Assessing Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change in High-Altitude Himalayan Regions: A Composite Index Approach in Lahaul and Spiti, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background of Agricultural Vulnerability Index

2. Materials and Methods

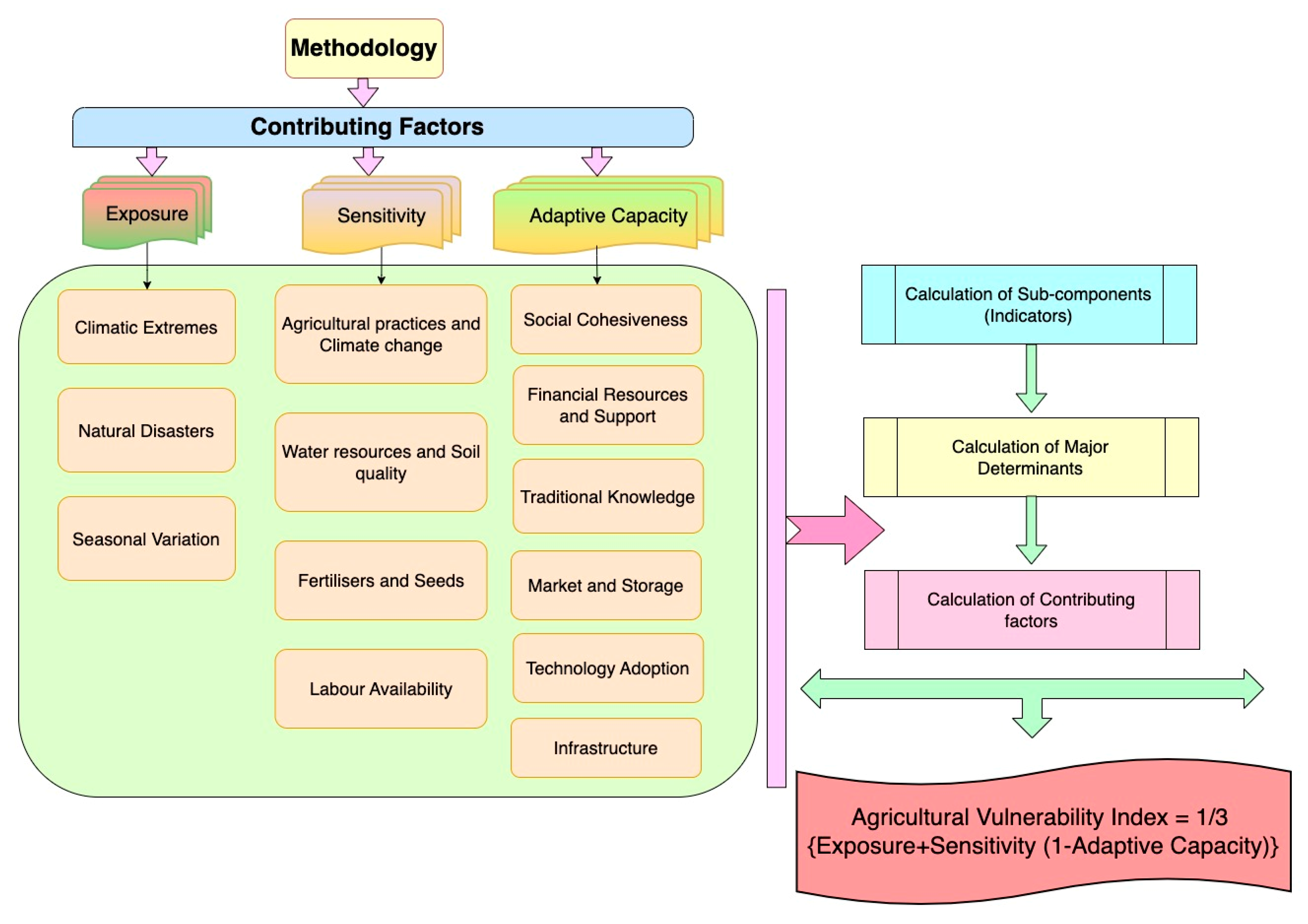

2.1. Agricultural Vulnerability Indicators

2.1.1. Exposure

2.1.2. Sensitivity

| Contributing Factors of AVI | Major Determinants | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Climatic extremes | Mean Standard deviation of average annual rainfall (1951–2023); Mean Standard deviation of average annual mean temperature (1951–2023); Mean Standard deviation of average annual Snowfall (1951–2023); Mean Standard deviation of average annual Humidity (1981–2023) [38] |

| Natural Disasters | Receive warnings about floods/landslides/avalanches/frost/cloudbursts/earthquakes, Increase in Floods, Droughts during the agricultural season, Increase in Landslides, and Frost during the agricultural season. | |

| Seasonal Variation | Noticed changes in Agricultural Season, the Earlier onset of the season, Prolonged duration of the season | |

| Sensitivity | Agricultural Practices and Climate Changes | Climate Change affected farmers’ agricultural practices in the past 30 years; Shift in planting/harvesting time; Changes in Crop varieties; Per cent Irrigated Land; Temperature affected Crop yields; Per cent un-irrigated Land; Crop diversity index. |

| Water resource and Soil quality | Climate Change affected the water availability resources for irrigation, increased the need for water for irrigation, increased soil erosion, and caused loss of soil fertility. | |

| Fertilisers and Seeds | Uses of NPK fertilisers; Uses of organic fertilisers/manures; Times of fertilisers per crop per season; Increasing severity of pest and disease outbreak; Save Seeds/crops; Uses of hybrid/GM seeds; Practice Crop rotation | |

| Labour Availability | Demand for Labour; Hire labourers for farming activities; Availability of labour during peak season | |

| Adaptive Capacity | Social-cohesiveness | Female farmers; Participation in Community Activities; Perception of trust within communities; Marginal farmers; Average no. of Migrants |

| Financial Resources and Support | Support received from the community during a crisis; Support from Govt./NGOs; Training Programmes/Weather forecasts; Banking assistance in crop failure; Crop Insurance | |

| Traditional Knowledge | Uses of traditional seeds; Uses of traditional methods of farming/storage | |

| Market and Storage | Condition of Road Network; Accessibility to the local market; Distance to nearest market/mandis; Accessibility To storage facility | |

| Technology Adoption | Adopted new initiatives for farming, such as piped irrigation, precision farming tools, and weather forecasting apps; income increases through the adoption of farming technology. | |

| Infrastructure | Polyhouse farming; Sprinkler irrigation; Mechanised equipment |

2.1.3. Adaptive Capacity

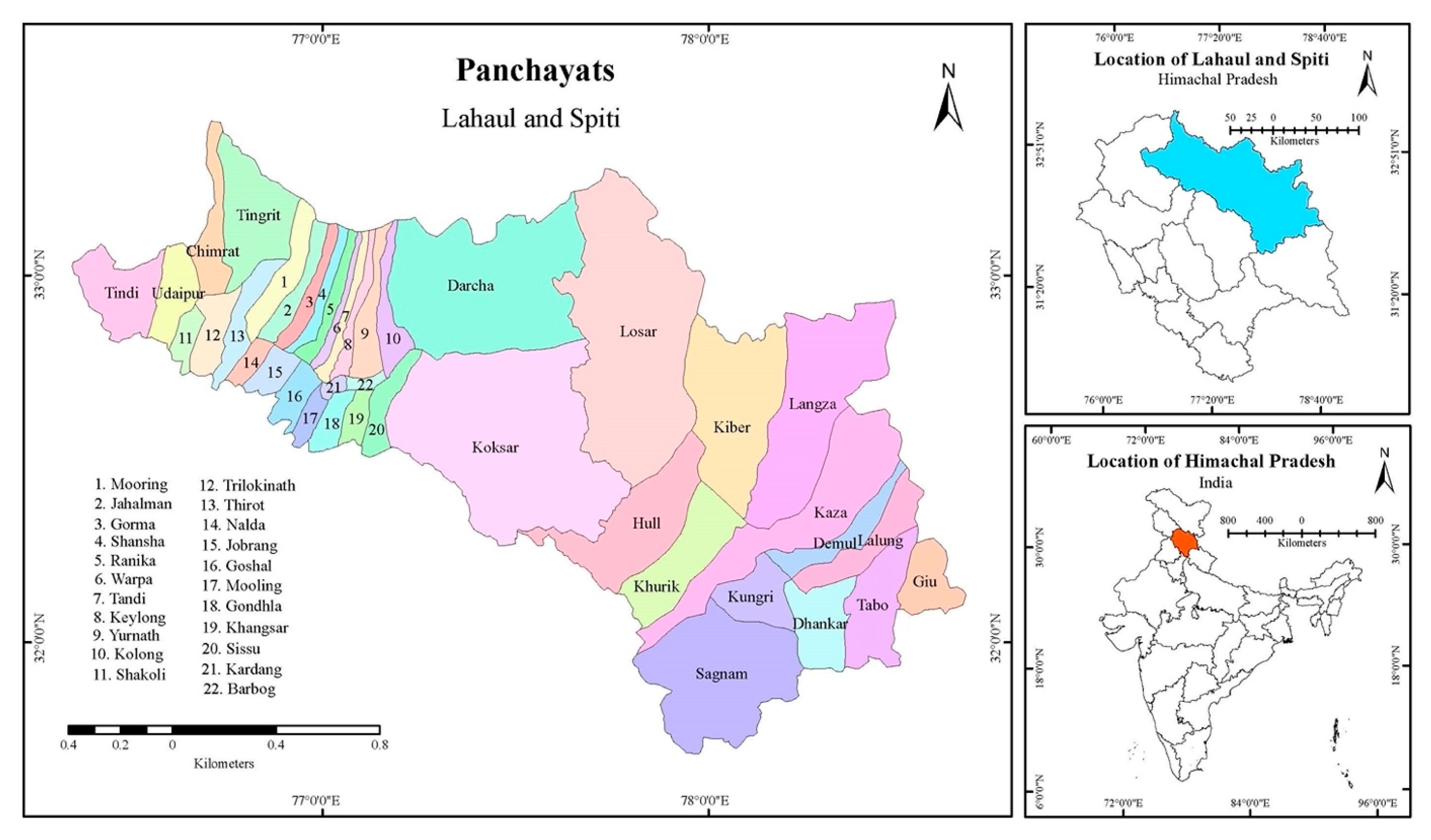

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Methodology

Indicator Redundancy and Multicollinearity Check

3. Results

3.1. Various Indicators of Exposure, Sensitivity and Adaptive Capacity

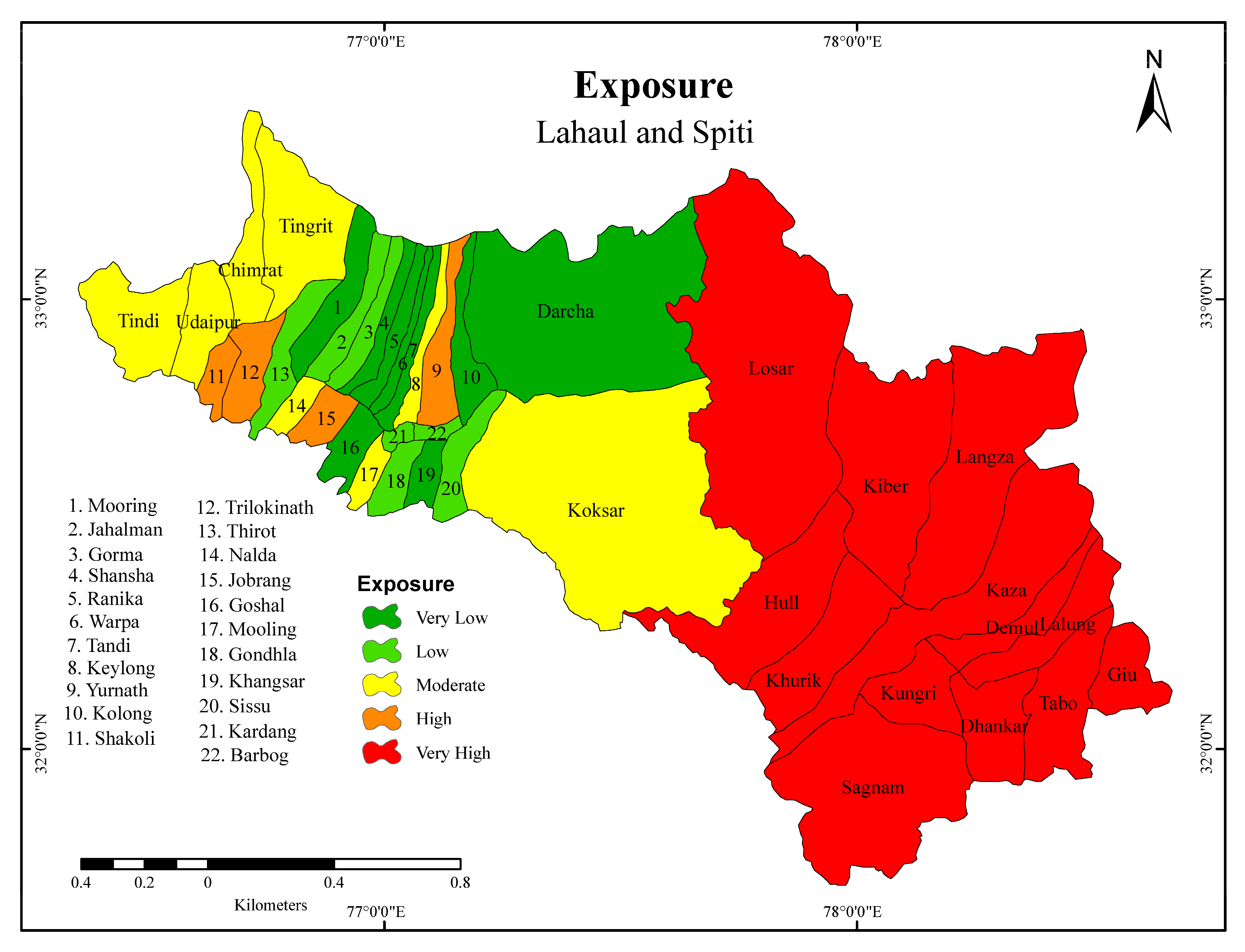

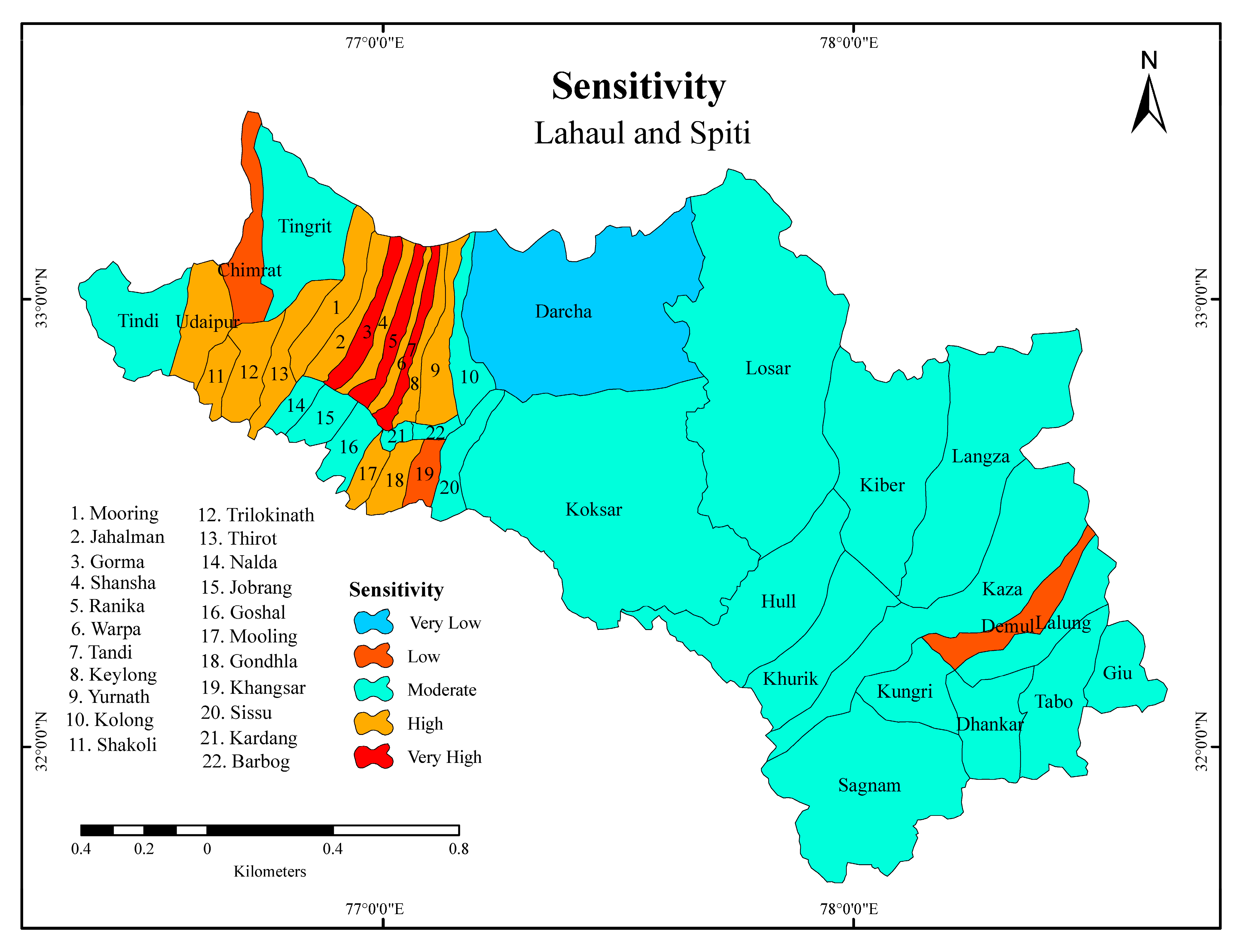

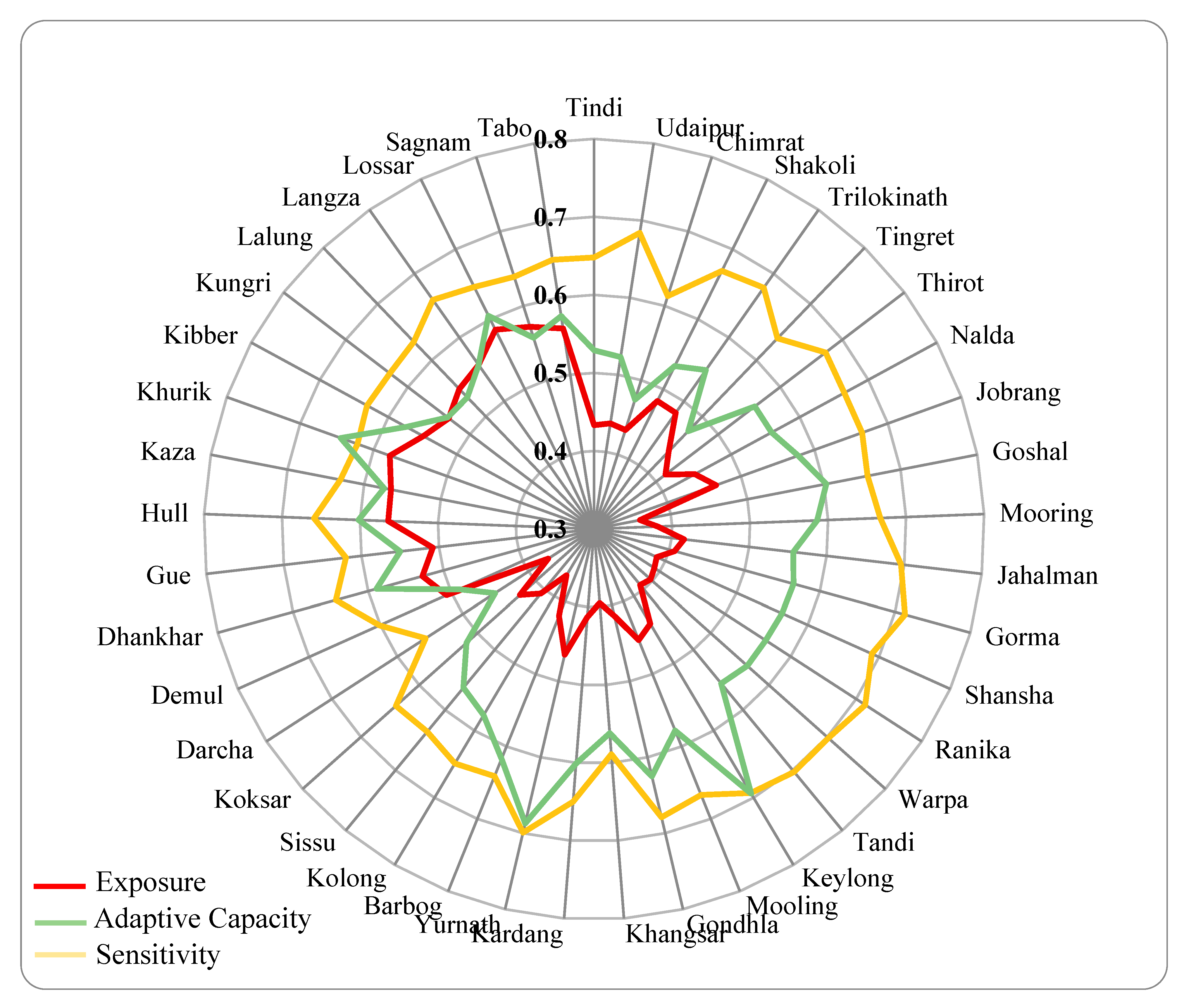

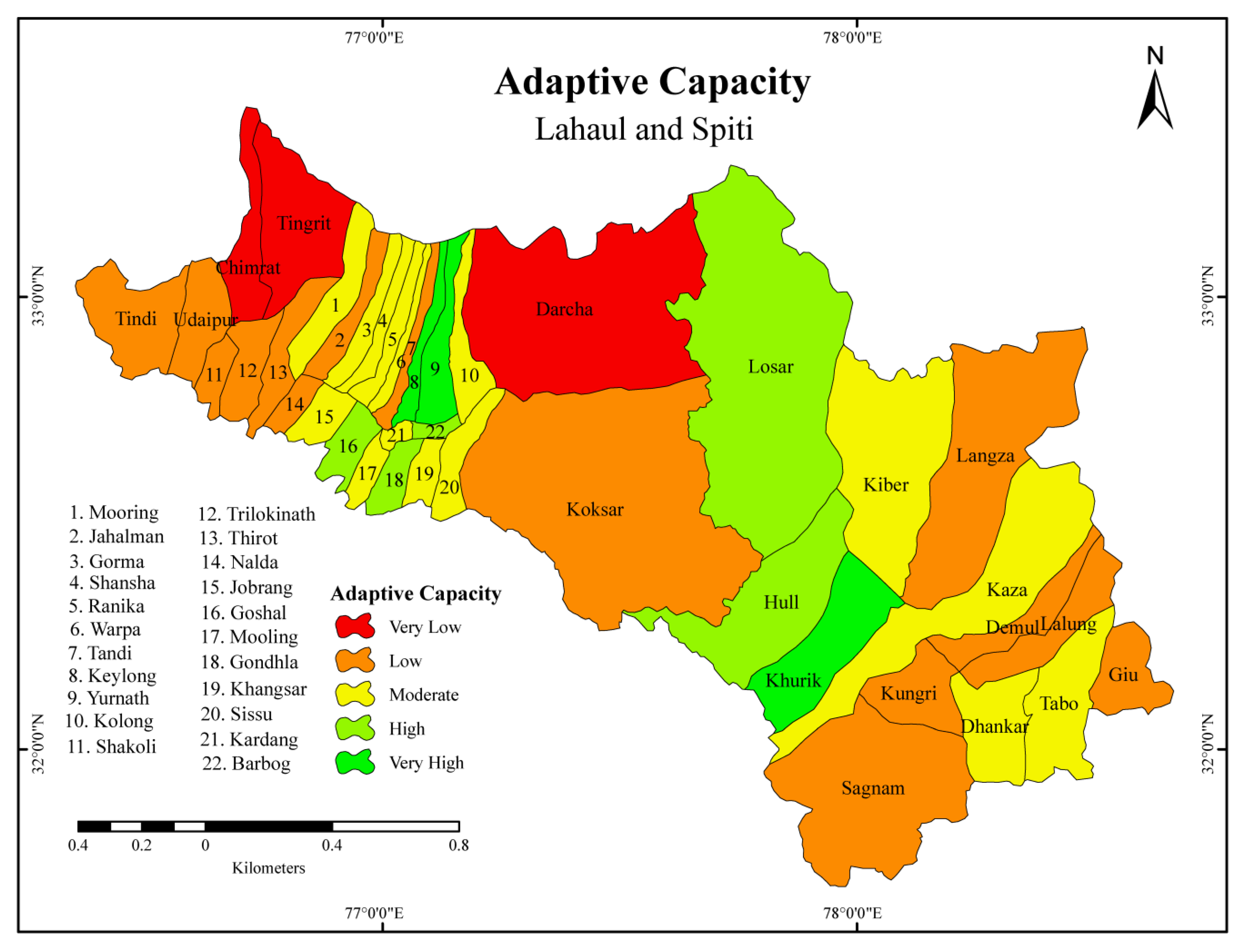

3.2. Constituent Factors of Agricultural Vulnerability Index: Exposure, Sensitivity and Adaptive Capacity

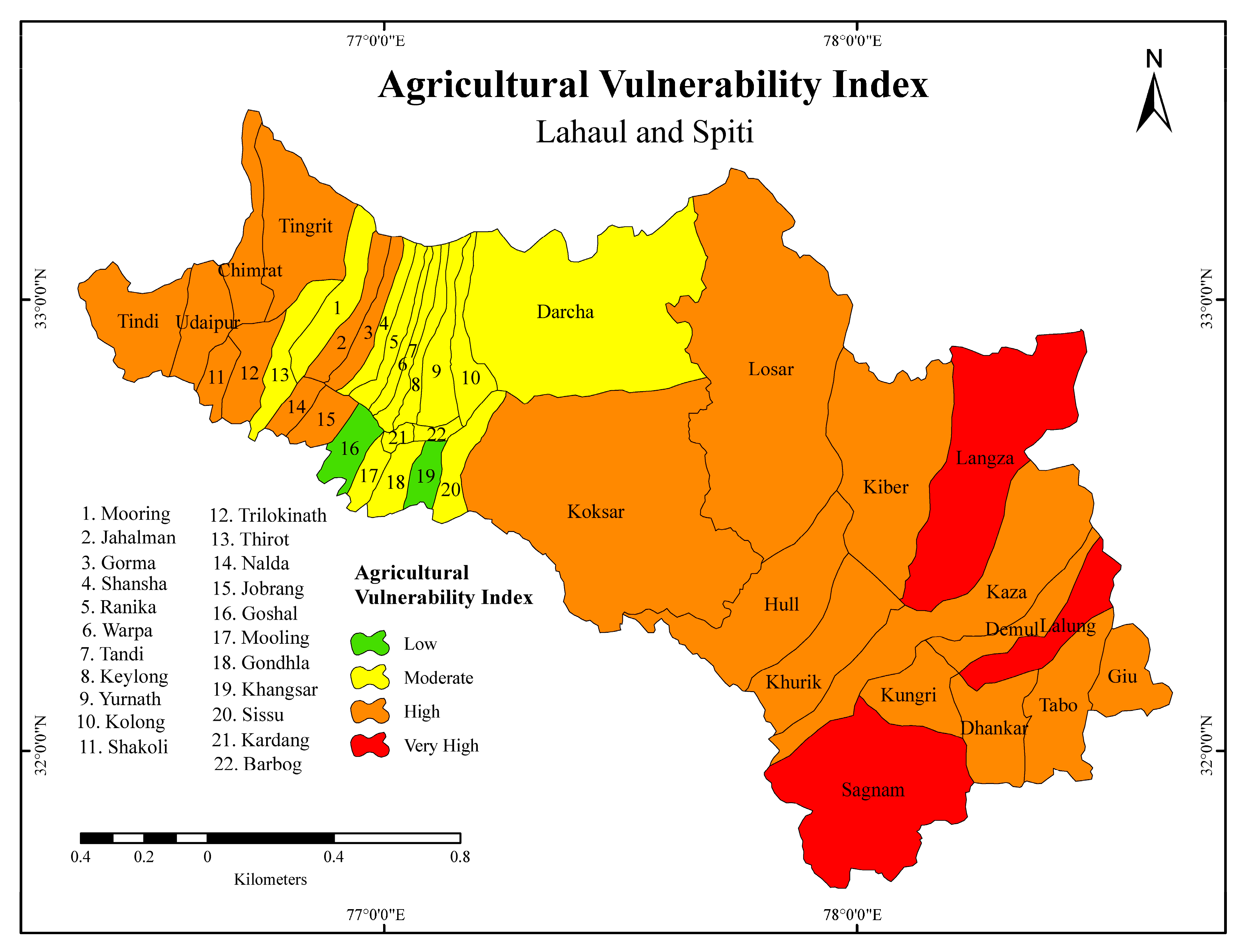

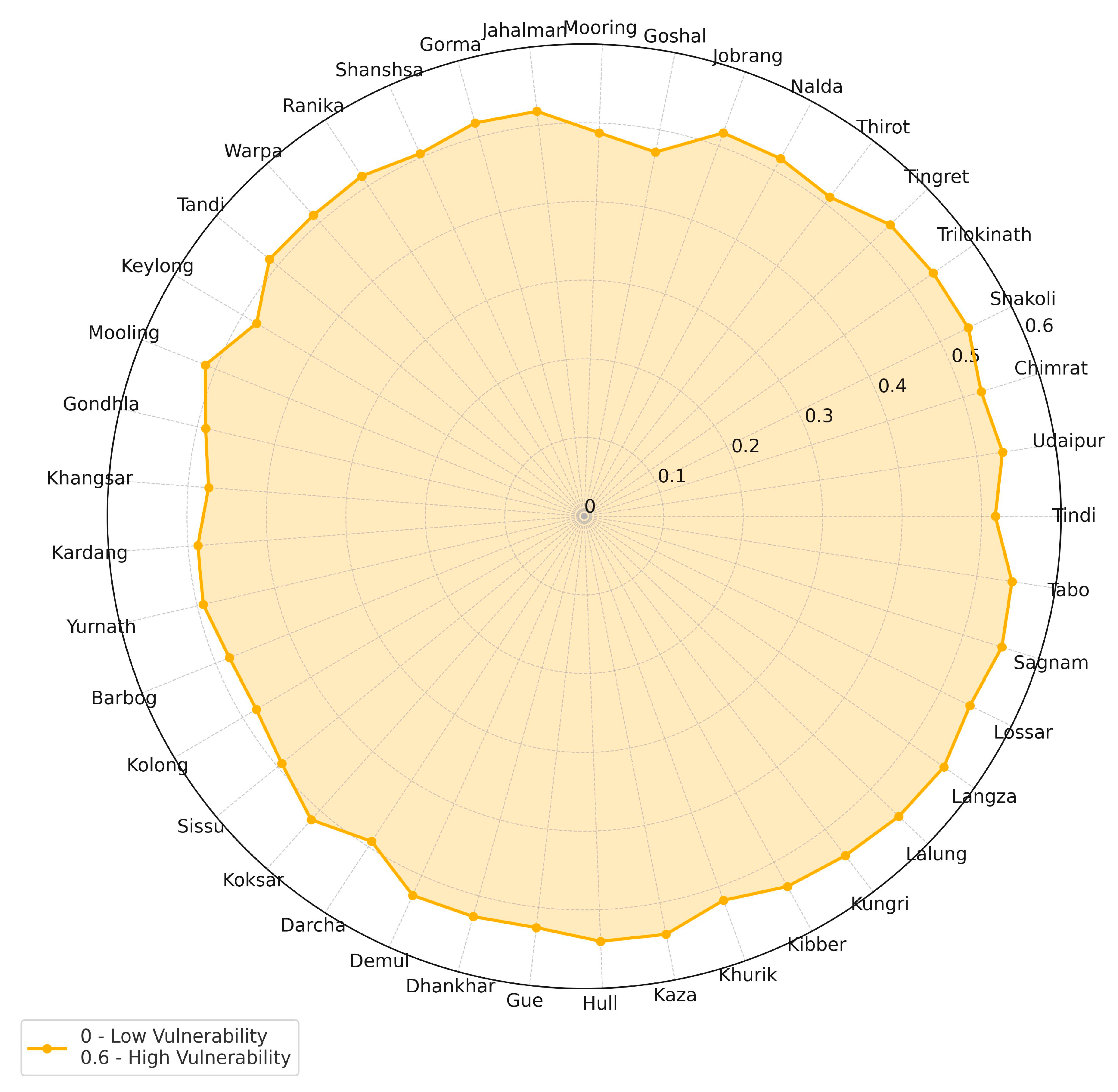

3.3. Agricultural Vulnerability Index

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy and Recommendations

4.1.1. Development of Climate-Resilient Infrastructure

4.1.2. Encourage Diversification and Climate-Smart Agriculture

4.1.3. Expand Financial and Institutional Support

4.1.4. Formalizing Local Knowledge in Adaptation Planning

4.1.5. Implement Early Warning and Extension Service Facilities

4.2. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVI | Agricultural Vulnerability Index |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| NMSA | National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture |

| DRR | Disaster Risk Reduction |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| HDI | Human Development Index |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability—Summaries, FAQs and Cross-Chapter Boxes; Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Parker, L.; Bourgoin, C.; Martinez-Valle, A.; Läderach, P. Vulnerability of the Agricultural Sector to Climate Change: Development of a Pan-Tropical Climate Risk Vulnerability Assessment. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Xu, Y.; Liu, K.; Pan, J.; Gou, S. Research Progress in Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2011, 2, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanir, T.; Yildirim, E.; Ferreira, C.M.; Demir, I. Social Vulnerability and Climate Risk Assessment for Agricultural Communities in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiréhn, L.; Danielsson, Å.; Neset, T.S. Assessment of composite index methods for agricultural vulnerability to climate change. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 156, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar4_wg2_full_report.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Neset, T.S.; Wiréhn, L.; Opach, T.; Glaas, E. Evaluation of Indicators for Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change: The Case of Swedish Agriculture. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 105, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.; Moharaj, P. Assessing Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change through Dynamic Indexing Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 55000–55021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniyal, J.C.; Vishvakarma, S.C.R.; Singh, G.S. Changing Crop Biodiversity and Resource Use Efficiency of Traditional Versus Introduced Crops in the Cold Desert of the Northwestern Indian Himalaya: A Case of the Lahaul Valley. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 1271–1304. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:BIOC.0000019404.48445.27 (accessed on 23 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, B.B.; Sirohi, S. Understanding the Vulnerability of Agricultural Production Systems to Climatic Stressors in North India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 5671–5689. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Singh, S.K.; Kanga, S.; Meraj, G.; Mushtaq, F.; Đurin, B.; Pham, Q.B.; Hunt, J. Assessing Future Agricultural Vulnerability in Kashmir Valley: Mid- and Late-Century Projections Using SSP Scenarios. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, P.; Singh, A.; Ashwani; Kumar, M. Socio-Economic Livelihood Vulnerability to Mountain Hazards: A Case of Uttarakhand Himalaya, India. In Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Systems for Policy Decision Support; Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences; Singh, R.B., Kumar, M., Tripathi, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omerkhil, N.; Chand, T.; Valente, D.; Alatalo, J.M.; Pandey, R. Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Strategies for Smallholder Farmers in Yangi Qala District, Takhar, Afghanistan. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC). State Action Plan on Climate Change: Himachal Pradesh; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD). Climate and Environmental Change Impacts the Hindu Kush Himalaya: Concerns and Policy Responses; ICIMOD Reports: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.J.L.B.; Da Silva, F.R.; De Souza Lessa, B.; Câmara, S.F.; De Sousa-Filho, J.M. Marine Pollution and Socioeconomic Vulnerability in Brazilian Coastal Cities. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, D.T.; Huong, L.V.; Tuan, P.A.; Nhung, N.T.H.; Huong, T.T.Q.; Man, B.T.H. An Assessment of Agricultural Vulnerability in Global Climate Change: A Case Study in Ha Tinh Province, Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkel, J. Indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity: Towards a clarification of the science–policy interface. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ashwani; Mishra, S.; Thakur, S.; Kumar, D.; Raman, V.A.V. Vulnerability of tribal communities to climate variability in Lahaul and Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, India. J. Geogr. 2023, 47, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Climate Change and Agriculture: Impacts, Adaptation, and Mitigation Strategies; FAO Publications: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, T.P.; Adam, J.C.; Lettenmaier, D.P. The Effects of Climate Change on Water Resources. Nature 2005, 438, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbetibouo, G.A.; Ringler, C.; Hassan, R. Vulnerability of the South African Farming Sector to Climate Change and Variability: An Indicator Approach. Nat. Resour. Forum 2010, 34, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Leichenko, R.; Kelkar, U.; Venema, H.; Aandahl, G.; Tompkins, H.; West, J. Mapping Vulnerability to Multiple Stressors: Climate Change and Globalisation in India. Glob. Environ. Change 2004, 14, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindranath, N.H.; Rao, S.; Sharma, N.; Nair, M.; Gopalakrishnan, R.; Rao, A.S.; Malaviya, S.; Tiwari, R.; Sagadevan, A.; Munsi, M.; et al. Climate Change Vulnerability Profiles for North East India. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Kelly, P.M. Developing Credible Vulnerability Indicators for Climate Adaptation Policies. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 12, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Barron, J.; Fox, P. Water productivity in rain-fed agriculture: Challenges and opportunities for smallholder farmers in drought-prone tropical agroecosystems. Limits Oppor. Improv. 2003, 85, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.P.; Rockström, J.; Oweis, T. Rainfed Agriculture: Unlocking the Potential; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/w5183e/w5183e08.htm (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Abrol, Y.P.; Ingram, K.T. Effects of Higher Day and Night Temperatures on Growth and Yields of Some Crop Plants. In Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L.; Belay, S.; Kalangu, J.; Menas, W.; Munishi, P.; Musiyiwa, K. Climate Change Adaptation in Africa; Climate Change Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, U.; Narayanan, K. Vulnerability and Climate Change: An Analysis of the Eastern Coastal Districts of India; MPRA Paper No. 22062; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Swami, D.; Parthasarathy, D. A Multidimensional Perspective to Farmers’ Decision Making Determines the Adaptation of the Farming Community. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Mujumdar, P.P. Climate Change Impact Assessment: Uncertainty Modeling with Imprecise Probability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D14113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Hu, G.; Qian, G.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, W.; Lyu, P. High-Altitude Aeolian Research on the Tibetan Plateau. Rev. Geophys. 2017, 55, 864–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The Impa ct of Climate Change on Agricultural Insect Pests. Insects 2021, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Magar, N.T.; Thapa, B.J.; Shahi, P.; Sharma, T.P.P. Measuring Climate Vulnerability of Tourism-Dependent Livelihoods: The Case of Langtang National Park. J. Tour. Himal. Adv. 2024, 6, 16–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Building Resilience: Adaptive Capacity Strategies for Climate-Vulnerable Regions; UNDP Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Ashwani. Assessment of Livelihood Vulnerability and Climate Change Perception in Lahaul and Spiti District, Himachal Pradesh, India. In Livelihoods and Well-Being in the Era of Climate Change; Banu, N., Fazal, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate of Extension Education; CSK Himachal Pradesh Krishi Vishavavidyalaya. Annual Progress Report 2020–21: Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Lahaul & Spiti-1 at Kukumseri–175142 (H.P.); CSK Himachal Pradesh Krishi Vishavavidyalaya: Palampur, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, D.S.; Sridhar, L.; Rajeevan, M.; Sreejith, O.P.; Satbhai, N.S.; Mukhopadhyay, B. Development of a New High Spatial Resolution (0.25° × 0.25°) Long Period (1901–2010) Daily Gridded Rainfall Data Set over India and Its Comparison with Existing Data Sets over the Region. Mausam 2014, 65, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G. ERA5-Land: A State-of-the-Art Global Reanalysis Dataset for Land Applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, H.K.; Karunanayake, C.; Gunathilake, M.B.; Rathnayake, U. Integrating Indicators in Agricultural Vulnerability Assessment to Climate Change. Agric. Res. 2024, 13, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayadas, A.; Ambujam, N.K.A. Quantitative Assessment of Vulnerability of Farming Communities to Extreme Precipitation Events in Lower Vellar River Sub-Basin, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 13541–13563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, S.; Rad, G.P.; Sedighi, H.; Azadi, H. Vulnerability of Wheat Farmers: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sarda, R.; Yadav, A.; Ashwani; Gonencgil, B.; Rai, A. Farmer’s Perception of Climate Change and Factors Determining the Adaptation Strategies to Ensure Sustainable Agriculture in the Cold Desert Region of Himachal Himalayas, India. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoudi, H.; Locatelli, B.; Vaast, C.; Asher, K.; Brockhaus, M.; Sijapati Basnett, B. Beyond dichotomies: Gender and intersecting inequalities in climate change studies. Ambio 2016, 45, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geza, W.; Ngidi, M.; Ojo, T.; Adetoro, A.A.; Slotow, R.; Mabhaudhi, T. Youth Participation in Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, G.; Sharma, B. The nexus approach to water–energy–food security: An option for adaptation to climate change. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Climate-Smart Agriculture Sourcebook: Summary; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Autio, A.; Johansson, T.; Motaroki, L.; Minoia, P.; Pellikka, P. Constraints for adopting climate-smart agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Southeast Kenya. Agric. Syst. 2021, 194, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliacci, F.; Defrancesco, E.; Mozzato, D.; Bortolini, L.; Pezzuolo, A.; Pirotti, F.; Pisani, E.; Gatto, P. Drivers of farmers’ adoption and continuation of climate-smart agricultural practices. A study from northeastern Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakweya, R.B. Challenges and prospects of adopting climate-smart agricultural practices and technologies: Implications for food security. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.No. | Panchayats | No. of Households | S.No. | Panchayats | No. of Households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tindi | 5 | 22 | Kardang | 6 |

| 2 | Udaipur | 10 | 23 | Yurnath | 10 |

| 3 | Chimrat | 5 | 24 | Barbog | 7 |

| 4 | Shakoli | 7 | 25 | Kolong | 10 |

| 5 | Trilokinath | 8 | 26 | Sissu | 10 |

| 6 | Tingret | 5 | 27 | Koksar | 6 |

| 7 | Thirot | 7 | 28 | Darcha | 10 |

| 8 | Nalda | 5 | 29 | Demul | 5 |

| 9 | Jobrang | 6 | 30 | Dhankhar | 6 |

| 10 | Goshal | 7 | 31 | Gue | 5 |

| 11 | Mooring | 7 | 32 | Hull | 6 |

| 12 | Jahalman | 9 | 33 | Kaza | 7 |

| 13 | Gorma | 6 | 34 | Khurik | 9 |

| 14 | Shanshsa | 8 | 35 | Kibber | 7 |

| 15 | Ranika | 6 | 36 | Kungri | 6 |

| 16 | Warpa | 7 | 37 | Lalung | 7 |

| 17 | Tandi | 7 | 38 | Langza | 5 |

| 18 | Keylong | 10 | 39 | Lossar | 10 |

| 19 | Mooling | 5 | 40 | Sagnam | 5 |

| 20 | Gondhla | 6 | 41 | Tabo | 10 |

| 21 | Khangsar | 8 | |||

| Panchayats | Exposure | Sensitivity | Adaptive Capacity | AVI | Major Affected SDGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tindi | 0.433 | 0.648 | 0.529 | 0.517 | SDG 13 |

| Udaipur | 0.437 | 0.684 | 0.523 | 0.533 | SDG 13 |

| Chimrat | 0.433 | 0.613 | 0.474 | 0.524 | SDG 6 and 13 |

| Shakoli | 0.483 | 0.669 | 0.533 | 0.539 | SDG 13 |

| Trilokinath | 0.482 | 0.678 | 0.549 | 0.537 | SDG 13 |

| Tingret | 0.438 | 0.639 | 0.474 | 0.534 | SDG 6 and 13 |

| Thirot | 0.415 | 0.673 | 0.559 | 0.510 | SDG 13 |

| Nalda | 0.447 | 0.665 | 0.559 | 0.517 | SDG 13 |

| Jobrang | 0.466 | 0.665 | 0.578 | 0.518 | SDG 13 |

| Goshal | 0.360 | 0.657 | 0.603 | 0.471 | SDG 13 |

| Mooring | 0.382 | 0.667 | 0.586 | 0.488 | SDG 13 |

| Jahalman | 0.416 | 0.696 | 0.557 | 0.518 | SDG 13 |

| Gorma | 0.407 | 0.713 | 0.565 | 0.518 | SDG 13 |

| Shansha | 0.388 | 0.690 | 0.564 | 0.505 | SDG 13 |

| Ranika | 0.392 | 0.714 | 0.562 | 0.515 | SDG 13 |

| Warpa | 0.397 | 0.702 | 0.563 | 0.512 | SDG 13 |

| Tandi | 0.393 | 0.703 | 0.556 | 0.513 | SDG 13 |

| Keylong | 0.441 | 0.693 | 0.694 | 0.480 | SDG 13 |

| Mooling | 0.453 | 0.667 | 0.578 | 0.514 | SDG 13 |

| Gondhla | 0.414 | 0.679 | 0.625 | 0.489 | SDG 13 |

| Khangsar | 0.395 | 0.589 | 0.562 | 0.474 | SDG 13 |

| Kardang | 0.413 | 0.650 | 0.601 | 0.488 | SDG 13 |

| Yurnath | 0.465 | 0.699 | 0.687 | 0.492 | SDG 13 |

| Barbog | 0.420 | 0.641 | 0.617 | 0.481 | SDG 13 |

| Kolong | 0.369 | 0.649 | 0.577 | 0.480 | SDG 13 |

| Sissu | 0.407 | 0.636 | 0.563 | 0.493 | SDG 13 |

| Koksar | 0.427 | 0.640 | 0.519 | 0.516 | SDG 13 |

| Darcha | 0.370 | 0.557 | 0.451 | 0.492 | SDG 6 and 13 |

| Demul | 0.507 | 0.601 | 0.489 | 0.540 | SDG 2, 6 and 13 |

| Dhankhar | 0.528 | 0.643 | 0.589 | 0.527 | SDG 2, 6 and 13 |

| Gue | 0.508 | 0.620 | 0.550 | 0.526 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Hull | 0.564 | 0.659 | 0.602 | 0.540 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Kaza | 0.565 | 0.631 | 0.574 | 0.541 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Khurik | 0.578 | 0.622 | 0.645 | 0.518 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Kibber | 0.549 | 0.631 | 0.574 | 0.535 | SDG 2, 6 and 13 |

| Kungri | 0.534 | 0.629 | 0.536 | 0.542 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Lalung | 0.549 | 0.633 | 0.534 | 0.550 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Langza | 0.557 | 0.659 | 0.557 | 0.553 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Lossar | 0.585 | 0.646 | 0.605 | 0.542 | SDG 6, 13 |

| Sagnam | 0.572 | 0.639 | 0.557 | 0.551 | SDG 2, 6 and 13 |

| Tabo | 0.560 | 0.649 | 0.576 | 0.545 | SDG 6, 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ashwani; Kumar, P.; Janmaijaya, M.; Gönençgil, B.; Li, Z. Assessing Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change in High-Altitude Himalayan Regions: A Composite Index Approach in Lahaul and Spiti, India. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310682

Ashwani, Kumar P, Janmaijaya M, Gönençgil B, Li Z. Assessing Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change in High-Altitude Himalayan Regions: A Composite Index Approach in Lahaul and Spiti, India. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310682

Chicago/Turabian StyleAshwani, Pankaj Kumar, Mansi Janmaijaya, Barbaros Gönençgil, and Zhihui Li. 2025. "Assessing Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change in High-Altitude Himalayan Regions: A Composite Index Approach in Lahaul and Spiti, India" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310682

APA StyleAshwani, Kumar, P., Janmaijaya, M., Gönençgil, B., & Li, Z. (2025). Assessing Agricultural Vulnerability to Climate Change in High-Altitude Himalayan Regions: A Composite Index Approach in Lahaul and Spiti, India. Sustainability, 17(23), 10682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310682