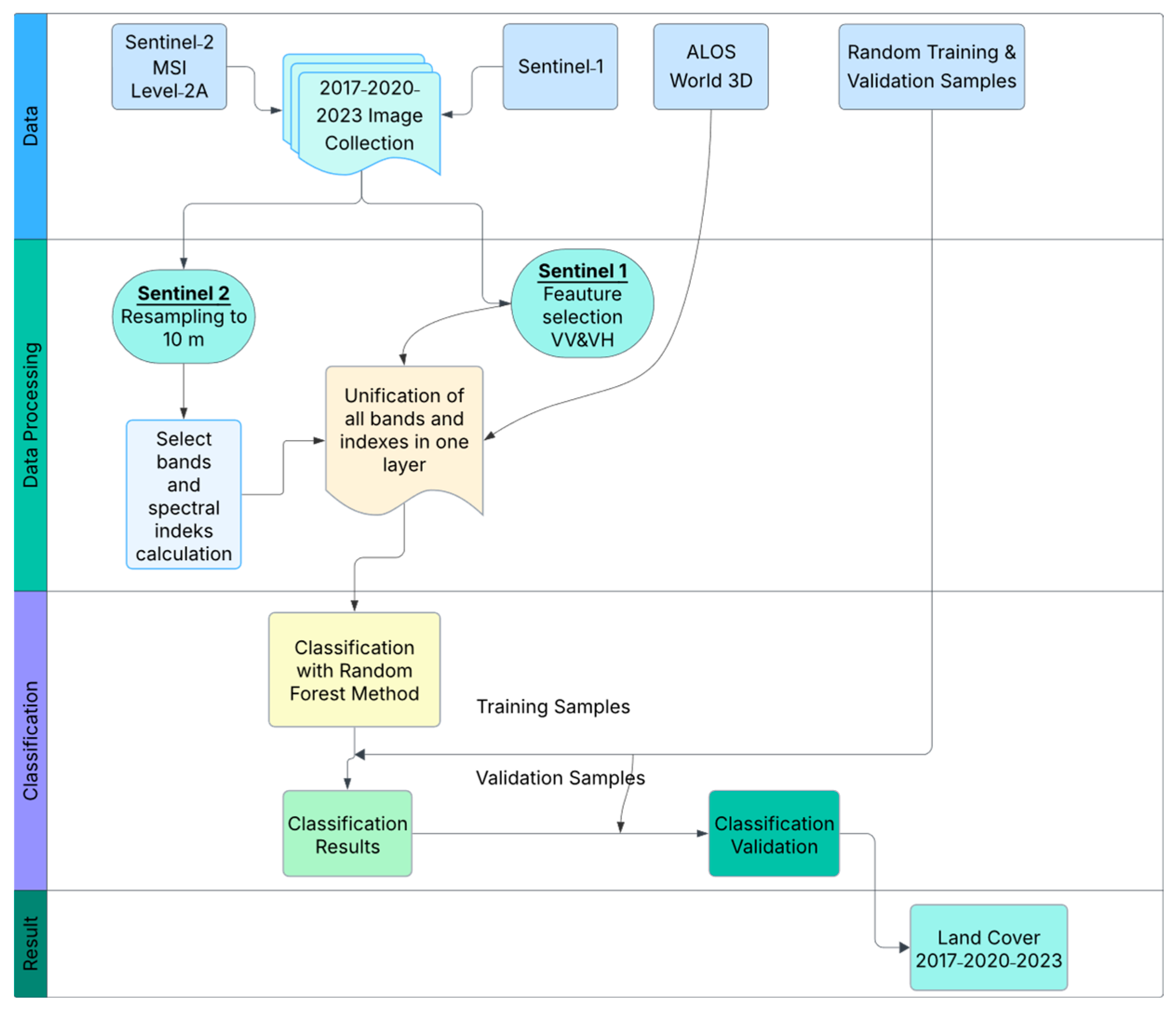

2.2. Dataset

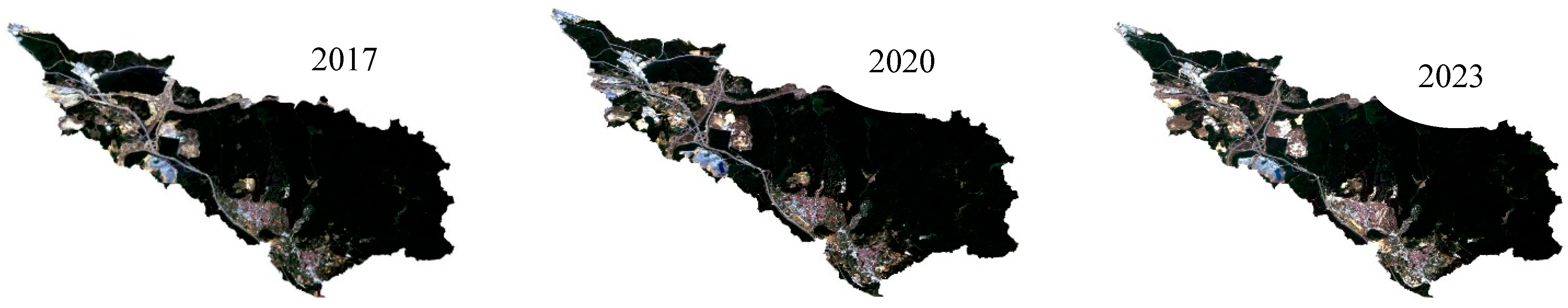

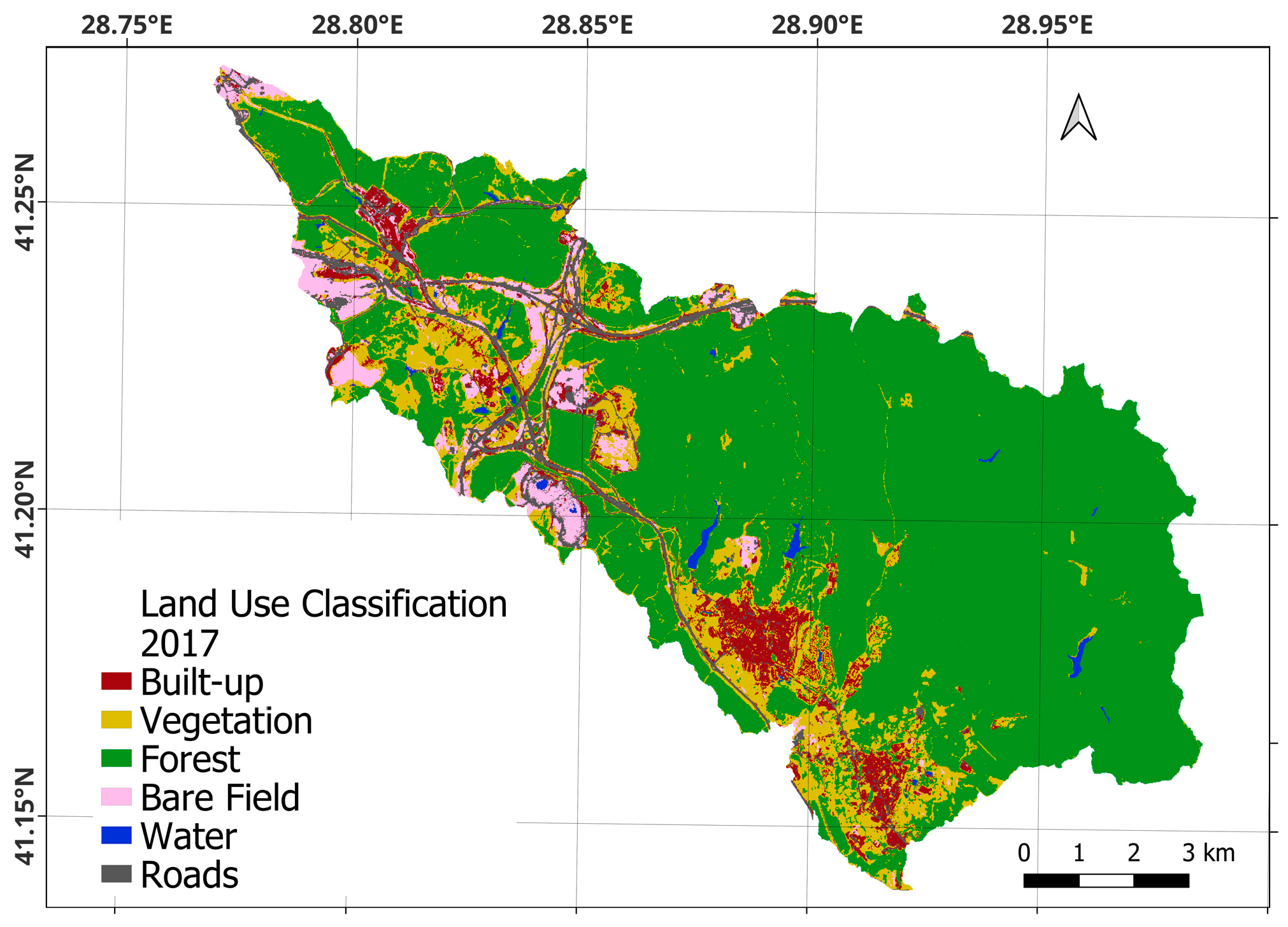

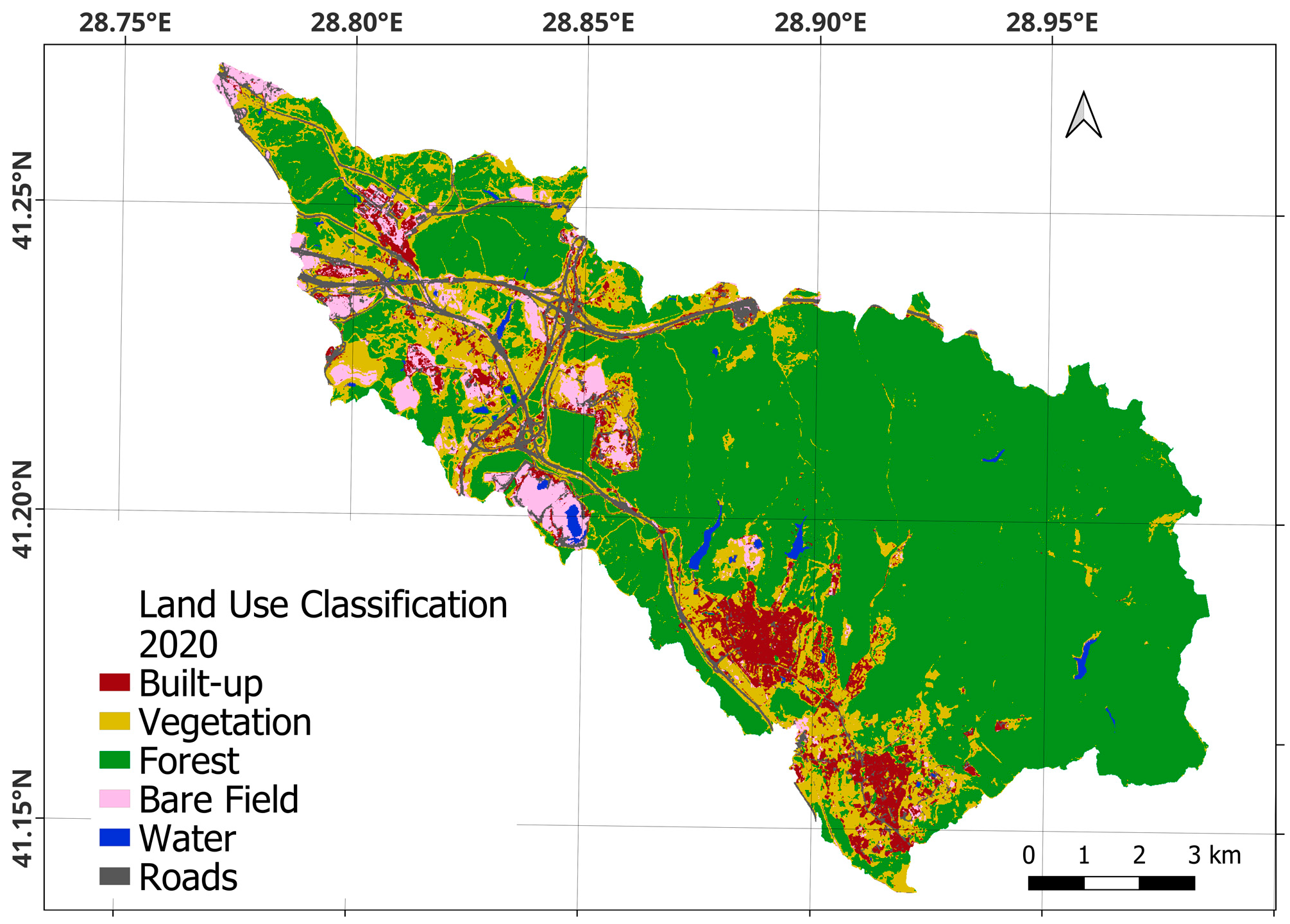

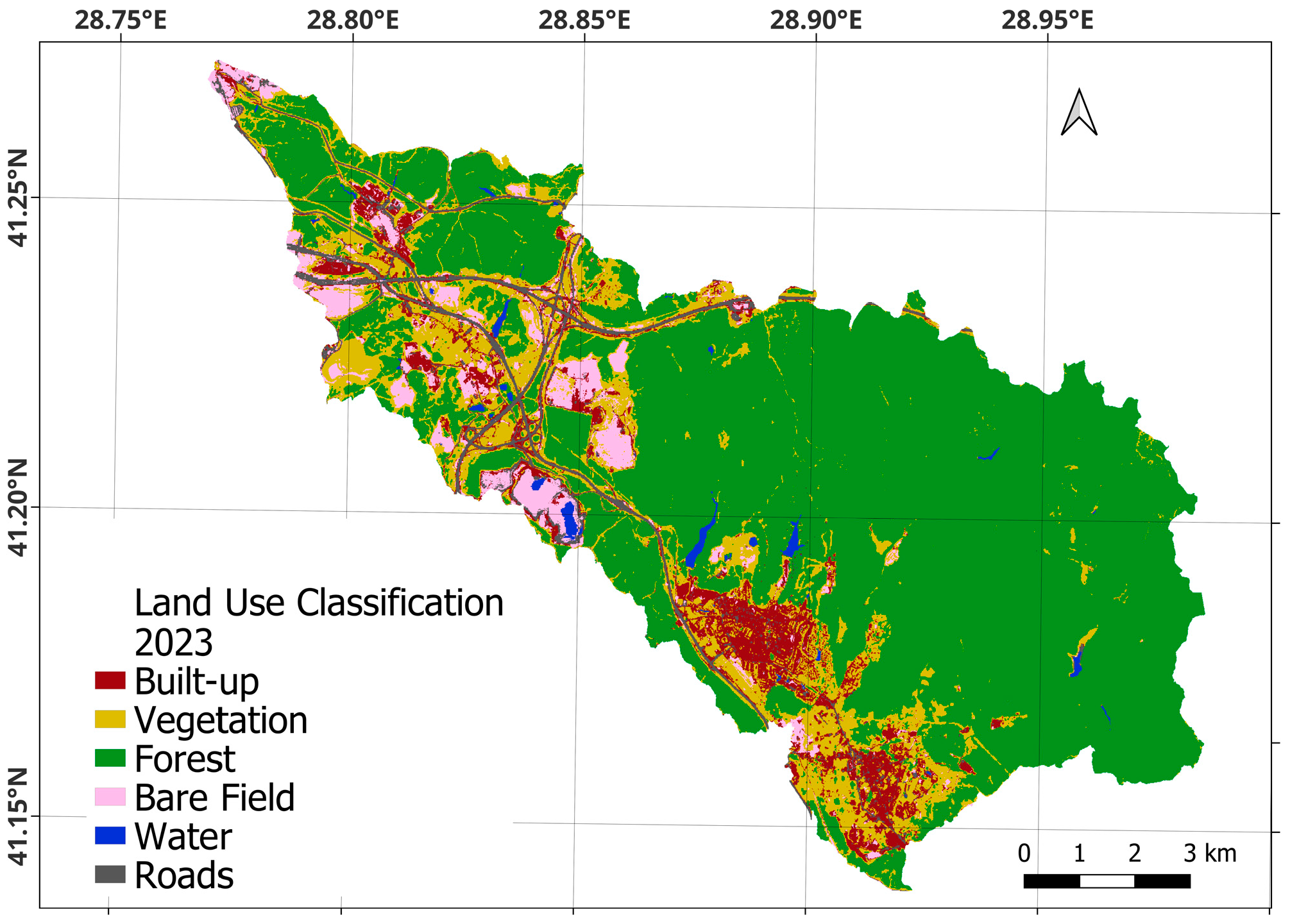

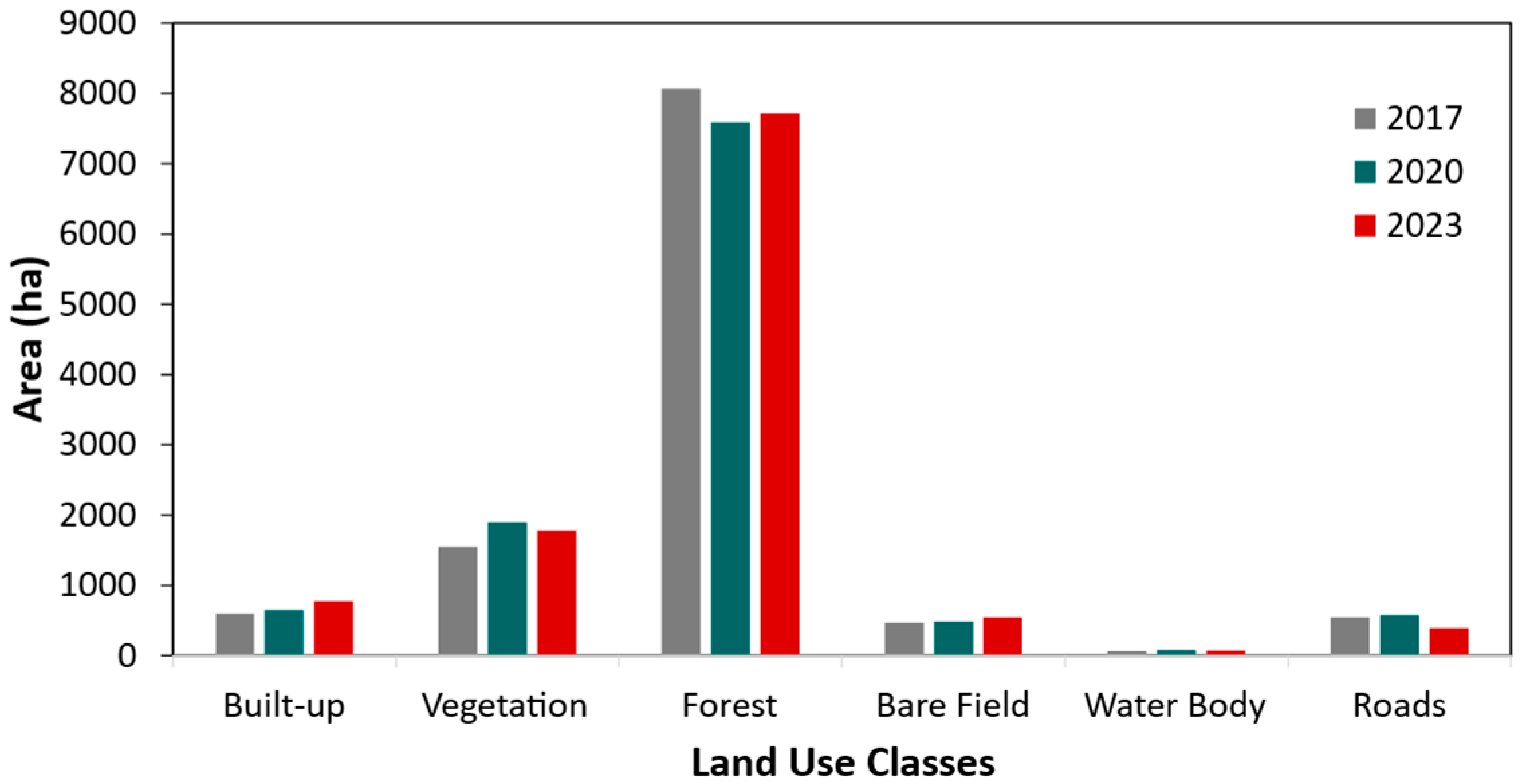

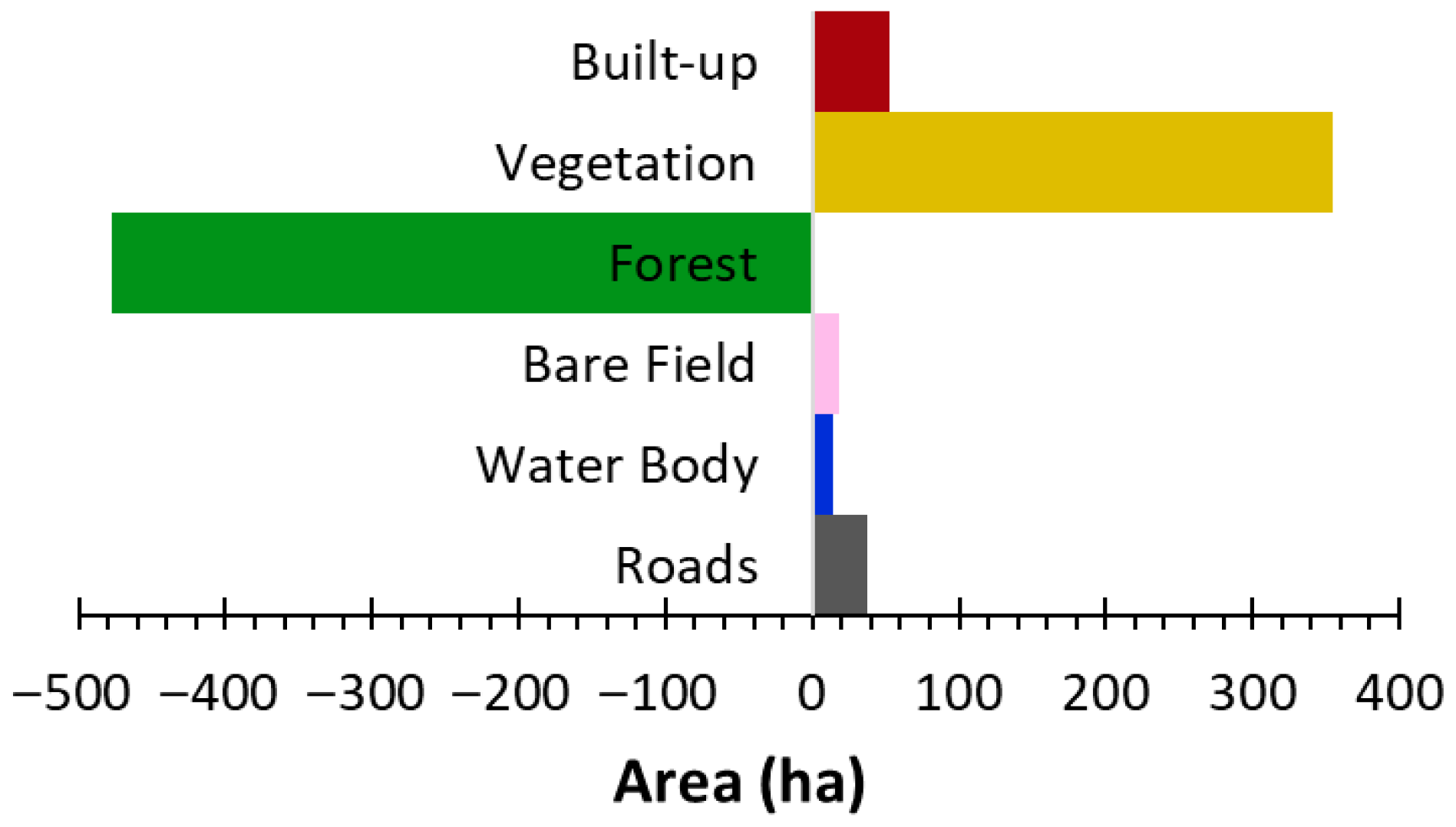

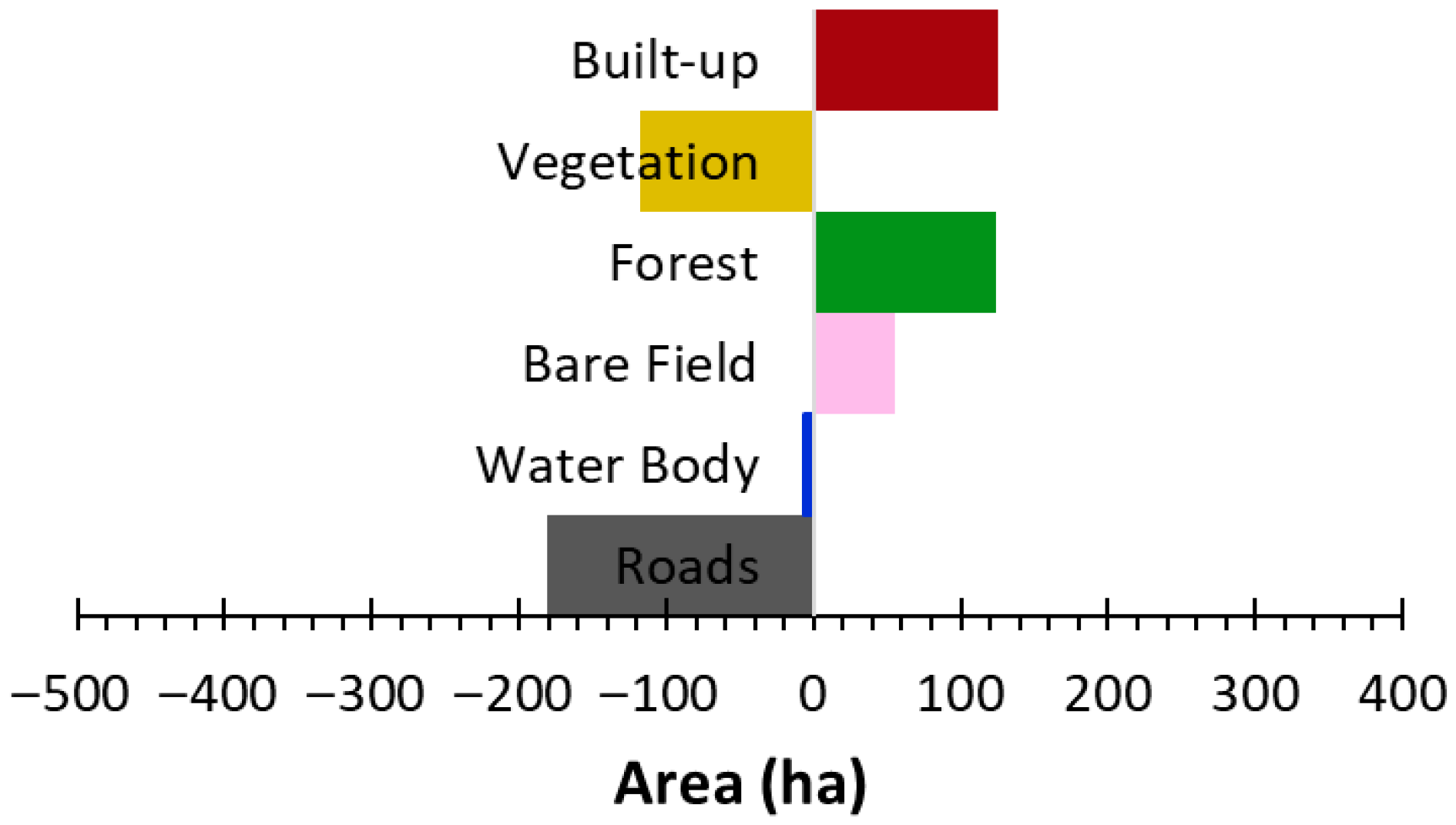

2.3. Determination of Land Use and Land Cover Classification

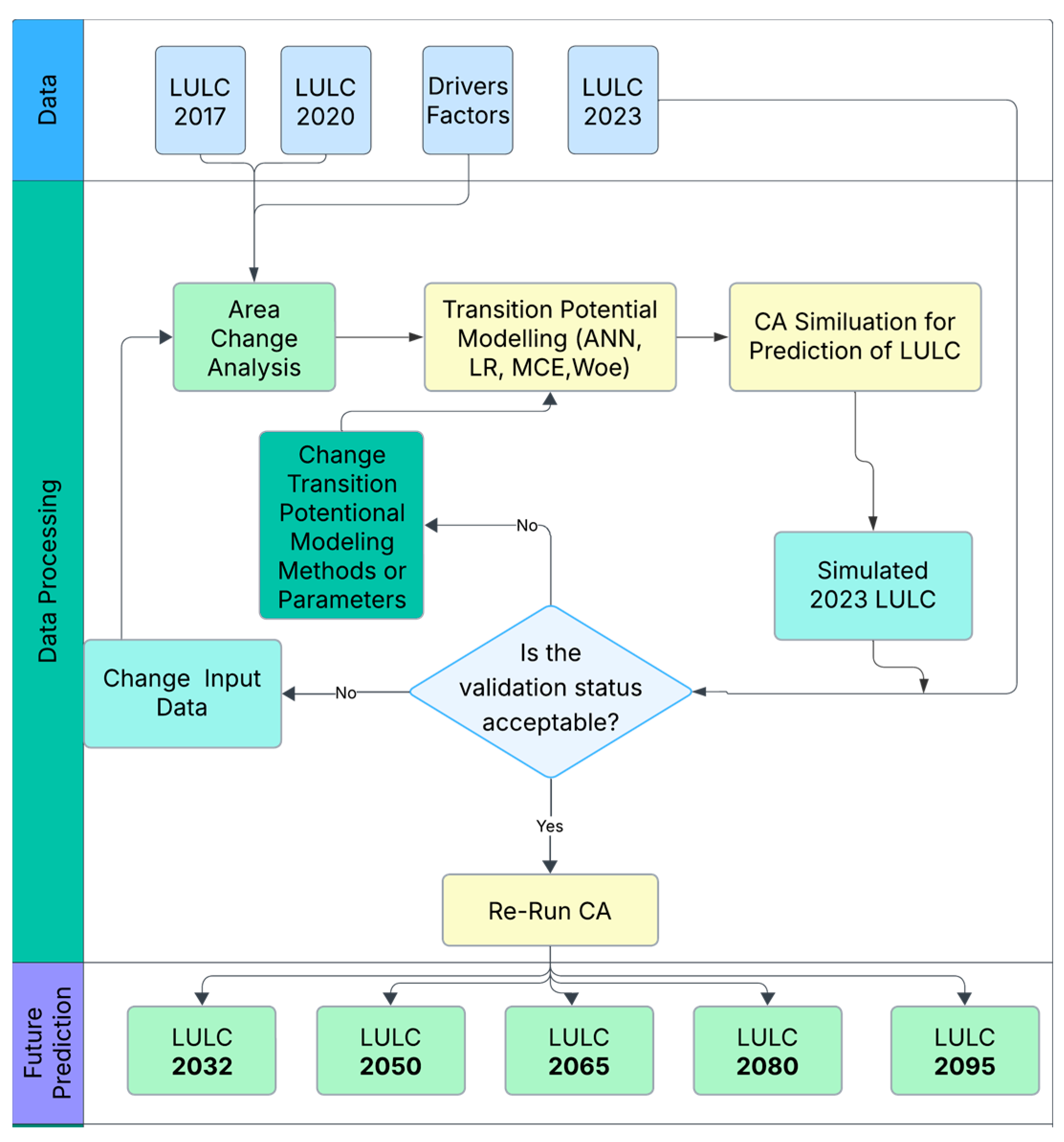

2.4. Land Use and Land Cover Projection

2.5. Carbon Emission

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Discussion of Research Methods

| 1 | 2 | m | Total of Row ni+ | |

| 1 | n11 | n12 | n1m | n1+ |

| 2 | n21 | n22 | n2m | n2+ |

| m | nm1 | nm2 | nmm | nk+ |

| Total of Column: n+j | n+1 | n+1 | n+1 | n |

| i: Rows—Classification j: Columns—References | ||||

3.2. Comparison with Existing Studies

3.3. Limitations

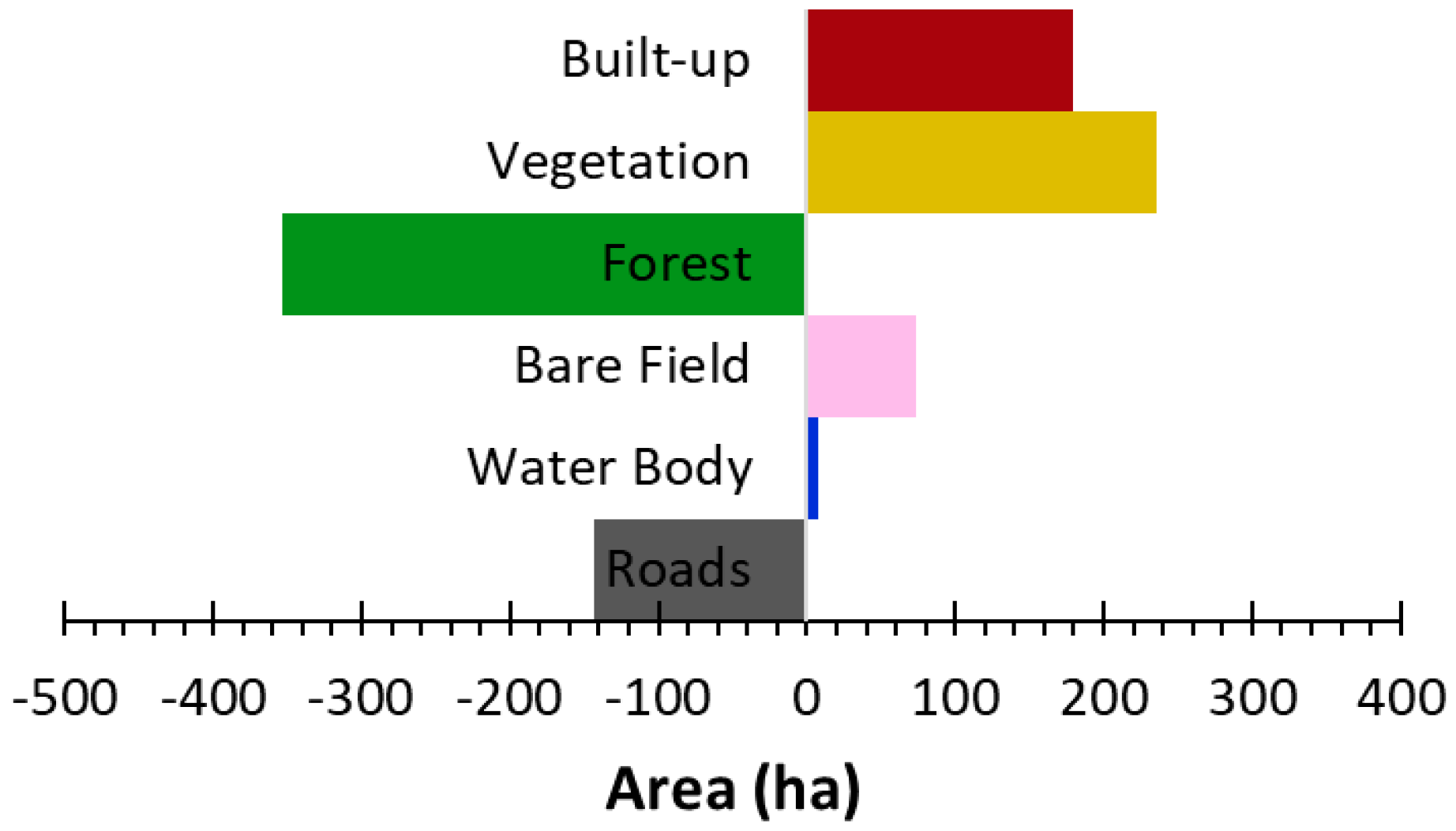

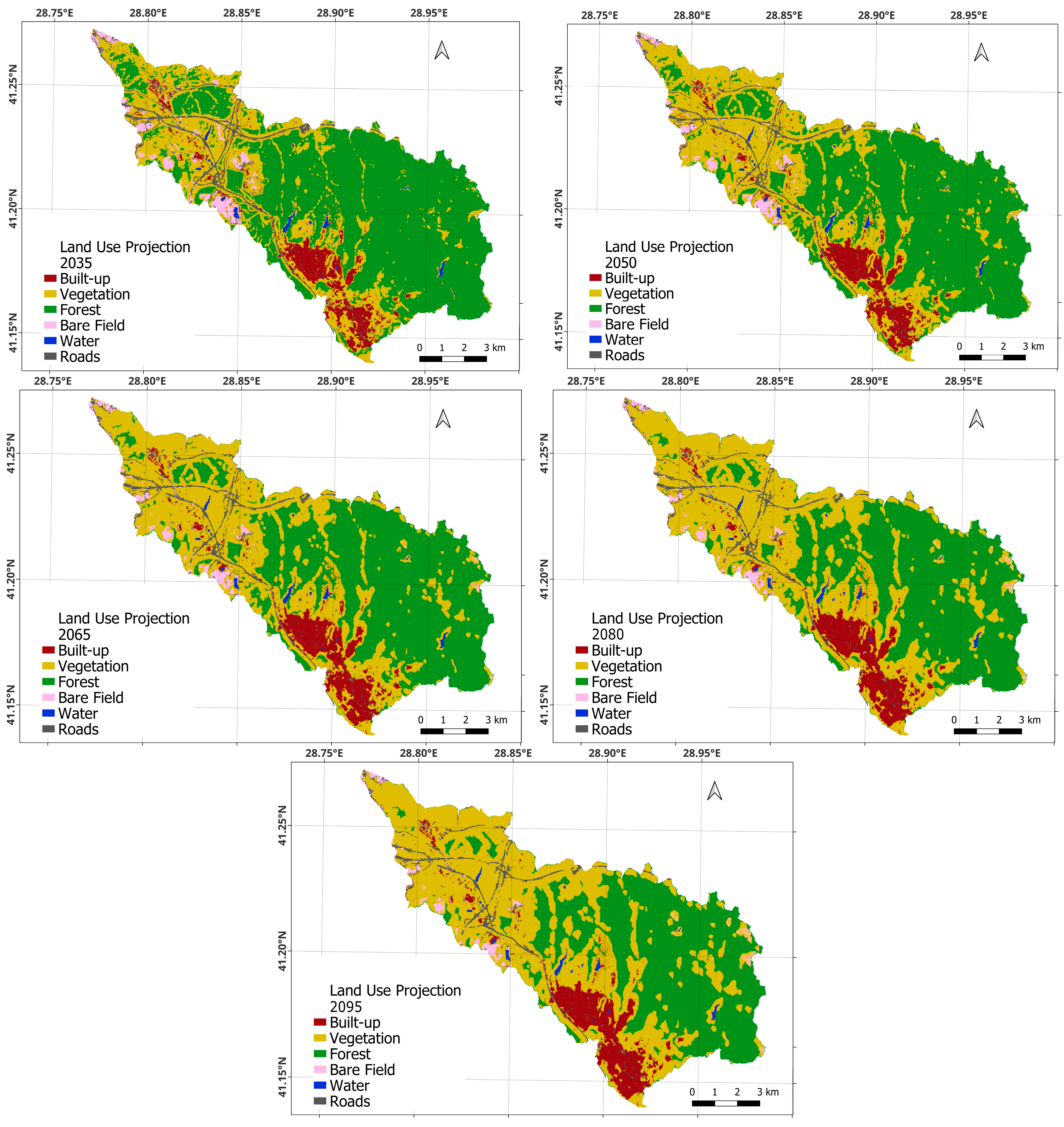

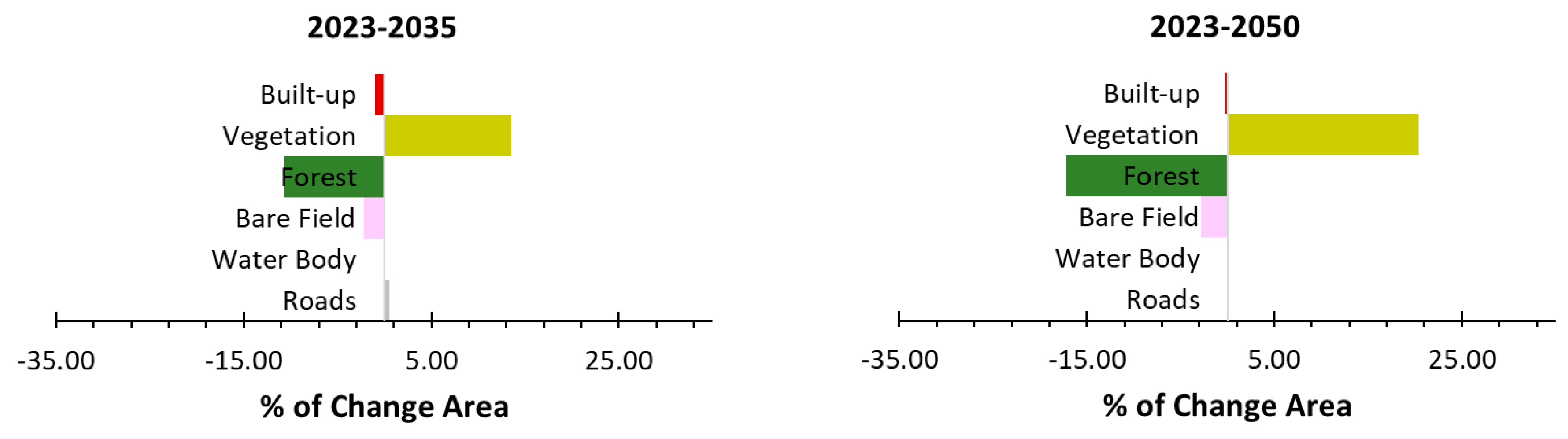

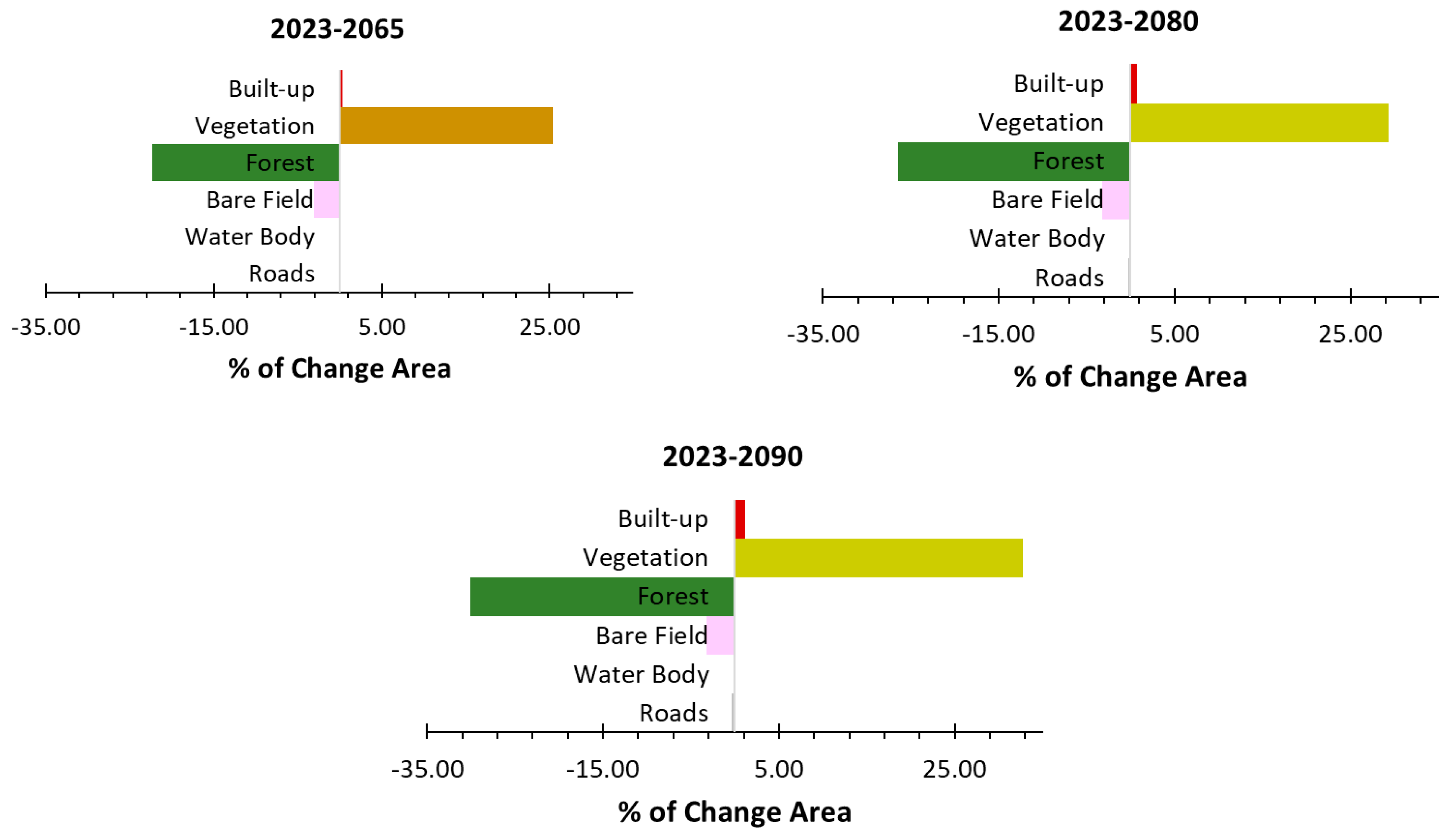

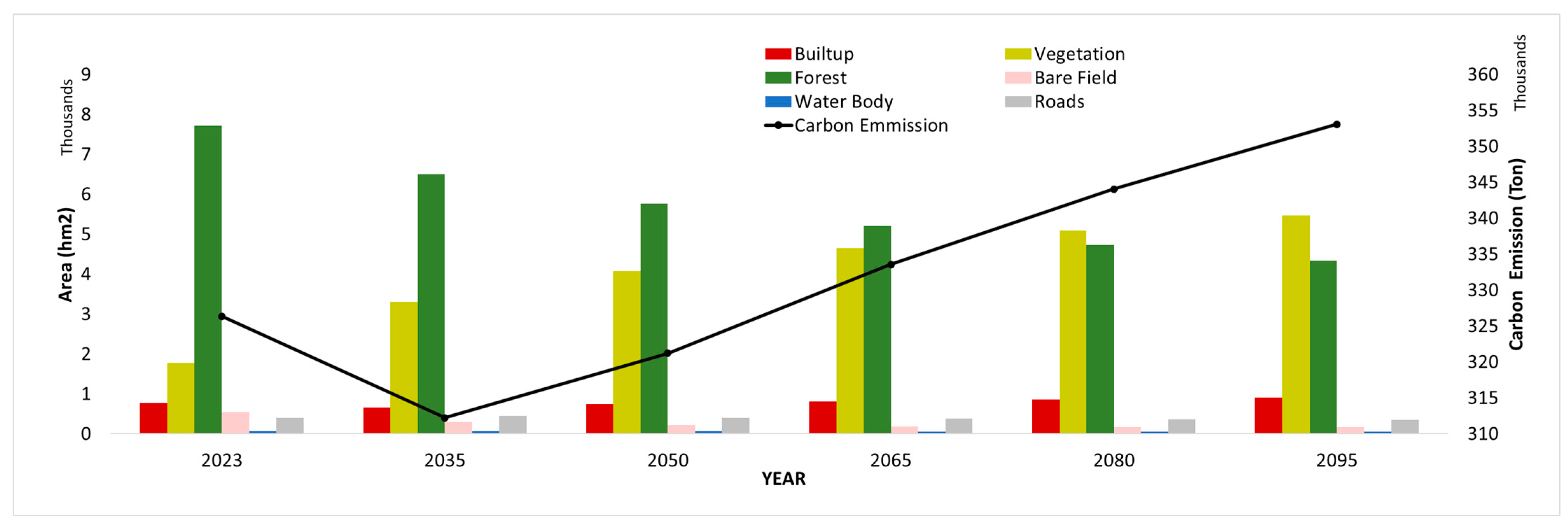

3.4. Future Projection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leeson, G.W. The Growth, Ageing and Urbanisation of Our World. J. Popul. Ageing 2018, 11, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Seto, K.C. Projecting Global Urban Land Expansion and Heat Island Intensification through 2050. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. TSI. Available online: https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=95&locale=tr (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hinge, G.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Goyal, M.K. Regional Carbon Fluxes from Land-Use Conversion and Land-Use Management in Northeast India. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2018, 22, 04018016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; He, J.; Hong, X.; Zhang, W.; Qin, C.; Pang, B.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Carbon Sources/Sinks Analysis of Land Use Changes in China Based on Data Envelopment Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Shen, L.; Liu, H. Grey Relational Analysis, Principal Component Analysis and Forecasting of Carbon Emissions Based on Long Short-Term Memory in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xing, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H. Sustainability Assessment of Coupled Human and Natural Systems from the Perspective of the Supply and Demand of Ecosystem Services. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 1025787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, E.D.; Olorunfemi, J.F.; Ifabiyi, I.P. Assessing the Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Osun Drainage Basin, Nigeria. J. Environ. Geogr. 2019, 12, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msovu, U.E.; Mulungu, D.M.M.; Nobert, J.K.; Mahoo, H. Land Use/Cover Change and Their Impacts on Streamflow in Kikuletwa Catchment of Pangani River Basin, Tanzania. Tanzan. J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 38, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.S.; Shapla, T.; Hossain, M.A.; Hasan, M.H. Delineating Agricultural Landuse Change Using Geospatial Techniques and Markov Model in the Tarakanda Upazila of Mymensingh, Bangladesh and Future Prediction. Dhaka Univ. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amgoth, A.; Rani, H.P.; Jayakumar, K.V. Exploring LULC Changes in Pakhal Lake Area, Telangana, India Using QGIS MOLUSCE Plugin. Spat. Inf. Res. 2023, 31, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Cheng, D.; Iqbal, J.; Yao, S. Spatiotemporal Change Analysis and Prediction of the Great Yellow River Region (GYRR) Land Cover and the Relationship Analysis with Mountain Hazards. Land 2023, 12, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, P.; Melesse, A.M.; Kenea, T.T. Prediction of Future Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using a Coupled CA-ANN Model in the Upper Omo–Gibe River Basin, Ethiopia. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.; Levinson, D.; El-Geneidy, A.; Wasfi, R. A Markov Chain Model of Land Use Change. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. TeMA 2015, 8, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, N.N.; Al Rakib, A.; Kafy, A.A.; Raikwar, V. Geospatial Modelling of Changes in Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics Using Multi-Layer Perception Markov Chain Model in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, C.M.; Batty, M.; Monteiro, A.M.V.; Câmara, G.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; Cerqueira, G.C.; Pennachin, C.L. Stochastic Cellular Automata Modeling of Urban Land Use Dynamics: Empirical Development and Estimation. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2003, 27, 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Ou, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Pei, F. A Future Land Use Simulation Model (FLUS) for Simulating Multiple Land Use Scenarios by Coupling Human and Natural Effects. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, N.; Liang, B.; Wang, Z.; Cressey, E.L. Spatial and Temporal Variation, Simulation and Prediction of Land Use in Ecological Conservation Area of Western Beijing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhu, D.; Yun, W. Simulation of Land Use Spatial Pattern of Towns and Villages Based on CA-Markov Model. Math. Comput. Model. 2011, 54, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, R.; Balzter, H.; Kolo, K. Predicting Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using a CA-Markov Model under Two Different Scenarios. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantz, C.A.; Goetz, S.J.; Shelley, M.K. Using the SLEUTH Urban Growth Model to Simulate the Impacts of Future Policy Scenarios on Urban Land Use in the Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan Area. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahiny, A.S.; Clarke, K.C. Guiding SLEUTH Land-Use/Land-Cover Change Modeling Using Multicriteria Evaluation: Towards Dynamic Sustainable Land-Use Planning. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2012, 39, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fioravante, P.; Luti, T.; Cavalli, A.; Giuliani, C.; Dichicco, P.; Marchetti, M.; Chirici, G.; Congedo, L.; Munafò, M. Multispectral Sentinel-2 and Sar Sentinel-1 Integration for Automatic Land Cover Classification. Land 2021, 10, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhar, A.; Hernández-López, D.; Ballesteros, R.; Moreno, M.A. Improving the Accuracy of Multiple Algorithms for Crop Classification by Integrating Sentinel-1 Observations with Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqe Ibrahim, G.R.; Rasul, A.; Abdullah, H. Improving Crop Classification Accuracy with Integrated Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data: A Case Study of Barley and Wheat. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2023, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukiou, G. SAR Features and Techniques for Urban Planning—A Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Chang, S.; Deng, Y.; Xue, F.; Wang, C.; Jia, X. Oriented SAR Ship Detection Based on Edge Deformable Convolution and Point Set Representation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hong, L.; Guo, J.; Zhu, A. Automated Extraction of Lake Water Bodies in Complex Geographical Environments by Fusing Sentinel-1/2 Data. Water 2022, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, V.; Deljouei, A.; Moradi, F.; Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Borz, S.A. Land Use and Land Cover Mapping Using Sentinel-2, Landsat-8 Satellite Images, and Google Earth Engine: A Comparison of Two Composition Methods. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, I.; Tonny, K.F.; Hoque, M.Z.; Abdullah, H.M.; Khan, B.M.; Islam, K.H.S.; Prodhan, F.A.; Ahmed, M.; Mohana, N.T.; Ferdush, J. Monitoring and Prediction of Land Use Land Cover Change of Chittagong Metropolitan City by CA-ANN Model. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 6275–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmy, M.W.A.; Gessler, P.E.; Hicke, J.A.; Salem, B.B. Land Use/Land Cover Change Detection and Prediction in the North-Western Coastal Desert of Egypt Using Markov-CA. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 63, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyandye, C.; Martz, L.W. A Markovian and Cellular Automata Land-Use Change Predictive Model of the Usangu Catchment. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqadhi, S.; Mallick, J.; Balha, A.; Bindajam, A.; Singh, C.K.; Hoa, P.V. Spatial and Decadal Prediction of Land Use/Land Cover Using Multi-Layer Perceptron-Neural Network (MLP-NN) Algorithm for a Semi-Arid Region of Asir, Saudi Arabia. Earth Sci. Inform. 2021, 14, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaraj, M.; Rangarajan, S. Predicting the Future Land Use and Land Cover Changes for Bhavani Basin, Tamil Nadu, India, Using QGIS MOLUSCE Plugin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 86337–86348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, R.; Zhang, W.; Abbas, Z.; Guo, F.; Gwiazdzinski, L. Spatiotemporal Change Analysis and Prediction of Future Land Use and Land Cover Changes Using QGIS MOLUSCE Plugin and Remote Sensing Big Data: A Case Study of Linyi, China. Land 2022, 11, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, B.; Manjunatha, B.R.; Bhat, H.G. Modeling Projected Impacts of Climate and Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Hydrological Responses in the Lake Tana Basin, Upper Blue Nile River Basin, Ethiopia. J. Hydrol. 2021, 595, 125974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirsaw, E.; Wu, W.; Shi, X.; Temesgen, H.; Bekele, B. Land Use/Land Cover Change Modeling and the Prediction of Subsequent Changes in Ecosystem Service Values in a Coastal Area of China, the Su-Xi-Chang Region. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admas, M.; Melesse, A.M.; Tegegne, G. Predicting the Impacts of Land Use/Cover and Climate Changes on Water and Sediment Flows in the Megech Watershed, Upper Blue Nile Basin. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Munkhnasan, L.; Lee, W.K. Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection and Prediction in Bhutan’s High Altitude City of Thimphu, Using Cellular Automata and Markov Chain. Environ. Chall. 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.M.Y.; Baja, S.; Rampisela, D.A.; Arif, S. Modelling Land Use/Land Cover Changes Prediction Using Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPNN): A Case Study in Makassar City, Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 78, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liping, C.; Yujun, S.; Saeed, S. Monitoring and Predicting Land Use and Land Cover Changes Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques—A Case Study of a Hilly Area, Jiangle, China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tantawi, A.M.; Bao, A.; Chang, C.; Liu, Y. Monitoring and Predicting Land Use/Cover Changes in the Aksu-Tarim River Basin, Xinjiang-China (1990–2030). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, S.; Kothari, M.K.; Tripathi, M.P.; Singh, P.K.; Bhakar, S.R.; Dave, V.; Jain, S.K. Spatiotemporal LULC Change Detection and Future Prediction for the Mand Catchment Using MOLUSCE Tool. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank Juma, O.; Shrinidhi, A.; Philista Adhiambo, M.; Hafez, A.; Qingmin, M.; Domnic Kiprono, C.; Kuria, A.; Yahia, S. Monitoring and Prediction of Land Use and Land Cover Using Remote Sensing and CA-ANN. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 102, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Devatha, C.P.; Azhoni, A. Integration of Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Network and Cellular Automata-Markov Chain Approach for the Prediction of Land Use Land Cover in Land Change Modeler. Ecol. Model. 2025, 506, 111162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, P.; Xia, J.; Wang, W.; Cai, W.; Chen, N.; Hu, S.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Zhan, C. Land Use/Land Cover Prediction and Analysis of the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River under Different Scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, H.İ. Land-Use Land-Cover Dynamics and Future Projections Using GEE, ML, and QGIS-MOLUSCE: A Case Study in Manisa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Space Agency (ESA). Harmonized Sentinel-2 MSI: MultiSpectral Instrument, Level-2A; European Space Agency (ESA): Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- JAXA. ALOS Global Digital Surface Model “ALOS World 3D—30m” (AW3D30); JAXA Data Report; JAXA: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between Leaf Chlorophyll Content and Spectral Reflectance and Algorithms for Non-Destructive Chlorophyll Assessment in Higher Plant Leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. NASA Special Publication. NASA Spec. Publ. 1974, 24, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- McFeeters, S.K. The Use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the Delineation of Open Water Features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Modification of Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI) to Enhance Open Water Features in Remotely Sensed Imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Gao, J.; Ni, S. Use of Normalized Difference Built-up Index in Automatically Mapping Urban Areas from TM Imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Wan, T.; Hao, H.; Lu, Q. Fusing High-Spatial-Resolution Remotely Sensed Imagery and OpenStreetMap Data for Land Cover Classification over Urban Areas. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a Green Channel in Remote Sensing of Global Vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, M.; Jayamanna, S.; Tsujiko, Y. Relation Between Social and Environmental Conditions in Colombo, Sri Lanka and the Urban Index Estimated by Satellite Remote Sensing Data. In Proceedings of the International Archives of Photogrammetry Remote Sensing, Vienna, Austria, 9–19 July 1996; Volume XXXI, pp. 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita, B.; Yang, W.; Chen, J.; Onda, Y.; Qiu, G. Sensitivity of the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to Topographic Effects: A Case Study in High-Density Cypress Forest. Sensors 2007, 7, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzekri, S.; Lasbet, A.A.; Lachehab, A. A New Spectral Index for Extraction of Built-Up Area Using Landsat-8 Data. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2015, 43, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyisa, G.L.; Meilby, H.; Fensholt, R.; Proud, S.R. Automated Water Extraction Index: A New Technique for Surface Water Mapping Using Landsat Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.D. Multi-SpectralWater Index (MuWI): A Native 10-m Multi-SpectralWater Index for Accuratewater Mapping on Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, T.B. NDVI, NDBI & NDWI Calculation Using Landsat 7,8. Geomat. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 2, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- EOS. NDVI Mapping in Agriculture, Index Formula, and Uses. Available online: https://eos.com/make-an-analysis/ndvi/ (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Ibrahim, M.; Ghanem, F.; Al-Salameen, A.; Al-Fawwaz, A. The Estimation of Soil Organic Matter Variation in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Using Remote Sensing Data. Int. J. Geosci. 2019, 10, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.C.; Kang, G.D.; Tsuruta, H.; Mosier, A. Estimate of CH4 Emissions from Year-Round Flooded Rice Fields During Rice Growing Season in China. Pedosphere 2005, 15, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Vinuya, F.; DiFurio, F.; Sandoval, E. A Decomposition Analysis of CO2 Emissions in the United States. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2010, 17, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, D.; He, H.; Liu, C.; Han, S. Spatio-Temporal Dynamic Evolution of Carbon Emissions from Land Use Change in Guangdong Province, China, 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Deng, X. Correlation Modelling between Land Surface Temperatures and Urban Carbon Emissions Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study. Phys. Chem. Earth 2023, 132, 103489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Kasimu, A.; Reheman, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Aizizi, Y.; Liang, H. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Prediction of Carbon Emissions/Absorption from Land Use Change in the Urban Agglomeration on the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Mountains. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, X. Path Analysis and Mediating Effects of Influencing Factors of Land Use Carbon Emissions in Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 188, 122268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlı, M. The Effect of Istanbul Land Use on the Carbon Emissions; Istanbul Technical University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Story, M.; Congalton, R.G. Accuracy Assessment: A User’s Perspective. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1986, 52, 397–399. [Google Scholar]

- Congalton, R.G.; Green, K. Assessing the Accuracy of Remotely Sensed Data Principles and Practices, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beniger, J.R.; Bishop, Y.M.M.; Feinberg, S.E.; Holland, P.W.; Light, R.J.; Mosteller, F. Discrete Multivariate Analysis: Theory and Practice. Contemp. Sociol. 1975, 4, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perović, V.; Jakšić, D.; Jaramaz, D.; Koković, N.; Čakmak, D.; Mitrović, M.; Pavlović, P. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Land Use/Land Cover Change and Its Effects on Soil Erosion (Case Study in the Oplenac Wine-Producing Area, Serbia). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aneesha Satya, B.; Shashi, M.; Deva, P. Future Land Use Land Cover Scenario Simulation Using Open Source GIS for the City of Warangal, Telangana, India. Appl. Geomat. 2020, 12, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Band | Pixel Size | Wavelength | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 60 m | 443.9 nm (S2A)/442.3 nm (S2B) | Aerosols |

| B2 | 10 m | 496.6 nm (S2A)/492.1 nm (S2B) | Blue |

| B3 | 10 m | 560 nm (S2A)/559 nm (S2B) | Green |

| B4 | 10 m | 664.5 nm (S2A)/665 nm (S2B) | Red |

| B5 | 20 m | 703.9 nm (S2A)/703.8 nm (S2B) | Red Edge 1 |

| B6 | 20 m | 740.2 nm (S2A)/739.1 nm (S2B) | Red Edge 2 |

| B7 | 20 m | 782.5 nm (S2A)/779.7 nm (S2B) | Red Edge 3 |

| B8 | 10 m | 835.1 nm (S2A)/833 nm (S2B) | NIR |

| B8A | 20 m | 864.8 nm (S2A)/864 nm (S2B) | Red Edge 4 |

| B9 | 60 m | 945 nm (S2A)/943.2 nm (S2B) | Water vapor |

| B11 | 20 m | 1613.7 nm (S2A)/1610.4 nm (S2B) | SWIR 1 |

| B12 | 20 m | 2202.4 nm (S2A)/2185.7 nm (S2B) | SWIR 2 |

| Class | 2017 | 2020 | 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UD | PA | UD | PA | UD | PA | |

| Built-up | 1.000 | 0.984 | 0.969 | 1.000 | 0.984 | 0.954 |

| Vegetation | 1.000 | 0.954 | 1.000 | 0.971 | 1.000 | 0.955 |

| Forest | 0.966 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.986 | 1.000 |

| Bare fields | 0.985 | 0.970 | 0.955 | 0.955 | 0.921 | 1.000 |

| Water bodies | 1.000 | 1.0000 | 0.984 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Roads | 0.963 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.984 | 0.985 | 0.970 |

| 2020 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Built-up | Vegetation | Forest | Bare Field | Water Body | Roads | |

| Built-up | 61.6% | 18.5% | 0.2% | 7.9% | 0.1% | 11.8% | |

| Vegetation | 10.3% | 75.9% | 3.6% | 6.6% | 0.1% | 3.5% | |

| Forest | 0.3% | 5.6% | 93.4% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.2% | |

| Bare field | 8.8% | 24.0% | 0.0% | 48.9% | 2.6% | 15.6% | |

| Water Body | 1.4% | 2.0% | 2.1% | 2.1% | 87.7% | 4.7% | |

| Roads | 11.2% | 9.5% | 0.0% | 12.2% | 0.5% | 66.5% | |

| 2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Built-up | Vegetation | Forest | Bare Field | Water Body | Roads | |

| Built-up | 64.2% | 23.4% | 0.8% | 8.0% | 0.0% | 3.5% | |

| Vegetation | 7.2% | 72.1% | 14.8% | 4.7% | 0.0% | 1.2% | |

| Forest | 0.1% | 1.8% | 97.8% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Bare field | 13.6% | 15.9% | 0.0% | 64.8% | 0.5% | 5.2% | |

| Water Body | 0.8% | 3.0% | 5.6% | 2.4% | 83.5% | 4.8% | |

| Roads | 25.1% | 7.7% | 0.2% | 11.4% | 0.3% | 55.2% | |

| 2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Built-up | Vegetation | Forest | Bare Field | Water Body | Roads | |

| Built-up | 62.7% | 21.5% | 0.6% | 8.8% | 0.1% | 6.4% | |

| Vegetation | 11.9% | 70.5% | 7.2% | 8.3% | 0.1% | 2.0% | |

| Forest | 0.3% | 4.6% | 94.1% | 0.7% | 0.1% | 0.2% | |

| Bare field | 12.3% | 29.1% | 0.3% | 46.6% | 2.8% | 9.0% | |

| Water Body | 1.4% | 5.1% | 4.5% | 3.8% | 78.3% | 6.8% | |

| Roads | 24.9% | 9.9% | 0.2% | 15.4% | 0.4% | 49.2% | |

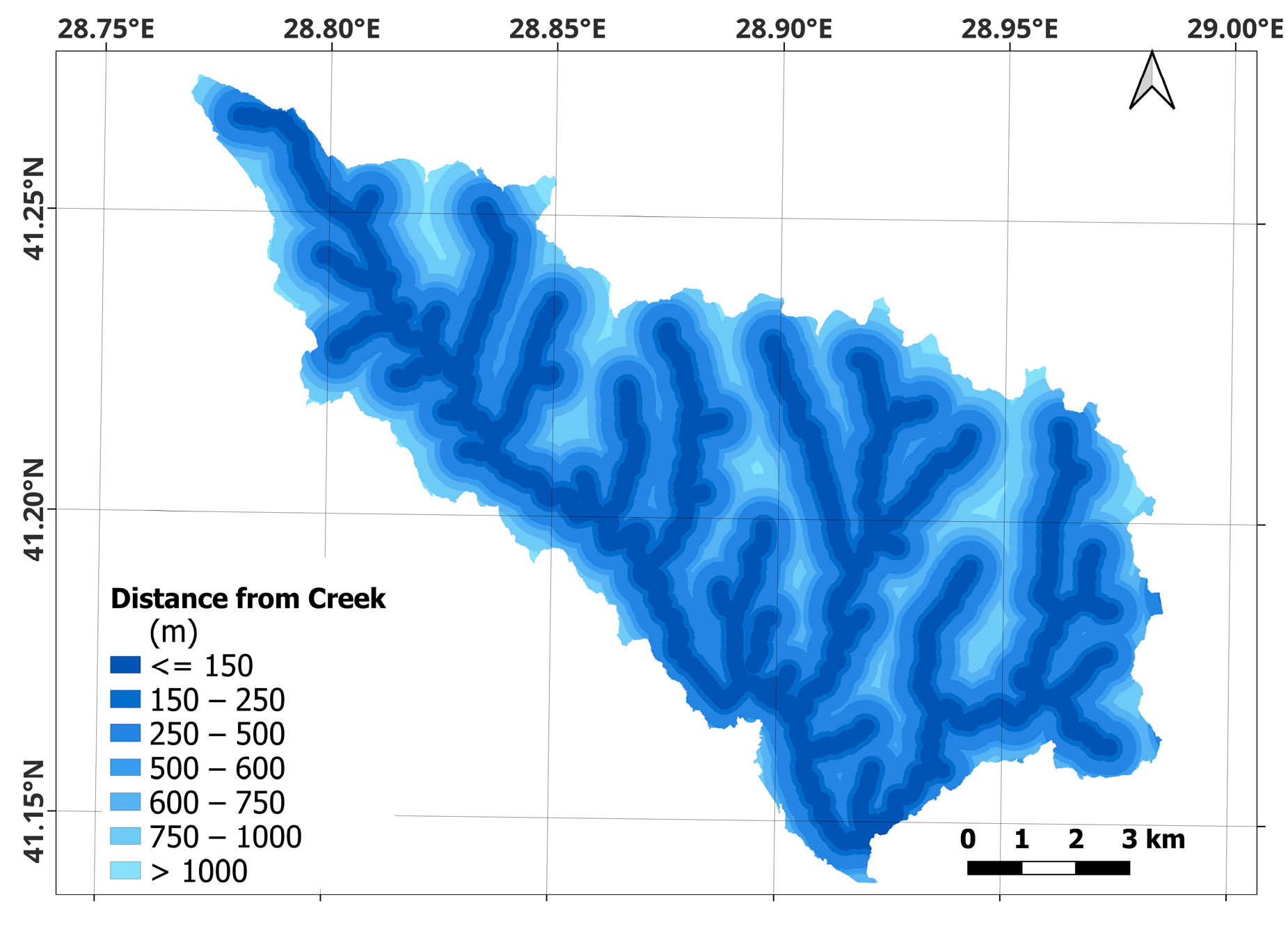

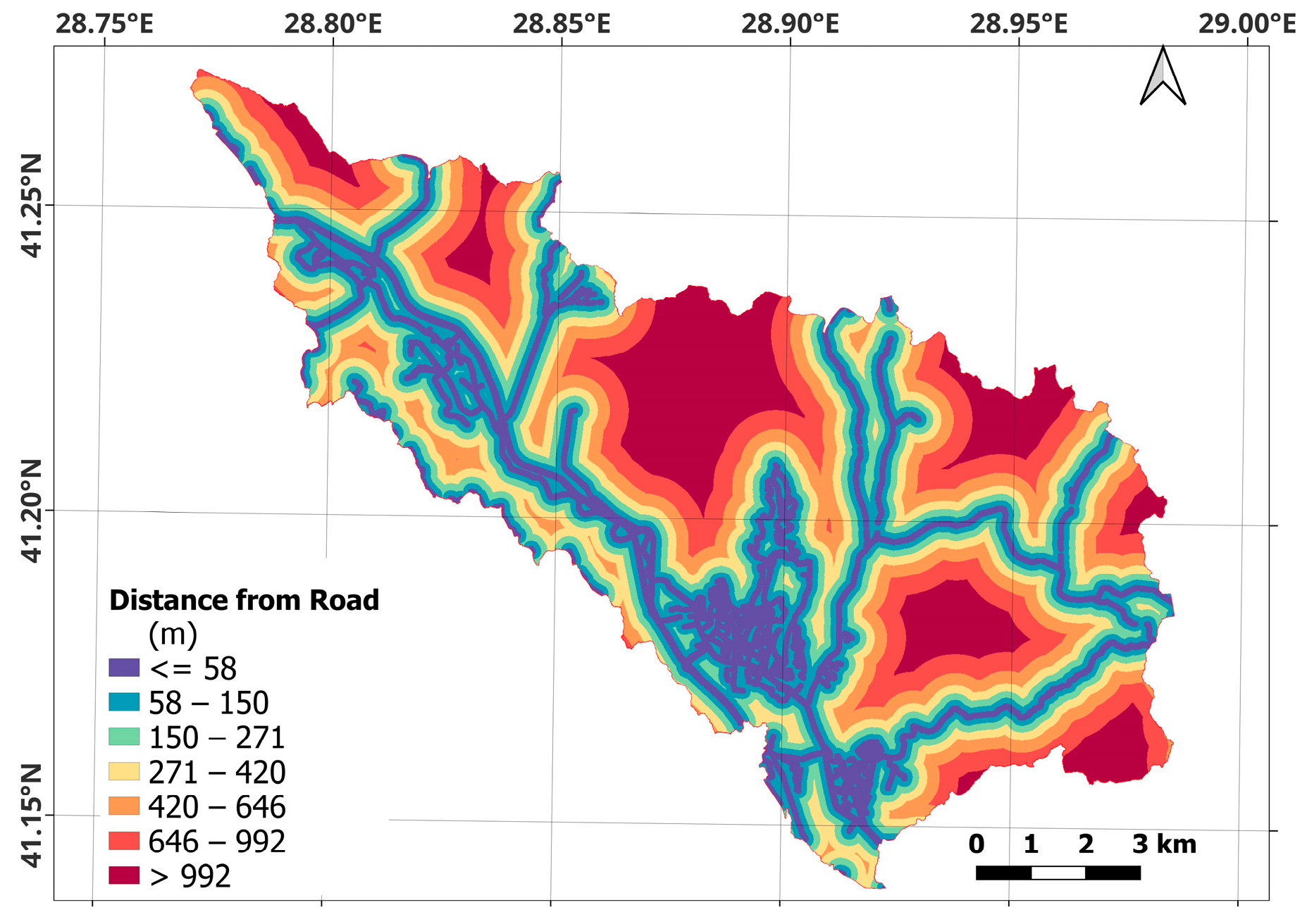

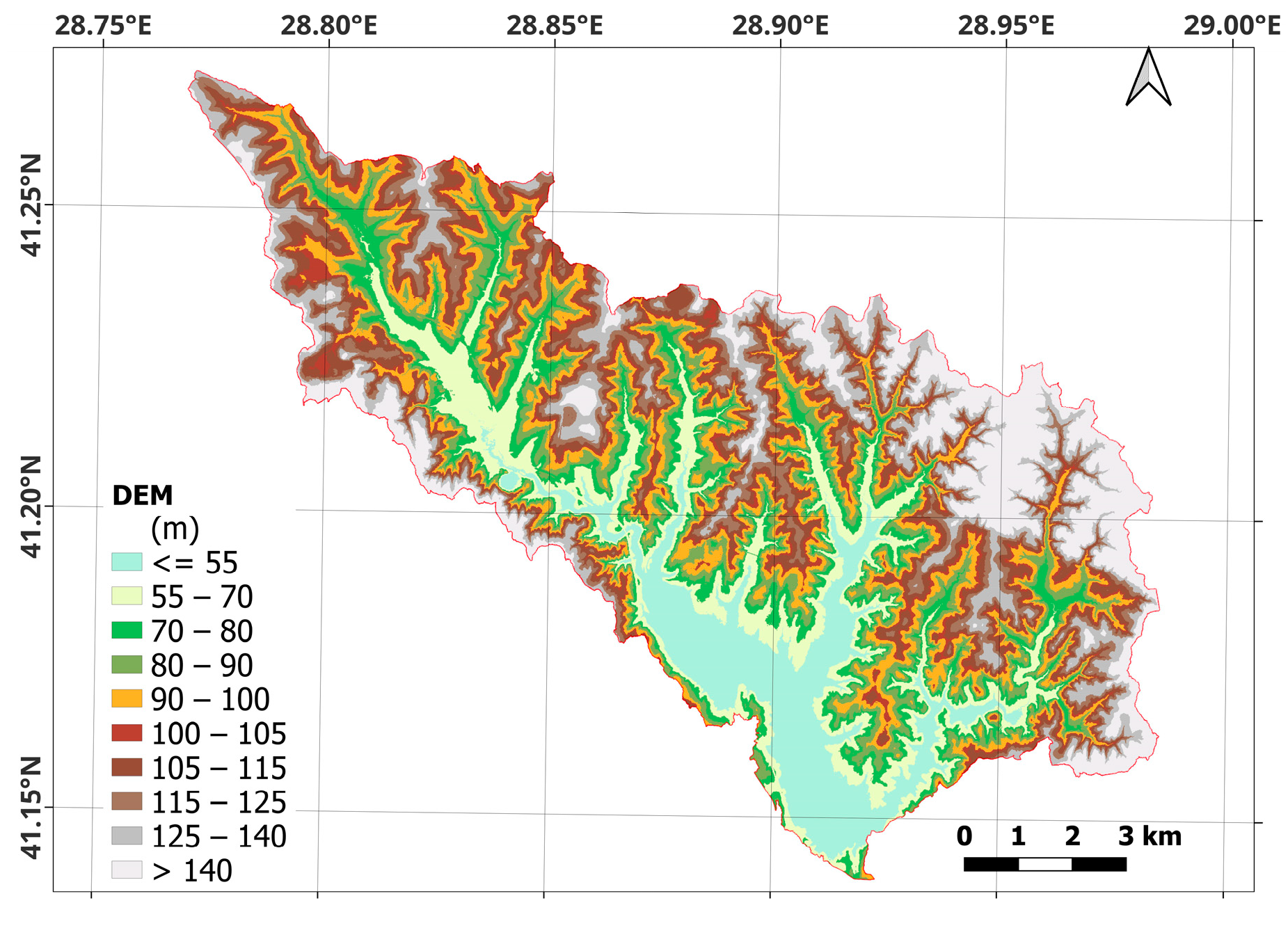

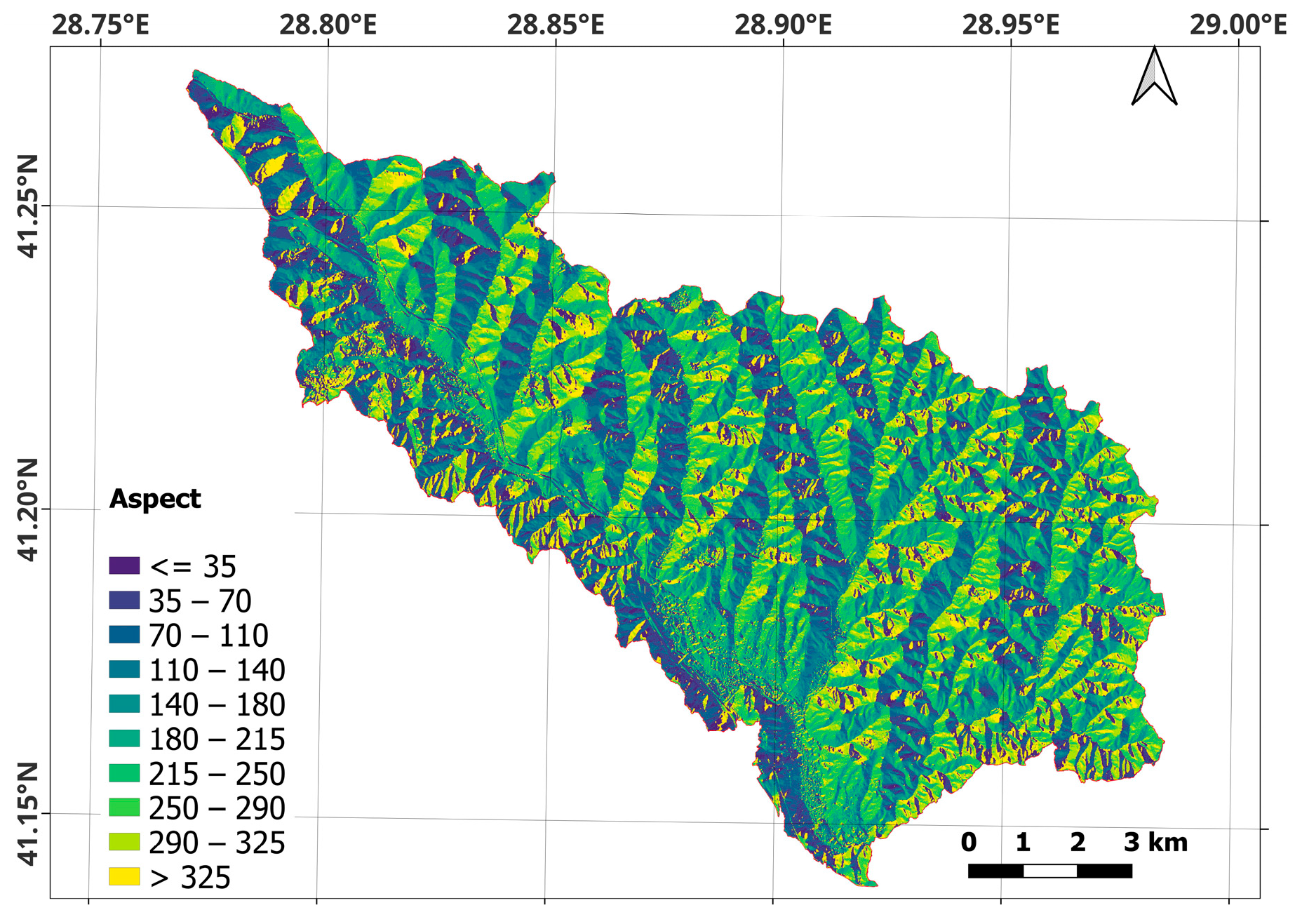

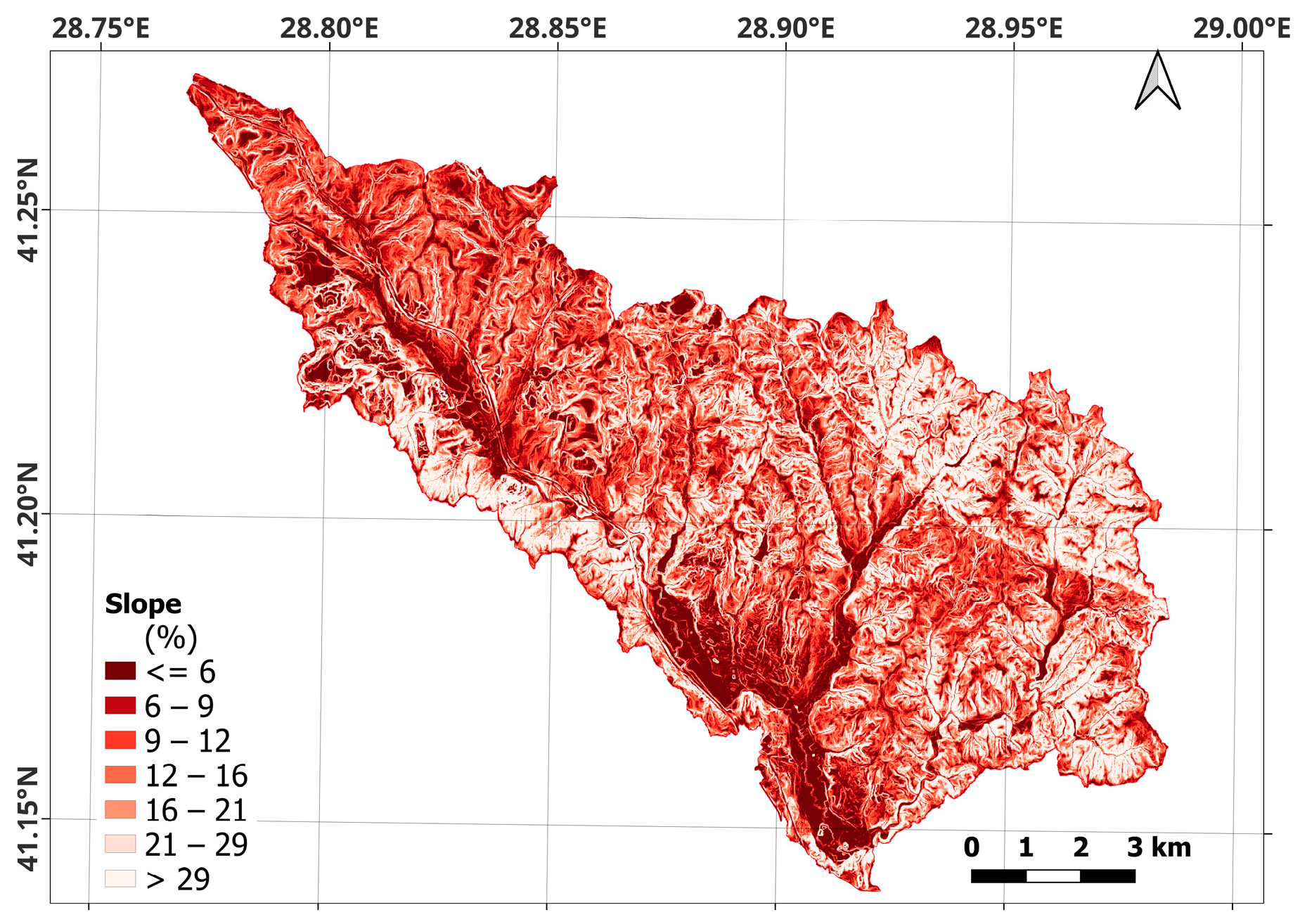

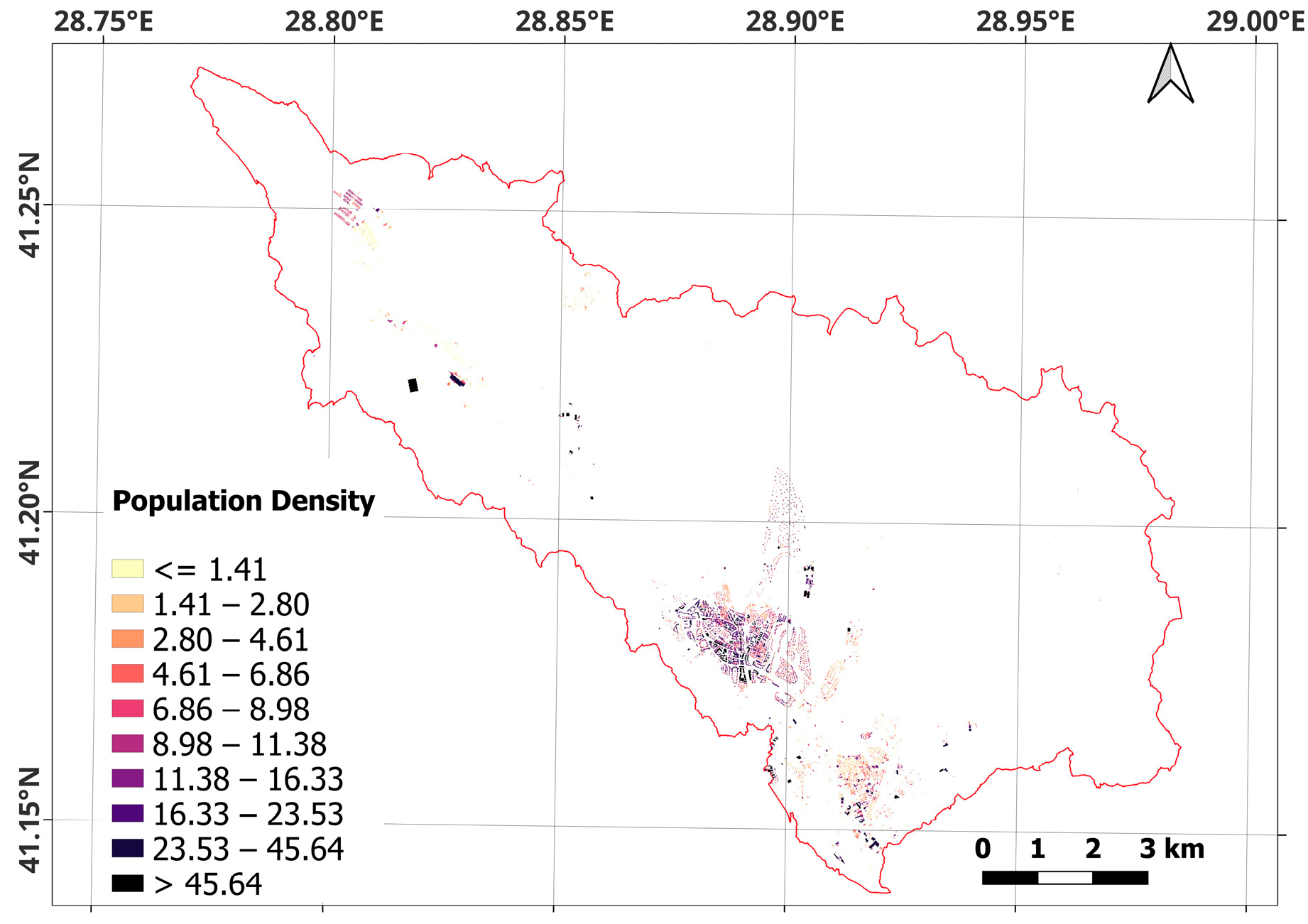

| Spatial Variable (Driving) Factors | Scenarios | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

| Population Density | X | X | |||

| Distance from the Creeks | X | X | X | ||

| Distance from the Roads | X | X | X | ||

| Digital Elevation Model | X | X | X | X | X |

| Aspect | X | X | |||

| Slope | X | X | |||

| Scenarios Name | % Kappa Correctness | Kappa (Overall) Coefficients | Kappa (Histo) Coefficients | Kappa (loc) Coefficients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 91.8850 | 0.8420 | 0.9036 | 0.9319 |

| S2 | 86.9675 | 0.7451 | 0.8932 | 0.8342 |

| S3 | 86.1678 | 0.7318 | 0.8898 | 0.8224 |

| S4 | 87.1769 | 0.7482 | 0.9218 | 0.8116 |

| S5 | 86.3784 | 0.7343 | 0.8834 | 0.8313 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kocaman, B.; Ağaçcıoğlu, H. Assessment of the Impact of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Carbon Emissions Using Remote Sensing and Deep Learning: A Case Study of the Kağıthane Basin. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310690

Kocaman B, Ağaçcıoğlu H. Assessment of the Impact of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Carbon Emissions Using Remote Sensing and Deep Learning: A Case Study of the Kağıthane Basin. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310690

Chicago/Turabian StyleKocaman, Bülent, and Hayrullah Ağaçcıoğlu. 2025. "Assessment of the Impact of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Carbon Emissions Using Remote Sensing and Deep Learning: A Case Study of the Kağıthane Basin" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310690

APA StyleKocaman, B., & Ağaçcıoğlu, H. (2025). Assessment of the Impact of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Carbon Emissions Using Remote Sensing and Deep Learning: A Case Study of the Kağıthane Basin. Sustainability, 17(23), 10690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310690