Abstract

Hat Yai Municipality is an urbanized city in the south of Thailand that is pursuing the goal of increasing the proportion of green space. However, it is limited by insufficient data on green space in Hat Yai. This is in part due to unclear definitions of green spaces in Thai spatial planning policy. This research aims to identify, classify, and compile a comprehensive database of urban green space in Hat Yai to support sustainable development objectives and to assess the usefulness of the Thai Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP) framework for doing so. Using aerial photo interpretation and field surveys to create accurate geospatial data of public green spaces in Hat Yai, 4.16 square kilometers of green space was identified, constituting 19.81% of the total area of the municipality. The findings are classified into six types of green spaces based on functionality. This data can be used as a baseline for future green space strategy.

1. Introduction

Green spaces bring multiple benefits to urban areas and help make cities more sustainable and more resilient to climate risks. Green spaces, such as parks, gardens, and forests, help cities to sequester carbon and contribute to flood risk mitigation by intercepting and retaining rainfall. Green spaces can reduce ambient temperature to combat the urban heat island effect, improve air quality, and provide habitats to enhance urban biodiversity [1]. Urban green spaces enhance the livability of a city by providing a setting for social interaction, relaxation, exercise, and community activities, thereby contributing to the physical and mental wellbeing and satisfaction of residents [2,3,4]. The importance of enhancing human settlements and urban areas through the development of green public spaces is highlighted by international development frameworks such as the New Urban Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [5], which advocate for cities to “provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, particularly for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities”. Despite these known benefits and international commitments, many cities, including those in Thailand, face challenges in expanding and maintaining green spaces.

While green space has gained interest in planning policy in cities in Thailand, and the concept of sustainability has been integrated into national economic and policy development plans [6], there is no centralized policy on developing urban green spaces specifically. Green spaces in Thailand have not grown proportionally with urban areas and infrastructure, leading to a shortage of green spaces in urban environments, which is exacerbated as increased urbanization leads to a rise in property value [7].

Hat Yai Municipality, the focus of this research, has the vision of becoming a green city. In 2017, the municipality created a Green City Action Plan, which includes the goal of increasing the proportion of green spaces in the city from 36% to 40% [8]. There are various challenges to this goal, such as increasing urban land prices, limited availability of public land, and a lack of accurate data on existing green spaces. The prioritization of economic growth over green space development further complicates these efforts, as the city is focused on becoming a regional commercial hub [9].

This research aims to support Hat Yai Municipality’s green city goals by using remote sensing and surveys to develop a comprehensive database of green spaces in Hat Yai that is aligned with Thai planning definitions, thus providing accurate data that can be used by policymakers for future urban planning and environmental management. This research also examines the usefulness of the green space framework of the Thai Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP) for classifying the functional diversity of urban green spaces identified in Hat Yai Municipality. The study aims to determine the extent to which the application of the ONEP use-based classification framework provides an appropriate and actionable basis for developing a green space database that supports strategic policymaking and high-quality environmental management in a rapidly urbanizing Thai municipality. This research will provide valuable insights to support Hat Yai’s green city objectives and contribute to the broader discourse on the suitability of the framework for understanding and developing urban green spaces elsewhere in Thailand.

Literature Review

Green spaces are an important infrastructure in cities that contribute to addressing challenges such as climate adaptation while also providing spaces for recreation, social interaction, and cultural activities, which support public health and social equity [1]. International agendas such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development underscore the importance of “safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces” as part of sustainable urban development [5]. Given these benefits, green spaces are critical for the sustainability of rapidly urbanizing cities in the Global South, which may be more focused on economic interests and accommodating housing needs than investing in developing green spaces. In Thailand, while sustainability is part of national plans [6] and SDG reporting [7], green space provision has not kept pace with urban expansion, contributing to deficits in many urban municipalities. Conceptual frameworks on how green spaces can be defined and classified are essential for informing planners and policymakers on how green spaces can be developed in cities.

The definitions and terminology used to refer to green spaces often depend on the context and specific characteristics of the area and the key issues being addressed. The terms “green space” and “open space” are often used interchangeably, both in Thailand and in international contexts, even though a space can be open but not “green” as in having plants or other vegetation [10]. The frameworks typically categorize green spaces based on size, function, and management. The World Health Organization [11] defines urban green spaces as areas within cities covered with vegetation, whether on private or public land, regardless of size and usage, including small water bodies such as ponds, lakes, or rivers. Section 2.2.1 of this paper examines in detail the different green space and public space frameworks from the context of Thai planning.

In the past decade, there has been a shift from simply measuring the availability of green spaces to a broader and more strategic approach to green infrastructure and nature-based solutions. The European Environment Agency focuses on “green infrastructure,” which examines parks and gardens, natural and semi-natural areas, green corridors, wetlands, and other green spaces [12]. This is similar to IUCN’s [13] framework of nature-based solutions, which, in the context of urban environments, focuses on green infrastructure rather than green space. Nature-based solutions frameworks emphasize multifunctionality and highlight the benefits of green elements for climate adaptation, risk reduction, and the social and physical wellbeing of residents. The distinction can be illustrated with the example of green walls, which can provide environmental benefits commonly associated with green spaces, such as improving air quality, reducing water runoff, and improving the satisfaction of residents, without being classified as a green space. Similarly, the Urban Greening Factor (UGF) used in England [14] takes a broader approach than counting only green spaces for assessing urban greening and includes green walls, planted trees, and permeable sidewalks, among other features. The Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS) proposes the Green City Conceptual Framework [15], which integrates green infrastructure and buildings as part of a bigger framework for assessing a city’s environmental performance.

These broader approaches to understanding green spaces and their multiple functions and forms in urban contexts have not been adopted in a widespread manner in Thailand. A review of Thai planning policy, described in more detail in Section 2.2.1, shows that existing policies and frameworks only focus on classifying different types of green spaces without considering that they can have multiple functionalities. Previous studies on green space in Hat Yai Municipality by Ruttirago [16,17] were based on a framework of classifying the spaces based on function. Recreational green space was found to be the smallest category of green space in Hat Yai, and only 59.50% of the population was found to have access to recreational green space within a 1 km radius. This research focuses on applying an existing centralized framework to all green spaces in Hat Yai Municipality, thereby offering both a case study of the framework’s utilization and data on green spaces.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

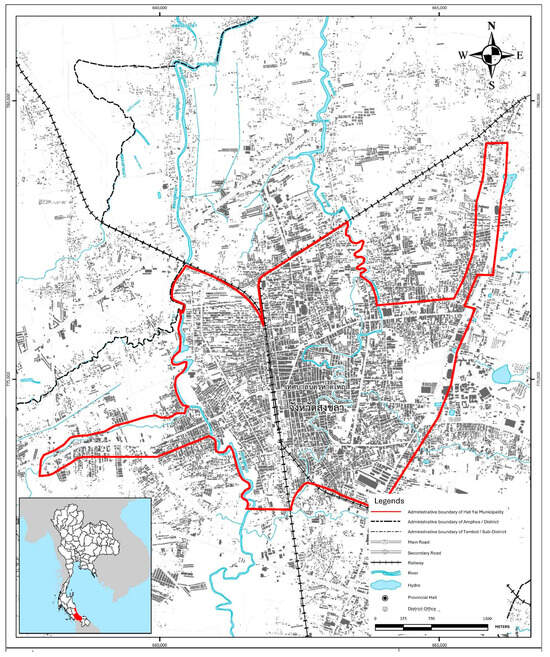

The study area of this research is the Hat Yai Municipality, which is in Songkhla province in the south of Thailand. Hat Yai is the fifth most populous city in Thailand, with a registered population of 143,733 and a geographical area of 21 square kilometers (Figure 1). Hat Yai ranks third in Thailand in terms of population density and built environment [18]. Hat Yai grew as a settlement in the 1920s following the opening of the Hat Yai Junction, which remains a significant junction that connects the train line from Bangkok to the train lines to the southern provinces. Its role as a transportation hub and proximity to Malaysia helped Hat Yai to also become a major economic center in southern Thailand, with the local economy being driven primarily by commerce and service sectors. The main trade item is rubber, for which southern Thailand is a major center of production. Today, Hat Yai has a large population of Thai–Chinese and Thai–Malay ethnic groups, which contributes to the city’s cultural and culinary diversity. The average annual income in Hat Yai is lower than that of major cities like Bangkok and Phuket, but it remains higher than most of the country.

Figure 1.

Map showing the built environment of Hat Yai Municipality, Songkhla province. Amphoe and Tambol is translated as District and Subdistrict.

Hat Yai’s growing tourism industry attracts both domestic and international tourists, the majority of whom are Malaysians who are drawn by low costs, convenient travel options, including a direct train from Kuala Lumpur, and the availability of halal food. It is estimated that Hat Yai welcomes 5000 Malaysian tourists daily on weekdays and 10,000 on weekends [19]. The city’s Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibitions (MICE) industry also attracts visitors. Hat Yai is also a regional center for education, hosting multiple notable schools as well as the oldest and largest university in the region. It is likely that urban development and population growth of Hat Yai will be further driven by two major development projects that are planned for Songkhla province, which are the creation of a 32 square kilometer industrial estate in Chana and the development of a Special Economic Zone in Songkhla province. Regarding climate risks, Hat Yai is located in a basin area and is prone to flooding because of heavy rainfall during the monsoon season. Hat Yai has experienced major flooding in 1988, 2000, and 2010. The 2000 flood caused severe economic loss and led to efforts to mitigate and prepare for flood management, for example, by improving drainage and monitoring systems [20,21]. The development and increase in green spaces in Hat Yai can enhance its attractiveness as a tourist destination and increase the city’s resilience against flood risk.

2.2. Research Methodology

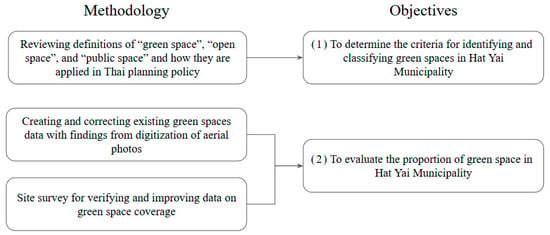

The methods used to achieve this are (1) literature review, (2) data collection and analysis, and (3) site surveys (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram summarizing the research methodology.

2.2.1. Selecting a Green Space Framework from Thailand

Currently, there is no centralized plan or nationally utilized framework for defining and categorizing green space in Thailand, and there is added complexity arising from the different terminologies used in Thai-language documents. There is no explicit definition or terminology for “green public spaces.” The meanings and definitions of similar terms used in laws or guidelines by most government agencies are more prevalent. This research therefore aims to select an existing framework from a governmental agency in Thailand and apply it to the case study to assess the framework’s usefulness for similar database creation efforts in the country. A clear framework guides data collection and analysis, providing a clear scope for stakeholder engagement and database creation, and establishes criteria for identifying green spaces. This ensures a consistent understanding of green spaces for both the digitization process and the field survey, contributing to more accurate data collection during digitization and on-site inspections.

A thorough literature review was conducted, starting with the analysis of definitions for the following keywords, which are used interchangeably in Thai: “green space,” “open space,” and “public space.” The nuance in how they are applied academically and internationally was scrutinized. Then, the review examined urban planning and policy frameworks in Thailand with the aim of selecting a framework that is the most appropriate for the assessment of green space in Hat Yai. Relevant governmental policy documents were reviewed, with a particular focus on frameworks created by centralized governmental entities in Thailand, which could allow for alignment of urban databases of different municipalities. The documents reviewed included the frameworks of the Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning (DPT) and of the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP). It was decided that the six use-based categorization framework of the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP) would be used for creating a green space database for Hat Yai. Below is a comparison of the shortlisted frameworks.

The Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning (DPT) [22] defines “open space” in urban planning guidelines as areas that bring nature into urban spaces for community health and environmental quality. These spaces, which do not generate economic revenue but provide social benefits, are especially important in large, densely populated cities. They include lawns, small parks, public parks, forests, rivers, canals, ponds, and rural fields. The key objectives for designating land use for open spaces are as follows: (1) to serve as buffers to control building constructions within designated areas, (2) to protect natural resources and biodiversity, and (3) to enhance urban aesthetics, reduce stress, and provide recreation.

The Building Control Act B.E. 2522 [23] states that “public space” refers to areas open or permitted for public access or use as passageways, with or without fees. The Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP) [24] defines “green space” as outdoor and semi-outdoor areas where the land is partially or entirely covered with vegetation on permeable soil, which may also include structures. These green spaces can be urban or rural, public or private, and accessible for public use. They comprise recreational and aesthetic green spaces; utility areas like agricultural land; and infrastructural green spaces such as buffer zones, green spaces in institutions, and natural and semi-natural habitats, including forests, wetlands, beaches, waterfronts, and green corridors along transport routes, as well as other areas like neglected or disturbed green spaces with mixed use.

The Urban Planning Act B.E. 2566 [25] presents a conceptual framework for spatial development that aligns with spatial policy design. It aims to coordinate and integrate the efforts of relevant agencies in urban development, urban planning, and spatial management. This act facilitates the integration of academic principles and cross-sectoral collaboration systematically, establishing guidelines for implementation. The Urban Planning Act B.E. 2566 provides the following definitions:

- Green Space: The Urban Planning Act defines “green space” as “areas predominantly covered with vegetation, either naturally occurring or human-made, to provide a good environment for cities or communities. Examples include forests, public parks, green belts, and tree-lined areas along rivers, roads, and railways. This does not include agricultural land.”

- Public Space: The Urban Planning Act defines “public space” as “areas open to the public for multipurpose use, facilitating social interaction, economic exchange, and cultural expression within a diverse society.”

- Open Space: The Urban Planning Act defines “open space” as “areas devoid of structures that help to reduce the density of the surrounding environment, such as communities, villages, and cities. Open spaces enhance the aesthetics of the area and contribute to public satisfaction. Additionally, open spaces have multiple benefits, including recreation, transportation, and environmental conservation.”

These definitions reflect the varied origins and practices of different government agencies in Thailand concerning green spaces, public spaces, and open spaces. The 2023 Urban Planning Act provides clear and unified definitions, making it easier to apply these definitions in development and implementation efforts across various areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of definitions from policy documents, translated from Thai by the authors.

The most descriptive frameworks were from ONEP and DPT. ONEP proposes a categorization of green spaces into six types:

- (1)

- Green space for recreation and landscape aesthetics;

- (2)

- Linear green space;

- (3)

- Functional green space;

- (4)

- Other green spaces;

- (5)

- Conservation green space;

- (6)

- Special green space.

Meanwhile, DPT classifies open space as follows:

- (1)

- Open space for recreation and environmental quality preservation;

- (2)

- Open space for preserving environmental quality along rivers and canals;

- (3)

- Open space for maintaining natural drainage patterns;

- (4)

- Retention areas for flood prevention;

- (5)

- Open space for protecting coastal and wetland environmental quality;

- (6)

- Open space for general environmental quality preservation.

A side-by-side comparison of the two frameworks is shown in Table 2. The ONEP framework covers a wider range of functions and purposes, which are more relevant for the study of green spaces in an urban setting. In contrast, the framework from the DPT is more focused on environmental quality preservation and flood prevention, which, while important, may not fully capture the broader social and aesthetic functions of urban green spaces. Therefore, the ONEP framework was utilized for the creation of the Hat Yai green space database.

Table 2.

Comparison of the classification of green space and open space by the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP) and the Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning (DPT).

A high-level workshop was conducted with stakeholders from the Hai Yai municipality and the city planning department to discuss and agree on the usage of the framework for the Hat Yai green space database. The workshop was also aimed at establishing a working definition of green space, based on findings of the literature review. The following definition was created to guide the research and future policymaking in Hat Yai: “Outdoor and semi-outdoor areas where the entire land boundary, mostly or partially, is covered with vegetation on permeable soil, which may also include structures. These green spaces within the municipality may be public or private areas accessible for public use, and they may occur naturally or be human-made to provide a good environment for the city.” This collaborative approach ensures alignment between researchers and the local government, which could facilitate the integration of green space data into a larger central government database in the future.

2.2.2. Aerial Image Analysis

The second component of the research was to identify, classify, and measure green spaces to assess the proportion of green space in Hat Yai. Multiple processes were utilized to quantify and document existing green space coverage, with the initial step being the analysis of aerial images.

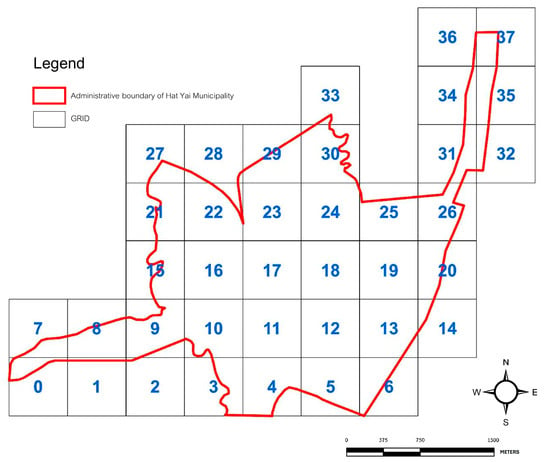

To obtain accurate green space data from aerial images, QGIS software Version 3.40.6 was used to digitize aerial images of the study area. The aerial images were provided by the Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (GISTDA). They were from 2022, which was the latest available data. The data digitization was conducted at a scale of 1:4000, the standard scale used by the Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning (DPT) for constructing Thailand’s urban physical database. This scale was selected to ensure that the research findings could be readily applied and adapted by local authorities, particularly in resource-constrained environments. A 1 × 1 km grid framework was applied to the digitized image to define the study area’s boundaries, ensuring complete coverage and dividing the study area into more manageable units for systematic data analysis and collection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Grid with the boundaries of the study area imposed for digitization.

The aerial photo interpretation was conducted grid by grid using manual visual analysis. Green space was manually identified based on key elements of spaces with vegetation according to guidelines for the visual interpretation of satellite data by the GISTDA [26]. Elements considered were color, color intensity and tone, size of green areas, and shapes. Each site location was marked and used to assess the size and coverage of green space in Hat Yai. Vegetation coverage, size, shape, and spatial distribution were also assessed. Categorization of green spaces as per the ONEP framework did not take place at this stage.

2.2.3. Site Surveys

To enhance the accuracy of data from aerial image analysis, site surveys were conducted to validate the digitized data, refine spatial classifications, and identify additional green spaces not easily detected in aerial imagery. This ground-truthing process helped correct discrepancies and enhance the reliability of the data. This research was conducted during the period when measures such as social distancing and travel restrictions were in place in Thailand due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, some in-depth interviews and meetings were conducted online via video calls instead of in person. Site surveys for this research were conducted in collaboration with local government officials and local academic institutions.

Six participants conducted this survey. On 3–6 February 2022, the researchers coordinated with Hat Yai Municipality to organize a preliminary workshop to ensure that the participants were well informed of the expected procedures and had the same level of understanding of the definition of green spaces and the classification of different types of green spaces. Participants consulted with each other to ensure alignment on how the spaces should be categorized, as the framework is not sufficiently detailed and allows for subjectivity. For example, a recreational space should have facilities such as benches or sports equipment that would allow users to spend time there. Vacant lots are those that clearly lack signs of upkeep.

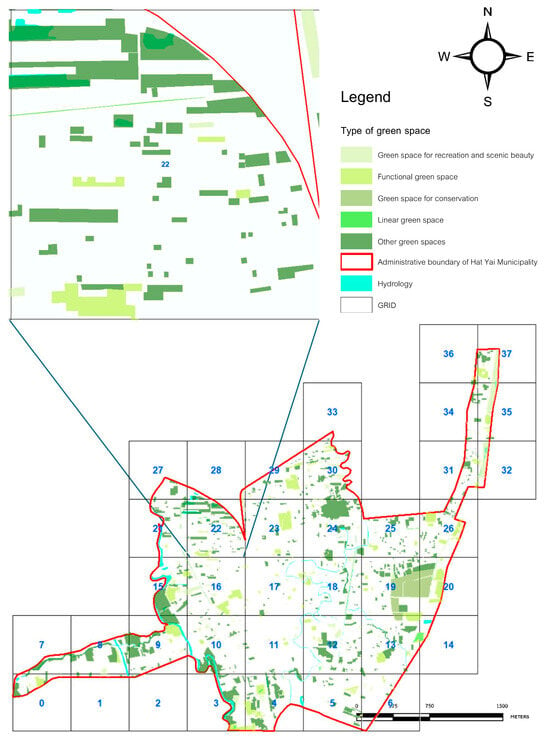

The site surveys involved checking whether there were indications that the site had changed since the aerial photographs were taken, taking supporting photographs, and assessing the conditions of the green space to confirm whether or not the site should be counted and how it should be categorized. Surveyors did not collect additional data, such as assessing the accessibility of the space. The surveys enhance the accuracy of the digitized data and ensure that the identified space conforms to the definition of “green space” of ONEP. On-site surveys were conducted over a period of three days, from morning to evening. The entire study area was divided into 37 grids, and surveyors were assigned to each grid. Vector polygons were created based on green spaces identified from aerial imagery analysis and applied to Google Maps and Google Earth (Figure 4) to help guide site surveyors. After each day’s survey, results were summarized, and data were refined. An additional day was allocated for collective data compilation and processing. The survey began with an examination of all 802 green spaces identified from aerial photographs. The survey revealed an additional 11 green spaces that were not captured in the aerial photographs, bringing the total number of green spaces in the Hat Yai Municipality to 813. The surveys helped confirm the previously identified data from the aerial image analysis, as well as provide more comprehensive documentation of green spaces in Hat Yai.

Figure 4.

Green space data in Hat Yai Municipality, with details of grid 22.

3. Results

3.1. Aerial Image Analysis Results

Manual visual analysis of 37 grids and of the digitized aerial photographs identified 802 green spaces, covering a total area of 4.13 square kilometers, which constitutes 19.64% of the study area (Figure 4). The average size of green space is 5145.07 square meters. There is some variation in the size of green spaces. For example, grid 22 has the highest count of different green spaces, but they only total 0.04 km2, while grid 19 has 50 green spaces and the largest total size of green space, comprising over 0.49 km2. This is due to the large, forested area of a rubber forest near the Prince of Songkhla University, Hat Yai Campus. Additionally, one large public park was found to be serving the urban population of Hat Yai, but it is not fully accounted for in the data because the majority of the park’s area is situated within the neighboring Kho Hong Subdistrict Municipality.

3.2. Site Survey and Data Compilation

From 3–6 February 2022, the research team conducted site surveys in the Hat Yai Municipality area to improve and verify the data gathered from aerial image analysis, providing qualitative and observational insights for comprehensiveness. The surveys were conducted grid by grid to verify and refine the shape of the compiled database and to survey the types of green spaces classified according to the framework of the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (ONEP), as described in the Literature Review section of the paper. Data from the aerial imagery analysis and the surveys were combined to create segregated data of the count, size, and type of each type of green space in each grid of the study area.

A summary of the amount and size of each type of green space identified in Hat Yai is shown in Table 3. The site surveys revealed some additional green spaces that were not captured by the aerial image analysis alone, thereby increasing the total size of green space identified in Hat Yai from 4.13 square kilometers to 4.16 square kilometers. A more detailed database showing additional data, such as the count and size of green space separated by type of green space per grid, was made available to the Hat Yai municipal government.

Table 3.

Summary of green space in Hat Yai Municipality, classified according to the ONEP framework.

4. Discussion

This research established a working definition for green space and utilized ONEP’s framework for classification. Findings show that green spaces constitute 19.81% of the total city area, equating to 4.16 square kilometers out of the total 21 square kilometers of Hat Yai Municipality. There was only a slight discrepancy between the results of data created from aerial image analysis and the site surveys, which suggests that the aerial imagery was high-quality and reliable. This data can help inform policymaking for enhancing sustainable development.

The proportion of green space measured by this study is significantly lower than both the goal and the starting point that the Hat Yai Green City Action Plan [8] used for setting the goal of increasing the proportion of green space in the city from 36% to 40%. This discrepancy suggests that the goal may have been set using outdated or inaccurate data. It is also possible that the size of green space may have decreased significantly since the plan was drafted, as Hat Yai has experienced increased urbanization in recent years. These findings suggest that it is unlikely for Hat Yai to achieve its goal of green space constituting 40% of the city by 2027. It would be beneficial for the local government to review its commitments to sustainable development and to set updated goals for increasing the proportion and quality of green space. A monitoring and evaluation system is needed to ensure that green space data is accurate and up to date in order to allow the municipality to track changes in the city’s green spaces and effectively implement development policies to achieve its green city goals. Comprehensive and interconnected data collection will facilitate appropriate green space management and better meet community needs.

This research presents an example of cooperation between researchers and local governments and universities, which could contribute to research output that can be effectively utilized for supporting policies and plans. The selection of a working definition of green spaces in Hat Yai Municipality was collaboratively established through a workshop involving key decision-makers from the municipality. This alignment facilitates easier data collection and spatial analysis at the municipal level in Hat Yai, Songkhla Province, and allows for future integration with national data and green space policies. The site surveys were conducted with the participation of urban planning students and researchers from a local university, which helps foster research skills in the domain.

4.1. Usefulness of the ONEP Framework

Using ONEP’s framework, it was found that the largest proportion of green space, at 53.33% (2.22 square kilometers), is classified as “other green spaces”, which are mostly vacant and undeveloped land. This includes land used for minor agricultural activities in a way that is locally known to be a strategy to avoid taxes, i.e., planting the minimum number of banana trees needed for the plot to be classified and taxed as agricultural land. The next largest category is “functional green space”, at 21.56% (0.90 square kilometers), which includes institutional areas such as government sites, temples, cemeteries, and green spaces around public utilities like parking areas. No “special green space” was identified.

The experience of applying the ONEP framework brings to light the possibility of a green space falling under multiple categories, as some of the categories, such as linear green space, are based on the spatial attributes of the plot, while others are based on functionality (e.g., recreational and conservation). A space could be both linear and serve recreational purposes or be multifunctional. The category of “conservation green space” is not clearly defined, but given that it does not take into consideration size and continuity, which are essential for fauna habitation, it was assumed that the focus is on conservation of green space itself and not animal habitation. Somewhat subjective decisions had to be made for the classification, which could adversely affect cross-study or pre-post comparability.

The results, with more than half of all surveyed spaces falling under one undifferentiated category of “other green space”, indicate that the ONEP framework may not be sufficiently granular and therefore provides limited analytical value. The results do not provide insight that could inform policymakers on how much of the “other green space” can be developed into high-quality green spaces that support the city’s sustainability goals and enhance urban environmental quality. This would require further analysis of the identified spaces that takes into consideration characteristics with planning implications, such as the individual plot sizes, service area, and whether the green spaces are public or privately owned. It would be helpful to be able to identify vacant plots that are big enough to serve as meaningful recreational green spaces. Tools such as Hat Yai’s Comprehensive Plan and tax policy to encourage and incentivize private sector participation in green space development.

4.2. Limitations and Further Research Directions

There were limitations to this research due to regulations related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which reduced the extent of surveys and stakeholder engagement. For more detailed insight into the green spaces in Hat Yai, future research should consider assessing the quality of green spaces and utilizing community-based participation approaches to understand how green spaces are used and what the residents’ needs are. A comparative study with other similarly sized Thai cities could help contribute to the formulation of a more sophisticated framework that can be adopted by government agencies. To focus more on climate change adaptation and flood resilience, it would be beneficial for the Hat Yai Municipality to map, quantify, and develop the ecosystem services provided by the green spaces.

5. Conclusions

The research found that green spaces constitute 19.81% of Hat Yai Municipality, which strongly suggests that the municipality should revise the goals set out in its green spaces plan. The identified green spaces are categorized according to the framework of ONEP, which was found to be the most appropriate framework from a Thai national agency. However, the application of this framework reveals that, while the ONEP framework provides guidance that is useful for creating a basic green space database for establishing a baseline assessment, its applicability is limited for developing a green space database that supports strategic policymaking and high-quality environmental management because the proposed classification system is too broad and does not take into account factors that guide development policy, such as plot size, ownership, quality, and service area. For sustainable urban development policymaking, it would be useful for Thai authorities to consider adopting a framework for green infrastructure management, which is more insightful in ensuring that the existing green spaces and features are providing the desired environmental and social benefits, such as climate change adaptation and recreational values. This is a “next step” from the current approach of ONEP’s framework, which considers green spaces as discrete entities rather than infrastructure with specific purposes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M.; Investigation, P.M.; Writing—original draft, P.M.; Writing—review and editing, W.M.; Supervision, W.M.; Project administration, W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received seed grant from EPIC-N.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by Thammasat University Research Unit in Urban Futures and Policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elmqvist, T.; Setälä, H.; Handel, S.N.; van Der Ploeg, S.; Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.N.; de Groot, R. Benefits of restoring ecosystem services in urban areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. The Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017–2021); Office of the Prime Minister: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Progress Report on Thailand’s Sustainable Development Goals 2016–2020. Available online: https://e-library.moc.go.th/book-detail/20764 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Hat Yai Municipality. Green City Action Plan 2017–2027. Available online: https://www.hatyaicity.go.th/files/com_networknews/2017-08_329665d5b2cf7f1.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Choosuk, A.; Thitinanthakorn, M.; Rattanaphithakchon, M. Urbanization Process of Hat Yai City. Available online: https://www.tei.or.th/thaicityclimate/public/work-17.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Swanwick, C.; Dunnett, N.; Woolley, H. Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview. Built Environ. 2023, 29, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces: A Brief for Action; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Green Infrastructure and Territorial Cohesion: The Concept of Green Infrastructure and Its Integration into Policies; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/green-infrastructure-and-territorial-cohesion (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. (Eds.) Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; 97p. [Google Scholar]

- Natural England. Urban Greening Factor for England User Guide; Natural England: Bridgwater, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brilhante, O.; Klaas, J. Green City Concept and a Method to Measure Green City Performance over Time Applied to Fifty Cities Globally: Influence of GDP, Population Size and Energy Efficiency. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttirago, P. Quality Assessment and Management Guidelines for Recreational Green Areas in Hat Yai Municipality and Kho Hong Town Municipality, Hat Yai District, Songkhla Province. Doctoral Dissertation, Prince of Songkhla University, Songkhla, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ruttirago, P. Accessibility of recreational green spaces in Hat Yai Municipality, Songkhla. SDU Res. J. (Sci. Technol.) 2013, 6, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, H. Budget-Conscious Malaysians Flock to Hat Yai for Holiday as Prices Rise at Home. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/budget-conscious-malaysians-holiday-in-hat-yai-with-train-service-from-kl-proving-a-hit (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Supharatid, S. The Hat Yai 2000 flood: The worst flood in Thai history. Hydrol. Process. 2006, 20, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Provincial Administration. Available online: https://stat.bora.dopa.go.th (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Middleton, C.; Pratomlek, O. Flooding disaster, people’s displacement, and state response: A case study of Hat Yai municipality. In Climate Change, Disasters, and Internal Displacement in Asia and the Pacific, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning. Urban Planning Standards and Criteria 2006. Available online: https://www.dpt.go.th/th/dpt-standard/download?did=3814&filename=std_plan2549.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning. Building Control Act B.E. 2522 (1979); Government of Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning. Green Space Development Manual; Chiang Mai University: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning. Urban Planning Act B.E. 2566 (2023); Government of Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- GISTDA. Visual Interpretation of Satellite Data. Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (Public Organization). Available online: https://www.gistda.or.th/news_view.php?n_id=2400&lang=TH (accessed on 7 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).