1. Introduction

Digital transformation has become a central component of contemporary public sector reform and is often presented as a path toward a more efficient, transparent, and citizen-oriented administration [

1]. Digitalization of public organizations involves redesigning processes, procedures, structures, and services so that new technologies become fully institutionalized within organizational routines [

2,

3,

4]. Research shows that digital transformation reshapes work practices, alters communication patterns, transforms organizational structures and cultures, and redefines how public value is created and delivered [

5]. For this reason, digital transformation is increasingly understood as a long-term organizational and institutional process that requires continuous learning, flexibility, and sustained governance capacity.

At the same time, public administrations face a dual pressure. Societies expect innovative and responsive digital services, while fiscal and managerial constraints push organizations toward efficiency, cost reduction, and performance [

6]. Under these conditions, sustaining digital transformation over time becomes challenging. The sustainability agenda reflected in SDG 16 emphasizes the need for effective, accountable, and inclusive public institutions, highlighting the importance of maintaining public value and organizational capacity throughout digital reform processes [

7]. Achieving sustainable digital transformation requires institutions capable of adaptation, innovation, and coordinated governance [

8,

9,

10].

However, as organizations undergo digital transformation, a new form of organizational pathology has emerged: digital red tape, which refers to dysfunctional rules and regulations that create compliance burdens through their integration with digital technology [

11]. Compared to private entities, public organizations face greater legal and public accountability, often have conflicting goals, and operate under more bureaucratic structures [

12]. These characteristics may amplify the complexities introduced by digital transformation. Evidence from traditional red tape research shows that dysfunctional rules undermine managerial support, restrict autonomy, suppress innovation cultures, and generate frustration, stress, and exhaustion [

13,

14,

15,

16]. When such dynamics become embedded in digital infrastructures, their effects may be intensified as digital procedures are far less flexible and difficult to adapt or circumvent. These pressures weaken organizational learning, experimentation, and adaptability, which are essential for sustaining digital transformation over time.

Research on digital red tape has grown in recent years, mostly within WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) contexts. Existing studies show that digital tools can generate new rule burdens and exacerbate rule dysfunction; for example, those arising from digital HR systems [

17,

18], university research robotic administration platforms [

19], or digital accounting technologies [

20]. Yet the empirical base remains concentrated in WEIRD contexts, and systematic evidence from non-WEIRD administrative systems is still limited, particularly regarding internal digital red tape as experienced by public employees within organizations. In addition, the role of hierarchical position in shaping perceptions of digital red tape remains insufficiently understood. Classic studies of red tape have long shown that organizational position shapes perceptions of rules [

21,

22]. Senior managers tend to view rules as instruments of coordination and accountability, whereas frontline officials often experience them as obstacles to effective service delivery. However, it remains unclear whether these hierarchical differences persist, or perhaps even deepen, in the digital era, particularly within administrative systems characterized by steep bureaucratic hierarchies such as China’s. To address this gap, this study investigates four questions using a two-wave survey design in China: (1) Do systematic differences in perceived digital red tape persist? (2) How do structural features, particularly formalization and centralization, relate to perceived digital red tape? (3) Do these structural effects vary across different bureaucratic echelons? (4) What are the implications of these patterns for the sustainability of digital transformation in public organizations? While the two-wave design helps reduce common method concerns, the analysis focuses on associative and predictive relationships rather than establishing strong causal effects.

This study makes four main contributions by addressing the research questions outlined above. First, it extends the organizational echelon perspective to the context of digital governance by examining hierarchical differences in perceived digital red tape. Second, it provides empirical evidence from China on how formalization and centralization relate to digital red tape. Third, it demonstrates that these structural effects vary across bureaucratic echelons, clarifying how bureaucratic echelons shape the implementation and consequences of digital governance. Finally, by situating the analysis within China’s bureaucratic system, the study contributes a non-WEIRD perspective that broadens comparative debates on digital transformation and highlights the implications of these patterns for the long-term sustainability of digital transformation in public organizations.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and develops the conceptual hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the data and research methods.

Section 4 presents the empirical results.

Section 5 discusses the implications of the findings, outlines the study’s limitations, and suggests avenues for future research.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The survey targeted employees in Chinese public organizations across different areas. Data were collected through the Credamo online platform, which allows stratified sampling by occupation and demographics. To ensure data quality, only participants with credibility and approval scores above 60% could join, each IP address was restricted to one submission, and responses were monitored for reliability. To reduce potential common method bias, both procedural and statistical remedies were applied. Following Podsakoff et al. (2003) [

70], the study adopted a temporal separation and response anonymity design in which independent and dependent variables were measured at two points separated by about two months, both completed anonymously. Although organizational structure was measured at Wave 2 and digital red tape at Wave 1, both constructs are expected to be stable over short periods, so this sequencing functions as a procedural remedy for common method bias rather than implying temporal causality. Attention-check items were embedded in both waves, and those failing the checks or responding unrealistically fast were removed. The anonymous and non-evaluative design further reduced evaluation apprehension and social desirability bias [

71]. Data collection took place from November 2024 to March 2025. All participants were informed about confidentiality and voluntarily consented to follow-up participation. At Time 1, 565 questionnaires were received; after screening, 550 valid responses remained. At Time 2, 456 responses were collected, and after excluding four invalid cases, a total of 452 matched questionnaires were retained for analysis. China’s public administration operates within a five-tier hierarchy consisting of the central, provincial, municipal, county, and township levels.

3.2. Measures

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and organizational characteristics of the 452 valid respondents, and

Table 2 provides an overview of the constructs, sources, and sample items (the full questionnaire appears in

Appendix A). All scales were adapted from well-established instruments and demonstrate satisfactory to excellent reliability and validity, and the variance inflation factors show no meaningful multicollinearity among the predictors (see

Appendix B,

Table A1 and

Table A2). For context, China’s public administration follows a five-tier hierarchy comprising the central, provincial, municipal, county, and township levels. This structure underpins the bureaucratic echelon variable used in the analyses and informs the stratified comparisons reported later.

Digital red tape. Digital red tape was measured using a validated 12-item Digital Red Tape Scale [

72]. The instrument builds on Van Loon et al. (2016)’s Job-Centered Red Tape Scale [

73] and includes two dimensions: digital compliance burden (7 items) and digital functionality deficiency (5 items). The scale has been validated through standard scale-development procedures in multiple samples from Chinese public organizations. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.92 for the full scale, 0.91 for digital compliance burden, and 0.84 for digital functionality deficiency.

Formalization. Organizational formalization was measured using items adapted from DeHart-Davis et al. (2013, 2014) [

74,

75] and Kaufmann et al. (2019) [

47]: “In my organization, how many of the rules can be described as written rules?” Response options ranged from None to All (None, Very few, Some, Many, All). Although concise, this item has been repeatedly validated as an effective proxy for rule codification in related studies. The item was translated and back-translated following standard procedures.

Centralization. Organizational centralization was measured with three items adapted from Aiken and Hage (1968) [

45], Kaufmann et al. (2019) [

47] (e.g., “Even for small matters, I must seek my supervisor’s approval”), rated on a seven-point scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), also translated and back-translated for use in the Chinese context.

Control variables. Gender, age, education, job level, years in service, region, and bureaucratic echelon were included as control variables. In particular, the bureaucratic echelon was coded into five ordered categories (township, county, municipal, provincial, and central) for descriptive statistics. For stratified analyses and coefficient plots, these categories were collapsed into three administrative tiers: lower (township and county), middle (municipal), and upper (provincial and central) to ensure adequate cell sizes and interpretability.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 452).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 452).

| Variable | Category | n | Percent |

|---|

| Gender | Female | 267 | 59.10% |

| Male | 185 | 40.90% |

| Age | 21–30 | 246 | 54.40% |

| 31–40 | 149 | 33% |

| 41–50 | 38 | 8.40% |

| 51–60 | 18 | 4% |

| >60 | 1 | 0.20% |

| Education | Junior college or below | 23 | 5.10% |

| Undergraduate | 281 | 62.20% |

| Postgraduate | 148 | 32.70% |

| Bureaucratic echelon | Township level | 71 | 15.70% |

| County level | 177 | 39.20% |

| Municipal level | 160 | 35.40% |

| Provincial level | 36 | 8% |

| Central level | 8 | 1.80% |

| Job level | Principal leader | 4 | 0.90% |

| Middle manager | 53 | 11.70% |

| Frontline manager | 126 | 27.90% |

| Frontline staff | 269 | 59.50% |

| Years in service | <1 years | 36 | 8% |

| 1–3 years | 147 | 32.50% |

| 4–6 years | 88 | 19.50% |

| 7–10 years | 80 | 17.70% |

| 11–15 years | 49 | 10.80% |

| 16–20 years | 16 | 3.50% |

| >21 years | 36 | 8% |

| Region | Eastern region | 234 | 51.80% |

| Central region | 100 | 22.10% |

| Western region | 86 | 19% |

| Northeastern region | 32 | 7.10% |

Table 2.

Measurements.

| Construct | Source | Subdimension | Sample Item * | Wave |

|---|

| Digital red tape | Van Loon et al. (2016) [73] | Digital compliance burden | Implementation of new digital systems consumes excessive work time | 1 |

| Digital functionality deficiency | Technical support is timely and effective (R) |

| Formalization | DeHart-Davis et al. (2013) [74], DeHart-Davis et al. (2014) [75], Kaufmann et al. (2019) [47] | | In my organization, how many of the rules can be described as written rules?

(Response options: None, Very few, Some, Many, All) | 2 |

| Centralization | Aiken and Hage (1968) [45], Kaufmann et al. (2019) [47] | | In my organization, before doing anything, I almost always have to ask my supervisor for instructions. | 2 |

3.3. Analytical Approach

The analysis proceeded in two main stages to examine both overall patterns and administrative tier variations in digital red tape. First, one-way ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests were conducted to assess group differences in digital red tape and its two dimensions, digital compliance burden and digital functionality deficiency, across demographic and organizational categories. Second, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with HC3 robust standard errors were estimated to evaluate how formalization and centralization are associated with digital red tape, controlling for gender, age, education, years in service, bureaucratic echelon, job level, and region. To assess hierarchical heterogeneity, the models were re-estimated separately for upper-echelon (central and provincial), middle-echelon (municipal), and lower-echelon (county and township) organizations. This comparison will illustrate how the relationships between organizational structure and digital red tape vary across hierarchical levels within China’s multilevel administrative system. It is important to note that we were not able to collect organizational identifiers, which prevents us from formally modeling potential clustering of respondents within the same organizations. Additionally, because the upper-echelon subsample is small (n = 44), we were unable to conduct multi-group CFA to assess measurement invariance across echelons. All OLS models use HC3 robust standard errors to mitigate small-sample bias in variance estimation, and these methodological constraints are further discussed in the limitations.

4. Results

The reliability and validity of all multi-item constructs were examined prior to hypothesis testing. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.84 to 0.92, exceeding the 0.70 benchmark, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. Composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.84 to 0.91, and average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.48 to 0.71, meeting the recommended cut-off values for convergent validity [

76]. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) further demonstrated good measurement properties for the three-factor model of digital compliance burden, digital functionality deficiency, and centralization (χ

2/df = 2.16, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.969, RMSEA = 0.051, SRMR = 0.032). These results confirm that the measurement model achieved satisfactory reliability and validity. The detailed reliability and validity results (Cronbach’s α, AVE, and CR) are provided in

Appendix B.

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables (

n = 452). Digital red tape (Mean = 2.91, SD = 0.83) is positively correlated with both digital compliance burden (r = 0.78,

p < 0.001) and digital functionality deficiency (r = 0.52,

p < 0.001), confirming their conceptual relatedness yet empirical distinctiveness. Centralization (r = 0.37,

p < 0.001) and formalization (r = 0.21,

p < 0.001) are also positively correlated with digital red tape, while correlations among the control variables remain moderate, suggesting no multicollinearity concerns.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, minimum, maximum, and correlations (n = 452).

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, minimum, maximum, and correlations (n = 452).

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|

| 1 | Digital red tape | 2.91 | 0.833 | 1.167 | 4.75 | 1 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 2 | Digital compliance burden | 2.733 | 0.903 | 1 | 4.75 | 0.780 *** | 1 | | | | | | | | | | |

| 3 | Digital functionality deficiency | 2.11 | 0.661 | 1 | 4.5 | 0.524 *** | 0.502 *** | 1 | | | | | | | | | |

| 4 | Gender | 0.409 | 0.492 | 0 | 1 | −0.049 | −0.028 | −0.006 | 1 | | | | | | | | |

| 5 | Age | 1.626 | 0.818 | 1 | 5 | −0.171 *** | −0.189 *** | −0.161 *** | 0.139 ** | 1 | | | | | | | |

| 6 | Education | 2.277 | 0.55 | 1 | 3 | 0.068 | 0.077 | 0.114 * | −0.100 * | −0.169 *** | 1 | | | | | | |

| 7 | Years in service | 3.334 | 1.656 | 1 | 7 | −0.152 ** | −0.171 *** | −0.151 ** | 0.115 * | 0.867 *** | −0.201 *** | 1 | | | | | |

| 8 | Bureaucratic echelon | 2.409 | 0.907 | 1 | 5 | −0.206 *** | −0.145 ** | −0.081 + | 0.031 | 0.003 | 0.213 *** | 0.039 | 1 | | | | |

| 9 | Job level | 3.46 | 0.733 | 1 | 4 | 0.114 * | 0.138 ** | 0.145 ** | −0.161 *** | −0.471 *** | −0.003 | −0.476 *** | −0.110 * | 1 | | | |

| 10 | Region | 1.814 | 0.979 | 1 | 4 | 0.018 | 0.026 | 0.019 | −0.021 | 0.051 | −0.044 | 0.037 | 0.033 | −0.01 | 1 | | |

| 11 | Centralization | 2.957 | 1.06 | 1 | 5 | 0.371 *** | 0.323 *** | 0.266 *** | −0.02 | −0.088 + | 0.067 | −0.135 ** | −0.109 * | 0.125 ** | −0.056 | 1 | |

| 12 | Formalization | 3.573 | 0.73 | 1 | 5 | 0.207 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.035 | 0.001 | 0.084 + | 0.041 | 0.028 | 0.312 *** | 1 |

4.1. Group Differences in Digital Red Tape

The ANOVA (see

Appendix C) and Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests revealed significant group differences in digital red tape and its two dimensions (

Table 4). Regarding overall digital red tape, employees aged 31–40 and 41–50 reported significantly lower perceptions than those aged 21–30, suggesting that younger public servants tend to feel more constrained by digital procedures. Moreover, significant differences appeared across bureaucratic echelon. Digital red tape was higher among township and county governments than at the municipal and provincial levels, indicating that bureaucratic obstacles are more salient in lower administrative tiers.

For digital compliance burden, similar age-related patterns emerged. Employees in their thirties and forties experienced lower compliance burdens than the youngest group. Additionally, those with 7–10 years of service reported lower burdens than newcomers, implying that organizational experience helps employees adapt to digital procedures. Job position also mattered: frontline staff perceived higher digital compliance burdens than middle managers, with a gap of around 0.35 points that reflects meaningful positional disparities in exposure to digital administrative requirements.

Finally, for digital functionality deficiency, significant differences appeared by both age and job level. Middle managers perceived fewer digital functionality problems than frontline staff, with an average gap of about 0.31 points, consistent with their greater access to organizational support and technical resources

Overall, the significant group differences cluster around a few core characteristics. Younger employees consistently report higher levels of digital red tape and its subdimensions. Staff in township and county governments also perceive markedly higher burdens than those in municipal and provincial units, reflecting stratification across the bureaucratic echelon. Frontline employees show a similar pattern, reporting more compliance and functionality problems than middle managers. Other characteristics, including education, region, and years in service, display only limited or context-specific differences. Taken together, these patterns suggest that age, bureaucratic echelon, and job position are the categories in which perceptions of digital red tape diverge most clearly in our data.

4.2. Structural Effects on Digital Red Tape

Across the full sample, both formalization and centralization exerted positive and significant effects on digital red tape (

Table 5). Higher levels of rule codification were associated with stronger perceptions of procedural burden and inefficiency, indicating that rigidly written rules tend to amplify digital constraints. Formalization showed significant effects on the overall index (B = 0.150,

p < 0.01) and on digital functionality deficiency (B = 0.082,

p < 0.05), suggesting that excessive procedural specification may reduce the adaptability of digital systems. These results support H1, which posited a positive relationship between organizational formalization and digital red tape. Centralization displayed an even more robust and consistent pattern across all models (

p < 0.001), confirming that hierarchical decision concentration increases employees’ sense of digital red tape by limiting discretion in digital workflows. This finding strongly supports H2, demonstrating that centralization functions as a dominant structural driver of digital red tape. Among the control variables, younger and less educated employees reported higher levels of digital red tape, while those working in lower bureaucratic echelons tended to experience greater digital compliance burden.

To assess whether the structural effects vary across bureaucratic echelons in H3, we first estimated multiplicative interaction models, but the interaction terms were not statistically significant (

Appendix D,

Table A3). A coefficient plot is also provided for transparency (

Appendix D,

Figure A1). However, some methodological work cautions that such non-significance should not be taken as evidence of no heterogeneity, because interaction estimates are often fragile under strong functional-form assumptions, limited common support, and sensitivity to model specification [

77,

78]. In our data, the upper echelon contains only 44 observations, further limiting the power to detect interaction effects. Following these cautions, we therefore supplement the interaction models with separate OLS regressions estimated for upper, middle, and lower echelons (

Table 6).

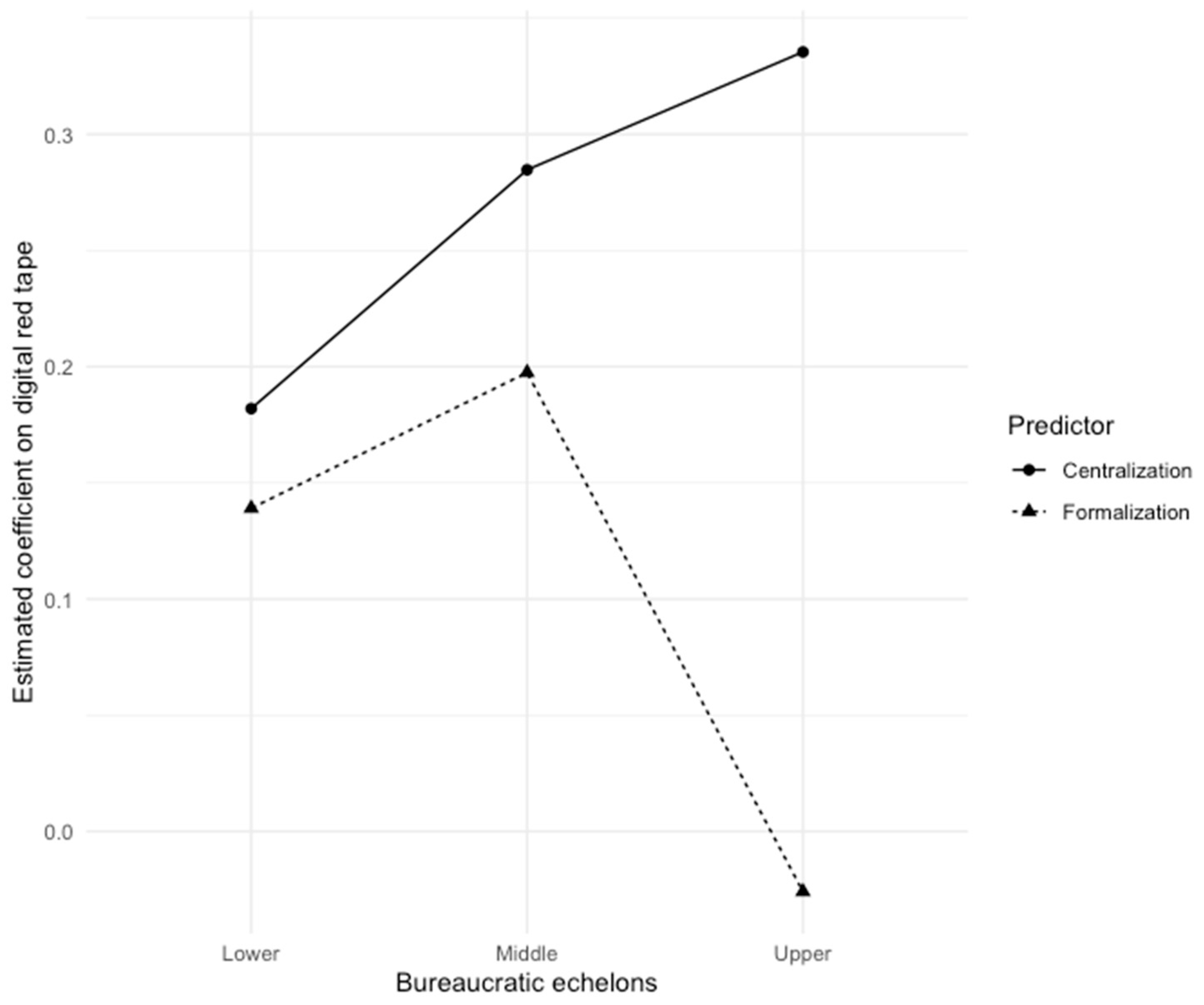

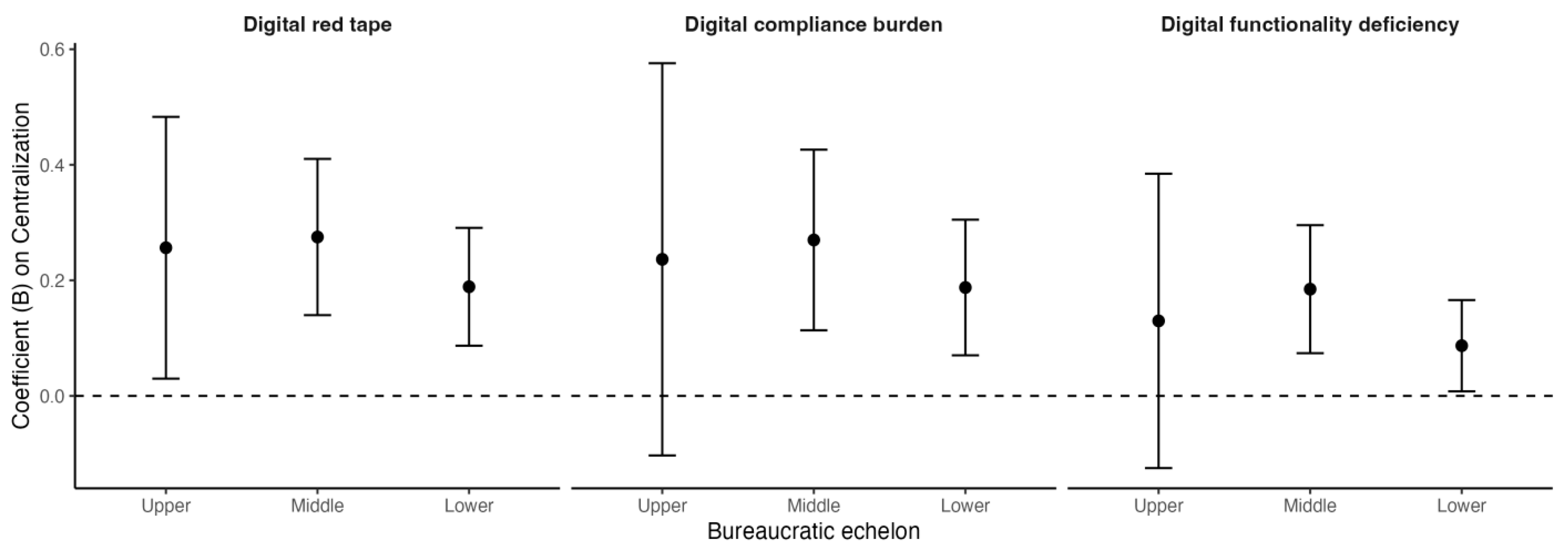

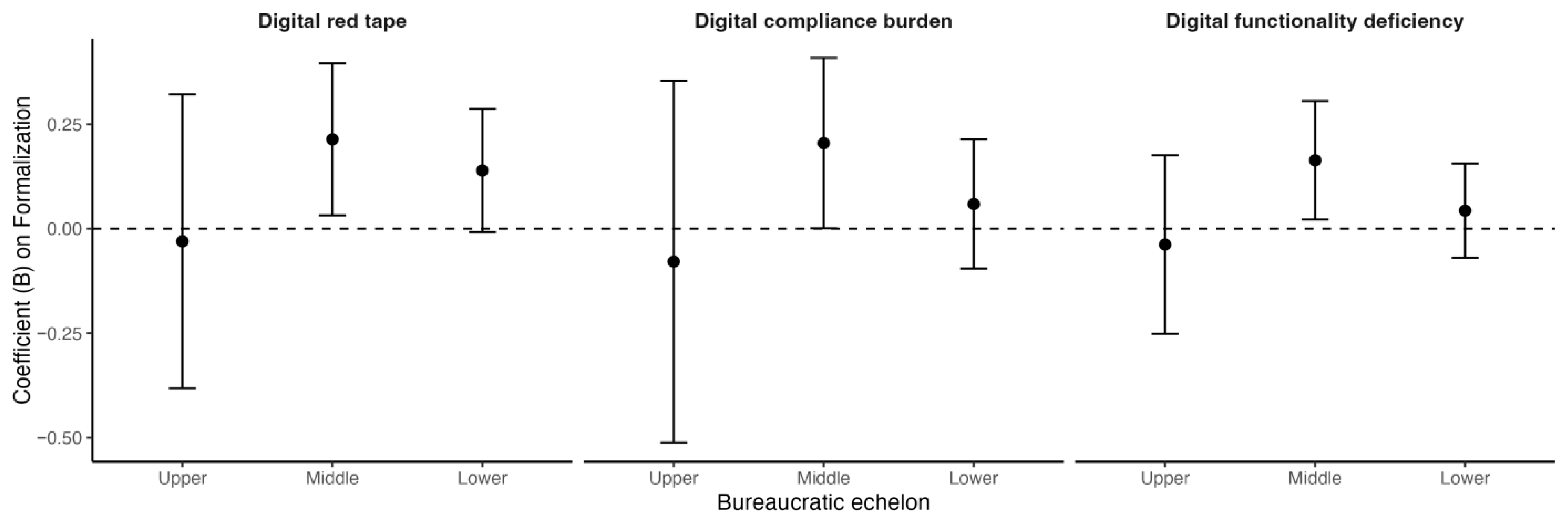

The echelon-specific regressions indicate different patterns across bureaucratic echelons. In upper-echelon organizations (

n = 44), formalization is not associated with digital red tape, whereas centralization shows a positive and statistically significant coefficient for the overall index. In middle-echelon organizations (

n = 160), both formalization and centralization are positively associated with digital red tape across all three outcomes, with centralization exhibiting comparatively larger standardized coefficients. In lower-echelon organizations (

n = 248), centralization remains positive and significant, while formalization shows a modest association for the overall index but is not statistically significant for the two subdimensions. These patterns, which are also reflected in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, indicate variation in the estimated magnitude of structural effects across bureaucratic echelons even though the formal interaction test did not reach statistical significance. Taken together, the results provide descriptive rather than confirmatory evidence of heterogeneous structural effects and offer partial support for H3.

Overall, the results offer clear evidence that both formalization and centralization are positively associated with digital red tape in Chinese public organizations, providing full support for H1 and H2. The additional heterogeneity analysis yields a more nuanced picture. Although the formal interaction test does not yield statistical significance, the echelon-specific regressions and coefficient plots indicate differences in the estimated magnitudes of structural effects. In middle-echelon organizations, both formalization and centralization are positively associated with all three outcomes, with centralization showing comparatively larger standardized coefficients. In lower-echelon organizations, centralization remains positive and significant across outcomes, whereas formalization shows only a modest association with the overall index. These descriptive patterns point to possible variation across echelons. Thus, the findings offer descriptive rather than statistical support for H3, indicating only partial support for the proposed heterogeneity.

5. Discussion

This study makes three theoretical contributions. First, ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests reveal that significant differences in perceived digital red tape are concentrated among younger employees, frontline staff, and those working in lower-level governments, rather than dispersed across many background characteristics. This indicates a patterned rather than scattered structure of variation in how employees experience digital constraints. Younger and less experienced staff reported significantly higher perceptions of digital constraints, which perhaps reflects their limited tenure and position in the organizational hierarchy, making them more sensitive to procedural rigidity. Employees in lower job positions also perceived stronger digital compliance burden and digital functionality deficiency than those in managerial roles. Such disproportionate burdens on frontline and early-career employees may undermine two foundations of sustainable digital development: employee well-being and the capacity for continuous innovation [

79,

80,

81]. These findings are consistent with prior evidence that red tape perceptions vary across organizational echelons [

21,

22]. Extending this logic to a non-WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) setting [

82], the results indicate that hierarchical variation in bureaucratic experience persists in the digital era. Such intra-organizational differences provide a micro-level foundation for understanding how bureaucratic hierarchy more broadly shapes digital red tape.

Second, significant differences also emerge across bureaucratic echelons within China’s administrative hierarchy. Employees in lower-echelon organizations reported higher levels of digital red tape than those in upper echelons. This pattern reflects the cascading nature of control in the Chinese bureaucracy, where lower-level organizations face tighter supervision, heavier reporting requirements, and fewer opportunities for discretion. This result provides a context-specific contribution by showing that perceptions of digital red tape in China are shaped by a vertically stratified bureaucratic system in which hierarchical distance from decision-making centers amplifies feelings of rigidity and burden. This pattern is consistent with Zhou and Lian’s (2020) [

66] control-rights model of Chinese bureaucracy, which depicts authority cascading downward through principal-supervisor-agent relationships. Within such a system, middle and lower levels face dual pressures of implementing upper-level mandates and enduring intensified digital supervision, making them most susceptible to the burdens of digital red tape. Digital procedures that exhibit functionality deficiencies or impose excessive compliance burdens can reduce service responsiveness and erode public trust, thereby undermining the long-term sustainability of digital transformation [

4,

83]. Taken together, these results demonstrate that digital red tape arises from the interaction between hierarchical control and technological embeddedness, reflecting a socio-technical tension in which the distribution of authority shapes how digital systems are perceived and experienced.

Third, the structural analysis identifies centralization as the primary organizational source of digital red tape, whereas the influence of formalization is weaker and more context-dependent. Across all models, higher levels of centralization consistently heighten perceptions of both compliance burden and functionality deficiency. The echelon-specific regression models also provide descriptive indications that these associations may vary across hierarchical levels. Although such patterns should be interpreted cautiously given the non-significant interaction terms and the small upper-echelon subsample. These findings offer theoretical insight into how structural features shape employees’ experiences with digital procedures. When decision-making authority is concentrated at upper levels, frontline and lower-echelon employees have limited discretion to interpret or adapt digital processes, which makes digital oversight feel rigid. The role of formalization is weaker and less consistent, but the descriptive patterns suggest why its effects may be experienced differently across hierarchical layers. Middle echelons often occupy the intersection of upward compliance and downward supervision. This dual position requires them to translate formalized rules from upper levels while also enforcing them on frontline staff, which may make the constraining aspects of formalization more visible in this layer even if the statistical interaction terms are not significant.

Moreover, codified and standardized rules do not inherently generate digital red tape. Their negative effects arise mainly in settings where digital supervision and bureaucratic control intersect most intensely, aligning with Adler and Borys (1996)’s distinction between enabling and coercive bureaucracies [

50]. This perspective also helps clarify why digital rules that are essential for safeguarding accountability, cybersecurity and privacy may still feel restrictive when embedded in coercive, highly centralized structures, whereas the same rules can function as supportive coordination mechanisms in more enabling environments. At the same time, structural features such as formalization, centralization and hierarchy also serve essential governance purposes by promoting accountability, transparency and predictability, even when they create procedural burdens [

47]. Digital red tape therefore represents only one dimension of organizational functioning and should be viewed within the broader trade-off between control and flexibility.

The findings also offer several practical implications for sustainable digital transformation from the perspective of digital red tape. First, because perceptions of digital red tape, including functionality deficiencies and excessive compliance burdens, are concentrated among frontline and lower-level employees rather than spread evenly across the bureaucracy, public organizations need to monitor how digital procedures affect these groups in order to maintain the long-term sustainability of digital transformation. Second, reducing unnecessary digital constraints is essential for building a more resilient and adaptable digital governance system. Excessive centralization may harden digital procedures and limit the discretion of middle and lower-level units, suggesting the value of greater localized configuration rights, periodic reviews of outdated or duplicative digital rules, and more flexible workflow arrangements. Third, the results indicate that public organizations need to differentiate digital rules that provide essential safeguards for cybersecurity, privacy, and accountability from those that impose avoidable burdens or exhibit functionality deficiencies, including repetitive reporting requirements or systems that are difficult to operate and therefore encourage workarounds. Clearer distinctions between these two types of rules can help managers retain necessary controls while preventing the accumulation of harmful digital red tape. Finally, incorporating user co-creation, frontline participation, and iterative feedback into system design, together with balancing quantitative digital indicators with qualitative assessments, can help public organizations reduce the build-up of coercive digital red tape and maintain a more sustainable trajectory for digital transformation.

Despite these insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although the two-wave design helps reduce simultaneity concerns and provides preliminary temporal leverage, the short interval between waves limits the ability to capture the dynamic evolution of digital red tape. Second, because the data rely on self-reported measures for both independent and dependent variables, common source bias cannot be entirely ruled out [

43,

84]. Third, the absence of organizational identifiers prevents the use of multilevel modeling to account for between-organization variance; future research with such identifiers would enable random-intercept or random-slope models to more precisely examine structural effects across organizations. Fourth, the interaction terms in the multiplicative interaction models are not statistically significant. Given the small upper-echelon subsample and the sensitivity of interaction models to specification, the heterogeneity we observe should be treated as descriptive rather than definitive. Future research should more directly examine the downstream consequences of digital red tape for innovation, employee well-being, public trust and the long-term sustainability of digital transformation, using multi-source or administrative data and cross-national, multilevel or longitudinal designs to strengthen causal inference and assess the generalizability of these relationships.