Natural Clay in Geopolymer Concrete: A Sustainable Alternative Pozzolanic Material for Future Green Construction—A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Potential Challenges in Utilising Clay as an SCM

2. Clays and Their Chemical Compositions

2.1. Kaolinite Clay

2.2. Illite Clay

2.3. Bentonite/Montmorillonite (MMT) Clay

2.4. Halloysite Clay

2.5. Palygorskite Clay

2.6. Sepiolite Clay

3. Clay Activation/Treatment Methods

3.1. Thermal Activation

| Type of Clay | Optimal Temperature (°C) | Duration of Calcination (Hours)/Rate of Heat Increment | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolinite | 650–850 | 3 | Kaolin with low alunite content was optimal at 650 °C, whereas kaolin with high alunite content required 850 °C. | [154] |

| 700–800 | 1 (2 °C/min) | Due to its high pozzolanic index, kaolin was transformed into metakaolin. | [133] | |

| 750 | 1 | Kaolin clay heated to this temperature and for this duration showed the highest strength when replaced with 10% cement. | [117] | |

| 750 | 3 | Metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete exhibits superior mechanical performance when heated to this specified temperature for the specified duration. | [118] | |

| 750 | 10 (2 °C/min) | Raw kaolin was heated to the specified temperature for the specified duration, converting it into a highly pozzolanic material. This pozzolanic clay was replaced with fly ash to make geopolymer composites. | [155] | |

| 700 | 10 (5 °C/min) | Above 700 °C, calcined kaolin began to lose its pozzolanic reactivity in geopolymer cement. | [134] | |

| 700 | 3 (10 °C/min) | To make geopolymer concrete, a variety of calcium-rich additives, including calcium carbide residue, lime, and OPC, were partially replaced with calcined kaolin. | [135] | |

| 600 | 1 | Kaolin clay heated to this temperature and for this duration showed mechanical performance when cured at 60 °C for 24 h. | [156] | |

| 750 | 1 | Kaolin heated at this temperature exhibited optimal pozzolanic activity when partially replaced with OPC. When heated at 850 °C, it displayed reduced pozzolanic activity due to recrystallisation. | [157] | |

| 650 | 1 (25 °C/min) | At this temperature, kaolin exhibited the highest dehydroxylation rate (>85%). | [158] | |

| 900 | 6 | At this temperature, kaolin exhibited the highest reactivity, and above it, reactivity sharply declined. | [136] | |

| Illite | 950 | 1 | Illite calcined at this temperature became a highly reactive geopolymer binder. | [138] |

| 950 | 1 | Calcined illite and limestone fillers were partially replaced with OPC. | [120] | |

| 950 | 0.5 | A higher soluble Si/Al ratio after treatment at 950 °C could improve the mechanical properties of the geopolymer binders. | [139] | |

| 850 | 2 | After treatment at this temperature, the illite clay became sufficiently pozzolanic for use in geopolymer composites. | [59] | |

| 875 | 3 | Achieved sufficient geopolymerisation and enhanced mechanical performance. | [119] | |

| 850 | 1 | An optimal quantity of a reactive and amorphous aluminosilicate precursor material has been observed at 850 °C. | [137] | |

| Bentonite | 800 | 3 | Bentonite thermally treated at this temperature demonstrated adequate pozzolanic performance, enabling it to replace 10% of the fly ash in geopolymer concrete. | [140] |

| 800 | 4 | Thermally activated bentonite partially substituted with OPC. A replacement rate of up to 15% was optimal for self-compacting concrete. | [141] | |

| 500 | 3 | Up to 30% replacement with OPC showed standard pozzolanic activity. | [102] | |

| 800 | 3 | A 20% replacement of OPC with calcined bentonite at 800 °C showed the highest pozzolanic activity compared to the replacements at 400 °C and 600 °C. | [142] | |

| 800 | - | A 20% replacement of OPC with calcined bentonite at 800 °C showed the highest pozzolanic activity compared to calcined bentonite at 700 °C. | [143] | |

| 800 | - | When calcined at this temperature, the maximum pozzolanic reactivity was observed with 30% replacement of OPC. | [144] | |

| Halloysite | 800 | 3 | Optimal pozzolanic activity was observed when the material was calcined at this temperature, with a 10% OPC replacement. | [105] |

| 750–850 | 2 | The highest geopolymerisation was observed at calcination temperatures between 750 °C and 850 °C, compared to 450 °C, 650 °C, and 1000 °C. | [145] | |

| 750 | 2 | Halloysite calcined at this temperature was able to participate in geopolymerisation along with fly ash and blast furnace slag. | [147] | |

| 750 | 2 | The highest level of geopolymerisation was observed at 750 °C, while the lowest was at 1000 °C. | [146] | |

| 800 | 2 | Halloysite calcined at this temperature exhibited the best pozzolanic activity in 3D-printed geopolymer composites. | [149] | |

| 750 | 1.6 | The highest pozzolanic reactivity was achieved when halloysite was calcined at 750 °C, and it sharply declined at 800 °C. | [148] | |

| Palygorskite | 800 | 1 (300 °C/h) | Enhanced pozzolanic reactivity was exhibited when 10% of the OPC was replaced. | [79] |

| 800 | 1 (5 °C/min) | Complete amorphisation and optimal pozzolanic activity were achieved when 20% of calcined palygorskite was replaced with OPC. | [82] | |

| 750 | 3 | The highest pozzolanic reactivity was observed when OPC replaced 20% of calcined palygorskite. | [150] | |

| 700 | 10 °C/min | Palygorskite calcined at 700 °C exhibited optimal pozzolanic reactivity in geopolymer. | [151] | |

| Sepiolite | 800 | 0.5 | Sepiolite calcined at this temperature exhibited optimal pozzolanic reactivity when used as a 20% replacement of OPC. | [152] |

| 900 | - | Optimal pozzolanic activity was observed with a 5% OPC replacement. | [153] | |

| 830 | - | Significant pozzolanic activity was observed when sepiolite was calcined at 830 °C, while sepiolite calcined at 370 °C and 570 °C showed no pozzolanic activity. | [120] |

3.2. Mechanical Activation

| Type of Clay | Grinding Body | Ball/Powder | Grinding Speed (rpm) and Time (min) | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolin | Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 11 | 400 rpm and 240 min | A nearly 100% degree of amorphisation and the highest strength were obtained. | [163] |

| Stainless steel ball of 3 mm in diameter | 25 | 500 rpm and 20 min | The highest amorphisation and strength were exhibited. | [34] | |

| Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 20 | 300 rpm and 60 min | Most of the hydroxyl groups were removed, and the kaolin was highly amorphous. | [164] | |

| 10 balls of 19 mm and five balls of 10 mm in diameter | 1.56 | 250 rpm and 60 min | Optimal activation was attained for geopolymer-based mortar. | [121] | |

| Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 20 | 350 rpm and 120 min | Exhibited optimal amorphisation and pozzolanic reactivity | [170] | |

| Steel balls ranging from 20 to 60 mm in diameter | 10 | 46 rpm and 1200 min | Kaolin was partially amorphised, and the specific surface area increased up to 31% at 20 h of grinding compared to 10 h. | [165] | |

| Illite | 30 mm diameter ball | 15 | 400 rpm and 240 min | The highest pozzolanic reactivity and strength were obtained. | [59] |

| Balls of 10 mm diameter | 20 | 500 rpm and 30 min | Optimal pozzolanic reactivity and strength increased by up to 40% with OPC replacement. | [122] | |

| Bentonite | Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 10 | 500 rpm and 60 min | Optimal hydroxylation and amorphisation occurred. A 20% replacement of OPC with activated bentonite resulted in an over 90% strength activity index. | [166] |

| Si3N4 balls of 20 mm in diameter | 10 | 300 rpm and 120 min | The particle size was considerably decreased. Optimal crystal structures were converted to amorphous states. | [167] | |

| Halloysite | Two types of grinding machines were used: (1) a planetary ball mill with 3 mm Zirconia balls, and (2) an energetic vibratory ring mill equipped with a tungsten carbide bowl and rings. | 50 (for planetary ball grinding) | 400 rpm and 1200 min (for planetary ball grinding), 15 min (vibratory ring mill) | Halloysite ground in a planetary grinder showed significantly lower pozzolanic reactivity than that ground in a vibratory ring mill grinder. | [148] |

| Palygorskite | Zirconia balls of 4–5 mm in diameter | 60 and 64 | 600 rpm and 15 min | The highest pozzolanic reactivity was achieved when palygorskite was ground at 600 rpm for 15 min. Whereas at 30 min, 45 min, and 60 min, pozzolanic reactivity sharply declined at the same grinding speed. | [168] |

| Sepiolite | Tungsten carbide balls of 10 mm in diameter | 25 | 600 rpm and 60 min | The highest degree of amorphisation occurred at 60 min, reaching 92.3%. In comparison, at 30 min, it was 89.9% with the same grinding speed. | [169] |

3.3. Chemical Activation

3.4. Importance of PSD and SSD in Clay Treatment and Concrete Performance

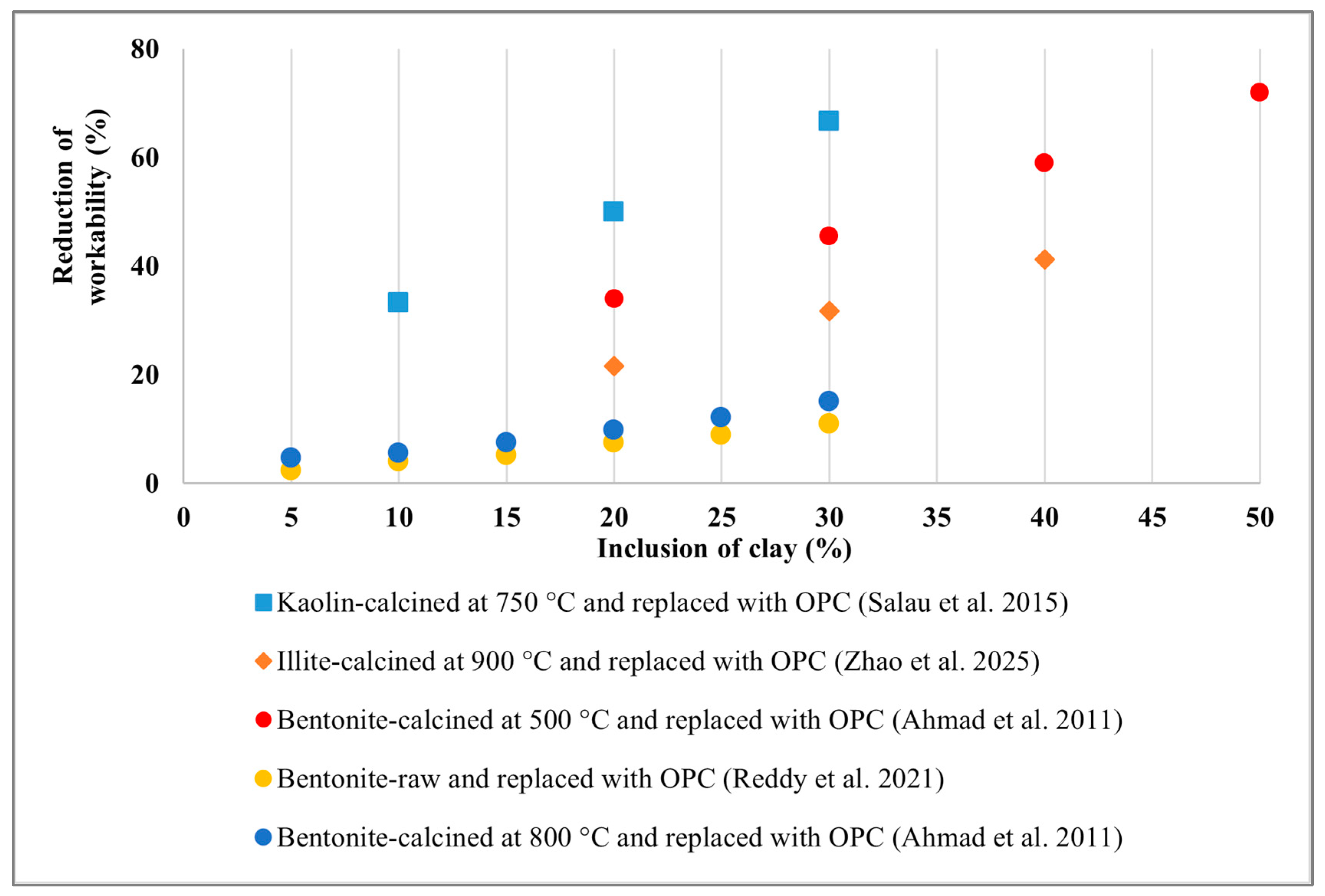

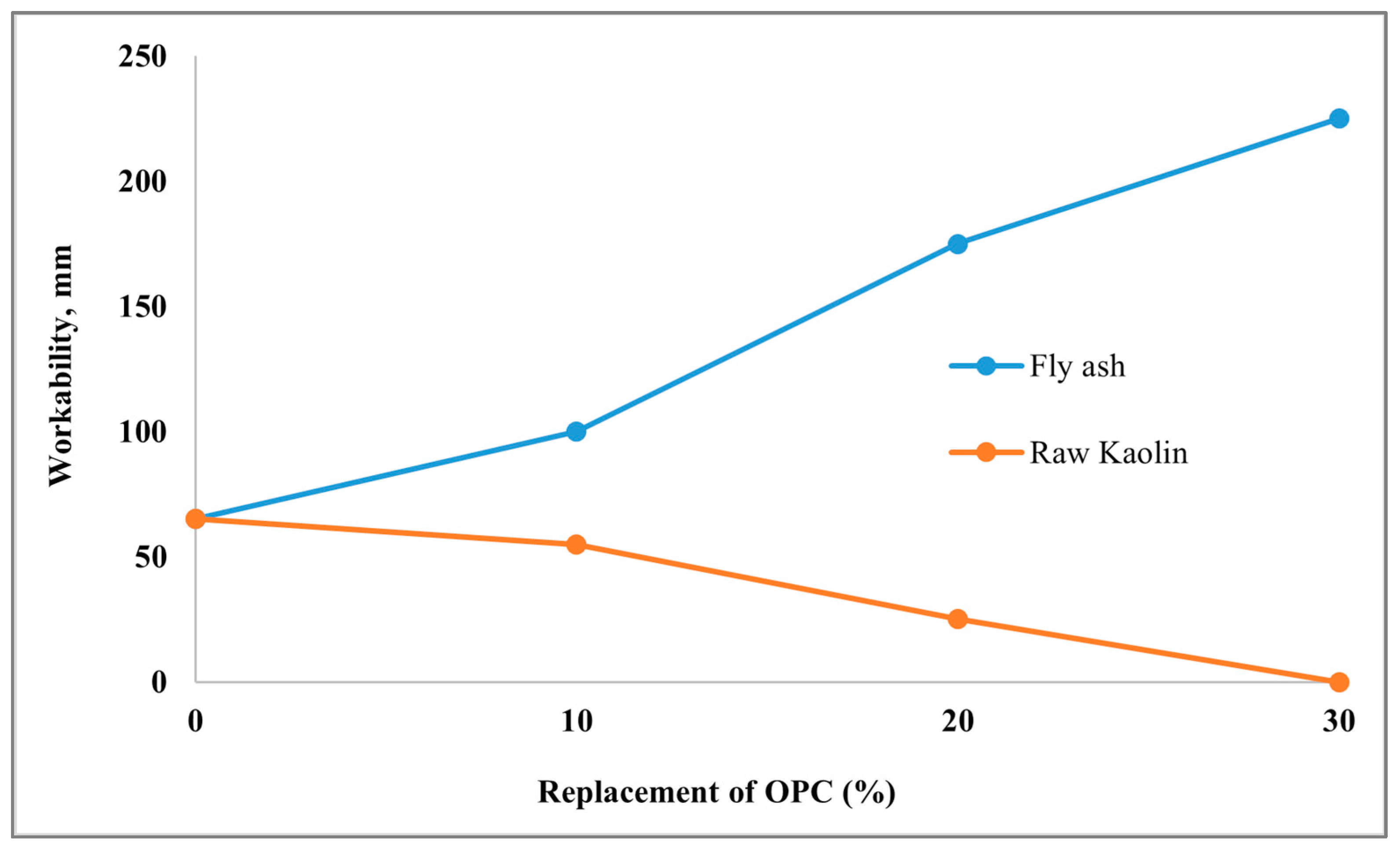

4. Effect of Clay on Concrete Workability

| Type of Clay | Pre-Treatment or Raw Condition of the Clay | Type of Composites | % of Clay Inclusion | Alkali/Binder (a/b) & Water/Binder (w/b) | Types of Workability Tests Performed | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolin | Raw | OPC with FA, OPC with kaolin (concrete) | 0%, 10%,20% and 30% OPC replaced by FA and kaolin | w/b 0.4 | Slump test | Inclusion of up to 30% fly ash significantly increased the slump value. The inclusion of kaolin from 10% to 30% dramatically reduced workability due to higher water demand and plastic behaviour. | [176] |

| Calcined | OPC with clay (concrete) | 0%, 10%,20% and 30% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.4 | Slump test | From 0% to 30%, kaolin calcined at 750 °C for 1 h, exhibited a medium slump value. The author suggested an appropriate w/b of 0.5 for higher workability. | [117] | |

| Illite | Calcined | OPC with calcined clay (CC) and limestone filler (LF) (mortar) | 0%, 20%, LF and 35% CC with OPC | w/b 0.5 | flow | Mortar with 35% CC and 20% LF, reduced slump flow by 8% and 5%, respectively, compared to the reference sample. | [120] |

| Calcined and mechanically activated | OPC with illite-rich waste shale (mortar) | 0%, 20%, 30% and 40% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.485 | flow | For calcined clay, the mortar’s flow decreased from 21.6% to 41.2% when 20% to 40% of the clay was replaced with cement, compared to the control mix, due to the high-water demand. On the other hand, the mechanically activated clay exhibited a reduced reduction in flow, which is 8.5% to 10.4% compared to the reference sample. | [122] | |

| Bentonite | Raw and calcined | Fly ash (FA) with raw and calcined clay, polypropylene fibre (PPF) (geopolymer concrete) | 0%, 10% FA replaced with raw and calcined clay. 0.5%, 0.75% and 1% PPF. | a/b 0.4 | slump | A reduced trend of slump value was observed for raw clay compared to calcined clay. Additionally, the inclusion of PPF negatively impacted workability due to internal friction. | [140] |

| Raw | OPC, bentonite, recycled aggregate (RAC) and natural aggregate (NAC) (concrete) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% clay replaced by OPC. 100% NAC and RAC used | w/b 0.5, 0.53, 0.56, 0.59, 0.63 | Slump | The inclusion of bentonite negatively affected the workability of both RAC and NAC concrete, due to bentonite’s higher surface area compared to OPC. However, the addition of superplasticiser improved workability. | [182] | |

| Calcined | OPC replaced by calcined clay (self-compacting concrete) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.4 | Slump flow, V-funnel and T-500 | The slump value decreased with increasing clay content in the concrete due to enhanced viscosity; therefore, the superplasticiser (SP) dose needed to be increased to achieve the required slump. For 25% and 30% of clay, SP doses were 1.2% and 1.67%, respectively. | [141] | |

| Calcined | OPC replaced by calcined clay (mortar) | 0%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 40% and 50% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.55 | Slump | The slump value was significantly reduced by almost 31.76% to 70.50% for 20% to 50% clay inclusion compared to the reference sample. This decrease in slump value is attributed to the higher water demand generated by the clay. | [102] | |

| Room temperature and calcined | OPC replaced by calcined clay (mortar) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% OPC replaced by clay | - | Slump | A reduced trend of workability was observed with the inclusion of both types of clays. However, calcined clay showed a greater reduction in workability than room-temperature clay due to its higher water absorption capacity. | [143] | |

| Raw | OPC replaced raw clay (concrete) | 0%, 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 18%, and 21% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.58 | Slump | The slump values steadily decreased as the clay inclusion increased. This downward trend is due to the clay’s larger surface area. | [103] | |

| Halloysite | Raw | OPC replaced raw clay (mortar) | 0%, 2.5% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.58 | Slump | A 33.33% reduction in the slump value was observed for the 2.5% halloysite clay sample compared to the control sample. | [181] |

| Palygorskite | Calcined | OPC replaced calcined clay (mortar) | 0% and 20% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.485 | Slump | A reduced trend in slump value was observed with the inclusion of calcined clay, due to its high water-absorption capacity. The required slump value can be maintained by increasing the superplasticiser dose while maintaining a constant water-to-binder (w/b) ratio. | [150] |

| Sepiolite | - | OPC replaced clay, and coarse aggregate (CA) was replaced by recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) (self-compacting concrete) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25% OPC replaced by clay. 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% CA replaced by RCA. | w/b 0.47 | Slump flow, T50, J-ring height, V-funnel flow, L-box | A combination of 41.78% fly ash (by weight of OPC) and sepiolite powder maintained workability within the required limits for all replacement levels by adjusting plasticiser dose. The highest flow value was achieved with a 25% clay and 50% RCA mixture. | [88] |

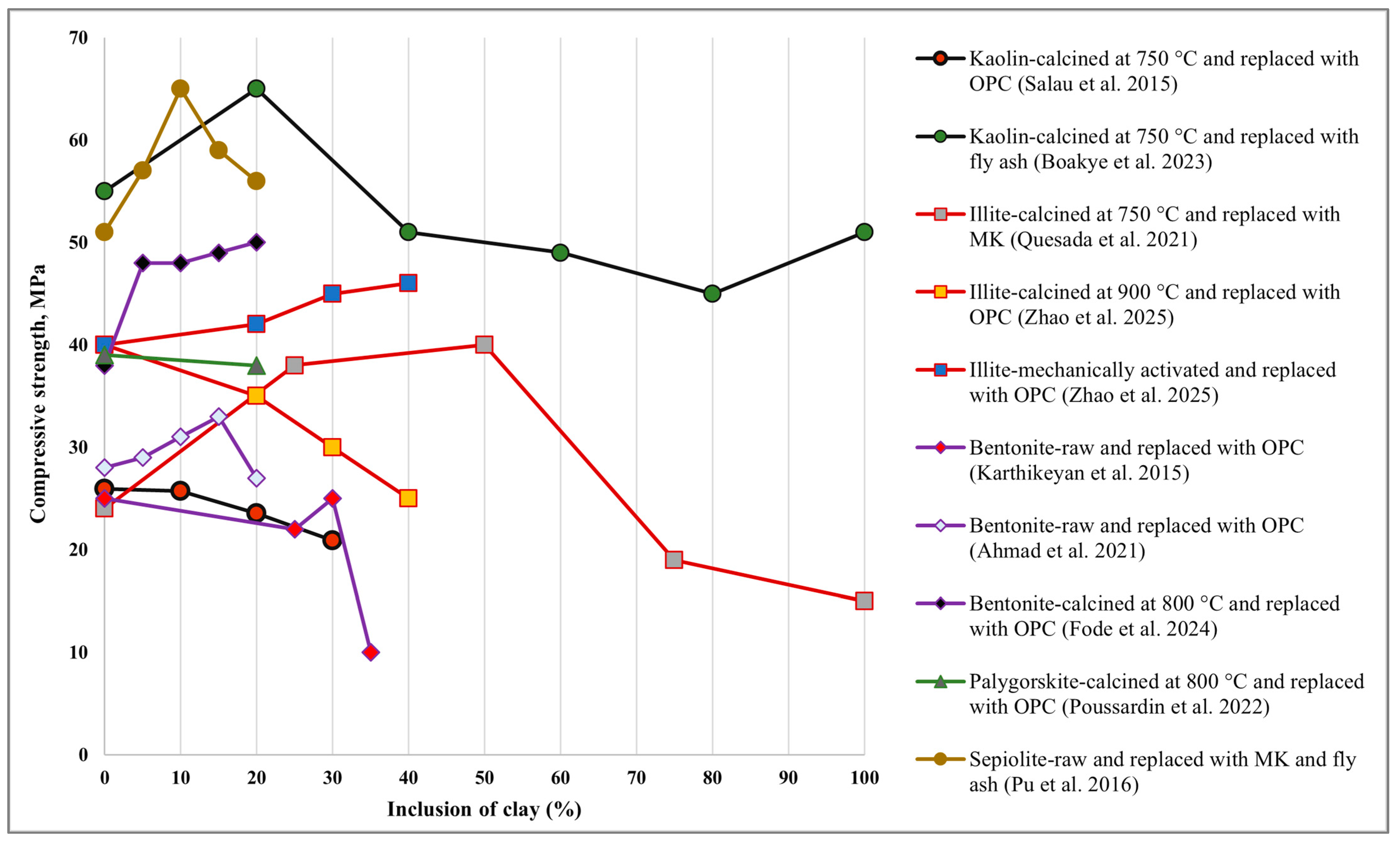

5. Effect of Clay on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete

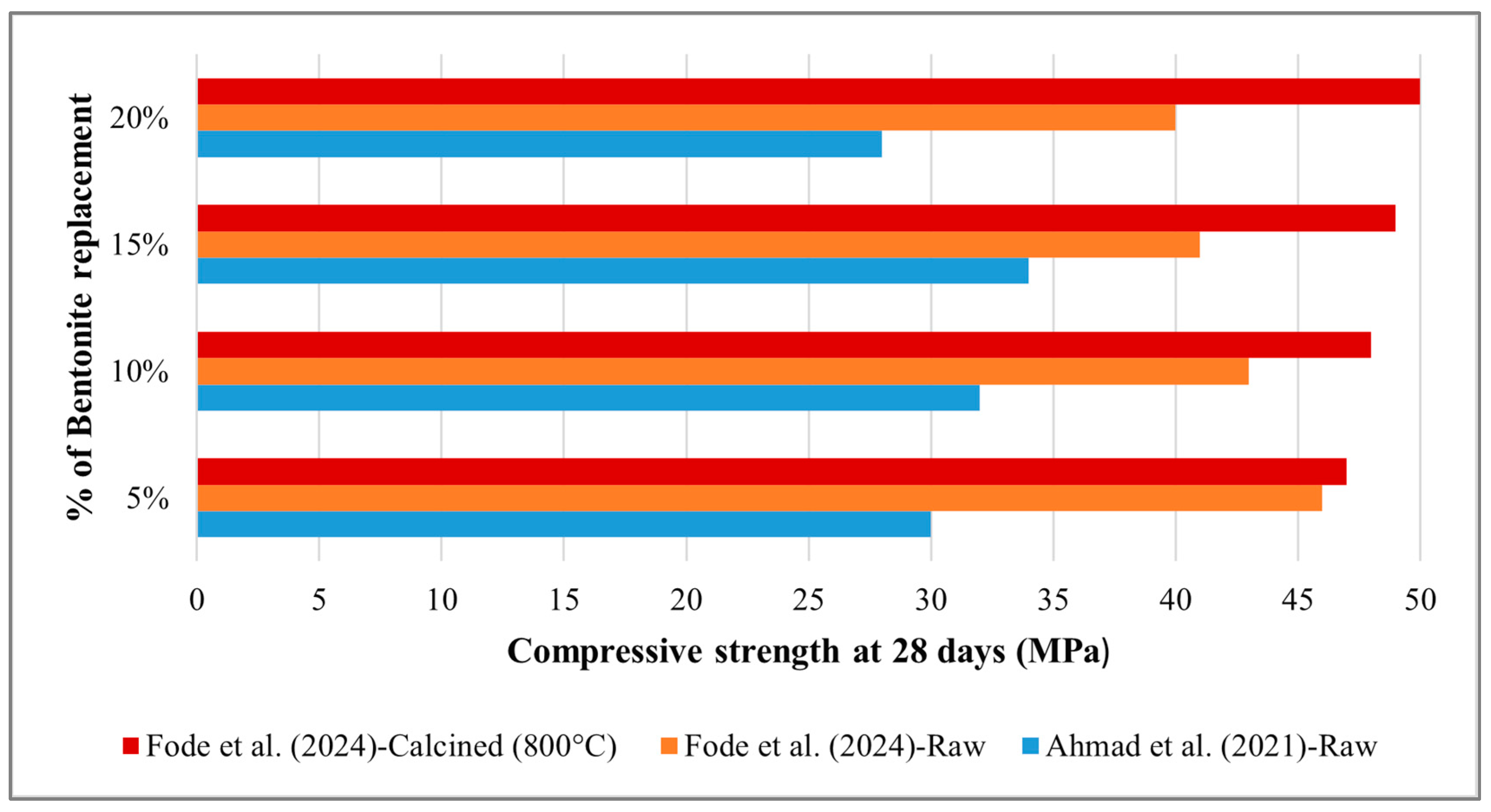

5.1. Compressive Strength

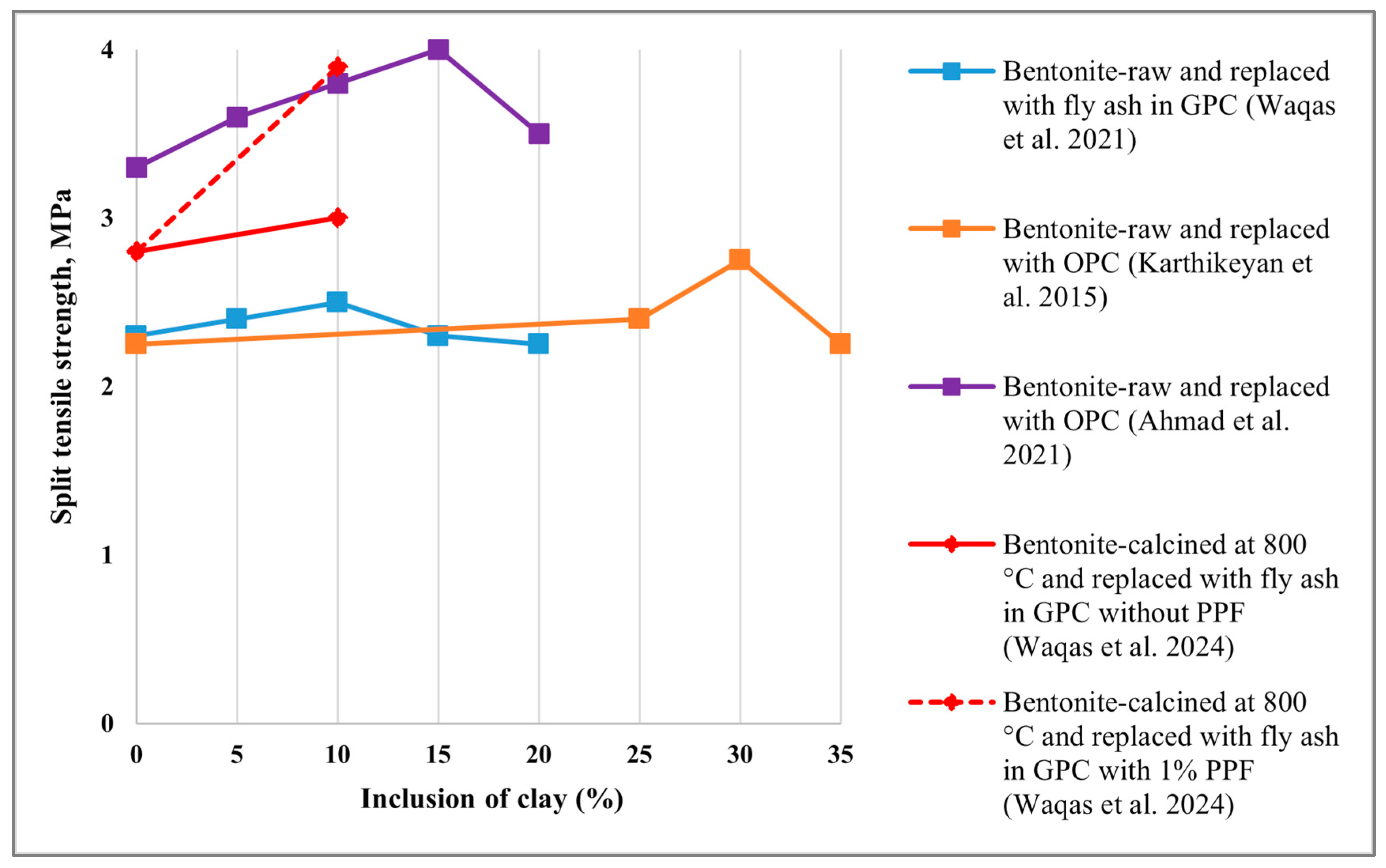

5.2. Split Tensile Strength

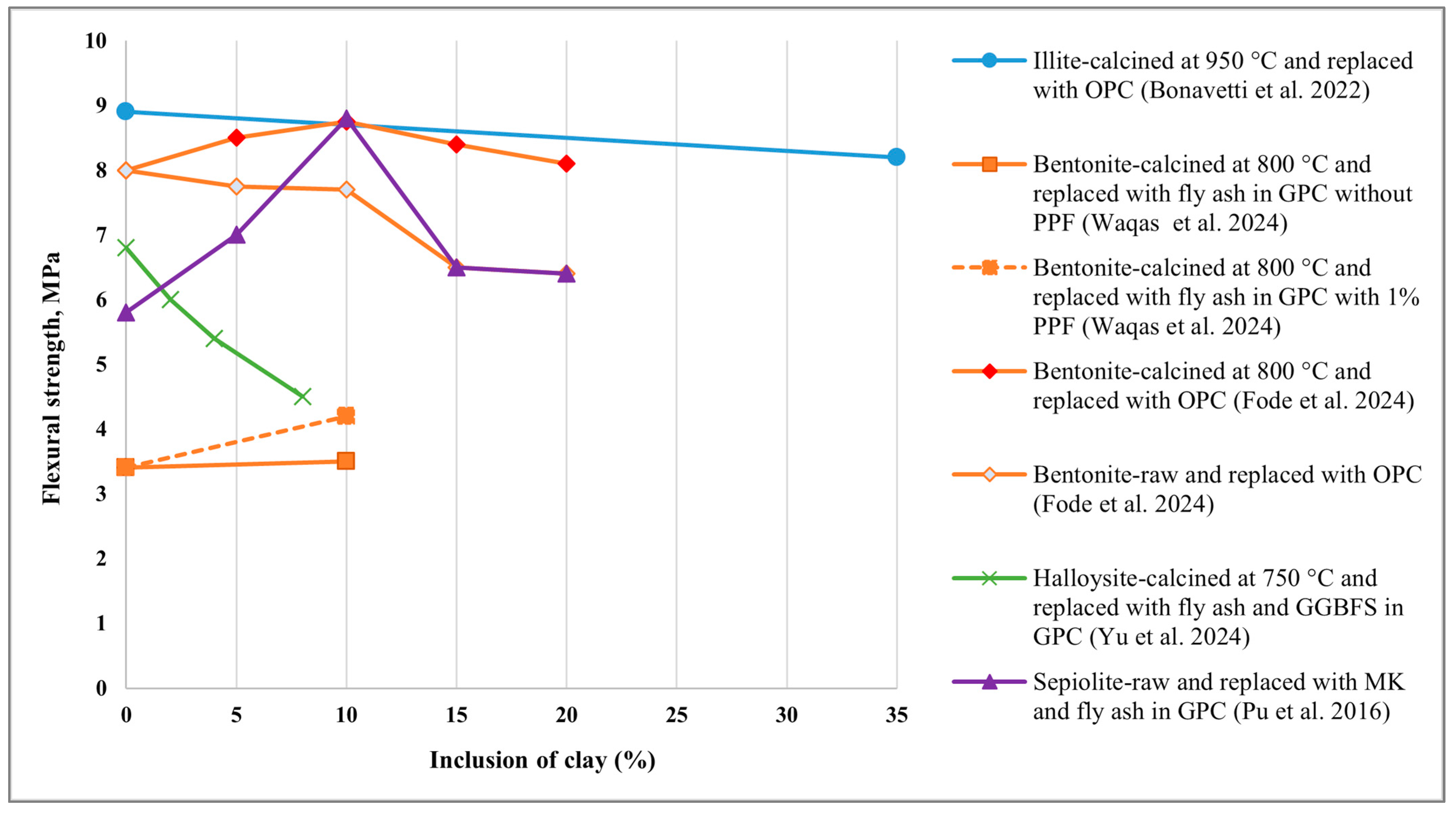

5.3. Flexural Strength

6. Prediction-Based Modelling of GPC and OPC Concrete

| Applied Model | Type of Binder | Prediction Properties | R2 | RMSE | MAE | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN LR LaR RR XGR | Amorphous or semicrystalline waste-based geopolymer | Compressive strength | 0.93 0.46 0.42 0.46 0.74 | 4.13 11.94 12.39 11.94 8.25 | 2.58 9.63 10.28 9.63 6.35 | The ANN model demonstrated the best accuracy, with an R2 of 0.93 and an RMSE of 4.13. | [196] |

| LR SVR ANN LSTM | Alkali-activated treated clay soil | Unconfined Compressive strength | 0.690 0.830 0.598 0.958 | 0.821 0.720 0.665 0.283 | 0.542 0.314 0.598 0.194 | The LSTM model showed the highest accuracy in predicting the strength. | [199] |

| GPR SVR | Expansive clay soil treated with hydrated-lime-activated rice husk ash | Unconfined Compressive strength | 0.9998 0.9998 | 0.4455 0.1408 | 0.3430 0.0514 | Both GPR and SVR models exhibited superior accuracy in predicting the strength. | [213] |

| MEP NLR ANN | OPC+Fly ash-based mortar | Compressive strength | 0.897 0.81 0.88 | 4.72 6.35 5.07 | 3.35 4.95 3.76 | The MEP model outperformed other models. | [200] |

| GEP XGB BR | OPC+ metakaolin (Mk)-based mortar | Compressive strength | 0.846 0.998 0.946 | 3.832 0.347 2.59 | 2.876 0.257 1.73 | XGB achieved the highest accuracy for strength determination, with a test R2 of 0.998, followed by a BR of 0.946. | [203] |

| BR AR | Fly ash-based geopolymer concrete | Compressive strength | 0.97 0.94 | 1.94 2.62 | 1.51 2.16 | The highest R2 value and the lowest error values (RMSE and MAE) indicated that the BR model was best suited for predicting strength. | [201] |

| ANFIS ANN | Fly ash-based geopolymer concrete | Compressive strength | 0.879 0.851 | 2.265 2.423 | 1.655 1.989 | Both models performed well in predicting compressive strength, but the ANFIS model was marginally better than the ANN. | [197] |

| RF-FIBO ADB-FIBO XGB-FIBO GBRT-FIBO | OPC+Bentonite-based concrete | Slump (S) Tensile strength (TS) Elastic modulus (E) | 0.943 (S) 0.962 (S) 0.966 (S) 0.966 (S) 0.949 (TS) 0.968 (TS) 0.977 (TS) 0.974 (TS) 0.943 (E) 0.962 (E) 0.966 (E) 0.966 (E) | 1.607 (S) 1.126 (S) 1.076 (S) 1.147 (S) 0.069 (TS) 0.053 (TS) 0.041 (TS) 0.049 (TS) 1.607 (E) 1.126 (E) 1.076 (E) 1.147 (E) | 1.149 (S) 0.747 (S) 0.797 (S) 0.835 (S) 0.052 (TS) 0.043 (TS) 0.030 (TS) 0.039 (TS) 1.149 (E) 0.747 (E) 0.797 (E) 0.835 (E | Among all models, XGB-FIBO achieved the highest accuracy for S and TS. In comparison, GBRT-FIBO excelled in predicting E. | [204] |

| ANN SVM | Bentonite+ OPC-based plastic concrete | Compressive strength | 0.9886 0.9648 | 0.3085 0.6744 | - - | The ANN model demonstrated the highest accuracy, with superior R2 and RMSE values, compared to the SVM. | [198] |

| MEP | OPC+Bentonite-based Plastic concrete | Slump Compressive strength Elastic modulus | 0.9998 0.9120 0.8299 | 0.5018 0.1897 258.9647 | 0.4272 0.1574 359.6862 | The MEP model demonstrated high accuracy in predicting the slump, compressive strength, and elastic modulus of bentonite-based concrete. | [205] |

| XGR-PSO XGR-GA XGR-DO | OPC+Bentonite-based concrete | Compressive strength | 0.974 0.968 0.969 | 0.038 0.041 0.040 | - - - | XGR-PSO exhibited the highest accuracy, with R2 = 0.974 and RMSE = 0.038, followed by XGR-DO and XGR-GA. | [206] |

| ANN MEP FQ LR | Fly ash-based geopolymer concrete | Compressive strength | 0.968 0.945 0.95 0.893 | 4.69 5.676 5.667 7.77 | - - - - | The ANN model achieved the highest accuracy, showcasing superior R2 and RMSE values compared to all other models. | [202] |

7. Durability and Microstructural Performance of Clay-Based GPC

7.1. Durability Performance

7.2. Microstructural Performance

8. Future Research Trends and Recommendations

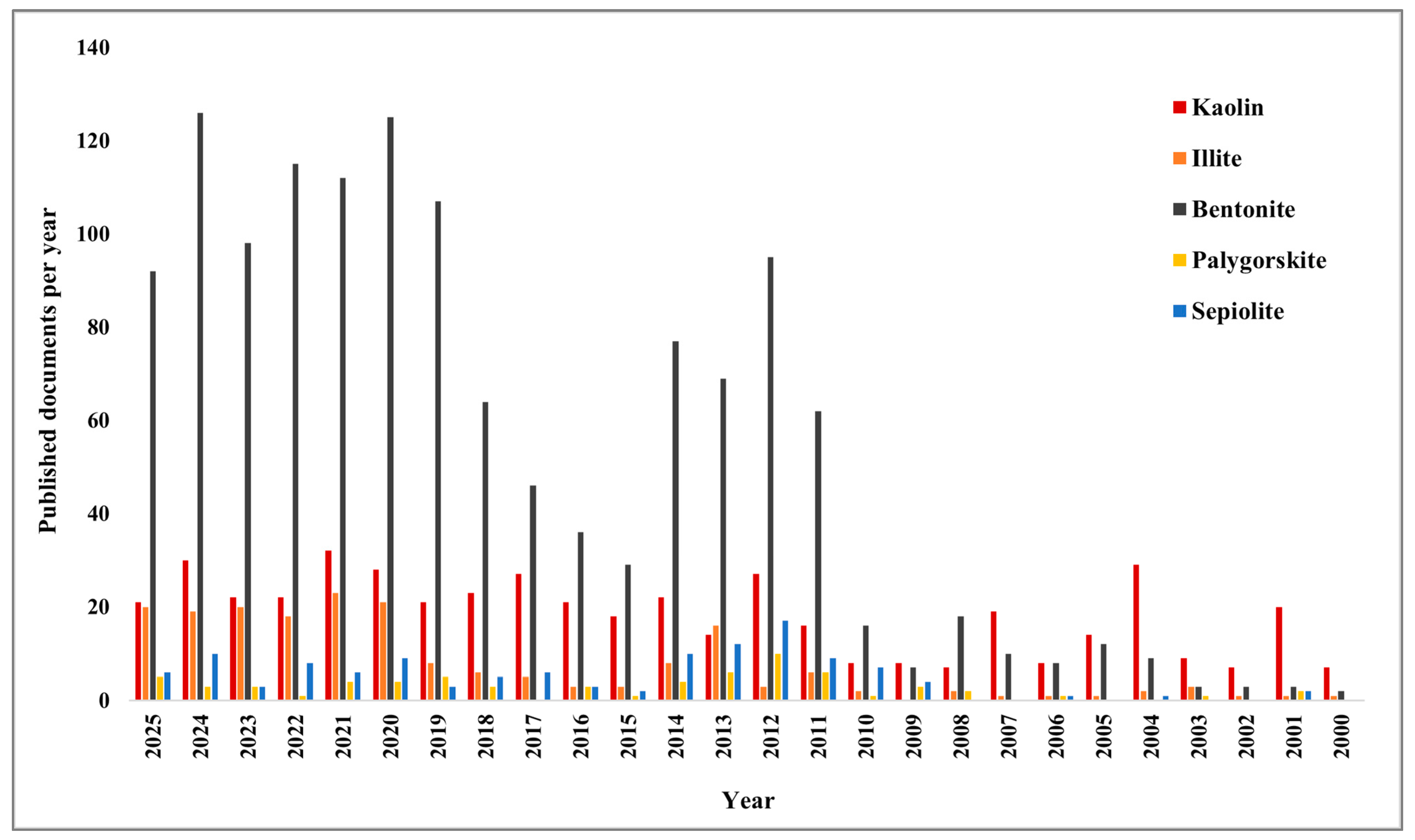

8.1. Research Trends

8.2. Recommendations for Real-World Applications

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Tam, S.M.; Riad, A.; Mohammed, N.; Al-Otaibi, A.; Youssf, O. Advancement of eco-friendly slag-based high-strength geopolymer concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 34, 1636–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, K.A.; Tahwia, A.M.; Youssf, O. Performance of eco-friendly ECC made of pre-treated crumb rubber and waste quarry dust. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahwia, A.M.; Aldulaimi, D.S.; Abdellatief, M.; Youssf, O. Physical, Mechanical and Durability Properties of Eco-Friendly Engineered Geopolymer Composites. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A.; Nasooti, M. A decision support tool for the cement industry to select energy efficiency measures. Energy Strat. Rev. 2020, 28, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakasan, S.; Palaniappan, S.; Gettu, R. Study of Energy Use and CO2 Emissions in the Manufacturing of Clinker and Cement. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. A 2020, 101, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Apurba, M.S.H. Effect of Inclusion of Recycled Waste Glass Powder in Geopolymer Concrete: A Review on Workability, Mechanical, Durability, and Micro-Structural Performance. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, F.; Jin, X.; Javed, M.F.; Akbar, A.; Shah, M.I.; Aslam, F.; Alyousef, R. Alyousef, Geopolymer concrete as sustainable material: A state of the art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 306, 124762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, V.; Muthramu, B.; Rebekhal, D. A review of sustainability assessment of geopolymer concrete through AI-based life cycle analysis. AI Civ. Eng. 2025, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijai, K.; Kumutha, R.; Vishnuram, B.G. Effect of types of curing on strength of geopolymer concrete. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2010, 5, 1419–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymers: Inorganic polymeric new materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1991, 37, 1633–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 59, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Palomo, A.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Geopolymer technology: The current state of the art. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, M.; Baklouti, S. Investigation of Phosphate-based geopolymers formation mechanism. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 562, 120777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansour, A.; Chow, C.L.; Feo, L.; Penna, R.; Lau, D. Green concrete: By-products utilization and advanced approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Singh, Y.; Singh, R.; Prakash, C.; Saxena, K.K.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.; Subramaniam, S. Development of GGBS-Based Geopolymer Concrete Incorporated with Polypropylene Fibers as Sustainable Materials. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, H.M. Effect of silica fume on the characterization of the geopolymer materials. Int. J. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2013, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiraghi, H.; Doostmohammadi, M.R. Effect of metakaolin and microsilica on the mechanical behavior of slag-based geopolymer concrete containing PP fibers. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Carrasco, M.; Puertas, F. Waste glass in the geopolymer preparation. Mechanical and microstructural characterisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L.K.; Collins, F.G. Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e) emissions: A comparison between geopolymer and OPC cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 43, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Singh, J.P.; Kumar, A. Effect of Particle Size on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash Based Geopolymers. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2019, 72, 1323–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.K.; Al-Ameri, R. A newly developed self-compacting geopolymer concrete under ambient condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 121822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhoub, O.A.; Nasr, E.-S.A.; Ali, Y.; Kohail, M. Properties of slag based geopolymer reactive powder concrete. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Saahir, M.; Garg, R.; Prajapat, U. Comparison of Mechanical Properties of Geopolymer Concrete vs Cement Concrete (Conventional Concrete). Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 2024, 8, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, A.; Siddique, R. Properties of low-calcium fly ash based geopolymer concrete incorporating OPC as partial replacement of fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 150, 792–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.C.; Singh, N. Impact of fly ash incorporation in soil systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 136, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; MacLeod, A.J.; Aldridge, L.P.; Collins, F.; Gates, W.P. Pozzolanic behaviour and environmental efficiency of heat-treated fines as a partial cement replacement in mortar mixes. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fořt, J.; Šál, J.; Ševčík, R.; Doleželová, M.; Keppert, M.; Jerman, M.; Záleská, M.; Stehel, V.; Černý, R. Biomass fly ash as an alternative to coal fly ash in blended cements: Functional aspects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 271, 121544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chaudhary, S. State of the art review on supplementary cementitious materials in India–II: Characteristics of SCMs, effect on concrete and environmental impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellings, R. Assessing, understanding and unlocking supplementary cementitious materials. RILEM Technol. Lett. 2016, 1, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migunthanna, J.; Rajeev, P.; Sanjayan, J. Waste Clay Brick as a Part Binder for Pavement Grade Geopolymer Concrete. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2023, 17, 1450–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alujas, A.; Fernández, R.; Quintana, R.; Scrivener, K.L.; Martirena, F. Pozzolanic reactivity of low-grade kaolinitic clays: Influence of calcination temperature and impact of calcination products on OPC hydration. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 108, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklay, A.; Yin, C.; Rosendahl, L. Flash calcination of kaolinite rich clay and impact of process conditions on the quality of the calcines: A way to reduce CO2 footprint from cement industry. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 1218–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials; Committee C-9 on Concrete and Concrete Aggregates. Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tole, I.; Habermehl-Cwirzen, K.; Rajczakowska, M.; Cwirzen, A. Activation of a raw clay by mechanochemical process: Effects of various parameters on the process efficiency and cementitious properties. Materials 2018, 11, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baki, V.A.; Ke, X.; Heath, A.; Calabria-Holley, J.; Terzi, C. Improving the pozzolanic reactivity of clay, marl and obsidian through mechanochemical or thermal activation. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivener, K.; Martirena, F.; Bishnoi, S.; Maity, S. Calcined clay limestone cements (LC3). Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojamberdiev, M.; Eminov, A.; Xu, Y. Utilization of muscovite granite waste in the manufacture of ceramic tiles. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellings, R.; Mertens, G.; Elsen, J. Supplementary cementitious materials. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 2012, 74, 211–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandapani, Y.; Marsh, A.T.M.; Rahmon, S.; Kanavaris, F.; Papakosta, A.; Bernal, S.A. Suitability of excavated London clay as a supplementary cementitious material: Mineralogy and reactivity. Mater. Struct. 2023, 56, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Martirena, F.; Scrivener, K.L. The origin of the pozzolanic activity of calcined clay minerals: A comparison between kaolinite, illite and montmorillonite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, H.; Su, S.; Chang, Q.; Komarneni, S. Hydrothermal synthesis of nano-kaolinite from K-feldspar. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 15611–15617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schankoski, R.A.; Pilar, R.; Prudêncio, L.R.; Ferron, R.D. Evaluation of fresh cement pastes containing quarry by-product powders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 133, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, H.; Samet, B. Effect of iron on pozzolanic activity of kaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.H.; Keeling, J. Fundamental and applied research on clay minerals: From climate and environment to nanotechnology. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 74, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, A.; Kazemi-Kamyab, H.; Snellings, R.; Naghizadeh, R.; Golestani-Fard, F.; Scrivener, K. Pozzolanic activity of mechanochemically and thermally activated kaolins in cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 77, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tironi, A.; Trezza, M.; Irassar, E.; Scian, A. Thermal Treatment of Kaolin: Effect on the Pozzolanic Activity. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2012, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitos, M.; Badogiannis, E.G.; Tsivilis, S.G.; Perraki, M. Pozzolanic activity of thermally and mechanically treated kaolins of hydrothermal origin. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 116–117, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Kodur, V.; Qi, S.L.; Cao, L.; Wu, B. Development of metakaolin–fly ash based geopolymers for fire resistance applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 55, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolovos, K.; Tsivilis, S.; Kakali, G. The effect of foreign ions on the reactivity of the CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-Fe2O3 system: Part II: Cations. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, R.F.; Du, Y.; Guo, X.M. Effect of Alumina on Crystallization Behavior of Calcium Ferrite in Fe2O3-CaO-SiO2-Al2O3 System. Materials 2022, 15, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J.; Davidovits, R. Geopolymer Institute Library Ferro-Sialate Geopolymers (-Fe-O-Si-O-Al-O-); Geopolymer Institute Library: Saint-Quentin, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lian, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Xue, C.; Yang, Z.; Lin, X. Phase formation, microstructure development, and mechanical properties of kaolin-based mullite ceramics added with Fe2O3. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2021, 18, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Chávez, M.; Vargas-Ramírez, M.; Herrera-González, A.M.; García-Serrano, J.; Cruz-Ramírez, A.; Romero-Serrano, J.A.; Sánchez-Alvarado, R.G. Thermodynamic analysis of the influence of potassium on the thermal behavior of kaolin raw material. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2020, 57, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman Jamo, H. Structural Analysis and Surface Morphology of Kaolin. Sci. World J. 2014, 9, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalqadir, M.; Gomari, S.R.; Pak, T.; Hughes, D.; Shwan, D. A comparative study of acid-activated non-expandable kaolinite and expandable montmorillonite for their CO2 sequestration capacity. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2024, 137, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heah, C.Y.; Kamarudin, H.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Binhussain, M.; Musa, L.; Nizar, I.K.; Ghazali, C.M.R.; Liew, Y. Effect of mechanical activation on kaolin-based geopolymers. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 479–481, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellings, R.; Reyes, R.A.; Hanein, T.; Irassar, E.F.; Kanavaris, F.; Maier, M.; Marsh, A.T.; Valentini, L.; Zunino, F.; Diaz, A.A. Paper of RILEM TC 282-CCL: Mineralogical characterization methods for clay resources intended for use as supplementary cementitious material. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, B.B.; Alomayri, T.; Hasan, A.; Kaze, C.R. Geopolymer concrete with metakaolin for sustainability: A comprehensive review on raw material’s properties, synthesis, performance, and potential application. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 25299–25324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzu, B.; Duc, M.; Djerbi, A.; Gautron, L. High performance illitic clay-based geopolymer: Influence of thermal/mechanical activation on strength development. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 258, 107445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wu, D.; Ren, Y.; Lin, J. Nanoarchitectonics of Illite-Based Materials: Effect of Metal Oxides Intercalation on the Mechanical Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, A.A.; Radin Mohamed, R.M.S.; Shamsuddin, R.; Ridzuan, M.B. A comprehensive review of synthesis kinetics and formation mechanism of geopolymers. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoc Thang, N. Geopolymerization: A Review on Physico-chemical Factors Influencing the Reaction Process. J. Polym. Compos. 2020, 8, 01–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, A.; Huang, L.; Babaahmadi, A. Characterisation, activation, and reactivity of heterogenous natural clays. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. Changes in conductivity of illite modified with cationic surfactant. J. Biotech. Res. 2024, 17, 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Vallina, D.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.D.; Santacruz, I.; Cuesta, A.; Aranda, M.A.; De la Torre, A.G. Supplementary cementitious material based on calcined montmorillonite standards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Li, Z.Y.; Ye, W.M.; Wang, Q. Swelling characteristics of montmorillonite mineral particles in Gaomiaozi bentonite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, Ş.; Metin, O.; Kurnaz, A. Determination of Major and Minor Oxides in Bentonite Samples From Quarries in Turkey, International Journal of Scientific Research, Research Paper. Chem. Sci. 2022, 9, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Noskov, A.V.; Alekseeva, O.V.; Yashkova, D.N.; Agafonov, A.V.; Shipko, M.N.; Stepovich, M.A.; Savchenko, E.S. Modification of Bentonite Properties with Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Surf. Investig. 2025, 19, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrunik, M.; Bajda, T. Modification of bentonite with cationic and nonionic surfactants: Structural and textural features. Materials 2019, 12, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimizadeh, M.; Wong, L.W.; Baifa, Z.; Sadjadi, S.; Auckloo, S.A.B.; Palaniandy, K.; Pasbakhsh, P.; Tan, J.B.L.; Singh, R.R.; Yuan, P. Halloysite clay nanotubes: Innovative applications by smart systems. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 251, 107319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubaie, N.; Al-Ameeri, A.; Mattar, S. The effects of using halloysite nano-clay in concrete on human health and environments: An overview study. Mater. Today Proc. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Tan, D.; Annabi-Bergaya, F. Properties and applications of halloysite nanotubes: Recent research advances and future prospects. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 112–113, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, B.B. Halloysite and kaolinite: Two clay minerals with geological and technological importance. Rev. Acad. Cienc. Zaragoza 2015, 70, 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Vašutová, V.; Bezdička, P.; Lang, K.; Hradil, D. Mineralogy of Halloysites and Their Interaction with Porphyrine. Ceramics–Silikáty 2013, 57, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Joussein, E.; Petit, S.; Churchman, J.; Theng, B.; Righi, D.; Delvaux, B. Halloysite clay minerals—A review. Clay Miner. 2005, 40, 383–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Noto, R.; Riela, S. Past, present and future perspectives on halloysite clay minerals. Molecules 2020, 25, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Leng, F.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Tian, W. Recent advances on surface modification of halloysite nanotubes for multifunctional applications. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Selective modification of inner surface of halloysite nanotubes: A review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2017, 6, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poussardin, V.; Paris, M.; Wilson, W.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Deneele, D. Calcined palygorskite and smectite bearing marlstones as supplementary cementitious materials. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, A. Recent progress in dispersion of palygorskite crystal bundles for nanocomposites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 119, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Sarkar, B.; Naidu, R. Influence of thermally modified palygorskite on the viability of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 134, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poussardin, V.; Roux, V.; Wilson, W.; Paris, M.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Deneele, D. Calcined Palygorskites as Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Clays Clay Miner. 2022, 70, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, K.C.M.; dos Santos, M.D.S.F.; Santos, M.R.M.C.; Oliveira, M.E.R.; Carvalho, M.W.N.C.; Osajima, J.A.; Filho, E.C.d.S. Effects of acid treatment on the clay palygorskite: XRD, surface area, morphological and chemical composition. Mater. Res. 2014, 17, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkacher, N.; Iggui, K.; Mekhania, Z.A.; Benhamida, A.; Djermoune, A.; Merzeg, F.A.; Satha, H.; Layachi, A. Influence of surface modification of Algerian palygorskite with triethoxyoctylsilane as a hydrophobic agent for enhanced performance. J. Coatings Technol. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Han, G.; Wang, F.; Liang, J. Sepiolite nanomaterials: Structure, properties and functional applications. In Nanomaterials from Clay Minerals: A New Approach to Green Functional Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 135–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Hitzky, E.; Darder, M.; Fernandes, F.M.; Wicklein, B.; Alcântara, A.C.S.; Aranda, P. Fibrous clays based bionanocomposites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1392–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.R.; Hong, Z.Q.; Zhan, B.J.; Tang, W.; Cui, S.C.; Kou, S.C. Effect of acid treatment on the reactivity of natural sepiolite used as a supplementary cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 316, 125860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeline Jemina, J.Y.; Sophia, M.; Talluri, R.; Muthuraman, U. Durability Studies on Self-Compacting Concrete Containing Sepiolite Powder and Recycled Coarse Aggregates. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.I.; Ruiz-García, C.; Ruiz-Hitzky, E. From old to new inorganic materials for advanced applications: The paradigmatic example of the sepiolite clay mineral. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 235, 106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilir, K.; Çağlar, U. Effects of mechanical activation parameters on the rheological behavior of acid-treated sepiolite. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2025, 61, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvi, C.; Sivakumar, M.; Subadevi, R. Activation of Sepiolite by Various Acid Treatments. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, P.; Wang, H.; Guan, S.; Cui, J. Surface modification of sepiolite and its application in one-component silicone potting adhesive. e-Polymers 2024, 24, 20240051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneyisi, E.; Mermerdaş, K. Comparative study on strength, sorptivity, and chloride ingress characteristics of air-cured and water-cured concretes modified with metakaolin. Mater. Struct. 2007, 40, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejmelková, E.; Pavlíková, M.; Keppert, M.; Keršner, Z.; Rovnaníková, P.; Ondráček, M.; Sedlmajer, M.; Černý, R. High performance concrete with Czech metakaolin: Experimental analysis of strength, toughness and durability characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Shui, Z.; Chen, W.; Shen, C. Effects of metakaolin, silica fume and slag on pore structure, interfacial transition zone and compressive strength of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, J.M.; Hibbert, J.J. Selected engineering properties of concrete incorporating slag and metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2005, 19, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akhras, N.M. Durability of metakaolin concrete to sulfate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1727–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Deng, C.; Yu, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, G. Effective removal of lead ions from aqueous solution using nano illite/smectite clay: Isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic modeling of adsorption. Water 2018, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Hussein, I.A.; Mahmoud, M. Introduction to reservoir fluids and rock properties. In Developments in Petroleum Science; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaneme, G.U.; Mbadike, E.M. optimisation of strength development of bentonite and palm bunch ash concrete using fuzzy logic. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushnood, R.A.; Rizwan, S.A.; Memon, S.A.; Tulliani, J.-M.; Ferro, G.A. Experimental Investigation on Use of Wheat Straw Ash and Bentonite in Self-Compacting Cementitious System. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 832508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Barbhuiya, S.A.; Elahi, A.; Iqbal, J. Effect of Pakistani bentonite on properties of mortar and concrete. Clay Miner. 2011, 46, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Arsalan, R.; Khan, S.; Lo, T.Y. Utilization of Pakistani bentonite as partial replacement of cement in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, J.; Riaz, M.; Naseer, A.; Rehman, F.; Khan, A.; Ali, Q. Pakistani bentonite in mortars and concrete as low cost construction material. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 45, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haw, T.T.; Hart, F.; Rashidi, A.; Pasbakhsh, P. Sustainable cementitious composites reinforced with metakaolin and halloysite nanotubes for construction and building applications. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 188, 105533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, M.T.A. A spectroscopic study on the effect of acid concentration on the physicochemical properties of calcined halloysite nanotubes. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 60, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, M.; Tian, W.; Tang, N.; Gao, L. Effect of isomorphic replacement of palygorskite on its heavy metal adsorption performance. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 085218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, F.; Ammous, A.; Tlili, A.; Kallel, N. Geological setting, geochemical, textural, and genesis of palygorskite in Eocene carbonate deposits from Central Tunisia. Carbonates Evaporites 2024, 39, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolathayar, S.; Sreekeshava, K.S.; Vinod, N.; Menon, C. Recent Advances in Building Materials and Technologies: Select Proceedings of IACESD 2023; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Walczyk, A.; Michalik, A.; Napruszewska, B.; Kryściak-Czerwenka, J.; Karcz, R.; Duraczyńska, D.; Socha, R.; Olejniczak, Z.; Gaweł, A.; Klimek, A.; et al. New insight into the phase transformation of sepiolite upon alkali activation: Impact on composition, structure, texture, and catalytic/sorptive properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 195, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, J.; Kurda, R. The past and future of sustainable concrete: A critical review and new strategies on cement-based materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 123558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SRPS EN 196-3:2017; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 3: Determination of Setting Times and Soundness. iTeh, Inc.: Newark, DE, USA, 2017.

- Mohamed, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A. Metakaolin in ultra-high-performance concrete: A critical review of its effectiveness as a green and sustainable admixture. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklay, A.; Yin, C.; Rosendahl, L.; Bøjer, M. Calcination of kaolinite clay particles for cement production: A modeling study. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 61–62, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K. Dissolution processes, hydrolysis and condensation reactions during geopolymer synthesis: Part I-Low Si/Al ratio systems. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 2997–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kota, P.; Geopolymer, S. Elements of Geopolymer Concrete. In Geopolymer Concrete; Springer Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salau, M.; Osemeke, O. Effects of Temperature on the Pozzolanic Characteristics of Metakaolin-Concrete. Phys. Sci. Int. J. 2015, 6, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albidah, A.; Altheeb, A.; Alrshoudi, F.; Abadel, A.; Abbas, H.; Al-Salloum, Y. Bond performance of GFRP and steel rebars embedded in metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete. Structures 2020, 27, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietel, J.; Warr, L.N.; Bertmer, M.; Steudel, A.; Grathoff, G.H.; Emmerich, K. The importance of specific surface area in the geopolymerization of heated illitic clay. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 139, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavetti, V.L.; Castellano, C.C.; Irassar, E.F. Designing general use cement with calcined illite and limestone filler. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 230, 106700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounsi, A.D.; Lecomte-Nana, G.L.; Djétéli, G.; Blanchart, P. Kaolin-based geopolymers: Effect of mechanical activation and curing process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 42, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Ozersky, A.; Khomyakov, A.; Peterson, K. Comparison of thermal and mechanochemical activation for enhancing pozzolanic reactivity of illite-rich shale. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 160, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfo-Ansah, J.; Atiemo, E.; Boakye, K.A.; Momade, Z. Comparative Study of Chemically and Mechanically Activated Clay Pozzolana. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2014, 05, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayati, B.; Newport, D.; Wong, H.; Cheeseman, C. Acid activated smectite clay as pozzolanic supplementary cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 162, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwiti, M.J.; Karanja, J.; Muthengia, W.J. Properties of activated blended cement containing high content of calcined clay. Heliyon 2018, 4, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.U.; Alam, S.; Gul, S.; Muhammad, K. Chemical activation of clay in cement mortar, using calcium chloride. Adv. Cem. Res. 2013, 25, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperinck, S.; Raiteri, P.; Marks, N.; Wright, K. Dehydroxylation of kaolinite to metakaolin—A molecular dynamics study. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 21, 2118–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.E.; Provis, J.L.; Proffen, T.; Riley, D.P.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Combining density functional theory (DFT) and pair distribution function (PDF) analysis to solve the structure of metastable materials: The case of metakaolin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 3239–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassa, A.E.; Shibeshi, N.T.; Tizazu, B.Z. Kinetic analysis of dehydroxylation of Ethiopian kaolinite during calcination. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 12837–12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.Z.; Pontikes, Y.; Elsen, J.; Cizer, Ö. Comparing the reactivity of different natural clays under thermal and alkali activation. RILEM Technol. Lett. 2019, 4, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridi-Bennadji, F.; Beneu, B.; Laval, J.; Blanchart, P. Structural transformations of Muscovite at high temperature by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Appl. Clay Sci. 2008, 38, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, M.; Comel, C. Hydration reaction and hardening of calcined clays and related minerals III. Influence of calcination process of kaolinite on mechanical strengths of hardened metakaolinite. Cem. Concr. Res. 1983, 13, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía De Gutiérrez, R.; Torres, J.; Vizcayno, C.; Castello, R. Influence of the calcination temperature of kaolin on the mechanical properties of mortars and concretes containing metakaolin. Clay Miner. 2008, 43, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimbi, A.; Tchakoute, H.K.; Njopwouo, D. Effects of calcination temperature of kaolinite clays on the properties of geopolymer cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2805–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adufu, Y.D.; Sore, S.O.; Nshimiyimana, P.; Ahouandjinou, K.D.; Messan, A.; Escadeillas, G. Durability behaviors of calcined kaolin clay-based geopolymer concrete containing different calcium compounds and cured in ambient sub-Saharan climate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 465, 140195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhua, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Huajun, Z.; Yue, C. Role of water in the synthesis of calcined kaolin-based geopolymer. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 43, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Bernsmeier, D.; Grathoff, G.H.; Warr, L.N. The influence of alkali activator type, curing temperature and gibbsite on the geopolymerization of an interstratified illite-smectite rich clay from Friedland. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 135, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, A.; Hohmann, M.; Posern, K.; Brendler, E. The suitability of thermally activated illite/smectite clay as raw material for geopolymer binders. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 46, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffarth, T.; Hohmann, M.; Posern, K.; Kaps, C. Effect of thermal pre-treatment conditions of common clays on the performance of clay-based geopolymeric binders. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 73, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, R.M.; Zaman, S.; Alkharisi, M.K.; Butt, F.; Alsuhaibani, E. Influence of Bentonite and Polypropylene Fibers on Geopolymer Concrete. Sustainability 2024, 16, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidani, Z.E.A.; Benabed, B.; Abousnina, R.; Gueddouda, M.K.; Kadri, E.H. Experimental investigation on effects of calcined bentonite on fresh, strength and durability properties of sustainable self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 117062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fode, T.A.; Jande, Y.A.C.; Kivevele, T. Effects of raw and different calcined bentonite on durability and mechanical properties of cement composite material. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.S.; Reddy, M.A.K. Optimization of Calcined Bentonite Caly Utilization in Cement Mortar using Response Surface Methodology. Int. J. Eng. 2021, 34, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Skibsted, J. Thermal activation of a pure montmorillonite clay and its reactivity in cementitious systems. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 11464–11477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, H.; Yuan, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Deng, L.; Liu, D. Geopolymerization of halloysite via alkali-activation: Dependence of microstructures on precalcination. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 185, 105375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, H.; Yuan, P.; Deng, L.; Zhong, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, D. Novel acid-based geopolymer synthesized from nanosized tubular halloysite: The role of precalcination temperature and phosphoric acid concentration. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 110, 103601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Fahimizadeh, M.; Pantongsuk, T.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, P. Ternary geopolymer with calcined halloysite: Impact on mechanical properties and microstructure. Clay Miner. 2024, 59, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.J.D.; Brew, D.R.M.; Fletcher, R.A.; Vagana, R. Formation of aluminosilicate geopolymers from 1:1 layer-lattice minerals pre-treated by various methods: A comparative study. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 4667–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, N.; Kuenzel, C.; Gundlach, C.; Kempen, P.; Mehrali, M. Halloysite reinforced 3D-printable geopolymers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 136, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, G.; Aspiotis, K.; Badogiannis, E.; Tsivilis, S.; Perraki, M. Influence of mineralogy and calcination temperature on the behavior of palygorskite clay as a pozzolanic supplementary cementitious material. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 232, 106797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Johari, I.; Othman, N. Optimization and characterization of sustainable geopolymer mortars based on palygorskite clay, water glass, and sodium hydroxide. Open Eng. 2024, 14, 20220546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.R.; Hong, Z.Q.; Zhan, B.J.; Cui, S.C.; Kou, S.C. Pozzolanic activity of calcinated low-grade natural sepiolite and its influence on the hydration of cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 309, 125076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, R.C.; Subasi, S.; Marasli, M. The effect of crude and calcined sepiolite on some physical and mechanical properties of glass fiber reinforced Concrete. Rom. J. Mater. 2023, 53, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Badogiannis, E.; Kakali, G.; Tsivilis, S. Metakaolin as supplementary cementitious material. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2005, 81, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, K.; Khorami, M. Impact of Low-Reactivity Calcined Clay on the Performance of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Mortar. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, Z.; Mohsen, A.; Soltan, A.M.; Kohail, M. Optimization of kaolin into Metakaolin: Calcination Conditions, mix design and curing temperature to develop alkali activated binder. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter-Vermaak, S.S.; Potgieter, J.H. Metakaolin as an Extender in South African Cement. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2006, 18, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Lange, S.C.; Riding, K.A.; Juenger, M.C.G. Increasing the reactivity of metakaolin-cement blends using zinc oxide. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcayno, C.; de Gutiérrez, R.; Castello, R.; Rodriguez, E.; Guerrero, C. Pozzolan obtained by mechanochemical and thermal treatments of kaolin. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 49, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Cui, T.; Jia, Z.; Sun, S.; Anning, C.; Qiu, J.; Lyu, X. Effect of anhydrite on hydration properties of mechanically activated muscovite in the presence of calcium oxide. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 196, 105742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Zang, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, P.; Qiu, J.; Lyu, X. Effect of Mechanical Activation on the Pozzolanic Activity of Muscovite. Clays Clay Miner. 2019, 67, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollanders, S.; Adriaens, R.; Skibsted, J.; Cizer, Ö.; Elsen, J. Pozzolanic reactivity of pure calcined clays. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 132–133, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balczár, I.; Korim, T.; Kovács, A.; Makó, É. Mechanochemical and thermal activation of kaolin for manufacturing geopolymer mortars–Comparative study. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 15367–15375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañosa, J.; de la Rosa, J.C.; Silvello, A.; Maldonado-Alameda, A.; Chimenos, J.M. Kaolinite structural modifications induced by mechanical activation. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 238, 106918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, B.; Radonjanin, V.; Malešev, M.; Zdujić, M.; Mitrović, A. Effects of mechanical and thermal activation on pozzolanic activity of kaolin containing mica. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 123, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, V.A.; Ke, X.; Heath, A.; Calabria-Holley, J.; Terzi, C.; Sirin, M. The impact of mechanochemical activation on the physicochemical properties and pozzolanic reactivity of kaolinite, muscovite and montmorillonite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 162, 106962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchuk, I. Performance of Thermal-, Acid-, and Mechanochemical-Activated Montmorillonite for Environmental Protection from Radionuclides U(VI) and Sr(II). Eng 2023, 4, 2141–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, G.; Badogiannis, E.; Tsivilis, S.; Perraki, M. Thermally and mechanically treated Greek palygorskite clay as a pozzolanic material. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 215, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunç, T.; Özkan Toplan, H.; Yıldız, K. Thermal behavior of mechanically activated sepiolite. TOJSAT Online J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Mañosa, J.; Alvarez-Coscojuela, A.; Maldonado-Alameda, A.; Chimenos, J.M. A Lab-Scale Evaluation of Parameters Influencing the Mechanical Activation of Kaolin Using the Design of Experiments. Materials 2024, 17, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S. Potential Utilization of Loess in Grouting Materials: Effects of Grinding Time and Calcination Temperature. Minerals 2024, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzenda, T.R.; Georget, F.; Matschei, T. The effect of the physico-chemical properties of (calcined) clays on the rheological properties and early hydration of calcined clay-limestone cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanein, T.; Thienel, K.C.; Zunino, F.; Marsh, A.T.M.; Maier, M.; Wang, B.; Canut, M.; Juenger, M.C.G.; Ben Haha, M.; Avet, F.; et al. Clay calcination technology: State-of-the-art review by the RILEM TC 282-CCL. Mater. Struct. 2021, 55, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipour, I.; Khayat, K.H. Effect of particle-size distribution and specific surface area of different binder systems on packing density and flow characteristics of cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 78, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehdi, M.L. Clay in cement-based materials: Critical overview of state-of-the-art. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 51, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghais, A.; Ahmed, D.; Siddig, E.; Elsadig, I.; Albager, S. Performance of Concrete with Fly Ash and Kaolin Inclusion. Int. J. Geosci. 2014, 5, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Tufail, R.F.; Aslam, F.; Mosavi, A.; Alyousef, R.; Javed, M.F.; Zaid, O.; Khan Niazi, M.S. A step towards sustainable self-compacting concrete by using partial substitution of wheat straw ash and bentonite clay instead of cement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, S.E.; Rickert, J. Suitability of natural calcined clays as supplementary cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 95, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyan, H.; Önal, M.; Sarikaya, Y. The Effect of Heating on the Surface Area, Porosity and Surface Acidity of a Bentonite. Clays Clay Miner. 2006, 54, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkodi, R.; Dharmar, S.; Nagan, S. Experimental Study on Fiber Reinforced Self-Compacting Geopolymer Mortar. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng. 2015, 4, 968–977. [Google Scholar]

- Dungca, J.R.; Edrada, J.E.B.; Eugenio, V.A.; Fugado, R.A.S.; Li, E.S.C. The combined effects of nano-montmorillonite and halloysite nanoclay on the workability and compressive strength of concrete. Int. J. GEOMATE 2019, 17, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, B.; Elahi, A.; Barbhuiya, S.; Ali, B. Mechanical and durability performance of recycled aggregate concrete incorporating low calcium bentonite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliche-Quesada, D.; Bonet-Martínez, E.; Pérez-Villarejo, L.; Castro, E.; Sánchez-Soto, P.J. Effects of an Illite Clay Substitution on Geopolymer Synthesis as an Alternative to Metakaolin. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lodeiro, I.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, A.; Macphee, D.E. Effect of calcium additions on N-A-S-H cementitious gels. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 93, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, M.; Ramachandran, P.R.; Nandhini, A.; Vinodha, R. Application on partial substitute of cement by bentonite in concrete. Int. J. Chem. Technol. Res. 2015, 8, 384–388. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lai, Z.; Yan, T.; He, X.; Wu, J.; Lu, Z.; Lv, S. Influence of various bentonites on the mechanical properties and impermeability of cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 241, 118015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S.; Duan, P.; Yan, C.; Ren, D. Influence of sepiolite addition on mechanical strength and microstructure of fly ash-metakaolin geopolymer paste. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016, 27, 2470–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.; Larrain, M.M.M.; Zaman, M.; Pozadas, V. Relationships between compressive and flexural strengths of concrete based on fresh field properties. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.K.; Awang, A.Z.; Omar, W. Structural and material performance of geopolymer concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oderji, S.Y.; Chen, B.; Ahmad, M.R.; Shah, S.F.A. Fresh and hardened properties of one-part fly ash-based geopolymer binders cured at room temperature: Effect of slag and alkali activators. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindaprasirt, P.; De Silva, P.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K.; Hanjitsuwan, S. Effect of SiO2 and Al2O3 on the setting and hardening of high calcium fly ash-based geopolymer systems. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 4876–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanphan, S.; Wannagon, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Jiemsirilers, S. Reaction mechanisms of calcined kaolin processing waste-based geopolymers in the presence of low alkali activator solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 221, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Arif, M.; Shariq, M. Effect of curing condition on the mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoo-Ngernkham, T.; Phiangphimai, C.; Damrongwiriyanupap, N.; Hanjitsuwan, S.; Thumrongvut, J.; Chindaprasirt, P. A Mix Design Procedure for Alkali-Activated High-Calcium Fly Ash Concrete Cured at Ambient Temperature. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 2460403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Keller, J.; Bond, P.L.; Yuan, Z. Predicting concrete corrosion of sewers using artificial neural network. Water Res. 2016, 92, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Provath, A.M.; Islam, G.M.S.; Islam, T. Strength Prediction of Geopolymer Concrete With Wide-Ranged Binders and Properties Using Artificial Neural Network. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 8534390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, D.V.; Ly, H.B.; Trinh, S.H.; Le, T.T.; Pham, B.T. Artificial intelligence approaches for prediction of compressive strength of geopolymer concrete. Materials 2019, 12, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanizadeh, A.R.; Abbaslou, H.; Amlashi, A.T.; Alidoust, P. Modeling of bentonite/sepiolite plastic concrete compressive strength using artificial neural network and support vector machine. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2019, 13, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, M.G.; Maged, A.; Rammal, R.; Haridy, S. LSTM-based deep learning model for alkali activated binder mix design of clay soils. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Mohammed, A.S. Surrogate Models to Predict the Long-Term Compressive Strength of Cement-Based Mortar Modified with Fly Ash. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 4187–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, W.; Aslam, F.; Joyklad, P. Compressive strength prediction of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete via advanced machine learning techniques. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.U.; Mohammed, A.S.; Faraj, R.H.; Abdalla, A.A.; Qaidi, S.M.A.; Sor, N.H.; Mohammed, A.A. Innovative modeling techniques including MEP, ANN and FQ to forecast the compressive strength of geopolymer concrete modified with nanoparticles. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 12453–12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.M.; Ma, L.; Bin Inqiad, W.; Khan, M.S.; Iqbal, I.; Emad, M.Z.; Alarifi, S.S. Interpretable machine learning approaches to assess the compressive strength of metakaolin blended sustainable cement mortar. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amlashi, A.T.; Ghanizadeh, A.R.; Firouzranjbar, S.; Moghaddam, H.M.; Navazani, M.; Isleem, H.F.; Dessouky, S.; Khishe, M. Predicting workability and mechanical properties of bentonite plastic concrete using hybrid ensemble learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Ali, M.; Najeh, T.; Gamil, Y. Computational prediction of workability and mechanical properties of bentonite plastic concrete using multi-expression programming. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kamal, S.S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, S. Compressive strength of bentonite concrete using state-of-the-art optimised XGBoost models. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2024, 40, 4868–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Gupta, N.; Goyal, S. Predicting Compressive Strength of Calcined Clay, Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Composite Using Supervised Learning Algorithm. Adv. Appl. Math. Sci. 2022, 21, 4151–4161. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, G.M.S.; Ahmad, M.; Babur, M.; Badshah, M.U.; Al-Mansob, R.A.; Gamil, Y.; Fawad, M. Boosting-based ensemble machine learning models for predicting unconfined compressive strength of geopolymer stabilized clayey soil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.U.; Mohammed, A.S.; Mohammed, A.A. Proposing several model techniques including ANN and M5P-tree to predict the compressive strength of geopolymer concretes incorporated with nano-silica. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 71232–71256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihan, M.T.; Cihan, P. Bayesian-Optimized Ensemble Models for Geopolymer Concrete Compressive Strength Prediction with Interpretability Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Ren, S.; Huang, J. Mechanical Framework for Geopolymer Gels Construction: An Optimized LSTM Technique to Predict Compressive Strength of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Gels Concrete. Gels 2024, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaswanth, K.K.; Kumar, V.S.; Revathy, J.; Murali, G.; Pavithra, C. Compressive strength prediction of ternary blended geopolymer concrete using artificial neural networks and support vector regression. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Al-Mansob, R.A.; Bin Ramli, A.B.; Ahmad, F.; Khan, B.J. Unconfined compressive strength prediction of stabilized expansive clay soil using machine learning techniques. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2023, 7, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, T.S.; Abdalla, T.A.; Rihan, M.A.M. Review of Recent Developments Regarding the Durability Performance of Eco-Friendly Geopolymer Concrete. Buildings 2023, 13, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esievo, O.P.; Awodiji, C.T.G.; Sule, S. Optimising Durability Performance of Dehydroxylated Kaolin Geopolymer Concrete Using Central Composite Design. J. Eng. Res. Rep. 2025, 27, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloul, A.; Amar, M.; Benzerzour, M.; Abriak, N.E. High strength, durability, and microstructure of geopolymer concrete with flash-calcined soils cured under ambient conditions. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 1854–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba, G.P.; Zito, S.; Tironi, A.; Rahhal, V.F.; Irassar, E.F. Calcined Clays for Sustainable Concrete Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Calcined Clays for Sustainable Concrete; RILEM Bookseries; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/8781 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Fu, R. The Strength, Permeability, and Microstructure of Cement–Bentonite Cut-Off Walls Enhanced by Polypropylene Fiber. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybek, A.; Romańska, P.; Korniejenko, K.; Krajniak, K.; Hebdowska-Krupa, M.; Łach, M. Thermal Properties of Geopolymer Concretes with Lightweight Aggregates. Materials 2025, 18, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostazid, M.I. Acid Resistance of Geopolymer Concrete–Literature Review, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Development. J. Brilliant Eng. 2024, 4, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, Y.G.; Abu-Zeid, M.M.; El-Raoof, F.A.; Soltan, A.M.; Hazem, M.M. Characterization and Potentiality of Calcined Kaolins for Metakaolin Production. Egypt. J. Chem. 2025, 68, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, T.; Guo, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, P. Effect of the SiO2/Al2O3 Molar Ratio on the Microstructure and Properties of Clay-based Geopolymers: A Comparative Study of Kaolinite-based and Halloysite-based Geopolymers. Clays Clay Miner. 2022, 70, 882–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchadjie, L.N.; Ekolu, S.O. Enhancing the reactivity of aluminosilicate materials toward geopolymer synthesis. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 4709–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Components (% wt) | Kaolinite | Illite | Bentonite | Halloysite | Palygorskite | Sepiolite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 52.32 | 65.29 | 53.91 | 48.70 | 57.50 | 62.19 |

| Al2O3 | 43.06 | 18.3 | 16.90 | 37.50 | 11.83 | 3.98 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.70 | 5.81 | 7.19 | 1.50 | 1.79 | 0.62 |

| MgO | 0.14 | 1.62 | 4.22 | 0.25 | 12.50 | 20.60 |

| CaO | 0.09 | 0.53 | 7.14 | 0.14 | 2.50 | - |

| K2O | 0.38 | 4.52 | 2.33 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 1.05 |

| Na2O | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.60 | 0.015 | 0.65 | 0.78 |

| SO3 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.12 | - | - | - |

| TiO2 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 1.12 | 0.18 | - | 0.15 |

| P2O5 | 0.11 | - | 0.51 | - | - | - |

| MnO | - | - | 0.11 | - | - | - |

| Cr2O3 | - | - | 0.01 | - | - | - |

| ZnO | - | - | 0.17 | - | - | - |

| V2O5 | - | - | 0.07 | - | - | - |

| Loss on Ignition (LOI) | 12.74 | 2.79 | 10.42 | 11.52 | 12.90 | 10.63 |

| Reference | [93,94,95,96,97] | [98,99] | [100,101,102,103,104] | [71,105,106] | [107,108] | [109,110] |

| Criteria | ASTM C618 [33] | EN 197-1 [112] | NF P18-513 [113] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Types of materials | Fly ash (Class F, C), Raw/Calcined natural pozzolan | Natural pozzolans, fly ash, silica fume, and calcined clay | Metakaolin only |

| Reactive compounds (min.) | SiO2 + Al2O3 + Fe2O3 ≥ 70% (Class F/N), ≥50% (Class C) | SiO2 ≥ 25% | SiO2 + Al2O3 ≥ 90% |

| Loss on Ignition (LOI) | ≤6.0% | Not specified directly for all additions | ≤6.0% |

| SO3 Content (max.) | ≤4.0% (Class N and F), ≤5.0% (Class C) | Typically controlled in the cement mix | ≤3% |

| Moisture Content (max.) | ≤3.0% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Fineness | ≤34% retained on 45 µm sieve | Defined by cement fineness in blended mixes | ≥90% passing 45 µm |

| Strength Activity Index | ≥75% of control samples (7 & 28 days) | Evaluated through the performance of the final cement | Must contribute positively to compressive strength |

| Soundness | ≤0.8% | Covered in EN 196-3 for cement | ≤0.5% |

| Reactivity Test | Strength activity index + chemical limits | Inferred from SiO2 content + blended cement performance | Inferred from high Al2O3 + SiO2 and strength gain |

| Exposed Temperature (°C) | Phase Transformation | Type of Transformation | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100–200 | Dehydration | Physical | During this phase, physically bound water and water from interlayer regions are lost, but the crystal structure remains intact. |

| 200–600 | Dehydroxylation | Chemical | As water is released, the hydroxyl groups (-OH) in the clay’s octahedral layers are removed. This dehydroxylation breaks the hydrogen bonds and destroys the Al–OH and Si–OH bonds. The structure partly disintegrates into a pozzolanic-reactive, disordered (amorphous) phase. |

| 600–950 | Amorphous | Structure | Hydroxyl groups (–OH) within the clay’s octahedral layers are released completely. Silica and alumina form disordered non-crystalline networks. Clay becomes highly reactive in this phase. |

| ≥1000 | Crystallisation | Chemical and structure | Atoms reorganise into thermodynamically stable crystalline forms. Sintering and the development of a liquid phase at grain boundaries cause densification. The irreversible reaction changes the material’s chemical identity. The formerly disordered or amorphous alumino-silicate loses its reactivity when it reorganises into well-ordered crystalline structures. |

| Clay | Treated/Raw | Type of Composites | % of Clay Replacement | Mechanical Strength Increased (+)/Decreased (−), Compared to Reference Sample (MPa) | Summary and Optimal Replacement | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive | Split-Tensile | Flexural | ||||||

| Kaolin | C | OPC and clay-based concrete | 10%, 20% and 30% (with OPC) | (−) 3.0% (10%) (−)11.6% (20%) (−)24.3% (30%) | - | - | Calcination at 750 °C with 10% clay replacement exhibited the least reduction in strength. | [117] |

| C | Fly ash and clay-based geopolymer mortar | 20%, 40%, 60%, 80% and 100% (with fly ash) | (+)18.5% (20%) (−) 2.3% (40%) (−) 4.9% (100%) | - | - | Optimal clay replacement was determined to be 20%. | [155] | |

| C | OPC and clay-based mortar | 15% (with OPC) | (+)10% (without ZnO) (+)15% (with ZnO) | - | - | Although ZnO slightly enhances the clay’s pozzolanic reactivity. Hence, 15% replacement was found to be optimal. | [158] | |

| C | Clay and calcium-rich additives-based GPC | 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% of QLM (with clay) | (+) 65.8% (5%) (+) 77.9% (10%) (−) 3.4% (15%) | - | (+) 412.5% (5%) (+) 700% (10%) (+) 513% (15%) | The inclusion of 10% QLM resulted in the highest improvement in both compressive and flexural strength. | [135] | |

| C & M | Kaolin-based geopolymer mortar | - | (+) 29.30% for mechanical grinding | - | - | Mechanical grinding showed the highest compressive strength. | [163] | |

| M & R | Kaolin-based geopolymer mortar | - | (+) 66.67% for mechanical grinding | - | - | Raw clay did not exhibit any pozzolanic activity. | [34] | |

| Illite | C | OPC+ calcined clay (CC) and limestone filler (LF) (mortar) | 0%, 20%, LF and 35% CC (with OPC) | (−) 7.6% (CC-28 days) (−)10.6% (LF-28 days) | - | (−) 7.8% (CC-28 days) (−) 13.5% (LF-28 days) | CC performed better than LF. Optimal replacement has not yet been achieved. In all cases, strength reduction was observed. | [120] |

| C | OPC and clay-based mortar | 30% (with OPC) | (−) 28.6% (28 days) (−) 36% (90 days) | - | - | A continuous decrease in strength indicated that the calcination temperature was insufficient to break the Si-Al bond and render the clay amorphous. Hence, optimal replacement was not achieved. | [40] | |

| C | Clay and MK-based geopolymer mortar | 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% (with MK) | (+) 58% (25%) (+) 66% (50%) (−) 25% (75%) (−) 58% (100%) | - | - | The highest strength was achieved with 50% calcined kaolin (MK) replaced with illite clay. | [183] | |

| C & M | OPC and illite-rich waste shale-based mortar | 0%, 20%, 30% and 40% (with OPC) | After 28 days of ambient curing- Calcined: (−) 35.1 (40%) Mechanical: (+) 11.3 (40%) | - | - | Mechanical activation was found to be more effective, with an optimal replacement level of 40%. | [122] | |

| Bentonite | R & C | FA, clay and PPF-based GPC | 0%, 10% FA replaced raw and calcined clay. (with FA) | Raw clay with PPF: (+) 14% (1%) Calcined clay with PPF: (+) 15% (1%) | Raw clay with PPF: (+) 32% (1%) Calcined clay with PPF: (+) 33% (1%) | Raw clay with PPF: (+) 27% (1%) Calcined clay with PPF: (+) 29% (1%) | The inclusion of 1% PPF significantly improved the mechanical performance. Hence, 1% PPF and 10% replacement were found to be optimal. | [140] |

| R | OPC and clay-based concrete | 0%, 25%, 30% and 35% (with OPC) | (+) 19.3% (30%) (−) 61.72% (35%) | (+) 22.2% (30%) (−) 6.8% (35%) | (+) 8.07% (30%) (−) 16% (35%) | A 30% replacement of raw clay with OPC resulted in the highest mechanical strength. | [185] | |

| R | OPC and clay-based self-compacting concrete | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% (with OPC) | (+) 21.5% (15%) (−) 7.14% (20%) | (+) 21.3% (15%) (−) 3.03% (20%) | - | Up to 15% replacement, strength followed an upward trend and was therefore considered optimal. | [177] | |

| R | OPC and clay-based mortar | 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10% of Na, Ca and Mg-based bentonite (with OPC) | Na-based: (+) 63.7% (10%) Ca-based: (+) 45.5% (10%) Mg-based: (+) 54.5% (10%) | - | Na-based: (+) 57.4% (10%) Ca-based: (+) 37% (10%) Mg-based: (+) 53.7% (10%) | Na-based Bentonite exhibited superior mechanical performance. 10% Na-based Bentonite was optimal. | [186] | |

| R & C | OPC and clay-based mortar | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% (with OPC) | Calcined: (+) 5.8% (20%) Raw: (−) 22% (20%) | - | Calcined: (+) 4.98% (20%) Raw: (−) 6.3% (20%) | Mechanical strength was significantly enhanced by calcination, and 20% replacement was optimal. | [142] | |

| Halloysite | C | FA, GGBFS and clay-based geopolymer mortar | 0%, 1%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8% (with FA and GGBFS) | (+) 8.3% (1%) (+) 35.8% (2%) (+) 19.3% (4%) (+) 2.8% (6%) (+) 10% (8%) | - | (−) 19.2% (1%) (+) 11.8% (2%) (−) 22.1% (4%) (−) 41.2% (6%) (−) 39% (8%) | The highest increase in mechanical strength was observed with a 2% inclusion of halloysite. | [147] |

| R | OPC and clay-based concrete | 0%, 0.5% (with OPC) | (+) 0.7% | - | - | Raw Halloysite positively impacted the mechanical performance. For this study, 0.5% was found to be optimal. | [181] | |

| C | Clay-based geopolymer paste) | - | (+) 116.6% at 750 °C | - | - | The highest strength was observed at 750 °C. | [145] | |

| Palygorskite | C | OPC and clay-based mortar | 0% and 20% (with OPC) | (−) 2.5% | - | - | Compressive strength was slightly reduced. Hence, optimal replacement was not achieved. | [79] |

| C | OPC and clay (Mg and Al-rich)-based mortar | 0% and 20% (with OPC) | (+) 0.96% (Mg-rich clay) (−) 21.14% (Al-rich clay) | - | - | Mg-rich clay exhibited higher strength than Al-rich clay and was considered optimal. | [150] | |

| Sepiolite | R | MK, Fly ash and clay-based geopolymer paste | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% (with MK and fly ash) | (+) 8.5% (15%) (+) 5.1% (20%) | - | (+) 15.5% (15%) (+) 5.6% (20%) | The addition of sepiolite to the geopolymer matrix significantly enhanced the mechanical strength. 20% replacement was found to be optimal. | [187] |

| C | OPC and clay-based mortar | 0% and 20% (with OPC) | (−) 0.67% | - | - | A slight reduction in strength was observed. Hence, optimal replacement was not achieved. | [152] | |

| Acid treated HCl & HAc | OPC and clay-based cement paste | 0% and 10% (with OPC) | For HCl: (−) 1.9% (1M) For HAc: (−) 3.9% (1M) | - | - | A strong acid assisted in breaking the Si-Al bond, making the clay more pozzolanic compared to a weak acid. | [87] | |

| Clay Type | Ideal Treatment Method | Performance in Concrete |

|---|---|---|

| Kaolin | Calcination and mechanochemical | High pozzolanic reactivity; improves compressive strength and durability |

| Illite | Mechanochemical is preferred over calcination. | Low reactivity with calcination; mechanochemical activation significantly improves performance. |

| Bentonite | Calcination and mechanochemical | Enhances flexural and tensile strength; calcined Bentonite outperforms raw; optimal at 15–30% replacement. |

| Palygorskite | Calcination (Limited research shows mechanochemical activation also enhances pozzolanic reactivity.) | Improves durability and resistance to environmental attack; less studied than Kaolin/Bentonite. |

| Halloysite | Calcination | Enhances early-age strength and reduces shrinkage; improves shape stability. |

| Sepiolite | Calcination (Limited research shows mechanochemical activation also enhances pozzolanic reactivity.) | Improves workability and durability; used in lightweight and specialty concretes. |