Abstract

The adaptive reuse of cultural heritage assets is often problematic. What emerges is the urgency of a thoughtful negotiation between built forms and emerging needs and requests. In this view, a fruitful trajectory of development arises in commoning heritage by means of adaptive reuse. Hence, the purpose of this article is to investigate how community-led adaptive heritage re-use practices contribute to social innovation in terms of new successful model of urban governance, by providing a specific focus on innovative aspects that emerge in both heritage and planning sectors. Therefore, it also aims to improve the knowledge in the innovative power of heritage when conceptualized as performative practice. To this end, the paper presents the adaptation process of a former church complex located in Naples, today Scugnizzo Liberato, one of the bottom-up initiatives recognized by the Municipality of Naples as part of the urban commons network of the city. The research results are based on desk research, a literature review, and interviews with experts and activists, conducted as part of the OpenHeritage project (Horizon 2020). Initial evidence shows that profound citizen involvement throughout the whole heritage-making process might generate innovative perspectives in urban governance as well as conservation planning practice.

1. Introduction

The importance of the re-conceptualization of cultural heritage as a common good is solidly affirmed in the European quality principles for EU-funded interventions with potential impact upon cultural heritage, issued by ICOMOS in 2020 []. According to the document, this is a necessary precondition for advancing quality principles in EU-funded heritage conservation and management. As recalled in the Davos Declaration [], the common good is also the main objective of transformation processes based on culture. By focusing on quality, what these policy documents share is the orientation towards a humanization of the built environment, often advocating for a different kind of ownership as much as the activation of new social constructions []. In this context, the role of communities in cultural heritage is increasingly recognized and fostered by the European commission. The Faro Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society ignites a revolution in the heritage field by placing on people the right and duty to actively recognize, participate in and benefit from heritage assets, opening up new patterns of social change and resilience []. Thereby, the broadening in nature and categories of what resources merit conservation has induced innovations (and complexification) in heritage planning also expanding the ways in which heritage is reckoned, managed and cared for [].

Heritage is thus increasingly conceived (and valued) as a process. Beyond heritage objects and its representational values, van Knippenberg et al. argue [] that the complexity of a co-evolutionary heritage approach is “more about identity, practices and immaterial aspects” (p. 12), shedding light on the interrelatedness and relatedness of urban components such as material/immaterial assets, local community and spatial development. In the redefinition of the heritage concept, the centrality of performative practices thus resonates in larger territorial aspects, making heritage regeneration work for or against displacement, gentrification and inequalities. Hence, Smith draws on the policy of recognition to take a step forward towards the rejection of heritage meanings and discourse dominated by experts’ assumptions and narratives, known as the Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD) []. Assuming that heritage “is not simply a ‘thing, place or site’, but … [an] affective process and activity” [] (p. 48) of knowledge and meaning-making, the implication of heritage in the policy of recognition becomes self-evident due to the process of assessment, negotiation and legitimation of the identities it underpins. From this viewpoint, heritage is a resource implicated in the struggles over recogni tion, redistribution and restorative justice.

It needs to be noted that the emotional reconnection between people and (historic) places, which generally drives grassroots movements against the privatization of the commons, plays a pivotal role [] by shining light on the ways heritage affectivities can encompass political and ecological concerns [,]. In other words, valuing that aspects of proximity, largely recalled and reclaimed throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, are not only physical or local but are also interlinked with people’s more intimate subjectivity. Inscribed within the framework of the commons, cultural heritage is thus reclaimed as a shared resource, aligning with a more democratic and critical conception of current heritage []. Although the correspondence between the performative nature of heritage and commons principles is straightforward, the connection of the two fields has received little attention. Whilst great emphasis has been given to legal and real estate experiments based on the commons [], less is said about their innovative contribution in the realization of heritage, as well as its integration with the planning sector.

In this context, adaptive reuse has gained a considerable political momentum due to a more comprehensive capacity to tackle and integrate economic and social aspects of heritage. Dealing with multiple temporalities, adaptive approaches allow for more collaborative, neighborly stances, favoring the generation of relational values [] but also of “opportunity” spaces for catalytic change []. Thereby, it contributes to create the conditions for social innovation, an under-researched area of studies in the heritage sector that, conversely, is more often understood as opposed to innovation and creativity [].

From an ecological point of view, instead, heritage practices of reuse meet needs of waste reduction (responsible consumption and production, SDG 12), while their alignment to circular paradigms gives way to human-centered perspectives based on symbiotic, autopoietic and generative capacities [,]. According to Girard, these characteristics lie in the co-evolutions of both people and heritage through a continuous and non-linear process of adaptation-transformation, inducing mostly innovations in terms of heritage management []. Being adaptive, thus, not only denotes flexibility in terms of spaces, behaviors and uses, but it also embraces a process of value creation and enhancement that starts by acting-from-within people and places. The unfolding of this process thus entails a reflexive rationality for cultural heritage management that demands a shift in terms of values and aesthetics. For the sake of community involvement, a vernacular approach is increasingly recognized as possessing a heritage value []. From this viewpoint, the imperfect, decaying narratives of spontaneous interventions thus contribute to open conservation towards processes of amnesia and loss, deemed essential for dealing with contemporary realities [,].

Perhaps not surprisingly, building regulations and codes are recognized as being among the main barriers to creating heritage adaptive re-use [,]. Despite the degree of national secularization, the reuse project of European religious assets such as churches shows extremes and contradictions which lie under the ideal of “heritage as a resource” when it comes to dealing with strong values, identities and powers [,,]. For the spatial, social and economic function of these assets to be re-evocated, re-signified or re-activated, an open and multidisciplinary approach is therefore required. Undoubtedly, this is a precondition to deal not only with conservation of heritage objects but also with those adjustments that will occur overt time [,]. On the other hand, it is acknowledged that bureaucratic and commercial dynamics play an increasingly important role in the enclosure of common spaces (and thus heritage spaces conceptualized within this framework), reducing, discouraging or disregarding spontaneous forms of participation []. An attitude that all too often tends to be overshadowed or absorbed by capitalism, making informal lifestyle works for neoliberal purposes and eventually lining up with the production of new inequalities [].

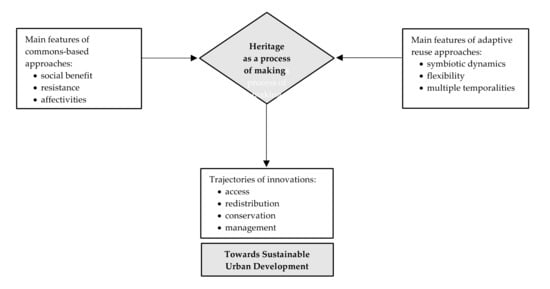

Although community involvement can easily become tokenistic, I argue that the implementation of common-oriented practices on heritage assets allow dominant heritage paradigms to be overcome, innovating the sector and reinforcing its integration in sustainable development. Drawing on commons and heritage studies and intersecting them with the reuse process, these argumentations thus define a conceptual framework that bridges commons and heritage fields in accordance with specific characteristics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Synthetic view of the main characteristics extracted from the literature review.

To this end, the article presents a specific focus on the Italian context. Advancing a mounting number of experimentations grouped under the umbrella of the commons, it indeed seems to offer a particularly rich scenario. In the last decades, the rapidly growing number of community-led initiatives along with the growing abandonment of urban (public and private) stock have gained interest both from scholars and public institutions, while also fostering a copious body of research [,]. Whilst over past centuries, asset disposal often prevailed (and in many cases still does), in recent years, public administrations have started to invert this trend by experimenting with new enhancement strategies of their assets based on civic engagement. Public properties are entrusted to parties capable of social innovation [,]. In doing so, it can be affirmed that the re-conceptualization of urban commons has provided a theoretical and operational framework [] within which administrative innovations have emerged, mainly at a local but also at a national level (see for instance art. 24 and 26 L. 164/2014 Unblock Italy Decree). When it comes to cultural heritage, though, collaborative reuse processes are particularly problematic and the link between this sector and innovation tends to be overshadowed.

Considering the Italian scenario, commoning heritage by means of adaptive reuse has offered the opportunity to test more open trajectories of development by inducing institutional innovations in both heritage management and planning. However, while civic uses have received much recognition from the legal-administrative viewpoint, less is said regarding their innovative contribution in heritage and planning as well as in the integration of these two fields. To shed light on these issues, the research questions that guide this study thus regards motivations, tools, methods and trajectories of development of one of the commons-based initiatives acknowledged by the Municipality of Naples as part of the urban commons network of the city, today known as Scugnizzo Liberato (SL). By showing an innovative approach to cultural heritage as a vector for both urban regeneration and social innovation, the case study is part of the OpenHeritage research project (Horizon 2020).

The purpose of this article is primarily to illustrate how commoning practices contribute to social innovation in terms of new successful modes and regulations of city governance and planning and how this might impact on (cultural) heritage management. This thus serves to elucidate how commoning experiences contribute to reorienting the Italian conservation practice towards a more relational notion of cultural heritage. On the other hand, the article aims to improve the knowledge in the innovative power of heritage when conceptualized as performative process. The paper thus highlights potential ways of operationalizing power distribution by means of co-management; the materiality this approach implicates when it comes to integrate social benefit and heritage conservation; and the areas of possible upscaling of innovative local processes in both heritage and planning systems. Therefore, the paper contributes to the heritage and planning studies that envision a more integrated and participated approach to the urban legacy.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the research methodology adopted to address the case study and critically analyses it within a larger territorial context (local and national). To fully understand the relevance of the SL, Section 3 frames it within the Neapolitan context from which it is indivisible. There follows (Section 4) the investigation of those emerging innovations that are deemed relevant for heritage transformations, not only at a city scale but also at a national one. Finally, the discussion (Section 5) concludes by arguing how commons practices serve to advance innovations in the field of heritage. Insisting on emerging trajectories within the framework of the commons, evidence shows that a profound citizen involvement throughout the whole heritage-making process might inform further generative policy as well as renovating the conservation-planning practice.

2. Materials and Methods

The study presented in this paper stems from a project entitled OpenHeritage—Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re-use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment—funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program []. The openness at the core of the project evokes the principles expressed in the aforementioned Faro Convention (2005), reinterpreting cultural heritage in the light of the complex, co-evolutionary [] interrelations occurring between objects and communities, people and times. It strives for a governance model based on a plurality of actors, going beyond a private/public dichotomy [] and thus creating the conditions for more inclusive and just processes of heritage reuse.

The SL (Naples, Italy) is 1 of the 16 Observatory Cases (OCs), i.e., ongoing community-led adaptive heritage reuse practices present throughout Europe, which provides the micro level of analysis of the project. Overall, the study was conducted along the three OpenHeritage pillars, i.e., community/stakeholder, resource and regional integration, with the aim of identifying sustainable and innovative ways of heritage governance, transformation and management, therefore gaining insights about how to expand participation and social benefit in these fields.

Methodologically, the research was based on the case study analysis of the SL to understand how adaptive heritage reuse works in practice throughout the entire cycle of transformation (from the launch of the initiative, to the decision-making stage, up to the construction phase) and management of the heritage site. This serves to understand the connections between the community, the place and the Municipal institution, as well as their present and future models of development in the three aforementioned domains. To this end, the analysis combined different sources of data. At first, it reviewed and drew on a large number of documents, including policy, administrative (e.g., resolutions), academic and communicative material (e.g., leaflets, website, social media) with the aim of reconstructing the administrative innovations and the research/cultural areas which had the most impacted. Secondly, 18 in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with activists (no. 8, group A), scholars (no. 3, group S), spokespersons (no. 3, group SP) and public officers (no. 4, group PO). The majority of interviews were held between 2018 and 2019, while two of them were conducted in July 2021. These latter serve in understanding how the COVID-19 outbreak impacted on the initiatives and how the community reacted to this stressor. Alongside gaining a profound understanding of the initiative itself, the ethnographic work allowed capturing the open-end nature of the process, likewise its social and reflexive dimension [], outlining the impact perceived in the neighborhood/city/region on a qualitative basis. Moreover, with the purpose of providing critical results in the field of urban planning and cultural heritage, this contribution combines the data collected at a local level with insights gained in a study at a national level. In this case, interviews with practitioners and public officers (no. 8, group PR) mainly allow to identify obstacles and potential supportive measures to adaptive reuse projects grounded in a social mission. Contrasting the two tiers helps to illuminate the types of innovations that are deemed relevant in the Italian context and the way commons-related practices act to renovate the system. The results are then presented with a specific attention to the innovative aspects of the case in relation to contextual characteristics. This latter study is part of the same project and was aimed at providing a complex overview of how community-led adaptive reuse (or not) works in European national contexts. Major results were published in the project website in December 2019 []. However, in attempting to deploy an inter-scalar discourse, I will also refer to unpublished materials and interviews collected during the research activity for the Italian case.

Finally, interviews to the SL community were accompanied with several site visits during which we produced a photographic report and a video, mainly devoted to a communicative purpose []. The SL detailed report was part of Work Package 2 Observatory Cases and was published in the OpenHeritage website in November 2019 [].

3. The Scugnizzo Liberato and Naples Commons

The SL is located in one of the historic districts of Naples, the Avvocata district (part of the II Municipality of Naples), and is based in the former convent of San Francesco delle Cappuccinelle, a public property, recently listed as an Italian cultural asset. The central area of Naples has been part of the list of UNESCO assets since 1995, and it is included within the UNESCO Big Project [Grande Progetto UNESCO], namely, a renovation plan that embraces the entire area (about 720 hectares).

However, the Avvocata district is characterized by economic and social marginalization, and it has been subject to a spontaneous mix of urbanization due to different groups inhabiting the area (Figure 2 and Figure 3). It has one of the highest unemployment rates in Naples [] and its population is composed of a significant percentage of young people, particularly students (ibid).

Figure 2.

Top view of the San Francesco delle Cappuccinelle complex.

Figure 3.

Street view towards Salita Pontecorvo where the ex-convent is located.

Founded in 1585, the convent went through several transformations, adapting and thus changing forms and functions in relation to contextual circumstances. However, what marked its contemporary memory the most was its 1809 conversion into a juvenile detention center, the Filangieri Institute. Indeed, this use was maintained over the following century when, on 23 November 1980, it was severely damaged by the Irpinia earthquake, one of the most destructive seismic event of Naples that struck the entire region of central Campania and Basilicata.

Once abandoned, several attempts at adaptation and reuse occurred, ultimately failing to restore the enormous complex of 10,000 sqm (Figure 4). In this context though, it is worth recalling the partial renewal of the convent supported by Eduardo De Filippo, senator of the Italian Republic in 1985 and one of the most important figures of the Italian theatre of the past century. “Eduardo’s dream”, as it was known, was to transform the ex-detention centre into a social and cultural space based on workshop and educational activities. Although the project remained incomplete, its legacy has been collected and reinterpreted by the current project.

Figure 4.

The convent and its courtyard. Credits: Federica Fava.

Activists of the Scacco Matto group entered the complex in September 2015, after about 15 years of abandonment. Even though a large-scale collaboration also started out of necessity, from the beginning, the intention of the group was to encourage the inhabitants’ involvement in the space’s management, turning the old convent into a mutual aid laboratory [Laboratorio di mutuo aiuto] where alternative forms of welfare are produced and delivered by the community itself. Therefore, the SL group has steadily grown to form a network of collectives that include various cultural associations, NGOs, individuals (e.g., artisans), students, minority groups (e.g., Sri Lankan and Cape Verdean communities), etc., giving back to the district its larger (indoor/outdoor) public space. This tension is what led the SL to be recognized (2016) as one of the common assets of the City of Naples.

As is widely documented, since 2011, Naples has been at the forefront of the mobilization of the commons, quickly attracting international appreciation; the City of Naples was the leading partner of Civic eState—URBACT III project, 1 of the 25 European transfer networks launched by URBACT in 2018. The process has been based on a series of resolutions (Table 1) that reinterpreted and updated the ancient device of “civic use” [usi civici], originally related to old rights of the collective enjoyment of earthly goods []. This ultimately updated and expanded the former right, from the original assets of pasture, hunting or firewood to abandoned real estates and urban contexts, giving back to the people new lands of self-appropriation and self-determination. Inspired by constitutional principles (i.e., art. 41, 42, 43 of the Italian Constitution), the newly defined framework of the commons has served the legitimation of those informal-illegal-emerging communities acting in the general interest by occupying and reusing public assets that were otherwise abandoned. The intent was to surpass the classic concession agreement model by recognizing and recording social value as being part of the economic value of heritage assets []. The dualism of the public–private regime was thus overcome, and a way of prioritizing social values and social utility over private interests was illuminated. Following the ex-Asilo Filangieri’s experience, i.e., the first space to be formally recognized by the administration as a common good, the SL and six other places re-activated by squatting groups therefore became part of an institutional process of legitimation due to the relational, social and civic capital generated by their active participation in urban life.

Table 1.

List of the resolutions issued by the Naples City Council and their main topics.

The updating of this ancient mechanism has generated a city-wide innovation process, fostering a giant and international body of studies []. However, while this evidence has been widely discussed from the juridical, social or cultural viewpoint, it is useful to consider how it might contribute to informing and innovating the heritage discourse.

4. Results

As result of the aforementioned process, the commons paradigms currently inform the city planning of Naples. In the 2020 Orientation document, issued by the City of Naples [], the guidelines for updating the city plan are designed on commons-related principles. Primarily, the aspiration of an environment that is more favorable towards heritage reuse culminates in the inclusion of different temporalities (i.e., time-based, interim) within the future urban planning tool (resolution no. 458/2017), operationalizing the idea of “urbanism as a collective project rather than as a program” [] (p. 5). Whilst in the historic city the socialization of urban resources forces the definition of a more nuanced nexus between building typologies and (multiplication of) uses, the civic use seems to have a complex impact on the way collective facilities (have and) will be produced in the implementation of the city plan []. Resolution no. 458/2017 innovates so-called urban standards [standard urbanistici] by introducing “civic urban community” and regulating temporary uses for the social enhancement of public properties []. In doing so, it creates the conditions for an extensive experimental approach [] that embraces the whole cityscape, and thus nurtures its (re)conceptualization as a resource for social innovation. The universality of the commons approach relies on the idea of a constitutional-based urbanism. Particularly for cultural heritage, art. 9 of the Constitution makes its very mission explicit, namely, being a means to embodying critical cultures [] and helping human abilities to flourish.

In this respect, it needs to be pinpointed that in Italy temporary uses are still in “a limbo between legality and illegality, lacking a specific juridical framework” within the planning system [] (p. 160). Although the growing interest in urban regeneration has steered the initial updating of the Italian building activity norms on the matter (see, for instance, the 2020 updated version of the D.P.R. 6 June 2001, n. 380 Testo Unico dell’edilizia, art. 3, 6, 23 quarter), practitioners agree about the fact that the lack of a clear framework for temporary uses, on one side, and an overly strict regulatory environment, on the other, define the main obstacles to a socially oriented heritage adaptation. The need to inhabit the selected places and thus to develop ideas “from within” is a recurrent theme:

“The most critical factors affecting the success of community-led adaptive reuse projects are time and procedures. […] Administrative delays often tend to reduce the energy needed to develop such projects. […] Without hygienic permission, for example, you cannot cook or even dance. However, there are many possibilities for secure activities to be conducted outside the norms.”

“The regeneration of a heritage site is always a special act. Therefore, we never deal with a place without inhabiting it. You cannot think of addressing the complexity without living that condition. […] The places where we work are not legally habitable, but this is just a formality because, in practice, they are secured. The sites we tackled were often burdened with critical economic and bureaucratic administrative issues. It is by overcoming these constraints that we can work.”

(interviews group PR)

Although the ability of the commons to effectively resist neo-liberal approaches needs to be continuously confirmed [], the recognition of Neapolitan squatting experiences as “emerging commons” defines a way to make room for a trial and error method, postponing some of the procedural aspects related to (cultural) heritage in a second moment. The commons framework thus assures the mediation of the local authority and a more flexible regime of security:

“The municipality functions as guarantor of the commons initiatives and this can help to solve problems that may arise with a Soprintendenze (the regional branches of the State for heritage conservation). When it is time to advance more consistent restoration work, we support and collect proposals by the local communities and discussed them with Soprintendenze, following the ordinary procedural path but also facilitating this relationship.”

(interview group PO)

Within the commons network, the dialogue between citizens and public administration is renewed on a regular basis since public officers participate in the management assemblies conducted by the communities to run each project. Although “being on site” is generally deemed a pivotal governmental and political condition to steer a more responsive institutional ecosystem (OpenHeritage internal dialogue for the elaboration of Transferability Matrix, July 2021), in the Italian context, this assumes a peculiar role. Indeed, in the last decade, the growing impact of austerity measures in the cultural heritage sector has led to a significant reduction of the Soprintendenze’s powers. On the other hand, a shift toward actions mainly focused on national strategic assets (e.g., Grandi Progetti Beni culturali, D.L. no. 83/2014) and tourism-oriented approaches have conveyed a progressive fragmentation of its heritage (reuse) policy, often detached from desires emerging from below. The lens of the commons also unveils a strategy of distribution which allows resource heritage assets on the basis of locally shared interest:

“Once a common good is acknowledged it becomes a priority, meaning that we start looking for resources to keep supporting its development. It does not mean that other projects are less important. But it is obvious that having a community that uses a certain site and wants to follow up with its project represents a significant determinant for the asset conservation itself.”

“The redevelopment program for the former Cappuccinelle convent provides municipal investment starting from its use. To some extent, the innovation lies in the ability to link potential funding, so much so that the complex was assigned with a restoration plan of 7,500,000 euros (2014/2020 EU Cohesion policy—Culture and Tourism plan).”

(interviews group PO)

Beyond heritage, what motivated the collective actions is a multiplicity of objectives. By means of the commons, heritage matters are thus addressed transversally, encouraging a cross-sectorial discourse:

“The concept of the commons […] does not solely regard the “freed spaces”, but it concerns all administrative policy […]. We interface with the youth department for activities and policies that regard the youngsters. We have also worked with the tourism department, since the city of Naples is increasingly hit by tourist flows. Obviously, we interface with the heritage department because the initiatives use municipal properties that must serve the public arena.”

(interviews group PO)

However, in the SL case, activists underlined a feeling of social redemption which pass through the need of a more narrowly relation with the district, its local youth and the (lack of) collective spaces:

“The goal was to give this space back to the citizens after decades of neglect—especially to the inhabitants of this neighborhood, who do not have a square or a meeting place and then provide a space where a series of mutualistic activities can happen. Moreover, this ex-convent is huge and has a very significant history for the neighborhood and today it has become a point of reference for young people, especially in terms of music.”

“The occupation was an attempt to rediscover a collective horizon that many people had to abandon because of work or other necessities. It was a matter of giving people trust, give them space.”

“It was Eduardo De Filippo’s dream of turning the convent into a daily multi-functional center where different kinds of courses and craft labs can be hosted. Therefore, the goal was to create a shared knowledge and we have stuck with this endeavor [].”

(interviews group A)

The preservation of historical and cultural value of the ex-Cappuccinelle convent were not the main objectives of the initiative. However, the opening of the asset towards forms of self-organization stimulated the rediscovery and appreciation of heritage values and the production of new cultural-social ones.

“The community is becoming conscious of the architectural and historical value of the Cappuccinelle. Thus, the program of activities needs to agree and proceed parallel to a restoration project, preserving the complex in its integrity. In order to attain this aim, we are cooperating with the public authority.”

“Originally, people were afraid of this place. By using it, though, the relationship with the convent has changed also thanks to new cultural productions among which many songs that significantly have help to chase away the ghosts that burden over the complex.”

(interviews group A)

Along with the presence on site, this progressive expansion in terms of meanings but also actors (from the squatting group, to the neighborhood inhabitants and, more recently, local vendors) is encouraged through three components that significantly characterize the SL initiative and partially the commons network itself: the free and (mandatory) collective usage of the convent premises, its self-management process and self-construction.

To the formal recognition of the community indeed corresponds the opening of the decision-making process to its members. The governance and management of the asset follow the model firstly experimented in the ex-Asilo Filangeri and adopted by all the commons initiatives. In accordance with the local authority, this community’s responsibility develops in weekly management assembly [assemblea di gestione], which is the only “agency” holding the power to enforce binding decisions for the community. It brings together the whole community, including public servants, and is organized around changeable thematic assemblies [tavoli tematici] (Figure 5) dedicated to specific topics and their respective members: internal and external communication, participative architecture and self-recovery, cultural programming, building community, common goods and alternative economies. The management assembly serves to arrange the routine management of the complex (programs, activities, etc.), its recovery work as well as communication and logistics.

Figure 5.

An open-air assembly. Credits: Scugnizzo Liberato.

The process of self-determination has been also cultivated through the SL’s Declaration of the Urban and Civic and Collective Use (for SL, approved by resolution no. 424/2021), presented by each initiative to the Municipality to sets the rules proposed by the community for the self-governance of the asset. In general, self-recovery and collective care of the space represent the cornerstones of civic use practices, the aim of which is to strengthen the capacities of the most fragile individuals in the city, in part by means of a more corporal approach to heritage making (Figure 6). For the SL, activists strongly agree on the value assumed by self-recovery activities both in term of space adaptation and community building []. DIY practices thus assume a pivotal role in the project as a way to combine commons ethics and open aesthetics. While at the beginning this has served the immediate and low-cost access to the convent, the inclusion of self-recovery practices in the SL’s Declaration is a “proactive” statement, ultimately aimed at overcoming time-consuming procedures, in Italy required also for minimal interventions in listed assets []:

“The building started to be restored, especially in the first period, thanks to people’s efforts. When we arrived to the convent it was traumatic: both courts were completely covered with grass and trees that were rooted up to the internal rooms of the complex. In addition, the condition of the church clearly showed that many assets were plundered.”

“The complex is a cultural asset which means constraints are pending it over. We acknowledge and protect its cultural value but in the Scugnizzo Declaration (art. 16) we have also tried to assure the community with a minimum level of autonomy over the maintenance and the restoration of the asset. […] In such a decaying and large complex as the SL, it should be the community that indicates the interventions and, when possible, intervening autonomously.”

(interviews group A)

Figure 6.

Collective work of cleaning. Credits: Scugnizzo Liberato.

The commons model has thus launched the implementation of guidelines to define a future DIY regulation for the City of Naples [], opening up an additional field of innovation within the heritage-building sector. At the national level, indeed, the lack of rules to frame citizens’ actions in terms of self-construction is perceived as one of the main barriers to bottom-up adaptive reuse [].

5. Discussion

This paper began following recent European developments in matters of heritage and argues concerning the growing centrality assumed by community in the process of heritage recognition and care. Analyzing the Scugnizzo Liberato, and more generally, the process conducted in Naples under the umbrella of the commons, this article focuses on the innovate aspects of the presented actions. This shifts the attention towards innovations generated along the trajectory of the commons, understanding motivations, modalities and tools that might be upscaled in the heritage sector.

The analysis stresses the attention on the processes of self-organization that happen in an abandoned heritage asset that set the scene for new spatial and human organization. Interpreting the city assets as social infrastructures of public value and social impact [], the socialization of heritage through commons enforces the use value of assets and revolutionizes prerequisites of accessibility. Although the physical transformation/conservation of the cultural object might in some cases be endangered through the implementation of immediate uses and actions, mainly led by non-experts, the SL seems to contribute to the high-quality principle set by the ICOMOS [] for interventions in cultural heritage in multiple ways. Alongside prioritizing the “public benefit” in terms of both citizenry and access to the cultural good, the convent occupation supports a process of knowledge building, one of the conditions to develop a conscious conservation project. Moreover, the focus on the process (e.g., good governance in the ICOMOS’s words) and the inclusion of the project within the city strategy introduce long-term elements of sustainability. From this viewpoint, commoning heritage expanded the notion of urban standard showing a way to develop a more complex (cultural) approach to the quality of living, one that meets not only functional-spatial requirements but also social, psychological and resilience aspects.

Moreover, the analysis shows that power distribution is made possible through the recognition of the social and cultural value of performative heritage practices based on commons principles. The new organization in terms of self-management/organization and regulation starts with the opening of the process to a large arena of actors that works in dialogue with the public administration to redefine a shared set of values over preexisting ones. These evidences are particularly relevant in the Italian heritage system. Although the Italian Heritage Code [dl no. 42/2004] focuses on cultural heritage safeguarding [tutela] as a way to guarantee its conservation and public fruition [fruizione pubblica], the continuing prevalence of issues of materiality over real needs overshadows the very mission of preservation, i.e., the use of heritage []. In this context, the SL initiative demonstrates that the commons governance model has the capacity to make conservation instrumental for public fruition and, in doing so, defining a way to heal the fracture between conservation and enhancement which characterizes the national system [,].

To treat heritage as a common has material consequences motivated not only by social and economic purposes but also by uncertainties regarding present and future priorities. For heritage to be supportive of social change, ephemeral, informal or no interventions become tools of an adaptation strategy that proves to be relevant in facing and rewriting dark assets, territories and futures. The symbiotic relationship established between human and urban bodies through self-construction and organization functions as a detoxing agent against structural (managerial) dysfunctions [], opening up the way to new areas of innovation in both heritage and planning. On the other hand, it serves as a decolonizing agent that creates a rupture, not only with racialized environments against minority groups (whether migrant, foreign or poor people) [] but also with state-led violence and the domination of authorized heritage actors through in situ rationalities of mutual care.

To conclude, the reformulation of heritage within the framework of the commons contributes to challenge the prevalent heritage discourse through the transformative potential of collective desires and endeavor. In fact, despite interests in matters of heritage being initially surpassed by other priorities, the study shows practical modes to discover and (re)create uses and meanings that inform new heritage values by means of adaptive strategies of reuse. Beyond the specificity of the “civic use” model, however, it is important to underline the centrality of the adaptive approach to heritage reuse within larger process of urban transformation. It indeed requires participatory methods and tools that can generate further changes in the management and transformation of the build environment that do not end within commons-related frameworks.

In the face of the climate threats increasingly challenging urban-heritage contexts, further studies on this matter would be undoubtedly needed. What are, for instance, additional reasons, sectors and modalities to be taken into account in sustainable urban development grounded on commons-oriented practices? What is the role of commons practices of heritage reuse in building new memories and affective bonds with the territory, and how might they be instrumental to design trajectories of resilient building by means of heritage?

Funding

This document has been prepared in the framework of the European project OpenHeritage—Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re-use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 776766.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The interview format adopted for the study was coordinated with OpenHeritage partners, following the approach described in the Task 2.1 Anthropological analysis of individual Observatory Cases. Ethical review and approval by Roma Tre University were waived for this study since they were not required by the University regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

All the subjects involved in the study were verbally informed of the purpose and objectives of the research and of their contribution in the OpenHeritage Deliverable 2.2. Observatory Cases Report. A written consent was obtained from the subjects quoted in this paper and from interviewees involved in the video published in OpenHeritage website.

Data Availability Statement

Presented in the OpenHeritage database at: https://db.openheritage.eu/#/sys/oh/oc/Scugnizzo%20Liberato. The full description of the Scugnizzo Liberato project is available in the section “Practices” of the OpenHeritage website at: https://openheritage.eu/practices/ (accessed on 9 December 2021).

Acknowledgments

As part of the OpenHeritage project, some of the reflections in this paper were initially presented in the Observatory Cases Report (see deliverable 2.2 in the project website) and in a national conference of urbanism titled DOWNSCALING, RIGHTSIZING. Contrazione demografica e Riorganizzazione spaziale (SIU 2021). The work evolved thanks to collaborations and dialogues held within the Department of Architecture of Roma Tre University and in particular with the group coordinated by Giovanni Caudo, who I thank immensely for his careful review and patience. A special acknowledgment goes to Fabrizia Cannella who worked with me in the research activity and in writing previous publications. The three of us owe so much to the many interviewees who collaborated with us and to OpenHeritage colleagues for their enduring support. A final thanks is for the reviewers which comments greatly helped this work to be improved and finalized.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ICOMOS. European Quality Principles for EU-Funded Interventions with Potential Impact upon Cultural Heritage; ICOMOS International Secretariat: 2020. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2436/ (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Swiss Confederation. Davos Declaration. Towards a High-Quality Baukultur for Europe; Davos 2018. Available online: https://davosdeclaration2018.ch/davos-declaration-2018/ (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Urban Age Debates. Humanising the City: Can the Design of Urban Space Promote Cohesion and Healthier Lifestyles? Available online: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCGzHnRkUHkllEbMITAh8ugg (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Fabbricatti, K.; Boissenin, L.; Citoni, M. Heritage Community Resilience: Towards new approaches for urban resilience and sustainability. City Territ. Arch. 2020, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesco, B. Reshaping Urban Conservation; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–20. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-8887-2_1 (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Van Knippenberg, K.; Boonstra, B.; Boelens, L. Communities, Heritage and Planning: Towards a Co-Evolutionary Heritage Approach. Plan. Theory Pr. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. The Uses of Heritage. Routledge. 2006. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Uses-of-Heritage/Smith/p/book/9780415318310 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Smith, L. Emotional Heritage: Visitor Engagement at Museums and Heritage Sites; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315713274/emotional-heritage-laurajane-smith (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Botta, M. Heritage and City Commons. In The City as Commons: A Policy Reader; Ramos, J.M., Ed.; Commons Transition Coalition: Melburne, Australia, 2016; pp. 26–31. Available online: https://commonslab.be/publicaties/2018/7/14/the-city-as-commons-a-policy-reader (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Gonzalez, P.A. From a Given to a Construct. Cult. Stud. 2014, 28, 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, R. On Heritage Ontologies: Rethinking the Material Worlds of Heritage. Anthr. Q. 2018, 91, 1365–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Whose heritage? Un-settling ‘the heritage’, re-imagining the post-nation. In The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of Race; Littler, J., Naidoo, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 21–31. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uniroma3-ebooks/detail.action?docID=199418 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. Design principles and practices for the urban commons. In Routledge Handbook of the Study of the Commons; Hudson, B., Rosenbloom, J., Cole, D.G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Elefante, A.; Rocca, L. A Creative Living Lab for the Adaptive Reuse of the Morticelli Church: The SSMOLL Project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauws, W.; De Roo, G. Adaptive planning: Generating conditions for urban adaptability. Lessons from Dutch organic development strategies. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2016, 43, 1052–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, C.J. Social Innovations in Museum and Heritage Management. New Approach Cult. Herit. 2021, 2021, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Girard, L.F.; Ost, C.; Saleh, R. Evaluation Criteria for A Circular Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Circ. Models Syst. Adapt. Reuse Cult. Herit. Landsc. 2017, 17, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, L.F. The Circular Economy in Transforming a Died Heritage Site into a Living Ecosystem, to Be Managed as a Complex Adaptive Organism; Aestimum Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/4921079#page=38 (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Plevoets, B.; Cleempoel, K.V. Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage: Concepts and Cases of an Emerging Discipline; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Desilvey, C. Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Holtorf, C. Embracing change: How cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage. World Archaeol. 2018, 50, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E.D. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. In Structural Survey; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Perth, Australia, 2011; Volume 29, pp. 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Conejos, S.; Langston, C.; Chan, E.H.W.; Chew, M.Y.L. Governance of heritage buildings: Australian regulatory barriers to adaptive reuse. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthuis, K.; Spennemann, D.H.R. The Future of Defunct Religious Buildings: Dutch Approaches to Their Adaptive Re-use. Cult. Trends 2007, 16, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, S.F.; Kealy, L.; Fiorani, D. Conservation Adaptation: Keeping Alive the Spirit of the Place Adaptive Reuse of Heritage with Symbolic Value; EAAE Transactions on Architectural Education no. 65; European Association for Architectural Education: Hasselt, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, S. Guida Alle Chiese “Chiuse” di Venezia; Libria: Melfi, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E. Adaptive Reuse of Religious Buildings in the U.S.: Determinants of Project Outcomes and the Role of Tax Credits. ETD Archive. Available online: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/66 (accessed on 1 January 2010).

- Faro, A.L.; Miceli, A. Sustainable Strategies for the Adaptive Reuse of Religious Heritage: A Social Opportunity. Buildings 2019, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Cesari, C.; Herzfeld, M. Urban Heritage and Social Movements. In Global Heritage: A Reader; Meskell, L., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesari, C.; Dimova, R. Heritage, gentrification, participation: Remaking urban landscapes in the name of culture and historic preservation. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 25, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellamare, C. Città fai-da-te: Tra Antagonismo e Cittadinanza: Storie di Autorganizzazione Urbana; Donzelli: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ostanel, E.; Attili, G. Powers and terrains of ambiguity in the field of urban self-organization today. Tracce Urbane Riv. Ital. Transdiscipl. Studi Urbani 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialardo, A.; Micelli, E. From sources of financial value to commons: Emerging policies for enhancing public real-estate assets in Italy. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2017, 97, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostanel, E. Spazi Fuori dal Comune: Rigenerare, Includere, Innovare; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- L’età Della Condivisione: La Collaborazione Fra Cittadini e Amministrazione Per i Beni Comuni; Arena, G.; Iaione, C. (Eds.) Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OpenHeritage Website. Available online: https://openheritage.eu (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Van Knippenberg, K. Towards an evolutionary heritage approach: Fostering community-heritage engagement. In Proceedings of the 13th AESOP Young Academics Conference 2019, Venice, Italy, 9–13 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C.A. Reflexive Ethnography: A Guide to Researching Selves and Others; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Veldpaus, L.; Fava, F.; Brodowicz, D. Mapping of Current Heritage Re-Use Policies and Regulations in Europe: Complex Policy Overview of Adaptive Heritage Re-Use. 2019. Available online: https://openheritage.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/D1.2_Mapping_current_policies_regulations.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- OpenHeritage Website. Section: Practices. Available online: https://openheritage.eu/practices/ (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Fava, F.; Cannella, F.; Caudo, G. Chapter 2. Scugnizzo Liberato, Naples. OpenHeritage Deliverable 2.2. Observatory Cases Report. Published Online November 2019. Available online: https://openheritage.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/D2.2_Observatory_Cases_Report.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Comune di Napoli—Servizio Statistica. La Struttura Demografica Della Popolazione Residente Nella Città di Napoli al 31 Dicembre 2016. Dati comunali. Published online 2017. Available online: File:///Users/federicafava/Downloads/201610%20 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Cinanni, P. Le Terre Degli Enti, Gli Usi Civici e la Programmazione Economica; Alleanza Nazionale dei Contadini: Rome, Italy, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Masella, N. Politiche urbane e strumenti per la promozione degli usi civici: Il caso studio di Napoli. In La Co-Città: Diritto Urbano e Politiche Pubbliche Per i Beni Comuni e la Rigenerazione Urbana; Chirulli, P., Iaione, C., Eds.; Jovene: Naples, Italy, 2018; pp. 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- Ex-Asilo Filangeri Repository. Available online: http://www.exasilofilangieri.it/approfondimenti-e-reportage/ (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Comune di Napoli. Napoli 2019–2030. Città, Ambiente, Diritti e Beni Comuni: Piano Urbanistico Comunale Documento di Indirizzi. Published online 2019. Available online: https://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/37912 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Renzoni, C.; Savoldi, P. Diritti in Città: Gli Standard Urbanistici in Italia dal 1968 a Oggi; Donzelli: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Co-City Protocol. Available online: http://commoning.city/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2019/02/Protocol-.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Montanari, T. Costituzione Italiana: Articolo 9; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Capriotti, P. Dalle pratiche spontanee alla sistematicità del riuso temporaneo: Un percorso possibile? In Agenda Re-Cycle: Proposte Per Reinventare la Città; Fontanari, E., Piperata, G., Eds.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2017; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Caciagli, C.; Milan, C. Contemporary Urban Commons. Rebuilding the Analytical Framework. Partecip. Confl. 2021, 14, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Translated from an Activist’s Interview, Published in the Scugnizzo Liberato Website. Available online: https://scugnizzoliberato.org/servizi-tv/ (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Sciarelli, R.; D’Alisa, G. La cura del comune. In Trame. Pratiche e Saperi per Un’ecologia Politica Situata; Ecologie Politiche del Presente; Tamu: Naples, Italy, 2021; pp. 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cammelli, M. Re-cycle: Pratiche urbane e innovazione amministrativa per ricomporre le città. In Agenda RE_CYCLE: Proposte per Reinventare La Città; Fontanari, E., Piperata, G., Eds.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2017; pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi, L. Studio per Un Regolamento Delle Pratiche di Autocostruzione e Autorecupero Nei Beni Comuni. 2021. Available online: http://www.tesserae.eu/author/jopixel/ (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Iaione, C. Pooling Urban Commons: The Civic Estate. URBACT. Published 2019. Available online: https://urbact.eu/urban-commons-civic-estate (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Roversi Monaco, M. Tutela e utilità del patrimonio pubblico e del patrimonio culturale: Profili giuridici attuali. In Patrimoni: Il Futuro Della Memoria; Marini, S., Roversi Monaco, M., Eds.; Mimesis: Milan, Italy; Udine, Italy; Venice, Italy, 2016; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Settis, S. Architettura e Democrazia: Paesaggio, Città, Diritti Civili; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wollentz, G.; May, S.; Holtorf, C.; Högberg, A. Toxic heritage: Uncertain and unsafe. In Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices; Rodney, H., De Silvey, C., Holtorf, C., Macdonald, S., Bartolini, N., Breithoff, E., Fredheim, H., Lyons, A., May, S., Eds.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 294–312. Available online: https://www.uclpress.co.uk/products/125036 (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Kølvraa, C.; Knudsen, B.T. Decolonizing European Colonial Heritage in Urban Spaces—An Introduction to the Special Issue. Herit. Soc. 2020, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).